Abstract

Background

The combinatorial effect of multiple genetic factors calculated as a polygenic risk score (PRS) has been studied to predict disease progression to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) from mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Previous studies have investigated the performance of PRS in the prediction of disease progression to AD by including and excluding single nucleotide polymorphisms within the region surrounding the APOE gene. These studies may have missed the APOE genotype-specific predictability of PRS for disease progression to AD.

Methods

We analyzed 732 MCI from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative cohort, including those who progressed to AD within 5 years post-baseline (n = 270) and remained stable as MCI (n = 462). The predictability of PRS including and excluding the APOE region (PRS+APOE and PRS−APOE) on the conversion to AD and its interaction with the APOE ε4 carrier status were assessed using Cox regression analyses.

Results

PRS+APOE (hazard ratio [HR] 1.468, 95% CI 1.335–1.615) and PRS−APOE (HR 1.293, 95% CI 1.157–1.445) were both associated with a significantly increased risk of MCI progression to dementia. The interaction between PRS+APOE and APOE ε4 carrier status was significant with a P-value of 0.0378. The association of PRSs with the progression risk was stronger in APOE ε4 non-carriers (PRS+APOE: HR 1.710, 95% CI 1.244–2.351; PRS−APOE: HR 1.429, 95% CI 1.182–1.728) than in APOE ε4 carriers (PRS+APOE: HR 1.167, 95% CI 1.005–1.355; PRS−APOE: HR 1.172, 95% CI 1.020–1.346).

Conclusions

PRS could predict the conversion of MCI to dementia with a stronger association in APOE ε4 non-carriers than APOE ε4 carriers. This indicates PRS as a potential genetic predictor particularly for MCI with no APOE ε4 alleles.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40035-021-00259-w.

Keywords: Polygenic risk score, Mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, Disease progression, APOE ε4

Background

Predicting disease progression to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) from mild cognitive impairment (MCI) is critical for identifying individuals for opportune intervention in clinical management and for optimization of target participants in clinical trials. The use of individualized genetic profile is thriving with a pursuit of precision medicine and is becoming approachable with shared large data, which may facilitate customized risk prediction of disease development and progression. The heritability of late-onset AD (LOAD) is high, accounting for 60%–80% [1], and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified multiple genetic factors associated with AD including the well-known APOE ε4 allele [2, 3]. The combinatorial effect of these multiple genetic factors can be calculated as a polygenic risk score (PRS). PRS has been widely evaluated in AD research regarding its value in AD risk prediction, its relations with conventional biomarkers of AD, and its prediction of disease conversion from MCI to AD [4]. In particular, the predictability of PRS on disease progression from MCI to AD is substantially affected by the presence of APOE ε4 allele, and PRS excluding the APOE region may or may not predict disease progression [5–8].

In this study, we aimed to investigate the predictability of PRSs including and excluding single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within the region surrounding the APOE gene, on MCI progression to AD, and the interaction between PRS and APOE ε4 alleles. In addition, the predictability of hippocampal volume on MRI and amyloid PET were assessed, which are well-known predictors of disease progression. Furthermore, we identified SNPs used for PRS calculation and then performed enrichment analysis to explore the implicated biological pathways.

Methods

Participants

Data used in this study were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (http://adni.loni.usc.edu/). ADNI was launched in 2003 as a public–private partnership. The primary goal of ADNI has been to test whether serial MRI, PET, other biological markers, and clinical neuropsychological assessment can be combined to measure the progression of MCI and early AD [9]. In this study, patients with a diagnosis of MCI and with available GWAS data, older than 60 years at baseline assessment, and having at least one or more follow-up visits, were included. We focused on the genetic risk estimation of LOAD, in which the threshold cutoff of 60 years is commonly used. The primary outcome of this study was MCI conversion to dementia during a follow-up period up to 5 years post-baseline. MCI was diagnosed when there was objective memory impairment but without meeting the criteria for dementia [9]. The MCI participants had Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores between 24 and 30, memory performance scores approximately 1 standard deviation below expected education-adjusted norms, and a clinical dementia rating score of 0.5.

Genotyping and imputation

Genotyping for ADNI was performed using blood DNA samples and a combination of Illumina GWAS array platforms (Illumina Human610-Quad BeadChip, Illumina HumanOmni Express BeadChip, and Illumina HumanOmni 2.5 M BeadChip) [10]. APOE genotyping was separately conducted using previously described standard methods to yield the APOE ε4 allele-defining SNPs (rs429358, rs7412) [10, 11]. Using PLINK 1.9 (www.cog-genomics.org/plink2/) [12], we performed standard quality control (QC) procedures for samples and SNPs as described previously [13]: (1) for SNPs: SNP call rate < 95%, Hardy–Weinberg P value < 1 × 10–6, and minor allele frequency (MAF) < 1%; (2) for samples: sex inconsistencies, and sample call rate < 95%. Then, to prevent spurious associations due to population stratification, we used multidimensional scaling analysis to select only non-Hispanic participants of European ancestry that clustered with HapMap CEU (Utah residents with Northern and Western European ancestry from the CEPH collection) or TSI (Toscani in Italia) populations (Additional file 1: Fig. S1) [14, 15]. After QC procedures, we imputed un-genotyped SNPs separately in each platform using MaCH with the Haplotype Reference Consortium data as a reference panel [16, 17]. Following the imputation, we imposed an r2 value of 0.30 as the threshold to accept the imputed genotypes [18].

