Abstract

Aims

Negative emotionality is a key domain in frameworks measuring heterogeneity in alcohol use disorder (AUD), such as the Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment (ANA). Recent research has examined the construct validity of the ANA negative emotionality domain, but has not examined whether this domain demonstrates predictive validity for drinking outcomes. In this study, we examined the association between self-reported negative emotionality at baseline and drinking intensity 1 year following AUD treatment initiation. We also assessed whether coping motives for alcohol use at 6 months following treatment initiation and changes in coping motives mediated this association.

Methods

This was a secondary data analysis of a multisite prospective study of individuals entering AUD treatment (n = 263; 61.6% male; mean age = 33.8). Measures of coping motives and drinking intensity captured those who experienced a lapse to drinking. The associations between the ANA negative emotionality domain, coping motives and drinking intensity over time were assessed using a latent growth curve mediation model.

Results

The ANA negative emotionality domain at baseline was indirectly associated with greater 7–12-month drinking intensity through higher coping motives at 6 months. Negative emotionality was not related to change in coping motives over the assessment period and change in coping motives was not related to 7–12-month drinking intensity.

Conclusions

This analysis provides evidence for the predictive validity of the ANA negative emotionality domain for coping motives and drinking intensity among treatment seekers who experienced a lapse to drinking. Coping motives may be an important target in AUD treatment among those high in negative emotionality.

Short Summary: To examine predictive validity of the Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment negative emotionality domain, we assessed longitudinal associations among this domain, coping motives and drinking intensity among treatment seekers who experienced a lapse to drinking. Negative emotionality was indirectly associated with drinking intensity following treatment initiation through coping motives for alcohol use.

INTRODUCTION

Negative emotionality and the Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment

Negative affect has been widely implicated in alcohol use disorder (AUD) etiology (McHugh and Goodman, 2019; Koob et al., 2020) and in predicting and mediating AUD treatment outcomes (Swan et al., 2020). Negative emotionality is one of three domains in the Alcohol Addiction Research Domain Criteria (AARDoC), an organizational framework for behavioral, neurobiological and genetic research on processes that likely contribute to variability in AUD etiology, maintenance and treatment (Litten et al., 2015). The three AARDoC domains correspond to the Koob and Volkow (2010) stages of addiction: incentive salience (binge/intoxication), negative emotionality (withdrawal/negative affect) and executive function (preoccupation/anticipation). The negative emotionality domain reflects acquired negative states, such as anhedonia, anxiety and dysphoria, as a consequence of repeated alcohol consumption and withdrawal (Kwako et al., 2017).

One of the ultimate goals of AARDoC is to match patients to treatment based on individual differences in the domains. In an effort to advance the clinical implications of AARDoC, Kwako et al. (2016) proposed the Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment (ANA), which seeks to establish a common battery of self-report, behavioral and neuroimaging measures to assess the three AARDoC domains.

Research validating the ANA has focused on self-report measures hypothesized to reflect these three domains (Kwako et al., 2019; Votaw et al., 2020; Stein et al., 2021). Kwako et al. (2019) confirmed the factor structure of the ANA and provided evidence for the construct validity of these domains. Recent research from our group replicated and extended these findings, focusing on the ANA negative emotionality domain (Votaw et al., 2020). We demonstrated that self-report measures of depression and anxiety symptoms, trait anger and negative affective consequences of alcohol use were useful and practical indicators of the negative emotionality domain. This domain was unidimensional, invariant across time and sex, and concurrently associated with drinking intensity and coping motives among individuals seeking treatment for AUD.

Coping motives for alcohol use

The motivational model of alcohol use posits that four motives subtypes, including coping (e.g. relieving negative affect), enhancement (e.g. increasing positive affect), social (e.g. increasing positive experiences with peers) and conformity (e.g. avoiding social rejection), characterize reasons for drinking. Central to this model is that motives are the most proximal factor in the decision to drink, mediating the association between more distal factors and alcohol use outcomes (Cox and Klinger, 1988; Cooper et al., 2015). Accordingly, negative emotional states and traits influence the likelihood of drinking to cope with negative emotions, which in turn results in greater alcohol-related problems due to negative reinforcement processes (Cox and Klinger, 1988; Cooper et al., 2015). A large body of research has supported these hypotheses (Cooper et al., 2015), including among those receiving AUD treatment (Galen et al., 2001; Kushner et al., 2001; Molnar et al., 2010). Consistent with this model, it is possible that the ANA negative emotionality domain is associated with alcohol outcomes indirectly through coping motives.

