Abstract

Background

People living with chronic kidney disease (CKD) experience a range of symptoms and often have complex comorbidities. Many pharmacological interventions for people with CKD have known risks of adverse events. Acupuncture is widely used for symptom management in patients with chronic diseases and in other palliative care settings. However, the safety and efficacy of acupuncture for people with CKD remains largely unknown.

Objectives

We aimed to evaluate the benefits and harms of acupuncture, electro‐acupuncture, acupressure, moxibustion and other acupuncture‐related interventions (alone or combined with other acupuncture‐related interventions) for symptoms of CKD. In particular, we planned to compare acupuncture and related interventions with conventional medicine, active non‐pharmacological interventions, and routine care for symptoms of CKD.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Specialised Register up to 28 January 2016 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. We also searched Korean medical databases (including Korean Studies Information, DBPIA, Korea Institute of Science and Technology Information, Research Information Centre for Health Database, KoreaMed, the National Assembly Library) and Chinese databases (including the China Academic Journal).

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs that investigated the effects of acupuncture and related point‐stimulation interventions with or without needle penetration that involved six sessions or more in adults with CKD stage 3 to 5, regardless of the language and type of publication. We excluded studies that used herbal medicine or co‐interventions administered unequally among the study groups.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently extracted data and assessed risk of bias. We calculated the mean difference (MD) or standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for continuous outcomes and risk ratio (RR) for dichotomous outcomes. Primary outcomes were changes in pain and depression, and occurrence of serious of adverse events.

Main results

We included 24 studies that involved a total of 1787 participants. Studies reported on various types of acupuncture and related interventions including manual acupuncture and acupressure, ear acupressure, transcutaneous electrical acupuncture point stimulation, far‐infrared radiation on acupuncture points and indirect moxibustion. CKD stages included pre‐dialysis stage 3 or 4 and end‐stage kidney disease on either haemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis.

None of the included studies assessed pain outcomes, nor formally addressed occurrence of serious adverse events, although three studies reported three participant deaths and three hospitalisations as reasons for attrition. Three studies reported minor acupuncture‐related harms; the remainder did not report if those events occurred.

All studies were assessed at high or unclear risk of bias in terms of allocation concealment. Seventeen studies reported outcomes measured for only two months.

There was very low quality of evidence that compared with routine care, manual acupressure reduced scores of the Beck Depression Inventory score (scale from 0 to 63) (3 studies, 128 participants: MD ‐4.29, 95% CI ‐7.48 to ‐1.11, I2 = 0%), the revised Piper Fatigue Scale (scale from 0 to 10) (3 studies, 128 participants: MD ‐1.19, 95% CI ‐1.77 to ‐0.60, I2 = 0%), and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (scale from 0 to 21) (4 studies, 180 participants: MD ‐2.46, 95% CI ‐4.23 to ‐0.69, I2 = 50%).

We were unable to perform further meta‐analyses because of the paucity of data and problems with clinical heterogeneity, such as different interventions, comparisons and timing of outcome measurements.

Authors' conclusions

There was very low quality of evidence of the short‐term effects of manual acupressure as an adjuvant intervention for fatigue, depression, sleep disturbance and uraemic pruritus in patients undergoing regular haemodialysis. The paucity of evidence indicates that there is little evidence of the effects of other types of acupuncture for other outcomes, including pain, in patients with other stages of CKD. Overall high or unclear risk of bias distorts the validity of the reported benefit of acupuncture and makes the estimated effects uncertain. The incomplete reporting of acupuncture‐related harm does not permit us to assess the safety of acupuncture and related interventions. Future studies should investigate the effects and safety of acupuncture for pain and other common symptoms in patients with CKD and those undergoing dialysis.

Plain language summary

Acupuncture and related interventions for the symptoms of chronic kidney disease

Background

Patients with chronic kidney disease experience various physical and psychological symptoms, but treatment options are limited because of reduced kidney function and other chronic health problems. Acupuncture is widely used to treat common symptoms such as pain, fatigue or depressive mood in patients with chronic conditions. This review aimed to investigate the current evidence and potential role for acupuncture in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD).

Study characteristics

We searched the literature up to January 2016 and analysed 24 studies that involved 1787 participants. Of these, only seven studies provided data that could be combined for analysis. The studies reported that manual acupressure improved fatigue, depression and sleep disturbance when used as an adjunct to routine care for patients undergoing maintenance haemodialysis 4 weeks from baseline. No study assessed pain and most did not report whether adverse events of acupuncture occurred.

Key results

Overall, we found very low quality evidence about the effectiveness of acupuncture for symptoms of CKD. Manual acupressure combined with routine care may provide short‐term symptom relief from depressive mood, fatigue and sleep disturbance in patients undergoing haemodialysis. Findings from this review cannot support the benefits of other acupuncture techniques for patients with CKD because there were too few reliable studies. Pain is a common condition in patients with CKD. Thus, the potential role of acupuncture for pain control in patients with CKD deserves further research.

Clinicians should carefully monitor the safety of acupuncture in patients with CKD unless sound evidence supports the safety of these interventions for CKD patients.

Quality of the evidence

All studies were assessed at high or unclear risk of bias, especially in terms of selection of participants and selective outcome reporting, which made the validity of their results doubtful.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Manual acupressure compared with routine care for people undergoing haemodialysis.

| Manual acupressure compared with routine care for people undergoing haemodialysis | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with end‐stage kidney disease Settings: haemodialysis centre Intervention: manual acupressure | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Manual acupressure | |||||

|

Pain1 Not measured |

See comment | See comment | Not estimable1 | ‐ | See comment | |

|

Depression

Beck's Depression Inventory Scale from: 0 to 63 Follow‐up: 4 weeks |

The mean depression ranged across control groups from 14.9 to 21.61 points | The mean depression in the intervention groups was 4.29 lower (7.48 to 1.11 lower) | 128 (3) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4,5 | ||

|

Sleep quality

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index6 Scale from: 0 to 21 Follow‐up: 4 weeks |

The mean sleep quality ranged across control groups from 9.36 to 10.9 points | The mean sleep quality in the intervention groups was 2.46 lower (4.23 to 0.69 lower) | 180 (4) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low3,4,5,7 | ||

|

Fatigue

Revised Piper Fatigue Scale Scale from: 0 to 10 Follow‐up: mean 4 weeks |

The mean fatigue ranged across control groups from 4.7 to 5.71 points | The mean fatigue in the intervention groups was 1.19 lower (1.77 to 0.6 lower) | 128 (3) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,3,4,5 | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI) CI: Confidence interval | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

1 No study measured pain 2 All study had high or unclear risk of bias in domains of random sequence generation, concealment of allocation and blinding of participants and outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data and selective outcome reporting. Therefore, quality of evidence was downgraded by two levels due to the limitations in the design and implementation 3 Collectively, quality of evidence was downgraded by three levels due to the very serious limitation in the design and implementation and the indirectness of evidence 4 The study population was restricted to the patients undergoing regular haemodialysis. Therefore, quality of evidence was downgraded by one level due to the indirectness of evidence 5 The evidence was downgraded due to small sample size of a meta‐analysis 6 Global PSQI scores were used 7 All study had high or unclear risk of bias in domains of random sequence generation, concealment of allocation and blinding of participants, incomplete outcome data and selective outcome reporting. Therefore, quality of evidence was downgraded by two levels due to the limitations in the design and implementation

Background

Description of the condition

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is defined as the persistence of structural and/or functional abnormalities of the kidney for three or more months (NKF 2002). The prevalence of CKD is increasing, and it is acknowledged as major health issue worldwide (Imai 2008; James 2010). CKD symptoms include pain, itch (pruritus), peripheral numbness, sleep disturbances, depression, fatigue, sexual dysfunction, nausea and vomiting. Factors that contribute to these symptoms include anaemia, uraemic toxins, reduced renal capacity, chronic disease‐related inflammation, and psychological stress associated with long‐term illness. These symptoms have often been under‐treated or under‐recognised, which has contributed to an increased symptom burden and diminished quality of life among people with CKD (Abdel‐Kader 2009; Claxton 2010). Some symptoms, such as sleep disturbance and depression, lead to poor quality of life and are known to be associated with increased mortality in dialysis patients (Elder 2008; Lopes 2002; Mapes 2003). Given the overall negative impact of inappropriately treated symptoms, adequate symptom management should be an essential component for the optimal care of CKD patients (Rastogi 2008).

Current management strategies for CKD focus on controlling kidney disease, comorbidities and related symptoms. According to patients' accounts, some components of care are poorly integrated into management plans (Tong 2009). Interventions for symptom management and supportive care have often had poor levels of patient compliance. Some patients living with long‐term illness report having experienced detrimental effects from the need for therapeutic polypharmacy and a fear of drug‐related adverse events (Browne 2010; Davison 2007). Reduced renal capacity and altered pharmacokinetics in CKD patients are significant barriers to the extrapolation of the pharmacological symptom management methods used in non‐CKD populations (Verbeeck 2009). These barriers often result in insufficient symptom management and decreased quality of life among CKD patients.

Description of the intervention

Acupuncture is a complex intervention that originated from East Asian countries (MacPherson 2008). 'Acupuncture' refers to either a specific procedure involving acupuncture needling on body points or a multi‐component treatment that also involves taking patients' history, physical examination, diagnosis, and patient education based on East Asian medicine (Langevin 2011). Acupuncture has been used for pain management, supportive cancer care and other chronic illnesses to improve symptoms, quality of life and patient‐perceived well‐being (Dean‐Clower 2010; Frisk 2012; McKee 2013; Simcock 2013; Suzuki 2012). Although the frequency of acupuncture use in the general population varies, up to 82% of adults reportedly have a cumulative lifetime experience with acupuncture. The wide range may be attributable to regional, cultural and research methodology differences (Hunt 2010; KHIDI 2008; Naoto 2005). Published information about the use of acupuncture for people with CKD is sparse, but a survey of 232 Japanese haemodialysis patients revealed that approximately 30% had previously experienced acupuncture, and 35% were receptive to acupuncture for symptom management (Sakuraba 2007). Nowack 2009 investigated 180 patients with ESKD at five nephrology centres in southern Germany and found that 57% of dialysis patients and 49% of transplant patients were regular users of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) modalities (but not acupuncture). This finding suggests a potentially high level of acupuncture and other CAM modalities use among people with end‐stage kidney disease (ESKD).

Although results from acupuncture studies are inconsistent, limited evidence of acupuncture benefits is included in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews including systematic reviews of acupuncture for peripheral joint osteoarthritis (Manheimer 2010), low back pain (Furlan 2005), chemotherapy‐induced nausea and vomiting (Ezzo 2006), prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting (Lee 2015), tension‐type headache (Linde 2009a) and migraine prophylaxis (Linde 2009b). An individual patient data meta‐analysis of acupuncture for chronic musculoskeletal pain suggested that acupuncture offered modest but significant effects compared with sham acupuncture (Vickers 2012). The results of these studies may merit considering extrapolation of such evidence to CKD and ESKD populations. The current use of acupuncture for pain, depression and other chronic conditions, which are also prevalent in people with CKD, may support a need for research in the use of acupuncture in those populations.

