Abstract

Objectives

The COVID-19 pandemic caused countries across the globe to impose restrictions to slow the spread of the virus, with people instructed to stay at home and reduce contact with others. This reduction in social contact has the potential to negatively impact mental health and well-being. The restrictions are particularly concerning for people with existing chronic illnesses such as Parkinson's disease, who may be especially affected by concerns about the pandemic and associated reduction of social contact. The aim of this review was to synthesise published literature on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the social and psychological well-being of people with Parkinson's disease.

Study design

The design of this study is a scoping review.

Methods

We searched five electronic databases for English language articles containing primary data on this topic.

Results

Thirty-one relevant studies were found and included in the review. Six main themes were identified: impact of the pandemic on physical and mental health; COVID-19 concerns; access to health care; impact on daily and social activities; impact on physical activity and impact on caregivers. Levels of perceived risk of COVID-19 differed across studies, but most participants had adopted preventive measures such as staying at home and reducing social contacts. Participants in many studies reported a discontinuation of regular healthcare appointments and physiotherapy, as well as concerns about being able to obtain medication. Loss of daily activities and social support was noted by many participants. There was mixed evidence on the impact of the pandemic on physical exercise, with some studies finding no change in physical activity and others reporting a reduction; generally, participants with reduced physical activity had poorer mental health and greater worsening of symptoms. Caregivers of people with Parkinson's disease were more likely to be negatively affected by the pandemic if they cared for people with complex needs such as additional mental health problems.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic has had negative effects on the physical and mental health of people with Parkinson's disease, perhaps due to disruption of healthcare services, loss of usual activities and supports and reduction in physical activity. We make recommendations for policy, practice and future research.

Keywords: Coronavirus, COVID-19, Mental health, Pandemic, Parkinson disease, Psychological impact, Scoping review, Well-being

Introduction

December 2019 saw the outbreak of novel coronavirus COVID-19, which has (as of April 2021) affected almost every country and seen more than 150,000,000 confirmed cases and 3,000,000 deaths.1 Most countries imposed restrictions on movement and social activities to slow the spread of the virus, leading to concerns that social isolation could negatively impact well-being and mental health.2

These social restrictions and potential loss of access to usual support systems may have particularly affected people with existing chronic health conditions, such as people with Parkinson's disease3 (PwPD) – a neurodegenerative disease marked by cognitive impairment, frailty and comorbidity. The effects of COVID-19 restrictions could be extremely detrimental to PwPD in several ways, with consequences to structural health care, physical health and mental health. PwPD have been labelled vulnerable due to pandemic-related disruptions in specific treatments4 such as deep brain stimulation.5 In a global survey of healthcare workers, many reported that their patients with Parkinson's disease (PD) had experienced difficulty obtaining regular medications and increased disability.6 The pandemic has also caused disruption to PD-related research and clinical trials.7

The potential loneliness caused by restrictions on socialisation and lack of access to usual support may pose particular risks for PwPD, who are at risk of depression when socially isolated.8 Previous research has shown that participation in social activities is associated with better quality of life and better mental health for PwPD.9 Evidence suggests that PwPD who feel lonely or isolated have greater symptom severity and poorer quality of life,10 whilst social contact is protective of both psychological well-being and cognitive performance;11 therefore, the pandemic-related restrictions on socialisations may have had a negative impact.

Helmlich and Bloem3 raised concerns about the mental health impact of the pandemic on PwPD. They suggest the drastic changes and restrictions imposed require flexibility and rapid adaptation to new circumstances, which may be difficult for PwPD, many of whom experience cognitive and motor inflexibility; PwPD are already at increased risk of chronic stress; and a reduction in physical activities may greatly affect PwPD, for whom exercise has been associated with better clinical outcomes and less psychological stress. Mental health problems are already common in PwPD, including depression,12 anxiety13 and obsessive-compulsive disorder;14 there is a risk these could worsen due to the pandemic. It is therefore important to understand the specific impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on PwPD to know how best to support them at this time and also in the case of future pandemics. This scoping review aimed to synthesise existing literature on the impact the COVID-19 pandemic has had on the social and psychological well-being of PwPD and their experiences during the pandemic-related restrictions. We did not aim to investigate the impact on PwPD of actually contracting COVID-19; rather, we aimed to collate literature on how the social restrictions imposed due to COVID-19 may have affected their well-being.

Methods

Following the scoping review framework described by Arksey and O'Malley,15 this review consisted of the following stages:

Identify the research question

What has been the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated social restrictions on the social and psychological well-being of PwPD?

Identify relevant studies

In April 2021, we systematically searched PsycInfo, Medline, Embase, Global Health and Web of Science using the following search strategy: (coronavirus or covid∗ or sars-cov-2) AND (parkinson∗) AND (psychological or mental health or wellbeing or well-being or depression or anxiety or emotion∗ or stress∗ or distress∗ or psychiatric or resilience or mood∗). Reference lists of relevant studies were hand searched.

Study selection

Inclusion criteria for the study were as follows: studies had to be published in the English language; contain primary data on the impact the COVID-19 pandemic has had on PwPD and be published in journals (i.e. preprints were excluded). Case studies were excluded but studies with any sample size greater than one were included. There were no exclusion criteria relating to study methodology. Citations were imported into EndNote reference management software (Thomson Reuters, New York) where duplicates were automatically removed. The titles and abstracts were screened for relevancy and any clearly not relevant to the review were excluded. Full texts of remaining citations were obtained and screened against the inclusion criteria. Any not meeting the criteria at this stage were excluded.

Chart the data

Data from included studies were extracted onto a spreadsheet with the following headings: authors, year of publication, country, time point of data collection, number of participants, demographic characteristics of participants, variables measure, tools used and key results. Thematic analysis16 was used to group the results of included studies into a typology.

Collate, summarise and report results

Each of the themes identified is summarised in the results section with a narrative description of the evidence found within each theme.

