May 17, 2021

About the NAM series on Emerging Stronger After COVID-19: Priorities for Health System Transformation

This discussion paper is part of the National Academy of Medicine’s Emerging Stronger After COVID-19: Priorities for Health System Transformation initiative, which commissioned papers from experts on how 9 key sectors of the health, health care, and biomedical science fields responded to and can be transformed in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. The views presented in this discussion paper and others in the series are those of the authors and do not represent formal consensus positions of the NAM, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, or the authors’ organizations. Learn more: nam.edu/TransformingHealth

Introduction and Sector Overview

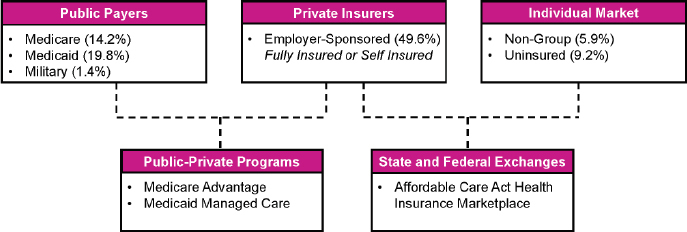

In contrast with other high-income countries, health care insurance and payment in the United States is highly fragmented. America’s multi-payer system spans an array of entities, including publicly financed programs (e.g., Medicare, Medicaid) and commercial insurers and health plans. Figure 1 provides an overview of the different types of payers and populations in the U.S. [1] This paper will focus on the perspective of payers covering Medicare, Medicaid, and adults with fully insured employer health plans, which together encompass the majority of Americans.

FIGURE 1. Overview of America’s Multi-Payer Landscape.

These payers aim to serve several functions in the U.S. health care system, including offering protection against the financial impact of unexpected health events, providing patients with access to a broad set of health services delivered by a network of health care professionals, coordinating those services, and using measurement and incentives to increase the affordability and quality of care delivery [2]. Yet the common functions of payers can take many different forms with regards to operational arrangements (e.g., stand-alone plans versus joint ventures with delivery organizations), benefit design (e.g., covered services, cost distribution), and payment methodologies (e.g., volume- versus population-based payments). A key area of change for payers over the past decade has been the advent of so-called “value-based care,” in which payers in both the public and private sector have sought to transition away from fee-for-service (FFS) arrangements to alternative payment models (APMs) that link reimbursement to the quality and outcomes of care delivery [3].

It is amidst this period of renovation to the architecture of the U.S. health care system that COVID-19 struck. The public health emergency—which remains ongoing at the time of this paper’s publication—has had tremendous consequences for the health of American society and the financial stability of the American health care system. During the spring of 2020, payers took steps based on regulatory requirements and recommendations to expand access to health services for both COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 health conditions (e.g., waiving administrative requirements, reimbursing telehealth). Many payers also independently deployed financial support and capital to stabilize providers, and leveraged their technological capabilities and community relationships to support outbreak response, from coordinating non-medical services to supporting immunization campaigns.

However, payers’ pandemic response capabilities and their obligations to regulators, employers, providers, and patients evolved as high caseloads persisted and the downstream consequences of COVID-19 began to manifest. For example, trends in medical spending and utilization shifted as outbreaks escalated over the course of 2020. Payers initially experienced cost reductions due to care delays, but then experienced a subsequent increase in operating expenses due to the growing volume of COVID-19 patients and the resumption of deferred health services. Likewise, as insurance is an industry premised on forecasting and risk assessment, the fundamentally unpredictable nature of a pandemic created significant challenges for payer operations in 2021 (e.g., pricing, enrollment).

In this paper, leaders from the payer sector seek to describe the experience of health insurers during COVID-19 and identify the key challenges and opportunities learned from the pandemic and beyond. It is important to acknowledge that as an ongoing public health emergency, empirical evidence on health care costs and payment policies for COVID-19 remains nascent at this time, and data on the specific actions of payers may vary according to differences in health insurance products, local market needs, and regulatory requirements. Nevertheless, one year into the pandemic, it is evident that the unprecedented disruption to the health care system as a result of COVID-19 provides a unique opportunity for payers to improve the efficiency and equity of health care financing in America. Consequently, the goal of this paper is to provide a preliminary review of payers’ experiences during COVID-19 to date, and to highlight the key lessons for how payers and regulators can navigate the uncertainties of COVID-19 and leverage the newfound momentum for health care reform, with a particular focus on improving affordability and accessibility.

The Payer Response to COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic imposed a sudden and significant shock to America’s fragmented health care system. While the volatility of COVID-19 did create challenges for payers (e.g., actuarial forecasting), the unprecedented reduction in health care spending resulted in improved financial performance for many health insurers during 2020. Many payers leveraged their resources and role to support patients, providers, and other stakeholders as the health care system evolved at unprecedented speed. For example, insurers facilitated the management and delivery of both COVID-19-related and non-pandemic health services across multiple care delivery partners. Likewise, health plans worked to aggregate and coordinate the new federal and state mandates, rules, waivers, and guidance regarding traditional health services (e.g., prescriptions, benefits) and COVID-19-related care (e.g., testing, treatment). Furthermore, payers collaborated with providers and developed partnerships with other sectors (e.g., public health, community-based organizations) to support the implementation of new flexibilities, communicate key changes, and help patients, the public, and employers to navigate the rapidly shifting delivery environment.

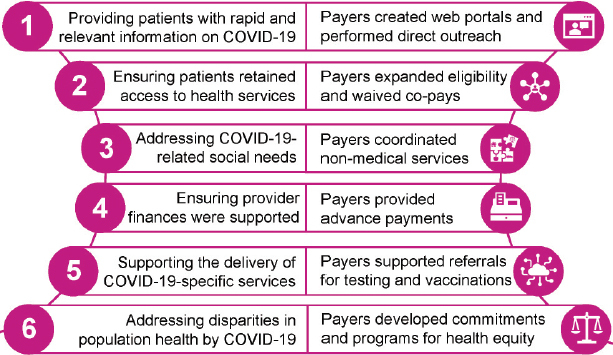

This section of the paper seeks to capture the primary areas of focus for the payer sector’s response to the pandemic. While evidence on the scale and effects of payer actions is difficult to quantify at this stage, given that COVID-19 remains an evolving public health emergency at the time of this paper’s publication, and it is challenging to generalize given the fragmented nature of America’s multi-payer environment, the authors seek to offer salient examples from their vantage point. The key aspects of payers’ COVID-19 response include:

-

1.

Providing rapid and relevant information to key stakeholders;

-

2.

Ensuring patients retained access to health services despite disruptions to in-person delivery;

-

3.

Addressing the non-medical needs of patients, particularly in light of the pandemic’s disparate impact on high-risk populations;

-

4.

Ensuring providers received adequate financial support amidst sudden revenue reductions and shifts toward virtual care;

-

5.

Supporting the delivery of pandemic-specific services, including COVID-19 testing, treatments, and vaccinations, and the distribution of personal protective equipment (PPE); and

-

6.

Providing resource commitments and program support to address health inequities (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. Payer Responses to COVID-19 Challenges.

Adapting to the Pandemic: Role-Shifting, Partnerships, and Program Development

Providing Patients With Rapid and Relevant Information

Amidst an uncertain informational landscape, payers worked to synthesize evidence and provide outreach and education to help patients stay safe during the pandemic [4]. Within the public sector, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) posted regular updates to frequently asked questions for beneficiaries, and issued proactive guidance to Medicare Advantage Organizations, Part D Sponsors, and Medicare-Medicaid Plans about the flexibilities (e.g., changes to benefits, waivers to cost-sharing) available to health plans covering Medicare beneficiaries during the public health emergency [5]. Within the private sector, some insurers established patient-facing web portals to compile real-time information regarding coverage options for special enrollment, which often differed across individual, employer, Medicaid, and Medicare insurance markets [6].

