Abstract

Extrapulmonary sarcoidosis occurs in 30–50% of cases of sarcoidosis, most often in association with pulmonary involvement, and virtually any organ can be involved. Its incidence depends according to the organs considered, clinical phenotype, and history of sarcoidosis, but also on epidemiological factors like age, sex, geographic ancestry, and socio-professional factors. The presentation, symptomatology, organ dysfunction, severity, and lethal risk vary from and to patient even at the level of the same organ. The presentation may be specific or not, and its occurrence is at variable times in the history of sarcoidosis from initial to delayed. There are schematically two types of presentation, one when pulmonary sarcoidosis is first discovered, the problem is then to detect extrapulmonary localizations and to assess their link with sarcoidosis, while the other presentation is when extrapulmonary manifestations are indicative of the disease with the need to promptly make the diagnosis of sarcoidosis. To improve diagnosis accuracy, extrapulmonary manifestations need to be known and a medical strategy is warranted to avoid both under- and over-diagnosis. An accurate estimation of impairment and risk linked to extrapulmonary sarcoidosis is essential to offer the best treatment. Most frequent extrapulmonary localizations are skin lesions, arthritis, uveitis, peripheral lymphadenopathy, and hepatic involvement. Potentially severe involvement may stem from the heart, nervous system, kidney, eye and larynx. There is a lack of randomized trials to support recommendations which are often derived from what is known for lung sarcoidosis and from the natural history of the disease at the level of the respective organ. The treatment needs to be holistic and personalized, taking into account not only extrapulmonary localizations but also lung involvement, parasarcoidosis syndrome if any, symptoms, quality of life, medical history, drugs contra-indications, and potential adverse events and patient preferences. The treatment is based on the use of anti-sarcoidosis drugs, on treatments related to organ dysfunction and supportive treatments. Multidisciplinary discussions and referral to sarcoidosis centers of excellence may be helpful for difficult diagnosis and treatment decisions.

Keywords: Sarcoidosis, Extrapulmonary, Treatment, Diagnosis, Outcome, Monitoring, 18FFDG-PET

Key Summary Points

| In sarcoidosis patients, age, sex, ancestry, and geographical origin and also socio-professional category influencing the respective extrapulmonary localization occurrence. |

| Planning a correct work-up of pulmonary sarcoidosis diagnosis and during follow-up is essential for detecting extrapulmonary sarcoidosis involvement. |

| In patients with only extrapulmonary manifestations suggesting sarcoidosis, 18FFDG-PET may show a typical uptake in hilar or mediastinal lymphadenopathy and then one may be able to observe granulomas thanks to EBUS-TBNA. |

| In a patient diagnosed with sarcoidosis, it is important to balance arguments for and against a link between any extrapulmonary manifestation and sarcoidosis. |

| Severe cardiac, neurological, renal, and eye localizations can be seen at sarcoidosis onset, while cardiac or renal localizations may also appear later. |

| Extrapulmonary sarcoidosis care is based on disease-modifying drugs, organ-directed treatments, and supportive treatments to improve organ dysfunction risks and quality of life, and needs to be holistic, personalized, and in line with patient expectations. |

Introduction

Sarcoidosis is a systemic disease of unknown cause characterized by granuloma formation in various organs which exhibits a spectrum of manifestations from asymptomatic to progressive and relapsing [1–3]. The lung is affected in 83.6–91.7% of patients [4–6] and represents the most important cause of morbidity and mortality in Western countries [7, 8]. Sarcoidosis may also involve any extrapulmonary organ with a prevalence varying according to the organ considered, clinical phenotype, and history of the disease, and also, sex, age, geographical origin, ethnicity, and socio-professional factors. Involvement of an organ may impair its function, generate symptoms, be life-threatening, impact negatively on the quality of life [9], and may require treatment .

Extrapulmonary sarcoidosis raises several specific important issues which need to be overcome to optimize patient care. Sarcoidosis may be revealed by pulmonary as well as extrapulmonary manifestations, which may or may not be obvious, typical, easy to biopsy, or severe. To tackle these multiple possible situations, this review aims at displaying the following points:

What are the epidemiology and history of extrapulmonary manifestations?

For patients with confirmed pulmonary sarcoidosis, how to appropriately screen extrapulmonary localizations at diagnosis work-up and during follow-up and assess their sarcoidosis origin?

For patients with initial extrapulmonary manifestations, how to look for criteria for a confident sarcoidosis diagnosis?

In all cases, how to assess the clinical impact of extrapulmonary localizations on symptoms, organ function, follow-up, and treatment management [10, 11]?

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

What are the Epidemiology and History of Extrapulmonary Manifestations?

Epidemiology

Studies from two multicenter studies, one in the US and one in Europe, and from a large monocentric study in Spain demonstrated the prevalence of respective organ involvement in sarcoidosis patients [4–6]. Extrapulmonary sarcoidosis is observed in about 30–50% of patients. The most frequent extrapulmonary localizations are skin (15.9–16.4%), peripheral lymph nodes (11.3–15.2%), eye (6.9–11.8%), and liver (2.5–11.5%). Some localizations may have a severe impact, i.e., with organ dysfunction or risk of premature death, mainly on the heart, central nervous system, kidney, larynx, and eye. The age, sex, ancestry, geographical origin, and socio-professional category influence the occurrence of the different extrapulmonary localizations [12]. Extrapulmonary sarcoidosis is more frequent in African-Americans than in Caucasians and in females than in males [9]. Peripheral lymphadenopathies are more frequent before than after the age of 40 [4, 9]. Females are more likely to have eye or neurologic involvement, while black patients are more prone to skin, liver, bone marrow, and lymph node involvement [4]. In the Japanese, cardiac and eye localizations are particularly frequent. Interestingly, the prevalence of the respective localizations varies according to clinical phenotypes [5, 12]. For example, a renal involvement is significantly more frequent in abdominal or extrapulmonary phenotypes than in other phenotypes [5]. Organ involvement is also influenced by the disease onset, either acute or not. Arthritis and musculoskeletal involvement are more frequent in acute presentation, while peripheral lymph nodes, cardiac, hepatic, and splenic localizations are more frequent in subacute presentations [5]. In non-pulmonary sarcoidosis, skin, upper respiratory tract, parotid/salivary, and bone marrow involvements are more frequent than in sarcoidosis with pulmonary involvement [13].

History of Extrapulmonary Sarcoidosis

Extrapulmonary localizations are most often discovered during the diagnosis work-up of a pulmonary sarcoidosis. Extrapulmonary sarcoidosis may also precede or prompt the discovery of thoracic involvement; more rarely, it may be delayed, sometimes by several years, in patients being followed for pulmonary sarcoidosis. Eventually, in 8.3% of patients, the disease remains purely non-pulmonary, without imaging or any other manifestation indicative for lung involvement [6, 13]. The various extrapulmonary localizations may occur at different times. Therefore, it is important to know when to expect their occurrence and, most important, how not to miss them. It is well known that the extension in the number of involved organs increases more in patients with more than three organs involved at onset [14]. Planning a correct work-up at diagnosis and during follow-up is essential for detecting extrapulmonary sarcoidosis involvement. At diagnosis, every patient with sarcoidosis needs, in addition to pulmonary investigations, a thorough clinical examination including a careful analysis of all symptoms (e.g., nasal obstruction or crusting, polyuria, or amenorrhea, etc.), an electrocardiogram (ECG), a specialized ophthalmological consultation including a slit-lamp examination, and biological tests including blood cell count, creatininemia, liver biological tests, in particular alkaline phosphatase, and calcemia [3, 15] (Table 1). For the scheduling of follow-up visits, guidelines have been recently proposed [3]. Some of the points concerning the follow-up schedule may be debatable, since they rely only on clinical experience. In our practice, we follow the monitoring program guidelines except for systematically planning an ECG every 6–12 months (due to the possibility of the progression of a silent atrio-ventricular block), and calcemia and creatininemia every 6 months (due to the risk of rapid fibrosis in renal sarcoidosis).

Table 1.

