Abstract

Background

Non‐bismuth quadruple sequential therapy (SEQ) comprising a first induction phase with a dual regimen of amoxicillin and a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) for five days followed by a triple regimen phase with a PPI, clarithromycin and metronidazole for another five days, has been suggested as a new first‐line treatment option to replace the standard triple therapy (STT) comprising a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), clarithromycin and amoxicillin, in which eradication proportions have declined to disappointing levels.

Objectives

To conduct a meta‐analysis of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing the efficacy of a SEQ regimen with STT for the eradication of H. pylori infection, and to compare the incidence of adverse effects associated with both STT and SEQ H. pylori eradication therapies.

Search methods

We conducted bibliographical searches in electronic databases, and handsearched abstracts from Congresses up to April 2015.

Selection criteria

We sought randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing 10‐day SEQ and STT (of at least seven days) for the eradication of H. pylori. Participants were adults and children diagnosed as positive for H. pylori infection and naïve to H. pylori treatment.

Data collection and analysis

We used a pre‐piloted, tabular summary to collect demographic and medical information of included study participants as well as therapeutic data and information related to the diagnosis and confirmatory tests.

We evaluated the difference in intention‐to‐treat eradication between SEQ and STT regimens across studies, and assessed sources of the heterogeneity of this risk difference (RD) using subgroup analyses.

We evaluated the quality of the evidence following Cochrane standards, and summarised it using GRADE methodology.

Main results

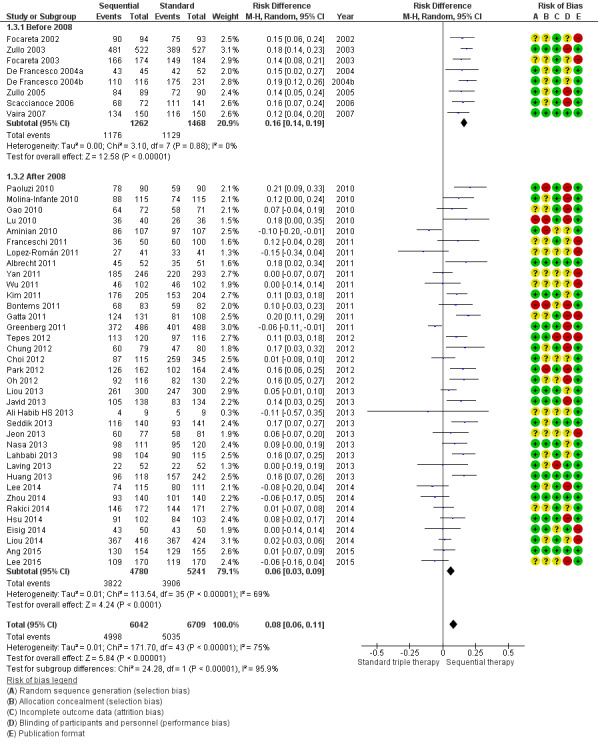

We included 44 RCTs with a total of 12,284 participants (6042 in SEQ and 6242 in STT). The overall analysis showed that SEQ was significantly more effective than STT (82% vs 75% in the intention‐to‐treat analysis; RD 0.09, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.06 to 0.11; P < 0.001, moderate‐quality evidence). Results were highly heterogeneous (I² = 75%), and 20 studies did not demonstrate differences between therapies.

Reporting by geographic region (RD 0.09, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.12; studies = 44; I² = 75%, based on low‐quality evidence) showed that differences between SEQ and STT were greater in Europe (RD 0.16, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.19) when compared to Asia, Africa or South America. European studies also showed a tendency towards better efficacy with SEQ; however, this tendency was reversed in 33% of the Asian studies. Africa reported the closest risk difference (RD 0.14 , 95% 0.07 to 0.22) to Europe among studied regions, but confidence intervals were wider and therefore the quality of the evidence showing SEQ to be superior to STT was reduced for this region.

Based on high‐quality evidence, subgroup analyses showed that SEQ and STT therapies were equivalent when STT lasted for 14 days. Although, overall, the mean eradication proportion with SEQ was over 80%, we noted a tendency towards a lower average effect with this regimen in the more recent studies (2008 and after); weighted linear regression showed that the efficacies of both regimens evolved differently over the years, having a higher reduction in the efficacy of SEQ (‐1.72% yearly) than in STT (‐0.9% yearly). In these more recent studies (2008 and after) we were also unable to detect the superiority of SEQ over STT when STT was given for 10 days.

Based on very low‐quality evidence, subgroup analyses on antibiotic resistance showed that the widest difference in efficacy between SEQ and STT was in the subgroup analysis based on clarithromycin‐resistant participants, in which SEQ reached a 75% average efficacy versus 43% with STT.

Reporting on adverse events (AEs) (RD 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.02; participants = 8103; studies = 27; I² = 26%, based on high‐quality evidence) showed no significant differences between SEQ and STT (20.4% vs 19.5%, respectively) and results were homogeneous.

The quality of the studies was limited due to a lack of systematic reporting of the factors affecting risk of bias. Although randomisation was reported, its methodology (e.g. algorithms, number of blocks) was not specified in several studies. Additionally, the other 'Risk of bias' domains (such as allocation concealment of the sequence randomisation, or blinding during either performance or outcome assessment) were also unreported.

However, subgroup analyses as well as sensitivity analyses or funnel plots indicated that treatment outcomes were not influenced by the quality of the included studies. On the other hand, we rated 'length of STT' and AEs for the main outcome as high‐quality according to GRADE classification; but we downgraded 'publication date' quality to moderate, and 'geographic region' and 'antibiotic resistance' to low‐ and very low‐quality, respectively.

Authors' conclusions

Our meta‐analysis indicates that prior to 2008 SEQ was more effective than STT, especially when STT was given for only seven days. Nevertheless, the apparent advantage of sequential treatment has decreased over time, and more recent studies do not show SEQ to have a higher efficacy versus STT when STT is given for 10 days.

Based on the results of this meta‐analysis, although SEQ offers an advantage when compared with STT, it cannot be presented as a valid alternative, given that neither SEQ nor STT regimens achieved optimal efficacy ( ≥ 90% eradication rate).

Plain language summary

First‐line sequential versus standard triple therapies for Helicobacter pylori eradication

Review question

To estimate the difference in cure rates between both treatments, and to identify factors that may improve or reduce the cure rate for both treatments.

Background

Gastric ulcer and cancer are mainly caused by infection with the bacteria Helicobacter pylori, a harmful micro‐organism able to colonise the human stomach. Published data seem to indicate that this bacteria is present in nearly half of the world's population. The bacterial colonisation leads to a chronic infection that, over time, may alter the stomach's function, tissue structure, and even cell cycle, being able to produce a variety of symptoms and diseases.

Although this micro‐organism may respond to traditional antibiotics, it has a strong resistance to treatment, and in a high percentage of cases can survive most single and double therapies. Different combinations of antibiotics have therefore been used, and the best treatment is still unclear. The most commonly recommended one is the standard triple therapy (STT), containing two antibiotics (clarithromycin, and a nitroimidazole or amoxicillin) and a stomach protector (omeprazole). However, several studies have demonstrated that STT fails in more than one in five people, so investigators proposed replacing it with a non‐bismuth quadruple sequential sequential (SEQ) treatment, containing a first phase with a dual therapy (amoxicillin and omeprazole), followed by a triple‐therapy phase (nitroimidazole, clarithromycin and omeprazole).

Study characteristics

We searched electronic databases and conference abstracts to identify any relevant studies. We include 44 studies, which tested and compared the cure rates of SEQ therapy against STTs. Our review covers research up to April 2015.

Key results

The review indicates that before 2008 the cure rate for SEQ was higher than for STT. However, the cure rate of both treatments is lower than we would wish. The review found that effectiveness depended on several factors, including the geographic region of the study, bacterial resistance, and the date of the study. For example, we found a reduction in the cure rate over time in both STT and SEQ therapies, with a stronger reduction for SEQ. This meant that in the studies published after 2008, SEQ was not more effective than triple therapy when they were both given for 10 days.

The evidence collected and combined in this review does not support the use of SEQ therapy, as its effectiveness can be matched and even improved on by better STTs (given for 10 or 14 days, or high acid inhibition). Results for SEQ were only partially successful. We need to find another form of therapy to provide the best treatment for patients.

