Abstract

Objectives

To assess the oral health condition and oral microbial outcomes from receiving an innovative treatment regimen - Prenatal Total Oral Rehabilitation (PTOR).

Methods

This prospective cohort study included 15 pregnant women in the PTOR group who had a baseline visit before PTOR and three follow-up visits (immediate after, 2 weeks and 2 months) after receiving PTOR. A historical control group of additional 15 pregnant women was matched from a separate study based on a propensity score. Along with demographic and medical background, oral health conditions and perinatal oral health literacy were assessed. Oral samples (saliva and plaque) were analyzed to identify and quantify Streptococcus mutans and Candida species by culturing-dependent and -independent methods.

Results

Significant reductions of salivary S. mutans were observed following PTOR, the effect remained until 2-month follow-up (p < 0.05). The carriage of salivary and plaque S. mutans at the 2-month visit of the PTOR group was significantly lower than that of the control group (p < 0.05). Oral health conditions reflected by BOP and PI were significantly improved upon receiving PTOR (p < 0.05). Receiving PTOR significantly improved the perinatal oral health literacy score, and the knowledge retained until 2-month follow-up (p < 0.05).

Conclusions

PTOR is associated with an improvement in oral health conditions and perinatal oral health literacy, and a reduction in S. mutans carriage, within a 2-month follow-up period. Future clinical trials are warranted to comprehensively assess the impact of PTOR on the maternal oral flora other than S. mutans and Candida, birth outcomes, and their offspring's oral health.

Keywords: Pregnancy, Prenatal oral health care, Streptococcus mutans, Candida albicans, Total oral rehabilitation, Health benefits

Pregnancy, Prenatal oral health care, Streptococcus mutans, Candida albicans, Total oral rehabilitation, Health benefits

1. Introduction

Poor maternal and child oral health is a public health crisis with potential intergenerational health impacts. Unmet prenatal oral health needs are exacerbated among the minority and low-income women [1, 2, 3, 4]. Four in ten (39%) of the non-Latina black women suffer from dental caries during pregnancy, compared to 19% of their white counterparts. More than 40% of US pregnant women living below federal poverty suffer from dental caries, comparing to 14% of those living above the 200% of federal poverty. Research from our team [5, 6, 7, 8, 9] and others [10] indicate that the severity of dental caries also disproportionately affects the underserved pregnant women. Among low-income US pregnant women, there is a stunning average of 4 untreated decayed teeth per person [11]. Moreover, poor prenatal oral health reduces oral health-related quality of life and results in avoidable emergency dental visits for orofacial pain and infections [12, 13].

Routine oral health care during pregnancy has been demonstrated to be safe, and recommended by professional organizations, such as National Maternal and Child Oral Health Resource Center [14, 15]. However, less than 50% of US women have not had a dental checkup, while more than 75% have admitted to suffering from oral health problems during their pregnancy [12]. Our recent research revealed that one of the barriers to the utilization of prenatal oral health care is the undefined magnitude of health benefits (medical and dental) upon receiving prenatal oral health care [4]. The health benefits to be demonstrated include the impact on maternal medical and dental conditions, oral health of offspring, maternal oral diseases-related pathogens, and potentially vertical transmission of oral pathogens from mothers to children since most oral diseases have a heavy microbial involvement.

Previous interventions during pregnancy focused more on pregnant women's periodontal conditions [16, 17, 18, 19]. However, a few have examined the health benefits and oral microbial changes upon receiving dental restorative treatment for caries control during pregnancy [20, 21]. Dental caries is a transmissible, and biofilm (plaque)-dependent infectious disease [22, 23]. Traditional microbial risk markers for caries include Streptococcus mutans and Lactobacillus species [24]. Significantly, in the past decade, clinical studies have also observed and suggested the association between Candida albicans and dental caries in children and adults, together with S. mutans [7, 9, 11, 25, 26, 27]. Furthermore, despite several studies have shown that children whose mothers received prenatal oral health care had delayed S. mutans colonization and a lower carriage than those whose mother did not receive oral health care during pregnancy [28, 29, 30], changes of S. mutans in the oral cavity of the mothers upon receiving prenatal oral health care are have not been assessed.

Hence, this pilot study assessed the oral health condition and oral microbial outcomes from receiving an innovative treatment regimen - Prenatal Total Oral Rehabilitation (PTOR). The PTOR regimen targets the critical prenatal period and fully restore women's oral health to a “disease free status” before the delivery. Here, we are reporting the change of oral health conditions, oral S. mutans and Candida carriage and perinatal oral health literacy among a cohort of women who received PTOR.

2. Results

All enrolled 15 pregnant women completed V1 and V2, 13 completed V3 and V4. All study subjects in the PTOR and control groups were from low-income family with edibility for New York state-supported medical insurance determined by income level (≤138% Federal Poverty Line). The demographic-socioeconomic-medical background information are shown in Table 1. For the baseline parameters, no statistical differences were detected between the PTOR and control groups in terms of age, race, ethnicity, medical background, smoking status, tooth brushing habit, educational level, marital status, DMFT and caries severity (ICDAS) (p > 0.05).

