Abstract

Arterial media calcification is frequently seen in elderly and patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), diabetes and osteoporosis. Pyrophosphate is a well-known calcification inhibitor that binds to nascent hydroxyapatite crystals and prevents further incorporation of inorganic phosphate into these crystals. However, the enzyme tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP), which is expressed in calcified arteries, degrades extracellular pyrophosphate into phosphate ions, by which pyrophosphate loses its ability to block vascular calcification. Here, we aimed to evaluate whether pharmacological TNAP inhibition is able to prevent the development of arterial calcification in a rat model of warfarin-induced vascular calcification. To investigate the effect of the pharmacological TNAP inhibitor SBI-425 on vascular calcification and bone metabolism, a 0.30% warfarin rat model was used. Warfarin exposure resulted in distinct calcification in the aorta and peripheral arteries. Daily administration of the TNAP inhibitor SBI-425 (10 mg/kg/day) for 7 weeks significantly reduced vascular calcification as indicated by a significant decrease in calcium content in the aorta (vehicle 3.84±0.64 mg calcium/g wet tissue vs TNAP inhibitor 0.70±0.23 mg calcium/g wet tissue) and peripheral arteries and a distinct reduction in area % calcification on Von Kossa stained aortic sections as compared to vehicle. Administration of SBI-425 resulted in decreased bone formation rate and mineral apposition rate, and increased osteoid maturation time and this without significant changes in osteoclast- and eroded perimeter. Administration of TNAP inhibitor SBI-425 significantly reduced the calcification in the aorta and peripheral arteries of a rat model of warfarin-induced vascular calcification. However, suppression of TNAP activity should be limited in order to maintain adequate physiological bone mineralization.

Keywords: VASCULAR CALCIFICATION, MINERAL BONE DISORDER, ALKALINE PHOSPHATASE, WARFARIN, PYROPHOSPHATE

1. Introduction

Arterial media calcification is an active cell-regulated process depending on the conversion of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) to an osteoblast-like phenotype facilitating the deposition of calcium-phosphate crystals into the medial layer of the artery. This process leads to reduced arterial compliance and elasticity which in turn induces hypertension, left ventricular hypertrophy and impaired coronary perfusion ultimately resulting in heart failure which undoubtedly entails a significant impact on survival [1,2]. Elderly and patients suffering from chronic kidney disease (CKD), diabetes and osteoporosis are at high risk for developing arterial media calcification [2–4]. Current therapies focus on targeting the specific risk factors for arterial media calcification in each patient population (CKD, diabetes and osteoporosis). For example phosphate binding agents are prone to moderate efficacy and poor compliance and their use is restricted to CKD patients as they aim to control CKD-specific risk factors for vascular calcification [5,6]. Effective therapies to prevent and cure arterial media calcification in the various populations at risk are currently lacking and new treatment strategies are urgently needed.

Ideally, these innovative compounds should directly target the calcification process as intervening on several risk factors is not feasible. For example, intravenous treatment with sodium thiosulfate is an effective and direct therapy against calciphylaxis, a rare form of arterial calcification in small arteries leading to skin necrosis, through its action as an antioxidant and calcium chelating agent [7]. Vascular smooth muscle cells, located in the media layer of the vessel wall, retain the capacity to transdifferentiate into bone-like cells and are able to generate calcium-phosphate crystals which may serve as nidi for further mineralization [8,9]. In addition ectopic calcification in patients with diabetes and osteoporosis [10,11] occurs at physiological phosphate and calcium levels, implying that underlying causes other than merely crystal precipitation, such as a decreased concentration of calcification inhibitors, must be responsible for these ectopic calcifications. One of the most powerful endogenous calcification inhibitors is pyrophosphate (PPi) which binds to nascent hydroxyapatite crystals thereby preventing further incorporation of inorganic phosphate into these crystals [12]. In dialysis patients, plasma PPi levels are decreased and negatively associated with vascular calcification [13,14]. In addition, the inhibitory effect of PPi on vascular calcification has been shown in several animal models [15–17] and in both aortic ring [18] and aortic valve [19] cultures. VSMCs are able to generate PPi via hydrolysis of the extracellular nucleotide ATP which is mediated by the ecto-nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 1 enzyme.

Importantly, PPi can be degraded by tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP), an ectoenzyme crucial for bone mineralization, into inorganic phosphate a well-known promotor of tissue calcification [20]. In this regard, a stable PPi/phosphate ratio is key to maintain normal mineralization in the bone and to protect against ectopic calcification in soft tissue. In calcified arteries, expression of TNAP is increased implying that PPi is continuously degraded into phosphate ions thereby creating a procalcifying environment in the vessel wall [21–23]. The emerging role of TNAP in vascular calcification encouraged researchers to develop TNAP inhibitors as a therapeutic strategy to treat soft-tissue calcification. Early TNAP inhibitors, such as L-homoarginine and levamisole, appeared to have a weak binding capacity and to be not entirely selective against TNAP [24]. Millán and collaborators discovered and validated a series of aryl sulfonamides as selective pharmacological inhibitors of TNAP [25,26]. A proof of concept experiment revealed that mice orally dosed (10 mg/kg/day) with SBI-425 showed >75% and 50% inhibition of plasma TNAP activity 8 and 24 hours after administration, respectively [26]. Additionally, SBI-425 has been shown to inhibit arterial calcification in two mouse models overexpressing TNAP in either VSMCs or endothelial cells [27,28]. These promising results were the impetus to evaluate the effect of this TNAP inhibitor on arterial calcification in an experimental model in which the calcification is not driven by TNAP overexpression, which is likely to be more relevant with regard to the clinic. Therefore, we have evaluated whether SBI-425 is able to reduce arterial calcification in a rat model of warfarin-induced arterial media calcification. This animal model offers the interesting advantage in that it allows to investigate the potential direct therapeutic effect of SBI-425 on the process of arterial media calcification without interference of CKD-, diabetes- or osteoporosis-related risk factors. Warfarin, a widely prescribed anticoagulant, interferes with vitamin K epoxide reductase and therefore antagonizes vitamin K recycling [29]. Vitamin K is required for activation of matrix Gla protein (MGP), a well-known calcification inhibitor. Rats administered a warfarin containing diet develop a gradual time-dependent increase in calcium content in the aorta and peripheral arteries with a significant difference from controls from week 6 of warfarin exposure onwards [30]. These mild to moderate arterial media calcifications as well as their development pattern are comparable to those observed in CKD, diabetes and osteoporosis patients [31,32].

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Animal experiment

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals 85–23 (1996) and approved by the University of Antwerp Ethics Committee (Permit number: 2017–05). Animals were housed two per cage, exposed to 12-hour light/dark cycles, and had free access to food and water.