How the intervention might work

Garcia 2005 suggested that the possible mechanism of acupuncture‐like stimulation in CKD was associated with cholinergic anti‐inflammatory effects via parasympathetic nerve stimulation in the renal inflammation model. This effect has been proposed as a plausible concept for a number of chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases (Kavoussi 2007). Because chronic inflammation is prevalent, and associated with increased mortality in both non‐dialysis and dialysis CKD patients (Bergström 2000; Carrero 2008), acupuncture may help to improve medical outcomes (Carrero 2008). Other well‐known segmental and extra‐segmental analgesic effects, central regulation of endogenous opioids and serotonin might modulate symptoms and complications among CKD patients including pain, itch, and sleep disturbances (White 2008). These hypotheses require further research.

Why it is important to do this review

Previous narrative reviews have suggested acupuncture as a promising intervention for patients with CKD or ESKD (Garcia 2005; Markell 2005). We have previously conducted two systematic reviews and found that there was no evidence to inform definitive conclusions about the benefits or harms of acupuncture and acupressure for renal itch (Kim 2010a) and symptom management among people with ESKD (Kim 2010b) because of the poor methodological quality of the included studies and paucity of RCTs. Comprehensive evidence of acupuncture and related interventions for symptom management in patients with all stages of CKD remains lacking. This review aimed to systematically synthesise and critically assess the current evidence for acupuncture and related interventions for control of CKD symptoms.

Objectives

We aimed to evaluate the benefits and harms of acupuncture, electroacupuncture, acupressure, moxibustion and other acupuncture‐related interventions (alone or combined with other acupuncture‐related interventions) for symptoms of CKD. In particular, we planned to compare acupuncture and related interventions with conventional medicine, active non‐pharmacological interventions, and routine care for symptoms of CKD.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐RCTs (RCTs in which allocation to treatment was obtained by alternation, use of alternate medical records, date of birth or other predictable methods) that tested the effects of acupuncture and related interventions (hereafter, acupuncture interventions) for patients with CKD regardless of language or type of publication. Only data from the first phase of cross‐over studies were used to avoid any possible carry over effect. We excluded non‐randomised and uncontrolled studies.

Types of participants

We included adults (aged 18 years and over or as defined by authors) with CKD stage 3 to 5 or 5D, as defined by the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) guidelines (NKF 2002).

Kidney damage for at least three months defined as structural or functional abnormalities of the kidney with or without decreased GFR and manifested by either pathological abnormalities or markers of kidney disease, including abnormalities in the composition of the blood or urine or abnormalities in imaging tests.

GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 for at least three months with or without kidney disease.

CKD stages

Stage 3: GFR 30 to 59 mL/min/1.73 m2

Stage 4: GFR 15 to 29 mL/min/1.73 m2

Stage 5: GFR < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2

Stage 5D: on dialysis.

We applied KDOQI criteria to define and classify CKD wherever possible. Nevertheless, we also included studies of patients with CKD defined using methods other than KDOQI because they may have been conducted in countries that do not apply the KDOQI definition (Markell 2006).

We excluded studies that involved kidney transplant recipients or patients with acute kidney injury and studies of children. We also excluded studies that lacked sufficient information to determine CKD stage (either from published reports or by contacting the authors).

Types of interventions

Included interventions

-

Acupuncture stimulates specific points with or without needle penetration to elicit a therapeutic response. We included the following forms of acupuncture using different stimulation methods.

Electrostimulation using a penetrating needle or non‐penetrating pad, laser, manual acupressure or acupressure with other devices

Moxibustion (heating the herb mugwort)

Other types of heat stimulation on acupuncture points.

Studies investigating combinations of acupuncture interventions because practitioners often use these to achieve prolonged or synergistic effects.

Comparisons of sham interventions (e.g. non‐penetrating or penetrating sham acupuncture, sham laser, sham moxibustion, sham electrostimulation, sham acupressure), as well as comparisons of routine care (e.g. treatments provided by nephrologists or physicians for CKD management) and other active comparators (e.g. exercise).

Ezzo 2000 reported that six or more sessions of acupuncture treatment were more effective than fewer sessions in patients with chronic pain. In real clinical situations, practitioners do not expect that fewer than six sessions is sufficient to manage chronic disease. Therefore, we planned to exclude studies involving fewer than six sessions of acupuncture treatments.

We excluded studies that did not provide co‐interventions equally to all randomised arms.

Excluded interventions

Acupuncture‐point injection because of the difficulty of controlling the source of any reported effect; and

Studies that compared different types of acupuncture, herbs, or other complementary medicine interventions.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

We selected two representative symptoms for primary outcomes based on the high prevalence and clinical impacts for people with CKD (Davison 2007; Finkelstein 2008; Pham 2010). The occurrence of serious adverse events was also a primary outcome for analysing harms.

Change in pain (e.g. bone and joint pain, neuropathic pain, headache or other types of bodily pain perceived by patients) measured as a dichotomous outcome (e.g. improvement: yes or no) or on a self‐rating scale such as the visual analogue scale (VAS), a numerical rating scale or other questionnaire scores

-

Change in depression symptomatology measured as a dichotomous outcome (e.g. improvement: yes or no), on a self‐rating scale such as the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck 1961), or on a clinician‐rated scale such as the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Hamilton 1960).

Beck Depression Inventory: minimal depression (0‐13); mild depression (14‐19); moderate depression (20‐28); severe depression (29‐63)

Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression: normal (0‐7); mild depression (8‐13); moderate depression (14‐18); severe depression (18‐22); very severe depression (≥ 23)

The occurrence of serious adverse events, including hospitalisation, surgery other than scheduled transplantation, and death.

A subjective, non‐validated assessment tool may be a source of bias. If the same outcome was reported using multiple methods, we gave preference to validated scales.

Secondary outcomes

Changes in symptoms other than those addressed in the primary outcome measurements (e.g. fatigue, sleep disturbance, nausea/vomiting, xerostomia, restless legs syndrome) measured as a dichotomous (e.g. improvement: yes or no) or continuous (e.g. VAS or other questionnaire score) outcome

Changes in quality of life (e.g. general quality of life as measured by the Medical Outcome Study item short‐form health survey (SF‐36) and health‐related or disease‐specific quality of life (e.g. assessed by the KDQOL questionnaire)

Changes in biological or physiological parameters (e.g. blood pressure, glycaemic control, serum albumin, serum creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, calcium, phosphate, parathyroid hormone)

Changes in the occurrence of intradialytic complications (e.g. events of symptomatic intradialytic hypotension, cramps, nausea and any untoward symptoms that occurred during dialysis)

Changes in medication (e.g. analgesics, sleep medication, antiemetics or other medication) for symptom management

The occurrence of adverse events of acupuncture (any reported events during or after acupuncture such as infection, bruising or bleeding at needling sites).

We did not consider the cost of acupuncture to be an outcome.

We expected that the time course for reporting outcomes would vary among studies and grouped outcomes into four time periods (Linde 2009b).

Up to eight weeks (two months) after the start of the treatment

Three or four months after the start of the treatment

Five to six months after the start of the treatment

More than six months after the start of the treatment.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Specialised Register up to 28 January 2016 through contact with the Information Specialist using search terms relevant to this review. The Cochrane Kidney and Transplant Specialised Register contains studies identified from several sources.

Monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

Weekly searches of MEDLINE OVID SP

Handsearching of kidney‐related journals and the proceedings of major kidney conferences

Searching of the current year of EMBASE OVID SP

Weekly current awareness alerts for selected kidney and transplant journals

Searches of the International Clinical Trials Register (ICTRP) Search Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov.

Studies contained in the Specialised Register are identified through search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE based on the scope of Cochrane Kidney and Transplant. Details of these strategies, as well as a list of handsearched journals, conference proceedings and current awareness alerts, are available in the Specialised Register section of information about Cochrane Kidney and Transplant.

See Appendix 1 for the search terms used in the strategies for this review.

Searching other resources

Reference lists of review articles, relevant studies and clinical practice guidelines.

Letters to investigators known to be involved in previous studies seeking information about unpublished or incomplete studies.

Searches of Korean academic portal databases (i.e. NANET, RISS4U, KISS, DBpia, KMbase, KoreaMed, KISTI, NDSL, OASIS, Dlibrary, KoreanTK, and RICHIS), and Chinese databases (including the China Academic Journal) (see Appendix 2 for the search terms for Korean databases and handsearched Korean journals).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The search strategy described was used to obtain titles and abstracts of studies that may be relevant to the review. Titles and abstracts were screened independently by two authors, who discarded studies that were not applicable; however studies and reviews that might include relevant data or information on studies was retained initially. Two authors independently assess retrieved abstracts, and if necessary the full text, to determine which satisfied inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and management

Data extraction was carried out independently by pairs of authors using standard data extraction forms. Studies reported in non‐English, Korean or Chinese language journals were translated before assessment. Where more than one publication of one study existed, reports were grouped together and the publication with the most complete data was used in the analyses. Where relevant outcomes were only published in earlier versions these data were used. Any discrepancies between published versions were to be highlighted.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The following items were independently assessed by two authors using the risk of bias assessment tool (Higgins 2011) (see Appendix 3).

Was there adequate sequence generation (selection bias)?

Was allocation adequately concealed (selection bias)?

-

Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study?

Participants and personnel (performance bias)

Outcome assessors (detection bias)

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed (attrition bias)?

Are reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting (reporting bias)?

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a risk of bias?

We rated risk of bias for participant blinding as low only when results of sham‐credibility tests showed successful participant blinding in the study. We rated risk of bias for selective outcome reporting as low only when the study protocol was available to ensure that all planned and measured outcomes were reported.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous outcomes (e.g. improved, not improved), we presented results as risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). When data were continuous (e.g. VAS, blood pressure, biochemical parameters), we used mean difference (MD) and 95% CI and the standardised mean difference (SMD).

Unit of analysis issues

For multi‐intervention groups, we aimed to combine groups into a single pair‐wise comparison where appropriate. Where studies had multiple observations for outcome variables, we grouped and then meta‐analysed according to four time periods (within two months; three to four months; five to six months; more than six months after the start of the treatment) and conducted meta‐analyses for each group of studies. If there were more than two outcome measurements in one time period, we used the time point that was measured last. We planned to assess first phase data from cross‐over studies. Where appropriate, we combined results from cross‐over studies with parallel group studies.

Dealing with missing data

We sent emails to the contact detail listed in the study to obtain incompletely reported information.

