Abstract

Background

Asthma education and self‐management are key recommendations of asthma management guidelines because they improve health outcomes. There are several different modalities for the delivery of asthma self‐management education.

Objectives

We evaluated programmes that: (1) Optimised asthma control through inhaled corticosteroid use by regular medical review or optimised asthma control by individualised written action plans; (2) Used written self‐management plans based on peak expiratory flow self‐monitoring compared with symptom self‐monitoring; (3) Compared different options for the delivery of optimal self‐management programmes.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Airways Group trials register and reference lists of articles.

Selection criteria

Randomised trials of asthma self‐management education interventions in adults over 16 years of age with asthma.

Data collection and analysis

Fifteen trials met the inclusion criteria. Trial quality was assessed and data were extracted independently by two reviewers. Study authors were contacted for confirmation.

Main results

Six studies compared optimal self‐management allowing self‐adjustment of medications according to an individualised written action plan to adjustment of medications by a doctor. These two styles of asthma management gave equivalent effects for hospitalisation, emergency room (ER) visits, unscheduled doctor visits and nocturnal asthma. Self‐management using a written action plan based on peak expiratory flow (PEF) was found to be equivalent to self‐management using a symptoms based written action plan in the six studies which compared these interventions. Three studies compared self‐management options. In one, that provided optimal therapy but tested the omission of regular review, the latter was associated with more health centre visits and sickness days. In another, comparing high and low intensity education, the latter was associated with more unscheduled doctor visits. In a third, no difference in health care utilisation or lung function was reported between verbal instruction and written action plans.

Authors' conclusions

Optimal self‐management allowing for optimisation of asthma control by adjustment of medications may be conducted by either self‐adjustment with the aid of a written action plan or by regular medical review. Individualised written action plans based on PEF are equivalent to action plans based on symptoms. Reducing the intensity of self‐management education or level of clinical review may reduce its effectiveness.

Keywords: Adult, Humans, Patient Education as Topic, Anti‐Asthmatic Agents, Anti‐Asthmatic Agents/therapeutic use, Asthma, Asthma/drug therapy, Asthma/physiopathology, Peak Expiratory Flow Rate, Self Care, Self Care/methods

Plain language summary

Options for self‐management education for adults with asthma

Guidelines for the treatment of asthma recommend that patients be educated about their condition, obtain regular medical review, monitor their condition at home with either peak flow or symptoms and use a written action plan. This is known to improve health outcomes when compared to usual medical care. A number of variations on optimal self‐management have now been described. This review examines the efficacy of some of these options. The results showed that self‐adjustment of medications according to a written action plan gave a similar improvement in health outcomes to adjustment of medications by a doctor. Either symptom diaries or peak expiratory flow monitoring may be used for monitoring asthma and reducing the intensity of the education appears to dilute the effect.

Background

Asthma education and self‐management is a key recommendation of many asthma management guidelines, including Part 1 of the Six‐Part Asthma Management Program proposed by the International Consensus Report on diagnosis and Treatment of Asthma (Anonymous 1992). Education is considered to be necessary "to help patients gain the motivation, skills and confidence to control their asthma" (Anonymous 1996). A narrative review of asthma education has emphasised the need for asthma education and suggested successful strategies (Clark 1993).

Two Cochrane systematic reviews have previously been conducted examining the effects of education only (Gibson 1998) and more complex interventions to develop self‐management skills (Gibson 1999) on asthma health outcomes. Four main components of asthma education were identified: information, self monitoring of peak flow or symptoms, regular medical review and individualised written action plans. Information, was found to have no significant effect on health outcomes when administered without an action plan, self‐monitoring or regular review. In contrast, comparing the review of asthma self‐management education to usual care concluded that education programmes which included self monitoring of symptoms or peak expiratory flow, regular medical review and written action plans improved health outcomes for adults with asthma. Self‐management education led to reduced hospitalisations, emergency room (ER) visits, unscheduled doctor visits and improved quality of life.

There are several different modalities available for the delivery of asthma self‐management education. In the published studies, there is variation in the mode of delivery and the combination of components for the self‐management programmes. Information delivery was interactive or non‐interactive; self‐monitoring involved either symptoms or peak flow self‐monitoring which was sometimes recorded in a diary. In some studies regular review was conducted as a formal part of the intervention, whereas in others subjects were told to see their own doctor. Asthma action plans were written or verbal. This review aims to compare the differing components of self‐management interventions in asthma.

Objectives

The specific questions addressed are: (1) Is optimisation of asthma control through the use of inhaled corticosteroid treatment, by regular medical review, equivalent to optimisation of asthma control by an individualised written self‐management plan in improving health outcomes? (2) Are there differences in health outcomes for programmes using written self‐management plans based on peak expiratory flow self‐monitoring and symptom self‐monitoring? (3) What are the characteristics of optimal self‐management programme delivery, which lead to changes in health outcomes?

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Studies were included if they were randomised controlled trials (RCTs) which compared two interventions of asthma education and self‐management on health outcomes in adults with asthma.

Types of participants

Predominantly adults (>16 years old) with asthma (defined by doctor's diagnosis or objective criteria or according to American Thoracic Society guidelines).

Types of interventions

The interventions were categorised according to whether or not they involved a written action plan, regular medical review, self‐monitoring of peak expiratory flow or symptoms and/or asthma education. The intervention was considered optimal if all these components were included.

INTERVENTION CHARACTERISTICS

Patient Asthma Education: a programme which transfers information about asthma in any of these forms: written, verbal, visual or audio. It may be interactive or non‐interactive, structured or unstructured. Minimal education is characterised by the provision of written material alone or the conduct of a short unstructured verbal interaction between a health provider and a patient where the primary goal is to improve patient knowledge and understanding of asthma. Maximal education is considered to be structured with the use of both interactive and non‐interactive modes of information transfer. The content of the education must be related to asthma and its management.

Self‐monitoring: characterised by the regular measurement of either peak expiratory flow or symptoms. It is further characterised by the recording (or not) of those measurements in a diary.

Regular Review: characterised by regular consultation with a doctor during the intervention period for the purpose of reviewing the patients' asthma status and medications. This may occur either as a formal part of the intervention or the patients may be advised to see their own doctor on a regular basis. Interventions are classified as having 'regular review' either inside the programme (if the patients were seen as a part of the program) or outside the programme (if the patients were merely advised to seek regular medical review).

Written Action Plan: an individualised written plan produced for the purpose of patient self‐management of asthma exacerbations. The action plan is characterised by being individualised to the patient's underlying asthma severity and treatment. It is further characterised by being a written plan which informs participants about: (1) when and how to modify medications in response to worsening asthma; and (2) how to access the medical system in response to worsening asthma.

Types of outcome measures

Any of the following outcomes: asthma admissions, ER visits, doctor visits, days lost from work or school, lung function (FEV1), peak expiratory flow (PEF), use of rescue beta‐agonists, courses of oral corticosteroids, symptom scores, quality of life scores.

Search methods for identification of studies

Cochrane Airways Group trial register derived from MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, hand searched respiratory journals and meeting abstracts. We searched the register using the following terms: (Asthma OR wheez*) AND (education* OR self management OR self‐management).

We obtained the articles, and searched their bibliographic lists for additional articles.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently coded studies into three categories based upon the abstract/key word/title: (1) RCT, adult, asthma, education (2) Possible RCT but cannot determine from abstract (3) Exclude: non‐RCT or CCT, paediatric age range, doctor education. Full text versions of the articles were examined for studies in category (1) & (2) in order to define if the study met the inclusion criteria of a trial of two asthma education and self‐management interventions.

Two investigators independently categorised study eligibility, study quality and intervention type. Agreement was examined and disagreement resolved by consensus.

Data extraction and management

We included articles if they were randomised controlled trials of two (or more) self‐management asthma education interventions delivered to adults (>16 years) with asthma, and that reported relevant health outcomes: hospitalisations, visits to medical practitioner, visits to emergency room, use of beta‐agonists, lung functions, quality of life, symptoms score, symptoms or peak expiratory flow diary.

