January 21, 2020

Eleanora Fricke was born on June 10, 2010, with a rare chromosomal anomaly. She had severe cardiac malformations, including multiple large ventricular septal defects and severe pulmonic stenosis. She also had structural and functional malformations in her digestive, respiratory, renal, and muscular systems. Given her low birth weight (3.163 lbs) and multisystem disease, Eleanora required intensive 24-hour care, which only her parents were able to provide. On October 29, 2010, after 140 days of life, Eleanora died from congestive heart failure.

Joshua Helfand was born on May 11, 1991. At 6 weeks old, he experienced his first seizure, the earliest manifestation of a condition called infantile spasm. His seizures increased exponentially and were not controlled by standard or experimental medications. Given his seizures, his parents stayed with him every night to make sure he did not choke or injure himself. By the time of his death, on January 29, 1994, Joshua had survived two respiratory arrests, one cardiac arrest, and hundreds of grand mal seizures per day.

As we, the authors of this paper, watched our children fight for their lives, then die, we were left thunderstruck. Our own health was compromised, and our emotional well-being was challenged. We needed help. The only available options were to go to a support group or a therapist, who we had to search for, identify, and connect with on our own. Our starkly similar experiences were 16 years apart. The intervening years offered no major advances in bereavement care, no innovative support programs to cope with the aftermath of the passing of a child, and no legal protections for bereaved parents.

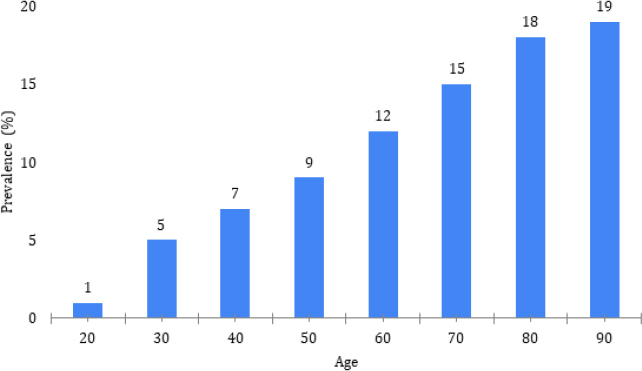

The death of a child, at any age, is considered to be one of the most—if not the most—stressful life events a person can go through. This experience is shared across cultures and continents, and the stress is enduring [1]. In the United States, the prevalence of child death increases with parental age, with 5 percent of parents experiencing bereavement by age 30, 12 percent by age 60, and 18 percent by age 80 (see Figure 1). Striking racial disparities exist in this area. The rates of bereavement for black Americans (compared to their white peers) are three times higher by age 30 and four times higher by age 80 [2].

Figure 1. Prevalence of Child Loss by Parent Age.

SOURCE: Umberson, “Race and Death of a Child,” University of Texas at Austin. Reprinted with permission.

Bereavement is associated with severe health, social, and economic consequences. Bereaved parents experience increased rates of depression, anxiety, mental health disorders, death by suicide, psychiatric hospitalization, substance abuse, cardiovascular disease, and immune dysfunction, as well as a substantially heightened risk of premature death [1,3]. Studies have documented both short- and long-term socioeconomic effects, including increased rates of marital disruption, losses in productivity and income, and increased rates of early exit from the workforce. Moreover, the impact of the child’s death often persists for decades after the loss [3].

Bereavement care in the United States is broken. The lack of consistent, high-quality bereavement care for Americans constitutes an invisible public health crisis. School shootings and mass casualty incidents involving children capture public attention and inspire action. Donations flow in to help the bereaved in the short term. Yet, children are dying every day from suicide, overdose, gun violence, war, motor vehicle accidents, cancer, and other chronic diseases—without fanfare and largely without systematic support for survivors. Moreover, no public policies exist to prevent the substantial downstream complications.

Notably, policy protections such as the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) do not recognize a child’s death as an eligible event for parental leave. Two bereaved fathers, Kelly Farley and Barry Kluger, have spent a decade working to change FMLA, without success. In most states, no legal protections for employment exist for bereaved parents. Such protections would allow parents to take leave following a child’s death. Many employers offer three to four days of paid bereavement leave. However, other time off is unpaid, and a return to work is not guaranteed.