Quality of the evidence

The studies included in this review were of mixed quality, but our analyses do not suggest that study quality was influencing cure rates.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Is 10‐day SEQ efficacy superior to STT?

| Is 10‐day SEQ efficacy superior to STT? | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with Helicobacter pylori infection Settings: participants naïve to eradication treatment Intervention: 10‐day sequential regimen Comparison: standard triple therapy | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Standard triple therapy | 10‐day sequential regimen | |||||

| Eradication proportion | Study population | RD 0.09, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.11 | 12,701 (44 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1,2,4 | Results were highly heterogeneous (I² = 75%), and 20 studies did not demonstrate differences between therapies | |

| 751 per 1000 | 833 per 1000 (811 to 863) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 750 per 1000 | 832 per 1000 (810 to 862) | |||||

| Geographic region | Study population | RD 0.09, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.12 | 12284 (44 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3 | The Latin American subgroup showed no consistent results with the remaining subgroups and there was a tendency to better efficacy with STT than with SEQ in all three included studies although two did not demonstrate differences between therapies | |

| 749 per 1000 | 839 per 1000 (809 to 869) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 749 per 1000 | 839 per 1000 (809 to 869) | |||||

| Publication date | Study population | RD 0.08, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.11 | 12751 (44 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1,2,4,5 | Results were more heterogeneous (69%) in the "after 2008" subgroup | |

| 750 per 1000 | 833 per 1000 (811 to 863) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 750 per 1000 | 832 per 1000 (810 to 862) | |||||

| STT length | 7 days | RD 0.14, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.17 | 5439 (22 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high1 | Six out of 22 studies did not demonstrate differences when 7 days STT was compared to 10 days SEQ. Results for this comparison were consistent (I² = 38%) | |

| Study population | ||||||

| 725 per 1000 | 870 per 1000 (848 to 892) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 720 per 1000 | 864 per 1000 (842 to 886) | |||||

| 10 days | RD 0.06, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.10 | 3967 (19 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high1,2 | In this subgroup 10 days SEQ was better than 10 days STT however heterogeneity between studies was greater (I² = 62%) than in the 7 days STT subgroup analysis. One study out of 19 demonstrated 10 days STT was superior to 10 days SEQ. Eleven studies could not demonstrate differences between therapies | ||

| Study population | ||||||

| 732 per 1000 |

791 per 1000 (754 to 835) |

|||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 722 per 1000 |

780 per 1000 (744 to 823) |

|||||

| 14 days | RD 0.02, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.06 | 3831 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high1,2 | 14 days STT did not demonstrate differences with 10 days SEQ | ||

| Study population | ||||||

| 803 per 1000 | 811 per 1000 (795 to 827) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 811 per 1000 | 819 per 1000 (803 to 835) | |||||

| Bacterial antibiotic resistance | Study population | RD 0.13, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.24 | 832 (8 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2,4,5,6,7,8 | SEQ was superior to STT in those patients with primary clarithromycin resistant strains only | |

| 672 per 1000 | 807 per 1000 (699 to 914) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 550 per 1000 | 660 per 1000 (572 to 748) | |||||

| Adverse events rate | Study population | RD 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.02 | 8103 (27 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ high5,9 | No differences were reported between treatment arms | |

| 195 per 1000 | 199 per 1000 (176 to 215) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 187 per 1000 | 191 per 1000 (168 to 206) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RD: Risk difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Different STT lengths (different total doses) modify RDs. 2There is moderate to substantial unexplained heterogeneity. 3Small number of studies and wider confidence intervals in the South American subgroup. 4Confidence intervals overlap. 5Wide confidence intervals in some subgroups. 6Lack of reporting in most of the studies. 7Small number of studies in some subgroups. 8Metronidazole resistance is dose‐dependent. 9Longer treatments (higher total dose) led to higher rates of AEs.

Background

Description of the condition

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infects over 50% of the adult population globally (De Martel 2006) and is known to be associated with a wide range of upper gastrointestinal diseases including gastritis, peptic ulcer disease (PUD) and gastric cancer. The latest Maastricht IV Consensus (Malfertheiner 2012) has strongly recommended H. pylori eradication for people with PUD, mucosa‐associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), lymphoma and atrophic gastritis, post‐gastric cancer resection, in people who are first‐degree relatives of people with gastric cancer and in people with a preference to treat a known H pylori infection after consultation with physicians. It is also suggested thatH. pylori eradication is appropriate for people infected with H pylori, investigated for non‐ulcer dyspepsia (NUD). Treatment of H. pylori may also prevent PUD, bleeding or both in naïve users of non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (Malfertheiner 2012). The treatment for H. pylori infection is therefore intended to eradicate the bacteria to stop progression of gastric lesions (atrophy, ulcers and cancer), and not to resolve dyspeptic symptoms, as in most cases those will remain after treatment.

Description of the intervention

Since 1997, a worldwide panel of experts, the European Helicobacter Study Group (EHSG) has recommended in its consensus conferences a triple therapy comprising a proton‐pump inhibitor (PPI) plus two antibiotics used twice daily as the first‐line H. pylori eradication regimen (Malfertheiner 1997; Malfertheiner 2002; Malfertheiner 2007; Malfertheiner 2012). Commonly, clarithromycin is used together with amoxicillin or nitroimidazole (metronidazole or tinidazole) (Gisbert 2007; Malfertheiner 2007). However, sequential therapy (SEQ), based on a PPI plus amoxicillin twice daily for the first five days followed by PPI plus clarithromycin together with nitroimidazole twice daily for the following five days, has been suggested as an alternative treatment to replace the standard triple therapy (STT) (De Francesco 2001; Zullo 2000). PPIs are used to protect the lining of the stomach against ulcerogenic effects and have a bactericidal action (McNicholl 2012).

Additionally, in this context of short‐term drug regimens (two weeks or less) where the main objective is to eradicate the bacteria, the benefits or harms of treatments and patients' satisfaction is somewhat limited.

How the intervention might work

The efficacy of STT is inversely related to the bacterial load, and higher eradication proportions are achieved in those with a low bacterial density in the stomach (Lai 2004; Perri 1998). It has therefore been suggested that the short initial dual therapy used in SEQ treatment with amoxicillin lowers the bacterial load in the stomach in order to improve the efficacy of the immediately subsequent short course of triple therapy (Moshkowitz 1995; Zullo 2007). In other words, it acts as an induction phase that may amplify the efficacy. The first five days of amoxicillin and PPI thus result in a marked reduction of H. pylori and even eradication in at least 50% of people (Marshall 2008; Moshkowitz 1995). The second stage of the regimen (clarithromycin and a nitroimidazole) would act to eradicate a rather small residual population of viable organisms (Marshall 2008).

Moreover, it has been suggested that the initial use of amoxicillin may offer another essential advantage in the eradication of H. pylori (Zullo 2007). It has been found that regimens containing amoxicillin prevent the selection of secondary clarithromycin resistance (Murakami 2002). The most accepted candidate theory suggests that SEQ might therefore improve eradication proportions as the initial phase of treatment with amoxicillin weakens bacterial cell walls, preventing the development of drug efflux channels involved in the reduction of clarithromycin and other drug concentrations inside the bacteria, although this has not yet been demonstrated. This may allow higher concentrations of antibiotics in the cytoplasm during the second phase of treatment that would facilitate the binding of clarithromycin to the ribosomes.

The sequential administration of antibiotics is not generally recommended because of concerns about promoting drug resistance (Graham 2007a). However, the dual therapy of SEQ uses a drug (amoxicillin) that rarely results in resistance, such that the outcomes should be either cure of the infection or a marked reduction in bacterial load, making the presence of a pre‐existing small population of resistant organisms less likely (Graham 2007b).

Why it is important to do this review

Standard triple therapy is the most commonly used treatment in clinical practice. However, a critical fall in the H. pylori eradication proportion following this therapy has been observed since the discovery of H. pylori. From 2007, STT eradication rates were below 80%, an efficacy which was defined as disappointing for any antimicrobial infection (Graham 2007a). Two double‐blind, US multicentre studies both found disappointingly low eradication proportions with STT (77%) (Laine 2000; Vakil 2004). Two meta‐analyses including more than 53,000 participants have shown that the cure proportion is below 80% (Janssen 2001; Laheij 1999). Also, a prospective study (Mégraud 2013), conducted in the European framework to assess H. pylori resistance to antibiotics and its relationship to antibiotic consumption, showed that because of the high clarithromycin resistance, empirical STT should not be used. Therefore, the ethics of continued use of STT have recently been questioned and the use of alternative therapy has been recommended in its place (Graham 2007c).