To induce vascular calcification, 20 male Wistar rats (200–250g, Iffa Credo, Belgium) were administered a warfarin containing diet (0.30% warfarin and 0.15% vitamin K1 to prevent lethal bleeding) (synthetic diet from SSNIFF Spezialdiäten, Soest, Germany) for the entire study period and were subjected to the following treatments: (i) vehicle (n=10) or (ii) 10mg/kg/day SBI-425 (TNAP inhibitor) (n=10). A control group of 10 healthy Wistar rats with normal renal function of the same gender and age and receiving the same diet composition, however without warfarin-supplementation was set up after completion of the intervention study. Concomitantly with the sample analysis of this healthy control group, samples of the warfarin treated rats were re-analyzed. SBI-425 was provided by J.L. Millán and synthesized at the Prebys Center for Drug Discovery, Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute (La Jolla, CA). Vehicle and SBI-425 were administered daily via an i.p. catheter (rounded polyurethane catheter ROPAC-3.5PR, Access technologies, Illinois, USA) from the start of warfarin exposure until the end of the study at week 7. One week before the start of the study, the i.p. catheter was placed into the peritoneal cavity of the rat. Animals were anaesthetized with a cocktail of 60 mg/kg ketamine (Pfizer, Puurs, Belgium) and 7.5 mg/kg xylazine (Bayer Animal Health, Monheim, Germany) after which an incision was made in the skin in the right flank of the abdomen. The skin was separated from the muscle layer and the catheter was introduced into the peritoneal cavity. The port was displaced at the subcutaneous space of the rat’s back. Thereafter, a saline solution was injected into the port of the catheter to prevent catheter trapping. SBI-425 was dissolved in 1% ethanol, 0.3% sodium hydroxide and 98.97% dextrose (5% dissolved in PBS). Vehicle treatment consisted of the solvent without addition of SBI-425. Before the start of the study, at week 2 and 5 and at sacrifice, animals were placed in metabolic cages to collect 24 h urine samples, followed by blood sampling via the tail vein of restrained, conscious animals. To enable histomorphometric analysis of dynamic bone parameters, rats were injected i.v. with 30 mg/kg tetracycline and 25 mg/kg demeclocycline at 7 and 3 days before euthanasia.

At sacrifice, rats were exsanguinated through the retro-orbital plexus after anesthesia with 80 mg/kg ketamine (Pfizer, Puurs, Belgium) and 10 mg/kg xylazine (Bayer Animal Health, Monheim, Germany) via intraperitoneal injection.

2.2. Analysis of biochemical parameters

Total serum and urine phosphorus levels were analyzed with the Ecoline S Phosphate kit (Diasys, Holzheim, Germany) and serum and urinary calcium levels were determined with flame atomic absorption spectrometry (Perkin-Elmer, Wellesley, MA, USA) after appropriate dilution in 0.1% La(NO3)3 to eliminate chemical interference. Measurement of alkaline phosphatase activity in serum and aortic tissue as well as serum alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) levels was done by use of an auto-analyzer (Dimension Vista 1500 System, Siemens AG, München, Germany) at the Antwerp University Hospital. Alkaline phosphatase activity was measured by using p-nitrophenyl phosphate as a substrate which is converted by alkaline phosphatase to a yellow chromogen p-nitrophenyl. This method is based on a procedure previously reported by Bowers and McComb [33]. To measure aortic alkaline phosphatase activity, tissue samples were homogenized in RIPA buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) supplemented with 2% Triton (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA), 0.51 mg/ml aproteïne (MP Biomedicals, Solon, Ohio, USA) and 3.14 mg/ml benzamidine (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, USA) on ice. Total protein content of the aortic lysate was measured with the BCA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Illinois, USA). Serum immunoreactive parathyroid hormone (PTH) (Immutopics, San Clemente, CA) and fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) (Kainos Laboratories, Tokyo, Japan) levels were measured using an ELISA kit.

2.3. Quantification of vascular calcification

To visualize and quantify calcification in the aortic wall, sections of the thoracic aorta were stained with Von Kossa’s method. The thoracic aorta was isolated and immediately fixed in neutral buffered formalin for 90 min after which it was cut into 15–20 parts of 2 to 3 mm which were then embedded upright in a paraffin block. Four μm thick sections were stained with Von Kossa’s method and counterstained with hematoxylin and eosin to detect and quantify calcification. The percentage calcified area was calculated using Axiovision image analysis software (Release 4.5; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), in which two color separation thresholds measure the total tissue area and the Von Kossa positive area. After summing both absolute areas, the percentage of calcified area was calculated as the ratio of the Von Kossa positive area versus the total tissue area.

Calcification in the aorta and smaller arteries was also quantified by measurement of the calcium content. The proximal part of the abdominal aorta and the left carotid and femoral arteries were isolated and directly weighed on a precision balance. The arterial samples were digested in 65% HNO3 at 60°C for 6 hours. The calcium content in the digests was measured with flame atomic absorption spectrometry and expressed as mg calcium/g wet tissue.

2.4. Bone histomorphometry

The left tibia was fixed in 70% ethanol overnight at 4°C, dehydrated and embedded in 100% methylmethacrylate (Merck, Hohenbrunn, Germany) for bone histomorphometry. For analysis of static bone parameters, 5 μm thick sections were Goldner stained for visualization and measurement of total bone area, mineralized bone area, osteoid area/-width/-perimeter, osteoblast perimeter, eroded perimeter, osteoclast perimeter, trabecular thickness and trabecular distance using the Axiovision image analysis software (Release 4.5, Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Ten μm thick unstained sections of the tibia were used to measure the distance between and length of double tetracycline and demeclocycline labels by fluorescence microscopy. Out of these primary data, additional dynamic bone parameters (bone formation rate, mineral apposition rate, adjusted apposition rate, mineralization lag time, osteoid maturation time) were calculated according to Dempster et al.[34].

2.5. Quantitative real time PCR

The mRNA transcript expression of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Rn99999916_s1), TNAP (Rn01516028_m1), Runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2) (Rn01512296_m1), collagen 1 (Rn00801649_g1), collagen 2 (Rn00491926_g1) and SRY-box transcription factor 9 (Sox9) (Rn01751069_mH), matrix Gla protein (MGP) (Rn00563463_m1), ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 1 (NPP1) (Rn01638706_m1) and 3 (NPP3) (Rn00571329_m1) and phosphoethanolamine/phosphocholine phosphatase 1 (PHOSPHO1) (Rn01496968_m1) was determined in the distal part of the abdominal aorta. Total mRNA was extracted using the RNeasy Fibrous Tissue mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and reverse transcribed to cDNA by the High Capacity cDNA archive kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with an ABI Prism 7000 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems) based on TaqMan fluorescence methodology was used for mRNA quantification. TaqMan probe and primers were purchased as TaqMan gene expression assays-on-demand from Applied Biosystems. Each gene was tested in triplicate and normalized to the expression of the reference transcript GAPDH.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons were made by non-parametric testing (SPSS 24.0 software, IBM. Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). To investigate the statistical difference between groups at one time-point, a Mann-Whitney U test was applied. Comparisons between time-points within each group were performed with a Friedman related samples test, followed by a Wilcoxon signed rank test. Representative data are presented as mean ± SEM (standard error of mean) and considered significant when p-value ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

All animals survived until the end of the study without important adverse events. In both the vehicle and SBI-425 dosed groups, body weight and food consumption remained stable throughout the entire study period with no differences between both study groups (data not shown).

3.1. Administration of SBI-425 does not affect calcium and phosphorus metabolism, nor does it induce liver toxicity

Since phosphorus and calcium are important inducers of vascular media calcification, we evaluated whether daily SBI-425 administration had an effect on circulating calcium and phosphorus levels. No differences in serum calcium and phosphorus levels were found between vehicle and SBI-425 treated rats (Table 1). Moreover, at sacrifice, no differences in either serum PTH or FGF23 levels were found between vehicle and SBI-425 treated animals (Table 1). Additionally, serum alkaline phosphatase activity was not altered between vehicle and SBI-425 treated rats (Table 1). Alkaline phosphatase activity was also measured in aortic tissue, however no significant changes were observed after 7 weeks of treatment with a TNAP inhibitor (vehicle: 9.48±0.87 U/g wet tissue, SBI-425: 11.76±1.23 U/g wet tissue, normal value: 12.27±1.96 U/g wet tissue). To investigate whether SBI-425 treatment affects liver function, both serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) concentrations were analyzed. After 7 weeks of treatment with a TNAP inhibitor, no significant increase of serum ALT and AST activity was observed (Table 1) indicating that no liver toxicity was induced by SBI-425 treatment.

