Abstract

Purpose

Patient-reported outcomes including health-related quality of life (HRQoL) are important oncological outcome measures. The validation of HRQoL instruments for patients with hepatocellular and cholangiocellular carcinoma is lacking. Furthermore, studies comparing different treatment options in respect to HRQoL are sparse. The objective of the systematic review and meta-analysis was, therefore, to identify all available HRQoL tools regarding primary liver cancer, to assess the methodological quality of these HRQoL instruments and to compare surgical, interventional and medical treatments with regard to HRQoL.

Methods

A systematic literature search was conducted in MEDLINE, the Cochrane library, PsycINFO, CINAHL and EMBASE. The methodological quality of all identified HRQoL instruments was performed according to the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health status Measurements INstruments (COSMIN) standard. Consequently, the quality of reporting of HRQoL data was assessed. Finally, wherever possible HRQoL data were extracted and quantitative analyses were performed.

Results

A total of 124 studies using 29 different HRQoL instruments were identified. After the methodological assessment, only 10 instruments fulfilled the psychometric criteria and could be included in subsequent analyses. However, quality of reporting of HRQoL data was insufficient, precluding meta-analyses for 9 instruments.

Conclusion

Using a standardized methodological assessment, specific HRQoL instruments are recommended for use in patients with hepatocellular and cholangiocellular carcinoma. HRQoL data of patients undergoing treatment of primary liver cancers are sparse and reporting falls short of published standards. Meaningful comparison of established treatment options with regard to HRQoL was impossible indicating the need for future research.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11136-021-02810-8.

Keywords: Quality of life, Health-related quality of life, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Cholangiocellular carcinoma

Introduction

Besides survival and treatment-associated adverse events, patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are arguably the most relevant outcome parameters in oncology. A PRO is defined as ‘any outcome evaluated directly by the patient himself or herself and is based on patient’s perception of a disease and its treatment(s)’ [1]. PROs have many potential advantages as they may elucidate the relationship between clinical endpoints and the patient´s well-being [1], allowing for a more comprehensive evaluation of patients’ health [2].

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is a multidimensional PRO measure that is of special interest in oncology as it provides a ‘personal assessment of the burden and impact of a malignant disease and its treatment,’ [1] thus, adding valuable information for a true risk–benefit assessment. This is of special interest when prognosis is limited as in primary malignancies of the liver. HRQoL tools can be distinguished into generic, cancer-specific, cancer-type-specific and utility-(preference-)based instruments [3]. While definitions, implementation, evaluation and analyses of survival and toxicity/complication endpoints have been well standardized over the last decades, PROs are still under-evaluated and reported in most clinical settings. Multiple studies have aimed to define suitable HRQoL tools for different clinical settings, e.g. [4, 5], including cancer patients [6–8].

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) account for more than 95% of all primary malignant liver tumours. Hepatitis B and C infections are the most prominent risk factor for HCC [9]. More than 840.000 patients were newly diagnosed with HCC or CCA in 2018, and numbers are estimated to rise > 1.3 million annually until 2040 [10]. Although age-standardized incidence rates are moderate in the Western World, they are high in most parts of Asia and parts of West Africa [10], making HCC one of the most frequent tumours in these parts of the world. Prognosis is dismal with 5-year overall survival being around 15% in the USA and 5% in low-income countries [9]. Besides surgical resection, medical treatment (e.g. chemotherapy, kinase inhibitors) and interventional treatments like radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) constitute the three mainstays of treatment for both HCC and CCA.

Therefore, the objectives of this systematic review and meta-analysis were threefold: (1) to perform a systematic review to identify all published HRQoL tools for primary liver cancer (HCC/CCA); (2) to assess the methodological quality and clinical relevance of these HRQoL measures; and (3) to synthesize quantitative data via means of a meta-analysis to compare surgery vs. interventional treatments vs. systemic therapies with regard to HRQoL.

Material and methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis is reported in line with current PRISMA guidelines [11]. The study was registered in the PROSPERO database on 18th July 2017 (registration number CRD42017068103).

Eligibility criteria

Studies investigating HRQoL in HCC or CCA patients were included independent of language or year of publication. All types of studies were included in our search with the exception of case reports, i.e. randomized controlled trials (RCT), cohort-type studies (CTS), case–control studies (CCS) and cross-sectional studies. Furthermore, studies in animals (non-human studies) were excluded. The patient (P) and outcome (O) terms of the PICOT (patient–intervention–comparison–outcome–time) scheme were used to build a search strategy. The search used the ‘outcome’ term to identify PROMs describing quality of life or HRQoL and the ‘patient’ term to find studies including patients with HCC or CCA. Supplement 1 shows the search strategy for MEDLINE performed via OvidSP. If studies included mixed patient populations (e.g. including HCC patients together with metastatic cancer patients and other tumours), only those trials were included in which HRQoL data could clearly be extracted for HCC and CCA patients.

Information sources

The following databases were searched [12]: (a) MEDLINE via OvidSP last searched on 18th July 2019; (b) Ovid MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations via OvidSP last searched on 18th July 2019; (c) the Cochrane library (including Cochrane reviews, other reviews, trials, technology assessments and economic evaluations) via the Cochrane homepage (Wiley online library) last searched on 18th July 2019; (d) PsycINFO via EBSCO host last searched on 18th July 2019; (e) CINAHL via EBSCO host last searched on 18th July 2019 and (f) Excerpta Medica Database (EMBASE) via EMBASE homepage last searched on 18th July 2019. The references of the included articles were hand searched to identify additional relevant studies. Where necessary, authors were directly contacted to retrieve missing information.

Search

Sensitive search strategies were developed for all databases using wildcards and adjacency terms where appropriate. Supplement 1 shows the search strategy for MEDLINE performed via OvidSP. The search strategies for the other databases were adapted to the specific vocabulary of each database.

Study selection

Search results were imported into EndNote software (EndNote X7.7, Thomson Reuters) [13], and duplicates were removed by using the automated duplicate removal function of EndNote. Consequently, titles and abstracts of studies were screened by two authors (KW, ALM) for fulfilment of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Remaining duplicates were removed manually. For the remaining studies, full text articles were obtained, which were then screened for eligibility by two authors independently (KW, ALM). Reasons for exclusion of full text articles were recorded (Fig. 1). All remaining articles were included in the qualitative syntheses (objectives 1 and 2). For objective 3 (quantitative assessment), all articles using adequate HRQoL measures (i.e. fulfilling objective 2) were included in the assessment of quality of reporting of HRQoL data and risk of bias assessment of individual studies. HRQoL data were extracted wherever possible and grouped according to the three clinical settings: (a) surgery; (b) interventional therapy and (c) medical treatment.

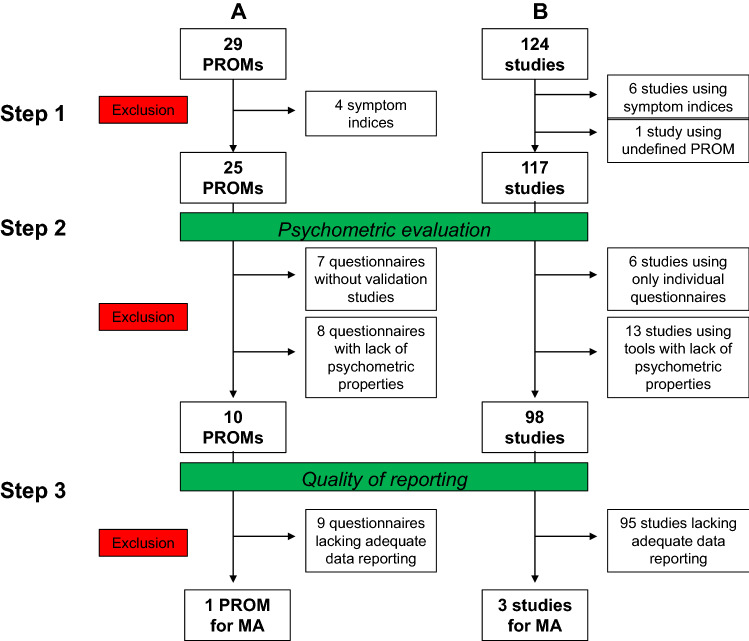

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of included studies

HRQoL assessments were then grouped into 3-month periods. In a next step, quantitative data analysis was performed for those HRQoL measures for which ≥ 2 quantitative data time points were available. For quantitative data analysis, results of individual studies were entered in RevMan 5 software 5.3. (Review Manager, Version 5.3 Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Center, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014).

Data collection process

Data were extracted by two authors independently (KW, ALM) and collected on pre-specified piloted forms. In case, required data were not reported in the study, and authors were contacted to obtain remaining data. Differences in data extraction were resolved by consensus with a third author (MKD).

Data items

The following data items were collected: title, author, year of publication, country where study was performed, journal, language, cancer type, intervention, control, co-interventions, primary endpoint, secondary endpoints, HRQoL tool used, type of study, number of centres, start and end dates of study and intervention, number of patients (total), number of patients allocated to intervention(s), number of patients allocated to control, number of patients evaluated for HRQoL (at each point in time), number of withdrawals, exclusions, conversions, duration of follow-up, HRQoL data at baseline and during follow-up, analysis strategy, subgroups measured and subgroups reported. Furthermore, the following baseline characteristics of patients (for both intervention and control group) were recorded: age, gender, severity of illness, co-morbidities and other relevant baseline characteristics.

Evaluation of methodological quality of the HRQoL measures

The methodological quality of HRQoL measures was assessed based on specific psychometric criteria. Owing to the lack of uniform consensus on how to appraise PRO measures, criteria were applied based on published recommendations [3, 14] in accordance with U.S. Food and Drug Administration guidance [15] and the Oxford University PROMs Group guidelines and the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health status Measurements INstruments (COSMIN) [16]. The criteria and benchmarks laid out in Table 1 were used for evaluation and have been used in previous publications [4, 5]. A rating scale described in previous publications was applied to allocate a mark for each domain [4, 5]: 0 no evidence reported;—evidence not in favour; + evidence in favour; ± conflicting evidence. Lack of basic psychometric evaluation was defined by a priori consensus as evaluation of less than 2 positive ( +) aspects (other than feasibility and interpretability) in HCC/CCA patients. Evaluation was limited to primary hepatic cancers (HCC/CCA), i.e. the psychometric properties of some instruments might have been evaluated in other types of cancer, but not in HCC/CCA patients. In case of lack of psychometric data for a given instrument, searches were conducted in Medline to identify additional studies that have evaluated the psychometric properties of the HRQoL instrument in closely related patient cohorts (e.g. patients with chronic liver disease).

