Abstract

Background

Maternal complications, including psychological/mental health problems and neonatal morbidity, have commonly been observed in the postpartum period. Home visits by health professionals or lay supporters in the weeks following birth may prevent health problems from becoming chronic, with long‐term effects. This is an update of a review last published in 2017.

Objectives

The primary objective of this review is to assess the effects of different home‐visiting schedules on maternal and newborn mortality during the early postpartum period. The review focuses on the frequency of home visits (how many home visits in total), the timing (when visits started, e.g. within 48 hours of the birth), duration (when visits ended), intensity (how many visits per week), and different types of home‐visiting interventions.

Search methods

For this update, we searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group's Trials Register, ClinicalTrials.gov, the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (19 May 2021), and checked reference lists of retrieved studies.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (including cluster‐, quasi‐RCTs and studies available only as abstracts) comparing different home‐visiting interventions that enrolled participants in the early postpartum period (up to 42 days after birth) were eligible for inclusion. We excluded studies in which women were enrolled and received an intervention during the antenatal period (even if the intervention continued into the postnatal period), and studies recruiting only women from specific high‐risk groups (e.g. women with alcohol or drug problems).

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trials for inclusion and risk of bias, extracted data and checked them for accuracy. We used the GRADE approach to assess the certainty of the evidence.

Main results

We included 16 randomised trials with data for 12,080 women. The trials were carried out in countries across the world, in both high‐ and low‐resource settings. In low‐resource settings, women receiving usual care may have received no additional postnatal care after early hospital discharge.

The interventions and controls varied considerably across studies. Trials focused on three broad types of comparisons, as detailed below. In all but four of the included studies, postnatal care at home was delivered by healthcare professionals. The aim of all interventions was broadly to assess the well‐being of mothers and babies, and to provide education and support. However, some interventions had more specific aims, such as to encourage breastfeeding, or to provide practical support.

For most of our outcomes, only one or two studies provided data, and results were inconsistent overall. All studies had several domains with high or unclear risk of bias.

More versus fewer home visits (five studies, 2102 women)

The evidence is very uncertain about whether home visits have any effect on maternal and neonatal mortality (very low‐certainty evidence). Mean postnatal depression scores as measured with the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) may be slightly higher (worse) with more home visits, though the difference in scores was not clinically meaningful (mean difference (MD) 1.02, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.25 to 1.79; two studies, 767 women; low‐certainty evidence). Two separate analyses indicated conflicting results for maternal satisfaction (both low‐certainty evidence); one indicated that there may be benefit with fewer visits, though the 95% CI just crossed the line of no effect (risk ratio (RR) 0.96, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.02; two studies, 862 women). However, in another study, the additional support provided by health visitors was associated with increased mean satisfaction scores (MD 14.70, 95% CI 8.43 to 20.97; one study, 280 women; low‐certainty evidence). Infant healthcare utilisation may be decreased with more home visits (RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.64; four studies, 1365 infants) and exclusive breastfeeding at six weeks may be increased (RR 1.17, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.36; three studies, 960 women; low‐certainty evidence). Serious neonatal morbidity up to six months was not reported in any trial.

Different models of postnatal care (three studies, 4394 women)

In a cluster‐RCT comparing usual care with individualised care by midwives, extended up to three months after the birth, there may be little or no difference in neonatal mortality (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.12; one study, 696 infants). The proportion of women with EPDS scores ≥ 13 at four months is probably reduced with individualised care (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.86; one study, 1295 women). One study suggests there may be little to no difference between home visits and telephone screening in neonatal morbidity up to 28 days (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.12; one study, 696 women). In a different study, there was no difference between breastfeeding promotion and routine visits in exclusive breastfeeding rates at six months (RR 1.47, 95% CI 0.81 to 2.69; one study, 656 women).

Home versus facility‐based postnatal care (eight studies, 5179 women)

The evidence suggests there may be little to no difference in postnatal depression rates at 42 days postpartum and also as measured on an EPDS scale at 60 days. Maternal satisfaction with postnatal care may be better with home visits (RR 1.36, 95% CI 1.14 to 1.62; three studies, 2368 women). There may be little to no difference in infant emergency health care visits or infant hospital readmissions (RR 1.15, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.38; three studies, 3257 women) or in exclusive breastfeeding at two weeks (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.18; 1 study, 513 women).

Authors' conclusions

The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of home visits on maternal and neonatal mortality. Individualised care as part of a package of home visits probably improves depression scores at four months and increasing the frequency of home visits may improve exclusive breastfeeding rates and infant healthcare utilisation. Maternal satisfaction may also be better with home visits compared to hospital check‐ups. Overall, the certainty of evidence was found to be low and findings were not consistent among studies and comparisons. Further well designed RCTs evaluating this complex intervention will be required to formulate the optimal package.

Plain language summary

Home visits in the early period after the birth of a baby

What is the issue?

Health problems for mothers and babies commonly occur or become apparent in the weeks following the birth. For the mothers these include postpartum haemorrhage (substitute excessive blood loss), fever and infection, abdominal and back pain, abnormal discharge (heavy or smelly vaginal discharge), thromboembolism (a blood clot), and urinary tract complications (being unable to control the urge to pee), as well as psychological and mental health problems such as postnatal depression. Mothers may also need support to establish breastfeeding. Babies are at risk of death related to infections (babies may be badly affected by infections), asphyxia (difficulties in breathing, caused by lack of oxygen), and preterm birth (being born prematurely).

Why is this important?

Home visits by health professionals or lay supporters in the early postpartum period may prevent health problems from becoming long‐term, with effects on women, their babies, and their families. This review looked at different home‐visiting schedules in the weeks following the birth.

What evidence did we find?

We included 16 randomised trials with data for 12,080 women. Some trials focused on physical checks of the mother and newborn, while others provided support for breastfeeding, and one included the provision of practical support with housework and childcare. They were carried out in both high‐resource countries and low‐resource settings where women receiving usual care may not have received additional postnatal care after early hospital discharge.

The trials focused on three broad types of comparisons: schedules involving more versus fewer postnatal home visits (five studies), schedules involving different models of care (three studies), and home versus facility postnatal check‐ups (eight studies). In all but four of the included studies, postnatal care at home was delivered by healthcare professionals. For most of our outcomes, only one or two studies provided data. Overall, our results were inconsistent.

The evidence was very uncertain about whether home visits reduced newborn deaths or serious health problems with the mother. Women's physical and psychological health were not improved with more intensive schedules of home visits although more individualised care improved women's mental health in one study and maternal satisfaction was slightly better in two studies. Overall, babies may be less likely to have additional medical care if their mothers received more postnatal home visits. More home visits may have encouraged more women to exclusively breastfeed their babies and women to be more satisfied with their postnatal care. The different outcomes reported in different studies, how the outcomes were measured, and the considerable variation in the interventions and control conditions across studies were limitations of this review. The certainty of the evidence was generally found to be low or very low according to the GRADE criteria.

What does this mean?

