Abstract

Posttranslational modification of general transcription factors may be an important mechanism for global gene regulation. The general transcription factor IIA (TFIIA) binds to the TATA binding protein (TBP) and is essential for high-level transcription mediated by various activators. Modulation of the TFIIA-TBP interaction is a likely target of transcriptional regulation. We report here that Toa1, the large subunit of yeast TFIIA, is phosphorylated in vivo and that this phosphorylation stabilizes the TFIIA-TBP-DNA complex and is required for high-level transcription. Alanine substitution of serine residues 220, 225, and 232 completely eliminated in vivo phosphorylation of Toa1, although no single amino acid substitution of these serine residues eliminated phosphorylation in vivo. Phosphorylated TFIIA was 30-fold more efficient in forming a stable complex with TBP and TATA DNA. Dephosphorylation of yeast-derived TFIIA reduced DNA binding activity, and recombinant TFIIA could be stimulated by in vitro phosphorylation with casein kinase II. Yeast strains expressing the toa1 S220/225/232A showed reduced high-level transcriptional activity at the URA1, URA3, and HIS3 promoters but were viable. However, S220/225/232A was synthetically lethal when combined with an alanine substitution mutation at W285, which disrupts the TFIIA-TBP interface. Phosphorylation of TFIIA could therefore be an important mechanism of transcription modulation, since it stimulates TFIIA-TBP association, enhances high-level transcription, and contributes to yeast viability.

Eukaryotic RNA polymerases require the formation of a multiprotein preinitiation complex near the promoter start site for efficient transcription initiation to occur (reviewed in references 8, 42, 49, and 63). The composition of the preinitiation complex may vary among promoters, but the best-studied model promoters indicate that the preinitiation complex consists of the general transcription factors TFIIA, TFIIB, TFIID, TFIIE, TFIIF, and TFIIH. The formation of the preinitiation complex and the subsequent recruitment of RNA polymerase II to the promoter start site can be rate limiting for transcription in vitro and in vivo and are subject to regulation by activators and repressors. Precisely how activators and repressors modulate the formation, stability, and organization of the preinitiation complex remains the subject of considerable investigation (reviewed in reference 47).

One of the first steps in promoter recognition and preinitiation complex assembly is the association of TFIID with the TATA box (2, 36). TFIID is a multiprotein complex that consists of the TATA binding protein (TBP) and TBP-associated factors (3, 16). The general transcription factors TFIIA and TFIIB can bind directly to TBP and stabilize its association with the TATA box (14, 20, 38, 57). The formation of the TFIID-TFIIA-TFIIB complex can be rate limiting for several model promoters in vitro and in vivo (6, 33, 55, 59). Activators stabilize the association of TBP with the TATA element directly or by enhancing the association of TFIIA with TFIID or the association of TFIIB with TFIID (5, 6, 31–33). Thus, it appears that multiple activation mechanisms participate in the complex kinetic regulation of transcription initiation.

The general transcription factor TFIIA is an important regulatory component of preinitiation complex assembly. TFIIA can bind directly to several transcriptional activators and mediate protein-protein contacts which stabilize preinitiation complex formation (7, 29, 43, 45, 56, 61). Additionally, the association of TFIIA with TFIID can induce conformational changes in the TAFs which promote additional contacts with promoter DNA downstream of the TATA element (4, 32, 41). TFIIA can also bind TBP and preclude the association of TBP-specific transcriptional inhibitors, like NC2(Dr1/DRAP1), MOT1, and DSP1 (1, 22, 27; reviewed in reference 24). Thus, TFIIA can be a pivotal factor in the regulation of preinitiation complex stability and conformational activity.

TFIIA is largely conserved between human and yeast (10, 11, 35, 43, 48, 56). The yeast TFIIA genes, TOA1 and TOA2, are essential for viability (25, 48). Mutations in TFIIA which compromise the ability of TFIIA to associate with TBP disrupt transcription from a subset of promoters in vivo (44). The stable association of TFIIA with TBP is important for high-level transcription from a class of promoters with downstream regulated start sites (Tr) and for a subset of promoters required for cell cycle progression through G2/M (44). The requirement for TFIIA was dependent on both core promoter structure and the transcriptional activator, consistent with the function of TFIIA in core promoter selectivity and in mediating protein contacts with activators (44).

Posttranslational modifications of class II general transcription factors have been suspected in the regulation of preinitiation complex assembly and transcriptional activity. However, only a few cases of posttranslational modification have been clearly shown to play a role in regulating the function of the general factors. A cell cycle-dependent phosphorylation of TFIID has been implicated in mitosis-dependent transcriptional repression (51). Phosphatase treatment of the large subunit of TFIIF reduced transcription activity in vitro, suggesting that phosphorylation may also regulate TFIIF function in transcription (28). In addition, several general transcription factors can be phosphorylated by TAFII250 and acetylated in vitro, but these modifications have not been verified in vivo and do not have any clear functional consequence (12, 21, 40).

In this study, we show that the large subunit of yeast TFIIA is phosphorylated in vivo and that this phosphorylation is important for a stable association with TBP DNA and for high-level transcription from induced promoters in vivo. While loss of phosphorylation of TFIIA may be compensated for by other factors in vivo, the modification is essential for viability in the context of a second mutation which further compromises the association of TFIIA with TBP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmid constructs and yeast strains.

The TOA1 gene was cloned from pSH343 (25) (kindly provided by S. Hahn), and PCR was used to engineer the influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) epitope into the amino terminus of TOA1. The product was ligated into pRS415 (54), creating peToa1. By using overlapping PCR (19), mutations were made in the tagged toa1 open reading frame such that the serines at positions 220, 225, and 232 were then read as alanines. The PCR product encoding toa1 S220/225/232A was cloned into pRS415, creating peToa1.1. Other plasmids were made by the same method and create altered versions of toa1 that encode individual alanine substitutions at position 220, 225, 232, or 285. All mutations were confirmed by sequencing, and sequencing of the entire open reading frame of the plasmid encoding toa1 S220/225/232A W285A showed no other mutations.

