Abstract

Background

Treatment guidelines for asthma recommend inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) as first‐line therapy for children with persistent asthma. Although ICS treatment is generally considered safe in children, the potential systemic adverse effects related to regular use of these drugs have been and continue to be a matter of concern, especially the effects on linear growth.

Objectives

To assess the impact of ICS on the linear growth of children with persistent asthma and to explore potential effect modifiers such as characteristics of available treatments (molecule, dose, length of exposure, inhalation device) and of treated children (age, disease severity, compliance with treatment).

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register of trials (CAGR), which is derived from systematic searches of bibliographic databases including CENTRAL, MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED and PsycINFO; we handsearched respiratory journals and meeting abstracts. We also conducted a search of ClinicalTrials.gov and manufacturers' clinical trial databases to look for potential relevant unpublished studies. The literature search was conducted in January 2014.

Selection criteria

Parallel‐group randomised controlled trials comparing daily use of ICS, delivered by any type of inhalation device for at least three months, versus placebo or non‐steroidal drugs in children up to 18 years of age with persistent asthma.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently performed study selection, data extraction and assessment of risk of bias in included studies. We conducted meta‐analyses using the Cochrane statistical package RevMan 5.2 and Stata version 11.0. We used the random‐effects model for meta‐analyses. We used mean differences (MDs) and 95% CIs as the metrics for treatment effects. A negative value for MD indicates that ICS have suppressive effects on linear growth compared with controls. We performed a priori planned subgroup analyses to explore potential effect modifiers, such as ICS molecule, daily dose, inhalation device and age of the treated child.

Main results

We included 25 trials involving 8471 (5128 ICS‐treated and 3343 control) children with mild to moderate persistent asthma. Six molecules (beclomethasone dipropionate, budesonide, ciclesonide, flunisolide, fluticasone propionate and mometasone furoate) given at low or medium daily doses were used during a period of three months to four to six years. Most trials were blinded and over half of the trials had drop out rates of over 20%.

Compared with placebo or non‐steroidal drugs, ICS produced a statistically significant reduction in linear growth velocity (14 trials with 5717 participants, MD ‐0.48 cm/y, 95% CI ‐0.65 to ‐0.30, moderate quality evidence) and in the change from baseline in height (15 trials with 3275 participants; MD ‐0.61 cm/y, 95% CI ‐0.83 to ‐0.38, moderate quality evidence) during a one‐year treatment period.

Subgroup analysis showed a statistically significant group difference between six molecules in the mean reduction of linear growth velocity during one‐year treatment (Chi² = 26.1, degrees of freedom (df) = 5, P value < 0.0001). The group difference persisted even when analysis was restricted to the trials using doses equivalent to 200 μg/d hydrofluoroalkane (HFA)‐beclomethasone. Subgroup analyses did not show a statistically significant impact of daily dose (low vs medium), inhalation device or participant age on the magnitude of ICS‐induced suppression of linear growth velocity during a one‐year treatment period. However, head‐to‐head comparisons are needed to assess the effects of different drug molecules, dose, inhalation device or patient age. No statistically significant difference in linear growth velocity was found between participants treated with ICS and controls during the second year of treatment (five trials with 3174 participants; MD ‐0.19 cm/y, 95% CI ‐0.48 to 0.11, P value 0.22). Of two trials that reported linear growth velocity in the third year of treatment, one trial involving 667 participants showed similar growth velocity between the budesonide and placebo groups (5.34 cm/y vs 5.34 cm/y), and another trial involving 1974 participants showed lower growth velocity in the budesonide group compared with the placebo group (MD ‐0.33 cm/y, 95% CI ‐0.52 to ‐0.14, P value 0.0005). Among four trials reporting data on linear growth after treatment cessation, three did not describe statistically significant catch‐up growth in the ICS group two to four months after treatment cessation. One trial showed accelerated linear growth velocity in the fluticasone group at 12 months after treatment cessation, but there remained a statistically significant difference of 0.7 cm in height between the fluticasone and placebo groups at the end of the three‐year trial.

One trial with follow‐up into adulthood showed that participants of prepubertal age treated with budesonide 400 μg/d for a mean duration of 4.3 years had a mean reduction of 1.20 cm (95% CI ‐1.90 to ‐0.50) in adult height compared with those treated with placebo.

Authors' conclusions

Regular use of ICS at low or medium daily doses is associated with a mean reduction of 0.48 cm/y in linear growth velocity and a 0.61‐cm change from baseline in height during a one‐year treatment period in children with mild to moderate persistent asthma. The effect size of ICS on linear growth velocity appears to be associated more strongly with the ICS molecule than with the device or dose (low to medium dose range). ICS‐induced growth suppression seems to be maximal during the first year of therapy and less pronounced in subsequent years of treatment. However, additional studies are needed to better characterise the molecule dependency of growth suppression, particularly with newer molecules (mometasone, ciclesonide), to specify the respective role of molecule, daily dose, inhalation device and patient age on the effect size of ICS, and to define the growth suppression effect of ICS treatment over a period of several years in children with persistent asthma.

Plain language summary

Do inhaled corticosteroids reduce growth in children with persistent asthma?

Review question: We reviewed the evidence on whether inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) could affect growth in children with persistent asthma, that is, a more severe asthma that requires regular use of medications for control of symptoms.

Background: Treatment guidelines for asthma recommend ICS as first‐line therapy for children with persistent asthma. Although ICS treatment is generally considered safe in children, parents and physicians always remain concerned about the potential negative effect of ICS on growth.

Search date: We searched trials published until January 2014.

Study characteristics: We included in this review trials comparing daily use of corticosteroids, delivered by any type of inhalation device for at least three months, versus placebo or non‐steroidal drugs in children up to 18 years of age with persistent asthma.

Key results: Twenty‐five trials involving 8471 children with mild to moderate persistent asthma (5128 treated with ICS and 3343 treated with placebo or non‐steroidal drugs) were included in this review. Eighty percent of these trials were conducted in more than two different centres and were called multi‐centre studies; five were international multi‐centre studies conducted in high‐income and low‐income countries across Africa, Asia‐Pacifica, Europe and the Americas. Sixty‐eight percent were financially supported by pharmaceutical companies.

Meta‐analysis (a statistical technique that combines the results of several studies and provides a high level of evidence) suggests that children treated daily with ICS may grow approximately half a centimeter per year less than those not treated with these medications during the first year of treatment. The magnitude of ICS‐related growth reduction may depend on the type of drug. Growth reduction seems to be maximal during the first year of therapy and less pronounced in subsequent years of treatment. Evidence provided by this review allows us to conclude that daily use of ICS can cause a small reduction in height in children up to 18 years of age with persistent asthma; this effect seems minor compared with the known benefit of these medications for asthma control.

Quality of evidence: Eleven of 25 trials did not report how they guaranteed that participants had an equal chance of receiving ICS or placebo or non‐steroidal drugs. All but six trials did not report how researchers were kept unaware of the treatment assignment list. However, this methodological limitation may not significantly affect the quality of evidence because the results remained almost unchanged when we excluded these trials from the analysis.

Summary of findings

for the main comparison.

| Inhaled corticosteroids compared with placebo or non‐steroidal drugs for children with persistent asthma: effects on growth | ||||||

|

Patient or population: children up to 18 years of age with persistent asthma Settings: outpatient Intervention: inhaled corticosteroids Comparison: placebo or non‐steroidal drugs | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Mean difference (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo or non‐steroidal drugs | Inhaled corticosteroids1 | |||||

| Linear growth velocity in first year of treatment (cm/y) | Mean linear growth velocity ranged across control groups from 5.5 to 8.5 cm/y | Mean reduction in linear growth velocity was 0.48 cm/y | ‐0.48 cm/y (‐0.65 to ‐0.30) less growth in the ICS group | 5717 (14 trials) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2, 3 | |

| Change from baseline in height over first year of treatment (cm) | Mean change from baseline in height over a 1‐year period ranged across the control groups from 4.7 to 8.6 cm/y | Mean reduction in change from baseline in height over a 1‐year period was 0.61 cm | ‐0.61 cm (‐0.83 to ‐0.38) less growth in the ICS group | 3275 (15 trials) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2,3 | |

| Change in height standard deviation score (SDS) in first year of treatment | Mean change in height SDS score across control groups from ‐0.09 to 0.5 | Mean reduction in change in height SDS score was 0.13 | ‐0.13 (‐0.24 to ‐0.01) less growth in the ICS group | 258 (4 trials) |

⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2,3 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Inhaled corticosteroids included beclomethasone dipropionate, budesonide, ciclesonide, flunisolide, fluticasone propionate and mometasone fumarate.

2A considerable number of included trials did not report the methods of random sequence generation and allocation concealment and had high withdrawal rates, especially in the control groups (deduct 1 point for limitations)

3Significant heterogeneity was noted in results across studies that may be expected because of differences in the molecule, daily dose and age group across trials. However, all trials showed negative effects of ICS on growth, suggesting that the heterogeneity is quantitative but not qualitative and may not significantly affect the conclusions of this review (do not deduct point for inconsistency)

Background

Description of the condition

According to the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) (GINA 2014), asthma is operationally defined as "a chronic inflammatory disorder of the airways in which many cells and cellular elements play a role. The chronic inflammation is associated with airway hyperresponsiveness that leads to recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness, and coughing, particularly at night or in the early morning. These episodes are usually associated with widespread, but variable, airflow obstruction within the lung that is often reversible either spontaneously or with treatment." During childhood, asthma is a phenotypically heterogeneous condition with a wide spectrum of symptoms and severity (Bush 2004; Stein 2004). This fact makes the diagnosis and treatment of childhood asthma challenging.

In developed countries, the prevalence of asthma has markedly increased over the past 40 to 50 years, especially among the paediatric population (Asher 2010; ISAAC 1998; Masoli 2004). In these countries, asthma has emerged as a major public health problem because of high prevalence, associated morbidity and substantial healthcare costs and societal burden. However, evidence recently provided by the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) suggests that the prevalence of asthma may have reached a plateau in many developed countries (Asher 2010; Lai 2009). In contrast, asthma prevalence is sharply increasing in developing countries (Africa, Central and South America, Asia and the Pacific region), probably as the result of rapid and ongoing urbanisation and westernisation (Asher 2010; Braman 2006). The global burden of childhood asthma is continuing to rise.

Description of the intervention

Chronic airway inflammation is the primary underlying pathology of asthma, regardless of phenotype and disease severity (Busse 2001; GINA 2014). Through complex interaction between various cells and inflammatory mediators, the inflammatory process in the airways leads to vascular leakage, bronchoconstriction, hypersecretion of mucus, inflammatory cell infiltration, airway hyperresponsiveness and ultimately airway remodelling (GINA 2014; NHLBI 2007). These pathophysiological changes are responsible for clinical and functional manifestations of asthma. Thus, airway inflammation is the most important target of therapy in long‐term asthma management.

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are currently considered first‐line treatment for persistent asthma, both in adults and in children (BTS & SIGN 2012; GINA 2014; Lougheed 2012; NHLBI 2007). Studies have demonstrated clinical benefits of ICS in controlling asthma symptoms, reducing exacerbations and hospitalisations, decreasing airway hyperresponsiveness and airway inflammation, improving pulmonary function, improving quality of life and reducing asthma‐related deaths (Adams 2011a; Adams 2011b; Adams 2011c; Covar 2003; Juniper 1990; Olivieri 1997; Suissa 2000; Van Essen‐Zandvliet 1992; Van Rens 1999). Seven ICS are currently available for clinical use worldwide: beclomethasone dipropionate, budesonide, ciclesonide, flunisolide, fluticasone propionate, mometasone furoate and triamcinolone acetate. Each ICS has different pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties and biologic characteristics; however, all ICS can achieve similar therapeutic benefits when given at equipotent doses (BTS & SIGN 2012; GINA 2014; Lougheed 2012). Optimal doses of ICS for persistent childhood asthma remain unclear. The most recent asthma guidelines recommend low‐dose ICS (<200 μg/d of hydrofluoroalkane (HFA)‐beclomethasone or equivalent) for children with mild to moderate persistent asthma; however, children with more severe asthma and those with poor response to low doses of ICS may require higher doses to achieve satisfactory asthma control (BTS & SIGN 2012; GINA 2014; Lougheed 2012).