Imaging biomarkers

T1-weighted brain MRI scan was processed with FreeSurfer version 5.1 to measure hippocampal and intracranial volumes [19]. For assessment of cortical amyloid accumulation, we used preprocessed (coregistered, averaged, standardized image and voxel size, uniform resolution) [18F] florbetapir PET scans [20] and calculated the mean standardized uptake value ratio (SUVR) using a whole cerebellum reference region as previously described [21]. In our analysis, amyloid burden on PET was dichotomized as positive when SUVR ≧ 1.17 and negative when SUVR < 1.17 [22].

Calculation of PRS

PRSs were calculated using the software PRSice v2.3.1.e [23]. The GWAS summary statistics from Jansen et al. were used as a base dataset [2] and the phase 3 genetic data from the 1000 Genomes Project [24] for non-Hispanic participants of European ancestry were used to calculate the linkage disequilibrium structure. To investigate the optimal P-value threshold to select AD-associated SNPs, we iterated P-value thresholds of 1 × 10–6, 1 × 10–5, 1 × 10–4, 1 × 10–3, 1 × 10–2, 0.05, and 0.5. PRSs were separately calculated including and excluding SNPs within the 1 Mb-region surrounding the APOE gene, which was defined as a region from 1 Mb before rs429358 to 1 Mb after rs7412. The numbers of SNPs used for PRS calculation depending on the various P-value thresholds are shown in Additional file 1: Table S1. In addition, PRS was z-transformed based on the PRS distribution among amyloid PET-negative cognitively normal participants (n = 138).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were made using the R v4.0.2 software (www.R-project.org). Comparisons of demographics between stable MCI, who remained stable at MCI during 5 years after baseline, and progressive MCI, who progressed to dementia within 5 years, were made with Mann–Whitney U test and Chi-squared test as appropriate.

To assess the predictability of PRS, hazard ratio (HR) of PRS in z-scores was obtained with Cox regression analysis. PRSs including and excluding SNPs within the 1 Mb-region surrounding the APOE gene were analyzed and represented as PRS+APOE and PRS−APOE, respectively. PRS analyses were performed in all MCI patients, MCI carrying the APOE ε4 alleles, and MCI not carrying the APOE ε4 alleles, separately. Cox regression analyses of PRS are presented as Kaplan Meier curves. The interaction between PRSs and APOE ε4 carrier status was also assessed. To evaluate the predictability of MRI hippocampal volume, the hippocampal volume was divided by the intracranial volume and z-transformed based on the distribution of values within amyloid PET-negative cognitively normal older adults. The HR of APOE ε4 carriers was compared to APOE ε4 non-carriers, and the HR of amyloid PET-positive MCI was compared to amyloid PET-negative MCI. All analyses were adjusted with age and sex, and additionally with MRI field strength in hippocampal volume analysis. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Functional interpretation of SNPs used for PRS calculation

Functional mapping and annotation of SNPs used for PRS calculation was performed with the FUMA v1.3.6a software [25]. The GWAS summary statistics of SNPs were obtained from Jansen et al. [2]. All known SNPs that had r2 ≥ 0.6 with one of the independent significant SNPs used for PRS calculation, were also included for gene mapping using FUMA. Gene mapping was conducted by three methods, including positional mapping, expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) mapping, and chromatin interaction mapping. In the positional mapping, SNPs were mapped to genes with a maximum distance of 10 kb. eQTL data from the eQTL catalogue (BrainSeq brain) [26], the Blood eQTLs (Westra et al. (2013) Blood eQTL Browser [27], Zhernakiva et al. (2017) BIOS QTL Browser [28]), the BRAINEAC (averaged expression of 10 brain regions including frontal cortex, hippocampus, occipital cortex, temporal cortex, cerebellar cortex, inferior olivary nucleus, putamen, substantia nigra, thalamus, and intralobular white matter) [29], and the GTEx v8 Brain (cortex, frontal cortex BA9, hippocampus)[30] datasets were used for eQTL mapping, and only significant SNP-gene pairs with a false discovery rate (FDR) cutoff of 0.05 were used. The chromatin interaction mapping was performed with data from the HiC (GSE87112) dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and hippocampus [31] with FDR cutoff of 1 × 10–6 and promotor region window of 250 bp up- and 500 bp down-stream of the transcription start site. The possible biological processes (BP), molecular functions (MF), and involved cellular components (CC) of mapped genes were explored by gene set enrichment analysis using data from the gene ontology (GO) [32, 33]. Statistical significance was set at adjusted P-value < 0.05.

