Abstract

Introduction:

Chronic villitis is an inflammatory lesion that affects 5–15% of placentas and is associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Chronic villitis may also recur; however, studies estimating recurrence are based on small samples and estimates of recurrence range from 10–56%.

Methods:

We utilized data from placentas submitted to pathology at a Chicago hospital between January 2009 and March 2018. During the study period, 883 patients had two placentas submitted to pathology. We estimated the risk of recurrent chronic villitis, adjusted for maternal and pregnancy characteristics. We also evaluated whether prevalence of small for gestational age infant differed for those with recurrent chronic villitis and we investigated whether placental pathology worsened in the second study pregnancy among those with recurrent chronic villitis.

Results:

The overall prevalence of recurrent chronic villitis in the study sample was 11.5%. Among those with chronic villitis in the first pregnancy, 54% developed chronic villitis in the second pregnancy, corresponding to an adjusted risk ratio of 2.36 (95% confidence interval: 1.92, 2.91). Recurrent chronic villitis was not associated with increased prevalence of small for gestational infant as compared with non-recurrent villitis. Among those with recurrent chronic villitis, high-grade chronic inflammation and fetal vascular malperfusion were more common in the second pregnancy as compared with the first.

Discussion:

Our results suggest that those with chronic villitis in the first pregnancy are over twice as likely to develop chronic villitis in the second pregnancy and that chronic inflammation and fetal vascular malperfusion may worsen among those with recurrent chronic villitis.

Keywords: Chronic villitis, chronic inflammation, fetal vascular malperfusion, placental pathology, small for gestational age

Introduction

Chronic villitis is a placental lesion that affects 5–15% of placentas and is characterized by chronic inflammatory cells infiltrating the chorionic villi [1]. While chronic villitis can result from infection (infectious villitis), a majority of cases are not attributed to infection (villitis of unknown etiology). Two prevailing hypotheses for the etiology of chronic villitis suggest either a response similar to allograft rejection or infection by an unidentified organism [1]. Chronic villitis is also associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, including intrauterine growth restriction [1–3] and pregnancy loss [3–5], and may be related to adverse neurodevelopment [6, 7].

Chronic villitis may also recur. Review articles suggest a recurrence of 10–15% [1, 8]. However, this is similar to the prevalence of chronic villitis in general, and thus may not support a strong risk of recurrence. Data from small (n=19 to 34), pathology-based studies of patients with multiple deliveries suggests that 32%−37% of those with chronic villitis either had chronic villitis in a prior pregnancy or go on to develop chronic villitis in a subsequent pregnancy [3, 4, 9]. Additionally, a small study of nine patients with recurrent small for gestational age infants with chronic villitis found that chronic villitis recurred in five (56%) [10]. Recurrence may also be associated with adverse outcomes, including intrauterine fetal demise and fetal growth restriction [10, 11]. Though one study reported no differences in preterm birth, fetal growth restriction, or Apgar scores between those with chronic villitis in a single pregnancy versus those with recurrent chronic villitis [9].

While these studies indicate a recurrence risk between 10–56%, studies often do not include a comparison group (i.e., the risk of developing chronic villitis in the second pregnancy among those who did not have chronic villitis in the first pregnancy). A comparison group is important because it helps to account for the baseline prevalence of chronic villitis in the sample and facilitates comparison across studies. For example, estimates of recurrent chronic villitis are based on pathology samples, which are not reflective of all deliveries, and indications for pathology may vary by institution. Further, prevalence of chronic villitis is affected by placental sampling methods, which may also vary by institution [1, 12]. The purpose of our study was to estimate the association between having chronic villitis in one pregnancy and developing chronic villitis in a subsequent pregnancy in a large cohort. We also utilized methods to partially account for selection bias in the pathology sample.

Materials and methods:

Study Sample

We obtained delivery records from singleton livebirths at a single Chicago hospital between January 2009 and March 2018. Demographic characteristics, birth outcomes, and the diagnostic text field from the placental pathology report were abstracted from medical records. The study was approved by the IRB at Northwestern University.

During the study period, 21,917 patients had two deliveries. Placental pathology reports from the first study pregnancy were available for 2,578 (12%) and 833 had placental pathology reports available for both pregnancies (4%). We additionally obtained data on 35 fetal deaths with pathology reports for both the fetal death and a prior delivery. Indications for pathologic review included abnormal placental appearance, intrauterine growth restriction, preterm delivery <34 weeks, PPROM <34 weeks, severe preeclampsia, clinical concern for TORCH infection, chorioamnionitis, or abruption, and certain neonatal conditions. Pathology reports were completed by perinatal pathologists. All placentas were grossed in a routine, systematic manner by trained staff and trimmed weight was recorded. Histologic examination included routine review of sections of the extraplacental membranes, umbilical cord, 2 full thickness parenchymal sections, biopsies of the maternal surface, and representative sections of all gross lesions. Microscopic pathology was recorded in the pathology report according to accepted terminology for the time period. Chronic villitis was identified based on presence of chronic inflammatory cells infiltrating the chorionic villi.