Although ICS are generally considered safe as treatment for children with asthma, the potential systemic adverse effects related to long‐term use of these drugs, especially the effects on growth, have been and continue to be a matter of concern (Allen 1998; Allen 2002; Pedersen 2001). In 1998, based on a report of the panel of experts, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) stated that labels warning of a potential reduction in growth in children are required on all ICS products (FDA 1998). Since that time, the relationship between ICS and growth impairment in children with asthma has been extensively discussed in the literature (Allen 2006; Brand 2001; Carlsen 2002; Creese 2001; Price 2002; Salvatoni 2003; Sizonenko 2002; Witzmann 2000; Wolthers 2001).

How the intervention might work

Currently, ICS are the most potent anti‐inflammatory drugs available for the long‐term treatment of persistent asthma. The therapeutic benefits of ICS have been directly related to a decrease in airway inflammation (Djukanovic 1992).

The molecular mechanisms by which ICS exert anti‐inflammatory effects are not entirely understood. ICS are believed to bind with cytoplasmic glucocorticoid receptors in target cells (Barnes 2006; Colice 2000; Leung 2003; Sobande 2008). The corticosteroid‐receptor complexes translocate to the cell nucleus, acting as a transcriptional modulator to repress expression of inflammatory genes. However, the interaction with corticosteroid response genes may not explain entirely the anti‐inflammatory effects of ICS. Corticosteroids have recently been found to interact with other cytoplasmic factors, such as activator protein‐1 and nuclear factor‐kB, which also affect genomic transcription (Colice 2000).

The mechanism of corticosteroid‐induced growth impairment also is not yet clearly understood. Corticosteroids are known to inhibit growth hormone (GH) secretion, insulin‐like growth factor‐1 (IGF‐1) bioactivity, collagen synthesis and adrenal androgen production (Allen 1998; Wolthers 1997). In addition to altering GH output, corticosteroids may reduce GH receptor expression and uncouple the receptors from their signal transduction mechanisms (Allen 1998; Pedersen 2001). Furthermore, corticosteroids may exert a direct growth‐retarding effect on the growth plates (Allen 1998). However, results regarding the association between ICS and alterations in production or activity of GH and IGF‐1 have been inconsistent (Hedlin 1998; Wolthers 1997).

Why it is important to do this review

One Cochrane systematic review with five randomised trials (Sharek 2000a) suggests that moderate doses of inhaled beclomethasone and fluticasone cause a decrease in linear growth velocity of 1.51 cm/y and 0.43 cm/y, respectively. This Cochrane review has been converted to a journal article (Sharek 2000b). Over the past 10 years, several newly undertaken randomised trials have used various new and old inhaled corticosteroid molecules (Becker 2006; Bensch 2011; Gillman 2002; Guilbert 2006; Martinez 2011; Pedersen 2010; Skoner 2008; Skoner 2011; Sorkness 2007; Wasserman 2006). We therefore decided to conduct this systematic review with the goal of evaluating the adverse effects of all currently available ICS on growth in children with persistent asthma. Factors that may influence ICS‐induced growth suppression, such as molecule, dosage, inhalation device, duration of exposure, compliance with treatment, disease severity and participant age, were explored.

Objectives

To assess the impact of ICS on the linear growth of children with persistent asthma and to explore potential effect modifiers such as characteristics of available treatments (molecule, dose, length of exposure, inhalation device) and of treated children (age, disease severity, compliance with treatment).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Parallel‐group randomised controlled trials.

Types of participants

Children up to 18 years of age with the diagnosis of persistent asthma.

Types of interventions

Daily use of ICS, delivered by any type of inhalation device for at least three months, compared with placebo or non‐steroidal drugs.

Comparisons are as follows.

ICS alone versus placebo.

ICS alone versus non‐steroidal drugs, such as long‐acting beta2‐agonists (LABA) and leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRA).

ICS associated with non‐steroidal drugs versus same dose of non‐steroidal drugs.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Linear growth velocity, obtained by measuring height at a number of time points during the study and performing linear regression of height against time (Price 2002). The slope of the regression gives linear growth velocity, expressed in cm/year (y) or mm/week (wk).

Secondary outcomes

Change in height standard deviation score (SDS) over time, defined as the difference between an individual's growth velocity and predicted normal growth velocity divided by the predicted normal growth velocity standard deviation (SD) for individuals of the same age, sex and ethnicity, if available (Pedersen 2001).

Change from baseline in height (cm) over time.

Change in height z‐score over time.

We did not intend to include lower leg length measured by knemometry as the outcome because this measurement correlates poorly with statural height and tends to overestimate potential effects of ICS on growth (Allen 1999; Efthimiou 1998). We added adult height (cm) and catch‐up growth after cessation of ICS as post hoc secondary outcomes.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We identified trials from the Cochrane Airways Group Specialised Register of trials (CAGR), which is derived from systematic searches of bibliographic databases including the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, AMED and PsycINFO, and we handsearched respiratory journals and meeting abstracts (please see Appendix 1 for further details). All records in the CAGR coded as 'asthma' were searched using the following terms:

(((steroid* or corticosteroid* or glucocorticoid* ) and inhal*) or budesonide or Pulmicort or fluticasone or Flixotide or Flovent or ciclesonide or Alvesco or triamcinolone or Kenalog or beclomethasone or Becotide or Becloforte or Becodisk or QVAR or Flunisolide or AeroBid or mometasone or Asmanex or Symbicort or Advair or Inuvair)

AND

(grow* or height* or SDS)

AND

(child* or paediat* or pediat* or adolesc* or teen* or prepubertal* or pre‐pubertal* or puberty or pubertal* or infan* or toddler* or bab* or young*)

We also conducted a search of ClinicalTrials.gov. All databases were searched from their inception to the present time, and language of publication was not restricted. The initial searches were conducted in November 2011, and an updated search was conducted in February 2013 and January 2014.

Searching other resources

We checked reference lists of all primary studies and review articles to look for additional references. We also searched manufacturers' clinical trial databases to uncover potential relevant unpublished studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed the titles and abstracts of all potential studies identified by the search strategy. Full‐text articles were retrieved when studies appeared to meet the inclusion criteria, or when data in the title and abstract were insufficient to allow a clear decision regarding their inclusion. We resolved disagreements through discussion; if required, we consulted the third review author.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (LZ, SOMP) independently extracted data from the included trials using specially designed and pilot‐tested data extraction forms. For trials with multiple reports, we extracted data from each report separately and combined information across multiple data collection forms afterwards. We resolved disagreements by discussion and entered the extracted data into RevMan version 5.1 (Review Manager 5).

We extracted the following data.

Study characteristics: year of publication, name of first author, country of origin, setting and source/sponsorship.

Methods: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, completeness of outcome data, selective reporting and other sources of bias.

Participants: sample size, demographics and inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Intervention: type of inhaled corticosteroid, dosage, frequency of administration, inhalation device, treatment duration and compliance with treatment.

Comparator: placebo or non‐steroidal drugs (same details as for the intervention).

Co‐interventions.

Results: mean value of outcome measures in each group, SD or other metrics for uncertainty (standard errors (SE), confidence intervals (CI), t values or P values for differences in means) of outcome measurements in each group, number of participants who underwent randomisation and number of participants in each group for whom outcomes were measured.

We converted SE or 95% CI to SD using the calculator of RevMan (Review Manager 5). We used Engauge digitising software (digitizer.sourceforge.net) to extract data from figures for linear growth velocity (CAMP 2000; Guilbert 2006; Skoner 2011), change from baseline in height (Becker 2006; Bisgaard 2004; Guilbert 2006; Martinez 2011; Skoner 2008) and change in height SDS (Kannisto 2000; Turpeinen 2008; Verberne 1997) in the first year of treatment. We also extracted data from figures to determine change from baseline in height during three to eight months of treatment (Allen 1998; Becker 2006; Bensch 2011; Bisgaard 2004; Doull 1995; Martinez 2011; Skoner 2008; Skoner 2011) and linear growth velocity in the second year (CAMP 2000; Guilbert 2006) and the third year of treatment (CAMP 2000). Data from each figure were extracted twice by the same review author (LZ), at points at least one week apart. The mean of two measurements was used.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (LZ, SOMP) independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). Disagreements were resolved by discussion or by involving the third review author. We assessed risk of bias according to the following domains.

Allocation sequence generation.

Concealment of allocation.

Blinding of participants and investigators.

Incomplete outcome data.

Selective outcome reporting.

We also noted other sources of bias. We graded each potential source of bias as yes, no or unclear, on the basis of whether the potential for bias was low, high or unknown, respectively.

Measures of treatment effect

Measurements of growth are continuous outcomes, so we used mean differences (MDs) and 95% CIs as the metrics to determine treatment effects. A negative value for MD indicates that ICS have suppressive effects on linear growth compared with controls. The lower limit of the 95% CI corresponds to the maximum potential reduction in growth.

Unit of analysis issues

We considered each individual comparison as the unit of analysis. For comparison between participants treated with ICS and controls, we combined different doses of the same molecule into a single corticosteroid group (Allen 1998; Skoner 2008; Skoner 2011). We also combined different age groups (Gillman 2002) and different gender groups (Roux 2003) into a single treatment group. The methods used for combining groups were based on recommendations provided by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). When both placebo and non‐steroidal drugs were used as controls (Becker 2006; CAMP 2000; Simons 1997), we used only the data from the placebo group for comparison with data from the intervention group. For subgroup analyses, when trials compared two or more ICS molecules (Gillman 2002; Kannisto 2000) or different doses of the same molecule (Allen 1998; Skoner 2008; Skoner 2011) versus the control group, we considered the comparison between each molecule or each dose and controls as a unit of analysis. In this case, we split the original control group into two or more small control groups with equal numbers of participants. One trial (Gradman 2010) contributed data for the subgroup analysis of change from baseline in height at six and eight months, so we split each treatment group into two small groups consisting of equal numbers of participants.

Dealing with missing data

Seven trials did not report SDs or other metrics of uncertainty for growth measurements. For five trials (Guilbert 2006; Roux 2003; Simons 1997; Skoner 2011; Tinkelman 1993), we obtained SDs from P values, SEs or 95% CIs to determine mean differences between groups. For two trials, we imputed missing SDs of mean change from baseline in height (Becker 2006) and missing SDs of linear growth velocity (Gillman 2002) by using SDs of linear growth velocity and mean changes from baseline in height, respectively, because the two measurements had similar values. In another trial (CAMP 2000), we imputed missing SDs of linear growth rate using SDs from the other trial (Jonasson 2000) in the same corticosteroid subgroup.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We used the I² statistic to measure heterogeneity among the trials in each analysis. The I² statistic ranges from 0% to 100% and measures the degree of inconsistency across studies, with values of 25%, 50% and 75% corresponding to low, moderate and high heterogeneity, respectively (Higgins 2003). We conducted prespecified subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses to explore potential sources of heterogeneity and the possibility of effect modifiers.

Assessment of reporting biases

When we suspected reporting bias (see 'Selective reporting bias' above), we attempted to contact study authors to ask them to provide missing outcome data. When this was not possible, and the missing data were thought to introduce serious bias, we explored the impact of excluding such studies from the overall assessment of results by performing a sensitivity analysis. We used funnel plots and Egger's test to assess potential publication bias (Higgins 2003).

Data synthesis

Effects of ICS on linear growth were assessed at five time points of treatment: three to five months, six to eight months, one or nearly one year, two years and three years. In one trial (Turpeinen 2008) with 18‐month treatment, growth data obtained between seven and 18 months were used for analysis at the one‐year time point because ICS was given at a constant dose during this period rather than on a step‐down schedule during the first six months of treatment. In another trial involving 75 children (Kannisto 2000), growth data from 32 children treated with the same drug at a constant dose throughout the whole year were used for the analysis of change in height SDS at the one‐year time point. In the trial of Pauwels 2003, a total of 3195 children five to17 years of age were recruited, but data on linear growth were available for only 1974 children five to 10 years of age.