Results

A total of 907 MCI participants from the ANDI cohort were assessed for study eligibility. After excluding 48 participants younger than 60 years, 68 without follow-up visit, and 59 without available GWAS data, 732 participants were finally included for the analysis. Of the 732 MCI participants, 270 MCI patients (36.8%) were converted to dementia within 5 years (“progressive MCI”) and 462 MCI patients remained at MCI (“stable MCI”). There was no significant difference in age, sex, or education level at baseline between the two groups. The progressive MCI group had a significantly higher proportion of APOE ε4 allele-carriers, lower MMSE scores and higher clinical dementia rating sum of boxes (CDR-SB) scores at baseline (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics of participants

| Stable MCI (n = 462) | Progressive MCI (n = 270) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 73 (67–79) | 74 (69–79) | 0.109 |

| Female, n (%) | 179 (38.74) | 105 (38.89) | 1.000 |

| Education, years | 16 (14–18) | 16 (14–18) | 0.481 |

| APOE ε4 carrier, n (%)* | 196 (42.52) | 182 (67.41) | < 0.001 |

| MMSE | 28 (27–29) | 27 (26–28) | < 0.001 |

| CDR-SB | 1 (0.5–1.5) | 2 (1.0–2.5) | < 0.001 |

Data are presented as median (interquartile range) unless otherwise specified

*Data unavailable for 1 subject

We examined seven P-value thresholds to find the optimal threshold for selection of AD-associated SNPs, and the model with threshold P < 1 × 10–5 showed the best predictability and was used for further analysis (Additional file 1: Table S2).

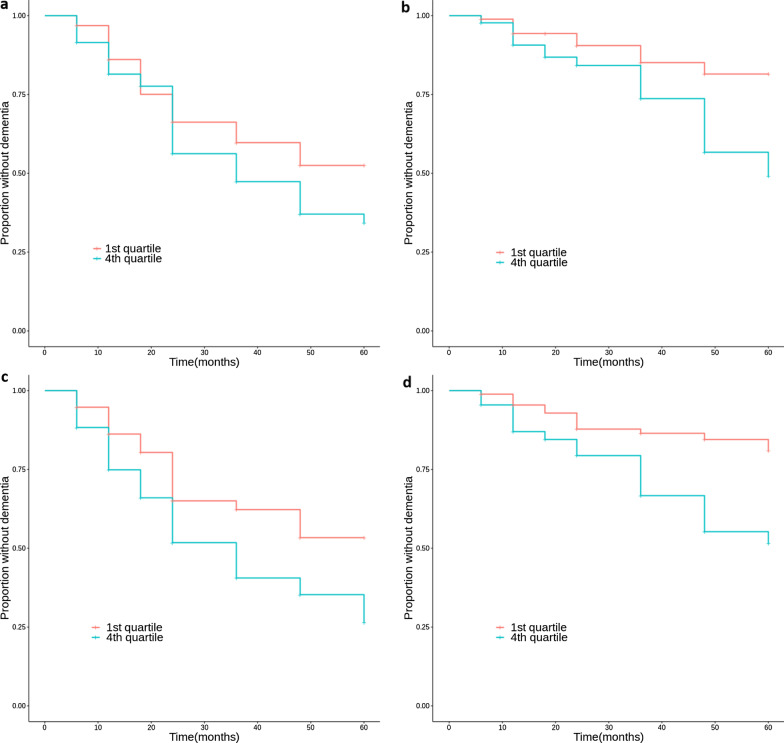

In the Cox regression analysis to assess the predictability for the conversion of MCI to AD, PRS+APOE (HR 1.468, 95% CI 1.335–1.615) and PRS−APOE (HR 1.293, 95% CI 1.157–1.445) both presented a significant association with the risk of disease progression (Table 2). PRS+APOE showed significantly increased HRs in both MCI with and without APOE ε4 alleles. In particular, the risk association in MCI with no APOE ε4 alleles was stronger (HR 1.710, 95% CI 1.244–2.351) than MCI with APOE ε4 alleles (HR 1.167, 95% CI 1.005–1.355) (Table 2). The interaction between PRS+APOE and APOE ε4 carrier status in Cox regression analysis was also significant, with a coefficient of − 0.372 (Table 3). PRS−APOE also presented stronger risk association in MCI with no APOE ε4 alleles (HR 1.429, 95% CI 1.182–1.728) than in MCI with APOE ε4 alleles (HR 1.172, 95% CI 1.020–1.346). However, the interaction between PRS−APOE and APOE ε4 carrier status was not significant, with a coefficient of − 0.174. HRs of PRS+APOE and PRS−APOE in MCI with and without APOE ε4 alleles are presented with Kaplan Meier curves (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Association of PRS, APOE ε4 status, hippocampal volume on MRI, and amyloid PET positivity with disease progression to dementia according to z-scores in all MCI participants, MCI with APOE ε4, and MCI without APOE ε4

| HR (95% CI), P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| All MCI (n = 732) |

