Abstract

Background

This is one of a series of reviews of methods of cervical ripening and labour induction using standardized methodology.

Objectives

To determine the effects of oral prostaglandin E2 for third trimester induction of labour.

Search methods

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register (January 2007) and bibliographies of relevant papers. We updated this search on 8 June 2012 and added the results to the awaiting classification section of the review.

Selection criteria

Clinical trials comparing oral prostaglandin E2 used for third trimester cervical ripening or labour induction with placebo or no treatment or other methods listed above it on a predefined list of labour induction methods.

Data collection and analysis

A strategy was developed to deal with the large volume and complexity of trial data relating to labour induction. This involved a two‐stage method of data extraction.

Main results

There were 19 studies included in the review. Of these 15 included a comparison using either oral or intravenous oxytocin with or without amniotomy. The quality of studies reviewed was not high. Only seven studies had clearly described allocation concealment. Only two studies stated that providers or participants, or both, were blinded to treatment group.

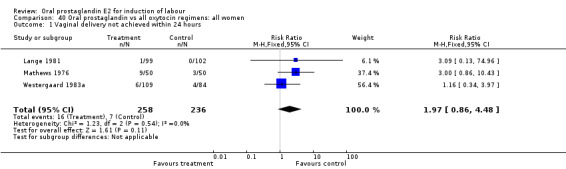

For the outcome of vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours, in the composite comparison of oral PGE2 versus all oxytocin treatments (oral and intravenous, with and without amniotomy), there was a trend favoring oxytocin treatments (relative risk (RR) 1.97, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.86 to 4.48).

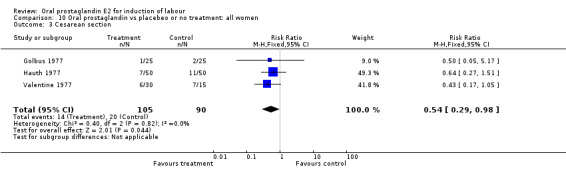

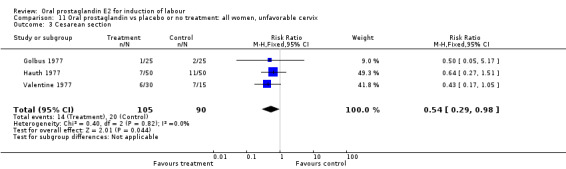

For the outcome of cesarean section, in the comparison of PGE2 versus no treatment or placebo, PGE2 was favored (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.98). Otherwise, there were no significant differences between groups for this outcome.

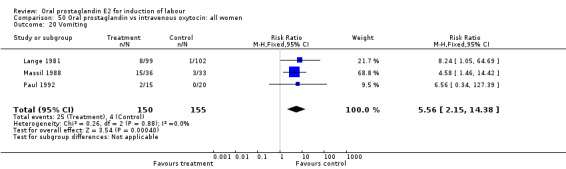

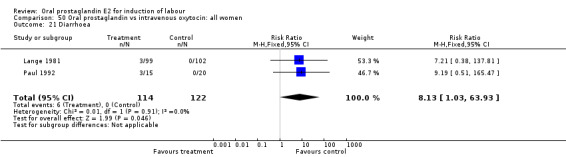

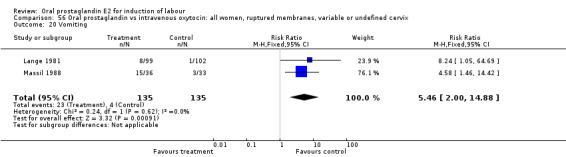

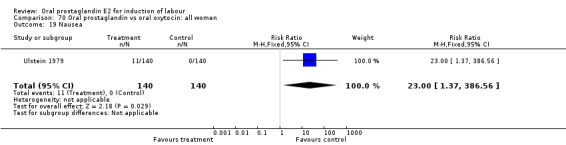

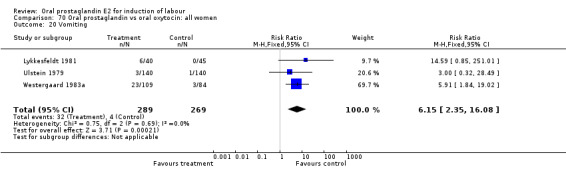

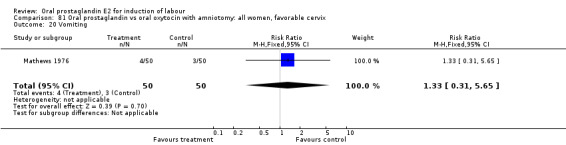

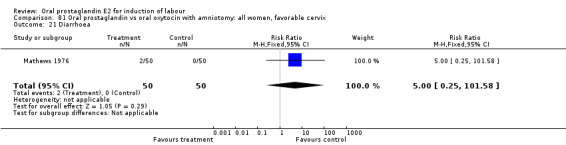

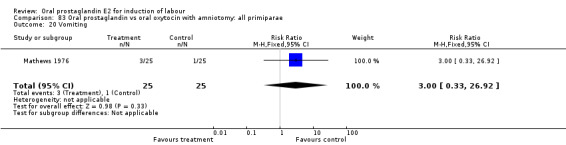

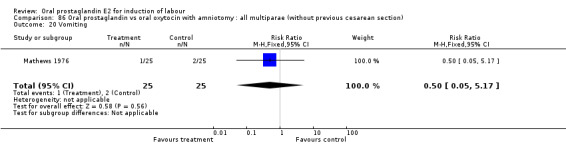

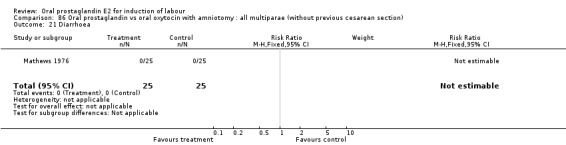

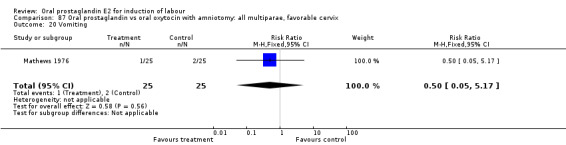

Oral prostaglandin was associated with vomiting across all comparison groups.

Authors' conclusions

Oral prostaglandin consistently resulted in more frequent gastrointestinal side‐effects, in particular vomiting, compared with the other treatments included in this review. There were no clear advantages to oral prostaglandin over other methods of induction of labour.

[Note: The six citations in the awaiting classification section of the review may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed.]

Keywords: Female; Humans; Pregnancy; Labor, Induced; Administration, Oral; Cervical Ripening; Dinoprostone; Dinoprostone/administration & dosage; Oxytocics; Oxytocics/administration & dosage; Pregnancy Trimester, Third

Plain language summary

Oral prostaglandin E2 for induction of labour

Oral prostaglandin E2 is no more effective than other methods of induction but has more adverse effects.

Induction of labour is sometimes considered beneficial in some clinical circumstances, e.g., when the baby is not growing properly, when there is pre‐eclampsia or when gestation goes beyond the normal length of pregnancy. There are many varying methods used to try to stimulate labour including administration of drugs, mechanical methods such as sweeping of the membranes, and more natural methods like nipple stimulation and having sex. Care needs to be taken to balance the stimulation of labour without over‐stimulating and causing the baby difficulties. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) is a hormone given either by mouth or by insertion through the vagina to prepare and stimulate the cervix and bring on labour. This review looked at oral PGE2 compared with no intervention, and compared with several other methods of induction. The review identified 19 studies involving 2688 women, looking at eight differing comparisons. The review found that none of the trials assessed the effectiveness of oral PGE2 in inducing labour, but overall the trials found that PGE2 caused more frequent gastrointestinal adverse effects, particularly vomiting. There were no clear advantages to oral PGE2 over other methods used to bring on labour, except that women may prefer a method that does not require an intravenous infusion. Over stimulation of the baby may possibly be a possible problem with PGE2, but the increased incidence of gastrointestinal side‐effects do not favor its use.

Background

Prostaglandins are hormones with a number of functions, and are normally produced at various sites in the body. They are derived from a fatty acid, arachidonic acid, which is generally available when needed. The role of endogenous prostaglandins in cervical ripening and initiation of labour was discovered in the 1960s.

Synthetically produced prostaglandins E2 (PGE2) and F2alpha (PGF2a) have been available for oral administration in several developed countries since the early 1970s. By 1977 five small trials had been published regarding use of PGE2 for cervical ripening. These were reviewed (Chalmers 1989) with the conclusion that the data failed to demonstrate suitability for this purpose. Vaginal administration has become the preferred route for the purpose of cervical ripening. PGE2 has also been studied as an agent for the induction of labour. The use of PGE2 as an agent for cervical ripening and labour induction is the subject of this review.

The gastrointestinal side‐effects of oral prostaglandins are important, and apparently more pronounced for PGF2a (Yeung 1977).

This review is one of a series of reviews of methods of labour induction using a standardized protocol. A review of the synthetic prostaglandin misoprostol is reviewed separately, seeAlfirevic 2006. For more detailed information on the rationale for this methodological approach, please refer to the currently published protocol (Hofmeyr 2000). For other currently published Cochrane Reviews on methods of induction of labour, seeAlfirevic 2006; Alfirevic 2009; Boulvain 2005; Boulvain 2008; Bricker 2000; Hapangama 2009; Hofmeyr 2010; Howarth 2001; Hutton 2001; Jozwiak 2012; Kavanagh 2001; Kavanagh 2005; Kavanagh 2006a; Kavanagh 2006b; Kelly 2001a; Kelly 2001b; Kelly 2009; Kelly 2011; Luckas 2000; Muzonzini 2004; Smith 2003; Smith 2004; Thomas 2001

Objectives

To determine, from the best available evidence, the effectiveness and safety of oral prostaglandin E2 for third trimester induction of labour.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Clinical trials comparing oral prostaglandin E2 for labour induction with placebo/no treatment or other methods of labour induction. This review includes only induction methods listed with lower numbers on a predefined list of methods of labour induction (see 'Methods of the review'). Studies comparing a low or constant dosing of oral prostaglandin with a high or incremental dosing regimen are also included. Additionally, studies comparing oral prostaglandin with oral oxytocin, with and without amniotomy, are also included. We have included only studies that have some form of random allocation of participants to study groups, and that report at least one of the prestated outcomes. Oral administration of the prostaglandin analogue misoprostol is reviewed separately (Alfirevic 2006).

Types of participants

Pregnant women due for third trimester induction of labour, carrying a viable fetus.

Predefined subgroup analyses were (see list below): previous cesarean section or not; nulliparity or multiparity; membranes intact or ruptured, and cervix unfavorable, favorable or undefined. Only those outcomes with data will appear in the analysis tables.

Types of interventions

Oral prostaglandin compared with placebo/no treatment or any other method above it on a predefined list of methods of labour induction.

Types of outcome measures

Clinically relevant outcomes for trials of methods of cervical ripening/labour induction have been prespecified by two authors of labour induction reviews (Justus Hofmeyr and Zarko Alfirevic). Differences were settled by discussion.

Five primary outcomes were chosen as being most representative of the clinically important measures of effectiveness and complications. Subgroup analyses are limited to the primary outcomes: (1) vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours; (2) uterine hyperstimulation with fetal heart rate (FHR) changes; (3) cesarean section; (4) serious neonatal morbidity or perinatal death (e.g. seizures, birth asphyxia defined by trialists, neonatal encephalopathy, disability in childhood); (5) serious maternal morbidity or death (e.g. uterine rupture, admission to intensive care unit, septicemia).

Perinatal and maternal morbidity and mortality are composite outcomes. This is not an ideal solution because some components are clearly less severe than others. It is possible for one intervention to cause more deaths but less severe morbidity. However, in the context of labour induction at term this is unlikely. All these events will be rare, and a modest change in their incidence will be easier to detect if composite outcomes are presented. The incidence of individual components will be explored as secondary outcomes (see below).

Secondary outcomes relate to measures of effectiveness, complications and satisfaction.

Measures of effectiveness:

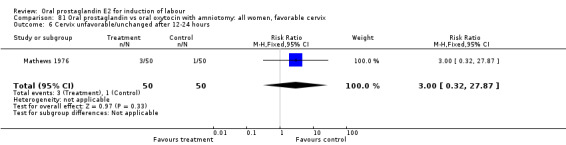

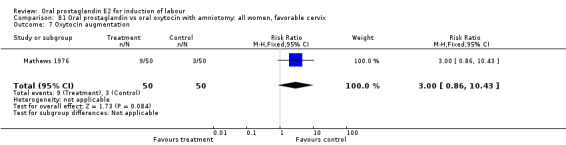

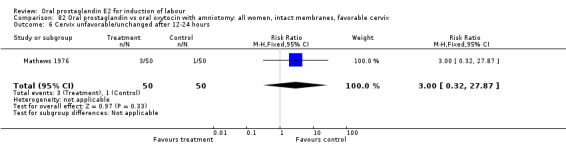

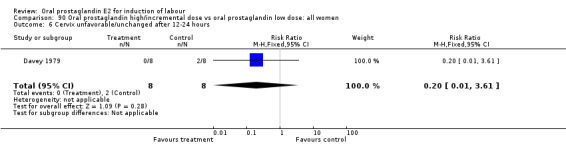

(6) cervix unfavorable/unchanged after 12 to 24 hours; (7) oxytocin augmentation.

Complications:

(8) uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes; (9) uterine rupture; (10) epidural analgesia; (11) instrumental vaginal delivery; (12) meconium stained liquor; (13) Apgar score less than seven at five minutes; (14) neonatal intensive care unit admission; (15) neonatal encephalopathy; (16) perinatal death; (17) disability in childhood; (18) maternal side‐effects (all); (19) maternal nausea; (20) maternal vomiting; (21) maternal diarrhoea; (22) other maternal side‐effects; (23) postpartum hemorrhage (as defined by the trial authors); (24) serious maternal complications (e.g. intensive care unit admission, septicemia but excluding uterine rupture); (25) maternal death.

Measures of satisfaction:

(26) woman not satisfied; (27) caregiver not satisfied.

'Uterine rupture' will include all clinically significant ruptures of unscarred or scarred uteri. Trivial scar dehiscence noted incidentally at the time of surgery will be excluded.

Additional outcomes may appear in individual primary reviews, but will not contribute to the secondary reviews.

While all the above outcomes will be sought, only those with data will appear in the analysis tables.

The terminology of uterine hyperstimulation is problematic (Curtis 1987). In the reviews we have used the term 'uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes' to include uterine tachysystole (more than 5 contractions per 10 minutes for at least 20 minutes) and uterine hypersystole/hypertonus (a contraction lasting at least two minutes) and 'uterine hyperstimulation with FHR changes' to denote uterine hyperstimulation syndrome (tachysystole or hypersystole with FHR changes such as persistent decelerations, tachycardia or decreased short‐term variability).

Outcomes were included in the analysis: if reasonable measures were taken to minimise observer bias; and data were available for analysis according to original allocation.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register by contacting the Trials Search Co‐ordinator (January 2007). We updated this search on 8 June 2012 and added the results to Studies awaiting classification.

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co‐ordinator and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

weekly searches of EMBASE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE and EMBASE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co‐ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

The first search was performed simultaneously for all reviews of methods of inducing labour, as outlined in the generic protocol for these reviews (Hofmeyr 2000).

Searching other resources

we searched the reference lists of trial reports and reviews.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

A strategy has been developed to deal with the large volume and complexity of trial data relating to labour induction. Many methods have been studied, in many different categories of women undergoing labour induction. Most trials are intervention‐driven, comparing two or more methods in various categories of women. Clinicians and parents need the data arranged by category of woman, to be able to choose which method is best for a particular clinical scenario. To extract these data from several hundred trial reports in a single step would be very difficult. We have therefore developed a two‐stage method of data extraction. The initial data extraction will be done in a series of primary reviews arranged by methods of induction of labour, following a standardized methodology. The data will then be extracted from the primary reviews into a series of secondary reviews, arranged by category of woman.

