Abstract

Background

In the treatment of chronic heart failure, vasodilating agents, ACE inhibitors and beta‐blockers have shown an increase of life expectancy. Another strategy is to increase the inotropic state of the myocardium : phosphodiesterase inhibitors (PDIs) act by increasing intra‐cellular cyclic AMP, thereby increasing the concentration of intracellular calcium, and lead to a positive inotropic effect.

Objectives

This overview on summarised data aims to review the data from all randomised controlled trials of PDIs III versus placebo in symptomatic patients with chronic heart failure. The primary endpoint is total mortality. Secondary endpoints are considered such as cause‐specific mortality, worsening of heart failure (requiring intervention), myocardial infarction, arrhythmias and vertigos. We also examine whether the therapeutic effect is consistent in the subgroups based on the use of concomitant vasodilators, the severity of heart failure, and the type of PDI derivative and/or molecule. This overview updates our previous meta‐analysis published in 1994.

Search methods

Randomised trials of PDIs versus placebo in heart failure were searched using MEDLINE (1966 to 2004 January), EMBASE (1980 to 2003 December), Cochrane CENTRAL trials (The Cochrane Library Issue 1, 2004) and McMaster CVD trials registries, and through an exhaustive handsearching of international abstracting publications (abstracts published in the last 22 years in the "European Heart Journal", the "Journal of the American College of Cardiology" and "Circulation").

Selection criteria

All randomised controlled trials of PDIs versus placebo with a follow‐up duration of more than three months.

Data collection and analysis

Twenty one trials (8408 patients) were eligible for inclusion in the review. Four specific PDI derivatives and eight molecules of PDIs have been considered.

Main results

As compared with placebo, treatment with PDIs was found to be associated with a significant 17% increased mortality rate (The relative risk was 1.17 (95% confidence interval 1.06 to 1.30; p< 0.001). In addition, PDIs significantly increase cardiac death, sudden death, arrhythmias and vertigos. Considering mortality from all causes, the deleterious effect of PDIs appears homogeneous whatever the concomitant use (or non‐use) of vasodilating agents, the severity of heart failure, the derivative or the molecule of PDI used.

Authors' conclusions

Our results confirm that PDIs are responsible for an increase in mortality rate compared with placebo in patients suffering from chronic heart failure. Currently available results do not support the hypothesis that the increased mortality rate is due to additional vasodilator treatment. Consequently, the chronic use of PDIs should be avoided in heart failure patients.

Keywords: Humans; 3',5'‐Cyclic‐AMP Phosphodiesterases; 3',5'‐Cyclic‐AMP Phosphodiesterases/antagonists & inhibitors; Administration, Oral; Cyclic Nucleotide Phosphodiesterases, Type 3; Heart Failure; Heart Failure/drug therapy; Heart Failure/mortality; Phosphodiesterase Inhibitors; Phosphodiesterase Inhibitors/adverse effects; Phosphodiesterase Inhibitors/therapeutic use; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Phosphodiesterase III inhibitor class drugs taken orally and long term are associated with increased deaths in heart failure

A number of options are available to treat symptomatic chronic heart failure. These include ACE inhibitors, beta‐blockers and spironolactone, which result in an increase of life expectancy. Another strategy is to increase the strength of the pumping action of the heart as with digitalis and with phosphodiesterase III inhibitors. The review clearly showed evidence that people treated for chronic heart failure for three months or more with phosphodiesterase III inhibitors were more likely to die than people given an inactive placebo treatment.

Background

Heart failure leads to an impaired quality of life, morbidity requiring frequent hospitalizations, and shortened life expectancy. The treatment of chronic heart failure has evolved over the past 20 years, in particular with the introduction of vasodilators (Chatterjee 1980; Cohn 1973; Cohn 1977). Hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate were first shown to reduce mortality (Cohn 1986), but have been superceded by angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors which have been evaluated in several clinical trials and meta‐analyses (Braunwald 1991; Cohn 1991; CONSENSUS 1987; Furberg 1988; Garg 1995; Mulrow 1988; SOLVD 1991). More recently, in conjunction with conventional treatment with diuretics and angiotensin‐converting enzyme inhibitors, beta blockers (bisoprolol, metoprolol and carvedilol) have been shown to improve myocardial function and survival when used in stable and euvolemic patients (CIBIS II 1999; MERIT‐HF 1999; Packer 2001).

Another therapeutic strategy involves the use of drugs which can enhance the inotropic state of the failing heart (i.e. to increase the strength of the pumping action of the heart), e.g. digitalis glycosides, sodium‐channel agonists, or drugs able to increase the concentration of intra‐cellular cyclic AMP (cAMP), either by promoting its synthesis (beta‐adrenergic agonists) or by retarding its degradation (phosphodiesterase inhibitors) (PDIs) (DiBianco 1991; Storstein 1988; Weber 1987). PDIs act by increasing intra‐cellular cyclic AMP, thereby increasing the concentration of intracellular calcium, and lead to a positive inotropic effect. PDIs also affect vascular smooth muscle causing vasodilation.

Because of their attractive mechanism of action and pharmacological profile many phosphodiesterase inhibitors have been synthesised with a variety of dissimilar structures. The development of amrinone, and its more potent analogue milrinone, (both pyridinone derivatives) was followed by the synthesis and pharmacological characterisation of many related positive inotropic agents (e.g. enoximone and piroximone derived from imidazolone, pimobendan, imazodan, indolidan and flosequinan derived from pyridazinone, OPC‐8212 and vesnarinone derived from quinolinone).

It is thought that these drugs, by means of their common acidic amide function, compete with the phosphate function of cAMP for binding to the esteratic site of Phosphodiesterase III (PDE III), thereby causing competitive inhibition of this enzyme and accumulation of intra‐cellular cAMP.

The efficacy on mortality of the PDIs was first evaluated in one clinical trial with sufficient statistical power in patients with stage III to IV heart failure. After a median follow‐up of 6.1 months (range 1 day to 20 months), a 28% increase in total mortality was observed in the group receiving milrinone compared with that receiving placebo and the trial was prematurely terminated (PROMISE 1991). Some previous trials (AMTG 1985; EMTG 1990; MMTG 1989; Packer 1984; Rettig 1986), several reviews (Hood 1989; Packer 1988a; Wood 1989), and one meta‐analysis (Yusuf 1990), have suggested a similar increased mortality rate of PDIs as compared to placebo.

However, after the publication of the results of three trials testing vesnarinone (Feldman 1991; OPC‐8212 MRG 1990; VSG 1993), a more recent meta‐analysis (Nony 1994) found a significant heterogeneity of the therapeutic effect due to the inclusion of the data of the vesnarinone trials. Vesnarinone is a drug with multiple mechanisms of action that appears to enhance contractility through ion‐channel effects that augment sodium‐calcium exchange. Short‐term administration of vesnarinone to patients with heart failure was associated with limited and variable haemodynamic effects, but small placebo‐controlled trials showed a favourable effect on the quality of life and morbidity (Feldman 1991). In a first multicenter study, initiated in 1990 (VSG 1993), a significant 50 percent reduction in the combined end point and a 61 % reduction in mortality from all causes were observed in the vesnarinone‐treated group. However the results were problematic (short duration of the trial and contradictory results between the two studied regimens) and the " Vesnarinone trial " (VEST 1998) was therefore initiated in 1995 to study the long‐term effects of 60 mg or 30 mg of vesnarinone daily. However results showed a dose‐related increase in mortality in response to vesnarinone.

Several possible explanations for the deleterious effects of PDIs on mortality have been proposed (Curfman 1991; Feldman 1987; Packer 1988b), including: 1) an excessive increase of intracellular cyclic AMP, which decreases in chronic heart failure patients, possibly as an adaptive response; 2) an arrhythmogenic effect; or 3) a potentiation of the deleterious effects of PDIs by concomitant treatment with vasodilators. This last phenomenon may account either for the observed increase in mortality rate or for the adverse effects, such as hypotension, blurred vision and syncope, reported under treatment. However, the increased mortality in the last vesnarinone trial was attributed to an increased incidence of sudden death (VEST 1998), which was seen in previous trials of milrinone and flosequinan. Whether these drugs exert direct arrhythmic effects or accelerate structural remodeling of the ventricle, thus providing the substrate for ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation, is unknown. The favourable effects of ACE inhibitors, the combination of isosorbide dinitrate and hydralazine, and beta‐blockers on the incidence of sudden death appear to be associated with the regression of structural ventricular remodeling, thus suggesting a link between ventricular dilatation and lethal arrhythmias. Unfortunately, the effect of vesnarinone on ventricular volume was not assessed in the last "vesnarinone trial". In view of these contradictory findings, and the likelihood that PDIs are harmful in chronic heart failure, a systematic review of all the evidence is needed. In addition, the PDIs III class effect will be revisited, in order to investigate for specific derivatives which are less dangerous than others. Lastly, such an overview will be an update of our previous published meta‐analysis (Nony 1994).

Objectives

The main aim is to systemically review the data from all randomised controlled trials of orally administered PDIs III versus placebo in symptomatic patients with chronic heart failure. The primary endpoint is total mortality. Secondary endpoints are considered such as cause‐specific mortality (cardiac or sudden death), worsening of heart failure, myocardial infarction, arrhythmias and vertigos. We also examine whether the therapeutic effect is consistent within the subgroups based on the use of concomitant vasodilators, the severity of heart failure, the type of molecule or derivative.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Clinical trials are included in our meta‐analysis if they satisfy the following inclusion criteria:

randomised, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind studies of orally administered PDI therapy;

trials with a well‐defined "a priori" end‐point;

trials having a minimum follow‐up of 3 months;

trials with data available using an intention to treat strategy;

No more than 10% loss to follow‐up for relevant clinical outcome.

Trials in which patients are not randomised are excluded from the meta‐analysis.

Types of participants

Patients with an overt chronic heart failure (class II to IV, NYHA scale), where the mention of age range, criteria for diagnosis of heart failure (i.e. clinical findings or objective indices) were included.

Types of interventions

Selected studies are those with the following comparisons :

PDIs III versus placebo;

4 specific derivatives and 9 molecules of PDIs were considered (Table 1);

subgroups investigated the effect of PDI on the concomitant use (or non‐use) of vasodilating agents, on the severity of heart failure (inclusion or non inclusion of NYHA class IV patients), on the type of molecules and derivatives.

1. Characteristics of the included trials.

| Id trial | Nb of patients | Follow‐up (months) | Severity of CHF | Molecule type | Derivative | Dose per day | Vasodilator used |

| AMTG 1985 | 99 | 3 | III, IV | Amrinone | Pyridinone | < 600 mg | YES |

| Berger‐Klein 1992 | 24 | 3 | II, III | Pimobendan | Pyridazinone | 10 mg | NO |

| Cowley 1993 | 135 | 4 | II, III | Flosequinan | Pyridazinone | 125 mg | NO |

| Cowley 1994 | 151 | 12 | III, IV | Enoximone | Imidazolone | 300 mg | YES |

| Dies 1989 | 74 | 3 | II, III | Indolidan | Pyridazinone | NA | YES |

| EMTG 1990 | 102 | 4 | II, III | Enoximone | Imidazolone | < 450 mg | NO |

| EPOCH 2002 | 298 | 12 | II, III | Pimobendan | Pyridazinone | 2.5 & 5 mg | YES |

| ESG 2000 | 105 | 3 | II, III | Enoximone | Imidazolone | 75 & 150 mg | YES |

| FACET 1993 | 322 | 4 | II, III | Flosequinan | Pyridazinone | 100 & 150 mg | YES |

| IRG 1991 | 147 | 3 | III, IV | Imazodan | Pyridazinone | 4, 10 & 20 mg | YES |

| Lardoux 1987 | 43 | 3 | NA | Enoximone | Imidazolone | 150 & 300 mg | NO |

| MMTG 1989 | 230 | 3 | II, III & IV | Milrinone | Pyridinone | < 40 mg | NO |

| OPC‐8212 MRG 1990 | 83 | 3 | II, III & IV | Vesnarinone | Quinolinone | 60 mg | YES |

| PICO 1996 | 331 | 6 | II, III | Pimobendan | Pyridazinone | 2.5 & 5 mg | YES |

| PMRG 1992 | 198 | 3 | II, III | Pimobendan | Pyridazinone | 2.5, 5 & 10 mg | YES |

| PROMISE 1991 | 1088 | 20 | III, IV | Milrinone | Pyridinone | 40 mg | YES |

| REFLECT 1993 | 193 | 3 | II, III | Flosequinan | Pyridazinone | 100 mg | NO |

| REFLECT II 1991 | 311 | 3 | II, III & IV | Flosequinan | Pyridazinone | 100 & 150 mg | NO |

| VEST 1998 | 3833 | 9 | III, IV | Vesnarinone | Quinolinone | 30 & 60 mg | YES |

| VSG 1993 | 477 | 6 | II, III & IV | Vesnarinone | Quinolinone | 60 mg | YES |

| WESG 1991 | 164 | 3 | II, III | Enoximone | Imidazolone | 150 & 300 mg | NO |

Types of outcome measures

Summarised data were collected where available in the publication, for each considered end‐point :

Primary endpoint: total mortality;

Secondary endpoints: cardiac death, sudden death, worsening of heart failure (requiring intervention like hospitalisation, modification of treatments, withdrawal from study), occurrence of myocardial infarction, cardiac transplantation, arrhythmias as defined by authors, and vertigos (dizziness, lipothymia or syncope).