The SEQ regimen is an alternative therapeutic approach, but eradication efficacy must be confirmed now that the resistance proportion for clarithromycin has increased (Moayyedi 2007). Almost all studies using the SEQ regimen published during 2008, 2009 and 2010 had lower than 90% eradication proportions and in some cases rates of 80% or less have been reported (Park 2009). Moreover, the most commonly used SEQ therapy uses tinidazole, whilst in some studies metronidazole has been used. A recent review of SEQ therapy (Vaira 2009) showed that the eradication proportion achieved with metronidazole‐based regimens was significantly lower than that achieved with a tinidazole‐based regimen. Indeed, tinidazole has a markedly longer half‐life compared to metronidazole and this could be a cause for concern for successful H. pylori therapy. It is also important to mention that most of the studies considered in the previous pooled analyses and meta‐analyses were performed in Italy (Jafri 2008; Tong 2009; Vaira 2009). Some of the more recent studies, including other regions, have not demonstrated a beneficial effect of SEQ therapy when compared with STT but have instead shown equivalent eradication proportions (Gatta 2009; Gisbert 2010).

Previous meta‐analyses have compared STT with SEQ therapy (Gatta 2009; Jafri 2008; Tong 2009). In our preliminary search, we identified several randomised controlled trials (RCTs) which were not included in the previous meta‐analyses. We have therefore conducted a systematic review of RCTs comparing SEQ therapy versus STT for H. pylori eradication, using more databases, optimised search strategies and applying the rigorous techniques recommended by Cochrane. This systematic review was developed from a Cochrane review of all H. pylori eradication therapies (Forman 2000).

Objectives

Primary objective

To conduct a meta‐analysis of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing the efficacy of a SEQ regimen with STT for the eradication of H. pylori infection.

Secondary objective

To compare the incidence of adverse effects associated with both STT and SEQ H. pylori eradication therapies.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Only parallel‐group, randomised controlled trials were eligible for inclusion in the review. We included only those trials comparing a 10‐day SEQ versus a STT for H. pylori eradication, as defined in the headings below. We excluded studies that were not assessing an H. pylori treatment or that focused on other gastrointestinal conditions. We excluded non‐randomised studies, case reports, letters, editorials, commentaries and reviews. Abstracts and full‐text forms were eligible for inclusion. There were no restrictions by date of publication or by language.

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria

Randomised trials were eligible for inclusion if the study population included adults or children diagnosed as positive for H. pylori (with at least one confirmatory test) on the basis of monoclonal stool antigen test, rapid urease test (RUT), histology or culture of an endoscopic biopsy sample, or by urea breath test (UBT). Study participants had to be naïve to H. pylori eradication treatment.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded trials in which participants were diagnosed as H. pylori‐positive solely on the basis of serology or polymerase chain reaction (PCR), or who had previously been treated with an eradication therapy. Study participants could not present with serious comorbidities such as HIV infection, malignancy, etc.

Types of interventions

Sequential therapy

The 10‐day SEQ comprised a PPI and amoxicillin 1 g twice daily, all taken orally for the first five days, followed by PPI twice daily, clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily and a nitroimidazole (tinidazole or metronidazole at either 400 mg or 500 mg) twice daily, all taken orally for the following five days.

We included only trials assessing SEQ therapies lasting 10 days. Studies were subject to exclusion if there were any variations in the intervention schedule regarding the length of the SEQ treatment.

Standard triple therapy

The STT consisted of a PPI, clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily and amoxicillin 1 g twice daily, all taken orally and lasting at least seven days.

Types of outcome measures

We included all relevant trials, even if they did not report evidence of eradication of H. pylori as their primary outcome.

Primary outcomes

We considered reported efficacy, defined as the eradication/cure proportion/rate, to be the primary outcome.

Trials were included if they reported the number of participants with H. pylori eradication. If percentages were reported rather than numbers, then we derived the proportion of participants cured from the intention‐to‐treat (ITT) randomised sample size for each treatment arm.

Trials were eligible if H. pylori eradication was confirmed using RUT or histology of an endoscopic biopsy sample, or by a UBT or a monoclonal stool antigen test, at least four weeks after completion of treatment.

We excluded trials in which assessments were by serology test alone or by culture alone.

Secondary outcomes

Reported incidence of adverse events (AEs) was also included.

AEs incidence was recorded as the number of participants reporting: any type of AE; any gastrointestinal disturbance such as nausea or vomiting; any dermatological problem; any systemic effect (fever, headache or dizziness); or any serious AE.

We defined a serious AE as the occurrence of any undesirable and important medical event, such as, for example, death, a life‐threatening situation, hospitalisation, permanent damage associated with any medical drug. We distinguish between a serious AE and a severe AE, i.e. an intense form of AE that usually incapacitates an individual's normal life. Reported severe AEs were also collected.

We define treatment compliance (or adherence) as the extent to which a participant fulfilled the requirements of the prescribed treatment in terms of drug type, dosage and length of treatment.

We collected the reported proportion of participant withdrawals, defined as the number of participants discontinuing treatment due to AEs.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We conducted bibliographical searches in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) through the Cochrane Library (Appendix 1), MEDLINE (Appendix 2), EMBASE (Appendix 3) and CINAHL (Appendix 4) electronic databases.

We combined search terms to capture two components of the study question: the disease (H. pylori infection) and the intervention of interest (the comparison of STT versus SEQ therapy). We used the following combination of terms (all fields): (Helicobacter OR pylori) AND sequential AND (triple OR “standard regimen” OR “standard therapy”). We adapted and conducted handsearches using the same syntax.

The design of the search was refined by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator at the Cochrane Upper Gastrointestinal and Pancreatic Diseases Review Group.

We ran the electronic search up to April 2015.

Searching other resources

We performed additional handsearches of websites in order to retrieve additional publications not captured by the electronic searches. The manual search aimed to identify abstracts of RCTs that might not have been published in peer‐reviewed journals but only as part of conference proceedings, specialised journals or international congresses such as the International Workshop of the European Helicobacter Study Group (EHSG), the American Digestive Disease Week (DDW) and the United European Gastroenterology Week (UEGW).

We reviewed each of the abstracts identified as potentially eligible and included only those meeting the inclusion criteria.

We conducted detailed cross‐referencing from the bibliographies of the included studies as well as from other systematic reviews, in order to identify further relevant trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Prior to the selection of studies phase, most duplicates were automatically removed when studies were imported to the citation manager. We removed the remaining duplicates manually during the first screening phase.

We conducted the selection of retrieved studies from the searches in two phases. We undertook an initial screening of titles and abstracts (first screening phase) against the inclusion criteria, to identify potentially relevant publications. Following this step, we checked of the full papers (second screening phase) of the studies identified as potentially eligible for inclusion during the first screening phase.

In the case of abstracts or articles with insufficient detail to meet the inclusion criteria, we contacted the authors.

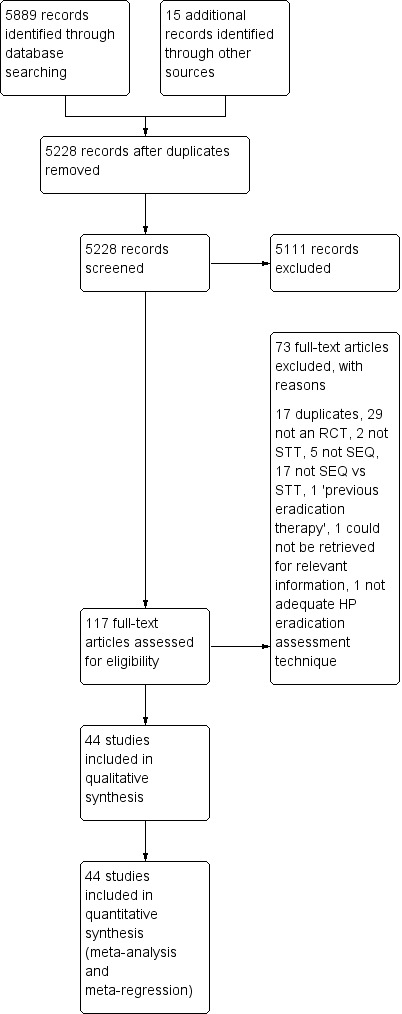

Based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) approach (www.prisma‐statement.org), we developed a diagram to schematise the steps used for the identification and selection of studies. We specified the number of studies considered at each step and the reason for exclusion of each of the excluded studies.

Two review authors (OPN and AGM) carried out both the first and second screenings independently, resolving any discrepancies by discussion and consulting a third review author (JPG) for unresolved disagreements.

Data extraction and management

During the protocol phase we developed a pre‐tested data extraction form to record data from the selected papers. We collected the following fields during the data extraction process:

first author’s name and year of publication;

country;

format of publication (abstract versus journal article);

age of the population (adult versus children);

medical condition (PUD or NUD or other);

number of participants in each treatment group;

name, dose and timing of antibiotic administration;

length of STT;

eradication proportion per treatment regimen (ITT and per‐protocol (PP)): if only the PP sample was reported, we calculated the ITT sample on the basis of the randomisation and dropout information;

definition of compliance and the level of compliance in the ITT sample;

details of the method of assessment of H. pylori infection both before and after treatment;

whether the antibiotic sensitivity and resistance were tested before and after eradication; if so, the primary and secondary antibiotic resistance;

incidence, type and severity of AEs;

study quality: generation of the treatment allocation, concealment of the treatment allocation at randomisation, implementation of masking, completeness of follow‐up and use of ITT analysis.

