Abstract

Background

Depression is common in young people. It has a marked negative impact and is associated with self‐harm and suicide. Preventing its onset would be an important advance in public health. This is an update of a Cochrane review that was last updated in 2011.

Objectives

To determine whether evidence‐based psychological interventions (including cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy (IPT) and third wave CBT)) are effective in preventing the onset of depressive disorder in children and adolescents.

Search methods

We searched the specialised register of the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group (CCMDCTR to 11 September 2015), which includes relevant randomised controlled trials from the following bibliographic databases: The Cochrane Library (all years), EMBASE (1974 to date), MEDLINE (1950 to date) and PsycINFO (1967 to date). We searched conference abstracts and reference lists of included trials and reviews, and contacted experts in the field.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials of an evidence‐based psychological prevention programme compared with any comparison control for young people aged 5 to 19 years, who did not currently meet diagnostic criteria for depression.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed trials for inclusion and rated their risk of bias. We adjusted sample sizes to take account of cluster designs and multiple comparisons. We contacted trial authors for additional information where needed. We assessed the quality of evidence for the primary outcomes using GRADE.

Main results

We included 83 trials in this review. The majority of trials (67) were carried out in school settings with eight in colleges or universities, four in clinical settings, three in the community and four in mixed settings. Twenty‐nine trials were carried out in unselected populations and 53 in targeted populations.