Table 1.

Psychometric criteria used to assess the quality of the patient-reported outcome measures

| Domain | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Test–retest reliability | Test–retest: the intraclass correlation/weighted κ score should be ≥ 0.70 for group comparisons and ≥ 0.90 if scores are going to be used for decisions about an individual based on their score. The mean difference (paired t test or Wilcoxon signed-rank test) between time points 1 and 2, and the 95% CI should also be reported |

| Internal consistency | A Cronbach’s α score of ≥ 0.70 is considered good, and it should not exceed ≥ 0.92 for group comparisons as this is taken to indicate that items in the scale could be redundant. Item correlations should be ≥ 0.20 |

| Content validity | This is assessed qualitatively during the development of an instrument. To achieve good content validity, there must be evidence that the instrument has been developed by consulting patients and experts as well as undertaking a literature review. Patients should be involved in the development stage and item generation. The opinion of patient representatives should be sought on the constructed scale |

| Construct validity | A correlation coefficient of ≥ 0.60 is taken as strong evidence of construct validity. Authors should make specific directional hypotheses and estimate the strength of correlation before testing |

| Criterion validity | A good argument should be made as to why an instrument is standard and correlation with the standard should be ≥ 0.70 |

| Responsiveness | There are a number of methods to measure responsiveness, including t tests, effect size, standardized response means or Guyatt’s responsiveness index. There should be statistically significant changes in score of an expected magnitude |

| Appropriateness | Assessment whether the content of the instrument is appropriate to the questions which the clinical trial is intended to address |

| Interpretability | Subjective assessment whether the scores of the instrument are interpretable for patients or physicians |

| Acceptability | Acceptability is measured by the completeness of the data supplied; ≥ 80% of the data should be complete |

| Feasibility | Qualitative assessment whether the instrument is easy to administer and process |

| Floor-Ceiling effect | A floor or ceiling effect is considered if 15% of respondents are achieving the lowest or the highest score on the Instrument |

Evaluation of the quality of reporting of HRQoL data

For assessment of reporting, the studies were analysed using the following questions: (a) Is HRQoL data analysis described in methods section? (b) Has an a priori statistical analysis plan for HRQoL outcomes been implemented, addressing common problems like missing data, multiple testing? (c) Is HRQoL raw data presented? (d) Is individual patient data reported? (e) Which summary scores are used for HRQoL data? (f) Which time points of HRQoL assessment are described in the methods section? g.) For which time points is HRQoL data reported in the results section?

Assessment of risk of bias in individual studies

For RCTs risk of bias was judged using The Cochrane Collaboration tool of for assessing quality and risk of bias [17]. Risk of bias for non-randomized, interventional trials was assessed with the ROBINS-I tool (Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies—of Interventions, formerly known as ACROBAT-NRSI) as recommended by the Cochrane collaboration [11]. Non-randomized, non-interventional studies were assessed using the Newcastle–Ottawa risk of bias tool [18], and cross-sectional studies were assessed using the AHRQ checklist. RCTs were judged to be at an overall high risk of bias if there was a serious risk of bias in any of the following domains: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, missing data. For non-randomized trials, the following overall risk of bias judgement for individual studies was used in line with Cochrane recommendations [11]: (a) low risk of bias: the study is judged to be at low risk of bias for all domains; (b) moderate risk of bias: the study is judged to be at low or moderate risk of bias for all domains; (c) serious risk of bias: the study is judged to be at serious risk of bias in at least one domain, but not at critical risk of bias in any domain; (d) Critical risk of bias: the study is judged to be at critical risk of bias in at least one domain.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered in RevMan 5 software 5.3. (Review Manager, Version 5.3 Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Center, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014) [19]. As level of significance, an alpha of 0.05 was determined. A random-effect model (inverse variance) was used as there has been clinical heterogeneity between the included trials. Heterogeneity was evaluated using I2 statistic. Results lower than 25% were considered as low, between 25% and 75% as possibly moderate, and results of I2 over 60% were considered as a considerable heterogeneity. HRQoL in HCC/CCA patients was compared by meta-analysis for the following types of interventions: (a) surgery; (b) interventional therapies (e.g. TACE, RFA) and (c) systemic therapies (e.g. chemotherapy). Only studies using the FACT-G/FACT-Hep could be used for meta-analysis (see results section). As these subscores are continuous variables, the mean difference in the FACT-G/FACT-Hep subscores was used as effect measure.

Results

Study selection

We identified 3811 studies by database search and 12 additional studies by hand search resulting in a total of 3823 records. 453 of those studies were duplicates (Fig. 1). After screening titles and abstracts, the other 2888 records were excluded according to inclusion and exclusion criteria. Subsequently, the other 358 articles were excluded after full text analyses for the following reasons: no HRQoL tool (n = 74), other type of cancer (no HCC/CCA) (n = 48), no primary data (n = 198), ongoing study without report (n = 21), double publication (n = 15) and no full text available (n = 2). The remaining 124 studies were included in the final qualitative syntheses (Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the 124 included studies are listed in Table 2 [20–140]. Most studies were cohort-type studies (n = 50; 40.3%), either with (n = 12; 24%) or without control group (n = 38; 76%). The remaining studies were RCTs (n = 41; 33.1%), non-randomized controlled trials (n = 18; 14.5%), cross-sectional studies (n = 7; 5.6%) or case–control studies (n = 8; 6.5%) (Supplement 2). A total of 21,496 patients were included in all studies. Frequently studies investigated HCC patients only (Supplement 2). Most studies were single-centre studies (n = 83; 66.9%; supplement 2). The country of origin is depicted in Supplement 2.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the included studies

| Author | Type of cancer | Study type | Country | Number of centers | Type of intervention | Intervention | Number of patients | Study description | QoL also primary vs. Secondary endpoint | PROM | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Saleh et al. [20] | HCC | RCT | Egypt | 2 | Interventional | RFA | 32 | RFA vs. hepatic resection | Secondary | Questionnaire by Abdelbary | |

| Surgical | Liver resection | 28 | ||||||||||

| 2 | Abou-Alfa et al. [21] | HCC | RCT | 19 countries | 95 | Medical | Cabozantinib | 470 | Cabozantinib vs. placebo in patients with previous sorafenib therapy | Secondary | EQ-5D | |

| Placebo | Placebo | 237 | ||||||||||

| 3 | Aliberti et al. [22] | CCA | CTS | Italy | 1 | Interventional | TACE with Doxorubicin loaded beads | 11 |

TACE with slow-Release Doxorubicin-Eluting Beads vs. palliative chemotherapy |

Unclear | ESAS | |

| Medical | Palliative CTx | 9 | ||||||||||

| 4 | Barbare et al. [23] | HCC | RCT | France | 78 | Medical | Tamoxifen | 210 | Tamoxifen vs. best supportive care | Secondary | Spitzer QoL Index | |

| Placebo | Best supportive care | 210 | ||||||||||

| 5 | Barbare et al. [24] | HCC | RCT | France | 79 | Medical | Octreotide | 135 | Octreotide vs. placebo | Secondary | EORTC QLQ-C30 | |

| Placebo | Placebo | 137 | ||||||||||

| 6 | Becker et al. [25] | HCC | RCT | Germany, Switzerland | 7 | Medical | Octreotide | 61 | Octreotide vs. placebo | Secondary | EORTC QLQ-C30 | |

| Placebo | Placebo | 59 | ||||||||||

| 7 | Berr et al. [26] | CCA | CTS | Germany | 1 | Interventional | 23 | 23 | Photodynamic therapy + biliary stenting | Secondary | Spitzer QoL Index | |

| 8 | Bianchi et al. [27] | HCC | CCS | Italy | 4 | No intervention | None. Patients with HCC | 101 | Comparison of QoL in patients with HCC vs. liver cirrhosis | Primary | SF-36 + Nottingham Health Profile | |

| No intervention | None. Patients with liver cirrhosis | 202 | ||||||||||

| 9 | Blazeby et al. [28] | HCC | CTS | Great Britain, Hong Kong, Taiwan | 6 | Mixed | Mixed treatments | 158 | Development of the HCC18 supplement | Primary | EORTC QLQ-HCC18 | |

| 10 | Boulin et al. [29] | HCC | NRCT | France | 1 | Interventional | 15 mg Idarubicin | 6 | Phase II-Studies of TACE with DC-Beads loaded with idarubicin | Secondary | EORTC QLQ-C30 | QoL data is reported in Anota et al. 2016 |

| Interventional | 10 mg Idarubicin | 6 | ||||||||||

| Interventional | 5 mg Idarubicin | 9 | ||||||||||

| 11 | Brans et al. [30] | HCC | CTS | Belgium | 1 | Interventional | 131I-lipiodol instillation | 26 | Instillation of 131I-Lipiodol in the proper hepatic artery during a hepatic angiography | Primary | EORTC QLQ-C30 | |

| 12 | Bruix et al. [31] | HCC | RCT | 21 countries | 152 | Medical | Regorafenib | 374 | Regorafinib vs. placebo in patients with disease progression under sorafenib | Secondary | FACT-G, FACT-Hep, EQ-5D | |

| Placebo | Placebo | 193 | ||||||||||

| 13 | Brunocilla et al. [32] | HCC | CTS | Italy | 1 | Medical | Sorafenib | 36 | Sorafenib treatment in patients with HCC | Secondary | FACT-Hep | |

| 14 | Cao et al. [33] | HCC | CTS | China | 1 | Interventional | TACE | 155 | TACE in patients with HCC | Primary | MDASI | |

| 15 | Cebon et al. [34] | HCC | CTS | Australia | 13 | Medical | Octreotide | 63 | Octreotide until tumour progression or toxicity | Unclear | FACT-Hep + Pt DATA Form | |