Table 1:

Serum biochemical values.

| Week 0 | Week 3 | Week 7 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Vehicle | SBI-425 | Vehicle | SBI-425 | Vehicle | SBI-425 | Normal values | |

| Calcium (mg/dl) | 14.4±0.2 | 13.8±0.1 | 13.3±0.1 | 13.3±0.1 | 13.0±0.1ab | 13.0±0.1ab | 13.9±0.3 |

| Phosphorus (mg/dl) | 12.2±0.6 | 11.3±0.3 | 11.5±1.5 | 9.1±0.4a | 8.6±0.3a | 9.2±0.2a | 8.39±0.59 |

| ALT (U/L) | 54.0±2.4 | 57.5±2.2 | 24.3±1.7a | 27.8±2.2a | 26.6±2.5ab | 26.4±1.8ab | 45.0±3.48 |

| AST (U/L) | 84.6±2.6 | 85.8±2.1 | 74.6±3.4 | 79±3.5 | 105.9±7.2a | 105.1±4.9 | 108.3±7.9 |

| ALP (U/L) | 331±19 | 305±19 | 180±9a | 180±11a | 152±18a | 170±13a | 148±13 |

| PTH (pg/ml) | 680±203 | 669±150 | 547±239 | ||||

| FGF23 (pg/ml) | 543±128 | 404±40b | 295±53 | ||||

ALT: alanine aminotransferase, AST: aspartate aminotransferase, ALP: alkaline phosphatase, PTH: parathyroid hormone, FGF23: fibroblast growth factor 23, Mean ± SEM

P<0.05 versus time point 0

P<0.05 versus normal values, vehicle (n=10), SBI-425 (n=10), normal values (n=10)

