Abstract

Objective:

To evaluate associations between spousal caregiving and mental and physical health among older adults in Mexico.

Methods:

Data come from the Mexican Health & Aging Study, a national population-based study of adults ≥ 50 years and their spouses (2001 – 2015). We compared outcomes of spousal caregivers to those whose spouses had at least one basic or instrumental activity of daily living (I/ADL) but were not providing care; the control group conventionally includes all married respondents regardless of spouse’s need for care. We used targeted maximum likelihood estimation to evaluate the associations with past-week depressive symptoms, lower-body functional limitations, and chronic health conditions.

Results:

At baseline, 846 women and 629 men had a spouse with ≥ 1 I/ADL. Of these, 60.9% of women and 52.6% of men were spousal caregivers. Spousal caregiving was associated with more past-week depressive symptoms for men (Marginal Risk Difference (RD): 0.27, 95% CI: 0.03, 0.51) and women (RD: 0.15, 95% CI: 0.07, 0.23). We could not draw conclusions about associations with lower-body functional limitations and chronic health conditions. On average, all respondents whose spouses had caregiving needs had poorer health than the overall sample.

Conclusion:

We found evidence of an association between spousal caregiving and mental health among older Mexican adults with spouses who had need for care. However, our findings suggest that older adults who are both currently providing or at risk of providing spousal care may need targeted programs and policies to support health and long-term care needs.

Keywords: Spousal caregiving, caregiver health, depressive symptoms, epidemiologic methods

Introduction

In the context of global population aging, there is growing concern about the health of those who care for family members in old-age.1 A large body of scholarship generally suggests that family caregiving has negative health consequences,2–4 including for mental health,3,5,6 physical functioning,2 cardiovascular disease7–9 and mortality.10,11 This research has been largely based in high-income countries, with very little population-based research focused on low and middle-income countries (LMIC). LMICs have distinct demographic and old-age policy landscapes: many are facing rapid population aging with inadequate or non-existent formal long-term care services and supports.12,13 In the absence of formal supports, the burden of care often falls to family members;12,14 prior research suggests that the adverse health impacts of spousal caregiving on caregivers may be exacerbated in settings that have fewer options for formal long-term care.15 Understanding the population health consequences of late-life spousal caregiving can inform priorities as formal long-term care policies and programs are being developed in LMIC settings.

Prior research has drawn on stress process theory16 to explain the primarily negative associations with family caregiving and health – and mental health, in particular.17,18 The onset of family caregiving, including for one’s spouse, can be a pivotal life event characterized by the stress of sudden or gradual declines in a family member’s physical or cognitive abilities as well as substantial changes in family roles and relationships. The ongoing and often physically and psychological demanding work of family caregiving can serve as a chronic stressor with implications for caregivers’ mental and physical health outcomes.2,19,20 The impact of these stressors may be compounded by financial stressors resulting from caregiving-related job loss and/or family member healthcare costs as well as increasing social isolation and/or loneliness21 – resulting from the loss of critical personal coping resources that might otherwise mitigate the adverse impacts of caregiving related stressors.22

Nevertheless, research on the health effects of spousal caregiving faces substantial methodological challenges, including limitations related to confounding, reverse causation, and the selection of the appropriate comparison group.18,23 In addition, studies typically compare the health of spousal caregivers to the health of all married individuals, regardless of their spouses’ need for care. Such a comparison could conflate effects of caregiving with potentially distinct effects of having a spouse who needs care. A more appropriate comparison group would be individuals who are potential spousal caregivers, i.e., individuals who do not serve as caregivers but whose spouses need care.9,23 Such a comparison limits those in the analytic sample to those who are ‘at risk’ of becoming a spousal caregiver.