In addition to evaluating chronic villitis, we also investigated the prevalence of acute inflammation (AI), chronic inflammation (CI), maternal vascular malperfusion (MVM), and fetal vascular malperfusion (FVM) among those with recurrent villitis. Additional details on placental lesion ascertainment and classification in this sample have been reported elsewhere and are briefly described below [13]. Acute inflammation (AI) was determined based on Amsterdam consensus criteria and was considered high stage if either high-stage maternal AI (acute chorioamnionitis or necrotizing chorioamnionitis) or high-stage fetal AI (acute arteritis or panvasculitis or necrotizing funisitis) were present [14]. CI was summarized based on the number of compartments infiltrated by chronic inflammatory cells (chorionic plate/membranes, basal plate, villi, intervillous space, and fetal vasculature). CI was considered low grade if only one compartment affected by chronic inflammation and high grade if two or more compartments were affected [13]. MVM was scored based on the number of lesions present. One point was given for the following lesions: fibrinoid necrosis/acute atherosis, muscularization of basal plate arterioles, mural hypertrophy of membrane arterioles, basal decidual vascular thrombus, single infarct, increased syncytial knots, villous agglutination, increased perivillous fibrin deposition, distal villous hypoplasia/small terminal villous diameters, and retroplacental blood/hematoma. Two points were given for three lesions: multiple infarcts, retroplacental blood/hematoma with hemosiderin or infarct, and an SGA placenta (SGA placenta independent of other indicators of MVM was not scored). Scores of 0–1 were not considered to be MVM, scores of 2–3 were classified as low-grade MVM and scores of 4 or more were considered high-grade MVM [13]. FVM was graded based on Amsterdam consensus criteria [14]. Lesions indicative of FVM include presence of a thrombus or intramural fibrin deposition in at least one fetal vessel (umbilical, chorionic, velamentous, stem villous) and/or avascular villi/villous stromal-vascular karyorrhexis. High-grade FVM was determined based on more than one focus of avascular villi (≥45 villi) or two or more occlusive or nonocclusive thrombi in the chorionic plate or stem villi, or multiple nonocclusive thrombi.

Statistical analysis

We used a log-binomial model (binomial generalized linear model with a log link function) to estimate the risk of developing chronic villitis in the second pregnancy. We estimated the risk ratio rather than the odds ratio because chronic villitis is not a rare outcome in our pathology sample, in which case the odds ratio overestimates the risk ratio [15]. The adjusted model included race/ethnicity, interpregnancy interval, and maternal age and parity in the first study pregnancy. We also evaluated whether the prevalence of small for gestational age infant (SGA; birthweight <10th percentile for gestational age and sex [16]) differed in the second pregnancy for those with recurrent chronic villitis as compared with those with non-recurrent chronic villitis or those without chronic villitis. Additionally, among those with recurrent chronic villitis, we evaluated whether the grade or stage of the four major placental lesion categories (chronic inflammation, acute inflammation, maternal vascular malperfusion, and fetal vascular malperfusion) changed in the second study pregnancy.

In addition, to account for selection bias due to indication for pathologic review, we replicated findings using stabilized inverse probability weights. The sample was re-weighted to reflect the distribution of the sample with pathology from the first pregnancy during the study period (n=2,578). This is similar to applying a weight to account for loss to follow-up in a cohort study (we know whether chronic villitis was present in the first study pregnancy, but we do not know whether chronic villitis was present in the second study pregnancy because the placenta was not submitted to pathology). We did not re-weight the sample to reflect the distribution of the full sample with two deliveries during the study period (n=21,917), as this would not allow us to account for differences in the prevalence of placental lesions. The weight was calculated by modeling the probability of having pathology reports for two placentas as compared with having a pathology report only for the first study pregnancy. The probability model included demographic characteristics (maternal age, race/ethnicity, parity), birth outcomes (gestational age at delivery, SGA infant, method of delivery), and placental pathology (acute inflammation, chronic inflammation, fetal vascular malperfusion, maternal vascular malperfusion). In using the inverse of the calculated probability, those who are overrepresented in the analytic sample, such as preterm births (high probability of inclusion in the pathology sample), have a smaller weight and those who are underrepresented in the sample, such as term births (low probability of inclusion), have a larger weight. Weighting the sample by the inverse probability ensures that the distribution of maternal, pregnancy, and placental characteristics in the analytic sample is similar to that of the sample that would have been included if we knew the pathology in the second study pregnancy. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute INC., Cary, North Carolina) was used for statistical analysis and an alpha level of 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