To avoid duplication of data in the primary reviews, the labour induction methods have been listed in a specific order, from one to 25. Each primary review includes comparisons between one of the methods (from two to 25) with only those methods above it on the list. Thus, the review of intravenous oxytocin (4) will include only comparisons with intracervical prostaglandins (3), vaginal prostaglandins (2) or placebo (1). Methods identified in the future will be added to the end of the list. The current list is as follows:

placebo/no treatment;

vaginal prostaglandins (Kelly 2009);

intracervical prostaglandins (Boulvain 2008);

intravenous oxytocin (Alfirevic 2009);

amniotomy (Bricker 2000);

amniotomy plus intravenous oxytocin (Howarth 2001);

vaginal misoprostol (Hofmeyr 2010);

oral misoprostol (Alfirevic 2006);

mechanical methods including extra‐amniotic Foley catheter (Jozwiak 2012);

membrane sweeping (Boulvain 2005);

extra‐amniotic prostaglandins (Hutton 2001);

intravenous prostaglandins (Luckas 2000);

oral prostaglandins (this review);

mifepristone (Hapangama 2009);

oestrogens alone of with amniotomy (Thomas 2001);

corticosteroids (Kavanagh 2006a);

relaxin (Kelly 2001b);

hyaluronidase (Kavanagh 2006b);

castor oil, bath and/or enema (Kelly 2001a);

acupuncture (Smith 2004);

breast stimulation (Kavanagh 2005);

sexual intercourse (Kavanagh 2001);

homeopathic methods (Smith 2003);

nitric oxide (Kelly 2011);

buccal or sublingual misoprostol (Muzonzini 2004);

hypnosis;

other methods for induction of labour.

The primary reviews are analysed by the following subgroups:

previous cesarean section or not;

nulliparity or multiparity;

membranes intact or ruptured;

cervix favorable, unfavorable or undefined.

The secondary reviews will include all methods of labour induction for each of the categories of women for which subgroup analysis has been done in the primary reviews, and will include only five primary outcome measures. There will thus be six secondary reviews of methods of labour induction in the following groups of women:

nulliparous, intact membranes (unfavorable cervix, favorable cervix, cervix not defined);

nulliparous, ruptured membranes (unfavorable cervix, favorable cervix, cervix not defined);

multiparous, intact membranes (unfavorable cervix, favorable cervix, cervix not defined);

multiparous, ruptured membranes (unfavorable cervix, favorable cervix, cervix not defined);

previous cesarean section, intact membranes (unfavorable cervix, favorable cervix, cervix not defined);

previous cesarean section, ruptured membranes (unfavorable cervix, favorable cervix, cervix not defined).

Each time a primary review is updated with new data, those secondary reviews which include data which have changed, will also be updated.

The trials included in the primary reviews first published in 2001 were extracted from an initial set of trials covering all interventions used in induction of labour (see above for details of search strategy). The data extraction process was conducted centrally. This was co‐ordinated from the Clinical Effectiveness Support Unit (CESU) at the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, UK, in co‐operation with the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group of The Cochrane Collaboration. This process allowed the data extraction process to be standardized across all the reviews.

The trials were initially reviewed on eligibility criteria, using a standardized form and the basic selection criteria specified above. Following this, data were extracted to a standardized data extraction form which was piloted for consistency and completeness. The pilot process involved the researchers at the CESU and previous review authors in the area of induction of labour.

Information was extracted regarding the methodological quality of trials on a number of levels. This process was completed without consideration of trial results. Assessment of selection bias examined the process involved in the generation of the random sequence and the method of allocation concealment separately. These were then judged as adequate or inadequate using the criteria described in Table 1 for the purpose of the reviews.

1. Methodological quality of trials.

| Methodological item | Adequate | Inadequate |

| Generation of random sequence. | Computer‐generated sequence, random‐number tables, lot drawing, coin tossing, shuffling cards, throwing dice. | Case number, date of birth, date of admission, alternation. |

| Concealment of allocation. | Central randomization, coded drug boxes, sequentially sealed opaque envelopes. | Open allocation sequence, any procedure based on inadequate generation. |

Performance bias was examined with regards to whom was blinded in the trials, i.e. woman, caregiver, outcome assessor or analyst. In many trials the caregiver, assessor and analyst were the same party. Details of the feasibility and appropriateness of blinding at all levels were sought.

Individual outcome data were included in the analysis if they met the prestated criteria in 'Types of outcome measures'. Included trial data were processed as described in The Cochrane Collaboration Handbook (Clarke 1999). Data extracted from the trials were analysed on an intention‐to‐treat basis (when this was not done in the original report, re‐analysis was performed if possible). Where data were missing, clarification was sought from the original authors. If the attrition was such that it might significantly affect the results, these data were excluded from the analysis. This decision rests with the review authors of primary reviews and has been clearly documented. Once missing data become available, they will be included in the analyses.

Data were extracted from all eligible trials to examine how issues of quality influence effect size in a sensitivity analysis. In trials where reporting is poor, methodological issues were reported as unclear or clarification sought.

Due to the large number of trials, double data extraction was not feasible and agreement between the three data extractors was therefore assessed on a random sample of trials.

Once the data had been extracted, they were distributed to individual review authors for entry onto the Review Manager computer software (RevMan 2003), checked for accuracy, and analysed as above using the RevMan software. For dichotomous data, relative risks and 95% confidence intervals were calculated, and in the absence of heterogeneity, results were pooled using a fixed‐effect model.

The predefined criteria for sensitivity analysis included all aspects of quality assessment as mentioned above, including aspects of selection, performance and attrition bias.

Primary analysis was limited to the prespecified outcomes and subgroup analyses. In the event of differences in unspecified outcomes or subgroups being found, these were analysed post hoc, but clearly identified as such to avoid drawing unjustified conclusions.

For this update, the additional reports identified from the updated search were assessed by one author.

Results

Description of studies

Excluded studies

There were 33 studies identified by the search strategy that were excluded. For details, see the table of 'Characteristics of excluded studies'. In four studies, allocation concealment was clearly inadequate due to randomization methods using alternation or odd or even medical record number. Six studies presented no outcomes of interest according to the review protocol. Six studies were not randomized trials. Two studies did not include oral prostaglandins. Two studies did not correspond to the topic of review, describing outcomes with policies of routine induction versus expectant management. One study was planned but not carried out. Insufficient data were available to assess the remainder.

Four studies were of two oral prostaglandin regimens that were considered too similar for meaningful comparison. Lorrain 1982 studied 'synthetic' versus 'natural' prostaglandin. Obel 1975 studied swallowed tablet versus oral solution. Thiery 1977 studied swallowed versus sublingual administration of tablets. In none of these studies was there any important difference described in outcomes. Davies 1991 used the same oral PGE2 regimen immediately versus the next morning at 9 a.m.

Somell 1983 considered both cervical ripening for two days and then induction with oral PGE2, compared with no treatment for ripening and intravenous (IV) oxytocin for induction. The combination comparison group (no treatment/IV oxytocin) is one not contemplated in the study protocol.

Included studies

There were 19 studies identified meeting the inclusion criteria. For details, see the table of 'Characteristics of included studies'. PGE2 was the oral prostaglandin used in all of these studies. The comparisons identified were:

oral PGE2 versus no treatment (n = three studies, 195 women);

oral PGE2 versus vaginal PGE2 (n = three studies, 108 women);

oral PGE2 versus cervical PGE2 (n = two studies, 80 women);

oral PGE2 versus IV oxytocin (n = seven studies, 779 women);

oral PGE2 versus IV oxytocin plus amniotomy (n = four studies, 435 women);

oral PGE2 versus oral oxytocin (n = four studies, 822 women);

oral PGE2 versus oral oxytocin plus amniotomy (n = two studies, 223 women);

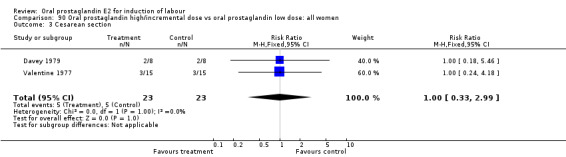

oral PGE2 dose incremental or high dose versus oral PGE2 constant or low dose (n = two studies, 46 women).

A few studies included multiple (three or four) comparison groups.

The study by Somell 1987 included four groups. The women were first divided into two groups to receive oral prostaglandin or placebo for cervical ripening. Afterward, these two groups were further divided into induction groups to receive either oral prostaglandin or IV oxytocin. For this review, only the two groups receiving oral PGE2 and IV oxytocin without prior cervical ripening are included.

There are six studies currently excluded which may be included at a future date if the authors can supply missing data.

(Six reports from an updated search on 8 June 2012 have been added to Studies awaiting classification.)

Risk of bias in included studies

Randomization

Mathews 1976, Paul 1992, Ratnam 1974, and Westergaard 1983 used sealed envelopes. Golbus 1977 and Somell 1987 described their studies as double‐blind comparisons to placebo and with implicit indication that allocation was concealed. Hauth 1977 stated that allocation was concealed, but did not describe the method. In all other studies allocation concealment was not mentioned. A table of random numbers for allocation was used by Beard 1975. For all other included studies the specific methodology of randomization was not described.

Blinding

Only for the two studies with a double‐blind comparison to placebo was blinding described. In the case of Somell 1987, it is assumed that the blinding only applied to the cervical ripening phase of the study, and not the induction portion versus intravenous oxytocin. Lack of blinding certainly introduces some possibility of bias, which could go in favor of any arm of the study that participating clinicians or women were inclined to believe was better.

Intent to treat

A minority of studies stated that analysis was on an intent‐to‐treat (ITT) basis (Beard 1975; Lange 1981; Massil 1988; Mathews 1976; Ulstein 1979; Westergaard 1983a). For studies in which ITT was not mentioned, it was assumed that there were no exclusions after enrolment unless specified. It was possible to analyze all included studied by ITT with that assumption.

Effects of interventions

Primary outcomes

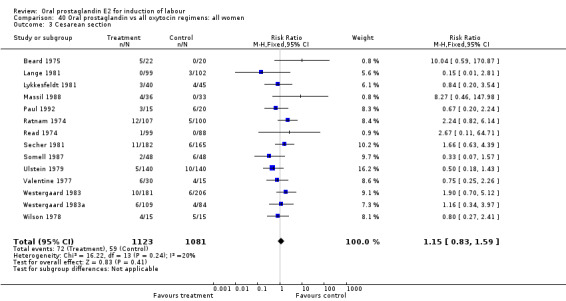

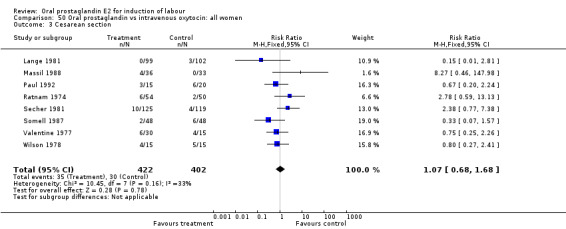

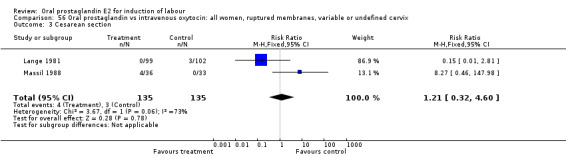

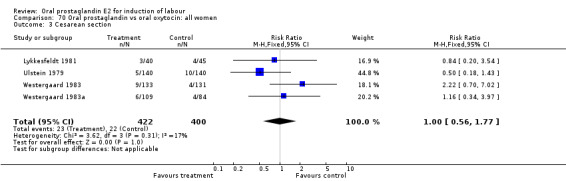

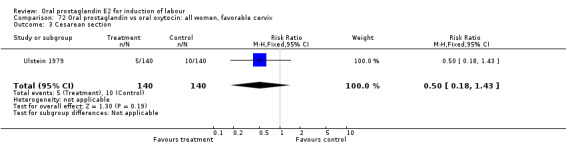

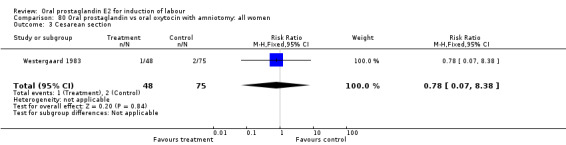

Of the five primary outcome measures, only cesarean section was consistently reported (in all but Mathews 1976). For the comparison versus no treatment or placebo, PGE2 was favored (relative risk (RR) 0.54, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.29 to 0.98). Otherwise, there were no significant differences between groups for this outcome.

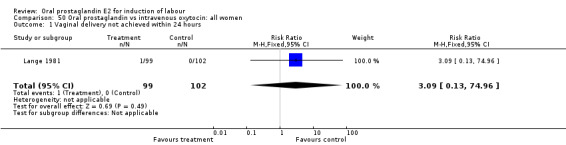

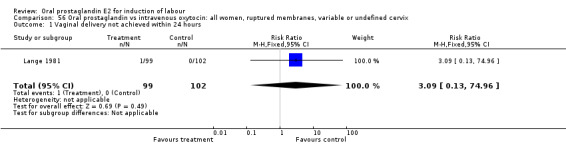

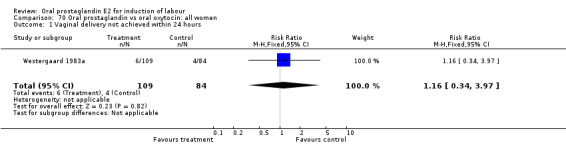

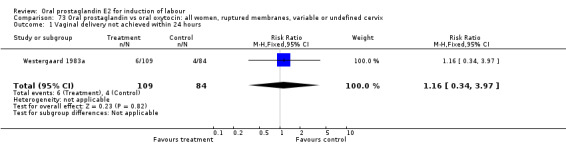

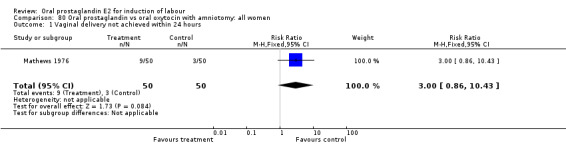

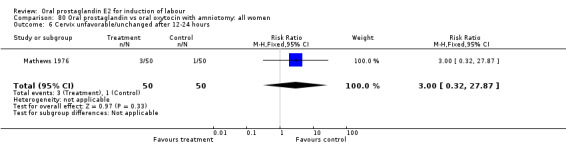

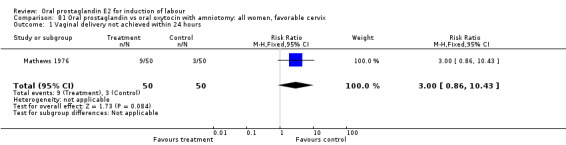

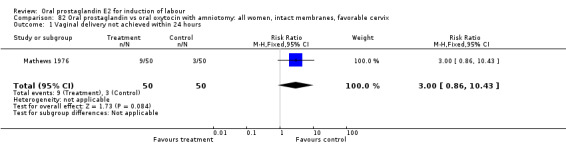

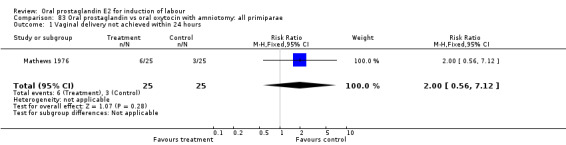

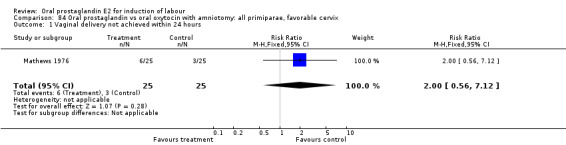

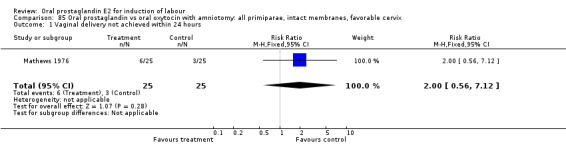

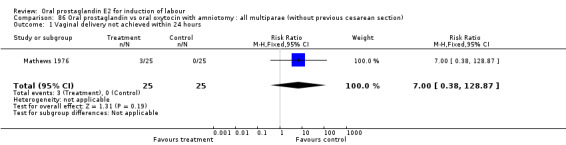

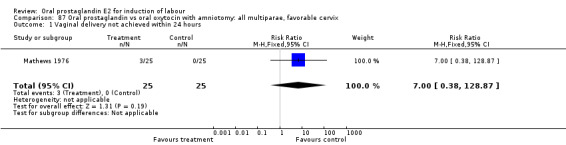

Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours was included as an outcome measure in three studies (Lange 1981; Mathews 1976; Westergaard 1983a). Individual comparisons tended to favor other treatments without reaching statistical significance. In the composite of oral PGE2 versus all oxytocin treatments, there was a trend favoring other treatments (RR 1.97, 95% CI 0.86 to 4.48).