Scheduled investigations at work-up at diagnosis and during follow-up visits

| Work-up at diagnosis | Follow-up visits | |

|---|---|---|

| Careful analysis of symptoms | + | + (3–6 months) |

| Thorough clinical examination | + | + (3–6 months) |

| Electrocardiogram | + | Only when clinical signs |

| Ophthalmologic examination | + | Only when clinical signs |

| Calcium; renal and liver function; creatine phosphokinase | + | + serum calcium, creatinine and alkaline phosphatase every 12 months |

| Antero-posterior chest roentgenography; spirometry; DLCO | + | + chest roentgenogram every 3–6 months and spirometry every 3–6 months; DLCO every 6–12 months when abnormal at diagnosis and only every 12 months in non-pulmonary sarcoidosis |

| Parasarcoidosis syndrome search | + (with measure of Fatique Assessment Scale) | + |

| Quality of life assessment | + | + |

| Othersa | According to context | According to initial presentations and treatments |

| Conclusion | Organ dysfunction? Mortality risk? Impaired quality of life? Treatment indication | Improvement? Progression? New involvement? Response to treatment? |

The part highlighted in bold in the table was inspired by Crouser et al. [3]

aDepends upon manifestations observed (e.g., need for magnetic resonance imaging for suspicion of cardiac or central nervous sarcoidosis)

Besides erythema nodosum, which is not a granulomatous manifestation of sarcoidosis, the most frequent extrapulmonary localizations at onset are specific granulomatous skin lesions, arthritis, uveitis, peripheral lymphadenopathy and liver involvement. Some lesions are usually delayed several years after onset, like lupus pernio, muscular involvement, and dactylitis. Severe cardiac, neurological, renal, and eye localizations can be seen at onset, while cardiac or renal localizations may also appear later, even when sarcoidosis seems to be controlled at the level of already identified localizations.

Diagnosis of Extrapulmonary Organ Sarcoidosis

The great variability in presentation adds to diagnosis uncertainty, as there is no satisfying final criteria for sarcoidosis diagnosis [3]. Moreover, alternative diagnoses or comorbidities may be very confusing and avoiding missing of significant extrapulmonary localizations or their over-diagnosis is mandatory. Such a diagnostic process is usually carried out in two different contexts: (1) in patients with confirmed pulmonary sarcoidosis and (2) in patients with extra-pulmonary involvements indicative of the disease. In such contexts, due attention should be paid to rule out any alternative diagnosis with a similar presentation as recently rightly pointed out in the Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline on sarcoidosis diagnosis [3]. As computed tomography (CT) and 18Ffluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET)/CT expose patients to radiation, their use needs to be justified. A reduced tube current is feasible for CT with satisfying diagnostic performances [16]. 18FFDG PET/CT should be reserved to appropriate cases where diagnosis or treatment decisions are difficult and can benefit from it [2]. The repetition of these investigations should be exceptional.

Patients with Confirmed Pulmonary Sarcoidosis

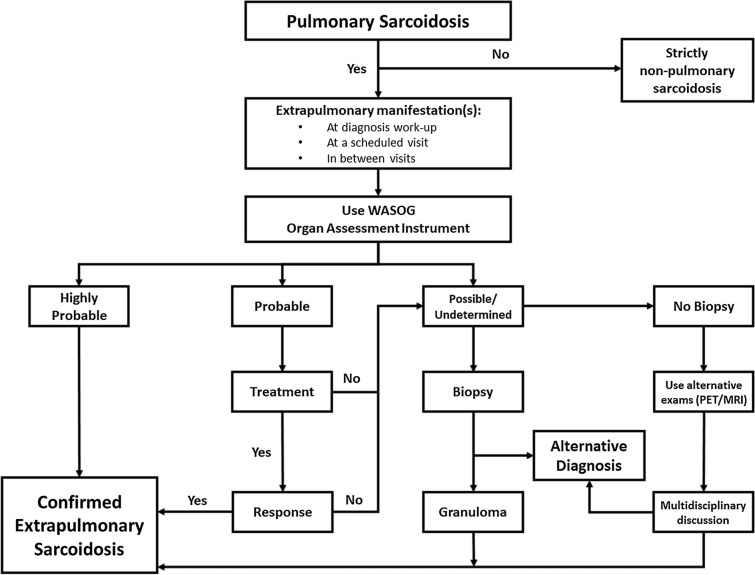

A well-planned work-up at diagnosis and during follow-up including consideration paid to any medical event between two visits, which necessitates correct information to patients, are essential (Table 1). However, “all that glitters in not gold”, and sarcoidosis is not the cause of all extrapulmonary findings occurring during its course. Thus, it is important to balance arguments for and against a link between a manifestation and sarcoidosis (Fig. 1), and any alternative hypothesis, infectious or non-infectious, needs to be ruled out [3]. For some findings, such a connection may be considered highly probable (> 90%) according to the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Diseases (WASOG) sarcoidosis organ assessment instrument, for example, lupus pernio, or uveitis, for which a direct link with an underlying sarcoidosis does not need to be supported by a biopsy [17]. Another piece of evidence is a conspicuous response to corticosteroids after 4 weeks of treatment at the lung level [18], while a no-response within this period implies the re-consideration of the supposed link between the localization and sarcoidosis, justifying further investigation. For some localizations, an extra-biopsy may be required, most often for suspicion of renal [19], sinonasal [20], laryngeal [21], muscular [22], bone marrow [23], and liver (according to context) [24] sites. However, for some organs, like the central nervous system or the heart, a biopsy is rarely carried out for three main reasons. First, to obtain a biopsy is not easy. Second, heart biopsy is often poorly sensitive and a negative biopsy does not rule out a cardiac sarcoidosis. And third, investigations like MR [3] and if necessary 18FFDG-PET in addition to other investigations, often offer a sufficient diagnosis accuracy [25, 26]. However, for all types of manifestations, any alternative diagnosis should be considered, taking account of the involved organ since alternative hypotheses may vary from site to site.

Fig. 1.

Diagnostic strategy for extrapulmonary sarcoidosis in patients with confirmed pulmonary sarcoidosis. WASOG sarcoidosis organ assessment Instrument according to [17]. MRI magnetic resonance imaging, PET positron emission tomography

Patients with Extrapulmonary Manifestations Indicative of the Disease

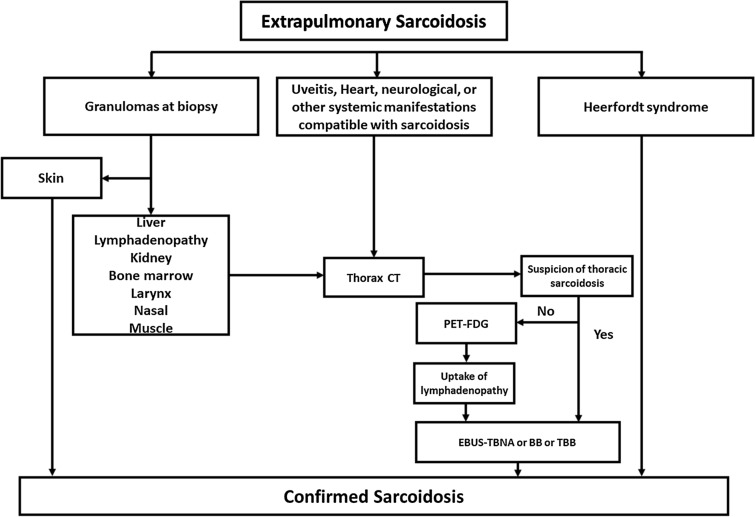

The diagnosis of sarcoidosis will rely on the following steps, as illustrated in Fig. 2. Heerfordt’s syndrome is considered sufficient for a definite diagnosis. Manifestations can be clinically highly suggestive of sarcoidosis, like granulomatous uveitis or typical granulomatous skin lesions or when typical non-caseating granulomatous lesions are observed on a biopsy of any organ (peripheral lymphadenopathy, liver, etc.). In all these cases, evidencing typical findings on thorax CT (typical bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy better evidenced with contrast medium or diffuse perilymphatic micronodular infiltration) leads to endobronchial fibroscopy to obtain granulomas either in lymphadenopathy through endobronchial ultrasound with real-time guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) or in bronchi and lung through bronchial or transbronchial lung biopsies. When thorax CT is normal or close to normal, 18FFDG-PET may allow to show a typical uptake of 18FFDG in hilar or mediastinal lymphadenopathy and then to observe granulomas thanks to EBUS-TBNA. In patients with suspicion for cardiac or central nervous system sarcoidosis on clinical and MR findings, thorax CT, 18FFDG-PET and bronchial endoscopy may also be crucial.