Results:

Patients with two placental pathology reports (n=883) were less likely to be White and nulliparous and more likely to deliver preterm and SGA infants in the second study pregnancy as compared with those with placental pathology only for the first pregnancy (n=2,578; Table 1). Additionally, the 883 with two placental pathology reports were less likely to have acute inflammation and more likely to have chronic inflammation and maternal vascular malperfusion in the first study pregnancy. In the included sample of 883 individuals, the mean maternal age at delivery of the first study pregnancy was 31.2 years (standard deviation: 4.8), 59.6% were White, 13.8% were Hispanic, 11.8% were Black, and 8.7% were Asian. In the first study pregnancy, 31.0% delivered preterm and 17.2% delivered an SGA infant.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of those with placental pathology reports for two pregnancies as compared with those with pathology reports for only the first pregnancy (to evaluate ‘loss to follow up’).

| Mean (SD) or n (%) | Placental Pathology from both deliveries n=883 | Placental Pathology only from first pregnancy n=2,578 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age, years, first study pregnancy | 31.2 (4.8) | 31.1 (4.5) | 0.45 |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.01 | ||

| White | 526 (59.6) | 1,792 (65.0) | |

| Black | 104 (11.8) | 202 (7.3) | |

| Hispanic | 122 (13.8) | 410 (14.9) | |

| Asian | 77 (8.7) | 229 (8.3) | |

| Other | 54 (6.1) | 125 (4.5) | |

| Nulliparous, first pregnancy | 769 (87.1) | 2,500 (90.7) | <0.01 |

| Preterm birth | |||

| First pregnancy | 274 (31.0) | 565 (20.5) | <0.01 |

| Second pregnancy | 272 (30.8) | 124 (4.5) | <0.01 |

| SGA infant | |||

| First pregnancy | 152 (17.2) | 478 (17.3) | 0.94 |

| Second pregnancy | 108 (12.2) | 112 (4.1) | <0.01 |

| Acute inflammation, first pregnancy | <0.01 | ||

| None | 373 (42.2) | 992 (36.0) | |

| Low stage | 348 (39.4) | 1,114 (40.4) | |

| High stage | 162 (18.4) | 652 (23.6) | |

| Chronic inflammation, first pregnancy | 0.02 | ||

| None | 563 (63.8) | 1,878 (68.1) | |

| Low grade | 205 (23.2) | 602 (21.8) | |

| High grade | 115 (13.0) | 278 (10.1) | |

| Chronic villitis, first pregnancy | 190 (21.5) | 557 (20.2) | 0.40 |

| Maternal vascular malperfusion, first pregnancy | 0.01 | ||

| None | 526 (59.6) | 1,795 (65.1) | |

| Low grade | 188 (21.3) | 518 (18.8) | |

| High grade | 169 (19.1) | 445 (16.1) | |

| Fetal vascular malperfusion, first pregnancy | 0.46 | ||

| None | 640 (72.5) | 1,942 (70.4) | |

| Low grade | 227 (25.7) | 768 (27.9) | |

| High grade | 16 (1.8) | 48 (1.7) |

Abbreviations: SD – standard deviation

Among those with two placental pathology reports, the overall prevalence of recurrent chronic villitis was 11.5% (Table 2). Additionally, 10.0% had chronic villitis only in the first study pregnancy, 15.3% had chronic villitis only in the second study pregnancy, and 63.2% did not have chronic villitis in either pregnancy. Among those with chronic villitis in the first study pregnancy (n=190), 53.7% developed chronic villitis in the second study pregnancy. In a model adjusted for race/ethnicity, maternal age, interpregnancy interval, and parity, those with chronic villitis in the first study pregnancy were 2.59 times as likely to develop chronic villitis in the subsequent pregnancy (95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.12, 3.15; Table 3). Results were consistent in weighted models to partially correct for selection bias in the pathology sample (adjusted risk ratio: 2.36; 95% CI: 1.92, 2.91).

Table 2.