Search methods for identification of studies

Relevant clinical trials were found:

by computerised searches of MEDLINE (1966 to 2004 February), EMBASE (1980 to 2004 February), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library Issue 1, 2004 and McMaster CVD trials registries;

by scanning general reviews, overviews, guidelines, consensus conference reports;

by exhaustive handsearching of international abstracting publications of congress (abstracts published in the last 22 years from 1980 to September 2002 in the "European Heart Journal" for ECC, the "Journal of the American College of Cardiology" for ACC and "Circulation" for AHA);

by contacting experts, investigators, public research institutions and the manufacturers of PDIs;

No language restrictions were applied.

The computer search of the CENTRAL database (The Cochrane Library Issue 1, 2004) was performed using the following specific terms see Appendix 1: The search was adapted for use in other databases. Strategies used in MEDLINE and EMBASE are listed in Appendix 2 and Appendix 3.

Data collection and analysis

Data selection and extraction

All references identified were evaluated by two reviewers (CK, HG) to determine relevant articles for full text retrieval. The retrieved references were assessed for eligibility by two reviewers according to the pre‐specified inclusion criteria. For each trial fulfilling the inclusion criteria an assessment of methodological quality (allocation concealment and blinding) was done by two reviewers independently. Data extraction was also done independently by two reviewers using a standardised form and all extracted data were checked by the first author (EA). The information collected from each trial included study design, patient characteristics, interventions, outcomes. Any discordance between reviewers has been settled by a third reviewer (PN). Authors of studies were contacted when additional information was required.

Data analysis

Meta‐analytical techniques (Boissel 1989; Nony 1995; Nony 1997; Yusuf 1987) are used to increase the power of hypothesis tests and also to obtain information which is not directly available from individual trials. Since there was no way of deciding which effect model would be the most suitable (Nony 1994), the following methods are used for each analysis (additive, multiplicative or mixed models) :

risk difference method (additive model) (Yusuf 1987);

logarithm of relative risk (multiplicative model);

Greenland & Robins relative risk (multiplicative model);

logarithm of odds ratio method (multiplicative model) (Baptista 1977; Fleiss 1973);

Cochran method (Cochran 1954);

Mantel‐Haenszel method (Mantel 1959);

Peto method (Peto 1978).

The last three methods use a weighted function of the rate difference and are therefore different from the additive and multiplicative models. Using each method we calculated the value of the association statistic and thus the corresponding chi‐square statistic. The homogeneity chi‐square, calculated as the difference between the total chi‐square statistic and the association chi‐square statistic, enables the degree of homogeneity or equality among the values of association to be assessed. In case of non‐homogeneity (i.e. p<0.10), random effect models has been used (Der Simonian 1986). The results were expressed as the mean difference, the relative risk, the odds ratio, or the mean standardised difference (if appropriate), with a 95% confidence interval.

Significance level

association: to be cautious, only the "worst" (the least significant) p‐value for the association test should be taken into consideration for the conclusion, especially when there is no prior knowledge of the effect model the level of significance is set at p = 0.05;

homogeneity: since statistical tests lack power to measure heterogeneity, we use an empirical significance level at p = 0.10.

Results

Description of studies

From the 144 references of potential clinical trials initially selected, only 36 references (21 randomised controlled trials) satisfied our inclusion criteria and were included in this analysis. The main characteristics of these studies are summarised in Table 1 and the Characteristics of Included Studies table. The reasons for the exclusion of the remaining 108 references were :

narrative or review articles (23 references: 23 studies);

multiple publications (20 references: 15 studies);

uncontrolled trials or absence of placebo group (14 references: 14 studies);

more than 10% loss to follow up for relevant clinical outcome (13 references: 13 studies);

no relevant clinical data available and/or duration of treatment too short (13 references: 13 studies);

comparison with active treatment and/or acute IV administration of PDI and/or dose comparison of PDI (12 references: 12 studies);

withdrawal study (4 references: 4 studies);

intent to treat analysis impossible to perform (1 reference: 1 study);

studies awaiting assessment (8 references: 4 studies).

For the PROFILE (flosequinan) study, only an ancillary study has been published (PROFILE 1993) (Table 2) and we considered that a specific additional assessment was necessary. According to the above mentioned chemical structures of PDIs, we included the flosequinan studies in our meta‐analysis, whereas the most important pharmacologic activities of this drug consist in vasodilation. A further sensitivity analysis has been performed with the study of the subgroup of the flosequinan trials. As in the majority of studies on heart failure, the inclusion criteria for patients were : functional status (NYHA class II to IV); chest X‐ray film showing cardiac enlargement; impairment of ventricular performance (measured using non‐invasive techniques; and/or decreased duration of exercise).

2. Characteristics of studies awaiting assessment.

| Study ID | Description |

| Goldberg 1990 | 147 patients were randomized but the number of patients per group wasn't available |

| Kato 1991 | Article in Japanese. 100 patients were randomized and the duration of treatment was 4 weeks |

| Kato 1992 | Article in Japanese. 81 patients were randomized and the duration of treatment was 8 weeks |

| MIL 1077‐1078 | 254 patients were randomized but the number of patients per group wasn't available |

| Profile 1993 | 2345 patients were randomised and 431 deaths occurred (208 sudden death). On interim analyses (n=2304), flosequinan was significantly associated with an excess of mortality when compared with placebo (RR=1.43; p<0.05). Definite results were never published |

The exclusion criteria included obstructive valvular disease, active myocarditis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, or malfunctioning artificial heart valve. Patients were also usually excluded if they had severe : symptomatic ventricular arrhythmia; angina pectoris; primary pulmonary, renal, or hepatic disease; hypotension (systolic blood pressure below 85 mm Hg); or acute or recent myocardial infarction.

The characteristics of included patients in the trials are described in Table 3 and the Characteristics of Included Studies Table. On average, age of patients in the trials varied from 50 to 66.6 years. The proportion of men varied from 65.1% to 91.7% and the mean LVEF from 19% to 43.5% with most of values around 23%. The aetiology of heart failure was ischaemic for 16.7% to 78.1% of patients and non‐ischaemic for 21.9% to 83.3% of them. Concomitant therapy (Table 3 and the Characteristics of Included Studies table) generally consisted of digitalis and diuretics. In some trials particularly the earlier ones, no treatment with vasodilators was allowed, in particular no nitrate derivatives, hydralazine, alpha‐receptor blocking drugs or ACE inhibitors (Table 1).

3. Characteristics of patients included in the trials.

| Id trial | Age (mean: year) | Sex (%male) | LVEF (mean: %) | Etiology | NYHA Class | Treatments |

| AMTG 1985 | 55.5 | 87.9 | 21.5 | Ischemic: 52.5% Non‐ischemic: 47.5% | III: 90% IV: 10% | Diuretics: 100% Digitalics: 98% |

| Bergler‐Klein 1992 | 50 | 91.7 | 19 | Ischemic: 16.7% Non‐ischemic: 83.3% | II: 54.2% III: 45.8% | ACEi: 0% |

| Cowley 1993 | 62.9 | 66.7 | NS | Ischemic: 69.6% Non‐ischemic: 30.4% | II: 89.6% III: 10.4% | ACEi: 0% |

| Cowley 1994 | 66.6 | 80.8 | NS | Ischemic: 78.1% Non‐ischemic: 21.9% | III: 76.8% IV: 23.2% | Diuretics:100% ACEi: 94.7% |

| Dies 1989 | NS (not stated) | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| EMTG 1990 | 61.5 | 72.5 | 21.5 | Ischemic: 49% Non‐ischemic: 51% | II: 35.3% III: 64.7% | Diuretics: 100% Digitalics: 100% ACEi: 0% |

| EPOCH 2002 | 63.9 | 73.6 | 32.9 | Ischemic: 33.7% Non‐ischemic: 66.3% | II: 66.3% III: 33.7% | Diuretics: 81.5% Digitalics: 59.1% ACEi: 33% |

| ESG 2000 | 59.5 | 76.2 | 23 | Ischemic: 56.2% Non‐ischemic: 43.8% | I: 1% II: 47.6% III: 51.4% | Diuretics: 93.3% Digitalics: 82.9% |

| FACET 1993 | 58 | 71 | 23 | Ischemic: 41% Non‐ischemic: 59% | II: 53% III: 44% IV: 3% | Diuretics: 96% Digitalics: 89% ACEi: 100% |

| IRG 1991 | 59 | 87.1 | 23 | Ischemic: 53.1% Non‐ischemic: 46.9% | I‐II: 46.2% III: 49% IV: 4.8% | Diuretics: 100% Digitalics: 84.4% ACEi: 55.1% |

| Lardoux 1987 | 61.2 | NS | NS | Ischemic: 48.8% Non‐ischemic: 51.2% | NS | ACEi: 0% |

| MMTG 1989 | 59.3 | 70.5 | 24 | Ischemic: 51% Non‐ischemic: 49% | II: 29.3% III: 66.7% IV: 4% | Digitalics: 53% ACEi: 23.5% |

| OPC‐8212 MRG 1990 | 58.5 | 65.1 | 43.5 | Ischemic: 16.9% Non‐ischemic: 83.1% | NS | Diuretics: 75.9% Digitalics: 74.7% |

| PICO 1996 | 65.5 | 80 | 27 | Ischemic: 69% Non‐ischemic: 31% | II: 52% III: 48% | Diuretics: 100% Digitalics: 59% ACEi: 100% |

| PMRG 1992 | 58 | 78.3 | 22 | Ischemic: 43.9% Non‐ischemic: 56.1% | III: 96% IV: 4% | Diuretics: 98% Digitalics: 88.4% ACEi: 79.8% |

| PROMISE 1991 | 63.7 | 78.4 | 21 | Ischemic: 54.2% Non‐ischemic: 45.8% | III: 58% IV: 42% | Diuretics: 100% Digitalics: 100% ACEi: 100% |

| REFLECT 1993 | 57.7 | 87 | 25.5 | Ischemic: 43.5% Non‐ischemic: 56.5% | II: 42% III: 58% | Diuretics: 100% Digitalics: 96% ACEi: 0% |

| REFLECT II 1991 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | ACEi: 0% |

| VEST 1998 | 63 | 76.3 | 20.9 | Ischemic: 58.2% Non‐ischemic: 41.8% | III: 84.9% IV: 15.1% | ACEi: 90% |

| VSG 1993 | 58.2 | 86.8 | 20 | Ischemic: 52.2% Non‐ischemic: 47.8% | I: 0.8% II: 18.7% III: 69.6% IV: 10.9% | Digitalics: 87.2% ACEi: 89.5% |

| WESG 1991 | 58.8 | 79.3 | 24.7 | Ischemic: 45.7% Non‐ischemic: 54.3% | II: 42.1% III: 57.9% | ACEi: 0% |

Risk of bias in included studies

Blinding

All included studies but one (Dies 1989: type of blinding not stated) were double‐blind placebo controlled trials.