Health plans also leveraged their customer service teams to disseminate and answer coverage-specific questions from patients and employers using multiple modalities. For example, some payers deployed their patient services representatives to provide patients with the latest information on applicable government mandates. Other payers organized virtual town halls, with a particular focus on outreach to high-risk patients (e.g., the elderly) [7]. Payers’ outreach efforts also extended beyond informational resources into direct clinical assistance. Examples include supporting virtual clinical assessments and facilitating connections with providers. Some plans even deployed care managers to hard-hit network hospitals to assist with post-acute care coordination.

Retaining Access to Health Services

In addition to complying with federally mandated coverage requirements for many components of COVID-19 diagnosis and treatment, payers also sought to reduce financial barriers to coverage for non-COVID-19 care for the duration of the public health emergency [8,9]. In the public sector, CMS required Medicare Advantage organizations to waive certain referral requirements and cost-sharing policies, all without 30-day notification periods, to enable beneficiaries to access necessary care. Likewise, some state Medicaid programs expanded eligibility and benefits for long-term services and supports for seniors and patients with disabilities [10]. For employer-sponsored insurance, many plans eliminated late fees, extended eligibility allowances for furloughed employees, and offered premium deferral mechanisms to balance employers’ concerns of fiscal sustainability with the need to provide short-term relief to maintain members’ coverage [11,12]. However, waivers for coverage and cost-sharing did not extend to out-of-network billing for both COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 health services. Additionally, the uptake of these policies varied across self-insured entities, which account for the majority of covered workers and are beyond the scope of this paper.

A key area of focus for payers across the sector was mitigating potential disruptions to patient access to prescription drugs (e.g., due to shortages or shelter-in-place restrictions) [13]. CMS issued guidance to Part D sponsors, including reimbursement for out-of-network pharmacies and permissions for home delivery and prior authorizations [14]. Within the private sector, many insurers (e.g., all 36 Blue Cross Blue Shield Association companies) temporarily waived early refill limits on 30-day maintenance medication prescriptions and extended prior authorizations on 90-day medication supplies [15,16].

Addressing COVID-19-Related Social Needs

COVID-19 exposed and exacerbated many longstanding health inequities in the U.S., with the pandemic disproportionately affecting racial and ethnic minorities and socioeconomically disadvantaged populations. Payers took multiple actions to respond to these inequities.

First, at the policy level, CMS issued guidance that the agency would exercise enforcement discretion for mid-year benefit enhancements by Medicare Advantage organizations, including benefits addressing social needs (e.g., meal delivery, transportation services) [17]. While data on mid-year changes is still emerging, the number of Medicare Advantage plans offering Special Supplemental Benefits for the Chronically Ill more than tripled between 2020 and 2021 [18]. The majority of states also implemented new initiatives to address the social determinants of health through their Medicaid programs, with some programs occurring in conjunction with insurers [19]. For example, Pennsylvania implemented new requirements for Medicaid Managed Care Organizations to partner with community-based organizations, with implications for reimbursement.

Second, some commercial payers took independent action to address inequities, with select examples from the sector summarized in Table 1 [9]. For example, some payers developed a coordination function to match high-need patients with relevant community organizations [20]. A few plans worked to augment financially strapped public assistance programs, such as direct outreach efforts and enrollment assistance for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits and financial support for community organizations working on rapid rehousing solutions for the homeless population. Other payers sought to address the challenge of food insecurity by coordinating the home delivery of medically tailored meals and groceries during the pandemic, with a focus on reaching both high-risk and COVID-19 positive patients. Additionally, plans worked to address the mental health burden of the pandemic by funding support programs (e.g., Crisis Text Line, domestic violence prevention programs) and coordinating virtual services for social connection in specific populations (e.g., older adults experiencing loneliness) [9]. While these actions represent select examples of payer engagement, it is important to note that there are limited data on the scope and impact of payer actions for health equity during the pandemic. Data collection and evaluation is needed to assess the benefits and challenges of different pandemic-era pilots, and effectuating systemic change will require translating philanthropic investments into structural changes in benefit design and payment policy, for which uptake to date has been slow [21].

TABLE 1. Payer Support for the Social Determinants of Health.

| Member Needs | Example of Payer Response |

|---|---|

| Service Coordination |

|

| Food Insecurity |

|

| Transportation Barriers |

|

| Mental Health Services |

|

Financial Support for Health Care Providers

Clinicians and health care organizations faced unprecedented financial challenges in spring 2020 amidst a sharp decline in visits that were paid on a FFS basis, as individuals complied with safer-at-home and physical distancing protocols, delaying visits to their health care providers [22]. The Paycheck Protection Program and other federal initiatives did provide substantial resources to hospitals and other providers to help ameliorate the resulting losses. However, with grants from the Provider Relief Fund favoring larger health systems and Medicare’s Advanced Payments program providing limited support to safety-net providers, many smaller, independent practices—which at baseline lack the levels of capital reserves possessed by hospitals and provider groups—continued to face severe cash shortages [23,24,25].

Given the delays and flux in federal relief efforts, commercial payers were well-positioned to offer support to clinicians to meet payroll, operating expenses, and ongoing patient needs—particularly considering that the decline in health care spending and utilization during COVID-19 had translated into improvements in insurers’ financial performance in terms of commercial payers’ gross margins and medical loss ratios [26,27]. To this end, health plans adopted an array of alternative financing strategies to infuse short-term capital into the care delivery system. For example, some plans coordinated direct financial support for providers and hospitals through financing guarantees, advance payments, and opportunities to restructure contracts from FFS arrangements to value-based contracts (e.g., risk-sharing capitated payments) [30]. For providers already operating under value-based contracts, some plans worked to provide up front payments of quality bonuses or expected savings. In addition to providing infusions of cash (the amounts of which varied between payers and due to lack of data cannot be comprehensively reported), many plans committed to eliminating utilization management protocols or prior authorization in markets experiencing challenges with inpatient, intensive care, or post-acute care capacity. Furthermore, some plans developed payment models that offered participating providers guaranteed revenue in exchange for a commitment to enter a value-based payment arrangement at a future date [16].

Addressing COVID-19-Specific Delivery System Needs

Payers have worked to support the distribution of medical supplies and services throughout the pandemic, beginning with testing and tracing efforts. For testing, some plans have directly invested in diagnostic development and supported supply procurement, such as funding the development of alternative reagents and medical supplies for collecting patient samples (e.g., polyester swabs and saline transport) [31]. For tracing, several plans have leveraged their technical capabilities to advance public health surveillance and create infrastructure to guide re-openings, including developing data exchanges with local health departments to assist with epidemiological mapping and to support testing and contact tracing functions [32]. Second, some payers have contributed resources and logistical expertise to support the planning and distribution of medical supplies, such as PPE [33,34]. Third, some payers have collaborated with the biopharmaceutical industry to support data sharing and evidence generation for the development of COVID-19 medical countermeasures, such as partnering to increase access to monoclonal antibodies and using claims data to identify high-risk populations for enrollment in COVID-19 vaccine trials [35,36]. Fourth, following the authorization of the first COVID-19 vaccines, some payers have played an active role in supporting immunization campaigns in their local markets, including helping to coordinate distribution and using claims data to support post-market safety surveillance [37].