We assessed the following health outcomes:

Hospital admissions

Emergency room visits

Uscheduled doctor visits

Days lost from work or school

Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second (FEV1)

Peak Expiratory Flow (PEF)

Use of 'rescue' (or reliever) medications

Quality of life, symptoms scores, symptom/peak flow diary

Economic data cost, days lost from college/work.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two reviewers independently assessed the quality of the full text versions of all included papers using the Cochrane system. Study quality was assessed according to the following criteria:

CONCEALMENT OF ALLOCATION: A: ADEQUATE if there was true randomisation, i.e. a central randomisation scheme, randomisation i.e. external person or use of coded containers/ envelopes; B: UNCLEAR C: INADEQUATE if there was alternate allocation, reference to case record number, date of birth, day of the week, or an open list of random numbers;

Additional quality variables recorded were:

Blinding of interventions

Withdrawals/ dropouts

Blinding of outcome assessment

Studies were also assessed using the scale described by Jadad 1996.

Data synthesis

We analysed outcomes as continuous and/or dichotomous variables, using standard statistical techniques.

For continuous outcomes, the weighted mean difference or standardised mean difference with 95% confidence intervals were calculated as appropriate.

For dichotomous outcomes, the relative risk was calculated with 95% confidence interval. We examined heterogeneity using a Chi‐squared test and explored the reasons for heterogeneity where appropriate.

Three primary comparisons based on the treatment of the intervention and comparison groups were performed. They were:

Optimal Self‐Management versus Regular Medical Review. Here we sought to compare two interventions which optimised asthma control through the use of inhaled corticosteroid treatment with dose adjustment, either by active regular medical review or an individualised written self‐management plan, where dose adjustment was based on peak expiratory flow or symptoms.

Peak Expiratory Flow Based versus Symptom Based Self‐Management. These trials compared individualised written action plans where inhaled corticosteroid dose adjustment was made on peak expiratory flow to action plans where dose adjustment was made on symptoms.

Optimal Self‐Management versus Modified Optimal Self‐Management. In this comparison various options for delivery of optimal self‐management were compared. These options included verbal versus written action plan; intensive education versus reduced education; regular review versus no regular review.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The results of 15 randomised controlled trials that compared different types of self‐management education in asthma, compared to alternative strategies, are reported in this review. The search identified 101 papers describing 87 potentially relevant studies of asthma education in adults. Full text versions of these papers were obtained and independently assessed by two reviewers. Nineteen papers describing 15 randomised controlled trials met the inclusion criteria for this review. Three trials are either awaiting assessment (n = 1) or ongoing (n = 2).

Included studies

Twenty‐six asthma self‐management interventions were described in the 15 studies. Eleven trials compared two interventions. The content of these interventions included: (1) asthma education (n = 26, 100%) (2) self‐monitoring of symptoms and/or peak expiratory flow (n = 26, 100%) (3) regular review of treatment and asthma severity by a medical practitioner (n = 25, 96%) (4) written action plan (n = 23, 88%).

CONTROL COMPARISONS

Seven studies used control comparisons. Three of these were in addition to the two active intervention groups. In one trial (Cote 2001) the control group was not randomised and therefore only data from the two active interventions were used in this review. In two trials (Cote 1997, Cowie 1997) the control comparisons were examined in the companion review comparing self management to usual care. In the remaining four studies, the management of the control patients included regular medical review. Education about asthma was included in two studies, self‐monitoring was performed by control subjects in one study. None of the control groups received a written action plan.

COMPARISONS

Three primary comparisons were made: (1) Optimal Self‐Management versus Regular Medical Review (Table 1) Six studies compared optimal self‐management, allowing self‐adjustment of medications according to an individualised written action plan, with adjustment of medications by a doctor. Four studies optimised medications in both intervention and comparison groups during the run‐in phase prior to commencing the intervention.

1. Intervention Characteristics.

| Optimal vs RR | PEF vs Symp | |

| n = 6 | n = 6 | |

| Intervention | Intervention | |

| 1 2 | 1 2 | |

| Education | Yes Yes | Yes Yes |

| Self Monitoring: PEF | Yes Yes | Yes No |

| Self Monitoring: Symptoms | No No | No Yes |

| Regular Review | Yes Yes | Yes Yes |

| Written Action Plan | Yes No | Yes Yes |

(2) PEF Self‐Management versus Symptoms Self‐Management (Table 1) Six studies compared peak expiratory flow with symptoms only self‐management. These studies allowed for self‐adjustment of medications in the event of worsening of asthma according to either symptoms or peak flow.

(3) Optimal Self‐Management versus Modified Optimal Self‐Management (Table 2) In three studies, self‐management which included education, self‐monitoring, regular medical review and a written action plan (optimal self‐management) was compared to modifications of optimal self‐management. These options included: verbal instructions instead of a written action plan (Baldwin 1997); reduced education (Cote 2001); no regular review (Kauppinen 1998).

2. Characteristics of Modified Interventions.

| Baldwin 1997 | Cote 2001 | Kauppinen 1998 | |

| Intervention | Intervention | Intervention | |

| 1 2 | 1 2 | 1 2 | |

| Education | Yes Yes | Yes No | Yes Yes |

| Reduced Education | No No | No Yes | No No |

| Self Monitoring: PEF | Yes Yes | Yes Yes | Yes Yes |

| Self Monitoring: Symptoms | No No | Yes Yes | No No |

| Regular Review | Yes Yes | Yes Yes | Yes No |

| Written Action Plan | Yes No | Yes Yes | Yes Yes |

| Verbal Action Plan | No Yes | No No | No No |

SUBJECTS/SETTING

In the 15 included studies a total number of 2460 participants were randomised. Fourteen studies reported 1824 subjects completed but one study (Charlton 1990) did not state the number participating at the end of the study. The reported dropout rates ranged from 0% ‐ 60.3%.

Subjects were recruited from a range of settings: (1) Hospital (n = 1) (2) Emergency Room (n = 2) (3) Hospital and Clinic (n = 2) (4) Outpatients Clinic (n = 3) (5) Outpatients Clinic and General Practice (n = 2) (6) General Practice (n = 3) (7) Emergency Room and Outpatients Clinic (n = 1) (8) Primary Care Setting (n = 1)

Excluded studies

Sixty‐nine studies were excluded for the following reasons: the subjects had smoking‐related chronic obstructive airway disease and not asthma (2); the methodological criteria were not met (11); background data only reported (2); the intervention did not include education (7) or was assessing inhaler technique only (3); the outcome measured was not appropriate (2); the interventions were not patient education (2); the interventions were compared with usual care (30) or the interventions were information‐only education and did not include elements of self‐management or behavioural change (10). The information‐only trials were reported in a previous review (Gibson 1998) and the comparisons of self‐management with usual care form the basis of a second review (Gibson 1999).

Risk of bias in included studies

The quality of studies varied with the Jadad score ranging from 3 to 5. Due to the type of intervention no study was double blinded. Only five trials were able to be scored as adequate for the Cochrane system of allocation concealment with the remainder scored as unclear from the data available. No trial was considered inadequate.

Effects of interventions

OUTCOMES: COMPARISON 1: OPTIMAL SELF‐MANAGEMENT versus REGULAR MEDICAL REVIEW (n = 6 trials)

In six trials a comparison was made between two forms of adjustment of medication, usually inhaled corticosteroids, to achieve improved asthma control. The usual means was by regular review by a doctor. This was contrasted with self‐adjustment by the patient according to written, pre‐determined criteria. There was no difference in asthma outcomes between the two forms of asthma management.

Hospitalisations for asthma were reported in four of the six studies. No difference between groups was reported. ER visits were reported in one study, which stated that there was no difference between treatments (Sommaragua 1995). Unscheduled doctor visits were examined in three studies. One study reported a non‐significant effect favouring regular review (Grampian 1994), another a non‐significant effect favouring peak expiratory flow self‐management (Lahdensuo 1996) and the third found no significant difference between the groups (Klein 2001). Days off work or school were examined in three studies. Two reported no significant difference between groups while the third reported a significant difference favouring peak flow self‐management (Lahdensuo 1996). Three of the six studies measured nocturnal asthma with different symptom scores reporting no difference between the two styles of asthma management and a third study found no significant difference in the mean percentage of symptom free nights between the groups. One study examined disrupted days and reported no significant differences (Jones 1995).