We performed meta‐analyses using the Cochrane statistical package RevMan 5 (Review Manager 5). We used the random‐effects model for meta‐analyses because it is more appropriate than the fixed‐effect model and provides more conservative estimates with wider CIs when heterogeneity across studies is significant. Otherwise, the two models generate similar results.

When trials reported summarised data on growth measurement such as MD and SE between treatment groups, rather than mean and uncertainty of measurement in each treatment group, we included such trials in the meta‐analysis using MD and SE between treatment groups.

We used the number of participants who contributed data for analysis rather than the intention‐to‐treat population for meta‐analysis because the main aim of this review was to answer the question of whether use of ICS would cause growth suppression in ICS‐treated children with persistent asthma.

We evaluated the quality of the evidence using GRADE methodology and prepared a summary of findings table using the outcomes Linear growth velocity in first year of treatment (cm/y), change from baseline in height over first year of treatment (cm), change in height standard deviation score (SDS) in first year of treatment. We decided to do this post hoc.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned, a priori, to carry out seven subgroup analyses to explore potential sources of heterogeneity.

Type of ICS: beclomethasone dipropionate, budesonide, ciclesonide, flunisolide, fluticasone propionate, mometasone fumarate, triamcinolone acetate.

Inhalation device: chlorofluorocarbon (CFC)‐metered‐dose inhaler (CFC‐MDI), HFA‐MDI, dry powder inhaler (DPI), nebuliser.

Daily dose of ICS: low, medium and high daily doses of seven ICS based on GINA criteria (GINA 2014): CFC‐beclomethasone: 100 to 200 μg, > 200 to 400 μg, > 400 μg; HFA‐beclomethasone: 50 to 100 μg, > 100 to 200 μg, > 200 μg; budesonide (DPI): 100 to 200 μg, > 200 to 400 μg, > 400 μg; nebulised‐budesonide: 250 to 500 μg, > 500 to 1000 μg, > 1000 μg; ciclesonide: 100 μg, > 100 to 200 μg, > 200 μg; fluticasone propionate: 100 to 200 μg, > 200 to 500 μg, > 500 μg; mometasone furoate: 110 μg, ≥ 220 μg, ≥ 440 μg; triamcinolone acetonide: 400 to 800 μg, > 800 to 1200 μg, > 1200 μg. Dose categories of flunisolide were defined according to GINA 2012 criteria as low (500 to 750 μg), medium (> 750 to 1250 μg) and high (> 1250 μg). All doses of ICS were reported on the basis of ex‐valve rather than ex‐inhaler values. This classification does not refer to dose equivalence but rather to estimated clinical comparability. GINA dose categories of ICS are based on published information and available studies, including direct comparisons when available. We estimated equivalent doses of ICS according to British Thoracic Society (BTS) criteria (BTS & SIGN 2012).

Duration of exposure: three to six months, > six to 12 months, > 12 months.

Asthma severity: mild, moderate and severe persistent asthma.

Age of participants: preschoolers (two to five years), prepubertal children (> five to 12 years), adolescent (> 12 to 18 years).

Concomitant use of non‐steroidal antiasthmatic drugs: ICS alone, ICS combined with non‐steroidal drugs.

We did not perform the planned subgroup analysis on duration of exposure, as the meta‐analysis was conducted at five time points of treatment that were different from those specified a priori. Data derived from the included trials were suitable only for conducting subgroup analyses on type of ICS, inhalation device, daily dose of ICS (low vs medium) and participant age (toddlers and preschoolers vs prepubertal children). We conducted post hoc subgroup analyses on molecules, devices and doses, selecting trials in which only one factor varied. Given that the number of subgroups is generally small, a P value < 0.10 rather than the conventional level of 0.05 was considered statistically significant for the Chi² test in detecting differences between subgroups.

We did not perform the planned meta‐regression analysis to explore the respective role of molecule, daily dose, inhalation device and participant age on the effect size of ICS‐induced growth suppression because all four co‐variates are highly correlated. In this case, it is impossible to untangle the independent effect of each co‐variate (Higgins 2011). Moreover, such analysis has low statistical power because of the relatively small number of included trials.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was used to assess the potential impact of particular decisions or missing information on the findings of the review (Higgins 2011). We conducted, as planned a priori, the following sensitivity analyses.

Exclusion from the analysis of trials with high risk of bias due to missing data or unbinding, or both.

Exclusion from the analysis of trials in which the compliance rate with ICS was lower than 75%, or in which no data regarding compliance with treatment were provided.

Exclusion from the analysis of pharmaceutical industry–sponsored trials.

We also conducted post hoc sensitivity analyses and excluded trials in which withdrawal rates were higher than 20%, trials in which non‐steroidal drugs rather than placebo were used as controls, trials in which participants previously receiving ICS for longer than one month before study entry were included and trials in which growth data used for analysis were extracted from the figures or were obtained over a portion of the treatment period, rather than over the entire treatment period.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

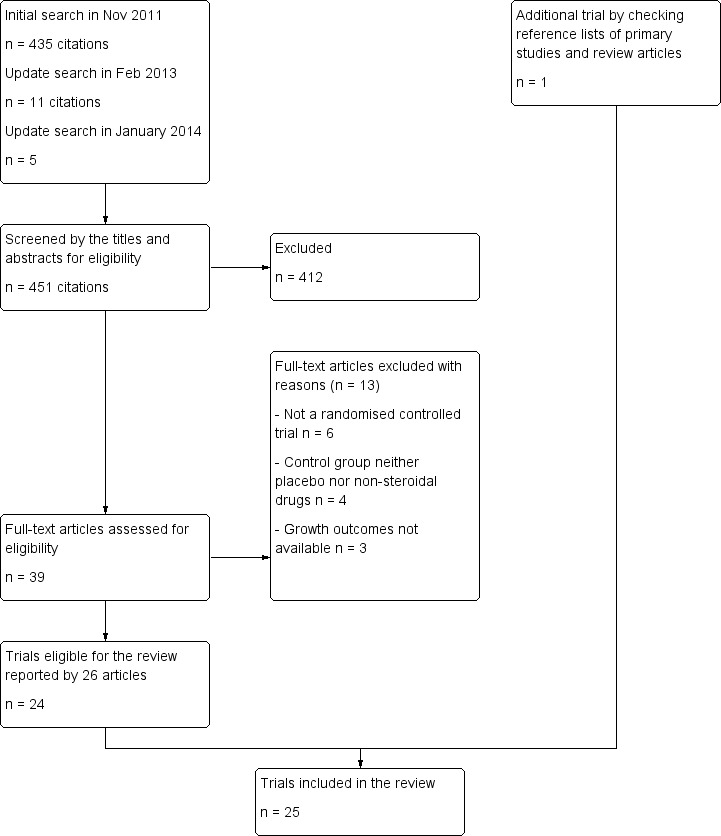

The initial search of electronic databases in November 2011 yielded 435 citations, and the update search in February 2013 and in January 2014 revealed 11 and five citations, respectively. After screening the titles and abstracts, we identified 39 papers as potentially relevant, each of which we reviewed in full text. A total of 13 articles were excluded after full review, leaving 26 articles reporting 24 trials for inclusion in this review. We found one additional trial by checking reference lists of primary studies and review articles. Thus 25 trials were included in this review (Figure 1).

1.

Flow diagram of trial selection.

Included studies

See Characteristics of included studies.

We included 25 trials involving 8471 children with mild to moderate persistent asthma, of whom 5128 were treated with ICS and 3343 with placebo or non‐steroidal drugs.

Design

All 25 studies were randomised, parallel‐group, controlled trials. All but five (Gradman 2010; Jonasson 2000; Kannisto 2000; Storr 1986; Turpeinen 2008) were multi‐centre trials. Five (Becker 2006; Bisgaard 2004; Pauwels 2003; Pedersen 2010; Skoner 2008) were international multi‐centre studies. With the exception of eight studies (CAMP 2000; Gradman 2010; Guilbert 2006; Jonasson 2000; Kannisto 2000; Martinez 2011; Sorkness 2007; Storr 1986), all included trials were sponsored by pharmaceutical companies.

Participants

Four trials (Bisgaard 2004; Guilbert 2006; Storr 1986; Wasserman 2006) involved toddlers and preschoolers one to five years of age, 13 trials (Becker 2006; Bensch 2011; CAMP 2000; Doull 1995; Gillman 2002; Gradman 2010; Pauwels 2003; Pedersen 2010; Price 1997; Skoner 2008; Skoner 2011; Tinkelman 1993; Turpeinen 2008) involved prepubertal children four to 12 years of age and eight trials (Jonasson 2000; Kannisto 2000; Martinez 2011; Roux 2003; Simons 1997; Sorkness 2007; Tinkelman 1993; Verberne 1997) involved prepubertal and pubertal children five to 18 years of age. All trials described gender (male) ratios from 46% to 75%. Diagnosis of asthma was based on American Thoracic Society (ATS), National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) or GINA criteria (Allen 1998; Becker 2006; Gradman 2010; Jonasson 2000; Martinez 2011; Pedersen 2010; Skoner 2008; Skoner 2011; Turpeinen 2008; Verberne 1997), on both symptoms and spirometry test results (Bensch 2011; CAMP 2000; Gillman 2002; Pauwels 2003; Roux 2003; Simons 1997; Tinkelman 1993) or on symptoms alone (Doull 1995; Price 1997). Three trials (Kannisto 2000; Sorkness 2007; Wasserman 2006) did not report the criteria used for diagnosis of asthma. Another three trials involved toddlers/preschoolers with recurrent wheezing (Bisgaard 2004; Storr 1986) or recurrent wheezing and a positive asthma predictive index (Guilbert 2006). Twenty trials used frequency of asthma symptoms and baseline forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) as the criteria for classification of asthma severity. Eleven trials (Becker 2006; Bensch 2011; Gradman 2010; Jonasson 2000; Pauwels 2003; Price 1997; Roux 2003; Simons 1997; Skoner 2008; Skoner 2011; Turpeinen 2008) involved participants with mild persistent asthma, seven (CAMP 2000; Doull 1995; Gillman 2002; Pedersen 2010; Sorkness 2007; Tinkelman 1993; Verberne 1997) involved participants with mild to moderate persistent asthma and five (Bisgaard 2004; Guilbert 2006; Kannisto 2000; Storr 1986; Wasserman 2006) failed to report the severity of asthma or asthma‐like symptoms.

Eight trials (Becker 2006; Doull 1995; Jonasson 2000; Kannisto 2000; Price 1997; Roux 2003; Skoner 2011; Storr 1986) included only steroid‐naïve participants, that is, those with no previous regular use of ICS or duration of use less than two weeks before study entry. Six trials included only participants who had previously used ICS for less than one month (Pauwels 2003; Simons 1997; Tinkelman 1993), two months (Bensch 2011) and four months (Guilbert 2006; Turpeinen 2008). In the remaining trials, no restriction was placed on previous use of ICS, and the prevalence of such use ranged from 15.6% to 88% among included participants.