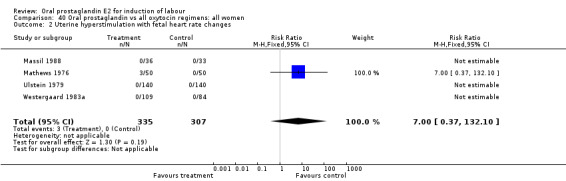

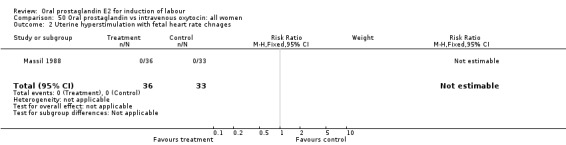

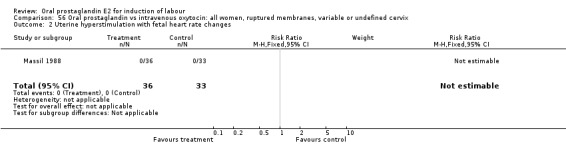

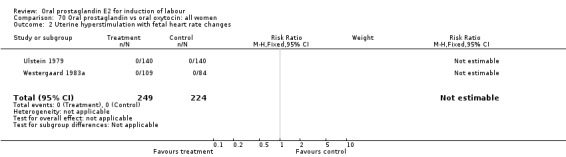

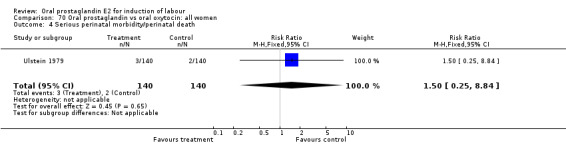

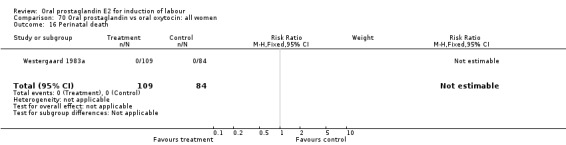

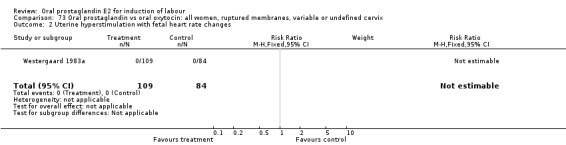

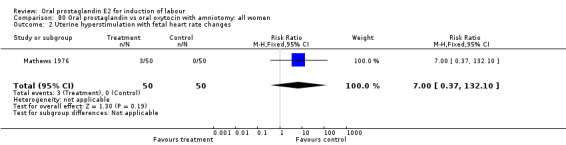

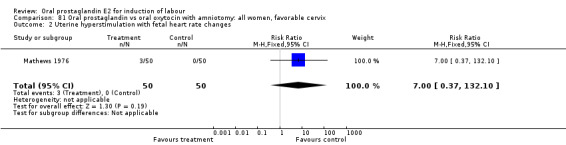

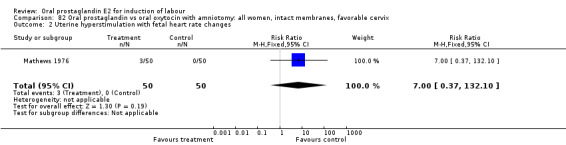

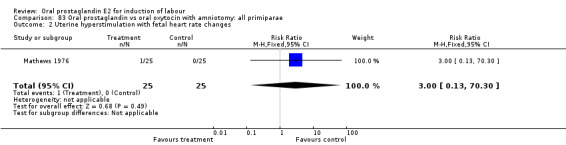

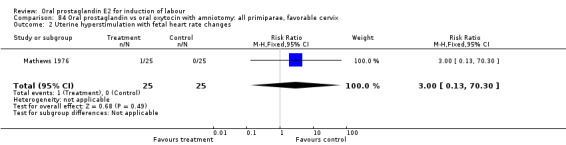

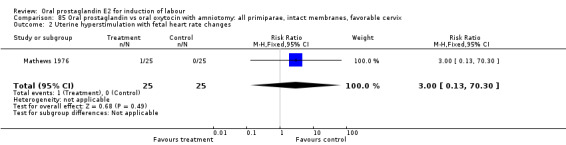

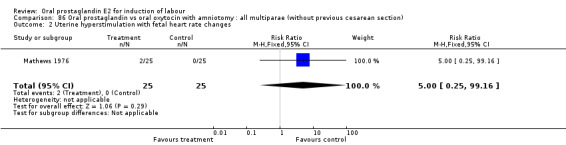

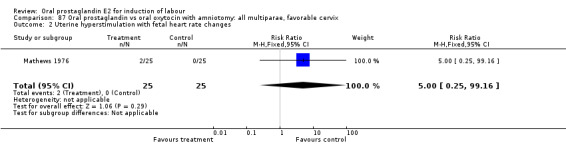

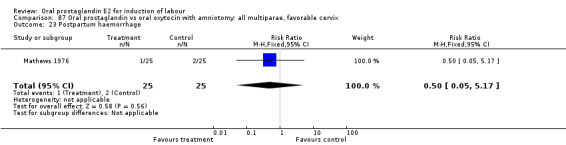

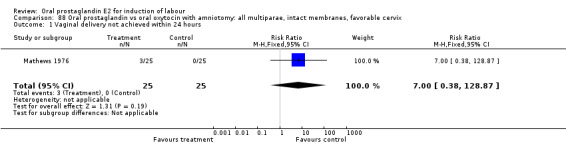

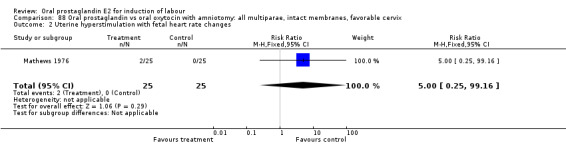

Uterine hyperstimulation with fetal heart rate (FHR) changes was an outcome reported in four studies (Massil 1988; Mathews 1976; Ulstein 1979; Westergaard 1983a). Of these, only one (Mathews 1976) reported cases in either group, all three of the cases in women receiving PGE2. The result was that in the composite of oral PGE2 versus all oxytocin treatments, there was a trend in favor of oxytocin treatments, though with a very wide confidence interval (RR 7.00 95% CI 0.37 to 132.10). Perinatal death was not consistently included as an outcome. Somell 1987 reported two deaths that were attributed to congenital malformations. The only study reporting what might be classified as severe perinatal morbidity, was the outcome called 'intrauterine asphyxia', by Ulstein 1979. There was no difference between the PGE2 and the oral oxytocin groups in that study.

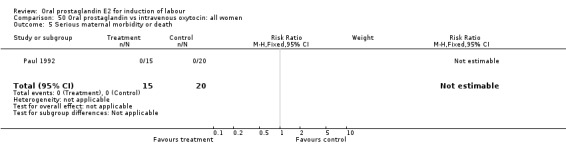

Serious maternal morbidity or death was reported only by Paul 1992, which stated that there was none in either treatment group (oral PGE2 versus intravenous (IV) oxytocin).

Secondary outcomes

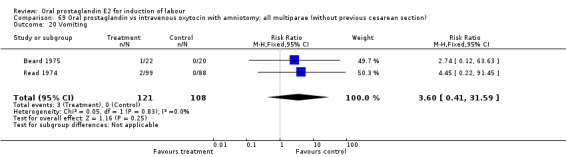

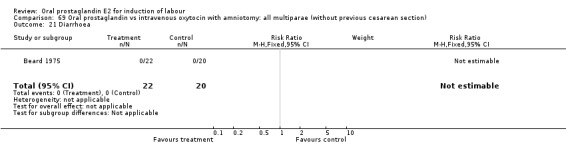

Gastrointestinal side‐effects

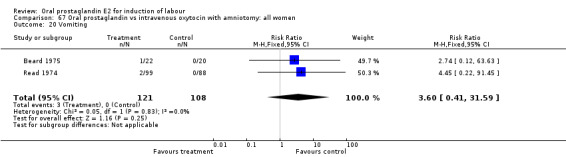

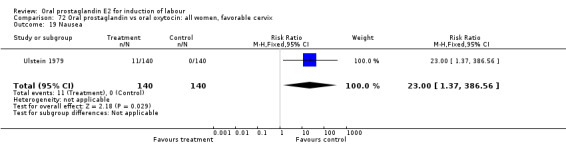

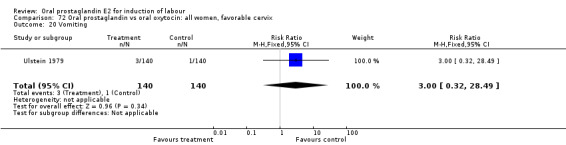

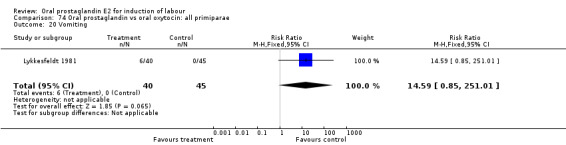

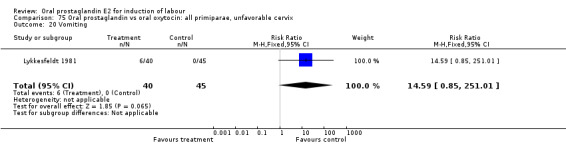

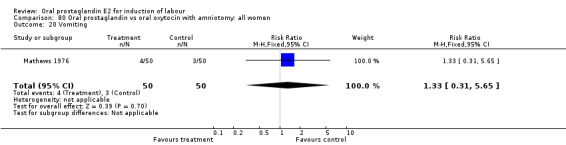

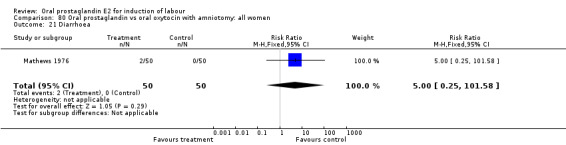

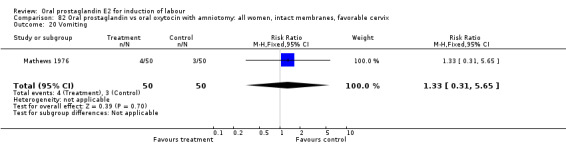

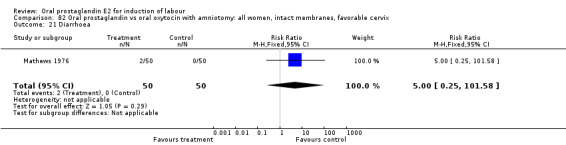

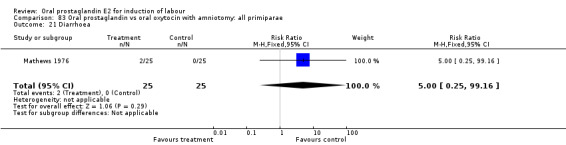

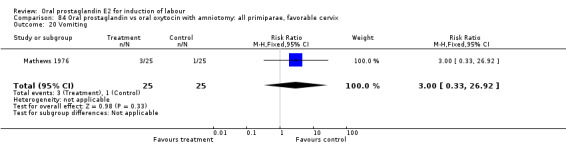

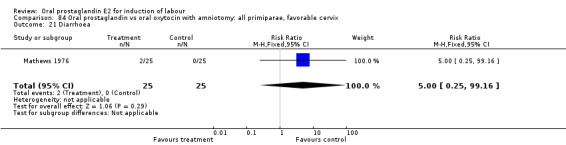

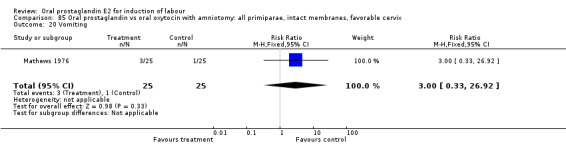

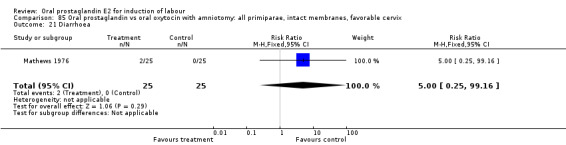

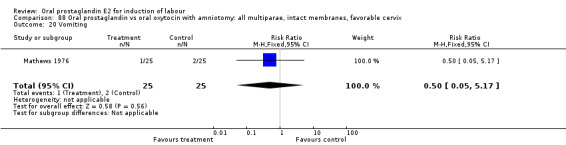

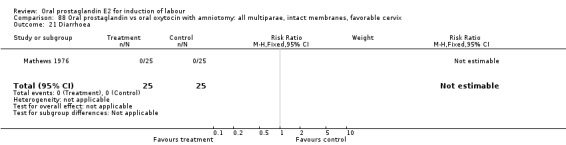

Gastrointestinal side‐effects were frequently reported in the studies reviewed. Often nausea and vomiting was reported as a composite outcome. In these cases, the data were entered under the variable vomiting. Gastrointestinal side‐effects were more frequent for women treated with oral PGE2 than with other treatments in all comparisons, most of which reached statistical significance.

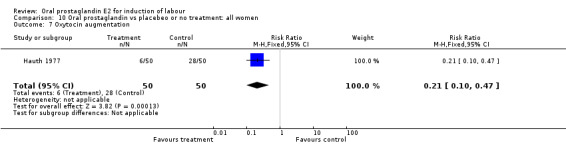

Oxytocin augmentation

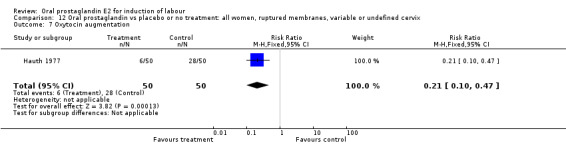

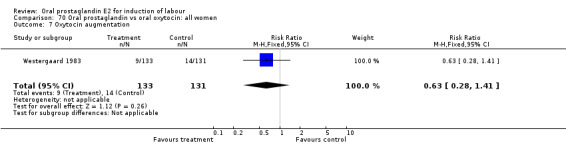

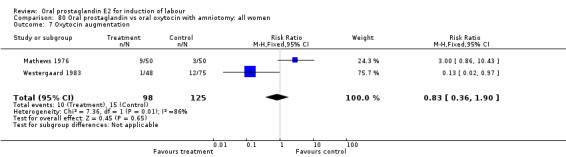

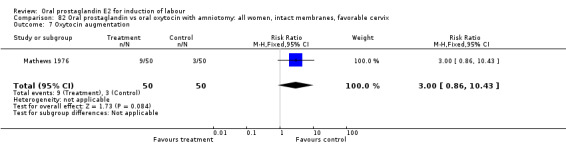

This outcome was reported in three studies (Hauth 1977; Mathews 1976; Westergaard 1983). It is not surprising that in Hauth's study of oral PGE2 versus no treatment for the first 12 hours, then oxytocin augmentation in both groups if needed, oxytocin was needed more often in the no treatment group. In the other two studies there was not a significant difference in use of oxytocin augmentation.

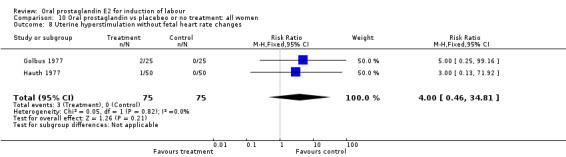

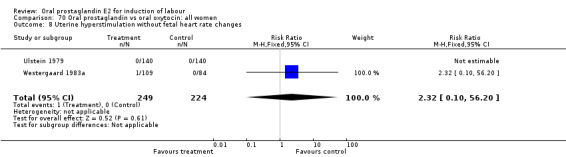

Uterine hyperstimulation without FHR changes

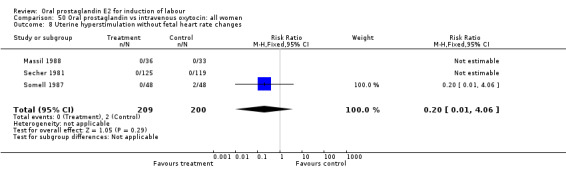

This outcome was reported in eight studies. No significant differences between comparison groups were observed.