Current study

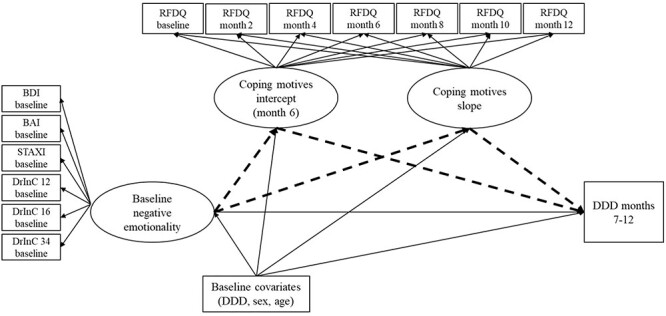

Little is known about the predictive validity of the negative emotionality domain. The aim of the present analysis was to examine prospective associations between the ANA negative emotionality domain, coping motives and drinking intensity among individuals in AUD treatment via a longitudinal mediation model (Fig. 1). We hypothesized that negative emotionality at treatment initiation would predict greater coping motives at 6 months following treatment initiation, less reduction in coping motives across the 12-month assessment period and greater drinking intensity (drinks per drinking day (DDD)) at 12 months following treatment initiation. We also hypothesized that greater coping motives at 6 months and less reduction in coping motives across the assessment period would mediate the association between baseline negative emotionality and 12-month drinking intensity.

Fig. 1.

Hypothesized latent growth curve mediation model of negative emotionality, coping motives and drinking outcomes over time. DrInC Item 12 = I have been unhappy because of my drinking, DDD = drinks per drinking day, BDI = Beck Depression Inventory, BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory, STAXI = State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory - Trait Anger Subscale, DrInC Item 16 = I have felt guilty or ashamed because of my drinking, DrInC Item 34 = I have lost interest in activities or hobbies because of my drinking, RFDQ = Reasons for Drinking Questionnaire negative emotions subscale. Hypothesized mediation is indicated by dashed lines. The quadratic slope, though included in the full mediation model, is not presented in the figure, given that it was not initially hypothesized and that it was not included in any structural paths.

METHOD

Data source and participants

We utilized data from the Relapse Replication and Extension Project (RREP) (Lowman et al., 1996), a multisite prospective observational study on predictors of alcohol relapse (Marlatt, 1996). Participants in RREP were recruited at the time of admission from 15 community AUD treatment programs across three sites (Albuquerque, NM; Buffalo, NY; Providence, RI). For the current study, we included only those participants (n = 263) from the Albuquerque, NM, and Buffalo, NY, sites because several measures of interest were only administered at these sites.

Participants met criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence according to the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM-III-R (DIS-R; Robins et al., 1989), could complete all study procedures, and had completed alcohol detoxification. Exclusion criteria included severe drug use disorders, intravenous drug use in the previous 6 months and major psychiatric disorders or cognitive impairment. See Lowman et al. (1996) for detailed study methodology.

Measures

The baseline assessment was completed at the time of treatment admission, after which participants completed six follow-up assessments every 2 months. All participants were receiving treatment for AUD, but treatment modality and time in treatment were not assessed.

Indicators of negative emotionality

All indicators of the negative emotionality latent construct included in the present analysis were self-report measures administered at baseline. Rationale for including each indicator is briefly presented below. Additional rationale as well as information on construct validity, measurement invariance and how these indicators differ from other assessments of the ANA are reported in Votaw et al. (2020).

Beck Depression Inventory and Beck Anxiety Inventory

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) are 21-item measures of the severity of past week depression and anxiety symptoms, respectively (Beck et al., 1988a, 1988b). Items are rated from 0 to 3 and total scores are a sum of all items, ranging from 0 to 63. In the present sample, internal consistency reliability was excellent for the BDI (α = 0.90) and BAI (α = 0.93). The BDI and BAI were included as indicators in the present analysis, given that both were originally proposed as measures of the negative emotionality domain (Kwako et al., 2016).

Spielberger State–Trait Anger Expression Inventory

The 10-item trait anger subscale of the State–Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI) is designed to measure a predisposition toward anger (Spielberger and Sydeman, 1994). Items are rated from 1 to 4, with scores ranging from 10 to 40. Internal consistency reliability in the present sample was α = 0.88. The STAXI was included in the current study, given aggression had the highest loading on the negative emotionality domain in a previous ANA validation study (Kwako et al., 2019).

Drinker Inventory of Consequences

The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC) is a 50-item questionnaire of consequences over the previous 3 months (Miller et al., 1995). Three items assessing negative affective consequences of alcohol use were utilized: ‘I have been unhappy because of my drinking’ (DrInC Item 12), ‘I have felt guilty or ashamed because of my drinking’ (DrInC Item 16) and ‘I have lost interest in activities or hobbies because of my drinking’ (DrInC Item 34). Response options ranged from never (rated as 1) to daily or almost daily (rated as 4). These items were included as indicators because the ANA negative emotionality domain reflects acquired negative affectivity with chronic alcohol consumption (Kwako et al., 2017).