| 16 | Chang-Chien et al. [35] | HCC | CTS | Taiwan | 3 | Surgical | Surgery | 284 | QoL evaluation after surgical treatment for HCC | Primary | FACT-Hep + EORTC QLQ-C30 + SF-36 | |

| 17 | Chay et al. [36] | HCC | RCT | Singapore | 1 | Medical | Coriolus versicolor | 9 | Coriolus versicolor vs. placebo | Secondary | EORTC QLQ-C30 + FACT-Hep | |

| Placebo | Placebo | 6 | ||||||||||

| 18 | Chen et al. [39] | HCC | CTS | China | 1 | Interventional | TACE | 142 | TACE (peripheric embolization) | Secondary | EORTC QLQ-C30 | |

| 19 | Cheng et al. [38] | HCC | RCT | China, South Korea, Taiwan | 23 | Medical | Sorafenib | 150 | Sorafenib vs. placebo | Unclear | FACT-Hep + FHSI-8 | |

| Placebo | Placebo | 76 | ||||||||||

| 20 | Cheng et al. [40] | HCC | RCT | 23 countries | 136 | Medical | Sunitinib | 530 | Sunitinib vs. Sorafenib | Secondary | EQ-5D | |

| Medical | Sorafenib | 544 | ||||||||||

| 21 | Chie et al. [41] | HCC | CTS | Taiwan, UK, China Japan, Italy, France | 6 | Surgical | Surgical treatment | 53 | Cross-cultural validation study for EORTC QLQ-HCC18 | Primary | EORTC QLQ-C30 + EORTC QLQ-HCC18 | Chie et al. 2015 reports on the same data |

| Interventional | Ablation | 53 | ||||||||||

| Interventional | Embolization | 65 | ||||||||||

| Medical | Systemic therapy | 24 | ||||||||||

| No intervention | Off-treatment | 32 | ||||||||||

| 22 | Chie et al. [42] | HCC | CTS | Taiwan, UK, Italy, Japan, France | 7 | Mixed | Asian patients | 181 | Comparison of QoL in Asian vs. European HCC patients undergoing different types of treatments | Primary | EORTC QLQ-C30 + EORTC QLQ-HCC18 | |

| Mixed | European patients | 46 | ||||||||||

| 23 | Chiu et al. [43] | HCC | CTS | Taiwan | 3 | Surgical | Hepatic resection | 332 | HCC patients that underwent hepatic resection | Primary | FACT-Hep + SF-36 | |

| 24 | Chow et al. [44] | HCC | RCT | 9 countries | 10 | Medical | Tamoxifen twice daily | 120 | Tamoxifen vs. tamoxifen + placebo vs. placebo | Secondary | EORTC QLQ-C30 | |

| Medical | Tanoxifen in the morning + placebo at night | 74 | ||||||||||

| Placebo | Placebo | 130 | ||||||||||

| 25 | Chow et al. [45] | HCC | RCT | 6 countries | 7 | Medical | Megestrolacetate | 123 | Megestrolacetate vs. placebo | Secondary | EORTC QLQ-C30 | |

| Placebo | Placebo | 62 | ||||||||||

| 26 | Chow et al. [46] | HCC | CTS | 4 countries | 7 | Medical | Sorafenib | 29 | Sorafenib 14 days post radio embolization | Secondary | EQ-5D | |

| 27 | Chung et al. [47] | HCC | CSS | Taiwan | 3 | Mixed | Mixed treatments | 100 | Symptom evaluation of HCC patients with different types of treatments | Primary | MDASI | |

| 28 | Cowawintaweewat et al. [48] | HCC | CTS | Thailand | 1 | Medical | Active Hexose Correlated Compound Treatment | 34 | AHCC vs. placebo | Primary | Questionnaire by Cowawintaweewat | |

| Placebo | Placebo | 10 | ||||||||||

| 29 | Darwish Murad et al. [49] | CCA | CTS | USA | 1 | Surgical | Neoadjuvant radio-chemotherapy + LT | 79 | Neoadjuvant radio-chemotherapy + LT for CCA vs. LT for other indication than CCA | Primary | EQ-5D + SF-36 + NIDDK-QA | |

| Surgical | LT for other indication than CCA | 110 | ||||||||||

| 30 | Dimitroulopoulos et al. [50] | HCC | NRCT | Greece | 1 | Medical | Positive ocreotide scan: Sandostatin | 15 | Sandostatin vs. no sandostatin | Secondary | EORTC QLQ-C30 | |

| Medical | Negative Octreoscan o refusing octreotide: no sandostatin | 13 | ||||||||||

| 31 | Dimitroulopoulos et al. [51] | HCC | RCT | Greece | 1 | Medical | Octreoscan positive: octreotide s.c. and octreotide long-acting formulation | 30 | Octreotide vs. Placebo with positive Octreoscan compared to patients with negative Octreoscan | Secondary | EORTC QLQ-C30 | |

| Placebo | Octreoscan positive: placebo | 30 | ||||||||||

| Medical | Octreoscan negative: only follow-up | 60 | ||||||||||

| 32 | Doffoël et al. [52] | HCC | RCT | France | 15 | Interventional | Tamoxifen + TACE | 62 | Tamoxifen + TACE vs. Tamoxifen | Secondary | Spitzer QoL Index | |

| Medical | Tamoxifen | 61 | ||||||||||

| 33 | Dollinger et al. [53] | HCC | RCT | Germany | 12 | Medical | Thymostimulin | 67 | Thymostimulin vs. placebo | Secondary | FACT-Hep | |

| Placebo | Placebo | 68 | ||||||||||

| 34 | Dumoulin et al. [54] | CCA | CTS | Germany | 1 | Interventional | Metal stent and photodynamic therapy | 24 | PDT vs. historic control | Unclear | EORTC QLQ-C30 | |

| No intervention | Historic control | 20 | ||||||||||

| 35 | Eltawil et al. [55] | HCC + CCA | CTS | Canada | 1 | Interventional | TACE | 48 | TACE for primary liver cancer | Primary | WHOQoL-BREF | |

| 36 | Fan et al. [56] | HCC | CTS | Taiwan | 2 | Mixed | Surgery, TACE or systemic therapy | 286 | QoL of HCC patients treated with surgery, TACE or systemic therapy was compared to healthy norm values | Primary | EORTC QLQ-C30 + EORTC QLQ-HCC18 | |

| 37 | Gill et al. [57] | HCC | CSS | 13 countries | online- based | Mixed | Different treatments | 256 | All HCC patients were invited to complete the QoL survey | Primary | Questionnaire by Gill | |

| 38 | Gmur et al. [58] | HCC | CTS | Switzerland | 1 | Mixed | Different treatments | 242 | Evaluation of the predictive value of QoL on survival | Primary | FACT-Hep | |

| 39 | Guiu et al. [163] | HCC | NRCT | France | 1 | Interventional | Idarubicin 15 mg | 4 | Phase II study of TACE with DC-Beads with Idarubicin | Secondary | EORTC QLQ-C30 | |

| Interventional | Idarubicin 20 mg | 4 | ||||||||||

| Interventional | Idarubicin 25 mg | 2 | ||||||||||

| 40 | Hakim et al. [59] | HCC | RCT | Zimbabwe | n.a | Medical | Adriamycin 20 mg weekly | 112 | Adriamycin vs. best supportive care | Unclear | FLIC | |

| Medical | Adriamycin 80 mg monthly | |||||||||||

| No intervention | Best supportive care | |||||||||||

| 41 | Hamdy et al. [60] | HCC | CTS | Egypt | 1 | Intervention 1 | RFA | 40 | QoL compared in patients with HCC vs. chronic liver disease | Primary | SF-36 | |

| Intervention 2 | TACE | 40 | ||||||||||

| Control | Patients with HCV but without HCC | 40 | ||||||||||

| 42 | Hartrumpf et al. [61] | HCC | CTS | Germany | 1 | Interventional | TACE | 148 | TACE for patients with HCC | Primary | EORTC QLQ-C30 + EORTC QLQ-HCC18 | |

| 43 | He et al. [62] | HCC | NRCT | China | 1 | Surgical | Liver transplantation | 22 | Liver transplantation vs. hepatic resection vs. RFA | Primary | SF-36 | |

| Surgical | Hepatic resection | 68 | ||||||||||

| Interventional | RFA | 38 | ||||||||||

| 44 | Hebbar et al. [63] | HCC | RCT | France | 17 | Interventional | TACE + sunitinib | 39 | TACE + sunitinib vs. TACE + placebo | Secondary | unclear | |

| Interventional | TACE + placebo | 39 | ||||||||||

| 45 | Heits et al. [64] | HCC | CSS | Germany | 1 | Surgical | Liver transplantation | 173 | QoL in HCC patients after LT was compared to healthy norm values | Primary | EORTC QLQ-C30 | |

| 46 | Hinrichs et al. [65] | HCC | CTS | Germany | 1 | Interventional | TACE | 62 | TACE for patients with HCC | Primary | EORTC QLQ-C30 + EORTC QLQ-HCC18 | |

| 47 | Hoffmann et al. [66] | HCC | RCT | Germany | 4 | Medical | TACE + sorafenib | 24 | TACE + sorafenib vs. TACE + placebo until tumour progression or liver transplantation | Secondary | EORTC QLQ-C30 + EORTC QLQ-HCC18 | QoL data is reported in Hoffmann et al. 2015 |

| Placebo | TACE + placebo | 26 | ||||||||||

| 48 | Hsu et al. [67] | HCC | CTS | Taiwan | 1 | No intervention | No intervention | 300 | Evaluation of the influence of the mini nutritional assessment on functional status and QoL | Unclear | EORTC QLQ-C30 | |

| 49 | Huang et al. [37] | HCC | NRCT | China | 1 | Interventional | RFA | 121 | Patients with a HBV associated solitary HCC with diameter of 3 cm or less underwent RFA vs. hepatic resection | Primary | FACT-Hep | |

| Surgical | Hepatic resection | 225 | ||||||||||

| 50 | Jie et al. [68] | HCC | CTS | China | 1 | No intervention | Informed patients | 126 | QoL in patients informed vs. uninformed of their diagnosis | Primary | EORTC QLQ-C30 | |