Table 1.

Demographic-socioeconomic-medical-oral characteristics.

| Categories | Treatment (n = 15) | Control (n = 15) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline parameters | ||||

| Age (year) | 25.7 ± 7.0 | 27.9 ± 5.1 | 0.33 | |

| Gestational weeks | 26.1 ± 7.5 | 31.2 ± 2.8 | 0.03 | |

| Race | African American | 73% (11) | 47% (7) | 0.14 |

| White | 27% (4) | 53% (8) | ||

| Ethnicity | Hispanic | 7% (1) | 20% (3) | 0.29 |

| Non-Hispanic | 93% (14) | 80% (12) | ||

| Diabetes (Yes) | 7% (1) | 0% (0) | 1.00 | |

| Hypertension (Yes) | 13% (2) | 27% (4) | 0.65 | |

| Smoking (Yes) | 7% (1) | 7% (1) | 1.00 | |

| Education | ≤High school | 27% (4) | 34% (5) | 0.51 |

| Associate degree | 47% (7) | 27% (4) | ||

| ≥College | 27% (4) | 40% (6) | ||

| Marital Status | Married | 7% (1) | 7% (1) | 1.00 |

| Tooth brushing | Twice/daily | 73% (11) | 60% (9) | 0.44 |

| ≤Once/daily | 27% (4) | 40% (6) | ||

| DT | 2.4 ± 0.9 | 2.5 ± 1.5 | 0.77 | |

| DS | 3.7 ± 2.1 | 3.3 ± 1.9 | 0.78 | |

| DMFT | 7.5 ± 4.8 | 7.2 ± 3.0 | 0.86 | |

| DMFS | 18.3 ± 17.5 | 12.2 ± 6.1 | 0.32 | |

| ICDAS | 4.1 ± 1.0 |

3.6 ± 1.0 | 0.23 |

|

| Outcome parameters |

Treatment (V4) |

Control |

||

| Plaque index | 1.0 ± 0.4 | 1.9 ± 0.7 | <0.001 | |

| Salivary S. mutans carriage (x105 CFU/ml) | 0.6 ± 0.5 | 10.4 ± 16.4 | <0.01 | |

| Salivary C. albicans carriage (x102 CFU/ml) | 3.0 ± 6.9 | 25.2 ± 62.9 | 0.22 | |

| Plaque S. mutans carriage (x105 CFU/ml) | 0.7 ± 1.1 | 32.2 ± 61.3 | 0.03 | |

| Plaque C. albicans carriage (x102 CFU/ml) | 2.3 ± 6.1 | 85.1 ± 21.9 | 0.62 | |

| Prenatal Total Oral Rehabilitation (PTOR) procedure | ||||

| Total visits | 1.3 ± 0.6 | NA | NA | |

| Restored teeth number | 2.1 ± 1.2 | NA | NA | |

| Extracted teeth number | 0 | 80% (13) | NA | NA |

| 1 | 13% (2) | |||

| 2 | 7% (1) | |||

| Direct pulp-capped teeth | 0 | 93% (14) | NA | NA |

| 1 | 7% (1) | |||

DT/DS- Decayed teeth number/surface.

DMFT/DMFS - Decayed, missing, filled teeth number/surface.

All women in the PTOR group received dental prophylaxis and restorations. Briefly, 93% of the women received direct pulp capping for pulp-threatened tooth and 20% received extraction of unrestorable teeth (detailed in Table 1). The average numbers of restored teeth were 2.1 ± 1.2. All PTOR procedures were delivered within 1–2 clinical visits.

2.1. S. mutans and Candida carriage upon receiving PTOR

The changes of salivary and plaque S. mutans/C. albicans are shown in Figure 1. Overall, the carriage of S. mutans was significantly reduced immediately after PTOR and remained until 2-week and 2-month follow-up visit (p < 0.05). Importantly, the mean value of salivary S. mutans dropped below 105 CFU/ml (a threshold for high caries risk) upon receiving PTOR and maintained throughout the rest of the study visits. The reduction of C. albicans in saliva and plaque was detected in V2–V4 comparing to the baseline visit (V1), but no statistical significance was detected (p > 0.05).

Figure 1.

Study flow and microbial carriage changes upon receiving prenatal total oral rehabilitation. (A) Study flow diagram. All study mothers were enrolled before the 3rd trimester [28 gestational weeks (GA)]. Total prenatal oral rehabilitation (PTOR) was provided with 1–2 dental sessions. The PTOR includes oral hygiene, restorative procedures, direct pulp capping of pulp threatened tooth and extractions of unrestorable tooth. Study participants were followed at three additional visits post PTOR. (B) Carriage of salivary/plaque S. mutans and C. albicans. A significant reduction of salivary S. mutans was observed in V2–V4 comparing to the baseline visit (V1) [V1 vs. V2, p = 0.003; V1 vs. V3, p = 0.003; V1 vs. V4, p = 0.018]. The reduction of plaque S. mutans was detected significantly in V2 and V3 compared to V1 (p < 0.001 and p = 0.040, respectively). At V4, the plaque S. mutans remained reduced without statistical significance (p > 0.05). Importantly, the mean value of salivary S. mutans reduced to below 105 colony forming unit (CFU)/ml, which is considered as the threshold for identifying high risk individuals for dental caries. Salivary and plaque C. albicans showed a trend of reduction upon receiving PTOR but without statistical significance between the baseline and follow-up visits (p > 0.05).

