Abstract

Background

Concern about the risk of upper genital tract infection (pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)) often limits use of the intrauterine device (IUD), a highly effective contraceptive. Prophylactic antibiotic administration around the time of induced abortion significantly reduces the risk of postoperative endometritis. Since the risk of IUD‐related infection is limited to the first few weeks to months after insertion, contamination of the endometrial cavity at the time of insertion appears to be the mechanism, rather than the IUD or string itself. Thus, antibiotic administration before IUD insertion might reduce the risk of upper genital tract infection from passive introduction of bacteria at insertion.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of prophylactic antibiotic administration before IUD insertion in reducing IUD‐related complications (pelvic inflammatory disease; complaints leading to an unscheduled visit) and discontinuations within three months of insertion.

Search methods

In February 2012, we searched MEDLINE, POPLINE, and CENTRAL. We also searched for current trials via ClinicalTrials.gov and ICTRP. Previous searches also included EMBASE. For the initial review, we examined reference lists and wrote to experts on several continents to identify unpublished trials.

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials using any antibiotic compared with a placebo.

Data collection and analysis

Two independent reviewers abstracted data. We made telephone calls to investigators to obtain additional information. We assessed the validity of each study using methods suggested in the Cochrane Handbook. We generated 2x2 tables for the principal outcome measures. The Peto modified Mantel‐Haenszel technique was used to calculate odds ratios. We assessed statistical heterogeneity between studies.

Main results

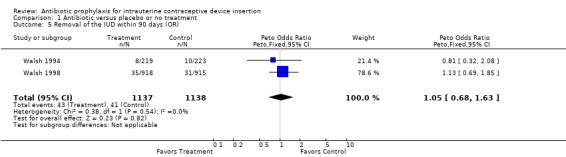

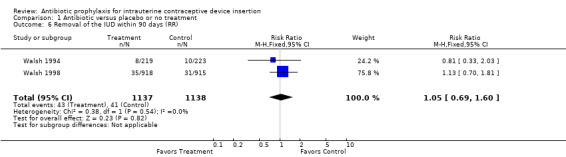

The odds ratio (OR) for pelvic inflammatory disease was 0.89 (95% Confidence Interval (CI) 0.53 to 1.51) for use of prophylactic doxycycline or azithromycin compared with placebo or no treatment. Use of prophylaxis was associated with a small reduction in unscheduled visits to the provider (OR 0.82; 95% CI 0.70 to 0.98). Use of doxycycline or azithromycin had little effect on the likelihood of removal of the IUD within 90 days of insertion (OR 1.05; 95% CI 0.68 to 1.63). No statistically significant heterogeneity between study results was detected.

Authors' conclusions

Use of either doxycycline 200 mg or azithromycin 500 mg by mouth before IUD insertion confers little benefit. While the reduction in unscheduled visits to the provider was marginally significant, the cost‐effectiveness of routine prophylaxis remains questionable. A uniform finding in these trials was the low risk of IUD‐associated infection, with or without use of antibiotic prophylaxis.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Antibiotic Prophylaxis; Intrauterine Devices; Intrauterine Devices/adverse effects; Bacterial Infections; Bacterial Infections/etiology; Bacterial Infections/prevention & control; Genital Diseases, Female; Genital Diseases, Female/etiology; Genital Diseases, Female/prevention & control; Pelvic Inflammatory Disease; Pelvic Inflammatory Disease/prevention & control; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Antibiotics for prevention with IUDs

An intrauterine device (IUD) is a small device placed in the womb for long‐term birth control. Many people worry about the woman getting pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) with an IUD. This infection can lead to problems in getting pregnant. If PID occurs, it is often within the first few weeks. Antibiotics are sometimes used before inserting an IUD to prevent an infection. This review looked at how well these preventive drugs reduced problems. Such problems include PID, extra health care visits, and stopping IUD use in three months.

In February 2012, we did a computer search for trials that compared an antibiotic to a placebo ('dummy'). We contacted researchers to get more information. We also wrote to researchers to find other trials.