Results

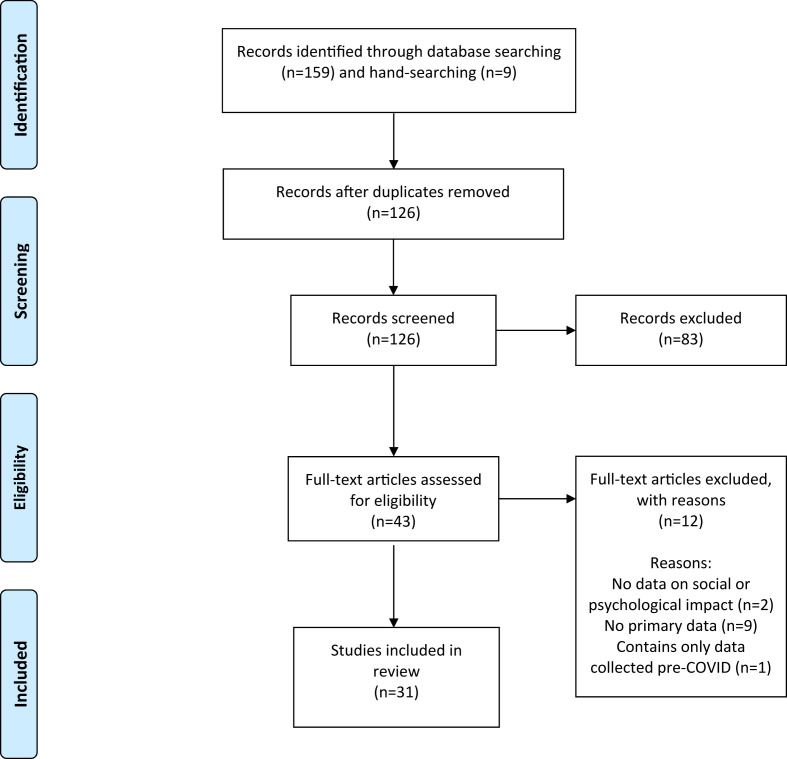

Database searches yielded 159 results, of which 42 were duplicates, and an additional nine articles were found via hand searching reference lists. After screening, a total of 31 studies remained for inclusion in the review. Fig. 1 illustrates the screening process.

Fig. 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

The studies included in the review were from a range of countries: Italy,17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 China,26 , 27 India,28 , 29 Japan,30 , 31 Turkey,32 , 33 the USA,34 , 35 Egypt,36 Germany,37 Iran,38 Luxembourg,39 Morocco,40 the Netherlands,41 Slovenia,42 South Korea,43 Spain44 and the UK;45 one study included participants from both Denmark and Sweden46 and another included participants from every continent.47 Study populations ranged from 28 to 6881 participants. Various methodologies were used: most studies were cross-sectional and used quantitative measures;19 , 21 , 23 , 25 , 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34 , 36 , 38 , 41, 42, 43, 44 , 47 two used qualitative interviews37 , 39 and two used a combination of qualitative and quantitative measures.17 , 20 Two studies included quantitative measures at multiple time points during the COVID-19 pandemic,26 , 40 two studies asked participants to retrospectively rate aspects of their prepandemic well-being and their current status27 , 35 and four compared measures taken during lockdown to assessments already completed before the pandemic.18 , 22 , 45 , 46 One study was a descriptive analysis of emails, texts and voice messages from PwPD to their clinic.24 Table 1 presents an overview of study details, and Supplementary File I presents an overview of their key results.

Table 1.

Overview of included studies, presented in alphabetical order by author name.

| Study (authors, year) | Country | Participants (n) | Sociodemographic characteristics of participants | Variables – measures used; data collection time point(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balci et al. (2021)32 | Turkey | 45 patients with Parkinson's disease vs 43 controls | Patients: 33.3% women, mean age :67 years; Controls: 44.2% women, mean age: 66 years |

Physical activity – Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly Anxiety and depression – Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale Data collected June 2020; participants asked to respond considering the time between 11 March 2020 (declaration of first COVID-19 case in Turkey) and 1 June 2020 (end of lockdown restrictions in Turkey) |

| Baschi et al. (2020)17 | Italy | 34 patients with PD and no cognitive impairment vs. 31 patients with PD and mild cognitive impairment vs. 31 patients with with mild cognitive impairment not associated with PD | 39.6% female, mean age 67.3 | Parkinson's disease – Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale; Functional independence – Basic and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living scales; Cognitive impairment – Mini Mental State Examination; Depressive symptoms – Geriatric Depression Scale; Impact of pandemic – semistructured interviews; Change in symptoms – study-specific questionnaire completed by PwPD and caregivers; Change in global cognition – Mini Mental State Examination Motor and non-motor changes – MDS-UPDRS Parts I and II Measures taken 10 weeks after lockdown |

| Brown et al. (2020)47 | USA (authors in USA, approximately 80% of participants in USA, although all continents are represented) | 5429 patients vs. 1452 controls | Patients with Parkinson's disease and COVID-19: 53% women, mean age: 65 years Patients with Parkinson's disease without COVID-19: 48% women, mean age: 68 years Controls with COVID-19: 92% women, mean age: 57 years Controls without COVID-19: 78% women, mean age: 61 years |

COVID-19 symptoms/diagnosis, testing, risk factors and treatment; change in Parkinson's disease symptoms; effect of social distancing measures on healthcare access, social interactions and other essential activities – all measured with study-specific scales Measures taken between April and May 2020 |

| De Micco et al. (2021)18 | Italy | 94 | 34% women, mean age at last prelockdown assessment: 65.47 years | Prelockdown assessments: Disease severity – Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale; Impact of Parkinson's disease on ability to cope with daily life – Schwab and England Scale; Non-motor symptoms – Non-Motor Symptom Scale; Cognitive functioning – Montreal Cognitive Assessment; Depression – Beck Depression Inventory; Anxiety – Parkinson Anxiety Scale; Apathy – Apathy Evaluation Scale; Fatigue – Parkinson Fatigue Scale; Daytime sleepiness – Epworth Sleepiness Scale; Quality of life – Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire-39 Assessments after lockdown: Psychological impact of lockdown – Impact of Events Scale-Revised; Psychological distress – Kessler Psychological Distress Scale; Caregiver strain – Zarit Burden Inventory Measures taken after a mean of 40 days quarantine and compared with data from each patient's last prelockdown visit |

