August 26, 2019

This case study is part of a series from the National Academy of Medicine’s Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience. To read additional case studies, please visit: nam.edu/clinicianwellbeing/case-studies.

Background

Clinician burnout has become a pervasive issue [1] for U.S. clinicians, students, and trainees. Burnout, a syndrome characterized by a high degree of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, and a low sense of personal accomplishment from work, is cause for concern in the health care field because it can affect quality, safety, and health care system performance. Clinician burnout is largely a result of external factors outside of the control of an individual clinician. This includes regulations, incentives, policies, culture, stigma and more.

The purpose of this case study is to provide readers with tangible information to understand how The Ohio State University (Ohio State) has adopted programs and policies that support well-being. This case study is not a prescriptive roadmap. Rather, the authors hope that this case study will serve as an idea-generating resource for leaders working to improve the well-being of our nation’s clinicians, trainees, and students. This case study provides an overview of well-being initiatives at Ohio State’s College of Medicine, College of Nursing, Emergency Medicine Residency Program, and the Wexner Medical Center. The development of this case study was informed by extensive interviews with Ohio State leadership, faculty, staff, and students.

Introduction

Ohio State is a public research university located in Columbus, Ohio, and is home to more than 66,000 students and more than 45,000 faculty and staff. The university boasts the largest health sciences campus in the country, including the Wexner Medical Center, which includes seven hospitals and seven health sciences colleges. For nearly a decade, the university and its health sciences elements have strongly prioritized building and nurturing a culture rooted in individual and community well-being.

In particular, Ohio State has fostered intentional and persistent initiatives to address and support the well-being of its medical, nursing, and health sciences students, trainees, and practicing clinicians. Together, these initiatives provide individual resources to students, faculty, and staff and structurally create an environment in which health and well-being are a meaningful part of everyday life.

This case study specifically outlines initiatives and programs at Ohio State that support the well-being of students, trainees, and clinicians. Central to the coordination and alignment of these initiatives are the One University Health and Wellness Council and the Buckeye Wellness Program, led by the Ohio State Chief Wellness Officer.

Strategic Visioning

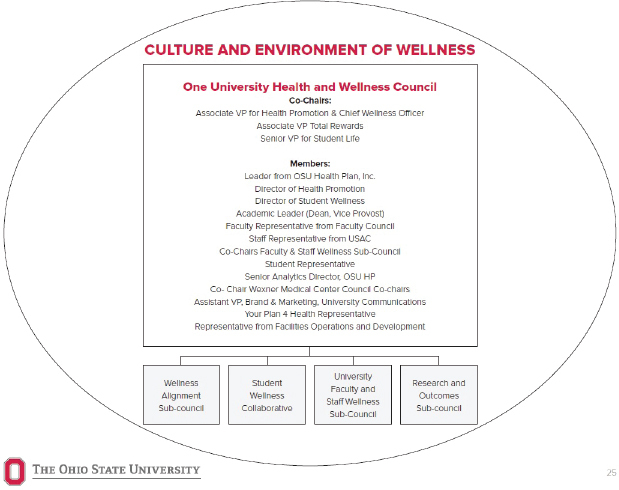

The pursuit of well-being is a core organizational strategy at Ohio State. The One University Health and Wellness Council1 (the Council) (Figure 1) provides strategic leadership for health and well-being initiatives at Ohio State. The Council comprises key leaders from across the university and representatives of faculty, staff, students, the university health plan, human resources, the medical center, facilities, and communications. The Council is co-chaired by the Ohio State Chief Wellness Officer; the Senior Vice President for Talent, Culture, and Human Resources; and the Senior Vice President for Student Life.

Figure 1. One University Health and Wellness Council.

SOURCE: Ohio State University, 2016 - 2019 Wellness Strategic Plan. Available at: https://wellness.osu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/2019/01/2016-2019%20Wellness%20Strategic%20Plan.pdf

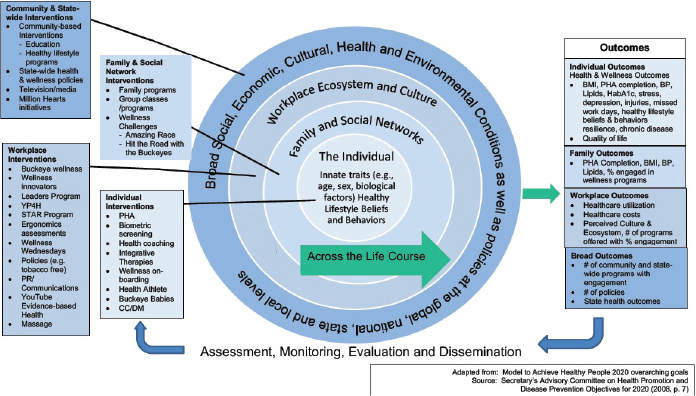

The Council has five sub-councils: Student Wellness, University Faculty and Staff Wellness, Research and Outcomes, Medical Center, and Wellness Alignment. The Wellness Alignment sub-council ensures the alignment of strategic wellness initiatives across the university and health system. The Council’s social-ecological framework2 (Figure 2) guides the development and implementation of evidence-based interventions directed at the individual, the social and family network, workplace culture and environment, and policy makers. In 2016, the Council released a four-year, university-wide strategic wellness plan3. The strategic plan includes a health and wellness scorecard that measures outcomes in three categories:

Figure 2. One University Health and Wellness Council’s Social-Ecological Framework.

SOURCE: Ohio State University, 2016 - 2019 Wellness Strategic Plan. Available at: https://wellness.osu.edu/sites/default/files/documents/2019/01/2016-2019%20Wellness%20Strategic%20Plan.pdf

-

1.

Culture and Environment of Health and Wellness, measured using the validated Ohio State Wellness Culture Survey, the Personal Health and Well-Being Assessment4, and additional data (see the strategic plan for more information).

-

2.