Descriptive characteristics of those with two live births with placentas submitted to pathology for the total sample and by chronic villitis status (n=883).

| Mean (SD) or n (%) | Recurrent villitis (n=102) | Villitis in 1st only (n=88) | Villitis in 2nd only (n=135) | No villitis (n=558) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age, years, first study pregnancy | 31.5 (5.0) | 31.7 (4.8) | 31.7 (4.7) | 31.0 (4.7) | 0.29 |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.16 | ||||

| White | 60 (58.8) | 55 (62.5) | 84 (62.2) | 327 (58.6) | |

| Black | 6 (5.9) | 6 (6.8) | 13 (9.6) | 79 (14.2) | |

| Hispanic | 22 (21.6) | 14 (15.9) | 15 (11.1) | 71 (12.7) | |

| Asian | 9 (8.8) | 9 (10.2) | 15 (11.1) | 44 (7.9) | |

| Other | 5 (4.9) | 4 (4.6) | 8 (5.9) | 37 (6.6) | |

| Nulliparous, first study pregnancy | 84 (82.4) | 78 (88.6) | 120 (88.9) | 487 (87.3) | 0.45 |

| Preterm birth, second study pregnancy | 29 (28.4) | 22 (25.0) | 32 (23.7) | 189 (33.9) | 0.06 |

| SGA infant, second study pregnancy | 20 (19.6) | 13 (14.8) | 25 (18.5) | 50 (9.0) | <0.01 |

Abbreviations: SD – standard deviation

Table 3.

Associations between chronic villitis in the first study pregnancy and subsequent recurrence among those with two placental pathology reports (n=883).

| Unweighted Data | Weighted Dataa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI | |

| Unadjusted | 2.76 | 2.25, 3.37 | 2.48 | 2.01, 3.07 |

| Adjustedb | 2.59 | 2.12, 3.15 | 2.36 | 1.92, 2.91 |

Abbreviations: CI – confidence interval; RR – risk ratio

Weighted to reflect the distribution of maternal, pregnancy, and placental characteristics observed among those with their first placenta submitted to pathology (inverse probability weighting)

Adjusted for maternal race/ethnicity, interpregnancy interval, and maternal age at delivery and parity at the first study pregnancy