Addressing Systemic Health Inequities

COVID-19 both exposed and exacerbated existing disparities in health outcomes, particularly along racial and ethnic lines. Consequently, several payers took action to address the pandemic’s disparate impact. Some plans made resource and financial commitments during the pandemic to support the communities that were bearing a disproportionate burden of COVID-19 infections. Payer actions to address patients’ medical needs (e.g., by increasing access to health services for chronic disease management), social needs (e.g., coordinating supportive housing, meals), and COVID-19-specific needs (e.g., PPE distribution, testing) sought to address the environmental challenges contributing to health disparities where possible.

However, payers also recognized that meaningfully addressing health disparities and structural racism will require long-term, systemic action. Consequently, many plans adopted commitments to equity intended to extend beyond the pandemic, with some payers already beginning to initiate partnerships with providers oriented around health equity (e.g., Blue Cross Blue Shield of Illinois’ Health Equity Hospital Quality Incentive Pilot Program) [38].

Regulatory Tailwinds: Federal Actions and Payer Responses

Transformative Flexibilities for Payment and Care Delivery

Unprecedented regulatory flexibilities and guidance from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and CMS coupled with statutory mandates and resources from COVID-19 relief legislation generated momentum across payers to promote alignment in policy (e.g., coverage for COVID-19 care) and drive pivots in clinical practice (e.g., expansion of telehealth) to reduce barriers to accessing critical health care services during the pandemic.

For example, with shelter-in-place orders shuttering the doors of many outpatient health care facilities, CMS granted waivers for telehealth to expand access to patients while minimizing risk of exposure to COVID-19. When implementing flexibilities for telehealth, CMS worked with the Office of Civil Rights within HHS to enable the use of popular video-enabled mobile applications (e.g., FaceTime, Skype), which were not originally designed to be compliant with the standards set forth in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Other key flexibilities include the temporary relaxation of many site-of-care restrictions on health care delivery, from CMS’s “Hospital Without Walls” program to a commitment to reimburse services relocated to off-campus sites at traditional outpatient prospective payment rates [39]. Beyond federal action, many state insurance commissioners and Medicaid programs also introduced new flexibilities and requirements for commercial health plans (e.g., requiring waivers of cost-sharing, requiring guarantees of network adequacy) [40]. Additionally, special enrollment periods for state-based (in 2020) and federal (in 2021) insurance marketplaces enabled plans to expand access to health insurance for individuals who may have lost coverage during the pandemic [41].

Health Plan Responses

New federal and state mandates, rules, waivers, and guidance supported a rapid transformation in the health care payment and delivery landscape. In some cases, commercial payers changed their policies due to new requirements imposed by legislation and federal and state regulatory action. For example, the Families First Coronavirus Response Act and Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act required all payers in the U.S. to cover the cost of COVID-19 diagnostic testing without cost-sharing. Likewise, states across the country directed health plans to expand access to virtual care, including eliminating originating site requirements and reimbursing telehealth visits at parity with in-person visits.

In addition to complying with regulatory requirements, some payers took further action. In some cases, commercial insurers implemented changes in health plan design that regulators recommended, but did not require. For example, several Medicare Advantage organizations waived cost-sharing for both COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 care for the duration of the pandemic, actions that CMS had encouraged but not required [42]. Many payers also temporarily waived prior authorization requirements with varying degrees of specificity, from indication-specific authorizations (e.g., behavioral health) to facility-level policies (e.g., transfers to post-acute care) [9]. In other cases, payers leveraged the momentum of new state and federal flexibilities to introduce changes with broader scope. For example, while Medicare’s March 2020 policies for telehealth are set to expire at the conclusion of the public health emergency, select commercial insurers independently announced in 2020 that their plans would permanently extend coverage of telehealth services [43]. Likewise, although Medicare’s advance payment program concluded in April 2020, several commercial insurers continued their provider refinancing and stimulus initiatives, and designed these programs to serve as on-ramps for practices to transition into alternative payment models (APMs) after the public health emergency [44].

The concerted actions of payers across the country may have played a key role in supporting the dramatic increase in the uptake of and appetite for telehealth in the U.S. One analysis found private health care claims for telehealth services increased from 0.15% in April 2019 to 13% in April 2020, a more than 8,000% increase [45]. Additionally, CMS reported that the weekly number of beneficiaries in FFS Medicare receiving telehealth services increased from 13,000 to nearly 1.7 million during the pandemic [46]. While the increased utilization of telehealth has not completely offset the decrease in in-person visits, and levels of telehealth use have declined significantly as the U.S. begins to remove physical distancing restrictions, nationwide telehealth usage still substantially exceeds pre-pandemic levels, particularly among large provider organizations (≥6 clinicians) and within select specialties (e.g., behavioral health, endocrinology) [47,48]. Although the key driver of utilization growth was the realignment of financial incentives, many payers also made process and operational changes to support patient access to services and increase provider comfort with virtual care modalities. These strategies spanned member outreach initiatives, streamlined billing processes, and coverage for and integration of new digital health products, as summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2. Payer Strategies to Support the Transition to Virtual Care.

| Focus Area | Payer Strategies |

|---|---|

| Patient Barriers to Access |

|

| Provider Barriers to Access |

|

| Expanding Service Offerings |

|

| Expanding Delivery Capacity |

|

| Integrating Digital Health Tools |

|

Regulators and industry experts reflecting on the scope of the payer sector’s COVID-19 activities described above have posited that the magnitude and duration of the pandemic have generated an impetus to drive lasting sector-wide change [49]. However, many pandemic-era policy flexibilities and operational changes are set to officially expire at the conclusion of the public health emergency, and the current lack of comprehensive policy proposals for long-term extension, coupled with the historical inertia of the health care system, present roadblocks to durable change. To truly achieve a “new normal,” payers will need to make forward-looking decisions that build upon pandemic-era innovations in plan design (e.g., telehealth coverage, utilization controls), while policymakers will need to develop regulatory and legislative solutions that apply the momentum from COVID-19 to accelerate progress for pre-pandemic goals (e.g., transition to value). The next section outlines the challenges that payers will have to address to achieve these goals, including navigating the financial aftershocks of the pandemic and managing evolving stakeholder expectations about plan policies.

Key Pandemic-Era Challenges for Payers

Although the pandemic accelerated long overdue changes to payment and delivery, the destabilizing nature of the public health emergency has also exposed systemic challenges and vulnerabilities for payers, and the sustainability of payment and care changes implemented in the public health emergency is not yet clear. Health plans will need to navigate an uncertain market while adjusting to the new expectations of patients, providers, and employers, whose behaviors and incentives have shifted markedly after COVID-19 upended numerous health care norms.

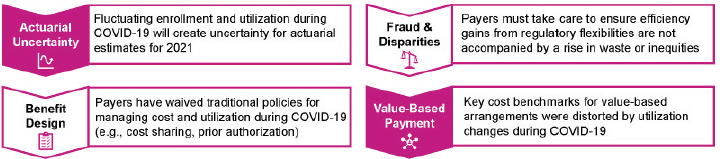

This section outlines the key short- and long-term challenges for payers in the post-pandemic era, including:

-

1.

Navigating the actuarial uncertainty resulting from the uncertainty of enrollment;

-

2.

Managing evolving expectations for benefit design (e.g., cost-sharing, prior authorization);

-

3.

Monitoring the risk of fraud and disparities arising from new regulatory flexibilities; and

-

4.

Evaluating implications of COVID-19 for rate setting and risk adjustment in value-based programs (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 3. Key Challenges for Payers for the Post-Pandemic Era.

Uncertainty in Health Insurance Coverage

At its core, a viable insurance business requires accurate actuarial estimates of risk. In order to set premiums and service prices, payers need to predict what enrollment will be, which products their clients and patients will choose, what the levels of service use will be, and how regulatory changes may affect their operations. Notably, this forecasting must occur well in advance of marketing for the following year. The COVID-19 pandemic introduces significant new uncertainties into each of those parameters.

