Abstract

Smokers with stronger neuroaffective responses to drug-related cues compared to non-drug-related pleasant images (C>P) are more vulnerable to compulsive smoking than individuals with the opposite brain reactivity profile (P>C). However, it is unknown if these neurobehavioral profiles exist in individuals abusing other drugs. We tested whether individuals with cocaine use disorder (CUD) show similar neuroaffective profiles to smokers. We also monitored eye movements to assess attentional bias toward cues and we further performed exploratory analyses on demographics, personality, and drug use between profiles. Participants with CUD (n=43) viewed pleasant, unpleasant, cocaine, and neutral images while we recorded electroencephalogram. For each picture category, we computed the amplitude of the late positive potential (LPP), an event-related potential component that reflects motivational relevance. k-means clustering classified participants based on their LPP responses. In line with what has been observed in smokers, clustering participants using LPP responses revealed the presence of two groups: one with larger LPPs to pleasant images compared to cocaine images (P>C) and one group with larger LPPs to cocaine images compared to pleasant images (C>P). Individuals with the C>P reactivity profile also had higher attentional bias toward drug cues. The two groups did not differ on demographic and drug use characteristics, however individuals with the C>P profile reported lower distress tolerance, higher anhedonia, and higher posttraumatic stress symptoms compared to the P>C group. This is the first study to report the presence of these neuroaffective profiles in individuals with CUD, indicating that this pattern may cut across addiction populations.

Keywords: addiction, attentional bias, event-related potentials, late positive potential

Introduction

Cocaine use disorder (CUD) is a persistent, debilitating condition that can occur with repeated use of cocaine (Pomara et al., 2012). While cocaine use declined in the United States in the early 2000s, both use and cocaine-related deaths increased from 2011-2015, emphasizing the public health importance of CUD research (John & Wu, 2017). Despite this, unlike other substance use disorders, there are currently no FDA-approved medications for the treatment of CUD and behavioral treatments have only small-to-moderate effects on cocaine abstinence (Sayegh et al., 2017). As a result, even when initial drug abstinence is achieved, individuals with CUD remain vulnerable to relapse (Higgins et al., 2000).

According to the incentive sensitization theory of addiction, the high risk of relapse that individuals with CUD experience stems from the high level of incentive salience that they attribute to drug-related cues (Robinson & Berridge, 1993; Sinha & Li, 2007). Incentive salience refers to the motivational properties of a stimulus. Stimuli with high incentive salience capture attention, activate affective states, and motivate behaviors (Berridge, 2012). By being repeatedly associated with drug use, drug-related cues can acquire incentive salience, induce drug cravings, and spur drug seeking and relapse (Robinson & Berridge, 1993).

In humans, one of the most reliable electrophysiological indices of a stimulus’ motivational relevance is the amplitude of the Late-Positive-Potential (LPP; Bradley, 2009; Lang & Bradley, 2010; Olofsson et al., 2008). The LPP, a positive-going component of the event-related potential (ERP) that peaks over centro-parietal sensors 400-800ms post-picture onset, is thought to reflect the engagement of cortico-limbic motivational systems (Keil et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2012; Schupp et al., 2006). The amplitude of the LPP increases as a function of the motivational relevance of a stimulus, irrespective of its hedonic valence: Pleasant and unpleasant stimuli with high motivational relevance (e.g., erotic scenes or images of mutilated bodies) evoke larger LPPs than stimuli with lower motivational relevance (e.g., romantic images or images of people looking sad), and these stimuli prompt larger LPPs than neutral images (Minnix et al., 2013; Schupp et al., 2000; Weinberg & Hajcak, 2010). Numerous studies show that the emotional modulation of the LPP is robust to manipulations affecting the perceptual properties of a stimulus (e.g., size, spatial frequency, complexity, color; Bradley et al., 2007; Codispoti et al., 2012; de Cesarei & Codispoti, 2011; de Cesarei & Codispoti, 2006), its exposure time (Codispoti et al., 2009) and its novelty (Bacigalupo & Luck, 2018; Deweese et al., 2018; Ferrari et al., 2010). Other studies show that the LPP is also robust to manipulations affecting expectations and other top-down contextual factors (Codispoti et al., 2020; Flaisch et al., 2008; Micucci et al., 2019). These characteristics make the LPP an ideal tool to evaluate the motivational relevance of drug-related cues in relation to other motivationally relevant stimuli (Versace et al., 2017).

When researchers assessed LPP responses in people with CUD, results showed that images depicting cocaine-related cues evoke LPP responses similar to those evoked by non-drug-related motivationally relevant images (Moeller et al., 2012; Parvaz et al., 2016, 2017). These results indicate that, on average, individuals with CUD attribute incentive salience to drug-related cues. Yet, it is important to note that the incentive sensitization theory also assumes that individuals should show differences in susceptibility to sensitization, and, as a results, in their tendency to attach incentive salience to drug-related cues (Robinson & Berridge, 2001). Preclinical studies support this hypothesis: during Pavlovian conditioning, when cues and rewards appear in different locations, animals develop two different behavioral phenotypes. Some animals, called sign-trackers, approach the cues, while others, called goal-trackers, approach the food location (Tomie et al., 2008). Measuring dopamine signaling in the nucleus accumbens during conditioning, Flagel and co-workers showed that sign-tracking is a behavioral consequence of the tendency to attribute high incentive salience to cues predicting rewards (Flagel et al., 2011). Importantly, animals that attribute incentive salience to food-related cues (the sign-trackers) also attribute high levels of incentive salience to drug-related cues and are vulnerable to cue-induced compulsive behaviors, including cue-induced nicotine and cocaine self-administration (Saunders & Robinson, 2010; Tunstall & Kearns, 2015; Versaggi et al., 2016; Yager & Robinson, 2013). If individual differences in the tendency to attribute incentive salience also characterize people with CUD, identifying patients that attribute high incentive salience to cocaine-related cues might help clinicians to develop targeted treatments that can more successfully prevent cue-induced relapse.

To pinpoint individual differences in the tendency to attribute incentive salience to drug-related cues in smokers, another population highly vulnerable to cue-induced relapse (Bedi et al., 2011), we recently turned to multivariate classification techniques. Typical cue reactivity paradigms compare drug to neutral cues (Engelmann et al., 2012); however, these designs leave out the important comparison between drug cues and other motivationally relevant cues (Versace et al., 2017). Applying k-means cluster analysis on the LPPs evoked by a wide array of motivationally relevant stimuli, we identified two main reactivity profiles: one characterized by larger LPP to drug-related cues compared to non-drug related pleasant stimuli (drug cue > pleasant cue, or C>P), and another characterized by increased LPP to pleasant stimuli compared to drug cues (pleasant cue > drug cue, or P>C; Engelmann et al., 2016; Frank et al., 2020; Versace et al., 2012). We showed that these psychophysiological differences have clinical relevance: the two groups respond differently to pharmacotherapy (Cinciripini et al., 2017), and when trying to quit, smokers with the C>P profile are less likely to achieve long-term smoking abstinence compared to those with the P>C profile (Versace et al., 2012, 2014). The similarities between the results that we observed in smokers and those from individuals with obesity (Versace et al., 2016, 2019) led us to hypothesize that these LPP-based brain reactivity profiles might be a transdiagnostic marker of vulnerability to compulsive cue-induced behaviors and that they should also be present in individuals with primary CUD.