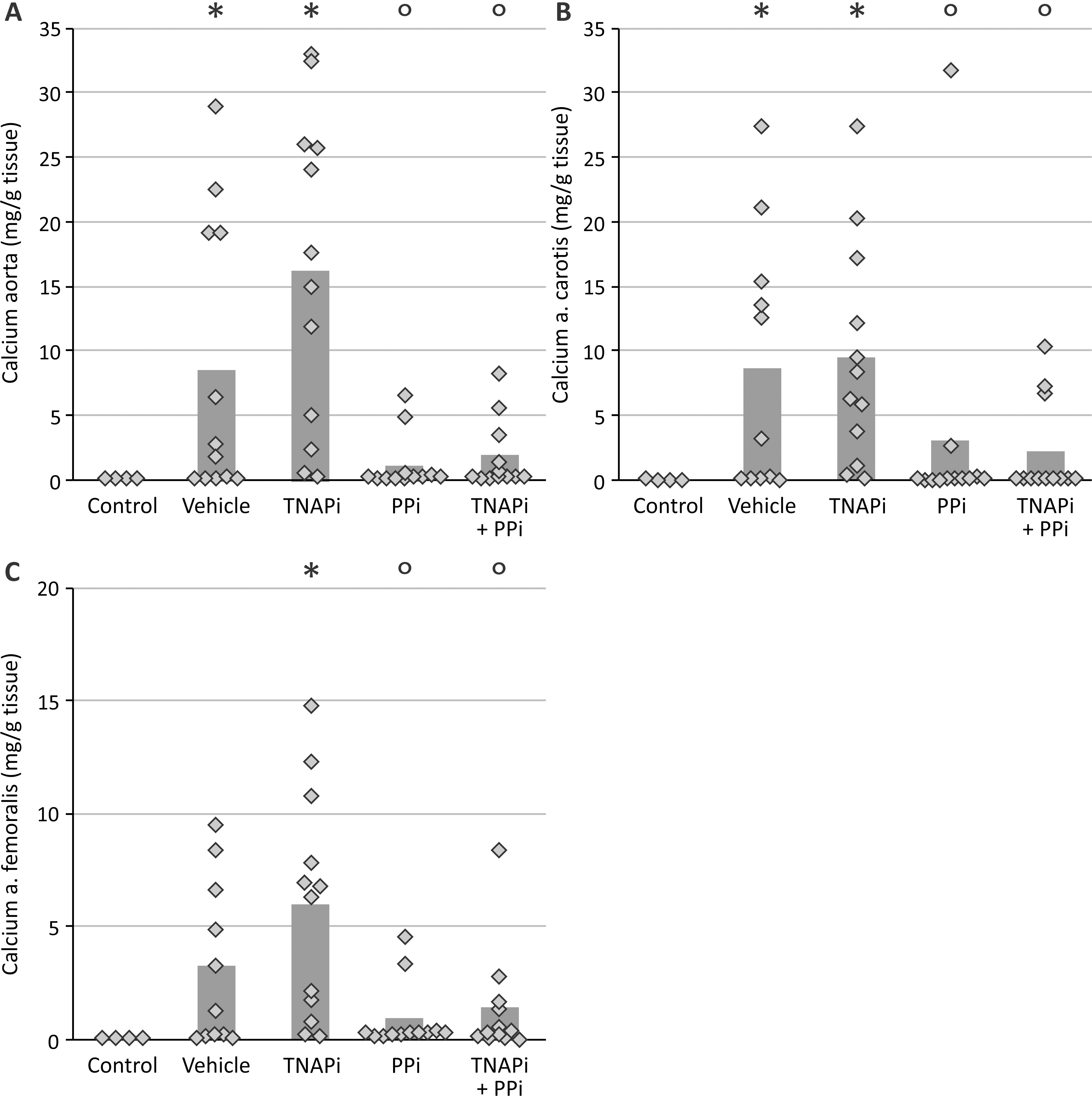

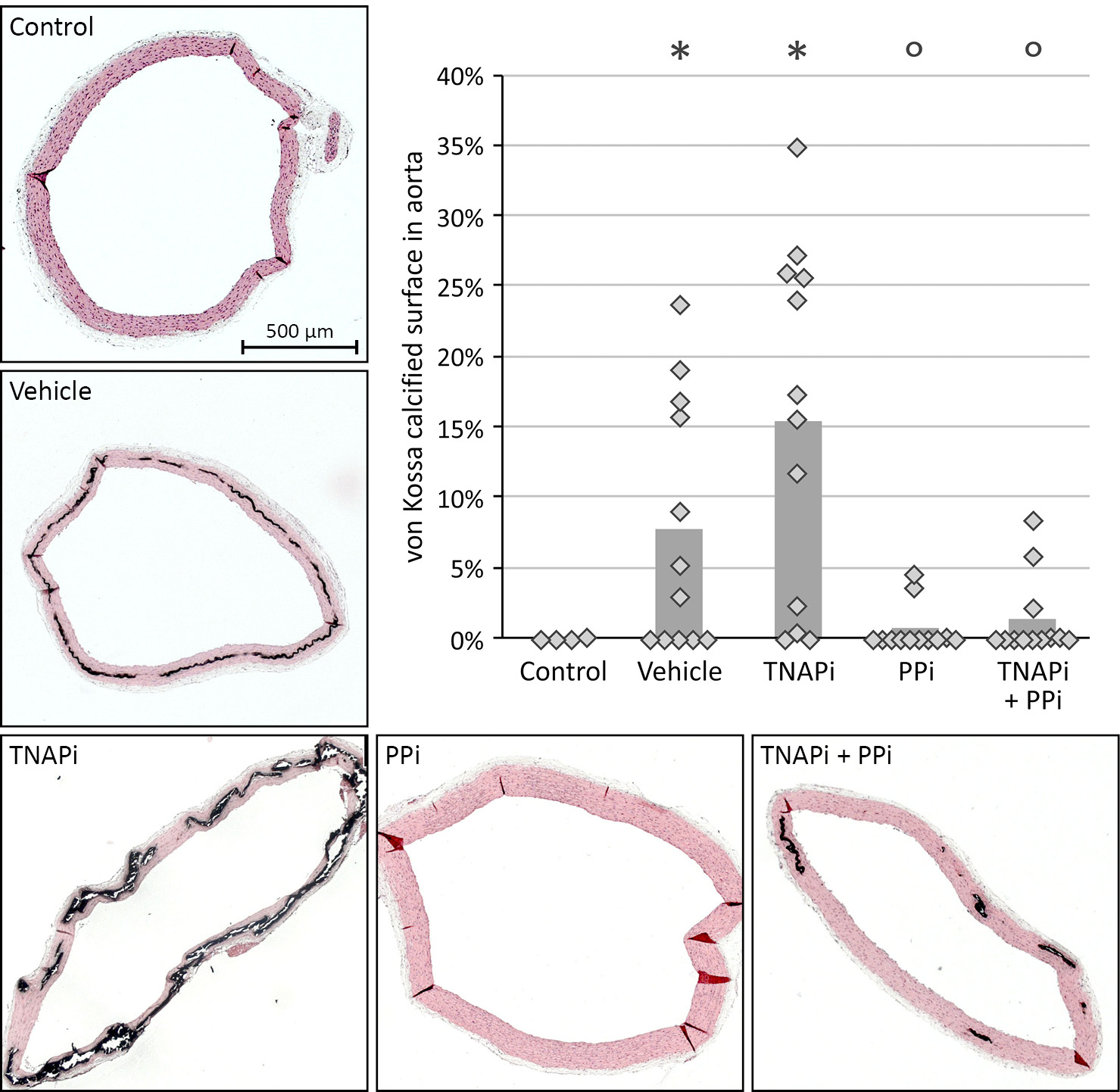

3.2. Administration of SBI-425 markedly reduces arterial media calcification

To examine the effect of SBI-425 treatment on vascular calcification, the calcium content in the aorta and smaller arteries was determined. Warfarin exposure resulted in distinct calcification in the aorta, carotid and femoral artery in vehicle treated rats. However, daily administration of SBI-425 significantly (p<0.001) reduced vascular calcification as indicated by a significant decrease of the calcium content in the aorta (3.84±0.64 to 0.70±0.23 mg/g wet tissue), carotid (1.46±0.32 to 0.28±0.04 mg/g wet tissue) and femoral (1.80±0.32 to 0.43±0.12 mg/g wet tissue) arteries (Figure 1 A–C). Normal values from healthy rats, age- (16 weeks old), sex- (male), and strain- (Wistar Han) matched, are represented in the graphs as shaded area to indicate normal values of calcium content in the aorta, carotid and femoral arteries. These results were reinforced by a significant reduction of the calcified area in the aorta of SBI-425 treated animals as determined on Von Kossa stained aortic sections. No Von Kossa positivity was found on the aortic section of all animals treated with SBI-425 (Figure 1 D). Von Kossa staining also showed that calcifications in vehicle treated rats were located in the medial layer of the aortic wall (Figure 2 A–B).

Figure 1: Evaluation of TNAP inhibitor treatment on calcification in the aorta and peripheral arteries.

Calcium content of the (A) aorta, (B) femoral artery, (C) carotid artery and (D) % calcified aortic area of rats treated with either vehicle or TNAP inhibitor. The bars represent the mean. The shaded area represents the normal values of rats without warfarin treatment (n=10). * P<0.001 versus vehicle. Vehicle (n=10), SBI-425 (n=10)

Figure 2: Visualization of the calcium-phosphate deposits in the aortic tissue.

Representative Von Kossa stained aortic sections of (A) vehicle and (B) TNAP inhibitor.