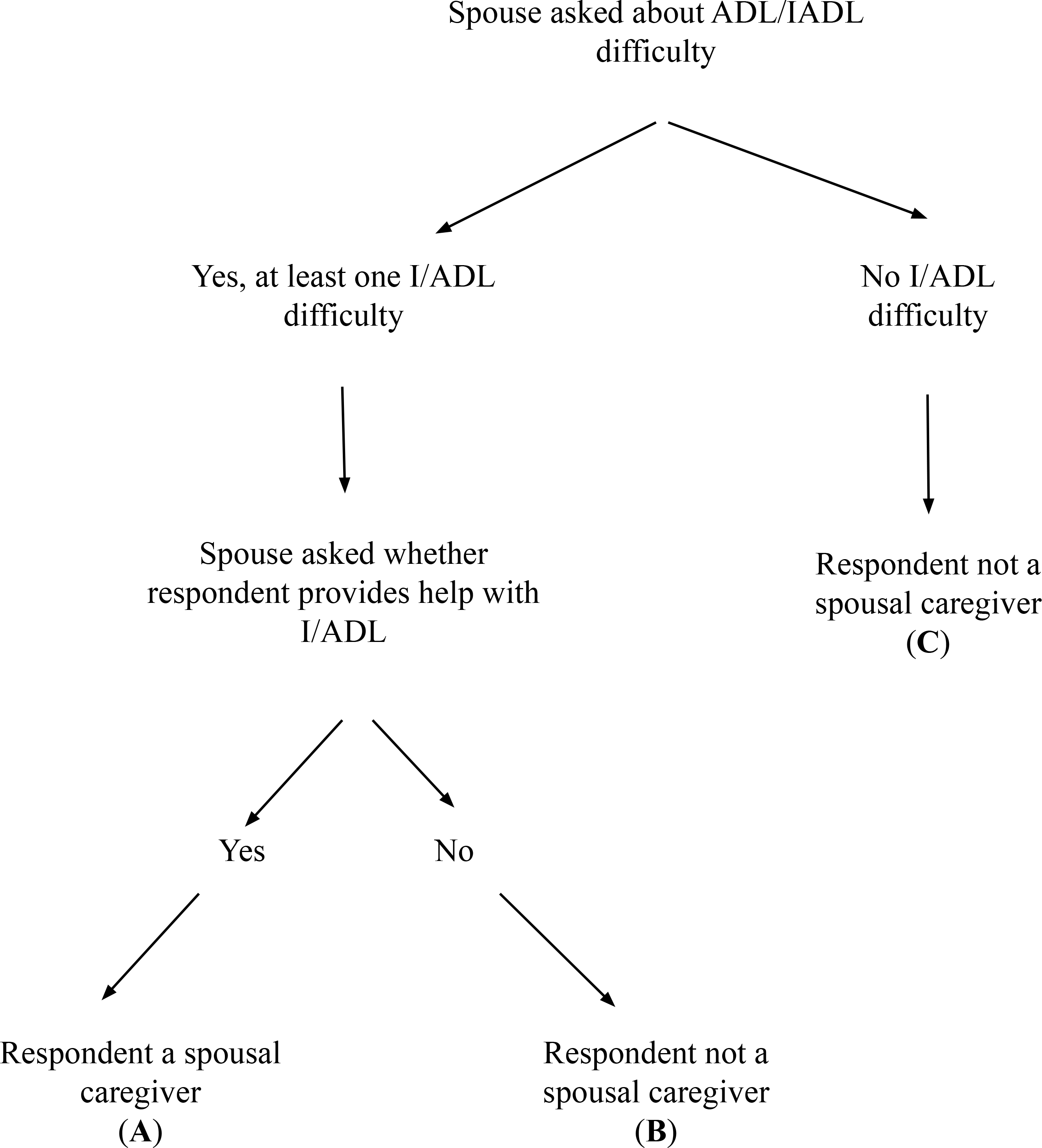

In the present study, we evaluated the effect of spousal caregiving on multiple health outcomes using population-based data on middle-aged and older adults in Mexico. Mexico is a middle-income country with a rapidly aging population and no national long-term care system.24 Moreover, publicly funded programs for older adults are extremely limited and there are no strategies to support family members who currently carry out most of the work to cover care needs.25,26 We compared health outcomes for spousal caregivers to health outcomes for respondents not serving as spousal caregivers but whose spouses needed assistance with activities of daily living (i.e. potential spousal caregivers) (see Figure 1). We expected spousal caregiving would have adverse associations with mental and physical health – and that these associations might be of larger magnitude than observed in high-income countries with more formal long-term supports that might alleviate spousal caregiving burden.

Figure 1.

Flow chart depicting the assignment of spousal caregiving status to respondent based on spouse reports in the Mexican Health and Aging Study. Our primary analyses compare health outcomes for (A) spousal caregivers to outcomes for (B) non-caregivers whose spouses have at least one difficulty with an activity or instrumental activity of daily living (I/ADL), or potential caregivers. The more common practice is to compare outcomes for (A) spousal caregivers to outcomes for both (B) and (C) combined (i.e. all individuals who are married and not providing care, regardless of spousal need for care). This comparison conflates any potential health effects of spousal caregiving with potential health effects of having a spouse who needs care.