Women who took antibiotics to prevent infection did not get PID as often as those who had the placebo or no treatment. However, the numbers with PID were low for all groups, so the treatment did not have a major effect. Women who use the drugs for prevention had fewer extra visits for health care. The small difference may not be enough to provide all women with the drugs. Using antibiotics to prevent infection did not change how many women had an IUD removed in three months.

Background

Concern about the risk of upper genital tract infection (pelvic inflammatory disease) often limits use of the IUD, a highly effective contraceptive. Prophylactic antibiotic administration around the time of induced abortion significantly reduces the risk of postoperative endometritis (Sawaya 1996) Since the risk of IUD‐related infection is largely limited to the first few weeks to months after insertion (Lee 1983; Farley 1992) contamination of the endometrial cavity at the time of insertion (Mishell 1966) appears to be the mechanism, rather than the IUD or string itself. Thus, antibiotic administration before IUD insertion might reduce the risk of upper genital tract infection from passive introduction of bacteria at insertion.

Objectives

To determine the effectiveness of oral antibiotics before IUD insertion in reducing the risk of IUD complications. In four reports, pelvic inflammatory disease (salpingitis) within 90 days was the principal outcome measure, and in two reports it was removal of the IUD for any reason other than partial expulsion within 90 days.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included only randomized controlled trials in this review. Two cohort studies have also addressed this question (Jovanovic 1988; Rogovskaya 1998), but we did not include them.

Types of participants

Women requesting IUD insertion who met local guidelines for IUD use. Specific inclusion and exclusion criteria appear in the table of trial characteristics. The African and Turkish trials specified admission criteria; in the Los Angeles trial, this decision was left to clinicians at the participating clinical sites. These varied by site but reflected package labeling of U.S. IUDs, which limits their use to low‐risk women.

Types of interventions

Doxycycline 200 mg by mouth one hour before insertion (four reports), doxycycline 200 mg by mouth one hour before insertion followed by 200 mg daily for two days (one report), or azithromycin 500 mg by mouth one hour before insertion (one report).

Types of outcome measures

Three principal outcomes measures were pelvic inflammatory disease, unscheduled visits to the clinic, and removal of the IUD within three months of insertion. One study reported febrile morbidity without a clinical diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease (Zorlu 1993). Because of the infrequency of upper genital tract infection, the trial by Walsh et al. used premature IUD discontinuation as the primary outcome measure (Walsh 1994; Walsh 1998).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

In February 2012, we searched the computerized databases MEDLINE using PubMed, POPLINE, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). In addition, we searched for recent clinical trials through ClinicalTrials.gov and the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP). The search strategy is given in Appendix 1. The previous search strategy, which also included EMBASE, can be found in Appendix 2.

Searching other resources

For the initial review, we reviewed the reference lists of identified articles and wrote to IUD experts on several continents to seek trials we might have missed. The pilot study for the Los Angeles trial (Walsh 1998) was published separately as Walsh 1994. We contacted these investigators to get the number of women who made one or more unscheduled visits, but this information had not been collected in the pilot phase. Since the pilot study (Sinei 1985) for the main Kenya trial (Sinei 1990) was not published, we contacted the investigators to get these data. We attempted to contact one author (Zorlu 1993) by mail but without success.

Data collection and analysis

Both authors screened potentially relevant trials. Agreement occurred on trial identification and data abstraction. This review presents only the Peto odds ratios. We assessed clinical heterogeneity by reviewing characteristics of participants in these trials, which were conducted on three continents. Statistical heterogeneity was evaluated by using a chi‐squared test.

Results

Description of studies

Women enrolling in the four different trials met local criteria for IUD insertion. In the African trials (Sinei 1990; Ladipo 1991), IUD was less restrictive than in the other trials (see Characteristics of included studies). The prevalence of cervical infections with Neisseria gonorrhoeae among participants in the Kenya trial was 3% (Sinei 1990), while that in the Nigerian trial was 1% (Ladipo 1991). The prevalence of Chlamydia trachomatis in the cervix was higher (11% and 7%, respectively).