Fig. 2.

Diagnostic strategy for patients with extrapulmonary manifestations indicative of the disease. (This algorithm is based on the authors’ practice). PET positron emission tomography, CT computed tomography, EBUS-TBNA endobronchial ultrasound with real-time guided transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA), BB bronchial biopsy, TBB transbronchial biopsy

Biomarkers

Several biomarkers have been proposed for diagnosis and prognosis of sarcoidosis [27, 28]. They include serum measurement of angiotensin-converting enzyme (SACE), sIL2-R, serum amyloid A and chitotriosidase, as well as calcium metabolism, particularly calcium in urine, broncho-alveolar cell counts, and 18FFDG PET/CT. But none is ideal for diagnosis. SACE may suggest the diagnosis when > 2 N but this usually occurs in obvious presentations. Serum biomarkers, not expensive and not associated with radiation exposure as 18FFDG PET/CT, may help in treatment decision offering the opportunity to evaluate the biologic sarcoidosis activity in many patients. 18FFDG PET/CT may offer important diagnostic information when some extrapulmonary manifestations appear isolated (see above) and may also be very useful for the investigation of several extrapulmonary localizations [29, 30].

Diagnosis of Respective Visceral Localizations

In this chapter, we will focus more specifically on organs for which the diagnosis of sarcoidosis involvement is often overlooked or delayed or difficult to manage.

Upper Respiratory Tract

An important risk is to overlook sarcoidosis sinonasal localization which is observed only in 1.6–6% of cases, while more than 10% of the normal population have banal nasal symptoms [31, 32]. Persistent symptoms with nasal obstruction or stuffiness, epistaxis, crusting, or anosmia prompt a rhinoscopy to visualize very typical mucosal findings with granulomas at biopsy [20]. In up to 20% of cases, nasal findings precede by several months or years other manifestations of sarcoidosis, with the risk, when the diagnosis is overlooked, of persistent disabling symptoms, development of sinusal osseous lytic lesions, and recurrent infections, and also occurrence of extra severe localizations (eye, nervous system, lupus pernio, and pulmonary fibrosis) [20]. Laryngeal sarcoidosis, associated with sinonasal sarcoidosis in 80% of cases, and with lupus pernio in half of them, is typically supraglottic and involves the epiglottis, ary-epiglottic folds, and arytenoids. The presentation associates progressive breathlessness, hoarseness, and dysphagia. Forced vital capacity and forced expiratory volume in 1 s may remain normal, and only forced inspiratory volume in 1 s is significantly decreased [21]. The diagnosis needs to be confirmed by laryngoscopy with biopsy of the lesion. Both sinonasal and laryngeal sarcoidosis are most often integrated in multivisceral sarcoidosis of prolonged duration and can be severe, particularly laryngeal sarcoidosis with possible respiratory insufficiency, but also at the level of associated localizations. Alternative diagnoses including infections, particularly tuberculosis, leprosis (in endemic countries), histoplasmosis and syphilis, and non-infectious diseases like granulomatosis polyangiitis, eosinophilia granulomatosis with polyangiitis, or cocaine-induced lesions need to be ruled out by investigations according to epidemiological and clinical contexts (search for mycobacteria, antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies etc.…) [3].

Cardiac Sarcoidosis

Circumstances of Discovery, Presentation and Diagnosis

Cardiac sarcoidosis (CS) is found in 20–30% of sarcoidosis patients at autopsy or when multiple sensitive investigations are combined. Significant clinical manifestations occur in 5% of patients [33] and may be dangerous—complete atrioventricular block; sustained ventricular arrhythmia; congestive heart failure; sudden death, the latter concerning 14% of initial manifestations of CS [34]. They may be the initial manifestation of sarcoidosis (and can either be followed by typical extracardiac sarcoidosis or remain isolated), may be discovered at pulmonary sarcoidosis diagnosis work-up, or may be delayed, even several years after extracardiac sarcoidosis onset. In clinical practice, there are three different contexts for which cardiac sarcoidosis should be screened. First, patients with extracardiac sarcoidosis should be evaluated at the time of diagnosis work-up and every 6–12 months, looking for symptoms, and, for some physicians but not for all of them, ECG manifestations compatible with cardiac sarcoidosis to reduce the risk of sudden death in patients with silent cardiac sarcoidosis [3, 34]. Second, in patients with both extracardiac sarcoidosis and any of following manifestations: syncope, palpitations, heart failure symptoms (dyspnea at exercise or orthopnea); ankle edema—and ECG findings—atrioventricular block of any degree; right bundle branch block, left bundle branch block; or premature ventricular contractions, cardiac MR should be promptly considered [3] with specific diagnostic investigations if required as 18FFDG-PET. Eventually, patients without extracardiac sarcoidosis but with an advanced atrio-ventricular block and aged less than 60 or with idiopathic ventricular tachycardia should be proposed for both cardiac MR and 18FFDG-PET, the latter being most useful at the cardiac level but also for revealing occult intrathoracic lymphadenopathy [35, 36]. Other explorations, for example stress-echocardiography may be useful for alternative diagnoses. There are three available algorithms, including the new version of the Japanese Ministry of Health and Welfare (2016) [37], which help in assessing the diagnosis probability of cardiac sarcoidosis [17, 38]. However, when their conclusions disagree, this calls for a multidisciplinary discussion with a cardiologist and specialists in cardiac imaging for a final diagnosis (including ruling out cardiac sarcoidosis and considering an alternative diagnosis) and treatment strategy adapted to every patient [39]. Differential diagnoses include coronary diseases, giant cell myocarditis, arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia, and granulomatosis with polyangiitis [3].

Outcome and Prognosis

Cardiac sarcoidosis is the second cause of death due to sarcoidosis after advanced pulmonary disease or pulmonary hypertension in Western countries, and even the first cause of death in Japan. The major risk is sudden death, which may be due to a high degree of atrio-ventricular block or ventricular arrhythmia. Even though predictors of mortality have been proposed (class IV of New York Heart Association dyspnea class; heart failure at presentation; left ventricular ejection fraction lower than 35–40%; sustained ventricular tachycardia; increased left-ventricular end-diastolic diameter; larger area of late gadolinium enhancement, and older age) [40], it still remains difficult to know with certainty which patients are at risk of poor outcome. However, it is probable that the availability on the one hand of pacemakers, intracardiac defibrillator devices, and anti-sarcoidosis treatments, and on the other hand of accurate means for diagnosing and monitoring the disease can explain the reduction in mortality due to cardiac sarcoidosis [41].

Nervous System Sarcoidosis

Circumstances of Discovery and Diagnosis

Neurological manifestations occur in 3–5% of patients and even 10% of cases in some series [42]. They may involve any part of the neurological system: aseptic meningitis, cranial nerves, hypothalamus-pituitary gland, brain parenchyma (with various deficits, psychiatric manifestations, seizures, hydrocephalus), spinal cord, and peripheral nerves [43]. The facial nerve, uni- or bilaterally impaired, is usually considered the most frequent involvement before the optic and trigeminal nerves, while for some authors the optic nerve involvement is the most frequent before trigeminal and facial nerve involvements [44]. Neurosarcoidosis (NS) is usually present at onset of sarcoidosis. It is most often a revealing manifestation of sarcoidosis, and can be initially associated with extraneurological manifestations or isolated with either further extra-neurological manifestations or remaining as a persistent isolated neuro-sarcoidosis in 1–17% of cases [45]. In total, more than 80% of cases will be completed by extraneurological findings. The central nervous system is affected in 85%, while the peripheral nervous system in only 15% of the cases. The diagnosis of NS relies on three criteria [46], each one being determinant for the level of probability of diagnosis: (1) clinical presentation and other findings [cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), MR or electromyogram] suggestive of NS, (2) exclusion of any alternative diagnosis, and (3) either evidence of granulomas in the neurological system (diagnosis of NS is definite), or in an extra-neurological site (diagnosis of NS is probable), or no evidence of granulomas (diagnosis of NS is possible) [43]. This scheme is applicable at best when neurologic findings are initial. However, when they are delayed, the possibility of neurological comorbidity associated with sarcoidosis increases with time. Care is warranted in cases of possible NS with a significant risk of diagnostic error, particularly for infections (tuberculosis or progressive multifocal encephalopathy, even in untreated patients [47]) or multiple sclerosis or lymphoma. The diagnosis of spinal cord sarcoidosis is particularly difficult, since it is often limited to the neurological sphere and by the difficulty of obtaining granulomas [48]. It differs from multiple sclerosis by more extended lesions and gadolinium enhancement.

