Abstract

Background

Human insulin was introduced for the routine treatment of diabetes mellitus in the early 1980s without adequate comparison of efficacy to animal insulin preparations. First reports of altered hypoglycaemia awareness after transfer to human insulin made physicians and especially patients uncertain about potential adverse effects of human insulin.

Objectives

To assess the effects of different insulin species by evaluating their efficacy (in particular glycaemic control) and adverse effects profile (mainly hypoglycaemia).

Search methods

A highly sensitive search for randomised controlled trials combined with key terms for identifying studies on human versus animal insulin was performed using The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE and EMBASE. We also searched reference lists and databases of ongoing trials.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled clinical trials with diabetic patients of all ages that compared human to animal (for the most part purified porcine) insulin. Trial duration had to be at least one month in order to achieve reliable results on the main outcome parameter glycated haemoglobin.

Data collection and analysis

Trial selection as well as evaluation of study quality was performed by two independent reviewers. The quality of reporting of each trial was assessed according to a modification of the quality criteria as specified by Schulz and by Jadad.

Main results

Altogether 2156 participants took part in the 45 randomised controlled studies that were discovered through extensive search efforts. Though many studies had a randomised, double‐blind design, most studies were of poor methodological quality. Purified porcine and semi‐synthetic insulin were most often investigated. No significant differences in metabolic control or hypoglycaemic episodes between various insulin species could be elucidated. Insulin dose and insulin antibodies did not show relevant dissimilarities.

Authors' conclusions

A comparison of the effects of human and animal insulin as well as of the adverse reaction profile did not show clinically relevant differences. Many patient‐oriented outcomes like health‐related quality of life or diabetes complications and mortality were never investigated in high‐quality randomised clinical trials. The story of the introduction of human insulin might be repeated by contemporary launching campaigns to introduce pharmaceutical and technological innovations that are not backed up by sufficient proof of their advantages and safety.

Keywords: Animals, Humans, Diabetes Mellitus, Diabetes Mellitus/drug therapy, Hypoglycemic Agents, Hypoglycemic Agents/adverse effects, Hypoglycemic Agents/therapeutic use, Insulin, Insulin/adverse effects, Insulin/therapeutic use, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Species Specificity

Plain language summary

'Human' insulin versus animal insulin in people with diabetes mellitus

Human insulin has become the insulin of choice for newly diagnosed patients with diabetes mellitus. Insulin companies are eventually not going to maintain different species formulations for a declining proportion of the population with diabetes using animal insulin. Concerns exist about increased hypoglycaemia following transfer to human insulin and availability of animal insulin especially in developing countries. In our systematic review we could not identify substantial differences in the safety and efficacy between insulin species. Many important patient‐oriented outcomes like health‐related quality of life and effects on diabetic complications and mortality were never investigated. Human insulin was introduced into the market without scientific proof of advantage over existing purified animal insulins, especially porcine insulin.

Background

Description of the condition

Diabetes mellitus is a metabolic disorder resulting from a defect in insulin secretion, insulin action, or both. As a result there is a disturbance of carbohydrate, fat and protein metabolism. Long‐term complications of diabetes mellitus include retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy and increased risk of cardiovascular disease. For a detailed overview of diabetes mellitus, please see under 'Additional information' in the information on the Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders Group in The Cochrane Library (see 'About the Cochrane Collaboration', 'Collaborative Review Groups'). For an explanation of methodological terms, see the main Glossary in The Cochrane Library.

Description of the intervention

Human insulin was introduced for the routine treatment of diabetes in the early 1980s. A theoretical advantage of human insulin was thought to be its absence or low immunogenicity in diabetic patients, although the importance of insulin antibodies from a clinical point of view was never fully understood, apart from rare cases of insulin resistance and insulin allergy. Structurally, porcine insulin differs from human insulin by one amino acid (at the carboxy‐terminal alanine, position 30 of the B‐chain) and bovine insulin differs from human insulin at three positions (B30, A8, and A10) (Brogden 1987; Chien 1996; Heinemann 1993). Like animal insulin, human insulin manufactured by several different methods is available in various formulations (for example regular, intermediate and long‐acting). Older sources of human insulin were of limited availability, requiring extraction of insulin from human cadaver pancreas, or complete chemical synthesis which involved 200 separate reaction steps. More advanced methods to develop ('biosynthetic') human insulin use recombinant DNA technology with baker's yeast or the bacterium Escherichia coli as the host cell or substitute enzymatically B30 alanine of porcine insulin with threonine to manufacture ('semisynthetic') human insulin in a highly purified (monocomponent) form (Chien 1996). At the time of introduction of human insulin, marketing strategies suggested that the lower immunogenicity of human insulin and the anticipated decline in antibody titres would offer a clinical advantage for insulin‐treated patients. Of the animal insulins, experts believe bovine insulin is generally more immunogenic than porcine insulin. The purity of an insulin preparation influences the quantity of insulin antibodies formed in diabetic patients (Gregory 1993). Thus, highly purified monocomponent porcine or bovine insulin induces fewer insulin antibodies than the insulin of the same formulation crystallized several times. During the 1970s, problems at injection sides such as allergy and lipoatrophy appeared to decrease concomitantly with the increasing purity of insulin preparations. It seemed logical that human insulin, which is identical in chemical structure to pancreatic insulin in man, should offer additional advantages in diabetic patients, though this was always disputed (Armitage 1988; Schernthaner 1993; VanHaeften 1989). The early clinical trials comparing human and animal insulins reported no significant differences in metabolic control or in the frequencies of symptomatic hypoglycaemia associated with each insulin species, and symptom profiles in diabetic patients were very similar. Subsequent clinical reports based on retrospective clinical surveys claimed that transfer to human insulin was associated with loss of the warning symptoms of hypoglycaemia, and that this resulted in higher frequencies of severe hypoglycaemia. Although many studies have refuted an increased incidence of hypoglycaemia (Berger 1987; Cryer 1993; Everett 1994; Patrick 1993) associated with human insulin, reports by Swiss researchers (Berger 1989 (Add.); Egger 1992; Teuscher 1987; Teuscher 1992) initiated considerable concern in doctors and patients (Hirst 1998) taking human insulin. Moreover, there was a growing concern that developing countries would not be able to afford the higher expenses for human insulin. Due to the fact that in recent years major insulin producing companies ceased to manufacture animal insulin, there is a real threat of shortage of animal insulin especially in developing countries.

Why it is important to do this review

A systematic review addressed the problem of the putative differences in hypoglycaemia symptoms between human and animal insulin species, taking into account studies of various designs (randomised and controlled clinical trials, cohort and case‐control studies, case reports and case series (Airey 2000). The review concluded that the evidence did not support the contention that treatment with human insulin per se affects the frequency, severity or symptoms of hypoglycaemia. However, the main focus of that review was to investigate the main adverse effect of hypoglycaemia and not efficacy, an approach which was criticized (Hirst 2001). Moreover, the reviewers' search strategy missed several trials exploring various risks and benefits of human versus animal insulin at the same time. We would therefore like to add valuable information for patients and health‐care providers by enlarging the scope of our review to investigate all data on patient‐relevant outcomes which can be obtained from randomised controlled clinical trials pertinent to the review objectives.

An earlier version of this systematic review was published in the Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics ‐ Clinics of North America (Richter 2002).