One concern with respect to the way individual differences in the attribution of incentive salience to cues are assessed is that preclinical studies use behavioral paradigms that are not necessarily translatable to LPP responses (Colaizzi et al., 2020). To investigate sign- and goal-tracking behaviors in humans, some researchers monitor eye movements (Garofalo & di Pellegrino, 2015; Schad et al., 2020). Eye movements are a behavioral marker often used to assess attentional bias toward drug cues in humans (Marks, Pike, et al., 2014; Marks, Roberts, et al., 2014). Specifically, anti-saccade tasks instruct participants to look at the hemifield opposite of a presented stimulus and measure inhibitory visual control (Everling & Fischer, 1998). Attentional bias toward drug cues is operationally defined as a higher anti-saccade error rate for drug cues compared to neutral cues (Dias et al., 2015; Suchting et al., 2020; Tannous et al., 2019; Yoon et al., 2019). We reasoned that if the two LPP reactivity profiles that we identified reflect individual differences in the tendency to attribute incentive salience to drug-related cues, then, in the anti-saccade task, individuals with the C>P profile should have higher attentional bias towards drug cues than individuals with the P>C profile.

This preliminary study had two main aims: 1) to determine if the two neuroaffective profiles (P>C and C>P) that we previously observed in smokers also exist in patients with CUD and 2) if so, to characterize the two groups based on behavioral measures of attentional bias, demographic, self-report, and drug-use history. We hypothesized a) that cluster analysis would reveal the profiles that we observed in smokers and b) that individuals with the C>P profile would show greater attentional bias towards cocaine vs. neutral cues on an anti-saccade test than individuals with the P>C profile. We also performed exploratory analyses on the self-report measures to further characterize the clusters.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

The current study enrolled participants from an ongoing clinical trial (NCT02896712). The study was approved by the local UTHealth IRB (HSC-MS-15-0595) in accord with the ethical principles of Declaration of Helsinki and the Belmont Report. All participants signed written informed consent. In this trial, the participants completed an intake visit to determine eligibility, consisting of a physical, electrocardiogram, self-report questionnaires, and a clinical interview. After consenting, eligible participants completed a week of baseline visits before entering treatment. Eye tracking and EEG data were collected during the baseline week of enrollment, prior to entry into one of the study treatment arms. EEG and eye tracking data were collected during separate sessions during the same baseline week.

Participants

Participants were recruited from the greater Houston area. Eligibility criteria for the EEG sub-study included being between 18-60 years old and meeting DSM-5 criteria for moderate-to- severe CUD, with evidence of current use by submission of a cocaine-positive urine at intake. Additional inclusion criteria included being in acceptable health based on physical and medical history and able to understand the consent form. We excluded individuals who had a current DSM-5 diagnosis for substance use disorder (other than cocaine, cannabis, alcohol, or nicotine) or physical dependence on alcohol requiring detoxification. Additional exclusion criteria included the presence of a medical or mental health condition making participation unsafe, suicidal or homicidal ideation, being on probation or parole, or being pregnant or breastfeeding. To obtain valid EEG recordings, individuals with hairstyles that were incompatible with EEG nets, or who reported a history of epilepsy, seizure disorder, or head injury with loss of consciousness in the last 5 years, were excluded. Forty-five participants consented to the EEG sub-study, but two participants’ recordings were unusable due to collection issues. All analyses except eye tracking (see Methods) reflect a sample size of 43.

Measures

Sample Characteristics.

Sample characteristics including sex, age, race, ethnicity, and years of education were collected via the Addiction Severity Index (ASI; McLellan et al., 1992) during intake. A battery of tests during intake measured affect, emotion regulation, and personality, including the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI; Beck et al., 1996), the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS; Patton et al., 1995), the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz and Roemer, 2004), the Distress Tolerance Scale (DTS; Simons and Gaher, 2005), the Snaith-Hamilton Anhedonia Scale (SHAPS; Snaith et al., 1995), and the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist (PCL; Blevins et al., 2015). Clinical scoring of the SHAPS indicates that a score greater than 2 denotes the presence of anhedonia.

Addiction Severity and Craving.

Recent (number of days in past 30 days) and lifetime (years) use was also collected with the ASI for alcohol, cocaine, and cannabis. Cigarette smoking status was collected using item 1 of the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (Heatherton et al., 1991). Baseline craving was assessed with the Cocaine Craving Questionnaire-Brief (CCQ-b) before participation in the EEG task (Sussner et al., 2006).

Picture Viewing Task.

Participants completed a Picture Viewing Task while we continuously collected EEG. During the task, participants viewed a slideshow of images depicting pleasant [PLE], unpleasant [UNP], cocaine cues [CC], and neutral [NEU] naturalistic scenes. Pleasant and unpleasant images were divided into three semantic content subcategories, including: Erotic (ERO; high arousing pleasant), Romantic (ROM; low arousing pleasant), Sweet Foods (SWE; low arousing pleasant), Mutilations (MUT; high arousing unpleasant), Violence (VIO; low arousing unpleasant), and Accidents (ACC; low arousing unpleasant). The NEU category consisted of neutral objects (NO) and neutral people (NP). Each image was presented on the screen for 4 seconds followed by a black screen with a white fixation cross in the center and were separated by an ITI averaging 3750-ms. Stimuli were presented with E-Prime 2 Professional software (Pittsburg, PA). Each subcategory consisted of 16 images (total = 144) selected from the International Affective Picture System1 (IAPS) (Bradley & Lang, 1994), and from previous work on the LPP (Dunning et al., 2011; Moeller et al., 2012; Parvaz et al., 2017; Versace et al., 2016).

Eye-tracking Task.

Details regarding the eye-tracking task are described in detail in the supplementary materials and in previous studies (Dias et al., 2015). To summarize, participants were tested with an infrared binocular eye-tracker on pro-saccade and drug-specific anti-saccade trials. Participants performed four (2 pro-saccade, 2 anti-saccade) counterbalanced blocks of 24 trials each. Low error rates on the pro-saccade task indicate that there is no gross pathology to retinal nerves, visual cortex, or frontal eye fields and that the participants are following instructions. Images included cocaine-related and neutral images matched as closely as possible for color and complexity. Dependent measures included 1) overall error rate on all anti-saccade trials (error rate) and 2) the ratio of anti-saccade errors on cocaine trials to total anti-saccade errors on all trials (attentional bias). Higher overall error rate indicates failure in visual inhibitory control (Dias et al., 2015; Suchting et al., 2020; Tannous et al., 2019). Attentional bias was calculated as errors on cocaine-stimulus trial divided by total errors, whereby a value greater than 0.50 indicates visual inhibitory failures specific to cocaine-related stimuli (i.e., more than 50% of errors occurring on cocaine-stimulus trials (Dias et al., 2015; Yoon et al., 2019). Due to participant scheduling and equipment failures, a total of 35 participants completed both the EEG and eye-tracking tasks; as such, analyses with eye-tracking data reflect this sample size.

EEG Acquisition & Analysis

EEG data were acquired using a 64-channel actiCAP active electrode cap, amplified with BrainAmp MR and digitized using Brain Vision Recorder (Brain Products, Munich). Before collection, impedances were maintained below 100 kΩ to ensure clean data. Data were referenced to FCz, sampled at a rate of 500 Hz and filtered with a .1 Hz high-pass and 100 Hz low-pass filters. After collection, data were re-referenced to the average reference. We corrected eye movements and blinks using a spatial filtering method as implemented in BESA 6.1 (MEGIS Software GmbH, Grafelfing, Germany). The data were further analyzed using Brain Vision Analyzer 2.2 (Brain Products GmbH). The data were filtered with a .1Hz lowpass and 40Hz highpass filter and EEG data were segmented into 1100ms epochs beginning 100ms before and ending 1000ms after the onset of the images. The data were baseline corrected to the 100ms pre-stimulus period and, for each segment, channels contaminated by artifacts were identified using the following criteria: a voltage step >10 μV/ms, a maximal voltage difference >70 μV over a 50 ms period, < 0.5 μV activity over a 100 ms interval, or EEG amplitudes above 50 μV or below −50 μV. Channels contaminated by artifacts in more than 40% of the segments were interpolated using Hjorth Laplacian Method (Hjorth, 1980). If, after interpolation, a segment had more than 10% of the sensors contaminated by artifacts, it was not included in the average. Each subcategory averaged 13 good segments per subject. To avoid biasing measurements and analyses (Luck & Gaspelin, 2017), in line with the literature and our previous studies (Frank et al., 2020; Parvaz et al., 2017; Versace et al., 2019), we a priori defined the LPP as the mean amplitude between 400-800ms post-stimulus over centro-parietal electrodes. Figure 1B displays the averaged electrodes. Averages per category (PLE, UNP, CC, and NEU) were calculated for each participant. We also calculated averages for each subcategory (ERO, ROM, SWE, MUT, VIO, and ACC).