Consider first the challenges of enrollment. Due to the prominence of employer-sponsored insurance in the U.S., rates of health care coverage are a likely casualty of the pandemic-induced economic recession. Analyses suggest nearly three million Americans lost employer-sponsored health insurance between March and September 2020, with losses disproportionately affecting Latinx individuals [50]. While the post-pandemic implications for U.S. payers will differ significantly from the aftermath of previous economic recessions due to the presence of the Affordable Care Act (ACA)—with the exchange and Medicaid expansion increasing options for coverage—many Americans may still struggle to afford the cost of health insurance, especially given that coverage losses were more likely to affect low-wage workers. Payers experiencing significant shifts in enrollment from commercial to Medicaid and ACA exchange products must attempt to predict how those trends will shift. Forecasting churn has been especially challenging given that compensatory Medicaid enrollment during the pandemic recession has been lagging thus far, and the magnitude and rate of change will continue to evolve in tandem with economic and pandemic-related developments [51].

Furthermore, while health care utilization has rebounded substantially since the early days of the pandemic, the recovery has been uneven across specialties, and many providers continue to face financial uncertainty. As of October 2020, outpatient volumes had recovered from a nadir of 58% to be on par with normal levels of utilization [48]. However, the recovery is heterogeneous; for example, weekly visits exceed pre-pandemic levels for specialties such as dermatology (+17%) and adult primary care (+13%), but remain below baseline levels for specialties such as pulmonology (-20%) and behavioral health (-14%). At the inpatient level, overall volumes still remain below pre-pandemic utilization rates, with medical service lines (e.g., cardiology, nephrology) recovering more quickly than surgical service lines (e.g., orthopedic surgery, general surgery) [52]. Financial stability remains a concern for many providers, particularly primary care physicians, of whom one-third report volumes more than 30% below pre-pandemic levels and a quarter report pandemic relief to have run dry as of September 2020 [53].

While many aspects of utilization have returned toward pre-pandemic levels, employers nonetheless anticipate pent-up demand to increase medical costs in 2021. Insurers have cited additional potential for both upward (e.g., from COVID-19 testing) and downward (e.g., from avoided care) pressures on spending [27,28]). To be clear, health insurers generally remained profitable during 2020, and will likely be required to provide substantial rebates to members and the government due to regulatory requirements for medical loss ratios [27]. Several states also established risk-sharing corridors in 2020, and CMS issued new guidance in December 2020 to clarify health plans’ obligations for rebates based on pandemic-induced changes in medical loss ratios [29]. However, continued spikes in caseloads and unpredictability in utilization does create challenges for health plans. For example, the increase in COVID-19 cases and costs in the fourth quarter of 2020 led to substantial declines in operating income for several major health plans, illustrating the volatility of the pandemic [54,55].

The potential for additional waves of infection in 2021 adds further uncertainty to efforts to estimate enrollment and calculate premiums. For example, insurers have reported that pandemic-induced declines in utilization—and the subsequent changes in risk code selection—create challenges for health plans to accurately price their services [56]. Likewise, the severity of subsequent cases and the advent of new treatments (e.g., antibody therapies) and vaccines (e.g., vaccine administration costs) for COVID-19 will affect cost forecasts for payers. Furthermore, new public health restrictions may create new delays in non-COVID-19 care delivery while also exacerbating existing health burdens (e.g., chronic disease management, mental health), creating further uncertainty for payers in the future. Lastly, even employer clients who did not implement layoffs may feel pressure to change their benefit structures and place even more cost-sharing on employees, which in turn could have short- and intermediate-range effects on care-seeking behavior and outcomes such as complications from delayed treatment. Payers will therefore face much greater uncertainty in their actuarial estimates for 2021 than they are accustomed to.

Evolution of Benefit Design

Payers will have to reconsider whether and how to adapt their benefit structures and care management approaches to ensure sufficient access to high-value care for patients. Some key areas of focus are detailed below:

Cost-Sharing

Prior to the pandemic, the benefit structure of commercial health insurance had evolved toward greater patient cost-sharing, with average deductibles quadrupling between 2006 and 2017 [57]. As noted above, delayed medical care in 2020 due to COVID-19 may incentivize employers to favor greater cost-sharing to control elevated medical costs in 2021. However, cost-sharing today—which by law, excludes COVID-19 testing and treatment—may already present untenable barriers to routine management of chronic diseases or acute care, especially when layered on top of the fear and logistical challenges of obtaining in-person services during a pandemic. Suspicions of reduced emergency department visits and hospitalizations for patients with strokes or myocardial infarctions, and higher-than-expected numbers of home deaths during COVID-19, reinforce this concern [58,59].

During the pandemic, many payers introduced waivers for cost-sharing—primarily within Medicare Advantage—with some payers eliminating all cost-sharing for primary care and behavioral health services in this population. Health plans will need to evaluate the appropriateness of either allowing these policies to expire or extending them beyond COVID-19. Furthermore, the presence of indication-specific cost-sharing waivers (e.g., for COVID-19) raises the question of whether similar policies should be adapted for other diseases, especially given that smart medical management in the era of chronic illness requires strategies focused on increasing access to specific services rather than creating barriers to utilization. For example, over 34 million Americans have diabetes, yet many health plans have cost-sharing policies for diabetes medications, with such policies associated with reductions in medication adherence [60,61]. While cost-sharing may be a useful tool for curbing the utilization of low-value services, the COVID-19 experience should prompt payers to reconsider the appropriateness of such policies across different clinical indications, with the principles of value-based insurance design providing an avenue to promote better outcomes while also addressing disparities in care [62,63].

Prior Authorization

Insurers’ usual focus in care management has been to reduce utilization by requiring providers to receive preapproval before being reimbursed for health services, a process known as prior authorization. During the pandemic, many insurers reduced or waived prior authorization requirements for different aspects of COVID-19 care, including durable medical equipment (e.g., respiratory services), diagnostic testing, patient transfers, and inpatient or emergency medical care [64]. A key question for payers is whether they will extend such flexibilities to non-COVID-19 indications. Administrative expenses for prior authorization have been estimated in the billions, and critics claim that the existing process places undue financial liability on patients [65,66]. Physician groups have urged for simplification of prior authorization processes, including identifying supporting payment models (e.g., lower authorization burden under APMs), implementing procedures for automation, and developing criteria for use to minimize provider burden [67].

Guardrails for Oversight

During the pandemic, many payers made time-limited commitments to paying for telehealth at rates equivalent to in-person visits. While trends in adoption vary across populations and specialties, supporting the long-term uptake of telehealth services will require health plans to develop policies and payment strategies to support this transition in care delivery.

First, it will be important for payers to ensure that reimbursement policies account for the spectrum of telehealth services. Telehealth encompasses both audio and video services, and virtual care can also include integration with digital health products and remote patient monitoring services. Different care platforms have distinct advantages and limitations, and health plan policies will need to account for the value of different use cases, including frameworks for adjudicating when virtual care is and is not a medically appropriate substitute or complement to in-person care [68]. Plans will also need to invest in data collection and intervention evaluation, given that rigorous evidence on telehealth’s capacity to effectuate cost reductions and outcomes improvements remains nascent.

Second, as virtual care becomes a permanent feature of care delivery, payers will need to equip themselves to evaluate the risk for fraud and abuse. For example, a 2019 federal investigation revealed how a scheme defrauded the Medicare program of $1.2 billion by using telehealth to inappropriately prescribe medical equipment [69]. The Office of the Inspector General within HHS identified an additional $4.5 billion in so-called “telefraud” schemes during its September 2020 report [70]. Clarifying the need for and scope of guardrails will require payers to perform audits and other analyses of services rendered during the pandemic. For example, payers may not have had time to build in claims edits to disallow services like chemotherapy or diagnostic imaging to be billed under “telehealth.” Consequently, mechanisms for appropriate oversight will be necessary to ensure that telehealth does not replicate the existing challenges of waste within the health care system. One avenue for developing guardrails without replicating the administrative burdens associated with in-person care would be to leverage alternative payment models, as population-based financing strategies can naturally disincentivize against the unnecessary utilization of both in-person and virtual services.