Increasing the number of postnatal home visits may promote infant health and exclusive breastfeeding and more individualised care may improve outcomes for women. More research is needed before any particular schedule of postnatal care can be recommended.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Schedules involving more versus fewer home visits in the early postpartum period.

| Schedules involving more compared to fewer postpartum visits for home visits in the early postpartum period | ||||||

| Patient or population: mothers and infants receiving home visits in the early postpartum period Setting: Canada, Denmark, Iran, Syria, Turkey, UK, USA, Zambia Intervention: schedules with more postpartum home visits Comparison: schedules with fewer postpartum home visits | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with fewer postpartum visits | Risk with more postpartum visits | |||||

| Maternal mortality within 42 days post‐birth | Study population | RR 0.39 (0.02 to 9.41) | 225 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW1 2 | ||

| 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | |||||

| Neonatal mortality | Study population | RR 0.99 (0.26 to 3.69) | 1281 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW3 4 | Data were provided from a 3‐arm trial ‐ with data eligible for 2 comparisons. | |

| 8 per 1000 | 8 per 1000 (2 to 30) | |||||

| Postnatal depression (last assessment up to 42 days postpartum) | Study population | 767 (2 RCTs) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW5 |

Postnatal depression measured on Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. The maximum score is 30 and any score above 10 is considered to indicate depression. | ||

| The mean postnatal depression score in the group with fewer postpartum visits ranged from 4.5 to 6.7 | MD 1.02 higher (0.25 higher to 1.79 higher) | |||||

| Maternal satisfaction with postnatal care | Study population | RR 0.96 (0.90 to 1.02) | 862 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW6 | Data were provided from a 3‐arm trial ‐ with data eligible for 2 comparisons | |

| 842 per 1000 | 809 per 1000 (758 to 859) | |||||

| Maternal satisfaction with postnatal care | Study population | 280 (1 RCT) |

LOW7,8 ⊕⊕⊝⊝ |

Mean satisfaction score at 8 weeks postpartum. Satisfaction questionnaire with possible range of 0‐170. Higher score indicates greater satisfaction. | ||

| The mean postnatal satisfaction score in the group with fewer postpartum visits was 139.9 | MD 14.70 higher (8.43 higher to 20.97 higher) | |||||

| Serious neonatal morbidity up to 6 months | Study population | ‐ | 0 (0 RCTs) | ‐ | No RCT reported this outcome | |

| ‐ | ‐ | |||||

| Exclusive breastfeeding (last assessment up to 6 weeks) | Study population | RR 1.17 (1.01 to 1.36) | 960 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW6 | ||

| 483 per 1000 | 565 per 1000 (488 to 657) | |||||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; MD: Mean difference; RCT: Randomised controlled trial; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1We downgraded 1 level for serious limitations in study design: unclear risk for detection, attrition and other bias and high risk for performance bias.

2We downgraded 2 levels for very serious imprecision: a single trial with wide 95%CI and small number of events.

3We downgraded 1 level for serious limitations in study design: unclear selection bias and high risk of bias for performance, detection, attrition and selective reporting bias.

4We downgraded 2 levels for very serious limitations in imprecision: wide 95% CI and small number of events.

5We downgraded 2 levels for very serious limitations in study design: performance, detection and attrition bias were at high risk.

6We downgraded 2 levels for very serious limitations in study design: selection bias was unclear risk and performance, detection, attrition and selective reporting were at high risk of bias.

7We downgraded 1 level for serious limitations in study design: performance bias was at high risk and detection, attrition and other bias were at unclear risk.

8We downgraded 1 level for serious imprecision due to a small sample size.

Background

Description of the condition

The postpartum period, defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the period from childbirth to the 42nd day following delivery (WHO 2005), is critical for both mothers and newborns. An estimated 295,000 maternal deaths occur worldwide each year because of pregnancy‐related complications in the antenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum periods, especially in resource‐limited settings (WHO 2019). These deaths are often sudden and unpredictable, with 11% to 17% occurring during childbirth itself and 50% to 71% occurring during the postpartum period (WHO 2005). Maternal health problems commonly observed in the postpartum period include postpartum haemorrhage, fever, abdominal and back pain, abnormal discharge, puerperal genital infection, thromboembolic disease, and urinary tract complications (Bashour 2008), as well as psychological and mental health problems, such as postnatal depression. The postpartum period is also critical for newborns. Every year, approximately 3.7 million babies die in the first four weeks of life. Most of these infants are born in developing countries and most die at home. Nearly 40% of all deaths of children younger than five years old occur within the first 28 days of life (neonatal or newborn period). Just three causes ‐ infections, asphyxia, and preterm birth ‐ account for nearly 80% of these deaths (WHO/UNICEF 2009). Moreover, the postpartum period is a time of transition for women and their families, who are adjusting on physical, psychological, and social levels (Shaw 2006). In most developed countries, postpartum hospital stays are often shorter than 48 hours following a vaginal birth; thus, most postpartum care is provided in community and ambulatory‐care settings. Early intervention in the postpartum period may prevent health problems from becoming chronic with long‐term effects on women, their babies, and their families.

Description of the intervention

The purpose of a home‐visiting program is to provide support at home for mothers, babies, and families by health professionals or skilled attendants. However, a single clearly defined methodology for this intervention does not exist. Further, the term "home visiting" is used differently in various contexts (AAP 2009). Since the 1970s, the length of hospital stay after childbirth has fallen dramatically in many high‐resource settings. Early postnatal discharge of healthy mothers and term infants does not appear to have adverse effects on breastfeeding or maternal depression when women are offered at least one nurse‐midwife home visit after discharge (Brown 2002). Home‐visiting programs provide breastfeeding and hygiene education, parenting and child health instruction, and general support to families; they successfully address many of the barriers to access, including transportation issues, initiation of timely care, and completeness of services (AAP 1998; AAP 2009). Several trials have assessed the impact of home‐visiting programs, especially effects on child abuse and neglect in vulnerable families (Donovan 2007; Olds 1997; Quinlivan 2003). Others focused on the effectiveness and cost‐effectiveness of intensive home‐visiting programs (Barlow 2007; Carabin 2005; McIntosh 2009). Some home‐visiting programs have specifically targeted high‐risk groups such as women suffering domestic abuse (intimate partner violence) or families that are economically or socially disadvantaged. Home‐visiting programs for high‐risk groups or those by child health nurses may include components during pregnancy and may continue over many months or years; such programs are outside the scope of this review and have been addressed in other Cochrane Reviews (Bennett 2008; Jahanfar 2013; Macdonald 2008; Turnbull 2012). In this review, we focus on the early postnatal period, following discharge from hospital.

In 2009, WHO and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) recommended home visits by skilled attendants in resource‐limited settings. In high‐mortality settings and where access to facility‐based care is limited, at least two home visits are recommended for all home births: the first visit should occur within 24 hours of the birth, the second visit on day three, and if possible, a third visit should be made before the end of the first week of life (day seven). For babies born in a healthcare facility, the first home visit was recommended to be made as soon as possible after the mother and baby return home, with remaining visits following the same schedule as for home births (WHO/UNICEF 2009).

A Cochrane Review demonstrated the effectiveness of community‐based intervention packages in improving neonatal outcomes and reducing maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality in resource‐limited settings; home visiting is the one of the main components in each of these intervention packages. This review offers encouraging evidence of the value of integrating maternal and newborn care in community settings (Lassi 2015). Therefore, we did not include intervention packages of continuous care, with components of antenatal or hospital care, in our review.

How the intervention might work

In high‐resource settings, healthy women and babies are frequently discharged from hospital within one or two days of the birth, and in low‐resource settings women may be discharged within hours of the birth, or may give birth at home (Brown 2002). Potentially, home visits by healthcare professionals or trained support workers within the first few days of the birth may offer opportunities for assessment of the mother and newborn, health education, infant feeding support, emotional or practical support and, if necessary, referral to other health professionals or agencies (Carabin 2005; Donovan 2007; Lassi 2015; Shaw 2006). Postpartum visits may prevent health problems developing or reduce their impact by early intervention or referral. Home visits have improved coverage of key maternal and newborn care practices such as early initiation of breastfeeding, exclusive breastfeeding, skin‐to‐skin contact, delayed bathing, attention to hygiene (e.g. hand washing and water quality), umbilical cord care, infant skin care. In addition, home visits may identify conditions that require additional care or check‐up, as well as counselling regarding when to take the mother and newborn to a healthcare facility (WHO/UNICEF 2009). Home visits may involve not only the assessment of the mother and newborn for physical problems but also assessment of maternal mental health, family circumstances and the home environment.