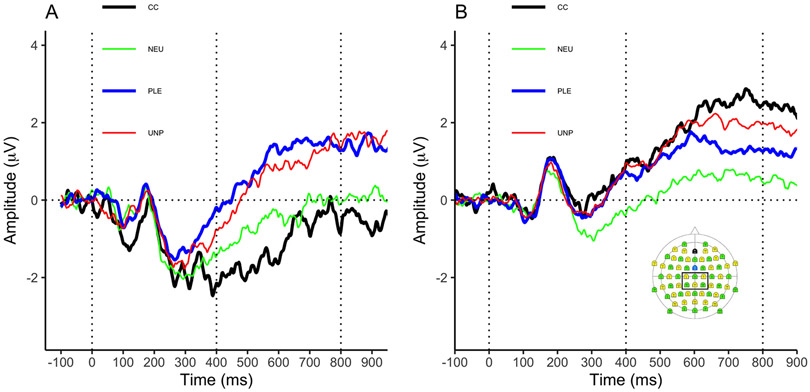

Fig1.

Individuals in cluster 1 had larger ERP responses to cocaine images than pleasant images. Individuals in cluster 2 had the opposite pattern. A. LPP responses in cluster 1 P>C. B. LPP responses in cluster 2 (C>P) and the montage of electrodes selected to define the LPP. Thick dark line – cocaine, thin light line = neutral, thick medium line = pleasant, and thin medium line = unpleasant.

Data Analysis Strategy

To evaluate the primary hypothesis and determine whether the P>C and C>P neuroaffective profiles also exist in those with CUD (aim 1), we followed the same procedure of our previous studies: We entered the LPP values from the main categories (PLE, UNP, CC, and NEU) into a k-means clustering algorithm with the a priori number of clusters set to k=2. This value was based on several previous studies that have found a two-group solution for LPP values best partitions the data space for smokers on this EEG task (Engelmann et al., 2016; Versace et al., 2012, 2016, 2019). However, as due diligence, alternative numbers of clusters (k = 3 to 6) were evaluated for superior optimization. This data-driven search for the optimal number of clusters largely corroborated the hypothesis-driven choice of k=2. An equal number of the different optimization indices (e.g., silhouette plot, gap statistic) supported the values of k=2 through 4 (with no support for higher values); as such, the most parsimonious value (k=2) was considered optimal for the present analysis. Prior to clustering, LPP values were standardized within subjects to account for individual differences in absolute voltage. To investigate the nature of the differences between clusters, we performed a factorial ANOVA with cluster (P>C vs. C>P) as a between-subjects factor and category (PLE, UNP, CC, and NEU) as a within-subjects factor and LPP amplitude as the outcome variable. It is important to note that k-means clustering creates groups by maximizing the between groups variance and minimizing the within groups variance, hence by default yielding a significant cluster by category interaction. However, what is key for our hypothesis is not the significance level of this interaction, but its shape: are the two groups created by k-means clustering showing the P>C and the C>P profiles? To evaluate the neuroaffective reactivity profiles, we tested within group differences among categories (Frank et al., 2020) using pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni corrected p-values (the p-value multiplied by the number of tests per SPSS 26, IBM). Furthermore, to investigate how reactivity to specific semantic contents differed by cluster membership, we conducted an additional ANOVA with cluster as a between-subjects factor and subcategory (ERO, ROM, SWE, MUT, VIO, ACC, CC, and NEU) as a within-subjects factor. Again, we compared reactivity among subcategories within each cluster using Bonferroni corrected pairwise comparisons.

Finally, to characterize the two clusters (aim 2), we evaluated group differences across demographic, and psychometric measures. As this was an exploratory aim, we did not correct significance levels for multiple tests. Chi-square tests and independent samples t-tests were performed for categorical and continuous measures, respectively, using the R statistical computing environment (R Core Team, 2020). Non-normally distributed continuous data were modeled using Mann-Whitney tests via the R package coin (Hothorn et al., 2008).

Results

Cluster Analysis

The cluster analysis assigned 18 (41.86%) participants to cluster 1 and 25 (58.14%) participants to cluster 2. LPP waveforms by cluster are presented in Figure 1. As expected, using cluster as a between-subjects factor, the cluster by category interaction was significant (F(3,123) = 20.698, p < 0.001, partial η2 = .335). Importantly, pairwise comparisons supported our hypothesis about the shape of this interaction: Within both groups, pleasant and unpleasant stimuli evoked LPPs significantly larger than neutral ones (cluster 1, PLE>NEU, p < .001, UNP>NEU: p = .021, cluster 2, PLE>NEU, p = .001, UNP>NEU: p < .001). However, in cluster 1, pleasant stimuli elicited larger LPPs than cocaine-related ones (p < 0.001, d = 1.70), whereas within cluster 2, cocaine-related stimuli elicited larger LPPs than pleasant stimuli (p = 0.043, d = 0.56), but similar to unpleasant stimuli (p = 1.00, d = 0.17). Means and standard deviations are presented in Table 2. These results support the hypothesis that two distinct groups of cocaine users exist based on neural responses to emotional stimuli vs. cocaine cues (Figure 2A). Following the convention of our previous studies, we labeled the two clusters C>P and P>C.

Table 2.

LPP Amplitudes by Cluster Membership

| P>C | C>P | |

|---|---|---|

| Image Type | Mean(SD) | Mean(SD) |

| Neutral | −0.51(1.46) | 0.41(1.40) |

| Pleasant | 0.99(1.14) | 1.21(1.79) |

| Erotic | 2.35(2.07) | 2.25(2.35) |

| Romantic | 0.41(1.93) | 0.86(1.77) |

| Sweet foods | 0.22(1.18) | 0.54(1.65) |

| Unpleasant | 0.65(1.42) | 1.67(1.63) |

| Mutilations | 1.45(1.57) | 2.28(2.36) |

| Violence | .55(1.85) | 1.67(2.32) |

| Accidents | .05(1.45) | 1.05(1.84) |

| Cocaine | −1.18(1.61) | 1.95(1.70) |

Note. LPP = Late positive potential, P>C = pleasant greater than cocaine, C>P = cocaine greater than pleasant

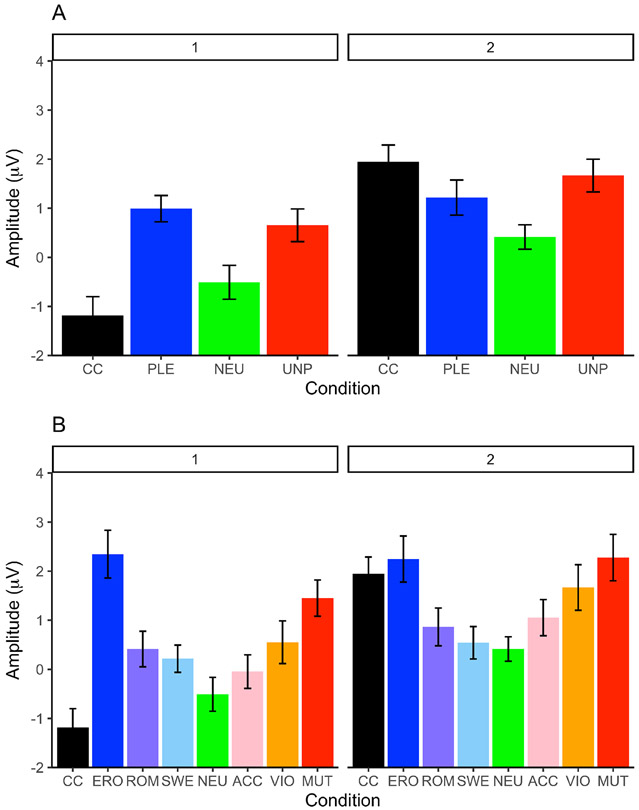

Fig2.