Randomisation

The method of randomisation was concealed for five RCTs (AMTG 1985; EPOCH 2002; MMTG 1989; PROMISE 1991; VEST 1998; VSG 1993) that included 6025 patients (71.7% of all available patients). In one trial (AMTG 1985) the randomisations were stratified on concomitant treatment with ACE inhibitors or not, and therefore these subgroups of patients were included in the analyses examining concomitant vasodilators.

Type and language of publication

Four trials (Dies 1989; Lardoux 1987; PROFILE 1993; REFLECT II 1991) have only been published as an abstract. In three trials (Dies 1989; Lardoux 1987; REFLECT II 1991) , 428 patients were included. In the PROFILE 1993 trial 2345 patients were randomised and 431 deaths occurred (208 sudden death). On interim analyses (n=2304), flosequinan was significantly associated with an excess of mortality when compared with placebo (RR=1.43; p<0.05). Definite results were never published and no other information was available. Currently, this study is awaiting assessment before definite exclusion for unavailability of data. One trial (Bergler‐Klein 1992) included in this review was only published in german. This paper was translated before inclusion.

Loss to follow‐up

The proportion of participants lost to follow‐up was not stated in four trials (Cowley 1994; Dies 1989; EMTG 1990; ESG 2000) including 432 patients. In seven trials (Bergler‐Klein 1992; FACET 1993; IRG 1991; MMTG 1989; PROMISE 1991; VEST 1998; VSG 1993) no patient has been lost to follow‐up (6121 patients: 72,8% of all available patients). In the ten other trials (1855 patients) the proportion of patients loss to follow‐up was between 2.2% and 9.6%.

Primary outcome

A primary outcome was described in 14 trials and was clinically relevant in only four trials (EPOCH 2002; PROMISE 1991; VEST 1998; VSG 1993) including 5696 patients (67.7% of all available patients). In the remaining ten trials the primary outcome used was "exercise tolerance".

Effects of interventions

Description of search strategy results

Using MEDLINE and EMBASE databases, we found 1470 references, whereas 263 and 62 references were identified respectively with CENTRAL and the McMaster CVD trials registry.

Meta‐analysis results

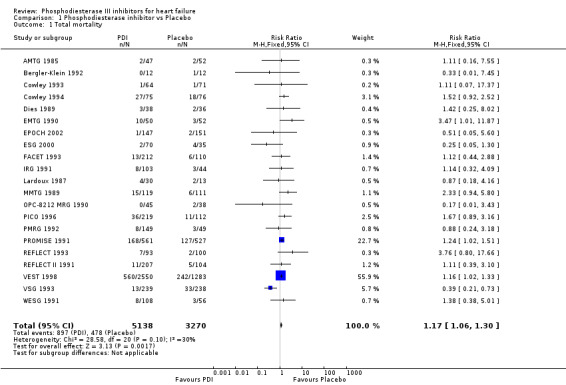

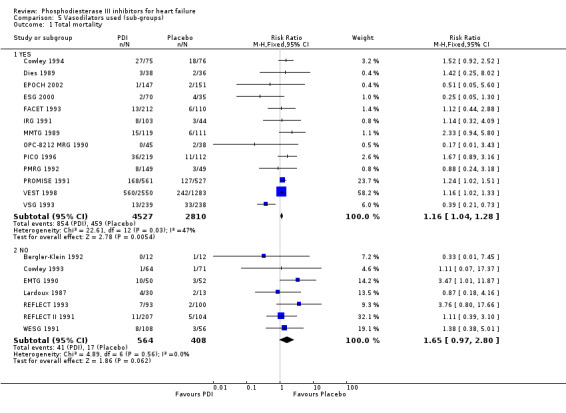

Total mortality

Treatment with PDI was found to be associated with a significant increased mortality rate with relative risk 1.17 (95% Confidence Interval 1.06 to 1.30; p= 0.002) compared with placebo. However the test for heterogeneity was borderline significant (p=0.10) irrespective of the fixed relative risk effect model used see Comparison 01 01. For other statistical methods a significant heterogeneity has been observed: Log odds ratio, heterogeneity p=0.076; Mantel‐Haenzel odds ratio, heterogeneity p=0.031; Peto odds ratio, heterogeneity p=0.028; Cochran odds ratio, heterogeneity p=0.036; and Risk difference heterogeneity p= 0.0006.

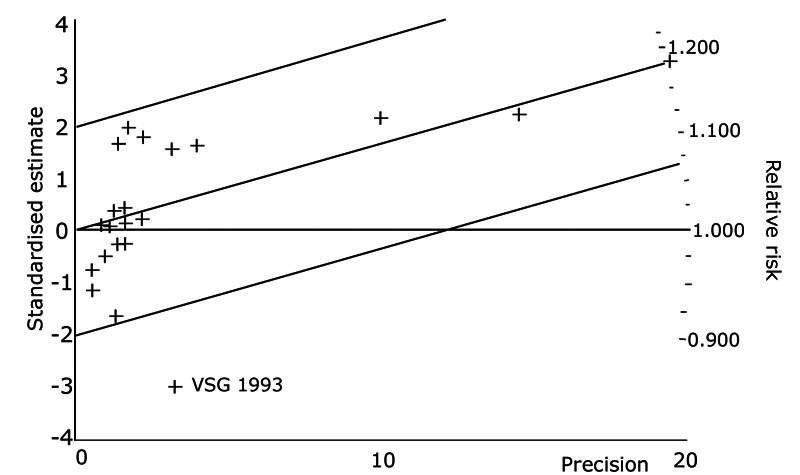

The results from the various meta‐analysis techniques are shown in Table 4. Using the radial plot approach (Galbraith 1988) (Figure 1) the heterogeneity of the PDIs effect among trials seems essentially due to the results of the multicenter study of VSG 1993 (see Figure 1).

4. Summary of results (end point: total mortality).

| Statistical Method | Fixed Effect | Random Effect |

| Logarithm of the relative risk (RR) | 1.180 (95% CI 1.067 to 1.305); p<0.001; p‐hetero=0.10 | |

| Greenland & Robins (RR) | 1.175 (95% CI 1.062 to 1.299); p=0.002; p‐hetero=0.10 | |

| Logarithm of the odds ratio (OR) | 1.224 (95% CI 1.079 to 1.388); p=0.002; p‐hetero=0.076 | 1.201 (95% CI 0.946 to 1.526); p=0.13 |

| Mantel‐Haenzel (OR) | 1.223 (95% CI 1.079 to 1.386); p=0.002; p‐hetero=0.031 | 1.201 (95% CI 0.946 to 1.526); p=0.13 |

| Peto (OR) | 1.220 (95% CI 1.078 to 1.380), p=0.002; p‐hetero=0.028 | 1.201 (95% CI 0.946 to 1.526); p=0.13 |

| Cochrane (OR) | 1.215 (95% CI 1.075 to 1.374), p=0.002; p‐hetero=0.036 | 1.201 (95% CI 0.946 to 1.526); p=0.13 |

| Risk Difference (RD) | 2.58% (95% CI 1.01% to 4.16%), p = 0.001; p‐hetero=0.0006 | 1.17 (95% CI ‐0.86 to 3.19); p=0.24 |

1.

Exploration of heterogeneity between PDI trials for total mortality. Relative risk, Fixed model ‐ Radial plot . The VSG 1993 trial is outside of the limits of homogeneity of the treatment effect. This illustrates the heterogeneity introduced by this trial for total mortality.