Further information required from study authors was requested by written correspondence and any relevant information obtained was to be included in the review. Evaluation of important numerical data such as screened, randomised patients as well as intention‐to‐treat, as‐treated and per‐protocol population was carefully performed. Attrition rates, for example drop‐outs, losses to follow‐up and withdrawals were investigated. We did not impute missing data for effect estimates.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was analysed using a Chi2 test on N‐1 degrees of freedom, with an alpha of 0.05 used for statistical significance and with the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). I2 values of 25%, 50% and 75% correspond to low, medium and high levels of heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to use funnel plots for analysing publication bias (Higgins 2011) wherever possible. There were insufficient studies per comparison to do this.

Data synthesis

Data were pooled using the random‐effects model but the fixed‐effect model was also used to ensure robustness of the model chosen and susceptibility to outliers.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to perform subgroup analyses for each type of acupuncture (electrical or manual acupuncture, laser acupuncture, acupressure, moxibustion, other types of heat stimulation on acupuncture points and combinations of acupuncture‐related interventions) to identify differences in treatment effects between subgroups. We planned to conduct subgroup analysis for disease status (pre‐dialysis status in CKD stage 3 to 4 and ESKD regardless of whether patients were undergoing dialysis) to assess if treatment effects varied among subgroups. We also planned to conduct subgroup analysis by type of control (sham intervention, conventional medicine, routine care or other active non‐pharmacological intervention). Adverse effects were to be tabulated and assessed using descriptive techniques, because they were likely to differ for various interventions. Where possible, the risk difference with 95% CI was to be calculated for each adverse effect, either compared with no treatment or another agent.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analysis to identify the influence of methodological quality on effect estimates by excluding studies with inadequate or unclear random sequence generation, concealment of allocation and participant and assessor blinding. We also planned to conduct sensitivity analysis to assess the influence of CKD definition and classification (KDOQI criteria: yes or no) and the use of validated versus non‐validated scales on the results of our review. There were insufficient studies per comparison to undertake these sensitivity analyses.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

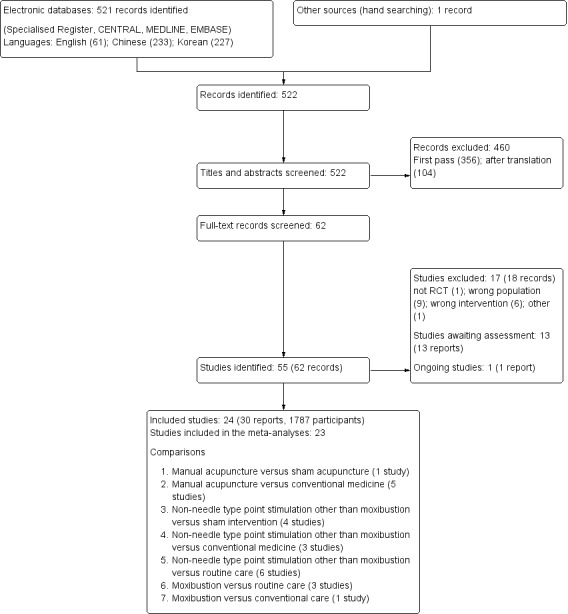

We searched English, Chinese and Korean language databases and identified 522 records. After title and abstract review 356 records were excluded and an additional 104 were excluded after translation. We screened the remaining records and identified 24 studies (30 reports) that involved a total of 1787 participants for inclusion (Figure 1).

1.

Study selection flow diagram.

Prior to publication a search of the Specialised Register (28 January 2016) identified an additional 13 potential studies (Abbasi 2015; Chen 2012a; Eglence 2013; Feng 2012; Hmwe 2015; Och 2000; Ono 2015; Sabouhi 2013; Wang 2014c; Wu 2014a; Yan 2015; Zhu 2006; Zou 2015) and one ongoing study (NCT02432508). These will be assessed in a future update of this review.

Included studies

Availability of additional information from authors

We emailed the study authors of all included studies to obtain further information because of the incomplete reporting. Three authors associated with six studies provided additional information (Che‐Yi 2005; Tsay 2003a; Tsay 2004a; Tsay 2004b; Qiu 2012; Sun 2012). For the other studies, we could not obtain additional information because there was no contact information in the study (12); the contact information was inactive (12); or there was no response to our e‐mail queries (3).

Design

We included 19 RCTs and five quasi‐RCTs (Cho 2004; Ma 2004; Rui 2002; Song 2007; Cui 2012). All included studies employed a parallel design with relatively small sample sizes (median 69; range 40 to 152). The studies were conducted in China (15), Taiwan (7), Iran (1) and Poland (1) and were published in English (12) and Chinese (12). Most of the studies enrolled participants in haemodialysis centres or community hospitals (22).

Participants

Mean ages were over 50 years (20 studies) or between 40 and 50 years (four studies). Twenty‐two studies included participants with ESKD. Two studies did not provide information on the CKD stage (Ma 2004; Song 2007). After determination of the CKD stages based on the mean serum creatinine values provided in the studies, we considered them as studies of participants of ESKD. Four studies employed K/DOQI or KDIGO guidelines for diagnosing CKD (Dai 2007a; Qiu 2012; Song 2007; Xie 2012).

In 21/22 studies involving participants with ESKD, haemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis was provided as a renal replacement therapy. One study did not specify whether the participants were undergoing any renal replacement therapy (Dai 2007a). In these studies, the haemodialysis frequency was three times/week (12 studies), two to three times/week (3), twice/week (1), twice/week or three times within two weeks (1). Three studies did not report the haemodialysis frequency (Gao 2002; Tsay 2004a; Tsay 2004b). Peritoneal dialysis frequency was four times/day in Zhao 1995; and Jedras 2003 did not report dialysis frequency.

Ten studies reported haemodialysis times of four hours (4), four to five hours (1), three to five hours (2), 3.5 to 4.5 hours (1) and 2.5 to 5.0 hours (1) per session and 15 hours a week (1). In the 14 studies that solely or partially included haemodialysis patients, only three reported baseline values of Kt/V over 1.2, representing adherence to K/DOQI guidelines for dialysis adequacy (Che‐Yi 2005; Tsay 2004a; Qiu 2012).

Further details are presented in Characteristics of included studies.

Types of interventions

Treatment interventions included manual (finger) acupressure (Cho 2004; Dai 2007a; Jedras 2003; Shariati 2012; Tsay 2003a; Tsay 2004a; Tsay 2004b), ear acupressure (Xie 2012; Zhao 2011), manual acupuncture (Che‐Yi 2005; Cui 2012; Gao 2002; Ma 2004; Rui 2002; Zhang 2011d), indirect moxibustion (Cheng 2012; Qiu 2012; Sun 2008a; Sun 2012; Zhao 1995), far infrared radiation (Hsu 2009; Lin 2011; Su 2009), adjunctive manual acupuncture plus conventional medication (Song 2007), and transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation (Tsay 2004b).

Interventions in the control groups varied, including routine care (12 studies) (Cheng 2012; Cho 2004; Lin 2011; Qiu 2012; Shariati 2012; Sun 2008a; Sun 2012; Tsay 2003a; Tsay 2004a; Tsay 2004b; Xie 2012; Zhao 1995), conventional medication (7) (Cui 2012; Dai 2007a; Gao 2002; Ma 2004; Rui 2002; Song 2007; Zhao 2011), sham interventions (5) (Che‐Yi 2005; Hsu 2009; Su 2009; Tsay 2003a; Tsay 2004a), haemodiafiltration (Zhang 2011d) and an unspecified control intervention (Jedras 2003).

Five of 12 studies that employed routine care as a comparison intervention provided detailed information on routine care, including blood pressure and glucose control, anaemia correction, electrolyte control and tailored dietary modifications of salt and protein (Che‐Yi 2005; Cheng 2012; Qiu 2012; Sun 2008a; Sun 2012). In five studies comparing real and sham interventions, the actual techniques of the sham intervention varied (Che‐Yi 2005; Hsu 2009; Su 2009; Tsay 2003a; Tsay 2004a). One study compared manual acupuncture with penetrating acupuncture on non‐acupuncture points (Che‐Yi 2005), and two other studies compared manual acupressure with sham acupressure on non‐acupuncture points (Tsay 2003a, Tsay 2004a). Two studies compared far infrared radiation with plain adhesive tape (Hsu 2009) or heat pad therapy (Su 2009) on the same acupuncture points that were used in the treatment intervention. These types of interventions did not appear to be identical to real treatments. After discussion between the review authors, however, we concluded that the interventions were different types of sham intervention.

Treatment lengths varied from 10 days (Ma 2004) to 24 weeks (Song 2007) (median seven weeks). In most studies, the total number of treatment sessions varied between 8 and 36. However, one study conducted acupuncture for at least 100 sessions over a 24‐week period (Song 2007).

Appendix 4 presents further summarised details of the acupuncture interventions and Appendix 5 presents Standards for Reporting Interventions in Clinical Trials of Acupuncture (STRICTA) (www.stricta.info/) information of acupuncture interventions and comparators including sham interventions.

Outcome measures

Nine studies included at least one validated outcome (Cho 2004; Lin 2011; Qiu 2012; Shariati 2012; Su 2009; Sun 2008a; Tsay 2003a; Tsay 2004a; Tsay 2004b). The follow‐up period varied between four to 24 weeks from randomisation, although most studies reported short‐term outcomes within two months.

None of the included studies measured pain. Three studies assessed depression using Beck’s depression inventory (Cho 2004; Tsay 2004a; Tsay 2004b). Other subjective symptoms assessed in the included studies were uraemic pruritus (Che‐Yi 2005; Gao 2002; Hsu 2009; Jedras 2003; Rui 2002; Zhang 2011d), sleep quality (Dai 2007a; Tsay 2003a; Tsay 2004a; Tsay 2004b; Shariati 2012; Zhao 2011), fatigue (Cho 2004; Lin 2011; Tsay 2004a; Tsay 2004b), gastrointestinal discomfort (Cheng 2012; Cui 2012), xerostomia (Xie 2012), and symptoms related to malnutrition (Qiu 2012; Sun 2012). Three studies measured mixed symptoms as defined by traditional Chinese medicine theory (Ma 2004; Qiu 2012; Zhao 1995). One study reported a reduction of concomitant symptoms, including headache, dizziness, cognitive dysfunction, and palpitation (Dai 2007a). Four studies measured quality of life (Qiu 2012; Su 2009; Sun 2008a; Tsay 2003a).