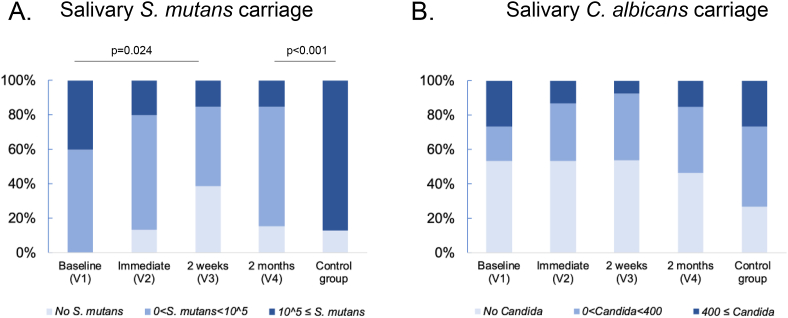

Salivary S. mutans and C. albicans were categorized into three levels based on the clinical implications (Shown in Figure 2). Since 105 is considered as threshold for high caries risk, S. mutans were scored as 0, above 0 but <105, and ≥105 CFU/ml. The percentage of women in the PTOR group who had ≥105 CFU/ml of salivary S. mutans reduced from 40% at V1, to 20% at V2, 15% at V3 and 15% at V4. Furthermore, we scored C. albicans carriage as 0, 1–399, and ≥400 CFU/ml, where the laboratory indication for oral candidiasis is 400 CFU/ml of salivary Candida carriage [31]. Among the pregnant women who received PTOR, the percentage of mothers who had ≥400 CFU/ml was reduced from 27% in V1 to 13% in V2, 8% in V3, and slightly increased to 15% in V4.

Figure 2.

Changes of salivary C. albicans and S. mutans scoring upon receiving prenatal total oral rehabilitation. (A) Salivary S. mutans scoring. The carriage of salivary S. mutans was scored as three levels: no S. mutans, above 0 but less than 105, and equal or more than 105 in CFU/ml. 105 CFU/ml indicates a threshold of high risk for dental caries. In the treatment group, the percentage of mothers with high risk of dental caries is significantly smaller in 2-week follow up visits (V3) than that of V1 (p = 0.024). Regarding the high risk for dental caries evaluated by salivary S. mutans level, the percentage of women in the treatment group at V4 was significantly lower that was in the control group (15% vs. 87%, p < 0.001). (B) Salivary C. albicans scoring. The carriage of salivary C. albicans was scored as three levels: no Candida, above 0 but less than 400, and equal or more than 400 CFU/ml. 400 CFU/ml indicates oral candidiasis-based criteria using salivary candida established by Epstein et al. [1980]. In the treatment group, the percentage of mothers with possible diagnosis of oral candidiasis is smaller in all follow up visits (V2–V4) than that of V1.

When PTOR group was compared to the control group, the salivary and plaque S. mutans carriage of women who received PTOR at V4 were significantly lower than that of the control group (p < 0.01 and p = 0.03, respectively, see Table 1). When the high risk for dental caries threshold (105 CFU/ml in saliva) was considered, more PTOR mothers remained below the caries risk threshold when compared to the control group (87% vs 15%, p < 0.001).

2.2. Changes in oral health conditions upon receiving PTOR

The oral health condition changes among the women received PTOR are shown in Figure 3. The periodontal status reflected by BOP and the oral hygiene practice reflected by PI were significantly improved upon receiving PTOR (shown in Figure 3A and 3B). The average number of interproximal BOP sites were reduced from 8.1 at V1 to 4.9 at V2 (p = 0.027). This reduction of BOP remained until 2 months after PTOR (p = 0.001). The reduction of PI was also significant between the baseline and following visits until 2 months after PTOR (V1 vs. V2, p < 0.001; V1 vs. V3, p = 0.001; V1 vs. V4, p = 0.009). A significant lower PI was seen among the mothers 2 months after receiving PTOR (1.0 ± 0.4) compared to the mothers in the control group (1.9 ± 0.7) (p < 0.001). The average orofacial pain score at the baseline visit was 1.5 at the baseline (Figure 3C). Statistical difference of orofacial pain was detected between the baseline and 2-week follow-up visit (p = 0.048), whereas, no statistical difference of orofacial pain were seen between the baseline and 2-month follow-up visit (p > 0.05).

Figure 3.