Risk of bias in included studies

Several of the trials were of high quality. The Kenyan trial (Sinei 1985; Sinei 1990), Nigerian trial (Ladipo 1991), and Los Angeles trial (Walsh 1994; Walsh 1998) featured adequate allocation concealment, double blinding of treatment, and intent‐to‐treat analysis. However, the Nigerian trial stopped prematurely, and the incidence of pelvic inflammatory disease is higher than that of unscheduled visits to the clinic, a doubtful occurrence. The Turkish trial (Zorlu 1993) did not describe its method of randomization. No placebo was provided, and blinding was not maintained. No sample size calculation is available.

Effects of interventions

We found four randomized controlled trials; two had pilot study data available. The primary outcomes studied were pelvic inflammatory disease (four reports), unscheduled visits back to the clinic (four reports), or early removals of the device (two reports).

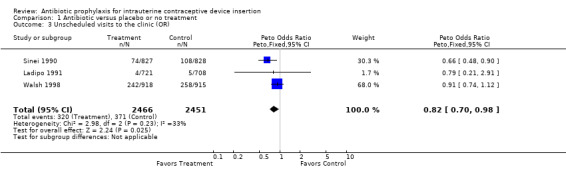

The Kenyan trial found a significant reduction in unscheduled visits, and the meta‐analysis had an odds ratio of 0.82 (95% CI 0.70 to 0.98) (Sinei 1990). No other significant benefit emerged when the trials were combined.

The Kenyan trial found that doxycycline reduced the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease by about one‐third, which was not statistically significant (Relative risk (RR) 0.69; 95% CI 0.32 to 1.47) (Sinei 1990). PID was diagnosed with the Hager 1983 criteria. A similar reduction in unscheduled return visits because of an IUD‐related problem was statistically significant (RR 0.69; 95% CI 0.52 to 0.91). The Nigerian trial, which attempted to replicate the Kenyan trial, found no benefit of prophylaxis in reducing either salpingitis or unscheduled visits (Ladipo 1991).

The Los Angeles trial, which focused on premature IUD discontinuation, found no overall benefit of prophylactic azithromycin (RR 1.13; 95% CI 0.70 to 1.81) (Walsh 1998). Only one case of pelvic inflammatory disease occurred in each treatment group. Similarly, the rate of unscheduled visits to the provider did not differ significantly.

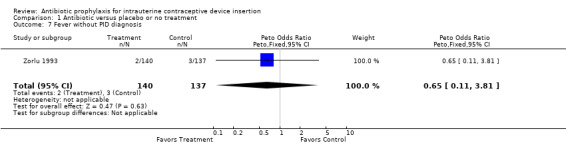

The Turkish trial found no significant difference in rates of pelvic inflammatory disease (Zorlu 1993).

No statistically significant heterogeneity was detected between studies' results. Nevertheless, important clinical differences existed between women in these four countries, notably the high prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases among women enrolled in the African studies.

We performed a sensitivity analysis by including only the four trials with rigorous methods (Sinei 1985; Sinei 1990; Walsh 1994; Walsh 1998). This allowed a reassessment of two outcome measures: pelvic inflammatory disease and unscheduled visits back to the clinic. For pelvic inflammatory disease, the odds ratio from this meta‐analysis was 0.70 (95% CI 0.36 to 1.38). The odds ratio for unscheduled visits from the meta‐analysis was unchanged (0.82; 95% CI 0.70 to 0.98).

Discussion

Use of prophylactic antibiotics before IUD insertion reduced the likelihood of an unscheduled visit to provider by 18%, which was marginally statistically significant. No other important benefits were observed, specifically reduction in upper genital tract infection or improvement in IUD continuation rates.

In Kenya, where the prevalence of gonorrhea and chlamydial infection was high, doxycycline was associated with a reduction in both upper genital tract infection and unscheduled visits. This was not seen in Nigeria, where the prevalence of these two infections was not as high. Nevertheless, the discrepancy between rates of salpingitis and unscheduled visits in the Nigerian trial remains unexplained after discussions with the investigators. In populations with a high prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases, such as Kenya (Sinei 1990), prophylaxis may offer modest protection against both pelvic inflammatory disease and unscheduled visits to the clinic.

The trial from Los Angeles found little effect with either doxycycline (Walsh 1994) or azithromycin (Walsh 1998). The latter drug has the appeal of a very long half‐life and low incidence of gastrointestinal side effects. Nevertheless, the cost of the 500 mg dose is higher than that of doxycycline 200 mg.