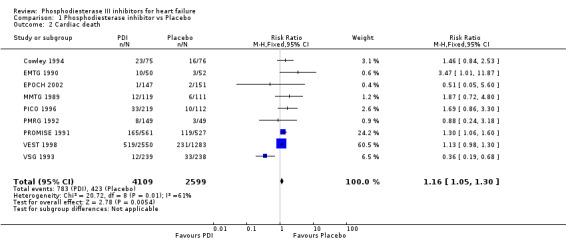

Secondary endpoints

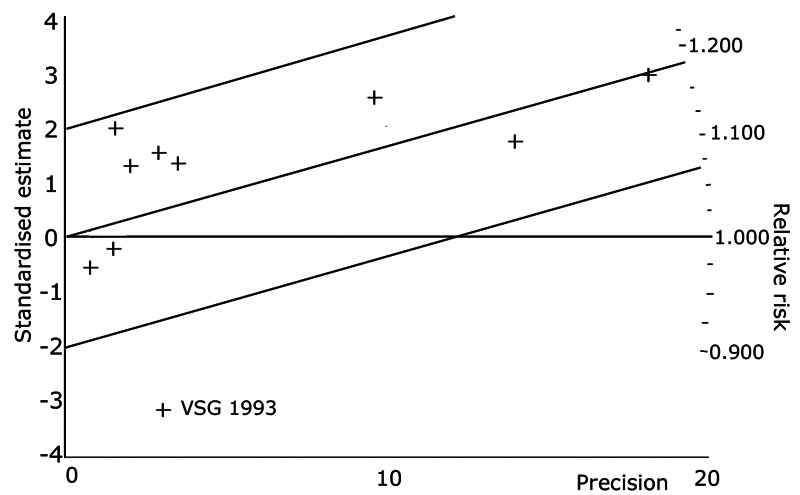

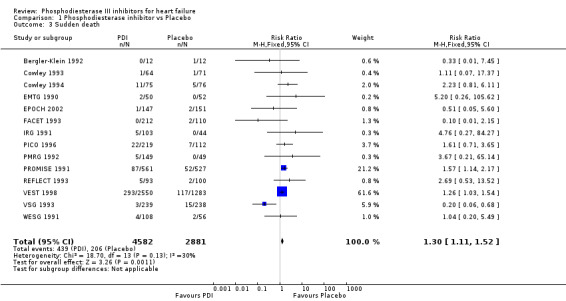

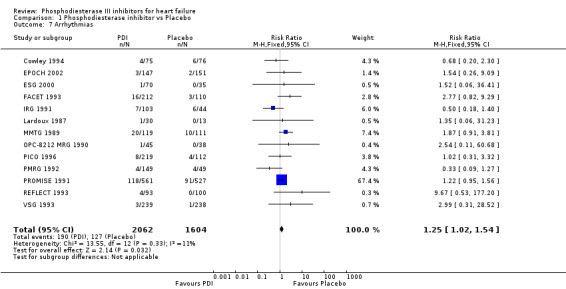

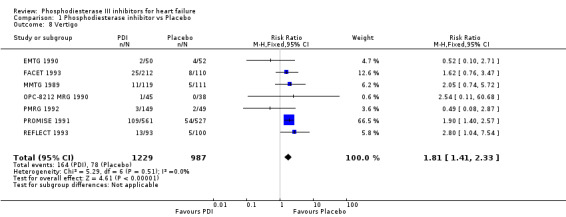

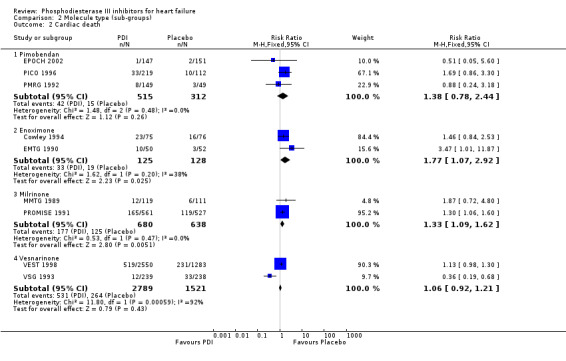

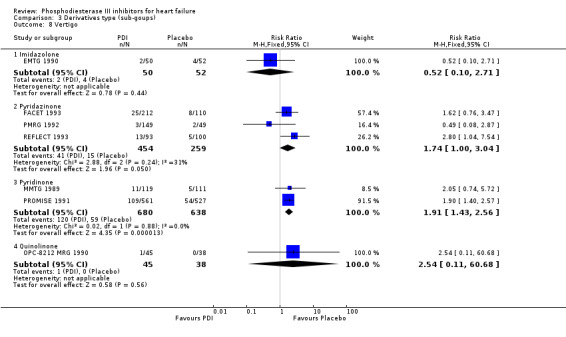

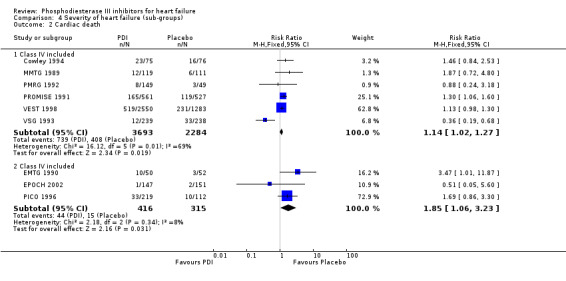

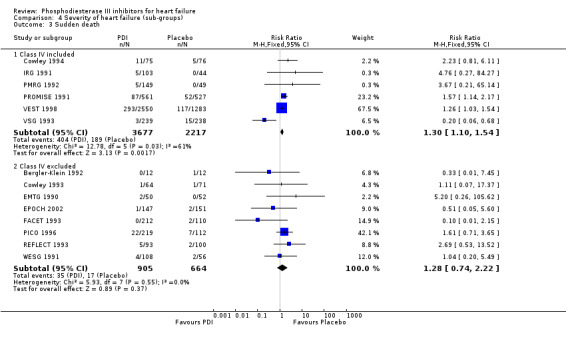

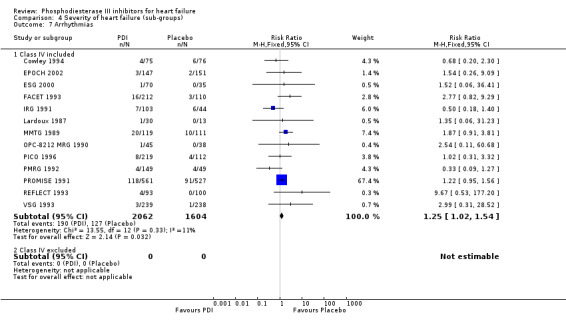

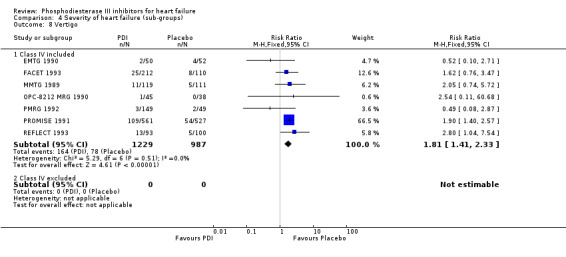

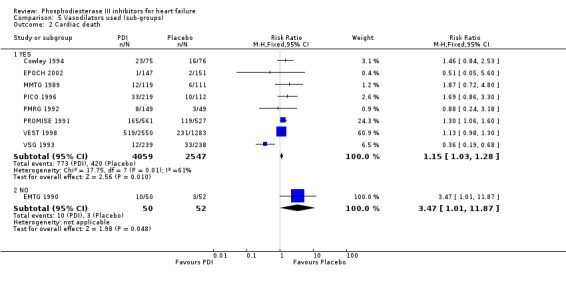

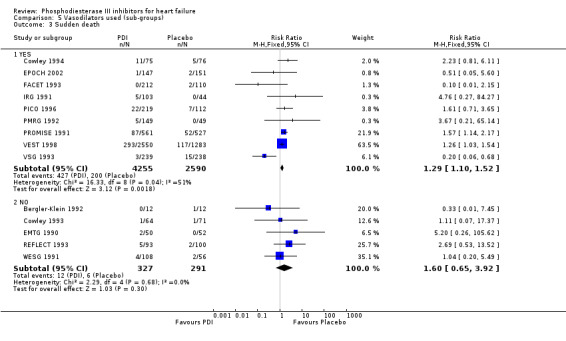

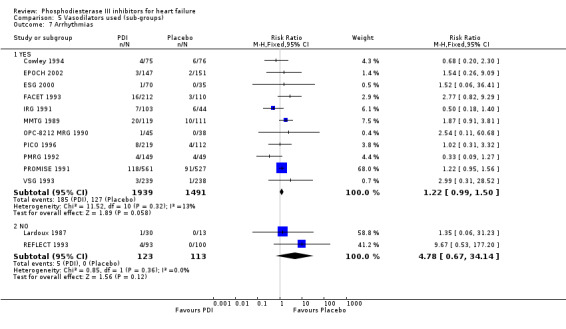

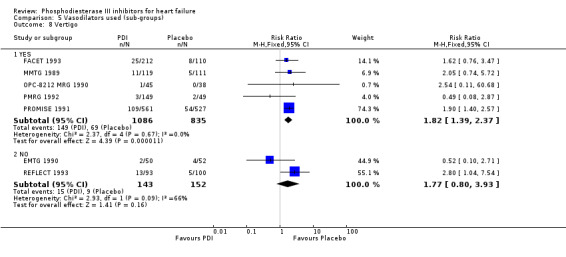

Compared with placebo PDIs significantly increased cardiac death with relative risk 1.16 (95% confidence interval 1.05 to 1.30; p=0.005), sudden death with relative risk 1.30 (95% confidence interval 1.11 to 1.52; p=0.001), arrhythmias with relative risk 1.25 (95% confidence interval 1.02 to 1.54; p=0.03) and vertigo with relative risk 1.81 (95% confidence interval 1.41 to 2.33; p<0.001). Again a significant heterogeneity was observed for cardiac death (p=0.008). The radial plot shown that this heterogeneity among trials on cardiac death is essentially due to the results of the study VSG 1993 (Figure 2). When a random effects model was used the effect of PDI on cardiac death was non significant and had a relative risk of 1.18 (95% confidence interval : 0.90 to 1.55; p=0.23).

2.

Exploration of heterogeneity between PDI trials for cardiac death. Relative risk, fixed model ‐ Radial plot. The VSG 1993 trial is outside of the limits of homogeneity of the treatment effect. This illustrates the heterogeneity introduced by this trial for cardiac death.

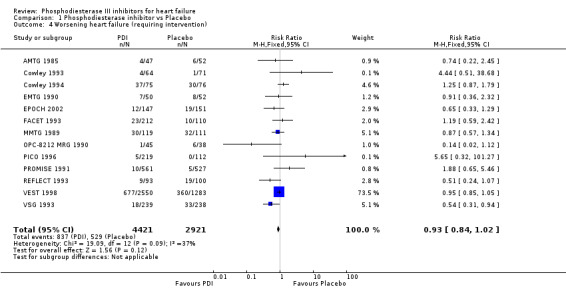

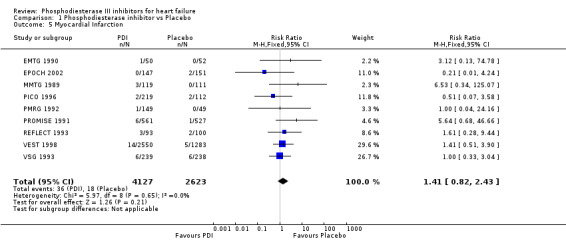

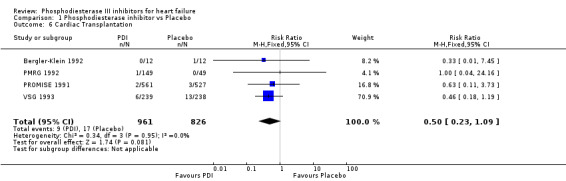

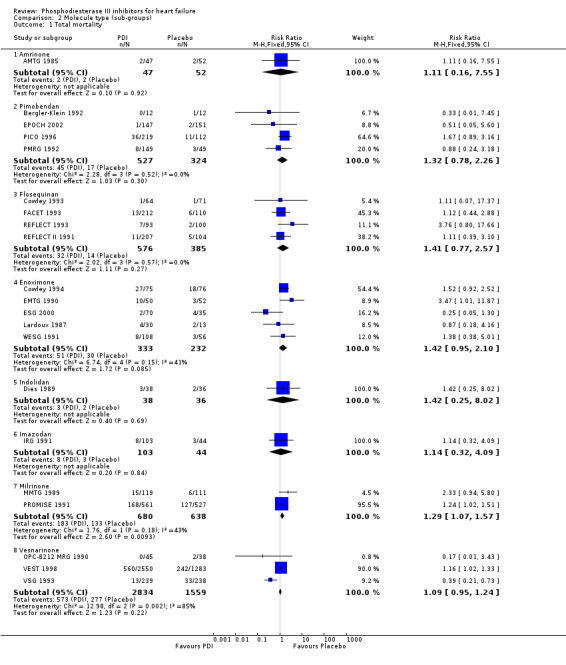

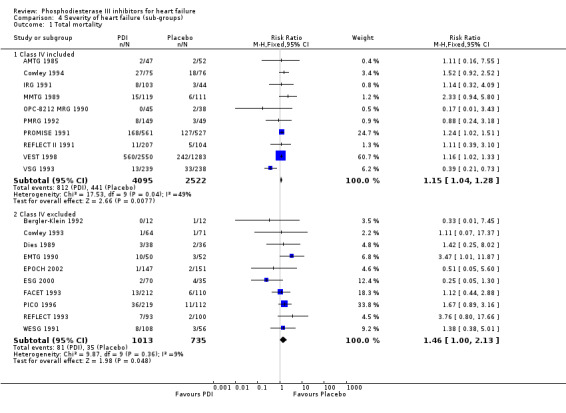

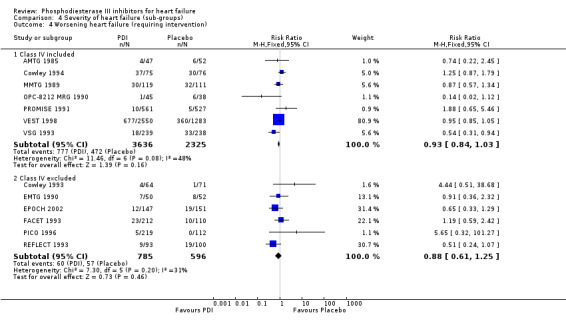

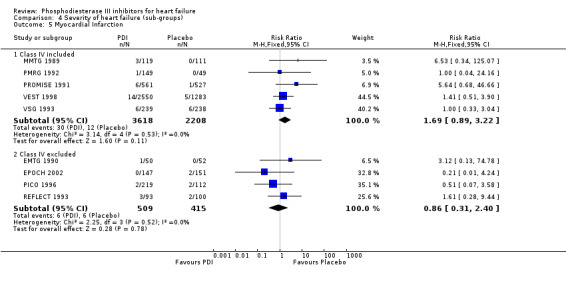

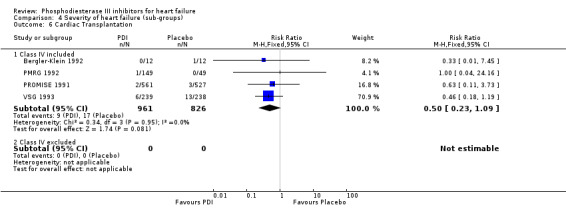

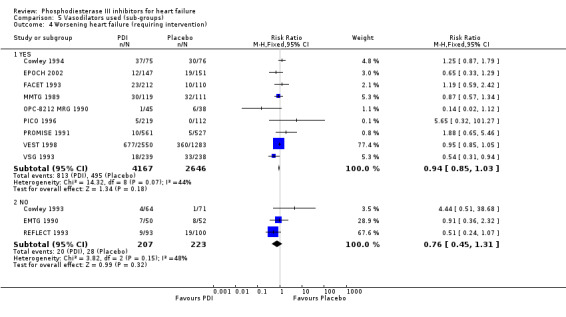

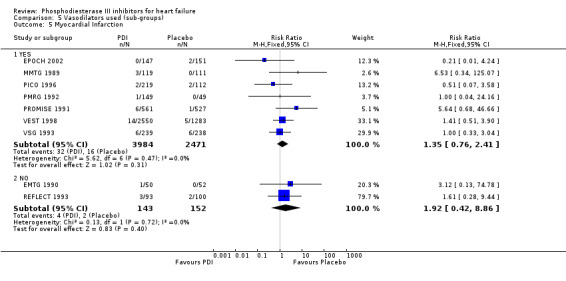

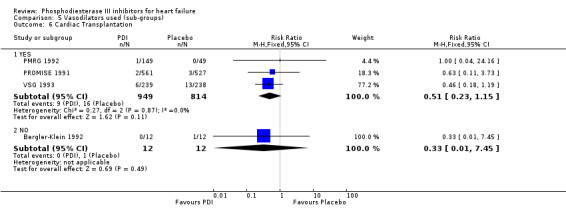

We identified a non significant decrease of worsening of heart failure with relative risk 0.93 (95% confidence interval 0.84 to 1.02; p=0.12) and cardiac transplantation with relative risk 0.50 (95% confidence interval 0.23 to 1.09; p=0.08). There was a non significant increase in myocardial infarction with relative risk 1.41 (95% confidence interval 0.82 to 2.43; p=0.21). Considering mortality from all causes, the deleterious effect of PDIs appeard homogeneous for the concomitant use or not of vasodilating agents, the severity of heart failure, the molecule or the derivative of PDI used (Table 5). No significant interaction was found.