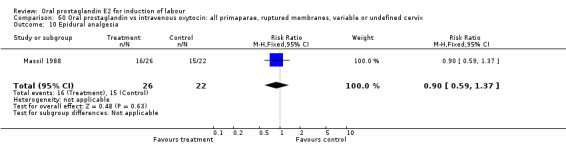

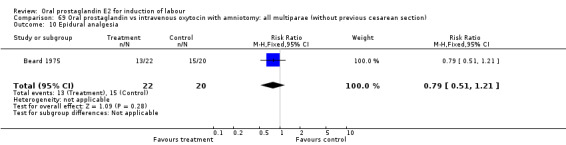

Epidural analgesia

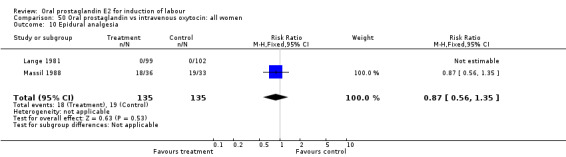

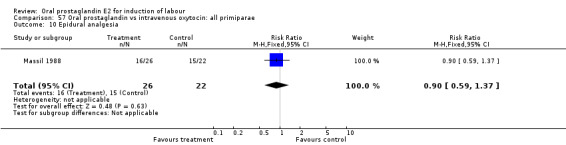

This outcome was reported in only three studies (Beard 1975; Lange 1981; Massil 1988). No significant differences between groups were observed.

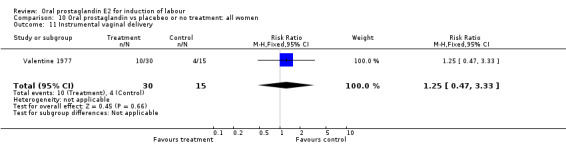

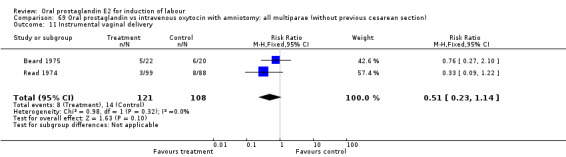

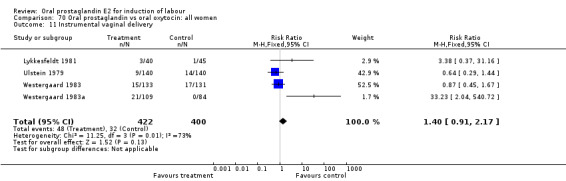

Instrumental vaginal delivery

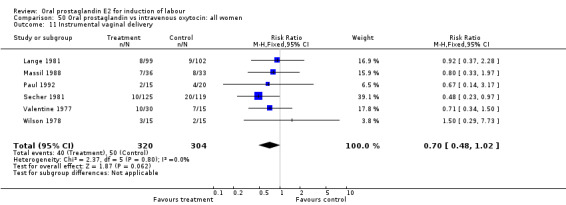

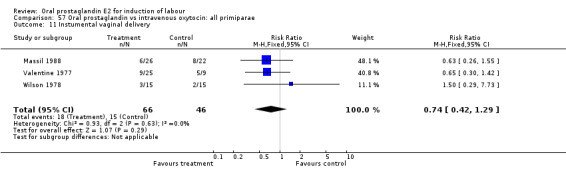

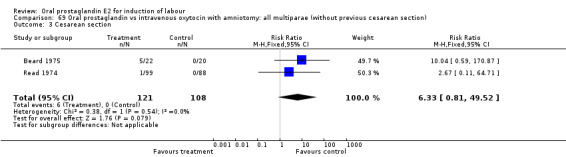

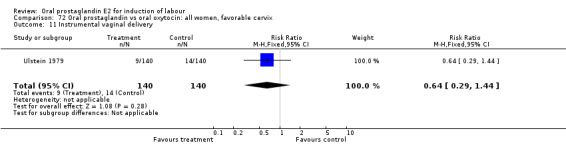

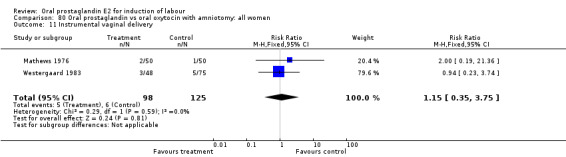

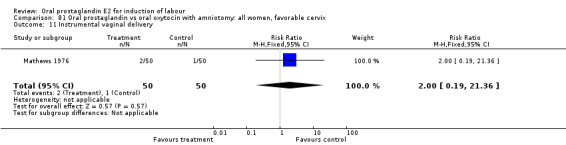

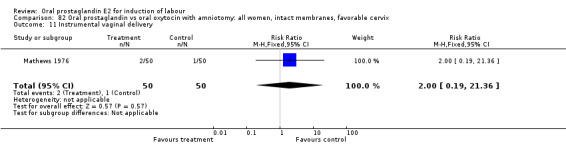

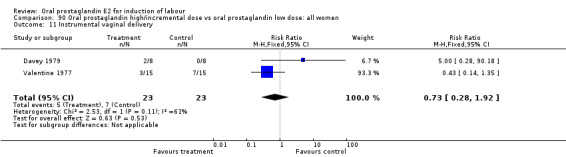

This outcome was reported in the majority (17) of studies. In none of the comparisons was there a statistically significant difference.

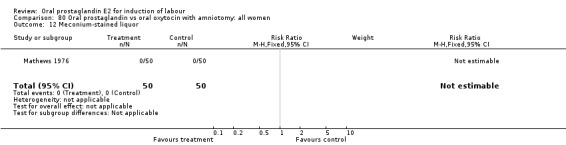

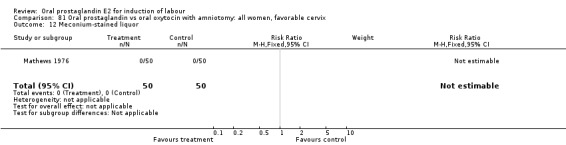

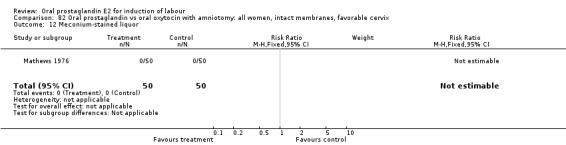

Meconium stained liquor

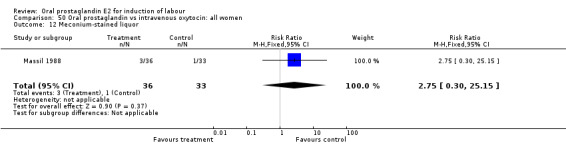

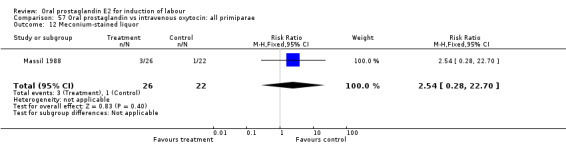

This outcome was reported in only two studies (Massil 1988; Mathews 1976). No significant differences were found in either study.

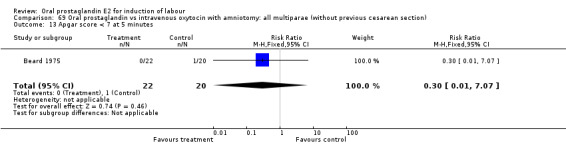

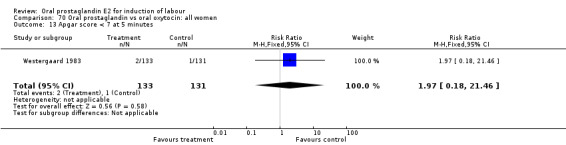

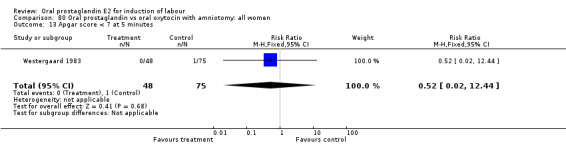

Apgar score less than seven at five minutes

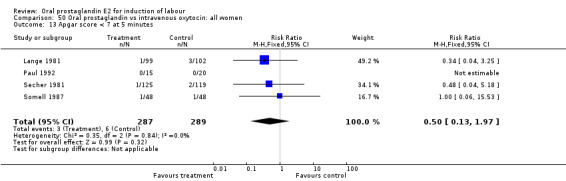

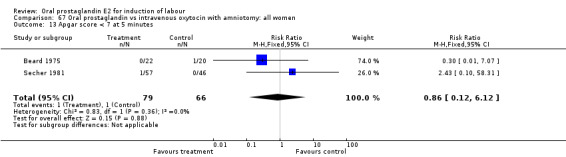

This outcome was reported in seven studies (Beard 1975; Herabutya 1988Lange 1981; Paul 1992; Secher 1981; Somell 1987; Westergaard 1983). No significant differences were found between comparison groups.

Neonatal intensive care unit admission

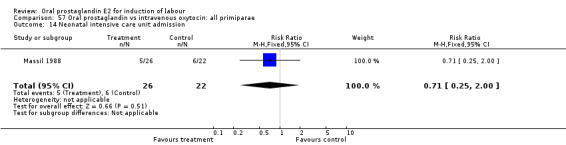

This outcome was reported in only one study (Massil 1988) and there was not a significant difference between groups (oral PGE2 versus IV oxytocin).

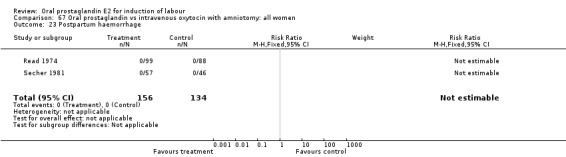

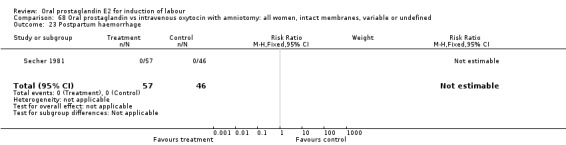

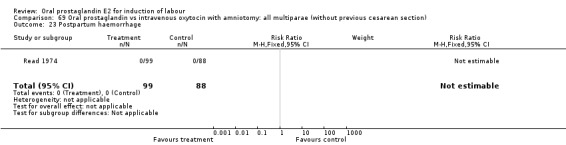

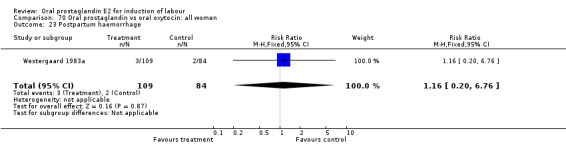

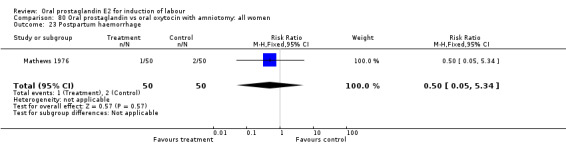

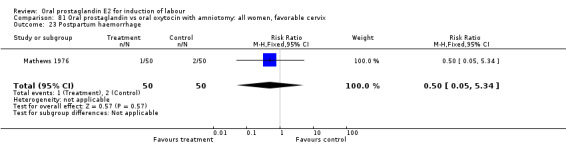

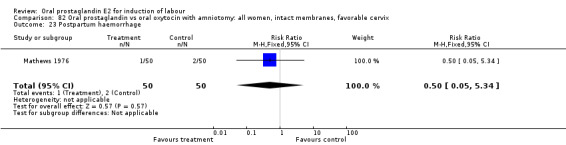

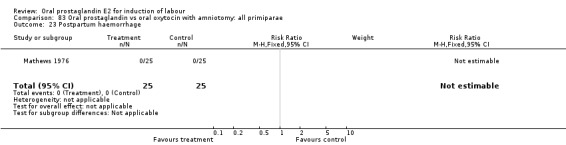

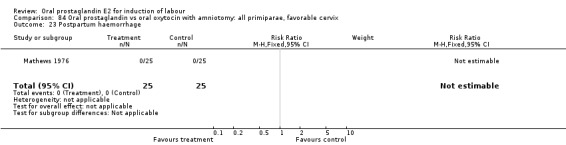

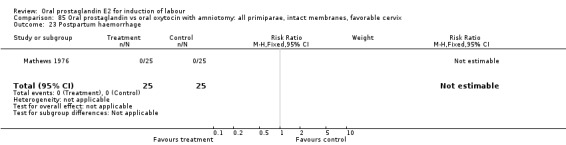

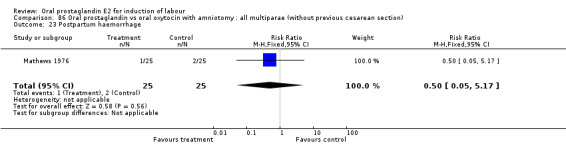

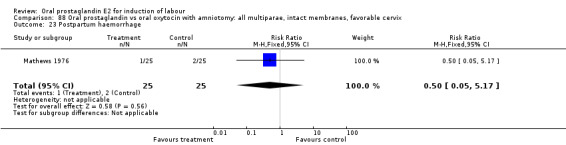

Postpartum hemorrhage

This outcome was reported in six studies (Beard 1975; Massil 1988; Mathews 1976; Read 1974; Secher 1981; Westergaard 1983a). No significant differences between comparison groups were found.

Women not satisfied

This outcome was reported in one (Massil 1988) small study. Women preferred an oral treatment versus IV (oxytocin) medication.

Caregiver not satisfied

In the same study (Massil 1988) caregivers did not have a clear preference for oral PGE2 or IV oxytocin.

Other outcomes

Maternal or neonatal infection requiring antibiotics

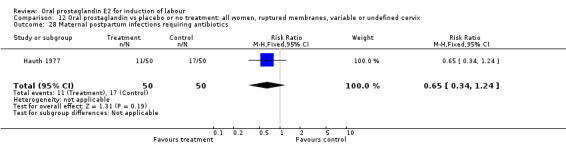

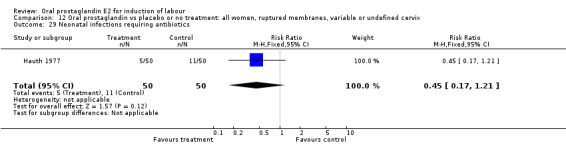

In the Hauth 1977 study of oral PGE2 versus no treatment for 12 hours, followed by oxytocin as needed in both treatment groups of women with ruptured membranes at term, there were trends favoring the oral PGE2 group for use of antibiotics in both mothers and infants. This may be attributable to more rapid delivery. Mean time to delivery was 11.6 versus 15.6 hours, (no standard deviation given).

Discussion

This review is limited by the quality of the available studies. Allocation concealment was not clearly described in most studies and, when it was, significant potential for bias still existed due to lack of blinding. A further limitation is that the number of participants in aggregate, is not large.

For the five primary outcome measures, only cesarean section was consistently reported. The results of this meta‐analysis trend in favor of oxytocin. This cannot be firmly concluded, however.

Of the secondary outcomes, results in favor of all oxytocin treatments regarding gastrointestinal side‐effects are consistent enough to be conclusive. Other secondary outcomes do not clearly favor oral prostaglandin or other treatments.

There were insufficient data to demonstrate superiority of high or incremental dosing regimens of oral PGE2 over low or constant dosing.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Oral PGE2 is not more effective than oxytocin for achieving delivery within 24 hours of labor induction. Gastrointestinal side‐effects are more frequent with PGE2. There is no clear evidence favoring either oral PGE2 or oxytocin regimens regarding safety of women or their infants.

Implications for research.

Little further research is likely to be forthcoming comparing oral PGE2 to other regimens. Though some women may prefer an oral route of administration of agents for induction of labor, oral misoprostol (synthetic prostaglandin) is likely to supercede the oral preparations of PGE2 that are in current use.

[Note: The six citations in the awaiting classification section of the review may alter the conclusions of the review once assessed.]

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 8 June 2012 | Amended | Search updated. Six reports added to Studies awaiting classification (Bremme 1980a; Bremme 1980b; Bremme 1982; Bremme 1984a; Marzouk 1975; Murray 1975). |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2000 Review first published: Issue 2, 2001

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 12 May 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 25 January 2007 | New search has been performed | Search repeated. Four reports have been assessed and added to the list of excluded studies. |

Acknowledgements

None.