Population Health Outcomes, including data on burden of illness, healthy lifestyle behaviors, mental health, and physical health.

-

3.

Fiscal Health and Value of Investment, including per-member, per-year costs of health insurance for faculty, staff, and students; incentive and programmatic spending; annual costs of absenteeism, presenteeism (or working while ill), engagement, and disability; and excess costs associated with obesity, hypertension, diabetes, pre-diabetes, depression, and smoking.

The strategic plan calculates a cumulative productivity net savings of over $15 million from Ohio State’s wellness programming. For every dollar invested in wellness, the University has a $3.65 return on investment and is in a negative trend for health care spend for the third year in a row, whereas other institutions have been experiencing upward trends of 4% to 6% annually in health care spend [2].

More information can be found by visiting https://wellness.osu.edu/chief-wellness-officer. A new five-year wellness strategic plan will be released in late 2019.

University Leadership

Support from the highest levels of Ohio State leadership is central to building a strong culture rooted in well-being. Like the Chief Wellness Officer, Ohio State President Dr. Michael Drake lists university well-being as one of his three over-arching presidential priorities. Investing in well-being was an “obvious decision” for Dr. Drake, because such activities result in substantial return on investment and strengthen the university at large by increasing efficiencies and improving faculty, staff, and student satisfaction.

Buckeye Wellness

Buckeye Wellness5, an initiative with a team of experts in population health promotion, public health, and exercise science—led by Chief Wellness Officer and Vice President for Health Promotion Dr. Bernadette Melnyk—leads several university-wide programs aimed at creating and sustaining a culture that values, prioritizes, and structurally supports individual and community well-being. Working closely with multiple constituents from across the university, including within its medical and nursing colleges and the medical center, the Buckeye Wellness team ensures that all well-being offerings are rooted in evidence and that results are measured using data.

Office of the Chief Wellness Officer

On behalf of the university, the Chief Wellness Officer advocates for and advances the professional and academic fulfillment and well-being of the entire Ohio State community. The Chief Wellness Officer provides a unifying voice in support of well-being initiatives and activities and consistently links the importance of wellbeing to the vitality of the university at large. The Chief Wellness Officer works as a dedicated and vocal advocate and role model for students, staff, and faculty and makes it a point to spearhead and actively participate in university wellness events and activities.

The Chief Wellness Officer also consistently speaks across the university on the importance of systematically prioritizing well-being and offers motivation and evidence to managers and leadership that investing in well-being is financially responsible and crucial to the long-term success of the community. The Chief Wellness Officer interacts frequently with top leadership of the university and is a member of the university’s Senior Management Council6 and Council of Deans7.

“Health Athlete” Initiative

The Office of the Chief Wellness Officer funds the “Health Athlete” initiative8, a one- or expanded two-day program aimed at helping middle managers, executive leadership, faculty, staff, and clinicians from all health disciplines refocus and re-energize their personal and professional lives. Lessons learned throughout this immersive workshop, taught by the Buckeye Wellness team, focus on optimizing personal well-being and energy, as well as creating a culture of wellness in which all can benefit.

In addition to a focus on stress management, the workshop includes individual activities that support participants in finding purpose and meaning in their own lives. Findings from research suggest that clinicians who participate in the program have a decrease in body mass index and depressive symptoms over time [3]. An expanded study on the outcomes of individuals who attend this program is currently underway. A one-credit online version of this program is available to all Ohio State students, including nursing and medical students.

Grassroots Initiatives: Buckeye Wellness Innovators

The Buckeye Wellness team also leads a grassroots initiative, Buckeye Wellness Innovators9, which supports faculty and staff in developing wellness activities within their own units or departments. With the help of Buckeye Wellness staff, Innovators construct a wellness plan for their individual unit and serve as visible champions for health and well-being. Innovators help to strengthen culture by diversifying program offerings, developing local interventions, and motivating staff, faculty, and students.

The Buckeye Wellness team is integral to equipping Innovators with available resources and evidence to share with their colleagues. Buckeye Wellness intentionally connects Innovators with one another and is central to breaking down siloes and coordinating wellbeing initiatives throughout the entire university—a very necessary task at an institution as large and diverse as Ohio State. This approach ensures that employees from all levels have their voices heard and that bottom-up efforts are recognized and nurtured. This diverse array of local projects is a hallmark of well-being at Ohio State. Currently, there are nearly 600 faculty and staff Innovators at the university.

“It is critical to create an exciting vision and strategic plan for wellness that includes evidence-based interventions and diligent monitoring of outcomes over time. Remember that culture eats strategy, yet it takes time to build a culture that promotes optimal well-being and makes healthy behaviors the norm. Leaders, faculty, and managers must ‘walk the talk’ and provide needed wellness resources as well as support for ‘grassroots’ initiatives. Lastly, persist through the ‘character-builders’; the return [on] and value of investment—including faculty, staff, and students who are happy, healthy, and engaged—will be well worth it.”

- Dr. Bernadette Melnyk, Chief Wellness Officer, The Ohio State University

College of Medicine

Introduction and Overview

The Ohio State University College of Medicine, home to more than 800 students, offers a variety of curriculum- and non-curriculum-based programs to enhance and support student well-being. Its culture, rooted in a strong sense of community, is enhanced by faculty mentorship and a clear message that student well-being is a top priority for all.

In the past decade, the College of Medicine has worked to mitigate burnout and depression and to enhance student well-being through major cultural and curricular changes. Mentorship and peer-to-peer programming are paramount to these efforts, in addition to diverse learning options for students to build personal and professional skills. Many of the key features that support well-being throughout the College of Medicine can be applied to the accreditation standards10 of the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) and are important steps to mitigating burnout and increasing well-being.