| No intervention | Uninformed patients | 92 | ||||||||||

| 51 | Johnson et al. [69] | HCC | RCT | 26 countries | 173 | Medical | Brivanib | 577 | Brivanib vs. placebo as first-line therapy in patients with unresectable, advanced HCC | Secondary | EORTC QLQ-C30 | |

| Placebo | Placebo | 578 | ||||||||||

| 52 | Kensinger et al. [70] | HCC | NRCT | USA | 1 | Surgical | LT for HCC with "MELD exception points" | 106 | Liver transplantation for HCC ± "exception points" vs. liver transplantation without HCC | Primary | SF-36 | |

| Surgical | LT for HCC without "MELD exception points | 33 | ||||||||||

| Surgical | LT without HCC | 363 | ||||||||||

| 53 | Kirchhoff et al. [71] | HCC | RCT | Germany | 5 | Interventional | Transient transarterial chemoocclusion | 35 | Transient transarterial chemoocclusion (TACO) using degradable starch microspheres (DSM) vs. transarterial chemoperfusion without DSM | Secondary | EORTC QLQ-C30 | |

| Interventional | Transarterial chemoperfusion | 35 | ||||||||||

| 54 | Koeberle et al. [72] | HCC | RCT | Switzerland, Austria | 8 | Medical | Sorafenib + Everolimus | 59 | Patients with unresectable or metastatic HCC and Child–Pugh ≤ 7 liver dysfunction | Secondary | EORTC QLQ-C30 + LASA by Bernhard | |

| Medical | Sorafenib | 46 | ||||||||||

| 55 | Kolligs et al. [73] | HCC | RCT | Germany | 2 | Interventional | Selective internal radiation therapy (SIRT) | 13 | SIRT vs. TACE in unresectable HCC | Primary | FACT-Hep | |

| Interventional | Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) | 15 | ||||||||||

| 56 | Kondo et al. [74] | HCC | CCS | Japan | 1 | Interventional | Percutaneous ethanol injection therapy (PEIT) or RFA | 97 | QoL in patients receiving PEIT or RFA vs. QoL in patients with chronic liver disease who had neither current evidence nor history of HCC | Primary | SF-36 | |

| No intervention | Chronic liver disease | 97 | ||||||||||

| 57 | Kudo et al. [75] | HCC | RCT | 20 countries | 154 | Medical | Levatinib | 478 | Levatinib vs. Sorafenib as first-line treatment in patients with unresectable HCC | Secondary | EORTC QLQ-C30 + EORTC QLQ-HCC18 | |

| Medical | Sorafenib | 476 | ||||||||||

| 58 | Kuroda et al. [76] | HCC | NRCT | Japan | 1 | Medical | Branched-chain amino acid—enriched nutrition | 20 | BCAA-enriched nutrition vs standard diet | Secondary | SF-8 | |

| No intervention | Standard diet | 15 | ||||||||||

| 59 | Lee et al. [77] | HCC | NRCT | Taiwan | 1 | Surgical | Hepatic resection | 121 | Hepatic resection vs. TACE vs. PEI vs. best supportive care | Primary | EORTC QLQ-C30 + WHOQoL-BREF | |

| Interventional | TACE | 31 | ||||||||||

| Interventional | Percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI) | 8 | ||||||||||

| No intervention | Best supportive care | 1 | ||||||||||

| 60 | Lee [164] | HCC | CTS | South Korea | 1 | Mixed | Mixed treatments | 40 | QoL in patients receiving different types of treatments | Primary | SF-12 | |

| 61 | Lei et al. [78] | HCC | NRCT | China | 1 | Surgical | Liver transplantation | 95 | LT vs. hepatic resection | Primary | SF-36 | |

| Surgical | Hepatic resection | 110 | ||||||||||

| 62 | Li et al. [79] | HCC | NRCT | China | 1 | Interventional | High intensity focussed ultrasound therapy (HIFU) + best supportive care | 151 | HIFU vs. best supportive care | Unclear | QOL-LC | |

| No intervention | Best supportive care | 30 | ||||||||||

| 63 | Li et al. (2013) | HCC | RCT | China | 1 | Medical | TACE + Celecoxib + Lanreotide | 133 (total) | TACE + Celecoxib + Lanreotide vs. TACE + Celecoxib | Unclear | EORTC QLQ-C30 | |

| Medical | TACE + Celecoxib | |||||||||||

| 64 | Li et al. [80] | HCC | CTS | China | 1 | No intervention | No intervention | 472 | Evaluation of the prognostic value of QoL | Primary | EORTC QLQ-C30 + EORTC QLQ-HCC18 | |

| 65 | Liu et al. [81] | HCC | CTS | China | 2 | Surgical | Hepatic resection + thrombectomy | 65 | Hepatic resection + thrombectomy vs. chemotherapy | Unclear | FACT-Hep | |

| Medical | Systemic therapy | 50 | ||||||||||

| 66 | Llovet et al. [82] | HCC | RCT | 21 countries | 121 | Medical | Sorafenib | 303 | Sorafenib vs. placebo in patients with advanced HCC who had not received previous systemic treatment | Secondary | FHSI-8 | |

| Placebo | Placebo | 299 | ||||||||||

| 67 | Lv et al. [83] | HCC | RCT | China | 1 | Medical | Parecoxib | 60 | Parecoxib vs. placebo in HCC patients receiving TACE | Unclear | Questionnaire by Lv | |

| Placebo | Placebo | 60 | ||||||||||

| 68 | Manesis et al. [84] | HCC | RCT | Greece | 1 | Medical | Triptorelin + Tamoxifen | 33 | Triptorelin + Tamoxifen vs. Triptorelin + Flutamid vs. placebo | Secondary | Spitzer QoL Index | |

| Medical | Triptorelin + Flutamid | 23 | ||||||||||

| Placebo | Placebo | 29 | ||||||||||

| 69 | Meier et al. [85] | HCC | CTS | USA | 1 | No intervention | No intervention | 130 | Qol in patients with therapy naive HCC and liver cirrhosis | Unclear | EORTC QLQ-C30 + EORTC QLQ-HCC18 | |

| 70 | Meyer et al. [86] | HCC | RCT | Great Britain | 1 | Interventional | Transarterial chemoembolization: with cisplatin | 44 | TACE vs. TAE | Secondary | EORTC QLQ-C30 + EORTC QLQ-HCC18 | |

| Interventional | Transarterial embolization | 42 | ||||||||||

| 71 | Mihalache et al. [87] | CCA | CTS | Romania | 1 | Mixed | Curative + palliative treatments: surgery, stenting, chemotherapy, drainage etc | 133 | QoL in patients with curative and palliative treatment for CCA | Unclear | EORTC QLQ-C30 | |

| 72 | Mikoshiba et al. [88] | HCC | CTS | Japan | 1 | Mixed | Different treatments | 192 | Validation of the Japanese version of EORTC QLQ-HCC18 | Primary | EORTC QLQ-C30 + EORTC QLQ-HCC18 + FACT-Hep | |

| 73 | Mikoshiba et al. [89] | HCC | CSS | Japan | 1 | No intervention | Depressive Symptoms | 36 | QoL in HCC patients with or without depressive symptoms | Primary | EORTC QLQ-C30 + EORTC QLQ-HCC18 | |

| No intervention | Without depressive symptoms | 91 | ||||||||||

| 74 | Mise et al. [90] | HCC | CTS | Japan | 1 | Surgical | Hepatic resection | 108 | QoL in patients receiving hepatic resection for HCC | Primary | SF-36 | |

| 75 | Montella et al. [91] | HCC | CTS | Italy | 1 | Medical | Sorafenib | 60 | Sorafenib in patients > 70 years of age with advanced HCC | Unclear | FHSI-8 | |

| 76 | Müller et al. [92] | HCC | RCT | Austria | 1 | Interventional | Octreotide + PEI | 31 | Octreotide + PEI vs. Octreotide | Unclear | VAS by Priestman & Baum | |

| Medical | Octreotide | 30 | ||||||||||

| 77 | Norjiri et al. [93] | HCC | RCT | Japan | 1 | Medical | Branched-chain amino acid (Aminoleban EN) supplementation | 25 | Branched-chain amino acid enriched nutrition vs. standard diet in HCC patients with up to 3 tumour nodules < 3 cm receiving RFA | Secondary | SF-8 | |

| No intervention | Standard diet | 26 | ||||||||||

| 78 | Nowak et al. [94] | HCC | CTS | Australia | 13 | Medical | Octreotide | 46 | Octreotide | Primary | FACT-Hep + Pt DATA Form | Part of a larger Phase II trial (Cebon J, et al. Br J Cancer 2006; 95: 853–61.) |

| 79 | Nugent et al. [95] | HCC | RCT | USA | 1 | Interventional | Stereotactic body radiation therapy | 12 | SBRT vs. TACE as bridging therapy before liver transplantation for HCC | Secondary | SF-36 | |

| Interventional | TACE | 15 | ||||||||||

| 80 | Ortner et al. [96] | CCA | RCT | Germany, Switzerland, Austria | 4 | Interventional | Photodynamic therapy + Stenting | 20 | Photodynamic therapy + Stenting vs. Stenting | Secondary | EORTC QLQ-C30 | |

| Interventional | Stenting | 19 | ||||||||||

| Interventional | Non-randomized PDT + Stenting | 31 | ||||||||||

| 81 | Otegbayo et al. [97] | HCC + CCA | CTS | Nigeria | 1 | No intervention | Unclear | 34 | QoL in patients with HCC | Primary | WHOQoL-BREF | |

| 82 | Palmieri et al. [98] | HCC | CCS | Italy | 1 | No intervention | HCC | 24 | QoL in patients with HCC vs. CLD vs. healthy controls | Primary | SF-36 | |

| No intervention | CLD | 22 | ||||||||||

| No intervention | Healthy controls | 20 | ||||||||||

| 83 | Park et al. [117] | CCA | RCT | South Korea | 1 | Interventional | Photodynamic therapy + S-1 | 21 | Photodynamic therapy ± S-1 for patients with unresectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma | Secondary | DDQ-15 | |