Late positive potential (LPP) means by condition and cluster. A. LPP means for the main categories. Cluster 1 (P>C) is displayed on the left and cluster 2 (C>P) is displayed on the right. CC = cocaine, PLE = pleasant, NUP = unpleasant, NEU = neutral. B. LPP means for the semantic contents. Cluster 1 is displayed on the left and cluster 2 is displayed on the right. CC = cocaine, ERO = erotic, ROM = romantic, SWE = sweet foods, NEU = neutral, ACC = accidents, VIO = violence, MUT = mutilations.

Further characterizing the nature of the clusters, the interaction between cluster and subcategory (F(7,287) = 5.996, p < 0.001, partial η2 = .128) showed that in both groups, both pleasant and unpleasant contents increased the amplitude of the LPP as a function of their motivational relevance. However, the within clusters pairwise comparisons showed that within the P>C group, CC elicited LPPs that were similar to those evoked by NEU (and significantly (p’s < 0.05) lower than those elicited by all pleasant subcategories and the MUT and VIO unpleasant subcategories), while, within the C>P group, CC elicited LPPs that were similar to those evoked by ERO, MUT, VIO, and ACC subcategories (and significantly (p’s < 0.05) higher than NEU, SWE, and ROM) (Figure 2B and Table 2).

Characterization of Clusters

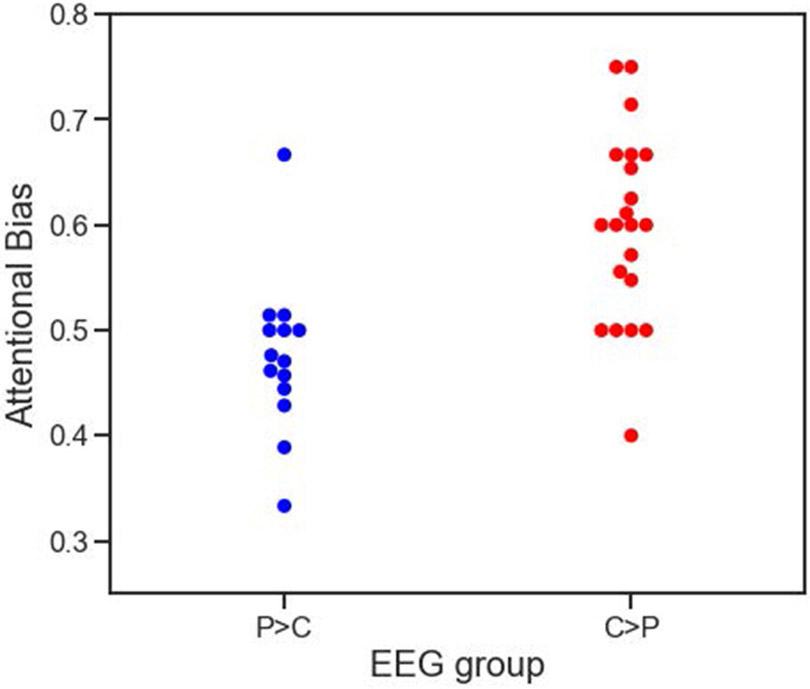

On the anti-saccade task, overall error rates were similar between the two clusters in both pro-saccade and anti-saccade trial types. For pro-saccades, the overall error rates were very low, indicating participants were following instructions and there was no gross pathology in the visual circuitry. The mean proportion of pro-saccade errors for C>P and P>C, respectively, were 0.018 (SD = 0.027) and 0.026 (0.034), t(33) = 0.774, p = 0.444, d = 0.26.. For anti-saccades, the overall error rates were higher and similar to those recorded in previous studies with CUD participants (Dias et al., 2015; Tannous et al., 2019). The mean proportion of anti-saccade errors for C>P and P>C, respectively, were 0.436 (SD = 0.251) and 0.50 (0.253), t(33) = −0.728, p = 0.472, d = 0.25. Importantly, supporting the hypothesis that the two neuroaffective profiles reflect individual differences in the tendency to attribute incentive salience to cocaine-related cues, the attentional bias on the anti-saccade trials differed between the two clusters (Figure 3). Individuals classified as C>P (M = 0.599, SD = 0.090) displayed greater attentional bias toward cocaine cues than individuals classified as P>C (M = 0.475, SD = 0.075), t(34) = 5.52, p < .001, d = 1.50.

Fig3.

Attentional bias was increased in cluster 2 compared to cluster 1 on the eye-tracking task. Attentional bias reflects the proportion of error rates on drug trials compared with neutral trials. P>C = pleasant greater than cues and C>P = cues greater than pleasant.

Demographic, psychometric, and drug use tests are presented in Table 1. Considering the exploratory nature of these analyses, results were not corrected for multiple comparisons. The groups did not differ on any demographic characteristic as well as most psychometric measures. The groups also did not differ on baseline craving or any addiction severity variable, but they did differ on self-reported anhedonia (SHAPS), distress tolerance (DTS), and posttraumatic stress symptoms (PCL), with individuals classified as C>P reporting greater anhedonic and posttraumatic stress symptoms and less distress tolerance than individuals classified as P>C.

Table 1.

Demographic, Baseline Psychometric Characteristics, and Drug Use by Cluster Membership

| Characteristic | Total (N = 43) % (N) |

Cluster 1 (n

= 18) % (N) |

Cluster 2 (n

= 25) % (N) |

p-value | Effect size |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.18 | 0.20b | ||||

| Female | 14.0(6) | 22.2(4) | 8.0(2) | |||

| Race | 0.14 | 0.30c | ||||

| African-American | 86.0(37) | 77.8(14) | 92.0(23) | |||

| White | 11.6(5) | 22.2(4) | 4.0(1) | |||

| Not reported | 2.3(1) | 0(0) | 4.0(1) | |||

| Ethnicity | 0.37 | 0.14b | ||||

| Not Hispanic | 93.0(40) | 88.9(16) | 96.0(24) | |||

| Smoker | 79.1(34) | 72.2(13) | 84.0(21) | 0.35 | 0.14b | |

| Mean(SD) | Mean(SD) | Mean(SD) | ||||

| Age | 51.6(6.6) | 49.6(7.6) | 53.1(5.4) | 0.10 | 0.54 | |

| Education (years) | 12.5(1.5) | 12.3(1.7) | 12.7(1.4) | 0.41 | 0.26 | |

| BDI | 14.3(12.6) | 10.7(11.3) | 17.0(13.0) | 0.10 | 0.52 | |

| BIS | 61.1(9.5) | 60.7(7.9) | 61.4(10.7) | 0.82 | 0.07 | |

| DERS | 86.3(17.9) | 85.3(20.0) | 86.9(16.6) | 0.79 | 0.09 | |

| DTS | 42.1(13.2) | 48.3(13.1) | 37.6(11.6) | 0.01 | 0.87 | |

| SHAPS | 2.4(3.1) | 1.2(2.0) | 3.2(3.5) | 0.02 a | 0.37d | |

| PCL | 19.4(15.2) | 12.8(12.2) | 24.1(15.7) | 0.01 | 0.80 | |

| Drug Use | Mean(SD) | Mean(SD) | Mean(SD) | |||

| CCQ | 2.9(1.0) | 2.5(0.8) | 3.1(1.1) | 0.06 | 0.59 | |

| Alcohol use | Recent (days) | 7.9(9.8) | 7.0(9.7) | 8.6(9.9) | 0.86a | 0.03d |

| Lifetime (years) | 17.2(13.4) | 15.1(12.1) | 18.8(14.4) | 0.37 | 0.28 | |

| Cocaine use | Recent (days) | 19.5(9.1) | 18.2(10.5) | 20.5(8.1) | 0.43 | 0.25 |