Administrative leadership and faculty are devoted to building a positive learning environment by breaking down hierarchies, creating opportunities for students to share their voices and take action, and treating students with respect. A dean is on call at all times to off er students support on any issue related to their professional or personal lives. Ohio State medical students consulted for this case study were quick to note the importance of having leadership who openly discuss their own stress and encourage students to do the same to support one another. As noted by one student, “Our Deans and leadership are so important for student well-being. Their transparency, honesty, and support trickles down to students, and we feel that we have a strong support system when times are hard. Our Deans are rooting for us. It genuinely feels that they want us to succeed. They show up for us every day.”

Curriculum

The journey into medicine is challenging. At the College of Medicine, student well-being is placed at the heart of the curriculum and programming—a signal from leadership of not only the importance of helping students develop professional skills, but also the value in fundamentally supporting their well-being through programming, coursework, and mentorship. At the core of each student’s education is an integrated, required curriculum designed to help students build professional and personal life-enhancing skills that will support their well-being in medical school and will last far into their careers. Relevant academic program committees and the Executive Curriculum Committee review and approve all curricular components related to wellbeing before incorporating them into the curriculum. Student representatives participate on all review committees and are responsible for collecting student feedback and providing it to committees before activities are added to the curriculum.

Completing wellness-focused components of the curriculum is a requirement for all medical students. University leadership believes that their role as educators is to support student well-being by equipping students with necessary skills and providing them with mentorship, structured programming, and protected time to prioritize well-being. This engenders a culture in which a focus on well-being is expected and actively supported.

Core Competencies and Program Objectives Related to Student Well-Being

Ohio State’s Lead, Serve, Inspire curriculum includes eight core competencies11. In accordance with LCME accreditation standards, several medical education program objectives (MEPOs) guide the selection of curriculum content. Several of Ohio State’s MEPOs, listed below, are directly related to student well-being:

“There is always a finite amount of resources at any institution. A small investment can have a large return. Well-being does not always require a large budget. We started small and have grown over time after demonstrating that small things, like mentors and wellness areas, have helped our students. You have to start somewhere and it is best to start sooner rather than later. You will see an incremental return on investment. A little goes a long way.”

- Dr. Daniel Clinchot, Vice Dean for Education, The Ohio State University College of Medicine

-

1.

Develop the abilities to use self-awareness of knowledge, skills, and emotional limitations to engage in appropriate help-seeking behaviors.

-

2.

Demonstrate health coping mechanisms to respond to stress.

-

3.

Manage conflict between personal and professional responsibilities.

Several programs support these objectives and offer students structured and dedicated time for mentorship, skills building, personal and professional development, and resources for physical and mental health.

Pass/Fail Evaluation

Students at Ohio State are evaluated on a pass/fail basis in the first two years of the curriculum, a decision that was implemented in 2017 by the Executive Curriculum Committee as a way to assess student performance while minimizing stress and anxiety. Students noted that they believe the pass/fail evaluation is critical to developing a collaborative culture in which students want to see one another succeed. One student said, “The pass/fail grading system lowered my stress levels a lot. I think it has done the same for many others. Instead of trying to out-compete one another for the highest grade, we all come together to support each other in learning new material. We study together, we share notes, and we celebrate together after an exam is completed. My peers are not my competition. They are my friends.”

Career Exploration Week, Portfolio Coaches, and Academic Advising

Upon entering medical school, students partake in Career Exploration Week. As part of Career Exploration Week, each student is required to develop an individual wellness plan12. Each student reviews their wellness plan with an assigned portfolio coach, a dedicated and trained faculty member who works with the student during their entire medical school career.

Introduced in 2012, portfolio coaches act as mentors and are matched to students in their first semester. Students meet with their portfolio coaches seven to eight times per year to discuss career plans and opportunities, challenges they may be facing, their individual wellness plans, school-life integration, and more. Portfolio coaches also help students develop their academic and professional portfolio, which is shared with residency programs. Each coach may work with no more than eight students, ensuring that coaches are able to adequately devote time to each of their students and provide feedback and support as needed. Portfolio coaches are compensated for their time through central funding from the medical school.

During Career Exploration Week, students also complete Ohio State’s suicide prevention training: REACH13. Funded by a partnership between Ohio State’s Office of Student Life and the College of Education and Human Ecology, REACH training helps students to recognize warning signs of suicide and to help one another access care and treatment immediately.

MINDSTRONG Program

The MINDSTRONG program is an evidence-based cognitive behavioral skills-building program created by University Chief Wellness Officer Bernadette Melnyk. The program comprises seven brief sessions that constitute a workbook for students. All nursing students participate in the program as part of the curriculum. The program has been used with medical, nursing, pharmacy, and other health sciences students and clinicians at Ohio State to improve outcomes and promote cognitive behavioral skills, positive thinking, coping mechanisms for stress, healthy lifestyle behaviors, emotional intelligence, and sleep hygiene.

Based on the key concepts in cognitive behavioral therapy, the program aims to improve resiliency and self-protective factors to enhance well-being and decrease mental health risk factors. Previous research on the MINDSTRONG program (also known as “COPE” in several published studies) [5] has shown decreased anxiety, depression, stress, and suicidal intent among participants; increased academic performance; and increased levels of healthy lifestyle behaviors and overall job satisfaction. Given the success of the program with nursing, medical, pharmacy, and other health sciences students, the MINDSTRONG program will now be delivered to all first-year medical, nursing, and veterinary medical students. Beginning in fall 2019, an online 1-credit MINDSTRONG course will also be available to all Ohio State students who desire to learn cognitive-behavioral skills.

“Our Deans and leadership are so important for student well-being. Their transparency, honesty, and support trickles down to students, and we feel that we have a strong support system when times are hard. Our Deans are rooting for us. It genuinely feels that they want us to succeed. They show up for us every day. ”

- The Ohio State University College of Medicine Medical Student (anonymous)

Flexible Schedules

School policies allow for flexible student schedules. All lectures at the College of Medicine are offered in person and via live webcast, and are recorded for later viewing. Live webcasts allow students to participate in lectures from any location. One student noted that this helps her maintain a workout schedule because she can work out in the morning before her first lecture and watch her morning lecture from home while preparing for the day ahead. Recorded lectures allow students to consume information at their own pace and to watch lessons more than once. This flexibility gives students more control over their daily activities and allows them to operate in a way that makes sense for them.