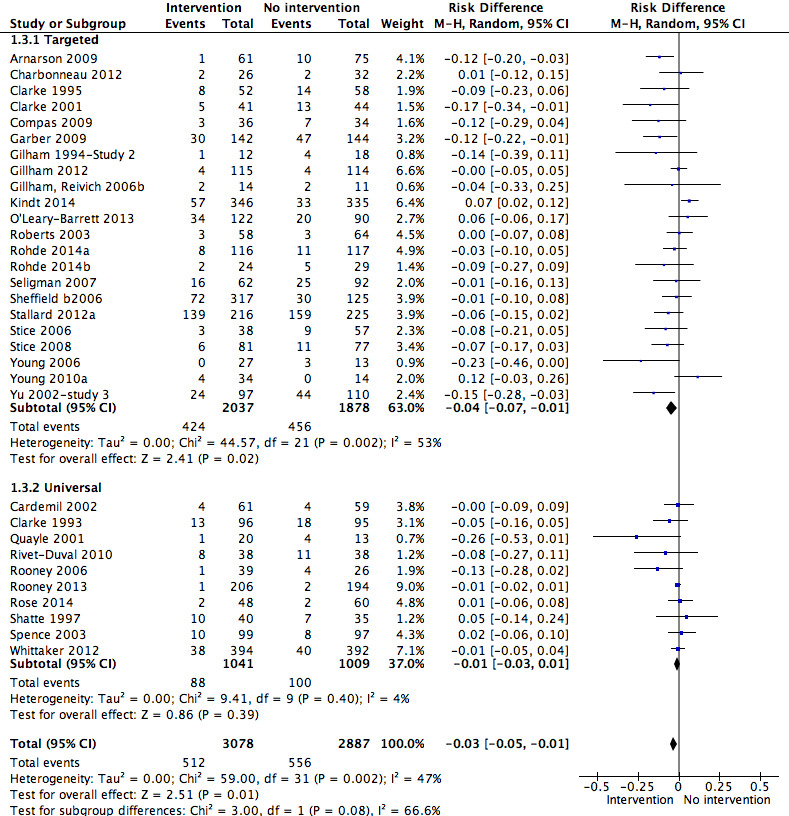

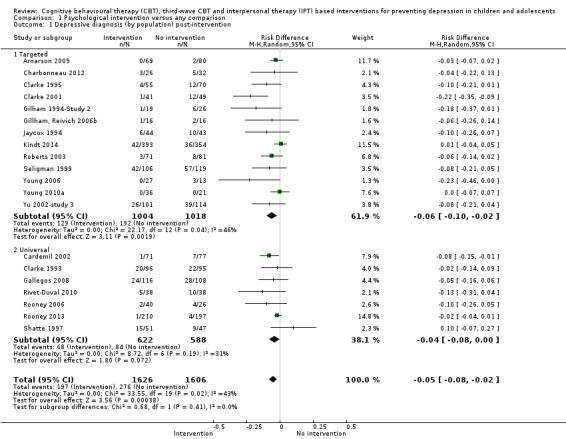

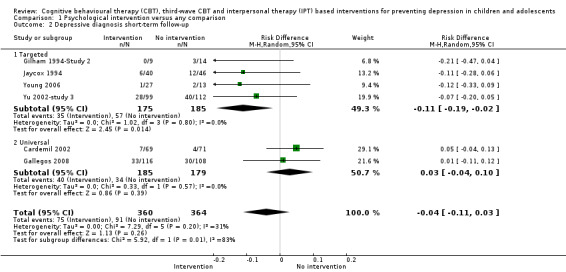

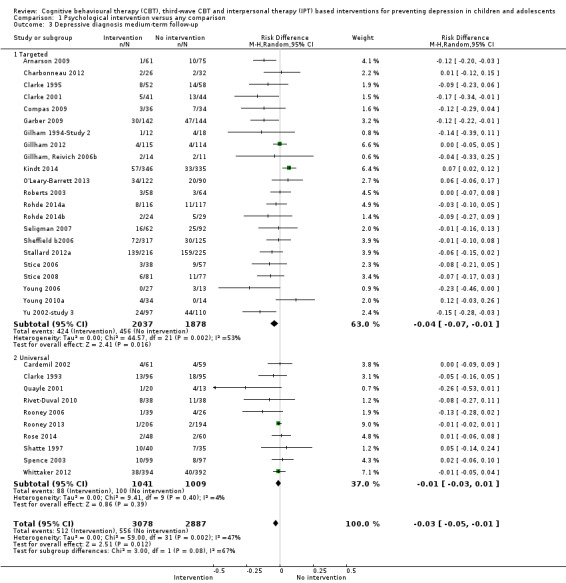

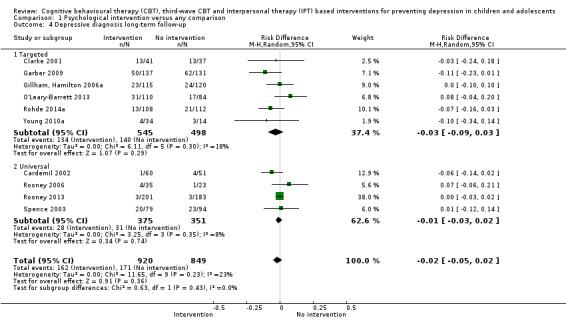

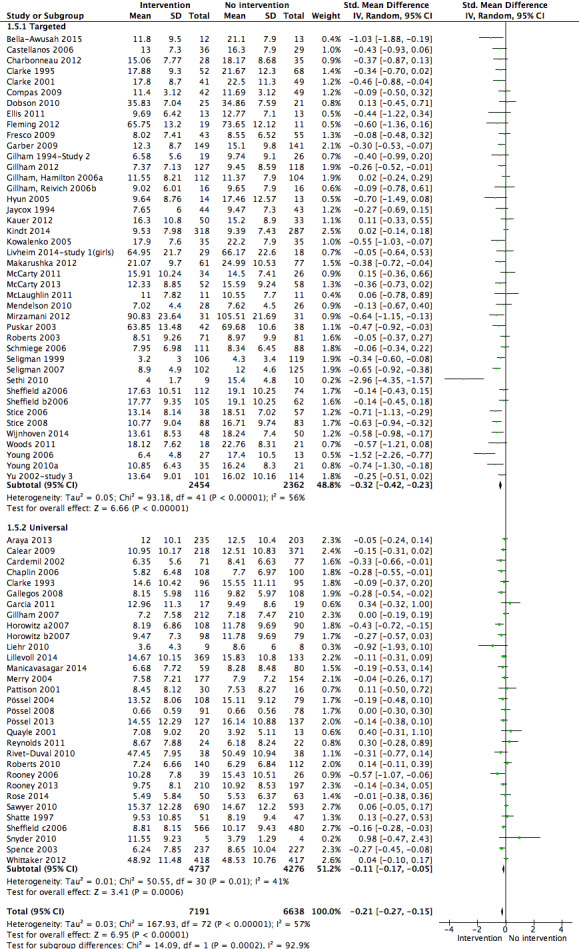

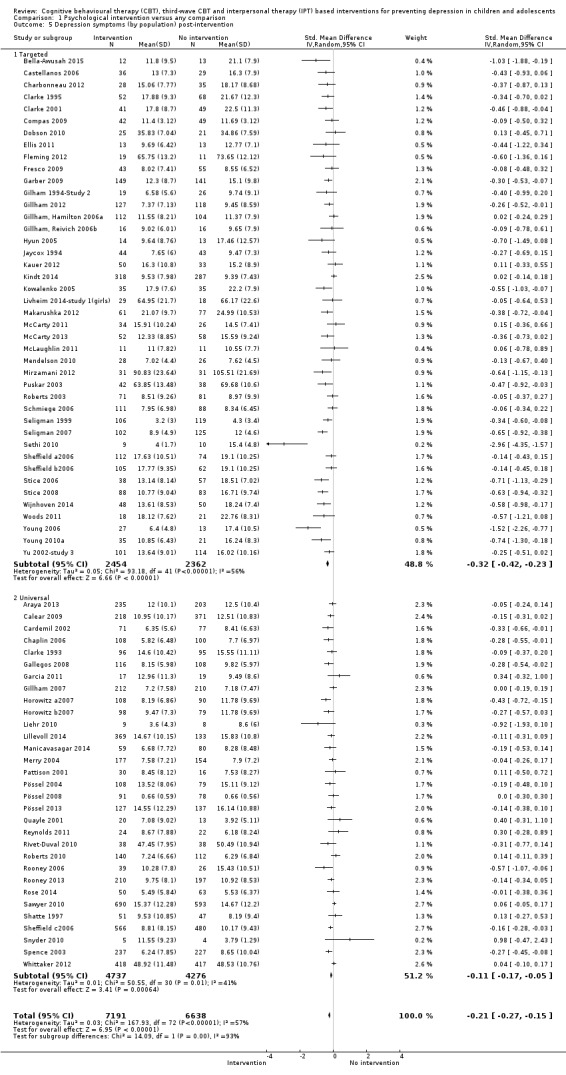

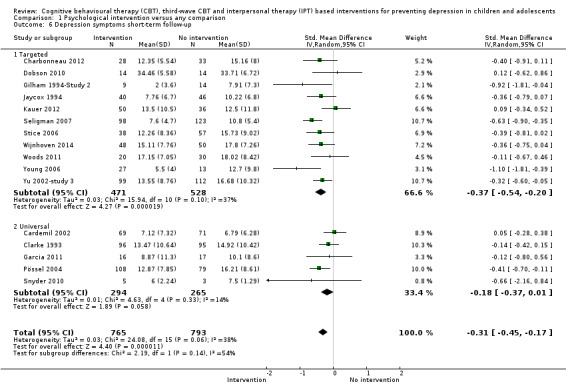

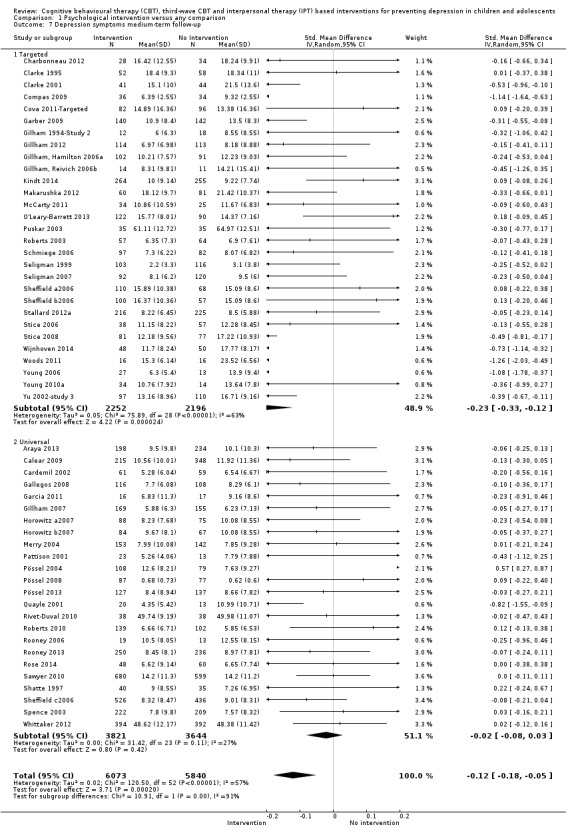

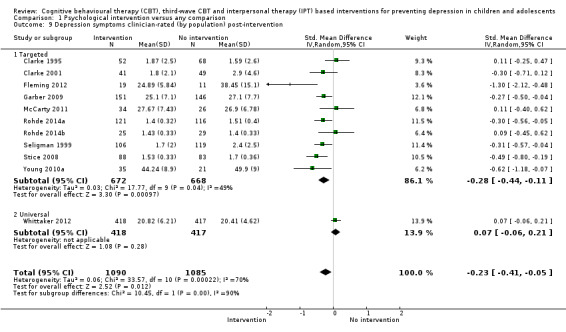

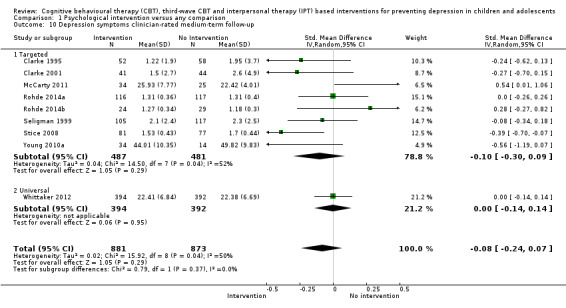

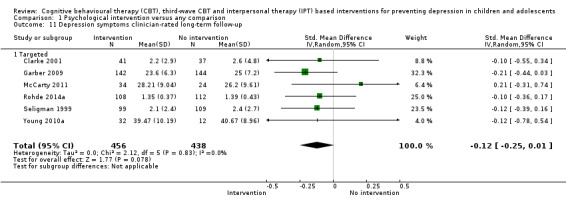

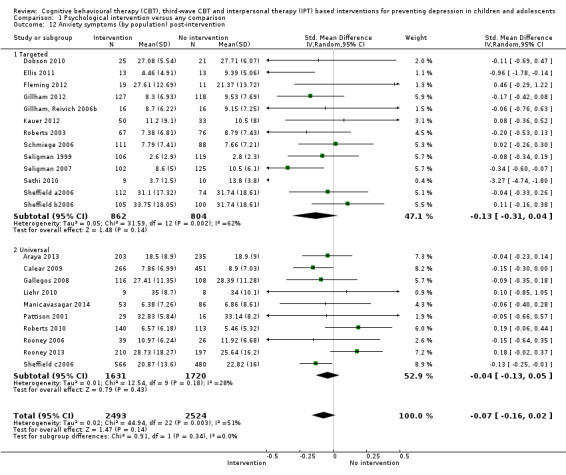

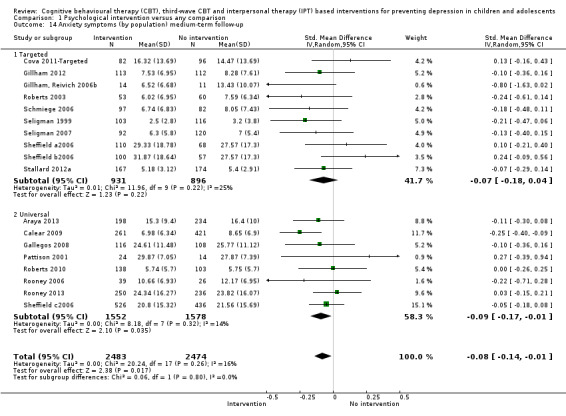

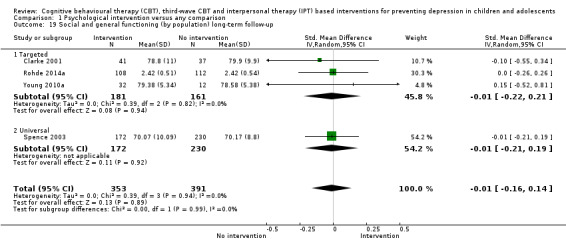

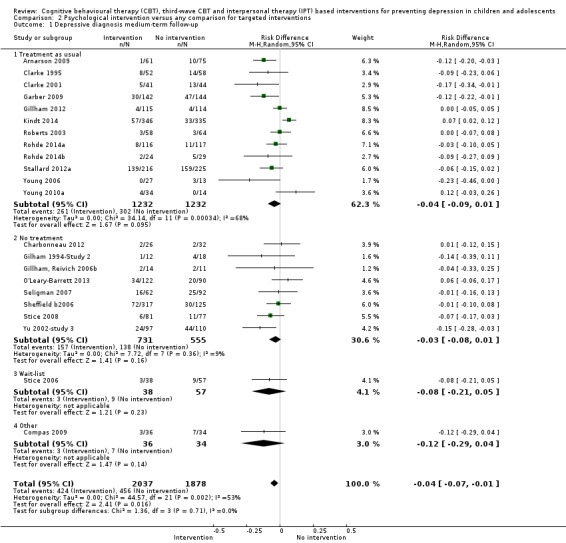

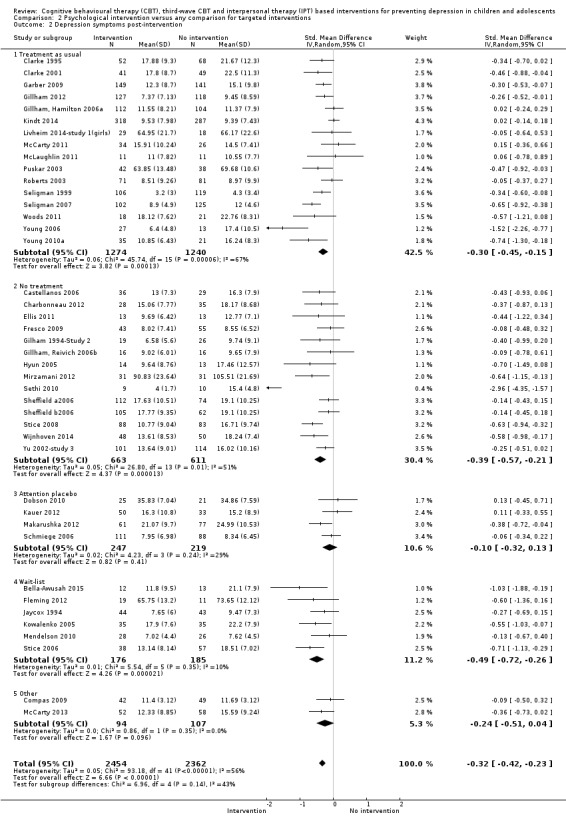

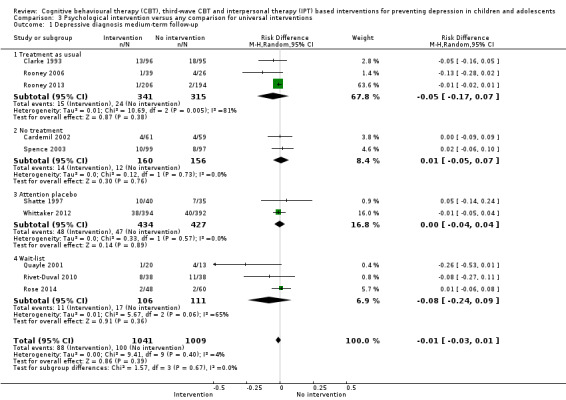

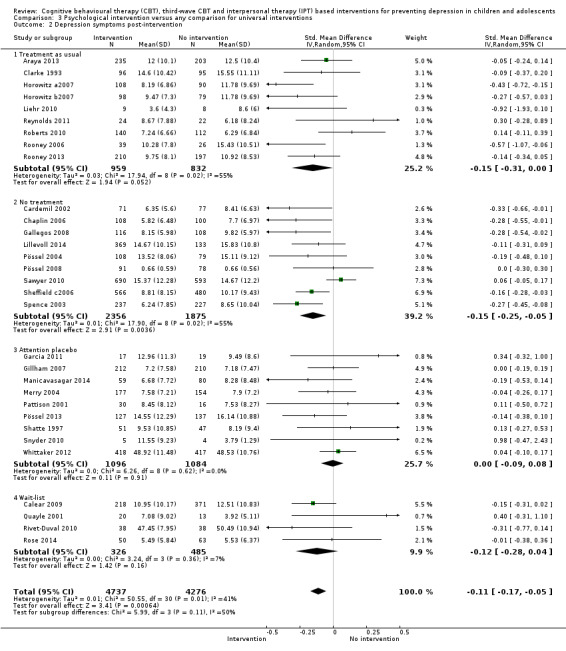

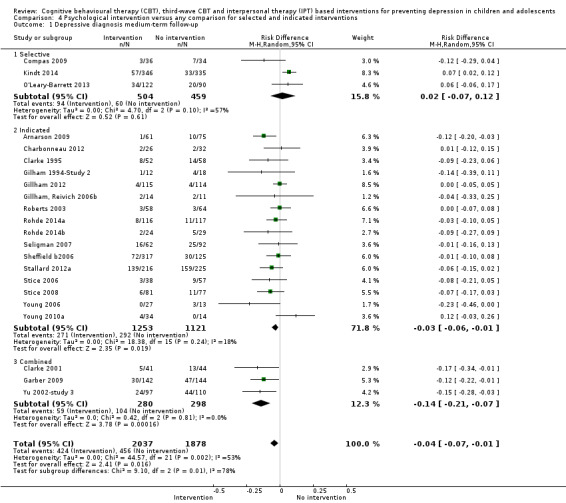

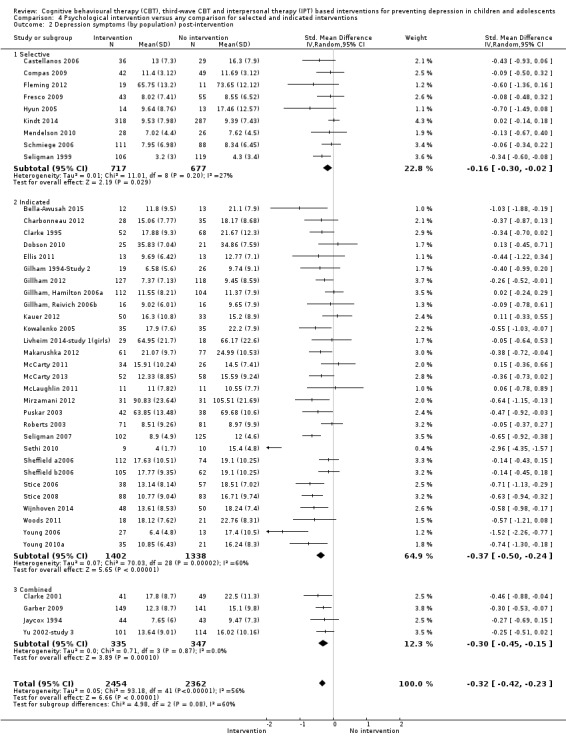

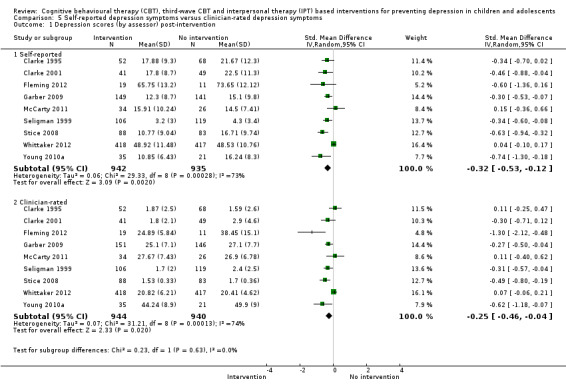

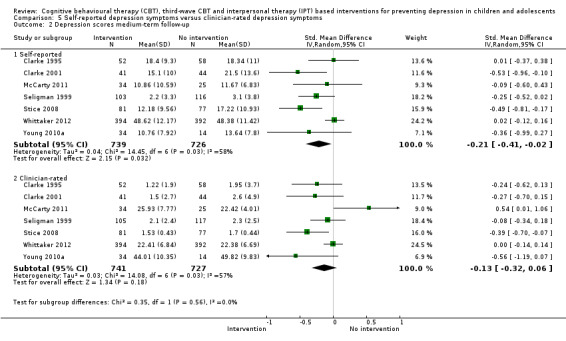

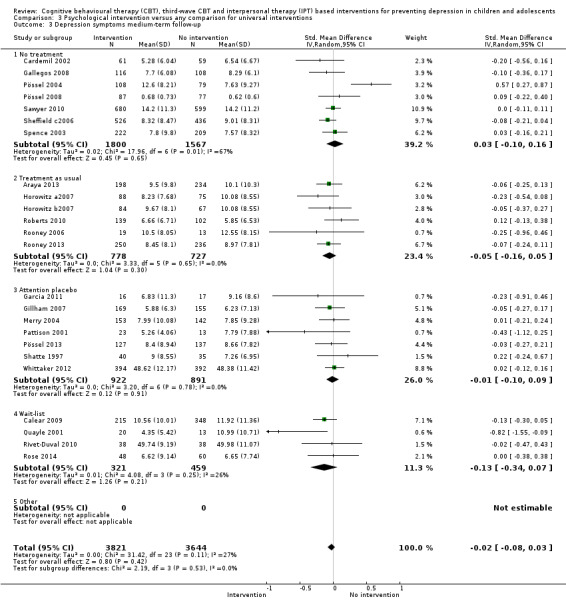

For the primary outcome of depression diagnosis at medium‐term follow‐up (up to 12 months), there were 32 trials with 5965 participants and the risk of having a diagnosis of depression was reduced for participants receiving an intervention compared to those receiving no intervention (risk difference (RD) ‐0.03, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.05 to ‐0.01; P value = 0.01). We rated this evidence as moderate quality according to the GRADE criteria. There were 70 trials (73 trial arms) with 13,829 participants that contributed to the analysis for the primary outcome of depression symptoms (self‐rated) at the post‐intervention time point, with results showing a small but statistically significant effect (standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐0.21, 95% CI ‐0.27 to ‐0.15; P value < 0.0001). This effect persisted to the short‐term assessment point (up to three months) (SMD ‐0.31, 95% CI ‐0.45 to ‐0.17; P value < 0.0001; 16 studies; 1558 participants) and medium‐term (4 to 12 months) assessment point (SMD ‐0.12, 95% CI ‐0.18 to ‐0.05; P value = 0.0002; 53 studies; 11,913 participants); however, the effect was no longer evident at the long‐term follow‐up. We rated this evidence as low to moderate quality according to the GRADE criteria.

The evidence from this review is unclear with regard to whether the type of population modified the overall effects; there was statistically significant moderation of the overall effect for depression symptoms (P value = 0.0002), but not for depressive disorder (P value = 0.08). For trials implemented in universal populations there was no effect for depression diagnosis (RD ‐0.01, 95% CI ‐0.03 to 0.01) and a small effect for depression symptoms (SMD ‐0.11, 95% CI ‐0.17 to ‐0.05). For trials implemented in targeted populations there was a statistically significantly beneficial effect of intervention (depression diagnosis RD ‐0.04, 95% CI ‐0.07 to ‐0.01; depression symptoms SMD ‐0.32, 95% CI ‐0.42 to ‐0.23). Of note were the lack of attention placebo‐controlled trials in targeted populations (none for depression diagnosis and four for depression symptoms). Among trials implemented in universal populations a number used an attention placebo comparison in which the intervention consistently showed no effect.

Authors' conclusions

Overall the results show small positive benefits of depression prevention, for both the primary outcomes of self‐rated depressive symptoms post‐intervention and depression diagnosis up to 12 months (but not beyond). Estimates of numbers needed to treat to benefit (NNTB = 11) compare well with other public health interventions. However, the evidence was of moderate to low quality using the GRADE framework and the results were heterogeneous. Prevention programmes delivered to universal populations showed a sobering lack of effect when compared with an attention placebo control. Interventions delivered to targeted populations, particularly those selected on the basis of depression symptoms, had larger effect sizes, but these seldom used an attention placebo comparison and there are practical difficulties inherent in the implementation of targeted programmes. We conclude that there is still not enough evidence to support the implementation of depression prevention programmes.

Future research should focus on current gaps in our knowledge. Given the relative lack of evidence for universal interventions compared with attention placebo controls and the poor results from well‐conducted effectiveness trials of universal interventions, in our opinion any future such trials should test a depression prevention programme in an indicated targeted population using a credible attention placebo comparison group. Depressive disorder as the primary outcome should be measured over the longer term, as well as clinician‐rated depression. Such a trial should consider scalability as well as the potential for the intervention to do harm.

Keywords: Adolescent; Child; Child, Preschool; Female; Humans; Male; Young Adult; Depression; Depression/diagnosis; Depression/prevention & control; Depressive Disorder; Depressive Disorder/diagnosis; Depressive Disorder/prevention & control; Program Evaluation; Psychotherapy; Psychotherapy/methods; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Evidence‐based psychological interventions for preventing depression in children and adolescents

The aim of this review was to assess the efficacy of evidence‐based psychological interventions designed to prevent the onset of a depressive disorder and to reduce any existing symptoms of depression.

Who may be interested in this review?