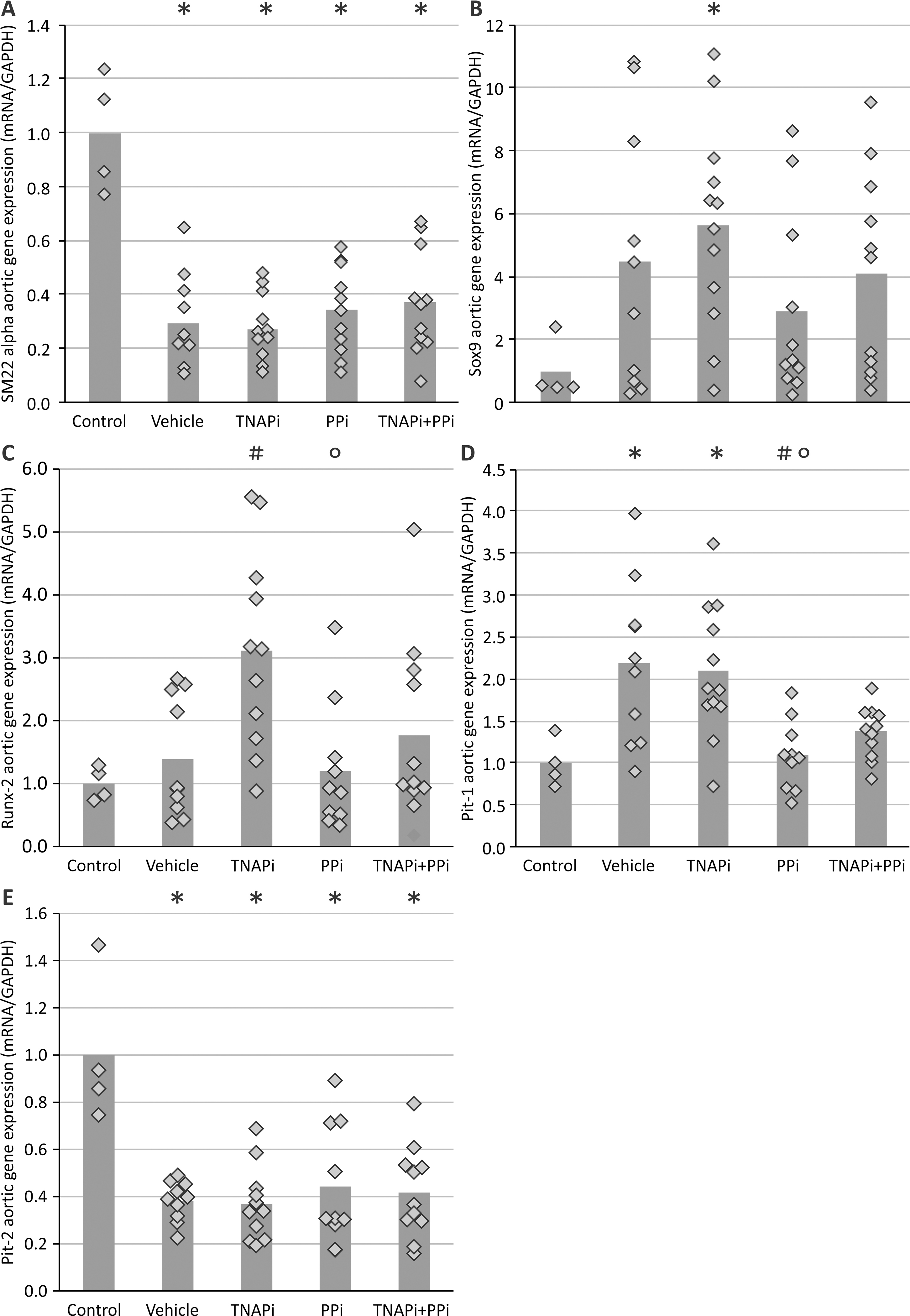

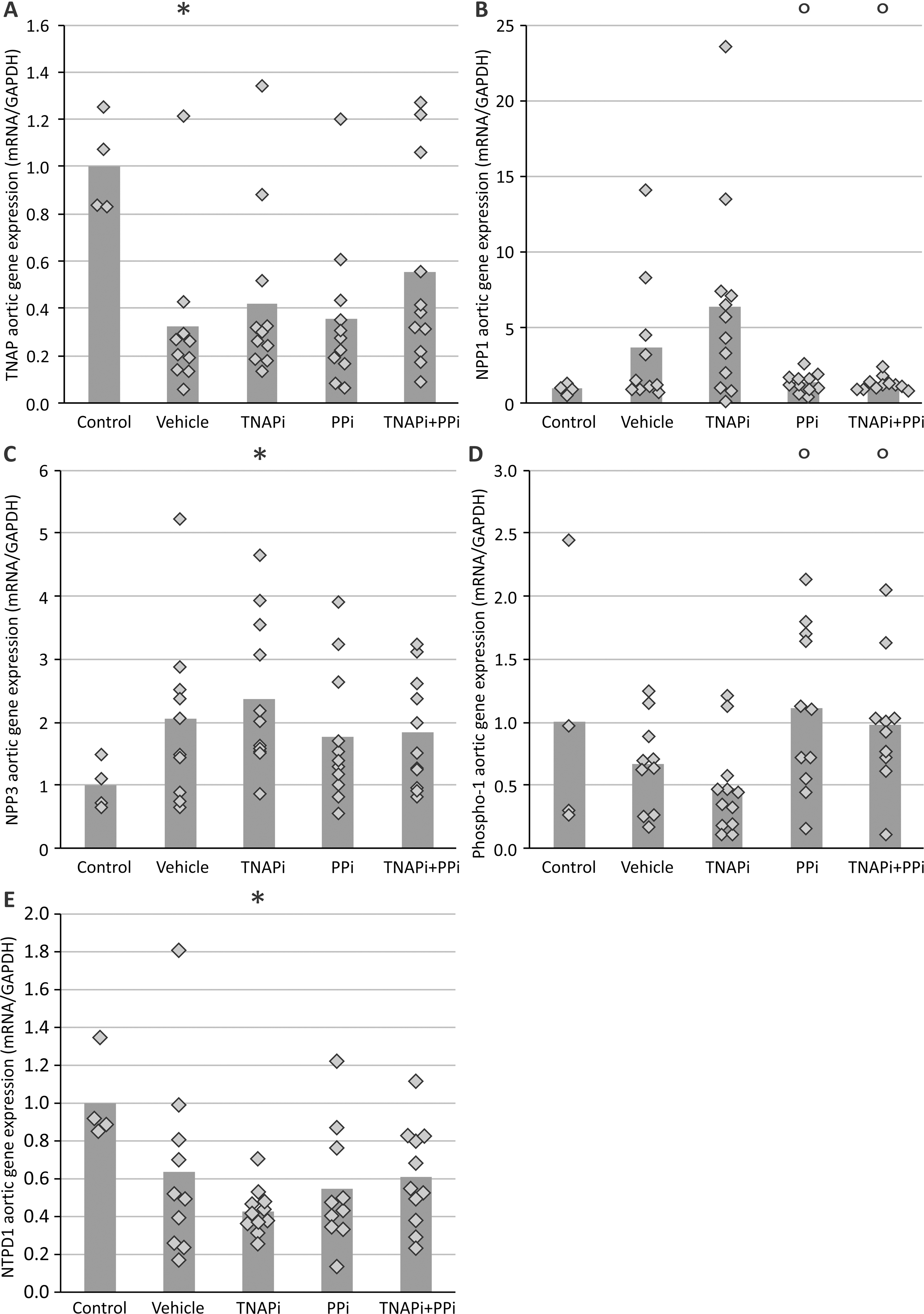

3.3. Administration of SBI-425 does not modulate aortic gene expression levels.

Investigating aortic mRNA levels, it became clear that treatment with SBI-425 did not alter the mRNA expression of osteo/chondrogenic marker genes runx2, TNAP, SOX9, collagen 1 and 2, nor MGP as compared to vehicle treatment (Table 2). Furthermore genes involved in the pyrophosphate/inorganic phosphate homeostasis, including NPP1, NPP3 and PHOSPHO1 also did not differ significantly between vehicle and SBI-425 treated warfarin rats (Table 2).

Table 2:

The mRNA expression of osteo/chondrogenic marker genes and genes involved in pyrophosphate/inorganic phosphate balance.

| Aortic gene expression (mRNA/GAPDH) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Vehicle | SBI-425 | Normal values | |

| TNAP | 1.00±0.15b | 1.01±0.35 | 2.78±0.48 |

| Runx2 | 1.00±0.40 | 0.66±0.22 | 1.09±0.73 |

| Collagen 1 | 1.00±0.64b | 0.80±0.42 | 1.63±0.31 |

| Collagen 2 | 1.00±0.32 | 1.08±0.43 | 1.20±0.24 |

| Sox 9 | 1.00±0.45 | 0.78±0.25 | 1.24±0.31 |

| MGP | 1.00±0.19 | 0.60±0.22 | 1.39±0.28 |

| NPP1 | 1.00±0.39 | 0.72±0.14 | 0.87±0.17 |

| 1.00±0.42 | 0.92±0.20 | 0.80±0.13 | |

| PHOSPHO1 | 1.00±0.35 | 0.76±0.27 | 0.97±0.44 |

TNAP: Tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase, Runx2: Runt-related transcription factor 2, Sox 9: SRY-box transcription factor 9, MGP: matrix Gla protein, NPP1 and NPP3: ectonucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase 1 and 3, PHOSPHO1: phosphoethanolamine/phosphocholine phosphatase 1. Mean ± SEM, vehicle (n=10), SBI-425 (n=10) and normal values (n=10).

p<0.05 versus normal values.