MCI with APOE ε4 (n = 378) |

MCI without APOE ε4 (n = 353) |

|

| PRS+APOE |

1.468 (1.335–1.615) 2.30 × 10–15 |

1.167 (1.005–1.355) 4.16 × 10–2 |

1.710 (1.244–2.351) 9.30 × 10–4 |

| PRS−APOE |

1.293 (1.157–1.445) 5.19 × 10–6 |

1.172 (1.020–1.346) 2.47 × 10–2 |

1.429 (1.182–1.728) 2.19 × 10–4 |

| APOE ε4 carrier status |

2.678 (2.066–3.470) 9.70 × 10–14† |

NA | NA |

| Hippocampal volume on MRI |

0.563 (0.502–0.632) < 2.00 × 10–16* |

0.538 (0.461–0.628) 3.55 × 10–15† |

0.536 (0.435–0.660) 4.44 × 10–9†† |

| Amyloid PET positivity |

7.449 (4.199–13.215) 6.61 × 10–12§ |

5.011 (1.966–12.764) 7.31 × 10–4∥ |

6.500 (2.914–14.495) 4.77 × 10–6¶ |

PRS+APOE: PRS including SNPs within the 1 Mb-region surrounding the APOE gene; PRS−APOE: PRS excluding SNPs within the 1 Mb-region surrounding the APOE gene

Cox regression analysis of all variables were adjusted with age and sex, and additionally with MRI field strength in hippocampal volume analysis

Data unavailable for * 3 subjects, † 1 subject, †† 2 subjects, § 343 subjects, ∥191 subjects, and ¶ 152 subjects

Table 3.

Cox regression analysis of interaction between PRS and APOE ε4 carrier status in association with disease progression from MCI to AD

| Coefficient | Standard error | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.034 | 0.009 | 1.94 × 10–4 |

| Female | 0.116 | 0.127 | 3.57 × 10–1 |

| PRS+APOE | 0.531 | 0.162 | 1.10 × 10–3 |

| APOE ε4 carrier status | 0.681 | 0.176 | 1.14 × 10–4 |

| PRS+APOE × APOE ε4 carrier status | − 0.372 | 0.179 | 3.78 × 10–2 |

PRS+APOE: PRS including SNPs within the 1 Mb-region surrounding the APOE gene

Fig. 1.

Kaplan Meier curves for disease progression from mild cognitive impairment to dementia of the lowest PRS group (1st quartile) and the highest PRS group (4th quartile). PRS+APOE in MCI with (a) and without APOE ε4 (b). PRS−APOE in MCI with APOE ε4 (c) and without APOE ε4 (d) are presented

Next, we performed Cox regression analysis to assess the predictability of AD-related biomarkers such as amyloid PET positivity and hippocampal volume on MRI, separately, for the conversion of MCI to AD, using imaging biomarkers as independent variables. The MCI participants carrying the APOE ε4 allele showed increased HR (2.678, 95% CI 2.066–3.470) compared to the MCI not carrying the APOE ε4 allele. The hippocampal volume on MRI was related to a decreased risk of disease progression (HR 0.563, 95% CI 0.502–0.632), and the amyloid PET positivity predicted disease progression with HR of 7.449 (95% CI 4.199–13.215) (Table 2).

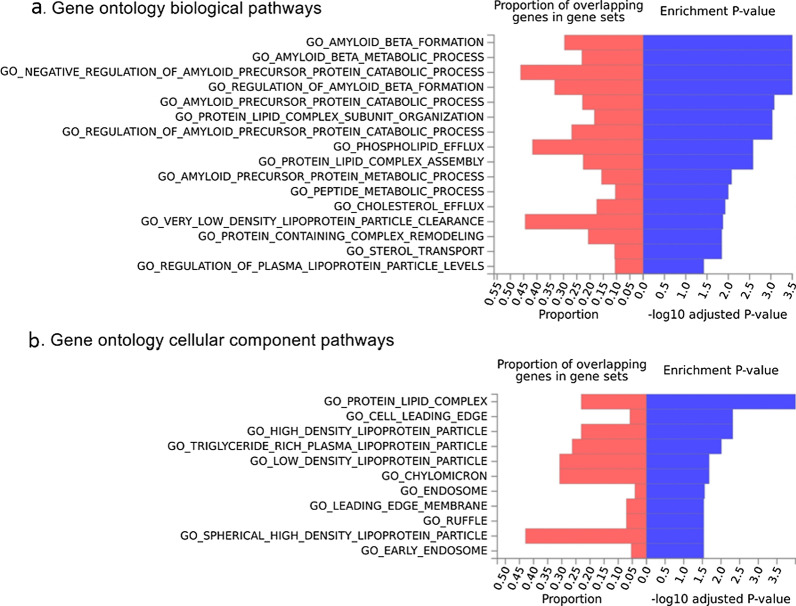

For gene mapping, all SNPs (n = 4967) that had r2 ≥ 0.6 with one of the independent SNPs (r2 < 0.05, n = 204) used to calculate PRS at a selection threshold of P < 1 × 10–5, were mapped on 424 genes. Among the 4967 SNPs, 3551 SNPs were used for positional mapping of 316 genes, 2898 SNPs for eQTL mapping of 264 genes, and 73 SNPs for chromatin interaction mapping of 19 genes. Among a total of 424 mapped genes, 133 genes were mapped by multiple independent significant SNPs. The mapped genes are listed in Additional file 2: Table S3. Gene set enrichment analysis yielded 16 significant GO BP pathways, 11 significant GO CC pathways, and no significant GO MF pathways (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Gene ontology biological pathways and cellular component pathways

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that PRS+APOE was significantly associated with an increased risk of progression to dementia in MCI. PRS−APOE was also related to an increased risk of progression, albeit less pronounced. Notably, the association of PRS with progression risk was stronger in APOE ε4 non-carriers than in APOE ε4 carriers in MCI, showing a significant interaction between PRS+APOE and APOE ε4 carrier status on the conversion of MCI to dementia.