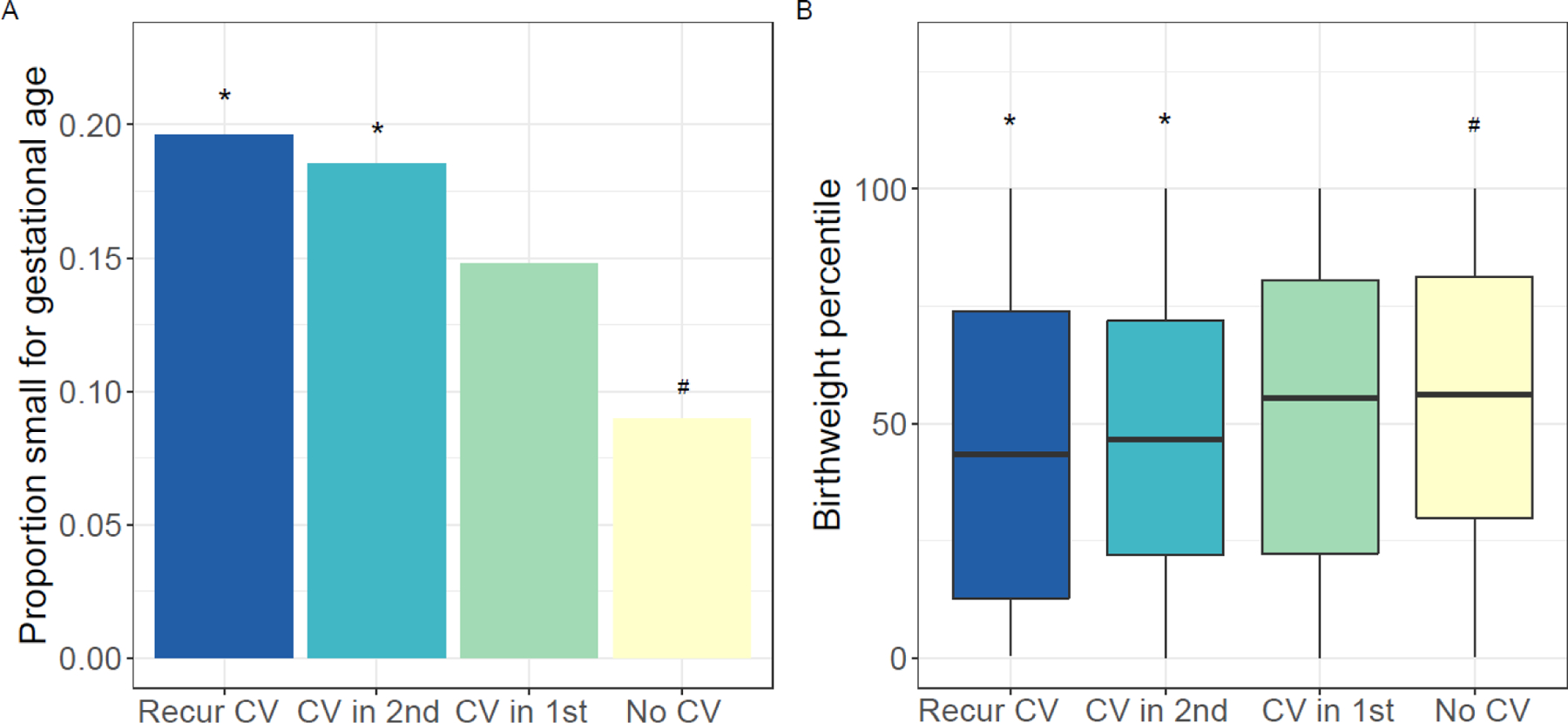

Evaluating outcomes in the second pregnancy, those with recurrent chronic villitis and those with chronic villitis only in the second pregnancy were more likely to deliver an SGA infant and to have a lower birthweight percentile than those with no chronic villitis in either study pregnancy (Figure 1). There was no difference in the prevalence of SGA infant and the distribution of birthweight percentile for those with chronic villitis only in the first pregnancy and those with no chronic villitis. There was also no statistically significant difference in the prevalence of preterm birth in the second pregnancy among those with recurrent, non-recurrent, and no chronic villitis (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Outcomes of second study pregnancy among those with two placental pathology reports (n=883): (A) proportion of small for gestational age infants by chronic villitis (CV) group and (B) distribution of birthweight percentile by CV group. Statistically significant p-values (p<0.05) indicated by # for comparison with recurrent villitis group (dark blue) and * for comparison with no CV group (yellow).