Objectives

To assess the effects 'human' versus animal insulin.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled clinical trials that studied the effects of human versus animal insulin.

Types of participants

Trial participants of all ages with an established diagnosis of diabetes mellitus.

Types of interventions

We were interested in comparisons of any type and preparation of human insulin treatment with any type and preparation of animal insulin therapy. Trial duration had to be at least one month in order to achieve a minimal acceptable stabilisation period for the main outcome parameter glycated haemoglobin which reflects glucose fluctuations over the last one to three months.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

glycaemic control (glycosylated haemoglobin);

frequency, severity and symptoms of hypoglycaemia;

diabetic complications (for example diabetic retinopathy, diabetic nephropathy, diabetic neuropathy).

Secondary outcomes

fasting plasma glucose;

any other adverse effect apart from hypoglycaemia;

diabetes‐related mortality (for example death from myocardial infarction, stroke, peripheral vascular disease) and total mortality;

health‐related quality of life (ideally, measured using a validated instrument) and other indicators of well‐being;

compliance;

costs;

socio‐economic effects (for example hospital stay, sick leave days, emergency room admissions).

Covariates, effect modifiers and confounders

We planned to investigate the influence of the following covariates on the main outcome parameters, provided data could be extracted from publications.

compliance,

disease severity,

insulin antibody status at baseline.

Timing of outcome measurement

We had planned to assess outcomes in the short (one up to three months), medium (greater than three months up to one year) and long (more than one year) term.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases:

The Cochrane Library (issue 3, 2004);

MEDLINE (until 07, 2004);

EMBASE (until 07, 2004).

For detailed search strategies please see under Appendix 1.

All records from each database were imported into the bibliographic package, Reference Manager (Version 9.5, ISI ResearchSoft), checked for duplicates and merged into one core database.

We also searched the meta‐register of ongoing trials (www.controlled‐trials.com), the web site of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA ‐ www.fda.gov) and the homepage of the European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products (EMEA ‐ www.emea.eu.int).

Searching other resources

We contacted the major human insulin producing companies, Novo Nordisk and Elli Lilly, for identification of further as well as unpublished trials. If additional useful data are provided these will be incorporated in future versions of this review.

We scanned the reference lists of papers identified for further trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The title, abstract and keywords of every record retrieved were scanned independently by two reviewers (BR, GN) to determine which studies required further assessment. Articles were only rejected on initial screen if we could clearly determine from the title and abstract that the article was not a report of a randomised controlled trial, or the trial did not address human versus animal insulin treatment for people suffering from diabetes mellitus, or the trial was of less than four weeks duration. When there was any doubt regarding these criteria from scanning the titles and abstracts, the full article was retrieved for clarification. We measured inter‐observer agreement for study selection using the kappa statistic (Fleiss 1981). Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Data extraction and management

Data concerning details of study population, intervention and outcomes were extracted independently by two reviewers (BR, GN) using a standard data extraction Access (Microsoft Corporation) database specifically programmed for this review. Data on participants, interventions and outcomes, as described above, were abstracted. The data extraction database included the following items:

general information: published/unpublished, title, authors, reference/source, contact address, country, urban/rural, language of publication, year of publication, duplicate or multiple publications, sponsor, setting;

trial characteristics: design, duration of follow up, method of randomisation, allocation concealment, blinding (patients, people administering treatment, outcome assessors);

intervention(s): interventions(s) (dose, route, timing), comparison intervention(s) (dose, route, timing), co‐medication(s) (dose, route, timing), co‐morbidities (especially diabetic complications);

participants: sampling (random/convenience), exclusion criteria, total number and number in comparison groups, sex, age, baseline characteristics, diagnostic criteria, duration of diabetes, type of diabetes mellitus, similarity of groups at baseline (including any co‐morbidity), assessment of compliance, withdrawals/losses to follow‐up/drop‐outs (reasons/description), subgroups;

outcomes: outcomes specified above, any other outcomes assessed, other events, length of follow‐up, quality of reporting of outcomes;

results: for outcomes and times of assessment (including a measure of variation), if necessary converted to measures of effect specified below; intention‐to‐treat analysis.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The methodological quality of reporting of each trial was assessed independently by two reviewers (BR, GN) according to a modification of the quality criteria specified by Schulz (Schulz 1995) and by Jadad (Jadad 1996).

In particular, the following quality criteria were assessed:

minimisation of selection bias ‐ a) was the randomisation procedure adequate? b) was the allocation concealment adequate?

minimisation of performance bias ‐ were the participants and people administering the treatment blind to the intervention?

minimisation of attrition bias ‐ a) were withdrawals and drop‐outs completely described? b) was analysis by intention‐to‐treat?

minimisation of detection bias ‐ were outcome assessors blind to the intervention?

Based on these criteria, studies were subdivided into one of the following three categories: A ‐ all quality criteria met: low risk of bias. B ‐ one or more of the quality criteria only partly met: moderate risk of bias. C ‐ one or more criteria not met: high risk of bias.

Data synthesis

Data were included in a meta‐analysis if they were of sufficient quality and sufficiently similar. We expected both event (dichotomous) data and continuous data. Dichotomous data would have been expressed as relative risks. Continuous data are expressed as weighted mean differences. Due to the poor quality and clinical heterogeneity of studies we decided to only subject the parameter glycated haemoglobin to pooled analysis. Analysis has to be interpreted with caution since the measurements of glycated haemoglobin were not standardised among studies and reference ranges demonstrated distinct dissimilarities. Overall results were calculated based on the random effects model due to anticipated between trials variance and different follow‐up times. Heterogeneity was tested for using the Z score and the Chi square statistic with significance being set at P < 0.1. Possible sources of heterogeneity would have been assessed by sensitivity and subgroup analyses as described below. Small study bias was tested for using the funnel plot (Egger 1997; Sterne 2001) technique. In future updates of this review we will try to incorporate the results of crossover studies (Elbourne 2002) into meta‐analytical evaluations. For calculation of changes from baseline where standard deviations of differences were not provided in the publications (regarding the main outcome parameter glycated haemoglobin) we used the following approach: Within group changes of glycosylated haemoglobin show a close correlation, especially in studies of shorter duration (for example less than 6 months). When standard deviations at the start and end of a trial were identical, we conservatively set the standard deviation of the mean differences to this value. If standard deviations were very close but not identical we used the higher standard deviation for estimation.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to perform subgroup analyses in order to explore effect size differences as follows, when there was a significant result for one of the main outcome measures:

type of human insulin (semi‐synthetic or recombinant human insulin);

type of animal insulin (porcine or bovine insulin);

duration of intervention (short, medium, long ‐ based on data);

gender;

age (children and adolescents (up to 18 years), younger adults (greater than 18 up to 65 years), older adults (greater than 65 years)).

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analyses in order to explore the influence of the following factors on effect size:

repeating the analyses excluding any unpublished studies;

repeating the analyses taking account of study quality, as specified above;

repeating the analyses excluding any very long or large studies to establish how much they dominate the results;

repeating the analyses excluding studies using the following filters: diagnostic criteria, language of publication, source of funding (industry versus other), country.