LUNG FUNCTION

Three studies reported mean FEV1 allowing us to undertake a meta‐analysis which favoured self‐management, although the pooled result was not statistically significant (SMD 0.10 95% CI ‐0.05 to 0.25, Analysis 1.1). There was a high degree of heterogeneity among these studies (Chi Sq 10.56 p<0.05). A meta‐analysis of the three studies which reported PEF data, significantly favoured optimal peak flow self‐management over medications adjustment via regular medical review (SMD 0.16, 95% CI 0.01 to 0.31, Analysis 1.2). These studies were also heterogeneous. (Chi Sq 9.09 p<0.05). A fourth study found no significant difference between the groups in any pulmonary function variable.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Peak Flow Self Management vs Regular Doctor Review, Outcome 1 FEV1 (mean).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Peak Flow Self Management vs Regular Doctor Review, Outcome 2 Peak Expiratory Flow (mean).

The source of heterogeneity in the lung function results was explored. Two studies (Grampian 1994, Jones 1995 ) showed no difference between the groups while the remaining study (Ayres 1996) significantly favoured peak flow self‐management for both FEV1 and PEF in the meta‐analysis. However in the text of this paper the authors report for lung function: "the differences between groups were also non‐significant." The paper states these measurements are mean (standard deviation) for these outcomes while reporting mean (standard error) for other outcomes. It is possible that there is a transcription error and the measurement is actually mean (SE). The 'standard deviations' reported for PEF and FEV1 were 18 and 0.2, which are low in comparison to other data we have collected on peak expiratory flow and FEV1. When the meta‐analyses were repeated assuming a transcription error there was no difference between the doctor managed group and peak flow self‐managed group for FEV1 (SMD 0.0 [‐0.14 to 0.15]) and PEF (SMD 0.06 [‐0.09 to 0.21]) and heterogeneity was eliminated. We are awaiting confirmation from the author that the PEF and FEV1 variance represents SE rather than SD. Heterogeneity could not be explained by considering other variables such as asthma severity, duration of intervention or review by GP or specialist. For these meta analyses we have used the adjusted SD assuming there was a transcription error.

OUTCOMES: COMPARISON 2: PEF SELF‐MANAGEMENT versus SYMPTOMS SELF‐MANAGEMENT (n = 6 trials)

Self‐management using a written action plan based on PEF was found to be equivalent to self‐management using a symptoms based written action plan in the six studies which compared these interventions for the proportion of subjects requiring hospitalisation, and unscheduled visits to the doctor. Emergency room visits were significantly reduced by PEF self‐management in one study (Cowie 1997) but were similar to symptoms self‐management in four other studies. Symptoms‐based self‐management reduced the number of subjects requiring a course of oral corticosteroids in one study (Charlton 1990).

OUTCOMES: COMPARISON 3: OPTIMAL SELF‐MANAGEMENT versus MODIFIED OPTIMAL SELF‐MANAGEMENT (n = 3 trials)

Various options for optimal self‐management were compared in three studies. One study (Kauppinen 1998) that provided optimal self‐management but omitted regular review found that a higher number of health centre visits and 2.5 times more sickness days were reported for the control group (without regular review). A significant improvement in mean percent predicted FEV1 was reported for the group receiving regular medical review. No significant difference was found for those with or without regular review in mean percent predicted PEF or quality of life.

Cote 2001 reported that when the intensity of asthma education was reduced this led to a significantly increased proportion of subjects requiring unscheduled Dr visits. An improvement in quality of life score was reported for both intensive and reduced education with a significant improvement in symptom score for the intensive education group only.

Another study compared a verbally instructed action plan with a written action plan. There was no difference in asthma admissions, emergency room visits, home visits or PEF variability between the studies (Baldwin 1997).

Discussion

This systematic review of 15 RCTs evaluated the differing components of asthma self‐management interventions on health outcomes. The categorisation of the interventions in this review was based upon recommendations in current asthma management guidelines. Specifically, they were evaluated as to whether they included peak expiratory flow monitoring, regular medical review, and a written action plan. These are important aspects of asthma management which could be reliably evaluated from the papers For all trials in this review optimal asthma self‐management that included information, self‐monitoring, regular medical review and a written action plan was compared to variations of optimal self‐management.

It had previously been established that optimal asthma self‐management interventions led to reduced health care utilisation, days off work and nocturnal asthma when compared to usual care (Gibson 1999). Interventions that did not include a written action plan were found to be less efficacious. In this review we examined different forms of optimal asthma self‐management education. Due to the small number of trials in each subgroup analysis and the way in which data were reported there were few studies that could provide data for meta‐analyses. In some cases (comparison 3), it was not possible to group studies in any meaningful way for analysis, and these studies are reported individually.

When we reviewed the six trials that compared two forms of adjustment of medication, either self adjustment with the aid of a written action plan or adjustment by the doctor, we found no significant differences between these two methods in terms of asthma outcomes. This suggests that both approaches can be used in the management of asthma. In clinical practice this is an important observation since it allows health professionals to tailor the intervention they provide to adults with asthma. Depending on the resources and patient preferences, adults with asthma can be offered regular medical review or a self‐management programme. It would be useful to conduct an economic analysis of these two intervention types in the future.

Self monitoring of PEF involves the regular measurement of PEF and recording the best of three measurements in a diary morning and night. Medication is then adjusted according to changes in PEF levels. In contrast, adjustment of medications can be made according to the patient's symptoms such as nocturnal asthma or an increased need for reliever medication. Both PEF and symptom self‐monitoring have their limitations. Compliance with PEF monitoring in the long term is poor and some patients are poor perceivers of their symptoms. In reviewing the six trials that compared PEF and symptom self‐monitoring no significant differences in health outcomes were found, suggesting that the use of either method is effective. This is a clinically important observation as self‐monitoring can be tailored to patient preference, patient characteristics and the resources available.

In reviewing the three trials that examined various modifications of optimal self‐management no difference was found between verbal and written action plans. The inclusion of regular review led to improved asthma morbidity and lung function. Reduction of education intensity appeared to dilute the effect of the intervention. These are important observations, however each of these results come from single trials only and need further investigation.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Optimal self‐management allowing for optimisation of asthma control by adjustment of medications may be conducted by either self‐adjustment with the aid of a written action plan or by regular medical review. Either symptoms diaries or peak expiratory flow measurement can be used for self‐monitoring. Reducing the intensity of education appears to dilute the effect. This result was from one study and should be confirmed.

Implications for research.

What are the economics of the various optimal interventions? How intense should the education be? Are verbal action plans as effective as written action plans?

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 13 August 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 1998 Review first published: Issue 1, 2003

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 12 March 2002 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Cochrane Airways Review Group who helped with database searches, obtaining studies and translations (Steve Milan, Toby Lasserson, Anna Bara, Karen Blackhall) and Jenni Coughlan and Amanda Wilson for their contribution. Thanks also to Kirsty Olsen who has copy edited this review.

We would like to thank the following authors for providing information about their trials: Dr JG Ayres Dr A Lahdensuo Mr M Mullee re Jones Dr J Cote Dr D Baldwin Dr I Charlton We would also like to thank the Cooperative Research Centre for Asthma, Australia for financial support

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Peak Flow Self Management vs Regular Doctor Review.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 FEV1 (mean) | 3 | 707 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.10 [‐0.05, 0.25] |

| 2 Peak Expiratory Flow (mean) | 3 | 707 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.16 [0.01, 0.31] |

| 3 FEV1 adjusted (mean) | 3 | 707 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.00 [‐0.14, 0.15] |

| 4 Peak Expiratory Flow adjusted (mean) | 3 | 707 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.06 [‐0.09, 0.21] |

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Peak Flow Self Management vs Regular Doctor Review, Outcome 3 FEV1 adjusted (mean).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Peak Flow Self Management vs Regular Doctor Review, Outcome 4 Peak Expiratory Flow adjusted (mean).

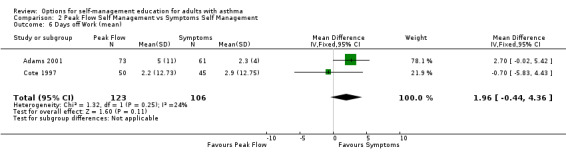

Comparison 2. Peak Flow Self Management vs Symptoms Self Management.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Hospitalisation (subjects) | 4 | 412 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.17 [0.44, 3.12] |

| 2 Hospitalisations (mean) | 2 | 229 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.04 [‐0.13, 0.05] |

| 3 ER Visits (subjects) | 5 | 512 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.61, 1.35] |

| 4 ER Visits (mean) | 2 | 229 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.04 [‐0.17, 0.09] |

| 5 Dr Visits (subjects) | 2 | 161 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.78, 1.10] |

| 6 Days off Work (mean) | 2 | 229 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.96 [‐0.44, 4.36] |

| 7 Oral Corticosteroid Courses | 2 | 152 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.53 [0.82, 2.87] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Peak Flow Self Management vs Symptoms Self Management, Outcome 1 Hospitalisation (subjects).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Peak Flow Self Management vs Symptoms Self Management, Outcome 2 Hospitalisations (mean).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Peak Flow Self Management vs Symptoms Self Management, Outcome 3 ER Visits (subjects).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Peak Flow Self Management vs Symptoms Self Management, Outcome 4 ER Visits (mean).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Peak Flow Self Management vs Symptoms Self Management, Outcome 5 Dr Visits (subjects).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Peak Flow Self Management vs Symptoms Self Management, Outcome 6 Days off Work (mean).