Interventions

The ICS molecule used was beclomethasone dipropionate (Becker 2006; Doull 1995; Gillman 2002; Martinez 2011; Simons 1997; Storr 1986; Tinkelman 1993; Verberne 1997), budesonide (CAMP 2000; Gradman 2010; Jonasson 2000; Kannisto 2000; Pauwels 2003; Turpeinen 2008), ciclesonide (Pedersen 2010; Skoner 2008), flunisolide (Bensch 2011; Gillman 2002), fluticasone propionate (Allen 1998; Bisgaard 2004; Guilbert 2006; Price 1997; Roux 2003; Sorkness 2007; Wasserman 2006) or mometasone furoate (Skoner 2011). Different inhaler devices used included CFC‐MDI, HFA‐MDI, DPI (Diskhaler or Turbuhaler) and nebuliser (further details are available in Table 2 and under Characteristics of included studies). Durations of intervention included 12 weeks (Pedersen 2010; Wasserman 2006), 26 to 30 weeks (Doull 1995; Storr 1986), 44 to 48 weeks (Martinez 2011; Sorkness 2007), 52 to 56 weeks (Allen 1998; Becker 2006; Bensch 2011; Bisgaard 2004; Gillman 2002; Gradman 2010; Kannisto 2000; Price 1997; Simons 1997; Skoner 2008; Skoner 2011; Tinkelman 1993; Verberne 1997), two years (Guilbert 2006; Jonasson 2000; Roux 2003), three years (Pauwels 2003) and four to six years (CAMP 2000). Treatment compliance was not measured or reported in nine trials (Gillman 2002; Kannisto 2000; Martinez 2011; Pauwels 2003; Pedersen 2010; Price 1997; Roux 2003; Storr 1986; Wasserman 2006). In the remaining 16 trials, treatment compliance was measured by self‐reporting and/or by more objective methods (counting the number of used drug blisters, checking the drug canister weight or using a dose counter). The compliance rate was higher than 75% in all but three trials for which these data were available (CAMP 2000; Guilbert 2006; Jonasson 2000).

1. Description of interventions: molecule, daily dose, inhalation device and treatment duration of ICS.

| Study | Molecule | Daily dose (μg/d) | Inhalation device | Treatment duration |

| Allen 1998 | Fluticasone | 100, twice daily 200, twice daily |

Diskhaler | 52 weeks |

| Becker 2006 | Beclomethasone | 400, twice daily | CFC‐MDI | 56 weeks |

| Bensch 2011 | Flunisolide | 400, twice daily | HFA‐MDI | 52 weeks |

| Bisgaard 2004 | Fluticasone | 200, twice daily | HFA‐MDI | 52 weeks |

| CAMP 2000 | Budesonide | 400, twice daily | Turbuhaler | 4‐6 years |

| Doull 1995 | Beclomethasone | 400, twice daily | Diskhaler | 7 months |

| Gillman 2002 | Flunisolide Beclomethasone |

400, twice daily 400, twice daily |

HFA‐MDI CFC‐MDI |

52 weeks |

| Gradman 2010 | Budesonide | 200, twice daily | DPI | 52 weeks |

| Guilbert 2006 | Fluticasone | 200, twice daily | CFC‐MDI | 2 years |

| Jonasson 2000 | Budesonide | 100, once daily 200, once daily 200, twice daily |

Turbuhaler | 27 months |

| Kannisto 2000 | Fluticasone Budesonide |

500, 2 months; 200, thereafter 800, 2 months; 400, thereafter |

Diskus Turbuhaler |

12 months |

| Martinez 2011 | Beclomethasone | 100, twice dailya | HFA‐DMI | 44 weeks |

| Pauwels 2003 | Budesonide | 200, once daily | Turbuhaler | 3 years |

| Pedersen 2010 | Ciclesonide | 50, once daily 100, once daily 200, once daily |

HFA‐MDI | 12 weeks |

| Price 1997 | Fluticasone | 100, twice daily | Diskhaler | 12 months |

| Roux 2003 | Fluticasone | 200, twice daily | Diskus | 2 years |

| Simons 1997 | Beclomethasone | 400, twice daily | Diskhaler | 12 months |

| Skoner 2008 | Ciclesonide | 50, once daily 200, once daily |

HFA‐MDI | 12 months |

| Skoner 2011 | Mometasone | 100, once daily 200, once daily 200, twice daily |

DPI | 52 weeks |

| Sorkness 2007 | Fluticasone | 200, twice daily | Diskus | 48 weeks |

| Storr 1986 | Beclomethasone | 300, 3 times a day | Jet nebuliser | 6 months |

| Tinkelman 1993 | Beclomethasone | 400, 4 times a day | CFC‐MDI | 52 weeks |

| Turpeinen 2008 | Budesonide | 800, twice daily, 1 month; then 400, twice daily, 5 months; 200, thereafterb |

Turbuhaler | 18 months |

| Verberne 1997 | Beclomethasone | 400, twice daily | Diskhaler | 54 weeks |

| Wasserman 2006 | Fluticasone | 100, twice daily 200, twice daily |

CFC‐MDI | 12 weeks |

Abbreviations:

CFC: chlorofluorocarbon.

DPI: dry powder inhaler.

HFA: hydrofluoroalkane.

ICS: inhaled corticosteroids.

MDI: metered‐dose inhaler.

aOnly‐daily beclomethasone group was used as the intervention group.

bOnly continuous budesonide group was used as the intervention group.

Co‐intervention with additional antiasthmatic drugs such as long‐acting beta2‐agonists, antileukotrienes or theophylline was allowed in seven trials (Allen 1998; Bensch 2011; CAMP 2000; Guilbert 2006; Simons 1997; Skoner 2011; Wasserman 2006).

Outcome measures

Fifteen trials (Allen 1998; Becker 2006; Bensch 2011; Bisgaard 2004; CAMP 2000; Gillman 2002; Guilbert 2006; Jonasson 2000; Pauwels 2003; Pedersen 2010; Price 1997; Roux 2003; Skoner 2008; Skoner 2011; Tinkelman 1993) used linear growth velocity as the outcome measure, alone or in combination with other growth measurements. Seventeen trials used change from baseline in absolute height over time as the outcome measure (Allen 1998; Becker 2006; Bensch 2011; Bisgaard 2004; Doull 1995; Gillman 2002; Gradman 2010; Guilbert 2006; Martinez 2011; Roux 2003; Simons 1997; Skoner 2008; Sorkness 2007; Storr 1986; Tinkelman 1993; Turpeinen 2008; Verberne 1997). Three trials (Kannisto 2000; Price 1997; Verberne 1997) used change in height SDS as the outcome measure.

Excluded studies

We excluded 13 studies from the review. The reasons for exclusion are summarised under Characteristics of excluded studies.

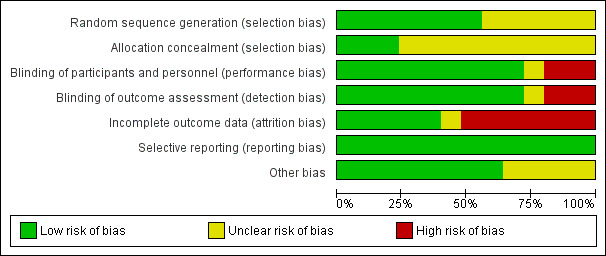

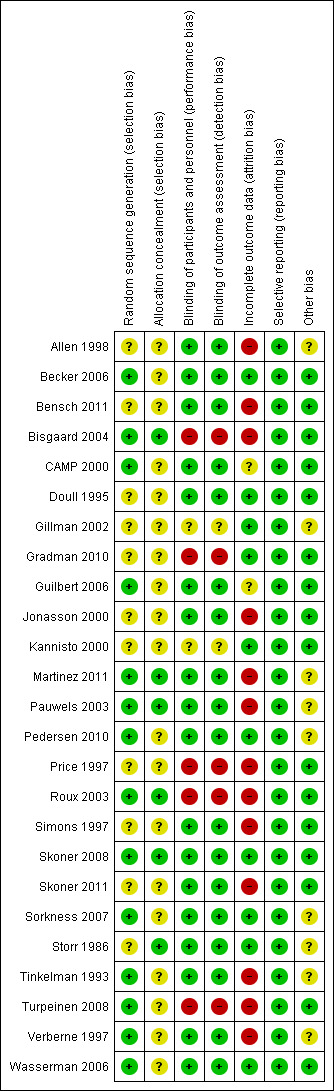

Risk of bias in included studies

Full details of the risk of bias for each trial can be found under Characteristics of included studies. A graphical summary of our 'Risk of bias' judgements can be found in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Fourteen trials used adequate methods of random sequence generation, and 11 trials did not provide details about allocation sequence generation. All but six trials (Bisgaard 2004; Martinez 2011; Pauwels 2003; Roux 2003; Skoner 2008; Storr 1986) failed to report the method of allocation concealment.

Blinding

Eighteen trials (72%) used placebo or non‐steroidal drugs that matched the appearance of ICS for blinding, five trials (Bisgaard 2004; Gradman 2010; Price 1997; Roux 2003; Turpeinen 2008) had an open‐label design and two trials (Gillman 2002; Kannisto 2000) did not report sufficient information to allow ascertainment of blinding.

Incomplete outcome data

All trials reported numbers of and reasons for withdrawals by group. The withdrawal rate was higher than 20% in 14 trials (Allen 1998; Bensch 2011; Bisgaard 2004; Jonasson 2000; Martinez 2011; Pauwels 2003; Pedersen 2010; Price 1997; Roux 2003; Simons 1997; Skoner 2011; Tinkelman 1993; Turpeinen 2008; Verberne 1997). In nine trials, the control group had a higher withdrawal rate than the ICS group, mainly as the result of poor asthma control.

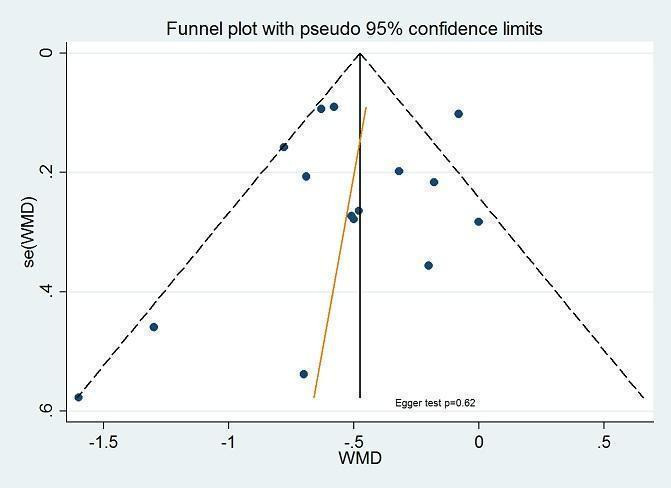

Selective reporting

Twenty‐five trials reported all outcomes mentioned in the methods section with no apparent bias. The funnel plots (Figure 4) showed slight asymmetry on visual inspection, but Egger's test did not show statistically significant small‐study effects, suggesting no publication bias.

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: inhaled corticosteroids vs placebo or non‐steroidal drugs: 1‐year (or nearly 1‐year) treatment, outcome: linear growth velocity (cm/y). Funnel plot with Egger's test for small‐study effects conducted in Stata.

Other potential sources of bias

Nine trials (Allen 1998; Gillman 2002; Martinez 2011; Pauwels 2003; Pedersen 2010; Sorkness 2007; Storr 1986; Tinkelman 1993; Verberne 1997) did not report the method used for height measurement. No other potential sources of bias were observed in the included trials.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Three‐ to five‐month treatment

Linear growth velocity (mm/wk)

One 12‐week trial including 904 participants (Pedersen 2010) did not show a statistically significant difference in mean linear growth velocity between the ciclesonide 50, 100 and 200 μg/d and placebo groups (mean ± SE, 0.82 ± 0.16, 0.97 ± 0.10, 0.95 ± 0.12 and 0.96 ± 0.18, P value > 0.05; data extracted from the figure).