The robustness of the results was also to be tested by repeating the analyses using different measures of effects size (risk difference, odds ratio etc.) and different statistical models (fixed and random effects models).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The initial MEDLINE search using the electronic search strategy listed above yielded 4517 studies. After scanning the studies identified and performing the other searches specified, we identified 93 studies which could not be excluded by scrutiny of the title and abstract, only. Further investigation of the full articles revealed 45 studies with one duplicate publication (see Clark 1982). Another article contained two studies with separate data in one report (Beyer 1982). All these appeared to fulfil the inclusion criteria. Inter‐observer calculation for sifting the literature revealed a substantial agreement of 95% (kappa = 0.90; 95% CI 0.78 to 1.0). Furthermore, one systematic review (Airey 2000) was found. Of these, one reference (Porta 1988) was not detected in MEDLINE but in EMBASE. On the other hand, five references (Ho 1991; Lam 1988; Lam 1989; Russo 1991; Rogala 1993) were found in MEDLINE which could not be discovered in EMBASE. Two studies, thought to be ongoing trials, were identified by searching the meta‐register of ongoing trials (www.controlled‐trials.com). According to information supplied by one of the main investigators, Dr Matthew Kiln, one study was not a randomised trial but a systematic recording of case histories. Also, the second trial was an audit of treatment satisfaction and well‐being in type 1 diabetes. Novo Nordisk supplied additional information. No unpublished studies were reported. Forty of the trials were published in peer review journals, two as an abstract (Gardiner 1988; Matyka 1995) and three in peer review journal supplements (Beyer 1982; Beyer 1983; Karam 1983). The majority of publications (82%) was written in English but we also found two trials printed in German (Beyer 1983; Sailer 1986), two in Italian (Iavicoli 1984; Porta 1988), one in Polish (Rogala 1993), two in Spanish (Gomez‐Perez 1995; Santana 1987) and one study in Portuguese (Russo 1991).

Included studies

Details of the characteristics of the included studies are shown in the table Characteristics of included studies.

Around 50% of the trials were published before 1987, approximately one third was conducted in the United Kingdom and 70% were sponsored by the manufacturers of animal and human insulins.

Twenty‐four of the 45 included randomised studies were of a parallel design, 21 had a usually two‐period‐ but sometimes a three‐ or four‐period‐crossover design. Units for allocation of the treatment were always individuals. The single centre design was the dominating setting (59%) but multi centre studies were also common (39%). All participants were ambulatory patients but some studies used in‐hospital phases for glucose profile studies or investigations of hypoglycaemia following challenges, usually at the end of the observation period. Six of the 45 included trials came from the developing world.

Participants

Altogether 2156 participants took part in the 45 randomised controlled studies that were discovered through extensive search efforts. In trials of parallel design, 747 participants versus 734 participants tested human versus mainly porcine or bovine insulin. Numbers of participants ranged from 6 to 198 with a mean of 48 individuals. Most studies examined adults, one studied pregnant diabetic women (Jovanovic 1992), and four newly diagnosed diabetic children (Greene 1983; Heding 1984; Mann 1983; Marshall 1988). Fifty‐eight per cent of crossover and parallel studies investigated type 1 diabetes patients, the female to male ratio of the whole scrutinized population was roughly balanced. The weighted mean age of participants in the parallel studies was 33.8 versus 33.7 years for human versus animal insulin, the diabetes duration 15.2 years versus 14.9 years, and the body mass index (four studies) 24.7 versus 23.3 kg/m2. Participants of crossover studies were slightly older (36.7 years) and had a diabetes of somewhat shorter duration (14.1 years). No statistically significant differences at baseline were reported in any study. One crossover study (Larsen 1984) investigated patients' preferences: 3/15 opted for porcine and 8/15 for human insulin.

Interventions

Most of the participants received animal insulin in the (purified) porcine form; nine studies investigated bovine insulin either alone or in combination with pork insulin (Clark 1982; Beyer 1983; Holman 1984; Gardiner 1988; Tindall 1988; Selam 1989; Fletcher 1990; Russo 1991; Jovanovic 1992). Eight trials evaluated the effects of recombinant DNA human insulin (Beyer 1982; Beyer 1983; Tindall 1988; Lam 1989; Colagiuri 1992; Davidson 1992; Jovanovic 1992; Gomez‐Perez 1995), all others scrutinised the effects of semi‐synthetic insulin. Trials duration ranged from one to twenty‐four months with a mean of 5.8 months, follow‐up was a mean of 8.2 months. Approximately half of the trials had a run‐in time of 0.5‐3 months in order to achieve stable metabolic conditions. Diagnostic criteria for entry into the study were specified in 50% of cases, 40% did not state how diagnosis had been established in the patients. Most studies (84%) tried to achieve a comparable insulin regimen throughout the investigation period, and treating physicians tried to achieve optimisation of therapy together with their patients by means of usually flexible insulin therapy in order to achieve metabolic targets of heterogeneously defined 'good control'.

Outcomes

All studies reported on metabolic control and insulin dosage, some on insulin antibodies and adverse effects in general, and many on hypoglycaemic episodes. None of the studies assessed diabetic complications, diabetes‐related mortality or total mortality, health‐related quality of life, costs or socio‐economic effects.

Excluded studies

Forty‐six studies were excluded upon further scrutiny. Reasons for exclusion of studies are given in the table Characteristics of excluded studies. Main reasons for exclusion were non‐randomised trial design or a study duration of less than one month.

Risk of bias in included studies

Though many studies were of a randomised, double‐blind design, most studies were of poor methodological quality ('C'). Only one study was of higher quality (Egger 1991) ('B') and described methodological issues in some detail (for example, randomisation method, flow of participants, blinding of outcome assessment). Eighty‐six per cent of the studies did not define a primary endpoint, only three studies (Karam 1983; Maran 1993; Oswald 1987) provided a power calculation. None of the crossover studies used a wash‐out period in between the two crossover phases, only three (Clark 1982; Egger 1991; George 1997) analysed data for carryover and period effects. Inclusion criteria were described in 73% and exclusion criteria in 55% of trials.

Inter‐observer calculation of key elements of study quality revealed a substantial agreement of 96% (kappa = 0.93; 95% CI 0.86 to 0.99).

Covariates, confounders and effect‐modifiers

Disease severity was rarely reported; co‐morbidities and co‐medications ‐ if mentioned at all ‐ did not differ systematically between groups. Compliance as an important effect modifier, especially for introduction of new therapeutic modalities, was not investigated. Insulin antibody status at baseline was comparable between groups, though only approximately 50% of trials used a run‐in period, thus theoretical carryover effects from pre‐trial antibodies to animal insulin could not be ruled out in many studies.

Allocation

Only five studies mentioned the method of randomisation (Berger 1989 (Add.); Egger 1991; Gunnarsson 1986; Marshall 1988; Santana 1987), although randomisation procedures were not explained in sufficient detail. One study mentioned allocation concealment (MacLeod 1995).

Blinding

Stated method of blinding was open in eight studies, single‐blinding in two, double‐blinding in 33 and triple‐blinding in one (Egger 1991). Careful inspection revealed that only 9/45 studies actually provided information of who (patient, treatment administrator or provider, outcome assessor) was blinded. None of the studies reported checking of blinding conditions in patients and health care providers. Three studies (Colagiuri 1992; George 1997; Maran 1993) scrutinised blinding conditions in patients: Four to 53 per cent of participants were correctly able to identify the sequence of insulin species in crossover trials.