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Peak Flow Self Management vs Symptoms Self Management, Outcome 7 Oral Corticosteroid Courses.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Adams 2001.

| Methods | DESIGN: Randomised Trial of Two Interventions METHOD OF RANDOMISATION: Random numbers after stratification for age, gender, and number already in each group. MEANS OF ALLOCATION CONCEALMENT‐ not stated. OUTCOME ASSESSOR BLINDING ‐ not stated. WITHDRAWAL/DROPOUTS ‐ all subjects accounted for. | |

| Participants | Eligible: 380 Randomised: 172 Completed: 134 (Intervention 73, Control 61) Age: mean: PFM 37.3 yrs , Symptoms 35.5 yrs Range: eligible range 16 to 70 yrs Sex: PFM: Male / Female ‐ 40%/60% Symptoms 38%/62% Asthma Diagnosis: ATS Recruitment: Inpatients & outpatients Diseases Included: Major exclusions: Previous life threatening asthma, previous or current action plan, pregnancy, poor perception of bronchoconstriction(histamine challenge), baseline FEV1 <1.5L Baseline: FEV1: PEF: mean(SD) % predicted PFM: 75.8(18), Symptoms 75.6(18) Exacerbations: | |

| Interventions | Setting: Inpatients & outpatients Type: Two optimal self management interventions: (1) education in use of written action plans, monthly telephone contact for reinforcement and data collection and ongoing education, self monitoring of PEF. Seen by specialist on entry to study and commenced on inhaled corticosteroids (2) same as intervention 1 but symptom self monitoring Duration: Initial intervention duration not stated. Monthly telephone call for 12 months. months | |

| Outcomes | Hospitalisation, ER visits, FEV1, days off work or school, PD20 histamine, severity self‐rating. | |

| Notes | Jadad Score: 5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Information not available |

Ayres 1996.

| Methods | DESIGN: Randomised Trial of Two Interventions METHOD OF RANDOMISATION: Computer MEANS OF ALLOCATION CONCEALMENT‐ adequate OUTCOME ASSESSOR BLINDING ‐ not blinded WITHDRAWAL/DROPOUTS ‐ all subjects accounted for. | |

| Participants | Eligible: Randomised: 126 Completed: 50 Age: Overall mean: Intervention 44 years Control 47 Range: > 17 Sex: Male / Female ‐ 51 / 74 Asthma Diagnosis: Objective Lung Function Recruitment: ? Diseases Included: Major exclusions: Respiratory Tract Infections Baseline: FEV1: baseline not measured PEF: % potential normal (mean +/‐ SEM). Intervention 79 +/‐ 2, Control 72+/‐ 2. Exacerbations: 1 documented exacerbation in previous 6 months which required contact with a doctor or a nurse. | |

| Interventions | Setting: GP/ outpatient clinic Type: Intervention 1 = Optimal Self Management including one to one education with the doctor, self‐monitoring of peak flow, regular medical review within the program and a written action plan allowing self adjustment of medications based on peak flow. Intervention 2 = One to one Education with the doctor, Self‐Monitoring of symptoms and Regular Review (i.e. doctor managed). Duration: Not specified. | |

| Outcomes | Office FEV1, FVC, (patients asked not to use terbutaline during the 5 h before each visit), asthma symptoms, activity limitation, morning and evening pre bronchodilator PEF (best of 3), terbutaline and budesonide inhalations, sleep disturbance. | |

| Notes | Jadad Score = 5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Sequentially numbered, sealed , opaque envelopes |

Baldwin 1997.

| Methods | DESIGN: Randomised Trial of Two Interventions METHOD OF RANDOMISATION: random number generation MEANS OF ALLOCATION CONCEALMENT‐ None ‐ assessment made by separate doctor OUTCOME ASSESSOR BLINDING ‐ Yes WITHDRAWAL/DROPOUTS ‐ all subjects accounted for | |

| Participants | Eligible: 50 Randomised: 50 (Verbal intervention 25, written intervention 25) Completed: 50 Age: 17 to 39yrs: verbal 44%, written 60%. 40 to 59yrs: verbal 36%, written 28%. 60 to 70yrs: 20%, written 12% Range: Sex: Male / Female ‐ 46% / 27% Asthma Diagnosis: Objective lung function Recruitment: General Practice Diseases Included: Major exclusions: illiteracy, pregnancy, history of occupational asthma, chronic lung disease other than asthma, heart disease. Baseline: mod‐severe asthma FEV1: PEF: < 75% predicted Exacerbations: | |

| Interventions | Setting: GP asthma clinic Type: Intervention 1: Verbal instruction on asthma management, PEF self monitoring and recording twice daily. Information posters in waiting room and handouts received on 'asthma in the family'. 3 monthly consultations where treatment could be adjusted. Intervention 2: received the same as intervention 1 but also included a written asthma action plan. Duration: Initial assessment then 3 study visits 3 months apart | |

| Outcomes | Hospitalisation, ER visits, PEF, rescue medication, nocturnal symptoms, lifestyle, medication, morbidity and drug use score. | |

| Notes | Jadad Score: 4 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Investigators unaware as to order of treatment group assignment |

Charlton 1990.

| Methods | DESIGN: Randomised Trial of two types of self management plans METHOD OF RANDOMISATION: random numbers chart (not clear if open or closed). METHOD OF ALLOCATION CONCEALMENT: not stated. OUTCOME ASSESSOR BLINDING: not stated. WITHDRAWAL/DROPOUTS: unsure. | |

| Participants | Eligible: 115 Randomised: Peak Flow 51; Symptoms Only 64 Completed: "all 115 patient attended the asthma clinic". Age: 46 Children: 19 Peak Flow; 27 Symptoms. Sex: Male / Female ‐ N/S Asthma Diagnosis: "All patients receiving prophylactic treatment for asthma" Recruitment: General Practice Diseases Included: N/S Major exclusions: "Patients who required maintenance treatment with steroids or nebulised salbutamol during the study were not included in the relevant analyses". Baseline: FEV1: N/S PEF: N/S Exacerbations | |

| Interventions | Setting: Nurse run asthma clinic in a general practice Type: Two optimal self management interventions. One based on peak flow the other on symptoms. 1. Education, self monitoring of peak flow, regular review and a written action plan enabling self adjustment of medications in the event of worsening asthma on the basis of peak flow readings. 2. Education, self monitoring of symptoms, regular review and self adjustment of medications in the event of worsening asthma on the basis of symptoms. Duration: Initial one to one interview with nurse took 45 minutes plus one follow‐up interview which took 15 minutes. All patients reviewed by the nurse every 8 weeks or more often if necessary. If necessary, drug regimens were altered by the nurse after consultation with the GP. | |

| Outcomes | Doctor consultations, courses of oral steroids, short term nebulised salbutamol treatments, | |

| Notes | Jadad Score = 3 Data was provided separately for adults and children. We have only used the data for adults. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Information not available |

Cote 1997.