We contacted study authors for any missing data.

Two review authors (OPN and AGM) carried out data extraction independently, resolving any discrepancies by discussion and consulting a third review author (JPG) for unresolved disagreements.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed four components of quality following the quality checklist recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews and Interventions (Higgins 2011). We assessed the quality according to the information available in the published trials, mindful of the risk of overestimating intervention effects in RCTs with inadequate methodological quality (Kjaergard 2001). We contacted authors for any missing information. Items assessed are described and listed in the headings below.

Two review authors (OPN and AGM) independently assessed the methodological quality of all the included studies. As in previous phases, we sought the opinion of a third review author (JPG) in case of disagreement.

Generation of the treatment allocation

We considered a study to be a RCT if it was explicitly described as ‘randomised’. This should include the use of words such as ‘randomly’, ‘random’ or ‘randomisation’. We then rated the randomised trial as truly random, pseudo‐random, non‐random, not stated, or unclear.

We defined a trial as ‘truly random’ if the allocation sequence was computer‐generated or generated by a random‐number table, coin toss, shuffles or throwing dice. The person involved in the recruitment of participants should not be the one performing the procedure.

If the selection was based on patient hospital numbers, birth dates, visit dates, alternate allocation or other method not involving a defined random mechanism but likely to produce an unpredictable sequence of numbers, we considered the trial to be ‘pseudo random’.

We excluded studies in which the selection was based on participant or clinical preference, or any selection mechanism that could not be described as random. We also excluded studies that did not state whether the treatment was randomly allocated.

We classified studies which were identified as randomised trials, but which did not describe how the treatment allocation was generated, as having an 'unclear' generation of treatment allocation.

Concealment of the treatment allocation at randomisation

A study was classified as concealed, unconcealed or unclear in the following situations (Haynes 2006):

We rated a study ‘concealed’ if the trial investigators were unaware of the allocation of each participant before they were entered into the trial. Adequate methods included central telephone randomisation schemes, pharmacy‐based schemes, sequentially‐numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes, sealed envelopes from a closed bag, or the use of numbered or coded bottles or containers.

We rated the allocation as ‘unconcealed’ when trial investigators were aware of the allocation of each participant before they entered the trial. For example, when it was based on participant data, such as the date of birth or hospital case‐note number, visit dates, sealed envelopes that were not opaque, or a random‐number table that was not concealed from the investigator.

If authors did not report or provide a description of an allocation concealment approach that allowed for classification as concealed or not concealed, then we categorised the study as ‘unclear allocation concealment’.

Implementation of masking

A trial could be considered double‐blinded, single‐blinded, not blinded or unclear, and was to be classified within a 'Risk of bias' table into one of three categories: low risk, unclear risk and high risk (Higgins 2011).

We judged a study as ‘not blinded’ if the authors defined it as an open‐label study, and we rated it at ‘high risk’. We classified studies as ‘unclear risk’ if no blinding information was reported.

If a trial was simply described as 'single‐blind', we recorded the degree of masking as ‘unclear’ for clinician and outcome assessor, while participants were presumed to be blinded.

If a trial was reported as ‘double‐blind’, it had to be rated as ‘low risk’. Double‐blinding, however, was unlikely, as the type of treatment administration could not easily allow the simultaneous blinding of the clinician, the outcome assessor, the participant and the pharmacist.

Completeness of follow‐up and use of intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis

We noted the proportion of participants for which there were missing outcome data and/or who were excluded from the analysis for each arm of the trial. For the ITT analyses we assumed that these participants had failed therapy. We stated whether the analysis included all randomised participants, i.e. whether an ITT approach was undertaken.

We recorded the authors’ definitions when they reported an ITT analysis. Due to the varied definitions of ITT used by authors, we favoured the most widely‐accepted definition of the ITT approach. All participants were to be analysed in the groups to which they were originally randomly assigned, regardless of whether they satisfied the entry criteria, which treatment they received, or subsequent withdrawal or deviation from the protocol (Hollis 1999).

We reported all available information for all randomised participants. We included studies reporting either ITT or PP analysis alone. We contacted authors of those studies either using a different ITT approach from the one used in this review, or reporting only a PP analysis, in order to obtain our preferred ITT analysis approach.

We included in our ITT meta‐analysis studies reporting an ITT analysis, but requiring participants to have the second test confirming their H. pylori infection status after randomisation in order to be included in the analysis.

These four quality components are part of the key methodological features that are important to the validity and interpretation of included trials as mentioned above (Moyer 2005). We did not score the quality of the studies, and did not exclude studies classified as ‘low quality’. We used the individual quality assessment items to explore heterogeneity. If we found significant heterogeneity between studies (details below), we explored it by using subgroup analysis with pooled effect‐size estimates, and discuss them when interpreting the results.

Measures of treatment effect

Given that the outcome was common, that is that 'H pylori eradication' was usually expected after treatment, and that the treatment and follow‐up themselves were fixed for each arm, the odds ratio (OR), would produce a biased effect estimate. We therefore expressed dichotomous outcomes of individual studies using the risk difference (RD) together with the 95% confidence interval (CI), taking 'H. pylori eradication' as the primary outcome. The RD describes the difference in the risk of observing an event in the SEQ treatment group versus the STT comparison group, for which a value of 0 indicates that the estimated effects are the same for both interventions. In the clinical context, generally the terms "odds" and "risks" are interchangeable, however; the term "risk" suits better our medical question as it defines the probability of an event will occur as opposite to the term "odd" which enhances the idea of the ratio of the probability that a particular event will occur to the probability that it will not occur (Higgins 2011).

We have treated the SEQ arm as the intervention group and the STT arm as the control group.

Unit of analysis issues

We included only standard design, parallel, randomised controlled trials. Our interest was only in the direct comparison between the two treatment regimens (10‐day SEQ and 7‐ to 14‐day STT). We did not include multiple groups in a single pair‐wise comparison, so that the same participant was not used twice in the same analysis.

However, multiple‐group comparisons are usual across treatment arms in clinical trials. For instance, the ITT population could be randomised into three different treatment arms (or schedules): STT lasting 7 days, STT lasting 14 days and SEQ therapy lasting 10 days. In such cases, for the purpose of the overall analysis, we combined the different arms of the same treatment (i.e. 7‐day STT and 14‐day STT) by summarising the number of participants in each arm. Afterwards, we undertook the corresponding subgroup meta‐analyses using the separate arms for STT treatment duration.

We assessed the different treatment schedules within the same treatment arm through standard single pair‐wise comparisons, as specified under the subgroup analyses section.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted authors for any incomplete outcome data from included studies. We considered those participants for whom outcome data were still missing (due to dropout or incomplete records) to have failed eradication for the primary outcome.

Assessment of heterogeneity

In order to identify the possible diversity in trial characteristics, we analysed the clinical, methodological and statistical components.

We performed the Chi² test for heterogeneity for each combined analysis, where P < 0.10 indicated significant heterogeneity between studies (Higgins 2002). The I² statistic was reported, which quantifies heterogeneity by calculating the percentage of total variation across studies that is due to heterogeneity (an approach that has been endorsed by Cochrane). We define significant heterogeneity as I² > 25%, based on the judgement that I² values below 25%, 50% and 75% represent low, moderate and high heterogeneity, respectively (Higgins 2003).

We used graphical methods (forest plots) to complete the Chi² test assessment. When we identified heterogeneity, we investigated the source using additional techniques, such as subgroup analyses or funnel plots, to work out whether particular characteristics of studies were related to the sizes of the treatment effect, in accord with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Intervention (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

To assess publication bias, we checked for funnel plot asymmetry by examining the relationship between the treatment effects and the standard error of the estimate.

We produced funnel plots for the principal outcome for each comparison (plots of risk difference (RD) against the standard error (log of RD)).

Data synthesis

In order to collate, combine and summarise the information from the included studies, we decided to undertake a quantitative (meta‐analytic) approach. If there were insufficient trials (two or fewer) reporting for the same comparison, then we would conduct a qualitative evaluation (narrative).

As the first step for the data synthesis, we present an initial overview of results referring generally to all included studies. We give these overall findings in a descriptive fashion, in terms of geographic region, target populations, sample sizes, age of the population, medical condition at baseline and treatment schedules assessed (Description of studies).