Incomplete outcome data

Sixty‐nine per cent of studies reported drop‐outs in some detail. Intention‐to‐treat analysis was described in one study (Home 1984).

Other potential sources of bias

Compliance assessment

No study attempted to measure compliance in a systematic and reproducible way.

Effects of interventions

Metabolic control (parallel studies)

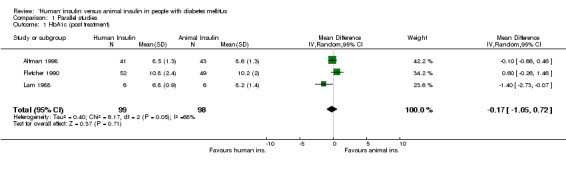

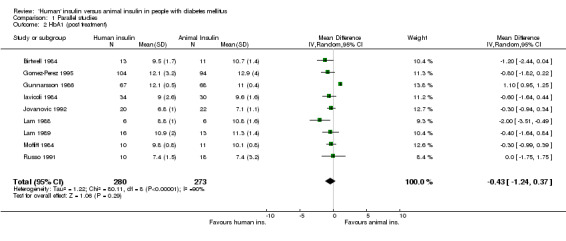

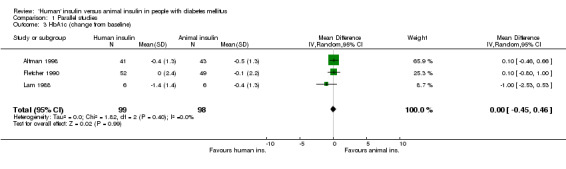

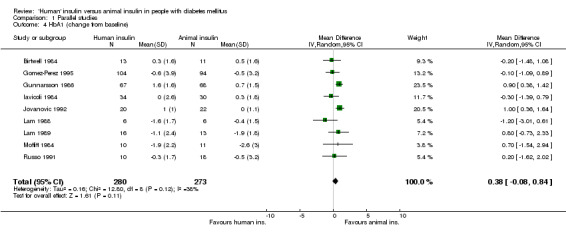

The term 'animal' insulin used in this review usually, unless otherwise indicated, refers to purified porcine insulin since the great majority of trials utilized this form of animal insulin treatment. Some trials investigated mixed regimens of purified porcine/bovine or rarely purified bovine insulin, only. Three parallel designed studies reported post treatment glycated haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) measurements. Human insulin was associated with a non‐significant mean (pooled weighted mean difference) lowering of HbA1c of 0.17% (95% CI ‐1.05 to 0.72%) compared to animal insulin. The test for heterogeneity was significant (p=0.046). An investigation of the changes from baseline revealed similar non‐significant results (0% change with a 95% CI of ‐0.45 to 0.46%, statistical hetereogeneity was not significant). Nine parallel designed studies described post treatment glycated haemoglobin A1 (HbA1) measurements. Human insulin was associated with a non/significant pooled weighted mean difference lowering of HbA1 of 0.43% (95% CI ‐1.24 to 0.37%) compared to animal insulin. The test for heterogeneity was highly significant (p<0.00001). An investigation of the changes from baseline revealed similar non‐significant results (0.38% increase with a 95% CI of ‐0.08 to 0.84%, statistical hetereogeneity was not significant). Elimination of the single study (Gomez‐Perez 1995) which investigated purified bovine vs recombinant DNA human insulin from the analysis of post treatment HbA1 results did not change the pooled effect size significantly. The remaining eight studies which examined purified porcine versus human insulin showed a non‐significant decrease of 0.39% (95% CI ‐1.23 to 0.46) after human insulin compared to porcine insulin use. The robustness of these results was furtheron investigated using different statistical models. An application of the fixed effect model revealed a significant effect in HbA1 measurements only, in favour of animal insulin. This was caused by an increased weight on one study (Gunnarsson 1986). These disparencies between the random and fixed effects model are interpreted as indicating distinct clinical heterogeneity. We conclude that there is no clear advantage of one insulin species over the other with regards to glycated haemoglobin. Unweighted means of fasting plasma glucose were 9.8 mmol/L in human insulin compared to 10.5 mmol/L in animal insulin treated patients (six studies). A funnel plot of nine studies investigating post treatment HbA1 changes indicated asymmetry, suggesting small study bias (for example publication bias). Further updates of this review shall explore if scrutiny of additional unpublished trials, which hopefully will be provided by the main manufacturers of human insulin, will present the same picture.

Metabolic control (crossover studies)

Two crossover designed studies investigated HbA1c and eight studies HbA1 measurements. Due to the pronounced heterogeneous design of the various trials (for example two‐ or three‐period‐crossover phases, potential carryover effect of HbA1(c)) data were not evaluated by means of meta‐analysis (future versions of this review might take advantage of newly developed methods for crossover analysis). Unweighted means of HbA1c were 7.4 versus 7.5% for human versus animal insulin. Unweighted means of HbA1 showed 10.8% for human as compared to 10.4% for animal insulin. Unweighted means of fasting plasma glucose were almost identical (8.6 mmol/L) in both groups.

Insulin dose, insulin antibodies (parallel and crossover studies)

Unweighted means of post treatment insulin dose showed no relevant differences between insulin species (human versus animal insulin 43 U/day versus 47 U/day). Unweighted means of changes from baseline were 0.4 and 1.5 U/day with human and animal insulins, respectively. The studies on immunogenicity of human and animal insulin were difficult to compare because of the different assays for insulin antibodies. Overall, depending on the duration of follow‐up, a decline in insulin antibodies was observed following transfer from animal to human insulin. This tended to level out in studies of six months and longer follow‐up, rarely demonstrating significant differences at the end of the trial. Beef insulin was associated with higher insulin antibody levels than pork insulin.

Adverse effects

Most studies reported no significant differences in the frequency, severity and presentation of hypoglycaemic episodes associated with the insulin preparations (unweighted means for hypoglycaemic episodes reported in 8/45 studies were 62 mild to moderate hypoglycaemic events with human insulin compared to 57 events with animal insulin). Five studies communicated unweighted means of 2.7 and 3.2 (total sum 24 and 29 incidents) severe hypoglycaemic episodes with human and animal insulins, respectively. Other adverse effects, apart from hypoglycaemic episodes, were hardly ever reported in the trials (for example allergic reactions at the injection side), only 40% of the studies provided at least some information about adverse effects.

Discussion

Summary of main results

We found 45 randomised controlled clinical trials consisting of 24 parallel group studies and 21 crossover studies with a median follow‐up of six months. A total of 2156 patients with diabetes mellitus participated in these studies. Despite heterogeneous designs, participants, and locations neither parallel nor crossover trials suggested an important difference between insulin species regarding metabolic control as measured by glycated haemoglobin, fasting plasma glucose, and insulin dose. Most studies did not detect a significant difference in antibody formation between human and porcine insulin; one report observed a significant decline in antibodies after switch from bovine to human insulin. The overall picture with regard to hypoglycaemic events does not indicate any substantial difference between insulin species.