| Lifetime (years) | 19.3(9.7) | 21.4(8.5) | 17.8(10.3) | 0.21 | 0.39 | |

| Cannabis use | Recent (days) | 5.4(9.1) | 8.6(11.8) | 3.1(5.6) | 0.26a | 0.17d |

| Lifetime (years) | 15.5(13.1) | 18.3(12.4) | 13.6(13.4) | 0.24 | 0.21 | |

Note. p-values estimated by chi-square (categorical measures) or independent t-tests (continuous measures)

(Mann-Whitney tests for non-normally distributed continuous data). All frequencies were calculated within group (column). “Smoker” defined as responding "TRUE" for item 1 of Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory II; BIS = Barrat Impulsiveness Scale; DERS = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale; DTS = Distress Tolerance Scale; SHAPS = Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale; PCL = Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist; CCQ = Cocaine Craving Questionnaire. Alcohol, Cocaine, and Cannabis use assessed by Addiction Severity Index (ASI) items D1, D8, and D10, respectively. Effect sizes calculated in Cohen’s d except where indicated

Phi (2x2 contingency tables)

Cramer’s V (larger than 2x2 contingency tables) for categorical measures

r for Mann-Whitney tests for non-normally distributed continuous data.

Discussion

The current study sought to determine if neuroaffective reactivity profiles (hypothesized to be associated with individual differences in the tendency to attribute incentive salience to drug-related cues) that we previously observed in smokers also exist in patients with primary CUD. Replicating previous findings (Versace et al., 2012, 2019), we showed that applying k-means clustering to the LPP responses evoked by a wide array of cocaine-related and non-drug-related motivationally relevant stimuli allowed us to isolate two groups characterized by the hypothesized brain reactivity profiles. One group (C>P) displayed enhanced LPP responses to cocaine images compared to pleasant images, while the other (P>C) displayed enhanced LPP responses to pleasant images compared to cocaine images. The results from the anti-saccade task converged with the neurophysiological findings: Individuals with the C>P had displayed an increased attentional bias toward cocaine cues compared to individuals with the P>C profile. Hence, the observed neurobehavioral outcomes observed support the hypothesis that the two neurophysiological response profiles that we identified reflect individual differences in the tendency to attribute incentive salience to drug-related cues.

Several conclusions can be drawn from these results. First, the two neurophysiological profiles are robust and reproducible across populations with different addictive disorders irrespective of the specific substance of abuse. The profiles described here have been identified in young smokers (Engelmann et al., 2016), adult smokers (Versace et al., 2012), obese individuals (Versace et al., 2016) and people susceptible to cue-induced eating (Versace et al., 2019). Overall, these data suggest that a common mechanism might modulate neural response to drug-related cues vs. other non-drug-related motivationally relevant stimuli. The exact nature of this mechanism remains to be determined: Are the two neuroaffective reactivity profiles due to individual differences in reactivity to drug-related cues, to non-drug-related pleasant stimuli, or to both? When we initially isolated these neurobehavioral profiles in smokers (Versace et al., 2012, 2014), the presence of between groups significant differences in reactivity to pleasant but not unpleasant stimuli led us to hypothesize that low hedonic capacity might have been the psychological mechanism underlying the C>P profile. However, the results from this experiment did not yield clear between group differences in reactivity to pleasant stimuli (supplementary materials). Moreover, even though individuals in the C>P group reported higher anhedonia scores than individuals in the P>C group (but this difference was significant only with no correction for multiple comparisons), attributing the C>P profile to blunted reactivity to pleasant stimuli seems at odds with the observation that, within the C>P group, LPP responses evoked by pleasant stimuli are only slightly lower than those evoked by unpleasant ones. Given that the LPP is a reliable measure of a stimulus’ motivational relevance rather than its hedonic impact, it is likely that determining how individual differences in hedonic capacity contribute to the two neuroaffective profiles will require measuring responses from brain regions specifically sensitive to rewards using fMRI.

Regardless of the role that hedonic capacity might play in modulating LPP responses to pleasant stimuli, we believe that these LPP findings can be explained by individual differences in the tendency to attribute incentive salience to cocaine-related cues relative to other non-drug-related motivationally relevant stimuli. This interpretation dovetails with the behavioral results from the eye-tracking task: cocaine users characterized by the C>P profile had greater difficulty disengaging attention from drug-related cues than individuals characterized by the P>C profile. Hence our results are in line with theoretical models and empirical findings (Robinson & Berridge, 2001; Saunders & Robinson, 2013) showing that individuals that attach high incentive salience to cues (as indexed by LPP) also have a stronger attentional bias towards them (as indexed by eye movements).

Second, within both groups, the neurophysiological response patterns to the non-drug-related affective subcategories were similar and comparable to those previously reported in the literature (Minnix et al., 2013; Schupp et al., 2004; Weinberg & Hajcak, 2010). Irrespective of their hedonic value, images with higher motivational relevance, prompted larger LPP responses. Notwithstanding the two groups’ substantially similar neuroaffective responses to emotional stimuli, self-report affective measures highlighted some differences between them. Individuals in the C>P cluster reported lower distress tolerance, more PTSD symptoms, and higher anhedonia, than individuals in the P>C group. Previous research has shown that lower distress tolerance is related to drug use and to lower control and safety in response to drug cues (Vujanovic et al., 2018), higher PTSD symptomatology might be associated with higher LPP responses to unpleasant images (Lobo et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2015) and greater anhedonia in major depressive disorder might be associated with smaller LPP responses to pleasant pictures (Klawohn et al., 2019). However, none of these studies took into account the role that individual neuroaffective reactivity profiles might play in these differences. Furthermore, in our previous studies, the two groups did not differ in self-reports of hedonic capacity, instead, impulsivity was higher in the C>P cluster (Versace et al., 2019). Due to the exploratory nature of the analyses that we conducted on the psychometric measures, and the inconsistencies of the self-report results across studies, the findings reported here should be replicated with larger samples.

Third, the two neuroaffective profiles do not simply reflect demographic characteristics: The two groups were not different in age, sex, race, as well as lifetime and recent cocaine use, addiction severity, or craving. This finding is in line with what we observed in previous studies that enrolled smokers. Demographic variables, measures of addiction severity, and tonic craving are not designed to capture differences in the tendency to attribute incentive salience to drug-related cues relative to other motivationally relevant stimuli. Therefore, assessing LPP responses to a wide array of stimuli can provide clinically relevant information that cannot be measured with typical self-report variables. Future studies should test the extent to which cluster membership predicts treatment outcomes above and beyond what demographic, addiction severity, and craving variables can do. Future studies should further try to integrate these measures to help clinicians better predict outcomes and develop tailored treatments for substance abuse.