Cultivating a Community of Support

Learning Communities

Student cohorts of 12 meet with faculty in noncurricular settings (e.g., local restaurants, faculty members’ houses) to develop personal relationships with peers and faculty members. Faculty members choose their own discussion topics for these meetings. Topics have included women in medicine, work-life integration, and financial well-being. Learning communities facilitate connections between students and faculty in a manner that breaks down hierarchical narratives that often persist in medical schools. Some students have come to view faculty and advisors as their cheerleaders instead of evaluators—a large morale boost within the College of Medicine. Leadership for this program gathers input from students regarding attendance requirements, meeting format, and discussion topics.

Student Wellness Team

Five student volunteers constitute a Student Wellness Team that informally surveys students about challenges affecting their well-being. The team collects feedback via casual conversations and word-of-mouth discussions. The wellness team communicates student feedback to medical school administration to help them develop programs that students will actually use.

For example, the wellness team learned that students with a mental illness noted stigma around mental illness within the medical school. In response, the wellness team added a sixth volunteer to focus entirely on how the College of Medicine can be more responsive to the needs of those with a mental illness and destigmatize mental illness within the College.

Funding for Student-Led Wellness Activities

The College of Medicine’s Student Council plans extracurricular student group initiatives using funding from the College of Medicine and the larger university. Individual groups can request up to $500 or partner with other groups for larger funding requests up to $2,000. Within the College of Medicine, a separate Medical Alumni Society also offers small grants to students for activities focused on wellness and other topics.

Optional Resources for Student Use

Wellness Room and Exercise Area

A wellness room within the College of Medicine includes light therapy lamps, meditation spaces, yoga mats, meditation rugs, pull-out couches, and more. Donated by the class of 1974, this space is open 24/7, and students can use it to de-stress in between classes or clinical work. Students can also invite faculty to lead well-being activities in this space. Mindfulness in Motion14, a stress reduction and resiliency-building program further detailed in the Wexner Medical Center section of this case study, has been hosted in this space and is free for students. Students guided the overall design of this space and were essential in determining what kinds of resources would be included. Current students most often use this space during the 10- to 15-minute breaks between classes or curricular activities to mentally check in with themselves, rest, or meditate before their next class or rotation. Students can also access a free exercise area between class and clinical assignments.

Counselors

A full-time counselor is available for all medical students and is free of charge. To maximize anonymity, the counselor’s office is located away from the routes that students typically take to and from class and clinical assignments. Students schedule appointments directly with the counselor, never needing to go through their academic advisors, peers, or faculty. A part-time psychiatrist is also available for students to use and is free of charge. Neither the counselor nor the psychiatrist participate in teaching or the evaluation of students.

Academic Support

An academic advisor is available for all students, to help them navigate the curriculum and career options. The academic advisor has access to faculty and collegial tutors so that students can participate in individual and group tutoring if desired.

Assessment and Continuous Improvement

Buckeye Wellness Onboarding Program

The University offers the opportunity to participate in a wellness onboarding program to all medical, nursing, pharmacy, and other health sciences students within the first two weeks of entering their professional programs. Students complete a personalized wellness assessment—including the PHQ-9 for depression [6], the GAD-7 for anxiety [7], and the BIPS inventory for stress [8]—along with questions related to their healthy lifestyle behaviors, including physical activity; sleep; healthy eating; alcohol, tobacco, e-cigarette, and drug use; and stress reduction practices. Students then create a personalized wellness plan and are matched with a nurse practitioner student who delivers the MINDSTRONG program with an additional module on sleep, healthy eating, and physical activity.

Students who enroll in the program benefit from it, as evidenced by decreases in depression, anxiety, and stress over the first year of their programs and increases in healthy lifestyle beliefs and behaviors [5].

Measuring Burnout and Well-Being

Measuring student well-being is central to building, adapting, and enhancing well-being program components. The College of Medicine annually administers a version of the Maslach Burnout Inventory15, Interpersonal Reactivity Index16, and an internally generated measure of quality of life and the learning environment. Collectively, these tools measure overall quality of life and burnout in Ohio State’s medical students. Overall, 94% of students report feeling engaged during their first two years of medical school. Data from the annual medical student survey is de-identified and included in a repository that faculty can access to measure the effectiveness of interventions from year to year. Faculty present results of the previous year’s survey during orientation, in conjunction with a presentation on the support resources that are available to students. Additionally, the Executive Curriculum Committee and the Office of Student Life monitor student reports from the Association of American Medical Colleges Graduation Questionnaire17. Over the past five years, rates of student burnout have decreased by 4% within the College of Medicine.

“The pass/fail grading system lowered my stress levels a lot. I think it has done the same for many others. Instead of trying to outcompete one another for the highest grade, we all come together to support each other in learning new material. We study together, we share notes, and we celebrate together after an exam is completed. My peers are not my competition. They are my friends.”

- The Ohio State University College of Medicine Medical Student (anonymous)

College of Nursing

Introduction and Overview

The Ohio State University College of Nursing—home to approximately 2,200 students enrolled in baccalaureate, master’s, doctorate of nursing practice, and doctorate programs—offers a variety of curriculum and non-curriculum-based programs to optimize student well-being. Wellness is built into the college’s five-year strategic plan, and outcomes are monitored annually. Administrative leadership is committed to building a positive learning environment that intentionally supports leadership development and embraces diversity, positivity, and wellness.