| Del Prete et al. (2021)19 | Italy | 740 (0.9% who had been diagnosed with COVID-19) | Not reported | Possible worsening of motor symptoms, mood, insomnia – telephone interviews; Depression, anxiety – Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21; Acceptability of telemedicine and accessibility to doctors – study-specific questions Measures taken between April and May 2020 |

| El Otmani et al. (2021)40 | Morocco | 50 | 52% women; mean age: 60.4 years | Depression and anxiety – Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale Measures taken at the beginning of lockdown and after six weeks of full confinement |

| Feeney et al. (2021)34 | USA | 1342 | 50.6% women, mean age: 70.9 years | Knowledge, attitudes and practices – study-specific surveys Measures taken between May and June 2020 |

| Guo et al. (2020)26 | China | 113 | 41.6% women; mean age: 69.5 years | COVID-19 experiences – COVID-19 Questionnaire for PD Patients during the Period of Epidemic Prevention and Control; Parkinson's disease difficulties – Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire 39 Measures taken during ‘epidemic prevention and control’ period (February–March 2020) and followed up during the gradual release of this period (April 2020) |

| Hanff et al. (2020)39 | Luxembourg | 606 | 33.83% women, mean age: 67.22 years | Needs and unmet needs during the pandemic – semistructured interviews Interviews conducted between March and April 2020 |

| Janiri et al. (2020)20 | Italy | 134 | Not reported | Lifetime psychiatric symptoms – semistructured interview; Disease severity – Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale; Impact of social restrictions on psychiatric burden – semistructured interview Measures taken in April 2020 |

| Kapel et al. (2021)42 | Slovenia | 42 | Gender not reported, mean age not reported, age range: 41–78 years | Motor state, use of orthopaedic props, deteriorations and reduction in motor functions, fall incidence, hospital admissions, impact of hand-on therapy absence, gait, sleep, behaviour disorders – study-specific questionnaire in the seventh week of restrictions |

| Kitani-Morii et al. (2021)30 | Japan | 39 patients vs. 32 controls (caregivers) | Patients: 35% women; mean age: 72.3 years Controls: 84% women; mean age: 66.4 years |

Depression – Patient Health Questionnaire 9; Anxiety – Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7; Insomnia – Insomnia Severity Index; Subjective motor experiences of daily living – Movement Disorder Society Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale Measures taken between April and May 2020 |

| Kumar et al. (2020)28 | India | 832 | 31.5% women, 83.8% aged 50 years or older (mean not reported) | Worsening of symptoms and quality of life – study-specific survey Measures taken between May and July 2020 |

| Oppo et al. (2020)21 | Italy | 32 patients; 32 caregivers | PwPD: 25% women, mean age: 72.5 years Caregivers: 81.2% women, mean age: 64.63 years |

Aspects of Parkinson's disease – Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale Part II; Non-motor symptoms – Non-motor Symptoms Scale; Impulsive compulsive disorders – Questionnaire for Impulsive-Compulsive Disorders in Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale; Quality of life – Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire 8; Anxiety and depression – Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (both caregivers and patients); Caregivers also completed the Zarit Burden Interview Measures taken during the last 10 days of Italy's lockdown |

| Palermo et al. (2020)22 | Italy | 28 | Not reported | Mental state – Mini Mental State Examination Measures taken between June and July 2020 and compared with the last prelockdown clinical assessment from January to February 2020 |

| Piano et al. (2020)23 | Italy | 90 | 36% women, mean age: 62 years | Concomitant diseases and disability measures – Activities of Daily Living and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scales, Hoehn and Yahr scale for patients with PD, Clinical Global Impression Severity Scale; Effects of COVID-19 lockdown – study-specific survey and CGI Improvement Scale Measures taken between April and May 2020 |

| Prasad et al. (2020)29 | India | 100 patients vs. 100 caregivers | Patients: 30% women, mean age: 58.06 years Caregivers: 49% women, mean age: 44.14 years |

Perceptions and implications of COVID-19 – study-specific questionnaire Measures taken after 3 weeks of lockdown |

| Salari et al. (2020)38 | Iran | 137 patients vs. 95 caregivers vs. 442 controls | Patients: 65.7% women, mean age: 55 years Caregivers: 74.7% women, mean age: 43 years Control’s age and gender matched to patients |

Anxiety – Beck Anxiety Inventory II-Persian Not reported when measures were taken; however, study was published in May 2020 |

| Santos-Garcia et al. (2020)44 | Spain | 568 | 53% women, mean age: 63.5 years | Quality of life, Parkinson's disease variables, knowledge and impact of COVID-19, role and strain of caregiver – study-specific questionnaire Measures taken between May and July 2020 |

| Say et al. (2020)33 | Turkey | 86 | 30.23% women, mean age: 71.15 years | COVID-19 knowledge, compliance with preventive measures, risk perception, history of COVID-19, impact of the pandemic on medical adherence, new or worsening of PD symptoms – study-specific survey Measures collected after 3 months of home quarantine |

| Schirinzi et al. (2020a)24 | Italy | 162 | 54% women, mean age: 64.9 years | Relationship between COVID-19 and PD, acute changes in neurological symptoms, occurrence of intercurrent medical conditions, clinical services – descriptive analysis of emails, texts and voice messages sent spontaneously from PwPD or their caregivers to a PD clinic during the first 3 weeks of lockdown in March 2020 |

| Schirinzi et al. (2020b)25 | Italy | 74 | Not reported | Motor activity habits before pandemic, type and frequency of physiotherapy/rehabilitation exercise, motor activity habits during lockdown, type of exercise done during lockdown, use of technology-based tools and wearable devices, perception of health during pandemic – study-specific questionnaire; Intensity of physical activity – International Physical Activity Questionnaire; Clinical severity of PD symptoms – Parkinson's Well-Being Map; Depression – Beck Depression Inventory Measures taken during April–May 2020 |

| Shalash et al. (2020)36 | Egypt | 38 patients vs. 20 controls | Patients: 23.7% women; mean age: 55.58 years Controls: 30% women; mean age: 55.56 years |