Presentation

Neurological clinical manifestations vary according to the localizations of the lesions in the neurological system. CSF analysis is most often useful despite low sensitivity, being abnormal in 50–70% of cases with either lymphocytic predominant pleocytosis (with increased CD4/CD8 ratio) [49, 50], increased proteinorrachia, and increased IgG index with sometimes oligoclonal bands or hypoglychorachia but always without any element indicative of infection or tumoral proliferation. Angiotensin-converting enzyme evaluation in CSF has no diagnostic value [51]. In the brain, MR shows suggestive images when located along Virchow–Robin’s spaces and enhanced under gadolinium or only compatible images [52]. In cases of hypothalamo-pituitary sarcoidosis, neuro-hormonal dosages confirm both post-pituitary (diabetes insipidus) and anterior-pituitary axis deficits [53]. In cases of peripheral nerve involvement, electromyograms and measurements of nerve velocity are useful. Rarely, a stroke with vascular or perivascular involvement occurs suddenly, most often as a revealing manifestation often with sequelae and a high mortality rate [54].

Eventually, small-fiber neuropathy and cognitive difficulty with impaired memory, slowed thinking, and diminished attention, despite this last manifestation, may also be observed in central NS [55], and may represent manifestations of parasarcoidosis syndrome.

Outcome

Cranial nerve impairment often follows a favorable course, while optic neuropathy may potentially be very severe with a risk of visual loss [56]. Central and peripheral NS may be severe if treatment is delayed or the disease resistant to treatments. The evolution is most often very long, with frequent flare-ups when treatment is tapered or stopped, and remissions when the treatment is resumed, following a relapsing–remitting course. Eventually, NS may progress and frequently lead to severe functional impairment. NS may be fatal in around 5–10% of patients with mortality associated with age, peripheral nervous system involvement, and worse basal Expanded Disability Status Scale score [42, 57]. Spinal cord sarcoidosis is particularly severe, often with indirect complications like deep vein thrombosis [48].

Renal Sarcoidosis

Circumstances of Discovery and Diagnosis

Sarcoidosis may involve the kidney through abnormal calcium metabolism, nephrolithiasis, granulomatous renal involvement, and nephrocalcinosis. Here, we consider only granulomatous renal involvement (RS) which can be observed at the histopathological level in up to 13% of sarcoidosis patients but is clinically significant in only 0.7–4.3% of them [19]. It is revealed in 80% of patients at the onset of sarcoidosis. Renal failure can show extrarenal localizations of the disease in two-thirds of cases, while abnormal renal function is discovered in the work-up of other manifestations of sarcoidosis in the other third. RS flare-up may be delayed, often several years after sarcoidosis onset, in 20% of cases, underscoring the importance of scheduled surveillance of renal function until sarcoidosis recovery [19]. In our experience, mean age at onset is 47 years and the male/female ratio is high (1.76), as in Berliner’s series [19, 58], which is different from extrarenal sarcoidosis which is usually more frequent in females. The onset of RS is remarkable for the high frequency of constitutional symptoms, particularly fever in 17% and weight loss in 42%, while hypertension is seen in only 23% of cases, and ankle edema is absent. The disease is often plurivisceral with mediastino-pulmonary involvement almost constant and other extrarenal localizations frequent. RS is more frequent in abdominal phenotype than in other phenotypes [5]. Renal function is severely impaired with sharply increased creatinine serum level, leading to hypercalcemia being particularly frequent (34%), notably during summer (50%), probably due to an insufficient renal excretion of calcium in the context of abnormal vitamin D and calcium metabolisms [59, 60].

Diagnosis relies on percutaneous renal biopsy, evidencing typical granulomas in 80%, while interstitial nephritis without granulomas is seen in 20% of cases in association with typical extrarenal sarcoidosis. Differential diagnoses include infections (particularly tuberculosis), drugs (allopurinol, anti-epileptic, beta-lactamins, etc.) or granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Nephrocalcinosis is more frequent at histopathology than on imaging. Rarely, renal sarcoidosis has a pseudo-tumoral presentation on imaging, necessitating a biopsy for differentiating a renal carcinoma association.

Outcome

RS improves rapidly under treatment but a renal insufficiency persists in most cases due to the particularly frequent presence of renal fibrosis.

Liver and Spleen Sarcoidosis

Circumstances of Discovery and Diagnosis

Liver sarcoidosis is more frequent in African-Americans than in Europeans, particularly in childhood, where it is seen in nearly half of cases at diagnosis [4, 61]. Despite the fact that granulomas can be found in the liver in up to 50–70% of sarcoidosis patients, clinically significant hepatic sarcoidosis is observed in only 11.5–30% of them [24]. There are three main circumstances of discovery of liver sarcoidosis with different diagnostic questions. First, hepatic biologic test abnormalities or more rarely some clinical manifestations are discovered at diagnosis work-up or at follow-up of patients with extrahepatic sarcoidosis, and we must question whether there is liver sarcoidosis or an alternative diagnosis. Evidencing granulomas at liver biopsy and ruling out any alternative cause (particularly tuberculosis and primary biliary cirrhosis) are crucial to confirming the diagnosis in a patient with extrahepatic sarcoidosis. Second, the discovery of a granulomatous hepatitis leads to finding extrahepatic manifestations typical of sarcoidosis (e.g., typical bilateral thoracic lymphadenopathies at imaging). And third, rarely (no more than 5% of liver sarcoidosis cases), granulomatous hepatitis without any finding elsewhere at diagnosis time may evolve to further typical sarcoidosis with extra localizations (regular attention paid to any new clinical finding or on periodic thoracic imaging is crucial) or remain isolated, raising difficult questions (is it a primary biliary cirrhosis or a granulomatous hepatitis of alternative cause or a sarcoidosis limited to the liver?).

Presentation

Clinically, liver sarcoidosis is most often latent, while weight loss, fever, abdominal pain, or, exceptionally, pruritis or jaundice or portal hypertension complications may also reveal the disease. In 5% of cases, a hepatomegaly or splenomegaly is noticed. Interestingly, liver sarcoidosis is twice as frequent in subacute than acute-onset sarcoidosis, and it is mostly found in case of an “abdominal phenotype” [5].

Most frequent findings are abnormal hepatic biological tests with increased level of ALAT, ASAT, gGT, and alkaline phosphatase, the latter being more typical when > 3 N.

Abdominal imaging may show frequent abnormalities with CT and MRI being more sensitive than ultrasound. Enlargement of liver, spleen, and abdominal lymphadenopathies are the most frequent findings. Focal nodules of 0.5–1.5 cm in diameter are multiple and hypodense with CT and MR. Nodules are hypo-intense on T1-weighted and T2-weighted images and hypo-enhanced relative to the background of the liver and spleen, and this helps to differentiate liver sarcoidosis from metastases and lymphomas [30].

Histopathology is a corner-stone for diagnosing liver sarcoidosis. The indication is particularly recommended when two abnormal liver functional tests are > 3 N [62]. Viral serology and special stains need to be used to rule out alternative diagnoses.

Outcome

Studies on liver and spleen sarcoidosis are limited. In most cases, the disease remains benign. However, a severe evolution may occur at any time, sometimes after a long period. Complications include portal hypertension (3–20%), cirrhosis (3–6%) [63], and, in more severe cases, hepatic insufficiency. Spleen enlargement can lead to hypersplenism, and when very voluminous to risk of rupture. Splenomegaly is often associated with a chronic outcome [6].