Indicators of latent growth curve models

Reasons for Drinking Questionnaire

The 16-item Reasons for Drinking Questionnaire (RFDQ) was developed to meet the aims of the RREP study (Zywiak et al., 1996). The RFDQ was administered at each assessment and asked about reasons for drinking during a recent lapse, with three subscales: negative emotions, social pressure and urges/withdrawal. Participants only completed this questionnaire if they consumed alcohol since the prior assessment and data were coded as missing if participants did not drink. This reflects the phrasing of commonly utilized measures of drinking motives, which require individuals to report how frequently their drinking is influenced by different reasons for drinking (Cooper, 1994), and the unclear validity of measures of drinking motives in the absence of drinking (Votaw and Witkiewitz, 2020).

In the present study, the following seven items from the negative emotions subscale were used to assess coping motives for alcohol use during the most recent lapse: ‘I felt angry or frustrated, either with myself or because things were not going my way’, ‘I felt anxious or tense’, ‘I felt sad’, ‘I felt ill or in pain or uncomfortable because I wanted a drink’, ‘I felt angry or frustrated because of my relationship with someone else’, ‘I felt worried or tense about my relationship with someone else’ and ‘I felt others were being critical of me’. Responses to items were rated on a Likert-type scale (0 = not at all important, 10 = very important; scores range from 0 to 70). The RFDQ negative emotions subscale demonstrated good to excellent internal consistency at all time points (Cronbach’s α = 0.84–0.91).

Covariates and drinking outcomes

Demographics

The Comprehensive Drinker Profile was administered at baseline to collect demographic data. Participants’ self-reported sex and age were included as covariates, given these variables have been previously associated with negative emotionality and drinking outcomes (Sliedrecht et al., 2019; Votaw et al., 2020).

Form 90 Timeline Followback

The Timeline Followback (TLFB) method was utilized to retrospectively collect data on daily drinking (Sobell and Sobell, 1992). At baseline, the TLFB captured daily drinking in the 90 days prior to the assessment. The TLFB was administered in bimonthly intervals assessing daily drinking over 60 prior days at each assessment. Average DDD over the baseline assessment period (covariate) and follow-up months (drinking outcome) were calculated from TLFB data. We focused on drinking intensity, as opposed to other drinking outcomes, given that the RFDQ was only administered if a participant lapsed and DDD could be used as a measure of drinking intensity among those who consumed alcohol. To be consistent with the RFDQ, DDD data was coded as missing, as opposed to zero drinks, if the participant did not drink over a specified assessment period. Previous studies have demonstrated the reliability and validity of the TLFB for intervals up to 18 months (Sobell and Sobell, 1992).

Statistical analyses

The associations between the negative emotionality domain, coping motives and DDD over time, as presented in Fig. 1, were assessed within a structural equation modeling framework. To evaluate model fit across models, we used model fit criteria suggested by Hu and Bentler (1999), including a non-significant χ2 test, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) > 0.90 (acceptable) > 0.95 (optimal) and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) < 0.06.

Models were estimated in Mplus 8.2 (Muthén and Muthén, 2017) using maximum likelihood estimation. Individuals with missing data on independent variables were not included in analyses and sample sizes for each estimated model are reported below. There was substantial missing data on the RFDQ negative emotions subscale across the assessment period (Table 1), given that this scale was only administered if participants reported a drinking episode. In general, missing data on the RFDQ negative emotions subscale across the follow-up assessment period was associated with greater baseline DDD (Ps < 0.05), but was not associated with 7–12-month DDD or age. Sex was associated with missing data on the RFDQ negative emotions subscale at the 6-month follow-up, such that males were more likely to have missing data (P < 0.05); sex was not associated with missing data on this subscale at any other assessment. Missing not at random models indicated that missing data did not influence parameter estimates and was not influenced by the estimated parameters in the latent growth curve model (see Supplementary Table S1 for more details).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations between select primary variables (not including all RFDQ time points)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Male sex | |||||||||||||

| 2. Age | 0.02 | ||||||||||||

| 3. DDD baseline | 0.23** | 0.07 | |||||||||||

| 4. DDD months 7–12 | 0.23** | 0.09 | 0.52** | ||||||||||

| 5. BDI baseline | −0.02 | 0.06 | 0.20** | 0.19* | |||||||||

| 6. BAI baseline | −0.10 | −0.01 | 0.23** | 0.12 | 0.54** | ||||||||

| 7. STAXI Trait Anger baseline | −0.07 | −0.19** | 0.12 | 0.20** | 0.35** | 0.21** | |||||||

| 8. DrInC Item 12 baseline | −0.17** | 0.14* | 0.22** | 0.20** | 0.37** | 0.31** | 0.20** | ||||||