People involved in public health initiatives, school personnel and mental health clinicians.

Why is this review important?

Depressive disorder is common. It is associated with a negative impact on the functioning of young people and is expensive to society at large. Finding a way to prevent the onset of depressive disorder has the potential to make an important impact on the burden of depression in young people.

What questions does this review aim to answer?

Whether psychological depression prevention programmes designed to prevent the onset of depressive disorder in children and adolescents are effective.

Which trials were included in the review?

We included 83 studies (in particular randomised controlled trials) of evidence‐based psychotherapy interventions (cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and third wave CBT, interpersonal therapy) that had the specific aim of preventing the onset of depressive disorder. For the primary outcome of depression diagnosis at medium‐term follow‐up (up to 12 months), there were 32 trials with 5965 participants and for the primary outcome of depression symptoms (self‐rated) there were 73 trials with 13,829 participants.

What does the evidence from the review tell us?

We found that, compared with any comparison group, psychological depression prevention programmes have small positive benefits on depression prevention. There were some problems with the way the trials were done and in particular the results showed that compared to an attention placebo comparison group (a control intervention that controls for non‐specific factors like involvement in a trial and attention from researchers), these programmes had no effect. There is still not enough evidence to support the implementation of depression prevention programmes. However, based on the effects seen for targeted depression prevention programmes (albeit with inadequate control groups), we recommend that further research be undertaken to test the effectiveness of depression prevention programmes in populations of young people who already have some symptoms of depression. Such trials should compare the intervention to an attention placebo comparison group and measure whether depressive diagnosis is prevented in the long term. They also need to consider whether the approach is something that can be implemented in the real world. In addition, they should consider and measure whether the intervention produces harmful outcomes.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Evidence‐based psychological interventions versus any comparator for depression diagnosis at the medium‐term follow‐up.

| Evidence‐based psychological interventions compared to any comparator for depression diagnosis at the medium‐term follow‐up | |||||

| Patient or population: children and adolescents Settings: various Intervention: evidence‐based psychological interventions (targeted and universal) Comparison: any | |||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | ||||

| Any comparator | Evidence‐based psychological interventions | ||||

|

Evidence‐based psychological interventions versus any comparator (Overall) ‐ effect on diagnosis of depression The assumed risk is based on control group rates of depression diagnosis at medium‐term follow‐up (from a rank ordering of control group rates of each included study). |

Study population |

RR 0.84 (0.72 to 0.97) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 | — | |

| 193 per 1000 |

162 per 1000 (139 to 187) |

||||

| Low (0%) | |||||

|

0 per 1000 (0 to 0) |

|||||

| Moderate (18.5%) | |||||

| 185 per 1000 |

155 per 1000 (133 to 180) |

||||

| High (70.7%) | |||||

| 707 per 1000 |

594 per 1000 (509 to 685) |

||||

|

Evidence‐based psychological interventions versus any comparator (Targeted programmes) ‐ effect on diagnosis of depression The assumed risk is based on control group rates of depression diagnosis at medium‐term follow‐up (from a rank ordering of control group rates of each included study). |

Study population | RR 0.82 (0.68 to 0.99) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very low1,2,3 | — | |

| 243 per 1000 | 199 per 1000 (165 to 240) | ||||

| Low (0%) | |||||

|

0 per 1000 (0 to 0) |

|||||

| Moderate (20.4%) | |||||

| 204 per 1000 |

167 per 1000 (139 to 202) |

||||

| High (76.7%) | |||||

| 767 per 1000 |

629 per 1000 (521 to 759) |

||||

|

Evidence‐based psychological interventions versus any comparator (Universal programmes) ‐ effect on diagnosis of depression The assumed risk is based on control group rates of depression diagnosis at medium‐term follow‐up (from a rank ordering of control group rates of each included study). |

Study population | RR 0.87 (0.66 to 1.14) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate4 | — | |

| 99 per 1000 | 86 per 1000 (65 to 113) | ||||

| Low (1.0%) | |||||

| 10 per 1000 |

9 per 1000 (7 to 12) |

||||

| Moderate (14.5%) | |||||

| 144 per 1000 |

125 per 1000 (95 to 164) |

||||

| High (30.8%) | |||||

| 308 per 1000 |

268 per 1000 (203 to 351) |

||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | |||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | |||||

1We downgraded quality owing to lack of clarity over allocation concealment and presence of other bias. 2Heterogeneity (I2 = 53%). 3Omitting trials in which the outcome was measured indirectly (i.e. using cut‐points from self‐rated depression symptom inventories) caused the treatment effect for targeted depression prevention programmes to become non‐significant (RD ‐0.04, 95% CI ‐0.08 to 0.00; k = 15; n = 2783). 4We downgraded quality owing to a lack of clarity over random sequence generation and allocation concealment.