Changes of oral health conditions upon receiving prenatal total oral rehabilitation. (A) Bleeding on probing (BOP) in number of interproximal sites, (B) Plaque index (PI). The oral health reflected by BOP and PI was significantly improved upon receiving PTOR with the statistical difference seen between the baseline (V1) and follow-up visits (V2–V4). The effect of reduced BOP and PI maintained until 2 months post POTR. (C) Orofacial pain score from 0 to 10. Statistical difference was seen between the baseline and 2-week follow up visits (p = 0.048). (D) Perinatal oral health care literacy upon receiving PTOR with the maximum score of 7. Significant differences were seen regarding the total score between the baseline visit (V1) and every follow-up visits. All women were able to increase their knowledge about perinatal oral health care upon receiving PTOR. The knowledge retained until 2 months post PTOR with reaching maximum score 7.

2.3. Changes in perinatal oral health literacy upon receiving PTOR

The knowledge on perinatal oral health care was significantly improved upon receiving PTOR, reflected by the perinatal oral health literacy score [V1 vs. V2, p = 0.011; V1 vs. V3, p < 0.001; V1 vs. V4, p < 0.001] (shown in Figure 3D). The knowledge for each category was improved and retained until 2 months post PTOR (shown in Figure 4). All pregnant women answered correctly for Q1 (importance of oral hygiene in primary teeth) and Q7 (knowledge of microbial maternal transmission) for all visits, regardless of receiving PTOR. Increased knowledge was seen regarding the safety and effectiveness of fluoride (Q4 and Q5), the association between infant oral health and overall health (Q2 and Q6), and the importance of treating dental caries in children (Q3). For instance, the percentage of correct answer for fluoride water safety and effectiveness was 53% and 33% before receiving PTOR, and 100% of the women answered correctly for these two questions at the 2-month follow-up visit. Furthermore, at the baseline, 33% of the pregnant women did not know the answer for Q2 “Cavity should be filled only when it hurts in children”; importantly, 100% of the women understood that cavity should be filled regardless of the pain status and remained their knowledge by 2 months after PTOR.

Figure 4.

Changes of perinatal oral health literacy upon receiving PTOR. A total of 7 questions were used to collect information on women's literacy on perinatal oral health. All women answered correctly for Q1 and Q7 (importance of oral hygiene in primary teeth and knowledge of microbial maternal transmission), regardless of receiving PTOR. The knowledge regarding the association between infant oral health and overall health (Q2 and Q6), importance of treating dental caries in children (Q3), safety and effectiveness of fluoride (Q4-5) was improved upon receiving PTOR. Knowledge for each category retained until 2 months post PTOR.

3. Discussion

The highlights of our study include the followings:

-

1)

Assessed the impact of an innovative regimen of PTOR on oral health conditions, perinatal oral health literacy, and the carriage of cariogenic pathogens. Prenatal dental health care is beneficial; however, the magnitude of health benefits is undefined. PTOR aims to eliminate all cavitated teeth before mothers deliver their infants. The prenatal oral health interventions reported previously were caries control regimens such as caries-preventive regimen with fluoride and chlorhexidine treatment and oral environmental stabilization, including atraumatic restorative treatment, where a caries-free status of the mothers was not achieved before their delivery [20, 21, 29].

-

2)

Assessed both S. mutans and C. albicans in a 2-month follow-up period after PTOR. No study has reported the effect of prenatal oral health care on emerging cariogenic pathogens, such as C. albicans. In addition, previous studies [20] reported the reduction of S. mutans in the oral cavity, which was only observed in a short follow-up period (1-week). Our study extended the follow-up period to 2 months post-PTOR.

-

3)

Focused on the underserved group. With a few studies [20, 21, 29] conducted to assess the effect of oral health care intervention during pregnancy, no studies, to our best knowledge, have focused on the socioeconomic disadvantaged group.

-

4)

Demonstrated the safety of PTOR. An important finding is that the subjects reported reduced, not increased, orofacial pain upon receiving PTOR, which ensured the safety of PTOR among pregnant women.

Interestingly, PTOR significantly reduced the carriage of S. mutans in the oral cavity but not salivary C. albicans. One explanation could be due to the difference in preferred binding sites of S. mutans and C. albicans. S. mutans adheres to the tooth surfaces and often accumulates at the carious lesion [32, 33]. Therefore, restoring cavitated teeth reduced the binding sites for S. mutans in the oral cavity. On the contrary, oral Candida invade and infiltrate mucosal surfaces and establish the presence in the oral cavity [34, 35], therefore, PTOR alone, might not be sufficient to reduce the salivary carriage of oral Candida. In addition, a higher risk of yeast infection during pregnancy upon hormonal changes might reduce the effect of PTOR on Candida reduction, which might be seen among non-pregnant women. A combination of PTOR and antifungal topical treatment, such as Nystatin rinse, might achieve a better reduction on both bacterial and fungal species in the oral cavity.