A previous study showed that the higher PRS, excluding chromosome 19 SNPs to avoid the APOE effect, could predict clinical progression to MCI/AD from non-demented status, with unstandardized β value of 0.49 in logistic regression analysis. PRS including chromosome 19 has also shown similar results with unstandardized β value of 0.43 [5]. In another study, while PRS with APOE is significantly associated with the progression risk from MCI to AD with HR of 1.59 (95% CI 1.31–1.78), PRS without APOE could not predict the progression with HR of 1.03 (95% CI 0.79–1.34) [6]. In the current study, we found comparable HRs for PRS with and without APOE and additionally confirmed different predictability between APOE ε4 carriers and non-carriers of the MCI participants.

Here, PRS−APOE showed less prominent association with disease progression risk than PRS+APOE, which suggests that APOE is the strongest known risk gene for LOAD and affects the predictability of PRS. The APOE ε4 carriers show a three- to four-fold increase of risk of AD development compared to the APOE ε4 non-carriers [34]. In addition to the effect of APOE alone, other AD-associated genes can interact with APOE to affect the disease course. A previous study has revealed that the SNP variants at FYN and RNF219 loci are associated with decreased LOAD age-of-onset in APOE ε4 non-carriers but not in APOE ε4 carriers [35]. The RNF219 variant is also related with the beta-amyloid (Aß) load in APOE ε4 non-carriers, but not in APOE ε4 carriers [35]. Alleles of the CETP gene could alter AD risk in an APOE-dependent manner [36]. In a meta-analysis, CLU is associated with AD only in APOE ε4 non-carriers and PICALM only in APOE ε4 carriers [37]. The SNPs used for PRS calculation in our study also included SNPs of CLU and PICALM, and the integrated effect of interaction between genes containing SNPs of PRS and APOE could manifest as a stronger progression risk in APOE ε4 non-carriers of our MCI cohort.

How the AD-associated genes impact AD pathology is not completely elusive, although the exact mechanism of the well-known APOE ε4 allele for amyloid clearance and aggregation and its association with AD-associated genes remain unclear [38]. Recent studies have found that the APOE ε4 allele is associated with Aß elevation and accumulation on PET, whereas PRS is more associated with faster cognitive decline in amyloid-positive status [39, 40]. This implies that APOE ε4 contributes to the initiation of amyloidopathy in an early stage, while other genetic variants are involved in disease progression. In addition, pathway analysis has shown that a large proportion of the AD-related pathways is associated with the APOE region. Furthermore, pathways such as the protein-lipid complex subunit organization and protein-lipid complex assembly have also been found to be involved in the AD risk independent of the APOE region [24, 39]. Again, these pathways were confirmed in our GO BP results. Another study investigating the contribution of five pathway-specific PRSs to AD risk has shown that the most involved pathway is Aß metabolism (29.6%) when the analysis included APOE variants, and immune response (45.5%) when the analysis excluded APOE variants [41].

However, the pathways related to APOE and PRS cannot be distinguished clearly, and a complex interaction of Aß, tau metabolism, cholesterol/lipid metabolism [42, 43], endosomal–lysosomal processing [44], neuroinflammation [45, 46], cerebrovascular integrity [47, 48], and susceptibility to infectious agents [49] should be considered. We also observed that the genes corresponding to the SNPs used for the PRS calculation in this study were involved in diverse pathogenesis of AD, such as cholesterol metabolism (APOE, CLU, ABCA7), tau toxicity (BIN1, CD2AP, FERMT2, CASS4, PTK2B), immune response (CR1, CD33, MS4A, TREM2), and endocytosis (BIN1, PICALM, CD2AP, SPHA1, SORL1) [3, 50].

Another finding in our study was that PRS+APOE and PRS−APOE had relatively lower predictability for the conversion of MCI to AD, compared to MRI and amyloid PET biomarkers, which implies a limitation of PRS use in disease stages when abnormalities on MRI and amyloid PET biomarkers have fully developed. However, PRS as a non-modifiable risk factor given at birth could offer early prediction, independent of the disease stage.

Limitations and strengths

There are a few limitations in the current study. The sample size was small, so replication in an independent cohort would be desirable. With a longer follow-up period, some stable MCI participants might convert to AD. There are several challenges for PRS utility in clinical practice. Although the predictive utility of PRS has been validated in clinically well-defined and biomarker-confirmed cohorts, the PRS risk estimation in clinical populations from the community could be affected by variables such as ethnicity, environmental factors, and mixed pathologies. In addition, PRS as an additive indicator should be interpreted with caution to avoid ethical issues such as genetic determinism [51, 52]. Furthermore, bioinformatics tools for fast and simple data processing are needed for clinical PRS application in patients. With these issues being solved, PRS would be a useful biomarker based on the important genetic contributions in diseases and improve the cost and accessibility.