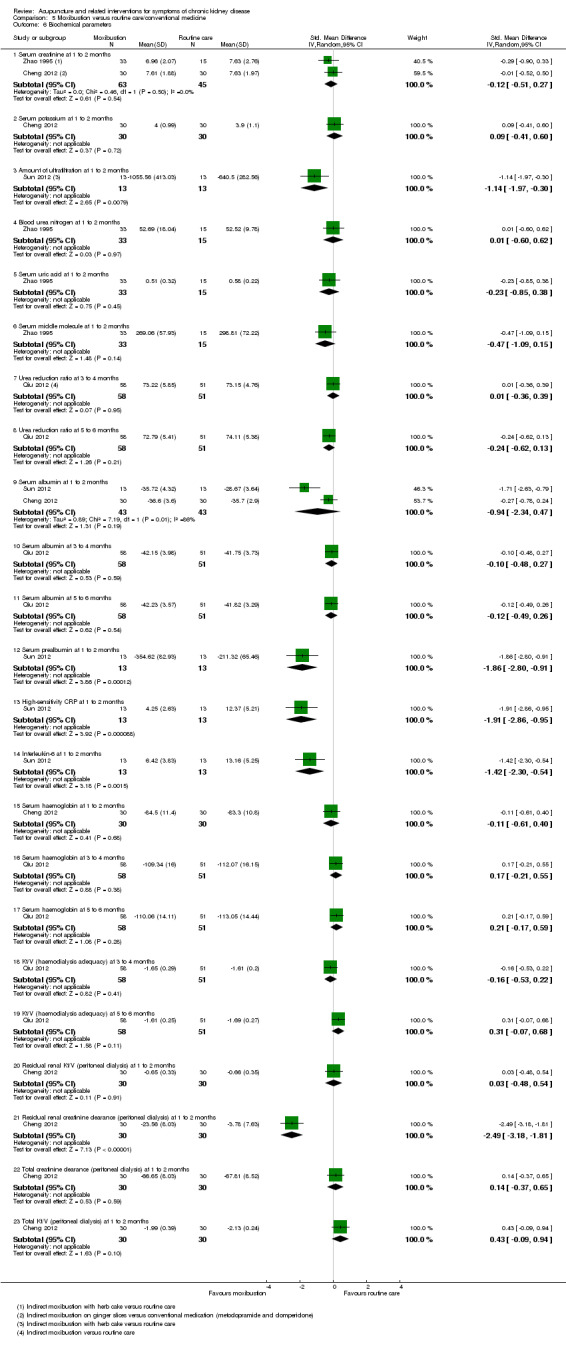

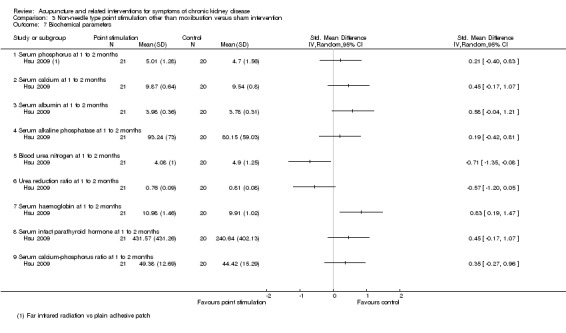

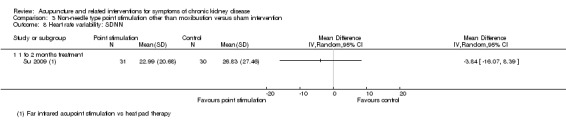

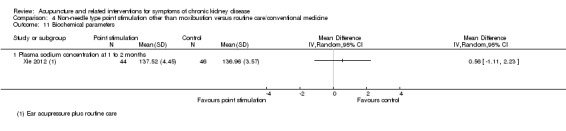

Ten studies assessed various biochemical or physiological parameters, including blood pressure, blood and urine profile and muscle strength (Cheng 2012; Hsu 2009; Ma 2004; Qiu 2012; Song 2007; Su 2009; Sun 2012; Xie 2012; Zhang 2011d; Zhao 1995). No included study measured the occurrence of intradialytic complications or changes in medication.

Excluded studies

We excluded 18 studies. Reasons for exclusion were: use of acupuncture point injection as a treatment intervention; wrong population (no CKD patients); inclusion of kidney transplant recipients; and providing fewer than six treatment sessions. See Characteristics of excluded studies.

Risk of bias in included studies

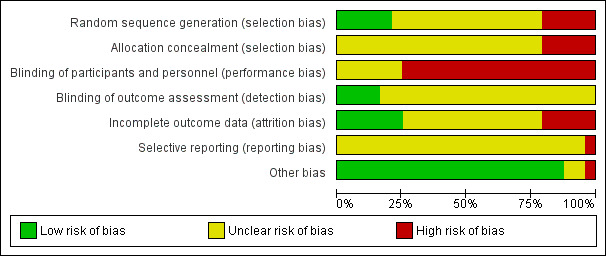

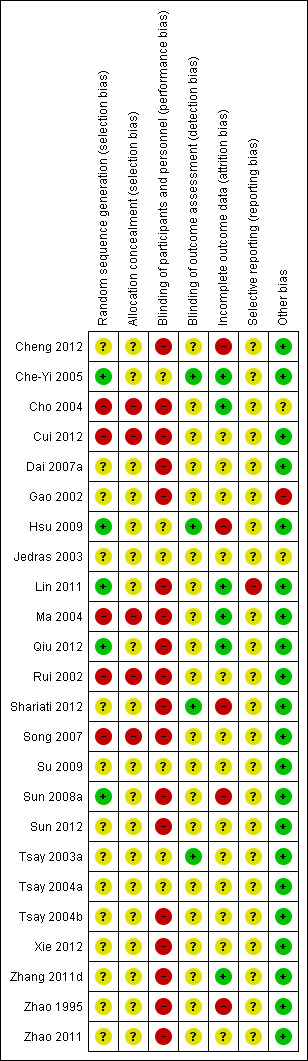

All included studies were assessed at high or unclear risk of bias for all domains. See Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

All included studies were described as randomised, however 14 studies lacked details on randomisation methods. Five studies used adequate random sequence generation methods, including computer random number generators (Che‐Yi 2005; Lin 2011) and random number tables (Hsu 2009; Sun 2008a; Qiu 2012). Five quasi‐RCTs used inadequate allocation methods, including sequences generated by even or odd days of haemodialysis treatment (Cho 2004) or sequences generated by hospital record number (Ma 2004; Rui 2002; Song 2007; Cui 2012).

Allocation concealment

Allocation concealment was not reported by any of the included studies. In the case of the five quasi‐RCTs, we considered these to be at high risk of bias because such studies were unlikely to conceal the allocation procedure properly. Hsu 2009 reported that they contained the randomisation list in serially numbered envelopes, although they did not report whether those envelopes were opaque‐sealed. Two study authors replied to our email queries; they confused blinding processes with allocation concealment (Che‐Yi 2005; Qiu 2012). We rated all included studies other than the five quasi‐RCTs as having unclear risk of bias.

Blinding

Performance bias

For studies in which acupuncture interventions were compared with active comparators, we rated the risk of bias as high. All five sham‐controlled studies attempted patient blinding, although there was no information on its success (Che‐Yi 2005; Hsu 2009; Su 2009; Tsay 2003a; Tsay 2004a). In two studies, the sham techniques (plain adhesive tapes or heat pad therapy on the same stimulation points) were apparently not identical in shape to the treatment interventions (i.e. far infrared irradiation) (Hsu 2009; Su 2009). For one study with an unspecified control intervention, we assessed the risk of bias as unclear (Jedras 2003).

Detection bias

Because the majority of the included studies used subjective outcome assessments, we regarded the blinding of outcome assessors as the key indicator of detection bias in each study. Only four studies blinded outcome assessors and these were assessed as being at low risk of bias (Che‐Yi 2005; Hsu 2009; Tsay 2003a; Shariati 2012). The remaining studies lacked information on whether the outcome assessors were blinded and the risk of bias was judged to be unclear.

Incomplete outcome data

We rated the five studies that analysed all randomised patients as being at low risk of bias (Che‐Yi 2005; Lin 2011; Ma 2004; Qiu 2012; Zhang 2011d). In Cho 2004, the small number of drop‐outs and clear reporting of reasons of withdrawals that seemed unlikely to affect the overall study results, we rated it as having low risk of bias. We judged five studies as being at high risk of bias. Three only analysed patients who had completed the study despite the occurrence of serious adverse events as being at high risk of bias (Hsu 2009; Shariati 2012; Sun 2008a), and in two studies the total number of assessed patients erroneously exceeded the total number of included patients in each group (Cheng 2012; Zhao 1995). Su 2009 only analysed patients who had completed the study. However, we rated the study as having unclear risk of bias due to unclear reasons for withdrawal. The remaining 12 studies had unclear risk of bias because of incomplete reporting of the number of participants at the study stages of outcome measurements and incomplete reporting of reasons for attrition.

Selective reporting

The study protocol was not accessible for any of the included studies. The risk of bias was unclear in all but one study. Lin 2011 lacked any reporting of the biochemical outcomes that were measured as was judged to be at high risk of bias.

Other potential sources of bias

We rated other source of bias as high in one study (Gao 2002) because there were risk of Hawthorne effect due to longer treatment duration in the acupuncture group. Two studies were rated as being at unclear risk of bias due to insufficient information to permit judgement (Cho 2004; Jedras 2003). All other studies were judged to be at low risk of bias.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Primary outcomes

Pain

None of the included studies measured pain.

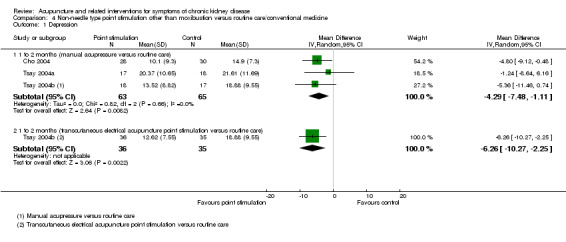

Depression

Manual acupressure significantly reduced depression symptoms compared with routine care after 4 weeks of treatment on the Beck Depression Inventory (Analysis 4.1.1 (3 studies, 128 participants): MD ‐4.29, 95% CI ‐7.48 to ‐1.11; I2 = 0%) (Cho 2004; Tsay 2004a; Tsay 2004b).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Non‐needle type point stimulation other than moxibustion versus routine care/conventional medicine, Outcome 1 Depression.

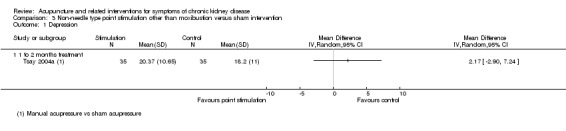

Tsay 2004b compared transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation with routine care and reported a significant reduction in depression symptoms on the Beck Depression Inventory (Analysis 4.1.2 (71 participants): MD ‐6.26, 95% CI ‐10.27 to ‐2.25).

In contrast, Tsay 2004a reported manual acupressure was not superior to sham acupressure on the Beck Depression Inventory (Analysis 3.1.1 (70 participants): MD 2.17, 95% CI ‐2.90 to 7.24).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Non‐needle type point stimulation other than moxibustion versus sham intervention, Outcome 1 Depression.

Serious adverse events

No study formally addressed the occurrence of serious adverse events as an outcome. Death (Hsu 2009; Shariati 2012; Sun 2008a), hospitalisation (Hsu 2009; Tsay 2003a) and transfer to an intensive care unit (Shariati 2012) were reported as reasons for attrition with no further information provided.