Perception of the impact of COVID-19 – study-specific scale; Depression, anxiety and stress – Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale-21; Physical activity – short form of the international physical activity questionnaire; PDQ39 Not reported when measures were taken; however, study published in May 2020 |

| Song et al. (2020)43 | South Korea | 100 | 46% women, mean age: 70 years | Motor symptoms – UPDRS Part 3; General cognition – MMSE; Subjective changes in PD symptoms – study-specific questionnaire; Activities of daily living – Schwab and England Scale of Activities of Daily Living; Amount of exercise – Physical Activity Scale of the Elderly; Participants also asked whether their amount of exercise was reduced due to the pandemic Measures taken in May 2020 and compared with baseline data from December 2019 to January 2020 |

| Suzuki et al. (2021)31 | Japan | 100 patients vs. 100 caregivers | Patients: 55% women, mean age: 72.2 years Caregivers: 53% women, mean age: 65.5 years |

Anxiety and depression – Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; Changes in motor symptoms, sleep and mood since the pandemic – Patient Global Impression of Change Scale; Health-related quality of life – the physical component summary and mental component summary of the short-form SF-8 Measures taken between June and December 2020 |

| Templeton et al. (2021)35 | USA | 28 | 53.57% women, age range: 52–84 years (mean not reported) | Quality of life activity levels and symptom changes since the pandemic – study-specific questionnaire Participants asked to rate before Parkinson's disease diagnosis, after diagnosis and after the 4-month stay-at-home mandate |

| Thomsen et al. (2021)46 | Denmark and Sweden | 67 | 47.8% women; median age: 70 years, mean not reported | Health-related quality of life – Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire-8 or Patient Reported Outcome in Parkinson's disease; Depression – Beck Depression Scale; Apathy – Lille Apathy Rating Scale; How the pandemic had influenced everyday life – free-text question Measures taken at baseline (2017), pre-COVID (2018) and during COVID (April–June 2020) |

| Van der Heide et al. (2020)41 | Netherlands | 358 | 38.5% women, mean age: 62.8 years | Stress – Perceived Stress Scale; Parkinson's symptom severity – Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale; Anxiety – Parkinson Anxiety Scale; Brooding – brooding subscale of the Ruminative Response Scale; Change in Parkinson's symptoms – study-specific question; Social support – SOZU-K-10; Resilience – Brief Resilience Scale; Neuroticism – subscale of the Big Five Inventory; Positive appraisal and behavioural coping – COPE and Cognitive Emotion Regulation Questionnaire Measures taken between April and May 2020 |

| Xia et al. (2020)27 | China | 119 patients vs. 169 controls | Patients: 48.7% women, mean age: 61.18 years Controls matched for age and gender |

Sleep quality – Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; Psychological distress – Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; Impact of pandemic on life – study-specific questions Measures completed in April 2020 and retrospectively assessed sleep and mental health status between February and April 2020 |

| Yule et al. (2021)45 | UK | 167 patients vs. 51 controls | 52.09% men, 47.30% women and 0.59% who preferred to self-describe gender, mean age: 66.0 years | Impulse control behaviours – Questionnaire for Impulsive-Compulsive Disorders in Parkinson's Disease; Anxiety – State Trait Anxiety Inventory; Impulsivity – Barratt Impulsiveness Scale; Apathy – Starkstein Apathy Scale; Quality of life – Parkinson's Disease Questionnaire-8; Experiences during the pandemic – open questions Measures taken pre-pandemic and during the March–June 2020 lockdown |

| Zipprich et al. (2020)37 | Germany | 99 patients vs. 21 controls | 35.4% women, median age: 72 years | Knowledge, attitudes, practices and burden associated with COVID-19 preventive measures – semistructured interviews Measures taken in April 2020 |

PwPD, people with Parkinson's disease.

MDS-UPDRS, Movement Disorder Society-Sponsored Revision of the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale; MMSE - Mini Mental State Examination, PD, Parkinson's disease; UPDRS - Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale.

Thematic analysis revealed six main themes: impact of the pandemic on physical and mental health; COVID-19 concerns; access to health care; impact on daily and social activities; impact on physical activity and impact on caregivers.

Impact of the pandemic on physical and mental health

In one study, 28% of 162 communications to a Parkinson's clinic were about acute clinical worsening.24 Worsening of global health was reported in almost every study, with the percentage of affected participants ranging from 11%29 to 90.4%.42 Parkinson's disease symptoms emerged or worsened in all domains (motor, mood, cognitive, sleep and automatic). The motor symptom most frequently exacerbated by the pandemic was bradykinesia (slowness of movement).32 , 33 , 43 , 44 Others included tremors,41 , 43 general motor function,35 , 42 rigidity,41 and increase in falls.42 Non-motor symptoms which worsened included fatigue,28 , 33 , 41 , 43 pain,33 , 41 , 43 speech,35 impulse control behaviours,23 , 45 behaviour disorders,42 daytime sleepiness,33 memory,22 , 28 aggressive or impulsive behaviour28 and concentration.22 , 41 Increases in sleep disturbances,17 , 20 , 23 , 27 , 28 , 34 , 35 , 42 anxiety,22 , 28 , 30 depression,20 , 23 , 28 feeling stressed43 and loss of motivation42 were also noted.

PD symptoms were more likely to emerge or worsen in PwPD with depression,25 high perceived stress,41 more severe symptoms before the pandemic,41 pre-existing cognitive impairment,17 lower physical activity intensity,25 , 47 younger PwPD,20 women,30 those who had changed medication during the pandemic26 and those who experienced medical care interruptions.26 , 47 The mental health impact of the pandemic was reported to be worse for women,18 , 20 , 27 , 30 , 31 , 34 those with longer disease duration,31 those with prepandemic mental health problems,18 those with comorbid chronic medical conditions,38 those who caught COVID-19,38 White ethnicity,34 lower household income,34 those with worsening neurological symptoms,20 those with reduced physical activity,34 and those with higher disease severity.18 In other studies, symptom worsening was not associated with age, age at onset of PD, gender or disease duration25 or experiencing symptoms of COVID-19.23

One study46 found that some aspects of health-related quality of life of PwPD improved during the pandemic such as sleep, concentration and being able to get around in public places. Participants indicated that this was due to not having usual social pressures, enjoying life being simple and slow and enjoying being at home. Other studies found no significant worsening of mental health problems,22 , 40 or only a minority of participants reporting worsening mental health symptoms.19 , 29