The second step in the evidence synthesis consisted of summarising the information related to the size of the effect for all studies, as well as for each different participant group, comparison or outcome measure undertaken. We also report results from subgroup analyses as well as sensitivity analyses.

We performed meta‐analysis combining the RDs for the individual studies in a global RD using a random‐effect method for dichotomous outcomes (Mantel‐Haenszel). Additional sensitivity analyses were performed to check the robustness of the results (DerSimonian 1986; Egger 1997). We conducted pooled analyses using Review Manager 5.3 software (RevMan 2014).

We performed subgroup analyses to identify sources of heterogeneity and report summary estimate of the RD within subgroups of these identified sources.

There are several methods to calculate the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) and some have limitations (Altman 2002; Cates 2002; Moore 2002). Many published meta‐analyses do not provide the results or the methods used. In this review, we calculated the NNTB for efficacy and the number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) for adverse events, by using the formula NNT = 1/ |RD| (Higgins 2011), where |RD| stands for the absolute value of the risk difference. The NNTB was always reported among those statistically significant comparisons.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We performed pre‐planned subgroup analyses, regardless of whether significant heterogeneity was present:

geographic region;

publication date;

age (children versus adults);

length of STT (7 versus 10 versus 14 days);

type of nitroimidazole (metronidazole versus tinidazole);

resistance of each antibiotic;

dosing for PPI (SEQ therapy versus STT);

type of disease at enrolment (PUD versus NUD).

Quality of the body of evidence (GRADE methodology)

We assessed the quality of the body of the evidence using GRADE methodology in those subgroup analyses where we found statistically significant differences between treatments for the main outcome. We have incorporated these outcomes into the 'Table 1 (SoF) for the SEQ versus STT comparison. We present GRADE quality assessments ranging from 'very low' to 'high' quality evidence alongside the effect estimates, and decisions made relating to downgrading (or upgrading) of evidence.

The GRADE approach uses five considerations: study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias to assess the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome. The evidence was downgraded from 'high quality' by one level for serious (or by two levels for very serious) limitations, depending on assessments of risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, serious inconsistency, imprecision of effect estimates or potential publication bias.

Sensitivity analysis

No arbitrary inclusion or exclusion criteria were established for the search strategy. If during the review process we identified sensitivity issues (missing data, individual peculiarities of the studies), we repeated the meta‐analysis to test for differences. We conducted sensitivity analyses to test the robustness of the review: using a random‐effects model instead of a fixed‐effect model; excluding trials with no or unclear allocation concealment; excluding trials where the method of randomisation was unclear; or excluding trials where masking was unclear.

Results

Description of studies

We retrieved 5889 citations from the following electronic databases: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE, and CINAHL; we found 15 additional references through handsearches and from the International Workshop of the European Helicobacter Study Group, the American Digestive Disease Week (DDW) and the United European Gastroenterology Week (UEGW) Congresses, up to April 2015.

After removal of duplicates, we initially screened 5228 citations resulting from the electronic searches. Based on consideration of their titles and abstracts we excluded 5111 citations, while 117 papers were targeted for full‐article review, either because they were potentially relevant, or because not enough information was reported in the title and abstract to make a final decision regarding the inclusion of the paper in the review.

After review of the full papers, we finally included 44 publications in the review. All of them were randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

A description of the process followed for the identification and selection of studies, and the number of studies identified through each step, is presented as part of the PRISMA diagram (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Results of the search

We include 44 RCTs with a standard parallel‐group design. See the Characteristics of included studies for full details.

The primary objective of almost all the included studies was very similar, and aimed to assess the efficacy of the 10‐day SEQ therapy versus STT.

Two references reported different primary objectives: De Francesco 2004b aimed to identify predictive factors for the outcome of H. pylori eradication using two therapeutic schemes (STT and SEQ), and Molina‐Infante 2010, whose primary objective was to compare clarithromycin and levofloxacin in triple and SEQ first‐line regimens.

None of the included studies reported efficacy in groups of participants with another concomitant health condition.

For the purposes of the evidence synthesis, we categorised the included studies according to the relevant endpoint assessed, i.e. the overall eradication proportion with SEQ and STT, as well as the different variables evaluated within the subgroup analysis.

Included studies

Of the included studies, 11 were published in Italy (De Francesco 2004a; De Francesco 2004b; Focareta 2002; Focareta 2003; Franceschi 2011; Gatta 2011; Paoluzi 2010; Scaccianoce 2006; Vaira 2007; Zullo 2003; Zullo 2005), eight in Korea (Choi 2012; Chung 2012; Jeon 2013; Kim 2011; Lee 2014; Lee 2015; Oh 2012; Park 2012), eight in China (Gao 2010; Huang 2013; Liou 2013; Liou 2014; Lu 2010; Wu 2011; Yan 2011; Zhou 2014), two in India (Javid 2013; Nasa 2013), two in Morocco (Lahbabi 2013; Seddik 2013), one each in Iran (Aminian 2010), Spain (Molina‐Infante 2010), Latin‐America (Greenberg 2011), Poland (Albrecht 2011), Puerto‐Rico (Lopez‐Román 2011), Belgium (Bontems 2011), Slovenia (Tepes 2012), Kenya (Laving 2013), Saudi Arabia (Ali Habib HS 2013), Brazil (Eisig 2014), Japan (Hsu 2014), Turkey (Rakici 2014) and Singapore (Ang 2015). Eight of the included studies were published before 2008.

Six studies (Albrecht 2011; Ali Habib HS 2013; Bontems 2011; Huang 2013; Laving 2013; Lu 2010) published between 2010 and 2013 assessed the efficacy of 10‐day SEQ versus STT in children.

Twelve studies (Aminian 2010; Chung 2012; De Francesco 2004a; Greenberg 2011; Javid 2013; Kim 2011; Liou 2013; Molina‐Infante 2010; Scaccianoce 2006; Zhou 2014; Zullo 2003; Zullo 2005) assessed the efficacy of SEQ versus STT in either or both NUD and PUD participant groups. Eradication was reported for each of the groups independently, and the studies were pooled within the corresponding subgroup analysis.

The sample sizes across the included studies varied considerably, ranging from nine participants within both the STT and SEQ arms in Ali Habib HS 2013 to 522 participants within the SEQ arm and 527 participants in the STT arm in Zullo 2003.

Based on the eligibility criteria, all studies compared 10‐day SEQ versus STT. STT included different regimen lengths (7, 10 and 14 days) and different antibiotic doses (high and standard doses). The SEQ utilised different nitroimidazole types (metronidazole and tinidazole), and both regimens varied the type and dosage of PPIs: omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole, or esomeprazole. One study (Gatta 2011) used double‐dose PPI and another (Chung 2012) low‐dose PPI in both treatment arms.

H. pylori eradication proportion with SEQ therapy ranged from 42% in Laving 2013 to 96% in the Italian study Focareta 2002.

Excluded studies

The total number of studies excluded after the first screening was 5111. We then excluded 73 studies during the full‐text review. See Characteristics of excluded studies tables for further details. One study was selected for potential inclusion, but although we contacted the authors in order to retrieve relevant information, we finally excluded it due to ineligibility.

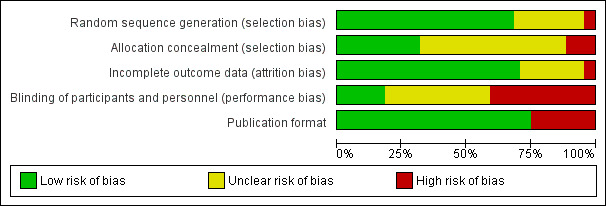

Risk of bias in included studies

In the overall comparison 'Eradication proportion of SEQ versus STT', five studies (Albrecht 2011; Ang 2015; Huang 2013; Vaira 2007; Zhou 2014) were categorised as ‘low risk of bias’ in all four domains of the checklist assessing the quality of the methodology (Figure 2).

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Bontems 2011; Lu 2010 were categorised as ‘high risk’ in the items relating to randomisation, allocation and blinding. Three other studies (Aminian 2010; Paoluzi 2010; Park 2012) were likewise rated as having poor allocation concealment and blinding, with both items flagged as 'high risk', or at least one of them (Chung 2012; Gao 2010; Gatta 2011; Lee 2015; Zullo 2005).

A lack of comprehensive reporting of outcomes, as well as scarcity of information related to the assessed quality items within the aforementioned studies, made both selection and performance biases a threat to the validity of the review (Figure 2 and Figure 3).