Depending on the context, home visits may take a non‐judgmental and supportive role or a more directive approach in which the goals are to monitor family compliance with standards of parenting care and ensure the newborn's health and welfare. The type of approach used can influence the ability of the carers to engage mothers and newborns, resulting in acceptance or rejection of the help offered and potential for further disengagement (Doggett 2005).

Why it is important to do this review

Despite many studies and reviews, evidence regarding the effectiveness of different types of home‐visiting programs in the early postnatal period is not sufficient. In some contexts once women have been discharged from hospital there may be no postnatal follow‐up, or very limited postnatal follow‐up. In higher‐resource settings, once women are at home, services may be provided by a range of health and social care agencies (newborn health visitors, social workers, paediatricians and general practitioners) and may be fragmented; postnatal home visits potentially allow continuity of care after hospital discharge and for the assessment and referral of the mother and newborn.

This Cochrane Review addresses the following questions: do different schedules of postpartum home‐visiting programs reduce maternal/neonatal mortality and morbidities, and if they do, what is the optimal schedule for postpartum home visits? This Cochrane Review includes reports evaluating the frequency, timing, duration and intensity of home visits. The optimal schedule has been set out by WHO/UNICEF 2009, however, there was no clear evidence underpinning recommendations. This is an update of a review last published in 2017.

Objectives

The primary objective of this review is to assess the effects of different home‐visiting schedules on maternal and newborn mortality during the early postpartum period. The review focuses on the frequency of home visits (how many home visits in total), the timing (when visits started, e.g. within 48 hours of the birth), duration (when visits ended), intensity (how many visits per week), and different types of home‐visiting interventions.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included studies that compared outcomes of participants after home visits with outcomes of those who received no home visits, or received different types of home‐visiting interventions. We included studies that used random or quasi‐random allocations of participants. The unit of allocation in eligible studies could be the individual or the group (i.e. cluster‐randomised). We also planned to include studies available only as abstracts, noting that these studies were awaiting assessment, pending publication of the full report. However, we did not identify any such study.

Types of participants

Eligible studies enrolled participants in the early postpartum period (up to 42 days after birth). We excluded studies in which women were enrolled and received an intervention during the antenatal period, even those in which the intervention continued into the postnatal period.

We planned to exclude studies that only recruited women from specific high‐risk groups (e.g. women identified with alcohol or drug problems), as interventions to support such women have been addressed elsewhere (Turnbull 2012).

Types of interventions

Interventions included scheduled home visiting in the postpartum period (excluding studies with antenatal home visiting in which the visits continued over many months). Interventions were home visits with various frequency, timings, duration and intensity.

We planned to include studies with co‐intervention(s). Home visits could include outreach visits to non‐healthcare facilities. Trials including a group that did not receive home visits would have been eligible.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Maternal mortality at 42 days post‐birth.

Neonatal mortality.

Secondary outcomes

Maternal outcomes

Maternal morbidities (postpartum haemorrhage, puerperal fever, abdominal and back pain, abnormal discharge, puerperal genital infection, thromboembolic disease, and urinary tract complications) within 42 days after birth.

Maternal mental health (depression, anxiety) and related problems (intimate partner violence, drug use) at 42 days after birth.

Satisfaction with overall care and service at 42 days after birth.

Contraceptive use (this outcome was not pre‐specified).

Neonatal outcomes

Neonatal morbidities (pneumonia, upper respiratory tract infection, diarrhoea, septic meningitis, encephalopathy or cerebral injury, and jaundice) within 28 days after birth.

Established feeding regimen (e.g. exclusive breastfeeding) at 28 days after birth.

Incomplete immunisation.

Failure to thrive, abuse, neglect, domestic violence from parents for any reason within 28 days after birth.

Infant health care utilisation (this outcome was not pre‐specified).

Serious neonatal morbidity up to six months (this outcome was not pre‐specified).

Search methods for identification of studies

The following methods section is based on a standard template used by Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth.

Electronic searches

For this update, we searched Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register by contacting their Information Specialist (19 May 2021).

The Register is a database containing over 27,000 reports of controlled trials in the field of pregnancy and childbirth. It represents over 30 years of searching. For full current search methods used to populate Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register including the detailed search strategies for CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase and CINAHL; the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service, please follow this link.

Briefly, Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth’s Trials Register is maintained by their Information Specialist and contains trials identified from:

monthly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE (Ovid);

weekly searches of Embase (Ovid);

monthly searches of CINAHL (EBSCO);

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Search results are screened by two people and the full text of all relevant trial reports identified through the searching activities described above is reviewed. Based on the intervention described, each trial report is assigned a number that corresponds to a specific Pregnancy and Childbirth review topic (or topics), and is then added to the Register. The Information Specialist searches the Register for each review using this topic number rather than keywords. This results in a more specific search set that has been fully accounted for in the relevant review sections (Included studies; Excluded studies; Studies awaiting classification; Ongoing studies).

In addition, we searched ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) for unpublished, planned and ongoing trial reports (19 May 2021) using the search methods detailed in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

(1) References from published studies

We searched the reference lists of relevant trials and reviews identified.

(2) Unpublished literature

We contacted authors for more details about the published trials/ongoing trials.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For methods used in the previous version of this review, see Yonemoto 2017.

For this update, the following methods were used for assessing 190 reports that were identified as a result of the updated search.

The following methods section is based on a standard template used by Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth.

Selection of studies

Two review authors (NY and SN) independently assessed eligibility for inclusion for all studies identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved discrepancies by discussion and by consulting a third review author (RM).

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, two review authors extracted the data using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, we consulted the third review author. Data were entered into Review Manager 5 software (RevMan 2020) and checked for accuracy.

When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we planned to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2019). Any disagreement was resolved by discussion or by involving a third review author.

(1) Random sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the method as:

low risk of bias (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

high risk of bias (any non‐random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear risk of bias.

(2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal allocation to interventions prior to assignment and assessed whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. telephone or central randomisation; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

high risk of bias (open random allocation; unsealed or non‐opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear risk of bias.

(3.1) Blinding of participants and personnel (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We considered that studies were at low risk of bias if they were blinded, or if we judged that the lack of blinding unlikely to affect results. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias for participants;

low, high or unclear risk of bias for personnel.

(3.2) Blinding of outcome assessment (checking for possible detection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used, if any, to blind outcome assessors from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We assessed blinding separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed methods used to blind outcome assessment as:

low, high or unclear risk of bias.

(4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias due to the amount, nature and handling of incomplete outcome data)

We described for each included study, and for each outcome or class of outcomes, the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported and the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomised participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported, or could be supplied by the trial authors, we planned to re‐include missing data in the analyses which we undertook.

We assessed methods as:

low risk of bias (e.g. no missing outcome data; missing outcome data balanced across groups);

high risk of bias (e.g. numbers or reasons for missing data imbalanced across groups; ‘as treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of intervention received from that assigned at randomisation);

unclear risk of bias.