5. Sub‐groups analysis for total mortality.

| Sub‐groups (SG) | Categories | Nb of trials | Nb of patients | RR (95% CI) | p‐hetero between SG |

| Molecule type | Amrinone | 1 | 99 | 1.105 (0.182 to 6.785) | 0.92 |

| Enoximone | 5 | 565 | 1.416 (0.953 to 2.105) | ||

| Flosequinan | 4 | 961 | 1.408 (0.771 to 2.570) | ||

| Imazodan | 1 | 147 | 1.091 (0.318 to 3.751) | ||

| Indolidan | 1 | 74 | 1.369 (0.266 to 7.048) | ||

| Milrinone | 2 | 1318 | 1.292 (1.065 to 1.567) | ||

| PImobendan | 4 | 851 | 1.331 (0.776 to 2.282) | ||

| Vesnarinone | 3 | 4393 | 1.086 (0.953 to 1.238) | ||

| Derivative | Imidazolone | 5 | 565 | 1.416 (0.953 to 2.105) | 0.47 |

| Pyridazinone | 10 | 2033 | 1.347 (0.926 to 1.957) | ||

| Pyridinone | 3 | 1417 | 1.289 (1.064 to 1.562) | ||

| Quinolinone | 3 | 4393 | 1.086 (0.953 to 1.238) | ||

| Severity of CHF | Class IV included | 10 | 6617 | 1.153 (1.038 to 1.280) | 0.33 |

| Class IV excluded | 10 | 1748 | 1.467 (1.005 to 1.301) | ||

| Vasodilator used | YES | 13 | 7337 | 1.157 (1.044 to 1.282) | 0.31 |

| NO | 7 | 972 | 1.669 (0.978 to 2.847) |

Sensitivity analysis

The substitution of a fixed effects model for a random effects model did not change our initial qualitative interpretation of the pooled treatment deleterious effect on total mortality or cardiac death. After exclusion of the VEST 1998 trial (3833 patients and 802 deaths, i.e. 45.6% of all patients included in the trials of this meta‐analysis and 58.3% of the deaths occurring within all trials) the deleterious effect of PDI on total mortality remained significant : the relative risk was 1.19 (95% confidence interval 1.02 to 1.38; p=0.025). The funnel plot (Egger 1997) did not show any asymmetry i.e. tendency for a potential publication bias.

Sub‐group analyses

All sub‐groups analyses were specified a priori in the protocol for this systematic review. They were:

Molecule type: Amrinone, Pimobendan, Flosiquinan, Enoximone, Milrinone and Vesnarinone.

Derivative type: Imidizolone, Pyridizanone, Pyridinone, Quinolinone.

Severity of heart failure: People with Class IV heart failure (NYHA scale) included and People with class IV heart failure excluded.

Concomitant use of vasodilators or not.

These analyses are only exploratory to document the main effect of PDI on outcomes (Table 5). No statistical difference between sub‐groups has been observed for any outcome (no significant interaction was defined as p>0.05). Consequently, the effect of PDI was homogeneous between molecules, derivatives, severity of heart failure, and vasodilator use for all outcomes. It was not possible to explore effect of PDI according of the aetiology of heart failure (ischaemic and non‐ischaemic), since data were not available.

Discussion

Overall results

This meta‐analysis clearly shows evidence for a deleterious effect of orally administered PDIs given to patients presenting with overt chronic heart failure. This deleterious effect is consistent for all the considered endpoints: total mortality, mortality from cardiac origins, and sudden death. The level of evidence is high, according to the significant results of the two largest trials in the field (PROMISE 1991; VEST 1998). In addition, the results were homogeneous according to the severity of heart failure, the PDI derivative or the molecule used, and the concomitant use or non‐use of vasodilating agents.

Homogeneity of results

Considering total mortality, the borderline significant results of some homogeneity tests have to be discussed. As already mentioned, such an interaction may be related to the results of only one trial (VSG 1993). In this trial initiated in 1990, 577 patients with NYHA class III or IV heart failure were randomly assigned to receive placebo or 60 mg of vesnarinone daily for six months (some patients were assigned to 120 mg of vesnarinone but this part of the trial was stopped early). A remarkable and significant 62 percent reduction in mortality from all causes was observed in the vesnarinone treated group. However, these results were problematic for several reasons. First, the duration of the trial was short (six months) and the total number of events was small (46 deaths). Second, two vesnarinone regimens (60 and 120 mg daily) were studied and the higher‐dose regimen was discontinued early by the data and safety monitoring committee because of a trend toward an adverse effect on mortality. The contradiction between the results of this study and those of our meta‐analysis does not have any obvious explanation. Examination of the patient populations reveals no differences that could reasonably account for the opposite response to the daily administration of 60 mg of vesnarinone. In the trial of VEST 1998, the progressive increase in mortality from placebo to 30 mg and to 60 mg of vesnarinone per day (and when combined with the striking increase in mortality with a daily dose of 120 mg in the trial of VSG 1993) indicates a nearly linear adverse dose‐response effect of vesnarinone. Consequently, the trials assessing mortality or mortality and morbidity in patients with heart failure should have sufficient power with enough events and long enough follow‐up to ensure that the results reliably reflect the long term effects of the tested drug as compared with placebo.

Other methodological considerations

One major bias inherent to meta‐analysis is the iceberg phenomenon or file drawer problem due to unpublished trials (Rosenthal 1979). These trials usually have nonsignificant or "negative" results, whereas published trials often have significant results and this therefore is a potential source of bias in the analysis. Moreover, some studies have been performed purely for registration purposes and have never been published, often because pharmaceutical companies regard the results as confidential. Despite exhaustive searching, including screening conference proceedings and abstract books and contacting several investigators no additional studies could be identified. We have therefore attempted to minimise this publication bias.

The numerical data considered in our meta‐analysis have not yet been checked by all the investigators of the selected trials, so that some data extraction bias (e.g. in case of printing errors) cannot be completely excluded.

The selected trials were all double‐blind, placebo‐controlled, randomised studies. In meta‐analysis on trials in heart failure patients, it is not possible to take into consideration the unavoidable differences in the patients' baseline characteristics, such as the aetiology (ischaemic / non ischemic) of heart failure, or the duration of the heart disease before inclusion. The percentage of patients with ischemic heart disease probably differed from one trial to another, and the percentage of patients who died under placebo, which is an indirect measure of the severity of the heart failure, only varied from 0 to 24% (results extrapolated to 3 months of follow‐up). The actual follow‐up in the studies varied from 3 to 52 months, but the meta‐analytical approach assumes a constant therapeutic effect and a relative stability of the odds ratio over time. As no well‐defined a priori effect model exists for our problem, we used different meta‐analytical methods which involve summary statistics. These methods are based on a statistical model of the difference between treated and control patients, with the value of association being based either on a multiplicative effect (risk ratio or odds ratio) or an additive effect (rate or risk differences). Since different techniques applied to the same data set can yield different results in terms of the statistical significance of association, it is usually recommended to use more than one technique to ensure that only conservative conclusions are drawn (Tukey 1977). In doing so, we found no major differences between the results obtained with these methods.

Potential mechanisms of toxicity

The mechanism by which PDIs increase mortality in heart failure patients has not yet been fully elucidated. Intra cellular levels of cyclic AMP are decreased in the failing heart (Katz 1990), and this abnormality in cellular metabolism was the reason for using PDIs in heart failure. It now appears more plausible that the reduction in cyclic AMP levels in the failing heart may be an adaptive response that protects myocardial cells from further injury (EMTG 1990). Agents that increase levels of cyclic AMP could, therefore, be expected to be harmful, perhaps by enhancing ventricular arrhythmia, as has been suggested by the results of some experimental and clinical studies (Chesebro 1988; MMTG 1989; Packer 1984).

The potential toxicity of the association of a PDI and an additional vasodilator had to be explored both on an experimental and a physiological basis. Amrinone, through its inhibitory action on phosphodiesterase, not only increases the rate of relaxation of the myocardium but also produces relaxation in the smooth muscle of gut, bronchi and blood vessel wall (Wilmshurst 1984). The vasodilator properties of amrinone have been detected at concentrations lower than those at which positive inotropic effects have been detected in guinea pig myocardium. The improvement in left ventricular performance induced by amrinone in patients with heart failure appears to result, in part, from a decrease in peripheral vascular resistance (LeJemtel 1980). This effect is due to a direct vasodilator effect on the systemic vessel resistance, and to an indirect vasodilation, secondary to the withdrawal of enhanced sympathetic constrictor tone consequent to the improvement in cardiac performance. This is also true for milrinone (Colucci 1991; Simonton 1985), for which an intra coronary injection demonstrated the direct and indirect inotropic effects and confirmed the reduction of the sympathetic tone (by measurement of the heart rate and norepinephrine level), due to reflex withdrawal (Ludmer 1986). It has been estimated that only one‐third of milrinone's effect on pump function can be attributed to its direct myocardial action (Ludmer 1986). It has also be observed that intravenous enoximone produced hypotension in 3% of the patients treated for heart failure (Gilfrich 1991). Artery vasodilators are associated with a reduction in both systolic and diastolic arterial pressure, and total systemic vascular and pulmonary vascular resistances (Mikulic 1977). Nevertheless, when arterial pressure falls to a dangerously low level during therapy, the irrigation of some ischaemic areas of myocardium may be altered. Hence, some of the potentiated effects of the PDI‐additional vasodilator combination offer possible benefits (Mancini 1985), whereas, the lowering of blood pressure with an increase of myocardial ischaemia can, in certain haemodynamic conditions, cause deleterious effects. Although clinical trials include in our meta‐analysis are not completely comparable, particularly in terms of exercise tolerance and haemodynamic effects during long term therapy (Hood 1989), we found that PDIs, with and without concomitant vasodilator, are responsible for an increase in mortality, compared with placebo, and thus concomitant vasodilator treatment cannot explain the deleterious effect of PDIs on survival.

Interaction between pathophysiology and clinical trials

Such results confirm the essential need for a constant interaction between pathophysiology and the results of clinical trials, in order to help in the understanding of the mechanism of action of drugs and the future development of new treatments. For PDIs, pathophysiology suggested first that the use of such agents could lead to clinical benefits in heart failure, but the results of the PROMISE study showed an increased total mortality under milrinone as compared to placebo. Then attention turned to the potential pathophysiological mechanisms of such deleterious effects : excessive increase in intracellular cyclic AMP, which decreases in chronic heart failure patients possibly as an adaptive response, or an arrhythmogenic effect. Vesnarinone was then developed and was supposed to be effective because of its multiple mechanisms of action : enhancement of contractility through ion‐channel effects that augment sodium‐calcium exchange, and inhibition of the production of cytokines. However, the last vesnarinone trial (VEST 1998) showed a dose‐related increase in mortality in response to the drug. Again, several pathophysiological explanations were proposed such as a direct proarrhythmic effect related to an accelerated structural remodeling of the ventricle, thus providing the substrate for ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation. But the effect of vesnarinone on ventricular volume in the patients included in this trial remains unknown. Such an example shows that the concepts useful for researchers (pathophysiological hypotheses) must be clearly differentiated from those useful to physicians (evidence‐based clinical data). In our opinion, the differences between these two ways of thinking should be made clearer in the fields of therapeutic information and "evidence based medicine" and especially during medical teaching (Nony 1999).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Our results confirm that people with chronic heart failure given orally administered PDIs have increased mortality rates compared with those given an inactive placebo. Currently available results do not support the hypothesis that the increased mortality rate is due to additional vasodilator treatment. The chronic use of PDIs should be avoided in heart failure patients.

Implications for research.