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

However, regardless of the potential biases, the subgroup analyses confirmed a significant gain in the overall ITT eradication proportion with 10‐day SEQ compared to STT. Most of the studies (72%) were reported to be ‘truly randomised’ (as defined in Assessment of risk of bias in included studies) and therefore were unlikely to have been subject to selection bias due to a lack of randomisation through sequence generation.

Performance bias due to lack of blinding of study participants and personnel was, a priori, the domain that was more likely to influence the review’s findings, since over 50% of studies were flagged as being at ‘high risk’. However, the importance of this finding in the context of H. pylori eradication is low, as addressed in the Discussion.

Allocation

In five (12%) studies (Aminian 2010; Bontems 2011; Lu 2010; Paoluzi 2010; Park 2012) the method of allocation was not concealed. Ten (23%) studies reported that allocation was concealed and the remaining ones did not report any information on allocation of the sequence generation, and were therefore flagged as unclear (Figure 2).

In order to generate an unpredictable and unbiased sequence, 10 (23%) studies reported ‘adequate’ concealment of the allocation sequence, mainly using opaque sealed envelopes and by involving personnel in the enrolment phase that were unaware of upcoming assignment of participants to treatments.

Albrecht 2011 reported that the intervention sets were prepared by the hospital’s pharmacy and by independent personnel not involved in the study. Similarly, in Kim 2011 only the independent staff could manage a matching list between study identification number and hospital number, and the data were only revealed to other investigators once recruitment and data collection were completed.

Blinding

We judged 17 (38%) studies to be at ‘high risk’, as authors reported either that the trial was not blinded or the design of the study was open‐label. Similarly, 18 studies, rated as ‘unclear risk’, either did not report any information regarding masking, or authors stated that only the investigators (but not the participants), were blinded to the treatment allocation, in which case we categorised the studies as single‐blinded (Figure 2).

We rated Albrecht 2011 and Vaira 2007 as ‘low risk’, given that the authors stated that a ‘double‐blind’ design was used with placebo during three days after completion of STT. With only two studies reported as double‐blinded, we could not conduct the planned subgroup meta‐analysis indicated in the protocol. The eradication proportions were 89% and 86% in the SEQ therapy arms and 77% and 69% in the STT therapy arms in Vaira 2007 and Albrecht 2011 respectively.

It should nonetheless be noted that the number of studies that were not blinded was due to the design of the SEQ regimen, where usually two drugs were used in the initial phase and three drugs during the second phase of treatment (as per protocol). Due to the manner in which the drugs were administered, participants could not be easily blinded to their assigned treatment.

Incomplete outcome data

Primary outcomes were correctly and consistently reported in the majority (75%) of the studies (Figure 3). Attrition bias was reported in three of the nine studies in abstract form (Eisig 2014; Lopez‐Román 2011; Wu 2011), accounting for around 386 participants, which represented 3% of the total randomised population in our meta‐analysis.

Indeed, information related to the medical condition at baseline, sex ratio, average age of the population, per protocol sample size, incidence of AEs or antibiotic resistance were scarcely described in the reports of abstracts of Congresses.

One study (Laving 2013) was rated at 'high risk' for the reporting of outcomes, as data regarding eradication were reported as the number of participants eradicated separately by stool antigen negative and histology negative. Also authors did not provide eradication proportions by ITT analysis.

We noted no differences in the number of excluded participants or dropouts between arms across the included studies.

Selective reporting

Eight (18%) studies reported H. pylori eradication proportions for those people with bacterial antibiotic resistance: four studies in people with clarithromycin bacterial resistance; seven studies in people with nitroimidazole bacterial resistance and six studies in people with both bacterial resistances. Five of these six studies reported the different cut‐off points for isolates assessed for nitroimidazole, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin; where minimal inhibitory concentrations to consider resistance were reported as ≥ 8 µg/mL for metronidazole, ≥ 1 µg/mL for clarithromycin and between 0.5 and 1 µg/mL for amoxicillin. The remaining study was an abstract and the information was not available and could not be retrieved from the authors.

Bias associated with selective reporting of this outcome measure therefore seemed likely.

Other potential sources of bias

Thirty‐five (81%) studies were in complete article form, indicating no bias due to publication status.

Studies were of mixed quality. Eradication was evaluated in subgroup analyses and the evidence was further assessed using GRADE. We include those subgroups in which eradication was found to be significantly different among groups or where subgroups were thought to influence H. pylori treatment efficacy in Table 1. We downgraded the quality of the RCT evidence for the following outcomes: publication date (moderate quality), geographic region (low quality) and antibiotic resistance (very low quality). The analyses based on STT length and the adverse event rate were rated as high quality.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Overall H. pylori eradication

We include 44 studies in the overall analysis comparing SEQ versus STT.

Note that for the overall analysis, when combining data and only within the STT arm, several studies randomised participants into up to three different STT arms (7, 10 and 14 days). In order to preserve randomisation and weight among included studies, we present the final overall proportion of people cured with STT as a single figure, by adding the number of people cured in each of the three STT arms (as stated in the section Unit of analysis issues). The total of events (total STT eradication) was divided over the total of people assessed within the three STT arms.

The meta‐analysis showed that in an ITT analysis, the overall eradication proportion was higher with SEQ compared to STT (P < 0.001; Analysis 1.1). The risk difference (RD) for the overall ITT eradication of H. pylori was 0.09, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.06 to 0.11; participants = 12,701; 44 studies; and the NNTB was 13 with a 95% CI of 11 to 16.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Sequential therapy versus standard triple therapy, Outcome 1 Eradication proportion.

Results were highly heterogeneous (I² = 75%), so we considered a random‐effects model to be more appropriate to combine the dichotomous outcomes of the different studies.

Two studies (Aminian 2010; Greenberg 2011) demonstrated a significantly higher efficacy with STT. Both of the studies assessed adults: Aminian 2010 from Iran reported an ITT cure proportion of 91% and 80% with STT and SEQ respectively. Greenberg 2011, a multicentre trial in Latin America, reported an ITT cure proportion of 82% and 76% with STT and SEQ respectively. Two other studies (Lopez‐Román 2011; Zhou 2014) showed better efficacy of STT compared to SEQ, although differences between therapies were not statistically significant.

One included study (Laving 2013) reported the same ITT eradication in both treatment arms. The reason is that the test for assessment of H. pylori eradication was not performed in several participants allocated to the SEQ treatment arm. The per protocol analysis reported that 22 of 26 participants were cured in the SEQ arm while 22 of 45 were cured in the STT arm.

Twenty of the included studies did not demonstrate any clinical benefit for one regimen over the other. Thirteen of the studies (Ang 2015; Choi 2012; Gao 2010; Hsu 2014; Jeon 2013; Lee 2014; Lee 2015; Liou 2013; Liou 2014; Nasa 2013; Wu 2011; Yan 2011; Zhou 2014) were performed in Asia (mainly China and Korea but one in Japan, one in Singapore and one in India). The remaining studies were performed in South America (Lopez‐Román 2011; Eisig 2014), Africa (Laving 2013), Saudi Arabia (Ali Habib HS 2013), Turkey (Rakici 2014) or Europe (Bontems 2011; Franceschi 2011). All of them were conducted between 2011 and 2015.

Subgroup analyses: effects of different variables on the efficacy of both eradication treatments

Geographic region

Over half (n = 23) of the included studies were conducted in Asia, over one‐third (n = 15) were conducted in Europe and three each in South America and Africa (Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Sequential therapy versus standard triple therapy, Outcome 2 Geographic region.

Studies published in Europe had the greatest risk difference for SEQ versus STT (RD 0.16, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.19; 3796 participants; 15 studies; I² = 0%) when SEQ and STT were compared by subgroup analysis. Among the studies conducted in Europe (n = 15), most of them (n = 11) were conducted in Italy and the rest in Spain, Belgium, Poland and Slovenia. All but one of these studies (Bontems 2011) showed significant differences between therapies, and people given SEQ reported greater cure proportions than those given STT. Also, Molina‐Infante 2010 reported differences between SEQ and STT at a borderline statistical level (RD 0.12, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.24). Note that the four studies published outside Italy had a tendency towards lower efficacy with SEQ compared to STT than those studies conducted in Italy.

Studies conducted in Asia had a smaller risk difference for SEQ versus STT (RD 0.05, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.08; 6728 participants; 23 studies; I² = 60%) than those in Europe, Africa or South America. Most of the studies were conducted in China or Korea. Fifteen of them did not show significant differences between SEQ and STT, and results were heterogeneous. Among these 15 studies, five reported better efficacy with STT than with SEQ. The previous tendency for better efficacy with SEQ shown in the European studies was reduced in the Asian studies.