New findings

A recently published study investigated the prevalence of severe hypoglycaemia in relation to various risk factors in type 1 and 2 diabetic patients over a period of 14 zears (Bragd 2003). Despite the more frequent use of self‐monitoring of blood glucose, the prevalence of severe hypoglycaemia increased from 17% in the cohort of n = 178 participants (1984) to 27% in the cohort of n = 178 participants (1998) (27% relative risk increase, p < 0.05). A stepwise logistic multiple regression analysis of various risk factors (hypoglycaemia unawareness, HbA1c, creatinine clearance, nocturnal events, daily monitoring of blood glucose, duration of diabetes, age, multiple insulin injection therapy including pump treatment) for severe hypoglycaemia explained less than 10% of the variance, implicating only unawareness of hypoglycaemia and HbA1c levels. A consequent letter to the editor (personal communication) drew attention to the fact that this study did not mention that during the period of investigation synthetic human insulins were introduced and the majority of patients were transferred from animal insulin. It would have been interesting, if possible, to introduce the parameter 'transfer from animal to human insulin' into the logistic regression equation to find out its influence on the prediction of severe hypoglycaemia.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The results of this review may not have an effect on the availability or non‐availability of animal insulin worldwide. Market forces dictated a change in policy before the available evidence was summarized in a systematic way. Future introductions of new therapeutic priniciples for diabetic patients should take into account that possible advantages and disadvantages have to be thoroughly investigated in high quality trials focusing on patient‐oriented outcomes.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

This review is in accordance with the findings of the systematic review of Airey et al. (Airey 2000) with respect to the absence of a differential effect on hypoglycaemia between human and animal insulin. For the first time though, this review aggregates the relative effects and adverse events of human and animal insulin, indicating that human insulin was introduced without proof of being superior to animal insulin. Moreover, studies have not assessed patient‐centred outcomes like patient satisfaction, health‐related quality of life, and diabetes‐related morbidity. Furthermore, randomised trials did not report on qualitative assessments of patients' experiences when using different insulin species.

Implications for research.

Large scale drug utilisation studies should evaluate the situation of worldwide insulin species use focusing on the developing world. These data should provide health‐politicians with sufficient backup to enter negotiations with insulin manufacturing companies.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 16 October 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2002 Review first published: Issue 3, 2002

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 31 July 2004 | New search has been performed | New studies found and included or excluded: Search strategy for identification of studies: Novo Nordisk provided studies pertinent to the review question. No further or unpublished trials were identified. Characteristics of ongoing studies: Information about two formerly identified 'ongoing' trials was provided by Dr Matthew Kiln. One study was published as an Audit Report for the Health Authority, another study was not a randomised trial but a systematic recording of case histories. Both studies were deleted from the 'ongoing studies' section. Discussion: Section added about a recently published cross‐sectional survey of severe hypoglycaemia in 1984 and 1998. July 2004: Updated search in Medline, Embase and The Cochrane Library. One detected study (Miglani 2004) was excluded. |

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Iain Chalmers of the UK Cochrane Centre and Jenny Hirst from the Insulin Dependent Diabetes Trust for constantly reminding us that this systematic review is important. We thank Dr Matt Kiln for providing information about two studies which were formerly mentionend under 'Characteristics of ongoing studies'. We thank Novo Nordisk for providing information about further as well as unpublished trials.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy

| Search terms |

| Unless otherwise stated, search terms are free text terms; MeSH = Medical subject heading (Medline medical index term); exp = exploded MeSH; the dollar sign ($) stands for any character(s); the question mark (?) = to substitute for one or no characters; tw = text word; pt = publication type; sh = MeSH; adj = adjacent. HUMAN VERSUS ANIMAL INSULIN 1. (human or synthetic* or semisynthetic* or semi synthetic*or biosynthetic* or bio synthetic* or NPH) and insuli* [in TI, AB] 2. (porc* or pork* or swine or horse or bovin* or cattle or beef or animal*) and insuli* [in TI, AB]] 3. #1 or #2 4. (transfer* or switch* or safet*) and (human and insuli*) [in TI, AB] 5. #3 or #4 6. (growth and factor) or IGF [in TI] 7. #5 not #6 This was combined with a sensitive search strategy for identifying controlled clinical trials and systematic reviews (see Cochrane Metabolic and Endocrine Disorders Review Group search strategy) |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Parallel studies.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 HbA1c (post treatment) | 3 | 197 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.17 [‐1.05, 0.72] |

| 2 HbA1 (post treatment) | 9 | 553 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.43 [‐1.24, 0.37] |

| 3 HbA1c (change from baseline) | 3 | 197 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.00 [‐0.45, 0.46] |

| 4 HbA1 (change from baseline) | 9 | 553 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.38 [‐0.08, 0.84] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Parallel studies, Outcome 1 HbA1c (post treatment).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Parallel studies, Outcome 2 HbA1 (post treatment).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Parallel studies, Outcome 3 HbA1c (change from baseline).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Parallel studies, Outcome 4 HbA1 (change from baseline).

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Altman 1998.

| Methods | Trial design: Parallel study Randomisation procedure: Unclear Allocation concealment: Data missing Blinding: Open study | |

| Participants | Country: France Setting: Multi centre Number: 41/43 human/animal insulin Type of diabetes: Type 1 Mean age [years]: 54/58 human/animal insulin Mean diabetes duration [years]: 20/21 human/animal insulin Other characteristics: Elderly patients and (partly) patients at high risk of hypoglycaemia due to long duration of diabetes | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Unclear Duration of trial [months]: 3 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]:

8.5±1.3 vs 8.6±1.3 (hum. vs anim.)

2.HbA1 [%]: 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] ‐ 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: 37±10 vs 37±13 (hum. vs anim.) 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: 23 (2) vs 25 (4) (severe) hypoglycaemic episodes (hum. vs anim.) 5 vs 5 drop‐outs (hum. vs anim.) |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Berger 1989.

| Methods | Trial design: Crossover study Randomisation procedure: Adequate Allocation concealment: Data missing Blinding: Double‐blind | |

| Participants | Country: Switzerland Setting: Single centre Number: 18/14 human/animal insulin (start) Type of diabetes: Type 1 Mean age [years]: 34/40 human/animal insulin (start) Mean diabetes duration [years]: 15/17 human/animal insulin (start) Other characteristics: Study designed to investigate hypoglycaemic experiences | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine Duration of trial [months]: 3 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: ‐ 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] 9±1.9 vs 8.6±1.5 (hum. vs anim.) 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: 38±10 vs 38±10 (hum. vs anim.) 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: 171 (17) vs 150 (10) (severe) hypoglycaemic episodes (hum. vs anim.) 6 drop‐outs (5 human ins.) | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Beyer 1982.

| Methods | Trial design: Parallel study Randomisation procedure: Data missing Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Double‐blind | |

| Participants | Country: Germany Setting: Multi centre Number: 33/33 human/animal insulin Type of diabetes: Type 1 Mean age [years]: N/A Mean diabetes duration [years]: N/A Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Recombinant DNA Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine Duration of trial [months]: 4 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: ‐ 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] ‐ 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: ‐ 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: 2 vs 0 drop‐outs (hum. vs anim. | |

| Notes | Two studies in one publication with provision of separate results | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Beyer 1983.

| Methods | Trial design: Parallel study Randomisation procedure: Data missing Allocation concealment: unclear Blinding: Double‐blind | |

| Participants | Country: Germany Setting: Multi centre Number: 66/65 human/animal insulin Type of diabetes: Type 1 and 2 Mean age [years]: 32/32 human/animal insulin Mean diabetes duration [years]: 12/14 human/animal insulin Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Recombinant DNA Type of animal insulin: Purified procine and bovine Duration of trial [months]: 12 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: ‐ 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] ‐ 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: ‐ 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: 0 drop‐outs | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Birtwell 1984.