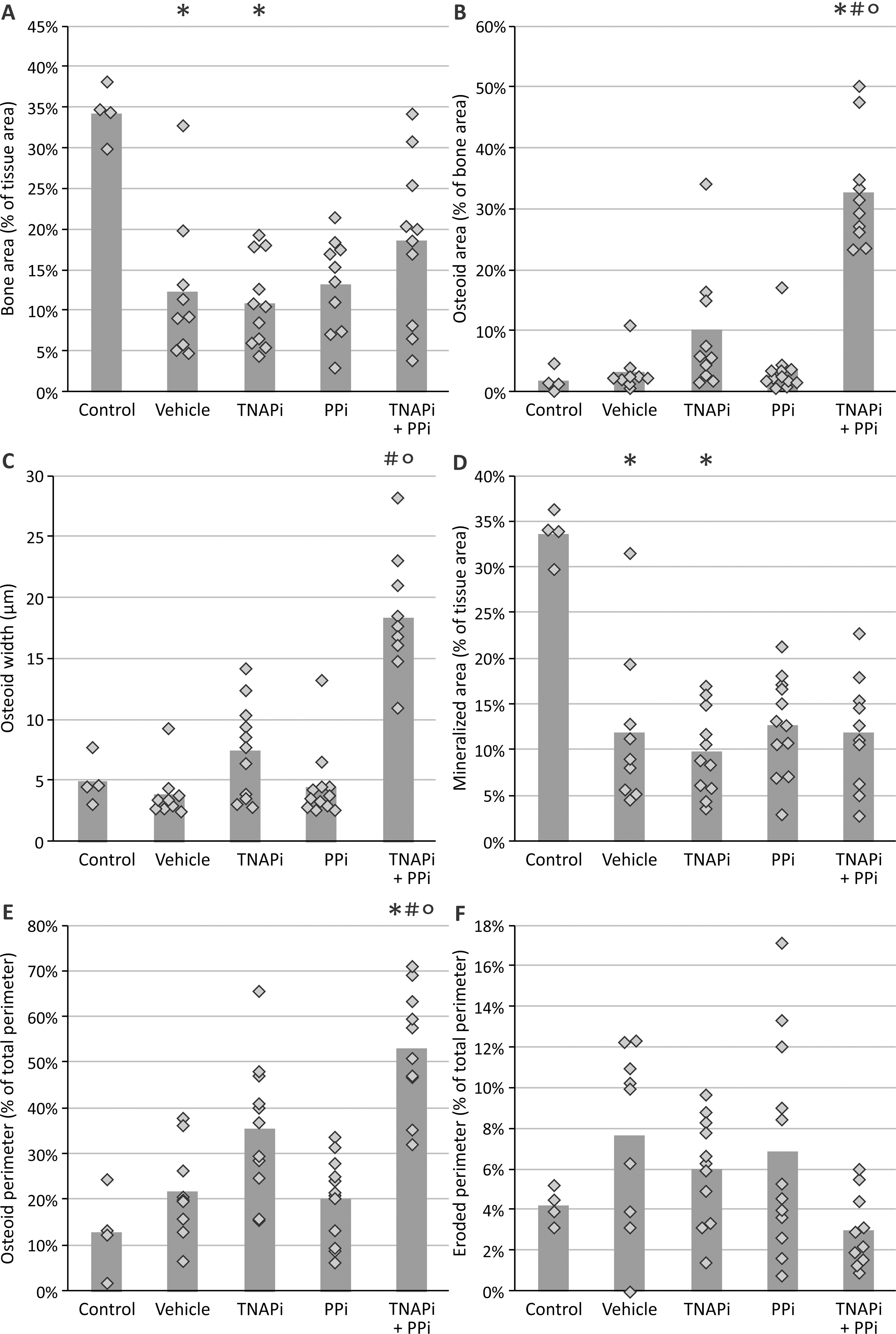

3.4. Administration of SBI-425 affects physiological bone metabolism

Due to the close relationship and mechanistic similarity between physiological bone formation and pathological vascular calcification, static and dynamic bone parameters were investigated in both vehicle and SBI-425 treated rats. Both static and dynamic bone parameters are represented in figure 3 and 4. Except for the osteoid width, no differences in static bone parameters were found between vehicle and SBI-425 treated animals. However, administration of SBI-425 had an effect on dynamic bone parameters as indicated by a significantly decreased bone formation and mineral apposition rate as well as a significantly increased osteoid maturation time as compared to vehicle treated animals. Normal values from healthy rats, age- (16 weeks old), sex- (male), and strain- (Wistar Han) matched, are represented in the graphs as shaded area to indicate normal values of static and dynamic bone parameters. Figure 5 shows Goldner stained sections of the tibia of both vehicle and SBI-425 treated rats. Goldner stained tibial sections demonstrate decreased osteoid area/-width in the trabecular bone of SBI-425 treated rats as compared to vehicle treatment.

Figure 3: Evaluation of administration of the TNAP inhibitor on static bone parameters.

(A) bone area, (B) mineralized area, (C) trabecular thickness, (D) eroded perimeter, (E) osteoid area, (F) osteoid width, (G) osteoblast perimeter and (H) osteoclast perimeter. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. * P<0.05 versus vehicle. The shaded area represents the normal values of rats without warfarin treatment (n=8). Vehicle (n=10), SBI-425 (n=10).

Figure 4: Evaluation of administration of the TNAP inhibitor on dynamic bone parameters.

(A) bone formation rate, (B) mineral apposition rate and (C) osteoid maturation time. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. * P<0.05 versus vehicle. The shaded area represents the normal values of rats without warfarin treatment (n=8). Vehicle (n=10), SBI-425 (n=10).

Figure 5: Visualization of bone health in the tibia.

Representative Goldner stained section of the tibia in (A) vehicle and (B) TNAP inhibitor treated rats. The arrows represent the osteoid.

4. Discussion

Vascular media calcification is an important aspect of cardiovascular disease with a high impact on quality of life and survival of patients suffering from it. To date, therapeutic options directly targeting the arterial media calcification process are not available. We consider TNAP as an important therapeutic target since several studies have shown that selective TNAP overexpression in either VSMCs or endothelial cells resulted in extensive vascular calcification, high blood pressure and cardiac hypertrophy [27,28,35]. To provide in vivo evidence for the therapeutic efficiency of selective pharmacological TNAP inhibition in the treatment of arterial media calcification, we evaluated the effect of SBI-425, a novel small molecule, on the development of arterial media calcification in an experimental model of warfarin-induced vascular media calcification. The present study revealed that daily treatment with the TNAP inhibitor SBI-425 for 7 weeks, at a daily dose of 10 mg/kg, resulted in a significant reduction of calcification in the aorta and peripheral arteries of rats with warfarin-induced vascular media calcification. Recently, the efficacy of TNAP inhibitor SBI-425 was also reported by two research groups who showed that SBI-425 attenuated both the development and progression of calcification in the vibrissae fibrous capsule of mice suffering from pseudoxanthoma elasticum [36,37].

Studies have shown that depletion of PPi caused by either TNAP overexpression in VSMCs or adding high levels of exogenous alkaline phosphatase to cell cultures stimulate the phenotypic switch of VSMC into bone-like cells [27,38]. Our findings show that administration of the pharmacological TNAP inhibitor did not influence mRNA levels of marker genes runx2, SOX9, TNAP, collagen 1 and 2 of this phenotypic switch. SBI-425 also did not affect MGP mRNA levels. Furthermore, in our study, no significant differences in aortic mRNA expression of genes controlling the pyrophosphate/inorganic phosphate homeostasis (NPP1, NPP3 and PHOSPHO1) were found between vehicle and TNAP inhibitor treated rats. NPP1 regulates pyrophosphate synthesis by hydrolysis of phosphodiester bonds with the release of pyrophosphate while NPP3 is suggested to stimulate degradation of pyrophosphate [20]. PHOSPHO1 is a phosphatase which mediates the generation of inorganic phosphate from phosphoethanolamine and phosphocholine [39]. In conclusion, gene expression studies suggest that SBI-425 exerts its inhibitory effect on arterial calcifications most likely through direct interference with calcium phosphorus crystal formation (inhibit phosphate supply) rather than through targeting the gene expression levels in aortic cells. As in the present study mRNA expression of the various genes under study was measured at sacrifice of the animals one cannot exclude that changes might have occurred between vehicle and SBI-425 treated rats during the onset of the calcifications which we consider as a limitation of the study.

Four types of alkaline phosphatase exist including three tissue-specific isozymes intestinal, placental and germ-cell alkaline phosphatase and one tissue-nonspecific isozyme, TNAP. In human plasma, 95% of the alkaline phosphatase activity is attributed to the TNAP isozyme [40]. In rats however, TNAP is not the major isozyme in serum (unpublished data of J.L. Millán) which might explain why in the present study a decrease in total serum alkaline phosphatase activity was not observed as result of SBI-425 administration. Aryl sulfonamides indeed have proven to be selective TNAP inhibitors [25]. Another reason could be that blood samples were taken 24 hours after SBI-425 injection, which might implicate that the inhibitory effect of SBI-425 on alkaline phosphatase activity already had disappeared.