Secondary outcomes

Uraemic pruritus

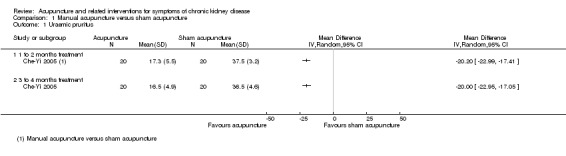

On a scale of 0 to 45, Che‐Yi 2005 reported manual acupuncture significantly improved refractory uraemic pruritus compared to sham acupuncture in haemodialysis patients at both four weeks (Analysis 1.1.1 (1 study, 40 participants): MD ‐20.20, 95% CI ‐22.99 to ‐17.41) and 16 weeks (Analysis 1.1.2 (40 participants): MD ‐20.00, 95% CI ‐22.95 to ‐17.05).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Manual acupuncture versus sham acupuncture, Outcome 1 Uraemic pruritus.

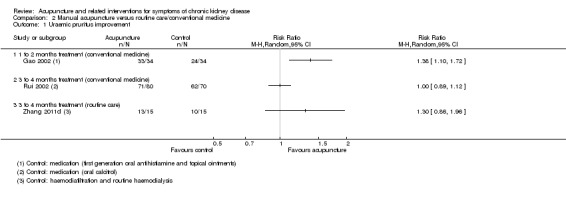

Gao 2002 reported manual acupuncture was superior to first‐generation oral antihistamine and topical ointments for uraemic pruritus at four to five weeks (Analysis 2.1.1 (68 participants); RR 1.38, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.72), whereas Rui 2002 reported the effects were similar to those administered oral calcitriol 2 μg at 16 weeks (Analysis 2.2.2 (150 participants): RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.12).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Manual acupuncture versus routine care/conventional medicine, Outcome 1 Uraemic pruritus improvement.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Manual acupuncture versus routine care/conventional medicine, Outcome 2 Gastrointestinal symptoms.

Zhang 2011d reported that when manual acupuncture was combined with one session of haemodiafiltration per week accompanied by routine haemodialysis, there was a non‐significant improvement in uraemic pruritus when compared to compared with the same dialysis intervention alone at 12 weeks (Analysis 2.1.3 (30 participants): RR 1.30, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.96).

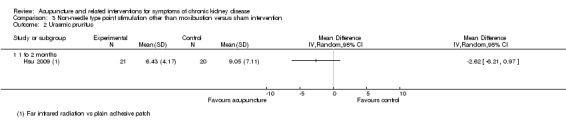

On a scale of 0 to 52, Hsu 2009 reported the effects of far‐infrared radiation on point SP6 were not significantly different from those of sham intervention (plain adhesive tape on the same acupoints) at eight weeks (Analysis 3.2.1 (41 participants): MD ‐2.62, 95% CI ‐6.21 to 0.97).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Non‐needle type point stimulation other than moxibustion versus sham intervention, Outcome 2 Uraemic pruritus.

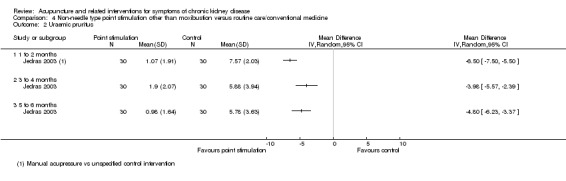

On a scale of 0 to 13.5, Jedras 2003 reported manual acupressure compared to an unspecified control significantly improved uraemic pruritus at six weeks (Analysis 4.2.1 (60 participants): MD ‐6.50, 95% CI ‐7.50 to ‐5.50), 12 weeks (Analysis 4.2.2 (60 participants): MD ‐3.98, 95% CI ‐5.57 to ‐2.39), and 18 weeks (Analysis 4.2.3 (60 participants): MD ‐4.80, 95% CI ‐6.23 to ‐3.37).

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Non‐needle type point stimulation other than moxibustion versus routine care/conventional medicine, Outcome 2 Uraemic pruritus.

Fatigue

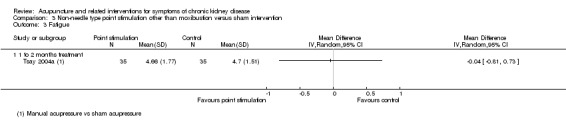

Tsay 2004a reported no significant difference in fatigue between manual acupressure and sham acupressure at four weeks using a revised PDF scale of 0 to 10 (Analysis 3.3.1 (70 participants): MD ‐0.04, 95% CI ‐0.81 to 0.73).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Non‐needle type point stimulation other than moxibustion versus sham intervention, Outcome 3 Fatigue.

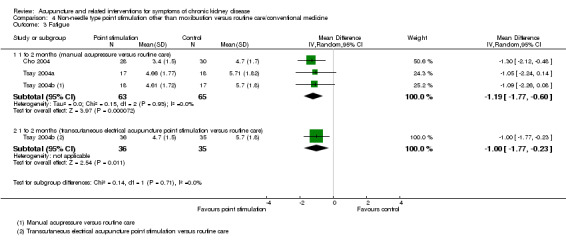

Manual acupressure significantly reduced fatigue in compared with routine care at four weeks (Analysis 4.3.1 (3 studies, 128 participants): MD ‐1.19, 95% CI ‐1.77 to ‐0.60; I2 = 0%). Tsay 2004b reported a significant reduction in fatigue with transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation when compared to routine care (Analysis 4.3.2 (71 participants): MD ‐1.00, 95% CI ‐1.77 to ‐0.23).

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Non‐needle type point stimulation other than moxibustion versus routine care/conventional medicine, Outcome 3 Fatigue.

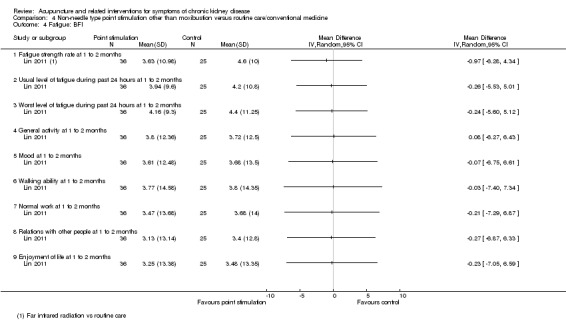

Lin 2011 compared far infrared radiation with routine care and found no significant differences at eight weeks in any of the nine sub‐domain scores on the Brief Fatigue Inventory (Analysis 4.4).

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Non‐needle type point stimulation other than moxibustion versus routine care/conventional medicine, Outcome 4 Fatigue: BFI.

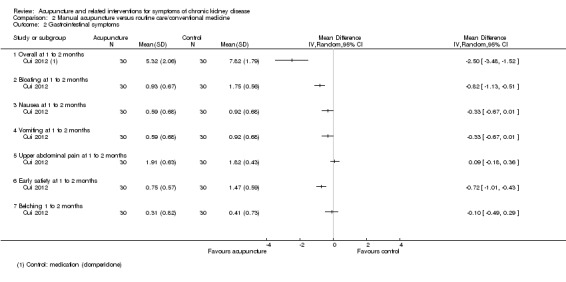

Gastrointestinal symptoms

On a scale of 0 to 18, Cui 2012 reported significant improvement for manual acupuncture compared with domperidone on overall symptom scores at two weeks (Analysis 2.2.1 (60 participants): MD ‐2.50, 95% CI ‐3.48 to ‐1.52). For the subscale scores (0 to 3) there were significant improvements for bloating (Analysis 2.2.2 (60 participants): MD ‐0.82, 95% CI ‐1.13 to ‐0.51) and early satiety (Analysis 2.2.6 (60 participants): MD ‐0.72, 95% CI ‐1.01 to ‐0.43), but not for nausea, vomiting, upper abdominal pain and belching at two weeks.

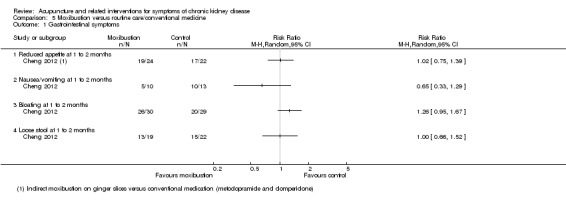

Cheng 2012 reported moxibustion was not significantly different to routine care in terms of reduced appetite, nausea/vomiting, bloating, or loose stools after 10 days of treatment (Analysis 5.1).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Moxibustion versus routine care/conventional medicine, Outcome 1 Gastrointestinal symptoms.

Hypertension

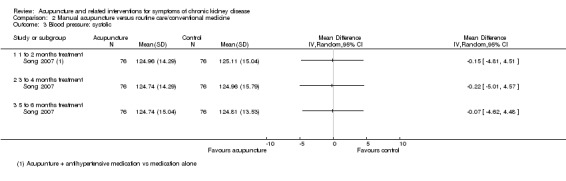

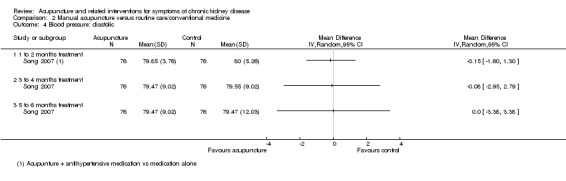

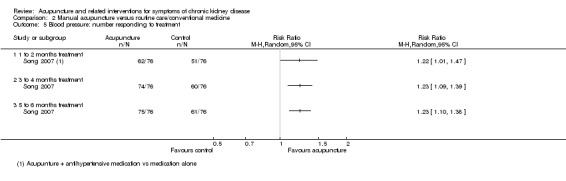

Song 2007 compared manual acupuncture plus antihypertensive medication (oral irbesartan 150 mg/d and fosinopril 10 mg/d for 24 weeks) versus antihypertensive medication alone for the management of hypertension. No significant differences were found in either average systolic or diastolic pressure at any of the analysed time points (8, 12 and 24 weeks) (Analysis 2.3; Analysis 2.4). The number of treatment responders was, however, significantly larger in the manual acupuncture group at all of the analysed time points (Analysis 2.5, 152 participants) (8 weeks: RR 1.22, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.47; 12 weeks: RR 1.23, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.39; 24 weeks: RR 1.23, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.38).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Manual acupuncture versus routine care/conventional medicine, Outcome 3 Blood pressure: systolic.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Manual acupuncture versus routine care/conventional medicine, Outcome 4 Blood pressure: diastolic.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Manual acupuncture versus routine care/conventional medicine, Outcome 5 Blood pressure: number responding to treatment.