| 9. DrInC Item 16 baseline | −0.12 | 0.05 | 0.23** | 0.15* | 0.28** | 0.20** | 0.14* | 0.80** | |||||

| 10. DrInC Item 34 baseline | −0.18** | 0.15* | 0.28** | 0.16* | 0.31** | 0.19** | 0.14 | 0.51** | 0.46** | ||||

| 11. RFDQ baseline | −0.22** | 0.14* | 0.15* | 0.16* | 0.34** | 0.26** | 0.22** | 0.33** | 0.23** | 0.21** | |||

| 12. RFDQ month 6 | −0.05 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.23** | 0.23* | 0.15 | 0.27** | 0.21* | 0.06 | 0.29** | ||

| 13. RFDQ month 12 | −0.02 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.33** | 0.23** | 0.23* | 0.13 | 0.19* | 0.11 | 0.21* | 0.31** | 0.55** | |

| # Participants with data | 263 | 263 | 259 | 164 | 251 | 259 | 239 | 236 | 234 | 216 | 247 | 110 | 105 |

| Mean (SD) or % | 61.6% | 33.8 (8.1) | 17.6 (11.7) | 12.4 (9.4) | 15.1 (10.2) | 13.2 (10.9) | 21.4 (6.4) | 3.0 (1.0) | 3.0 (1.0) | 2.8 (1.0) | 30.1 (19.2) | 22.8 (19.2) | 23.6 (20.3) |

DDD = drinks per drinking day, BDI = Beck Depression Inventory, BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory, STAXI = State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory - Trait Anger Subscale, DrInC Item 12 = I have been unhappy because of my drinking, DrInC Item 16 = I have felt guilty or ashamed because of my drinking, DrInC Item 34 = I have lost interest in activities or hobbies because of my drinking, RFDQ = Reasons for Drinking Questionnaire negative emotions subscale.

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Confirmatory factor analysis of the negative emotionality domain

First, we assessed the unidimensional latent factor structure of the negative emotionality domain at baseline (n = 262) using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Indicators were BDI total score, BAI total score, STAXI trait anger subscale, and DrInC Items 12, 16 and 34. The latent factor variance was set to one for model identification. We modeled correlated residuals for the three DrInC items, given conceptual and methodological overlap.

Latent growth curve model of coping motives

Next, we estimated an unconditional latent growth curve model of coping motives with no predictors to determine the optimal shape (e.g. linear, quadratic) of the growth trajectory (n = 254). Parameters estimated include information about the average level of coping motives at a specified time point (intercept) and the average change over time in coping motives (slope). Indicators of the latent growth curve model of coping motives were RFDQ scores at baseline, 2-, 4-, 6-, 8-, 10- and 12-month follow-up. The intercept for the growth model was set at the 6-month follow-up and we tested models with both linear and quadratic slopes.

Coping motives mediating the association between negative emotionality and alcohol treatment outcomes

Lastly, we tested whether coping motives over time mediated the association between negative emotionality and drinking intensity (n = 259; Fig. 1) using the product of coefficients approach with bootstrapping (nboot = 1000 samples) to obtain 95% confidence intervals of the mediated effects (MacKinnon, 2012). The mediation model included the coping motives growth factors regressed on the negative emotionality domain (a-paths) and DDD over follow-up months regressed on the coping motives slope and intercept (b-paths), and the baseline negative emotionality domain (c′-path). Baseline DDD, sex and age were included in the models as covariates.

RESULTS

Demographics, descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations

Participants were mostly male (61.6%) with average age of 33.8 (SD = 8.1) years. Participants primarily identified as non-Hispanic White (52.9%), followed by Black or African American (21.7%), Hispanic (17.1%), American Indian or Alaskan Native (4.9%) and other racial/ethnic identity (3.4%). A majority participants were not married or cohabitating (77.9%) and were currently unemployed (60.3%), with an average of 12.3 (SD = 2.2) years of education. Depression and anxiety were commonly reported, with 33.2% in the range of ‘mild to moderate’ depression, 24.0% in the range of ‘moderate to severe’ depression and 9.6% in the range of ‘severe’ depression on the BDI. On the BAI, 30.9% were in the range of ‘mild to moderate’ anxiety, 15.4% were in the range of ‘moderate to severe’ anxiety and 9.3% were in the range of ‘severe’ anxiety. Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations are presented in Table 1.