Among the studies conducted in Africa, the risk difference for SEQ versus STT was 0.14, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.22; 604 participants; 3 studies; I² = 25%. One study (Laving 2013) did not show a significant difference between SEQ and STT. Note that only three studies were included in this subgroup analysis and the reported confidence internal was wide; however, people tended to benefit more from SEQ than from STT.

The last subgroup analysis included studies conducted in South America, with a risk difference for SEQ versus STT reported as ‐0.06, 95% CI ‐0.10 to ‐0.01; 1156 participants; 3 studies; I² = 0%. One study (Eisig 2014) did not show a significant difference between SEQ and STT. The remaining two studies reported better cure proportions with STT than with SEQ, showing than participants in this subgroup could benefit more from STT than with SEQ, contrary to the results for other subgroups.

All subgroup analyses evaluating the geographic region presented significant differences between SEQ and STT showing SEQ was superior to STT but for the South American region where STT was significantly better than SEQ(test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 84.36, df = 3 (P < 0.001; I² = 96.4%).

Publication date

Included studies were published between 2002 and 2015. Given the evolution in the H. pylori resistance to antibiotics, which has been reported as increasing over the years, we planned a subgroup analysis in order to explore heterogeneity with respect to the year the study was conducted/published. SEQ was reported significantly superior to STT in both before and after 2008 subgroups and the treatment difference was supported by the test for subgroup differences (Chi² = 24.28, df = 1 (P < 0.001; I² = 95.9%).

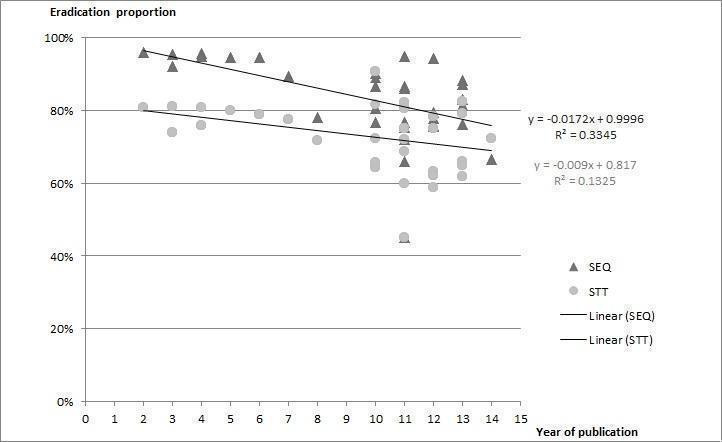

To evaluate the time trend and explore potential cut‐off points for this tendency, we generated a linear weighted regression model (Figure 4). The regression was controlled by each study weight (measured using a random‐effects model) following the statistical assumptions of the rest of the meta‐analysis. This model showed a tendency towards a lower efficacy through the years in the overall mean eradication proportion for both therapies.

4.

Weighted linear regression line in SEQ and STT by year of publication

As an exploratory model, it allowed us to identify a clear cut‐off point for subgrouping. Before 2008 the number of included studies per year was small and offered equivalent results (note that all the studies published before 2008 were of Italian origin); however, after 2009 the number of included trials per year increased and came from other countries and regions, and started to offer more heterogeneous results. No studies published in 2008 or 2009 met the inclusion criteria for our review.

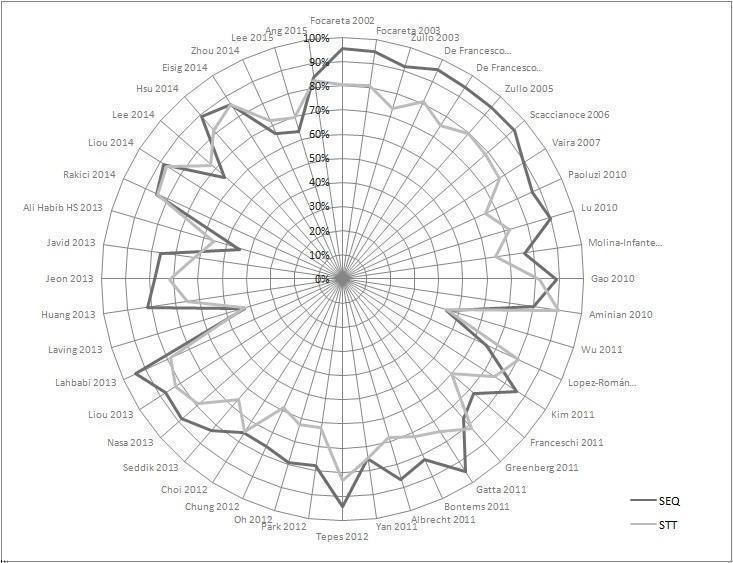

Furthermore, as shown in the radar chart in Figure 5, both STT and SEQ eradication appeared constant (or similar) between studies before 2008 but after this year eradication was shown to be irregular over time, as represented by the various plots around the tendency lines between 2008 and 2015. We therefore used the lapsus years 2008 and 2009 as a cut‐off point for the forest plot analyses.

5.

Radar chart depicting the eradication proportion for SEQ and STT in each included study

The forest plot (Figure 6; Analysis 1.3) presented differences in the eradication proportions between SEQ and STT among the studies performed before and after the year 2008. The risk difference for SEQ versus STT for the studies published before 2008 was 0.16, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.19; 2730 participants; 8 studies; I² = 0%, and the NNTB was 6 with a 95% CI of 5 to 7. The risk difference for SEQ versus STT for the studies published after 2008 was 0.06, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.09; participants = 10,021; studies = 36; I² = 69%. The NNTB was 18 and the 95% CI 14 to 26. Before 2008, studies reported higher eradication proportions and the RD was almost three times greater compared to studies published after 2008 (test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 24.28, df = 1 (P < 0.001); I² = 95.9%).

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Sequential therapy versus standard triple therapy, outcome: 1.3 Publication date.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Sequential therapy versus standard triple therapy, Outcome 3 Publication date.

Two Italian studies (Gatta 2011; Paoluzi 2010) reported significantly larger risk differences for SEQ versus STT in the ‘after 2008’ subgroup. There is a decrease in SEQ eradication proportions below 90% starting in year 2008, except for four studies in which cure proportions were greater than or equal to 90% (Gatta 2011; Lahbabi 2013; Lu 2010; Tepes 2012).

As previously noted in our weighted regression model, a decreased efficacy over the years was shown for both therapies; however, this trend was more pronounced for SEQ (‐1.79% per year) than for STT (‐0.9% per year), which coincides with the lower RD obtained in the 'after 2008' subgroup.

Age of the population

All but six included studies were conducted in adults, with studies conducted in children (Albrecht 2011; Ali Habib HS 2013; Bontems 2011; Huang 2013; Laving 2013; Lu 2010) first published from 2010 onwards.

The pooled risk difference for eradication of H. pylori with SEQ compared to STT in children was reported to be slightly higher than in adults (Analysis 1.4). The risk difference in the children subgroup was 0.13, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.19; participants = 826; studies = 6; I² = 0%, and for adults RD 0.08, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.11; participants = 11,356; studies = 38; I² = 77%. However, the test for subgroup differences was not significant (Chi² = 2.18, df = 1; P = 0.14, I² = 54.1%) and differences between subgroups could not be clearly supported.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Sequential therapy versus standard triple therapy, Outcome 4 Age of the population.

The NNTB in children was 8, with a 95% CI of 5 to 17, and in adults the NNTB was 13 with a 95% CI of 11 to 17.

Medical condition: non‐ulcer disease (NUD) versus peptic ulcer disease (PUD)

Twelve studies reported the baseline medical condition of participants. The risk difference for SEQ versus STT in the PUD group was 0.07, 95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.15; participants = 1822; studies = 9; I² = 81%, and in the NUD group the RD was 0.08, 95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.17; participants = 2293; studies = 8; I² = 87%. Differences between therapies were not significant (Analysis 1.5, test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 0.02, df = 1; P = 0.89, I² = 0%).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Sequential therapy versus standard triple therapy, Outcome 5 Medical condition.

Length of the standard triple therapy (STT)

Analysis 1.6 compares 10‐day SEQ versus 7‐day (22 studies), 10‐day (19 studies) and 14‐day (eight studies) STT. SEQ was significantly better than 7‐day and 10‐day STT, but we found no significant differences between 14‐day STT and 10‐day SEQ (P = 0.32).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Sequential therapy versus standard triple therapy, Outcome 6 STT length.

In the subgroup analysis, the H. pylori eradication proportions among the different STT lengths were compared with 10‐day SEQ. The risk difference in the 7‐day STT group was 0.14, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.17; participants = 5439; studies = 22; I² = 38%. In the 10‐day STT group, the risk difference was 0.06, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.10; participants = 3967; studies = 19; I² = 62%, and in the 14‐day STT group the RD was 0.02, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.06; participants = 3831; studies = 8; I² = 62%. The test for subgroup differences was significant (Chi² = 27.54, df = 2; P < 0.001; I² = 92.7%), supporting a clear difference between subgroups.