Parotid Gland Sarcoidosis

Circumstances of Discovery, Presentation and Diagnosis

Parotid glands are clinically involved in 2–5% of cases. They present as an acute bilateral painless parotid swelling associated or not with submaxillary and sublingual swelling with mouth dryness. Sometimes, they are part of Heerfordt’s syndrome when associated with uveitis, fever, and facial palsy. They are usually initial in the history of sarcoidosis, and the diagnosis relies on associated obvious manifestations.

Outcome

In most cases, parotid swelling resolves in 8–12 weeks even without treatment, independently of the course of other localizations.

Skeleton Sarcoidosis

Circumstances of Discovery and Diagnosis

Clinically overt osseous sarcoidosis is rare, observed in only 0.5% in the ACCESS study [4]. However, occult sarcoidosis involvement revealed in patients investigated by 18FFDG-PET is more common. Overt osseous sarcoidosis is most often expressed at the clinical level by pain and deformed fingers, and on radiography by typical cystic lesions or moth-eaten patterns in the phalange heads of hands and toes, sometimes with surrounding soft tissue swelling [64]. These manifestations occur after several years of evolution in sarcoidosis, particularly in association with lupus pernio or sinonasal sarcoidosis. Such a presentation is very typical, with no need for further histopathological investigation in patients with confirmed sarcoidosis. Occult osseous sarcoidosis is often revealed fortuitously in patients investigated by 18FFDG-PET [65]. These involvements concern mainly the spine or the pelvis, but may also affect the skull and long bones [66]. Sometimes, they can be painful. Often, these lesions are not visible on radiography or CT, with MR being the best means to investigate them. Even when sarcoidosis diagnosis is confirmed, it may be difficult to differentiate specific osseous sarcoidosis from metastases, with the need, after discussion with rheumatologists, of imaging-directed osseous biopsy.

Muscular Sarcoidosis

Circumstances of Discovery and Diagnosis

Despite being frequent at autopsy, muscular sarcoidosis is a very rare clinical manifestation of sarcoidosis [22]. Four distinct patterns of muscular patterns, all symptomatic, have been described: nodular pattern, smoldering phenotype, myopathic type, and combined myopathic and neurogenic pattern [22]. It more frequently affects females than males, and some presentations, nodular and myopathic patterns, are mainly seen in African-Americans. In most cases, muscular localizations are part of a multivisceral sarcoidosis with several other localizations, and associated thoracic manifestations are almost always present. However, the circumstances of discovery vary according to muscular pattern, with the nodular muscular pattern often occurring at onset of sarcoidosis in young patients, often of African-American descent, the smoldering pattern often occurring during the evolution of sarcoidosis, and the myopathic pattern often being delayed several years after sarcoidosis onset. The diagnosis relies on three points: muscle symptoms or signs (pain, nodules or weakness) reinforced by laboratory, imaging and electrophysiologic data, evidence of muscular granulomas, and confirmed systemic sarcoidosis elsewhere. Diagnostic difficulty may arise when the myopathy occurs in patients under corticosteroids, as they also are a cause of myopathy [67]. Diffuse muscular pain may be due to parasarcoidosis syndrome, to be differentiated from true muscular sarcoidosis.

Presentation

The nodular pattern is characterized by muscular palpable nodules, frequent myalgias, but no deficit, with muscular MR being often abnormal contrary to electromyography being often normal. The smoldering pattern manifests by isolated myalgia without nodules, deficit, or atrophy, and is often associated with skeletal and ophthalmic localization, with electromyograms often abnormal contrary to muscular MR. The myopathic pattern gives motor deficit, usually proximal, with both muscular MR and electromyograms abnormal in patients with thoracic sarcoidosis. The combined myopathic and neurologic pattern is rare, with various presentations and characterizations on muscular biopsy. Among all patterns, half of patients display increased creatine phosphokinase levels.

Outcome

The nodular pattern often follows a relapsing–remitting course, the smoldering pattern often has a monophasic course, the myopathic pattern follows a progressive course in 18% of cases despite treatment, while the combined myopathic and neurogenic pattern leads to frequent sequelae.

Ocular Sarcoidosis

Circumstances of Discovery and Diagnosis

The eye is involved in about 11% of sarcoidosis cases, and is usually an initial manifestation revealing sarcoidosis, raising the question of how rely on ocular manifestations to yet undiagnosed sarcoidosis [68]. Epidemiological factors have an important impact on eye localization incidence and presentation. Eye involvement is very frequent in Japan (up to 64–89% of patients) and more frequent in African-Americans than in Caucasians in the USA. The presentation depends upon the age of declaration of the disease, with mainly posterior uveitis presentation in elderly Caucasians, while various presentations are seen in all other populations independently of sex and ethnicity [69, 70]. Often, red eye or visual impairment or pain leads to consultation with an ophthalmologist, while, in cases where extra-ophthalmological sarcoidosis reveals the disease, a systematic examination by an ophthalmologist discloses a latent ocular involvement. In most cases, when uveitis is the initial manifestation, a work-up is necessary to investigate sarcoidosis as the cause, by performing a thorax CT scan with contrast injection, dosage of SACE, bronchoalveolar lavage in search of lymphocytic alveolitis with lymphocyte CD4/CD8 ratio above 3.5, and, ultimately, 18FFDG-PET, which may show an extra-ocular target for biopsy [71]. When uveitis remains isolated, the diagnosis may be comforted by the delayed occurrence of new localizations, encouraging scheduled repeat simple explorations during follow-up. However, such an outcome is very rare when initial thorax CT or 18FFDG-PET are normal [68]. An International Workshop on Ocular Sarcoidosis revised in 2019 is helpful for assessing the diagnosis level of probability in difficult cases [71].

Presentation

Any part of the eye and adnexal tissues may be involved with uveitis, bilateral being the most frequent manifestations, with anterior uveitis being more frequent than posterior, intermediate, and panuveitis. Other manifestations include optic neuropathy which mostly involves sub-Saharan African or Caribbean females, lacrimal gland enlargement, sicca syndrome, conjunctivitis, or, rarely, orbital involvement with exophtalmia.

Outcome

The prognosis is favorable, with a good visual outcome for most patients usually with a very good treatment response. However, in 2.4–10% of these patients, a visual impairment up to blindness in one eye or both often with cystoid macular edema, may represent a severe complication of sarcoidosis.

Skin Sarcoidosis

Skin lesions, occurring in up to one-third of patients, are varied and most often initial [72]. They easily demonstrate non-caseating granulomas. The clinical presentation of skin lesions is very suggestive in most cases, but may appear nonspecific. Alternative granulomatous skin diseases need to be ruled out, particularly in countries with persistent leprosy endemic disease. Skin lesions represent the most frequent presentation of non-pulmonary sarcoidosis, but, in most cases, it is associated with or precedes a typical multivisceral presentation. However, in 30% of cases, sarcoidosis may remain a purely dermatological disease [73]. Skin sarcoidosis has multiple presentations with typically erythematous macules, papules, and plaques without symptoms. Lupus pernio is the most severe skin manifestation, occurring most frequently in black females, usually after several years of evolution. Lupus pernio has been shown to be indicative of a severe evolution with a frequent association of sinonasal, osseous (most commonly of the fingers and toes), severe arthropathy, and lung localizations, the latter often with fibrosis [8, 12].

Peripheral Lymphadenopathies

Peripheral lymphadenopathies are frequent, observed in around 15% of cases, usually initial in the course of sarcoidosis, even though they may arise later but more rarely [4]. They are mostly seen in black patients aged less than 40 years. The most common site is the neck and the supraclavicular area, and affected lymph nodes are usually firm, mobile, and not tender. Their detection allows the obtaining of easily non-caseating granulomas through echo-guided biopsies [74]. A search for alternative diagnosis, particularly tuberculosis or non-tuberculosis mycobacterial infection, is indispensable. Most often, lymphadenopathies are associated with or followed by extra lymph node manifestations confirming sarcoidosis diagnosis. When they remain isolated, the diagnosis is not certain, and alternative hypotheses like tuberculosis remain possible even in the absence of caseating necrosis. Peripheral lymphadenopathies are rarely delayed in the course of sarcoidosis and, in this context, the diagnosis has to be challenged, particularly in the presence of “B symptoms”, with comorbidities like lymphoma, cancer, or infection, like tuberculosis, nontuberculous mycobacteria, or HIV, warranting further investigations, often including a histopathological confirmation.