Summary of findings 2. Evidence‐based psychological interventions versus any comparator for self‐reported depression scores at the post‐intervention assessment.

| Evidence‐based psychological interventions versus any comparator for self‐rated depression scores at the post‐intervention assessment | ||||||

|

Patient or population: children and adolescents Settings: various Intervention: evidence‐based psychological interventions (targeted and universal) Comparison: any | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Any comparator | Evidence‐based psychological interventions | |||||

|

Evidence‐based psychological interventions versus any comparator (Overall) ‐ self‐rated depression scores (higher score is equivalent to a poorer outcome) |

The mean self‐reported depression score ranged across control groups from 0.66 to 105.51 points. | The mean self‐rated depression score in the intervention group was 0.21 standard deviations lower (0.27 to 0.15 lower) | — | 13,829 (73 trials) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low1,2 |

— |

|

Evidence‐based psychological interventions versus any comparator (Targeted ‐ self‐rated depression scores (higher score is equivalent to a poorer outcome)) |

The mean self‐reported depression score ranged across control groups from 4.30 to 105.51 points. | The mean self‐rated depression score in the intervention group was 0.32 standard deviations lower (0.42 to 0.23 lower) | — | 4816 (42 trials) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate3 |

— |

|

Evidence‐based psychological interventions versus any comparator (Universal programmes) ‐ self‐rated depression scores (higher score is equivalent to a poorer outcome) |

The mean self‐reported depression score ranged across control groups from 0.66 to 50.49 points. | The mean self‐rated depression score in the intervention group was 0.11 standard deviations lower (0.17 to 0.05 lower) | — | 9013 (31 trials) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate1 | — |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1We downgraded quality owing to a lack of clarity about random sequence generation and allocation concealment and the presence of other bias.

2Heterogeneity (I2 = 57%).

3We downgraded quality owing to a lack of clarity over allocation concealment and the presence of other bias.

Background

Description of the condition

Depression is a common problem in young people. Overall prevalence rates from a large meta‐analysis, measured from point prevalence up to 12‐month period prevalence, were estimated at 2.8% for children under the age of 13 and 5.6% for young people aged 13 to 18 years (Costello 2006). Rates rise steeply in adolescence (Fergusson 2001), with the peak period for the emergence of new cases of depression being during adolescence and young adulthood (Kessler 2005). By the age of 19, between a fifth and a quarter of young people have suffered from a depressive disorder (Lewinsohn 1993; Lewinsohn 1998). Depression in young people is associated with poor academic performance and vocational attainment and achievement, difficulties with interpersonal relationships, substance abuse, and attempted and completed suicide (Birmaher 1996; Birmaher 1996a; Brent 1986; Brent 2002; Fleming 1993; Gould 1998; Rao 1995; Rhode 1994). The Global Burden of Disease study, first published in 1997, ranked depressive disorder fourth in its estimate of disease burden, ahead of ischaemic heart disease, cerebrovascular disease and tuberculosis (Murray 1997). By 2002, depressive disorders ranked second in developed countries and first in developing countries with low mortality (Mathers 2004). Young people account for the greatest global burden of disease (Gore 2011). This means that reducing the incidence of depression has become a major focus, with a large number of trials of preventative interventions being published in the last three decades.

Description of the intervention

Prevention can be universal, where the intervention is implemented for a designated population regardless of risk, or targeted to a population at high risk for the disorder. Targeted interventions can be further classified into selective interventions that focus on populations with a risk factor for the disorder (e.g. family history) and indicated interventions that focus on populations with symptoms or signs suggestive of incipient disorder (Mrazek 1994). Early intervention may be considered prevention or treatment. The Institute of Medicine Report (Mrazek 1994), and the updated report (O'Connell 2009), recommend that prevention is defined as those interventions that occur prior to the onset of a clinically diagnosed disorder.

There are many psychological treatments for depression, which include psychodynamic, humanistic, integrative, systemic, behavioural and cognitive behavioural therapies (CBT) (including 'third wave' cognitive behavioural therapies). In a previous version of this review we had included both psychological interventions (broadly) and psychoeducational interventions; however, this review highlighted the fact that the vast majority of depression interventions developed thus far have been based on CBT and interpersonal therapy (IPT) (Callahan 2012; Merry 2011). The most robust evidence for the treatment of depression is for cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and interpersonal therapy (IPT) (which is an integrative therapy) (e.g. NICE 2005; McDermott 2011). They therefore represent a 'good best bet' in terms of depression prevention.

Depression prevention interventions are often delivered to a group within a school setting. This is because young people spend a significant amount of time at school so disseminating a programme within a school or classroom, and to groups of young people is likely to be cost‐effective. Delivery to a group may also reinforce efficacy by providing positive peer experiences. Both group and individual interventions usually take place on a weekly basis with 8 to 12 sessions delivered (Merry 2011).

How the intervention might work

The aetiology of depressive disorder is complex and includes biological, psychological and social factors (Cicchetti 1998; Davidson 2002; Goodyer 2000; Lewinsohn 1994; McCauley 2001). There are clear theories regarding the individual factors that create a predisposition to developing depression, which may alternatively provide a model for promoting resilience in the face of stress. These underlie the currently available evidence‐based interventions for depression. These theories provide a basis for the development of prevention programmes and an understanding of the mechanisms by which they achieve a reduction in the rates of the onset of depression.

Beck developed cognitive behavioural therapy based on his cognitive model of depression (Beck 1976). He proposed that individuals prone to depression have cognitive distortions that result in a negative view of themselves, the world and the future. In CBT, people learn to identify, explore and modify relationships between negative thinking, behaviour and depressed mood. This is achieved by learning to identify and monitor the intensity of different moods in themselves, recognising thoughts and behaviours that have contributed to this mood, and learning how to address these by evaluating and challenging unhelpful thoughts and engaging in behaviour that contributes to improved mood. The associated concepts of 'attributional style' (Abramson 1978) and 'learned helplessness' (Petersen 1993; Seligman 1979) have also contributed to components of CBT. Those with a pessimistic attributional style see negative events as a stable and enduring part of themselves, while positive events are seen as transient occurrences in which they have played no part. Learned helplessness is a phenomenon of withdrawal with depression the result of a perceived failure or inability to control aversive events. Both are associated with a sense of helplessness and hopelessness, which leads to passivity in the face of challenges and contributes to low mood (McCauley 2001). People who are prone to depression are then less likely to take an active approach to dealing with difficulties. CBT also tends to include a component of effective problem‐solving.

Interpersonal conflict, difficulty with role transitions and experiences of loss are all well known as risk factors in the development of depressive disorder in young people (Birmaher 1996; Lewinsohn 1994; Lipsitz 2013; McCauley 2001). IPT helps a person resolve interpersonal problems through a range of techniques and thereby increases a person's access to social support and decreases interpersonal stress, which improves emotional processing and interpersonal skills and ultimately improves symptoms via a range of mechanisms. There are a number of specific techniques that can be used, such as helping the client to express and explore different emotions within social situations, encouraging them to develop supportive relationships with others outside of the therapeutic context, and using role play to allow the client to 'test out' and improve on their communication style (Lipsitz 2013).

While evidence is yet to be clearly established in young people, 'third wave CBT' approaches are becoming popular. These approaches are characterised (in comparison with CBT) by techniques that target the process, rather than content of thoughts, helping people to become aware of and accept their thoughts in a non‐judgemental way (Hofmann 2010). They include such interventions as acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) (Hayes 2003), mindfulness‐based cognitive therapy (MBCT) (Teasdale 1995), dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) (Linehan 1993), and the expanded model of behavioural activation (BA) (Martell 2001).

Why it is important to do this review

Since the previous update of the review was published in 2011 (Merry 2011), there have been a large number of trials of preventive interventions for depression in children and adolescents. Between publication of the original review in 2004 (Merry 2004b) and the publication of the update in 2011, the findings changed slightly from showing that targeted programmes were potentially effective in preventing depression for young people, with more mixed results from universal programmes, to supporting both targeted and universal depression prevention programmes as having the potential to prevent depression. With so many new trials published, it is possible that the results could change. It is also the case that many of the most promising approaches to depression prevention have been difficult to replicate in large‐scale pragmatic efficacy trials (e.g. Araya 2013; Stallard 2012). Governments are keen to take action to address the burden of depression on society, and its relationship to suicide attempts and completed suicide. It is critical that depression prevention programmes that are implemented are based on the evidence and represent the best possible approach of all those that have been tested to data for maximum benefit. It is timely to re‐evaluate the evidence currently available for the efficacy of depression prevention programmes as well as to explore how different therapeutic approaches may modify overall prevention effects. This version of the review therefore includes a more homogeneous group of trials by excluding trials of psychoeducational interventions, interventions delivered to those who have suffered trauma and interventions that are primarily aimed at preventing anxiety. It is important that this review, with more limited inclusion criteria, is undertaken in order to help direct governments to the most promising approach to depression prevention.

Objectives

To determine whether evidence‐based psychological interventions (including cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy (IPT) and third wave CBT)) are effective in preventing the onset of depressive disorders in children and adolescents.

We included:

universal interventions; and

targeted interventions aimed at young people at risk of developing a depressive disorder. Within these targeted intervention trials we investigated the impact of the type of targeted approach (indicated versus selected) on the overall treatment effect of targeted interventions.

We also separately investigated the impact of the type of control group on the overall treatment effect within the targeted and universal trials.

Finally, we undertook exploratory analyses, using meta‐regression, to further investigate whether the type and intensity or other components of the intervention or baseline severity of depression impacted on the overall treatment effect.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), including cluster‐RCTs. We also considered cross‐over designs eligible for inclusion. (They will be eligible in future updates, but none were located for this update).

Types of participants

Participant characteristics

We included trials if participants were children and adolescents whose mean aged fell within the range of 5.0 to 19.9 years There were no restrictions on gender or ethnicity.

Diagnosis

We included studies if participants did not currently meet the criteria for a clinical diagnosis of depressive disorder.

There were three ways of selecting participants for trial inclusion that were eligible for this review:

trials that recruited an unselected population of participants regardless of their level of depressive symptoms (i.e. 'universal' programmes);

trials that recruited participants on the basis of a specific risk factor for depression, such as the death of a parent, parental conflict or a family history of depression (i.e. 'selected' programmes);

trials in which participants had elevated levels of depressive symptoms according to scores on standardised, validated scales of depression (i.e. 'indicated' programmes).

We included studies that included participants with a history of a depression if the intervention was aimed at the prevention of depression in a non‐clinical setting, and where the participants were not being currently treated for depression. Although this is not a purist definition of prevention, in fact the majority of included trials did not rigorously assess whether or not participants had a history of depressive disorder while some of the best designed included trials that we identified did do this. It was illogical to exclude those trials that did assess whether or not participants had a history of depressive disorder, given that the participants in the other trials were likely to have also included young people with past episodes of depressive disorder that had been unrecognised and untreated.

We excluded studies if they lacked a clear definition of participants, included children and adolescents who met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) IV (DSM‐IV‐TR) (American Psychiatric Association 2000) or International Classification of Diseases(ICD‐10) (World Health Organization 2007) criteria for depressive disorder, were clearly designed to be treatment trials or where there was no adequate assessment of participants.

Co‐morbidities

We excluded trials in which participants were recruited primarily with respect to other psychological problems (e.g. post‐traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, substance use, insomnia) or physical illnesses (e.g. diabetes or HIV) but where depression was a potential comorbid issue and was therefore measured as a secondary outcome measure.