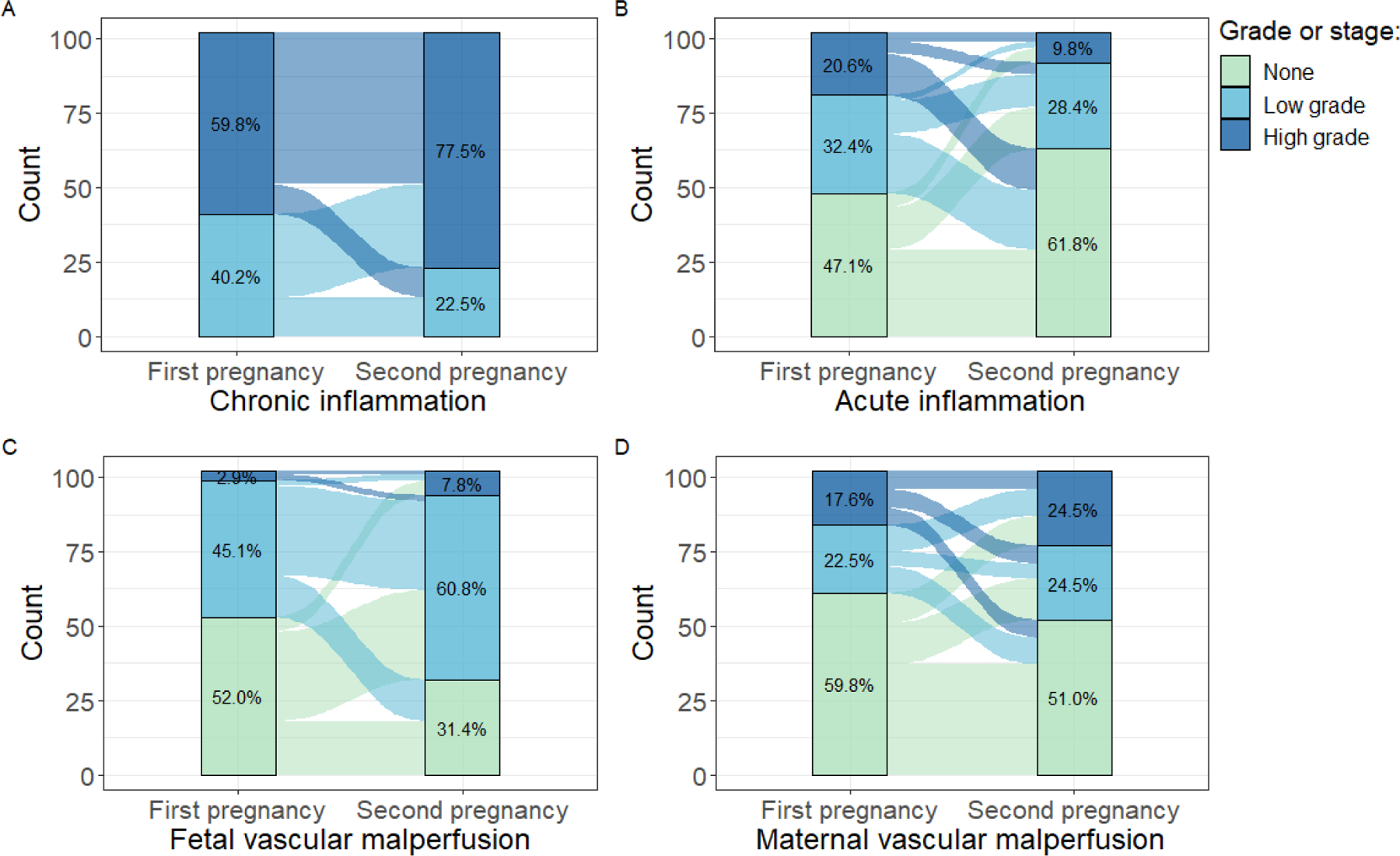

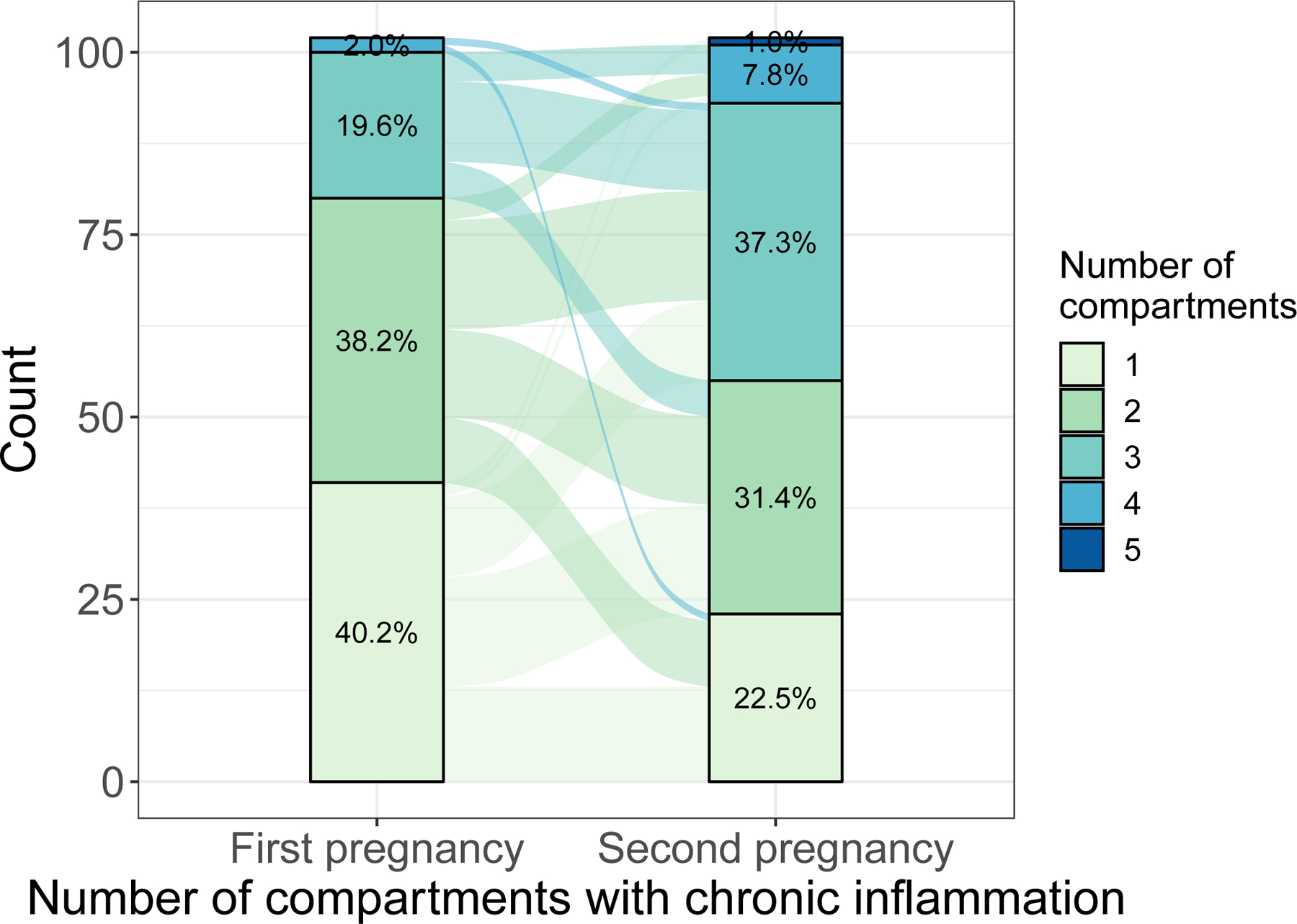

Among those with recurrent chronic villitis (n=102), high-grade chronic inflammation was more common in the second study pregnancy as compared with the first (77.5% vs. 59.8%, p<0.01, Figure 2A) and the distribution of number of compartments affected by chronic inflammation shifted to reflect a greater number of placentas with chronic inflammation in 3 or more compartments (p<0.01, Figure 3). Similarly, fetal vascular malperfusion was more common in the second study pregnancy as compared with the first (p<0.01, Figure 2C). Conversely, acute inflammation was less common in the second study pregnancy (p=0.02, Figure 2B) and no association was observed with maternal vascular malperfusion (p>0.05, Figure 2D). When comparing outcomes in the first and second study pregnancies, there was no statistically significant difference in gestational age at delivery (median difference (first – second): 0.3 weeks; p=0.49).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of placental lesions in the first and second study pregnancies among those with recurrent chronic villitis (n=102): grade of (A) chronic inflammation (p<0.01); (B) acute inflammation (p=0.02); (C) fetal vascular malperfusion (p<0.01); and (D) maternal vascular malperfusion (p>0.05). The bar on the left displays the distribution of the placental lesion category for the first study pregnancy and the bar on the right displays the distribution for the second study pregnancy. The flows between the bars show the change from the first to second study pregnancy. For example, in A, a large proportion with low-grade chronic inflammation in the first pregnancy go on to develop high-grade chronic inflammation in the second study pregnancy.

Figure 3.

Number of compartments with chronic inflammation in the first and second study pregnancy among those with recurrent chronic villitis, n=102 (p<0.01).

As a secondary analysis, we evaluated the prevalence of recurrent villitis among 35 patients who experienced a fetal death and had a placental pathology report and additionally had a prior pregnancy with a placental pathology report. In this subset, the mean gestational age at delivery for the first study pregnancy was 34.5 weeks (SD: 6.4) and the mean gestational age at delivery for the second study pregnancy (fetal death) was 25.2 weeks (SD: 7.4). Two patients had recurrent chronic villitis (5.7%), while a majority of patients (n=30; 85.7%) did not have chronic villitis in either study pregnancy.

Discussion:

Our results suggest that those who have chronic villitis in their first pregnancy are over twice as likely to develop chronic villitis in their second pregnancy as compared with those who did not have chronic villitis. Although patients with recurrent chronic villitis had a higher prevalence of SGA infant than those without chronic villitis, the prevalence of SGA infant was similar for those with recurrent chronic villitis and non-recurrent chronic villitis. However, our data show that among those with recurrent chronic villitis, the extent of chronic inflammation and fetal vascular malperfusion may worsen in the second pregnancy.