Other Extrapulmonary Localizations

Various other organs may be involved, usually in rare cases, including the genito-urinary system (notably at the epididymis or breast levels) and the digestive tract, particularly at the stomach level [75].

Abnormal Calcium and Vitamin D Metabolism

Hypercalciuria is observed in more than 30% of cases, more often than hypercalcemia which is observed in 5–25% of cases, sometimes associated with nephrolithiasis or nephrocalcinosis [4]. Hypercalcemia is more frequent in white than black patients and in males than females. Abnormal calcium metabolism in sarcoidosis is the consequence of both an increased digestive calcium absorption and osseous resorption, mainly due to abnormal vitamin D metabolism with an increased calcitriol synthesis at the level of granulomatous lesions despite decreased 25 0H-vitamin D levels in active sarcoidosis [59, 60, 76].

Follow-up Monitoring of Extrapulmonary Organ Localizations

Clinical examination is always crucial for monitoring the evolution of recognized localizations but also for revealing any new localizations, prompting extra investigations when justified. Scheduled follow-up makes it possible to assess the response and tolerance to treatments. Most often, flare-ups are only observed in the organs initially involved, but sometimes in association with new localizations, and, more rarely but very misleading, in new sites despite no progression in initial ones.

In patients under a new treatment, a close examination, usually at 1 month, allows the assessment of any response and of the tolerance of rapidly effective treatment like corticosteroids, as shown at the pulmonary and renal levels [18, 19].

For skin, eye, and peripheral lymph-nodes, clinical investigation is sufficient. For kidney and liver, the basis of investigation is on renal and hepatic biologic tests, sometimes with imaging. For the heart, ECG may be completed by MR and, if indicated, by echocardiography, a 24-h holter ECG, and 18FFDG-PET, while for the central nervous system clinical examination, MR imaging, and sometimes CSF analysis, are indicated.

Scores have been proposed for assessing the evolution of extrapulmonary sarcoidosis either at every organ level, particularly the skin [77, 78], or globally [77, 78], but they still need validating [79].

We will next underscore manifestations of the severity of sarcoidosis. As sarcoidosis severity at organ levels has been developed in the above section, we will focus on poor general outcome prediction.

In the past, Neville showed that lupus pernio, sinonasal involvement, dactylitis, nephrocalcinosis, and splenic involvement were associated with long-duration evolution, advanced pulmonary disease, and increased mortality [8]. More recently, Mana confirmed a link between splenomegaly and a long duration [6], and Aubart evidenced that sinonasal involvement was most often associated with a multivisceral disease, and often with the presence of eye, nervous system, and lung localizations [20]. These manifestations are often associated with lung fibrosis.

Care of Patients with Extrapulmonary Sarcoidosis

As for the lung, extrapulmonary sarcoidosis therapy should rely on three goals: to improve organ dysfunction risks, to reduce mortality, and to improve quality of life [80]. However, there are virtually no double-blind controlled randomized trials available, and many questions, such as the impact on survival, quality of life, or organ dysfunction have not been rigorously assessed. Also, the effects on sarcoidosis of the available drugs have not been compared, such as for their doses or duration of treatment. In this context, therapeutic propositions are only based on experience and retrospective studies and series, and many questions have no indisputable answer. They are often derived from data related to pulmonary sarcoidosis and what is known about the natural evolution of extrapulmonary sarcoidosis.

Before considering the various treatments, it is important to underscore important points on which their rationale is based:

A comprehensive care for extrapulmonary sarcoidosis is based not only on disease-modifying drugs aimed at controlling the granulomatous process (also called anti-sarcoidosis or anti-inflammatory drugs) but also on organ-directed treatments (e.g., implantable cardiac defibrillator) and also supportive treatments aimed at relieving symptoms and improving quality of life [10]. Applying the ABCDE method is recommended [10].

Care of extrapulmonary sarcoidosis needs to be integrated with other aspects of the disease, like pulmonary manifestations and parasarcoidosis syndrome, which may also need to be especially considered [81].

Care should be personalized, taking into consideration treatment tolerance and risks, medical history and medical examination, and, also, an important point, patient expectations [11].

Treatment adherence may be low in sarcoidosis, particularly in patients with a decreased quality of life [81, 82]. Therefore, a poor adherence should be considered as a main cause of treatment failure [83].

Response to treatment has to be adequately assessed using correct criteria at correct times. Means for assessing the treatment response may be different from organ to organ (see above). The response may be only partial and the question would be to determine whether or not the response is as expected, taking into account the presence of irreversible lesions. That point may necessitate multidisciplinary discussions. Recently, minimal clinically important differences have been determined for quality of life scores in sarcoidosis. These might become in the near future one important means for assessing the impact of treatments [84]. Difficult cases may benefit from reference to centers of excellence in sarcoidosis listed by the WASOG.

We will then consider, respectively, treatment abstention and topic treatments, anti-sarcoidosis treatments, and organ dysfunction treatments and then indications, doses, and schedules.

Therapeutic Abstention or Topic Treatments

More than 50% of patients require no treatment after diagnosis work-up, and many of them will never require any treatment during follow-up until a spontaneous recovery is obtained, while some will require a delayed treatment when a disease progression meets criteria for initiating a treatment.

Absence of treatment relies on the absence of the 'at risk' involvement of any organ, particularly eye, heart, nervous system, kidney, hypercalcemia, or lung. Topic treatments at the skin and eye levels may be proposed in cases of limited involvement.

Anti-sarcoidosis Treatments

Anti-sarcoidosis treatments are based on anti-inflammatory drugs directed against the granulomatous reaction. The improvement is often correlated with the initial granulomatous mass, and 18FFDG-PET may be useful for predicting expected responses [29]. The assessment of the response is at 1–3 months for corticosteroids and at 3–6 months for immunosuppressive treatments, allowing tapering doses in favorable cases, while the absence of a response can lead to an increase of the dose or a move to a higher line level drug after ruling out a diagnosis error, a poor adherence, or an incorrect indication.

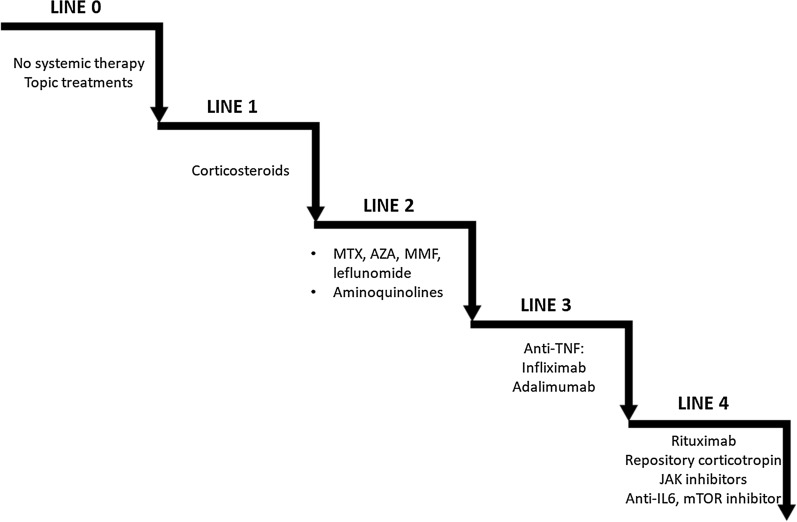

It is important to note that not all treatments are approved in the respective countries. Before considering off-labeled prescriptions, particular caution is recommended, particularly for balancing the expected benefit/adverse event ratio, informing patients, and evaluation of the cost. Solicitation of centers of excellence for sarcoidosis advice is very desirable, and all the more when no trials are available. Treatments are classified in four lines, as shown on Fig. 3, inspired from Baughman [85].

Fig. 3.