Data and analyses

Comparison 10. Oral prostaglandin vs placebeo or no treatment: all women.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Cesarean section | 3 | 195 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.54 [0.29, 0.98] |

| 7 Oxytocin augmentation | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.21 [0.10, 0.47] |

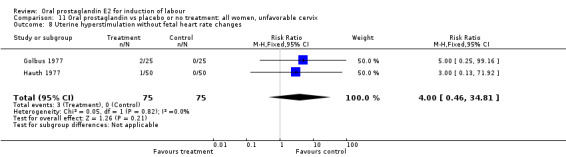

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without fetal heart rate changes | 2 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.0 [0.46, 34.81] |

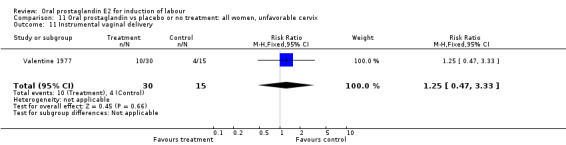

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 45 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.47, 3.33] |

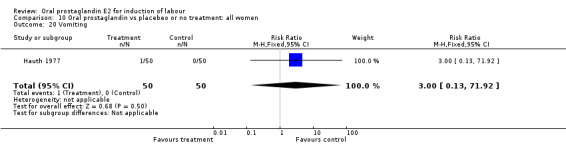

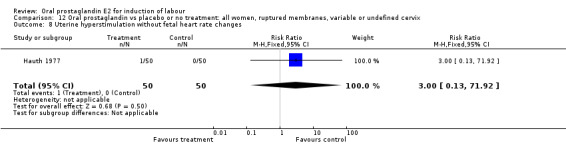

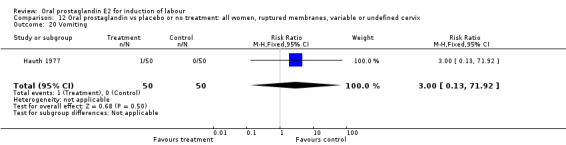

| 20 Vomiting | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 71.92] |

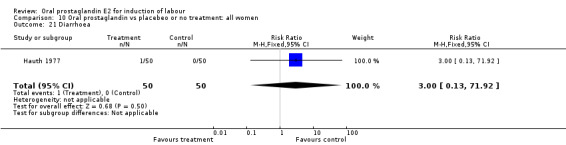

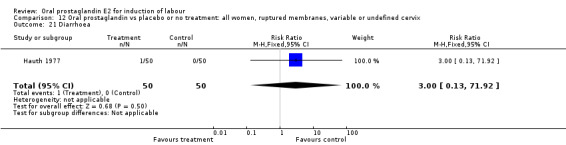

| 21 Diarrhoea | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 71.92] |

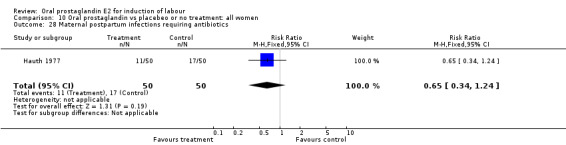

| 28 Maternal postpartum infections requiring antibiotics | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.34, 1.24] |

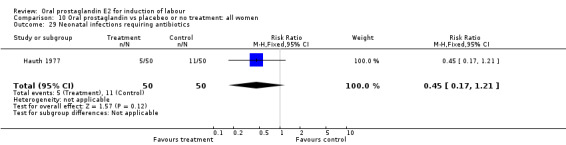

| 29 Neonatal infections requiring antibiotics | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.45 [0.17, 1.21] |

10.3. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Oral prostaglandin vs placebeo or no treatment: all women, Outcome 3 Cesarean section.

10.7. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Oral prostaglandin vs placebeo or no treatment: all women, Outcome 7 Oxytocin augmentation.

10.8. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Oral prostaglandin vs placebeo or no treatment: all women, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without fetal heart rate changes.

10.11. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Oral prostaglandin vs placebeo or no treatment: all women, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

10.20. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Oral prostaglandin vs placebeo or no treatment: all women, Outcome 20 Vomiting.

10.21. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Oral prostaglandin vs placebeo or no treatment: all women, Outcome 21 Diarrhoea.

10.28. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Oral prostaglandin vs placebeo or no treatment: all women, Outcome 28 Maternal postpartum infections requiring antibiotics.

10.29. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Oral prostaglandin vs placebeo or no treatment: all women, Outcome 29 Neonatal infections requiring antibiotics.

Comparison 11. Oral prostaglandin vs placebo or no treatment: all women, unfavorable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Cesarean section | 3 | 195 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.54 [0.29, 0.98] |

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without fetal heart rate changes | 2 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 4.0 [0.46, 34.81] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 45 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.47, 3.33] |

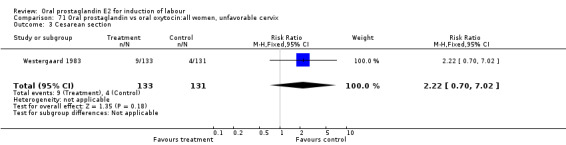

11.3. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Oral prostaglandin vs placebo or no treatment: all women, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 3 Cesarean section.

11.8. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Oral prostaglandin vs placebo or no treatment: all women, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without fetal heart rate changes.

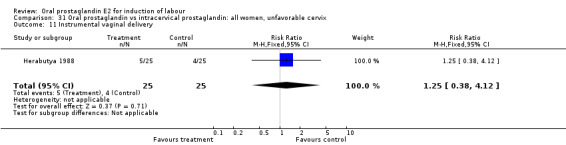

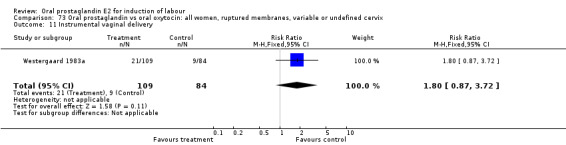

11.11. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Oral prostaglandin vs placebo or no treatment: all women, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

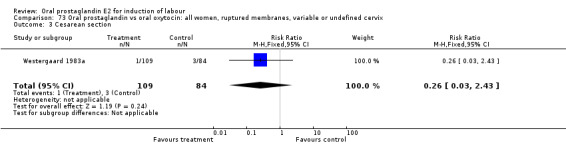

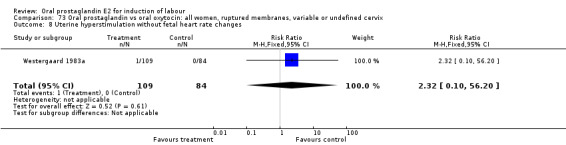

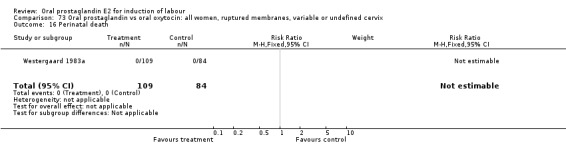

Comparison 12. Oral prostaglandin vs placebo or no treatment: all women, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

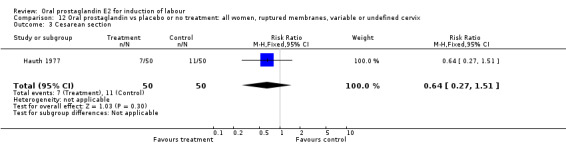

| 3 Cesarean section | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.64 [0.27, 1.51] |

| 7 Oxytocin augmentation | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.21 [0.10, 0.47] |

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without fetal heart rate changes | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 71.92] |

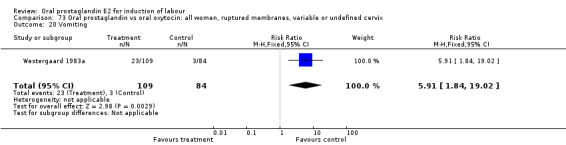

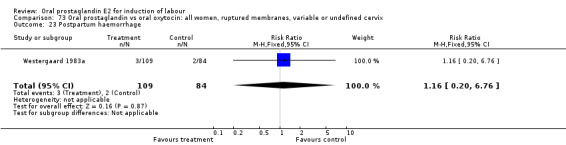

| 20 Vomiting | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 71.92] |

| 21 Diarrhoea | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.0 [0.13, 71.92] |

| 28 Maternal postpartum infections requiring antibiotics | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.34, 1.24] |

| 29 Neonatal infections requiring antibiotics | 1 | 100 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.45 [0.17, 1.21] |

12.3. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Oral prostaglandin vs placebo or no treatment: all women, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 3 Cesarean section.

12.7. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Oral prostaglandin vs placebo or no treatment: all women, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 7 Oxytocin augmentation.

12.8. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Oral prostaglandin vs placebo or no treatment: all women, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without fetal heart rate changes.

12.20. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Oral prostaglandin vs placebo or no treatment: all women, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 20 Vomiting.

12.21. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Oral prostaglandin vs placebo or no treatment: all women, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 21 Diarrhoea.

12.28. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Oral prostaglandin vs placebo or no treatment: all women, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 28 Maternal postpartum infections requiring antibiotics.

12.29. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Oral prostaglandin vs placebo or no treatment: all women, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 29 Neonatal infections requiring antibiotics.

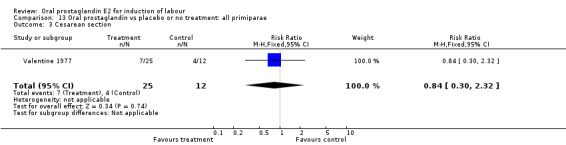

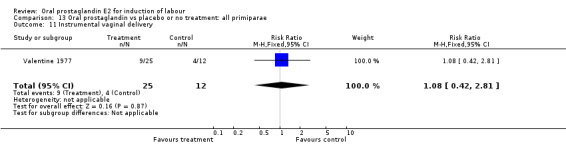

Comparison 13. Oral prostaglandin vs placebo or no treatment: all primiparae.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Cesarean section | 1 | 37 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.30, 2.32] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 37 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.42, 2.81] |

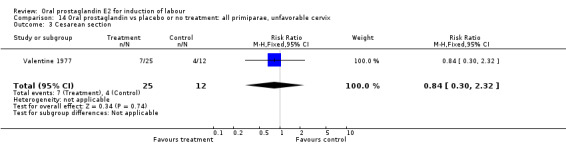

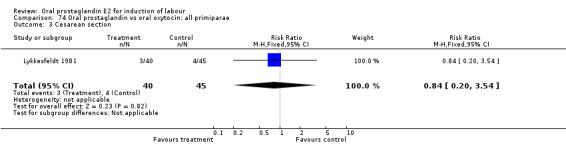

13.3. Analysis.

Comparison 13 Oral prostaglandin vs placebo or no treatment: all primiparae, Outcome 3 Cesarean section.

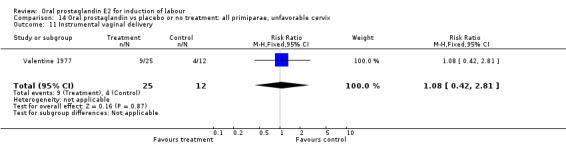

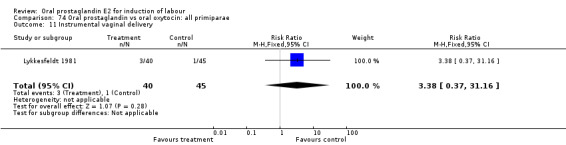

13.11. Analysis.

Comparison 13 Oral prostaglandin vs placebo or no treatment: all primiparae, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

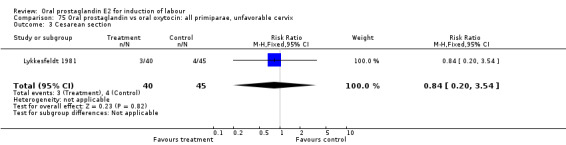

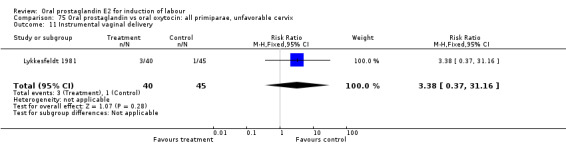

Comparison 14. Oral prostaglandin vs placebo or no treatment: all primiparae, unfavorable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Cesarean section | 1 | 37 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.84 [0.30, 2.32] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 37 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.42, 2.81] |

14.3. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Oral prostaglandin vs placebo or no treatment: all primiparae, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 3 Cesarean section.

14.11. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Oral prostaglandin vs placebo or no treatment: all primiparae, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

Comparison 15. Oral prostaglandin vs placebo or no treatment: all multiparae (without previous cesarean section).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

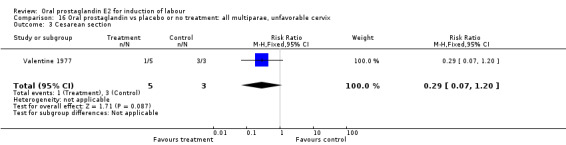

| 3 Cesarean section | 1 | 8 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.29 [0.07, 1.20] |

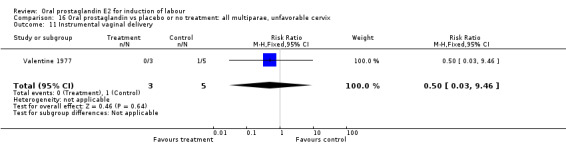

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 8 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.5 [0.03, 9.46] |

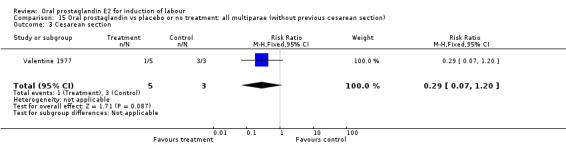

15.3. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Oral prostaglandin vs placebo or no treatment: all multiparae (without previous cesarean section), Outcome 3 Cesarean section.

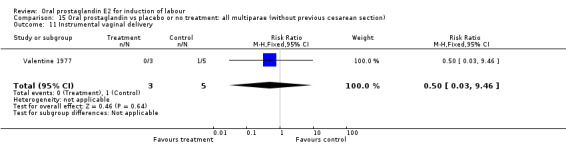

15.11. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Oral prostaglandin vs placebo or no treatment: all multiparae (without previous cesarean section), Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

Comparison 16. Oral prostaglandin vs placebo or no treatment: all multiparae, unfavorable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Cesarean section | 1 | 8 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.29 [0.07, 1.20] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 8 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.5 [0.03, 9.46] |

16.3. Analysis.

Comparison 16 Oral prostaglandin vs placebo or no treatment: all multiparae, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 3 Cesarean section.

16.11. Analysis.

Comparison 16 Oral prostaglandin vs placebo or no treatment: all multiparae, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

Comparison 20. Oral prostaglandin vs vaginal prostaglandin: all women.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

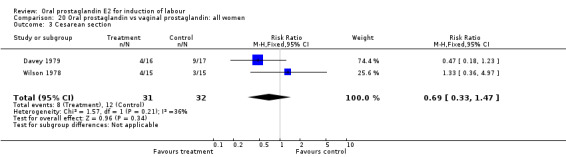

| 3 Cesarean section | 2 | 63 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.33, 1.47] |

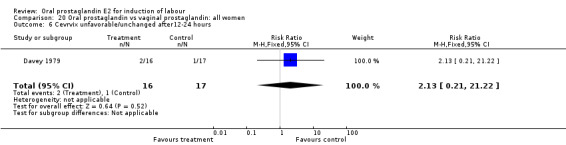

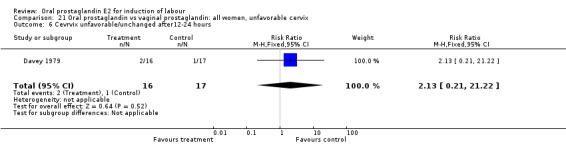

| 6 Cevrvix unfavorable/unchanged after12‐24 hours | 1 | 33 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.13 [0.21, 21.22] |

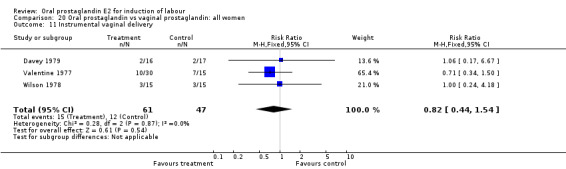

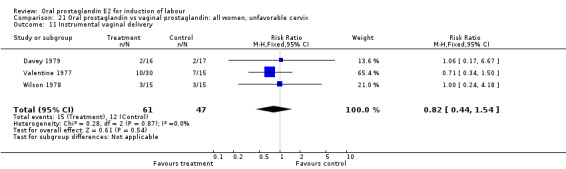

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 3 | 108 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.44, 1.54] |

20.3. Analysis.

Comparison 20 Oral prostaglandin vs vaginal prostaglandin: all women, Outcome 3 Cesarean section.

20.6. Analysis.

Comparison 20 Oral prostaglandin vs vaginal prostaglandin: all women, Outcome 6 Cevrvix unfavorable/unchanged after12‐24 hours.