PRS is also an emerging tool for genetic risk estimation in AD. The predictability of PRS for disease progression has been reported with inconsistency depending on the inclusion or exclusion of APOE ε4 [4]. In this study, we not only investigated the predictability of PRS with and without APOE ε4, but also analyzed, for the first time, the interaction between PRS and APOE ε4. In addition, we present, for the first time, a comparison of the predictability of PRS for disease progression, with conventional imaging AD biomarkers including PET-based amyloid deposition and MRI-based brain atrophy.

Conclusions

In summary, we demonstrated that PRS could predict conversion of MCI to dementia, showing a significant interaction between PRS and APOE ε4 carrier status, particularly stronger association in APOE ε4 non-carriers than in carriers. These results support that PRS can predict disease progression in MCI patients with no APOE ε4 allele, which has so far been the primary genetic risk factor used for clinical assessment. Furthermore, individualized risk estimation with PRS may allow timely interventions such as life style modification for disease prevention, which may reduce the dementia risk despite high genetic risk [53].

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Fig. S1. The multidimensional scaling analysis for study population selection. Table S1. Number of SNPs for PRS calculation depending on GWAS association P-value thresholds. Table S2. Predictability of PRS for progression from mild cognitive impairment to dementia depending on GWAS P-value thresholds.

Additional file 2: Table S3. List of mapped genes.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Prof. An, So-Yeon (Medical Research Collaborating Center in Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Korea) for review of the statistical analysis. Additionally, this work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea grant funded by the Korean government (Ministry of Science and ICT) (No. 2020R1C1C1013718). Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Cogstate; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California.

Additional support for data analysis was provided by NLM R01 LM012535, NIA R03 AG054936, NIA R01 AG19771, NIA R01 AG068193, NIA P30 AG10133, NLM R01 LM011360, NIA U01 AG068057.

Data used in preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at: http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf.

Abbreviations

- Aß

Beta-amyloid

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- ADNI

Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative

- BP

Biological processes

- CC

Cellular components

- CDR-SB

Clinical dementia rating sum of boxes

- CI

Confidence interval

- eQTL

Expression quantitative trait loci

- GO

Gene ontology

- GWAS

Genome-wide association studies

- HR

Hazard ratio

- LOAD

Late-onset Alzheimer’s disease

- MAF

Minor allele frequency

- MCI

Mild cognitive impairment

- MF

Molecular functions

- MMSE

Mini-Mental State Examination

- PRS

Polygenic risk score

- QC

Quality control

- SNP

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- SUVR

Standardized uptake value ratio

Authors' contributions

JMP: Analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript draft. YHP: Study design, analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript revision. SYK: Manuscript revision. KJL: Analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript revision. AJS: Interpretation of data, manuscript revision. KN: Study design, analysis and interpretation of data, manuscript revision.

Funding

Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12–2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: AbbVie, Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; CereSpir, Inc.; Cogstate; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Lumosity; Lundbeck; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Takeda Pharmaceutical Company; and Transition Therapeutics. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute at the University of Southern California. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California.

Availability of data and materials

All demographic, imaging, and genetic data in this study are publicly available and can be downloaded from the ADNI database (adni.loni.usc.edu).

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study procedures were approved by the institutional review board of all participating centres (http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf), and written informed consent was obtained from all participants or authorized representatives.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Young Ho Park, Email: kumimesy@snubh.org.

Kwangsik Nho, Email: knho@iu.edu.