College of Nursing Strategic Plan

A five-year strategic plan26 for the College of Nursing identifies personal and professional wellness as core values and identifies several core goals that support student, trainee, and faculty well-being. These core goals include:

Producing the highest caliber of nurses, leaders, researchers, and health professionals who LIVE WELL (Lead, Innovate, Vision, Execute, and are Wellness-Focused, Evidence-Based, Lifelong Learners, and Lights for the World) and are equipped to effectively promote wellness, impact policy, and improve health outcomes across multiple settings with diverse individuals, groups, and communities;

Empowering faculty, staff, students, and alumni to achieve their highest career aspirations by enhancing an institutional culture that supports dreaming, discovering, and delivering, and an inclusive environment that embraces respect, diversity, positivity, civility, and wellness; and

Strengthening partnerships, from the local to global level, to improve the health and wellness of people throughout the university, community, state, nation, and world.

Given increasing rates of burnout [4] and compassion fatigue in nurses, the strategic plan for the College of Nursing emphasizes the integration of well-being throughout all academic programs and aims to create an environment for “exceptional student-centered learning and professional development.” Several focus areas from the strategic plan support a culture in which continuous learning, professional development, and well-being are prioritized and supported.

LIVE WELL Curriculum

The LIVE WELL curriculum at the College of Nursing aims to create an environment for exceptional student-centered learning and professional development, with emphasis on leadership, innovation, evidence-based practice, and wellness. The College’s strategic plan includes several goals for the LIVE WELL curriculum that foster an environment rooted in well-being. These goals include:

Promote recognition of innovation and quality in academic programs;

Empower students to achieve their personal and professional goals and interests through faculty mentorship and role modeling;

Incorporate tenets of LIVE WELL across the curriculum, assuring that all students are socialized in the core principles of leadership, innovation, evidence-based practice, and wellness;

Promote healthy lifestyle behaviors and the highest levels of wellness in faculty, staff, and students through ongoing seminars, events, and wellness activities; and

Provide regular leadership development and coaching to sustain a positive and extraordinary culture of wellness, employee engagement, and innovation.

People and Workplace Culture

The College of Nursing invests in staff, faculty, and students by creating a supportive, diverse work environment that maximizes human potential and promotes respect, diversity, positivity, civility, and wellness. The College does so through a commitment to:

Promote healthy lifestyle behaviors and the highest levels of wellness in faculty, staff, and students through ongoing seminars, events, and wellness activities. An exercise room is located in the College, and all faculty may request access to a standing desk. Walking treadmills are positioned throughout the College of Nursing, and regular circuit training, dance, and yoga classes are held on-site.

Establish a Workplace Culture Committee that is composed of faculty, staff, and students and charged with making recommendations and implementing strategies to support a positive, effective, innovative, and engaging work environment.

Provide regular leadership development and coaching to sustain a positive and extraordinary culture of wellness, employee engagement, and innovation.

Recently, the dean of the College of Nursing appointed two faculty members as directors of graduate and undergraduate wellness curriculum integration. These faculty members will lead more in-depth integration of wellness throughout all academic programs in the College. Both faculty members will have dedicated and compensated time for this purpose.

MINDSTRONG Program

Completion of an evidence-based cognitive behavioral skills building program, the MINDSTRONG program, is a requirement for all nursing students. Additional information about this program can be found in the section on the College of Medicine.

Banding Together for Wellness

Banding Together for Wellness is an optional student-focused wellness program. The program is designed to:

Promote the concept of “self-care for the nurse” by instilling a personal value of wellness;

Set the professional norm of improving and maintaining personal wellness to coincide with the other educational goals and objectives within the strategic plan of the College of Nursing; and

Encourage students to engage in wellness activities across the University to promote personal health and wellness.

The program is modeled around nine wellness dimensions (emotional, physical, creative, social, financial, spiritual, environmental, career, and intellectual). Each student participant is required to actively engage in an activity around each wellness dimension over a four-semester time frame. At the completion of the program, participants receive a certificate and a wellness honor cord that is worn at the Nursing Convocation graduation ceremony. According to the program exit survey, over 90 percent of participants agree that the program improved their personal well-being, and over 96 percent agree that the program taught self-care skills that will be helpful in their nursing practice (internal survey data, Ohio State).

Mental Health Counselors

The College of Nursing has two mental health counselors available to see students for mental health concerns. To improve access, a full-time counselor is fully funded through the College of Nursing, and a part-time counselor is funded through the Office of Student Life and the College of Nursing. Guidelines from the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act are closely followed to ensure student privacy.

Additional Strategies

Other methods that the College of Nursing uses to incorporate wellness into the curricula:

Wellness discussion boards;

Extra-credit wellness activities;

A faculty wellness toolkit that provides ideas and tools for incorporating wellness into course curricula; and

Discussion, education, and awareness sessions around the prevention of clinician burnout and compassion fatigue.

Assessment and Continuous Improvement

Buckeye Wellness Onboarding Program

The Buckeye Wellness Onboarding Program, further detailed in the College of Medicine section of this case study, is also offered to nursing students.

Department of Emergency Medicine Residency Program

Introduction and Overview

Residency can be an inherently stressful time, and the transition from medical student to resident can be an especially stressful event. Within Ohio State’s Department of Emergency Medicine, resident well-being focuses on holistically building a community rooted in trust, compassion, and comradery. Incentives, social events, and empowered trainees are the foundation to building a “home away from home” in which residents feel they have tangible support from their peers and strong social connections to help them navigate the world of being a new doctor. Supported by a $1 million endowment matched by $1 million in departmental funds, resident well-being initiatives within the Department of Emergency Medicine are designed using informal needs assessments and resident input. Over the next year, the department plans to implement a structured survey to more fully understand the needs of its residents.

Resident-Specific Teaching Rounds

To support resident well-being and improve overall learning, residents at Ohio State participate in formal resident-only Schwartz Rounds®18. Schwartz Rounds offer residents regularly scheduled time to openly and honestly discuss the social and emotional issues they face in caring for patients and their families. Resident-only Schwartz Rounds® are led by Ohio State Stress, Trauma, and Resilience program19 staff and occur several times a year. Staff use resident feedback to develop future rounds and to identify issues or cases that residents may be dealing with.