Data and Methods

We conducted a pooled cross-sectional analysis using data from four waves of the Mexican Health and Aging Study (MHAS).27 At baseline (2001), the MHAS was a nationally representative sample of Mexican adults aged ≥ 50 years. The MHAS selected households with adults ≥ 50 years who participated in the 2000 Mexican National Employment Survey. Within each household, a target respondent and their spouse or cohabitating partner (regardless of age) were interviewed. Proxy informants for older adults who could not respond on their own were also interviewed. Response rates were 91.8% in 2001, 93.3% in 2003, 88.1% in 2012, and 88.3% in 2015. The study was approved by the IRBs at the University of Maryland, University of Wisconsin, and University of Texas-Medical Branch; analyses of de-identified data were approved by the IRB at the University of California. Data are publicly available at www.mhasweb.org.

The MHAS surveyed 15,186 respondents at baseline. Respondents < 50 years old and respondents who were not married (i.e. single, widowed, or divorced) at baseline (2001) were excluded. Respondents whose interviews were completed by proxies were excluded from the analytic sample, although information from proxy interviews was used to determine spouse’s needs for assistance with activities of daily living.

In primary analyses, the analytic sample included primary respondents at any given wave only if their spouse reported needing assistance with at least one basic activity of daily living (ADL) or instrumental activity of daily living (IADL) (i.e., potential spousal caregivers). Only spouses who reported an I/ADL were asked whether their spouses (i.e., the target respondent) provided care. However, in order to compare our findings to prior research, we carried out an ancillary analysis among married respondents that compared the health of spousal caregivers to the health of all other married respondents irrespective of their spouse’s need for care. A study sample flow chart is presented in the Supplemental Appendix (eAppendix Figure 1).

Spousal Caregiving

Respondent’s caregiving status was based on information provided by their spouse. Spouses were asked about their own needs for assistance with basic ADLs (i.e. getting out of bed, getting dressed, walking, bathing, toileting, eating) and IADLs (i.e. shopping for food, managing money, preparing meals, taking medications). If the spouse indicated a need for assistance with a given I/ADL, they were subsequently asked whether or not their spouse, the target respondent, or another person provided them with assistance with that activity. We assigned spouse’s responses about I/ADLs and receipt of care to the target respondents based on a shared household identifier. A respondent was considered to be a spousal caregiver if their spouse reported that the respondent was providing assistance; a respondent was considered to be a non-caregiver if their spouse did not report the respondent was providing care.

Our primary analyses evaluated caregiving with at least 1 IADL or ADL due to the relatively limited number of overall respondents who reported caregiving related to the six basic ADLs. However, we additionally evaluated associations with ADL caregiving (i.e. helping spouse with one of six basic ADLs) and respondent health at the two-year follow-up visit, when 221 women and 230 men were reported to be caregivers for spouses with ADLs. Sample sizes were too small for subsequent follow-up waves to feasibly estimate the effects of ADL-specific caregiving.

Health Outcomes

Depressive symptoms were measured with a modified 9-item Center for Epidemiological Studies – Depression (CES-D) scale.28 The scale was adapted in the style of the 8-item CES-D scale used for the Health and Retirement Study, which reduced responses to ‘yes’ or ‘no’ for ease of use with low-education older adults.29 Lower-body functional limitations (LBFLs) were measured with eight questions regarding perceived difficulty with: running one mile, walking one or several blocks, climbing one or several flights of stairs, stooping, kneeling, or crouching. For each item, we contrasted those who had “no trouble” with the activity to those who reported they “have trouble, can’t do, or don’t do” the activity. We excluded difficulty with running a mile due to the very high prevalence of difficulty on this item; we summed the remaining seven items to create a continuous measure of LBFLs. Chronic health conditions were measured with a count of six self-reported doctor-diagnosed conditions: hypertension, diabetes, cancer, stroke, heart attack, and arthritis.

Confounders

We selected confounders that may have influenced both spousal caregiving status, either by influencing a spouse’s need for care or a respondent’s ability to provide care, and health outcomes. These included measures of respondents’ early and mid-life characteristics, including age, years of educational attainment, childhood material conditions, childhood health, lifetime occupation (domestic or agricultural versus another lifetime occupation) and whether respondents had been married more than once; spouse indicators of age, years of educational attainment, and lifetime occupation; and household-level measures of urban vs. not urban residence, residence in a historically high out-migration state, numbers of living children and grandchildren.

We additionally included lagged (to the wave immediately prior) measures of respondents’ current work status (yes/no), cognitive performance (measured with an 8-item immediate verbal memory score and an 8-item delayed verbal memory score, and whether or not they visited a doctor in the past year; models with depressive symptoms as the outcome also included lagged lower-body functional limitations and chronic health conditions in the model and vice versa. Lagged household characteristics included monthly income, total assets, the total count of typical household items owned (from a list of 6 possible items), and whether or not an adult child was living in the household. We additionally included a lagged indicator of spouses’ number of chronic health conditions (range: 0 – 6 conditions).