Oral health literacy is considered a strong predictor of an individual's oral health, behavior, and eventually oral health outcomes. Lower literacy is linked to poor self-care and management, delayed oral disease diagnoses, and poor compliance to oral hygiene instructions [36]. Prenatal oral health literacy is within this scope. Maybury, Horowitz [37] reported only 53% low-income pregnant women saw a dentist during their pregnancy. Furthermore, they were unaware of caries prevention strategy and did not practice oral health care to prevent oral diseases, depicting a low rate of perinatal oral health literacy in this population. The lower literacy level can be improved through education [38] and obtaining knowledge thorough experience. The pregnant women in our study improved their knowledge on perinatal oral health by their experience of receiving dental treatment. Importantly, this obtained knowledge remained post PTOR, even 2 months after. In cognitive levels, practical experience has a positive effect on theoretical knowledge [39]. We maintain the knowledge through experiences, not only through hearing from others why and how it is essential. Therefore, more promotion strategies and policies are needed to encourage underserved pregnant women seeking prenatal oral health care to experience professional oral health care and improve oral health-related literacy.

Studies have shown the effectiveness of prenatal oral health care on the reduction of early childhood caries (ECC) and S. mutans carriage in children. Günay, Dmoch-Bockhorn [28] reported 100% of children in the intervention for prenatal oral health care mothers group remained S. mutans free by 3 years of age, while only 38.5% remained S. mutans free in the control group by age 3. Brambilla, Felloni [29] also reported that children of mothers who received prenatal oral health care had significantly lower salivary S. mutans level than those of untreated group mothers (p < 0.05). Our study only assessed the microbial changes in the mothers. The impact of PTOR on children whose mothers received PTOR remains unknown and could only be assessed with future studies that expand the observations among the offspring.

The following limitations need to be considered when interpreting our study results: 1) Limited sample size; 2) The study was only conducted in one US city. Thus, generalization to other populations is unreliable due to the small convenient sample size; 3) The control group was a historical control from another study that enrolled pregnant women at their third trimester. Although a propensity score was used to match the control to the treatment group, the gestational weeks of subjects in the treatment and control group were significantly different.

4. Conclusions

PTOR, a clinical regimen that targets the critical prenatal period and fully restores women's oral health to a "disease-free status" before the delivery, is associated with an improvement in oral health conditions, perinatal oral health literacy, and a reduction in S. mutans carriage among a cohort of underserved US pregnant women. Future clinical trials are warranted to comprehensively assess the impact of PTOR on the maternal oral flora other than S. mutans and Candida, birth outcomes, and their offspring's oral health.

5. Materials and methods

5.1. Study population

In the treatment group, this study included 15 pregnant women who received PTOR at the Perinatal Dental Clinic at University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) Eastman Institute for Oral Health (EIOH). The EIOH Perinatal Dental Clinic provides care to approximate 250/year socioeconomically deprived pregnant women in Monroe county of New York State. The PTOR includes comprehensive examination, dental cleaning, fillings to restore dental caries, tooth extractions, root canal therapy and periodontal treatment as needed. Additional 15 pregnant women in the control group were matched from subjects of a separate cohort study where patients were seen at URMC Highland Family Medicine without receiving PTOR. The reported studies were approved by the University of Rochester Research Subject Review Board (#4628 and #1248). All participants were informed of the study objects and protocols, and gave written consent prior to study activities.

5.2. Eligibility

For the group where mothers received PTOR, individuals who met for the following inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria were enrolled. The inclusion criteria were: 1) female, older than 18 years of age; 2) pregnant and before 28 weeks of gestation at baseline; 3) with 1–5 teeth with untreated dental caries. 4) did not receive dental cleaning in the past 5 months. 5) with less than 4mm periodontal pocket depth for all teeth.

The Exclusion criteria were: 1) with decisional impairment deeming incapable of making an informed decision; 2) received oral and/or systemic antifungal therapy within 90 days of the baseline study visit; 3) require premedication before dental treatment; 4) with more than 8 missing teeth, except third molars and orthodontically extracted teeth; 5) with removable dental prosthesis that are used to restore missing teeth; 6) with orofacial deformity or tumor (e.g., cleft lip/palate); 7) with severe systemic diseases (e.g., HIV infection).

The mothers in the control group met all inclusion and exclusion criteria except that they were enrolled during their third trimester (time period extending from the 28th week of gestation until delivery).

5.3. Data collection, examination and sample collection

The participants in the PTOR group were examined at 4 time points: 1) Baseline visit (V1) was conducted before subjects received PTOR; 2) the second visit (V2) was immediately (within 1 week) after the completion of PTOR; 3) the third visit (V3) and the last visit (V4) were 2 weeks and 2 months after completion of PTOR (study flow shown in Figure 1A). The matched participants in the control group only received 1 baseline visit which was chosen to match the timing of the V4 of the treatment group.

At the baseline visit, data on demographics were collected using a questionnaire. Data on the medical background and medications were self-reported and confirmed by electronic medical records (see appendix 1-medical background data collection sheet). The medical background included: 1) physician-diagnosed systemic diseases (Y/N), such as hypertension, diabetes, asthma, anxiety, depression kidney disease, etc.; 2) medications that subjects were taking at the baseline study visit; 3) smoking status (Y/N). The socioeconomical background and oral hygiene practice was collected using a questionnaire. At each study visit of the PTOR group, the perinatal oral health care literacy score (0–7) and orofacial pain using Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) score (0–10, with 10 being an unbearable pain) were collected [40].