(5) Selective reporting (checking for reporting bias)

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

low risk of bias (where it is clear that all of the study’s pre‐specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

high risk of bias (where not all the study’s pre‐specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre‐specified; outcomes of interest are reported incompletely and so cannot be used; study fails to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear risk of bias.

(6) Other bias (checking for bias due to problems not covered by (1) to (5) above)

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias.

(7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Handbook (Higgins 2019). With reference to (1) to (6) above, we planned to assess the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it is likely to impact on the findings. In future updates, we will explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses (see Sensitivity analysis).

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we presented results as summary risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Continuous data

We used the mean difference (MD) if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. In future updates, as appropriate, we will use the standardised mean difference to combine trials that measure the same outcome, but use different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

We included cluster‐randomised trials in the analyses along with individually randomised trials. When including cluster‐RCTs, we adjusted their sample sizes with methods described in the Handbook (Higgins 2019), using an estimate of the intra‐cluster correlation co‐efficient (ICC) derived from the trial, from a similar trial or from a study of a similar population. Where we used ICCs from other sources, we reported this and planned to conduct sensitivity analyses to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. We identified both cluster‐randomised trials and individually‐randomised trials, and we synthesised the relevant information provided there was little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomisation unit was considered to be unlikely.

Trials with multiple treatment arms

One trial with three arms has been included in this review as two separate studies (Bashour 2008a; Bashour 2008b); to avoid double counting, the control group data (events and sample) were shared between the two study comparisons.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, we noted levels of attrition as:

low risk of bias (indicates no missing data, or a low level of missing data, on an intention‐to‐treat (ITT) basis);

high risk of bias (indicates high level of missing data);

unclear risk of bias.

We planned to explore the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect by conducting sensitivity analyses (see Sensitivity analysis).

For all outcomes, we carried out analyses, as far as possible, on an ITT basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomised to each group in the analyses, and all participants were analysed in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of whether or not they received the allocated intervention. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number randomised, minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta‐analysis using the Tau², I² and Chi² statistics. We regarded heterogeneity as substantial if I² was greater than 30% and either Tau² was greater than zero, or there was a low P value (less than 0.10) in the Chi² test for heterogeneity. If we identified substantial heterogeneity (above 30%), we planned to explore it by pre‐specified subgroup analysis.

Assessment of reporting biases

In future updates, if there are 10 or more studies in the meta‐analysis, we will investigate reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We will assess funnel plot asymmetry visually. If asymmetry is suggested by a visual assessment, we will perform exploratory analyses to investigate it.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager 5 software (RevMan 2020). We planned to use fixed‐effect meta‐analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect: i.e. where trials were examining the same intervention, and the trials’ populations and methods were judged sufficiently similar. However due to the diversity of interventions in the trials, we used random‐effects meta‐analysis for all outcomes. The random‐effects summary was treated as the average of the range of possible treatment effects and we discussed the clinical implications of treatment effects differing between trials. If the average treatment effect is not clinically meaningful, we did not combine trials. If we used random‐effects analyses, the results were presented as the average treatment effect with 95% confidence intervals, and the estimates of Tau² and I².

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to perform a subgroup analysis according to the following clinically logical predefined groups.

Initiation of the intervention (within 48 hours after birth or later).

Duration of the intervention (less than three weeks versus three or more weeks).

Intensity or frequency of the intervention (less than one visit/week versus one or more visits/week.).

Person doing the visit: medical professional versus skilled attendant.

Parity: primiparity versus multiparity.

However, interventions in included trials were too heterogeneous to conduct the subgroup analyses planned as above. We therefore decided to conduct subgroup analyses by intensity/frequency of the intervention only, in the comparison of more home visits versus fewer home visits, as outlined below:

1. Any number of home visits versus no home visit.

2. Four or more home visits versus fewer than four home visits.

3. More home visits versus fewer home visits (both groups had more than four home visits).

We planned to assess differences between subgroups using interaction tests available in Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2020).

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to carry out sensitivity analyses to explore the effect of trial quality assessed by concealment of allocation, high attrition rates, or both, with poor quality studies being excluded from the analyses in order to assess whether this makes any difference to the overall result. There were too few trials included in any analysis, and so we were unable to carry out sensitivity analysis.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We assessed the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE approach, as outlined in the GRADE handbook. We assessed the certainty of the body of evidence relating to the following outcomes for the main comparison (schedules involving more versus fewer postpartum visits).

Maternal mortality at 42 days post‐birth

Neonatal mortality

Postnatal depression (last assessment up to 42 days postpartum)

Maternal satisfaction with postnatal care

Serious neonatal morbidity up to six months (this outcome was not pre‐specified)

Exclusive breastfeeding

We used GRADEpro GDT to import data from Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2020), and to create a 'Summary of findings' table. The GRADE approach uses five considerations (study limitations, inconsistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias) to assess the certainty of the body of evidence for each outcome. RCT data are initially considered to provide high‐certainty evidence, but based on assessment of these five domains, the certainty of evidence for a given outcome may be downgraded to moderate, low or very low. For each of these domains, the certainty of evidence may be downgraded by one level for serious concerns, or by two levels for very serious concerns.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

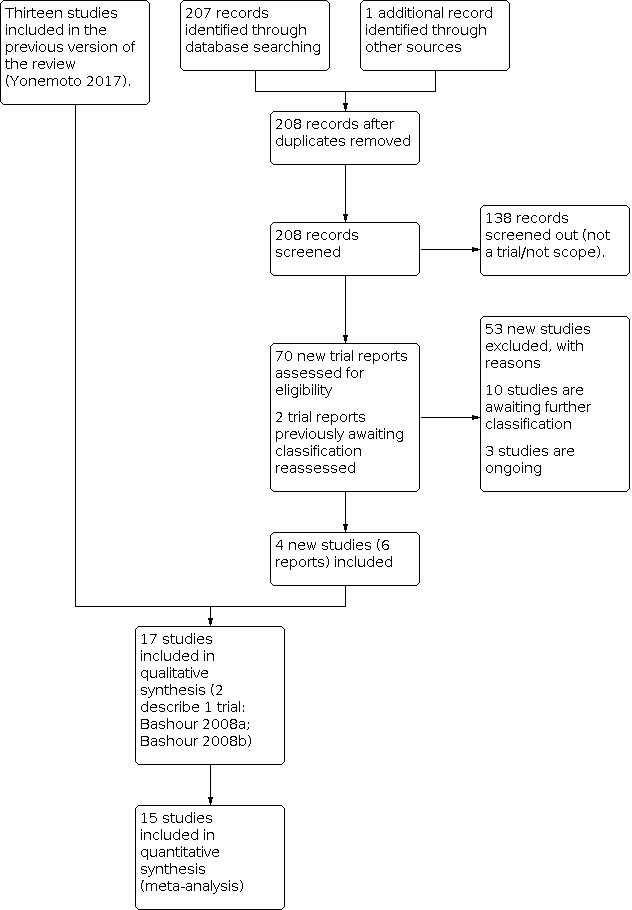

See: Figure 1

1.

Study flow diagram.

We assessed 69 new trial reports from the updated search, and one report from checking reference lists. We reassessed the two reports that were awaiting classification in the previous version of the review (Furnieles‐Paterna 2011; Salazar 2011). We included four new trials (six reports) and excluded 53 reports. Ten trials are awaiting classification and three trials are ongoing (Kristensen 2018; NCT04226807; NCT04257552).