The current study was not without limitations. First, we were unable to examine sex differences, as the sample was primarily male; however, previous research has indicated that the proportion of males and females does not differ between clusters (Versace et al., 2016). Second, as neuroanatomical specificity is not optimal with EEG measurements, future studies would benefit from combining brain imaging and pharmacological manipulations or targeted transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to establish the mechanism underlying the LPP reactivity profiles that we isolated. Third, it should be noted that hard clustering methods like k-means do not provide an estimate of the uncertainty of the classification outcome. Assuming that cluster membership is known without error and propagating this assumption to the subsequent analytic steps can increase the risk of Type I errors. When a larger sample will be available, we plan to address this issue by using Bayesian clustering approaches, as these methods can take into account uncertainty in both cluster membership and cluster number. It is encouraging to note that when we used a Bayesian Dirichlet process mixture model to re-evaluate the classification outcomes of our previous studies in smokers (357 individuals), we successfully replicated the same two cluster solution that we found here (Kypriotakis et al., 2020). Fourth, unlike the EEG task, the anti-saccade task did not include pleasant and unpleasant images, preventing us from directly comparing the attentional bias towards drug-related and non-drug-related motivationally relevant stimuli. By including the full spectrum of emotional images in the anti-saccade task, future studies will better characterize the relationship between neurophysiological and behavioral responses to cues and rewards. Finally, we were unable to examine the relationship between cluster membership and treatment outcomes due to 1) the limited sample size and 2) issues related to unblinding of the clinical trial, as the data was collected within the context of an ongoing clinical trial. The present research found evidence for a two-cluster partition in individuals with CUD, but future work in this population should investigate the extent to which these cluster profiles predict difficulty in quitting and/or remaining abstinent.

Notwithstanding these limitations, we demonstrated that individual differences in neuroaffective responses to drug-related and non-drug-related motivationally relevant stimuli characterize cocaine users and, using an anti-saccade task, we showed that these psychophysiological differences are associated with differences in attentional bias toward drug-related cues. Although future research is needed to test if these profiles predict success in treatment for CUD, ERPs may provide useful information in clinical trials and addiction medicine (Houston & Schlienz, 2018; Moeller & Paulus, 2018; Stewart & May, 2016). The differences that we isolated with this paradigm could be used to tailor CUD treatments, similar to what is already being pursued in smokers (Cinciripini et al., 2017; Frank et al., 2020). As EEG is relatively affordable and easy to implement, measurement of the LPP in clinical settings may provide critical information that can aid in the individualization of treatment plans and improve treatment successes.

Supplementary Material

Public Significance.

Our findings suggest that heterogeneity in psychophysiological responses to cocaine-related and non-cocaine related emotional cues can be linked to behaviors associated with individual differences the tendency to attribute incentive salience to cues. Consideration of these psychophysiological individual differences during treatment may help clinicians tailor treatments and increase treatment success.

Disclosures and Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse F32DA048542 to HEW and R01DA039125 to JMS. The funding source had no other role other than financial support.

The authors would like to acknowledge Sarah McKay and Danielle Kessler for their help with collecting the EEG data.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Some data from this manuscript were presented in poster form at the annual meeting of the Society for Psychophysiological Research in 2020 and at a local conference, the Annual Postdoctoral Research Science Symposium in 2020.

IAPS images were used as follows - NEU: 7000, 7002, 7004, 7006, 7009, 7010, 7030, 7034, 7040, 7041, 7052, 7053, 7054, 7055, 7056, 7059, 2107, 2214, 2235, 2305, 2372, 2383, 2393, 2396, 2435, 2500, 2515, 2579, 2593, 2595, 2597, 2850, ERO: 4611, 4658, 4659, 4669, 4677, 4680, 4687, 4690, 4691, 4693, 4695, 4696, 4698, 4783, 4800, ROM: 2208, 2501, 2550, 4597, 4599, 4600, 4610, 4612, 4616, 4619, 4624, 4625, 4640, 4641, 4643, 4700, SWE: 0004, 0060, 0149, 0177, 7330, 7390, 7405, 7410, 7430, 7470, MUT: 3000, 3030, 3051, 3053, 3060, 3068, 3069, 3080, 3100, 3110, 3120, 2130, 3261, 9420, 9433, VIO: 3530, 6211, 6231, 6242, 6312, 6313, 6315, 6350, 6360, 6510, 6540, 6550, 6560, 6571, 6832, 9414, ACC: 6020, 6230, 6260, 9090, 9110, 9290, 9300, 9301, 9320, 9373, 9560, 9600, 9621, 9901, 9911, 9912

References

- Bacigalupo F, & Luck SJ (2018). Event-related potential components as measures of aversive conditioning in humans. Psychophysiology, 55(4). 10.1111/psyp.13015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A, Steer R, & Brown G (1996). Beck depression inventory -II. 78(2), 490–498. https://m.blog.naver.com/PostView.nhn?blogId=mistyeyed73&logNo=220427762670&proxyReferer=https:%2F%2Fscholar.google.com%2F [Google Scholar]