Statistical Analyses

We used Targeted Maximum Likelihood Estimation (TMLE),30–32 to estimate associations between spousal caregiving and health outcomes among married respondents whose spouse reported at least one I/ADL at the wave of interest. TMLE builds upon prior research on the health effects of caregiving that recommends weighting respondents based on a caregiving propensity “score” in order to better balance caregivers and non-caregivers on observed covariates; other research has recommended matching on the propensity score, with the same aim of balancing the distribution of observed covariates across caregivers and non-caregivers.3–5,9,23 However, weighting or matching approaches on their own are vulnerable to the misspecification of a single model (i.e. the propensity score model). TMLE combines a weighting approach with an outcome-based approach, which makes it doubly robust and less reliant on the correct specification of a single model.30,31 We additionally evaluated results using an inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) strategy. The assumptions necessary for causal inference with TMLE are the same as with other observational estimation approaches i.e. no unmeasured confounding, measurement error, or interference; positivity; and consistency. Brief details on the TMLE process are available in the text of the Supplemental Appendix.

Very few respondents met criteria for being in the analytic sample at more than one follow-up wave. For example, of 650 women who had a spouse with ≥ 1 I/ADL at two-year follow-up (2003), 142 met the same inclusion criteria by 11-year follow-up and 96 met inclusion criteria by 14-year follow-up. We therefore were limited to estimating separate cross-sectional associations between spousal caregiving at a single time point and health status at each follow-up wave rather than evaluating long-term patterns of spousal care.

We still leveraged the longitudinal nature of the data by incorporating measures of lagged time-varying confounders captured at prior study waves, including lagged values of the outcome (see Directed Acyclic Graph, eAppendix Figure 2). We did not evaluate associations at baseline because there were no prior waves from which we could measure lagged time-varying covariates. In order to improve our statistical power, we estimated associations after pooling data from respondents whose spouses had ≥ 1 I/ADL from across the study waves. We present wave-specific estimates in the Supplemental Appendix, but our interpretation relies on the pooled results.

Both exposure and outcome models were estimated data-adaptively via the SuperLearner,33 an ensemble machine learning algorithm, in order to allow for more flexible model fitting (e.g. the incorporation of complex interactions or non-linear terms). A total of 10 learners (eAppendix Table 1) were included and the best weighted combination of learners was selected via 5-fold cross-validation. Analyses were done with the ltmle package for R.34 Missing data were addressed via multiple imputation;35 10 imputed datasets were generated and estimates were combined across these datasets using Rubin’s rules.36

Results

At baseline, 846 women and 629 men had a spouse with at least one I/ADL; of these respondents, 60.9% of women and 52.6% of men were providing care to their spouse (Table 1). Also at baseline, women in the analytic sample were an average of 62 years (SD ± 8.9 years) and men an average of 66 years (SD ± 10.2 years). Over 60% of respondents lived in urban (vs. semi-urban or rural) areas, and about two-thirds had at least one adult child living in the household. Select descriptive characteristics for the remaining waves are provided in eAppendix Table 2. The composition of married respondents overall and by potential and actual spousal caregiving status in each wave is presented in eAppendix Table 3; analogous numbers for ADL-specific caregiving are presented in eAppendix Table 4. Baseline descriptive characteristics for the overall sample of married individuals are presented in eAppendix Table 5.

Table 1.

Complete baseline (2001) descriptive characteristics for respondents who reported being married/in a union and whose spouse had at least one need for assistance with basic and instrumental activities of daily living (I/ADL), Mexican Health and Aging Study

| Women (n = 846) |

Men (n = 649) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Provide Care to Spouse (n = 515) | Do Not Provide Care (n = 331) | Provide Care to Spouse (n = 300) | Do Not Provide Care (n = 329) |

|

| ||||

| Outcomes | ||||

| Lower-body functional limitations (range: 0–8) | 2.58 (2.27) | 2.76 (2.26) | 3.66 (2.62) | 3.50 (2.57) |

| Depressive symptoms (range: 0–9) | 4.18 (2.74) | 4.28 (2.76) | 2.09 (2.25) | 2.43 (2.40) |

| Chronic health conditions (range: 0–6) | 0.79 (0.82) | 0.80 (0.83) | 0.66 (0.81) | 0.68 (0.86) |

| Demographic Characteristics | ||||

| Age (in years) | 62.2 (8.9) | 61.9 (8.9) | 65.9 (10.1) | 65.9 (10.4) |

| Spouse age (in years) | 66.5 (10.6) | 65.7 (10.2) | 62.8 (11.0) | 61.7 (10.8) |