Bone, liver and kidney are three main sources of TNAP [41]. Our results have shown that the TNAP inhibition is able to prevent the development of arterial media calcifications however awareness of possible side-effects in other tissues such as liver and bone is needed. TNAP expression in the liver has been linked to anti-inflammatory effects by dephosphorylation of the bacterial endotoxin lipopolysaccharide [42]. In the present study, we found no differences in serum AST and ALT levels, two liver enzymes which are elevated in liver failure, between vehicle and SBI-425 treated rats, indicating that administration of the TNAP inhibitor reduces vascular media calcification without affecting the liver function. In addition, it is important to evaluate to which extent administration of SBI-425 interfered with bone metabolism since (i) TNAP is a well-known biomarker for bone mineralization as it is released by osteoblasts to maintain the growth of crystals in the collagen matrix [43] and (ii) soft tissue calcification shares many features with physiological bone mineralization [44]. Results of the present study demonstrate that exposure to warfarin induced lower bone mass as reflected by a decrease in static bone parameters including bone and mineralized area, trabecular thickness, eroded perimeter and osteoid width. Osteoid width was further decreased in rats treated with SBI-425. All other static bone parameters were not statistically different between vehicle and SBI-425 treated rats. Previous reports found no alterations in static and dynamic bone parameters (i.e. bone volume, osteoid volume and growth rate) in the femur of mice treated with SBI-425, at oral doses of 10, 30 and 75 mg/kg/day [27,36,37,45]. We, however, found also with regard to dynamic bone parameters that administration of SBI-425 decreased bone formation rate and mineral apposition rate, and increased osteoid maturation time which strongly suggests that SBI-425 treatment goes along with an impaired bone formation/-mineralization and thus aggravates the already compromised bone in warfarin exposed rats. This indicates that it is important to take species differences into account during quantitative histomorphometric evaluation [46]. Rats are considered to be less resistant to effects on bone and have a bone structure highly similar to that of humans. Furthermore, a major limitation of using mice is the relative small size of trabecular bone compartment making accurate quantitative histomorphometric evaluation difficult [47]. Taken together, evaluation and interpretation of bone parameters in different species needs to be done with caution as exemplified by data of the present study in which in contrast to other studies [27,36,37,45], 10 mg/kg per day SBI-425 administration worsened the bone formation/-mineralization defects mediated by warfarin. Hence, the potential of SBI-425 to worsen the bone defects which are already present in CKD patients with adynamic bone disease and have a high risk for developing arterial media calcification needs to be considered [48]. Nevertheless, this result was rather unexpected since the basal TNAP activity of mineralizing osteoblasts is a hundred times higher as compared to that of VSMCs under pro-calcifying conditions [49], however shows that TNAP activity in our rats dosed with SBI-425 was efficiently inhibited. Furthermore, this result also confirms that vascular media calcification and bone pathology are closely related hampering the development of effective compounds for the treatment of arterial media calcification that do not negatively affect physiological bone mineralization.

Taken together, daily treatment with 10 mg/kg/day SBI-425 inhibited arterial media calcification however, also decreased bone formation/-mineralization. Furthermore the current study investigated effects on FGF23 and PTH levels. Warfarin exposure induced small increases in FGF23 levels as compared to control rats, which may be the reason why serum phosphate homeostasis was maintained in the presence of a by warfarin altered bone metabolism. However, no difference in PTH and FGF23 concentrations between vehicle and SBI-425 treated rats were found, suggesting that SBI-425 probably induced direct effects on physiological bone metabolism and thus without exerting an effect on calcium or phosphate regulating hormones. These findings demand further investigation on the potential therapeutic use of SBI-425 as an anti-calcification agent, in particular in the setting of a severe disturbed bone metabolism such as CKD or osteoporosis. For the purpose of this, the use of the adenine rat model with stable CKD, moderate vascular calcification and high bone turnover disease as reported by Neven et al., might be of particular interest [50].

This study has some limitations. First, mRNA levels where only measured at the end of the study. This, together with the technical issue that blood samples were taken 24h after SBI-425 administration and the fact that TNAP is not the most important alkaline phosphatase isoenzyme in rat serum does not allow us to draw a clear-cut conclusion on the mechanism of action. A second limitation is that only a single dosage of SBI-425 was evaluated. Future studies are needed to evaluate whether lower dosages are able to inhibit arterial media calcification without affecting bone mineralization.

In conclusion, TNAP is an effective therapeutic target to treat vascular media calcification as administration of TNAP inhibitor SBI-425 led to a significant reduction of the calcifications in the aorta and peripheral arteries of rats exposed to a warfarin diet. Further studies using specific disease models are demanded to further substantiate the therapeutic potential of TNAP inhibitor SBI-425 and establish the optimal dose at which a beneficial effect on arterial media calcification is maintained without exerting a deleterious effect on bone health.

Supplementary Material

6. Acknowledgements

E.N. is a postdoctoral fellow of the Fund for Scientific Research-Flanders (FWO). B.O. is a PhD fellow of the FWO. We especially thank Geert Dams, Hilde Geryl, Ludwig Lamberts, Rita Marynissen and Simonne Dauwe for their excellent technical assistance, and Dirk De Weerdt for his help with the graphics. We also thank Nina Jansoone for her help with the auto-analyzer at the Antwerp University Hospital.

7. Funding

This work was supported by the Fund of Scientific Research-Flanders (FWO) grant number 1S22217N.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