CFA of the negative emotionality domain

A single-factor CFA model with six indicators demonstrated excellent fit to the data (X2(6) = 5.026, P = 0.540; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA (90% CI) = 0.000 (0.000, 0.073)). Standardized factor loadings, standard errors, P-values and R2 estimates for each indicator and residual correlations are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Standardized factor loadings, standard errors, P-values and R2 estimates for each indicator in the negative emotionality CFA model

| Factor loadings | Standard errors | P-value | R 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDI | 0.861 | 0.064 | <0.001 | 0.741 |

| BAI | 0.619 | 0.059 | <0.001 | 0.384 |

| STAXI Trait Anger | 0.393 | 0.064 | <0.001 | 0.154 |

| DrInC Item 12 | 0.436 | 0.067 | <0.001 | 0.190 |

| DrInC Item 16 | 0.328 | 0.068 | <0.001 | 0.107 |

| DrInC Item 34 | 0.353 | 0.068 | <0.001 | 0.125 |

| Residual correlations | Standard errors | P-value | ||

| DrInC Item 12 with DrInC Item 16 | 0.771 | 0.028 | <0.001 | |

| DrInC Item 12 with DrInC Item 34 | 0.429 | 0.059 | <0.001 | |

| DrInC Item 16 with DrInC Item 34 | 0.385 | 0.061 | <0.001 |

BDI = Beck Depression Inventory, BAI = Beck Anxiety Inventory, STAXI = State Trait Anger Expression Inventory—Trait Anger Subscale, DrInC Item 12 = I have been unhappy because of my drinking, DrInC Item 16 = I have felt guilty or ashamed because of my drinking, DrInC Item 34 = I have lost interest in activities or hobbies because of my drinking.

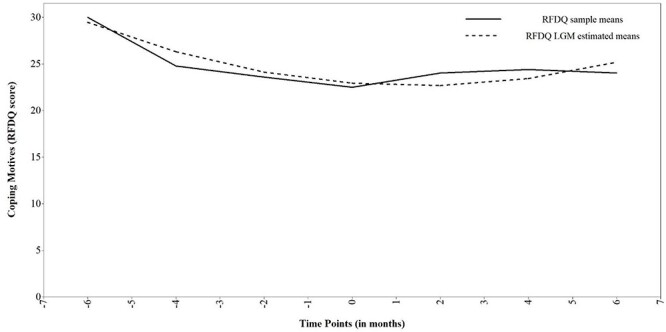

Latent growth curve model of coping motives

Results of the unconditional latent growth curve models of coping motives indicated that a model with a quadratic slope (X2(22) = 13.594, P = 0.915; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA (90% CI) = 0.000 (0.000, 0.020)) provided a better fit to the data than a linear model (X2(23) = 25.162, P = 0.342; CFI = 0.987; RMSEA (90% CI) = 0.019 (0.000, 0.056)). Due to an estimated negative residual variance for the quadratic slope, we constrained this variance to zero. The estimated mean of RFDQ negative emotions scores at the 6-month follow-up (intercept) was 22.93 (SE = 1.26, P < 0.001), and there was a significant linear decrease in coping motives across the assessment period (b (SE) = −0.36 (0.15), P = 0.017). In addition, the quadratic slope was positive and statistically significant, representing an increase in RFDQ negative emotions scores over time, following an initial decrease (b (SE) = 0.12 (0.04), P = 0.001). There was statistically significant variability in both the intercept (variance (SE) = 165.20 (22.62), P < 0.001) and linear slope (variance (SE) = 1.00 (0.47), P = 0.032). A significant correlation between the coping motives intercept and linear slope (r = 0.47, P = 0.006) indicated that higher RFDQ negative emotions scores at the 6-month follow-up were associated with greater increases in RFDQ negative emotions scores over time. Sample means and estimated means from the coping motives latent growth curve model are presented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Sample means and estimated means from the coping motives latent growth curve model. RFDQ = Reasons for Drinking Questionnaire negative emotions subscale. Fixed time intervals were coded as −6, −4, −2, 0, 2, 4 and 6 to represent baseline, 2-, 4-, 6-, 8-, 10- and 12-month follow-up, respectively.

Coping motives mediating the association between negative emotionality and alcohol treatment outcomes

Lastly, we tested whether coping motives over time mediated the association between baseline negative emotionality and 7–12-month follow-up DDD (Fig. 1). This full mediation model provided adequate fit to the data based on RMSEA and CFI (X2(109) = 191.298, P < 0.001; CFI = 0.900; RMSEA (90% CI) = 0.054 (0.041, 0.066)), although the X2 test indicated poor fit.

Path coefficients for the full mediation model are presented in Table 3. The baseline negative emotionality latent factor was associated with the coping motives intercept, and the coping motives intercept (6-month follow-up) was associated with 7–12-month DDD. Results supported a significant indirect effect of baseline negative emotionality predicting DDD at follow-up months 7–12 through the coping motives intercept at 6-month follow-up (‘indirect effect’ = 1.299, 95% CI = 0.139, 3.009). The coping motives slope was not associated with baseline negative emotionality or DDD, and the indirect effect of the coping motives slope in the association between baseline negative emotionality and drinking outcomes was not significant (‘indirect effect’ = −0.010, 95% CI = −1.332, 1.484). There was no direct effect of the baseline negative emotionality domain on 7–12-month follow-up DDD with coping motives included in the model.