COVID-19 concerns

Worsening of mental health symptoms was often attributed by participants to the pandemic.36 Many reported greater stress during home confinement21 and dissatisfaction with their quality of life during home confinement.28 Participants reported that their emotional well-being was negatively affected by physical distancing and restricted communication with usual contacts,34 , 37 , 39 death or illness of family members and non-adherence to hygiene measures by healthcare professionals.39 Participants reported various other concerns about the pandemic, particularly fear of infection,28 , 34 , 37 , 39 as well as fear of requiring intensive hospital care if they were to become infected,34 general uncertainty about the situation37 and economic and social changes.37

Perceived COVID-19 risk differed across studies: in some, the vast majority of participants saw COVID-19 as dangerous33 , 37 and were more likely to view the pandemic as a threat than healthy controls37 because they saw themselves as being particularly at risk of infection.34 , 37 Other studies reported lower perception of risk.29 Participants reported taking various precautions, such as cancelling social activities,34 , 37 staying at home,33 , 37 avoiding public spaces,34 washing hands more often,33 stocking up on medications,34 praying34 and wearing face coverings.33 , 34 , 37

Access to health care

Many studies reported that PwPD experienced disruption to usual medical care such as discontinuation of usual healthcare visits,23 , 28 , 36 , 37 , 39 , 47 reduced in-home care47 and difficulty obtaining medications.23 , 28 , 39 , 47 Some participants cancelled appointments themselves due to fears of becoming infected with COVID-19 by attending the appointments,34 while others had no way of getting to their appointments due to lack of transportation.28

In some studies, most participants experienced this disruption,23 , 25 whereas others reported only a minority did.29 , 31 Only one study18 found no reported treatment changes at all. Loss of access to health care was reported to be a source of stress by participants37 and was significantly associated with worsening motor and psychiatric symptoms.23 , 47 Concerns about drug availability were associated with anxiety38 and difficulties in daily living.36

One study47 found that disruption to care was more likely in those with longer (9+ years) duration of PD, non-White participants and participants of lower income; additionally, people of Latinx ethnicity reported greater difficulty obtaining medication.

Impact on daily and social activities

Participants in many studies reported loss of daily activities, including outdoor activities, social activities and obtaining food,17 , 23 , 26 , 34 , 37 , 41 , 43 , 47 which were significantly associated with worsening psychiatric symptoms.23 Patients who experienced interruptions to social activities or were asked to self-isolate were more likely to report worsening of PD symptoms.47 In Thomsen et al.’s46 study, participants attributed anxiety symptoms to the perception of having to reconstruct normal life and adapt to new routines.

Many participants felt being restricted to the home and losing social contacts were stressful.41 , 46 They reported needing increased support to cope with the consequences of the pandemic.39 Lack of support appeared to be associated with poor well-being.40 , 41 PwPD felt particularly stressed by lack of contact with grandchildren37 and being restricted in visiting loved ones in hospital or not being able to attend the funeral of a loved one.41

Impact on physical exercise

Some studies found no change in physical activity25 , 28 or a small minority reporting loss of physical activities.29 In Templeton et al.’s35 study, PwPD reported minimal change in the number of active days per week but a notable decrease in the number of active minutes per day and number of total activities due to restrictions. Other studies found that between a quarter44 and almost three quarters36 of participants reported a reduction in amount, duration or frequency of physical activity. One study found physical activity during the pandemic was low for both patients and controls,32 whereas another found that PwPD had significantly less physical activity than controls.36 Reduced activity was attributed to both closing of sports facilities and concerns about contracting COVID-19 when going out for exercise.43

Participants were concerned about the consequences of reduced physical activity.39 Not being able to perform usual physical activities was reported by PwPD to have a negative effect on well-being,41 and PwPD who experienced interruptions to exercise were more likely to report worsening of PD symptoms.25 , 41 , 43 , 47 PwPD practising daily physical activity had significantly lower anxiety and depression scores than those who were inactive.21

Impact on caregivers

A small number of studies also considered the impact of the pandemic on caregivers of PwPD. One study found that caregivers reported less severe anxiety than PwPD but significantly higher anxiety than controls;38 others found no difference in the proportion of PwPD and caregivers with worsened depression or anxiety30 , 31 and another found that stress during home confinement increased more for caregivers than PwPD.21 Caregiver strain was significantly higher in caregivers of PwPD with more complex needs, such as mild cognitive impairment,17 greater disease severity,18 , 21 depression,18 , 21 anxiety,21 fatigue,18 worsening of mood,31 poor quality of life and difficulties coping with daily life.18

Discussion

This review is the first to synthesise data on the burden of the COVID-19 pandemic on PwPD. Overall, the data suggest that due to the pandemic and associated restrictions, many have experienced worsening PD symptoms and mental health, perhaps due to changes in medical care, daily activities, social support or physical activity. Although the studies included in this review did not compare PwPD with people with other chronic conditions, it is likely that other groups may have similar experiences. For example, the results of this review are similar to those of a scoping review of people with Alzheimer,48 which found similar negative impacts on neuropsychiatric symptoms and cognitive function, disruption of services and support and impact on caregivers.

Worsening of motor symptoms is often associated with worsening psychological symptoms; it is unclear from the data if these occur simultaneously or if one happens first and impacts the other. What is clear is that during the COVID-19 pandemic and indeed any future pandemics, it is important that PwPD do not lose access to their medical care. In addition, loss of daily activities, social support or physical activity could impact mental health and lead to worsening of symptoms; so, it is important that PwPD maintain these as much as they can. Some studies in our review found that PwPD had changed their behaviours to stay at home and avoid face-to-face contact entirely, despite PwPD not being instructed to ‘shield’ – this could come at a cost to their mental health, as evidence suggests that older adults who self-isolate during the pandemic experience higher levels of depression, anxiety and loneliness.49