A comprehensive oral examination was performed at the baseline and each study visit by one of two calibrated dentists in a dedicated examination room at the URMC, using standard dental examination equipment, materials and supplies. Caries were scored using DMFT (decayed, missing and filled teeth) and the ICDAS [41]. Bleeding on probing (BOP) was evaluated to assess the gingival inflammation. With a periodontal probe, the periodontal tissue was assessed to the bottom of the clinical pocket or sulcus. Interproximal sites for every existing tooth, except the third molars, were scored both from the buccal and the lingual sides [42]. Dental plaque was assessed using the Plaque Index (PI) as described by Löe [43]. Each of the four gingival areas of the tooth was given a score from 0-3. A score of 0 indicates no plaque in the gingival area, a score of 1 indicates the presence of a film of plaque adhering to the free gingival margin, a score of 2 indicates moderate accumulation of soft deposits within the gingival pocket, on the gingival margin and or adjacent tooth, a score of 3 indicates abundance of soft matter within the gingival pocket and or on the gingival margin and adjacent tooth structure. Inter- and intra-examiner agreement for the evaluated criteria was calculated by Kappa statistics, and exceeded 90% at the calibration.

Methods used for saliva and plaque sample collection were detailed previously [9, 11]. Approximately 2 ml of whole non-stimulated saliva samples were collected by spitting into a sterile 50ml centrifuge tube. Study subjects were instructed to not eat, drink or brush their teeth 2 h before the oral sample collection prior to their study visit. Supragingival plaques from the whole dentition were collected using a sterilized periodontal scaler. The plaque samples were suspended in 1ml of a 0.9% sodium chloride solution in a sterilized Eppendorf tube.

5.4. Identification and quantification of Candida spp. and S. mutans

The clinical samples (saliva and plaque) were stored on ice and transferred to the lab located at the Center for Oral Biology, UR within 2 h for laboratory testing. The saliva and plaque sample were gently vortexed and sonicated to break down the aggregated plaque before plating. The sonication cycle was repeated three times, with 10 s sonication and 30 s rest on ice. BBL™ CHROMagar™ Candida (BD, Sparks, MD, USA) was used to isolate C. albicans following methods S. mutans was isolated using Mitis Salivarius with Bacitracin selective medium and identified by colony morphology [44, 45]. Both Candida spp. and S. mutans were incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2, for 48 h before identification. Colonies of Candida spp. and S. mutans on each plate were counted and recorded as colony forming unit (CFU). Additionally, C. albicans and S. mutans were further identified from microbial colony DNA using colony polymerase chain reaction method, detail detailed previously [9, 11]. The probes used for C. albicans were forward primer 5′CGATTCAGGGGAGGTAGTGAC3′ and reverse primer 5′GGTTCGCCATAAATGGCTACCAG 3’. The probes used for S. mutans were forward primer 5′ TCGCGAAAAAGATAAACAAACA 3′ and reverse primer 5′ GCCCCTTCACAGTTGGTTAG 3’.

5.5. Statistical analysis

Propensity scores were used to select the 1:1 control group subjects from an existing cohort (186 pregnancy women, described in the study population section). The matching parameters included race, ethnicity, education, marital status, and the number of decayed, missing, and filled teeth. The characteristics of the PTOR and control groups were compared using t-test for continuous data including subjects' age, weeks of pregnancy, DFMT, ICDAS and PI; Chi-square or Fisher's exact tests for categorical data including demographic characteristics (race, ethnicity, education level, marital status) and medical background. To compare the changes of oral health conditions (BOP, PI, orofacial pain score), perinatal oral health literacy, and carriage of C. albicans and S. mutans (converted to natural log value) between the visits within the PTOR group, related-samples Friedman's Two-Way analysis was used. To compare the carriage of S. mutans and C. albicans (converted to natural log value) between the V4 of the PTOR group and the control group, independent-samples Wilcoxon rank-sum test was conducted. Fisher's exact test was used for S. mutans and C. albicans scoring distribution comparison between groups and between PTOR V4 and the control group. All statistical tests were two-sided with a significant level of 5%. R was used for propensity score matching and SAS 9.3 was used for the rest of statistical analyses.

5.6. Statement of ethics

All study subjects have given their written informed consent and that the study protocol was approved by the institute's committee on human research.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Hoonji Jang: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Nisreen Al Jallad, Yan Zeng and Ahmed Fadaak: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Tong Tong Wu: Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Hans Malmstrom and Kevin Fiscella: Analyzed and interpreted the data.

Jin Xiao: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

Xiao was supported by United States National Institutes of Health (NIDCR K23DE027412).

Wu was supported by United States National Science Foundation (NSF-CCF-1934962).