Resident Support Features

Building a “Home Away from Home”

A challenge for many residents is moving a long distance to complete their training. In most cases, they arrive without their usual support system, which can often lead to feelings of isolation and loss of community. In response to these challenges, residency program leadership prioritize developing a strong and supportive community in which residents and their families can thrive. Social events and activities, such as potlucks and sporting events, are designed so that residents’ families can also participate. Recently, faculty (led by Dr. Li-Sauerwine, Dr. Boulger, and Dr. Aziz) have begun volunteering to babysit several times a year. Residents drop off their children so that they can enjoy a date night with their spouse or have additional time for other activities.

Incentives

The residency program within the Department of Emergency Medicine uses incentives to motivate residents to practice self-care and participate in activities that enhance their overall well-being. Residents accumulate points for activities such as going to the dentist, exercising, healthy eating, and spending time with their children. Residents can then use these points for gift cards to local restaurants, cleaning services, car repair, and more. While well-being programs must look beyond individual behaviors, this approach acknowledges the effort it takes to nurture and maintain wellbeing during the tumultuous time of residency and rewards individuals, with the hope that these incentives will support a culture in which more residents prioritize their own well-being.

Communication is Best When Coming from Peers

As with many programs and organizations, communication can be hard. When the residency program first instituted well-being programming, members of the leadership team were initially the frontline communicators in spreading the word to residents. Over time, leadership has learned that residents are more likely to participate in well-being activities when hearing about these opportunities from their peers. Careful communication and continual monitoring of messaging has reassured residents that leadership is not using wellbeing programming to identify “weaknesses” among their trainees.

Fiscal Sustainability

A $1 million endowment matched by $1 million in departmental funds provides a sustainable future for well-being programming and solidifies the department’s commitment to well-being. The Samuel Kiehl III Wellness Endowment20 was gifted in 2015. A Wellness Committee develops a budget each year and comprises several faculty and residents (numbers vary each year but there are approximately 12 representatives from the department). Residents can also request funds for events and activities by submitting proposals to the Wellness Committee. Each proposal must describe how the activity supports well-being and/or personal or professional development. The Wellness Committee follows up on approved activities to learn about challenges and successes and to brainstorm future improvements. This funding mechanism empowers residents to plan well-being-related activities that uplift the community.

Assessment and Continuous Improvement

Program leadership understands the importance of obtaining (and using) feedback from residents. In building well-being initiatives, leadership informally surveys residents to better understand their needs. While the execution of such surveys can be labor intensive, leadership credits these surveys with helping them remain responsive to the needs of residents. This continual reassessment and flexibility in program design has been critical to meeting needs year after year.

For example, a recent survey found that many residents with young children felt disengaged from wellbeing activities because they did not have child care or did not feel as though bringing their children to events would be acceptable. To remedy this concern, the program recently hosted a social outing in which faculty remained at the medical center after hours to babysit residents’ children so that they could enjoy social time without needing to find and finance their own child care.

Residency program leadership is currently working with the Office of the Chief Wellness Officer to identify a more rigorous and validated instrument to measure overall well-being and to identify their current strengths and opportunities. In coordination with the medical center, the residency program also administers the annual resident survey from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education21.

“Five years ago, we had nothing to support resident well-being. We still have a lot to learn and a lot of room to grow, but starting small helped us find concrete ways in which we could at least begin this work. A needs assessment was key for us in taking a hard and honest look at where we were lacking. Setting small goals is also helpful. Having all residents become a 10/10 on well-being is unrealistic. But if we can help bring someone from a 3 to a 5, we’re doing our job right. Sometimes the things you think are frivolous can mean so much. Constantly reassessing and being very flexible in your programming is necessary. People change and they may need bigger or different resources.”

- Dr. Creagh Boulger, Fellowship Director, Department of Emergency Medicine, The Ohio State University

Wexner Medical Center

Clinicians around the country face a variety of stressors that can lead to burnout and decreased well-being. At Ohio State, efforts to promote and support clinician well-being include facilitated traumatic event debriefings, monthly Schwartz Rounds®, and a preventive health initiative that offers staff retreats, free mindfulness courses, and culinary medicine classes.

Introduction and Overview

Clinician well-being efforts within the Ohio State health system are primarily focused on trauma recovery support and open communication between clinicians on the social and emotional issues they face in providing care.

The Stress, Trauma, and Resilience (STAR) Program houses two key programs that support clinician wellbeing: Brief Emotional Support Teams and Schwartz Rounds®. Brief Emotional Support Teams offer mental and psychological support to clinicians after stressful and traumatic events, facilitating team debriefs and identifying individuals who may need additional support. Schwartz Rounds® provide a venue for clinicians to openly and honestly discuss difficult cases and experiences and to support one another in those experiences. The STAR Program opens doors to human connection and lessens the burden each clinician faces in dealing with issues alone.

Dr. Steven Gabbe, former chief executive officer of the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center, has played a significant role in shaping and funding these programs and has served as a transparent and vocal role model for clinicians and trainees. Dr. Gabbe’s leadership has helped cultivate a culture that is rooted in well-being. Recently, in his honor, Ohio State launched the Gabbe Health and Wellness Initiative, a preventive health initiative that offers staff retreats, free mindfulness courses, and culinary classes. The initiative launched in fall 2018, and additional programming will be added over the next several years.

Ohio State measures clinician well-being through a biannual engagement survey, which allows it to identify units that may need additional support.

Stress, Trauma, and Resilience Program

Brief Emotional Support Teams

Through the use of Brief Emotional Support Teams (BESTs)22, Ohio State’s STAR program offers mental and psychological support to clinicians after stressful and traumatic events, such as the loss of a patient. BESTs are trained clinicians who provide immediate, direct, and temporary emotional support to clinicians and staff after stressful or traumatic events. Since its inception in 2009, the program has trained more than 450 clinicians to recognize and deploy trauma recovery services for individuals and teams.