Third, considerations of telehealth’s efficiency should be paired with concerns about equity. Payers need to judge when and how shifts to virtual care may have exacerbated disparities in access and care quality. For example, video-based services may not be as accessible for rural communities with limited access to high-speed internet, or among low-income households where multiple family patients might be relying on a single device for remote work or learning. In these instances, payers could improve outcomes by helping providers ensure a safe, rapid return to in-person services, such as through direct outreach to affected patients or incentives for providers to prioritize specific cases.

From a regulatory perspective, many states issued waivers of scope-of-practice laws and credentialing requirements during the pandemic to allow providers licensed in one state to provide telehealth services to patients in another state to accommodate demand for virtual care during the public health emergency. Payers will need to monitor the extension or expiration of these waivers, which in turn may affect network development for telehealth. It is possible that patients and providers who are now accustomed to new modes of accessing and delivering care may react negatively if regulators and payers revert wholesale back to historical policies. Payers could seize the opportunity to leverage consumer sentiment and advocate for more and permanent reciprocal licensure agreements across states.

Securing the Future of Value-Based Payment

For the significant percentage of providers in value-based payment arrangements, payers will have to decide how to reconcile such contracts for time periods directly affected by COVID-19 and how to amend them for future years. Shifts in enrollment and visit patterns, whether in-person or virtual, could change the number and makeup of patients who are attributed to providers in value-based payment arrangements based on claims patterns. Arrangements with spending targets set as a percentage of medical loss ratios or prospectively set cost trends could result in providers receiving payouts from pandemic-related drops in utilization rather than through their own care management efforts. Even arrangements that rely on actual market-based cost trends could prove problematic for payers and providers, as it remains unknown whether COVID-19-driven changes in utilization were homogeneous across all providers in a given community.

Quality Measurement & Risk Adjustment

Because of lockdowns, the migration to digital care, and changes in care-seeking behavior, providers are justifiably anxious that quality measurement—a key component of many value-based payment arrangements—could yield distorted results for 2020. As a result, many payers have offered relief in quality scoring during the pandemic. For example, CMS will allow providers in the Medicare Shared Savings Program to pick the “better of” quality scores for 2020 or 2019 in quality scoring. This offers the benefit of preventing some providers from being unfairly penalized by COVID-19, but also carries the downside of limiting rewards to providers that did achieve meaningful performance improvements over the measurement period [71]. Nevertheless, payers will still need to work with measure stewards such as the National Committee for Quality Assurance to ensure that measure specifications will account for disruptive changes like the shift to telehealth. Furthermore, to the extent that spending performance and trends are risk-adjusted, payers and their risk adjustment vendors will need to consider not only variation in COVID-19 infection rates and treatment, but also variable changes in non-COVID-19 care as a result of the pandemic.

Securing Buy-In for Value

Payers were already collaborating with providers to move away from volume-based to value-based reimbursement prior to the pandemic, with over a third of all health care spending before COVID-19 occurring under APMs before COVID-19 [72]. With providers experiencing substantial financial and operational pressures during the pandemic, advocates exhorted payers to take actions ranging from offering advance payments to practices under FFS arrangements to relieving providers under value-based contracts from methodologic uncertainties and exposure to downside risk in the short term [26]. Calls for payers to take action were amplified after financial records indicated that prominent insurers registered medical loss ratios (MLRs) below 80% and also realized substantial profits during the second quarter of 2020 due to pandemic-induced declines in utilization [73,74,75]. While payers who meet government-determined criteria for MLRs will be required to provide consumers with rebates, the broader increase in gross margins per member per month (e.g., 35% increase in Medicare Advantage) spurred calls for health plans to increase their contributions to health system and public health needs [27,76].

Although the financial impacts of the pandemic (e.g., membership loss, cost-alleviation activities), actuarial uncertainty (e.g., about pent-up service demand), and obligations to clients (e.g., self-insured employers) may present challenges for payers, COVID-19 does create a unique value proposition for health insurers to accelerate the realignment of financial incentives to promote delivery system transformation. Proposed strategies have ranged from conditioning provider relief payments on investments in value-based capabilities and commitments to transitioning to APMs, which can include partial or fully capitated arrangements [77]. Existing value-based arrangements may also merit reconsideration, as many APMs are built on top of the chassis of FFS, and the current retrospective approach to reconciliation is unlikely to offer providers the necessary financial certainty given how revenue gaps have widened during the pandemic [78].

Payers will consequently face several challenges when securing buy-in for value. For one, commercial payers will need to make a defensible case to clients that continuing to pay per-member per-month fees for infrastructure and care coordination are worthwhile investments to not only continue but also significantly improve providers’ financial resiliency. Adding to this challenge is the long-term view required for payers and their clients to realize the returns on investments in APMs given evidence on the time period required for providers to successfully transition to risk-bearing arrangements [79].

Such decisions are but one example of how payers are “sandwiched” in multi-directional relationships with providers, regulators, and clients, creating challenges for the future of value-based payment across different plans and products. Payers offering Medicare Advantage plans will need to navigate how drops in utilization in traditional Medicare in 2020 (and likely 2021) will affect both future rate-setting and future CMS decisions to adjust pre-existing concerns around upcoding and risk adjustment. Payers covering employed populations will need to seek voluntary alignment in policies between self-insured employer clients and fully insured populations, and all payers will need to set payment policies with an aspiration of transparency so that providers can understand them, while also adhering to state or local mandates (e.g., for benefits, network adequacy).

Going forward, payers have important, stabilizing roles to play to ensure that patients get the care they need, high-value providers can survive and thrive, and clients feel confident that their health care investments are justified and appropriately spent. Payers will need to be creative and nimble in both responding to and anticipating COVID-19 challenges and avoiding unintended consequences.

Opportunities for Sector-Wide Performance Improvement

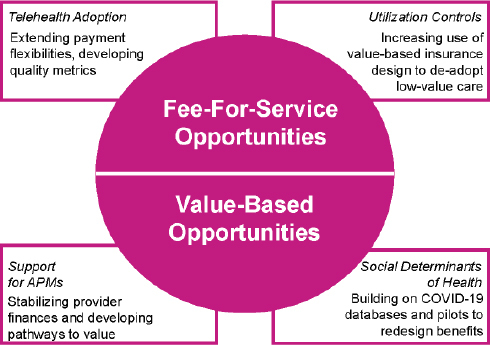

The COVID-19 pandemic required payers to engage with providers and policymakers to facilitate rapid transformation of care delivery during the pandemic. However, early trends of reversion to past behavior and the looming expiration of regulatory flexibilities pose challenges to the durability of these changes. Sustaining health system transformation beyond COVID-19 will require payers to intentionally pursue sector-wide performance improvement. Several of these opportunities will require the preservation of regulatory changes and the continuation of shifts in payment and practice patterns that have occurred during the pandemic. Others, such as revising APM designs or broadening the use cases for COVID-19 tools, will require further infrastructure investments. Notably, the mechanisms for sector-wide improvement will differ depending on the payment models that health insurers are using; for example, the prevalence of telehealth flexibilities prior to the pandemic was substantially higher among providers participating in APMs as compared to FFS [80]. Consequently, this section categorizes the key opportunities for sector-wide improvement along two domains: FFS opportunities (e.g., telehealth adoption, utilization controls) and value-based opportunities (e.g., APM growth, social determinants of health) (see Figure 4).