Among our sample of 883 patients with two placental pathology reports, 11.5% had recurrent chronic villitis, which reflects the prevalence (number of patients with recurrent chronic villitis divided by the number of patients with two pregnancies and pathology). This estimate is similar to review articles citing a recurrence of 10–15% [1, 8]. For an individual patient, the clinically-relevant question is, ‘what is the risk of this pathology recurring?’. Recurrence risk, defined as the risk of having chronic villitis in the second pregnancy among those with chronic villitis in the first pregnancy, is the answer to this question. Studies examining recurrence risk report estimates of 32–56% [3, 4, 9, 10]. Similarly, we found that 54% of those with chronic villitis in the first pregnancy go on to develop chronic villitis in the second pregnancy. Our results build on prior work by estimating the risk ratio, which compares the risk of developing recurrent chronic villitis to the risk of developing chronic villitis among those who did not have chronic villitis in the first pregnancy (19% in our sample). This helps to account for the underlying prevalence of chronic villitis in the sample, which may vary depending on pathology inclusion criteria and placental sampling methods [1, 12]. For comparison, Quintanilla and Rogers (2007) provide sufficient data to calculate a risk ratio [9]. Their data indicate that 32% (11/34) of those with chronic villitis in the first pregnancy develop chronic villitis in the second pregnancy and 8% (22/274) of those without chronic villitis in the first pregnancy develop chronic villitis in the second pregnancy, corresponding to an unadjusted risk ratio of 4.0 (95% CI: 2.2, 7.6). This is similar to our unadjusted risk ratio of 2.76 (95% CI: 2.25, 3.37) and illustrates the importance of a comparison group. While the risk of chronic villitis recurring appears to be greater in our sample (54% vs. 32%), the risk of developing chronic villitis among those who did not previously have chronic villitis is also greater in our sample (19% vs. 8%), which may be due to differences in the underlying populations, indications for pathology, and/or sampling techniques.

A key limitation of our work is selection bias. Only live births to patients with two placentas submitted to pathology were included in the analysis. Thus, we are missing healthy pregnancies not requiring pathologic review, as well as pregnancies that ended in miscarriage or stillbirth. Though, in our secondary analysis, only 2 of 35 patients with two pregnancies, the second ending in fetal death, had recurrent chronic villitis. Our results address the question, ‘given a placenta submitted to pathology has chronic villitis, what is the probability that chronic villitis will recur in a subsequent pregnancy?’ Given this limitation, our results may not generalize to non-pathology samples. If chronic villitis occurring in a ‘healthy’ pregnancy (not submitted to pathology) is less likely to recur, then our results may overestimate the recurrence risk of chronic villitis. However, we did partially address selection bias using inverse probability weighting, and associations persisted.