The sensitivity analysis using only rigorous trials showed more protection (OR 0.70) against pelvic inflammatory disease than did the overall meta‐analysis (OR 0.89). Nevertheless, this difference was not statistically significant. Excluding Ladipo 1991 from the meta‐analysis of unscheduled visits had no effect.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The overriding message from these four trials is that contemporary IUD use is safe, with or without use of prophylactic antibiotics. This holds true for populations with a high prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases, as is the case in much of Africa. The concern about high rates of upper genital tract infection (Lee 1983; Farley 1992), even in the critical early months of use, appears unwarranted. As noted by the World Health Organization, contemporary copper IUDs are among the safest and most effective reversible methods of contraception available today.

Use of prophylactic antibiotics may reduce the likelihood of an unscheduled visit back to the clinic. Authors have suggested that complaints of pain and bleeding associated with IUD use may represent subclinical endometritis (Sinei 1990). Antibiotic administration may reduce this risk and thus lead to fewer problem visits. While fewer problem‐related visits will save money and reduce inconvenience, prophylaxis would probably only be cost‐effective where sexually transmitted diseases are common, as observed in the study from Kenya (Sinei 1990).

Implications for research.

The low rate of infection or premature removals of IUDs is important clinical news. On the other hand, the low incidence of IUD‐related problems poses difficult challenges for researchers. The Kenyan trial, which enrolled over 1800 women, had insufficient power to identify the anticipated treatment effect. In the Los Angeles trial, the investigators anticipated the low incidence of pelvic inflammatory disease and focused instead on premature IUD discontinuation as the primary outcome measure. In the main trial with over 1800 participants, only two cases of salpingitis occurred.

Additional studies of prophylactic antibiotics in low‐risk populations appear unjustified. In women at higher risk, further research may be considered. However, because of the low incidence of PID even in these settings, the number of women needed to treat to avert a single case of infection will be large.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 28 March 2012 | New search has been performed | Searches were updated. No new trials were found. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 1998 Review first published: Issue 3, 1999

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 October 2009 | New search has been performed | Searches were updated and searches of clinical trial databases were added. No new trials were found. |

| 14 April 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 8 March 1999 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

Carol Manion of FHI 360 assisted with the literature search. Sarah Mullins of FHI 360 helped review search results in 2012.

Appendices

Appendix 1. 2012 Searches

MEDLINE via PubMed (22 June 2009 to 28 Feb 2012)

(iud* OR iucd* OR intrauterine devices OR intrauterine device) AND insert* AND (antibiotic*/antibiotic prophylaxis)

CENTRAL (22 Jun 2009 to 23 Feb 2012)

(intrauterine AND device) OR IUD in Abstract AND antibiotic* AND infection in Abstract

POPLINE (29 June 2009 to 29 Feb 2012)

(iud*/iucd*/intrauterine device*/ intrauterine contraceptive device*) & insert* & antibiotic*

ClinicalTrials.gov (30 June 2009 to 24 Feb 2012)

Search terms: antibiotic AND (iud OR iucd OR intrauterine devices OR intrauterine device) Conditions: NOT (endometriosis OR endometrial OR HIV OR cancer)

ICTRP (25 June 2009 to 24 Feb 2012)

iud OR iucd OR intrauterine devices OR intrauterine device

Appendix 2. Previous Searches

Below are the previous search methods, along with dates from the 2009 search. We conducted searches of MEDLINE using PubMed, POPLINE, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and EMBASE. Starting in 2009, we also searched for current trials via ClinicalTrials.gov and ICTRP.