FIGURE 4. Opportunities for Sector-Wide Improvement.

FFS-Based Opportunities

Despite the growth in APMs over the past decade, the majority of physician office visits are still reimbursed under FFS, and the majority of APMs still rely on an FFS architecture [72,81]. While the pandemic has re-highlighted the instability of FFS and increased interest in APMs, which span bundled payments and partially and fully capitated arrangements, it is likely that FFS will still remain a prevalent approach to health care paymentfor the foreseeable future. However, payers can build on two key COVID-19 levers—telehealth flexibilities and utilization controls—to increase the value and convenience of care under FFS.

Telehealth Adoption

The adoption and proliferation of telehealth has been a silver lining success story of COVID-19. After CMS implemented payment parity for telehealth services, many commercial payers followed suit, in some cases extending payment parity for services across specialties. Most commercial payers eliminated all cost-sharing for telehealth care related to the diagnosis and management of COVID-19-related symptoms. Multiple payers also eliminated cost-sharing for all telehealth use (primary care, urgent care, behavioral health care) for the 2020 calendar year to reduce the chances of exposure, and many payers also announced payments for a broader set of telehealth services, many of which can now be billed by non-physician health care practitioners.

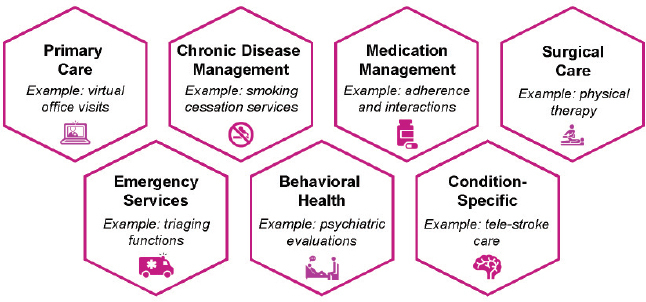

A recent survey of health care providers reported that almost half expected to use telehealth at the same or greater levels post-pandemic, a marked change compared to pre-2020 levels of utilization [82]. This is meaningful for several reasons. First, telehealth has important benefits for patients, such as convenience, continuity, affordability, and speed. This may improve access to care overall and, in particular, for services that require frequent “touches” or have traditionally experienced access challenges. For example, mental health services, including screening for conditions like depression, are one area where the benefits of telehealth may far outweigh the additional costs or tradeoffs between remote and in-person care. Examples of additional high-value use cases for telehealth are summarized in Figure 5. Second, the technology required to conduct telehealth visits has existed for years. The sector has overcome inertia generated by the lack of financial incentives and cultural resistance to change to achieve widespread adoption and use.

FIGURE 5. Select Examples of Clinical Use Cases for Telehealth.

Despite the benefits and uptake of telehealth during the pandemic, there remain several open questions. First, payers must work with health care providers and other stakeholders to learn how to best deploy telehealth at scale to those who need it most in a way that improves patient experience and outcomes. One area of focus is to use telehealth to bolster existing provider-patient relationships, rather than as a temporary substitute due to office closures. For example, incorporating telehealth into the continuum of surgical care (e.g., virtual options for pre- and post-operative visits) could improve access and efficiency. Successfully deploying telehealth as a means to enhance care continuity and coordination will require devising and tracking appropriate quality and experience metrics, some of which may have to be adapted for monitoring telehealth use rather than in-person visits specifically. In a related innovation proposal, the National Quality Forum has suggested a framework for telehealth quality measurement [120].

Second, payers must proactively work to address ways that technology-based care could exacerbate existing access gaps and racial, ethnic, socioeconomic, geographic, and other disparities in care. Nearly 20% of Americans still lack access to smartphones, including almost half of senior citizens [83]. Additionally, some communities continue to experience significant gaps in home-based internet access [84]. Payers will need to consider these gaps and barriers to patient engagement, including access to devices and hardware, comfort with technology, and levels of health literacy in order to design effective programs. This will likely require tailoring the design of telehealth programs to the specific needs of certain populations and will also likely require payers to invest directly in telehealth solutions rather than depend wholly on health care providers. The importance of payer investments may be particularly important for complex populations with multiple medical or interconnected social needs. Furthermore, payers may choose to provide more intensive support to providers serving safety net populations, such as federally qualified health centers.

Utilization Controls

As noted in the preceding section on “Key Pandemic-Era Challenges for Payers,” payers rapidly evolved their policies for cost-sharing and prior authorization to streamline access to care and facilitate rapid payments to providers during COVID-19.

The opportunity for payers moving forward lies in consolidating these efforts into a more systematic, strategic, and equitable approach to supporting patients to get high-value care and forego low-value care. In the case of prior authorization, the recent expansion of CMS’s Medicare Prior Authorization Model for Repetitive, Scheduled, Non-Emergent Ambulance Transport—which saved $650 million over four years—is an example of how payers can develop tailored strategies for utilization controls that reduce costs without compromising care quality and access [85]. Moving forward, payers will need to work with providers to achieve a convergence between pandemic-era pilots and standard process controls for health plans. A more expansive adoption of value-based insurance design principles could help payers appropriately redesign utilization controls such as cost-sharing to reduce waste in chronic disease management (e.g., for durable medical equipment selection) and increase the affordability of comparatively higher value services [86]. Previous work, including some under the auspices of the National Academy of Medicine, offers examples of low-value services—several of which experienced significant declines in utilization during the pandemic—that would be appropriate candidates for exclusion during benefit redesign [87,88]. Payer-provider partnerships may also accelerate progress, although this will likely require alignment vehicles like value-based payment models to engage providers. For example, payers and providers can collaborate to develop alternative care pathways to reduce low-value service utilization (e.g., for managing joint pain), and insurers can help support the development of high-value provider networks [89].

Value-Based Opportunities

Although FFS remains the dominant form of health care payment in the U.S., the expansion of APMs and resulting evidence of cost savings prior to COVID-19, coupled with increased interest in models such as capitation during the pandemic, creates a window for health insurers to accelerate the transition to value across the system. Payers can start by increasing their support for APM arrangements, and can frame payment reforms as an extension of pandemic-era efforts to stabilize provider finances [90]. Payers can also build on the investments in technical capabilities (e.g., risk stratification of populations, remote patient monitoring) and focus on non-medical needs from COVID-19 to design payment models capable of better addressing the social determinants of health.

Support for APMs

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the vulnerability of a FFS system—long seen as the “safe” status quo—to providers. Those providers who were prepaid for the populations they serve were better positioned to rapidly transform their practices to meet their patients’ needs and manage the financial uncertainties of the pandemic. For example, several fully capitated primary care practices were able to rapidly reorient their care models to focus on keeping patients safe at home while avoiding unnecessary hospital admissions [91,92]. To support these providers, some payers developed prepayment models to accelerate the transition to telehealth for primary care practices in their networks [93]. Furthermore, numerous plans offered relief payments, with particular focus on independent physician practices, to help providers bridge cash flow shortfalls during the public health emergency. The implications extend beyond primary care; for example, preliminary reports from Maryland and Pennsylvania highlight the value of APMs for hospital payments—so-called global budgets—during the pandemic [94,95,96].

These experiences have revived discussions about risk-based payment models nationwide and reinforced the importance of collaboration between public and private payers. To help existing value-based initiatives weather the pandemic, CMS made a number of changes to ongoing models including suspending or postponing them, giving participants greater flexibility in which metrics are assessed, and adjusting baselines and benchmarks [97]. Some commercial payers developed bridges from pandemic-era payment initiatives to value-based models for their providers. CMS also announced the Community Health Access and Rural Transformation (CHART) Model—which builds on the experience of the Accountable Care Organization (ACO) Investment Model—which will use advance payments to strengthen the resiliency of health financing for rural practices [98,99]. These initiatives are emblematic of efforts by many payers to forgive losses and continue paying prospective fees to support activities like care management to help providers maintain financial stability.