Setting

We included trials regardless of the setting within which the intervention took place (e.g. school, primary care setting).

Types of interventions

Experimental intervention

As recommended in the Institute of Medicine Report (Mrazek 1994; O'Connell 2009), we classified prevention as those interventions that occurred prior to the onset of a clinically diagnosable disorder and this could include interventions for individuals with elevated symptoms of disorder but who did not currently meet the criteria for a clinical disorder.

In a previous version of this review, we included both psychological and educational interventions. However, in this version of the review we have only included evidence‐based psychological interventions. CBT and IPT have been established as efficacious in treatment and most prevention researchers have built on this in prevention. Indeed, the majority of trials included in the previous version were CBT‐based and restricting inclusion as we have done in this version ensures greater homogeneity, therefore enabling us to explore the impact of different approaches within these broad categories on the overall treatment effect. Therefore, we only included trials investigating the efficacy of CBT‐oriented (including problem‐solving interventions (PST) and third wave CBT) or IPT‐oriented (or combination) or other similar approaches in the review.

We had an inclusive approach to these included therapies so that, for example, an intervention might only include one of a range of the CBT techniques in isolation (e.g. only cognitive restructuring, or only monitoring mood in relation to activities), but was still included as being CBT‐based. Problem‐solving techniques are often included in CBT interventions, but can also be delivered in isolation, for example problem‐solving therapy (PST). Third wave therapies included mindfulness, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT), positive psychology and any purely behavioural approaches.

The number of sessions delivered and the way interventions were delivered could vary. In most cases, interventions were delivered in groups, but given the increasing use of new media to deliver interventions these modes of delivery as well as traditional face‐to‐face individual and group‐based interventions are included. Trials had to implement the majority of an intervention primarily to the child/adolescent themselves, either in individual or group‐based sessions. We therefore excluded trials that delivered an intervention for parents with the aim of impacting on parenting practices and, subsequently, depressive symptoms in their child, without any sessions delivered to the child themselves.

We excluded interventions targeted at helping children to manage the consequences of a specific event or situation (e.g. divorce). However, we included trials in cases where the intervention was sufficiently broad and participants were taught skills that could be applied to a wide variety of problematic situations.

We excluded secondary and tertiary interventions, including relapse prevention and pharmacological interventions for depression.

Comparator intervention

The comparison groups that were eligible for inclusion in this review, in order of increasing rigorousness, were:

treatment as usual (TAU), defined as the normal healthcare curriculum, physical education classes or the ability to access any school‐based and/or external mental health care as required;

no treatment (NT);

wait‐list (WL);

attention placebo (AP), defined by Merry 2006 (p.178) as “controlling for non‐specific factors….which we would not expect to affect factors specifically implicated in the aetiology of depression.” These non‐specific factors could include participating in a trial with a prescribed curriculum and materials and having time off regular classes. Attention placebo may include psychoeducation about general mental and/or physical health, however, the programmes would not target mood specifically. We rated the ‘credibility’ of the AP (i.e. how well‐matched it is to the intervention and how well it would control for likely non‐specific factors of the intervention); and

other, which may include brief psychoeducation and/or information and support but does not include another psychological intervention.

We excluded head‐to‐head trials where CBT, IPT or third wave CBT was only compared to another type of psychological intervention as our primary aim was to examine the efficacy of these interventions in preventing depression.

Types of outcome measures

In the first update of the review, Merry 2011, we excluded general adjustment, academic/work function, social adjustment, cognitive style and suicidal ideation/attempts outcomes given the paucity of data that existed for these outcomes in the first version of the review (Merry 2004b). In this version of the review we have included clinician‐rated depression symptoms because, while the majority of trials use self‐rated measures, a good minority of trials also use a clinician‐rated measure and it is important to assess the impact on depression according to different raters. We have been able to reinstate an outcome related to our early functioning outcomes, but have only included general functioning, again due to the paucity of outcomes for more specific categories of functioning. We have also now included anxiety because of the high co‐morbidity between depression and anxiety.

Primary outcomes

Our primary outcomes were:

Prevalence of depression diagnosis at medium‐term follow‐up (i.e. between four and 12 months), measured using a recognised diagnostic system such as DSM‐IV‐TR (American Psychiatric Association 2000) or ICD‐10 (World Health Organization 2007), or tools that yield diagnoses of depressive disorder according to these systems (e.g. the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders Scale (K‐SADS; Kaufman 1997)) or, where this was not available, using a predesignated cut‐off point on a continuous measure of depression symptoms likely to be correlated with the presence of a depressive disorder therefore indicating 'caseness' (e.g. the Children's Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs 1992).

Depression symptoms at the post‐intervention assessment point assessed using a standardised, validated self‐report measure of depression symptoms (e.g. CDI; Kovacs 1992).

Our primary outcome of depression symptoms at post‐intervention and medium‐term depression diagnosis was based on the literature that shows that subsyndromal depressive symptoms are predictive of the onset of major depressive disorder (Cuijpers 2004).

Where more than one outcome measure was used, we entered the highest quality outcome measure into the analyses. For this we used a hierarchy based on psychometric properties and appropriateness for use with children and adolescents, following the method described by Hazell 2002 (see Appendix 1).

Secondary outcomes

Our secondary outcomes were:

Depression diagnosis and depression symptoms (self rated) at other time points (see 'Timing of outcome assessment' below).

Depression symptoms (clinician‐rated)using a standardised validated measure (e.g. Children's Depression Rating Scale‐Revised; Poznanski 1996).

Anxiety symptoms at post‐intervention and follow‐up, measured using a standardised, validated measure of anxiety symptoms (e.g. the Revised Children's Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS; Reynolds 1985), the Spence Anxiety Scale (SCAS; Spence 2003), the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck 1988), the State Anxiety Inventory for Children (SAIC; Spielberger 1970) or the Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS; Chorpita 2005)).

General and social functioning at post‐intervention and follow‐up, measured using a standardised, validated measure of general or social functioning (e.g. Children's Global Assessment Scale (CGAS; Shaffer 1983), the Child and Adolescent Social and Adaptive Functioning Scale (CASAFS; Price 2002), the Paediatric Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (PQ‐LES‐Q; Endicott 2006), or the Social Adjustment Scale‐Self‐Report for Youth (SAS‐SR‐Y; Weissman 1980)).

The above is not intended to represent an exhaustive list of validated psychometric scales for the assessment of anxiety or functioning. Instead, these are the scales that we, as review authors, would expect to encounter as outcome measures in this particular field of research.

Timing of outcome assessment

We analysed all outcomes at four time points:

post‐intervention;

short‐term follow‐up (up to three months);

medium‐term follow‐up (four to 12 months); and

long‐term follow‐up (over 12 months).

If there was more than one follow‐up within a specified time frame we used the data for the longest follow‐up point within that time frame, except for long‐term follow‐up, where we only used data measured up to 36 months (three years) to ensure some consistency.

Hierarchy of outcome measures

Where more than one outcome measure was used, we entered the highest quality outcome measure into the analyses. For this we used a hierarchy based on psychometric properties and appropriateness for use with children and adolescents, following the method described by Hazell 2002.

The hierarchy of measurement tools for each is as follows:

Clinician‐based assessments

Children's Depression Rating Scale (CDRS)

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM‐D)

Montgomery‐Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)

Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Aged Children (K‐SADS)

Bellevue Index of Depression (BID)

Self‐report measures:

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)

Children's Depression Inventory (CDI)

Mood and Feeling Questionnaire (MFQ)

Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale (RADS)

Kutcher Adolescent Depression Scale (KADS)

Depressive Adjective Checklist (DACL)

Child Depression Scale (CDS)

Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD)

Search methods for identification of studies

The Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group maintains a specialised register of randomized controlled trials, the CCMDCTR. This register contains over 40,000 reference records (reports of RCTs) for anxiety disorders, depression, bipolar disorder, eating disorders, self‐harm and other mental disorders within the scope of this Group. The CCMDCTR is a partially studies based register with >50% of reference records tagged to c12,500 individually PICO coded study records. Reports of trials for inclusion in the register are collated from (weekly) generic searches of Medline (1950‐), Embase (1974‐) and PsycINFO (1967‐), quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and review specific searches of additional databases. Reports of trials are also sourced from international trial registries, drug companies, the hand‐searching of key journals, conference proceedings and other (non‐Cochrane) systematic reviews and meta‐analyses. Details of CCMD's core search strategies (used to identify RCTs) can be found on the Group's website with an example of the core Medline search displayed in Appendix 2.

Electronic searches

1. Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Group's Specialised Register (CCMDCTR)

The Group's Information Specialist cross‐searched the CCMDCTR‐Refs and CCMDCTR‐Studies registers (11 September 2015) using the following updated search strategy:

#1. (prevent* NEAR2 (depress* or "mental health")):ti,ab,kw,ky,emt,mh,mc #2. ((stress or trauma or disaster*) and depress* and symptom*):ti,ab #3. ((psycholog* or problem* or symptom or symptoms) NEAR1 (adjust* or adaptat* or externali* or internali*)):ti,ab,kw,ky,emt,mh,mc #4. (depression or depressive or dysthymi* or “depressed mood” or “low mood*” or “mood *regulation” or “mood disorder*” or “mental health”):ti,ab,kw,ky,emt,mh,mc #5. ((prevent* or primary or targeted or universal* or selective or selected or indicated) NEAR2 (intervention* or program*)):ti,ab,kw,ky,emt,mh,mc #6. ("early intervention*" or risk or at‐risk or vulnerab* or (health NEAR3 promot*) or "health literacy" or educat* or psychoeducat* or training or "life skill*" or *school* or classroom* or campus or internet* or online or divorce* or death or bereave* or bullied or bully*):ti,ab,kw,ky,emt,mh,mc #7. (adolesc* or preadolesc* or pre‐adolesc* or child* or boys or girls or juvenil* or minors or pre‐school or preschool or paediatric* or pediatric* or pubescen* or puberty or *school* or campus or teen* or (young next (adult* or people or patient* or men* or women* or mother* or male or female or survivor* or offender* or minorit*)) or youth* or (student* and (college or universit*)) or undergraduate* or peer or peers):ti,ab #8. ((#1 or #2) and #7) #9. (((#3 OR #4) AND (#5 OR #6)) AND #7) #10. (#8 or #9)

Key to CRS search tags: ti:title; ab:abstract; kw:keywords; emt:EMTREE headings; mc:MeSH checkwords; mh:MeSH Headings

Earlier update searches (conducted in June 2010 and July 2013) when the register was called the CCDANCTR (reflecting the Group's earlier name of the Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group) can be found in Appendix 3.

2. International trial registries

We searched international trial registries via the World Health Organization's trials portal (ICTRP) and ClinicalTrials.gov to identify unpublished or ongoing studies (to 11 September 2015).

3. Additional electronic database searches

The original version of this review (Merry 2004b) also incorporated additional searches of MEDLINE (to Dec 2002), EMBASE (to January 2003), PsycINFO (to January 2003) and ERIC to (Dec 2002). The original search terms for all databases were updated (16 September 2009) (see Appendix 4; Appendix 5; Appendix 6; Appendix 7) and searches of these four databases were re‐run at this time.

All bibliographic database searches post‐2009, however, were conducted in the CCDAN/CCMD‐CTR only as this database is regularly updated with reports of relevant randomized trials from CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE and PsycINFO.

This review was first updated and re‐published in December 2011 (Merry 2011).