20.11. Analysis.

Comparison 20 Oral prostaglandin vs vaginal prostaglandin: all women, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

Comparison 21. Oral prostaglandin vs vaginal prostaglandin: all women, unfavorable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

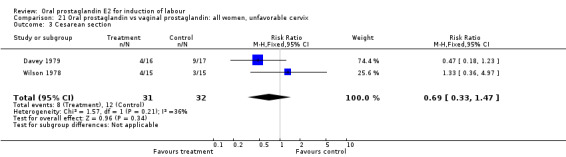

| 3 Cesarean section | 2 | 63 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.33, 1.47] |

| 6 Cevrvix unfavorable/unchanged after12‐24 hours | 1 | 33 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.13 [0.21, 21.22] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 3 | 108 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.44, 1.54] |

21.3. Analysis.

Comparison 21 Oral prostaglandin vs vaginal prostaglandin: all women, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 3 Cesarean section.

21.6. Analysis.

Comparison 21 Oral prostaglandin vs vaginal prostaglandin: all women, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 6 Cevrvix unfavorable/unchanged after12‐24 hours.

21.11. Analysis.

Comparison 21 Oral prostaglandin vs vaginal prostaglandin: all women, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

Comparison 22. Oral prostaglandin vs vaginal prostaglandin: all primiparae.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

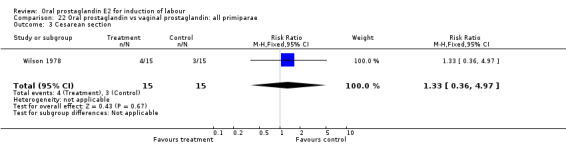

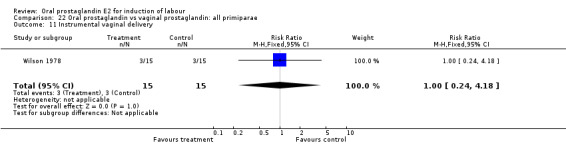

| 3 Cesarean section | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.33 [0.36, 4.97] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.24, 4.18] |

22.3. Analysis.

Comparison 22 Oral prostaglandin vs vaginal prostaglandin: all primiparae, Outcome 3 Cesarean section.

22.11. Analysis.

Comparison 22 Oral prostaglandin vs vaginal prostaglandin: all primiparae, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

Comparison 23. Oral prostaglandin vs vaginal prostaglandin: all primiparae, unfavorable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

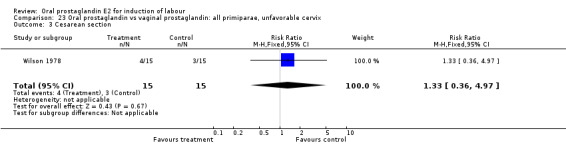

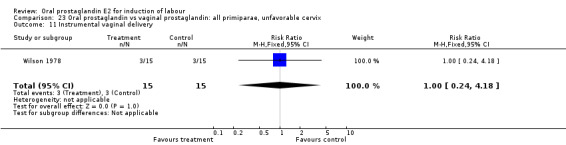

| 3 Cesarean section | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.33 [0.36, 4.97] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.24, 4.18] |

23.3. Analysis.

Comparison 23 Oral prostaglandin vs vaginal prostaglandin: all primiparae, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 3 Cesarean section.

23.11. Analysis.

Comparison 23 Oral prostaglandin vs vaginal prostaglandin: all primiparae, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

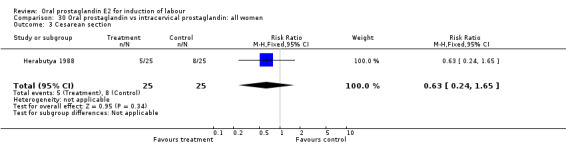

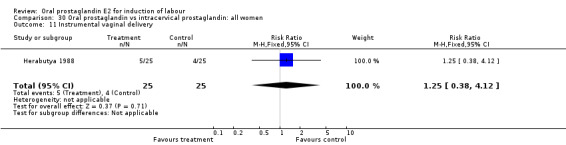

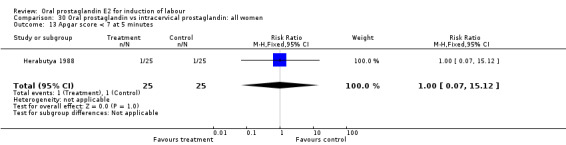

Comparison 30. Oral prostaglandin vs intracervical prostaglandin: all women.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Cesarean section | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.24, 1.65] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.38, 4.12] |

| 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.07, 15.12] |

30.3. Analysis.

Comparison 30 Oral prostaglandin vs intracervical prostaglandin: all women, Outcome 3 Cesarean section.

30.11. Analysis.

Comparison 30 Oral prostaglandin vs intracervical prostaglandin: all women, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

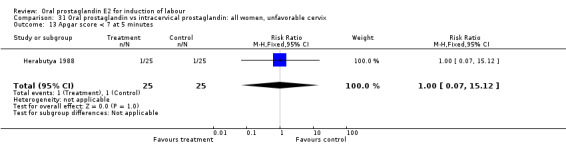

30.13. Analysis.

Comparison 30 Oral prostaglandin vs intracervical prostaglandin: all women, Outcome 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

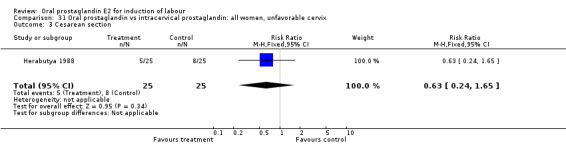

Comparison 31. Oral prostaglandin vs intracervical prostaglandin: all women, unfavorable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Cesarean section | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.24, 1.65] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.38, 4.12] |

| 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.07, 15.12] |

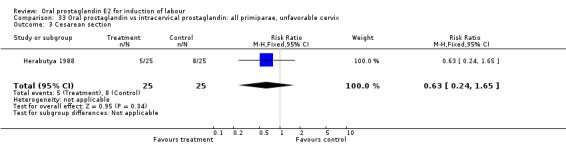

31.3. Analysis.

Comparison 31 Oral prostaglandin vs intracervical prostaglandin: all women, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 3 Cesarean section.

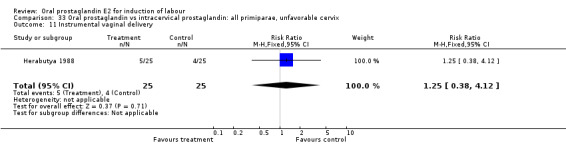

31.11. Analysis.

Comparison 31 Oral prostaglandin vs intracervical prostaglandin: all women, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

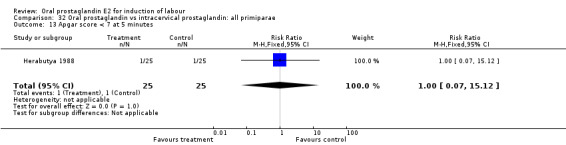

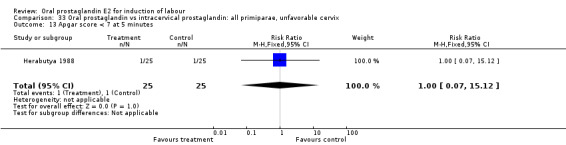

31.13. Analysis.

Comparison 31 Oral prostaglandin vs intracervical prostaglandin: all women, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

Comparison 32. Oral prostaglandin vs intracervical prostaglandin: all primiparae.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Cesarean section | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.24, 1.65] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.38, 4.12] |

| 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.07, 15.12] |

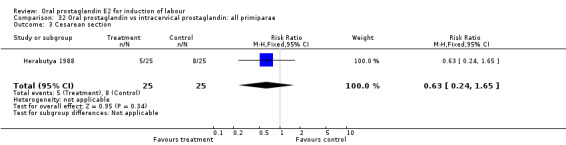

32.3. Analysis.

Comparison 32 Oral prostaglandin vs intracervical prostaglandin: all primiparae, Outcome 3 Cesarean section.

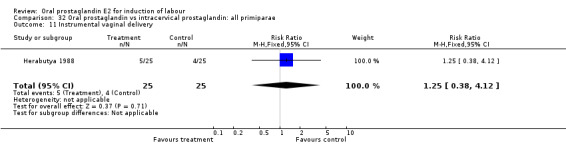

32.11. Analysis.

Comparison 32 Oral prostaglandin vs intracervical prostaglandin: all primiparae, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

32.13. Analysis.

Comparison 32 Oral prostaglandin vs intracervical prostaglandin: all primiparae, Outcome 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

Comparison 33. Oral prostaglandin vs intracervical prostaglandin: all primiparae, unfavorable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Cesarean section | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.24, 1.65] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.25 [0.38, 4.12] |

| 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.07, 15.12] |

33.3. Analysis.

Comparison 33 Oral prostaglandin vs intracervical prostaglandin: all primiparae, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 3 Cesarean section.

33.11. Analysis.

Comparison 33 Oral prostaglandin vs intracervical prostaglandin: all primiparae, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

33.13. Analysis.

Comparison 33 Oral prostaglandin vs intracervical prostaglandin: all primiparae, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

Comparison 40. Oral prostaglandin vs all oxytocin regimens: all women.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours | 3 | 494 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.97 [0.86, 4.48] |

| 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with fetal heart rate changes | 4 | 642 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.0 [0.37, 132.10] |

| 3 Cesarean section | 14 | 2204 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.15 [0.83, 1.59] |

40.1. Analysis.

Comparison 40 Oral prostaglandin vs all oxytocin regimens: all women, Outcome 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours.

40.2. Analysis.

Comparison 40 Oral prostaglandin vs all oxytocin regimens: all women, Outcome 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with fetal heart rate changes.

40.3. Analysis.

Comparison 40 Oral prostaglandin vs all oxytocin regimens: all women, Outcome 3 Cesarean section.

Comparison 50. Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours | 1 | 201 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.09 [0.13, 74.96] |

| 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with fetal heart rate chnages | 1 | 69 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Cesarean section | 8 | 824 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.68, 1.68] |

| 5 Serious maternal morbidity or death | 1 | 35 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without fetal heart rate changes | 3 | 409 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.2 [0.01, 4.06] |

| 10 Epidural analgesia | 2 | 270 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.56, 1.35] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 6 | 624 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.48, 1.02] |

| 12 Meconium‐stained liquor | 1 | 69 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.75 [0.30, 25.15] |

| 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 4 | 576 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.50 [0.13, 1.97] |

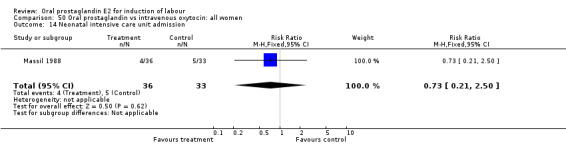

| 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 1 | 69 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.21, 2.50] |

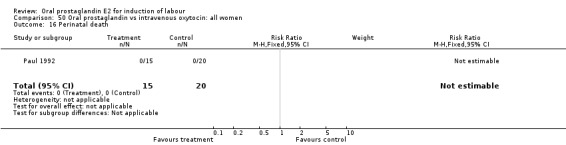

| 16 Perinatal death | 1 | 35 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 20 Vomiting | 3 | 305 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.56 [2.15, 14.38] |

| 21 Diarrhoea | 2 | 236 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 8.13 [1.03, 63.93] |

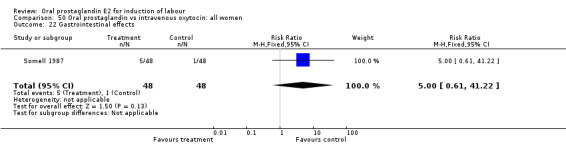

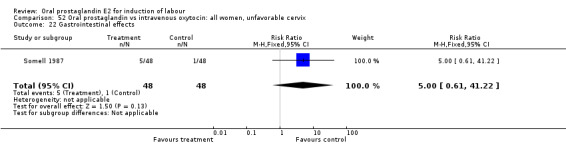

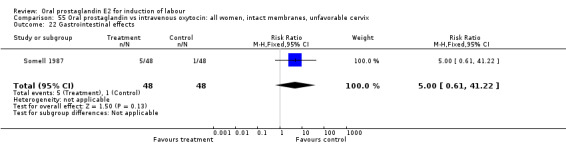

| 22 Gastrointestinal effects | 1 | 96 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.0 [0.61, 41.22] |

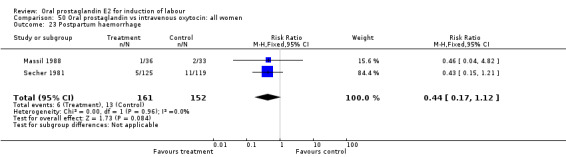

| 23 Postpartum haemorrhage | 2 | 313 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.44 [0.17, 1.12] |

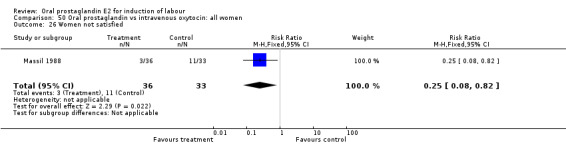

| 26 Women not satisfied | 1 | 69 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.25 [0.08, 0.82] |

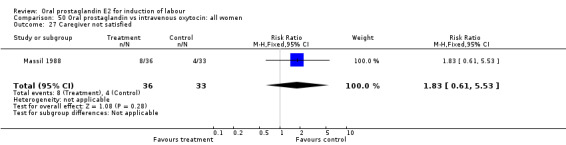

| 27 Caregiver not satisfied | 1 | 69 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.83 [0.61, 5.53] |

50.1. Analysis.

Comparison 50 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, Outcome 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours.

50.2. Analysis.

Comparison 50 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, Outcome 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with fetal heart rate chnages.

50.3. Analysis.

Comparison 50 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, Outcome 3 Cesarean section.

50.5. Analysis.

Comparison 50 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, Outcome 5 Serious maternal morbidity or death.

50.8. Analysis.

Comparison 50 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without fetal heart rate changes.

50.10. Analysis.

Comparison 50 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, Outcome 10 Epidural analgesia.

50.11. Analysis.

Comparison 50 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

50.12. Analysis.

Comparison 50 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, Outcome 12 Meconium‐stained liquor.

50.13. Analysis.

Comparison 50 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, Outcome 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

50.14. Analysis.

Comparison 50 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

50.16. Analysis.

Comparison 50 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, Outcome 16 Perinatal death.

50.20. Analysis.

Comparison 50 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, Outcome 20 Vomiting.

50.21. Analysis.

Comparison 50 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, Outcome 21 Diarrhoea.

50.22. Analysis.

Comparison 50 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, Outcome 22 Gastrointestinal effects.

50.23. Analysis.

Comparison 50 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, Outcome 23 Postpartum haemorrhage.

50.26. Analysis.

Comparison 50 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, Outcome 26 Women not satisfied.

50.27. Analysis.

Comparison 50 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, Outcome 27 Caregiver not satisfied.