Anti-sarcoidosis lines of treatment (inspired from RP Baughman [85]). MTX methotrexate, AZA azathioprine, MMF mycophenolate mofetil

First-Line Therapy

Corticosteroid therapy is considered the first-line therapy of sarcoidosis. Adverse events should be recognized as early as possible, as recent works have shown their frequency and potential severity (diabetes, hypertension, osteoporosis, glaucoma, cataract, infections, dyslipidemia, etc.) [86]. Importantly, corticosteroids have a dose-dependent negative impact on quality of life [87, 88]. The trend is to use second-line treatments as soon as possible as corticosteroid-sparing agents to limit adverse events of corticosteroids, as recommended for rheumatoid arthritis.

Second-Line Therapy

Second-line treatments are recommended in three circumstances: (1) failure of corticosteroid treatment, (2) contra-indications to corticosteroids or significant adverse events, and (3) prolonged need for corticosteroid doses > 7 mg/day, or significant adverse effects with doses < 7 mg/day, or according to patient wishes. For some physicians, associating a second-line treatment with corticosteroids from the start might help to more rapidly decrease corticosteroid doses when a long-standing course of sarcoidosis can be expected. Contra-indications need to be respected, in particular a pregnancy or the absence of contraception for both women and men, and impaired renal and hepatic functions. Azathioprine, often as effective as methotrexate, seems to be associated with an increased risk of infections [89, 90]. Leflunomide and mycophenolate mofetil, less studied in sarcoidosis, may be used. Cyclophosphamide, which in the twentieth century was considered for severe cardiac and neurologic localizations resistant to corticosteroids, is now reserved for very rare cases thanks to the availability of anti-TNF drugs.

Third-Line Therapy

Infliximab and biosimilars are proposed in patients having experienced corticosteroid and second-line treatment failure or bad tolerance. Low doses (7.5–10 mg) of methotrexate every week are associated with preventing auto-antibody production. Adalimumab may alternatively be given, while other anti-TNF drugs have not proved their efficacy. In lupus pernio, a response may be delayed for 12 months [91].

Fourth-Line Therapy

In very difficult cases, some drugs may be proposed for compassionate purposes. Their use is supported by case report experience, retrospective studies, and also pathophysiological rationale [92]. Without available trials, and for some of them a benefit is shown only for lung impairment, their use remains exceptional. Some of them are targeted to the recently highlighted mTOR, IL6, or JAK/STAT pathways. They might be recommended in severe active sarcoidosis resistant to the first three lines of treatment: rituximab [93]; repository corticotropin [94]; anti-IL6 like tocilizumab [95]; anti-JAK like tofacitinib or ruxolitinib [96, 97]; and mTOR inhibitors like sirolimus [98].

Organ Dysfunction Treatments

Improvements of the outcome of sarcoidosis relies on some non-pharmacological therapies, like implantable cardiac devices or pacemakers, CSF diversion to manage hydrocephalus, and on transplantation for the heart [41, 99, 100], kidney [101, 102], and liver [103]. Hormonal substitution may also be required for a sarcoidosis-related deficit, for example, at the hypothalamo-pituitary level. Anti-epileptic drugs or psychiatric medications may be justified.

Indications, Doses, Schedules

Treatment concerning specific extrapulmonary sarcoidosis localization can only be proposed on an experience basis for most situations, except for heart, nervous system, or skin, for which evidence remains poor [104]. It is most often indicated for heart, central nervous system, renal, muscular, or laryngeal localizations, and hypercalcemia higher than 3.0 mmol/L. Prednisone/prednisolone is usually initiated at 20–40 mg/day (1/3–1/2 mg/kg/day), but, uncommonly, higher doses are given (60 mg/day or 1 mg/kg/day), when the disease is considered particularly severe, as for neurological, cardiac, renal, or some ophthalmological (posterior uveitis with macular edema or optic neuritis) or laryngeal manifestations. However, the superiority of high doses of corticosteroids does not rely on solid bases, and has been challenged at the cardiac and renal levels. Initial prednisone/prednisolone doses are most often recommended for 1 month, and, after evaluation, they are gradually decreased until 10 mg/day between 3 and 9 months, according to evolution. Methotrexate is often an effective second-line therapy, while anti-TNF therapy might be proposed as a third-line therapy, taking into account that anti-TNF may rarely be responsible for cardiac dysfunction [105].

Methotrexate has been recognized as beneficial in lupus pernio, ophthalmologic, neurologic, and musculo-skeletal sarcoidosis. Methotrexate is administered at 10–15 mg once a week for most situations, and 25 mg once a week in central nervous system sarcoidosis. Aminoquinolines like hydroxychloroquine given 400 mg/day are particularly interesting for skin lesions, arthritis, and hypercalcemia.

Infliximab and biosimilars are given at 3–5 mg/kg at days 0 and 15, and then every 4–6 weeks. Anti-TNF therapy has been shown to be beneficial in lupus pernio, central nervous system, and eye localizations. Anti-TNF therapy might be proposed to be included in treating cardiac sarcoidosis taking into account that anti-TNF may rarely be responsible for cardiac dysfunction, justifying particular caution in patients with cardiac failure [105].

For heart involvement, an anti-sarcoidosis treatment is proposed in cases of Mobitz II grade II or grade III atrio-ventricular block, with an expected response in half of cases. Sustained or not sustained ventricular tachycardia and left ventricular dysfunction are indications to treat when myocardial inflammation is evidenced on 18FFDG-PET. This point is reinforced by the demonstration of an improvement under treatment of an impaired left ventricular function when associated with a left ventricular 18F FDG uptake [106]. It is recommended to assess the response to therapy on sequential echocardiography and a 18FFDG-PET carried out 3–6 months later. In asymptomatic cardiac sarcoidosis, patients most often have an uncomplicated course and there is no evidence for a treatment benefit [107], but a thorough cardiac monitoring is required. Recommendations for an intracardiac device to reduce the risk of sudden death have been published [38]. It is indicated in patients with sustained ventricular tachycardia, after a cardiac arrest, and in patients with a left ventricular ejection fraction lower than 35% despite immunosuppressants [38]. A pacemaker is indicated in high-degree A-V block. In cases of advanced cardiac disease despite a correct anti-sarcoidosis treatment, a cardiac transplantation may be proposed in the absence of contra-indications.

In central nervous system sarcoidosis, corticosteroids are indicated. There is no trial-based evidence for the use of a second- or a third-line treatment. However, they are often recommended as corticosteroid-sparing agents to alleviate adverse events of long-term use of corticosteroids. Methotrexate and infliximab may be effective and associated with reduced relapse occurrence [57, 108, 109]. Serial MR are particularly useful for treatment monitoring [52].

The treatment of renal sarcoidosis relies mainly on corticosteroids. The use of methotrexate is contra-indicated in patients with renal insufficiency. Renal dialysis may be required as well as a renal transplantation [101, 102].

Laryngeal and sinonasal sarcoidosis are often difficult to treat. Aside from medical treatment which is often poorly effective, surgical surgery, particularly laser-surgery, can be very useful [21].

Ophtalmological sarcoidosis is often very sensitive to corticosteroid therapy. Methotrexate is also very effective. Infliximab and adalimumab may be very effective in cases of resistance or intolerance to corticosteroids and methotrexate [110].

Lupus pernio is one of the most difficult skin lesions to treat, as it is often resistant to corticosteroids and hydroxychloroquine. Methotrexate and, in case of resistance, infliximab or adalimumab, may be very effective [91]. In contrast, thalidomide has been proved ineffective in a controlled trial [111].

Conclusions

It is important to point out that most of the statements on sarcoidosis treatment are not evidence-based but based only on the author’s and experts' experience. This important point is underscored in the ERS practical treatment guidelines on sarcoidosis [104]. This ambitious review is to be a kind of vade mecum for diagnosing and treating extrapulmonary manifestations with the best accuracy and without avoidable delay. Important points, apart from preventing or alleviating dangerous sarcoidosis, concern treatment tolerance, quality of life, treatment adherence, and, mostly important, patient expectations. There are still important needs for new molecules against refractory manifestations, more clear-cut criteria for whether or not to initiate a treatment, assessing response to treatment, and for determining optimal doses and durations.