Change from baseline in height (cm)

One 12‐week trial including 332 participants (Wasserman 2006) showed that mean change from baseline in height (cm) was similar between the CFC‐fluticasone 100 μg/d and placebo groups (MD 0.055 cm, 95% CI, ‐0.275 to 0.386, P value 0.74) and between the CFC‐fluticasone 200 μg/d and placebo groups (MD ‐0.012 cm, 95% CI, ‐0.347 to 0.324, P value 0.95). Eleven trials including 3332 participants with treatment duration longer than or equal to six months reported mean change from baseline in height or mean height in each treatment group at the three‐ to five‐month time point; however, all 11 trials used figures to present the means but not uncertainty of measurement (SD, SE or 95% CI). In five trials (Bensch 2011; Bisgaard 2004; CAMP 2000; Gradman 2010; Skoner 2008), the authors explicitly stated that no statistically significant difference in mean increase in height was observed during the first three months of treatment between ICS and control groups. In another five trials (Allen 1998; Becker 2006; Doull 1995; Martinez 2011; Skoner 2011), the MD between ICS and control groups in change from baseline in height (data extracted from the figures) during the first three months of treatment was 0 cm, ‐0.1 cm, ‐0.4 cm, ‐0.18 cm and ‐0.04 cm, respectively. Only one trial (Simons 1997) reported that effect of beclomethasone 400 μg/d on height appeared to be greatest during months one through three, with an MD of 1.3 cm in height increase between beclomethasone and placebo groups.

Change in height SDS

None of the trials reported this outcome.

Change in height z‐score

None of the trials reported this outcome.

Six‐ to eight‐month treatment

Linear growth velocity (cm/y)

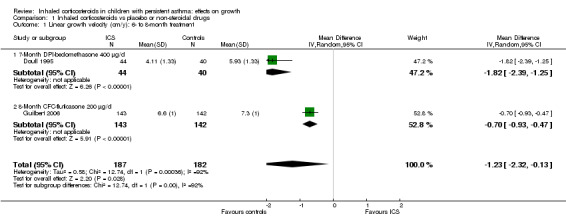

Two trials including 369 participants (Doull 1995; Guilbert 2006) showed that seven‐ and eight‐month treatment with ICS was associated with decreased linear growth velocity compared with placebo, with a pooled MD of ‐1.23 cm/y (95% CI ‐2.32 to ‐0.13, P value 0.03, I2 = 92%) (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Inhaled corticosteroids vs placebo or non‐steroidal drugs, Outcome 1 Linear growth velocity (cm/y): 6‐ to 8‐month treatment.

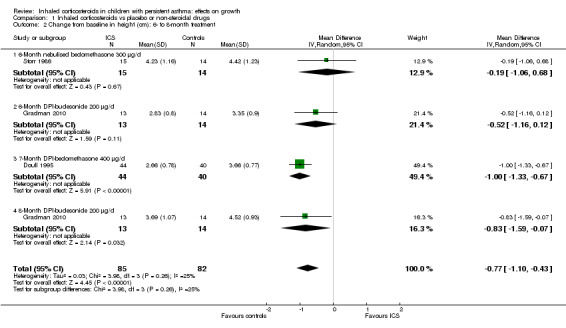

Change from baseline in height (cm)

Three trials including 167 participants (Doull 1995; Gradman 2010; Storr 1986) provided data on the increase in height at the six‐ to eight‐month time point. Pooled results of three trials showed a statistically significant difference in mean change from baseline in height between ICS and control groups (MD ‐0.77 cm, 95% CI ‐1.10 to ‐0.43, P value < 0.00001, I2 = 24%) (Analysis 1.2). Nine trials with treatment duration longer than eight months presented partial data on the increase in height at the six‐ to eight‐month time point as the figures could not be pooled because of lack of SD. In two trials (Guilbert 2006; Simons 1997), the authors explicitly stated that a statistically significant suppressive effect of ICS on height increase was observed. In the remaining seven trials (Allen 1998; Becker 2006; Bensch 2011; Bisgaard 2004; Martinez 2011; Skoner 2008; Skoner 2011) in which growth data were extracted from the figures, the MD between ICS and control groups in change from baseline in height was ‐0.11 cm, ‐0.52 cm, ‐0.20 cm, ‐0.33 cm, ‐0.51 cm, ‐0.22 cm and ‐0.54 cm, respectively.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Inhaled corticosteroids vs placebo or non‐steroidal drugs, Outcome 2 Change from baseline in height (cm): 6‐ to 8‐month treatment.

Change in height SDS

None of the trials reported this outcome.

Change in height z‐score

None of the trials reported this outcome.

One‐year (or nearly one‐year) treatment

Linear growth velocity (cm/y)

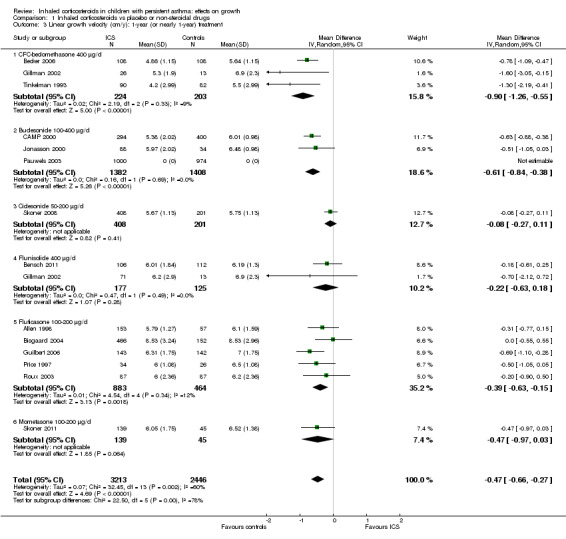

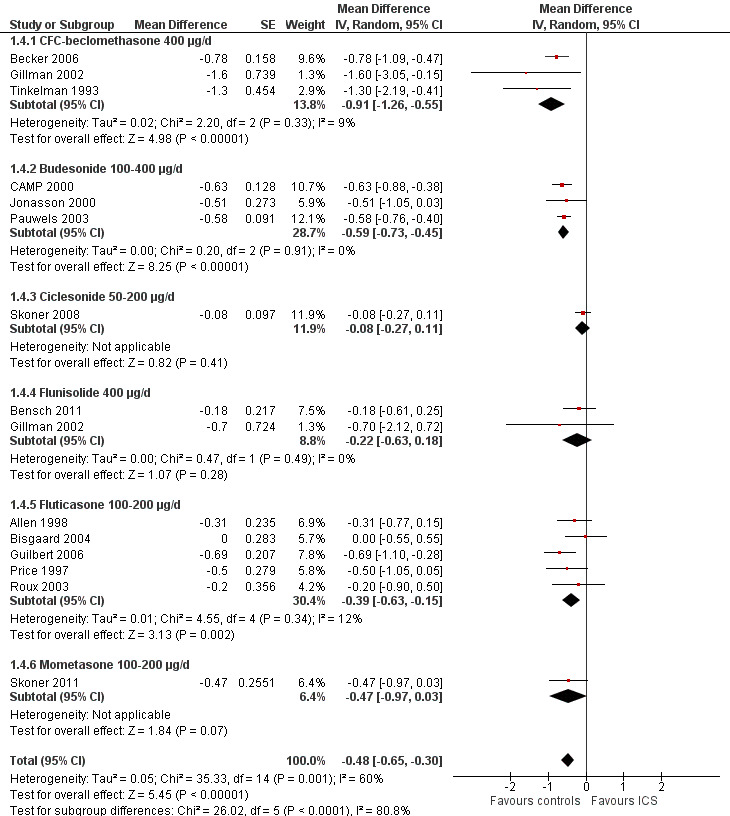

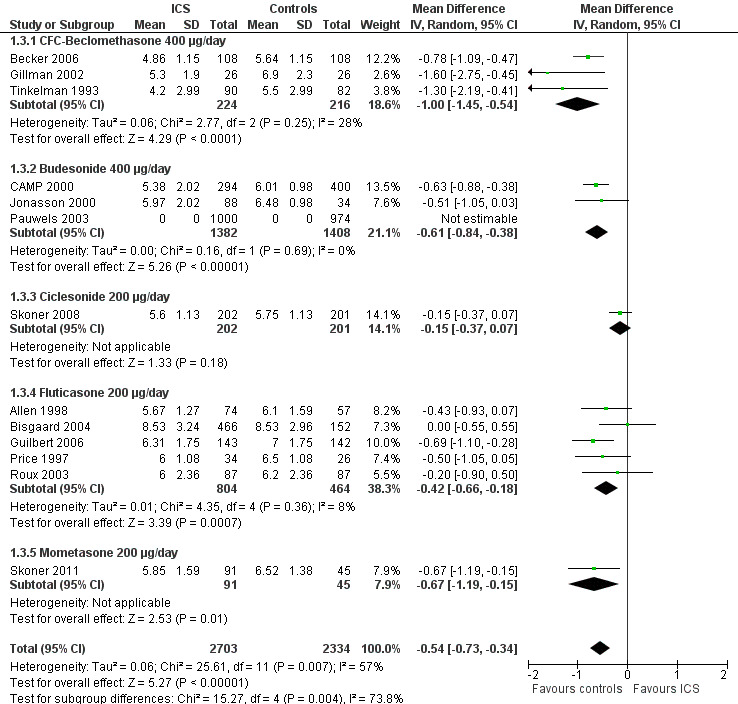

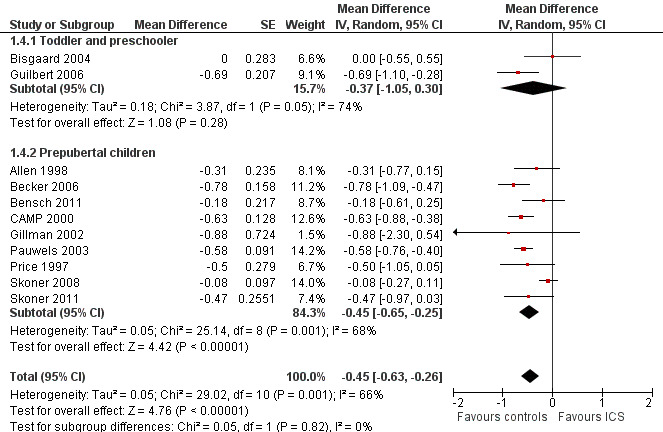

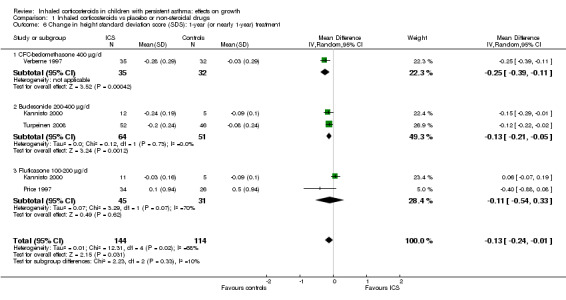

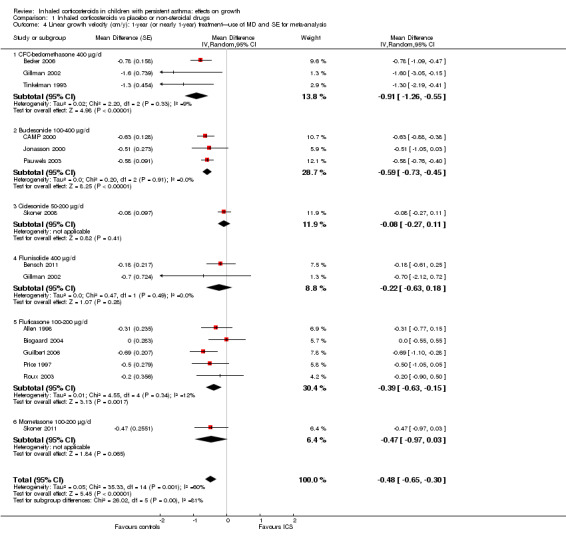

Thirteen trials with 14 comparisons (Allen 1998; Becker 2006; Bensch 2011; Bisgaard 2004; CAMP 2000; Gillman 2002; Guilbert 2006; Jonasson 2000; Price 1997; Roux 2003; Skoner 2008; Skoner 2011; Tinkelman 1993) among 3743 participants provided data on mean linear growth velocity in each treatment group. Meta‐analysis of these 13 trials showed that participants treated with ICS had a statistically significant reduction in linear growth velocity compared with the control group, with an MD of ‐0.47 cm/y (95% CI ‐0.66 to ‐0.27, P value < 0.00001) (Analysis 1.3). Significant heterogeneity in results was noted between studies (I2 = 60%). One trial (Pauwels 2003) provided MD and 95% CI of linear growth velocity between corticosteroid and placebo groups among 1974 prepubertal children. We included this trial in the meta‐analysis using MD and SE of linear growth velocity, and the results remained almost unchanged (14 trials with 15 comparisons among 5717 participants; MD ‐0.48 cm/y, 95% CI ‐0.65 to ‐0.30, P value < 0.0001) (Figure 5).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Inhaled corticosteroids vs placebo or non‐steroidal drugs, Outcome 3 Linear growth velocity (cm/y): 1‐year (or nearly 1‐year) treatment.