MEDLINE via PubMed (22 Sep 2009)

(iud* OR iucd* OR intrauterine devices OR intrauterine device) AND insert* AND (antibiotic*/antibiotic prophylaxis)

CENTRAL (22 Sep 2009)

(intrauterine AND device) OR IUD in Abstract AND antibiotic* AND infection in Abstract

POPLINE (29 Sep 2009)

(iud*/iucd*/intrauterine device*/ intrauterine contaceptive device*) & insert* & antibiotic*

EMBASE (30 Sep 2009)

s iud or intrauterine device or intrauterine contraceptive device s insert? s s1 and s2 s iud(3n)insert? or IUCD(3n)insert? or intrauterine()device(3n)insert? or intrauterine()contraceptive()device(3n)insert? s s3 or s4 s antibiotic or antibiotics or antibiotic?()prophylaxisis s s5 and s6 s s7 and pd=20070209:20090930 t s8/6/all t s8/4/4,5,6,8,9

ClinicalTrials.gov (25 Sep 2009)

Search terms: iud OR iucd OR intrauterine devices OR intrauterine device Conditions: NOT (endometriosis OR endometrial OR HIV OR cancer)

ICTRP (25 Sep 2009)

iud OR iucd OR intrauterine devices OR intrauterine device

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Antibiotic versus placebo or no treatment.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

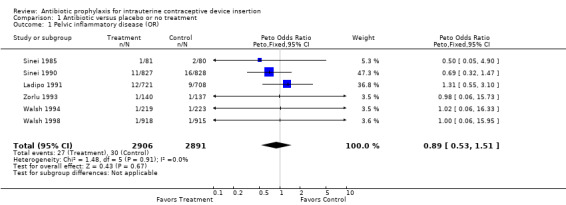

| 1 Pelvic inflammatory disease (OR) | 6 | 5797 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.53, 1.51] |

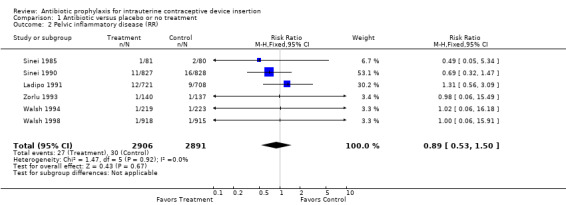

| 2 Pelvic inflammatory disease (RR) | 6 | 5797 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.53, 1.50] |

| 3 Unscheduled visits to the clinic (OR) | 3 | 4917 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.70, 0.98] |

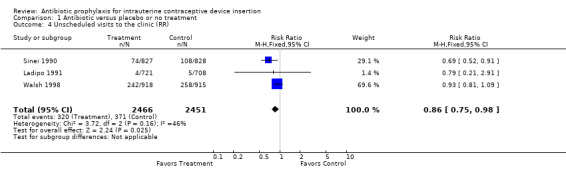

| 4 Unscheduled visits to the clinic (RR) | 3 | 4917 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.75, 0.98] |

| 5 Removal of the IUD within 90 days (OR) | 2 | 2275 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.68, 1.63] |

| 6 Removal of the IUD within 90 days (RR) | 2 | 2275 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.69, 1.60] |

| 7 Fever without PID diagnosis | 1 | 277 | Peto Odds Ratio (Peto, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.11, 3.81] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antibiotic versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 1 Pelvic inflammatory disease (OR).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antibiotic versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 2 Pelvic inflammatory disease (RR).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antibiotic versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 3 Unscheduled visits to the clinic (OR).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antibiotic versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 4 Unscheduled visits to the clinic (RR).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antibiotic versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 5 Removal of the IUD within 90 days (OR).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antibiotic versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 6 Removal of the IUD within 90 days (RR).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Antibiotic versus placebo or no treatment, Outcome 7 Fever without PID diagnosis.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Ladipo 1991.

| Methods | Computer‐generated randomization; allocation concealment by prepackaged pill bottles with drug or identical‐appearing placebo. | |

| Participants | 1485 women requesting IUDs from University College Hospital, Ibaden, Nigeria. Inclusion criteria: age 20 to 44 years and current menstruation. Exclusion criteria: history of ectopic pregnancy, pregnancy within 42 days, leiomyomata uteri, current salpingitis, uterine malignancy, sensitivity to tetracyclines, antibiotic administration within 14 days, impaired immune response, residence outside of Ibaden, or poor likelihood of follow up. All women were screened for gonorrhea and chlamydial infection. | |

| Interventions | Doxycycline 200 mg by mouth one hour before IUD insertion or an identical‐appearing placebo. | |

| Outcomes | Pelvic inflammatory disease diagnosed by Hager et al. criteria; unscheduled visits back to the clinic. | |

| Notes | Rates of pelvic inflammatory disease exceeded rates of unscheduled visits; study did not reach intended sample size (1800) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Allocation concealment by prepackaged pill bottles with drug or identical‐appearing placebo |