Included studies

After assessing eligibility, we included 16 randomised trials with a total of 12,080 women (Aksu 2011; Bashour 2008a; Bashour 2008b; Christie 2011; Escobar 2001; Furnieles‐Paterna 2011; Gagnon 2002; Kronborg 2007; Lieu 2000; MacArthur 2002; Milani 2017; Mirmolaei 2014; Morrell 2000; Paul 2012; Ransjo‐Arvidson 1998; Salazar 2011; Steel 2003).

Design

Three of the trials (Christie 2011; Kronborg 2007; MacArthur 2002) were cluster‐randomised, with health centres or healthcare staff as the units of randomisation. For these trials, event rates and/or sample sizes have been adjusted in the analysis to take account of cluster design effect. One trial (Furnieles‐Paterna 2011) was quasi‐randomised, depending on the women's addresses.

One of the trials included three arms; women in the intervention groups received either four home visits or one home visit, while the control group received no home visits. In order for us to set out the results for all three groups, we have reported this trial as though it were two studies (Bashour 2008a; Bashour 2008b). In the Data and analyses, women receiving four home visits versus no home visits are entered under Bashour 2008a; whereas those receiving one home visit versus no home visits are compared in Bashour 2008b. The control group's number of events and number of participants in the sample have been divided between these comparisons, to avoid double counting.

Setting

The studies were carried out in countries across the globe in both high‐ and low‐resource settings. Three studies were carried out in the UK (Christie 2011; MacArthur 2002; Morrell 2000), three in the USA (Escobar 2001; Lieu 2000; Paul 2012), two in Canada (Gagnon 2002; Steel 2003), two in Iran (Milani 2017; Mirmolaei 2014), two in Spain (Furnieles‐Paterna 2011; Salazar 2011), and one each in Denmark (Kronborg 2007), Syria (Bashour 2008a; Bashour 2008b), Turkey (Aksu 2011), and Zambia (Ransjo‐Arvidson 1998). It is important to take the time and setting into account when interpreting results, as routine practice varied across time and in different settings. For example, in the UK, usual care may have involved up to seven home visits, whereas in other settings there may have been no postnatal care after hospital discharge.

Interventions and comparisons

The number and type of visits examined varied considerably across these trials, and control conditions also varied. Broadly, trials examined three types of comparisons: schedules involving more versus fewer postnatal home visits; schedules involving different models of care; and home versus hospital clinic postnatal follow‐up. In view of the complexity of interventions, we have set out the main components of interventions, and a description of control conditions in Table 2.

1. Description of interventions and control conditions.

| Name of study | Intervention | Control |

| STUDIES COMPARING MORE VS FEWER HOME VISITS | ||

|

Ransjo‐Arvidson 1998 4 home visits vs 1 home visit |

208 women randomised. Women were visited at home 4 times, at 3, 7, 28 and 42 days postpartum by a midwife. Each visit lasted about an hour. Women were asked about their own and their babies’ health but there was no formal health education. | 200 women received 1 visit by a midwife at about 42 days postpartum. |

|

Bashour 2008a; Bashour 2008b 4 vs 1 vs 0 home visits |

2 intervention groups: (1) Women (301) received 4 home visits on the first, 3rd, 7th day and 4 weeks after delivery. The aim of visits was to provide emotional support, assess maternal and infant health, assess the home, educate re breastfeeding and to discuss family planning. The visits were carried out by midwives. (2) Women (301) received a home visit on the first day only. The aim was to support and educate the woman and assess condition of mother and newborn. The visit was carried out by a midwife. |

301 women received normal care in Syria which was early discharge (as early as 2 hours following delivery) and no planned postnatal care. |

|

Christie 2011 6 health visitor home visits vs 1 |

136 women completed the pre‐test in the intervention group (referred by 39 health visitors). The intervention group received 6 health visitor visits between 10‐14 days and 8 weeks postpartum (approximately weekly visits). Health visitors provided advice and support, carried out assessments and offered health promotion. First visit 10‐14 days, 6 visits up to 8 weeks (weekly). |

159 women completed the pre‐test (nominated by 40 health visitors). The control group received 1 health visitor visit at 10‐14 days. Health visitors provided advice and support, carried out assessments and offered health promotion. Any further visits were discretionary. All women received usual postnatal care (midwife visits at home). |

|

Aksu 2011 Single postpartum visit vs no visit |

Women in both groups received standard care which included in‐hospital breastfeeding education. 33 women. Women were visited once at home 3 days after delivery by a trained supporter who provided advice and support. Visits lasted about 30 minutes. |

33 women received standard care which included breastfeeding education before hospital discharge. |

|

Morrell 2000 10 additional home visits vs 0 additional home visits |

All women received routine postnatal care at home from midwives and health visitors. 311 women received additional support from trained community support workers. Women received up to 10 visits lasting up to 3 hours between hospital discharge up to 28 days. Community workers helped with housework, caring for the baby and provided emotional support and reinforced midwife advice re breastfeeding. |

312 women received routine postnatal care which included home visits from community midwives and health visitors. Women received no additional visits from support workers Women in both groups received routine pp care with approximately 7 midwife visits and a health visitor visit. |

| STUDIES COMPARING DIFFERENT WAYS OF OFFERING CARE | ||

|

Steel 2003 Up to 2 home visits versus telephone screen by nurse and discretionary home visits |

353 women were telephoned on the first working day following discharge and arrangements were made for 2 home visits to take place within 10 days postpartum with the first visit being scheduled as soon as possible. The visits were structured to include infant assessment and public health nurse carrying out the visits could refer for other care if necessary. |

380 women were allocated to the telephone screen group. On the first working day following discharge women were phone by a public health nurse with a structured screening questionnaire and to elicit any concerns about feeding or the mother or infant’s health. A home visit was made if the nurse or mother thought one was needed (in 1 of the sites where home visits were routine care before the trial 54% of the women allocated to telephone screen had at least 1 home visit). |

|

Kronborg 2007 1‐3 structured postnatal visits by specially trained health visitors vs 1 or more unstructured health visitor visits. In this trial the intervention group did receive slightly more visits (mean 2.5 vs 2.1) but the main thrust of this intervention seemed to be the special HV training and the focus on promotion of breastfeeding through more structured visits. |

11 areas; 780 women recruited. The intervention included special health visitor training (18 hours) focusing on promoting breastfeeding. Health visitors then visited women at home on 1‐3 occasions and the visits were structured, focusing on breastfeeding continuation. Women received the first visit soon after hospital discharge and mothers with limited or no breastfeeding experience were offered up to 2 further visits focusing on breastfeeding (mean number of visits 2.5). It was not clear whether health visitors also offered standard care (i.e. covered content of visits as per control group). | 11 areas; 815 women. Health visitors received no additional training. Women were offered standard care which was 1 or more unstructured visits by health visitors up to 5 weeks postpartum. Women tended to receive approximately 2 home visits (mean 2.1); the content of visits was not specified. |

|

MacArthur 2002 Flexible visits vs routine care (scheduled visits) |

18 intervention practices (1 dropped out before recruitment of women) 1087 women recruited. Midwives were trained to provide a more flexible model of postnatal care responsive to women’s needs. There was no fixed schedule or number of postnatal visits. The number and content of visits at home was determined by midwives in consultation with women. After the initial visit a symptoms checklist was used and visits could take place up to 10‐12 weeks. (Midwife records suggest the mean number of visits was 6). It was not clear if women also received health visitor care. | 19 clusters, 977 women recruited. Routine care which “generally consists of 7 midwife home visits to 10‐14 days (can continue to day 28)” with care from health visitors thereafter. Mean number of midwife visits was approximately 4, it was not clear how many health visitor visits women received. |

| STUDIES COMPARING HOME VS FACILITY POSTNATAL CARE | ||

|

Furnieles‐Paterna 2011 Single home visit in first 48 hours after discharge plus routine check up at hospital vs single hospital visit |