Investing in the Social Determinants of Health

Many payers developed new capabilities to understand the social context of their patients and accordingly manage their non-medical needs during COVID-19. These efforts included systematic screenings for social needs, the development of geographical maps to identify patients with needs related to the social determinants of health, and the direct provision of services. For example, Blue Shield of California developed a “Neighborhood Health Dashboard” that was used to create California’s Vulnerability Index to guide the deployment of services and resources for COVID-19 recovery [100,101]. Humana made well over one million proactive phone calls to its highest risk patients to assess social needs, layered those results on a national registry of results from over three million surveys about health-related social needs, and leveraged patient-level predictive models to assess risk of social isolation in the deployment of a nationwide basic needs team to deliver interventions addressing social context related to the pandemic. Payers also offered supplemental benefits during the pandemic, from Humana’s delivery of nearly one million meals to its patients to Bright Health’s coverage of non-emergency transportation.

These efforts illustrate the untapped potential for payers to implement systematic strategies to identify, measure, and address structural inequities surrounding access, quality, and outcomes. The challenge for payers will be transforming these one-off, pandemic-era pilots into coordinated efforts to make meaningful and sustainable progress on health disparities. APMs can provide a powerful vehicle for achieving these goals. Several models prior to the pandemic illustrate the feasibility and value of this approach for different domains in the payer sector, including North Carolina Medicaid’s Healthy Opportunities Pilots, the expansion of supplemental benefits under Medicare Advantage, and CMS’s Accountable Health Communities Model [102,103,104,105].

Moving forward, payers could use the data collected during COVID-19 to help inform the design and evaluation of supplemental benefits for Medicare Advantage. These benefits, which now include social support services, have had limited uptake by commercial insurers to date, with plans reporting evidence gaps and the complexities of decision-making as the key challenges [3]. Payers could also consider developing metrics and financial incentives that reward progress on disparities, and explore the feasibility of risk-adjustment for the social determinants of health [106,107].

Transformative Sector-Wide Policy, Regulatory, and Legal Changes

While the pandemic is still ongoing at the time of this paper’s publication, it is already evident that the adaptive responses to COVID-19 can offer a model for payers’ long-term transformation. However, it is important to acknowledge that the health system is biased towards inertia; indeed, early trends of reversions to past practices of payment and delivery coupled with the impending expiration of statutory authority for COVID-19 flexibilities create the risk that the system’s “new normal” will not meaningfully differ from the “old normal.” As described in the preceding section, payers will need to play an active role in driving durable, sector-wide change. These efforts must be paired with policy planning, regulatory guidance, and legislative changes to build on the temporary momentum for health care transformation generated by COVID-19 (Boxes 1-4) and also improve the payer sector’s preparedness for future public health emergencies (Boxes 5-6). Priority areas for consideration within those two domains include:

-

1.

Accelerating the transition to value-based payment;

-

2.

Extending flexibilities for virtual health services and capabilities;

-

3.

Rethinking benefit design using the principles of value-based insurance;

-

4.

Aligning incentives and investments to address health inequities;

-

5.

Creating mechanisms for collective action during public health emergencies; and

-

6.

Coordinating payment reforms with public health functions.

Accelerating the Transition to Value-Based Payment

The development of APMs over the past decade enabled the health care system to make meaningful progress towards the goal of better care at a lower cost. An implicit consequence of APMs—enhancing the financial resiliency of providers—took on explicit importance during the pandemic as COVID-19 exposed the longstanding vulnerabilities of a payment system grounded in FFS [90]. Delivering on this new impetus for payment reform requires policy guidance and regulatory action to accelerate the transition to value-based payment.

First, as recommended by a bipartisan group of former CMS Administrators, regulators could offer loan forgiveness for Medicare payments conditioned on a commitment from providers to transition from an FFS arrangement to an APM in the near future, with APMs ideally exhibiting the characteristics of Category 3B or Category 4 models as outlined by the Health Care Payment Learning & Action Group [108,109]. Commercial payers can complement such regulatory actions by creating pathways to value for providers in their own networks. These immediate steps can create a foundation for financial resiliency beyond the pandemic.

Second, as new providers enter APMs, regulators should consider how extending other COVID-19 flexibilities can smooth the transition. For example, in April 2020, CMS issued a waiver that provided site-of-care flexibilities for health services traditionally delivered in hospital outpatient departments. Regulators could consider incorporating elements of the waiver into existing (e.g., Oncology Care Model) and new (e.g., Hospital at Home) payment and delivery models focused on specialty care [110]. Likewise, using APMs as the vehicle to extend COVID-19 flexibilities for telehealth (e.g., via the “meaningful use” provisions suggested above) could enhance care coordination and mitigate the risk of unnecessary utilization.

Third, regulators should consider how to create pathways to value for providers for whom APMs are not currently available. For example, specialists’ participation in APMs is generally lower due to the lack of condition-specific payment models. In the interim, CMS could encourage such providers to participate in evidence-based care transformation programs while regulators work to develop appropriate new APMs [111]. Likewise, safety net providers have struggled under value-based arrangements such as the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS), and are underrepresented in several demonstration models [112,113]. A truly resilient system of health care financing should incorporate the principles of equity-focused design [114]. Using the experience of Maryland and Pennsylvania, CMS could work with states to explore opportunities to develop new multi-payer APMs inclusive of all types of practices within defined geographies.

Fourth, APMs provide a framework for payers and providers to sustain pandemic-induced efficiency improvements to care delivery. Strategies to increase access to care during COVID-19 (e.g., by virtualizing components of the patient journey where clinically appropriate) can be broadened to new use cases after the pandemic and promote leaner and more convenient models of care. However, achieving long-term reductions in operating costs will require realigning financial incentives to support changes in site-of-service and resource utilization. For example, Hospital at Home models can improve care convenience and health outcomes, as well as free up inpatient capacity, and new regulatory flexibilities have supported their growth during the pandemic [115]. Developing APMs such as a bundled payment for a defined episode of care can offer payers and providers an avenue for scaling Hospital at Home beyond COVID-19 that promotes both resource efficiency and accountability for outcomes [116].

Lastly, payers should use the framework of value-based payment to operationalize the additional priority actions for the sector outlined in this section. For example, APMs can offer payers and providers the necessary flexibility to support care delivery models that blend together in-person visits, virtual platforms, and alternative care sites. Likewise, APMs such as capitated models can provide a framework for payers to redefine benefit categories to better meet patient needs while disincentivizing the utilization of low-value care. Furthermore, APMs can help foster accountability for health equity by realigning financial incentives to focus provider investments and accountability for addressing health disparities.

Priority areas for accelerating the transition to value-based payment are summarized in Box 1.

BOX 1. Considerations for Accelerating the Transition to Value-Based Payment.

Leverage pandemic-era initiatives to stabilize provider finances to create new pathways encouraging providers to enter into APMs

Use APMs as a vehicle for scaling site-of-service flexibilities beyond COVID-19

Broaden the accessibility of value-based payment programs for all provider types, with a focus on embedding accountability for health equity into APM design

Extending Flexibilities for Virtual Health Services and Capabilities

A lasting legacy of the COVID-19 pandemic will be the substantial expansion of virtual health services and capabilities in the American health care system. These capabilities include modality changes for patient encounters (e.g., audio or video-enabled telehealth services) and new tools for supporting remote patient monitoring and chronic disease management (e.g., different types of digital health products).