Sinei 1985.

| Methods | See Sinei 1990 | |

| Participants | 180 women (see Sinei 1990) | |

| Interventions | See Sinei 1990 | |

| Outcomes | Pelvic inflammatory disease diagnosed by Hager 1983 criteria | |

| Notes | Pilot study for Sinei 1990 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | See Sinei 1990 |

Sinei 1990.

| Methods | Computer random number generator with blocked randomization, randomly varied block lengths. Allocation concealment by pre‐labeled pill bottles with drug or identical‐appearing placebo. | |

| Participants | 1813 women requesting IUDs in family planning clinic at Kenyatta National Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya. Inclusion criteria: 20 to 44 years old with regular menses. Exclusion criteria: history of ectopic pregnancy, pregnancy within 42 days, leiomyomata uteri, active salpingitis, uterine malignancy, hypersensitivity to tetracyclines, antibiotic administration within 14 days, impaired immune response, residence outside Nairobi or low likelihood of follow up. All patients were screened for gonorrhea and chlamydial infection. | |

| Interventions | Doxycycline 200 mg by mouth one hour before IUD insertion or identical‐appearing placebo. | |

| Outcomes | Pelvic inflammatory disease diagnosed by Hager 1983 criteria; unscheduled visits back to the clinic. | |

| Notes | High follow rates; rigorous methods. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Allocation concealment by pre‐labeled pill bottles with drug or identical‐appearing placebo |

Walsh 1994.

| Methods | See Walsh 1998. | |

| Participants | 447 women (See Walsh 1998). | |

| Interventions | Doxycycline 200 mg by mouth one hour before IUD insertion or an identical‐appearing placebo. | |

| Outcomes | IUD removal for medical reasons, including pelvic inflammatory disease, within three months of insertion. | |

| Notes | Pilot study for Walsh 1998. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | See Walsh 1998 |

Walsh 1998.

| Methods | Computer‐generated randomization with block size of ten at each site; allocation concealment by prepackaged pill bottles that were identical, opaque, and sealed. Bottles contained drug or identical‐appearing placebo. | |

| Participants | 1867 women requesting IUDs from 11 clinical sites in Los Angeles County, California. Inclusion and exclusion criteria determined locally at each site. All participants were screened for gonorrhea and chlamydial infection; 70% had screening done before insertion and 30% at the time of insertion. | |

| Interventions | Azithromycin 500 mg by mouth one hour before insertion or an identical‐appearing placebo. | |

| Outcomes | IUD removal for medical reasons, including pelvic inflammatory disease, within 90 days of insertion. | |

| Notes | Table includes total number of follow‐up visits, not patients with one or more visits. Supplemental information obtained from investigator. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Allocation concealment by prepackaged pill bottles that were identical, opaque, and sealed. Bottles contained drug or identical‐appearing placebo. |

Zorlu 1993.

| Methods | Method of randomization not specified. Method of allocation concealment not stated. No blinding or placebo. | |

| Participants | Women requesting IUDs in the family planning clinic in Dr. Zekai Tahir Burak Women's Hospital, Ankara, Turkey. Exclusion criteria: previous ectopic pregnancy, pregnancy within 3 months, active salpingitis, dysfunctional uterine bleeding, diagnosed or suspected genital malignancy, antibiotic administration within one month, and any organic pelvic disease. | |

| Interventions | Doxycycline 200 mg by mouth one hour before IUD insertion, followed by 200 mg daily for two days versus no treatment. | |

| Outcomes | Pelvic inflammatory disease (requiring fever plus other criteria) and febrile morbidity without a diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease. | |

| Notes | Antibiotic prophylaxis regimen lasted three days. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Method of allocation concealment not stated. |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Jovanovic 1988 | Not a randomized controlled trial. |

| Rogovskaya 1998 | Not a randomized controlled trial. |

Contributions of authors

D Grimes and K Schulz developed the proposal, conducted the literature search, abstracted the data, performed the analysis, and wrote the review. L Lopez reviewed the search results from 2007 to 2012, edited the manuscript for current style issues, and wrote the Plain Language Summary.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

U.S. Agency for International Development, USA.