100 women allocated to one puerperal home visit during the first 48 hours after discharge, and then the usual check‐up carried out in the health centre. | 100 women allocated to the usual check up at health centre. |

|

Lieu 2000 Single home visit vs single hospital visit |

580 women were allocated to receive a single home visit within 48 hours of hospital discharge by a nurse. Visits were scheduled to last 60‐90 minutes with some educational component. (This single visit was INSTEAD of rather than in additional to usual care; women received home visit rather than attending clinic visit in the hospital). | 583 women attended a 20 minute paediatric clinic visit within 48 hours of the birth. This visits may also have included some guidance and education. |

|

Escobar 2001 Single home visit vs single hospital (group or individual visit) |

508 women were allocated to receive a single home visit within 48 hours of hospital discharge by a nurse. Visits were scheduled to last 60‐90 minutes with some educational component. (This single visit was INSTEAD of rather than in additional to usual care; women received home visit rather than attending clinic visit in the hospital. 96% received a home visit as allocated although 75 women also attended for a hospital visit). |

506 women allocated to attend a 1‐2 hour group based visit where women (in groups of 5‐8). Women were offered newborn checks and guidance as part of group sessions. Multiparous women could opt for a 15‐minute paediatric clinic visit within 48 hours of the birth. This visit may also have included some guidance and education (157 had the group visit only, 264 the individual visit only, 64 both and 4 both home and hospital). |

|

Gagnon 2002 Single home visit vs single hospital visit |

All women received a nurse telephone contact at 48 hours post‐birth. 283 women were allocated to receive follow‐up at home at 3‐4 days postpartum. Home visits were by a community nurse. Visits were planned to last 1 hour and included newborn examination and guidance on infant care and breastfeeding. Women did not attend for hospital clinic visit at 3‐4 days (usual care). | All women received a nurse telephone contact at 48 hours post‐birth. 282 women were randomised to receive usual care which included a hospital clinic visit at 3‐4 days for newborn check and guidance on infant care and breastfeeding. Visits lasted up to 45 minutes (no home visit). |

|

Paul 2012 Single home visits vs single hospital visit |

576 women. Single visit by health visiting nurses within 48 hours of hospital discharge (typically 3‐5 days after the birth). The nurse had special training in promoting and supporting breastfeeding. | 578 women. Usual care. Clinic based postnatal follow‐up arranged by obstetricians. Women in both groups also had an office based visit for the baby approximately 1 week after the nurse visit or 5‐14 days after birth arranged by the hospital newborn nursery doctor). |

|

Milani 2017 2 home visits vs routine care (hospital based care) |

92 women recruited. The intervention was the postpartum health care providing at home on the 3–5th and 13–15th day after delivery according to the designed guideline. Healthcare providers were educated midwives. The average visit time was 30–45 minutes which would change with mothers' request. The intervention included greeting and recording checklists which were filled by midwives after interviewing and examining the mother and infant on each visit. | 184 women recruited. Usual hospital‐based care, if requested. It was only stated "lack of home visit". |

|

Mirmolaei 2014 2 home visits vs routine care (referral health service center) |

200 women recruited. Mothers and their neonates received the first postpartum care at health service centers in both groups. The intervention were second (10‐15 days), and third (42‐60 days) cares were provided by a trained midwife at home. Postpartum home visiting includes greeting and establishing an intimate relationship with the mother, identifying mother's SES and lifestyle, assessing vital signs, and recording checklists which were filled by midwives after interviewing and examining the mother and infant on each visit. | The control group received second and third cares provided by healthcare providers (mostly midwives) at a referral health service center. |

|

Salazar 2011 Attention at home within first week vs routine care (out‐patient clinic) |

213 women allocated to receive attention at home during the first week postpartum by a specialised nursing unit. | 217 women allocated to receive routine checks at days 7 and 30 at the out‐patient clinic. |

vs: versus

1. Schedules involving more versus fewer home visits

In five of our included studies, the main comparison was between women receiving more versus fewer home visits in the postnatal period.

Aksu 2011 examined the effect of one postnatal visit by a trained supporter versus no postnatal visits; Bashour 2008a; Bashour 2008b compared four or one postnatal home visits from midwives versus no home visits following hospital discharge. Ransjo‐Arvidson 1998 compared four midwife home visits versus one midwife home visit. In these three studies, carried out in low‐resource settings, women may have received no additional postnatal care.

In contrast, Christie 2011 and Morrell 2000 examined the impact of additional care in settings where women already received more than four postnatal visits from midwives as part of usual care. Christie 2011 compared groups receiving six health visitor visits versus one health visitor visit (in addition to midwifery care) and Morrell 2000 examined the impact of up to 10 visits from lay supporters; again, visits were provided in addition to routine midwifery care, which was available to women in both intervention and control groups. (In the Data and analyses tables, we have separated studies where women in both groups received more than four home visits, as the impact of interventions is likely to have been different from that in settings where women received no, or very limited postnatal care.)

2. Schedules comparing different models of postnatal care at home

Three studies examined different ways of providing postnatal care.

Steel 2003 compared the effects of two visits by public health nurses in the early postnatal period, compared with a telephone screening interview, with discretionary nurse home visits.

In a cluster‐RCT, Kronborg 2007 looked at the effects of more structured postnatal visits; women in the intervention group were visited between one and three times by health visitors who had attended special training on promoting and supporting breastfeeding. Women in the control group received usual care by health visitors who had not attended the breastfeeding courses.

MacArthur 2002 compared postnatal care that was adapted to the individual needs of women and home visits extended beyond the usual period of care (flexible visits up to 10 to 12 weeks postpartum). This was compared with usual care which involved a more rigid schedule of midwife home visits confined to the early postnatal period.

3. Home versus facility postnatal care

Eight of the included studies compared outcomes in women attending hospital clinics or for postnatal checks and follow‐up (usual care) versus home visits by nurses (Escobar 2001; Furnieles‐Paterna 2011; Gagnon 2002; Lieu 2000; Paul 2012; Salazar 2011) and educated midwives (Milani 2017; Mirmolaei 2014).

For all types of comparisons the purpose of visits was broadly similar: to assess the physical health and well being of mothers and babies (with referral for further care where necessary), to promote and support breastfeeding, to assess maternal emotional well being and to offer health education and support. In some cases the intervention focused on a particular aspect of care (e.g. breastfeeding), whereas other interventions were more general.

Outcomes

The outcomes measured in different studies varied. Most studies included some measure of maternal and infant health (although the particular outcomes measured, the way they were measured, and the time of follow‐up varied considerably between studies). Infant healthcare utilisation was also reported in a number of trials. Maternal emotional well being and rates of breastfeeding were reported in some of the studies, and a minority reported maternal satisfaction with postnatal care. For Mirmolaei 2014, data were not available for any of our outcomes.

Dates of the study

Results of trials were published between 1998 and 2017, although study data may have been collected some years before publication (e.g. in Ransjo-Arvidson 1998, women were recruited between 1989 and 1992).

Sources of trial funding

Eleven studies reported the source of trial funding and three studies had no information about funding source (please see details in Characteristics of included studies).

Trial authors' declarations of interest

Nine studies declared no conflict of interests, and seven studies had no information about conflict of interest (please see details in Characteristics of included studies).