| Interventional | Photodynamic therapy | 22 | ||||||||||

| 84 | Poon et al. [99] | HCC | CTS | China | 1 | Surgical | Hepatic resection | 66 | Hepatic resection vs. TACE | Primary | FACT-G | |

| Interventional | TACE | 10 | ||||||||||

| 85 | Poon et al. [100] | HCC | RCT | China | 1 | Medical | TACE plus branched-chain amino acid as supplement | 41 | Branched-chain amino acid enriched nutrition vs. standard diet in HCC patients with unresectable tumour | Secondary | FACT-G | |

| No intervention | Standard diet | 43 | ||||||||||

| 86 | Qiao et al. [101] | HCC | CSS | China | 1 | No intervention | No intervention | 140 | QoL and TNM stage in patients with HCC | Primary | FACT-Hep | Drop-out 2 patients for disease progression. 3 patients excluded as > 5 items missing |

| 87 | Ryu et al. [102] | HCC | CSS | South Korea | 1 | No intervention | High symptom scores | 53 | Effect of symptoms on QoL in patients with HCC | Primary | FACT-Hep | |

| No intervention | Low symptom scores | 127 | ||||||||||

| 88 | Salem et al. [103] | HCC | NRCT | USA | 1 | Interventional | TACE | 27 | TACE vs. 90Y radioembolization | Primary | FACT-Hep | |

| Interventional | Radioembolization | 29 | ||||||||||

| 89 | Shomura et al. [104] | HCC | CTS | Japan | 1 | Medical | Sorafenib | 54 | QoL during sorafenib treatment | Primary | SF-36 | |

| 90 | Shun et al. [105] | HCC | CTS | Taiwan | 2 | Interventional | Stereotactic radiation therapy | 99 | QoL during SRT treatment for HCC | Primary | FLIC | |

| 91 | Shun et al. [106] | HCC | CTS | Taiwan | 1 | Interventional | TACE | 89 | QoL during TACE for HCC | Primary | SF-12 | |

| 92 | Somjaivong et al. [107] | CCA | CSS | Thailand | 2 | No intervention | No intervention | 260 | Evaluation of the influence of symptoms, social support, uncertainty and coping on QoL | Primary | FACT-Hep | |

| 93 | Steel et al. [108] | HCC | NRCT | USA | 1 | Interventional | Hepatic arterial infusion with 90Y-Micosphere | 14 | 90Y-Microsphere vs. Cisplatin during hepatic arterial infusion for HCC | Primary | FACT-Hep | Butt et al. 2014 and Steel et al. 2006 report on the same data |

| Interventional | Cisplatin infusion of Cisplatin into the hepatic artery | 14 | ||||||||||

| 94 | Steel et al. [109] (1) | HCC | CCS | USA | 1 | No intervention | HCC | 21 | Evaluation of the influence of sexual functioning on QoL | Secondary | FACT-Hep | |

| No intervention | CLD | 23 | ||||||||||

| 95 | Steel et al. [110] (2) | HCC | CCS | USA | 1 | No intervention | HCC | 82 | QoL evaluation by patients themselves vs. caregivers | Primary | FACT-Hep | Steel et al. 2006 reports on the same data |

| No intervention | Caregivers | 82 | ||||||||||

| 96 | Steel et al. [111] | HCC | CCS | USA | 1 | No intervention | HCC | 83 | Comparison of QoL in patients with HCC vs. chronic liver disease vs. healthy controls | Primary | FACT-Hep | Butt et al. 2014 reports on the same data |

| No intervention | Chronic liver disease | 51 | ||||||||||

| No intervention | Healthy controls | 138 | ||||||||||

| 97 | Steel et al. [112] | HCC + CCA | CTS | USA | 1 | No intervention | No intervention | 321 | Evaluation of the prognostic value of QoL | Secondary | FACT-Hep | |

| 98 | Sternby Eilard et al. [113] | HCC | CTS | Sweden, Norway | 4 | No intervention | No intervention | 205 | Evaluation of the prognostic value of QoL | Primary | EORTC QLQ-C30 + EORTC QLQ-HCC18 | |

| 99 | Tanabe et al. B[114] | HCC | CTS | Japan | 1 | Surgical | Hepatic resection | 188 | Hepatic resection for HCC | Unclear | Questionnaire by Tanabe | |

| 100 | Tian et al. [115] | HCC + CCA | RCT | China | 1 | Interventional | TACE with Bruceas- and iodized oil + oral injection of Ganji Decoction | 49 | TACE with Bruceas- and iodized oil + oral injection of Ganji Decoction vs. regular TACE | Unclear | QOL-LC | |

| Interventional | TACE | 48 | ||||||||||

| 101 | Toro et al. [116] | HCC | NRCT | Italy | 1 | Surgical | Hepatic resection | 14 | Hepatic resection vs. TACE vs. RFA vs. no treatment | Primary | FACT-Hep | |

| Interventional | TACE | 15 | ||||||||||

| Interventional | RFA | 9 | ||||||||||

| Control | No treatment | 13 | ||||||||||

| 102 | Treiber et al. [118] | HCC | RCT | Germany | 1 | Medical | Octreotide + Rofecoxib | 32 | Octreotide + Rofecoxib vs. Octreotide in palliative HCC | Primary | SF-36 | |

| Medical | Octreotide | 39 | ||||||||||

| 103 | Ueno et al. [119] | HCC | CTS | Japan | 1 | Surgical | Impaired QoL | 21 | Evaluation of the factors influencing QoL after hepatic resection | Primary | Questionnaire by Ueno | |

| Surgical | Preserved QoL | 75 | ||||||||||

| 104 | Vilgrain et al. [121] | HCC | RCT | France | 25 | Interventional | SIRT | 174 | SIRT vs. Sorafenib in locally advanced and inoperable HCC | Secondary | EORTC QLQ-C30 + EORTC QLQ-HCC18 | |

| Medical | Sorafenib | 206 | ||||||||||

| 105 | Wan et al. [120] | HCC | CTS | China | 1 | Mixed | Different treatments | 105 | Development and validation study of a new QoL tool | Primary | QOL-LC | |

| 106 | Wang et al. [122] | HCC | RCT | China | 1 | Interventional | TACE + RFA | 43 | TACE + RFA vs. TACE | Primary | FACT-G | |

| Interventional | TACE | 40 | ||||||||||

| 107 | Wang et al. [123] | HCC | CSS | China | 1 | No intervention | No intervention | 277 | Evaluation of the influence of symptoms on QoL | Primary | FACT-Hep + MDASI | |

| 108 | Wang et al. [124] | HCC | NRCT | China | 1 | Interventional | Immunotherapy + TACE or radiotherapy | 42 | TACE or radiotherapy with vs. without immunotherapy with DC-CTLs | Primary | EORTC QLQ-C30 | |

| Interventional | TACE or radiotherapy | 26 | ||||||||||

| 109 | Wible et al. [125] | HCC | CTS | USA | 1 | Interventional | TACE | 73 | QoL after TACE for HCC compared with healthy normal values | Primary | SF-36 | |

| 110 | Wiedmann et al. [126] | CCA | CTS | Germany | 1 | Interventional | Photodynamic therapy + biliary stent | 23 | PDT and biliary drainage in patients with hilar CCA | Secondary | Spitzer QoL Index | |

| 111 | Woradet et al. [127] | CCA | CTS | Thailand | 5 | Mixed | Mixed treatments | 99 | QoL in patients receiving standard or palliative therapy for HCC | Primary | FACT-Hep | |

| 112 | Xie et al. [128] | HCC | CTS | China | 1 | Surgical | Hepatic resection | 58 | Hepatic resection vs. TACE | Primary | SF-36 | |

| Interventional | TACE | 44 | ||||||||||

| 113 | Xing et al. [129] | HCC | CTS | USA | 1 | Interventional | TACE with Doxorubicin loaded beads | 118 | QoL in HCC patients receiving TACE with Doxorubicin loaded beads vs. healthy norm values | Primary | SF-36 | |

| 114 | Xing et al. [130] | HCC | CTS | USA | 1 | Interventional | Y90 radioembolization | 30 | QoL in patients with advanced infiltrative HCC and portal vein thrombosis receiving Y90 radioembolization vs. Healthy norm values | Primary | SF-36 | |

| 115 | Xu et al. [131] | HCC | RCT | China | 1 | Interventional | TACE + Jian Pi Li Qi Decoction | 50 | TACE + Jian Pi Li Qi Decoction-Decoction vs. TACE ± placebo | Primary | MDASI-GI | |

| Interventional | TACE + placebo | 40 | ||||||||||

| Interventional | TACE | 50 | ||||||||||

| 116 | Yang et al. [132] | HCC | CTS | China | 1 | Mixed | Different treatments | 114 | Validation of the Chinese version for the EORTC QLQ-HCC18 | Primary | EORTC QLQ-HCC18 | |

| 117 | Yang et al. [133] | HCC | CTS | China | 1 | Interventional | TACE or TEA | 17 | Evaluation of survival and QoL in HCC patients receiving TACE or TEA therapy | Secondary | EORTC QLQ-C30 | |

| 118 | Yau et al. [134] | HCC | CTS | China | 1 | Medical | PEGylated recombinant human arginase 1 | 20 | QoL and survival analysis of HCC patients receiving treatment with PEGylated recombinant human arginase 1 | Secondary | EORTC QLQ-C30 + EORTC QLQ-HCC18 | |

| 119 | Ye et al. [135] | HCC + CCA | RCT | China | 4 | Medical | Shungbai San | 67 | Shunbai San dermal application vs. Placebo dermal application | Primary | EORTC QLQ-C30 + QOL-LC | |

| Placebo | Placebo | 66 | ||||||||||

| 120 | Yen et al. [136] | HCC | NRCT | USA | 4 | Medical | Capecitabine 1000 mg/m2 + PHY906 1000 mg | 3 | Phase I/II study of Capecitabine/PHY906 in HCC patients | Secondary | FACT-Hep | |