| Methods | Trial design: Parallel study Randomisation procedure: Data missing Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Single‐blind | |

| Participants | Country: UK Setting: Multi centre Number: 13/11 human/animal insulin Type of diabetes: Typ 1 Mean age [years]: 33/35 human/animal insulin Mean diabetes duration [years]: 10/4 human/animal insulin Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine Duration of trial [months]: 6 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: 9.5±1.7 vs 10.7±1.4 (hum. vs anim.) 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] 9.3±5.6 vs 8.8±2.9 (hum. vs anim.) 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: 46±9 vs 49±9 (hum. vs anim.) 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: 1 drop‐out | |

| Notes | Interim analysis (planned study duration: 2 years) | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Clark 1982.

| Methods | Trial design: Crossover study Randomisation procedure: Data missing Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Double blind | |

| Participants | Country: UK Setting: Multi centre Number: 47 Type of diabetes: Type 1 and 2 Mean age [years]: N/A Mean diabetes duration [years]: N/A Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Recombinant DNA Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine and bovine Duration of trial [months]: 1.5 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: ‐ 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] ‐ 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: ‐ 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: 3 vs 3 drop‐outs (hum. vs anim.) | |

| Notes | Carryover effect for HbA1 observed | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Colagiuri 1992.

| Methods | Trial design: Crossover study Randomisation procedure: Data missing Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Double‐blind | |

| Participants | Country: Australia Setting: Single centre Number: 57 Type of diabetes: Type 1 and 2 Mean age [years]: 47 Mean diabetes duration [years]: 20 Other characteristics: Study designed to detect differences in hypoglycaemic episodes | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Recombinant DNA Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine Duration of trial [months]: 2 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: ‐ 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] 9.2±1.5 vs 9.3±1.5 (hum. vs anim.) 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: ‐ 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: In toto 12 drop‐outs | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Davidson 1992.

| Methods | Trial design: Crossover study Randomisation procedure: Data missing Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Double‐blind | |

| Participants | Country: USA Setting: Single centre Number: 26 Type of diabetes: Type 1 and 2 Mean age [years]: 60 Mean diabetes duration [years]: 14 Other characteristics: Group of individuals with a history of immunologic insulin resistance | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Recombinant DNA Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine and bovine Duration of trial [months]: 2 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: ‐ 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] ‐ 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: ‐ 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: In toto 5 drop‐outs | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

DeLawter 1985.

| Methods | Trial design: Crossover study Randomisation procedure: Data missing Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Double‐blind | |

| Participants | Country: USA Setting: Single centre Number: 41/42 human/animal insulin (start) Type of diabetes: Type 1 and 2 Mean age [years]: N/A Mean diabetes duration [years]: N/A Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine Duration of trial [months]: 24 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: ‐ 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] ‐ 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: ‐ 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: In toto 1 drop‐out | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Egger 1991.

| Methods | Trial design: Crossover study Randomisation procedure: Adequate Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Triple‐blind | |

| Participants | Country: Switzerland Setting: Single centre Number: 22/22 human/animal insulin (start) Type of diabetes: Type 1 Mean age [years]: 37/33 human/animal insulin (start) Mean diabetes duration [years]: 17/15 human/animal insulin (start) Other characteristics: Study designed to investigate hypoglycaemic experiences | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine Duration of trial [months]: 1.5 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: 7.5±1.1 vs 7.5±0.8 (hum. vs anim.) 2.HbA1 [%]: ‐ 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] 7.9±2.1 vs 7.7±2.3 (hum. vs anim.) 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: 43±14 vs 43±13 (hum. vs anim.) 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: 0 drop‐outs | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Fletcher 1990.

| Methods | Trial design: Parallel study Randomisation procedure: Unclear Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Double‐blind | |

| Participants | Country: UK Setting: Multi centre Number: 55/53 human/animal insulin Type of diabetes: Type 1 and 2 Mean age [years]: 35/38 human/animal insulin Mean diabetes duration [years]: 13/12 human/animal insulin Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine and bovine Duration of trial [months]: 6 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: 10.8±2.4 vs 10.2±2 (hum. vs anim.) 2.HbA1 [%]: ‐ 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] ‐ 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: 37±10 vs 37±13 (hum. vs anim.) 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: 1 vs 1 severe hypoglycaemic episode (hum. vs anim.) 3 vs 4 drop‐outs (hum. vs anim.) | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Francis 1986.

| Methods | Trial design: Crossover study Randomisation procedure: Data Missing Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Open | |

| Participants | Country: UK Setting: Single centre Number: 6 Type of diabetes: Type 1 Mean age [years]: 31 Mean diabetes duration [years]: 10 Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine Duration of trial [months]: 4 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: 11.2±0.6 vs 11.3±0.6 (hum. vs anim.) 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] 7.2±0.8 vs 12.0±1.3 (hum. vs anim.) 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: 51±2 vs 52±2 (hum. vs anim.) 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: 0 drop‐outs | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Gardiner 1988.

| Methods | Trial design: Parallel study Randomisation procedure: Data missing Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Double‐blind | |

| Participants | Country: Canada Setting: Single centre Number: 71/71 human/animal insulin Type of diabetes: Type 1 Mean age [years]: N/A Mean diabetes duration [years]: N/A Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine and bovine Duration of trial [months]: 6 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: ‐ 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] ‐ 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: ‐ 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: ‐ | |

| Notes | Split study design (patients were divided into open and double‐blind groups) Limited information in abstract only | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

George 1997.

| Methods | Trial design: Crossover study Randomisation procedure: Data missing Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Double‐blind | |

| Participants | Country: UK Setting: Single centre Number: 20 Type of diabetes: Type 1 Mean age [years]: 37 Mean diabetes duration [years]: 17 Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine Duration of trial [months]: 1 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: 9.8±0.3 vs 10.0±0.3 (hum. vs anim.) 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] ‐ 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: ‐ 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: 23 vs 25 hypoglycaemic episodes (hum. vs anim.) 0 drop‐outs | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Gomez‐Perez 1995.

| Methods | Trial design: Parallel study Randomisation procedure: Data missing Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Single‐blind | |

| Participants | Country: Mexico Setting: Multi centre Number: 104/94 human/animal insulin Type of diabetes: Type 1 and 2 Mean age [years]: 47/45 human/animal insulin Mean diabetes duration [years]: 12/11 human/animal insulin Other characteristics: Multinational study (5 countries) | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Recombinant DNA Type of animal insulin: Purified beef Duration of trial [months]: 1.5 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: 12.1±3.2 vs 12.9±4.0 (hum. vs anim.) 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] 9.4±3.4 vs 10.7±4.4 (hum. vs anim.) 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: 42±16 vs 49±22 (hum. vs anim.) 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: 20 (1) vs 12 (0) (severe) hypoglycaemic episodes (hum. vs anim.) | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Greene 1983.

| Methods | Trial design: Crossover Randomisation procedure: Data missing Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Double‐blind | |

| Participants | Country: UK Setting: Single centre Number: 8/6 human/animal insulin Type of diabetes: Type 1 diabetic children Mean age [years]: 13/14 human/animal insulin Mean diabetes duration [years]: 5/5 human/animal insulin Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine Duration of trial [months]: 3 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: 11.9±2.5 vs 11.5±3.8 (hum. vs anim.) 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] 7.8±4.9 vs 8.3±4.6 (hum. vs anim.) 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: 48±18 vs 45±18 (hum. vs anim.) 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: In toto 3 drop‐outs | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Gunnarsson 1986.