Excluded studies

Fifty‐eight studies identified by the searches were excluded after assessing the full trial reports. Thirteen studies did not specifically examine postnatal home visits (Adachi 2016; Bagherinia 2017; Gunn 1997; Gunn 1998; Hannan 2013; Laliberte 2016; NCT00298311 2006; NCT01620723 2012; NCT03715218 2018; NCT03887910 2019; ; Pluym 2021; Roberts 2016; Simons 2001). Two studies were excluded as the intervention was for contraception (NCT02769676 2016; NCT03165838 2017). NCT03880032 2019 was excluded as the intervention was a cognitive behavioral therapy intervention for anxiety. Two studies were excluded as they focused on outcomes in women following early hospital discharge after the birth rather than on different schedules of home visits for women discharged at the same time (Boulvain 2004; Carty 1990). Eight studies were excluded as the intervention was given during antenatal period (Baur 2012; Goldfeld 2019; Gonzalez 2018; Gupta 2019; Harrison 2019; NCT02069782 2014; Tandon 2018; Tomlinson 2016). Three studies were excluded because they examined complex interventions that included components delivered during the antenatal period (Korfmacher 1999; Lumley 2006; Olds 2002). Park Himes 2017 examined complex interventions and did not separately analyse the home visit intervention. Six studies were excluded as the intervention was after six months (Dodge 2013a; Dodge 2019; Goodman 2019; Hutton 2017; Kilburn 2017; Olds 2002). Eight studies were excluded because they recruited mothers before birth (Catherine 2016; Hodgins 2020; Kikuchi 2015; Lakin 2015; McConnell 2016; Mohd Shukri 2019; Rotheram‐Borus 2017; Var 2015; Rotheram‐Borus 2014). Two studies were excluded because they randomised mothers 42 days after birth (Modi 2017; Sawyer 2017). Three studies were of observational design with random sampling or convenient sample (Dodge 2013b; Dodge 2014; Ghodsbin 2012). Hannan 2014 was a secondary analysis of a trial that did not include home visits. Paul 2013 was a secondary analysis of a trial with no comparison between groups. Two studies were a pre‐post test design (Jiao 2019; Navidian 2017). NCT03448289 2018 was an intervention trial with a single arm. One study, which recruited high‐risk women, involved intervention by child health nurses, rather than more general care of the mother and baby in the early postnatal period (Izzo 2005). Quinlivan 2003 focused on a high‐risk group rather than on the impact of different schedules of care. Finally, Stanwick 1982 was excluded for methodological reasons; there were major protocol deviations in this study, with many women in the intervention group failing to receive the intervention as planned, and analysis was carried out according to treatment received rather than by randomisation group (data were not available to allow us to restore women to their original randomisation groups).

Risk of bias in included studies

The included studies were mixed in terms of risk of bias; we were unable to carry out planned sensitivity analysis (temporarily excluding studies at high or unclear risk of bias for allocation concealment) as too few studies contributed data to allow any meaningful additional analysis.

We have set out the 'Risk of bias' assessments for individual studies in Figure 2 and for overall bias across all studies for different bias domains in Figure 3.

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

We judged 11 of the 16 included studies to be at low risk of bias because they used adequate methods to generate the randomisation sequence. Seven used computer‐generated sequences or external trial randomisation services (Aksu 2011; Escobar 2001; Gagnon 2002; Kronborg 2007; Lieu 2000; MacArthur 2002; Paul 2012) and five used random number tables (Christie 2011; Morrell 2000; Steel 2003; Mirmolaei 2014; Salazar 2011). In three trials (Bashour 2008aBashour 2008bMilani 2017Ransjo‐Arvidson 1998), it was not clear how the randomisation sequence was decided. Furnieles‐Paterna 2011 used a quasi‐randomised method, so we assessed this study to be at high risk of bias.

Concealment of group allocation at the point of randomisation was assessed as being at low risk of bias in nine studies; five trials reported using sequentially numbered, sealed envelopes to conceal allocation (Bashour 2008a; Bashour 2008b; Escobar 2001; Lieu 2000; Morrell 2000; Steel 2003) and four used external randomisation services (Christie 2011; Gagnon 2002; Furnieles‐Paterna 2011; Kronborg 2007; MacArthur 2002). In the trials by Aksu 2011, Paul 2012, Ransjo‐Arvidson 1998, Milani 2017, Mirmolaei 2014, and Salazar 2011, the methods used to conceal allocation were not described, or were not clear.

Blinding

Blinding women and care providers to this type of intervention is not generally feasible and no attempts to achieve blinding for these groups were described. All studies were judged to be at high risk of bias for this domain. It is possible that lack of blinding may have been an important source of bias.

In eight of the trials, it was reported that outcome assessors were blind to group allocation (Bashour 2008a; Bashour 2008b; Escobar 2001; Furnieles‐Paterna 2011; Gagnon 2002; Lieu 2000; MacArthur 2002; Paul 2012; Steel 2003). However, with the exception of Gagnon 2002, who took extra precautions to ensure blinding (where outcome data were assessed by interview), women may have revealed their treatment group, and it was not clear whether or not blinding was successful; none of the trialists reported checking the success of blinding. Blinding of outcome assessors was either not attempted or not mentioned in the remaining eight trials (Aksu 2011; Christie 2011; Kronborg 2007; Morrell 2000; Ransjo‐Arvidson 1998; Milani 2017; Mirmolaei 2014; Salazar 2011).

Incomplete outcome data

In nine of the included trials, sample attrition and missing data did not appear to be important sources of bias (assessed as low or unclear risk of bias) (Bashour 2008a; Bashour 2008b; Christie 2011; Escobar 2001; Furnieles‐Paterna 2011; Lieu 2000; Paul 2012; Steel 2003; Mirmolaei 2014; Salazar 2011). In some trials, although attrition was balanced across groups, there was more than 10% loss to follow‐up. In the Aksu 2011 trial, the response rate at four months postpartum was 82%; 16% were lost to follow‐up in the Kronborg 2007 study and 15% were lost to follow‐up in the trials by Gagnon 2002 and Ransjo‐Arvidson 1998. By four months postpartum, more than 20% of the sample were lost to follow‐up in the MacArthur 2002 trial, and a whole cluster was also excluded post‐randomisation in the home visit group; this trial was judged to be at high risk of attrition bias. Loss to follow‐up was not balanced in the intervention and control groups in the Morrell 2000 study. In this study, while the response rate was 83% for those women receiving additional postnatal visits, it was only 75% in the control group.

Selective reporting

Assessing selective reporting bias is not easy without access to study protocols, and for all studies included in the review, risk of bias was assessed from published study reports. In most, but not all of the studies, the primary outcomes were specified in the methods section and trialists reported results for these outcomes. We were unable to carry out planned investigation of possible publication bias by generating funnel plots as too few studies contributed data. We assessed whether appropriate outcomes were reported in the trial, if the trial registration number was available.

Other potential sources of bias

In most of the studies there were no other obvious sources of bias. In four of the trials, there was some imbalance between groups at baseline (Escobar 2001; Gagnon 2002; Lieu 2000; Morrell 2000). In the Steel 2003 study, women were recruited in two study areas and usual practice was different in each area and this led to protocol deviations; again, it is not clear how this would have affected results. Finally, in the Ransjo‐Arvidson 1998 trial, much of the analysis related to the intervention group only. In addition, the nature of the intervention may have affected findings. Midwives asked women about their health as part of the intervention, so women in the intervention group were asked repeatedly to identify health problems; whereas women in the control group were only asked as part of follow‐up assessments. This may have affected recall and introduced a risk of response bias. This trial may also have had the potential for publication bias, because the publication date was more than six years after study completion.