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1: inhaled corticosteroids versus placebo or non‐steroidal drugs, outcome: 1.4: linear growth velocity (cm/y): 1‐year (or nearly 1‐year) treatment—use of MD and SE for meta‐analysis.

The subgroup analysis on molecules showed a statistically significant difference between six ICS regarding effects on linear growth velocity during a one‐year treatment period (Chi² = 26.1, df = 5, P value < 0.0001) (Figure 5). In a post hoc analysis in which only trials using doses equivalent to 200 μg/d HFA‐beclomethasone were selected, the group difference in suppressive effect on linear growth velocity was also statistically significant (Chi² = 15.3, df = 4, P value 0.004) (Figure 6).

6.

Post hoc subgroup analysis on molecule selecting trials using similar dose equivalence of 200 μg/d HFA‐beclomethasone: linear growth velocity (cm/y) during 1‐year treatment.

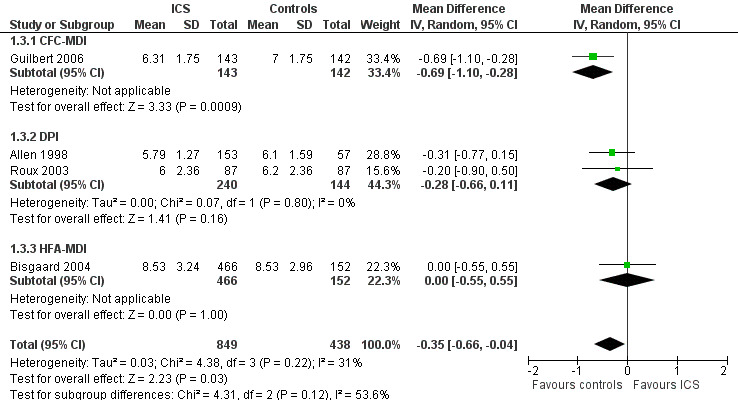

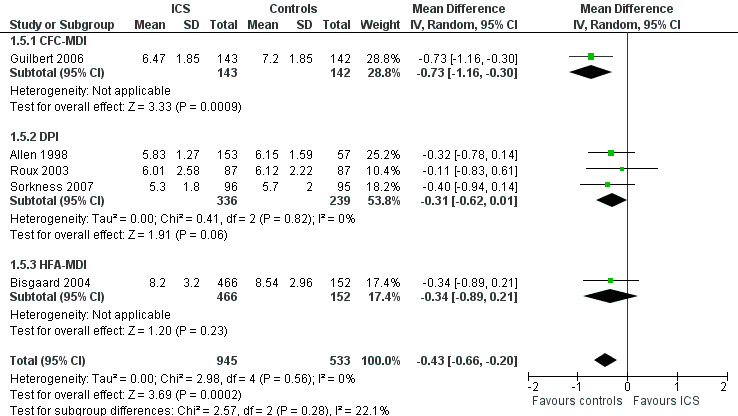

A post hoc subgroup analysis for inhalation devices within the molecule fluticasone propionate 200 μg/d did not show a statistically significant difference between CFC‐MDI, DPI and HFA‐MDI (Chi² = 4.31, df = 2, P value 0.12) regarding the effects of ICS on linear growth velocity during a one‐year treatment period (Figure 7).

7.

Post hoc subgroup analysis for inhalation device within the molecule fluticasone propionate 200 μg/d: linear growth velocity (cm/y) during 1‐year treatment.

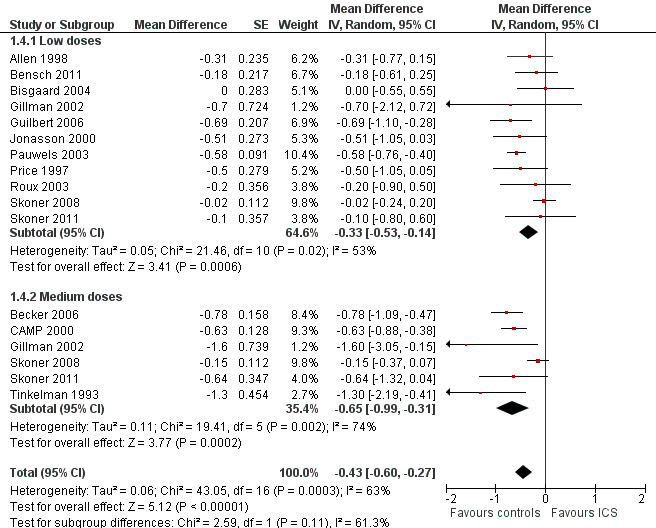

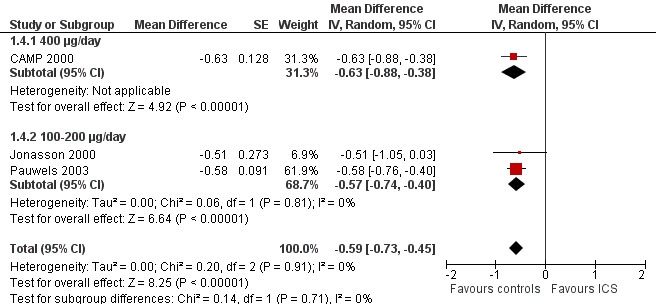

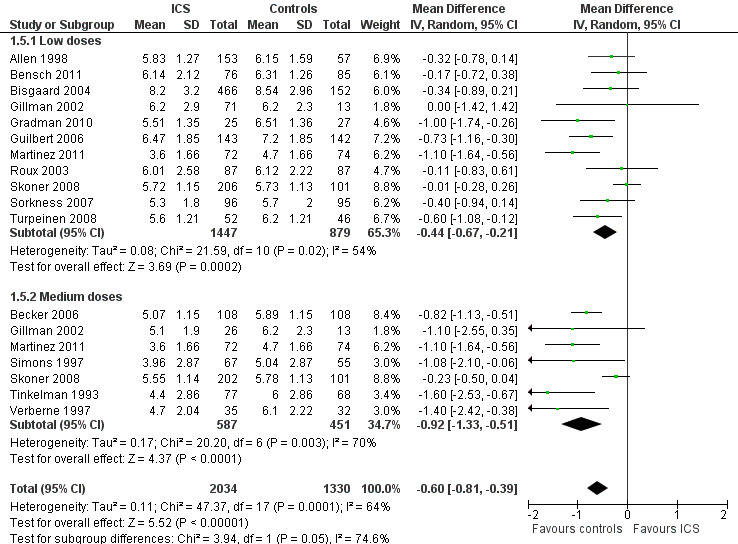

The subgroup analysis on daily ICS dose did not show a statistically significant difference in mean reduction of linear growth velocity during one‐year treatment between low and medium doses (Chi² = 2.59, df = 1, P value 0.11) (Figure 8). The post hoc subgroup analysis within the molecule budesonide also did not show a statistically significant difference between 100 to 200 μg/d and 400 μg/d in terms of suppressive effects on linear growth velocity (Figure 9).

8.

Post hoc subgroup analysis on the ICS dose: linear growth velocity (cm/y) during 1‐year treatment.

9.

Post hoc subgroup analysis on ICS doses within the molecule budesonide: linear growth velocity (cm/y) during 1‐year treatment.

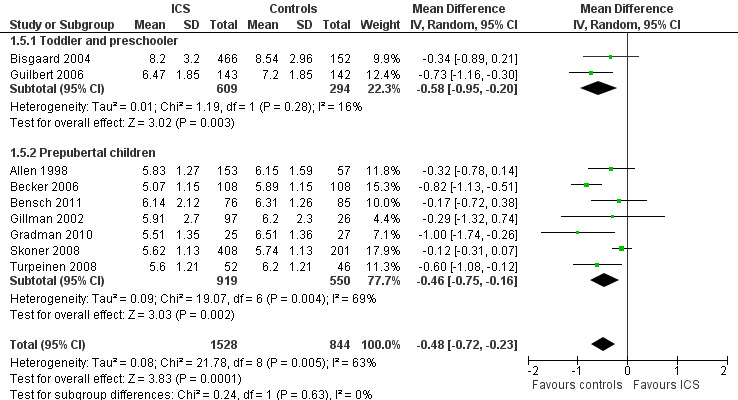

No impact of age group on magnitude of effect was apparent (Chi² = 0.05, df = 1, P value 0.82), that is, between toddlers and preschoolers and prepubertal children (Figure 10). The post hoc group analysis within the molecule fluticasone propionate 200 μg/d yielded similar results (toddlers and preschoolers: Bisgaard 2004; Guilbert 2006, MD ‐0.37 cm/y, 95% CI ‐1.05 to 0.30; prepubertal children: Allen 1998, MD ‐0.31 cm/y, 95% CI ‐0.77 to 0.15) (Chi² = 0.02, df = 1, P value 0.88).

10.

Post hoc subgroup analysis on participant age: linear growth velocity (cm/y) during 1‐year treatment.

Ten sensitivity analyses were conducted to explore potential effect modifiers; these analyses did not substantially change the results (Table 3).

2. Results of sensitivity analyses: effect of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) on linear growth velocity in the first year of treatment.

| Analyses (no. of trials) | Exclusion of trials (reasons) | Exclusion of trials (studies) | Effect size (MD, 95% confidence interval (CI)) |

| Overall analysis (n = 14) |

‐0.48 cm/y (‐0.65 to ‐0.30) | ||

| Sensitivity analysis 1 | Open‐label trials | Bisgaard 2004; Price 1997; Roux 2003 | ‐0.52 cm/y (‐0.71 to ‐0.33) |

| Sensitivity analysis 2 | Random sequence generation not reported |

Allen 1998; Bensch 2011; Gillman 2002; Jonasson 2000; Skoner 2011 |

‐0.48 cm/y (‐0.74 to ‐0.22) |

| Sensitivity analysis 3 | Imputation of missing standard deviation (SD) | CAMP 2000; Gillman 2002 | ‐0.44 cm/y (‐0.62 to ‐0.25) |

| Sensitivity analysis 4 | Treatment compliance rate < 75% or no data available |

CAMP 2000; Gillman 2002; Guilbert 2006; Jonasson 2000; Pauwels 2003; Roux 2003 |

‐0.39 cm/y (‐0.65 to ‐0.13) |

| Sensitivity analysis 5 | Withdrawal rate > 20% |

Allen 1998; Bensch 2011; Bisgaard 2004; Pauwels 2003; Roux 2003; Skoner 2011; Tinkelman 1993 |

‐0.48 cm/y (‐0.71 to ‐0.25) |

| Sensitivity analysis 6 | Non‐steroidal drugs rather than placebo used as controls |

Bisgaard 2004; Gillman 2002; Roux 2003; Tinkelman 1993 |

‐0.47 cm/y (‐0.65 to ‐0.29) |

| Sensitivity analysis 7 | Trials included participants receiving previous ICS for longer than 1 month |

Allen 1998; Bensch 2011; Bisgaard 2004; CAMP 2000; Gillman 2002; Guilbert 2006; Skoner 2008 |

‐0.61 cm/y (‐0.74 to ‐0.48) |

| Sensitivity analysis 8 | Trial in which only a subset of data was analysed |

Allen 1998 | ‐0.49 cm/y (‐0.67 to ‐0.31) |

| Sensitivity analysis 9 | Growth data extracted from the figures |

CAMP 2000; Guilbert 2006; Skoner 2011 | ‐0.44 cm/y (‐0.65 to ‐0.23) |

| Sensitivity analysis 10 | Trials sponsored by pharmaceutical industry |

Allen 1998; Becker 2006; Bensch 2011; Bisgaard 2004; Gillman 2002; Pauwels 2003; Price 1997; Roux 2003; Skoner 2008; Skoner 2011; Tinkelman 1993 |