Strengths of our study include the use of a large sample with placental pathology data on two pregnancies. Placental pathology reports were also completed by perinatal pathologists using standardized reports, which facilitated text-searching to identify chronic villitis. We also sought to partially correct for selection bias by using inverse probability weighting to ensure that the distribution of the maternal, pregnancy, and placental characteristics in the sample with two pathology reports matched the distribution of those with a pathology report only for the first pregnancy.

Our findings indicate that those with chronic villitis in one pregnancy are over twice as likely to develop chronic villitis in the subsequent pregnancy (recurrent chronic villitis). Additionally, the extent of the chronic inflammation and fetal vascular malperfusion may worsen in the second study pregnancy for those with recurrent chronic villitis. Future studies should evaluate associations in a representative sample to eliminate bias due to selection into a pathology sample.

Highlights.

Those with chronic villitis are twice as likely to develop chronic villitis in a subsequent pregnancy

Prevalence of small for gestational age infant was similar in those with recurrent and non-recurrent chronic villitis

Among those with recurrent chronic villitis, chronic inflammation and fetal vascular malperfusion may worsen

Funding:

This work was supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health’s Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (award number F32HD100076), National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (award number R01MD011749), and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (award number UL1TR001422). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement:

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References:

- [1].Redline RW, Villitis of unknown etiology: noninfectious chronic villitis in the placenta, Hum Pathol 38(10) (2007) 1439–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Becroft DM, Thompson JM, Mitchell EA, Placental villitis of unknown origin: epidemiologic associations, Am J Obstet Gynecol 192(1) (2005) 264–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Feeley L, Mooney EE, Villitis of unknown aetiology: correlation of recurrence with clinical outcome, J Obstet Gynaecol 30(5) (2010) 476–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Redline RW, Abramowsky CR, Clinical and pathologic aspects of recurrent placental villitis, Hum Pathol 16(7) (1985) 727–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Redline RW, Recurrent villitis of bacterial etiology, Pediatr Pathol Lab Med 16(6) (1996) 995–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Redline RW, O’Riordan MA, Placental lesions associated with cerebral palsy and neurologic impairment following term birth, Arch Pathol Lab Med 124(12) (2000) 1785–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Torrance HL, Bloemen MC, Mulder EJ, Nikkels PG, Derks JB, de Vries LS, Visser GH, Predictors of outcome at 2 years of age after early intrauterine growth restriction, Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 36(2) (2010) 171–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Chen A, Roberts DJ, Placental pathologic lesions with a significant recurrence risk - what not to miss!, APMIS 126(7) (2018) 589–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Quintanilla N, Rogers B, Recurrent Chronic Villitis: Clinicopathologic Implications, Modern Pathology 20:29A (2007).17041565 [Google Scholar]

- [10].Labarrere C, Althabe O, Chronic villitis of unknown aetiology in recurrent intrauterine fetal growth retardation, Placenta 8(2) (1987) 167–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Russell P, Inflammatory lesions of the human placenta. III. The histopathology of villitis of unknown aetiology, Placenta 1(3) (1980) 227–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Knox WF, Fox H, Villitis of unknown aetiology: its incidence and significance in placentae from a British population, Placenta 5(5) (1984) 395–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Freedman AA, Keenan-Devlin LS, Borders A, Miller GE, Ernst LM, Formulating a Meaningful and Comprehensive Placental Phenotypic Classification, Pediatr Dev Pathol (2021) 10935266211008444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Khong TY, Mooney EE, Ariel I, Balmus NC, Boyd TK, Brundler MA, Derricott H, Evans MJ, Faye-Petersen OM, Gillan JE, Heazell AE, Heller DS, Jacques SM, Keating S, Kelehan P, Maes A, McKay EM, Morgan TK, Nikkels PG, Parks WT, Redline RW, Scheimberg I, Schoots MH, Sebire NJ, Timmer A, Turowski G, van der Voorn JP, van Lijnschoten I, Gordijn SJ, Sampling and Definitions of Placental Lesions: Amsterdam Placental Workshop Group Consensus Statement, Arch Pathol Lab Med 140(7) (2016) 698–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, Hafner JP, Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes, Am J Epidemiol 157(10) (2003) 940–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Fenton TR, Kim JH, A systematic review and meta-analysis to revise the Fenton growth chart for preterm infants, BMC Pediatr 13 (2013) 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]