| Methods | Trial design: Parallel study Randomisation procedure: Adequate Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Double‐blind | |

| Participants | Country: Sweden Setting: Single centre Number: 13/15 human/animal insulin Type of diabetes: Type 1 Mean age [years]: 37/33 human/animal insulin Mean diabetes duration [years]: 15/14 human/animal insulin Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine Duration of trial [months]: 12 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: 12.1±0.5 vs 11.0±0.4 (hum. vs anim.) 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] ‐ 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: ‐ 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: In toto 1 drop‐out | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Heding 1984.

| Methods | Trial design: Parallel design Randomisation procedure: Data missing Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Double‐blind | |

| Participants | Country: Denmark Setting: Multi centre Number: 67/68 human/animal insulin Type of diabetes: Newly diagnosed type 1 diabetic children Mean age [years]: 37/33 human/animal insulin Mean diabetes duration [years]: 15/14 human/animal insulin Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine Duration of trial [months]: 12 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: ‐ 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] ‐ 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: ‐ 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: 44 vs 59 (hum. vs anim.) 6.Adverse effects: ‐ | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Ho 1991.

| Methods | Trial design: Parallel study Randomisation procedure: Data missing Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Double‐blinding | |

| Participants | Country: China Setting: Single centre Number: 9/7 human/animal insulin Type of diabetes: Type 2 Mean age [years]: 52/49 human/animal insulin Mean diabetes duration [years]: 9/9 human/animal insulin Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine Duration of trial [months]: 12 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: ‐ 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] ‐ 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: ‐ 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: 78 vs 100 (hum. vs anim.) 6.Adverse effects: 0 severe hypoglycaemic episodes 3 vs 1 drop‐outs (hum. vs anim.) | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Holman 1984.

| Methods | Trial design: Crossover study Randomisation procedure: Data missing Allocation concealment: Unnclear Blinding: | |

| Participants | Country: UK Setting: Single centre Number: 18 Type of diabetes: Type 1 and 2 Mean age [years]: 55/43 human/animal insulin (start) Mean diabetes duration [years]: human/animal insulin Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine and bovine Duration of trial [months]: 1.5 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: 7.3±1.1 vs 7.7±1.1 (hum. vs anim.) 2.HbA1 [%]: ‐ 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] ‐ 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: ‐ 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: 0 drop‐outs | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Home 1984.

| Methods | Trial design: Crossover study Randomisation procedure: Data missing Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Double‐blind | |

| Participants | Country: UK Setting: Multi centre Number: 87 Type of diabetes: Type 1 Mean age [years]: 34 Mean diabetes duration [years]: 13 Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine Duration of trial [months]: 4 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: 11.7±2.8 vs 11.1±2.8 (hum. vs anim.) 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] ‐ 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: 51±2 vs 51±2 (hum. vs anim.) 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: In toto 9 drop‐outs | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Iavicoli 1984.

| Methods | Trial design: Parallel study Randomisation procedure: Data missing Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Open | |

| Participants | Country: Italy Setting: Single centre Number: 34/30 human/animal insulin Type of diabetes: Type 1 Mean age [years]: 32/34 human/animal insulin Mean diabetes duration [years]: 10/11 human/animal insulin Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine Duration of trial [months]: 12 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: 9.0±2.6 vs 9.6±1.6 (hum. vs anim.) 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] ‐ 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: ‐ 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: ‐ | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Jovanovic 1992.

| Methods | Trial design: Parallel study Randomisation procedure: Data missing Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Open | |

| Participants | Country: USA Setting: Multi centre Number: 20/22 human/animal insulin Type of diabetes: Type 1 and 2 diabetic pregnant women (< 20 wks of gestation) Mean age [years]: 29/28 human/animal insulin Mean diabetes duration [years]: 13/13humann/animal insulin Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Recombinant DNA Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine and bovine insulin Duration of trial [months]: 3 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: 6.8±1.0 vs 7.1±1.1 (hum. vs anim.) 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] ‐ 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: 45±17 vs 47±25 (hum. vs anim.) 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: 0 vs 1 drop‐outs (hum. vs anim.) | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Karam 1983.

| Methods | Trial design: Parallel study Randomisation procedure: Unclear Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Double‐blind | |

| Participants | Country: USA Setting: Multi centre Number: 23/24 human/animal insulin Type of diabetes: Type 1 Mean age [years]: 32/32 human/animal insulin Mean diabetes duration [years]: N/A Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine Duration of trial [months]: 3 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: ‐ 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] ‐ 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: ‐ 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: In toto 5 drop‐outs | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Lam 1988.

| Methods | Trial design: Parallel study Randomisation procedure: Data missing Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Double‐blinding | |

| Participants | Country: China Setting: Single centre Number: 6/6 human/animal insulin Type of diabetes: Type 2 Mean age [years]: 60/59 human/animal insulin Mean diabetes duration [years]: 7/3 human/animal insulin Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine Duration of trial [months]: 3 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: 6.8±0.9 vs 8.2±1.4 (hum. vs anim.) 2.HbA1 [%]: 8.8±1.0 vs 10.8±1.6 (hum. vs anim.) 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] 9.1±3.0 vs 8.9±3.3 (hum. vs anim.) 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: 27±16 vs 27±6 (hum. vs anim.) 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: 21 vs 41 (hum. vs anim.) 6.Adverse effects: 0 severe hypoglycaemic episodes 0 drop‐outs | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Lam 1989.

| Methods | Trial design: Parallel study Randomisation procedure: Unclear Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Double‐blind | |

| Participants | Country: Taiwan Setting: Unclear Number: 16/13 human/animal insulin Type of diabetes: Tyope 3 Mean age [years]: 54/55 human/animal insulin Mean diabetes duration [years]: 9/9 human/animal insulin Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Recombinant DNA Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine Duration of trial [months]: 12 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐) 2.HbA1 [%]: 10.9±2.0 vs 11.3±1.4 (hum. vs anim.) 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] 8.8±1.1 vs 9.4±1.8 (hum. vs anim.) 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: 60±12 vs 70±14 (hum. vs anim.) 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: 52 vs 52 (hum. vs anim.) 6.Adverse effects: 0 drop‐outs | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Larkins 1986.

| Methods | Trial design: Parallel study Randomisation procedure: Data missing Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Double‐blind | |

| Participants | Country: Australia Setting: Single centre Number: 10/10 human/animal insulin Type of diabetes: Type 1 and 2 Mean age [years]: 54/53 human/animal insulin Mean diabetes duration [years]: 9/7 human/animal insulin Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine Duration of trial [months]: 12 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: ‐ 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] ‐ 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: ‐ 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: In toto 2 drop‐outs | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Larsen 1984.

| Methods | Trial design: Crossover study Randomisation procedure: Data missing Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Double‐blind | |

| Participants | Country: Denmark Setting: Single centre Number: 15 Type of diabetes: Type 1 Mean age [years]: N/A Mean diabetes duration [years]: N/A Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine Duration of trial [months]: 3 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: 9.2±1.2 vs 8.8±2.3 (hum. vs anim.) 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] ‐ 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: 52±16 vs 47±14 (hum. vs anim.) 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: In toto 2 drop‐outs | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