| Urban residence | 319 (61.9) | 227 (68.5) | 200 (66.7) | 201 (61.1) |

| Residence in high US out-migration state | 167 (32.4) | 92 (27.8) | 92 (30.7) | 106 (32.3) |

| At least one adult child living in the household | 345 (66.9) | 220 (66.5) | 186 (62.0) | 224 (68.0) |

| Number of living children | 6.07 (3.18) | 5.99 (3.09) | 5.98 (3.26) | 6.43 (3.26) |

| Number of living grandchildren | 13.5 (12.7) | 12.8 (11.4) | 13.56 (12.67) | 13.74 (12.94) |

| Life-course Socio-Economic Status | ||||

| Education (in years) | 3.16 (3.59) | 3.42 (3.59) | 3.43 (3.99) | 3.49 (4.04) |

| Spouse education (in years) | 3.69 (4.24) | 4.13 (4.48) | 3.21 (3.42) | 3.12 (3.54) |

| No sanitation facilities during childhood | 361 (70.0) | 215 (64.9) | 236 (78.6) | 254 (77.3) |

| Agricultural or domestic work in primary lifetime occupation | 130 (25.3) | 110 (27.7) | 136 (45.3) | 162 (49.3) |

| Spouse did agricultural or domestic work in primary lifetime occupation | 236 (46.0) | 150 (45.1) | 82 (27.3) | 91 (27.7) |

| Total household income (in pesos) | 1866 (12828) | 2592 (9044) | 2637 (6536) | 2932 (16423) |

| Total household net worth (in pesos) | 334885 (473274) | 344326 (602553) | 297840 (334620) | 368786 (810843) |

| Currently working | 99 (19.3) | 71 (21.3) | 172 (57.4) | 195 (59.2) |

| Material items in household, (range: 0–6) | 3.52 (1.38) | 3.63 (1.37) | 3.50 (1.36) | 3.54 (1.32) |

| Health and Health Care Utilization | ||||

| Past year medical visit | 352 (68.3) | 244 (73.7) | 185 (61.7) | 187 (56.8) |

| Spouse chronic health conditions (range: 0–6) | 0.90 (0.98) | 0.79 (0.93) | 1.26 (1.01) | 1.05 (0.87) |

| Immediate verbal recall score (range: 0–8) | 4.72 (1.18) | 4.69 (1.16) | 4.42 (1.26) | 4.33 (1.34) |

| Delayed verbal recall score (range: 0–8) | 5.17 (1.18) | 5.11 (1.77) | 4.75 (1.87) | 4.53 (1.97) |

Data presented as Mean (SD) or N (%)

Spousal Caregiving and Depressive Symptoms

Men who were spousal caregivers were estimated to have 0.30 more past-week depressive symptoms on average (range: 0 – 9 symptoms) at the same wave as caregiving was reported, compared to their counterparts who were not providing care but whose spouses also reported at least one I/ADL (95% Confidence Interval [CI]: 0.23, 0.37); there were similar patterns for women (Marginal Risk Difference (RD): 0.15; 95% CI: 0.07, 0.23) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Marginal risk differences in health outcomes by spouse caregiving status among middle-aged and older adults in Mexico

| Women | Men | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Marginal RD | 95% CI | Marginal RD | 95% CI |

| Past-week depressive symptoms (range: 0 – 9) | |||

| 0.15 | (0.07, 0.23) | 0.30 | (0.23, 0.37) |

| Lower-body functional limitations (range: 0 – 7) | |||

| −0.28 | (−0.35, −0.22) | −0.14 | (−0.20, −0.07) |

| Chronic health conditions (range: 0 – 6) | |||

| −0.04 | (−0.07, −0.01) | −0.11 | (−0.14, −0.08) |

Source: Mexican Health and Aging Study, 2001 – 2015. Analytic sample limited at each wave to respondents whose were married or in a union and whose spouse had ≥ 1 ADL or IADL. Estimates are pooled across three follow-up waves; year-specific estimates available in the Supplemental Appendix.

Using an analytic sample of all married respondents—irrespective of their spouse’s I/ADL status—resulted in estimates that were in the same direction but of larger magnitude (Table 3). For this alternative analytic sample, spousal caregiving was associated with more past-week depressive symptoms for both men and women.

Table 3.

Marginal risk differences in health outcomes by spouse caregiving status among middle-aged and older adults in Mexico

| Women | Men | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Marginal RD | 95% CI | Marginal RD | 95% CI |

| Past-week depressive symptoms (range: 0 – 9) | |||

| 0.31 | (0.24, 0.38) | 0.35 | (0.27, 0.42) |

| Lower-body functional limitations (range: 0 – 7) | |||

| 0.15 | (0.09, 0.20) | 0.28 | (0.22, 0.35) |

| Chronic health conditions (range: 0 – 6) | |||

| 0.02 | (−0.004, 0.04) | −0.04 | (−0.07, −0.02) |

Source: Mexican Health and Aging Study, 2001 – 2015. Analytic sample limited at each wave to respondents whose were married or in a union. Estimates pooled across three follow-up waves; year-specific estimates available in the Supplemental Appendix.