The three cluster‐randomised trials included in the review (Christie 2011; Kronborg 2007; MacArthur 2002) appeared to have comparable groups at baseline, and adjusted their results to take account of the cluster effect in their analyses. In the cluster trial reported by Christie 2011, health visitors were the unit of randomisation and it appeared that there were differences between health visitors in terms of the number of women recruited to the trial and in their practices; the impact of these differences in individual practices is unclear.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Schedules involving more versus fewer home visits (five trials with 2102 women)

In five included studies, the main comparison was between women receiving more versus fewer home visits in the postnatal period (Aksu 2011; Bashour 2008a; Bashour 2008b; Christie 2011; Morrell 2000; Ransjo‐Arvidson 1998). One trial included three arms, and in order to report findings for its two different intervention groups, we treated this trial as though it were two separate studies (Bashour 2008a; Bashour 2008b). One of the trials (Christie 2011) was a cluster‐randomised trial, and in the data and analyses tables we have used the effective sample size and event rates (adjusted for cluster design effect). See Table 3 for details of these adjustments.

2. Adjustments for cluster trials.

| Trial | Outcome | Average cluster size | ICC | DE | Original sample | Adjusted sample |

GIV data |

| Christie 2011 | Analysis 1.1 Maternal mortality |

3.7 (reported in trial) |

Based on data below as not reported for this outcome | 1.243 | I = 129 C = 151 |

I = 104 C = 121 Cant do this for number of events as only one event |

Not reported |

| Analysis 1.11 Depression |

3.7 (reported in trial) |

0.09 (reported in trial) | 1.243 | I = 129 C = 151 |

I = 104 C = 121 |

1.26 (0.16, 2.36) | |

| Analysis 1.12 Anxiety |

3.7 (reported in trial) |

0 | 1 | I = 129 C = 151 |

NA | 2.11 (‐1.64, 5.86) | |

| Analysis 1.14 Satisfaction |

3.7 (reported in trial) |

0 | 1 | I = 129 C = 151 |

NA | 14.51 (7.7, 21.28) | |

| Analysis 1.20 Any breastfeeding |

3.7 (reported in trial) |

0.03 (reported in trial) |

1.081 | I = 29/129 C = 36/151 |

I = 27/119 C = 33/140 |

0.94 (0.33, 1.01) | |

| Analysis 1.25 Infant health utilisation |

3.7 (reported in trial) |

0.02 (reported in trial) |

1.054 | I = 9/129 C = 23/151 |

I = 9/122 C = 22/143 |

0.36 (0.15, 0.85) |

Aksu 2011 examined the effect of one postnatal visit versus no postnatal visits; Bashour 2008a; Bashour 2008b examined four home visits or one home visit versus no home visits; Ransjo‐Arvidson 1998 examined four home visits versus one home visit. Christie 2011 and Morrell 2000 examined the impact of additional care in settings where women already received more than four visits as part of usual care. Christie 2011 compared groups receiving six health visitor visits versus one health visitor visit (in addition to midwifery care). Morrell 2000 examined up to 10 lay supporter visits versus no additional visits, with routine midwifery care available to women in both the intervention and control groups. (In the Data and analyses tables, we have separated studies where women in both groups received more than four home visits.)

For many of our prespecified outcomes, only one or two studies contributed data, and results were not always available for all women randomised. For each result, we have specified the number of studies and women for whom data were available (for cluster‐randomised trials, these are the adjusted figures). We anticipated that the treatment effect might differ in trials comparing different numbers of visits; we therefore used a random‐effects model for all analyses in this comparison.

Primary outcomes

Maternal mortality up to 42 days postpartum

Only one trial reported this outcome (Christie 2011). The evidence is very uncertain about whether there is any difference in maternal mortality between groups receiving additional health visitor visits, compared with controls. Only one death reported in the additional health visitor visits group (RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.02 to 9.41; one study with 225 women, very low‐certainty evidence;Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Schedules involving more versus fewer home visits, Outcome 1: Maternal mortality within 42 days post‐birth

Neonatal mortality

Two trials reported on neonatal death (Bashour 2008a; Bashour 2008b; Ransjo‐Arvidson 1998); there was no strong evidence that more visits were associated with fewer deaths. The evidence was assessed to be very uncertain about the effects of the intervention on neonatal mortality (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.26 to 3.69; three studies, 1281 women; very low‐certainty evidence;Analysis 1.2). Similarly, women receiving one or four home visits versus no home visits, or four or more home visits versus one home visit, showed very uncertain results for neonatal deaths (RR 3.06, 95% CI 0.37 to 25.39; one study, 873 women; and RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.09 to 2.60; one study, 408 women; respectively).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Schedules involving more versus fewer home visits, Outcome 2: Neonatal mortality

Secondary outcomes

Severe maternal morbidity

Two studies reported this outcome. Bashour 2008a; Bashour 2008b reported the number of women seeking medical help for a health problem and Ransjo‐Arvidson 1998 reported the number of women in whom a doctor had identified a problem up to 42 days. The numbers of women with problems were very similar in intervention and control groups, and the evidence suggested that there may be little to no difference between groups either overall, or for women receiving different patterns of visits (overall RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.15, two studies, 1228 women; four visits or one visit versus no visits RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.17, one study, 876 women; and, four visits versus one visit RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.54, one study, 352 women; Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Schedules involving more versus fewer home visits, Outcome 3: Severe maternal morbidity

Maternal health problems up to 42 days

Only one study reported results for most of our pre‐specified outcomes relating to maternal postpartum health problems up to 42 days after the birth (Bashour 2008a; Bashour 2008b). There may be little to no difference between women receiving four or one postnatal home visits versus no postnatal home visits for secondary postpartum haemorrhage (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.26; two studies, 873 women; Analysis 1.4); abdominal pain (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.34; two studies, 869 women; Analysis 1.5); back pain (RR 0.96, 95% 0.83 to 1.11; two studies, 871 women; Analysis 1.6); urinary tract complications (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.10; two studies, 876 women; Analysis 1.7); fever (RR 1.30, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.82; two studies, 876 women; Analysis 1.8) or dyspareunia (RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.90 to 1.55; two studies, 869 women; Analysis 1.9). No studies reported on thromboembolic disease or puerperal genital tract infections.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Schedules involving more versus fewer home visits, Outcome 4: Secondary postpartum haemorrhage

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Schedules involving more versus fewer home visits, Outcome 5: Abdominal pain up to 42 days postpartum

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Schedules involving more versus fewer home visits, Outcome 6: Back pain up to 42 days postpartum

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Schedules involving more versus fewer home visits, Outcome 7: Urinary tract complications up to 42 days postpartum

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Schedules involving more versus fewer home visits, Outcome 8: Maternal fever up to 42 days postpartum

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Schedules involving more versus fewer home visits, Outcome 9: Dyspareunia

One study reported mean scores on a scale measuring maternal perceptions of their general health at six weeks postpartum (Morrell 2000). The evidence suggested that there were little or no differences between women receiving additional postnatal support and controls (MD ‐1.60, 95% CI ‐4.72 to 1.52; one study, 539 women; Analysis 1.10). The score was measured using the SF‐36 general perception domain. A high score on this instrument means good general heath perception.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Schedules involving more versus fewer home visits, Outcome 10: Maternal perception of general health at 6 weeks (mean SF36)

Postnatal depression and anxiety