Sleep quality

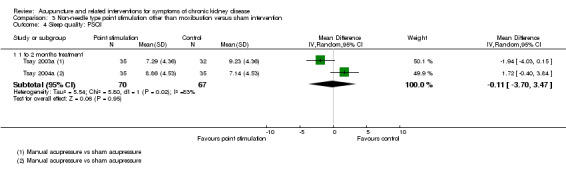

There was no significant difference between manual acupressure and sham acupressure in terms of global Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index scores at four weeks (Analysis 3.4.1 (2 studies, 137 participants): MD ‐0.11, 95% CI ‐3.70 to 3.47; I2 = 83%).

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Non‐needle type point stimulation other than moxibustion versus sham intervention, Outcome 4 Sleep quality: PSQI.

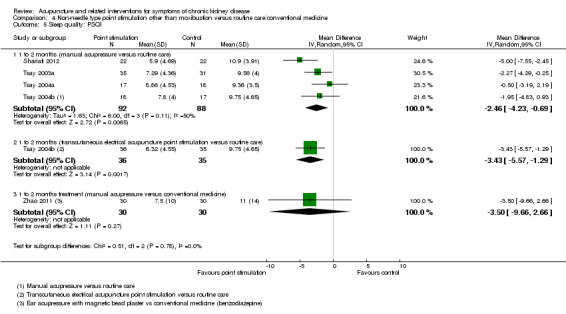

In the pooled analysis of global Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index scores, manual acupressure showed a significant improvement compared with routine care or conventional medicine at four weeks (Analysis 4.5.1 (4 studies, 180 participants): MD ‐2.46, 95% CI ‐4.23 to ‐0.69; I2 = 50%). Tsay 2004b reported a significant improvement in sleep quality with transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation when compared to routine care (Analysis 4.5.2 (71 participants): MD ‐3.43, 95% CI ‐5.57 to ‐1.29). Zhao 2011 found no significant difference between ear acupressure and conventional treatment (Analysis 4.5.3).

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Non‐needle type point stimulation other than moxibustion versus routine care/conventional medicine, Outcome 5 Sleep quality: PSQI.

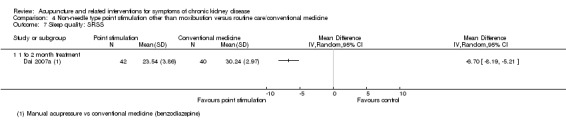

Dai 2007a reported significant improvements in sleep disturbance with manual acupressure compared with benzodiazepine medication (1 mg of estazolam) at four weeks using the self rating scale for sleep (scale of 10 to 50) (Analysis 4.7.1 (82 participants): MD ‐6.70, 95% CI ‐8.19 to ‐5.21).

4.7. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Non‐needle type point stimulation other than moxibustion versus routine care/conventional medicine, Outcome 7 Sleep quality: SRSS.

Quality of life

Three QOL instruments, including the SF‐36 (Tsay 2003a), WHOQOL‐BREF (Su 2009) and KDQOL V 1.3 (Sun 2008a; Qiu 2012) were used (scales ranged from 0 to 100).

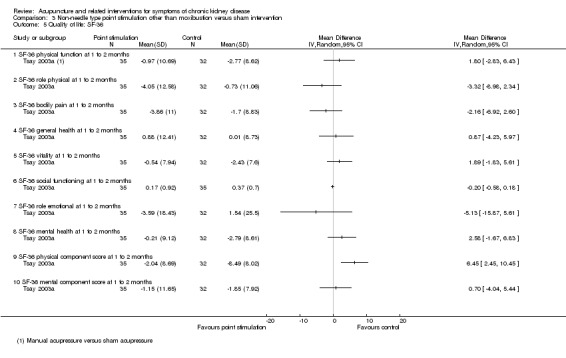

Tsay 2003a reported manual acupressure showed significantly less benefits compared with sham acupressure in terms of the SF‐36 physical component score at four weeks (Analysis 3.5.9 (68 participants): MD 6.45, 95% CI 2.45 to 10.45). There were no significant differences for the remaining sub‐domains.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Non‐needle type point stimulation other than moxibustion versus sham intervention, Outcome 5 Quality of life: SF‐36.

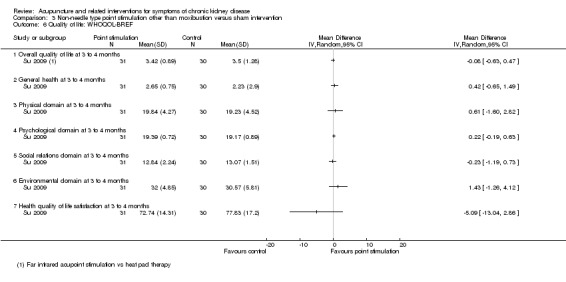

Su 2009 reported far infrared radiation on point SP6 compared with sham intervention (i.e. a heat pad application) showed no significant effect on any all sub‐domain of the WHOQOL‐BREF at 12 weeks (Analysis 3.6).

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Non‐needle type point stimulation other than moxibustion versus sham intervention, Outcome 6 Quality of life: WHOQOL‐BREF.

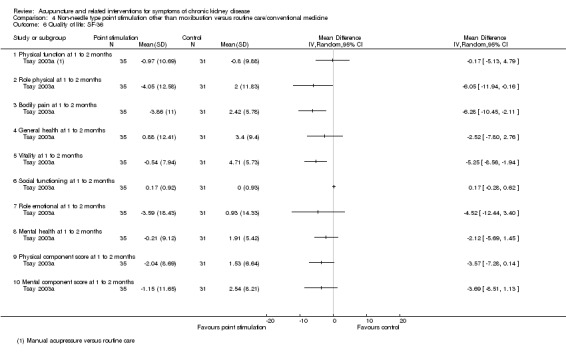

Tsay 2003a reported significantly favourable effects of manual acupressure compared with routine care at four weeks on the SF‐36 physical role (Analysis 4.6.2 (66 participants): MD ‐6.05, 95% CI ‐11.94 to ‐0.16), bodily pain (Analysis 4.6.3 (66 participants): MD ‐6.28, 95% CI ‐10.45 to ‐2.11), and vitality (Analysis 4.6.5 (66 participants): MD ‐5.25, 95% CI ‐8.56 to ‐1.94) sub‐domains.

4.6. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Non‐needle type point stimulation other than moxibustion versus routine care/conventional medicine, Outcome 6 Quality of life: SF‐36.

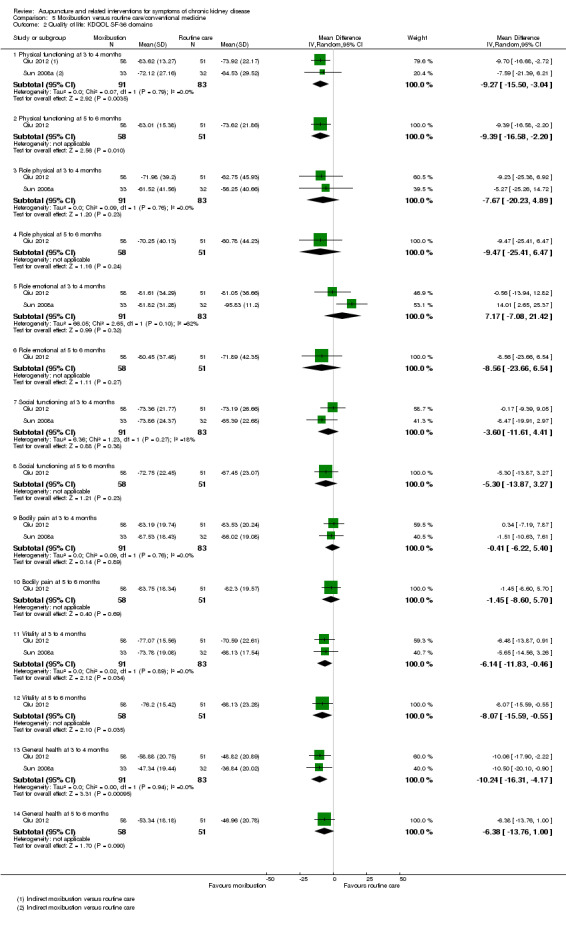

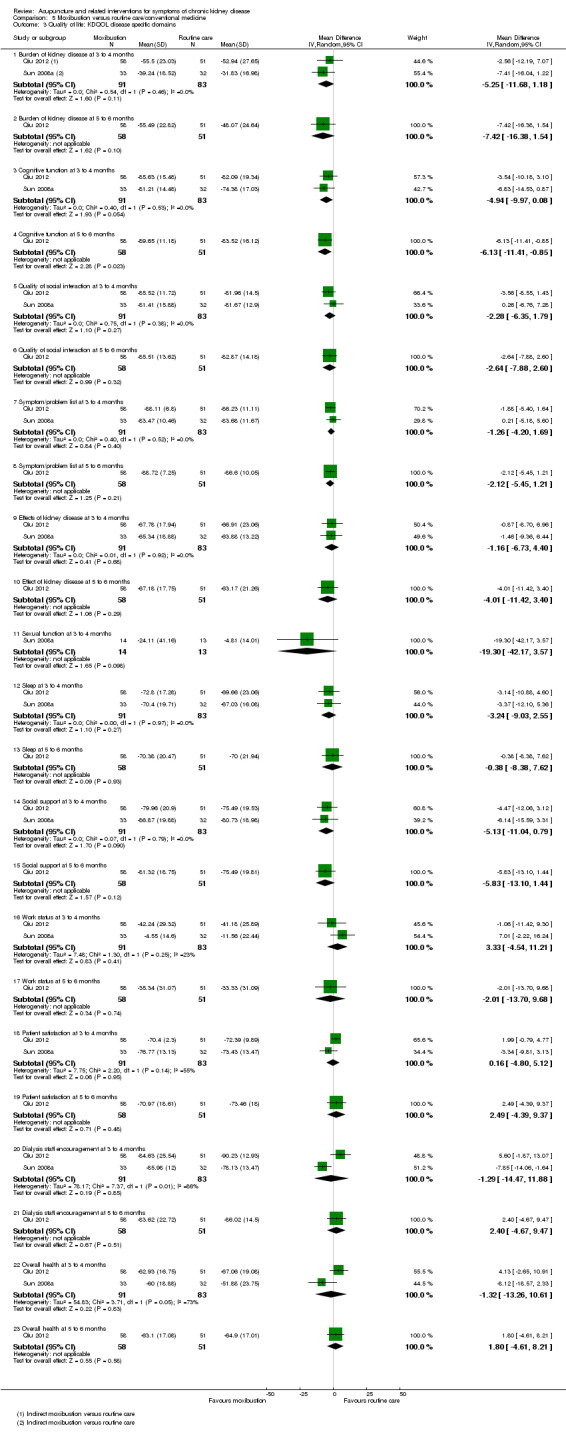

Moxibustion showed better results than routine care on the KDQOL sub‐domains of physical functioning (Analysis 5.2.3 (2 studies, 174 participants): MD ‐9.27, 95% CI ‐15.50 to ‐3.04, I2 = 0%), vitality (Analysis 5.2.11 (2 studies, 174 participants): MD ‐6.14, 95% CI ‐11.83 to ‐0.46, I2 = 0%), and general health (Analysis 5.2.13 (2 studies, 174 participants): MD ‐10.24, 95% CI ‐16.31 to ‐4.17, I2 = 0%) three to four months from baseline.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Moxibustion versus routine care/conventional medicine, Outcome 2 Quality of life: KDQOL SF‐36 domains.