Spousal Caregiving and Lower-Body Functional Limitations

For both women and men, pooled estimates using our primary analytic sample of respondents whose spouses had at least one I/ADL difficulty suggested spousal caregiving was associated with fewer lower-body functional limitations relative to not caregiving (RD for women: −0.28; 95% CI: −0.35, −0.22; RD for men: −0.14, 95% CI: −0.20, −0.07) (Table 2).

Estimates using the ancillary analytic sample of all respondents who were married suggested that spousal caregiving was associated with more lower-body functional limitations for women (RD: 0.15, 95% CI: 0.09, 0.20) and men (RD: 0.28, 95% CI: 0.22, 0.35) (Table 3).

Spousal Caregiving and Chronic Health Conditions

Spousal caregiving was associated with fewer average chronic health conditions in our primary analyses that compared caregivers to non-caregivers whose spouses had at least one I/ADL difficulty (Table 2).

There was also no association between spousal caregiving and chronic health conditions for women in analyses that compared spousal caregivers to all other married respondents, regardless of their spouses’ need for care (Table 3). In these ancillary analyses, spousal caregiving was associated with fewer average chronic health conditions (RD: −0.04; 95% CI: −0.07, −0.02) for men.

Ancillary Analyses

Patterns in year-by-year estimates were relatively consistent when evaluating depressive symptoms, but not physical functioning or chronic health conditions (eAppendix Table 6). We found similar patterns of association between ADL-specific caregiving and health for men: associations with more past-week depressive symptoms but fewer lower-body functional limitations and chronic health conditions (eAppendix Table 7). However, there were fully null associations between ADL-specific spousal caregiving and all health outcomes for women at the two-year follow-up. Results were similar across estimates generated using an inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) approach rather than TMLE (eAppendix Table 8).

Discussion

There is little population-based research regarding the health consequences of mid and late-life caregiving in low and middle-income countries (LMICs). Such knowledge is critical as LMICs are facing rapid population aging and in the process of setting long-term care priorities. We evaluated the association between spousal caregiving and health among older adults in Mexico in what is, to our knowledge, the first national-level population-based study to evaluate the health consequences of spousal caregiving in Mexico.

Overall, we found select evidence of adverse associations between spousal caregiving and past-week depressive symptoms, which corresponds to much prior research reporting adverse associations between spousal caregiving and mental health.37,3,6 These adverse associations are generally described as the result of the emotional and physical burden of caregiving, which may have negative consequences for sleep, time for leisure and health promoting activities, and social isolation.2,6 Prior qualitative research among women in Mexico City caring for older family members19,38 has detailed substantial strain stemming from being confined to one’s home, sleep disruption due to being on call for ill family members, and stress related to providing care to multiple family members (e.g. grandchildren, older parents).

We also found that spousal caregiving was unexpectedly associated with fewer lower-body functional limitations and chronic health conditions. However, these protective associations could simply reflect the fact that spousal caregivers are selected on better physical health and functioning compared to their counterparts who are potential caregivers but not providing care.4,39,40 For example, a prospective study of over 4,000 adults in the US found that individuals who became caregivers and continued caregiving had better physical health – but not mental health -- than their counterparts who did not become caregivers or stopped caregiving. This finding has been supported by other studies evaluating the “healthy caregiver” hypothesis,39 and the selection of more physically healthy family members into caregiving has been described as a potential driver of research finding reduced mortality for caregivers as compared to otherwise similar non-caregivers.4

While we attempted to address reverse causation by accounting for lagged values of limitations and chronic health outcomes in estimated models, this would not have been sufficient to address unmeasured change in functional status or chronic health conditions that occurred between survey waves that would likely have contributed to selection into caregiving. Functional disability in particular is a highly dynamic state in late-life.41 Given these substantial challenges and the inconsistency in estimated associations with lower-body functional limitations and chronic health, we conclude that the results provide little convincing evidence on the effects of spousal caregiving on these physical health and functioning outcomes.