All strains used to characterize TFIIA were derived from SHY93 (Matα leu2 ura3 his4 Toa1::HIS4/pSH325 [pARS CEN URA3 Toa1]) (25) (kindly provided by S. Hahn). Strain PLY1 was constructed by transforming peToa1 into SHY93 and shuttling out the wild-type TOA1 plasmid (pSH325) by plating on 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA). PLY2 was constructed in the same fashion but with peToa1.1 instead of peToa1. Other strains were made by the same technique with plasmids carrying the other altered forms of toa1.

Preparation of proteins.

Yeast-derived TFIIA containing the HA epitope-tagged Toa1 was isolated from PLY1 whole-cell extract by immunoprecipitation with 12CA5 monoclonal antibody as described previously (64). The altered forms of TFIIA from the toa1 S220/225/232A-expressing strain (or strains expressing other altered forms of toa1) were isolated in the same manner. Yeast-derived TBP (yTBP) was isolated by same method from strain DPY11, which carries HA epitope-tagged TBP (46). Recombinant human TBP (hTBP) was isolated as follows. The gene for hTBP was cloned into pRSET (Invitrogen), creating a hexahistidine form of the protein. The tagged TBP was expressed in Escherichia coli, purified on an Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose column (Qiagen), and renatured as described previously (44). Recombinant yeast TFIIA was isolated by cloning the genes for the large (Toa1) and small (Toa2) subunits of TFIIA into pRSET and isolated as previously reported (44).

DNA binding reactions.

DNA binding reactions for electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) were regularly performed with 12.5 mM HEPES (pH 7.9)–12.5% glycerol–0.4 mg of bovine serum albumin (BSA) per ml–6 mM MgCl2–16 mg of poly(dGdC-dGdC) oligonucleotide–0.4% β-mercaptoethanol (βME) (final volume, 12.5 ml), using the adenovirus E1B TATA box as a probe (26). Binding reaction mixtures were incubated for 50 min at 30°C, separated on a 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA (TBE)–5% acrylamide gel, and visualized by autoradiography. When recombinant TFIIA was incubated with casein kinase II (CKII) prior to EMSA, the treatment was performed with the same concentrations of HEPES (pH 7.9), BSA, MgCl2, poly(dGdC-dGdC) oligonucleotide, glycerol, and βME, as described above. A final concentration of 2 U of CKII (Sigma) per ml and 100 μM ATP, if required, was used in a 30-min incubation at 30°C. The DNA probe and other components of the binding reaction mixture were then added, and the assay was continued. When TFIIA was incubated with potato acid phosphatase (PAP) (Sigma) prior to EMSA, the treatment was also performed with the same concentrations of HEPES (pH 7.9), BSA, MgCl2, poly(dGdC-dGdC) oligonucleotide, glycerol, and βME as for the EMSA binding reaction. Additionally, the protease inhibitors phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (1 mM) and leupeptin (2 μg/ml) were included, along with 1 mM sodium orthovanadate if required. Yeast-derived TFIIA was incubated with 0.7 U of PAP per ml for 30 min at 30°C prior to the addition of probe DNA and the other components of the binding reaction mixture.

In vivo phospholabeling.

TFIIA was labeled with [32P]phosphate after growth to an absorbance at 600 nm of 1.6, essentially as previously described (60). The labeling was done for 1 h in phosphate-depleted medium with 150 μCi of [32P]orthophosphate (NEN) per ml. After the labeling, the cells were lysed by bead beating in buffer containing 100 mM HEPES (pH 7.3), 350 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20, 10% glycerol, 2.0 μg of pepstatin per ml, 2 μg of leupeptin per ml, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and the phosphatase inhibitors Na4P2O7 (20 mM) and NaF (20 mM). The [32P]phosphate-labeled TFIIA was isolated by immunoprecipitation as described above.

S1 nuclease analysis.

Sequences of the oligonucleotides complementary to the URA1, URA3, and HIS3 genes and tRNAW were described previously (44). The probes were labeled by using T4 polynucleotide kinase (Boehringer-Mannheim) and [γ-32P]ATP (ICN) as described previously (44). All cultures were grown on synthetic complete medium to an absorbance at 600 nm of 0.9 to 1.1 (7 × 106 cells/ml). The URA1 and URA3 genes were induced by incubating cultures with 10 μg of 6-azauracil (6-AU) per ml for 2 h at 30°C, and the HIS3 gene was induced by 45 mM 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole (3-AT) treatment at the same temperature for the same period. Isolation of total yeast RNA, annealing of the labeled probe to the RNA, and digestion with S1 nuclease (Boehringer Mannheim) were performed as described previously (23). In each case, 40 μg of total yeast RNA was used per sample. After digestion, samples were analyzed on a 10% denaturing polyacrylamide gel and autoradiography was quantitated on a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). Assays were performed in duplicate at least three times, and representative experiments are shown. tRNAW levels were used as controls for intact RNA and are shown for all experiments.

RESULTS

Phosphorylation of Toa1 in vivo.