Table 3.

Unstandardized path coefficients and R2 estimates from the full mediation model (coping motives over time mediating the association between the baseline negative emotionality latent factor and DDD at months 7–12)

| Outcomes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictors | Baseline negative emotionality | Coping motives intercept | Coping motives slope | DDD months 7–12 |

| Baseline negative emotionality | 6.626 (1.388)** | −0.036 (0.186) | −0.002 (1.727) | |

| Baseline DDD | 0.034 (0.009)** | 0.025 (0.108) | −0.010 (0.016) | 0.350 (0.127)** |

| Sex | −0.446 (0.195)* | −3.498 (2.271) | 0.533 (0.336) | 3.565 (4.812) |

| Age | 0.003 (0.009) | 0.193 (0.118) | −0.002 (0.018) | 0.003 (0.143) |

| Coping motives intercept | 0.196 (0.092)* | |||

| Coping motives slope | 0.272 (6.646) | |||

| R 2 | 0.142 | 0.415 | 0.096 | 0.353 |

Sex was coded female = 0 and male = 1.

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

The ANA, an extension of AARDoC, is a framework for measuring heterogeneity in AUD to better understand the development and maintenance of AUD and to inform personalized treatment (Litten et al., 2015; Kwako et al., 2016). The aim of this secondary data analysis study was to evaluate longitudinal relationships among the ANA negative emotionality domain, coping motives and drinking intensity among treatment seekers with AUD who experienced a lapse to drinking. The ultimate goal of this study was to evaluate the predictive validity of the ANA negative emotionality domain, as assessed with self-report measures, and to assess the potential utility of targeting this domain in AUD treatment. Consistent with hypotheses, the negative emotionality domain at baseline was indirectly associated with greater drinking intensity 12 months following treatment initiation through higher coping motives 6 months following treatment initiation. Contrary to hypotheses, baseline negative emotionality was not related to change in coping motives and change in coping motives was not related to drinking intensity 12 months following treatment initiation.

Results of the present study extend previous findings from our research group (Votaw et al., 2020) and a study by Kwako et al. (2019) on the concurrent validity of the ANA negative emotionality domain. In the present analysis, we provided evidence for the predictive validity of the ANA negative emotionality domain, indicated by prospective relationships between baseline negative emotionality and coping motives and drinking intensity across a 12-month follow-up period. These findings suggest that self-report assessments of the negative emotionality domain may predict the maintenance of heavier alcohol use via negative reinforcement drinking. Yet, it is important to note that our measures of drinking intensity and motives for alcohol use only captured treatment seekers with AUD who experienced a lapse to drinking. Future studies are needed to assess the predictive validity of the negative emotionality domain for a range of drinking-related outcomes among those without AUD, non-treatment seekers with AUD and treatment seekers who maintain abstinence.

The finding that negative emotionality was indirectly associated with greater drinking intensity through higher coping motives is consistent with the motivational model of alcohol use (Cox and Klinger, 1988; Cooper et al., 2015). This finding also has clinical implications and provides a signal for personalizing AUD treatment to those high in negative emotionality. For example, individuals with greater negative emotionality may benefit from treatments that target drinking in response to negative affect, such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), Affect Regulation Training, behavioral activation and Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention (MBRP) (Stasiewicz et al., 2013; Carroll and Kiluk, 2017; Swan et al., 2020). Indeed, there is evidence that certain AUD treatments, including CBT, MBRP and acamprosate, are more effective for those with high negative affect (Roos et al., 2017a) and those who drink to reduce negative emotions (Anker et al., 2016; Roos et al., 2017b). Types of treatment received by participants in the present analysis was not assessed, and therefore future work is needed to determine if greater negative emotionality moderates response to interventions hypothesized to reduce drinking in response to negative affect. Such studies will help to establish the precision medicine applications of the ANA domains.