References

- 1.Gatz M, Reynolds CA, Fratiglioni L, Johansson B, Mortimer JA, Berg S, et al. Role of genes and environments for explaining Alzheimer disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:168–174. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jansen IE, Savage JE, Watanabe K, Bryois J, Williams DM, Steinberg S, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies new loci and functional pathways influencing Alzheimer’s disease risk. Nat Genet. 2019;51:404–413. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0311-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kunkle BW, Grenier-Boley B, Sims R, Bis JC, Damotte V, Naj AC, et al. Genetic meta-analysis of diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease identifies new risk loci and implicates Aβ, tau, immunity and lipid processing. Nat Genet. 2019;51:414–430. doi: 10.1038/s41588-019-0358-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison JR, Mistry S, Muskett N, Escott-Price V. From polygenic scores to precision medicine in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review. J Alzheimer’s Dis. 2020;74:1271–1283. doi: 10.3233/JAD-191233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mormino EC, Sperling RA, Holmes AJ, Buckner RL, De Jager PL, Smoller JW, et al. Polygenic risk of Alzheimer disease is associated with early- and late-life processes. Neurology. 2016;87:481–488. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams HHH, De Bruijn RFAG, Hofman A, Uitterlinden AG, van Duijn CM, Vernooij MW, et al. Genetic risk of neurodegenerative diseases is associated with mild cognitive impairment and conversion to dementia. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:1277–1285. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lacour A, Espinosa A, Louwersheimer E, Heilmann S, Hernández I, Wolfsgruber S, et al. Genome-wide significant risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease: role in progression to dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease among subjects with mild cognitive impairment. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22:153–160. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carrasquillo MM, Crook JE, Pedraza O, Thomas CS, Pankratz VS, Allen M, et al. Late-onset Alzheimer’s risk variants in memory decline, incident mild cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.07.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aisen PS, Petersen RC, Donohue M, Weiner MW. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative 2 Clinical Core: progress and plans. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2015;11:734–739. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saykin AJ, Shen L, Yao X, Kim S, Nho K, Risacher SL, et al. Genetic studies of quantitative MCI and AD phenotypes in ADNI: Progress, opportunities, and plans. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:792–814. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furney SJ, Simmons A, Breen G, Pedroso I, Lunnon K, Proitsi P, et al. Genome-wide association with MRI atrophy measures as a quantitative trait locus for Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16:1130–1138. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee Y, Han S, Kim D, Kim D, Horgousluoglu E, Risacher SL, et al. Genetic variation affecting exon skipping contributes to brain structural atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease. AMIA Jt Summits Transl Sci Proc. 2018;2017:124–131. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Price AL, Patterson NJ, Plenge RM, Weinblatt ME, Shadick NA, Reich D. Principal components analysis corrects for stratification in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet. 2006;38:904–909. doi: 10.1038/ng1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thorisson GA, Smith AV, Krishnan L, Stein LD. The international HapMap project web site. Genome Res. 2005;15:1592–1593. doi: 10.1101/gr.4413105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Y, Willer CJ, Ding J, Scheet P, Abecasis GR. MaCH: Using sequence and genotype data to estimate haplotypes and unobserved genotypes. Genet Epidemiol. 2010;34:816–834. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCarthy S, Das S, Kretzschmar W, Delaneau O, Wood AR, Teumer A, et al. A reference panel of 64,976 haplotypes for genotype imputation. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1279–1283. doi: 10.1038/ng.3643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park YH, Hodges A, Simmons A, Lovestone S, Weiner MW, Kim S, et al. Association of blood-based transcriptional risk scores with biomarkers for Alzheimer disease. Neurol Genet. 2020;6:e517. doi: 10.1212/NXG.0000000000000517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jack CR, Jr, Bernstein AMA, Borowski ABJ, Gunter JL, Fox NC, Thompson PM, et al. Update on the MRI core of the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6:212–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jagust WJ, Landau SM, Koeppe RA, Reiman EM, Chen K, Mathis CA, et al. The Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative 2 PET Core: 2015. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:757–771. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Risacher SL, Kim S, Nho K, Foroud T, Shen L, Petersen RC, et al. APOE effect on Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers in older adults with significant memory concern. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:1417–1429. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fleisher AS, Chen K, Liu X, Roontiva A, Thiyyagura P, Ayutyanont N, et al. Using positron emission tomography and florbetapir F18 to image cortical amyloid in patients with mild cognitive impairment or dementia due to Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(11):1404–1411. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Euesden J, Lewis CM, O’Reilly PF. PRSice: Polygenic Risk Score software. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:1466–1468. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, Garrison EP, Kang HM, Korbel JO, et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526:68–74. doi: 10.1038/nature15393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Watanabe K, Taskesen E, Van Bochoven A, Posthuma D. Functional mapping and annotation of genetic associations with FUMA. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41467-016-0009-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kerimov N, Hayhurst JD, Manning JR, Walter P, Kolberg L, Peikova K, et al. eQTL catalogue: a compendium of uniformly processed human gene expression and splicing QTLs. bioRxiv. 2020; preprint: not peer reviewed. 10.1101/2020.01.29.924266.