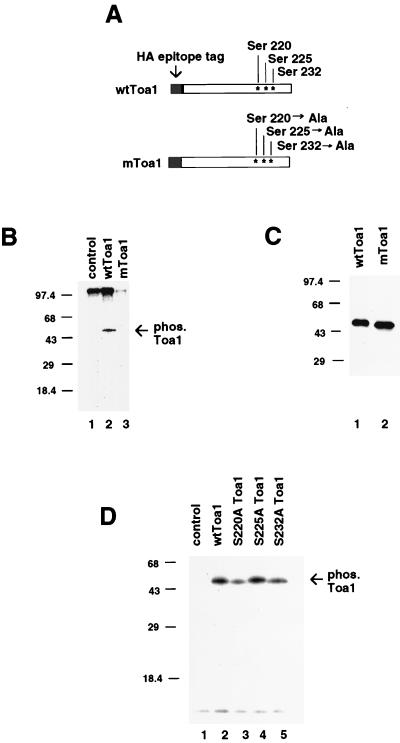

The large subunit of human TFIIA was found to be phosphorylated in vitro by human TAFII250 kinase (12). In unpublished work, we observed that human TFIIA can be phosphorylated on several serine residues in the C-terminal domain (β subunit). These serine residues are partially conserved in the yeast Toa1 C-terminal domain. To determine if phosphorylation of these residues occurs in vivo in yeast, we mutated Toa1 at serine residues 220, 225, and 232 to alanine (Fig. 1A). Wild-type Toa1 (wtToa1) was replaced with the triple-alanine substitution mutant (mToa1) by plasmid shuffle. This mutation in mToa1 did not produce any obvious growth phenotypes on several different carbon sources or at high temperature (data not shown). Strains expressing epitope-tagged wtToa1 or mToa1 were metabolically labeled in vivo with [32P]orthophosphate and then subjected to immunoprecipitation with 12CA5 monoclonal antibody, specific for the HA epitope tag. The peptide eluted immunoprecipitates were examined for phosphorylated Toa1 by autoradiography of sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) gels (Fig. 1B). Immunoprecipitates from control strains expressing untagged Toa1 did not reveal any specific phosphorylated proteins (Fig. 1B, lane 1). Immunoprecipitates from the HA-tagged wtToa1 strain revealed the presence of a highly phosphorylated protein at ∼48 kDa (lane 2). Immunoprecipitates from the HA-tagged mToa1 strain failed to produce a ∼48-kDa phosphoprotein (lane 3). wtToa1 and mToa1 were further assayed by Western blotting to confirm that equal abundances of Toa1 proteins was recovered from immunoprecipitates (Fig. 1C). Both wtToa1 and mToa1 were expressed and immunoprecipitated at similar levels from their respective strains (Fig. 1C, compare lanes 1 and 2). Interestingly, the mobility of wtToa1 was slightly lower than that of mToa1, consistent with a change in the protein phosphorylation state. These results suggest that Toa1 is phosphorylated in vivo and that serine residues 220, 225, and 232 are required for this phosphorylation.

FIG. 1.

Phosphorylation of Toa1 in vivo. (A) Schematic diagram of Toa1 alleles constructed to assay in vivo phosphorylation. mToa1 differs from wtToa1 by the replacement of serine residues 220, 225, and 232 by alanine. Both wtToa1 and mToa1 contain an amino-terminal HA epitope tag used for immunopurification. Both genes were expressed as the sole source of Toa1 in their respective strains. (B) The mToa1, wtToa1, and parental (control) strains were metabolically labeled with [32P]orthophosphate and subjected to immunopurification with HA-specific antisera. Phosphorylated Toa1 was visualized by autoradiography of SDS-PAGE gels and is indicated by the arrow (phos. Toa1). (C) Immunopurified wtToa1 and mToa1 were analyzed by Western blotting with HA-specific antisera. (D) Metabolic labeling of single serine substitution mutants of Toa1 was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. Phosphorylated Toa1 is indicated by the arrow.

To determine if any one of these serine residues was primarily responsible for the phosphorylation of Toa1, we mutated each serine individually (Fig. 1D). We found that no single change of serine to alanine at these three positions was sufficient to completely eliminate the phosphorylation of Toa1. Substitution at serine 220 or serine 232 reduced the amount of phosphorylated Toa1 recovered in immunoprecipitates, but neither eliminated phosphorylation to the same extent as the triple substitution.

Phosphorylation of Toa1 stimulates TA complex formation.

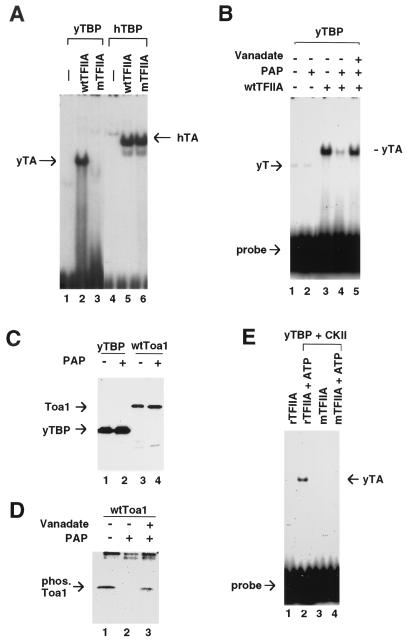

The effect of Toa1 phosphorylation on TFIIA-TBP-DNA (TA) complex formation was examined by EMSA. Since wtToa1 was phosphorylated in vivo and mToa1 was not, we compared the ability of these two TFIIA proteins to form a stable TA complex in EMSA. TFIIA protein was immunoaffinity purified from the wtToa1 or mToa1 strain and tested for the ability to stimulate the binding of yTBP or hTBP to a TATA box-containing probe. In the absence of any TFIIA, yTBP produced a barely detectable bound complex (Fig. 2A, lane 1). Addition of wild-type TFIIA (wtTFIIA) produced a stable complex with yTBP (lane 2). In contrast, equal amounts of mutant TFIIA (mTFIIA) did not stimulate TBP-DNA binding (lane 3). As a control for the abundance and native structure of mTFIIA, we compared the ability of the two TFIIA preparations to stimulate hTBP binding to DNA (lanes 5 and 6). Interestingly, we found that wtTFIIA and mTFIIA were equally capable of stimulating hTBP DNA binding. These results indicate that mTFIIA is expressed to similar levels to wtTFIIA and is nearly identical in native structure but is defective in the ability to stimulate yTBP binding to DNA.