Negative emotionality at baseline was not related to change in coping motives over the assessment period and change in coping motives was not related to drinking intensity 12 months following treatment initiation. These findings indicate that the coping motives linear slope over time was similar across levels of negative emotionality, with all participants experiencing a decrease in coping motives, on average. It is possible that participants experienced an average decrease in coping motives, regardless of negative emotionality, due to receiving treatment. The lack of association between change in coping motives and drinking quantity is consistent with conflicting findings from previous analyses. One previous study found that reductions in coping motives during CBT were associated with decreases in cannabis use frequency, dependence severity and problems (Banes et al., 2014), whereas another study found that coping motives did not change, on average, during substance use treatment and changes in coping motives were not associated with post-treatment drug use days (Wolitzky-Taylor et al., 2018). Equivocal results might be attributable to differences in language across measures of motives, with prior studies assessing general reasons for substance and the present study assessing reasons for experiencing a lapse to alcohol use. In the present study, motives assessed at follow-up might have greater validity than those assessed at baseline, given that they were anchored to a specific recent lapse. Taken together with the finding that the coping motives intercept ‘did’ mediate the association between negative emotionality and drinking intensity, absolute levels of coping motives might have a greater impact on drinking outcomes than change in motives over time.

Limitations and future directions

This study had several limitations. Measures of coping motives and drinking intensity used in the present study demonstrated a substantial amount of missing data, given that they were only administered to participants who had experienced a lapse. However, missing not at random models indicated that missing data did not substantially impact and was not impacted by estimated model parameters. The full mediation model only provided adequate fit to the data, and the results of the model should be interpreted with caution. Similarly, this study, though longitudinal, only represents correlations between variables and we cannot make conclusions about causal relationships among negative emotionality, coping motives and drinking intensity.

We were limited to measures administered to participants in the parent study (Lowman et al., 1996), and thus we could not assess behavioral and neuroimaging indicators of the negative emotionality domain, as originally proposed by Kwako et al. (2019). Future work must determine if such multimodal indicators increase the validity of this domain, above and beyond self-report indicators. The measure of coping motives, the RFDQ negative emotions subscale, was originally developed to meet the aims of the parent study (Zywiak et al., 1996) and has not been as thoroughly validated as other measures of drinking motives (Cooper et al., 2015). Finally, in the present analysis, AUD diagnoses were based on DSM-III-R criteria (Lowman et al., 1996) and major psychiatric disorders were exclusionary. Future studies are needed to determine if these results replicate in contemporary samples and among those with co-occurring AUD and psychiatric disorders.

CONCLUSIONS

In sum, this study examined longitudinal relationships among the ANA negative emotionality domain, coping motives for alcohol use and drinking intensity among treatment seekers with AUD who experienced a lapse to drinking. These results add to a growing body of literature indicating that the ANA negative emotionality domain can be validly assessed using self-report measures of depression, anxiety, anger and negative affective consequences of drinking (Kwako et al., 2019; Votaw et al., 2020). This study also provides initial evidence for the utility of treatments reducing drinking in response to negative affect among those high in negative emotionality. To further establish the applicability of the ANA to precision medicine efforts, it will be important to determine which treatment modalities are best suited to targeting coping motives and drinking outcomes among those high in negative emotionality.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Victoria R Votaw, Department of Psychology, University of New Mexico, 1 University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131, USA; Center on Alcohol, Substance Use, and Addictions, University of New Mexico, 2650 Yale SE MSC11-6280, Albuquerque, NM 87106, USA.

Elena R Stein, Department of Psychology, University of New Mexico, 1 University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131, USA; Center on Alcohol, Substance Use, and Addictions, University of New Mexico, 2650 Yale SE MSC11-6280, Albuquerque, NM 87106, USA.

Katie Witkiewitz, Department of Psychology, University of New Mexico, 1 University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131, USA; Center on Alcohol, Substance Use, and Addictions, University of New Mexico, 2650 Yale SE MSC11-6280, Albuquerque, NM 87106, USA.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health (award numbers R01AA022328, T32AA018108, F31AA028971, and F31AA029266). The content is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

References

- Anker JJ, Kushner MG, Thuras P et al. (2016) Drinking to cope with negative emotions moderates alcohol use disorder treatment response in patients with co-occurring anxiety disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend 159:93–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banes KE, Stephens RS, Blevins CE et al. (2014) Changing motives for use: Outcomes from a cognitive-behavioral intervention for marijuana-dependent adults. Drug Alcohol Depend 139:41–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G et al. (1988a) An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol 56:893–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Carbin MG. (1988b) Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev 8:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Kiluk BD. (2017) Cognitive behavioral interventions for alcohol and drug use disorders: Through the stage model and back again. Psychol Addict Behav 31:847–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. (1994) Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychol Assess 6:117–28. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Kuntsche E, Levitt A et al. (2015) Motivational models of substance use: A review of theory and research on motives for using alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco. In Sher KJ (ed). The Oxford Handbook of Substance Use Disorders, New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press; Vol. 1, 375–421. [Google Scholar]