‐0.63 cm/y (‐0.83 to ‐0.43) |

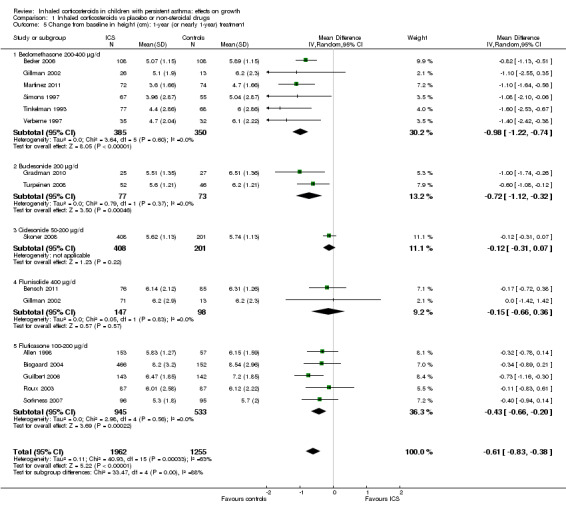

Change from baseline in height (cm)

Fifteen trials including 16 comparisons among 3314 participants (Allen 1998; Becker 2006; Bensch 2011; Bisgaard 2004; Gillman 2002; Gradman 2010; Guilbert 2006; Martinez 2011; Roux 2003; Simons 1997; Skoner 2008; Sorkness 2007; Tinkelman 1993; Turpeinen 2008; Verberne 1997) provided data on mean change from baseline in height over a one‐year (nearly one‐year) treatment period in each treatment group. Meta‐analysis of 15 trials showed that participants treated with ICS had a statistically significantly lower mean increase in height compared with the control group, with an MD of ‐0.61 cm (95% CI ‐0.83 to ‐0.38, P value < 0.00001) (Analysis 1.5). Significant heterogeneity in results was noted between studies (I2 = 63%).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Inhaled corticosteroids vs placebo or non‐steroidal drugs, Outcome 5 Change from baseline in height (cm): 1‐year (or nearly 1‐year) treatment.

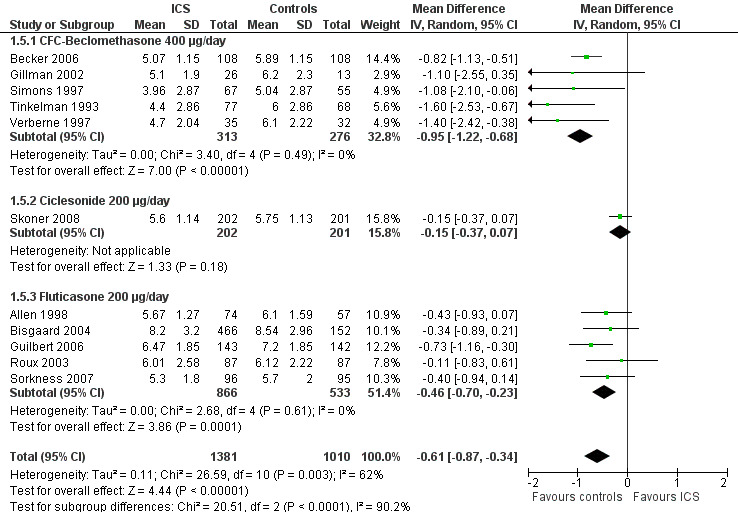

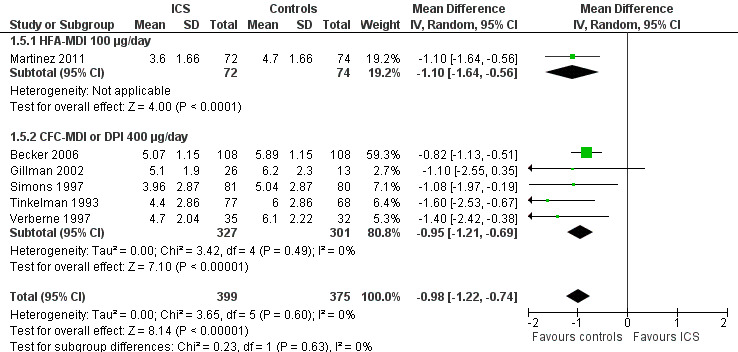

The subgroup analysis on molecules yielded results similar to those obtained for linear growth velocity (Analysis 1.5). In a post hoc subgroup analysis of data from trials using doses equivalent to 200 μg/d of HFA‐beclomethasone, the difference in suppressive effect on the increase in height during one‐year treatment was also statistically significant between beclomethasone, ciclesonide and fluticasone propionate (Chi² = 20.5, df = 2, P value < 0.0001) (Figure 11).

11.

Post hoc subgroup analysis on molecule selecting trials using doses equivalent to 200 μg/d HFA‐beclomethasone: change from baseline in height (cm) during 1‐year treatment.

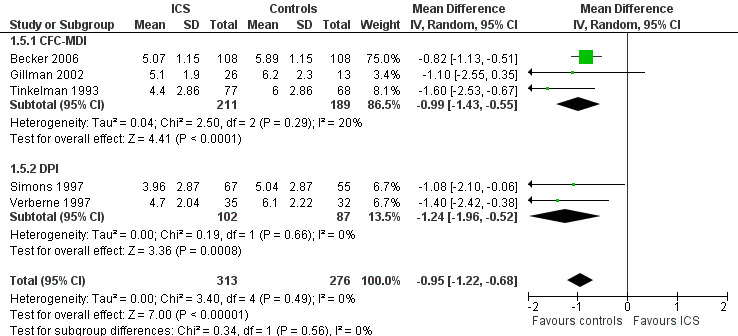

The post hoc subgroup analysis on devices within the molecule beclomethasone (dose equivalence of CFC formulation 400 μg/d) did not find a statistically significant difference between CFC‐MDI and DPI regarding the magnitude of effect of ICS on increase in height (Chi² = 0.34, df = 2, P value 0.56) (Figure 12). Another post hoc subgroup analysis within the molecule fluticasone propionate 200 μg/d also did not find a statistically significant impact of device (CFC‐MDI, DPI or HFA‐MDI) on growth‐suppressive effect of ICS (Chi² = 2.57, df = 2, P value 0.28) (Figure 13).

12.

Post hoc subgroup analysis on device within the molecule beclomethasone (dose equivalence of CFC‐formulation 400 μg/d): change from baseline in height (cm) during 1‐year treatment.

13.

Post hoc subgroup analysis on device within the molecule fluticasone propionate 200 μg/d: change from baseline in height (cm) during 1‐year treatment.

The subgroup analysis on daily ICS dose showed that medium doses produced a statistically significantly greater reduction in mean change from baseline in height compared with low doses (Chi² = 3.94, df = 1, P value 0.05) (Figure 14). However, a post hoc subgroup analysis within the molecule beclomethasone did not show a statistically significant difference between low and medium doses in terms of growth‐suppressive effect (Chi² = 0.23, df = 1, P value 0.63) (Figure 15).

14.

Post hoc subgroup analysis on ICS dose: change from baseline in height (cm) during 1‐year treatment.

15.

Post hoc subgroup analysis on ICS dose within the molecule beclomethasone: change from baseline in height (cm) during 1‐year treatment.

Finally, no statistically significant impact of age group on the effect of ICS was noted, that is, between toddlers and preschoolers and prepubertal children (Chi² = 0.24, df = 2, P value 0.63) (Figure 16).

16.

Post hoc subgroup analysis on participant age: change from baseline in height (cm) during 1‐year treatment.

Sensitivity analyses yielded similar results to those obtained for linear growth velocity (Table 4).

3. Results of sensitivity analyses: effect of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) on change from baseline in height in first year of treatment.

| Analyses (no. of trials) | Exclusion of trials (reasons) | Exclusion of trials (studies) | Effect size (mean difference (MD), 95% confidence interval (CI)) |

| Overall analysis (n = 15) | ‐0.61 cm/y (‐0.83 to ‐0.38) | ||

| Sensitivity analysis 1 | Open‐label trials |

Bisgaard 2004; Gradman 2010; Roux 2003; Turpeinen 2008 |

‐0.65 cm/y (‐0.94 to ‐0.37) |

| Sensitivity analysis 2 | Random sequence generation not reported |

Allen 1998; Bensch 2011; Gillman 2002; Gradman 2010; Simons 1997 |

‐0.64 cm/y (‐0.94 to ‐0.35) |

| Sensitivity analysis 3 | Imputation of missing standard deviation (SD) | Becker 2006; Gillman 2002 | ‐0.59 cm/y (‐0.83 to ‐0.34) |

| Sensitivity analysis 4 | Treatment compliance rate < 75% or no data available |

Gillman 2002; Guilbert 2006; Roux 2003 | ‐0.64 cm/y (‐0.90 to ‐0.38) |

| Sensitivity analysis 5 | Withdrawal rate > 20% |

Allen 1998; Bensch 2011; Bisgaard 2004; Martinez 2011; Roux 2003; Simons 1997 |

‐0.70 cm/y (‐1.02 to ‐0.38) |

| Sensitivity analysis 6 | Non‐steroidal drugs rather than placebo used as controls |

Bisgaard 2004; Gillman 2002; Gradman 2010; Roux 2003; Tinkelman 1993; Turpeinen 2008; Verberne 1997 |

‐0.55 cm/y (‐0.84 to ‐0.26) |

| Sensitivity analysis 7 | Trials that included participants receiving previous regular use of ICS for longer than 1 month before study entry |

Allen 1998; Bensch 2011; Bisgaard 2004; Gillman 2002; Gradman 2010; Guilbert 2006; Martinez 2011; Skoner 2008; Sorkness 2007; Turpeinen 2008; Verberne 1997 |

‐0.83 cm/y (‐1.35 to ‐0.32) |

| Sensitivity analysis 8 | Growth data extracted from the figures |

Becker 2006; Bisgaard 2004; Guilbert 2006; Martinez 2011; Skoner 2008 |

‐0.60 cm/y (‐0.87 to ‐0.33) |

| Sensitivity analysis 9 | 18‐Month trial in which the growth data used for the analysis were obtained between 7 and 18 months when ICS was given at a constant dose |

Turpeinen 2008 | ‐0.61 cm/y (‐0.85 to ‐0.37) |

| Sensitivity analysis 10 | Trial in which only a subset of data was analysed |

Allen 1998 | ‐0.64 cm/y (‐0.88 to ‐0.39) |

| Sensitivity analysis 11 | Trials sponsored by pharmaceutical industry |

Allen 1998; Becker 2006; Bensch 2011; Bisgaard 2004; Gillman 2002; Roux 2003; Simons 1997; Skoner 2008; Tinkelman 1993; Turpeinen 2008; Verberne 1997 |

‐0.78 cm/y (‐1.08 to ‐0.48) |

Change in height SDS

Four trials including 258 participants (Kannisto 2000; Price 1997; Turpeinen 2008; Verberne 1997) provided mean change in height SDS and uncertainty of measurement in each treatment group. Meta‐analysis of four trials showed that participants treated with ICS had a statistically significantly lower mean change in height SDS compared with those treated with placebo, with an MD of ‐0.13 (95% CI ‐0.24 to ‐0.01, P value 0.03) (Analysis 1.6). Significant heterogeneity in results was noted between studies (I2 = 68%).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Inhaled corticosteroids vs placebo or non‐steroidal drugs, Outcome 6 Change in height standard deviation score (SDS): 1‐year (or nearly 1‐year) treatment.

Change in height z‐score

None of the trials reported this outcome.