| Medical | Capecitabine 750 mg/m2 + PHY906 600 mg | 8 | ||||||||||

| Medical | Capecitabine 750 mg/m2 + PHY906 800 mg | 31 | ||||||||||

| 121 | Zhang et al. [137] | HCC | NRCT | China | 1 | Medical | Sorafenib | 102 | HCC patients with complete response after TACE or RFA who received sorafenib or not | Unclear | FACT-Hep | |

| No intervention | No sorafenib | 55 | ||||||||||

| 122 | Zheng et al. [138] | HCC | NRCT | China | 1 | Surgical | Surgical treatment | 29 | Surgical vs. conservative treatment of spinal metastasis in HCC patients | Primary | FACT-Hep | |

| No intervention | Conservative treatment | 33 | ||||||||||

| 123 | Zhu et al. [139] | HCC | RCT | 17 countries | 111 | Medical | Everolimus | 362 | Everolimus vs. placebo | Secondary | EORTC QLQ-C30 | |

| Placebo | Placebo | 184 | ||||||||||

| 124 | Zhu et al. [140] | HCC | RCT | 27 countries | 154 | Medical | Ramucirumab | 283 | Ramucirumab vs. placebo | Secondary | FHSI-8 + EQ-5D | QoL data is reported in Chau et al. 2017 |

| Placebo | Placebo | 282 |

Abbreviations: JPLQ-Decoction Jian Pi Li Qi Decoction (mixture of Chinese medical herbs), Shungbai San traditional mixture of Chinese medicine containing 5 main plant-based ingredients, Coriolus versicolor mushroom of the family of Basidiomycota used in the traditional Asian medicine, Aminoleban EN mixture of amino acids, hydolysed collagen, dextran, rice oil, minerals and vitamins, BCAA branched-chain amino acids, DC-CTLs dendritic cell-cytotoxic T lymphocytes, Ganji Decoction mixture of Chinese medical herbs

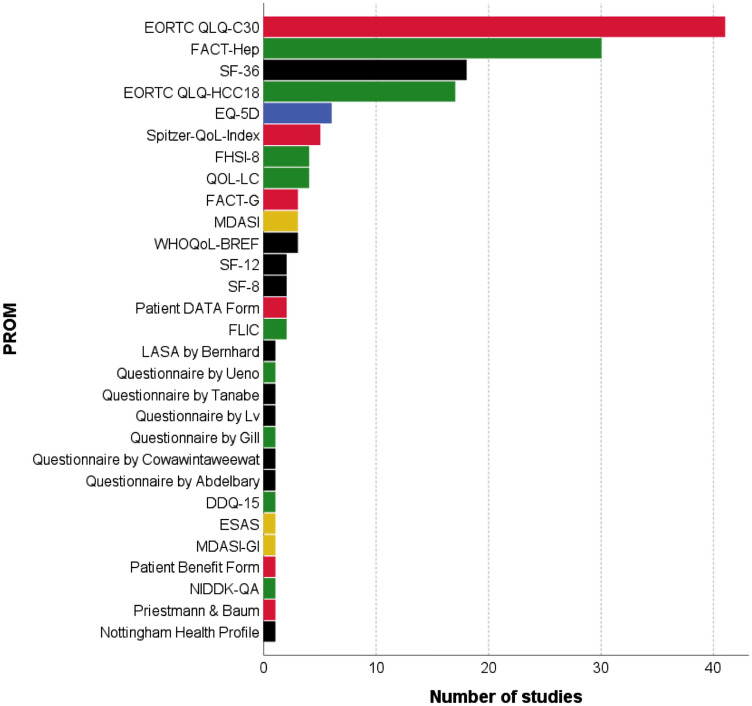

Health-related quality of life instruments

In total, 29 different HRQoLs in 124 studies instruments were identified by our search (Figs. 2 and 3). Of those, 26 different HRQoL PROMs were identified in HCC patients, 8 in CCA patients and 4 different tools in mixed patient cohorts. Multiple studies used more than one HRQoL tool (Table 1). The identified instruments covered all types of HRQoL (generic, cancer-specific, cancer-type-specific and utility-based HRQoL instruments) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Health-related quality of life instruments used in the included studies. Generic (black), cancer-specific (red), cancer-type-specific (green), utility-based (blue) and symptom index (yellow). EORTC European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, EQ EuroQol, ESAS Edmonton symptom assessment scale, FACT Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy, FLIC The Functional Living Index-Cancer, Pt DATA Form Patient Disease and Treatment Assessment Form, QoL quality of life, NIDDK-QA National Institutes of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases QoL Assessment, SF Short Form Health Survey, VAS visual analogue scale, WHO World Health Organization, WHO-BREF abbreviated version of the WHOQOL-100, WHOQOL-100 WHO quality of life 100 tool

Fig. 3.

Flow chart of a included HRQoL measures and b number of studies from qualitative data analyses to quantitative data analyses. PROM patient-reported outcome measure, MA meta-analyses

Despite being labelled as HRQoL instruments in the studies, a number of the identified instruments solely address cancer symptoms and, thus, lack the multidimensionality that is requested for HRQoL and were, thus, excluded from further analyses (Fig. 3 step 1). These were (a) MD Anderson symptom inventory; (b) ESAS: Edmonton symptom assessment scale; (c) MD Anderson symptom inventory – gastrointestinal and (d) FHSI-8 FACT hepatobiliary symptom index. The remaining 25 instruments (117 studies) were included in the further analyses (Fig. 3). These 25 instruments use two to eight domains covering various aspects of quality of life (e.g. physical and mental health, role functioning and symptom burden). The EORTC QLQ-C30 and the FACT-G have cancer-type-specific supplements (EORTC QLQ-HCC18 and FACT-Hep) which can only be used in combination with the more general questionnaire. The questionnaires comprise 5 (EQ-5D) to 47 questions (NIDDK-QA) and have a recall period from the 24 h (EQ-5D) to 4 weeks (SF-8/12/36, Patient Benefit Form). Most of them can be completed within 10 min.

Methodological assessment of HRQoL instruments

The methodological quality of the remaining 25 HRQoL instruments was assessed as outlined in the methods section. Results are shown in Table 3. If no data for a given HRQoL instruments were available for HCC/CCA patients, additional Medline searches were performed to identify methodology studies that evaluated the PROM in closely related patient populations like chronic liver disease. These studies are indicated in Table 3.

Table 3.

Overview of the methodological quality of HRQoL tools in primary liver cancer

| Psychometric properties | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| References | Test–retest reliability | Internal consistency | Content validity | Criterion validity | Construct validity | Responsiveness | Acceptability | Feasibility | Floor/ceiling effects | Interpretability |

| Generic PROMs | ||||||||||

| LASA** by Bernhard (Koeberle et al.) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + |

| NHP | 0 | + (Bianchi 2003) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + (Bianchi 2003) | + (Bianchi 2003) | 0 | + |

| SF-8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + |

| SF-12 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + |

| SF-36 | + (Ünal 2001*) | + (Bayliss 1998*, Ünal 2001*, Zhou 2013*, Casanovas Taltavull 2015*) | 0 | 0 | + (Bayliss 1998*, Ünal 2001*, Zhou 2013*) | 0 | + (Bayliss 1998*, Ünal 2001*, Zhou 2013*) | + (Ünal 2001*) | − (Bayliss 1998*, Zhou 2013*); ± (Ünal 2001*) | + |

| Questionnaire by Abdelbary | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + |

| Questionnaire by Cowawintaweewat | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + |

| Questionnaire by Lv | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + |

| Questionnaire by Tanabe | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + |

| WHOQoL-BREF | 0 | + (Lin 2018*, Lee 2007) | 0 | 0 | ± (Lin 2018*) | 0 | + | + | 0 | + |

| Cancer specific PROMs | ||||||||||

| EORTC QLQ-C30 | 0 | + (Lee 2007) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + | + | 0 | + |

| FACT-G | + (Yount 2002*, Zhu 2008*) | + (Yount 2002*, Zhu 2008*) | + (Cella 1993*) | + (Zhu 2008*) | 0 | 0 | + | + | 0 | + |

| FLIC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + |

| Patient Benefit Form | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + |

| Patient DATA Form | 0 | 0 | 0 | ± (Nowak 2008, Cebon 2006) | + (Nowak 2008) | − (Nowak 2008) | ± (Nowak 2008, Cebon 2006) | + | − (Nowak 2008) | + |

| Priestman & Baum | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ± |

| Spitzer QoL Index | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + (Barbare 2005, Wiedmann 2004) | + (Berr 2000, Doffoël 2008, Barbare 2005) | 0 | + |

| Cancer–type-specific PROMs | ||||||||||

| DDQ-15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + |

| EORTC QLQ-HCC18 | + (Chie 2012, Chie 2015, Mikoshiba 2012) | ± (Mikoshiba 2012, Chie 2012) | + (Blazeby 2004*) | 0 | ± (Mikoshiba 2012; Chie 2012, Chie 2015) | ± (Chie 2012, Chie 2015) | + (Meier 2015, Mikoshiba 2012, Fan 2013) | + (Chie 2012, Chie 2015, Fan 2013, Meier 2015) | ± (Meier 2015, Chien 2015) | + |

| FACT-Hep | + (Heffernan 2002, Yount 2002*, Zhu 2008) | + (Heffernan 2002, Steel 2006, Mikoshiba 2012) | + (Heffernan 2002) | + (Heffernan 2002; Zhu 2008) | + (Heffernan 2002, Zhu 2008, Mikoshiba 2012) | + (Steel 2006, Zhang 2015) ± (Nowak 2008) | ± (Nowak 2008); + (Zhang 2015; Steel 2007; Huang 2014) | + | 0 | + |

| NIDDK-QA | + (Kim 2000*) | + (Kim 2000*) | ± (Gross 1999*) | + (Kim 2000*) | + (Kim 2000*) | + (Kim 2000*) | 0 | 0 | 0 | + |

| QOL-LC | + (Wan 2010*) | + (Wan 2010*) | ± (Wan 2010*) | - (Wan 2010*) | + (Wan 2010*) | + (Wan 2010*) | + (Wan 2010*) | + | + (Ye 2016) | + |

| Questionnaire by Gill | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + |

| Questionnaire by Ueno | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | + |

| Utility based PROMs | ||||||||||

| EQ-5D | ± (Ünal 2001*) | 0 | 0 | + (Krabbe 2003*) | 0 | + (Unal 2001*, Chau 2017) | + (Ünal 2001*, Chow 2014, Chau 2017) | + | ± (Ünal 2001*) | + |