MacLeod 1995.

| Methods | Trial design: Crossover study Randomisation procedure: Data missing Allocation concealment: Adequate Blinding: Double‐blind | |

| Participants | Country: UK Setting: Single centre Number: 40 Type of diabetes: Type 1 Mean age [years]: 30 Mean diabetes duration [years]: N/A Other characteristics: Subgroup of patients with longer duration of diabetes | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine Duration of trial [months]: 3 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: 8.7±2.0 vs 8.6±2.4 (hum. vs anim.) 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] ‐ 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: ‐ 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: ‐ | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Mann 1983.

| Methods | Trial design: Crossover study Randomisation procedure: Data missing Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Double‐blinding | |

| Participants | Country: UK Setting: Single centre Number: 11/10 human/animal insulin (start) Type of diabetes: Type 1 diabetic children Mean age [years]: 12/11 human/animal insulin Mean diabetes duration [years]: 5/5 human/animal insulin Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine Duration of trial [months]: 4 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: 14.4±1.8 vs 13.8±1.7 (hum. vs anim.) 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] 12.0±2.1 vs 11.0±2.4 (hum. vs anim.) 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: 37±10 vs 37±13 (hum. vs anim.) 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: 3 vs 1 drop‐outs (hum. vs anim.) | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Maran 1993.

| Methods | Trial design: Crossover study Randomisation procedure: Data missing Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Double‐blind | |

| Participants | Country: UK Setting: Multi centre Number: 17 Type of diabetes: Type 1 Mean age [years]: 36 Mean diabetes duration [years]: 18 Other characteristics: Patients with altered perception of hypoglycaemia | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine Duration of trial [months]: 2 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: ‐ 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] ‐ 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: 51±21 vs 51±21 (hum. vs anim.) 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: 136 (8) vs 149 (9) (severe) hypoglycaemic episodes (hum. vs anim.) In toto 1 drop‐out | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Marshall 1988.

| Methods | Trial design: Parallel study Randomisation procedure: Adequate Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Double‐blind | |

| Participants | Country: Denmark Setting: Multi centre Number: 49/51 human/animal insulin Type of diabetes: Newly diagnosed type 1 diabetic children Mean age [years]: 9/9 human/animal insulin Mean diabetes duration [years]: N/A Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine Duration of trial [months]: 24 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: ‐ 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] ‐ 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: ‐ 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: 12 vs 13 drop‐outs (hum. vs anim.) | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Matyka 1995.

| Methods | Trial design: Crossover study Randomisation procedure: Data missing Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Double‐blind | |

| Participants | Country: UK Setting: Multi centre Number: 17 Type of diabetes: Type 1 Mean age [years]: N/A Mean diabetes duration [years]: 16 Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic (?) Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine (?) Duration of trial [months]: 2 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: ‐ 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] ‐ 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: ‐ 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: ‐ | |

| Notes | Limited information in abstract only | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Moffitt 1984.

| Methods | Trial design: Parallel study Randomisation procedure: Data missing Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Double‐blind | |

| Participants | Country: Australia Setting: Single centre Number: 10/11 human/animal insulin Type of diabetes: Type 2 Mean age [years]: 57/64 human/animal insulin Mean diabetes duration [years]: 11/9 human/animal insulin Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine Duration of trial [months]: 6 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: 9.8±0.8 vs 10.1±0.8 (hum. vs anim.) 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] 10.9 vs 10.1 (hum. vs anim.) 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: ‐ 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: 0 severe hypoglycaemic episodes 0 drop‐outs | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Oswald 1987.

| Methods | Trial design: Crossover study Randomisation procedure: Data missing Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Open | |

| Participants | Country: UK Setting: Single centre Number: 12 Type of diabetes: Type 1 Mean age [years]: 31 Mean diabetes duration [years]: 12 Other characteristics: Crossover of 4 insulin regimens | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine and bovine Duration of trial [months]: 2 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: ‐ 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] ‐ 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: ‐ 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: ‐ | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Pedersen 1987.

| Methods | Trial design: Crossover Randomisation procedure: Data missing Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Double‐blind | |

| Participants | Country: Denmark Setting: Single centre Number: 22 Type of diabetes: Type 1 Mean age [years]: 32 Mean diabetes duration [years]: 8 Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine Duration of trial [months]: 2 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: ‐ 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] 8.3±0.9 vs 8.7±0.9 (hum. vs anim.) 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: ‐ 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: 46 vs 39 hypoglycaemic episodes (hum. vs anim.) | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Porta 1988.

| Methods | Trial design: Parallel study Randomisation procedure: Data missing Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Open | |

| Participants | Country: Italy Setting: Multi centre Number: 32/23 human/animal insulin Type of diabetes: Type 1 and 2 Mean age [years]: 37/34 human/animal insulin Mean diabetes duration [years]: 12/10 human/animal insulin Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine Duration of trial [months]: 6 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: ‐ 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] ‐ 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: ‐ 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: In toto 5 drop‐outs | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Rogala 1993.

| Methods | Trial design: Parallel study Randomisation procedure: Data missing Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Double‐blind | |

| Participants | Country: Poland Setting: Single centre Number: 15/16 human/animal insulin Type of diabetes: Type 1 and 2 Mean age [years]: 36/34 human/animal insulin Mean diabetes duration [years]: N/A Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine Duration of trial [months]: 60 (unclear data) | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: 9.4 vs 9.9 (hum. vs anim.) 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] ‐ 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: ‐ 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: ‐ | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Russo 1991.

| Methods | Trial design: Parallel study Randomisation procedure: Unclear Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Double‐blind | |

| Participants | Country: Brasil Setting: Multi centre Number: 10/9 human/animal insulin Type of diabetes: Type 1 Mean age [years]: 18/22 human/animal insulin Mean diabetes duration [years]: N/A Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine and bovine Duration of trial [months]: 6 | |

| Outcomes | 4.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: 7.4±1.5 vs 7.4±3.2 (hum. vs anim.) 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] 15.4±5.7 vs 12.3±4.1 (hum. vs anim.) 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: 55±24 vs 49±24 (hum. vs anim.) 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: ‐ | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Sailer 1986.

| Methods | Trial design: Crossover study Randomisation procedure: Data missing Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Double‐blind | |

| Participants | Country: Germany Setting: Single centre Number: 13/7 human/animal insulin Type of diabetes: Type 1 and 2 Mean age [years]: N/A Mean diabetes duration [years]: N/A Other characteristics: | |

| Interventions | Type of human insulin: Semi‐synthetic Type of animal insulin: Purified porcine Duration of trial [months]: 1.5 | |

| Outcomes | 1.HbA1c [%]: ‐ 2.HbA1 [%]: 9.0±0.9 vs 8.8±0.9 (hum. vs anim.) 3.Fasting plasma glucose [mmol/L] 6.7±1.9 vs 6.7±2.2 (hum. vs anim.) 4.Insulin dose [Units/day]: 58±12 vs 58±12 (hum. vs anim.) 5.Insulin antibodies [%]: ‐ 6.Adverse effects: 0 hypoglycaemic episodes 0 drop‐outs | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Santana 1987.

| Methods | Trial design: Parallel study Randomisation procedure: Adequate Allocation concealment: Unclear Blinding: Open | |