FIG. 2.

Phosphorylation of Toa1 stimulates TA formation. (A) EMSA analysis of yTBP (lanes 1 to 3) or hTBP (lanes 4 to 6) with immunopurified TFIIA from wtToa1 strains (wtTFIIA) or from mToa1 strains (mTFIIA). The yTBP-TFIIA (yTA) and hTBP-TFIIA (hTA) complex are indicated by arrows. (B) Phosphatase treatment of wtTFIIA reduces DNA binding activity of yTBP in EMSA analysis. yTBP and wtTFIIA were treated with PAP (lanes 2, 4, and 5). The phosphatase inhibitor sodium orthovanadate was included in the reaction mixture in lane 5. (C) Western blot analysis of immunopurified yTBP or wtToa1 before (−) and after (+) treatment with PAP. (D) Autoradiography of immunopurified wtToa1 derived from [32P]orthophosphate-labeled yeast cultures. wtToa1 was treated with PAP (lane 2) or with PAP in the presence of sodium orthovanadate (lane 3). (E) EMSA analysis of DNA binding of recombinant TFIIA (rTFIIA) in the presence of yTBP and CKII with or without ATP as indicated in the figure. Bound yTA complex is indicated by the arrow.

The replacement of serine residues with alanine may contribute structural changes in addition to the loss of phosphorylation. To demonstrate that phosphorylation was specifically involved in mediating the enhanced association of TFIIA with TBP-DNA, we tested the effect of phosphatase treatment on TA complex formation (Fig. 2B). Under these conditions, yTBP formed a weakly detectable DNA-bound complex by itself (Fig. 2B, lane 1). Addition of PAP had no effect on the ability of TBP to bind DNA (lane 2). Addition of yeast-derived wtTFIIA stimulated TA complex formation (lane 3). Treatment of TFIIA with PAP resulted in a significant decrease in the amount of TA complex formed (lane 4). Inclusion of sodium orthovanadate, a potent inhibitor of phosphatases, blocked the effect of PAP on TFIIA stimulation of TBP DNA binding (lane 5). To examine the possibility that PAP has proteolytic activity, we tested the effect of PAP on yTBP and TFIIA by Western blot analysis (Fig. 2C). PAP treatment of immunoprecipitates derived from HA-TBP- or HA-Toa1-containing strains showed no detectable effect on the abundance or integrity of TBP or Toa1 (Fig. 2C). In addition, PAP was shown to efficiently dephosphorylate wtToa1 that had been phosphorylated in vivo. Yeast cells metabolically labeled with [32P]orthophosphate were used for the immunoaffinity purification of wtTFIIA (Fig. 2D, lane 1). Treatment of the phosphorylated TFIIA with PAP led to the complete loss of phosphorylated TFIIA (lane 2), while addition of sodium orthovanadate inhibited the phosphatase activity (lane 3). These results clearly indicate that the phosphorylation of Toa1 enhances the ability of TFIIA to stimulate yTBP-DNA complex formation.

Previous studies have shown that recombinant TFIIA was capable of forming the TA complex. However, we have found that yeast-derived wtTFIIA was much more efficient in its ability to form TA than was an equal molar amount of recombinant TFIIA (rTFIIA) derived from E. coli (data not shown). To determine if phosphorylation of rTFIIA could stimulate TA complex formation we tested a series of commercially available kinases (data not shown). Based on inspection of the amino acid sequence of Toa1 serines 220, 225, and 232, it seemed likely that these residues could be phosphorylated by the family of CKII proteins. A commercial preparation of rat liver CKII was tested for its ability to stimulate the TA complex formed with rTFIIA (Fig. 2E). Under the conditions of limiting rTFIIA, no TA complex was formed with yTBP and CKII (lane 1). However, addition of ATP to the reaction mixture strongly stimulated the ability of rTFIIA to form a complex in the presence of CKII and yTBP (lane 2). CKII and ATP had no effect on the ability of mTFIIA to form TA, suggesting that phosphorylation was specific for the serine residues 220, 225, and 232 in Toa1 and that phosphorylation of TBP or other proteins in the TFIIA immunoprecipitates were not responsible for the kinase inducible DNA binding activity (lanes 3 and 4). Additionally, we found that commercial preparations of protein kinase A had no effect on the ability of rTFIIA to form TA (data not shown). Taken together, these results support the role of phosphorylation on residues 220, 225, and 232 in enhancing the formation of a stable TA complex.

mToa1 is defective for high-level transcription.