BESTs use a framework that helps teams nurture a culture of built-in support among peers in the workplace. BESTs identify individuals and teams that need additional support after a traumatic event and lead them through activities that build upon and reinforce the existing relationships between team members. Initial funding for clinician activities within the STAR program came from the medical center—$300,000 per year for three years. The program now hosts a yearly fundraising event, Faces of Resilience23, to continue the program. In 2018, it raised $580,000.

Communicating about Brief Emotional Support Teams

Prior to the launch of BESTs, STAR program leadership conducted “STAR rounding”—walk-throughs of individual units to educate clinicians on forthcoming programs and services. Program leadership also used previously scheduled electronic health record trainings to speak to clinicians about programming and how to access support services. When asked about their biggest lessons in creating a program in which clinicians feel safe to share their experiences of traumatic events, STAR program leadership notes, “You can’t build trust without getting out and meeting people. People are more likely to seek help with those they are familiar with.”

Identifying Opportunities for Trauma Debriefings through System-Wide Call Line

An in-house operating line (STAR line) is a resource for clinicians to identify a trained trauma debriefing facilitator after a traumatic event. A call to the STAR line will notify the STAR program team, who will deploy trained employees to respond to the event. The STAR team will typically respond within 24 hours.

Brief Emotional Support Teams Staff Training

Training to become a facilitator includes a half-day session taught by STAR program leadership. To protect the fidelity of the model and ensure all BESTs are taught in the same manner, only a few individuals are trained to teach the half-day course. A star worn on their clothing easily identifies trained clinicians.

Components of a Trauma Debriefing

The immediate trauma debriefing is typically 15-20 minutes. While it can be challenging to pull a trained clinician away from their workflow to facilitate a trauma debriefing on another unit, the short time frame of a debriefing has made it easier to use.

A typical debriefing includes psychological first aid24, a seven-stage crisis intervention [9], motivational interviewing, and cognitive reframing to help reframe harmful narratives after traumatic events. This approach helps to prevent clinicians from developing “manufactured memories” in which they often assign blame to themselves. Following the initial trauma debriefing, STAR program staff follow up individually with clinicians to connect them with additional support services if needed.

The STAR program maintains a database of trauma debriefings and the outcomes of each intervention. To date, more than 2,000 interventions have taken place. Current data suggest that a large majority of individuals (80-83%) who participate in a STAR-facilitated trauma debriefing return to the floor and finish their shifts. Another 7-10% need additional services following the debriefing, usually in the form of three to five confidential counseling sessions offered through the Employee Assistance Program25, and 7-10% are connected with Ohio State’s trauma-informed outpatient therapy clinic for more intensive and longer-term treatment. The STAR program also works directly with the risk management department to identify individuals who may need additional support—including a more systems-level approach instead of an individual program.

Schwartz Rounds®

Schwartz Rounds®18 offer clinicians regularly scheduled time to openly and honestly discuss the social and emotional issues they face in caring for patients and their families. These sessions are interdisciplinary, often including physicians, nurses, social workers, advanced practitioners, chaplains, and allied health professionals.

Ohio State holds Schwartz Rounds® the first Friday of every month. These meetings are open to all clinicians and medical center staff and typically include an average of 180 people. A free lunch is included. A multidisciplinary team of nine clinicians develops topics for these monthly meetings. Typically, a meeting includes a case-based multidisciplinary panel presentation, followed by a facilitated discussion.

Schwartz Rounds® often illustrate that many clinicians may be struggling with similar issues. In connecting clinicians with one another, these meetings provide an opportunity for clinicians to discuss similar challenges they may be facing and to underscore that they are not alone in those challenges. These meetings also provide a space for colleagues to converse with each other in a nonjudgmental way.

Informal feedback surveys are used at the conclusion of each session to help inform future meetings. Program leadership notes that Schwartz Rounds® contribute to a supportive culture within the medical center community by intentionally opening lines of communication and providing space for clinicians to openly discuss issues they are facing and the feelings that accompany them.

Gabbe Health and Wellness Initiative

Launched in fall 2018, the Gabbe Health and Wellness Initiative coordinates programs to improve the well-being of faculty and staff through education and preventive health programming. The initiative currently offers a free mindfulness course, culinary medicine classes, and well-being retreats. It is run by one full-time staff person and overseen by a 10-member steering committee that meets quarterly to discuss upcoming priorities and new programming. Funding for the initiative is provided through an internal risk management grant to support patient and staff safety initiatives.

Mindfulness in Motion

Developed by Dr. Maryanna Klatt, Mindfulness in Motion is an eight-week program to help clinicians reduce stress and build mindfulness skills. Piloted in 2004 as part of an exploratory grant from the National Institutes of Health, the program now includes weekly one-hour on-site sessions.

Sessions occur during mealtime and food is provided. Each session aims to teach participants relaxation techniques, effective sleep habits, mindful eating techniques, and more. Overall, the program teaches participants to use their bodies to focus on the present moment, to explore what causes them to experience stress, and to learn techniques for reducing stress. Upon completing the eight-week program, clinicians receive a monthly in-person “booster” session to sustain their outcomes.

Since its inception, more than 300 clinicians of all disciplines have participated in the program. Early research suggests that participation in the program can reduce burnout and increase work engagement [10]. Results also indicate a decrease in perceived stress [11], burnout, and inflammation in overweight individuals. Participants claim it has changed their relationship to stress and has empowered them to access choices they didn’t realize they had. Program facilitators note that the program helps to create community, increase collaboration, and improve teamwork within units. To date, 18 Ohio State staff have been trained to deliver the program, widely increasing its availability.

Culinary Medicine

The Gabbe Health and Wellness Initiative currently offers a free five-session course on culinary medicine in which clinicians and staff learn basic cooking skills, share a meal, and discuss a case study.