Alternative strategies for the use of PDIs in patients with chronic heart failure could be considered (e.g. a discontinuous treatment regimen for use only during periods of functional worsening), such strategies have first to be carefully evaluated in further randomised controlled trials with suitable duration of follow up, outcomes and power.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 29 November 2012 | Review declared as stable | This review is no longer being updated due to an increase in mortality demonstrated. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2000 Review first published: Issue 1, 2005

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 9 September 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 1 November 2004 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Notes

This review is no longer being updated because several trials and this meta‐analysis demonstrated an increase in mortality. Consequently, no additional clinical trial has been performed with phosphodiesterase III inhibitors in this indication.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Mrs. Rousselet for library assistance and Miss Gauthier for secretarial help. We also wish to thank J Brunelin and N Ouahdi for handsearching of abstracts.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search strategy

Appendix 2. MEDLINE search strategy

The computer search of the MEDLINE database (from 1966 to January 2004) was performed using the following specific terms: (1) (("controlled clinical trial"[Publication Type]) OR ("clinical trial") OR ("clinical trials") OR (random*) OR ("randomised controlled trial"[Publication Type])); (2) ("Phosphodiesterase Inhibitors"[Pharmacological Action]) OR ("Phosphodiesterase Inhibitors"[MeSH Terms]) OR (amrinone) OR (amrinon) OR (milrinone) OR (milrinon) OR (enoximone) OR (enoximon) OR (piroximone) OR (pimobendan) OR (imazodan) OR (sulmazole) OR (isomazole) OR (flosequinan) OR (indolidan) OR (quazinone) OR (adibendan) OR (pelrinone) OR (siguazodan) OR (cilostamide) OR (zardaverine) OR (alifedrine) OR (lixazinone); (3) ("Heart Failure, Congestive"[MeSH Terms]) OR ("heart failure") OR ("dilated cardiomyopathy") OR ("ventricular dysfunction") OR ("Ventricular Dysfunction"[MeSH Terms]) OR (cardiomyo*).

Appendix 3. EMBASE search strategy

The computer search of the EMBASE database (from 1980 to December 2003) was performed using the following specific terms : 1 exp heart failure/dt [drug therapy] (12588) 2 exp phosphodiesterase inhibitor/ct, ad, cm, dt [clinical trial, drug administration, drug comparison, drug therapy] (3606) 3 1 and 2 (1202) 4 3 (1202) 5 limit 4 to human (1135) 6 amrinone.mp. (1853) 7 milrinone.mp. (1836) 8 enoximone.mp. (965) 9 piroximone.mp. (229) 10 pimobendan.mp. (407) 11 imazodan.mp. (172) 12 sulmazole.mp. (407) 13 isomazole.mp. (69) 14 flosequinan.mp. (309) 15 indolidan.mp. (73) 16 quazinone.mp. (49) 17 adibendan.mp. (59) 18 pelrinone.mp. (17) 19 siguazodan.mp. (112) 20 cilostamide.mp. (157) 21 zardaverine.mp. (92) 22 alifedrine.mp. (20) 23 lixazinone.mp. (27) 24 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 (4556) 25 24 and 1 (1268) 26 25 and 5 (933) 27 25 or 5 (1470)

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Phosphodiesterase inhibitor vs Placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Total mortality | 21 | 8408 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.17 [1.06, 1.30] |

| 2 Cardiac death | 9 | 6708 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.16 [1.05, 1.30] |

| 3 Sudden death | 14 | 7463 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.30 [1.11, 1.52] |

| 4 Worsening heart failure (requiring intervention) | 13 | 7342 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.84, 1.02] |

| 5 Myocardial Infarction | 9 | 6750 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.41 [0.82, 2.43] |

| 6 Cardiac Transplantation | 4 | 1787 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.50 [0.23, 1.09] |

| 7 Arrhythmias | 13 | 3666 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [1.02, 1.54] |

| 8 Vertigo | 7 | 2216 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.81 [1.41, 2.33] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Phosphodiesterase inhibitor vs Placebo, Outcome 1 Total mortality.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Phosphodiesterase inhibitor vs Placebo, Outcome 2 Cardiac death.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Phosphodiesterase inhibitor vs Placebo, Outcome 3 Sudden death.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Phosphodiesterase inhibitor vs Placebo, Outcome 4 Worsening heart failure (requiring intervention).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Phosphodiesterase inhibitor vs Placebo, Outcome 5 Myocardial Infarction.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Phosphodiesterase inhibitor vs Placebo, Outcome 6 Cardiac Transplantation.

1.7. Analysis.

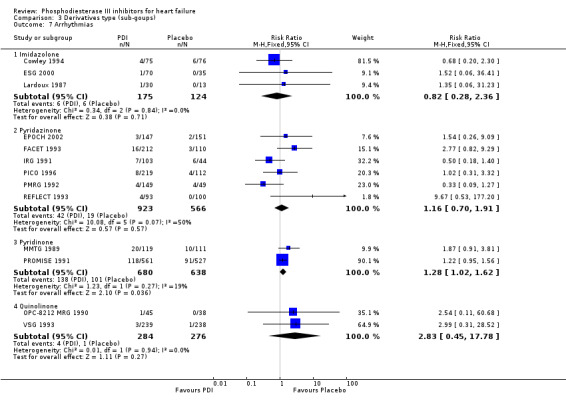

Comparison 1 Phosphodiesterase inhibitor vs Placebo, Outcome 7 Arrhythmias.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Phosphodiesterase inhibitor vs Placebo, Outcome 8 Vertigo.

Comparison 2. Molecule type (sub‐groups).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Total mortality | 21 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Amrinone | 1 | 99 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.11 [0.16, 7.55] |

| 1.2 Pimobendan | 4 | 851 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.32 [0.78, 2.26] |

| 1.3 Flosequinan | 4 | 961 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.41 [0.77, 2.57] |

| 1.4 Enoximone | 5 | 565 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.42 [0.95, 2.10] |

| 1.5 Indolidan | 1 | 74 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.42 [0.25, 8.02] |

| 1.6 Imazodan | 1 | 147 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.14 [0.32, 4.09] |

| 1.7 Milrinone | 2 | 1318 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.29 [1.07, 1.57] |

| 1.8 Vesnarinone | 3 | 4393 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.95, 1.24] |

| 2 Cardiac death | 9 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Pimobendan | 3 | 827 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.38 [0.78, 2.44] |

| 2.2 Enoximone | 2 | 253 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.77 [1.07, 2.92] |

| 2.3 Milrinone | 2 | 1318 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.33 [1.09, 1.62] |

| 2.4 Vesnarinone | 2 | 4310 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.92, 1.21] |

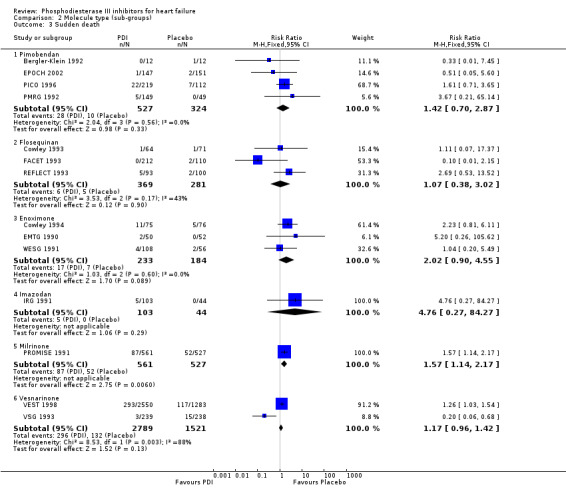

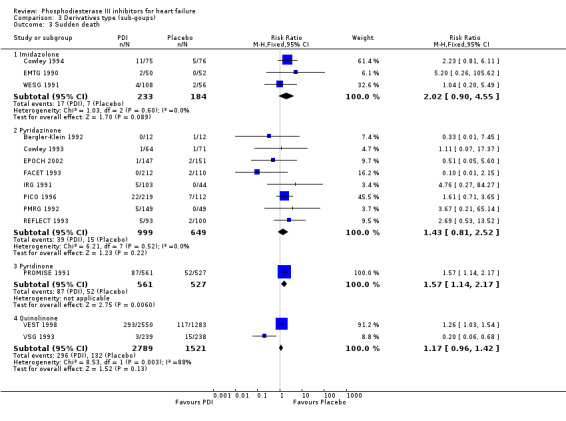

| 3 Sudden death | 14 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Pimobendan | 4 | 851 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.42 [0.70, 2.87] |

| 3.2 Flosequinan | 3 | 650 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.38, 3.02] |

| 3.3 Enoximone | 3 | 417 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.02 [0.90, 4.55] |

| 3.4 Imazodan | 1 | 147 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.76 [0.27, 84.27] |

| 3.5 Milrinone | 1 | 1088 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.57 [1.14, 2.17] |

| 3.6 Vesnarinone | 2 | 4310 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.17 [0.96, 1.42] |

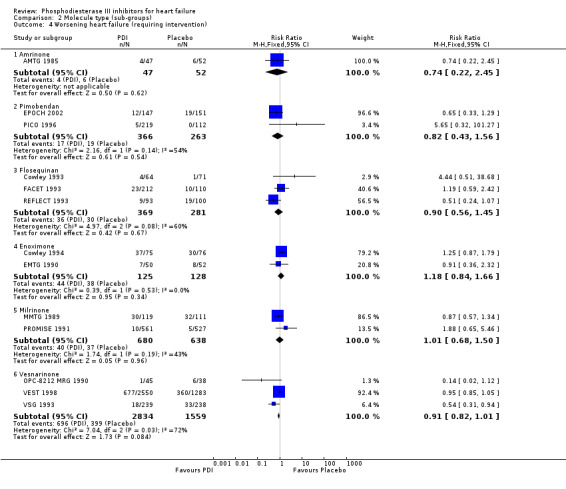

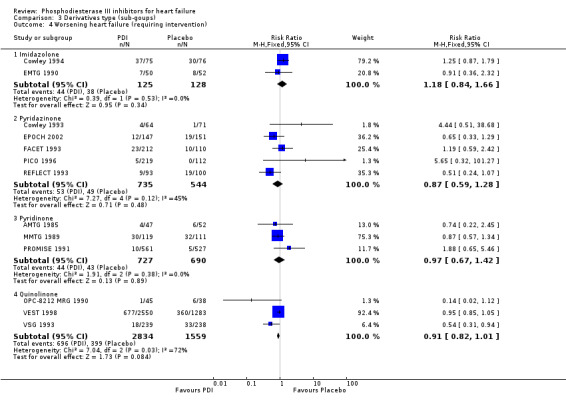

| 4 Worsening heart failure (requiring intervention) | 13 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Amrinone | 1 | 99 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.22, 2.45] |

| 4.2 Pimobendan | 2 | 629 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.43, 1.56] |

| 4.3 Flosequinan | 3 | 650 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.56, 1.45] |

| 4.4 Enoximone | 2 | 253 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.84, 1.66] |

| 4.5 Milrinone | 2 | 1318 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.68, 1.50] |

| 4.6 Vesnarinone | 3 | 4393 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.82, 1.01] |

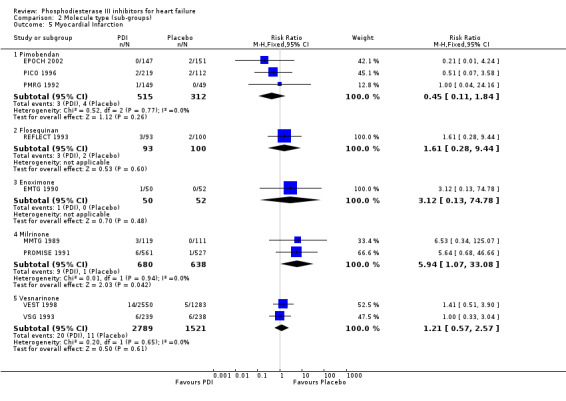

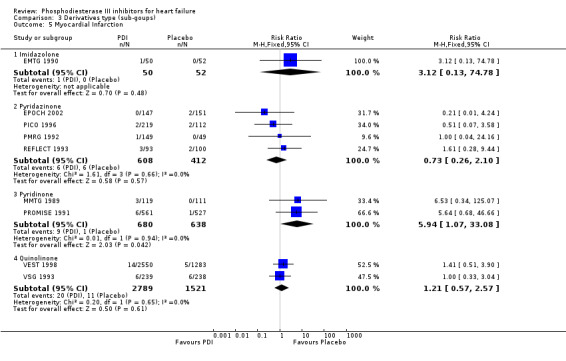

| 5 Myocardial Infarction | 9 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 Pimobendan | 3 | 827 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.45 [0.11, 1.84] |

| 5.2 Flosequinan | 1 | 193 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.61 [0.28, 9.44] |

| 5.3 Enoximone | 1 | 102 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.12 [0.13, 74.78] |

| 5.4 Milrinone | 2 | 1318 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.94 [1.07, 33.08] |

| 5.5 Vesnarinone | 2 | 4310 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.21 [0.57, 2.57] |