Telemedicine may be a promising avenue for consideration to ensuring continuity of care, representing a potential solution to the difficulties in accessing regular health care and physiotherapy reported by participants across studies. Preliminary studies suggest PwPD are open to the idea of telemedicine but may be less inclined if they are not used to using technology such as smartphones.50 Given the importance of physical exercise, telehealth to encourage appropriate physical activity, such as telerehabilitation and apps encouraging patient-initiated exercises, could be helpful.51 , 52 Healthcare professionals and caregivers should promote home-based exercises for PwPD during the pandemic; these have previously been found to improve quality of life for PwPD53 and would be particularly beneficial during the pandemic. Doing home-based exercises remotely with a group (e.g. online or via video calls) could increase sense of socialisation in addition to providing the usual benefits of physical activity.54

The importance of social networks and connectedness has been well documented,55 , 56 and previous research highlights the importance of this for the mental health of PwPD,57 but the restrictions of the pandemic may lead to people feeling socially isolated. It is important that PwPD maintain informal support networks during the pandemic, for example, by communicating virtually with friends and family. It may also be helpful for PwPD to join virtual support groups as a way of developing relationships with others with the same condition and sharing experiences, advice or encouragement. Support groups have previously been shown to be associated with better mental health and quality of life in PwPD.8

To minimise pandemic-related concerns, it is important for PwPD to receive appropriate, timely information not only about COVID-19 itself but also about their medical care during the pandemic and any changes to usual services.24 It would also be useful for PwPD to receive information about self-care during the pandemic, with advice for staying active, reminders about keeping in contact with friends, suggestions for keeping occupied and cognitively engaged and tips for coping effectively during a stressful time. This could be in the form of leaflets or information on healthcare providers’ websites.

Thus far, one article has been published on a potential intervention to support PwPD during the pandemic:58 an outreach programme involving a nurse and licenced clinical social worker proactively calling vulnerable or high-risk patients to carry out a needs assessment and provide appropriate resources or referrals tailored to each individual, such as safety tips, exercise videos, relaxation resources and contact information for support helplines. Although no formal evaluation of the programme has been published, the authors report that initial feedback from PwPD and caregivers has been extremely positive. However, formal evaluation is required before any firm supportive recommendation could be made.

It is important for further studies to examine the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on PwPD, particularly in countries who experienced further waves of the virus and consequently extended lockdowns and social restrictions. More research on the effectiveness of telehealth for the management of PD, as well as how to ensure all PwPD have access to telehealth and can be encouraged to use it, is also necessary. It may be helpful to further investigate potential sociodemographic predictors of symptom worsening and poor mental health in PwPD during the pandemic. It was concerning that one study suggested differences in ethnicity and income in terms of access to health care; this needs to be investigated further to establish what inequalities exist and how these can be reduced.

Limitations

The included studies were carried out near the beginning of the pandemic when restriction periods were relatively short. The impact of the pandemic may be felt more severely by PwPD now that the pandemic has been going on for more than a year and restrictions are still in place in many countries. It would be useful to update this review in the future when more longitudinal studies have been published.

Although a wide variety of countries were represented by the studies reviewed, it is possible that the decision to limit to English language articles may mean that important studies were missed. Relevant articles could potentially have been missed due to the search terms we used and the decision to limit the searches to five databases; future reviews may consider searching a wider variety of databases, including grey literature, and using a wider variety of search terms.

Although the search was limited to articles published in journals and all had presumably been subject to Editor review, a minority of the included articles were published as rapid communications which appear to have been published within days of submission, and we acknowledge that these may not have undergone a rigorous peer review process.

Only one author screened articles and extracted data. Ideally, a second reviewer would carry out their own independent screening to ensure all relevant articles are included.

Conclusion

The social restrictions many countries have put in place have led to many challenges for PwPD such as loss of usual daily activities, social contact, physical exercise and health care, as well as new or worsening Parkinson's disease symptoms. In addition, caregivers appear to be under increased strain, particularly caregivers of PwPD with complex needs. Although some positive effects of the pandemic have been noted – such as enjoyment of life being quieter and slower – these appear to be a minority. This review suggests a number of potential ways of supporting PwPD during the pandemic including telemedicine to ensure access to health care is maintained, ensuring PwPD maintain contact with friends and family virtually, encouraging PwPD to do home-based exercises, virtual support groups and advice on self-care and effective coping strategies. We suggest further work is needed to identify which of these interventions is most promising and to develop more.

Author statements

Ethical approval

Not required; no primary data collected.

Funding

S.K.B., D.W. and N.G. are part funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Protection Research Unit (NIHR HPRU) in Emergency Preparedness and Response, a partnership between Public Health England, King's College London and the University of East Anglia. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR, Public Health England or the Department of Health and Social Care. D.W. is also a member of the NIHR Health Protection Research Unit in Behavioural Science and Evaluation at University of Bristol. The funding source had no involvement in study design; collection, analysis or interpretation of data; writing the report or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests

None declared.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2021.08.014.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Worldometers . 2021. COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic.https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ Available online: [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brooks S.K., Webster R.K., Smith L.E., Woodland L., Wessely S., Greenberg N., Rubin G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Helmich R.C., Bloem B.R. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Parkinson's disease: hidden sorrows and emerging opportunities. J Parkinsons Dis Print. 2020;10(2):351–354. doi: 10.3233/JPD-202038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhaskar S., Bradley S., Israeli-Korn S., Menon B., Chattu V.K., Thomas P., et al. Chronic neurology in COVID-19 era: clinical considerations and recommendations from the REPROGRAM consortium. Front Neurol. 2020;11:13. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kostick K., Storch E.A., Zuk P., et al. Strategies to mitigate impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on patients treated with deep brain stimulation. Brain Stimul. 2020;13(6):1642–1643. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2020.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheong J.L.Y., Goh Z.H.K., Marras C., Tanner C.M., Kasten M., Noyce A.J., Movement Disorders Soc, E. The impact of COVID-19 on access to Parkinson's disease medication. Mov Disord. 2020;35(12):2129–2133. doi: 10.1002/mds.28293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Papa S.M., Brundin P., Fung V.S.C., Kang U.J., Burn D.J., Colosimo C., et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Parkinson's disease and movement disorders. Mov Disord. 2020;35:711–715. doi: 10.1002/mds.28067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karlsen K.H., Larsen J.P., Tandberg E., Maeland J.G. Influence of clinical and demographic variables on quality of life in patients with Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66(4):431–435. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.66.4.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Artigas N.R., Striebel V.L.W., Hilbig A., Rieder C.R.M. Evaluation of quality of life and psychological aspects of Parkinson's disease patients who participate in a support group. Dement Neuropsychol. 2015;9(3):295–300. doi: 10.1590/1980-57642015DN93000013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Subramanian I., Farahnik J., Mischley L.K. Synergy of pandemics-social isolation is associated with worsened Parkinson severity and quality of life. Npj Parkinsons Dis. 2020;6(1):8. doi: 10.1038/s41531-020-00128-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haslam C., Alexander Haslam S., Knight C., Gleibs I., Ysseldyk R., McCloskey L.-G. We can work it out: group decision-making builds social identity and enhances the cognitive performance of care residents. Br J Psychol. 2014;105:17–34. doi: 10.1111/bjop.12012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rickards H. Depression in neurological disorders: Parkinson's disease, multiple sclerosis, and stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 2005;76:i48–i52. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.060426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Broen M.P., Narayen N.E., Kuijf M.L., Dissanayaka N.N., Leentjens A.F. Prevalence of anxiety in Parkinson's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mov Disord. 2016 Aug;31(8):1125–1133. doi: 10.1002/mds.26643. Epub 2016 Apr 29. PMID: 27125963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lo Monaco M.R., Di Stasio E., Zuccalà G., Petracca M., Genovese D., Fusco D., Silveri M.C., Liperoti R., Ricciardi D., Cipriani M.C., Laudisio A., Bentivoglio A.R. Prevalence of obsessive-compulsive symptoms in elderly Parkinson disease patients: a case-control study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2020 Feb;28(2):167–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2019.08.022. Epub 2019 Aug 29. PMID: 31558346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arksey H., O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baschi R., Luca A., Nicoletti A., Caccamo M., Cicero C.E., D'Agate C., et al. Changes in motor, cognitive, and behavioral symptoms in Parkinson's disease and mild cognitive impairment during the COVID-19 lockdown. Front Psychiatr. 2020;11:10. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.590134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Micco R., Siciliano M., Sant'Elia V., Giordano A., Russo A., Tedeschi G., Tessitore A. Correlates of psychological distress in patients with Parkinson's disease during the COVID-19 outbreak. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2021;8(1):60–68. doi: 10.1002/mdc3.13108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Del Prete E., Francesconi A., Palermo G., Mazzucchi S., Frosini D., Morganti R., et al. Prevalence and impact of COVID-19 in Parkinson's disease: evidence from a multi-center survey in Tuscany region. J Neurol. 2021;268(4):1179–1187. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-10002-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janiri D., Petracca M., Moccia L., Tricoli L., Piano C., Bove F., et al. COVID-19 pandemic and psychiatric symptoms: the impact on Parkinson's disease in the elderly. Front Psychiatr. 2020;11:8. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.581144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oppo V., Serra G., Fenu G., Murgia D., Ricciardi L., Melis M., et al. Parkinson's disease symptoms have a distinct impact on caregivers' and patients' stress: a study assessing the consequences of the COVID-19 lockdown. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2020;7(7):865–867. doi: 10.1002/mdc3.13030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palermo G., Tommasini L., Baldacci F., Del Prete E., Siciliano G., Ceravolo R. Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on cognition in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2020;35(10):1717–1718. doi: 10.1002/mds.28254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Piano C., Bove F., Tufo T., Imbimbo I., Genovese D., Stefani A., et al. Effects of COVID-19 lockdown on movement disorders patients with deep brain stimulation: a multicenter survey. Front Neurol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.616550. (no pagination) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schirinzi T., Cerroni R., Di Lazzaro G., et al. Self-reported needs of patients with Parkinson's disease during COVID-19 emergency in Italy. Neurol Sci. 2020;41(6):1373–1375. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04442-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schirinzi T., Di Lazzaro G., Salimei C., Cerroni R., Liguori C., Scalise S., et al. Physical activity changes and correlate effects in patients with Parkinson's disease during COVID-19 lockdown. Mov Disord Clin Pract. 2020;7(7):797–802. doi: 10.1002/mdc3.13026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo D., Han B., Lu Y., Lv C., Fang X., Zhang Z., et al. Influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on quality of life of patients with Parkinson's disease. Parkinsons Dis. 2020;2020:1216568. doi: 10.1155/2020/1216568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xia Y., Kou L., Zhang G.X., Han C., Hu J.J., Wan F., et al. Investigation on sleep and mental health of patients with Parkinson's disease during the Coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Sleep Med. 2020;75:428–433. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar N., Gupta R., Kumar H., et al. Impact of home confinement during COVID-19 pandemic on Parkinson's disease. Park Relat Disord. 2020;80:32–34. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2020.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prasad S., Holla V.V., Neeraja K., et al. Parkinson's disease and COVID-19: perceptions and implications in patients and caregivers. Mov Disord. 