For example, the utilization of telehealth expanded substantially in 2020 compared to 2019, with the percentage of physician office visits conducted via telehealth reaching a peak of nearly 14% in April 2020 before approaching a temporary equilibrium at approximately 6% as of October 2020 [48]. Utilization growth was enabled by Medicare waivers and state insurance department mandates to reimburse virtual service delivery at parity with in-person care, with broad discretion across provider types (e.g., physician, nurse) and virtual platforms (e.g., Zoom, FaceTime) [117]. These flexibilities have significant implications for improving the accessibility and convenience of care across the spectrum of care delivery, and the response of providers and patients during the pandemic coupled with new partnerships across sectors to diversify, integrate, and scale virtual models suggest that telehealth will continue to be a growing component of care delivery. However, the scientific literature still lacks a rigorous evidence base demonstrating the comparative cost-effectiveness of virtual care delivery platforms—a gap that payers will need to help fill by drawing from data generated during COVID-19 and developing infrastructure for future evaluations.

Consequently, while regulators should certainly extend reimbursement flexibilities for platforms where the evidence demonstrates improvements in care delivery, payers must take proactive steps to ensure that the virtualization of health services is not accompanied by the replication (and potential exacerbation) of existing cost centers. A key consideration is that COVID-19 telehealth flexibilities were rooted in the construct of FFS, rendering temporary payment policies susceptible to the same long-term inefficiencies in the payer sector (e.g., siloed delivery, wasteful spending from unnecessary utilization) [118]. Once the risk of COVID-19 is attenuated and in-person office visits are safe to resume, payers will need to develop reimbursement policies that treat telehealth as a component of coordinated care rather than an isolated substitute. Regulators could approach this challenge by using APMs as the vehicle for developing telehealth flexibilities after the conclusion of the public health emergency, from episode-based arrangements for telehealth use in condition-specific settings (e.g., tele-stroke) to fully-capitated arrangements to integrate telehealth into the care continuum (e.g., Direct Contracting).

First, deploying telehealth under risk-based payment arrangements could provide clarity and consistency to providers about reimbursement while supporting the optimal use of telehealth within integrated care models. Indeed, HHS has noted that previous telehealth proposals submitted to the Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee “expressed skepticism that a FFS model would be able to provide enough incentive for providers to invest in innovating to explore how to employ telehealth optimally” [82].

Second, population-based payments by design have built-in disincentives against unnecessary use and provide a natural vehicle to measure care quality, enabling payers to rigorously analyze the capacity of telehealth to enhance the patient experience and clinical quality in different care settings. For example, the Medicare program could consider incorporating “meaningful use” policies for telemedicine use into participation requirements for APMs [119]. Likewise, both public and private payers could collaborate to develop new quality measures for telehealth using the National Quality Forum’s framework [120].

The appropriate continuation of CMS’s telehealth expansion policies from the pandemic will require additional guidance and resources. For example, the evolution of telehealth from a standalone service to an integrated component of care delivery will require virtual care platforms to be embedded into electronic health records. Regulators will need to ensure that recent interoperability rules, with their provisions on standardized infrastructure for application programming interfaces, provide sufficient guidance for payers and developers [121]. Likewise, while many providers began using telehealth during the pandemic, formalizing virtual services into everyday care planning beyond the pandemic will require practices to make long-term investments in information technology infrastructure and workforce development. Financial support from payers may help practices, particularly those operating in safety net environments or rural geographies, to develop the competencies needed for effective telehealth implementation, as was the case for the ACO Investment Model [98]. Furthermore, payers, providers, and policymakers will also need to collaborate to ensure that virtual care platforms do not recreate the inequities of existing delivery models. This will require addressing challenges ranging from lower accessibility to and uptake of different types of telehealth services among specific populations, tailoring virtual services to patients’ social context (e.g., optimizing language interpreter services for telehealth), and investing in infrastructure for measurement to support the identification of disparities in access and quality for racial and ethnic minorities and individuals of lower socioeconomic status [122].

Key considerations for extending flexibilities for virtual health services and capabilities are presented in Box 2.

BOX 2. Considerations for Extending Flexibilities for Virtual Health Services and Capabilities.

Leverage APMs as the vehicle for extending COVID-19 flexibilities for telehealth utilization and reimbursement

Collaborate with providers and regulators to develop sector-wide standards for care quality and clinical appropriateness of virtual health services

Dedicate resources to addressing potential inequities in patient access and the quality of virtual care

Rethinking Benefit Design Using the Lens of Value-Based Insurance

At the beginning of the pandemic, 68% of Americans reported that health care costs would be a factor when seeking care for COVID-19 [123]. Consequently, cost-sharing waivers—both those promulgated by COVID-19 relief legislation and implemented voluntarily for an expanded set of services (e.g., telehealth, behavioral health)—have been critical for expanding access to health services during the pandemic.

However, cost-sharing has long been a deterrent to care-seeking in the U.S. 33% of Americans delayed care due to cost in 2019, a trend that is likely to continue given that premiums and deductibles have outpaced the growth in median household income for the past 18 years [124,125]. Experiments dating back nearly 40 years illustrate how blunt utilization controls can negatively affect patient health, particularly through disruptions in chronic disease management [126]. In the case of prescription drugs, recent research on Medicare Part D illustrates how increases in out-of-pocket prices for life-saving medicines can reduce consumption and increase mortality [127]. Yet, importantly, research demonstrates that plans can minimize these effects without increasing expenditures by leveraging the principles of value-based insurance design and offering pre-deductible coverage of key services [128,129]. Such strategies will be increasingly salient for payers given the emerging evidence of negative health outcomes for patients during the pandemic due to interruptions in care continuity for non-COVID-19 indications [130].

This literature, coupled with the experience from COVID-19, illustrates how payers can achieve the twin goals of expanding patient access to care (by waiving cost-sharing) while reducing unnecessary utilization and spending (through value-based insurance design). The synergies between these two principles should inform benefit design as payers evaluate whether to extend pandemic-era cost-sharing waivers. Regulatory change and legislative action could further support payers in their efforts to carve out low-value services and broaden access to necessary care. For example, the federal government expressed support for value-based insurance design in the Fiscal Year 2021 rule for health insurance plans offered on the ACA’s market exchanges [131]. Legislators also introduced bipartisan legislation prior to COVID-19 intended to broaden the definition of preventive care to include evidence-based health services for chronic disease management. Such a change would both build on the principles of the cost-sharing waivers introduced during the pandemic, and help to improve the affordability and accessibility of necessary care [132].

Priority actions for rethinking benefit design post-pandemic are summarized in Box 3.

BOX 3. Considerations for Rethinking Benefit Design Using the Lens of Value-Based Insurance.

Adjust cost-sharing policies for chronic disease management using the principles of value-based insurance design

Advance regulatory support for value-based insurance design to streamline patient access to evidence-based strategies for chronic disease management

Evaluate evidence on utilization trends during the pandemic to support the deadoption of low-value health services

Aligning Incentives and Investments to Address Health Inequities

COVID-19 has laid bare the stark and longstanding disparities in population health in the U.S., with the virus disproportionately affecting communities of color and low-income populations. While payers have made commitments to addressing disparities and taken action to address patients’ social needs during the pandemic, long-term action across the sector will be needed to support meaningful progress for health equity.

First and foremost, payers should approach each of the priority actions outlined in this section using the lens of health equity. For example, when working to accelerate the transition to value-based payment post-pandemic, payers and regulators should incorporate lessons from recent evidence pointing to disparities within existing models [133]. Likewise, when extending telehealth flexibilities, payers and policymakers should take proactive steps to ensure equitable access to new care modalities.