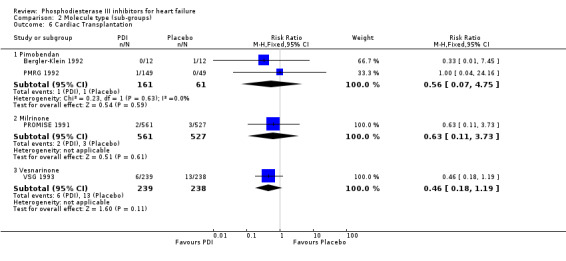

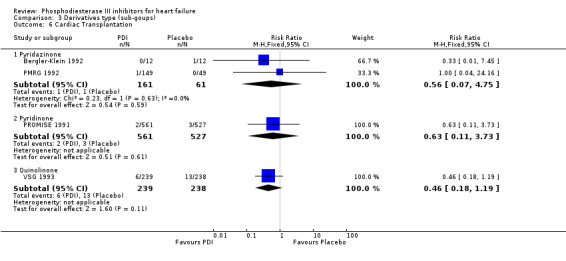

| 6 Cardiac Transplantation | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 Pimobendan | 2 | 222 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.56 [0.07, 4.75] |

| 6.2 Milrinone | 1 | 1088 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.11, 3.73] |

| 6.3 Vesnarinone | 1 | 477 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.46 [0.18, 1.19] |

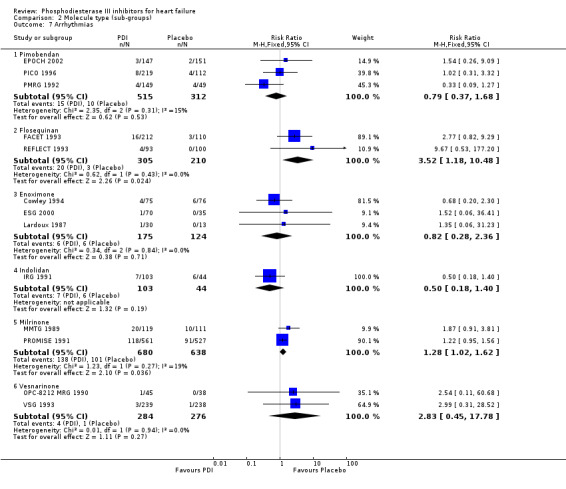

| 7 Arrhythmias | 13 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7.1 Pimobendan | 3 | 827 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.37, 1.68] |

| 7.2 Flosequinan | 2 | 515 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.52 [1.18, 10.48] |

| 7.3 Enoximone | 3 | 299 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.28, 2.36] |

| 7.4 Indolidan | 1 | 147 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.50 [0.18, 1.40] |

| 7.5 Milrinone | 2 | 1318 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.28 [1.02, 1.62] |

| 7.6 Vesnarinone | 2 | 560 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.83 [0.45, 17.78] |

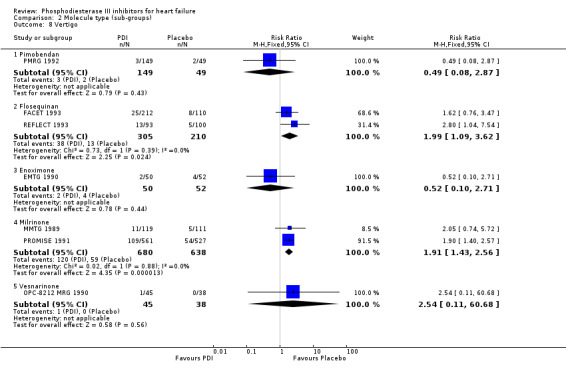

| 8 Vertigo | 7 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 8.1 Pimobendan | 1 | 198 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.49 [0.08, 2.87] |

| 8.2 Flosequinan | 2 | 515 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.99 [1.09, 3.62] |

| 8.3 Enoximone | 1 | 102 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.52 [0.10, 2.71] |

| 8.4 Milrinone | 2 | 1318 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.91 [1.43, 2.56] |

| 8.5 Vesnarinone | 1 | 83 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.54 [0.11, 60.68] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Molecule type (sub‐groups), Outcome 1 Total mortality.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Molecule type (sub‐groups), Outcome 2 Cardiac death.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Molecule type (sub‐groups), Outcome 3 Sudden death.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Molecule type (sub‐groups), Outcome 4 Worsening heart failure (requiring intervention).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Molecule type (sub‐groups), Outcome 5 Myocardial Infarction.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Molecule type (sub‐groups), Outcome 6 Cardiac Transplantation.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Molecule type (sub‐groups), Outcome 7 Arrhythmias.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Molecule type (sub‐groups), Outcome 8 Vertigo.

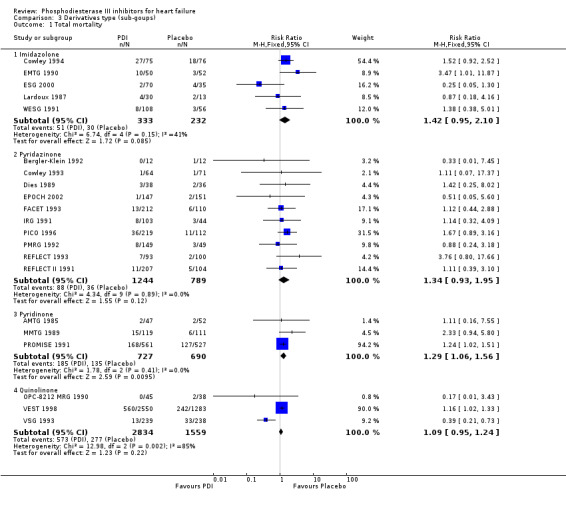

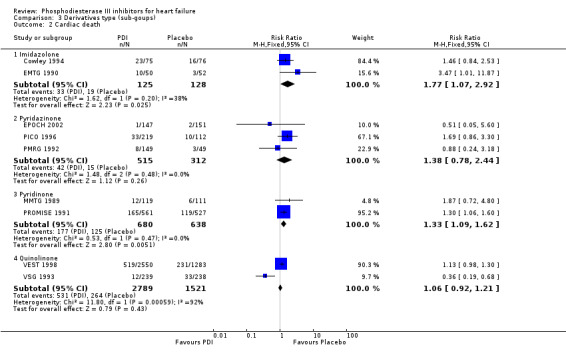

Comparison 3. Derivatives type (sub‐goups).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Total mortality | 21 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Imidazolone | 5 | 565 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.42 [0.95, 2.10] |

| 1.2 Pyridazinone | 10 | 2033 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.34 [0.93, 1.95] |

| 1.3 Pyridinone | 3 | 1417 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.29 [1.06, 1.56] |

| 1.4 Quinolinone | 3 | 4393 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.95, 1.24] |

| 2 Cardiac death | 9 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Imidazolone | 2 | 253 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.77 [1.07, 2.92] |

| 2.2 Pyridazinone | 3 | 827 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.38 [0.78, 2.44] |

| 2.3 Pyridinone | 2 | 1318 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.33 [1.09, 1.62] |

| 2.4 Quinolinone | 2 | 4310 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.06 [0.92, 1.21] |

| 3 Sudden death | 14 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Imidazolone | 3 | 417 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.02 [0.90, 4.55] |

| 3.2 Pyridazinone | 8 | 1648 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.43 [0.81, 2.52] |

| 3.3 Pyridinone | 1 | 1088 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.57 [1.14, 2.17] |

| 3.4 Quinolinone | 2 | 4310 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.17 [0.96, 1.42] |

| 4 Worsening heart failure (requiring intervention) | 13 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Imidazolone | 2 | 253 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.84, 1.66] |

| 4.2 Pyridazinone | 5 | 1279 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.59, 1.28] |

| 4.3 Pyridinone | 3 | 1417 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.97 [0.67, 1.42] |

| 4.4 Quinolinone | 3 | 4393 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.91 [0.82, 1.01] |

| 5 Myocardial Infarction | 9 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 Imidazolone | 1 | 102 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.12 [0.13, 74.78] |

| 5.2 Pyridazinone | 4 | 1020 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.26, 2.10] |

| 5.3 Pyridinone | 2 | 1318 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.94 [1.07, 33.08] |

| 5.4 Quinolinone | 2 | 4310 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.21 [0.57, 2.57] |

| 6 Cardiac Transplantation | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 Pyridazinone | 2 | 222 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.56 [0.07, 4.75] |

| 6.2 Pyridinone | 1 | 1088 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.11, 3.73] |

| 6.3 Quinolinone | 1 | 477 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.46 [0.18, 1.19] |

| 7 Arrhythmias | 13 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7.1 Imidazolone | 3 | 299 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.28, 2.36] |

| 7.2 Pyridazinone | 6 | 1489 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.16 [0.70, 1.91] |

| 7.3 Pyridinone | 2 | 1318 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.28 [1.02, 1.62] |

| 7.4 Quinolinone | 2 | 560 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.83 [0.45, 17.78] |

| 8 Vertigo | 7 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 8.1 Imidazolone | 1 | 102 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.52 [0.10, 2.71] |

| 8.2 Pyridazinone | 3 | 713 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.74 [1.00, 3.04] |

| 8.3 Pyridinone | 2 | 1318 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.91 [1.43, 2.56] |

| 8.4 Quinolinone | 1 | 83 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.54 [0.11, 60.68] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Derivatives type (sub‐goups), Outcome 1 Total mortality.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Derivatives type (sub‐goups), Outcome 2 Cardiac death.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Derivatives type (sub‐goups), Outcome 3 Sudden death.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Derivatives type (sub‐goups), Outcome 4 Worsening heart failure (requiring intervention).

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Derivatives type (sub‐goups), Outcome 5 Myocardial Infarction.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Derivatives type (sub‐goups), Outcome 6 Cardiac Transplantation.

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Derivatives type (sub‐goups), Outcome 7 Arrhythmias.

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Derivatives type (sub‐goups), Outcome 8 Vertigo.

Comparison 4. Severity of heart failure (sub‐groups).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Total mortality | 20 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Class IV included | 10 | 6617 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.15 [1.04, 1.28] |

| 1.2 Class IV excluded | 10 | 1748 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.46 [1.00, 2.13] |

| 2 Cardiac death | 9 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Class IV included | 6 | 5977 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.14 [1.02, 1.27] |

| 2.2 Class IV included | 3 | 731 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.85 [1.06, 3.23] |

| 3 Sudden death | 14 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Class IV included | 6 | 5894 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.30 [1.10, 1.54] |

| 3.2 Class IV excluded | 8 | 1569 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.28 [0.74, 2.22] |

| 4 Worsening heart failure (requiring intervention) | 13 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Class IV included | 7 | 5961 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.93 [0.84, 1.03] |

| 4.2 Class IV excluded | 6 | 1381 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.88 [0.61, 1.25] |

| 5 Myocardial Infarction | 9 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 Class IV included | 5 | 5826 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.69 [0.89, 3.22] |

| 5.2 Class IV excluded | 4 | 924 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.31, 2.40] |

| 6 Cardiac Transplantation | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 Class IV included | 4 | 1787 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.50 [0.23, 1.09] |

| 6.2 Class IV excluded | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 7 Arrhythmias | 13 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7.1 Class IV included | 13 | 3666 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [1.02, 1.54] |

| 7.2 Class IV excluded | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8 Vertigo | 7 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 8.1 Class IV included | 7 | 2216 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.81 [1.41, 2.33] |

| 8.2 Class IV excluded | 0 | 0 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Severity of heart failure (sub‐groups), Outcome 1 Total mortality.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Severity of heart failure (sub‐groups), Outcome 2 Cardiac death.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Severity of heart failure (sub‐groups), Outcome 3 Sudden death.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Severity of heart failure (sub‐groups), Outcome 4 Worsening heart failure (requiring intervention).