A six‐month follow‐up observation of moxibustion treatment (Qiu 2012) revealed favourable effects compared with routine care on the sub‐domains of physical functioning (Analysis 5.2.2 (109 participants): MD ‐9.39, 95% CI ‐16.58 to ‐2.20), vitality (Analysis 5.2.2 (109 participants): MD ‐8.07, 95% CI ‐15.59 to ‐0.55), and cognitive function (Analysis 5.3.4 (109 participants): MD ‐6.13, 95% CI ‐11.41 to ‐0.85).

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Moxibustion versus routine care/conventional medicine, Outcome 3 Quality of life: KDQOL disease specific domains.

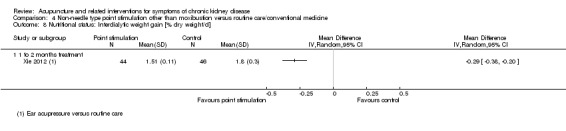

Nutritional status

Xie 2012 reported ear acupressure showed significantly less interdialytic weight gain compared to routine treatment at eight weeks (Analysis 4.8.1 (90 participants): MD ‐0.29 % dry weight/d, 95% CI ‐0.38 to ‐0.20).

4.8. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Non‐needle type point stimulation other than moxibustion versus routine care/conventional medicine, Outcome 8 Nutritional status: Interdialytic weight gain [% dry weight/d].

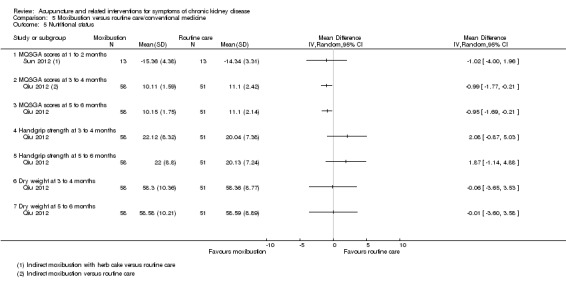

Effects of moxibustion compared with routine care for nutritional improvements were assessed using modified quantitative subjective global assessment (MQSGA) scores.

Sun 2012 reported MQSGA scores at eight to nine weeks were not significantly higher in the moxibustion group compared with the routine care at eight to nine weeks (Analysis 5.5.1).

5.5. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Moxibustion versus routine care/conventional medicine, Outcome 5 Nutritional status.

Qiu 2012 reported MQSGA scores (scale of 7 to 35) were significantly higher in the moxibustion group at both 12 weeks (Analysis 5.5.2 (109 participants): MD ‐0.99, 95% CI ‐1.77 to ‐0.21) and 24 weeks (Analysis 5.5.3 (109 participants): MD ‐0.95, 95% CI ‐1.69 to ‐0.21) when compared to routine care.

There was no difference between the moxibustion and the routine care group for handgrip strength (Analysis 5.5.4; Analysis 5.5.5) and dry weight (Analysis 5.5.6; Analysis 5.5.6).

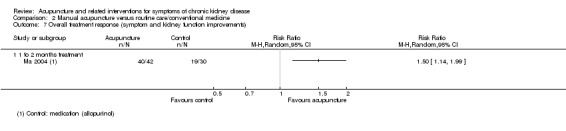

Overall treatment responses (symptom and kidney function improvement)

Ma 2004 and Zhao 1995 measured overall treatment responses and grouped treatment response into three (excellent, effective, failed) (Ma 2004) or four (cured, markedly effective, fair, ineffective) categories (Zhao 1995). Both studies defined the treatment response according to symptom reduction and kidney function improvements, measured by blood creatinine, uric acid, urea nitrogen and 24‐hour urinary protein excretion. Ma 2004 dichotomised outcomes by merging patients who displayed excellent and effective responses into one group and those who failed into another group, and Zhao 1995 merged patients who were cured or displayed markedly effective response into one group and the patients who displayed a fair and ineffective response into another.

Ma 2003 reported acupuncture showed significant improvement in overall symptoms and kidney function compared with conventional medication (allopurinol 200 to 300 mg/d and ibuprofen 600 mg/d) at 10 days (Analysis 2.7.1 (82 participants): RR 1.50, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.99).

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Manual acupuncture versus routine care/conventional medicine, Outcome 7 Overall treatment response (symptom and kidney function improvements).

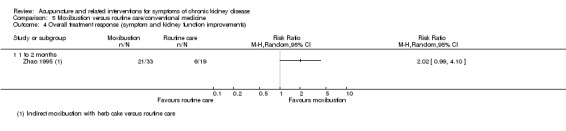

Zhao 1995 reported moxibustion showed a non‐significant improvement in overall symptoms and kidney function compared with routine care at seven weeks (Analysis 5.4.1 (152 participants): RR 2.02, 95% CI 0.99 to 4.10).

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Moxibustion versus routine care/conventional medicine, Outcome 4 Overall treatment response (symptom and kidney function improvements).

Xerostomia

On a scale of 0 to 100, Xie 2012 reported ear acupressure significantly improved xerostomia compared with routine care at eight weeks (Analysis 4.9.1 (90 participants): MD ‐8.01, 95% CI ‐9.21 to ‐6.81).

4.9. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Non‐needle type point stimulation other than moxibustion versus routine care/conventional medicine, Outcome 9 Xerostomia [scale 0 to 100].

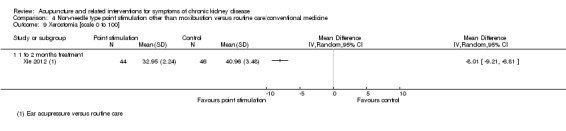

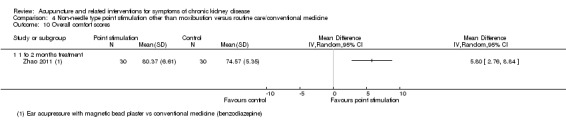

Overall comfort scales

On a scale of 0 to 100, Zhao 2011 reported ear acupressure showed significant improvement in overall comfort compared with routine care at eight weeks (Analysis 4.10.1 (60 participants): MD 5.80, 95% CI 2.76 to 8.84).

4.10. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Non‐needle type point stimulation other than moxibustion versus routine care/conventional medicine, Outcome 10 Overall comfort scores.

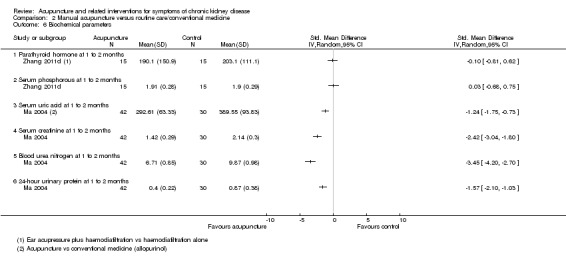

Biochemical parameters

The biochemical parameters assessed in the eligible studies included parathyroid hormone, serum phosphorus, serum uric acid, serum creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, 24‐hour urinary protein excretion, serum calcium, serum albumin, serum prealbumin, serum alkaline phosphatase, urea reduction ratio, serum haemoglobin, serum calcium‐phosphorus ratio, plasma sodium concentration, amount of ultrafiltration, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein, interleukin‐6, serum middle molecule and serum potassium level.

Ma 2004 reported manual acupuncture produced significantly lower serum uric acid (Analysis 2.6.3 (72 participants): SMD ‐1.24, 95% CI‐1.75 to ‐0.73), serum creatinine (Analysis 2.6.4 (72 participants): SMD ‐2.42, 95% CI ‐3.04 to ‐1.80), blood urea nitrogen (Analysis 2.6.5 (72 participants): SMD ‐3.45, 95% CI ‐4.20 to ‐2.70) and 24‐hour urine protein (Analysis 2.6.6 (72 participants): SMD ‐1.57, 95% CI ‐2.10 to ‐1.03) levels compared with conventional medication (allopurinol 200 to 300 mg/d and ibuprofen 600 mg/d) at 10 days in patients with gouty kidney disease.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Manual acupuncture versus routine care/conventional medicine, Outcome 6 Biochemical parameters.

Xie 2012 reported ear acupressure plus haemodiafiltration versus haemodiafiltration alone showed no difference in terms of parathyroid hormone, serum phosphorus, and plasma sodium concentration levels. Similarly, Hsu 2009 reported there was no difference for far infrared radiation on the acupuncture points versus sham intervention in terms of serum calcium, phosphorus, serum albumin, serum alkaline phosphatase, urea reduction ratio, parathyroid hormone level and calcium‐phosphorus ratio.

Sun 2012 reported moxibustion resulted in a higher amount of ultrafiltration compared with routine care at 60 days (Analysis 5.6.3 (26 participants): SMD 1.14, 95% CI 0.30 to 1.97), improved serum prealbumin (SMD 1.86, 95% CI 0.91 to 2.80), and reduced the levels of inflammation‐related parameters such as high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein (Analysis 5.6.13 (26 participants): SMD ‐1.91, 95% CI ‐2.86 to ‐0.95) and interleukin‐6 (Analysis 5.6.14 (26 participants): SMD ‐1.42, 95% CI ‐2.30 to ‐0.54).

5.6. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Moxibustion versus routine care/conventional medicine, Outcome 6 Biochemical parameters.

Xie 2012 and Qiu 2012 assessed Kt/V in haemodialysis patients and found no significant difference between ear acupressure or moxibustion and routine care (Analysis 5.6.18; Analysis 5.6.19). Cheng 2012 measured residual kidney Kt/V, total Kt/V, residual kidney creatinine clearance and total creatinine clearance in peritoneal dialysis patients. There was a significant benefit with moxibustion compared to conventional medicine only for residual renal creatinine clearance (Analysis 5.6.22 (60 participants): SMD 2.49, 95% CI 1.81 to 3.18).

Adverse events

Che‐Yi 2005 reported adverse events included elbow soreness (two patients in the manual acupuncture and one in the sham acupuncture group) and minimal bleeding (three in the sham acupuncture group. Two studies reported that no adverse events had occurred (Rui 2002; Hsu 2009). None of the other included studies reported whether adverse events had occurred. Some practitioners injured their hand during finger acupressure interventions (Tsay 2004a).

Subgroup analysis

We initially intended to conduct subgroup analyses to explore the potential factors related to the heterogeneity of the study results (i.e. type of acupuncture interventions, stage of CKD and type of control intervention). There were insufficient studies per comparison to investigate these subgroups.