Results from analyses that included all married respondents – the more common approach in extant research -- were of larger magnitude and more consistent across study waves. Estimates comparing caregivers to the general population of married respondents may conflated any potential effects of caregiving with effects of having a spouse with care needs. Circumstances that lead spouses to need care (e.g. onset of functional impairment, health conditions) may have unique adverse health consequences beyond those related to caregiving, including the emotional strain of witnessing spousal illness or decline, role changes within the relationship, and “anticipatory” bereavement.42,43 Notably, respondents whose spouse needed care averaged poorer health profiles compared to the broader sample of married respondents, regardless of their caregiving status (see eAppendix Table 5). This may have made it challenging to detect meaningful differences in health outcomes by spousal caregiving status among those with spouse who needed care, given the relatively poor health among this entire group.

Limitations

This analysis has a number of limitations. First, while our analysis improves upon prior methods used to evaluate the health effects of spousal caregiving in observational studies, we are not able to rule out residual unmeasured confounding; we therefore interpreted estimates as associations.

Second, sample sizes were small, precluding analysis of heterogeneity in associations (e.g. by demographic factors, amount or types of care) or model dynamic caregiving patterns across multiple waves. Understanding the impacts of dynamic caregiving on health is a priority for future research.23. Third, there is the potential for selection bias, including due to the exclusion of respondents with proxy informants.

Finally, spousal caregiving was based on reports by the spouse reporting needing care – and was only asked of spouses who reported that they had a need for help with basic or instrumental activities of daily living due to a health condition. This method of measuring spousal caregiving is similarly used in other aging cohort studies.9 Future data collection efforts across global contexts should directly ask respondents about their spousal caregiving status to validate spouse-reported data and/or shed light on possible spousal discordance in the perceptions of spousal caregiving. Directly eliciting caregivers experience in terms of the experience and impact of caregiving is urgently needed in rapidly aging countries with scarce publicly funded programs for older adults and people with disabilities.

Conclusions

Population-based research on the health consequences of spousal caregiving in low and middle-income countries is critical for informing long-term care priorities in the context of rapid aging and few options for formal caregiving. We evaluated the health effects of spousal caregiving in Mexico and attempted to improve methodologically upon prior research on the health effects of spousal caregiving. We uncovered evidence of adverse associations between spousal caregiving and past-week depressive symptoms; we were unable to draw conclusions about associations with physical functioning and health. However, we also found that all respondents whose spouses needed care—i.e. all individuals who either could be or are currently being called on to provide care—were of poorer average health compared to the broader sample. This finding underscores the need for formal supports for all older adults providing care or at risk of caregiving due to declines in their spouses’ health and functioning. Finally, our research leads us to recommend that population-based aging studies invest in improved measures of spousal caregiving and related burden, including direct measurement from respondents themselves.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

The Mexican Health and Aging Study (MHAS) is funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging (R01AG018016, R Wong, PI) and the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI) in Mexico. JMT is supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging (K01AG056602, J Torres, PI). KER is supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Drug Abuse (R00DA042127, K Rudolph, PI). OS is supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R01AI074345-07). MMG is supported by the National Institutes of Aging (RF1AG05548601, MM Glymour and A Zeki Al Hazzouri, Multi-PI). UAM is supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (U54MD012523-03S1).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None to declare.

Data Availability Statement:

Data are publically available for download at www.mhasweb.org.