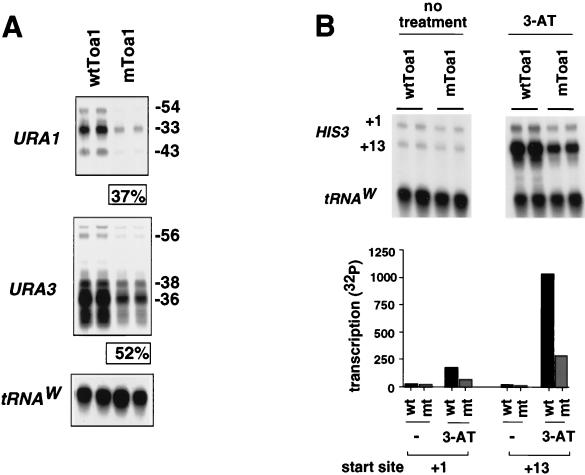

To determine if phosphorylation of TFIIA was important for transcription function in vivo, we compared the mRNA levels of several genes in wtToa1- and mToa1-containing strains. We found that the expression levels for TRP3, PMA1, TOA2, and CLB2 were indistinguishable between the two strains (data not shown). Previous work had shown that mutations in TFIIA which compromise the ability to form the TA complex were most defective for transcription from inducible promoters with multiple start sites, as was found for the URA1, URA3, and HIS3 genes (44). We next compared the mRNA levels of the URA1 and URA3 genes in wtTFIIA- and mTFIIA-containing strains (Fig. 3A). The steady-state mRNA levels of URA1 and URA3 were measured by S1 nuclease protection assay. The downstream start sites are typically associated with high-level induced transcription which can be generated by growth in synthetic complete media lacking uracil and induced by 6-AU. We found that strains carrying the mtoa1 allele expressed the downstream-initiated transcripts of URA1 and URA3 at 37 and 52% of wild-type levels, respectively (Fig. 3A). To further test the effect of mTFIIA on high-level induced transcription, we examined the HIS3 gene under constitutive and 3-AT-induced conditions. In the absence of 3-AT treatment, transcription levels initiating at the +1 and +13 sites of HIS3 were essentially identical in the wtToa1 and mToa1 strains (Fig. 3B, left). In the presence of 45 mM 3-AT, where high levels of HIS3 transcription have been induced, the wtToa1 strain expressed ∼fourfold more transcription from the +13 initiation site and ∼twofold more transcription from the +1 initiation site than was expressed from the mToa1 strain (Fig. 3B, right). Thus, yeast strains expressing mToa1 were defective for supporting maximal levels of induced transcription for several promoters in vivo.

FIG. 3.

RNA levels of highly induced transcripts are reduced in mToa1-containing strains. (A) The URA1 and URA3 gene mRNA transcripts derived from wtToa1 or mToa1 strains were measured by S1 nuclease protection. The start site position is indicated by the numbering on the right. The percentage of wt mRNA levels for the downstream start sites URA1 −33 and −43 and URA3 −38 and −36 are presented as an average value from three independent experiments. S1 protection of tRNAW is used to control for RNA recovery. (B) RNA levels from constitutive (left) and 3-AT-induced (right) HIS3 transcription. The +1 and +13 sites are indicated, and tRNAW was included as an internal control of RNA recovery. Quantitation of wild-type (wt) and mutant (mt) RNA for the +1 and +13 start sites is indicated in the bar graph below.

Toa1 phosphorylation is important for yeast viability.

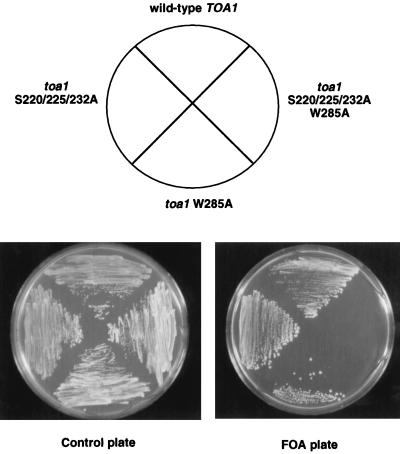

Yeast strains expressing the phosphorylation-defective mToa1 as the only allele of TOA1 showed no apparent growth defect on various carbon sources and at various temperatures. Since mToa1 was compromised for TA complex formation in vitro, we reasoned that the mutation may be compensated for by additional TFIIA-TBP contacts in vivo. The crystal structure of the TA complex indicates that the major contact between Toa1 and TBP is mediated by residue W285 in Toa1 (14, 57). Serine residues 220, 225, and 232 do not appear in the structure, presumably because they are not structured in the crystal. To determine if mutation of the serine residues in mToa1 contributes to a growth defect, we combined mToa1 mutations with an alanine substitution at Toa1 W285. The toa1 W285A mutant had slightly slow growth but was clearly viable (Fig. 4 and data not shown). As mentioned above, the mToa1 mutant, containing S220/225/232A, was unaffected in its growth on synthetic complete media. However, yeast expressing toa1 S220/225/232A/W285A were inviable when the wild-type copy of TOA1 was shuttled out by growth on 5-FOA (Fig. 4, right quadrant). These results indicate that a mutation which eliminates Toa1 phosphorylation creates a lethal phenotype when combined with a second mutation in the TFIIA-TBP interface. This implies that phosphorylation of Toa1 contributes to yeast viability.

FIG. 4.

Phosphorylated serine residues are important for yeast viability. wtToa1- or mToa1-containing strains were tested for growth on selective medium without (control) or with 5-FOA. 5-FOA was used to shuttle out the wild-type TOA1 gene used to cover the lethal mutant allele. The wild-type, triple serine-to-alanine substitution (S220/225/232A), W285A, and combined S220/225/232A/W285A alleles of TOA1 are indicated in the wheel diagram.

DISCUSSION

Posttranslational modifications play a central role in the signal transduction pathways that regulate gene expression. Phosphorylation of general transcription factors is likely to be one end point of signaling mechanisms which regulate transcription activity. The general transcription factor TFIIA plays an important role in mediating the activity of various transcriptional activators and may serve as a good target for modulating the transcription of a class of genes. Thus, the association of TFIIA with TBP is an excellent candidate for regulation by posttranslational modification. In this work, we found that TFIIA was phosphorylated in vivo in yeast and that mutation of three serine residues in the C-terminal domain of Toa1 abrogated phosphorylation in vivo. This mutant was defective for binding to yTBP in vitro and was reduced for maximal-level transcription from several inducible genes. The dephosphorylation of native TFIIA reduced TA complex formation, and the phosphorylation of recombinant TFIIA stimulated TA complex formation. We conclude from this that TFIIA phosphorylation enhances TA complex formation in vitro and is important for maximal transcription levels in vivo.