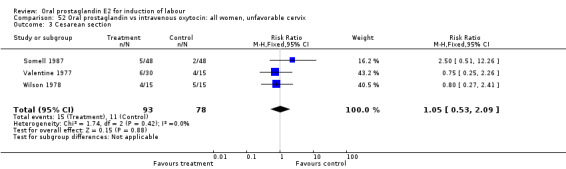

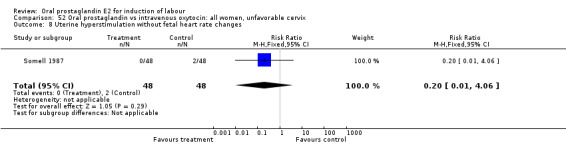

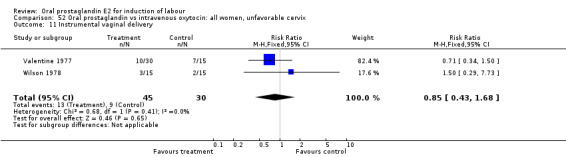

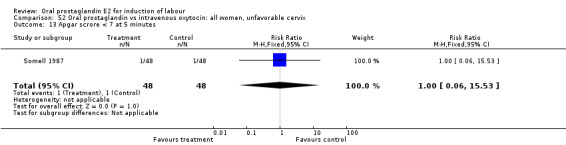

Comparison 52. Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, unfavorable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Cesarean section | 3 | 171 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.53, 2.09] |

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without fetal heart rate changes | 1 | 96 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.2 [0.01, 4.06] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 2 | 75 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.43, 1.68] |

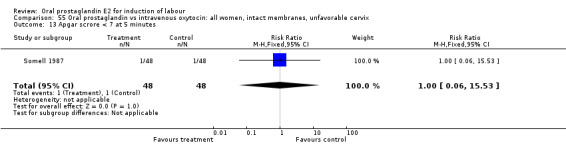

| 13 Apgar scrore < 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 96 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.06, 15.53] |

| 22 Gastrointestinal effects | 1 | 96 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.0 [0.61, 41.22] |

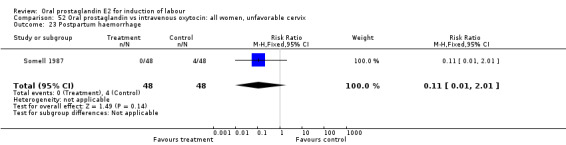

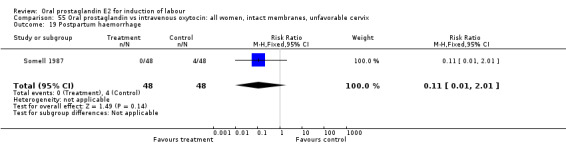

| 23 Postpartum haemorrhage | 1 | 96 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.11 [0.01, 2.01] |

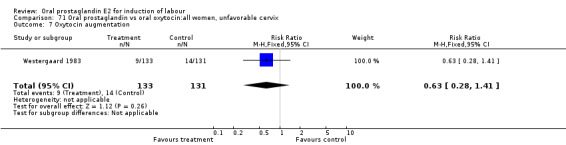

52.3. Analysis.

Comparison 52 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 3 Cesarean section.

52.8. Analysis.

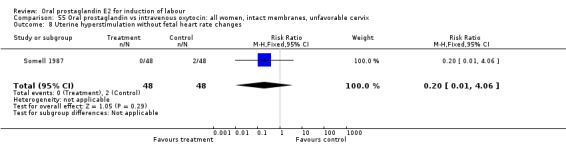

Comparison 52 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without fetal heart rate changes.

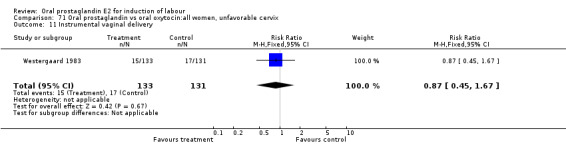

52.11. Analysis.

Comparison 52 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

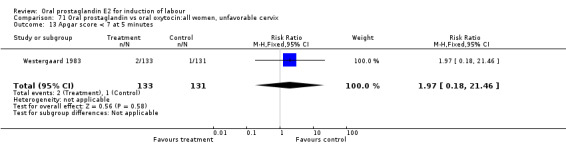

52.13. Analysis.

Comparison 52 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 13 Apgar scrore < 7 at 5 minutes.

52.22. Analysis.

Comparison 52 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 22 Gastrointestinal effects.

52.23. Analysis.

Comparison 52 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 23 Postpartum haemorrhage.

Comparison 54. Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, intact membranes, variable or undefined cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

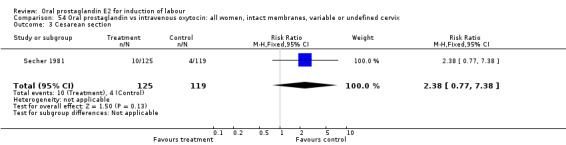

| 3 Cesarean section | 1 | 244 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.38 [0.77, 7.38] |

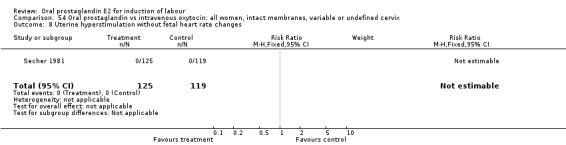

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without fetal heart rate changes | 1 | 244 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

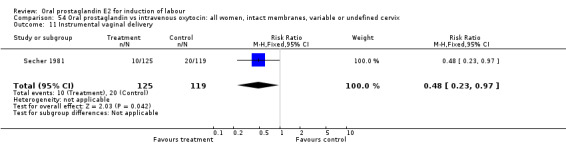

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 244 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.48 [0.23, 0.97] |

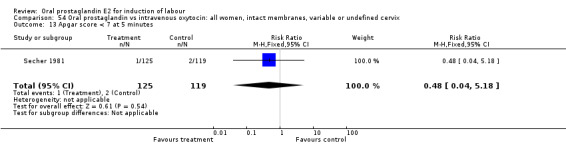

| 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 244 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.48 [0.04, 5.18] |

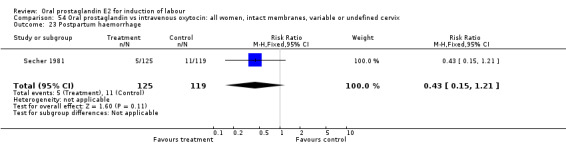

| 23 Postpartum haemorrhage | 1 | 244 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.43 [0.15, 1.21] |

54.3. Analysis.

Comparison 54 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, intact membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 3 Cesarean section.

54.8. Analysis.

Comparison 54 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, intact membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without fetal heart rate changes.

54.11. Analysis.

Comparison 54 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, intact membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

54.13. Analysis.

Comparison 54 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, intact membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

54.23. Analysis.

Comparison 54 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, intact membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 23 Postpartum haemorrhage.

Comparison 55. Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, intact membranes, unfavorable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

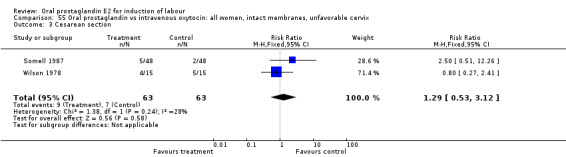

| 3 Cesarean section | 2 | 126 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.29 [0.53, 3.12] |

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without fetal heart rate changes | 1 | 96 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.2 [0.01, 4.06] |

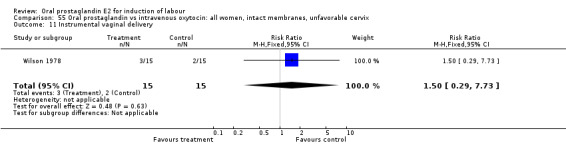

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 30 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.5 [0.29, 7.73] |

| 13 Apgar scrore < 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 96 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.0 [0.06, 15.53] |

| 19 Postpartum haemorrhage | 1 | 96 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.11 [0.01, 2.01] |

| 22 Gastrointestinal effects | 1 | 96 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.0 [0.61, 41.22] |

55.3. Analysis.

Comparison 55 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, intact membranes, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 3 Cesarean section.

55.8. Analysis.

Comparison 55 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, intact membranes, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without fetal heart rate changes.

55.11. Analysis.

Comparison 55 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, intact membranes, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

55.13. Analysis.

Comparison 55 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, intact membranes, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 13 Apgar scrore < 7 at 5 minutes.

55.19. Analysis.

Comparison 55 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, intact membranes, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 19 Postpartum haemorrhage.

55.22. Analysis.

Comparison 55 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, intact membranes, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 22 Gastrointestinal effects.

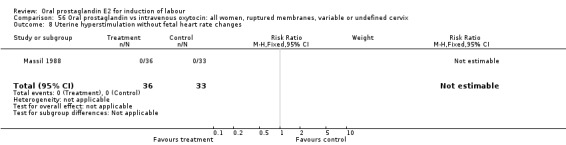

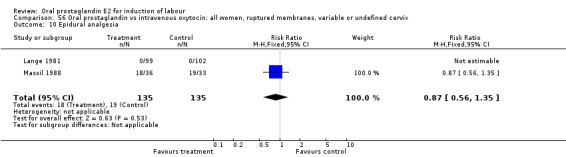

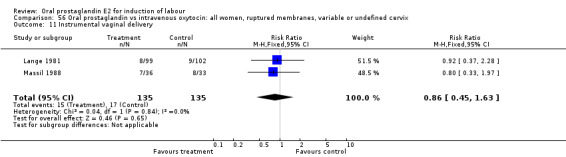

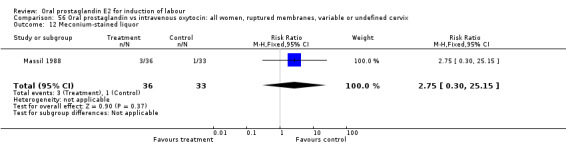

Comparison 56. Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours | 1 | 201 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.09 [0.13, 74.96] |

| 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with fetal heart rate changes | 1 | 69 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Cesarean section | 2 | 270 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.21 [0.32, 4.60] |

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without fetal heart rate changes | 1 | 69 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10 Epidural analgesia | 2 | 270 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.87 [0.56, 1.35] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 2 | 270 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.45, 1.63] |

| 12 Meconium‐stained liquor | 1 | 69 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.75 [0.30, 25.15] |

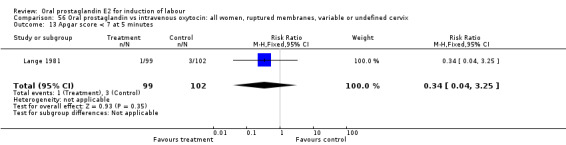

| 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 201 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.04, 3.25] |

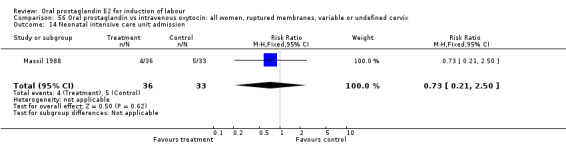

| 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 1 | 69 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.21, 2.50] |

| 20 Vomiting | 2 | 270 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.46 [2.00, 14.88] |

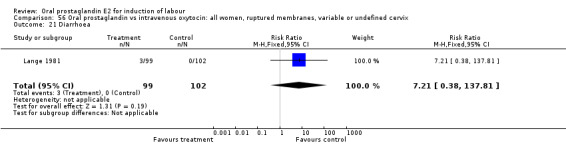

| 21 Diarrhoea | 1 | 201 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.21 [0.38, 137.81] |

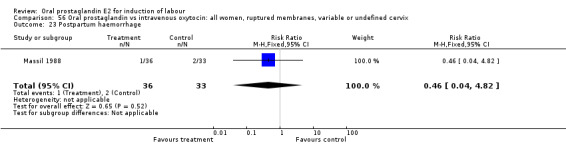

| 23 Postpartum haemorrhage | 1 | 69 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.46 [0.04, 4.82] |

56.1. Analysis.

Comparison 56 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 1 Vaginal delivery not achieved within 24 hours.

56.2. Analysis.

Comparison 56 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with fetal heart rate changes.

56.3. Analysis.

Comparison 56 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 3 Cesarean section.

56.8. Analysis.

Comparison 56 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without fetal heart rate changes.

56.10. Analysis.

Comparison 56 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 10 Epidural analgesia.

56.11. Analysis.

Comparison 56 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

56.12. Analysis.

Comparison 56 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 12 Meconium‐stained liquor.

56.13. Analysis.

Comparison 56 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

56.14. Analysis.

Comparison 56 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

56.20. Analysis.

Comparison 56 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 20 Vomiting.

56.21. Analysis.

Comparison 56 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 21 Diarrhoea.

56.23. Analysis.

Comparison 56 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all women, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 23 Postpartum haemorrhage.

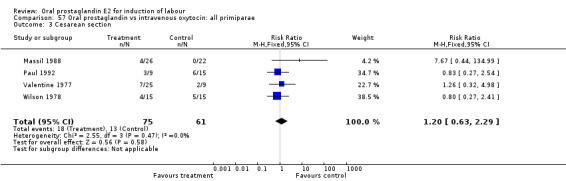

Comparison 57. Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all primiparae.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with fetal heart rate changes | 1 | 48 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Cesarean section | 4 | 136 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.20 [0.63, 2.29] |

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without fetal heart rate changes | 1 | 48 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10 Epidural analgesia | 1 | 48 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.59, 1.37] |

| 11 Instumental vaginal delivery | 3 | 112 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.42, 1.29] |

| 12 Meconium‐stained liquor | 1 | 48 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.54 [0.28, 22.70] |

| 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 1 | 48 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.25, 2.00] |

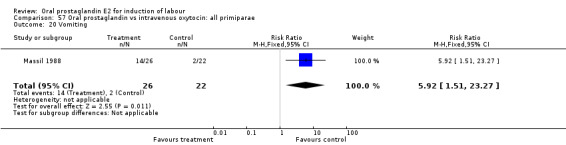

| 20 Vomiting | 1 | 48 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.92 [1.51, 23.27] |

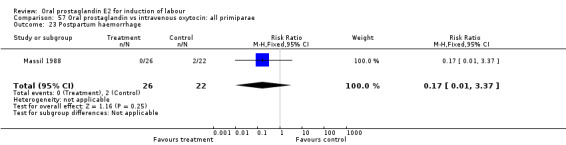

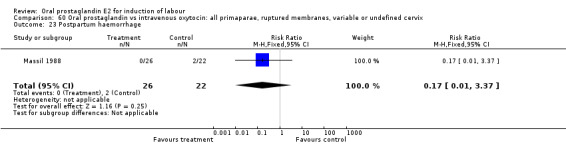

| 23 Postpartum haemorrhage | 1 | 48 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.17 [0.01, 3.37] |

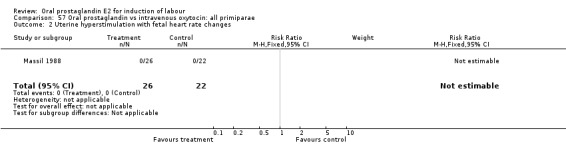

57.2. Analysis.

Comparison 57 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all primiparae, Outcome 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with fetal heart rate changes.

57.3. Analysis.

Comparison 57 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all primiparae, Outcome 3 Cesarean section.

57.8. Analysis.

Comparison 57 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all primiparae, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without fetal heart rate changes.

57.10. Analysis.

Comparison 57 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all primiparae, Outcome 10 Epidural analgesia.

57.11. Analysis.

Comparison 57 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all primiparae, Outcome 11 Instumental vaginal delivery.

57.12. Analysis.

Comparison 57 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all primiparae, Outcome 12 Meconium‐stained liquor.

57.14. Analysis.

Comparison 57 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all primiparae, Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

57.20. Analysis.

Comparison 57 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all primiparae, Outcome 20 Vomiting.

57.23. Analysis.

Comparison 57 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all primiparae, Outcome 23 Postpartum haemorrhage.

Comparison 58. Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all primiparae, unfavorable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

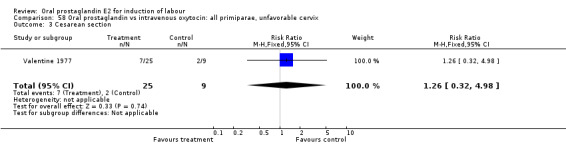

| 3 Cesarean section | 1 | 34 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.26 [0.32, 4.98] |

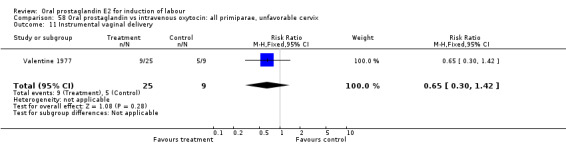

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 34 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.30, 1.42] |

58.3. Analysis.

Comparison 58 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all primiparae, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 3 Cesarean section.