- 27.Westra HJ, Peters MJ, Esko T, Yaghootkar H, Schurmann C, Kettunen J, et al. Systematic identification of trans eQTLs as putative drivers of known disease associations. Nat Genet. 2013;45:1238–1243. doi: 10.1038/ng.2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhernakova DV, Deelen P, Vermaat M, van Iterson M, van Galen M, Arindrarto W, et al. Identification of context-dependent expression quantitative trait loci in whole blood. Nat Genet. 2017;49:139–145. doi: 10.1038/ng.3737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramasamy A, Trabzuni D, Guelfi S, Varghese V, Smith C, Walker R, et al. Genetic variability in the regulation of gene expression in ten regions of the human brain. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:1418–1428. doi: 10.1038/nn.3801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aguet F, Barbeira AN, Bonazzola R, Gabriel S, Getz G, Graubert A, et al. The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues The Genotype Tissue Expression Consortium. Science. 2020;369(6509):1318–1330. doi: 10.1126/science.aaz1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmitt AD, Hu M, Jung I, Xu Z, Qiu Y, Tan CL, et al. A compendium of chromatin contact maps reveals spatially active regions in the human genome. Cell Rep. 2016;17:2042–2059. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.10.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA, Botstein D, Butler H, Cherry JM, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. The Gene Ontology Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;25:25–29. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.The Gene Ontology Consortium The Gene Ontology Resource: 20 years and still GOing strong. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D330–D338. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamazaki Y, Zhao N, Caulfield TR, Liu CC, Bu G. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: pathobiology and targeting strategies. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15:501–518. doi: 10.1038/s41582-019-0228-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rhinn H, Fujita R, Qiang L, Cheng R, Lee JH, Abeliovich A. Integrative genomics identifies APOE ε4 effectors in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2013;500:45–50. doi: 10.1038/nature12415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murphy EA, Roddey JC, Mcevoy LK, Holland D, Hagler DJ, Jr, Dale AM, et al. CETP polymorphisms associate with brain atrophy rate, and Alzheimer’s disease risk in an APOE-dependent manner. Brain Imaging Behav. 2015;6:16–26. doi: 10.1007/s11682-011-9137-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jun G, Naj AC, Beecham GW, Wang LS, Buros J, Gallins PJ, et al. Meta-analysis confirms CR1, CLU, and PICALM as Alzheimer disease risk loci and reveals interactions with APOE genotypes. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:1473–1484. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Belloy ME, Napolioni V, Greicius MD. A quarter century of APOE and Alzheimer’s disease: progress to date and the path forward. Neuron. 2019;101:820–838. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.01.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leonenko G, Shoai M, Bellou E, Sims R, Williams J, Hardy J, et al. Genetic risk for Alzheimer disease is distinct from genetic risk for amyloid deposition. Ann Neurol. 2019;86:427–435. doi: 10.1002/ana.25530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ge T, Sabuncu MR, Smoller JW, Sperling RA, Mormino EC. Dissociable influences of APOE ε4 and polygenic risk of AD dementia on amyloid and cognition. Neurology. 2018;90:e1605–e1612. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000005415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tesi N, van der Lee SJ, Hulsman M, Jansen IE, Stringa N, van Schoor NM, et al. Immune response and endocytosis pathways are associated with the resilience against Alzheimer’s disease. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10:332. doi: 10.1038/s41398-020-01018-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hamanaka H, Katoh-Fukui Y, Suzuki K, Kobayashi M, Suzuki R, Motegi Y, et al. Altered cholesterol metabolism in human apolipoprotein E4 knock-in mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:353–361. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.3.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gong JS, Morita SY, Kobayashi M, Handa T, Fujita SC, Yanagisawa K, et al. Novel action of apolipoprotein e (ApoE): ApoE isoform specifically inhibits lipid-particle-mediated cholesterol release from neurons. Mol Neurodegener. 2007;2:9. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-2-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nuriel T, Peng KY, Ashok A, Dillman AA, Figueroa HY, Apuzzo J, et al. The endosomal–lysosomal pathway is dysregulated by APOE4 expression in vivo. Front Neurosci. 2017;11:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2017.00702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rodriguez GA, Tai LM, LaDu MJ, Rebeck GW. Human APOE4 increases microglia reactivity at Aβ plaques in a mouse model of Aβ deposition. J Neuroinflammation. 2014;11:111. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-11-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shi Y, Yamada K, Liddelow SA, Smith ST, Zhao L, Luo W, et al. ApoE4 markedly exacerbates tau-mediated neurodegeneration in a mouse model of tauopathy. Nature. 2017;549:523–527. doi: 10.1038/nature24016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tai LM, Thomas R, Marottoli FM, Koster KP, Kanekiyo T, Morris AW, et al. The role of APOE in cerebrovascular dysfunction. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;176:139–148. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1547-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Montagne A, Nation DA, Sagare AP, Barisano G, Sweeney MD, Chakhoyan A, et al. APOE4 leads to blood–brain barrier dysfunction predicting cognitive decline. Nature. 2020;581:71–76. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2247-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Linard M, Letenneur L, Garrigue I, Doize A, Dartigues JF, Helmer C. Interaction between APOE4 and herpes simplex virus type 1 in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2020;16:200–208. doi: 10.1002/alz.12008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karch CM, Goate AM. Alzheimer’s disease risk genes and mechanisms of disease pathogenesis. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;77:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lewis CM, Vassos E. Polygenic risk scores: from research tools to clinical instruments. Genome Med. 2020;12(1):44. doi: 10.1186/s13073-020-00742-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Torkamani A, Wineinger NE, Topol EJ. The personal and clinical utility of polygenic risk scores. Nat Rev Genet. 2018;19(9):581–590. doi: 10.1038/s41576-018-0018-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lourida I, Hannon E, Littlejohns TJ, Langa KM, Hyppönen E, Kuzma E, et al. Association of lifestyle and genetic risk with incidence of dementia. JAMA. 2019;322:430–437. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.9879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Fig. S1. The multidimensional scaling analysis for study population selection. Table S1. Number of SNPs for PRS calculation depending on GWAS association P-value thresholds. Table S2. Predictability of PRS for progression from mild cognitive impairment to dementia depending on GWAS P-value thresholds.

Additional file 2: Table S3. List of mapped genes.

Data Availability Statement

All demographic, imaging, and genetic data in this study are publicly available and can be downloaded from the ADNI database (adni.loni.usc.edu).