*Publications were identified via additional search in Pubmed. These studies were not solely conducted HCC/CCA patient populations but contain closely related patient populations like patients with chronic liver disease or extrahepatic bile duct tumours

0 = not reported (no evaluation completed),—= evidence not in favour, ± = weak evidence, + = evidence in favour

Gross 1999 + Kim 2000: development of questionnaire and validation of psychometric properties in patients with cholestatic liver disease/liver transplantation

**linear analogue-self assessment

Marked with * are studies that investigate psychometric properties in closely related patient cohorts (not only containing HCC/CCA patients). Rating: 0 no data reported;—evidence not in favour; + evidence in favour; ± conflicting evidence (rating scale adapted from [4, 5])

The most frequently evaluated dimension in all HRQoL tools was reliability (test–retest reliability and internal consistency). With a test–retest correlation of more than 0.70, adequate performance for 6 out of 12 PROMs (SF-36, FACT-G, EORTC QLQ-HCC18, FACT-Hep, NIDDK-QA and QOL-LC) was confirmed [41, 88, 120, 141–146]. For the EQ-5D, correlation coefficients ranging from 0.58 to 0.98 were observed showing that not all scales in this PROM are reliable enough [141]. Internal consistency was evaluated with the calculation of Cronbach’s α. A value greater 0.70 was considered sufficient according to COSMIN guidelines [16]. This could be observed in 8 out of 12 HRQoL tools (NHP, SF-36, WHO-BREF, EORTC QLQ-C30, FACT-G, FACT-Hep, NIDDK-QA and QOL-LC) [27, 77, 88, 120, 141, 142, 144–151]. Concerning validity, rarely all three pre-defined categories (content, criterion and construct validity) were evaluated. More frequently only one or two aspects of validity were examined. Content validity was evaluated investigating the process of questionnaire creation. In case of the FACT-G, FACT-Hep and EORTC QLQ-HCC18, the process described included qualitative studies with inclusion of expert opinions, patient reports and current literature [28, 144, 152]. Merely three PROMs (FACT-Hep, FACT-Hep and NIDDK-QA) were compared to the gold standard (i.e. an already established questionnaire), thus, testing criterion validity [144–146]. In order to evaluate construct validity, group comparisons using performance status (such as the Karnofsky Performance Status) were used for the EORTC QLQ-HCC18 and FACT-Hep questionnaires as it is known that a higher performance status correlates with better HRQoL [41, 88]. Construct validity within the SF-36 was evaluated using the correlation with hypothesized scores (conceptually related and unrelated scores) [141, 148, 149]. Kim et al. compared item scores between ambulatory patients and liver transplant recipients as well as examined correlations between the domain scores of NIDDK-QA vs. SF-36 and Mayo risk score, respectively [146]. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used by Chie et al. to evaluate if the changes in score were significant before and after treatment. For example, patients undergoing surgical treatment suffered significantly more pain compared to before which reflects an adequate responsiveness of the EORTC QLQ-HCC18 [41]. Steel et al. evaluated the clinically meaningful changes of the FACT-Hep over time and found significant decrements in all subscales from baseline to 3-month follow-up [147]. The SF-36 performed poorly during the evaluation of floor and ceiling effects with patients scoring the highest or lowest possible score in distinctly more than 15% which was the set cut-off [148, 149]. Valid acceptability and feasibility were assumed when the response rate was > 80%, or the time to complete the questionnaire was 10 or less minutes [24, 27, 46, 56, 85, 88, 120, 126, 141, 148, 149, 153]. The interpretability of all PROMs was considered acceptable as higher scores in QoL scales represent higher HRQoL, and higher scores within the symptom scales represent lower HRQoL.

Due to a lack of data concerning the basic psychometric evaluation or negative results, only the following 10 HRQoL instruments were considered methodologically adequate according to the pre-specified criteria (see methods section) and were subsequently included in further analyses (Table 3): (a) Generic HRQoL: NHP, SF-36, WHO-BREF; (b) Cancer (Condition)-specific HRQoL: EORTC QLQ-C30 and FACT-G; (c) Cancer type-specific HRQoL: EORTC QLQ-HCC18, FACT-Hep, NIDDK-QA and QOL-LC; (d) Utility (preference)-based HRQoL: EQ-5D. Only publications using one of the above-mentioned 10 HRQoL measures were included in further analyses (n = 98 studies) (Fig. 3 step 2).

Quality of reporting of HRQoL data

The remaining studies were evaluated for the quality of reporting of HRQoL data. Results are summarized in Supplement 3. Of the 98 included studies, 4 (4,1%) did not specify in their methods section at what exact time points HRQoL data were measured [28, 31, 74, 79]. Many studies showed a marked discrepancy between reported HRQoL data in the results section and the frequency of HRQoL data assessment specified in the methods section. Eight studies reported only baseline HRQoL data although these trials specified in their methods section to have assessed HRQoL also during follow-up [38, 41, 42, 58, 80, 94, 98, 139]. The other 18 studies lacked reporting of HRQoL data altogether in their results section, although assessment had been announced in the methods section (supplement 3) [25, 28, 31, 44, 50, 53, 56, 66, 71, 74, 75, 80, 95, 97, 112, 134, 136, 139]. A total of 32 studies did not report raw HRQoL data and consequently could not be used for meta-analysis [21, 25, 27, 29, 32, 34, 35, 38, 40, 44–46, 49–51, 53, 56, 58, 66, 71, 75, 86, 95, 97, 112, 118, 128–130, 134, 136, 139]. The other 17 papers reported HRQoL data only in graphical form, which impedes meta-analysis [61, 64, 70, 72–74, 87, 90, 110, 113, 118, 121, 124, 128–130, 137]. Furthermore, although most studies reported the statistical methods, they used to analyse HRQoL, only 6 publications used a pre-specified statistical analysis plan addressing common methodological problems in HRQoL analysis [41, 43, 103, 104, 108, 125]. Finally, nine publications combined patient groups undergoing different treatment options (surgery/medical therapy/interventional treatment) for the reporting of HRQoL outcomes. In these cases, assignment of HRQoL outcomes to a specific treatment (surgery vs. medical therapy vs interventional treatment) was impossible [28, 42, 56, 58, 87, 88, 120, 127, 132]. In summary, only three studies remained for quantitative analyses (Fig. 3 step 3).

Supplement 4 illustrates the discrepancy between supposedly available and reported data for the FACT-Hep (A/B) and EORTC QLQ-C30 (C/D) HRQoL instruments.

Data synthesis for HRQoL tools

For generic HRQoL instruments like the SF-36, EQ-5D or WHO-BREF, no meta-analysis following treatment was possible, either because primary data were insufficiently reported (supplement 4) or only single articles reporting raw data were identified. Similarly, for cancer (type)-specific HRQoL tools like EORTC QLQ-C30, EORTC QLQ-HCC18 and QLQ-LC meta-analysis of HRQoL data, the following treatment was impeded by either insufficient reporting during follow-up (supplement 3), or studies compared interventions that were too heterogeneous for meta-analysis. Only for the FACT-G and FACT-Hep questionnaires, clinically comparable interventions were analysed in several studies: Six studies contained surgical study groups [35, 37, 43, 81, 99, 116], two studies contained data on RFA [37, 116], and 5 studies reported extractable data in TACE patients [73, 99, 103, 116, 123]. Although FACT-G or FACT-Hep was used in several studies investigating medical treatment options for HCC, these were either single-arm studies [32, 34, 94], contained placebo control groups [31, 36, 38, 53, 137] or compared two medical treatment options [72, 136], thus, precluding a comparison to interventional/surgical treatments. Similarly, some studies used the FACT-G or FACT-Hep questionnaire to compare different interventional treatments [73, 103, 116, 122], again impeding meta-analysis. Consequently, only 3 studies using the FACT-G/FACT-Hep remained for meta-analysis (Fig. 3 step 3).

Meta-analyses

For the comparison of surgical resection vs. TACE, only two studies reported raw data at baseline and during follow-up [99, 116] (supplement 5A). Poon et al. split the surgical cohort into two distinct subgroups: those with a complete follow-up of two years and those with a shorter follow-up. This is likely to introduce major bias as patients completing 2-year follow-up are likely to be healthier and have less aggressive tumour diseases. We, therefore, pooled the data for the two surgical groups. Supplement 5A shows the results of this exploratory meta-analysis of the mean difference in FACT-subscores (functional, physical, social and emotional well-being) at 12-month post-intervention/surgery. One additional analysis was possible: the comparison of surgery vs. RFA as data are reported in the two studies by Huang et al. and Toro et al. [37, 116]. Supplement 5B shows the results of the exploratory meta-analysis for the 12-month post-interventional/postoperative follow-up, again comparing mean differences in FACT-subscores.

Discussion

HRQoLs represent an important domain of clinical outcomes in oncology. While definitions, implementation, evaluation and analyses of survival and toxicity/complication endpoints have been well standardized over the last decades, PROs are still under-evaluated and reported in most clinical settings. Multiple studies have aimed to define suitable HRQoL tools for different clinical settings, e.g. [4, 5], including cancer patients [6–8]. However, no concise evaluation has been performed for patients with primary liver cancers (HCC or CCA).

Although 124 studies were included in this systematic review, we were able to complete only the first two objectives of our study, namely to identify and evaluated HRQoL measures in HCC/CCA patients. However, meta-analysis of study results comparing the outcome of surgical, interventional or medical treatments for HCC/CCA patients in regard to HRQoL was barely possible due to the use of different HRQoL instruments, lack of data or insufficient reporting.