Sensitivity analysis

We intended to perform sensitivity analyses based on methodological quality assessment in terms of random sequence generation, allocation concealment and participant and assessor blinding; the methods of CKD definition and classification; or the use of validated scales for outcome measures. However, these analyses were not conducted because most of the studies had unclear or high risk of bias; did not describe their CKD definition; or did not use validated outcomes.

Assessment of reporting bias

We initially proposed to assess publication bias if there were sufficient numbers of studies. Paucity of data meant that we were unable to assess for publication bias on funnel plots.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This review included 24 studies that involved 1787 participants. We could not perform meta‐analyses of results for most outcomes because of considerable clinical heterogeneity in terms of the acupuncture interventions, comparators and conditions tested. Most studies measured the short‐term effects of acupuncture interventions at time periods equal to or less than two months. No study measured pain, which was one of the primary outcomes in this review.

Several single studies reported significant findings. In three small studies, manual acupressure reduced the severity of depression compared with routine care at four weeks (MD ‐4.29, 95% CI ‐7.48 to ‐1.11, I2 = 0%), although this effect was relatively modest compared with that of other non‐pharmacological interventions, such as cognitive behavioural group therapy versus routine care in dialysis patients (MD ‐7.10, 95% CI ‐10.88 to ‐3.32) (Duarte 2009). One study reported that transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation showed significant benefit compared with routine care (MD ‐6.26, 95% CI ‐10.27 to ‐2.25). There was improvement in uraemic pruritus for haemodialysis patients receiving manual acupuncture compared with sham acupuncture (MD ‐20.20, 95% CI ‐22.99 to ‐17.41) and an oral antihistamine (RR 1.38, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.72). Manual acupuncture was comparable with oral calcitriol (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.12). One study in which manual acupressure was compared with an unspecified control intervention found a reduction of uraemic pruritus at six weeks (MD ‐6.50, 95% CI ‐7.50 to ‐5.50), which decreased over time but remained significant at 18 weeks (MD ‐4.80, 95% CI ‐6.23 to ‐3.37).

Three small studies reported a reduction in the severity of fatigue for patients receiving manual acupressure compared with routine care at four weeks (MD ‐1.19, 95% CI ‐1.77 to ‐0.60). One study of manual acupuncture compared with domperidone found favourable effects in overall gastrointestinal symptoms (MD ‐2.50, 95% CI ‐3.48 to ‐1.52), bloating (MD ‐0.82, 95% CI ‐1.13 to ‐0.51), and early satiety (MD ‐0.72, 95 CI ‐1.01 to ‐0.43). One study comparing manual acupuncture combined with antihypertensive medication with medication alone for pre‐dialysis CKD patients reported a significantly larger number of treatment responders, which was sustained at six months (RR 1.23, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.38). In four studies, manual acupressure improved sleep quality compared with routine care (MD ‐2.46, 95% CI ‐4.23 to ‐0.69). Transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation significantly improved sleep quality compared with routine care in one study (MD ‐3.43, 95% CI ‐5.57 to ‐1.29). One study comparing manual acupuncture with benzodiazepine reported significant sleep improvement (MD ‐6.70, 95% CI ‐8.19 to ‐5.21).

One study comparing acupressure with routine care, showed Improvements in quality of life, with improvements to the SF‐36 domains of role physical, bodily pain and vitality. Two studies in which moxibustion was compared with routine care reported improvements in the KDQOL domains of physical functioning, vitality and general health at three to four months, and physical functioning, vitality and cognitive function at six months. There was no significant difference between acupuncture interventions and comparators in many of the other domains of quality of life. Reasons for inconsistent results may include a possibility of effectiveness/ineffectiveness of acupuncture interventions on selective aspects of quality of life, inadequate power of studies to detect statistically meaningful differences in each subdomain of instrument, or a lack of instrument (i.e. generic questionnaires such as the SF‐36) responsiveness in patients undergoing dialysis (Patrick 2008).

Subjective assessments of nutritional status measured by MQSGA scores showed an improvement in haemodialysis patients receiving moxibustion compared with routine care at 12 weeks (MD ‐0.99, 95% CI ‐1.77 to ‐0.21) and 24 weeks (MD ‐0.95, 95% CI ‐1.69 to ‐0.21), but not at eight to nine weeks. One small study of manual acupuncture versus allopurinol and ibuprofen reported a short‐term benefit in the overall treatment responses, defined by symptom and kidney function improvement (RR 1.50, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.99). One study in which ear acupressure was compared with routine care found reductions in interdialytic weight gain (MD ‐0.29 % dry weight/d, 95% CI ‐0.38 to ‐0.20) and xerostomia (MD ‐8.01, 95% CI ‐9.21 to ‐6.81). In another small study there was an improvement in overall subjective comfort (MD 5.80, 95% CI 2.76 to 8.84). There were some significant changes in biochemical parameters after acupuncture interventions, including serum uric acid, serum creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, 24‐hour urine protein, amounts of ultrafiltration, serum prealbumin, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein, interleukin‐6, and residual kidney creatinine clearance.

The majority of studies comparing acupuncture interventions with sham intervention found no evidence of between‐group difference in the reduction of symptoms. Most studies lacked reports on whether adverse events occurred, which makes an assessment of the safety of acupuncture difficult. Some major events, such as death and hospitalisation, occurred during the study process, but there was no description of a possible association with the intervention. One study reported minor adverse events, such as soreness and minimal bleeding at needled points. Most studies suffered from high or unclear risk of bias, which render the reported benefits in the review questionable. Overall, there is currently little evidence that acupuncture interventions were more effective than sham interventions or were safe when used in CKD patients.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The majority of the studies were conducted in China and Taiwan, which may result in the limited generalisability of the study findings in countries that have different health care systems and cultural backgrounds. For many of the studies, the participants were enrolled in haemodialysis centres or hospitals and were inpatients. Thus, the clinical contexts in included studies may be different from those in community or primary care settings. The stages of CKD were diverse and included pre‐dialysis CKD, maintenance haemodialysis, and peritoneal dialysis. Analyses based on stages of CKD were not possible because of the paucity of data. A wide range of acupuncture interventions and comparators was used, showing considerable clinical heterogeneity. We could not perform subgroup analyses to investigate this clinical heterogeneity because of the small number of studies within each subgroup; thus, the influence of clinical heterogeneity on the review results remains unclear. There was no evidence to suggest that particular types of acupuncture interventions, such as acupuncture, acupressure, moxibustion and far‐infrared radiation, are more effective. Most studies involving haemodialysis patients lacked reports on when the acupuncture treatment was provided (i.e. before, during or after a dialysis session). Because maintenance haemodialysis requires regular access to dialysis facilities, the allocation of additional patient time and resources for acupuncture treatments may be challenging. Additional visits or off‐site acupuncture may not be affordable to haemodialysis patients who have a reduced level of daily activity (Stener‐Victorin 2011). The safety of intradialytic or post‐dialysis acupuncture remains unclear, especially for patients experiencing adverse events because of haemodynamic instability or post‐dialysis fatigue. Acupuncture interventions before the start of the dialysis session may avoid such problems, but the time and space allocation required for the treatments may not be available in a busy dialysis schedule. Overall, the acceptability of acupuncture to patients and dialysis staff and the optimal delivery process in a given clinical context remains unclear. None of the included studies comparing acupuncture interventions with active controls, such as conventional medication, mentioned whether the aim of the research was to investigate the equivalence or non‐inferiority of acupuncture to an active comparator.

Quality of the evidence

Most studies had unclear or high risk of bias, especially in the domains of allocation concealment, blinding of participants, incomplete outcome reporting and selective outcome reporting (Figure 2; Figure 3). None of the included studies reported on allocation concealment which may make studies susceptible to significant risk of selection bias (Schulz 2002). Many studies compared acupuncture interventions with routine care or other active comparators, which made the blinding of patients and practitioners difficult and inevitably increased the risk of performance bias. In such cases, the appropriate blinding of outcome assessors can reduce risk of detection bias. However, for many studies, the blinding of outcome assessors was unclear. Most studies did not transparently report the number of participants for each outcome assessment, which increased the risk of bias based on incomplete outcome reporting. All included studies lacked information about where the study protocol can be accessed; thus, whether the studies selectively reported outcomes was unclear. Authors from only six studies replied to our requests for information; thus, the additional information was insufficient to determine whether those uncertainties come from a lack of reporting or from inadequate study design. Overall, the quality of current evidence is seriously impeded by these unclear or high risk of bias. The reported benefits should be interpreted with caution.

Potential biases in the review process

Five of the 24 included studies were quasi‐randomised studies, which calls for the careful interpretation of their findings. This review investigated symptom management. Thus, other important outcomes, such as mortality, hospitalisation, and preventing the progress of CKD were not analysed. We could not examine whether publication bias existed because of the insufficient number of studies. However, there is a possibility of publication bias because most of the studies reported positive outcomes. Pooled effect estimates were possible only for a few outcomes, such as depression, fatigue and sleep quality because of the paucity of data. Thus, the review largely relied on the results from single studies. Participants in most studies were those undergoing haemodialysis. The review could not explore the role of acupuncture interventions for patients with pre‐dialysis stage 3 to 4 CKD, those undergoing peritoneal dialysis or those without any renal replacement therapy. Most of the studies measured only short‐term outcomes (within one to two months); the long‐term effectiveness and safety of acupuncture interventions remain largely unknown in this review.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We have performed systematic reviews of the effects and the safety of acupuncture and acupressure for symptom management in patients with ESKD (Kim 2010a; Kim 2010b). Most of the analysed studies were also included in this review. There was little difference in the overall study findings between those two reviews and this review, except for the wider scope of population (patients with CKD stage 3 to 5) and intervention (diverse types of acupuncture interventions).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

We cannot make any solid recommendations unless further high‐quality randomised studies provide sufficient information. Clinicians and acupuncture practitioners should inform CKD patients who want to receive acupuncture interventions about the insufficient evidence of their effectiveness and safety. Manual acupressure may be a feasible add‐on treatment option for short‐term relief of depression, fatigue, and sleep disturbance in patients undergoing regular haemodialysis. Further well‐designed research should confirm the reported benefits and safety of such interventions before they are recommended in clinical practice. Indirect moxibustion may be used as complementary intervention for patients suffering from diminished quality of life in domains of physical function and perceived general health, although very low quality of evidence from two randomised studies supports such use. For other non‐needle forms of acupuncture‐related interventions such as ear acupressure, far infrared irradiation and transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation, we cannot make any clinical implication due to the paucity of data from reliable studies. Acupuncture interventions should be provided as a complementary, not a completely alternative, intervention in line with conventional managements because current evidence is mainly based on adjunctive uses of acupuncture to routine care and not on adequately designed equivalence or non‐inferiority testing studies. Qualified practitioners with appropriate clinical experience should implement acupuncture with concerns about any harm related to intervention. We discourage the long‐term application of acupuncture for more than three months without periodical screening for safety and effectiveness because of the lack of relevant information to justify such use.

Implications for research.