Searching other resources

The reference lists of articles and other reviews retrieved in the search were searched;

For this update of the search, conference abstracts from all relevant conferences in the field of depression prevention in children and adolescents were handsearched. For previous updates of this review, we specifically handsearched conference abstracts, 1994, 1996 and 1998‐2001, for the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry;

Authors of the included trials were also consulted to find out if they knew of any published or unpublished RCTs in the area, which had not yet been identified.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

At least two of the review authors independently performed the selection of trials for inclusion in this update of the review. Where a title or abstract appeared to describe a trial eligible for inclusion, we obtained the full article and two authors independently inspected it to assess its relevance to this review based on the inclusion criteria outlined in the Criteria for considering studies for this review section. A third review author resolved any discrepancies between the two authors.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (two of either SH, GC or KW) and one research assistant (one of either AS, KL or AH) independently extracted data. A third review author (SH, GC or SM) resolved discrepancies. To ensure accurate data entry, we double‐checked the data after entry for analysis. We extracted the following details from the included trials and the information is presented in the Characteristics of included studies section:

Methods

Study design (i.e. RCT or cluster‐RCT).

If the intervention was conducted by the team who developed it.

Characteristics of the trial participants

Focus of intervention (i.e. universal or targeted).

If there was a cut‐point (and what this was; for indicated prevention trials) used on a validated depression measurement scale to include participants.

What aspect of risk (for selected prevention trials) was the basis for inclusion into a trial.

Whether a diagnostic interview was used to exclude participants with a current or previous depressive episode, and the % of participants included who had experienced a previous episode.

Baseline severity of depression.

Age and sex of participants.

Location of intervention programmes, e.g. school or community.

What psychiatric diagnoses were excluded.

Whether participants were at risk of suicide.

Whether parents with a history of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder were excluded.

Interventions used

Description of intervention including intervention type (e.g. CBT, IPT, CBT + IPT, PST, third wave), focus of CBT (i.e. included both cognitive and behavioural techniques, or was focused mainly on cognitive techniques, or was focused mainly on behavioural techniques; and the specific types of key techniques that were included), the components of the intervention (e.g. cognitive restructuring, behavioural techniques, problem‐solving, social skills training, relaxation techniques, third wave techniques, anxiety management techniques, component/s focusing on management of specific problems, whether there were parent sessions) whether it was manualised, if it was online.

The number and length of sessions (delivered), intended intensity (intended total time in hours), treatment duration, size of group (where group‐based), who delivered the intervention and assessment of fidelity.

Type of comparison condition (e.g. treatment as usual, wait‐list, attention placebo).

We coded interventions as containing cognitive restructuring if they mentioned participants identifying and learning about thinking errors/dysfunctional thoughts or the impact of negative emotional states on thoughts, and as containing behavioural techniques if they included any technique that aimed to activate people, encouragement to engage in pleasant events or activities, activity monitoring and/or scheduling, monitoring mood in relation to activities, bringing to mind pleasant activities and distraction techniques. Interventions that we coded as containing elements of problem‐solving described teaching participants ways in which to identify problems, generate potential solutions and evaluate solutions. We classed an intervention as containing social skills training if it reported teaching participants assertiveness, negotiation strategies or positive ways in which to respond in social settings that were culturally appropriate. We coded interventions as containing relaxation techniques if they mentioned employing 'relaxation' strategies or training, and we coded them as containing third wave techniques if they reported teaching mindfulness, yoga, meditation and/or distancing techniques.

Outcomes

The tool and method used to establish depression diagnosis.

The tool and method used to measure depression symptoms.

The tool and method used for anxiety symptoms.

The tool and method used for general and/or social functioning.

Assessment time points.

When aspects of methodology were unclear, or when the data were in a form unsuitable for meta‐analysis and trials appeared to meet the eligibility criteria, we sought additional information from the corresponding author. We also sought the treatment manual or, if this was not available, details of the components of the intervention that were delivered as part of the intervention from every corresponding author. We have indicated in the notes section of the Characteristics of included studies table if an author supplied additional data.

Main comparison

We planned one main comparison (i.e. any evidence‐based psychological intervention compared with any comparator). Within this we subgrouped by the type of population (i.e. universal versus targeted).

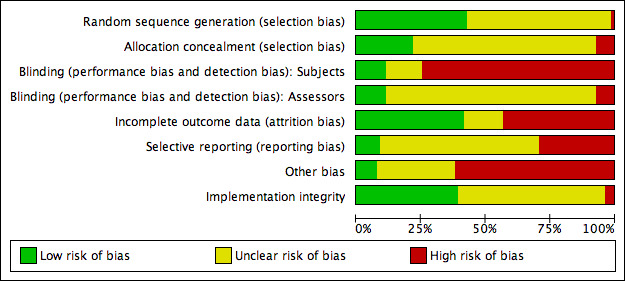

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

For the original version of this review, two independent authors assessed methodological quality using the quality rating scale devised by Moncrieff and colleagues (Moncrieff 2006); those trials scoring 30 or more were deemed 'high' quality, those scoring 23 or more were deemed 'adequate' with sensitivity analysis undertaken on this basis.

For the current version of the review, we updated our methods to conform to the current version of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Specifically, we examined each trial for random sequence generation method, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and assessors, the methods of addressing incomplete outcome data and potential selective reporting. For the domain of 'other potential sources of bias' we assessed the independence of the investigators (were the investigators independent of those who developed the intervention) and implementation integrity (were sessions taped and rated, was the integrity reported and was it adequate).

Two review authors (two of either SH, JB or KW) independently performed all assessments of the risk of bias. A third author (GC) resolved any discrepancies.

A description of the assessment of risk of bias is provided in the 'Risk of bias' tables in the Characteristics of included studies section.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

We pooled dichotomous data using the risk difference (RD) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). We have used the risk difference as we consider that this is the most relevant measure for this analysis. Our primary question is whether the onset of an episode of a depressive disorder is lower following an intervention. If an intervention is successful, the absolute number of participants with a diagnosis of depressive disorder following the intervention will be lower than those with a diagnosis of a depressive disorder in the control group. The risk difference is easy to interpret and can be converted to number needed to treat to benefit (NNTB), which is meaningful when considering whether or not depression prevention is likely to be an effective public health intervention. We made an a priori decision to include the NNTB for the primary outcome of depression diagnosis at medium‐term follow‐up as a way of interpreting the results for the reader.

Continuous data

For continuous outcomes, we pooled the means and standard deviations using the standardised mean difference with a 95% CI.

Typically SMD effect sizes of 0.20 are considered small, 0.50 are considered medium and 0.80 are considered large (Pace 2011); however, given that most SMDs reported in meta‐analyses conducted in the social sciences range between ‐0.08 and 1.08 (Lipsey 1993), and in the prevention science field effects sizes are smaller, we made the decision prior to commencing work on this version of the review to consider effect sizes of 0.20 or less as small, effect sizes that approached 0.30 as medium; and effect sizes that approached 0.50 as large.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

For all cluster‐randomised trials we adjusted for the effects of clustering following the procedure outlined in Higgins 2008b, section 16.3.4. Where information on the interclass correlation (ICC) was not reported within the text of a trial, we contacted trial authors to request this information. Where we were unable to obtain this information from the trial authors, we used an ICC estimate of 0.0282, as this represents the average of the ICCs obtained from the other trials included in the analysis. Where a trial/s presented a range of ICC or design effect values, and where it was unclear which value applied to a given outcome or time point, we used the higher value in order to calculate the most conservative sample size.

Multi‐arm trials

Where a trial/s had more than one evidence‐based intervention arm compared with a single control group, we chose the intervention arm that was the most active. Where there was more than one eligible intervention within a class (i.e. CBT, IPT), we chose the most intense in terms of the intervention that had the most intervention components or was longer, or both.

Where a trial/s included multiple comparator arms, we extracted data from the most rigorous control group to ensure the estimated treatment effect was not inflated, following the hierarchy of comparator rigorousness outlined in the Types of interventions section.

As the previous version of this review found that the magnitude of effect for depression prevention programmes is similar between boys and girls, we have combined data by gender where a trial/s presented data separately for boys and girls. Additionally, as other work has found no evidence of moderation by ethnicity (Marchand 2010), we have also combined data where a trial/s presented data separately for members of different ethnicity. Further, our interest was in examining factors related to the type of intervention and methods that might impact on the overall treatment effects (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity section).

Dealing with missing data

It is common for authors to report using intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analyses to account for missing data, although it is generally the case that the data presented and extracted for the meta‐analysis were raw data. Where it is not clear whether an ITT analysis was undertaken, or where data were reported based on adjusted means (or it was unclear), we contacted trial authors to obtain the raw mean and standard deviations (SDs) based on available information. In most cases, therefore, data extracted and used within meta‐analyses are based on observed case data. Where adjusted means have been used, we undertook sensitivity analyses (see Sensitivity analysis section).

Where data on the primary outcomes reported in this review were missing, we requested these from the trial authors by letter or email, or both. We have noted in the Characteristics of included studies section whether these data were supplied. In some cases we sought secondary outcome data where available.

Where SDs for continuous outcomes were not reported and we as review authors were unable to obtain the information from corresponding authors, we imputed a pooled SD using the method outlined in Townsend 2001.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity visually by inspecting the forest plots and identifying those trials with 95% CIs outside the general pattern of the others and, more formally, by checking the results of the I2 statistic. We took into account: (i) the magnitude and direction of effects, and (ii) the strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. the width of the 95% CI for the I2).

We used the following guide as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions to the interpretation of the I2 statistic (Higgins 2008a; Higgins 2008b):

0% to 40%: heterogeneity might not be important;

30% to 60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity*;

50% to 90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity*;

75% to 100%: considerable heterogeneity.

Should any meta‐analysis be associated with substantial or considerable heterogeneity (i.e. I2 ≥ 75%), we triple‐checked the data to ensure these had been entered correctly.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed trial reports, and protocols where available, to assess whether trial authors reported all prespecified outcome(s).

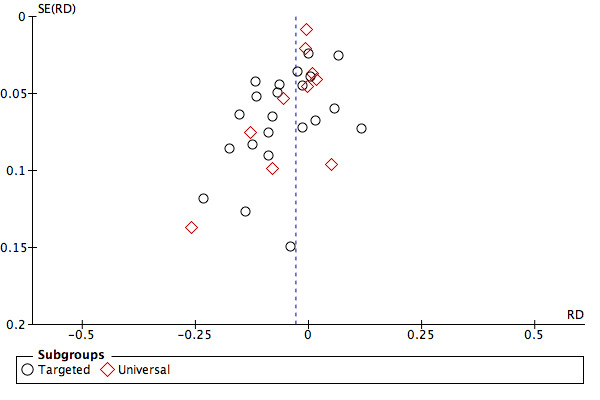

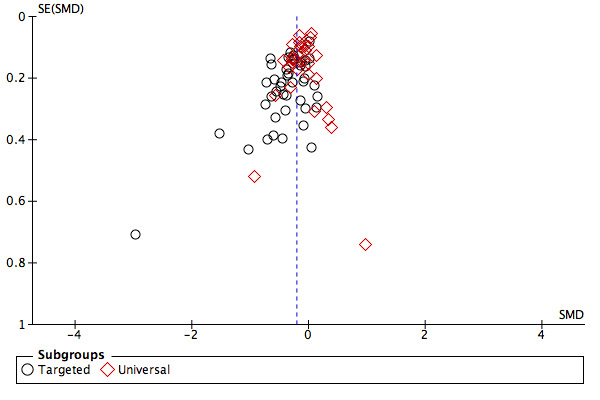

We assessed publication bias by inspecting funnel plots for the primary outcomes of the review where there were more than 10 trials included in the analysis as recommended.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analyses in accordance with the guidelines in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions(Higgins 2008a; Higgins 2008b). We used the random‐effects model with 95% CIs to pool data. Specifically, for dichotomous outcomes we used the Mantel‐Haenszel method whilst, for continuous outcomes, we used the inverted variance method.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analyses

We analysed trials separately based on one main prespecified subgroup: universal versus targeted interventions.