We identified 29 different HRQoL instruments, which indicate vast heterogeneity and lack of consensus in this field. Similar results have been reported before in other diseases [6–8]. Furthermore, many of the identified tools lacked basic HRQoL characteristics like multidimensionality [154, 155]. Hence many authors seemed to be unaware of the difference between mere symptom measures and HRQoL instruments. In addition, validation of HRQoL is poor for most instruments in HCC/CCA patients (Table 2). As expected, the best psychometric data were available for cancer-type-specific HRQoL instruments, like EORTC QLQ-HCC18 or the FACT-Hep. Interestingly, even for common generic and disease-specific HRQoL tools, like the Spitzer quality of life index and the EORTC QLQ-C30, data in HCC/CCA patients are sparse. Hence, evaluation of these common tools in this patient cohort seems necessary in future studies. In addition, even for HRQoL measures developed especially for liver cancer patients, psychometric properties were less stringent as might have been thought. The EORTC QLQ-HCC18 shows mixed psychometric results [41, 88]. FACT-Hep, on the other hand, although showing good psychometric properties, has been validated only in mixed patient populations including patients with liver metastases and pancreatic cancer in addition to HCC/CCA patients [144, 147]. Similarly, the preference-based HRQoL EQ-5D has been extensively evaluated in chronic liver disease, but little psychometric data are available in HCC/CCA patients. Future studies should address these shortcomings.

Nevertheless, our analysis revealed suitable HRQoL instruments with sound psychometric properties that should be used in all future HRQoL studies. These are SF-36 [156] for generic HRQoL measurement. The SF-36 is a generic HRQoL instrument consisting of 36 items divided into eight scales (Physical Functioning, Emotional Role Functioning, Physical Role Functioning Bodily Pain, General Health, Vitality, Social Functioning, Mental Health, Health Transition) [156]. The number of response choices per item ranges from two to six. The scores for each scale range from 0 to 100. A higher score indicates a better QOL. The time frame of the SF-36 is ‘last week’ [141].

For cancer-specific HRQoL measurement in HCC/CCA patients, the EORTC QLQ-C30 [157] and the FACT-G can be recommended. Both have limited, but acceptable psychometric properties in HCC/CCA patients and have been used extensively in this patient cohort. The 30-item QLQ-C30 measures five functional scales (physical, role, emotional, cognitive and social functioning), global health status, financial difficulties and eight symptom scales (fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnoea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation and diarrhoea). The scores vary from 0 (worst) to 100 (best) for the global health status and functional scales, and from 0 (best) to 100 (worst) for symptomatic scales [157]. The FACT-G consists of 27 items for the assessment of four domains of QOL: (1) Physical Well-Being and (2) Socio-Family Well-Being contain seven items each; (3) Emotional Well-Being contains six items and (4) Functional Well-Being contains seven items. The time frame of the FACT-G is ‘last week’. Each item is scored on a 5-point ordinal scale, where 0 indicates not at all and 4, very much [152].

Cancer-type-specific HRQoL should be measured via the EORTC QLQ-HCC18 or FACT-Hep. The EORTC QLQ-HCC18 is an 18-item HCC-specific supplemental module developed to augment QLQ-C30 and to enhance the sensitivity and specificity of HCC-related QOL issues. It contains six multi-item scales addressing fatigue, body image, jaundice, nutrition, pain and fever, as well as two single items addressing sexual life and abdominal swelling. The scales and items are linearly transformed to a 0 to 100 score, where 100 represents the worst status [28, 88]. The FACT-Hep is a 45-item self-reported instrument that consists of the 27-item FACT-G (see above), and the 18-item hepatobiliary cancer subscale, which assesses specific symptoms of hepatobiliary cancer and side effects of treatment. The FACT-G and hepatobiliary cancer subscale scores are summed to obtain the FACT-Hep total score [37, 144]. The QoL-LC questionnaire shows good psychometric properties but has been developed and tested exclusively in Chinese patients, thus, limiting its generalizability. Similarly, NIDDK-QA as a cancer-type–specific HRQoL tool has been used in only one study and, thus, cannot be recommended currently.

For utility-based HRQoL measurement, the EQ-5D [158] has been identified as the instrument of choice. It fulfils basic psychometric requirements, and a sound database is available in HCC/CCA patients. The EQ-5D consists of five items (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression). Each item has three response categories: no problems, some problems and extreme problems. The sixth item is a global health evaluation scale, ranging from 0 (the worst imaginable health state) to 100 (the best imaginable health state). The time frame of the EQ-5D instrument is the present moment.

The quality reporting of the HRQoL results was insufficient overall. Few trials reported common methodological problems of HRQoL data like multiple testing, missing data or a priori hypothesis. Raw data were rarely reported and summarize measures (mean, median etc.) as well as follow-up regimes varied widely between studies. In addition, the methodological quality of the studies was generally poor. Thus, despite a total of 124 studies available, evidence regarding HRQoL in HCC/CCA patients is limited.

It is astonishing that reporting of HRQoL data does not seem to have improved over the last decades despite the publication of multiple guidelines and recommendations concerning HRQoL reporting. Few of the included studies fulfiled basic reporting standards for HRQoL like the ones proposed by Basch et al. [159], Staquet et al. [160], the International Society for QoL research (ISOQOL) [161] or the CONSORT—Patient-reported outcome extension [162].

These shortcomings in the methodological quality and reporting were the main reasons for the insufficient meta-analyses in our study. Studies had to be excluded at various points along the way (Fig. 3). The planned comparison of treatment options (surgery vs. medical treatment vs. interventional treatment) with regard to HRQoL can, therefore, be regarded exploratory at best. Future, high-quality HRQoL trials, adhering to basic reporting standards, are urgently needed to address these shortcomings.

One of the main strengths of the current study is the use of a comprehensive search strategy to identify all relevant publications. Furthermore, to our knowledge, this is the first study that assesses the methodological quality of HRQoL tools in HCC/CCA patients according to internationally accepted standards time [3, 15, 16] thereby identifying suitable HRQoL instruments for the use in future studies. In addition, this study can be used as an easy reference standard to identify available studies and raw data for the design and sample size calculation in future HCC/CCA trials. The transparent analysis process in this study can be regarded as a further strength.

The main limitation of our analysis is the heterogeneity of included studies, patients and trial designs. The variations in the application, analyses and reporting of HRQoL between studies made data synthesis difficult. The meta-analyses should regarded exploratory at best.

In summary, clear recommendations for generic, cancer-specific, cancer-type-specific and preference-based HRQoL instruments in HCC/CCA patients can be given. Meta-analysis of data comparing different treatment options in HCC/CC patients was severely limited due to methodological weaknesses of the included studies and shortcomings in reporting. Future trials should address these aspects and adhere to HRQoL reporting standards.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

KW, ALM, MKD and CE are responsible for conception and design of the study. KW, PH and ALM performed the acquisition and analysis of the data, and drafted the manuscript. KW, PH, PP, CE, MKD and ALM offered substantial contributions to interpretation of the data and critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave their final approval of this version of the manuscript and are accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. No funding was used to create this review.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.European Medicines Agency. (2016, April 1). The use of patient-reported outcome (PRO) measures in oncology studies. Appendix 2 to the guideline on the evaluation of anticancer medicinal products in man. EMA/CHMP/292464/2014.

- 2.McGrail K, Bryan S, Davis J. Let’s all go to the PROM: The case for routine patient-reported outcome measurement in Canadian healthcare. HealthcarePapers. 2011;11(4):8–18. doi: 10.12927/hcpap.2012.22697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fitzpatrick R, Davey C, Buxton MJ, Jones DR. Evaluating patient-based outcome measures for use in clinical trials. Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England) 1998;2(14):1–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aber A, Poku E, Phillips P, Essat M, Buckley Woods H, Palfreyman S, Kaltenthaler E, Jones G, Michaels J. Systematic review of patient-reported outcome measures in patients with varicose veins. The British Journal of Surgery. 2017;104(11):1424–1432. doi: 10.1002/bjs.10639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poku E, Aber A, Phillips P, Essat M, Buckley Woods H, Palfreyman S, Kaltenthaler E, Jones G, Michaels J. Systematic review assessing the measurement properties of patient-reported outcomes for venous leg ulcers. BJS open. 2017;1(5):138–147. doi: 10.1002/bjs5.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hadi M, Gibbons E, Fitzpatrick R. Structured Review of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMS) for colorectal cancer. Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gazala S, Pelletier J-S, Storie D, Johnson JA, Kutsogiannis DJ, Bédard ELR. A systematic review and meta-analysis to assess patient-reported outcomes after lung cancer surgery. The Scientific World Journal. 2013;2013:789625. doi: 10.1155/2013/789625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Straatman J, van der Wielen N, Joosten PJ, Terwee CB, Cuesta MA, Jansma EP, van der Peet DL. Assessment of patient-reported outcome measures in the surgical treatment of patients with gastric cancer. Surgical Endoscopy. 2016;30(5):1920–1929. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4415-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bosetti C, Turati F, La Vecchia C. Hepatocellular carcinoma epidemiology. Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology. 2014;28(5):753–770. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.GLOBOCAN, WHO International Agency for Research in CAncer. (2019, 21 March). Global Cancer Observatory. Retrieved from http://gco.iarc.fr/

- 11.Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, Henry D, Altman DG, Ansari MT, Boutron I, Carpenter JR, Higgins JP. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goossen K, Tenckhoff S, Probst P, Grummich K, Mihaljevic AL, Büchler MW, Diener MK. Optimal literature search for systematic reviews in surgery. Langenbeck’s Archives of Surgery. 2018;403(1):119–129. doi: 10.1007/s00423-017-1646-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomson Reuters. (2013). EndNote X7.7.

- 14.Terwee CB, Bot SDM, de Boer MR, van der Windt DAWM, Knol DL, Dekker J, Lex M, de Vet HCW. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2007;60(1):34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.FDA. (2009, December). Guidance for Industry: Patient-Reported Outcome Measures: Use in Medical Product Development to Support Labeling Claims. Retrieved from https://www.fda.gov/media/77832/download [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Mokkink LB, Terwee CB, Patrick DL, Alonso J, Stratford PW, Knol DL, Lex M, de Vet HCW. The COSMIN checklist for assessing the methodological quality of studies on measurement properties of health status measurement instruments: An international Delphi study. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation. 2010;19(4):539–549. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9606-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins, J. P. T., & Green, S. (2011). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (5.1.0.). The Cochrane Collaboration. Retrieved from https://training.cochrane.org/cochrane-handbook-systematic-reviews-interventions