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Severity of heart failure (sub‐groups), Outcome 5 Myocardial Infarction.

4.6. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Severity of heart failure (sub‐groups), Outcome 6 Cardiac Transplantation.

4.7. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Severity of heart failure (sub‐groups), Outcome 7 Arrhythmias.

4.8. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Severity of heart failure (sub‐groups), Outcome 8 Vertigo.

Comparison 5. Vasodilators used (sub‐groups).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Total mortality | 20 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 YES | 13 | 7337 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.16 [1.04, 1.28] |

| 1.2 NO | 7 | 972 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.65 [0.97, 2.80] |

| 2 Cardiac death | 9 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 YES | 8 | 6606 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.15 [1.03, 1.28] |

| 2.2 NO | 1 | 102 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.47 [1.01, 11.87] |

| 3 Sudden death | 14 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 YES | 9 | 6845 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.29 [1.10, 1.52] |

| 3.2 NO | 5 | 618 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.60 [0.65, 3.92] |

| 4 Worsening heart failure (requiring intervention) | 12 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 YES | 9 | 6813 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.94 [0.85, 1.03] |

| 4.2 NO | 3 | 430 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.76 [0.45, 1.31] |

| 5 Myocardial Infarction | 9 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 YES | 7 | 6455 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.35 [0.76, 2.41] |

| 5.2 NO | 2 | 295 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.92 [0.42, 8.86] |

| 6 Cardiac Transplantation | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 YES | 3 | 1763 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.51 [0.23, 1.15] |

| 6.2 NO | 1 | 24 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.33 [0.01, 7.45] |

| 7 Arrhythmias | 13 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7.1 YES | 11 | 3430 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.22 [0.99, 1.50] |

| 7.2 NO | 2 | 236 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.78 [0.67, 34.14] |

| 8 Vertigo | 7 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 8.1 YES | 5 | 1921 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.82 [1.39, 2.37] |

| 8.2 NO | 2 | 295 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.77 [0.80, 3.93] |

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Vasodilators used (sub‐groups), Outcome 1 Total mortality.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Vasodilators used (sub‐groups), Outcome 2 Cardiac death.

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Vasodilators used (sub‐groups), Outcome 3 Sudden death.

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Vasodilators used (sub‐groups), Outcome 4 Worsening heart failure (requiring intervention).

5.5. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Vasodilators used (sub‐groups), Outcome 5 Myocardial Infarction.

5.6. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Vasodilators used (sub‐groups), Outcome 6 Cardiac Transplantation.

5.7. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Vasodilators used (sub‐groups), Outcome 7 Arrhythmias.

5.8. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Vasodilators used (sub‐groups), Outcome 8 Vertigo.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

AMTG 1985.

| Methods | Double‐blinded placebo controlled randomised trial. Two groups of patients were recruited, one with concomitant vasodilator (group 1) and one without (group 2). Within each group patients were randomised between PDI or placebo. Follow‐up: 3 months. | |

| Participants | Severity of heart failure (NYHA class) III, IV. Group 1: No. of patients (treated/placebo) 15 / 16. Group 2: No. of patients (treated/placebo) 32 / 36. | |

| Interventions | Amrinone. Dose per day < 600 mg | |

| Outcomes | Changes in symptoms and NYHA classification, exercise tolerance, ejection fraction. Deaths, withdrawals due to treatment failure, adverse reactions. | |

| Notes | No primary outcome specified | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Bergler‐Klein 1992.

| Methods | Double blinded placebo controlled randomised trial. No concomitant vasodilator. Follow‐up: 6 months. | |

| Participants | Severity of heart failure (NYHA class) II, III. No. of patients (treated/placebo) 12 / 12. | |

| Interventions | Pimobendan. Dose per day: 10 mg | |

| Outcomes | Changes in NYHA classification, arrhythmias, cardiothoracic ratio, ejection fraction, clinical events | |

| Notes | No primary outcome specified. Trial only published in german | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Cowley 1993.

| Methods | Double blinded placebo controlled randomised trial. No concomitant vasodilator . Follow‐up: 4 months. | |

| Participants | Severity of heart failure (NYHA class) II, III. No. of patients (treated/placebo) 64 / 71. | |

| Interventions | Flosequinan. Dose per day: 125 mg | |

| Outcomes | ‐ Primary: Exercise tolerance. ‐ Secondary: Changes in NYHA classification, quality of life score. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Cowley 1994.

| Methods | Double blinded placebo controlled randomised trial. With concomitant vasodilator . Follow‐up: 12 months. | |

| Participants | Severity of heart failure (NYHA class) III, IV. No. of patients (treated/placebo) 75 / 76. | |

| Interventions | Enoximone. Dose per day: 300 mg. | |

| Outcomes | ‐ Primary: Total mortality ‐ Secondary: Quality of life score, hospitalisation. | |

| Notes | The trial was stopped early because of an excess of mortality in the patients treated with enoximone. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Dies 1989.

| Methods | Placebo controlled randomised trial. Blinding not stated With concomitant vasodilator. Follow‐up: 3 months. | |

| Participants | Severity of heart failure (NYHA class) II, III. No. of patients (treated/placebo) 38 / 36. | |

| Interventions | Indolidan. Data on dose not available | |

| Outcomes | Changes in symptoms and NYHA classification, ejection fraction, cardiothoracic ratio, total mortality, withdrawals, adverse reactions. | |

| Notes | Only published in an abstract. No primary outcome specified. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

EMTG 1990.

| Methods | Double blinded placebo controlled randomised trial. No concomitant vasodilator. Follow‐up: 4 months. | |

| Participants | Severity of heart failure (NYHA class) II, III. No. of patients (treated/placebo) 50 / 52. | |

| Interventions | Enoximone. Dose per day < 450 mg | |

| Outcomes | Changes in symptoms and NYHA classification, exercise tolerance, patient's daily activity score. Severity of symptoms, hospitalisation, ejection fraction, withdrawals, adverse reactions. | |

| Notes | No primary outcome specified. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

EPOCH 2002.

| Methods | Double blinded placebo controlled randomised trial. With concomitant vasodilator. Follow‐up: 12 months. | |

| Participants | Severity of heart failure (NYHA class) II, III. No. of patients (treated/placebo) 147 / 151. | |

| Interventions | Pimobendan. Dose per day 2.5 to 5 mg | |

| Outcomes | ‐ Primary: Adverse cardiac events (combined endpoint: death from heart failure, sudden death or hospitalisation for worsening heart failure) ‐ Secondary: Quality of life score, modification of treatment, death from other cardiac causes, death from non‐cardiac causes, changes in NYHA classification, ejection fraction. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

ESG 2000.

| Methods | Double blinded placebo controlled randomised trial. With concomitant vasodilator. Follow‐up: 3 months. | |

| Participants | Severity of heart failure (NYHA class) II, III. No. of patients (treated/placebo) 70 / 35. | |

| Interventions | Enoximone. Dose per day 75, 150 mg. | |

| Outcomes | ‐ Primary: Exercise tolerance ‐ Secondary: Adverse events, quality of life score, arrhythmias. | |

| Notes | Results presented for the first time in 1991. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

FACET 1993.

| Methods | Double blinded placebo controlled randomised trial. With concomitant vasodilator. Follow‐up: 4 months. | |

| Participants | Severity of heart failure (NYHA class) II, III. No. of patients (treated/placebo) 212 / 110. | |

| Interventions | Flosequinan. Dose per day 100, 150 mg | |

| Outcomes | ‐ Primary: Exercise tolerance. ‐ Secondary: Quality of life score, hospitalisation, hospitalisation for worsening heart failure, adverse events. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

IRG 1991.

| Methods | Double blinded placebo controlled randomised trial. With concomitant vasodilator. Follow‐up: 3 months. | |

| Participants | Severity of heart failure (NYHA class) III, IV. No. patients (treated/placebo) 103 / 44. | |

| Interventions | Imazodan. Dose per day 4, 10, 20 mg | |

| Outcomes | ‐ Primary: Exercise tolerance. ‐ Secondary: Arrhythmias, total mortality. | |

| Notes | This trial was stopped early after an analysis indicated that a positive effect was unlikely to be achieved. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

Lardoux 1987.

| Methods | Double blinded placebo controlled randomised trial. No concomitant vasodilator. Follow‐up: 3 months. | |

| Participants | Severity of heart failure (NYHA class) not known. No. patients (treated/placebo) 30 / 13. | |

| Interventions | Enoximone. Dose per day: 150; 300 mg. | |

| Outcomes | Changes in NYHA classification, exercise tolerance, ejection fraction, total mortality. | |

| Notes | Only published in an abstract. No primary outcome specified. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

MMTG 1989.

| Methods | Double blinded placebo controlled randomised trial. No concomitant vasodilator . Follow‐up: 3 months. | |

| Participants | Severity of heart failure (NYHA class) II, III, IV. No. of patients (treated/placebo) 119 / 111. | |

| Interventions | Milrinone. Dose per day < 40 mg. | |

| Outcomes | Exercise tolerance, the need for cointervention for worsened heart failure, ejection fraction, total mortality, arrhythmias, adverse drug effects. | |

| Notes | No primary outcome specified | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

OPC‐8212 MRG 1990.

| Methods | Double blinded placebo controlled randomised trial. With concomitant vasodilator. Follow‐up: 3 months. | |

| Participants | Severity of heart failure (NYHA class) II, III, IV. No. of patients (treated/placebo) 45 / 38. | |

| Interventions | Vesnarinone. Dose per day: 60 mg. | |

| Outcomes | Quality of life score, withdrawals, changes in NYHA classification, cardiothoracic ratio, ejection fraction, total mortality | |

| Notes | No primary outcome specified | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

PICO 1996.

| Methods | Double blinded placebo controlled randomised trial. With concomitant vasodilator. Follow‐up: 6 months. | |

| Participants | Severity of heart failure (NYHA class) II, III. No. of patients (treated/placebo) 219 / 112. | |

| Interventions | Pimobendan. Dose per day 2.5, 5 mg. | |

| Outcomes | ‐ Primary: Exercise tolerance ‐ Secondary: total mortality, death or hospitalisation for cardiovascular cause, arrhythmias. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

PMRG 1992.

| Methods | Double blinded placebo controlled randomised trial. With concomitant vasodilator. Follow‐up: 3 months. | |

| Participants | Severity of heart failure (NYHA class) III, IV. No. patients(treated/placebo) 149 / 49. | |

| Interventions | Pimobendan. Dose per day 2.5, 5, 10 mg. | |

| Outcomes | ‐ Primary: Exercise tolerance, quality of life score, drug safety (arrhythmias and clinical adverse events). | |

| Notes | More than one primary outcome | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

PROMISE 1991.

| Methods | Double blinded placebo controlled randomised trial. With concomitant vasodilator. Follow‐up: 20 months | |

| Participants | Severity of heart failure (NYHA class) III, IV. No. of patients (treated/placebo) 561 / 527. | |

| Interventions | Milrinone. Dose per day 40 mg. | |

| Outcomes | ‐ Primary: Total mortality ‐ Secondary: Cardiovascular mortality, hospitalisation for all causes, the need for cointervention for worsened heart failure, adverse events. | |

| Notes | The trial was stopped early because of an excess of mortality in the patients treated with milrinone. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

REFLECT 1993.

| Methods | Double blinded placebo controlled randomised trial. No concomitant vasodilator. Follow‐up: 3 months. | |

| Participants | Severity of heart failure (NYHA class) II, III. No. of patients (treated/placebo) 93 / 100. | |

| Interventions | Flosequinan. Dose per day 100 mg. | |

| Outcomes | ‐ Primary: Exercise tolerance ‐ Secondary: Changes in symptoms, changes in NYHA classification, cardiothoracic ratio, ejection fraction, withdrawals, total mortality. | |

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | B ‐ Unclear |

REFLECT II 1991.

| Methods | Double blinded placebo controlled randomised trial. No concomitant vasodilator. Follow‐up: 3 months. | |