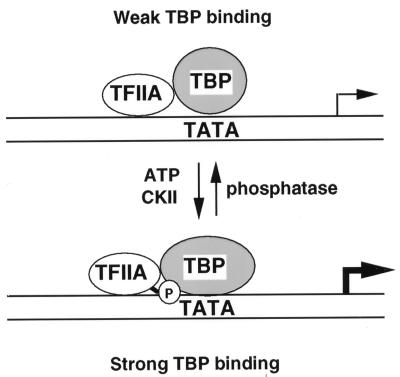

Phosphorylation of TFIIA was important for yeast viability only in the context of a second mutation which compromises the association of TFIIA with TBP. Crystal structure analysis showed that W285 of Toa1 makes direct contact with TBP, and mutagenesis of similarly positioned residues in the small subunit of TFIIA has a direct effect on TA formation (14, 43, 57). Substitution of W285 by alanine had a small effect on yeast growth rates, but the combination of this mutation with mToa1 (S220/225/232A) was lethal (Fig. 4). We interpret this synthetic lethality to indicate that a combination of redundant, low-affinity protein contacts comprise the interfaces between TFIIA, TBP, and DNA (Fig. 5). Phosphorylation of Toa1 may contribute a direct contact with TBP or DNA or may induce a conformational change that increases the overall stability of the TA complex. We also found that phosphorylation of yeast TFIIA did not stimulate binding to human TBP, raising the possibility that phosphorylation is important for interactions with the nonconserved amino-terminal domain of TBP. The amino-terminal domain of human TBP mediates an association with the SNAP complex, which is required for transcription of the U6 small nuclear RNA gene (37). However, it is not clear that TFIIA functions in U6 transcription regulation, nor is it clear that the amino-terminal domain of yeast TBP has a similar function in yeast.

FIG. 5.

Model summarizing the potential role of Toa1 phosphorylation in enhancing TA complex formation. Phosphoserines in Toa1 are predicted to contribute additional contacts to the interface between TFIIA and either TBP or DNA. Phosphorylation of Toa1 by CKII stimulated TA complex formation. Enhanced binding was important for high-level transcription.

Phosphorylation of TFIIA did affect transcription from RNA polymerase II-dependent promoters. Phosphorylation-defective TFIIA (mToa1) was incapable of supporting high-level transcription from URA1, URA3 induced by 6-AU, and HIS3 induced by 3-AT. mToa1 was not defective for transcription in the absence of these chemical challenges or for several constitutively expressed transcripts. Thus, phosphorylation of TFIIA is critical for maximal transcription levels required after chemical challenge. High-level transcription may be particularly dependent on efficient rates of transcription reinitiation. Other studies have shown that a stable TBP-TFIIA complex correlates with efficient transcription reinitiation (50, 62). Thus, one possible role of TFIIA phosphorylation is to stabilize the TBP-TFIIA complex at a transcriptionally active promoter and enhance the reinitiation process required for maximal levels of transcription.

The activity of several general transcription factors is regulated by protein phosphorylation (18). The most extensively studied example is the phosphorylation of the carboxy-terminal domain (CTD) of RNA polymerase II (9). The CTD can be phosphorylated by several different kinases, including the cyclin-dependent kinase–cyclin pairs found in the SRB-mediator and TFIIH subcomplexes (30, 52, 53). Phosphorylation of the RNA polymerase II CTD correlates with the elongating RNA polymerase, while the unphosphorylated CTD correlates best with transcription initiation and complex assembly (9, 34, 39). Thus, a phosphorylation cycle on the CTD may regulate transcription initiation and promoter clearance. Phosphorylation of TFIID subunits also correlates with repression of transcription initiation (51). TFIID components are phosphorylated during mitosis, and extracts derived from cells arrested in mitosis were significantly inhibited in transcription activity. Thus, phosphorylation of the CTD and TFIID correlate with the loss of activity in transcription initiation. In contrast to these examples of phosphorylation inhibiting transcription, we have found that phosphorylation of TFIIA correlates with an increase in transcription activity. The phosphorylation-dependent increase in TFIIA transcription activity reflects the distinct role of TFIIA as a transcriptional modulator and the likelihood that TFIIA is phosphorylated by different kinases from those that phosphorylate the CTD or TFIID.

The amino acid residues in Toa1 required for phosphorylation in vivo were mapped to at least two of three serine residues in the carboxy-terminal region of Toa1 (S220/225/232). While this region of TFIIA is not highly conserved in yeast, humans, and Drosophila, the three CKII acceptor sites are conserved in the same subdomain of Toa1 in all three species. While commercial preparations of CKII were capable of phosphorylating these sites and stimulating TFIIA-TBP-DNA binding, it is not clear that CKII performs this function in vivo. CKII phosphorylates several transcription factors and modulates their activity; these include general factors TFIIIB (15) and upstream binding factor (UBF) (58) and coactivators NC2/Dr1 (17) and PC4 (13). We originally observed that human TAFII250 could phosphorylate homologous residues in the human protein, but it failed to stimulate yeast TFIIA binding to TBP (unpublished data). We did not find any evidence that the yeast homologue of human TAFII250 (yTAFII145) is capable of phosphorylating these same residues of TFIIA in vitro. Thus, it will be important to determine whether CKII or some related protein kinase phosphorylates TFIIA in vivo and, more importantly, whether phosphorylation of TFIIA is subject to regulatory controls which modulate transcription function.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank S. Hahn for providing strains and plasmids. We thank J. Ozer and S. Berger for comments on the manuscript and the Wistar Sequencing Facility for technical assistance.

This work was supported in part by a grant from NIH (GM 54687-02) and the Leukemia Society of America to P.M.L. S.S. was supported by an NIH postdoctoral training grant to the Wistar Institute (CA09171).