In addition, secondary victimization compounds the grief and devastation of child death. Law enforcement or health care professionals may not prioritize providing appropriately compassionate communication in crisis situations. Families of children who die by suicide may be asked by 9-1-1 emergency services to cut down their hanged children, or parents may become the initial focus of an investigation. Families of homicide victims may be sent the bill for ambulance transportation of the dead body. A child protective services agency may investigate a family for months, even after the medical examiner finds no evidence of wrongdoing.

In cases of sudden unexpected infant death syndrome (SUIDS), families will often be at the center of the investigation and, within hours of the loss, may be asked to reenact the death with an infant doll. In fact, a US Department of Justice manual advises investigators as follows: “You may not know if you are dealing with a caretaker who has lost a child to [SUIDS] or one who actually murdered the child” [4]. For pregnancy losses, fetal remains are sometimes misplaced, disposed of by the hospital, or otherwise not provided to the family for burial. All these actions may compound the trauma of the family and heighten the risk of maladaptive coping and long-term stress.

First responders who interface with these families also need more support. Suicide rates among physicians, nurses, police, firefighters, and other first responders are higher than those of the general population. These providers receive extensive training in saving lives in an efficient and professional manner, but there are few resources for more sensitive and difficult duties, such as providing compassionate death notifications. There are few guidelines for providers or hospitals to follow in the event of a child death, and those that do exist often focus on the clinical aspects of death (e.g., counseling for genetic testing or autopsy). They do not address the emotional aspects of loss or the important health and self-care needs that might mitigate adverse health outcomes in the bereaved.

Approaches to Address the Bereavement Crisis

Much can be done to address this crisis. Research funding should be provided to support the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health in conducting epidemiological studies to better understand the prevalence and outcomes of bereavement. Support should also be given to these agencies to advance evidence-based approaches to mitigate the adverse short- and long-term outcomes of coping with bereavement.

Consensus reports and guidelines are greatly needed to drive policy changes at the federal, state, and local levels. Policy and procedural changes to advance the knowledge and training of first responders and other professionals who interface with families during child death are essential. They should include instructions on providing compassionate death notification in a law enforcement or health care setting; providing a compassionate transition for a family from a rescue scene to a crime scene with impending investigation; careful tracking of remains in hospitals and morgues; raising the possibility of organ donation and facilitating that process, which can be lifesaving for other children; and providing programs to train first responders in how to reduce secondary trauma in the bereaved.

To preserve the health and well-being of families, priority must be given to establishing support programs tailored to specific causes of death, ages of death, geographies, and cultural factors. Consideration of the individual circumstances is essential. For example, losing a child to stillbirth has different ramifications than those that accompany losing a child to suicide, overdose, or chronic illness. Effective programs would provide pragmatic support for the emotional, health, financial, and legal issues that bereaved families face.

Bereavement will touch every American at some point in life. It cuts across generations and communities. Together, we can stand for ourselves, our friends, our neighbors, and our communities to learn how we can support the well-being of all families. We believe our nation can, and should, do better to care for those who have experienced the profound loss of a child.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge that we are both bereaved parents and we are part of a social movement seeking to build the most advanced bereavement care system in the world. We dedicate this work to our children and to bereaved parents everywhere.

Funding Statement

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily of the authors’ organizations, the National Academy of Medicine (NAM), or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies). The paper is intended to help inform and stimulate discussion. It is not a report of the NAM or the National Academies.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-Interest Disclosures: None disclosed.

Contributor Information

Joyal Mulheron, Evermore.

Sharon K. Inouye, Harvard Medical School and Hebrew SeniorLife.

References

- 1.Li J, Laursen T, Precht D, Olsen J, Mortensen P. Hospitalization for mental illness among parents after the death of a child. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;352:1190–1196. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Umberson D, Olson J, Crosnoe R, Liu H, Pudrovska T, Donnelly R. Death of family members as an overlooked source of racial disadvantage in the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2017;114:915–920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605599114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rogers C, Floyd F, Seltzer M, Greenberg J, Hong J. Long-term effects of the death of a child on a parents’ adjustment in midlife. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:203–211. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walsh B. Investigating child fatalities: Portable guides to investigating child abuse. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs; 2005. (NCJ 209764). [Google Scholar]