| Methods | DESIGN: Randomised controlled trial of two interventions METHOD OF RANDOMISATION: Randomised ‐ stratified randomisation MEANS OF ALLOCATION CONCEALMENT‐ not stated. OUTCOME ASSESSOR BLINDING ‐ not blinded. WITHDRAWAL/DROPOUTS ‐ all subjects accounted for. | |

| Participants | Eligible: not specified Randomised: 188 (Peak Flow 62, Symptoms Only 52, Control 74) Completed: 149 (Peak Flow 50, Symptoms Only 45, Control 54) Age: Overall mean: 36 yrs Range: Sex: Male / Female ‐ Asthma Diagnosis: Doctor's diagnosis and objective lung function Recruitment: Hospital admissions or visit to a clinic. Diseases Included: Major exclusions: current and ex‐smokers 40 yr of age or older in whom the best TEV1 after salbutamol was <80% of predicted, patients with significant concurrent diseases, those requiring >7.5 mg prednisone to control asthma symptoms and those who had already taken part in an asthma education program. Baseline: FEV1: not stated PEF: % predicted: Peak Flow 93+/‐3; Symptoms 91+/‐3; Control 95+/‐3. Exacerbations not stated | |

| Interventions | Setting: tertiary care setting Type: Two optimal interventions and an active control. 1. Education, peak flow self monitoring, regular review and individualised written action plan based on peak flow enabling self adjustment of medications in the event of worsening asthma. 2. Education, symptoms self monitoring, regular review and a symptoms based written action plan enabling self adjustment of medications in the event of worsening asthma. 3. Control group: Taught inhaler technique by the educator and about medication use and triggers by their pulmonologist. Their physician may have provided a verbal action plan. Duration: A minimum of 1 x one hour one to one counselling sessions for both educated groups | |

| Outcomes | Knowledge, compliance, hospitalisations, ER visits, oral corticosteroids, days lost from work or school. | |

| Notes | Jadad Score: 4 Treatment was optimised for all subjects during baseline. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Information not available |

Cote 2001.

| Methods | DESIGN: Randomised controlled trial of two interventions METHOD OF RANDOMISATION: Stratified by treatment centre, randomisation method not stated. Control group not randomised. MEANS OF ALLOCATION CONCEALMENT‐ not stated, control group open OUTCOME ASSESSOR BLINDING ‐ WITHDRAWAL/DROPOUTS ‐ | |

| Participants | Eligible: not stated Randomised: 126 (Intervention LE ?, intervention SE ?) Completed: 98 ( Intervention LE 30, intervention SE 33, control 35) Age: Overall mean: 34.5 yrs Range: >18 yrs Sex: Male / Female ‐ Asthma Diagnosis: Doctor diagnosis Recruitment: ER or outpatient clinic with exacerbation Diseases Included: Major exclusions: > 40yrs with FEV1 <80% (to avoid COPD), any concurrent illness Baseline: Mean duration asthma 10.2 yrs. FEV1: PEF: % predicted: Intervention LE 89.8%, Intervention SE 89.8% Exacerbations: admitted with acute exacerbations | |

| Interventions | Setting: 2 university hospitals Type: 2 interventions and a non randomised control group. Intervention LE: Limited education but including action plan‐ instructed in use of inhaler, explanation of self action plan by physician. Choice of action plan based on symptoms or PEF. Received standard care with therapy modified according to action plan. Intervention SE: Included the LE intervention plus self management education ‐ a structured educational program based on the 'PRECEDE model'‐ including predisposing factors, enabling factors and reinforcement. Control group received usual care. ‐ not used as not randomised Duration: SE intervention conducted 2 weeks after randomisation ‐ length of time not stated. Reinforced at 6 months | |

| Outcomes | Knowledge,ER visits, unscheduled Dr visits, PEF, quality of life compliance | |

| Notes | Jadad Score: 4 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Information not available |

Cowie 1997.

| Methods | DESIGN: Randomised controlled trial of two interventions METHOD OF RANDOMISATION: Random numbers list MEANS OF ALLOCATION CONCEALMENT‐ Adequate OUTCOME ASSESSOR BLINDING ‐ outcome assessors blinded WITHDRAWAL/DROPOUTS ‐ all subjects accounted for. | |

| Participants | Eligible: not specified Randomised: 151 (one withdrawn: not asthma) Completed: 139 (Peak Flow 46, Symptoms Only 45, Control 48) Age: Overall mean: 36.4 yrs Standard Deviation: 15.9 yrs Sex: Male / Female ‐ (Peak Flow 17/29, Symptoms Only 20/25, Control 19/29) Asthma Diagnosis: Doctor's diagnosis and objective lung function Recruitment: Urgent emergency room treatment for asthma. Diseases Included: Not specified. Included those who already had a peak flow meter. Major exclusions: Those who already had a written action plan. Baseline: FEV1: not stated PEF: not stated Exacerbations All subjects had required urgent treatment for asthma in the previous 12 months. | |

| Interventions | Setting: individual nurse led education Type: Two optimal interventions and an active control. 1. Education (as per control), peak flow self monitoring, medication assessment within the program and advised to seek regular review outside the program and individualised written action plan based on peak flow enabling self adjustment of medications in the event of worsening asthma. 2. Education (as per control), NO symptoms or peak flow self monitoring, medication assessment within the program and advised to seek regular review outside the program and a symptoms based written action plan enabling self adjustment of medications in the event of worsening asthma. 3. Control group: 45 minutes education by the nurse educator about asthma, triggers, medication use and devices as per the interventions above. Medications assessed and if inadequate, patients physician was notified. Patients advised that their dose of corticosteroid may need to be adjusted from time to time. Duration: 45 minutes one to one counselling sessions for all groups | |

| Outcomes | Hospital admissions, ER visits. | |

| Notes | Jadad Score: 5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Sequentially administered identical opaque closed envelope technique |

Grampian 1994.

| Methods | DESIGN: 2x2x2 block randomised trial stratified by physician. METHOD OF RANDOMISATION: the word "random" stated ; method not described. METHOD OF ALLOCATION CONCEALMENT: not described. OUTCOME ASSESSOR BLINDING: not stated. WITHDRAWAL/DROPOUTS: dropouts (6%) not accounted for. | |

| Participants | Eligible: 801 consented but 232 already had peak flow meter and could not be randomised for this arm. Randomised: 569: Peak flow self monitoring 285, Conventional monitoring 284 Completed: 458: Peak flow self monitoring 230, Conventional monitoring 228. Age: Mean Intervention 51.1 yrs Control 50.5 years Range: >16 years. Sex: Male / Female Intervention 48/52% Control 40/60% Asthma Diagnosis: Doctor's diagnosis and objective lung function Recruitment: Hospital outpatient clinics and general practices in north east Scotland. Diseases Included: N/S Major exclusions: N/S Baseline: FEV1: % of predicted: Intervention 77.3%; Control 78.1% PEF: Mean: Intervention 344.5; Control 341.6. Exacerbations: N/S | |

| Interventions | Setting: Type: education, self monitoring of peak flow, and regular review and written action plan to enable self adjustment of medications in response to worsening asthma based on peak flow. (due to the factorial design, some of the intervention group were randomised to receive enhanced education while the others had conventional education. Similarly, some were randomised to receive integrated care while others had conventional care). Control: Some had enhanced education but none had peak flow meters. Duration: not stated | |

| Outcomes | Hospitalisation, unscheduled doctor visits, FEV1 % predicted, use of rescue medication, quality of life, days off work, inhaled steroids, disrupted days, nocturnal asthma. | |

| Notes | Jadad Score = 3 Confounding due to factorial design. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Information not available |

Jones 1995.

| Methods | DESIGN: Randomised Controlled Trial. Stratified by centre in blocks of six. METHOD OF RANDOMISATION: the word "random" stated ; method not described. METHOD OF ALLOCATION CONCEALMENT: not described. OUTCOME ASSESSOR BLINDING: not clear ‐ "data rendered anonymous" before analysis. WITHDRAWAL/DROPOUTS: not described. | |

| Participants | Eligible: not stated Randomised: 127 Completed: 72 (Intervention self management 33; planned visits 39) Age: self managed : mean 30.4 yrs SD 11.5 yrs planned visits: mean 28.6 SD 7 yrs. Sex: Male / Female Self managed 14/19 planned visits 12/26. Asthma Diagnosis: Doctor's diagnosis Recruitment: General practices Diseases Included: Not specified Major exclusions: Those on regular oral steroids and those who were regularly conducting home PEF monitoring. Baseline: FEV1: % predicted: self management 85.1 (SD 20.8), planned visits 80.2 (SD19.9) PEF: % predicted: self management 88.2 (SD 15.4), planned visits 86.8 (SD 13.7) Exacerbations | |

| Interventions | Setting: General Practice Type: Optimal self management: education, peak flow self monitoring, regular review and an individualised written action plan based on peak flow enabling self adjustment of medications in the event of worsening asthma. Control: regular review and kept a daily diary for morbidity and bronchodilator use for outcomes. Duration: 5 study visits (duration not stated) over a 26 week period | |

| Outcomes | Lung Function ‐ % predicted, Use of rescue medication, quality of life, days off work, wheeze (frequency, severity), nocturnal asthma, oral corticosteroid use, cough, shortness of breath, disrupted days. | |

| Notes | Jadad Score = 4 Oral corticosteroids was given for 2 weeks to optimise lung function in both groups during baseline. Drop outs were more likely to be younger and male with lower initial FVC values then the completers. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Information not available |