For the primary outcome measures of self‐rated depression scores at post‐intervention and depression diagnosis at medium‐term follow‐up, we also undertook an additional subgroup analysis to investigate whether the type of control group modified the pooled effect size. For the group of trials that we classified as targeted interventions, we undertook a further subgroup analysis for selected versus indicated versus combined approaches.

Meta‐regression analyses

For the primary outcome measures of depression diagnosis at the medium‐term assessment and self‐reported depression scores at the post‐intervention assessment, we undertook a series of random‐effects univariate meta‐regression models to examine whether the type and aspects of the intervention approach and population characteristics (severity of baseline depression) modified the pooled effect size of universal and targeted interventions separately as follows:

baseline depression severity (subthreshold; mild; moderate; severe);

intended intervention intensity (number of hours);

type of therapist (mental health expert; non‐mental health expert; student);

broad intervention focus (CBT; IPT; CBT plus IPT; third wave)

CBT focus (CBT with an equal emphasis on cognitive and behavioural components; CBT with a cognitive focus; CBT with a behavioural focus);

inclusion of a relaxation component (for CBT interventions only);

inclusion of a problem‐solving skills component (for CBT interventions only);

inclusion of a social skills training component (for CBT interventions only);

method of delivery (face‐to‐face (group and individual) versus online/telephone).

We performed the random‐effects meta‐regression analyses in Comprehensive Meta‐Analysis for Windows, version 3.2.1 (Biostat 2014).

Sensitivity analysis

For the primary outcomes reported in this review, we also checked the robustness of the results by conducting the following sensitivity analyses:

use of adjusted, rather than raw, mean scores (for outcomes measured on a continuous scale only);

adequacy of allocation concealment (high and unclear risk versus low risk);

inclusion of participants with a previous depression;

use of a cut‐point to establish depressive disorder.

'Summary of findings' tables

We prepared 'Summary of findings' tables for the primary outcome measures of depression diagnosis at the medium‐term follow‐up and self‐rated depression scores at the post‐intervention assessment following the recommendations outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, section 11.5 (Higgins 2008b), Guyatt 2013a (for dichotomous outcomes) and Guyatt 2013b (for continuous outcomes). For both outcomes we based our estimates of risk on a range of control group rates at medium‐term follow‐up. To do this we extracted the proportion diagnosed for each included trial and rank ordered them from the lowest to the highest proportion, then took the lowest, the median and the highest proportion to determine the risk categories (lowest, median, highest). We prepared 'Summary of findings' tables using GRADE profiler for Windows, version 3.6.1 (GRADE profiler).

Two review authors (GC and KW) independently appraised the quality of evidence following the recommendations in section 12.2 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions(Higgins 2008b).

Timeline

We will carry out a new search for RCTs and update the review when it is likely that new trials have been published that may change the conclusions of the review.

Results

Description of studies

For a full description of each trial, see the Characteristics of included studies section.

Results of the search

2011 version of this review

Sixty‐eight trials (from 66 publications) were included in the 2011 version of this review. For the 2015 update, we combined the data referenced in the 2011 update as Cardemil 2002a and Cardemil 2002b (now Cardemil 2002) and Clarke 1993a and 1993 (now Clarke 1993). We received further information with regards to the randomisation procedure used in two previously excluded trials (Jaycox 1994; Kowalenko 2005), and one trial previously classified as awaiting assessment (Gallegos 2008). In all cases the authors confirmed that they did randomise schools or individuals (or both) to intervention and control group. As a result, these three trials have now been included in the current review.

As the inclusion criteria for this update were changed to ensure a more homogeneous group of trials specifically targeting the prevention of depression, we have now excluded 26 previously included trials. Please see the Excluded studies section for more details on this.

In total, we included 43 independent trials from the 2011 version of the review in this update.

Results of the search for the 2015 update of the review

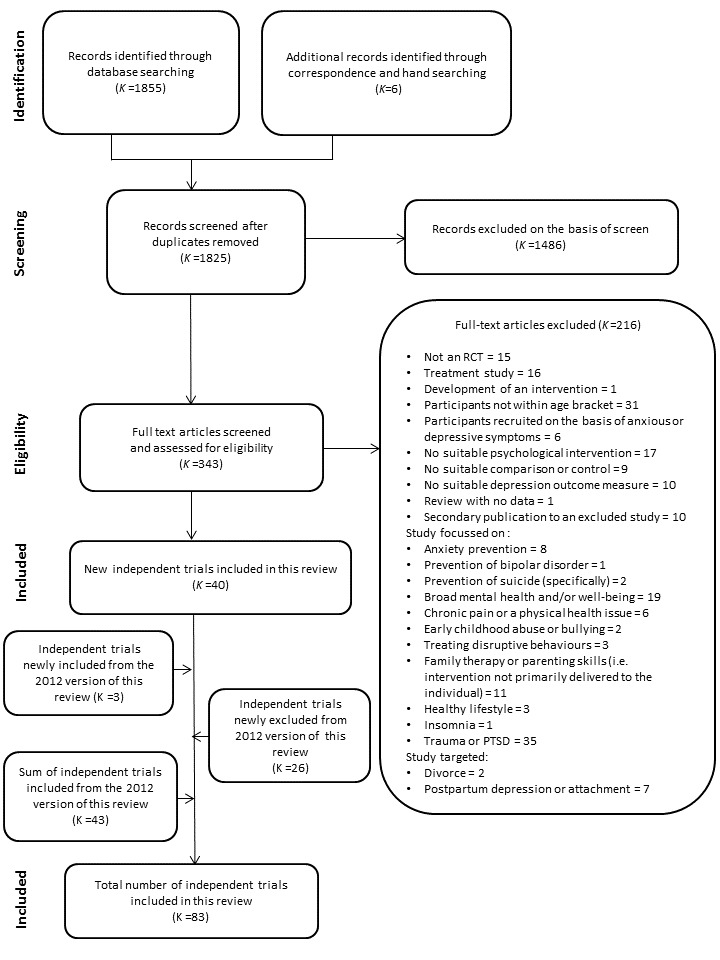

In total there were 1855 articles retrieved from the updated searches (from June 2010 to September 2015), with 1825 remaining after de‐duplication. We obtained six further articles either by correspondence with trial authors or from handsearching key references. Two review authors (SH, GC) read the titles and abstracts of all those articles retrieved and a third author (SM) resolved discrepancies. In total, we excluded 1486 articles on this basis with 343 retained for inspection of the full article text for eligibility. We excluded a total of 216 studies; only studies that one would expect to be included in the review but did not quite meet the inclusion criteria have been included in the Excluded studies section. A total of 40 trials were eligible for inclusion from this search in the update of this review.

In total, we included 83 independent trials in this update of the review (Figure 1). However, when describing the characteristics of these trials in the Description of studies section below, the total numbers often exceed 83 as some trials contained multiple intervention arms (Horowitz a2007; Horowitz b2007; Sheffield a2006; Sheffield b2006; Sheffield c2006).

1.

PRISMA diagram

Included studies

Eighty‐three trials were eligible for inclusion. We obtained data suitable for pooling for meta‐analysis from 76 trials for at least one of the included primary or secondary outcomes either from the published paper or via correspondence with trial authors. For the primary outcomes, we obtained data suitable for pooling for self‐reported depression scores at the post‐intervention assessment from 70 independent trials (73 independent trial arms) and, for diagnosis of depressive disorder at the medium‐term assessment, we obtained data suitable for pooling from 32 trials.

Seven trials did not provide data suitable for meta‐analysis (Karami 2012; Khalsa 2012; Lillevoll 2014; Noël 2013; Petersen 1997; Stoppelbein 2003; Wong 2014). For Karami 2012, Lillevoll 2014 and Petersen 1997, only summary statistics were presented, rather than raw data. For Khalsa 2012, change scores were reported with no information on baseline scores for the depression measure provided. In the case of Noël 2013, although the authors provided information on the number of treatment dropouts for the overall sample, the number of participants remaining in the intervention and control groups at the post‐intervention assessment was unclear. For Stoppelbein 2003, data were only reported for the total sample and subsamples, rather than for the intervention and control groups specifically. For Wong 2014, 72.8% of data were missing at post‐intervention, due to either attrition or data corruption. Given this, we decided not to include data from the trial in any analysis. The implications for this decision are that there are missing data and it is unclear what the impact on the results of the review would be if we had these data and could include them in the meta‐analyses.

The inclusion of two trials from the original review, Hyun 2005 and Schmiege 2006, involved substantial discussion between the two authors that screened the trials (GC and SH) and a third co‐author (SM). While the aim of these trials was not depression prevention per se, they were clearly targeting factors closely associated with onset of depression in groups who are at high risk of depression (in the case of Schmiege 2006 this was preventing grief with the aim of preventing depression, and in the case of Hyun 2005, participants were youths residing in a shelter), and depression was one of the key outcomes in each of these trials. Significant discussion also occurred with regards to the inclusion of Kauer 2012. This intervention involved daily monitoring of activity and mood, however it was unclear whether this information was fed back to young people themselves, in addition to GPs, and therefore whether it constituted a behavioural intervention. We felt that the act of monitoring one's actions in and of itself was sufficient to be classed as a behavioural intervention, particularly given evidence of the efficacy of this self‐management behaviour for preventing relapse of depression in adults (Ekers 2014; Ludman 2003).

There were a number of trials with multiple eligible intervention arms. For Cardemil 2002, Clarke 1993, Gillham 2007, Pössel 2008, and Schmiege 2006 we combined data across gender or ethnicity or schools as we considered that there was no strong a priori reason to suspect the efficacy of these interventions would be moderated by these factors, nor were we investigating these potential modifiers in this particular update. For a further three (Gilham 1994‐Study 2; Lillevoll 2014; Pattison 2001), although trial authors tested different components or approaches to the same intervention, we also combined data across these arms as the evaluation of the efficacy of treatment components is beyond the scope of this review.

Four trials reported data for more than one eligible arm within an intervention class (i.e. CBT, IPT) (Rohde 2014a; Rohde 2014b; Rose 2014; Sethi 2010). For Sethi 2010, we included data from the combined face‐to‐face and online therapy arm, for Rohde 2014a and Rohde 2014b, we included data from the CBT rather than bibliotherapy arms, and for Rose 2014 we included data from the combined RAP and interpersonal therapy arm.

Design

Most trials (k = 52) employed a simple randomisation procedure whereby individual participants were randomly allocated to the intervention or control groups (Arnarson 2009; Cardemil 2002; Castellanos 2006; Chaplin 2006; Charbonneau 2012; Clarke 1995; Clarke 2001; Cova 2011‐Targeted; Dobson 2010; Ellis 2011; Fleming 2012; Fresco 2009; Garber 2009; Garcia 2011; Gillham, Hamilton 2006a; Gillham 2007; Gillham 2012; Horowitz a2007; Horowitz b2007; Hyun 2005; Karami 2012; Kauer 2012; Liehr 2010; Lillevoll 2014; Makarushka 2012; Manicavasagar 2014; McCarty 2011; McCarty 2013; McLaughlin 2011; Merry 2004; Mirzamani 2012; Noël 2013; Pattison 2001; Petersen 1997; Puskar 2003; Quayle 2001; Rohde 2014a; Rohde 2014b; Seligman 1999; Seligman 2007; Sethi 2010; Shatte 1997; Snyder 2010; Stice 2006; Stice 2008; Whittaker 2012; Wijnhoven 2014; Woods 2011; Young 2006; Young 2010a; Yu 2002‐study 3). In one further trial we only used data from the Australian female sample as neither data for males nor for the Swedish sub‐sample were randomised (Livheim 2014‐study 1(girls).