Two‐year treatment

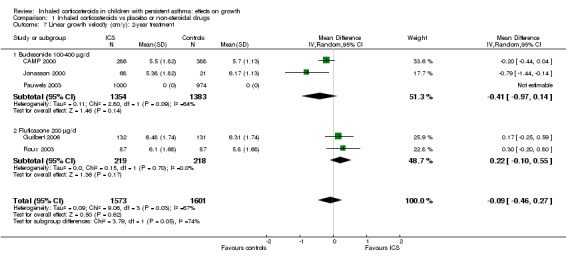

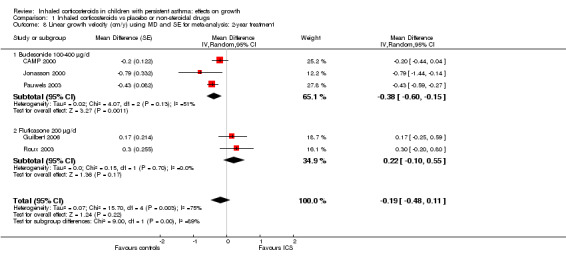

Linear growth velocity (cm/y)

Five trials including 3174 participants (CAMP 2000; Guilbert 2006; Jonasson 2000; Pauwels 2003; Roux 2003) provided data on linear growth velocity in the second year of treatment. Meta‐analysis of five trials showed no statistically significant differences in linear growth velocity between ICS and control groups (MD ‐0.19 cm/y, 95% CI ‐0.48 to 0.11, P value 0.22, I2 = 75%) (Analysis 1.7; Analysis 1.8). In contrast, meta‐analysis of these five trials showed that participants treated with ICS had a statistically significant reduction in linear growth velocity in the first year of treatment compared with the control group, with an MD of ‐0.58 cm/y (95% CI ‐0.71 to ‐0.44, P value < 0.00001). Meta‐analysis of three trials (Jonasson 2000; Pauwels 2003; Roux 2003) consisting of ICS‐naïve participants yielded similar results regarding effects of ICS‐induced suppression on linear growth velocity in the first year of treatment (MD ‐0.55 cm/y, 95% CI ‐0.72 to ‐0.39, P value < 0.00001).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Inhaled corticosteroids vs placebo or non‐steroidal drugs, Outcome 7 Linear growth velocity (cm/y): 2‐year treatment.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Inhaled corticosteroids vs placebo or non‐steroidal drugs, Outcome 8 Linear growth velocity (cm/y) using MD and SE for meta‐analysis: 2‐year treatment.

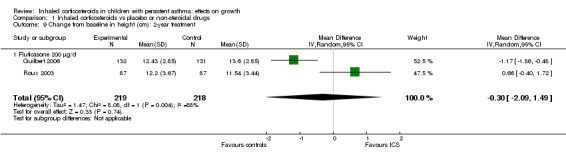

Change from baseline in height (cm)

Two trials including 437 participants (Guilbert 2006; Roux 2003) provided data on mean change from baseline in height over two years of treatment. Meta‐analysis of two trials showed no statistically significant differences in the mean increase in height between ICS and control groups (MD ‐0.30 cm, 95% CI ‐2.09 to 1.49, P value 0.74) (Analysis 1.9).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Inhaled corticosteroids vs placebo or non‐steroidal drugs, Outcome 9 Change from baseline in height (cm): 2‐year treatment.

Change in height SDS

None of the trials reported this outcome.

Change in height z‐score

None of the trials reported this outcome.

Three‐year treatment

Linear growth velocity (cm/y)

Two trials (CAMP 2000; Pauwels 2003) presented the results of linear growth velocity in the third year of treatment, but the data were not suitable for meta‐analysis. In the trial of CAMP 2000, mean linear growth velocity was 5.34 cm/y (data extracted from the figure) in both budesonide (n = 288) and placebo groups (n = 379). The trial of Pauwels 2003 including 1974 prepubertal children reported lower linear growth velocity in the budesonide group during the third year of treatment compared with the placebo group (MD ‐0.33 cm/y, 95% CI ‐0.52 to ‐0.14, P value 0.0005), but the difference was less than that seen in the first year of treatment (MD ‐0.58 cm/y, 95% CI ‐0.76 to ‐0.40, P value < 0.0001).

Change from baseline in height (cm)

The trial of CAMP 2000 reported that, at the end of treatment with a mean duration of 4,3 years, the mean increase in height in the budesonide group was 1.1 cm less than the mean increase in the placebo group (22.7 vs 23.8 cm, P value 0.005).

Change in height SDS

None of the trials reported this outcome.

Change in height z‐score

None of the trials reported this outcome.

Off‐treatment follow‐up (two‐ to four‐month)

Linear growth velocity (cm/y)

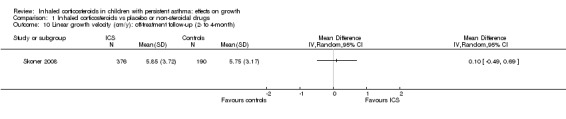

Two trials (Skoner 2008; Skoner 2011) reported the results of linear growth velocity during two‐ and three‐month off‐treatment follow‐up periods, but the data were not suitable for meta‐analysis. The trial of Skoner 2008, which included 566 participants, showed similar linear growth velocity during two‐month follow‐up between ciclesonide 40 μg/d and 160 μg/d and placebo, with mean values (SE) of 6.06 cm/y (0.3), 5.64 cm/y (0.24) and 5.75 cm/y (0.23), respectively. We combined the data from two ciclesonide groups and found no statistically significant difference in linear growth velocity between the ciclesonide and control groups (MD 0.10 cm/y, 95% CI ‐0.49 to 0.69, P value 0.74) (Analysis 1.10). The trial of Skoner 2011 showed lower linear growth velocity during three‐month follow‐up in the mometasone 200 μg once daily group (n = 34) compared with the placebo group (n = 30) (MD ‐2.42 cm/y, SE 1.18, P value 0.05), but no statistically significant difference in linear growth velocity was found between groups given mometasone 100 μg/d once daily (n = 40), 100 μg/d twice daily (n = 36) and placebo (n = 30).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Inhaled corticosteroids vs placebo or non‐steroidal drugs, Outcome 10 Linear growth velocity (cm/y): off‐treatment follow‐up (2‐ to 4‐month).

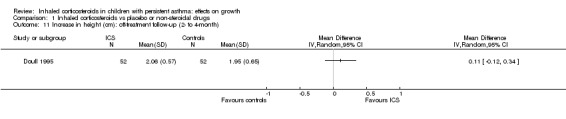

Increase in height (cm)

One trial (Doull 1995) including 104 participants found no statistically significant difference between beclomethasone and placebo groups in the mean increase in height during a four‐month off‐treatment follow‐up period (MD 0.11 cm/y, 95% CI ‐0.12 to 0.34, P value 0.36) (Analysis 1.11)

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Inhaled corticosteroids vs placebo or non‐steroidal drugs, Outcome 11 Increase in height (cm): off‐treatment follow‐up (2‐ to 4‐month).

Change in height SDS

None of the trials reported this outcome.

Change in height z‐score

None of the trials reported this outcome.

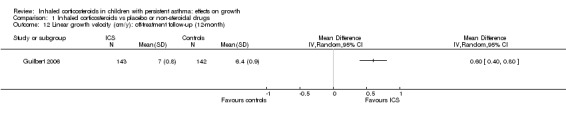

Off‐treatment follow‐up (12‐month)

Linear growth velocity (cm/y)

One trial (Guilbert 2006) including 285 participants showed greater linear growth velocity in the fluticasone propionate group compared with the placebo group during a 12‐month off‐treatment follow‐up period (MD 0.60 cm/y, 95% CI 0.40 to 0.80, P value < 0.00001) (Analysis 1.12).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Inhaled corticosteroids vs placebo or non‐steroidal drugs, Outcome 12 Linear growth velocity (cm/y): off‐treatment follow‐up (12‐month).

Increase in height (cm)

None of the trials reported this outcome.

Change in height SDS

None of the trials reported this outcome.

Change in height z‐score

None of the trials reported this outcome.

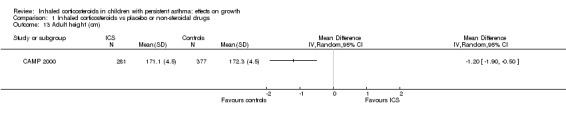

Off‐treatment follow‐up (adulthood)

Adult height (cm)

Kelly 2012 reported the results of long‐term follow‐up of 658 participants in the CAMP 2000 trial, showing that participants treated with budesonide 400 μg/d for a mean duration of 4.3 years at a prepubertal age had a mean reduction of 1.20 cm (95% CI ‐1.90 to ‐0.50, P value 0.001) in adult height compared with those treated with placebo (Analysis 1.13).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Inhaled corticosteroids vs placebo or non‐steroidal drugs, Outcome 13 Adult height (cm).

Discussion

This systematic review showed that regular use of ICS at low or medium daily doses was associated with statistically significant growth suppression measured by linear growth velocity, change from baseline in height and change in height SDS during a one‐year treatment period in children with mild to moderate persistent asthma. The subgroup analysis indicated that the effect size of ICS on linear growth velocity appeared to be associated more strongly with the ICS molecule than with the device or dose. ICS‐induced growth suppression seemed to be maximal during the first year of therapy and less pronounced during subsequent years of treatment.

In contrast to the effect on lower leg growth velocity measured by knemometry, which was observed within a few weeks after treatment (Wolthers 1993; Wolthers 1997), a detectable suppressive effect of ICS on the patient's statural height may occur months later. This review did not find an overall effect of ICS during the first three months of treatment. A statistically significant suppressive effect of ICS on both linear growth velocity and change from baseline in height was observed during a six‐ to eight‐month treatment period. Although lower leg length measured by knemometry is more sensitive in detecting ICS‐induced suppressive effects on growth, this measurement correlates poorly with statural height and tends to overestimate potential effects of ICS on growth (Allen 1999; Efthimiou 1998).

Most growth trials were of one‐year duration, and 15 trials showed a consistent overall suppressive effect of about 0.5 cm. The meaningful effect was unaffected by 11 sensitivity analyses underlying the robustness of findings. However, extrapolation of findings of one‐year growth studies to subsequent years has been questioned because growth‐suppressive effects of ICS appear to be time dependent (CAMP 2000; Guilbert 2006; Karlberg 1993; Pauwels 2003; Pedersen 2001). Five trials (CAMP 2000; Guilbert 2006; Jonasson 2000; Pauwels 2003; Roux 2003) included treatment periods longer than one year. In data from these five trials, we explored the growth‐suppressive effects of ICS after the first year of treatment; no statistically significant difference or a smaller difference in linear growth velocity than that observed during the first year of treatment was found between participants given ICS and controls during the second and third years of treatment. It remains unclear why ICS‐induced growth suppression in asthmatic children is less pronounced during subsequent years of treatment than during the first year of treatment.

This review included four trials that provided data on linear growth after treatment cessation for periods ranging from two to 12 months. Three trials did not find statistically significant catch‐up growth two to four months after treatment with ICS (beclomethasone, ciclesonide or mometasone) was stopped. One trial showed accelerated linear growth velocity in the fluticasone group compared with the placebo group 12 months after treatment cessation, but there remained a statistically significant difference of 0.7 cm in height between the fluticasone and placebo groups at the end of the three‐year trial. The relationship between prepubescent growth suppression as estimated by one‐year trials and final adult height also remains to be better defined. Long‐term follow‐up of participants in the CAMP 2000 trials showed that those treated with budesonide 400 μg/d for a mean duration of 4.3 years during prepubertal age had a mean reduction of 1.20 cm (95% CI ‐1.90 to ‐0.50) in adult height compared with those treated with placebo. This is the largest randomised prospective study conducted so far to investigate the potential impact of ICS‐induced growth suppression on adult height in prepubertal children with asthma. In contrast, another long‐term prospective follow‐up study of participants in a randomised trial showed that children with asthma who had received long‐term treatment with budesonide attained normal adult height (Agertoft 2000). However, caution should be taken in interpreting the findings of this study because only 47% (142/300) of participants in the budesonide group and 56% (18/32) of those in the control group contributed data for the analysis.