58.11. Analysis.

Comparison 58 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all primiparae, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

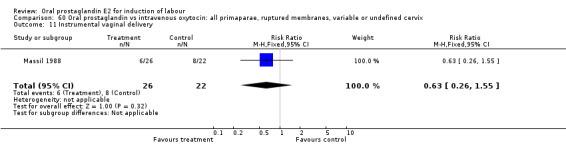

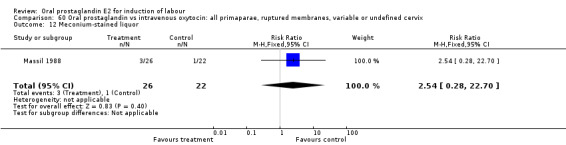

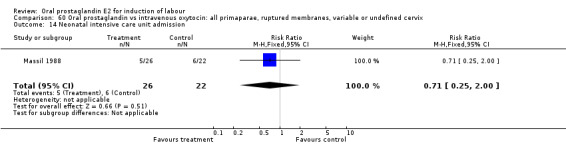

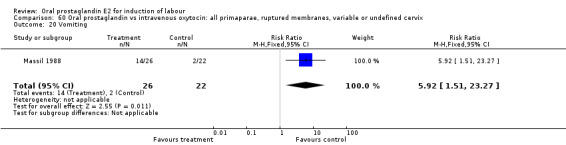

Comparison 60. Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all primaparae, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with fetal heart rate changes | 1 | 48 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Cesarean section | 1 | 48 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.67 [0.44, 134.99] |

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without fetal heart rate changes | 1 | 48 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10 Epidural analgesia | 1 | 48 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.90 [0.59, 1.37] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 48 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.63 [0.26, 1.55] |

| 12 Meconium‐stained liquor | 1 | 48 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.54 [0.28, 22.70] |

| 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 1 | 48 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.71 [0.25, 2.00] |

| 20 Vomiting | 1 | 48 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.92 [1.51, 23.27] |

| 23 Postpartum haemorrhage | 1 | 48 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.17 [0.01, 3.37] |

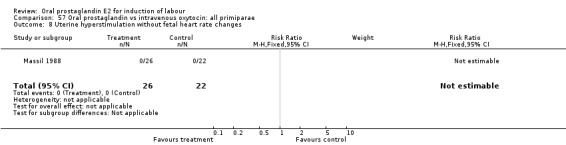

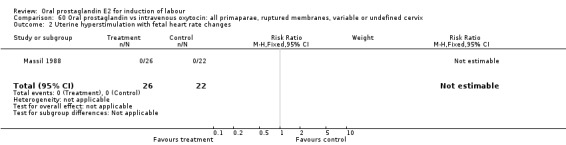

60.2. Analysis.

Comparison 60 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all primaparae, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with fetal heart rate changes.

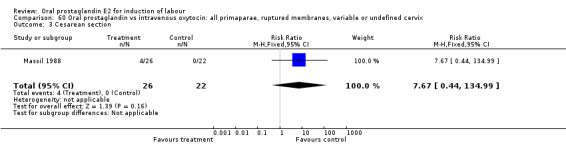

60.3. Analysis.

Comparison 60 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all primaparae, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 3 Cesarean section.

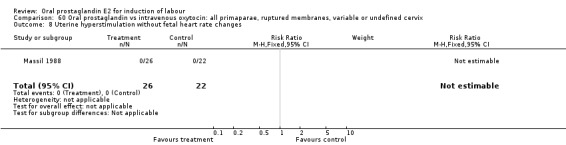

60.8. Analysis.

Comparison 60 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all primaparae, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without fetal heart rate changes.

60.10. Analysis.

Comparison 60 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all primaparae, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 10 Epidural analgesia.

60.11. Analysis.

Comparison 60 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all primaparae, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

60.12. Analysis.

Comparison 60 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all primaparae, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 12 Meconium‐stained liquor.

60.14. Analysis.

Comparison 60 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all primaparae, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

60.20. Analysis.

Comparison 60 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all primaparae, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 20 Vomiting.

60.23. Analysis.

Comparison 60 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all primaparae, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 23 Postpartum haemorrhage.

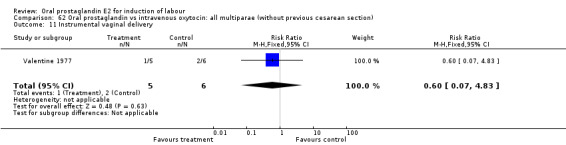

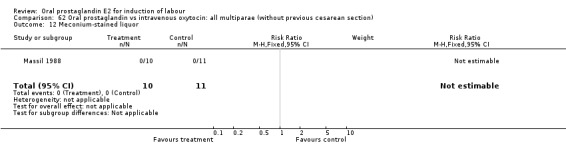

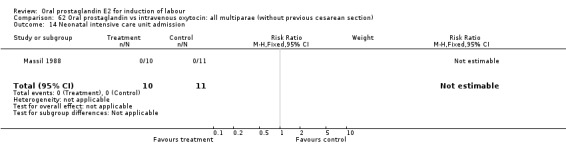

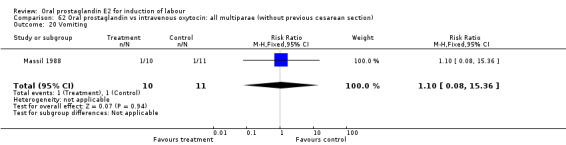

Comparison 62. Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all multiparae (without previous cesarean section).

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

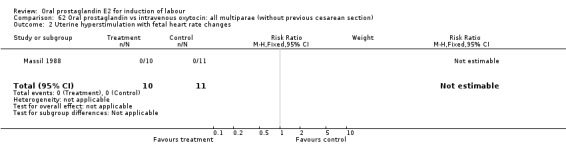

| 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with fetal heart rate changes | 1 | 21 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

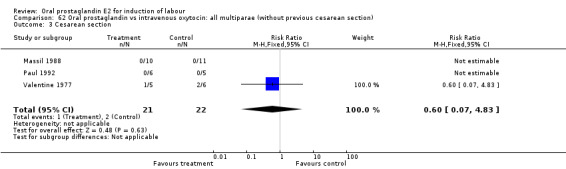

| 3 Cesarean section | 3 | 43 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.6 [0.07, 4.83] |

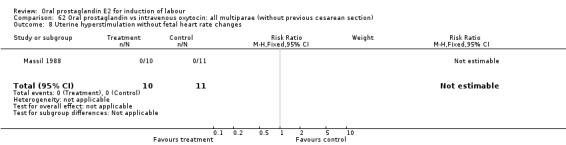

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without fetal heart rate changes | 1 | 21 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 11 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.6 [0.07, 4.83] |

| 12 Meconium‐stained liquor | 1 | 21 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 1 | 21 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

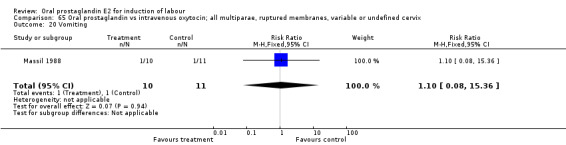

| 20 Vomiting | 1 | 21 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.1 [0.08, 15.36] |

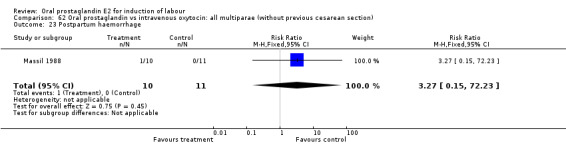

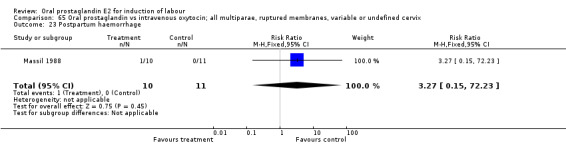

| 23 Postpartum haemorrhage | 1 | 21 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.27 [0.15, 72.23] |

62.2. Analysis.

Comparison 62 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all multiparae (without previous cesarean section), Outcome 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with fetal heart rate changes.

62.3. Analysis.

Comparison 62 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all multiparae (without previous cesarean section), Outcome 3 Cesarean section.

62.8. Analysis.

Comparison 62 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all multiparae (without previous cesarean section), Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without fetal heart rate changes.

62.11. Analysis.

Comparison 62 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all multiparae (without previous cesarean section), Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

62.12. Analysis.

Comparison 62 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all multiparae (without previous cesarean section), Outcome 12 Meconium‐stained liquor.

62.14. Analysis.

Comparison 62 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all multiparae (without previous cesarean section), Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

62.20. Analysis.

Comparison 62 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all multiparae (without previous cesarean section), Outcome 20 Vomiting.

62.23. Analysis.

Comparison 62 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all multiparae (without previous cesarean section), Outcome 23 Postpartum haemorrhage.

Comparison 63. Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all multiparae, unfavorable cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

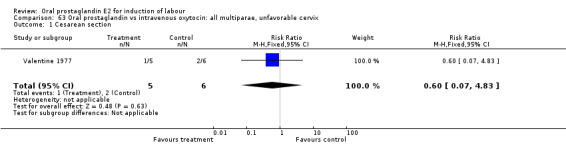

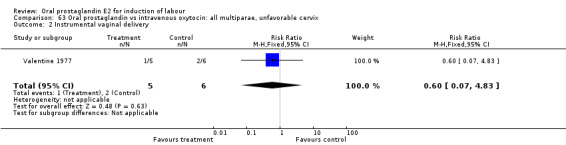

| 1 Cesarean section | 1 | 11 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.6 [0.07, 4.83] |

| 2 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 11 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.6 [0.07, 4.83] |

63.1. Analysis.

Comparison 63 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all multiparae, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 1 Cesarean section.

63.2. Analysis.

Comparison 63 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin: all multiparae, unfavorable cervix, Outcome 2 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

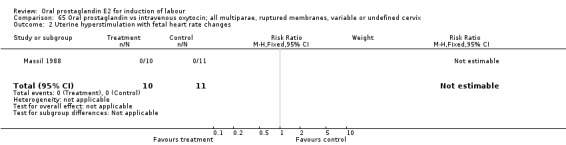

Comparison 65. Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin; all multiparae, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with fetal heart rate changes | 1 | 21 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3 Cesarean section | 1 | 21 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without fetal heart rate changes | 1 | 21 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10 Epidural analgesia | 1 | 21 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.55 [0.13, 2.38] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 21 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.27 [0.15, 72.23] |

| 12 Meconium‐stained liquor | 1 | 21 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission | 1 | 21 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 20 Vomiting | 1 | 21 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.1 [0.08, 15.36] |

| 23 Postpartum haemorrhage | 1 | 21 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.27 [0.15, 72.23] |

65.2. Analysis.

Comparison 65 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin; all multiparae, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 2 Uterine hyperstimulation with fetal heart rate changes.

65.3. Analysis.

Comparison 65 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin; all multiparae, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 3 Cesarean section.

65.8. Analysis.

Comparison 65 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin; all multiparae, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without fetal heart rate changes.

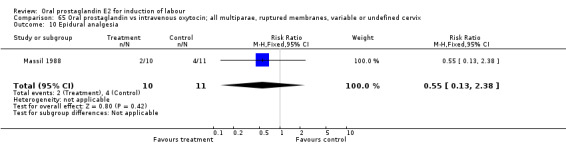

65.10. Analysis.

Comparison 65 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin; all multiparae, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 10 Epidural analgesia.

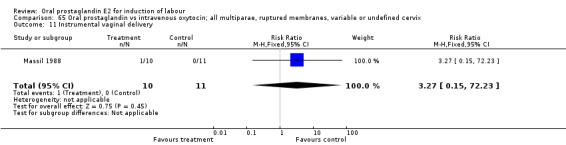

65.11. Analysis.

Comparison 65 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin; all multiparae, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

65.12. Analysis.

Comparison 65 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin; all multiparae, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 12 Meconium‐stained liquor.

65.14. Analysis.

Comparison 65 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin; all multiparae, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 14 Neonatal intensive care unit admission.

65.20. Analysis.

Comparison 65 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin; all multiparae, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 20 Vomiting.

65.23. Analysis.

Comparison 65 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin; all multiparae, ruptured membranes, variable or undefined cervix, Outcome 23 Postpartum haemorrhage.

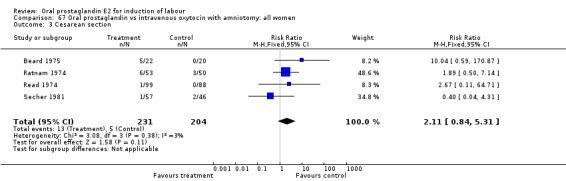

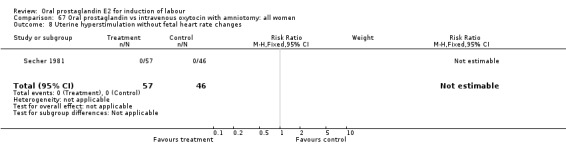

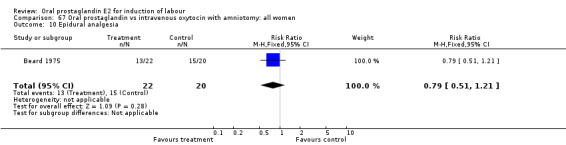

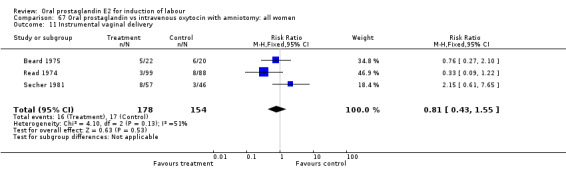

Comparison 67. Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin with amniotomy: all women.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Cesarean section | 4 | 435 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.11 [0.84, 5.31] |

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without fetal heart rate changes | 1 | 103 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 10 Epidural analgesia | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.51, 1.21] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 3 | 332 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.43, 1.55] |

| 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 2 | 145 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.12, 6.12] |

| 20 Vomiting | 2 | 229 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.60 [0.41, 31.59] |

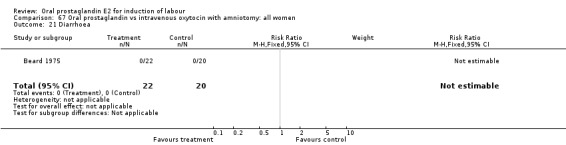

| 21 Diarrhoea | 1 | 42 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 23 Postpartum haemorrhage | 2 | 290 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

67.3. Analysis.

Comparison 67 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin with amniotomy: all women, Outcome 3 Cesarean section.

67.8. Analysis.

Comparison 67 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin with amniotomy: all women, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without fetal heart rate changes.

67.10. Analysis.

Comparison 67 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin with amniotomy: all women, Outcome 10 Epidural analgesia.

67.11. Analysis.

Comparison 67 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin with amniotomy: all women, Outcome 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery.

67.13. Analysis.

Comparison 67 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin with amniotomy: all women, Outcome 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes.

67.20. Analysis.

Comparison 67 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin with amniotomy: all women, Outcome 20 Vomiting.

67.21. Analysis.

Comparison 67 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin with amniotomy: all women, Outcome 21 Diarrhoea.

67.23. Analysis.

Comparison 67 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin with amniotomy: all women, Outcome 23 Postpartum haemorrhage.

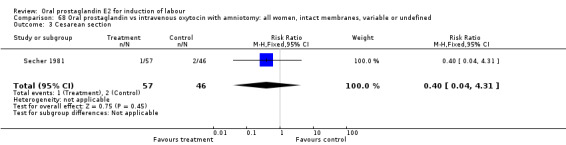

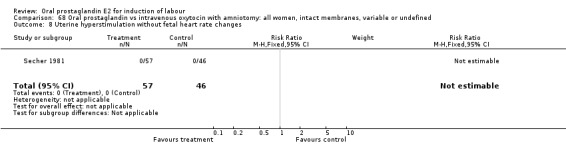

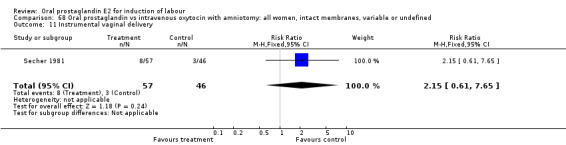

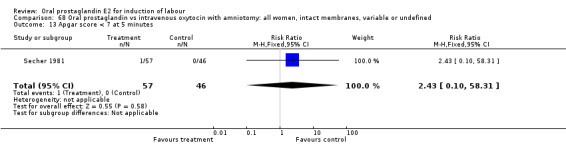

Comparison 68. Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin with amniotomy: all women, intact membranes, variable or undefined.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 Cesarean section | 1 | 103 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.40 [0.04, 4.31] |

| 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without fetal heart rate changes | 1 | 103 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 11 Instrumental vaginal delivery | 1 | 103 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.15 [0.61, 7.65] |

| 13 Apgar score < 7 at 5 minutes | 1 | 103 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.43 [0.10, 58.31] |

| 23 Postpartum haemorrhage | 1 | 103 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

68.3. Analysis.

Comparison 68 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin with amniotomy: all women, intact membranes, variable or undefined, Outcome 3 Cesarean section.

68.8. Analysis.

Comparison 68 Oral prostaglandin vs intravenous oxytocin with amniotomy: all women, intact membranes, variable or undefined, Outcome 8 Uterine hyperstimulation without fetal heart rate changes.

68.11. Analysis.