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

HLY e07871 appendix 1_V2

References

- 1.Thompson T.A., Cheng D., Strobino D. Dental cleaning before and during pregnancy among Maryland mothers. Matern. Child Health J. 2013;17(1):110–118. doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-0954-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marchi K.S., Fisher-Owens S.A., Weintraub J.A., Yu Z., Braveman P.A. Most pregnant women in California do not receive dental care: findings from a population-based study. Publ. Health Rep. 2010;125(6):831–842. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singhal A., Chattopadhyay A., Garcia A.I., Adams A.B., Cheng D. Disparities in unmet dental need and dental care received by pregnant women in Maryland. Matern. Child Health J. 2014;18(7):1658–1666. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang L., Ren J., Fiscella K.A., Bullock S., Sanders M.R., Loomis E.L. Interprofessional collaboration and smartphone use as promising strategies to improve prenatal oral health care utilization among US underserved women: results from a qualitative study. BMC Oral Health. 2020;20(1):333. doi: 10.1186/s12903-020-01327-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meng Y., Wu T., Billings R., Kopycka-Kedzierawski D.T., Xiao J. Human genes influence the interaction between Streptococcus mutans and host caries susceptibility: a genome-wide association study in children with primary dentition. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2019;11(2):19. doi: 10.1038/s41368-019-0051-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xiao J., Alkhers N., Kopycka-Kedzierawski D.T., Billings R.J., Wu T.T., Castillo D.A. Prenatal oral health care and early childhood caries prevention: a systematic Review and meta-analysis. Caries Res. 2019;53(4):411–421. doi: 10.1159/000495187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiao J., Grier A., Faustoferri R.C., Alzoubi S., Gill A.L., Feng C. Association between oral Candida and bacteriome in children with severe ECC. J. Dent. Res. 2018;97(13):1468–1476. doi: 10.1177/0022034518790941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xiao J., Kopycka-Kedzierawski D.T., Billings R.J. National Dental Practice-Based Research Network Collaborative G. Intergenerational task: helping expectant mothers obtain better oral health care during pregnancy. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2019;150(7):565–566. doi: 10.1016/j.adaj.2019.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiao J., Moon Y., Li L., Rustchenko E., Wakabayashi H., Zhao X. Candida albicans carriage in children with severe early childhood caries (S-ECC) and maternal relatedness. PloS One. 2016;11(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Azofeifa A., Yeung L.F., Alverson C.J., Beltran-Aguilar E. Dental caries and periodontal disease among U.S. pregnant women and nonpregnant women of reproductive age, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2004. J. Publ. Health Dent. 2016;76(4):320–329. doi: 10.1111/jphd.12159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xiao J., Fogarty C., Wu T.T., Alkhers N., Zeng Y., Thomas M. Oral health and Candida carriage in socioeconomically disadvantaged US pregnant women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19(1):480. doi: 10.1186/s12884-019-2618-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Editorial Majority of pregnant women have oral health problems, yet 43% don't seek dental treatment. Dentist. iq. 2015 http://www.dentistryiq.com/articles/2015/11/majority-of-pregnant-women-have-oral-health-problems.html Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thornton S.L., Minns A.B. Unintentional chronic acetaminophen poisoning during pregnancy resulting in liver transplantation. J. Med. Toxicol. 2012;8(2):176–178. doi: 10.1007/s13181-012-0218-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oral Health Care During Pregnancy . National Maternal and Child Oral Health Resource Center; 2012. A National Consensus Statement. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oral Health Care during Pregnancy and Early Childhood Practice Guidelines. New York State Department of Health; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaramillo A., Arce R., Contreras A., Herrera J.A. Effect of periodontal therapy on the subgingival microbiota in preeclamptic patients. Biomedica. 2012;32(2):233–238. doi: 10.1590/S0120-41572012000300011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Novak M.J., Novak K.F., Hodges J.S., Kirakodu S., Govindaswami M., DiAngelis A. Periodontal bacterial profiles in pregnant women: response to treatment and associations with birth outcomes in the obstetrics and periodontal therapy (OPT) study. J. Periodontol. 2008;79(10):1870–1879. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Offenbacher S., Lin D., Strauss R., McKaig R., Irving J., Barros S.P. Effects of periodontal therapy during pregnancy on periodontal status, biologic parameters, and pregnancy outcomes: a pilot study. J. Periodontol. 2006;77(12):2011–2024. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.060047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michalowicz B.S., Hodges J.S., DiAngelis A.J., Lupo V.R., Novak M.J., Ferguson J.E. Treatment of periodontal disease and the risk of preterm birth. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355(18):1885–1894. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Asad R., Ali Khan K.A., Javed T., Arshad M.B., Chaudhary A., Khan A.A. Effect of atraumatic restorative treatment on Streptococcus mutans count in saliva of pregnant women: a randomized controlled trial. Ann. King Edward Med. Univ. 2018;24(4) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Volpato F.C., Jeremias F., Spolidório D.M., Silva S.R., Valsecki Junior A., Rosell F.L. Effects of oral environment stabilization procedures on Streptococcus mutans counts in pregnant women. Braz. Dent. J. 2011;22(4):280–284. doi: 10.1590/s0103-64402011000400003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowen W.H., Burne R.A., Wu H., Koo H. Oral biofilms: pathogens, matrix, and polymicrobial interactions in microenvironments. Trends Microbiol. 2018;26(3):229–242. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2017.