Declarations of interest

Drs. Grimes and Schulz were investigators in the Kenya trial (Sinei 1985; Sinei 1990) and Dr. Grimes in the Los Angeles trial (Walsh 1994; Walsh 1998) included in this review.

Dr. Grimes has consulted with the pharmaceutical companies Bayer Healthcare Pharmaceuticals and Merck & Co, Inc.

New search for studies and content updated (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Ladipo 1991 {published data only}

- Ladipo OA, Farr G, Otolorin E, Konje JC, Sturgen K, Cox P, et al. Prevention of IUD‐related pelvic infection: the efficacy of prophylactic doxycycline at IUD insertion. Advances in Contraception 1991;7:43‐54. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sinei 1985 {unpublished data only}

- Sinei SKA, Schulz KF, Lamptey PR, Grimes DA, Mati JKG, Rosenthal SM, et al. Kenya, January 14, 1985 ‐ February 7, 1985. Consultation regarding the analysis of the pilot phase and the initiation of the full‐scale phase of the randomized clinical trial of prophylactic doxycycline at the time of IUCD insertion to prevent pelvic inflammatory disease. Schulz KF: Foreign trip report (AID/RSSA); 1985 Feb.

Sinei 1990 {published data only}

- Sinei SKA, Schulz KF, Lamptey PR, Grimes DA, Mati JKG, Rosenthal SM, et al. Preventing IUCD‐related pelvic infection: the efficacy of prophylactic doxycycline at insertion. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology 1990;97:412‐9. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Walsh 1994 {published data only}

- Walsh TL, Bernstein GS, Grimes DA, Frezieres R, Bernstein L, Coulson AH. Effect of prophylactic antibiotics on morbidity associated with IUD insertion: results of a pilot randomized controlled trial. IUD Study Group. Contraception 1994;50:319‐27. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Walsh 1998 {published and unpublished data}

- Walsh T, Grimes D, Frezieres R, Nelson A, Bernstein L, Coulson A, et al. Randomised controlled trial of prophylactic antibiotics before insertion of intrauterine devices. Lancet 1998;351:1005‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zorlu 1993 {published data only}

- Zorlu CG, Aral K, Cobanoglu O, Gurler S, Gokmen O. Pelvic inflammatory disease and intrauterine devices: prophylactic antibiotics to reduce febrile complications. Advances in Contraception 1993;9:299‐302. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Jovanovic 1988 {published data only}

- Jovanovic R, Barone CM, Natta FC, Congema E. Preventing infection related to insertion of an intrauterine device. Journal of Reproductive Medicine 1988;33:347‐52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rogovskaya 1998 {unpublished data only}

- Rogovskaya SI. Prophylaxis of complications connected with intrauterine contraception [dissertation]. Moscow (Russia): Research Centre of Ob/Gyn and Perinatology, 1998. [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Farley 1992

- Farley TMM, Rosenberg MJ, Rowe P, Chen J‐H, Meirik O. Intrauterine devices and pelvic inflammatory disease: an international perspective. Lancet 1992;339:785‐8. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hager 1983

- Hager WD, Eschenbach DA, Spence MR, Sweet RL. Criteria for diagnosis and grading of salpingitis. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1983;61:113‐4. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lee 1983

- Lee NC, Rubin GL, Ory HW, Burkman RT. Type of intrauterine device and the risk of pelvic inflammatory disease. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1983;62:1‐6. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mishell 1966

- Mishell DR Jr, Bell JH, Good RG, Moyer DL. The intrauterine device: a bacteriologic study of the endometrial cavity. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1966;96:119‐26. [MEDLINE: ] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sawaya 1996

- Sawaya GF, Grady D, Kerlikowske K, Grimes DA. Antibiotics at the time of induced abortion: the case for universal prophylaxis based on a meta‐analysis. Obstetrics and Gynecology 1996;87:884‐90. [MEDLINE: ] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]