A.B.P. and J.L.M. are co-inventors on a patent application covering SBI-425 (PCT WO 2013126608). B.O., A.V., P.D.H. and E.N. have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Cho IJ; et al. Aortic calcification is associated with arterial stiffening, left ventricular hypertrophy, and diastolic dysfunction in elderly male patients with hypertension. J. Hypertens 2015, 33, 1633–1641, doi: 10.1097/hjh.0000000000000607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tölle M; Reshetnik A; Schuchardt M; Höhne M; van der Giet M Arteriosclerosis and vascular calcification: causes, clinical assessment and therapy. Eur. J. Clin. Investig 2015, 45, 976–985, doi: 10.1111/eci.12493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mizobuchi M; Towler D; Slatopolsky E Vascular calcification: the killer of patients with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009, 20, 1453–1464, doi: 10.1681/asn.2008070692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodman WG; et al. Coronary-artery calcification in young adults with end-stage renal disease who are undergoing dialysis. N. Engl. J. Med 2000, 342, 1478–1483, doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005183422003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Schutter TM; et al. Effect of a magnesium-based phosphate binder on medial calcification in a rat model of uremia. Kidney Int. 2013, 83, 1109–1117, doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neven E; et al. Adequate phosphate binding with lanthanum carbonate attenuates arterial calcification in chronic renal failure rats. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2009, 24, 1790–1799, doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peng T; Zhuo L; Wang Y; Jun M; Li G; Wang L; Hong D Systematic review of sodium thiosulfate in treating calciphylaxis in chronic kidney disease patients. Nephrology (Carlton) 2018, 23, 669–675, doi: 10.1111/nep.13081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leopold JA Vascular calcification: Mechanisms of vascular smooth muscle cell calcification. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2015, 25, 267–274, doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2014.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Speer MY; et al. Smooth muscle cells give rise to osteochondrogenic precursors and chondrocytes in calcifying arteries. Circ. Res. 2009, 104, 733–741, doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.183053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Villa-Bellosta R; Sorribas V Calcium phosphate deposition with normal phosphate concentration. -Role of pyrophosphate. Circ. J. 2011, 75, 2705–2710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Neill WC The fallacy of the calcium-phosphorus product. Kidney Int. 2007, 72, 792–796, doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fleisch H; Russell RG; Straumann F Effect of pyrophosphate on hydroxyapatite and its implications in calcium homeostasis. Nature 1966, 212, 901–903, doi: 10.1038/212901a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Neill WC; Sigrist MK; McIntyre CW Plasma pyrophosphate and vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2010, 25, 187–191, doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lomashvili KA; Khawandi W; O’Neill WC Reduced plasma pyrophosphate levels in hemodialysis patients. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2005, 16, 2495–2500, doi: 10.1681/asn.2004080694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schibler D; Russell RG; Fleisch H Inhibition by pyrophosphate and polyphosphate of aortic calcification induced by vitamin D3 in rats. Clin. Sci. 1968, 35, 363–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Neill WC; Lomashvili KA; Malluche HH; Faugere MC; Riser BL Treatment with pyrophosphate inhibits uremic vascular calcification. Kidney Int. 2011, 79, 512–517, doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Oliveira RB; et al. Peritoneal delivery of sodium pyrophosphate blocks the progression of pre-existing vascular calcification in uremic apolipoprotein-E knockout mice. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2015, 97, 179–192, doi: 10.1007/s00223-015-0020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lomashvili KA; Cobbs S; Hennigar RA; Hardcastle KI; O’Neill WC Phosphate-induced vascular calcification: role of pyrophosphate and osteopontin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol 2004, 15, 1392–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rathan S; Yoganathan AP; O’Neill CW The role of inorganic pyrophosphate in aortic valve calcification. J. Heart Valve Dis. 2014, 23, 387–394. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Villa-Bellosta R; Wang X; Millan JL; Dubyak GR; O’Neill WC Extracellular pyrophosphate metabolism and calcification in vascular smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol 2011, 301, H61–68, doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01020.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moe SM; Duan D; Doehle BP; O’Neill KD; Chen NX Uremia induces the osteoblast differentiation factor Cbfa1 in human blood vessels. Kidney Int. 2003, 63, 1003–1011, doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shroff RC; et al. Dialysis accelerates medial vascular calcification in part by triggering smooth muscle cell apoptosis. Circulation 2008, 118, 1748–1757, doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.783738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shanahan CM; et al. Medial localization of mineralization-regulating proteins in association with Monckeberg’s sclerosis: evidence for smooth muscle cell-mediated vascular calcification. Circulation 1999, 100, 2168–2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kozlenkov A; et al. Residues determining the binding specificity of uncompetitive inhibitors to tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase. J. Bone Miner. Res 2004, 19, 1862–1872, doi: 10.1359/jbmr.040608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dahl R; et al. Discovery and validation of a series of aryl sulfonamides as selective inhibitors of tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP). J. Med. Chem 2009, 52, 6919–6925, doi: 10.1021/jm900383s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pinkerton AB; et al. Discovery of 5-((5-chloro-2-methoxyphenyl)sulfonamido)nicotinamide (SBI-425), a potent and orally bioavailable tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP) inhibitor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2018, 28, 31–34, doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sheen CR; et al. Pathophysiological role of vascular smooth muscle alkaline phosphatase in medial artery calcification. J. Bone Miner. Res 2015, 30, 824–836, doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romanelli F; et al. Overexpression of tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP) in endothelial cells accelerates coronary artery disease in a mouse model of familial hypercholesterolemia. PloS one 2017, 12, e0186426, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li T; et al. Identification of the gene for vitamin K epoxide reductase. Nature 2004, 427, 541–544, doi: 10.1038/nature02254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Mare A; et al. Sclerostin as Regulatory Molecule in Vascular Media Calcification and the Bone-Vascular Axis. Toxins 2019, 11, doi: 10.3390/toxins11070428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Price PA; Faus SA; Williamson MK Warfarin causes rapid calcification of the elastic lamellae in rat arteries and heart valves. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 1998, 18, 1400–1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kruger T; et al. Warfarin induces cardiovascular damage in mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 2013, 33, 2618–2624, doi: 10.1161/atvbaha.113.302244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bowers GN Jr.; McComb RB A continuous spectrophotometric method for measuring the activity of serum alkaline phosphatase. Clin. Chem 1966, 12, 70–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dempster DW; et al. Standardized nomenclature, symbols, and units for bone histomorphometry: a 2012 update of the report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2013, 28, 2–17, doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Savinov AY; et al. Transgenic Overexpression of Tissue-Nonspecific Alkaline Phosphatase (TNAP) in Vascular Endothelium Results in Generalized Arterial Calcification. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2015, 4, doi: 10.1161/JAHA.115.002499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ziegler SG; et al. Ectopic calcification in pseudoxanthoma elasticum responds to inhibition of tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aal1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li Q; et al. Inhibition of Tissue-Nonspecific Alkaline Phosphatase Attenuates Ectopic Mineralization in the Abcc6(−/−) Mouse Model of PXE but Not in the Enpp1 Mutant Mouse Models of GACI. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2019, 139, 360–368, doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.07.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fakhry M; et al. TNAP stimulates vascular smooth muscle cell trans-differentiation into chondrocytes through calcium deposition and BMP-2 activation: Possible implication in atherosclerotic plaque stability. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2017, 1863, 643–653, doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2016.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stonich D; et al. The Role of PHOSPHO1 in the Initiation of Skeletal Calcification. In Probe Reports from the NIH Molecular Libraries Program, National Center for Biotechnology Information (US): Bethesda (MD), 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Magnusson P; Degerblad M; Saaf M; Larsson L; Thoren M Different responses of bone alkaline phosphatase isoforms during recombinant insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) and during growth hormone therapy in adults with growth hormone deficiency. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1997, 12, 210–220, doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Millán JL Alkaline Phosphatases : Structure, substrate specificity and functional relatedness to other members of a large superfamily of enzymes. Purinergic Signal 2006, 2, 335–341, doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-5435-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pike AF; Kramer NI; Blaauboer BJ; Seinen W; Brands R A novel hypothesis for an alkaline phosphatase ‘rescue’ mechanism in the hepatic acute phase immune response. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1832, 2044–2056, doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Millán JL The role of phosphatases in the initiation of skeletal mineralization. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2013, 93, 299–306, doi: 10.1007/s00223-012-9672-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Persy V; D’Haese P Vascular calcification and bone disease: the calcification paradox. Trends Mol. Med. 2009, 15, 405–416, doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tani T; et al. Inhibition of tissue-nonspecific alkaline phosphatase protects against medial arterial calcification and improves survival probability in the CKD-MBD mouse model. J. Pathol. 2020, 250, 30–41, doi: 10.1002/path.5346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Opdebeeck B; D’Haese PC; Verhulst A Inhibition of tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase, a novel therapy against arterial media calcification? J. Pathol. 2019, 10.1002/path.5377, doi: 10.1002/path.5377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Allen MR Preclinical Models for Skeletal Research: How Commonly Used Species Mimic (or Don’t) Aspects of Human Bone. Toxicol Pathol 2017, 45, 851–854, doi: 10.1177/0192623317733925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bover J; et al. Adynamic bone disease: from bone to vessels in chronic kidney disease. Semin Dial 2014, 34, 626–640, doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Patel JJ; et al. Inhibition of arterial medial calcification and bone mineralization by extracellular nucleotides: The same functional effect mediated by different cellular mechanisms. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233, 3230–3243, doi: 10.1002/jcp.26166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Neven E; et al. Disturbances in Bone Largely Predict Aortic Calcification in an Alternative Rat Model Developed to Study Both Vascular and Bone Pathology in Chronic Kidney Disease. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2015, 10.1002/jbmr.2585, doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.