Kauppinen 1998.

| Methods | DESIGN: Randomised Trial of two Interventions METHOD OF RANDOMISATION: Computer MEANS OF ALLOCATION CONCEALMENT‐ Adequate OUTCOME ASSESSOR BLINDING ‐ not stated WITHDRAWAL/DROPOUTS ‐ all subjects accounted for. | |

| Participants | Eligible: not stated Randomised: 162 (optimal self management 80, self management 82) Completed: 157 (optimal SM 77, SM 80) Age: Overall mean: 43.7 Range: 18 ‐ 76 Sex: Male / Female ‐60 / 102 Asthma Diagnosis: ATS criteria Recruitment: outpatient clinic Diseases Included: Major exclusions: Baseline: newly diagnosed asthmatics with >15% reversibility FEV1: % predicted ‐ optimal SM 86.1%, SM 82.8% PEF: % predicted ‐ optimal SM 84.3%, SM 83.4% Exacerbations: | |

| Interventions | Setting: outpatients clinic Type: Intervention 1: Optimal self management including basic asthma education, PEF, principles of treatment, video, self monitoring, written action plan and regular review. Intervention 2: Self Management education as for optimal group without the regular review. Duration: 2 visits for self management group and further group education every 3 months for 12 months for the optimal SM group totaling 8 hours | |

| Outcomes | ER visits, unscheduled Dr visits, FEV1, costs, days off work, quality of life, FVC, PD15 histamine, FEV%, normal airway responsiveness achieved | |

| Notes | Jadad Score: 4 Followed up at 12 months, 3 years and 5 years |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Appointments made by nurse on duty according to study plan after randomisation. |

Klein 2001.

| Methods | DESIGN: Randomised trial of two interventions METHOD OF RANDOMISATION: random stated method not described MEANS OF ALLOCATION CONCEALMENT‐ Closed envelope technique OUTCOME ASSESSOR BLINDING ‐ single blind stated ‐ not defined who was blind WITHDRAWAL/DROPOUTS ‐ all subjects accounted for | |

| Participants | Eligible: 485 Randomised: 245 ( Intervention optimal SM 123, intervention SM 122) Completed: 174 (Intervention optimal SM 84, intervention SM 90) Age: Overall mean: 44 Range: eligible range 18 to 65 Sex: Male / Female ‐ 111 / 134 Asthma Diagnosis: Objective lung function Recruitment: Outpatient clinic Diseases Included: Major exclusions: serious medical or psychiatric comorbidity Baseline: moderate ‐ severe asthma ‐ continuous use of inhaled steroids for 3 month minimum. FEV1: reversibility >15% or >9% predicted or 20% fall with histamine challenge PEF: mean % predicted: optimal SM 76.0, SM 76.9. Mean PEF optimal SM 381, SM 389 Exacerbations: | |

| Interventions | Setting: outpatients clinic Type: Both groups instructed in pathophysiology of asthma, medications, triggers and indicators of exacerbation. written material also provided. Video for inhaler technique. Self monitoring of PEF for 2 weeks for outcome measurement at 4, 8, 12, 18 & 24 months. Regular follow‐up with own chest physician. Optimal SM group also instructed in self management with a written action plan Duration: 3 x 90 minute group sessions | |

| Outcomes | Unscheduled Dr visits, PEF variability, FEV1, exacerbations, quality of life, hospital days, PC20 histamine, symptom free days, telephone contacts, perceived control of asthma | |

| Notes | Jadad Score: 5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Information not available |

Lahdensuo 1996.

| Methods | DESIGN: Randomised Controlled Trial METHOD OF RANDOMISATION: Randomised ‐ blocks of variable sizes and stratified by centre MEANS OF ALLOCATION CONCEALMENT‐ Adequate. OUTCOME ASSESSOR BLINDING ‐ single blind. WITHDRAWAL/DROPOUTS ‐ all subjects accounted for. | |

| Participants | Eligible: 122 Randomised: 122 (Intervention 60, Control 62) Completed: 115 (Intervention 56, Control 59) Age: Overall mean: 41.7 yrs (SD 14.7) Sex: Male / Female Intervention 43/59 Asthma Diagnosis: Objective lung function Recruitment: Out patient clinics in Finland ‐ mild to moderately severe asthma. Diseases Included: Smokers Major exclusions: Not stated Baseline: FEV1: % Predicted Intervention 82.4 (SD 15.8), Control 81.7 (16.6) PEF: Exacerbations: No oral corticosteroids in the last 4 weeks before entry. | |

| Interventions | Setting: Outpatient clinics in Finland Type: Optimal self management including a written action plan allowing self adjustment of anti‐inflammatory medications according to peak flow, self monitoring of peak flow, regular review within the program and education. Duration: At the first visit, one to one education was provided which took an extra 1.5hrs longer then the control visit. | |

| Outcomes | Hosptialisations, Unscheduled doctor visits, FEV1, (%predicted ‐ pre bronchodilator), oral corticosteroids, days off work or school, quality of life, courses of antibiotics, costs. | |

| Notes | Jadad Score: 3 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Sealed number envelopes |

Lopez‐Vina 2000.

| Methods | DESIGN: Randomised trial of two interventions METHOD OF RANDOMISATION: random stated, method not described. MEANS OF ALLOCATION CONCEALMENT‐ not stated OUTCOME ASSESSOR BLINDING ‐ not stated WITHDRAWAL/DROPOUTS ‐ all subjects accounted for | |

| Participants | Eligible: 192 Randomised: 150 Completed: 100 (PEF group 56, symptom group 44) Age: 17 to 37yrs PEF group 43%, symptom group 41%. 35 to 65 yrs PEF group 57%, symptom group 59% Range: Sex: Male / Female ‐ 49/51 Asthma Diagnosis: ATS criteria Recruitment: Emergency Dept Diseases Included: Major exclusions: COPD, emphysema, cystic fibrosis, severe rheumatoid arthritis, neoplasia Baseline: mild 8%, moderate 60%, severe 32% FEV1: > 20% reversibility or > 20% reversibility after methacholine challenge PEF: Exacerbations: recruited while visiting ER with an acute exacerbation | |

| Interventions | Setting: Type: Two optimal self management interventions. One based on peak flow the other on symptoms. All subjects received personal instruction on general asthma concepts, treatment, asthma management, adherence enhancing strategies and regular review. PEF group: received informative pamphlets, diary cards for PEF self monitoring and a written self management plan with colour coded card. Symptom group: received a self management plan based on symptoms only Duration: Commenced 1month after ER visit with follow‐up at 15 days, 1 month and every 3 months for total 1 year | |

| Outcomes | Hospitalisation, ER visits, FEV1, days off work, nocturnal asthma, exacerbations, FVC, days with symptoms, inhaler technique, adherence | |

| Notes | Jadad Score = 4 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Information not available |

Sommaragua 1995.

| Methods | DESIGN: METHOD OF RANDOMISATION: Randomised ‐ stated. Method not described. MEANS OF ALLOCATION CONCEALMENT‐ not stated. OUTCOME ASSESSOR BLINDING ‐ not stated. WITHDRAWAL/DROPOUTS ‐ all subjects accounted for. | |

| Participants | Eligible: not stated Randomised: 40 (Intervention 20, Control 20) Completed: 36 (Intervention 20, Control 16) Age: Overall mean: 48 Range: +/‐16 yrs Sex: Male / Female : 21/19 Asthma Diagnosis: Dr diagnosis implied: International Guidelines Recruitment: Hospital inpatients at a Respiratory Medical Centre Diseases Included: Not stated Major exclusions: Not stated Baseline: FEV1: 76+/‐ 18% predicted before and 94+/‐ 5% predicted after salbutamol. PEF: not stated Exacerbations: not stated. | |

| Interventions | Setting: Inpatient education programme Type: Education, peak flow medications and symptoms self monitoring, medical review every 2 months with the same physician, written action plan allowing the patient to alter medications in response to worsening asthma. (plus a psychological intervention). Duration: 2 lessons during admissions of unknown duration and quarterly lessons during the ensuring year. | |

| Outcomes | Hospitalisation, ER visits, Days off work, Asthma Attacks, Resp. Illness Opinion Survey, Health Locus of Control, STA1 x 2 (anxiety, AD (Depression) APF (psychophysiological disorders), Asthma Symptom Checklist. ‐ Only reported the psychological outcomes. | |

| Notes | Jadad Score = 3 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Information not available |