The remaining 34 trials employed cluster‐randomisation whereby schools, classes or families rather than the individual were the unit of randomisation (Araya 2013; Bella‐Awusah 2015; Calear 2009; Clarke 1993; Compas 2009; Cowell 2009; Gallegos 2008; Gilham 1994‐Study 2; Gillham, Reivich 2006b; Jaycox 1994; Khalsa 2012; Kindt 2014; Kowalenko 2005; Mendelson 2010; O'Leary‐Barrett 2013; Pössel 2004; Pössel 2008; Pössel 2013; Reynolds 2011; Rivet‐Duval 2010; Roberts 2003; Roberts 2010; Rooney 2006; Rooney 2013; Rose 2014; Sawyer 2010; Schmiege 2006; Sheffield a2006; Sheffield b2006; Sheffield c2006; Stallard 2012a; Spence 2003; Stoppelbein 2003; Wong 2014).

Sample size

Sample size varied from 18 participants (Liehr 2010) to 5634 participants (Sawyer 2010).

For two trials the number of participants included in analyses was unclear (Compas 2009; Mendelson 2010). For the first trial, we calculated the sample size on the basis of the percentage of families retained by the post‐intervention assessment. For the 12‐month (medium‐term) assessment, we have used the same sample size as reported for the depression diagnosis outcome. For the second trial, as the number of participants with information on all post‐intervention outcomes was presented as a range of values (i.e. 42 to 47 in the intervention group and 40 to 43 in the control group), we have used the middle value (i.e. 45 and 42) as the sample size.

Setting

Of the trials included in this review, the majority (k = 42) had been conducted in the United States of America (Cardemil 2002; Chaplin 2006; Charbonneau 2012; Clarke 1993; Clarke 1995; Clarke 2001; Compas 2009; Cowell 2009; Fresco 2009; Garber 2009; Gilham 1994‐Study 2; Gillham, Hamilton 2006a; Gillham, Reivich 2006b; Gillham 2007; Gillham 2012; Horowitz a2007; Horowitz b2007; Jaycox 1994; Khalsa 2012; Liehr 2010; Makarushka 2012; McCarty 2011; McCarty 2013; McLaughlin 2011; Mendelson 2010; Noël 2013; Petersen 1997; Puskar 2003; Pössel 2013; Reynolds 2011; Rohde 2014a; Rohde 2014b; Schmiege 2006; Seligman 1999; Seligman 2007; Shatte 1997; Snyder 2010; Stice 2006; Stice 2008; Stoppelbein 2003; Young 2006; Young 2010a), followed by Australia (Calear 2009; Ellis 2011; Kauer 2012; Kowalenko 2005; Livheim 2014‐study 1(girls); Manicavasagar 2014; Pattison 2001; Quayle 2001; Roberts 2003; Roberts 2010; Rooney 2006; Rooney 2013; Rose 2014; Sawyer 2010; Sethi 2010; Sheffield a2006; Sheffield b2006; Sheffield c2006; Wong 2014), New Zealand (Fleming 2012; Merry 2004; Whittaker 2012; Woods 2011), the United Kingdom (Castellanos 2006; O'Leary‐Barrett 2013; Spence 2003; Stallard 2012a), Chile (Araya 2013; Cova 2011‐Targeted), Germany (Pössel 2004; Pössel 2008), the Islamic Republic of Iran (Karami 2012; Mirzamani 2012), Mexico (Gallegos 2008; Garcia 2011), The Netherlands (Kindt 2014; Wijnhoven 2014), and one each from Canada (Dobson 2010), China (Yu 2002‐study 3), Iceland (Arnarson 2009), Mauritius (Rivet‐Duval 2010), Nigeria (Bella‐Awusah 2015), Norway (Lillevoll 2014), and South Korea (Hyun 2005).

The majority of these trials (k = 67) were conducted in school settings (Araya 2013; Arnarson 2009; Bella‐Awusah 2015; Calear 2009; Cardemil 2002; Castellanos 2006; Chaplin 2006; Clarke 1993; Clarke 1995; Cova 2011‐Targeted; Cowell 2009; Dobson 2010; Fleming 2012; Gallegos 2008; Garcia 2011; Gilham 1994‐Study 2; Gillham, Hamilton 2006a; Gillham, Reivich 2006b; Gillham 2007; Gillham 2012; Horowitz a2007; Horowitz b2007; Karami 2012; Khalsa 2012; Kindt 2014; Kowalenko 2005; Lillevoll 2014; McCarty 2011; McCarty 2013; McLaughlin 2011; Mendelson 2010; Merry 2004; Mirzamani 2012; Noël 2013; O'Leary‐Barrett 2013; Pattison 2001; Petersen 1997; Pössel 2004; Pössel 2008; Pössel 2013; Puskar 2003; Quayle 2001; Rivet‐Duval 2010; Roberts 2003; Roberts 2010; Rohde 2014a; Rohde 2014b; Rooney 2006; Rooney 2013; Rose 2014; Sawyer 2010; Shatte 1997; Sheffield a2006; Sheffield b2006; Sheffield c2006; Snyder 2010; Spence 2003; Stallard 2012a; Stice 2006; Stice 2008; Stoppelbein 2003; Whittaker 2012; Wijnhoven 2014; Wong 2014; Woods 2011; Young 2006; Young 2010a; Yu 2002‐study 3). Eight were conducted in college or university settings (Charbonneau 2012; Ellis 2011; Fresco 2009; Reynolds 2011; Rohde 2014b; Seligman 1999; Seligman 2007; Sethi 2010), four were conducted in clinical settings (Clarke 2001; Compas 2009; Gillham, Hamilton 2006a; Kauer 2012), three were conducted in community settings (Hyun 2005; Liehr 2010; Schmiege 2006), and the remaining four trials were conducted in mixed settings (Garber 2009; Livheim 2014‐study 1(girls); Makarushka 2012; Manicavasagar 2014).

Participants

The age of participants at intake ranged from 8.0 years through to 24.0 years.

Twenty‐nine trials investigated the efficacy of a universal depression prevention programme delivered to unselected populations (Araya 2013; Calear 2009; Cardemil 2002; Chaplin 2006; Clarke 1993; Gallegos 2008; Horowitz a2007; Horowitz b2007; Khalsa 2012; Lillevoll 2014; Manicavasagar 2014; Merry 2004; Pattison 2001; Pössel 2004; Pössel 2008; Pössel 2013; Quayle 2001; Reynolds 2011; Rivet‐Duval 2010; Roberts 2010; Rooney 2006; Rooney 2013; Rose 2014; Sawyer 2010; Shatte 1997; Snyder 2010; Spence 2003; Whittaker 2012; Wong 2014). We coded a further four trials as universal interventions based on the trial authors' original description (Garcia 2011; Gillham 2007; Liehr 2010; Shatte 1997).

A total of 53 trials investigated the efficacy of targeted depression prevention programmes (Arnarson 2009; Bella‐Awusah 2015; Castellanos 2006; Charbonneau 2012; Clarke 1995; Clarke 2001; Compas 2009; Cowell 2009; Dobson 2010; Ellis 2011; Fleming 2012; Fresco 2009; Garber 2009; Hyun 2005; Karami 2012; Kauer 2012; Kindt 2014; Kowalenko 2005; Livheim 2014‐study 1(girls); Makarushka 2012; McCarty 2011; McCarty 2013; McLaughlin 2011; Mendelson 2010; Mirzamani 2012; Noël 2013; O'Leary‐Barrett 2013; Puskar 2003; Rohde 2014a; Rohde 2014b; Schmiege 2006; Seligman 1999; Seligman 2007; Sethi 2010; Stallard 2012a; Stice 2006; Stice 2008; Stoppelbein 2003; Wijnhoven 2014; Woods 2011; Young 2006; Young 2010a; Yu 2002‐study 3). For one additional trial (Cova 2011‐Targeted), although both a targeted and universal programme was evaluated, allocation to the universal programme was not randomised. We have therefore only presented data for the targeted intervention arm in this review. We coded seven further trials as a targeted based on the trial authors' original description of the intervention despite the fact that although the programmes originally aimed to recruit only children with high depression scores, in the case of there being small classes all children were included regardless of their current levels of depression symptoms (Gilham 1994‐Study 2; Gillham, Hamilton 2006a; Gillham, Reivich 2006b; Gillham 2012; Jaycox 1994; Petersen 1997; Roberts 2003).

For the majority of these trials the population was selected on the basis of elevated depression symptoms and we therefore classed them as indicated programmes; in some the population was selected on the basis of a risk factor for depression, and in some they were selected on the basis of both elevated symptoms and some risk factor as described below. Risk was defined on the basis of:

elevated depression symptoms (k = 36: Arnarson 2009; Bella‐Awusah 2015; Clarke 1995; Charbonneau 2012; Cova 2011‐Targeted; Dobson 2010; Ellis 2011; Gilham 1994‐Study 2; Gillham, Hamilton 2006a; Gillham, Reivich 2006b; Gillham 2012; Kauer 2012; Kowalenko 2005; Livheim 2014‐study 1(girls); Makarushka 2012; McCarty 2011; McCarty 2013; McLaughlin 2011; Mirzamani 2012; Petersen 1997; Puskar 2003; Roberts 2003; Rohde 2014a; Rohde 2014b; Seligman 2007; Sethi 2010; Sheffield a2006; Sheffield b2006; Stallard 2012a; Stice 2006; Stice 2008; Stoppelbein 2003; Wijnhoven 2014; Woods 2011; Young 2006; Young 2010a);

elevated depressive symptoms and poor family relationships or perceived family conflict (k = 2: Jaycox 1994; Yu 2002‐study 3);

elevated depression symptoms and a parent with a history of depression (k = 2: Clarke 2001; Garber 2009);

elevated depression symptoms and living in a rural area (k = 1: Noël 2013);

elevated personality symptoms (e.g. negative thinking, hopelessness) (k = 2: Castellanos 2006; O'Leary‐Barrett 2013);

a pessimistic attributional style (k = 2: Seligman 1999; Fresco 2009);

a parent with current depression (k = 1: Compas 2009);

recent (≤ 2 years) parental bereavement (k = 1: Schmiege 2006);

recent (duration unclear) parental divorce (k = 1: Karami 2012);

being the child of a Mexican immigrant woman (k = 1: Cowell 2009);

excluded or at risk of being excluded from mainstream education (k = 1: Fleming 2012);

residing in a shelter for homeless and runaway youth (k = 1: Hyun 2005);

residing in a disadvantaged/underserved urban neighbourhood (k = 1: Mendelson 2010);

attending a school located in a low‐income neighbourhood (k = 1: Kindt 2014).

In one further trial, one arm of the prevention programme was implemented in a targeted population (Sheffield a2006), one arm was implemented in a mixed population (Sheffield b2006), and one arm was delivered to an unselected population (Sheffield c2006).