REFERENCES

- 1.Auble D T, Hansen K E, Mueller C G, Lane W S, Thorner J, Hahn S. Mot1, a global repressor of RNA polymerase II transcription, inhibits TBP binding to DNA by an ATP-dependent mechanism. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1920–1934. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.16.1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buratowski S, Hahn S, Guarente L, Sharp P A. Five intermediate complexes in transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II. Cell. 1989;56:549–561. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90578-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burley S K, Roeder R G. Biochemistry and structural biology of transcription factors IID (TFIID) Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:769–799. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.004005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chi T, Carey M. Assembly of the isomerized TFIIA-TFIID-TATA ternary complex is necessary and sufficient for gene activation. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2540–2550. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.20.2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chi T, Lieberman P, Ellwood K, Carey M. A general mechanism for transcriptional synergy by eukaryotic activators. Nature. 1995;377:254–257. doi: 10.1038/377254a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choy B, Green M R. Eukaryotic activators function during multiple steps of preinitiation complex assembly. Nature. 1993;366:531–536. doi: 10.1038/366531a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clemens K E, Piras G, Radonovich M F, Choi K S, Duvall J F, DeJong J, Roeder R, Brady J N. Interaction of the human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 Tax transactivator with transcription factor IIA. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4656–4664. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.4656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conaway R C, Conaway J W. General initiation factors for RNA polymerase II. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:161–190. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.001113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dahmus M E. Reversible phosphorylation of the C-terminal domain of RNA polymerase II. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19009–19012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.32.19009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.De Jong J, Bernstein R, Roeder R G. Human general transcription factor TFIIA: characterization of a cDNA encoding the small subunit and requirement for basal and activated transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:3313–3317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Jong J, Roeder R G. A single cDNA, hTFIIA/alpha, encodes both the p35 and p19 subunits of human TFIIA. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2220–2234. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.11.2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dikstein R, Ruppert S, Tjian R. TAFII250 is a bipartite protein kinase that phosphorylates the base transcription factor RAP74. Cell. 1996;84:781–790. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ge H, Zhao Y, Chait B T, Roeder R G. Phosphorylation negatively regulates the function of coactivator PC4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12691–12695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geiger J H, Hahn S, Lee S, Sigler P B. The crystal structure of the yeast TFIIA/TBP/DNA complex. Science. 1996;272:830–836. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghavidel A, Schultz M C. Casein kinase II regulation of yeast TFIIIB is mediated by the TATA-binding protein. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2780–2789. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.21.2780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodrich J A, Tjian R. TBP-TAF complexes: selectivity factors for eukaryotic transcription. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1994;6:403–409. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goppelt A, Stelzer G, Lottspeich R, Meisterernst M. A mechanism for repression of class II gene transcription through specific binding of NC2 to TBP-promoter complexes via heterodimer histone fold domains. EMBO J. 1996;15:3105–3116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hampsey M. Molecular genetics of the RNA polymerase II general transcriptional machinery. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:465–503. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.2.465-503.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho S N, Hunt H D, Horton R M, Pullen J K, Pease L R. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imbalzano A N, Zaret K S, Kingston R E. Transcription factor (TF) IIB and TFIIA can independently increase the affinity of the TATA-binding protein for DNA. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:8280–8286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Imhof A, Yang X J, Ogryzko V V, Nakatani Y, Wolffe A P, Ge H. Acetylation of general transcription factors by histone acetyltransferases. Curr Biol. 1997;7:689–692. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00296-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Inostroza J A, Mermelstein F H, Ha I, Lane W S, Reinberg D. Dr1, a TATA-binding protein-associated phosphoprotein and inhibitor of class II gene transcription. Cell. 1992;70:477–489. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90172-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iyer V, Struhl K. Mechanism of differential utilization of the his3 TR and TC TATA elements. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:7059–7066. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.12.7059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaiser K, Meisterernst M. The human general co-factors. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:342–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kang J J, Auble D T, Ranish J A, Hahn S. Analysis of the yeast transcription factor TFIIA: distinct functional regions and a polymerase II-specific role in basal and activated transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1234–1243. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.3.1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kao C C, Lieberman P M, Schmidt M C, Zhou Q, Pei R, Berk A J. Cloning of a transcriptionally active human TATA binding factor. Science. 1990;248:1646–1650. doi: 10.1126/science.2194289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kirov N, Lieberman P, Rushlow C. The mechanism of repression by DSP1 (dorsal switch protein) involves interference with preinitiation complex formation. EMBO J. 1995;15:7079–7087. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kitajima S, Chibazakura T, Yonaha M, Yasukochi Y. Regulation of the human general transcription initiation factor TFIIF by phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:29970–29977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kobayashi N, Boyer T G, Berk A J. A class of activation domains interacts directly with TFIIA and stimulates TFIIA-TFIID-promoter complex assembly. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6465–6473. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.11.6465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liao S M, Zhang J H, Jeffrey D A, Koleske A J, Thompson C M, Chao D M, Viljoen M, Vanvuuren H J J, Young R A. A kinase-cyclin pair in the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Nature. 1995;374:193–196. doi: 10.1038/374193a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lieberman P M, Berk A J. The Zta trans-activator protein stabilizes TFIID association with promoter DNA by direct protein-protein interaction. Genes Dev. 1991;5:2441–2454. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.12b.2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lieberman P M, Berk A J. A mechanism for TAFs in transcriptional activation: activation domain enhancement of TFIID-TFIIA-promoter DNA complex formation. Genes Dev. 1994;8:995–1006. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.9.995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin Y S, Green M R. Mechanism of action of an acidic transcriptional activator in vitro. Cell. 1991;64:971–981. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90321-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu H, Flores O, Weinmann R, Reinberg D. The nonphosphorylated form of RNA polymerase II preferentially associates with the preinitiation complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:10004–10008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.22.10004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ma D, Watanabe H, Mermelstein F, Admon A, Oguri K, Sun X, Wada T, Imai T, Shiroya T, Reinberg D. Isolation of a cDNA encoding the largest subunit of TFIIA reveals functions important for activated transcription. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2246–2257. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.11.2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maldonado E, Ha I, Cortes P, Weis L, Reinberg D. Factors involved in specific transcription by mammalian RNA polymerase II: role of transcription factors IIA, IID, and IIB during formation of a transcription-competent complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:6335–6347. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.12.6335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mittal V, Hernandez N. Role for the amino terminal region of human TBP in U6 snRNA transcription. Science. 1997;275:1136–1140. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5303.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nikolov D B, Chen H, Halay E D, Usheva A A, Hisatake K, Lee D K, Roeder R G, Burley S K. Crystal structure of a TFIIB-TBP-TATA-element ternary complex. Nature. 1995;377:119–128. doi: 10.1038/377119a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Brien T, Hardin S, Greenleaf A, Lis J T. Phosphorylation of RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain and transcription elongation. Nature. 1994;370:75–77. doi: 10.1038/370075a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Brien T, Tjian R. Functional analysis of the human TAFII250 N-terminal kinase domain. Mol Cell. 1998;1:905–911. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80089-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oelgeschlager T, Chiang C M, Roeder R G. Topology and reorganization of a human TFIID-promoter complex. Nature. 1996;382:735–738. doi: 10.1038/382735a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Orphanides G, Lagrange T, Reinberg D. The general transcription factors of RNA polymerase II. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2657–2683. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.21.2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ozer J, Bolden A H, Lieberman P M. Transcription factor IIA mutations show activator-specific defects and reveal a IIA function distinct from stimulation of TBP-DNA binding. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:11182–11190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.19.11182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ozer J, Lezina L E, Ewing J, Audi S, Lieberman P M. Association of transcription factor IIA with TATA binding protein is required for transcriptional activation of a subset of promoters and cell cycle progression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2559–2570. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ozer J, Moore P A, Bolden A H, Lee A, Rosen C A, Lieberman P M. Molecular cloning of the small (gamma) subunit of human TFIIA reveals functions critical for activated transcription. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2324–2335. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.19.2324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Poon D, Schroeder S, Wang C K, Yamamoto T, Horikoshi M, Roeder R G, Weil P A. The conserved carboxy-terminal domain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae TFIID is sufficient to support normal cell growth. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:4809–4821. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.10.4809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ptashne M, Gann A. Transcriptional activation by recruitment. Nature. 1997;386:569–577. doi: 10.1038/386569a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ranish J A, Lane W S, Hahn S. Isolation of two genes that encode subunits of the yeast transcription factor IIA. Science. 1992;255:1127–1129. doi: 10.1126/science.1546313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roeder R G. The role of general initiation factors in transcription by RNA polymerase II. Trends Biochem. 1996;21:327–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sandaltzpoulos R, Becker P B. Heat shock factor increases the reinitiation rate from potentiated chromatin templates. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:361–367. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Segil N, Guermah M, Hoffmann A, Roeder R G, Heintz N. Mitotic regulation of TFIID: inhibition of activator-dependent transcription and changes in subcellular localization. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2389–2400. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.19.2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Serizawa H, Makela T P, Conaway J W, Conaway R C, Weinberg R A, Young R A. Association of Cdk-activating kinase subunits with transcription factor TFIIH. Nature. 1995;374:280–282. doi: 10.1038/374280a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shiekhattar R, Meremelstein F, Fisher R P, Drapkin R, Dynlacht B, Wessling H C, Morgan D O, Reinberg D. Cdk-activating kinase complex is a component of human transcription factor TFIIH. Nature. 1995;374:283–287. doi: 10.1038/374283a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sikorski R S, Hieter P. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1989;122:19–27. doi: 10.1093/genetics/122.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stargell L A, Struhl K. The TBP-TFIIA interaction in response to acidic activators in vivo. Science. 1995;269:75–78. doi: 10.1126/science.7604282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sun X, Ma D, Sheldon M, Yeung K, Reinberg D. Reconstitution of human TFIIA activity from recombinant polypeptides: a role in TFIID-mediated transcription. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2336–2348. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.19.2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tan S, Hunziker Y, Sargent D F, Richmond T J. Crystal structure of a yeast TFIIA/TBP/DNA complex. Nature. 1996;381:127–134. doi: 10.1038/381127a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Voit R, Kuhn A, Sander E E, Grummit I. Activation of mammalian ribosomal gene transcription requires phosphorylation of the nucleolar transcription factor UBF. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:2593–2599. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.14.2593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang W, Gralla J D, Carey M. The acidic activator GAL4-AH can stimulate polymerase II transcription by promoting assembly of a closed complex requiring TFIID and TFIIA. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1716–1727. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.9.1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Warner J R. Labeling of RNA and phosphoproteins in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Methods Enzymol. 1991;194:423–428. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)94033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yokomori K, Zeidler M P, Chen J L, Verrijzer C P, Mlodzik M, Tjian R. Drosophila TFIIA directs cooperative DNA binding with TBP and mediates transcriptional activation. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2313–2323. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.19.2313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zawel L, Kumar K P, Reinberg D. Recycling of the general transcription factors during RNA polymerase II transcription. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1479–1490. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.12.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zawel L, Reinberg D. Common themes in assembly and function of eukaryotic transcription complexes. Ann Rev Biochem. 1995;64:533–561. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.002533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zhou Q, Lieberman P M, Boyer T G, Berk A J. Holo-TFIID supports transcriptional stimulation by diverse activators and from a TATA-less promoter. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1964–1974. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.10.1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]