References

- 1.United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Ageing 2015. New York, NY: United Nations, 2015. (ST/ESA/SER.A/390). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Correlates of physical health of informal caregivers: a meta-analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;62(2):P126–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Capistrant BD, Berkman LF, Glymour MM. Does duration of spousal caregiving affect risk of depression onset? Evidence from the Health and Retirement Study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(8):766–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roth DL, Haley WE, Hovater M, Perkins M, Wadley VG, Judd S. Family caregiving and all-cause mortality: findings from a population-based propensity-matched analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178(10):1571–1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaschowitz J, Brandt M. Health effects of informal caregiving across Europe: a longitudinal approach. Soc Sci Med. 2017;173:72–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Associations of stressors and uplifts of caregiving with caregiver burden and depressive mood: a meta-analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003;58(2):P112–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee S, Colditz GA, Berkman LF, Kawachi I. Caregiving and risk of coronary heart disease in U.S. women: a prospective study. Am J Prev Med. 2003;24(2):113–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Capistrant BD, Moon JR, Berkman LF, Glymour MM. Current and long-term spousal caregiving and onset of cardiovascular disease. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66(10):951–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Capistrant BD, Moon JR, Glymour MM. Spousal caregiving and incident hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2012;25(4):437–443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the Caregiver Health Effects Study. JAMA. 1999;282(23):2215–2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Reilly D, Rosato M, Maguire A. Caregiving reduces mortality risk for most caregivers: a census-based record linkage study. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(6):1959–1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayston R, Lloyd-Sherlock P, Gallardo S, et al. A journey without maps-Understanding the costs of caring for dependent older people in Nigeria, China, Mexico and Peru. PLoS One. 2017;12(8):e0182360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Living Arrangements of Older Persons: A Report on an Expanded International Dataset. New York, NY: United Nations;2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prince M, Group DR. Care arrangements for people with dementia in developing countries. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19(2):170–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wagner M, Brandt M. Long-term care provision and the well-being of spousal caregivers: an analysis of 138 European regions. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2018;73(4):e24–e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aneshensel C, Mitchell U. The Stress Process: Its Origins, Evolution, and Future. In: Johnson R, Turner R, Link B, eds. Sociology of Mental Health. Springer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff MM. Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist. 1990;30(5):583–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Capistrant B Caregiving for older adults and the caregivers’ health: an epidemiologic review. Current Epidemiology Reports. 2016;3:72–80. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mendez-Luck CA, Kennedy DP, Wallace SP. Guardians of health: the dimensions of elder caregiving among women in a Mexico City neighborhood. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(2):228–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: a meta-analysis. Psychol Aging. 2003;18(2):250–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beeson RA. Loneliness and depression in spousal caregivers of those with Alzheimer’s disease versus non-caregiving spouses. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2003;17(3):135–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cannuscio C, Colditz G, Rimm E, Berkman L, Jones C, Kawachi I. Employment status, social ties, and caregivers’ mental health. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(7):1247–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roth DL, Fredman L, Haley WE. Informal caregiving and its impact on health: a reappraisal from population-based studies. Gerontologist. 2015;55(2):309–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Calvo E, Berho M, Roqué M, et al. Comparative analysis of aging policy reforms in Argentina, Chile, Costa Rica, and Mexico. J Aging Soc Policy. 2019;31(3):211–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.López-Ortega M, Aranco N. Envejecimiento y atención a la dependencia en México. Washington, D.C.: Banco Interamericano de Desarrollo/Inter-American Development Bank;2019. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Águila E, López-Ortega M, Angst S. Do income supplemental programs for older Adults’ help reduce primary caregiver burden? Evidence from Mexico. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2019;34(4):385–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong R, Michaels-Obregon A, Palloni A. Cohort profile: the Mexican Health and Aging Study (MHAS). Int J Epidemiol. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46:e2.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Radloff LC. The CES-D scale, a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steffick DE. Documentation of affective functioning measures in the Health and Retirement Study. Ann Arbor, MI: Survey Research Center, University of Michigan;2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schuler MS, Rose S. Targeted Maximum Likelihood Estimation for Causal Inference in Observational Studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;185(1):65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gruber S, van der Laan MJ. Targeted Maximum Likelihood Estimation: A Gentle Introduction. UC Berkeley Division of Biostatistics Working Paper Series. 2009;Working Paper 252. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sofrygin O, Zhu Z, Schmittdiel JA, Adams AS, Grant RW, van der Laan MJ, Neugebauer R. Targeted learning with daily EHR data. Stat Med. 2019;38(16):3073–3090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Polley E, LeDell E, Kennedy C, Lendle S, van der Laan M. SuperLearner: superlearner prediction. R package: version 2.0–22, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lendle SD, Schwab J, Petersen ML, van der Laan MJ. ltmle: An R Package Implementing Targeted Minimum Loss-Based Estimation for Longitudinal Data, R package version 1.1–0, 2018.

- 35.Honaker J, King G, Blackwell M. Amelia II: A Program for Missing Data. R package version 1.7.4, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York, NY: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Gender differences in caregiver stressors, social resources, and health: an updated meta-analysis. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2006;61(1):P33–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mendez-Luck CA, Kennedy DP, Wallace SP. Concepts of burden in giving care to older relatives: a study of female caregivers in a Mexico City neighborhood. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2008;23(3):265–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fredman L, Doros G, Ensrud KE, Hochberg MC, Cauley JA. Caregiving intensity and change in physical functioning over a 2-year period: results of the caregiver-study of osteoporotic fractures. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(2):203–210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCann JJ, Hebert LE, Bienias JL, Morris MC, Evans DA. Predictors of beginning and ending caregiving during a 3-year period in a biracial community population of older adults. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(10):1800–1806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Díaz-Venegas C, Wong R. Recovery from physical limitations among older Mexican adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2020;91:104208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bobinac A, van Exel NJ, Rutten FF, Brouwer WB. Caring for and caring about: disentangling the caregiver effect and the family effect. J Health Econ. 2010;29(4):549–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amirkhanyan AA, Wolf DA. Caregiver stress and noncaregiver stress: exploring the pathways of psychiatric morbidity. Gerontologist. 2003;43(6):817–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are publically available for download at www.mhasweb.org.