Turner 1998.

| Methods | DESIGN: Randomised Trial of two types of self management plans METHOD OF RANDOMISATION: random numbers chart (not clear if open or closed) after stratification for severity of airways responsiveness (ie <2mg/ml or >19 mg/ml for PC20 methacholine) METHOD OF ALLOCATION CONCEALMENT: not stated. OUTCOME ASSESSOR BLINDING: not stated. WITHDRAWAL/DROPOUTS: all accounted for. | |

| Participants | Eligible: 150 screened Randomised: 117 Completed: 92 (Peak Flow 44; Symptoms 48) Age: Mean 34.1 years (SD 9.95) Sex: Male% / Female% 47/53 Asthma Diagnosis: according to ATS guidelines Recruitment: Primary care setting Diseases Included: N/S Major exclusions: Significant co‐morbid conditions that would impact on quality of life measures, current use of, or inability to use a peak flow meter, or inability to communicate in English. Baseline: FEV1:mean (SD): peak flow group 2.84 l/min (0.86); symptoms group 2.86 (0.86) PEF: N/S Exacerbations: number who had attended Emergency Department in past six months was 8 and 3 for the peak flow and symptoms groups respectively. | |

| Interventions | Setting: Nurse run asthma clinic Type: Two optimal self management interventions. One based on peak flow the other on symptoms. 1. Education, self monitoring of peak flow, regular review and a written action plan enabling self adjustment of medications in the event of worsening asthma on the basis of peak flow readings. 2. Education, self monitoring of symptoms, regular review and self adjustment of medications in the event of worsening asthma on the basis of symptoms. Duration: 6 x 30 minute one to one interviews with a registered nurse. All patients reviewed by the nurse every month. Patients had to attend 5 or more visits to be included in the final analysis. | |

| Outcomes | PEF, FEV1, Quality of Life, Symptom Scores. | |

| Notes | Jadad Score: 5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Information not available |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Abdulwadud 1997 | Self management versus usual care |

| Abdulwadud 1999 | Baseline data only |

| Aiolfi 1995 | Information only education |

| Allen 1995 | Self management versus usual care |

| Bailey 1990 | Self management versus usual care |

| Bailey 1999 | Self management versus usual care |

| Berg 1997 | Self management versus usual care |

| Blixen 2001 | Self management versus usual care |

| Bolton 1991 | Information only education |

| Boulet 1995 | Methodological problems |

| Brewin 1995 | Self management vs usual care |

| Cox 1993 | Not an education intervention |

| de Oliveira 1999 | Self management versus usual care |

| Erickson 1998 | Sample size too small, not an RCT |

| Gallefoss 1999 | Self management versus usual care |

| Garrett 1994 | Self management versus usual care |

| George 1999 | Self management versus usual care |

| Gergen 1995 | Non‐RCT |

| Ghosh 1998 | Self management versus usual care |

| Graft 1991 | Non‐RCT |

| Grainger‐Rousseau | Not randomised. Children included. Mean age unknown |

| Grampian 1994b | Not education intervention |

| Hausen 1999 | Non‐RCT |

| Hayward 1996 | Self management versus usual care |

| Heard 1999 | Self management versus usual care |

| Heringa 1987 | Inappropriate outcomes |

| Hilton 1986 | Self management versus usual care |

| Hindi‐Alexander 1986 | Non‐RCT |

| Hoskins 1996 | Methodological problems |

| Huss 1992 | Information only education |

| Ignacio‐Garcia 1995 | Self management versus usual care |

| Jackevicius 1999 | Inhaler technique |

| Janson‐Bjerklie 1988 | Not an education intervention |

| Jenkinson 1988 | Information only education |

| Jones 1987 | Inappropriate outcomes |

| Kelso 1995 | Non‐RCT |

| Knoell 1998 | Self management versus usual care |

| Kotses 1995 | Self management versus usual care |

| Kotses 1996 | Self management versus usual care |

| LeBaron 1985 | Not an education intervention |

| Legorreta 2000 | Non‐RCT |

| Levy 2000 | Self management versus usual care |

| Lirsac 1991 | Not an education intervention |

| Maes 1988 | Not an education intervention |

| Maiman 1979 | Information only education |

| Mayo 1990 | Self management versus usual care |

| Moldofsky 1979 | Information only education |

| Moudgil 2000 | Self management versus usual care |

| Muhlhauser 1991 | Non‐RCT |

| Mulloy 1996 | Self management versus usual care |

| Neri 1996 | Self management versus usual care |

| Osman 1994 | Information only education |

| Perdomo‐Ponce 1996 | Non‐RCT. Focus on allergic diseases and therapeutic compliance |

| Petro 1995 | Not predominantly asthma |

| Premaratne 1999 | Nurse education |

| Ringsberg 1990 | Information only education |

| Rydman 1999 | Inhaler technique |

| Schott‐Baer 1999 | Self management versus usual care |

| Shields 1986 | Self management versus usual care |

| Snyder 1987 | Self management versus usual care |

| Sondergaard 1992 | Information only education |

| Thapar 1994 | Information only education |

| Tougaard 1992 | Not predominantly asthma |

| Verver 1996 | Inhaler technique |

| White 1989 | Not patient education |

| Wilson 1993 | Self management versus usual care |

| Yoon 1993 | Self management versus usual care |

| Zeiger 1991 | Self management versus usual care |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

Ford 1996.

| Trial name or title | An empowerment‐centered, church‐based asthma education program for African American adults |

| Methods | |

| Participants | African‐American adults with asthma |

| Interventions | General physiology of asthma, , identification of stressors, problem solving, medications, PEF monitoring |

| Outcomes | knowledge, ED visits, PEFV and inhaler technique, quality of life, perceived illness |

| Starting date | 1996 |

| Contact information | |

| Notes |

Ploska 1999.

| Trial name or title | An education based hospital nursing programme in the treatment of asthma |

| Methods | |

| Participants | Moderate asthmatics No. of participants: 80 Age group: 18‐75 |

| Interventions | |

| Outcomes | Respiratory function tests, use of corticosteroid/bronchodilator treatments, quality of life |

| Starting date | Unknown |

| Contact information | |

| Notes |

Contributions of authors

Gibson PG ‐ instigator of the review and conceptual direction ‐ inclusion/exclusion, quality assessment, data extraction, analysis and interpretation, writing and editing. Powell H ‐ responsible for inclusion/exclusion, quality assessment, data extraction, analysis, interpretation and writing.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Hunter Area Health Service, Australia.

External sources

Cooperative Research Centre for Asthma, Australia.

Declarations of interest

None

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Adams 2001 {published data only}

- Adams RJ, Boath K, Homan S, Campbell DA, Ruffin RE. A randomised trial of peak‐flow and symptom‐based action plans in adults with moderate‐to‐severe asthma. Respirology 2001;6:297‐304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ayres 1996 {published data only}

- Ayres JG, Campbell LM. A controlled assessment of an asthma self‐management plan involving a budesonide dose regimen. European Respiratory Journal 1996;9:886‐92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Baldwin 1997 {published data only}

- Baldwin DR, Pathak UA, King R, Vase BC, Pantin CFA. Outcome of asthmatics attending asthma clinics utilising self‐management plans in general practice. Asthma in General Practice 1997;5(2):31‐2. [Google Scholar]

Charlton 1990 {published data only}

- Charlton I, Charlton G, Broomfield J, Mullee MA. Evaluation of peak flow and symptoms only self‐management plans for control of asthma in general practice. British Medical Journal 1990;301:1355‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cote 1997 {published data only}

- Cote J, Cartier A, Robichaud P Boutin H, Malo J, Rouleau M, Fillion A, Lavellee M, Krusky M, Boulet L. Influence on Asthma Morbidity of asthma education programs based on self‐management plans following treatment optimization. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 1997;155:1509‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cote J, Cartier A, Robichaud P, Boutin H, Malo JI. Influence of asthma education on asthma severity, quality of life and environmental control. Canadian Respiratory Journal 2000;7(5):395‐400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cote 2001 {published data only}