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim D., Barraza J.P., Arthur R.A., Hara A., Lewis K., Liu Y. Spatial mapping of polymicrobial communities reveals a precise biogeography associated with human dental caries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2020;117(22):12375–12386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1919099117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiao J., Fiscella K.A., Gill S.R. Oral microbiome: possible harbinger for children's health. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2020;12(1):12. doi: 10.1038/s41368-020-0082-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alkhars N., Zeng Y., Alomeir N., Al Jallad N., Wu T.T., Aboelmagd S. Oral Candida predicts Streptococcus mutans emergence in underserved US infants. J. Dent. Res. 2021 doi: 10.1177/00220345211012385. 220345211012385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiao J., Huang X., Alkhers N., Alzamil H., Alzoubi S., Wu T.T. Candida albicans and early childhood caries: a systematic Review and meta-analysis. Caries Res. 2018;52(1-2):102–112. doi: 10.1159/000481833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koo H., Bowen W.H. Candida albicans and Streptococcus mutans: a potential synergistic alliance to cause virulent tooth decay in children. Future Microbiol. 2014;9(12):1295–1297. doi: 10.2217/fmb.14.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Günay H., Dmoch-Bockhorn K., Günay Y., Geurtsen W. Effect on caries experience of a long-term preventive program for mothers and children starting during pregnancy. Clin. Oral Invest. 1998;2(3):137–142. doi: 10.1007/s007840050059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brambilla E., Felloni A., Gagliani M., Malerba A., García-Godoy F., Strohmenger L. Caries prevention during pregnancy: results of a 30-month study. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 1998;129(7):871–877. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jang H., Patoine A., Wu T.T., Castillo D., Xiao J. Oral microbiota and pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1):16870. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-96495-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Epstein J.B., Pearsall N.N., Truelove E.L. Quantitative relationships between Candida albicans in saliva and the clinical status of human subjects. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1980;12(3):475–476. doi: 10.1128/jcm.12.3.475-476.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ionescu A.C., Hahnel S., Cazzaniga G., Ottobelli M., Braga R.R., Rodrigues M.C. Streptococcus mutans adherence and biofilm formation on experimental composites containing dicalcium phosphate dihydrate nanoparticles. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2017;28(7):108. doi: 10.1007/s10856-017-5914-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garcia B.A., Acosta N.C., Tomar S.L., Roesch L.F.W., Lemos J.A., Mugayar L.R.F. Association of Candida albicans and Cbp(+) Streptococcus mutans with early childhood caries recurrence. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1):10802. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-90198-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou Y., Cheng L., Lei Y.L., Ren B., Zhou X. The interactions between Candida albicans and mucosal immunity. Front. Microbiol. 2021;12:652725. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2021.652725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nikou S.A., Kichik N., Brown R., Ponde N.O., Ho J., Naglik J.R. Candida albicans interactions with mucosal surfaces during health and disease. Pathogens. 2019;8(2) doi: 10.3390/pathogens8020053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baskaradoss J.K. Relationship between oral health literacy and oral health status. BMC Oral Health. 2018;18(1):172. doi: 10.1186/s12903-018-0640-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maybury C., Horowitz A.M., La Touche-Howard S., Child W., Battanni K., Qi Wang M. Oral health literacy and dental care among low-income pregnant women. Am. J. Health Behav. 2019;43(3):556–568. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.43.3.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holtzman J.S., Atchison K.A., Macek M.D., Markovic D. Oral health literacy and measures of periodontal disease. J. Periodontol. 2017;88(1):78–88. doi: 10.1902/jop.2016.160203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leask R., Cronje T., Holm D.E., Van Ryneveld L. The impact of practical experience on theoretical knowledge at different cognitive levels. J. S. Afr. Vet. Assoc. 2020;91:e1–e7. doi: 10.4102/jsava.v91i0.2042. 0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doherty S., Acworth J., Taylor S., Bennetts S. National Health and MEdical Research Council; 2011. Emergency Care Acute Pain Management Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shivakumar K., Prasad S., Chandu G. International Caries Detection and Assessment System: a new paradigm in detection of dental caries. J. Conserv. Dent. 2009;12(1):10–16. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.53335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Joss A., Adler R., Lang N.P. Bleeding on probing. A parameter for monitoring periodontal conditions in clinical practice. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1994;21(6):402–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1994.tb00737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Loe H. The gingival index, the plaque index and the retention index systems. J. Periodontol. 1967;38(6):610–616. doi: 10.1902/jop.1967.38.6.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Little W.A., Korts D.C., Thomson L.A., Bowen W.H. Comparative recovery of Streptococcus mutans on ten isolation media. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1977;5(6):578–583. doi: 10.1128/jcm.5.6.578-583.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zeng Y., Youssef M., Wang L., Alkhars N., Thomas M., Cacciato R. Identification of non- Streptococcus mutans bacteria from predente infant saliva grown on mitis-salivarius-bacitracin agar. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2020;44(1):28–34. doi: 10.17796/1053-4625-44.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

HLY e07871 appendix 1_V2

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.