- Cox WM, Klinger E. (1988) A motivational model of alcohol use. J Abnorm Psychol 97:168–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galen LW, Henderson MJ, Coovert MD. (2001) Alcohol expectancies and motives in a substance abusing male treatment sample. Drug Alcohol Depend 62:205–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling 6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Powell P, White A. (2020) Addiction as a coping response: Hyperkatifeia, deaths of despair, and COVID-19. Am J Psychiatry 177:1031–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20091375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Volkow ND. (2010) Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology 35:217–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner MG, Thuras P, Abrams K et al. (2001) Anxiety mediates the association between anxiety sensitivity and coping-related drinking motives in alcoholism treatment patients. Addict Behav 26:869–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwako LE, Momenan R, Grodin EN et al. (2017) Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment: A reverse translational approach. Neuropharmacology 122:254–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwako LE, Momenan R, Litten RZ et al. (2016) Addictions neuroclinical assessment: A neuroscience-based framework for addictive disorders. Biol Psychiatry 80:179–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwako LE, Schwandt ML, Ramchandani VA et al. (2019) Neurofunctional domains derived from deep behavioral phenotyping in alcohol use disorder. Am J Psychiatry 176:744–53. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18030357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litten RZ, Ryan ML, Falk DE et al. (2015) Heterogeneity of alcohol use disorder: Understanding mechanisms to advance personalized treatment. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 39:579–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowman C, Allen J, Stout RL et al. (1996) Replication and extension of Marlatt’s taxonomy of relapse precipitants: Overview of procedures and results. Addiction 91:51–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon D. (2012) Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis, New York, NY, USA: Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt AG. (1996) Taxonomy of high-risk situations for alcohol relapse: Evolution and development of a cognitive-behavioral model. Addiction 91:37–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, Goodman FR. (2019) Are substance use disorders emotional disorders? Why heterogeneity matters for treatment. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 26:e12286. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Tonigan JS, Longabaugh R. (1995) The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC). An Instrument for Assessing Adverse Consequences of Alcohol Abuse. Test Manual. MATCH Monograph Series, Rockville, Maryland: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. [Google Scholar]

- Molnar DS, Sadava SW, Decourville NH et al. (2010) Attachment, motivations, and alcohol: Testing a dual-path model of high-risk drinking and adverse consequences in transitional clinical and student samples. Can J Behav Sci 42:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, Muthén B. (2017) Mplus User’s Guide, 8th edn. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Robins L, Cottler L, Keating S. (1989) The NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule, Version III, Revised (DIS-III-R). Rockville, MD: National Institute on Mental Health. [Google Scholar]

- Roos CR, Bowen S, Witkiewitz K. (2017a) Baseline patterns of substance use disorder severity and depression and anxiety symptoms moderate the efficacy of mindfulness-based relapse prevention. J Consult Clin Psychol 85:1041–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos CR, Mann K, Witkiewitz K. (2017b) Reward and relief dimensions of temptation to drink: Construct validity and role in predicting differential benefit from acamprosate and naltrexone. Addict Biol 22:1528–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sliedrecht W, de Waart R, Witkiewitz K et al. (2019) Alcohol use disorder relapse factors: A systematic review. Psychiatry Res 278:97–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell LC, Sobell MB. (1992) Timeline Follow-Back. In Litten RZ & Allen JP (eds). Measuring Alcohol Consumption. Rockville, Maryland: Humana Press, 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Sydeman SJ. (1994) State-trait anxiety inventory and state-trait anger expression inventory. In Maruish ME (ed). The Use of Psychological Testing for Treatment Planning and Outcome Assessment, New York, NY, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., 292–321. [Google Scholar]

- Stasiewicz PR, Bradizza CM, Schlauch RC et al. (2013) Affect regulation training (ART) for alcohol use disorders: Development of a novel intervention for negative affect drinkers. J Subst Abuse Treat 45:433–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein ER, Votaw VR, Swan JE et al. (2021) Validity and measurement invariance of the Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment incentive salience domain among treatment-seekers with alcohol use disorder. J Subst Abuse Treat 122:108227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swan JE, Votaw VR, Stein ER et al. (2020) The role of affect in psychosocial treatments for substance use disorders. Curr Addict Rep 7:108–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Votaw VR, Pearson MR, Stein E et al. (2020) The Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment negative emotionality domain among treatment-seekers with alcohol use disorder: Construct validity and measurement invariance. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 44:679–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Votaw VR, Witkiewitz K. (2020) Motives for substance use in daily life: A systematic review of ecological momentary assessment studies. Clin Psychol Sci. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolitzky-Taylor K, Drazdowski TK, Niles A et al. (2018) Change in anxiety sensitivity and substance use coping motives as putative mediators of treatment efficacy among substance users. Behav Res Ther 107:34–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zywiak WH, Connors GJ, Maisto SA et al. (1996) Relapse research and the Reasons for Drinking Questionnaire: A factor analysis of Marlatt’s relapse taxonomy. Addiction 91:S121–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.