- Cote J, Bowie DM, Robichaud P, Parent J‐G, Battiti L, Boulet L‐P. Evaluation of two different educational interventions for adult patients consulting with an acute asthma exacerbation. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2001;163:1415‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cowie 1997 {published data only}

- Cowie RL, Revitt SG, Underwood MF, Field SK. The effect of a peak flow‐based action plan in the prevention of exacerbations of asthma. Chest 1997;112:1534‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Grampian 1994 {published data only}

- Grampian Asthma Study of Integrated Care (GRASSIC). Effectiveness of routine self monitoring of peak flow in patients with asthma. British Medical Journal 1994;308:564‐7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jones 1995 {published data only}

- Jones KP, Mullee MA, Middleton M, Chapman E, Holgate ST, the British Thoracic Society Research Committee. Peak flow based asthma self‐management: a randomised controlled study in general practice. Thorax 1995;50:851‐7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kauppinen 1998 {published data only}

- Kauppinen R, Sintonen H, Vilkka V, Tukianen H. Long‐term (3‐year) economic evaluation of intensive patient education for self‐management during the first year in new asthmatics. Respiratory Medicine 1999;93:283‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauppinen R, Sintonene H, Tukiainen H. One‐year economic evaluation of intensive v conventional patient education and supervision for self‐management of new asthmatic patients. Respiratory Medicine 1998;92:300‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauppinen R, Vilkka V, Sintonen H, Klaukka T, Tukianen H. Long term economic evaluation of intensive patient education during the first treatment year in newly diagnosed asthma. Respiratory Medicine 2001;95:56‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Klein 2001 {published data only}

- Klein JJ, Palen J, Uil SM, Zielhaus GA, Seydel ER, Herwaarden CLA. Benefit from the inclusion of self‐treatment guidelines to a self‐management programme for adults with asthma. European Respiratory Journal 2001;17:386‐94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lahdensuo 1996 {published data only}

- Lahdensuo A, Haahtela T, Herrala J, Kava T, Kiviranta K, Kuusisto P, et al. Randomised comparison of cost effectiveness of guided self management and traditional treatment of asthma in Finland. British Medical Journal 1998;316:1138‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahdensuo A, Haahtela T, Herrala J, Kava T, Kiviranta K, Kuusisto P, et al. Randomised comparison of guided self management and traditional treatment of asthma over one year. British Medical Journal 1996;312:748‐52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lopez‐Vina 2000 {published data only}

- Lopez‐Vina A, Castillo‐Arevalo F. Influence of peak expiratory flow monitoring on an asthma self‐management education programme. Respiratory Medicine 2000;94:760‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sommaragua 1995 {published data only}

- Sommaruga M, Spanevello A, Migliori GB, Neri M, Callegari S, Majani G. The effects of a cognitive behavioural intervention in asthmatic patients. Monaldi Archives for Chest Disease 1995;50:398‐402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Turner 1998 {published data only}

- Turner MO, Taylor D, Bennett R, Fitzgerald JM. A randomized trial comparing peak expiratory flow and symptom self‐management plans for patients with asthma attending a primary care clinic. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 1998;157:540‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Abdulwadud 1997 {published data only}

- Abdulwadud O, Abramson M, Forbes A, James A, Light L, Thien F, et al. Attendance at an asthma educational intervention: characterisitics of participants and non‐participants. Respiratory Medicine 1997;91:524‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Abdulwadud 1999 {published data only}

- Abdulwadud O, Abramson M, Forbes A, James A, Walters EH. Evaluation of a randomised controlled trial of adult asthma education in a hospital setting. Thorax 1999;54:493‐500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Aiolfi 1995 {published data only}

- Aiolfi S, Confalonieri M, Scartabellati A, Patrini G, Ghio L, Mauri F, et al. International guidelines and educational experiences in an out‐patient clinic for asthma. Monaldi Archives for Chest Disease 1995;50:477‐81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Allen 1995 {published data only}

- Allen RM, Jones MP, Oldenburg. Randomised trial of an asthma self‐management programme for adults. Thorax 1995;50:731‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bailey 1990 {published data only}

- Bailey WC, Richards JM, Brooks CM, Soong S, Windsor RA, et al. A randomised trial to improve self‐management practice of adults with asthma. Archives of Internal Medicine 1990;150:1664‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey WC, Richards JM, Manzella BA, Windsor RA, Brooks CM, Soong SJ. Promoting self‐management in adults with asthma: an overview of the UAB Program. Health Education Quarterly 1987;14:345‐55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windsor RA, Bailey WC, Richards JM, Manzella B, Soong SJ, Brooks M. Evaluation of the efficacy and cost effectiveness of health education methods to increase medication adherence among adults with asthma. American Journal of Public Health 1990;80:1519‐21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bailey 1999 {published data only}

- Bailey WC, Kohler CL, Richards JM, Windsor RA, Brooks M, Gerald LB, et al. Asthma self‐management: do patient education programs always have an impact?. Archives of Internal Medicine 1999;159:2422‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Berg 1997 {published data only}

- Berg J, Dunbar‐Jacob J, Sereika SM. An evaluation of a self‐management program for adults with asthma. Clinical Nursing Research 1997;6(3):225‐38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Blixen 2001 {published data only}

- Blixen CE, Hammel JP, Murphy D, Ault V. Feasibility of a nurse‐run asthma education program for urban African‐Americans: a pilot study. Journal of Asthma 2001;38(1):23‐32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bolton 1991 {published data only}

- Bolton MB, Tilley BC, Kuder J, Reeves T, Schultz LR. The cost and effectiveness of an education program for adults who have asthma. Journal of General Internal Medicine 1991;6:401‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford ME, Havstad SL, Tilley BC, Bolton MB. Health outcomes among African American and Caucasian adults following a randomized trial of an asthma education program. Ethnicity & Health 1997;2(4):329‐39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Boulet 1995 {published data only}

- Boulet LP, Boutin H, Cote J, Leblanc P, Laviolettte M. Evaluation of an asthma self‐management program. Journal of Asthma 1995;32:199‐206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Brewin 1995 {published data only}

- Brewin AM, Hughes JA. Effect of patient education on asthma management. British Journal of Nursing 1995;4:81‐101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cox 1993 {published data only}

- Cox NJM, Hendricks JC, Binkhorst Ra, Herwaarden CLA. A pulmonary rehabilitation program for patients with asthma and mild chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPD). Lung 1993;171:235‐44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

de Oliveira 1999 {published data only}

- Oliveira MA, Faresin SM, Bruno VF, Bittencourt AR, Fernandes ALG. Evaluation of an educational programme for socially deprived asthma patients. European Respiratory Journal 1999;14(4):908‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Erickson 1998 {published data only}

- Erickson SR, Ascione FJ, Kirking DM, Johnson CE. Use of a paging system to improve medication self‐management in patients with asthma. Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association 1998;38:767‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gallefoss 1999 {published data only}

- Gallefoss F, Bakke PS. Cost‐effectiveness of self‐management in asthmatics: a 1yr follow‐up randomized, controlled trial. European Respiratory Journal 2001;17:206‐13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallefoss F, Bakke PS. How does patient education and self‐management among asthmatics and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease affect medication. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 1999;160:2000‐2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallefoss F, Bakke PS. Impact of patient education and self‐management on morbidity in asthmatics and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiratory Medicine 2000;94:279‐287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallefoss F, Bakke PS. Patient satisfaction with health care in asthmatics and patients with COPD before and after patient education. Respiratory Medicine 2000;94:1057‐1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallefoss F, Bakke PS, Kjaersgaard P. Quality of life assessment after patient education in a randomized controlled study on asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 1999;159:812‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Garrett 1994 {published data only}

- Garrett J, Fenwick JM, Taylor G, Mitchell E, Stewart J, Rea H. Prospective controlled evaluation of the effect of a community based asthma education centre in a multiracial working class neighbourhood. Thorax 1994;49:976‐83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

George 1999 {published data only}

- George MR, O'Dowd LC, Martin I, Lindell KO, Whitney F, Jones M, et al. A comprehensive educational programme improves clinical outcome measures in inner‐city patients with asthma. Archives of Internal Medicine 1999;159:1710‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gergen 1995 {published data only}

- Gergen PJ, Goldstein RA. Does asthma education equal asthma intervention?. International Archives of Allergy and Immunology 1995;107:166‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ghosh 1998 {published data only}