The NNTB when STT lasted seven days was 7, with a 95% CI of 6 to 8, and the NNTB when STT lasted 10 days was 20, with a 95% CI of 13 to 42.

Type of nitroimidazole

We included 43 studies in this subgroup meta‐analysis, with Liou 2014 not providing information on antibiotics or PPIs. Although we contacted the authors the information was not supplied.

Twenty‐one and 22 studies used metronidazole and tinidazole respectively in people treated with SEQ therapy. Both subgroups of people showed better results with SEQ than with STT (Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Sequential therapy versus standard triple therapy, Outcome 7 Nitroimidazole type.

In the metronidazole group, the risk difference for SEQ versus STT was 0.07, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.11; participants = 6088; studies = 21; I² = 74%. The NNTB was 17 with a 95% CI of 13 to 27. In the tinidazole group the risk difference for SEQ versus STT was 0.11, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.15; participants = 5356; studies = 22; I² = 64%. The NNTB was 9 with a 95% CI of 7 to 11.

However, differences between these two subgroups of people treated with different nitroimidazole types were not significant for H.pylori eradication. Individual study risk differences did not particularly overlap, and heterogeneity was therefore substantial (test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 2.23, df = 1; P = 0.14, I² = 55.2%).

Acid inhibition with proton‐pump inhibitor (PPI)

Both STT and SEQ regimens used different PPIs (omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole, or esomeprazole), as well as different PPI doses among the included studies. We performed a subgroup analysis to compare the efficacy of adjuvant medication within both treatment regimens. Acid inhibition was classified according to the type and dose of the PPI following the equivalences generally accepted (omeprazole 20 mg = pantoprazole 40 mg, lansoprazole 30 mg, rabeprazole and esomeprazole 20 mg).

We included 42 studies within this subgroup meta‐analysis. Two studies (Ang 2015; Liou 2014) were excluded, as they did not report data for PPI. In Ang 2015, we contacted the first author for the PPI information, who reported that most of the participants were given omeprazole standard doses, although some of them had rabeprazole or esomeprazole. We therefore decided not to include these data in the subgroup analysis, for consistency with the remaining included studies. We also excluded studies using paediatric injection formulations by participants' weight (Huang 2013; Lu 2010), as they cannot be pooled together with adult fixed‐tablet doses.

Only one study (Franceschi 2011) evaluated low acid inhibition with lansoprazole 15 mg twice a day, yielding a RD for SEQ versus STT of 0.24 (95% CI 0.05 to 0.43; 100 participants) for higher efficacy in SEQ. The majority of studies (n = 36) evaluated standard doses of the PPI, showing a marginally significant advantage for the use of SEQ versus STT (RD 0.09, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.12; 9794 participants). However, there was no increase in efficacy for SEQ in the three studies using potent acid inhibition (RD 0.02, 95% CI ‐0.17 to 0.21; 805 participants; Analysis 1.8).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Sequential therapy versus standard triple therapy, Outcome 8 PPI acid inhibition.

We found no differential effect based on levels of acid inhibition with PPI (test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 2.96, df = 2; P = 0.23, I² = 32.4%)

Bacterial antibiotic resistance

Most of the studies did not perform prior antibiotic susceptibility testing, and eight out of 44 (18%) studies reported eradication by bacterial antibiotic resistance (Analysis 1.9).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Sequential therapy versus standard triple therapy, Outcome 9 Bacterial antibiotic resistance.

We conducted subgroup meta‐analyses including separating H.pylori eradication for people with bacterial clarithromycin resistance, nitroimidazole resistance and dual resistance.

In the subgroup meta‐analyses, people with bacterial clarithromycin‐resistance eradication were significantly better when treated with SEQ therapy than with STT. The risk difference among this subgroup of participants was 0.33, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.54; participants = 214; studies = 8; I² = 64%. The NNTB was 3 with a 95% CI of 2 to 5. Although there seemed to be a similar trend for nitroimidazole resistance (87% versus 84%) and dual resistance (68% versus 63%), these apparent differences did not reach statistical significance.

Differences between all subgroups were significant, although heterogeneity in results was substantial (test for subgroup differences: Chi² = 7.12, df = 2; P = 0.03, I² = 71.9%). Additionally, the RD for SEQ versus STT within the clarithromycin‐resistance subgroup analysis was also greater compared to the risk difference of the overall eradication analysis (0.33 versus 0.13, respectively), meaning differences between treatment arms were even greater among those people with primary resistances.

Adverse events

Twenty‐seven studies (61%) described common adverse events (AEs) such as abdominal pain, diarrhoea, nausea, glossitis and vomiting, giving their incidence by treatment arms (Analysis 1.10). The trial reports did not mention whether there were any serious AEs.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Sequential therapy versus standard triple therapy, Outcome 10 Adverse events rate.

Within the SEQ arms the incidence of AEs ranged from 2% in Aminian 2010 to 57% in Lee 2015. In the STT arm the incidence ranged from 2% in Aminian 2010 to 55% in Liou 2013.

In the ITT meta‐analysis, the overall adverse event proportions showed no significant differences between SEQ and STT (20.4% versus 19.5%, respectively). None of the studies was able to demonstrate differences between the side effects of the therapies. The risk difference was RD 0.00, 95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.02; participants = 8103; studies = 27. Results were homogeneous (I² = 26%), so we used a fixed‐effect model as appropriate. The NNTH was 105 with a 95% CI of 37 to 126.

Compliance

Compliance rates were reported in 21 studies. However, compliance definitions varied across studies, being defined as "good compliance" in most of the studies if participants had taken between 90 and 95% of the pills. In one study (Greenberg 2011), authors did not specified a minimum intake and reported compliance rates at different levels: when participants had taken all pills (100%), nearly all (defined as more than 80%), most of the pills (between 50 and 80%), less than the half of the pills (less than 50%), undetermined (but not all) and none of the pills.

For instance, in the study by Park 2012 compliance proportions were lower than in the other studies in both treatment arms: 72% and 58% with SEQ and STT respectively. In the study by Aminian 2010, compliance was reported as 100% in both treatment arms.

Sensitivity analysis

Risk of bias

We conducted sensitivity analyses on the 'Risk of bias' items assessed during the review process, in order to see whether our findings were robust. The table below summarises the risk difference in the overall eradication proportion when studies categorised as 'unclear' or 'high risk' for each domain were excluded from the overall meta‐analysis.

| Risk of bias item | RD (95% CI) in sensitivity analysis | Impact on the overall eradication |

| Randomisation (n = 12 excluded studies) | *0.09 (0.05 to 0.12) | Differences between therapies are significant |

| Allocation concealment (n = 30 excluded studies) | 0.08 (0.03 to 0.13) | Differences between therapies are significant |

| Blinding (n = 35 excluded studies) | 0.08 (0.03 to 0.10) | Differences between therapies are significant |

| Incomplete outcome data (n = 12 excluded studies) | *0.11 (0.08 to 0.14) | Differences between therapies are significant |

| Publication format (n = 35 excluded studies) | *0.09 (0.05 to 0.12) | Differences between therapies are significant |

When we compared the different RDs with the overall pooled RD 0.09 95% CI 0.06 to 0.11 (Analysis 1.1), none of the items appeared to reduce the absolute risk of one treatment over the other, and for some of the domains (*) the absolute risk increased when we excluded the poorest‐quality studies.

Also, differences between treatment arms remained significant as in the overall analysis. The 'Risk of bias' items therefore do not appear to influence the overall results when we compare SEQ to STT.

Year of publication

Given the strong differences we found regarding the year of publication, we repeated all subgroup analyses separating publications by the year published (before or after 2008 ‐ 2009). This sensitivity analysis, summarised in the table below, showed effect difference in only two subgroup analyses.

In the subgroup analysis by baseline medical condition, the non‐significant tendencies towards the superiority of SEQ compared to STT, in both NUD and PUD people found using all time‐span studies (Analysis 1.5), were reduced and nearly eliminated in studies performed after 2008 or 2009.

For the length of the STT regimen, the previously reported benefit of SEQ when compared to 10‐day STT (Analysis 1.6), could not be demonstrated in the most recent studies (2010 onward), in which the efficacy of SEQ was equivalent to that of 10‐day STT.

| Subgroups by year of publication (after 2008 or 2009) | RD (95% CI) in sensitivity analyses | Impact on the overall eradication |

| Baseline medical condition ‐ PUD people | 0.02 (‐0.07 to 0.12) | Tendency towards lower/no differences between therapies |