Each session offers tips and educational materials on how to eat healthier. This is followed by a group cooking lesson in which the 16-person class cooks and eats a meal together. While eating, the group discusses a case study related to culinary medicine. Case study topics have included an introduction to culinary medicine, anti-inflammatory diets, cancer nutrition, eating healthy fats, and weight management and portion control.

The course is currently in its second cohort. Informal written surveys are used at the end of each cohort to measure participant satisfaction and to identify future areas of improvement.

Staff Well-Being Retreats

The Gabbe Health and Wellness Initiative is currently piloting staff well-being retreats. Units can request funding to support unit-specific off-site retreats to enhance team-building skills and to promote team communication. Retreat agendas vary and are developed in coordination with the unit lead. Program leadership hopes that the retreats offer a morale boost for teams who may be dealing with stress and provide an opportunity for teams to enhance relationships in a fun environment.

Assessment and Continuous Improvement

A biannual survey is administered to all clinicians, trainees, and staff within the Ohio State health system to assess overall engagement and well-being. A “pulse survey” is administered in the off year for units and teams that noted low engagement numbers on the biannual survey. Leadership is currently considering adopting the Mini Z Burnout Survey in their next biannual survey (fall 2019).

Conclusion

The initiatives and programs highlighted throughout this case study serve as examples to other organizations where clinician burnout remains high. While there is no one-size-fits-all solution, clinician burnout must be addressed at the systems level. Leaders must be actively engaged in supporting clinician well-being by ensuring funding and appropriate staffing and by collecting data and piloting programs that support well-being. While Ohio State’s programs and policies will not be directly applicable to every institution, this case study offers practical guidance and potential solutions that may be implemented and adapted in other systems and organizations.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Lois Margaret Nora, MD, JD, MBD of Northeast Ohio Medical University; Bryant Adibe, MD, of Rush University Medical Center; and Jonathan Ripp, MD, MPH, of Mount Sinai Icahn School of Medicine for their important contributions to this paper. The authors would also like to thank the more than 30 Ohio State University professionals who shared their experiences for the development of this case study. The authors would like to extend special thanks to Creagh Boulger, MD; Daniel Clinchot, MD; Michael Drake, MD; Steven Gabbe, MD; Maryanna Klatt, PhD; Simiao Li-Sauerwine, MD; Bernadette Melnyk, PhD, RN, CPNP/PMHNP, FAANP, FNAP, FAAN; Susan Moffatt-Bruce, MD, MBA, FACS; Beth Steinberg, MS, RN, NEA-BC; Andrew Thomas, MD, MBA, FACP; and Kenneth Yeager, PhD, LISW-S.

Funding Statement

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily of the authors’ organizations, the National Academy of Medicine (NAM), or the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (the National Academies). The paper is intended to help inform and stimulate discussion. It is not a report of the NAM or the National Academies. Copyright by the National Academy of Sciences.

Notes (identified as superscript numbers throughout the text)

Conflict-of-Interest Disclosures: Kyra Cappelucci was an employee of the National Academy of Medicine at the time of this manuscript’s development. Mariana Zindel and Charlee Alexander are employees of the National Academy of Medicine. Neil Busis receives financial and non-financial support from the American Academy of Neurology, and is a member of the Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience. H. Clifton Knight is a member of the Action Collaborative on Clinician Well-Being and Resilience.

Contributor Information

Kyra Cappelucci, National Academy of Medicine.

Mariana Zindel, National Academy of Medicine.

H. Clifton Knight, American Academy of Family Physicians.

Neil Busis, University of Pittsburgh.

Charlee Alexander, National Academy of Medicine.

References

- 1.Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, Cipriano PF, Bhatt J, Ommaya A, West CP, Meyers D. NAM Perspectives. National Academy of Medicine; Washington, DC: 2017. Burnout Among Health Care Professionals: A Call to Explore and Address this Underrecognized Threat to Safe, High-Quality Care. Discussion Paper. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melnyk BM. Making an Evidence-Based Case for Urgent Action to Address Clinician Burnout. The American Journal of Accountable Care. 2019;7(2):12–14. https://www.ajmc.com/journals/ajac/2019/2019-vol7-n2/making-an-evidencebased-case-for-urgent-action-to-address-clinician-burnout. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hrabe DP, Melnyk BM, Buck J, Sinnott LT. Effects of the Nurse Athlete program on the healthy lifestyle behaviors, physical health, and mental well-being of new graduate nurses. Nursing Administration Quarterly: October/December 2017. 2017;41(4):353–359. doi: 10.1097/NAQ.0000000000000258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jennings BM. Work Stress and Burnout Among Nurses: Role of the Work Environment and Working Conditions. In: Hughes RG, editor. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); Chapter 26; 2008. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2668/ [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lusk P, Melnyk BM. COPE for depressed and anxious teens: A brief cognitive behavioral skills building intervention to increase access to timely, evidence-based treatment. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing. 2015;26(1):23–31. doi: 10.1111/jcap.12017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lowe B, Decker O, Muller S, Brahler E, Schelberg D, Herzog W, Herzberg PY. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Medical Care Journal. 2008;46(3):266–274. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lehman KA, Burns MN, Gagen EC, Mohr DC. Development of the Brief Inventory of Perceived Stress. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2013;68(6):631–644. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts AR, Ottens AJ. The seven-stage crisis intervention model: A road map to goal attainment, problem solving, and crisis resolution. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention. 2005;5(4):329–339. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klatt M, Steinberg B, Duchemin AM. Mindfulness in Motion (MIM): An onsite mindfulness based intervention (MBI) for chronically high stress work environments to increase resiliency and work engagement. Journal of Visualized Experiments. 2015;(101):52359. doi: 10.3791/52359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malarkey WB, Jarjoura D, Klatt M. Workplace based mindfulness practice and inflammation: a randomized trial. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2013;27(1):145–154. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]