- Bedi G, Preston KL, Epstein DH, Heishman SJ, Marrone GF, Shaham Y, & De Wit H (2011). Incubation of cue-induced cigarette craving during abstinence in human smokers. Biological Psychiatry, 69(7), 708–711. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge KC (2012). From prediction error to incentive salience: Mesolimbic computation of reward motivation. European Journal of Neuroscience, 35(7), 1124–1143. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.07990.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins CA, Weathers FW, Davis MT, Witte TK, & Domino JL (2015). The Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5): Development and Initial Psychometric Evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(6), 489–498. 10.1002/jts.22059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley MM (2009). Natural selective attention: Orienting and emotion. Psychophysiology, 46(1), 1–11. 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2008.00702.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley MM, Hamby S, Löw A, Löw L, & Lang PJ (2007). Brain potentials in perception: Picture complexity and emotional arousal. 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00520.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley MM, & Lang PJ (1994). Measuring Emotion: The Self-Assessment Manikin and the Semantic Differential. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 25(I), 49–59. 10.1016/0005-7916(94)90063-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinciripini PM, Green CE, Robinson JD, Karam-Hage M, Engelmann JM, Minnix JA, Wetter DW, & Versace F (2017). Benefits of varenicline vs. bupropion for smoking cessation: a Bayesian analysis of the interaction of reward sensitivity and treatment. Psychopharmacology, 234(11), 1769–1779. 10.1007/s00213-017-4580-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codispoti M, de Cesarei A, & Ferrari V (2012). The influence of color on emotional perception of natural scenes. Psychophysiology, 49(1), 11–16. 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2011.01284.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codispoti M, Mazzetti M, & Bradley MM (2009). Unmasking emotion: Exposure duration and emotional engagement. 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2009.00804.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codispoti M, Micucci A, & de Cesarei A (2020). Time will tell: Object categorization and emotional engagement during processing of degraded natural scenes. Psychophysiology. 10.1111/psyp.13704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colaizzi JM, Flagel SB, Joyner MA, Gearhardt AN, Stewart JL, & Paulus MP (2020). Mapping sign-tracking and goal-tracking onto human behaviors. In Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews (Vol. 111, pp. 84–94). Elsevier Ltd. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.01.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Cesarei A, & Codispoti M (2006). When does size not matter? Effects of stimulus size on affective modulation. Psychophysiology, 43(2), 207–215. 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2006.00392.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Cesarei A, & Codispoti M (2011). Scene identification and emotional response: Which spatial frequencies are critical? Journal of Neuroscience, 31(47), 17052–17057. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3745-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deweese MM, Codispoti M, Robinson JD, Cinciripini PM, & Versace F (2018). Cigarette cues capture attention of smokers and never-smokers, but for different reasons. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 185, 50–57. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.12.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias NR, Schmitz JM, Rathnayaka N, Red SD, Sereno AB, Moeller FG, & Lane SD (2015). Anti-saccade error rates as a measure of attentional bias in cocaine dependent subjects. Behavioural Brain Research, 292, 493–499. 10.1016/j.bbr.2015.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunning JP, Parvaz MA, Hajcak G, Maloney T, Alia-Klein N, Woicik PA, Telang F, Wang GJ, Volkow ND, & Goldstein RZ (2011). Motivated attention to cocaine and emotional cues in abstinent and current cocaine users - an ERP study. European Journal of Neuroscience, 33(9), 1716–1723. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07663.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelmann JM, Versace F, Gewirtz JC, & Cinciripini PM (2016). Individual differences in brain responses to cigarette-related cues and pleasant stimuli in young smokers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 163, 229–235. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.04.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelmann JM, Versace F, Robinson JD, Minnix JA, Lam CY, Cui Y, Brown VL, & Cinciripini PM (2012). Neural substrates of smoking cue reactivity: A meta-analysis of fMRI studies. In Neuroimage (Vol. 60, Issue 1, pp. 252–262). NIH Public Access. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.12.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everling S, & Fischer B (1998). The antisaccade: A review of basic research and clinical studies. Neuropsychologia, 36(9), 885–899. 10.1016/S0028-3932(98)00020-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari V, Bradley MM, Codispoti M, & Lang PJ (2010). Detecting novelty and significance. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 22(2), 404–411. 10.1162/jocn.2009.21244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flagel SB, Clark JJ, Robinson TE, Mayo L, Czuj A, Willuhn I, Akers CA, Clinton SM, Phillips PEM, & Akil H (2011). A selective role for dopamine in stimulus-reward learning. Nature, 469(1328), 53–59. 10.1038/nature09588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaisch T, Junghöfer M, Bradley MM, Schupp HT, & Lang PJ (2008). Rapid picture processing: Affective primes and targets. Psychophysiology, 45(1), 1–10. 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00600.X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank DW, Cinciripini PM, Deweese MM, Karam-Hage M, Kypriotakis G, Lerman C, Robinson JD, Tyndale RF, Vidrine DJ, & Versace F (2020). Toward Precision Medicine for Smoking Cessation: Developing a Neuroimaging-Based Classification Algorithm to Identify Smokers at Higher Risk for Relapse. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 22(8), 1277–1284. 10.1093/ntr/ntz211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garofalo S, & di Pellegrino G (2015). Individual differences in the influence of task-irrelevant Pavlovian cues on human behavior. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 9(June), 163. 10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, & Roemer L (2004). Multidimensional Assessment of Emotion Regulation and Dysregulation: Development, Factor Structure, and Initial Validation of the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale 1. In Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment (Vol. 26, Issue 1). [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, & Fagerström K-O (1991). The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction, 86(9), 1119–1127. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins ST, Badger GJ, & Budney AJ (2000). Initial abstinence and success in achieving longer term cocaine abstinence. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 8(3), 377–386. 10.1037/1064-1297.8.3.377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjorth B (1980). Source derivation simplifies topographical EEG interpretation. American Journal of EEG Technology, 20(3), 121–132. 10.1080/00029238.1980.11080015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hothorn T, Van De Wiel MA, Hornik K, & Zeileis A (2008). Implementing a class of permutation tests: The coin package. Journal of Statistical Software, 28(8), 1–23. 10.18637/jss.v028.i0827774042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Houston RJ, & Schlienz NJ (2018). Event-Related Potentials as Biomarkers of Behavior Change Mechanisms in Substance Use Disorder Treatment. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 3(1), 30–40. 10.1016/J.BPSC.2017.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John WS, & Wu LT (2017). Trends and correlates of cocaine use and cocaine use disorder in the United States from 2011 to 2015. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 180, 376–384. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.08.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keil A, Bradley MM, Hauk O, Rockstroh B, Elbert T, & Lang PJ (2002). Large-scale neural correlates of affective picture processing. Psychophysiology, 39(5), 641–649. 10.1017/S0048577202394162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klawohn J, Burani K, Bruchnak A, Santopetro N, & Hajcak G (2019). Reduced neural response to reward and pleasant pictures independently relate to depression. Psychological Medicine, 1–9. 10.1017/S0033291719003659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kypriotakis G, Cinciripini PM, & Versace F (2020). Modeling neuroaffective biomarkers of drug addiction: A Bayesian nonparametric approach using dirichlet process mixtures. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 341(May). 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2020.108753 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ, & Bradley MM (2010). Emotion and the motivational brain. Biological Psychology, 84(3), 437–450. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Huang H, McGinnis-Deweese M, Keil a., & Ding M (2012). Neural Substrate of the Late Positive Potential in Emotional Processing. Journal of Neuroscience, 32(42), 14563–14572. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3109-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobo I, David IA, Figueira I, Campagnoli RR, Volchan E, Pereira MG, & de Oliveira L (2014). Brain reactivity to unpleasant stimuli is associated with severity of posttraumatic stress symptoms. Biological Psychology. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2014.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luck SJ, & Gaspelin N (2017). How to get statistically significant effects in any ERP experiment (and why you shouldn’t). Psychophysiology, 54(1), 146–157. 10.1111/psyp.12639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks KR, Pike E, Stoops WW, & Rush CR (2014). Test-retest reliability of eye tracking during the visual probe task in cocaine-using adults. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 145, 235–237. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.09.784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks KR, Roberts W, Stoops WW, Pike E, Fillmore MT, & Rush CR (2014). Fixation time is a sensitive measure of cocaine cue attentional bias. Addiction, 109(9), 1501–1508. 10.1111/add.12635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, Pettinati H, & Argeriou M (1992). The fifth edition of the addiction severity index. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 9(3), 199–213. 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Micucci A, Ferrari V, de Cesarei A, & Codispoti M (2019). Contextual modulation of emotional distraction: Attentional capture and motivational significance. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 32(4), 621–633. 10.1162/jocn_a_01505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minnix JA, Versace F, Robinson JD, Lam CY, Engelmann JM, Cui Y, Brown VL, & Cinciripini PM (2013). The late positive potential (LPP) in response to varying types of emotional and cigarette stimuli in smokers: A content comparison. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 89(1), 18–25. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.04.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller SJ, Hajcak G, Parvaz MA, Dunning JP, Volkow ND, & Goldstein RZ (2012). Psychophysiological prediction of choice: Relevance to insight and drug addiction. Brain, 135(11), 3481–3494. 10.1093/brain/aws252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller SJ, & Paulus MP (2018). Toward biomarkers of the addicted human brain: Using neuroimaging to predict relapse and sustained abstinence in substance use disorder. In Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry (Vol. 80, Issue Pt B, pp. 143–154). Elsevier Inc. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olofsson JK, Nordin S, Sequeira H, & Polich J (2008). Affective picture processing: An integrative review of ERP findings. Biological Psychology, 77(3), 247–265. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.11.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvaz MA, Moeller SJ, & Goldstein RZ (2016). Incubation of cue-induced craving in adults addicted to cocaine measured by electroencephalography. JAMA Psychiatry, 73(11), 1127–1134. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parvaz MA, Moeller SJ, Malaker P, Sinha R, Alia-Klein N, & Goldstein RZ (2017). Abstinence reverses EEG-indexed attention bias between drug-related and pleasant stimuli in cocaine-addicted individuals. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 42(2), 78–86. 10.1503/jpn.150358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, & Barratt ES (1995). Factor structure of the barratt impulsiveness scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 51(6), 768–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomara C, Cassano T, D’Errico S, Bello S, Romano AD, Riezzo I, & Serviddio G (2012). Data available on the extent of cocaine use and dependence: biochemistry, pharmacologic effects and global burden of disease of cocaine abusers. Current Medicinal Chemistry, 19(33), 5647–5657. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22856655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, & Berridge KC (1993). The neural basis of drug craving: An incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. In Brain Research Reviews (Vol. 18, Issue 3, pp. 247–291). 10.1016/0165-0173(93)90013-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson TE, & Berridge KC (2001). Mechanisms of Action of Addictive Stimuli Incentive-sensitization and addiction. Addiction, 96(1), 103–114. 10.1080/09652140020016996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders BT, & Robinson TE (2010). A Cocaine Cue Acts as an Incentive Stimulus in Some but not Others: Implications for Addiction. Biological Psychiatry, 67(8), 730–736. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders BT, & Robinson TE (2013). Individual variation in resisting temptation: Implications for addiction. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 37(9), 1955–1975. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2013.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayegh CS, Huey SJ, Zara EJ, & Jhaveri K (2017). Follow-up treatment effects of contingency management and motivational interviewing on substance use: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31(4), 403–414. 10.1037/adb0000277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schad DJ, Rapp MA, Garbusow M, Nebe S, Sebold M, Obst E, Sommer C, Deserno L, Rabovsky M, Friedel E, Romanczuk-Seiferth N, Wittchen HU, Zimmermann US, Walter H, Sterzer P, Smolka MN, Schlagenhauf F, Heinz A, Dayan P, & Huys QJM (2020). Dissociating neural learning signals in human sign- and goal-trackers. Nature Human Behaviour, 4(2), 201–214. 10.1038/s41562-019-0765-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schupp H, Cuthbert BN, Bradley MM, Cacioppo JT, Tiffany I, & Lang PJ (2000). Affective picture processing: The late positive potential is modulated by motivational relevance. Psychophysiology, 37(2), 257–261. 10.1017/S0048577200001530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schupp H, Cuthbert BN, Bradley MM, Hillman CH, Hamm AO, & Lang PJ (2004). Brain processes in emotional perception: Motivated attention. Cognition and Emotion, 18(5), 593–611. 10.1080/02699930341000239 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schupp H, Flaisch T, Stockburger J, Jungho M, & Junghoefer M (2006). Emotion and attention: event-related brain potential studies. Progress in Brain Research, 156, 31–51. 10.1016/S0079-6123(06)56002-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons JS, & Gaher RM (2005). The distress tolerance scale: Development and validation of a self-report measure. In Motivation and Emotion (Vol. 29, Issue 2, pp. 83–102). Springer. 10.1007/s11031-005-7955-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha R, & Li CSR (2007). Imaging stress- and cue-induced drug and alcohol craving: Association with relapse and clinical implications. In Drug and Alcohol Review (Vol. 26, Issue 1, pp. 25–31). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 10.1080/09595230601036960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snaith RP, Hamilton M, Morley S, Humayan A, Hargreaves D, & Trigwell P (1995). A scale for the assessment of hedonic tone. The Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale. British Journal of Psychiatry, 167(1), 99–103. 10.1192/bjp.167.1.99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart JL, & May AC (2016). Electrophysiology for addiction medicine: From methodology to conceptualization of reward deficits. In Progress in Brain Research (Vol. 224, pp. 67–84). 10.1016/bs.pbr.2015.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchting R, Yoon JH, Miguel GGS, Green CE, Weaver MF, Vincent JN, Fries GR, Schmitz JM, & Lane SD (2020). Preliminary examination of the orexin system on relapse-related factors in cocaine use disorder. Brain Research, 1731, 146359. 10.1016/j.brainres.2019.146359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussner BD, Smelson DA, Rodrigues S, Kline A, Losonczy M, & Ziedonis D (2006). The validity and reliability of a brief measure of cocaine craving. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 53(3), 233–237. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannous J, Mwangi B, Hasan KM, Narayana PA, Steinberg JL, Walss-Bass C, Gerard Moeller F, Schmitz JM, & Lane SD (2019). Measures of possible allostatic load in comorbid cocaine and alcohol use disorder: Brain white matter integrity, telomere length, and anti-saccade performance. PLoS ONE, 14(1), 1–17. 10.1371/journal.pone.0199729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Team, R. C. (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.r-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Tomie A, Grimes KL, & Pohorecky L. a. (2008). Behavioral characteristics and neurobiological substrates shared by Pavlovian sign-tracking and drug abuse. Brain Research Reviews, 55(1), 121–135. 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunstall BJ, & Kearns DN (2015). Sign-tracking predicts increased choice of cocaine over food in rats. Behavioural Brain Research, 281, 222–228. 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.12.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versace F, Engelmann JM, Deweese MM, Robinson JD, Green CE, Lam CY, Minnix JA, Karam-Hage MA, Wetter DW, Schembre SM, & Cinciripini PM (2017). Beyond Cue Reactivity: Non-Drug-Related Motivationally Relevant Stimuli Are Necessary to Understand Reactivity to Drug-Related Cues. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 19(6), 663–669. 10.1093/NTR/NTX002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versace F, Engelmann JM, Robinson JD, Jackson EF, Green CE, Lam CY, Minnix JA, Karam-hage M, Brown VL, Wetter DW, & Cinciripini PM (2014). Prequit fMRI responses to pleasant cues and cigarette-related cues predict smoking cessation outcome. Nicotine and Tobacco Research, 16(6), 697–708. 10.1093/ntr/ntt214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versace F, Frank DW, Stevens EM, Deweese MM, Guindani M, & Schembre SM (2019). The reality of “food porn”: Larger brain responses to food-related cues than to erotic images predict cue-induced eating. Psychophysiology, 56(4), e13309. 10.1111/psyp.13309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versace F, Kypriotakis G, Basen-Engquist K, & Schembre SM (2016). Heterogeneity in brain reactivity to pleasant and food cues: Evidence of sign-tracking in humans. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 11(4), 604–611. 10.1093/scan/nsv143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versace F, Lam CY, Engelmann JM, Robinson JD, Minnix JA, Brown VL, & Cinciripini PM (2012). Beyond cue reactivity: Blunted brain responses to pleasant stimuli predict long-term smoking abstinence. Addiction Biology, 17(6), 991–1000. 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2011.00372.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versaggi CL, King CP, & Meyer PJ (2016). The tendency to sign-track predicts cue-induced reinstatement during nicotine self-administration, and is enhanced by nicotine but not ethanol. Psychopharmacology. 10.1007/s00213-016-4341-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vujanovic AA, Wardle MC, Bakhshaie J, Smith LJ, Green CE, Lane SD, & Schmitz JM (2018). Distress tolerance: Associations with trauma and substance cue reactivity in low-income, inner-city adults with substance use disorders and posttraumatic stress. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 32(3), 264–276. 10.1037/adb0000362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg A, & Hajcak G (2010). Beyond Good and Evil: The Time-Course of Neural Activity Elicited by Specific Picture Content. Emotion, 10(6), 767–782. 10.1037/a0020242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yager LM, & Robinson TE (2013). A classically conditioned cocaine cue acquires greater control over motivated behavior in rats prone to attribute incentive salience to a food cue. Psychopharmacology, 226(2), 217–228. 10.1007/s00213-012-2890-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon JH, San Miguel GG, Vincent JN, Suchting R, Haliwa I, Weaver MF, Schmitz JM, & Lane SD (2019). Assessing attentional bias and inhibitory control in cannabis use disorder using an eye-tracking paradigm with personalized stimuli. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 27(6), 578–587. 10.1037/pha0000274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Kong F, Hasan ANU, Jackson T, & Chen H (2015). Recognition memory bias in earthquake-exposed survivors: A behavioral and ERP study. Neuropsychobiology, 71(2), 70–75. 10.1159/000369023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.