2020;35(6):912–914. doi: 10.1002/mds.28088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kitani-Morii F., Kasai T., Horiguchi G., Teramukai S., Ohmichi T., Shinomoto M., et al. Risk factors for neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with Parkinson's disease during COVID-19 pandemic in Japan. PLoS One. 2021;16(1):13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suzuki K., Numao A., Komagamine T., Haruyama Y., Kawasaki A., Funakoshi K., et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the quality of life of patients with Parkinson's disease and their caregivers: a single-center survey in Tochigi Prefecture. J Parkinsons Dis. 2021:22. doi: 10.3233/JPD-212560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Balci B., Aktar B., Buran S., Tas M., Donmez Colakoglu B. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on physical activity, anxiety, and depression in patients with Parkinson's disease. Int J Rehabil Res. 2021;25 doi: 10.1097/MRR.0000000000000460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Say B., Ozenc B., Ergun U. Covid-19 perception and self reported impact of pandemic on Parkinson's disease symptoms of patients with physically independent Parkinson's disease. Neurol Asia. 2020;25(4):485–491. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feeney M.P., Xu Y.Q., Surface M., Shah H., Vanegas-Arroyave N., Chan A.K., et al. The impact of COVID-19 and social distancing on people with Parkinson's disease: a survey study. Npj Parkinsons Dis. 2021;7(1):10. doi: 10.1038/s41531-020-00153-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Templeton J.M., Poellabauer C., Schneider S. Negative effects of COVID-19 stay-at-home mandates on physical intervention outcomes: a preliminary study. J Parkinsons Dis Print. 2021;13:13. doi: 10.3233/JPD-212553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shalash A., Roushdy T., Essam M., Fathy M., Dawood N.L., Abushady E.M., et al. Mental health, physical activity, and quality of life in Parkinson's disease during COVID-19 pandemic. Mov Disord. 2020;35(7):1097–1099. doi: 10.1002/mds.28134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zipprich H.M., Teschner U., Witte O.W., Schonenberg A., Prell T. Knowledge, attitudes, practices, and burden during the COVID-19 pandemic in people with Parkinson's disease in Germany. J Clin Med. 2020;9(6):11. doi: 10.3390/jcm9061643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salari M., Zali A., Ashrafi F., Etemadifar M., Sharma S., Hajizadeh N., Ashourizadeh H. Incidence of anxiety in Parkinson's disease during the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. Mov Disord. 2020;35(7):1095–1096. doi: 10.1002/mds.28116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hanff A.M., Pauly C., Pauly L., et al. Unmet needs of people with Parkinson's disease and their caregivers during COVID-19-related confinement: an explorative secondary data analysis. Front Neurol. 2021;11:615172. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.615172. Published 2021 Jan 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.El Otmani H., El Bidaoui Z., Amzil R., Bellakhdar S., El Moutawakil B., Rafai M.A. No impact of confinement during COVID-19 pandemic on anxiety and depression in Parkinsonian patients. Rev Neurol. 2021;177(3):272–274. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2021.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van der Heide A., Meinders M.J., Bloem B.R., Helmich R.C. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on psychological distress, physical activity, and symptom severity in Parkinson's disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2020;10(4):1355–1364. doi: 10.3233/jpd-202251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kapel A., Serdoner D., Fabiani E., Velnar T. Impact of physiotherapy absence in COVID-19 pandemic on neurological state of patients with Parkinson disease. Top Geriatr Rehabil. 2021;37(1):50–55. doi: 10.1097/tgr.0000000000000304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Song J., Ahn J.H., Choi I., Mun J.K., Cho J.W., Youn J. The changes of exercise pattern and clinical symptoms in patients with Parkinson's disease in the era of COVID-19 pandemic. Park Relat Disord. 2020;80:148–151. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2020.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Santos-García D., Oreiro M., Pérez P., et al. Impact of coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on Parkinson's disease: a cross-sectional survey of 568 Spanish patients. Mov Disord. 2020;35(10):1712–1716. doi: 10.1002/mds.28261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yule E., Pickering J.S., McBride J., Poliakoff E. People with Parkinson's report increased impulse control behaviours during the COVID-19 UK lockdown. Park Relat Disord. 2021;86:38–39. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2021.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thomsen T.H., Wallerstedt S.M., Winge K., Bergquist F. Life with Parkinson's disease during the COVID-19 pandemic: the pressure is "OFF". J Parkinsons Dis. 2021;12 doi: 10.3233/JPD-202342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brown E.G., Chahine L.M., Goldman S.M., et al. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with Parkinson's disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2020;10(4):1365–1377. doi: 10.3233/JPD-202249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bacsu J.R., O'Connell M.E., Webster C., Poole L., Wighton M.B., Sivananthan S. A scoping review of COVID-19 experiences of people living with dementia. Can J Public Health. 2021;112(3):400–411. doi: 10.17269/s41997-021-00500-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Steptoe A., Steel N. 2020. The experience of older people instructed to shield or self-isolate during the COVID-19 pandemic.https://11a183d6-a312-4f71-829a-79ff4e6fc618.filesusr.com/ugd/540eba_55b4e2be5ec341e48c393bdeade6a729.pdf Available online: [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kurihara K., Nagaki K., Inoue K., Yamamoto S., Mishima T., Fujioka S., et al. Attitudes toward telemedicine of patients with Parkinson's disease during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neurol Clin Neurosci. 2021;9(1):77–82. doi: 10.1111/ncn3.12465. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Langer A., Gassner L., Flotz A., Hasenauer S., Gruber J., Wizany L., et al. How COVID-19 will boost remote exercise-based treatment in Parkinson's disease: a narrative review. Npj Parkinsons Dis. 2021;7(1):9. doi: 10.1038/s41531-021-00160-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Quinn L., Macpherson C., Long K., Shah H. Promoting physical activity via telehealth in people with Parkinson disease: the path forward after the COVID-19 pandemic? Phys Ther. 2020;100(10):1730–1736. doi: 10.1093/ptj/pzaa128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ashburn A., Fazakarley L., Ballinger C., Pickering R., McLellan L.D., Fitton C. A randomised controlled trial of a home based exercise programme to reduce the risk of falling among people with Parkinson's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78(7):678–684. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.099333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sahin S. Management of neurorehabilitation during the covid-19 pandemic. [Covid-19 pandemisi surecinde nororehabilitasyonun yonetimi.] Duzce Med J. 2020;22(Special Issue 1):10–13. doi: 10.18678/dtfd.775214. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alexander Haslam S. Unlocking the social cure. Psychologist. 2018;31:28–31. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wakefield J.R.H., Kellezi B., Stevenson C., et al. Social Prescribing as ‘Social Cure’: a longitudinal study of the health benefits of social connectedness within a Social Prescribing pathway. J Health Psychol. 2020 doi: 10.1177/1359105320944991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Simpson J., Haines K., Lekwuwa G., Wardle J., Crawford T. Social support and psychological outcome in people with Parkinson's disease: evidence for a specific pattern of associations. Br J Clin Psychol. 2006;45(Pt 4):585–590. doi: 10.1348/014466506X96490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sennott B., Woo K., Hess S., Mitchem D., Klostermann E.C., Myrick E., et al. Novel outreach program and practical strategies for patients with parkinsonism in the COVID-19 pandemic. J Parkinsons Dis. 2020;10(4):1383–1388. doi: 10.3233/jpd-202156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.