Acknowledgements

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

Conceptualization: Dominique Valeyre, Jean-François Bernaudin; Writing—original draft preparation: Dominique Valeyre; literature search: Dominique Valeyre, Jean-François Bernaudin, Florence Jeny, Cécile Rotenberg; Figures and tables design: Cécile Rotenberg, Florence Jeny, Dominique Valeyre; all authors critically revised the work; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosures

Dominique Valeyre has no direct COI disclosure but declares having been a member of scientific advisory boards on idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis supported by Boehringer Ingelheim and Roche respectively. Yurdagül Uzunhan reports personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Roche, non-financial support from Oxyvie, outside the submitted work. Florence Jeny, Cécile Rotenberg, Diane Bouvry, Pascal Sève, Hilario Nunes and Jean-François Bernaudin have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Grunewald J, Grutters JC, Arkema EV, Saketkoo LA, Moller DR, Müller-Quernheim J. Sarcoidosis. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2019;5(1):45. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0096-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valeyre D, Prasse A, Nunes H, Uzunhan Y, Brillet P-Y, Müller-Quernheim J. Sarcoidosis. Lancet Lond Engl. 2014;383(9923):1155–1167. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60680-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crouser ED, Maier LA, Wilson KC, Bonham CA, Morgenthau AS, Patterson KC, et al. Diagnosis and detection of sarcoidosis. An Official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(8):e26–51. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202002-0251ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA, Rossman MD, Yeager H, Bresnitz EA, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(10 Pt 1):1885–1889. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.10.2104046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schupp JC, Freitag-Wolf S, Bargagli E, Mihailović-Vučinić V, Rottoli P, Grubanovic A, et al. Phenotypes of organ involvement in sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 2018;51(1). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Mañá J, Rubio-Rivas M, Villalba N, Marcoval J, Iriarte A, Molina-Molina M, et al. Multidisciplinary approach and long-term follow-up in a series of 640 consecutive patients with sarcoidosis: Cohort study of a 40-year clinical experience at a tertiary referral center in Barcelona, Spain. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96(29):e7595. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000007595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spagnolo P, Rossi G, Trisolini R, Sverzellati N, Baughman RP, Wells AU. Pulmonary sarcoidosis. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(5):389–402. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30064-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neville E, Walker AN, James DG. Prognostic factors predicting the outcome of sarcoidosis: an analysis of 818 patients. Q J Med. 1983;52(208):525–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Judson MA. Extrapulmonary sarcoidosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;28(1):83–101. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-970335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moor CC, Kahlmann V, Culver DA, Wijsenbeek MS. Comprehensive Care for Patients with Sarcoidosis. J Clin Med. 1 févr 2020;9(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Baughman RP, Barriuso R, Beyer K, Boyd J, Hochreiter J, Knoet C, et al. Sarcoidosis: patient treatment priorities. ERJ Open Res. 2018;4(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Lhote R, Annesi-Maesano I, Nunes H, Launay D, Borie R, Sacré K, et al. Clinical phenotypes of extrapulmonary sarcoidosis: an analysis of a French, multiethnic, multicenter cohort. Eur Respir J. 2020;57(4):2001160. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01160-2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.James WE, Koutroumpakis E, Saha B, Nathani A, Saavedra L, Yucel RM, et al. Clinical Features of Extrapulmonary Sarcoidosis Without Lung Involvement. Chest. 2018;154(2):349–356. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inoue Y, Inui N, Hashimoto D, Enomoto N, Fujisawa T, Nakamura Y, et al. Cumulative incidence and predictors of progression in corticosteroid-naïve patients with sarcoidosis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(11):e0143371. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeny F, Bernaudin J-F, Cohen Aubart F, Brillet P-Y, Bouvry D, Nunes H, et al. Diagnosis issues in sarcoidosis. Respir Med Res. 2020;77:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.resmer.2019.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kubo T, Ohno Y, Kauczor HU, Hatabu H. Radiation dose reduction in chest CT–review of available options. Eur J Radiol. 2014;83(10):1953–1961. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2014.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Judson MA, Costabel U, Drent M, Wells A, Maier L, Koth L, et al. The WASOG sarcoidosis organ assessment instrument: an update of a previous clinical tool. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2014;31(1):19–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Broos CE, Wapenaar M, Looman CWN, In 't Veen JCCM, van den Toorn LM, van den Toorn MJ, Overbeek MJ, Grootenboers MJJH, Heller R, Mostard RL, Poell LHC, Hoogsteden HC, Kool M, Wijsenbeek MS, van den Blink B. Daily home spirometry to detect early steroid treatment effects in newly treated pulmonary sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 2018;51(1):1702089. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02089-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahévas M, Lescure FX, Boffa J-J, Delastour V, Belenfant X, Chapelon C, et al. Renal sarcoidosis: clinical, laboratory, and histologic presentation and outcome in 47 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2009;88(2):98–106. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e31819de50f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aubart FC, Ouayoun M, Brauner M, Attali P, Kambouchner M, Valeyre D, et al. Sinonasal involvement in sarcoidosis: a case-control study of 20 patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006;85(6):365–371. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000236955.79966.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duchemann B, Lavolé A, Naccache J-M, Nunes H, Benzakin S, Lefevre M, et al. Laryngeal sarcoidosis: a case-control study. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2014;31(3):227–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen Aubart F, Abbara S, Maisonobe T, Cottin V, Papo T, Haroche J, et al. Symptomatic muscular sarcoidosis: lessons from a nationwide multicenter study. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2018;5(3):e452. doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yanardağ H, Pamuk GE, Karayel T, Demirci S. Bone marrow involvement in sarcoidosis: an analysis of 50 bone marrow samples. Haematologia (Budap) 2002;32(4):419–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rossi G, Ziol M, Roulot D, Valeyre D, Mahévas M. Hepatic sarcoidosis: current concepts and treatments. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;41(5):652–658. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1713799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kouranos V, Tzelepis GE, Rapti A, Mavrogeni S, Aggeli K, Douskou M, et al. Complementary role of CMR to conventional screening in the diagnosis and prognosis of cardiac sarcoidosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10(12):1437–1447. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2016.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Soussan M, Brillet P-Y, Nunes H, Pop G, Ouvrier M-J, Naggara N, et al. Clinical value of a high-fat and low-carbohydrate diet before FDG-PET/CT for evaluation of patients with suspected cardiac sarcoidosis. J Nucl Cardiol. 2013;20(1):120–127. doi: 10.1007/s12350-012-9653-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cameli P, Caffarelli C, Refini RM, Bergantini L, d’Alessandro M, Armati M, et al. Hypercalciuria in sarcoidosis: a specific biomarker with clinical utility. Front Med. 2020;7:568020. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.568020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kraaijvanger R, Janssen Bonás M, Vorselaars ADM, Veltkamp M. Biomarkers in the diagnosis and prognosis of sarcoidosis: current use and future prospects. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1443. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keijsers RGM, Grutters JC. In which patients with sarcoidosis is FDG PET/CT indicated? J Clin Med. 2020;9(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Soussan M, Augier A, Brillet P-Y, Weinmann P, Valeyre D. Functional imaging in extrapulmonary sarcoidosis: FDG-PET/CT and MR features. Clin Nucl Med. 2014;39(2):e146–159. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e318279f264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baughman RP, Lower EE, Tami T. Upper airway. 4: sarcoidosis of the upper respiratory tract (SURT) Thorax. 2010;65(2):181–186. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.112896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neville E, Mills RG, Jash DK, Mackinnon DM, Carstairs LS, James DG. Sarcoidosis of the upper respiratory tract and its association with lupus pernio. Thorax. 1976;31(6):660–664. doi: 10.1136/thx.31.6.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yafasova A, Fosbøl EL, Schou M, Gustafsson F, Rossing K, Bundgaard H, et al. Long-term adverse cardiac outcomes in patients with sarcoidosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(7):767–777. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.06.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ekström K, Lehtonen J, Nordenswan H-K, Mäyränpää MI, Räisänen-Sokolowski A, Kandolin R, et al. Sudden death in cardiac sarcoidosis: an analysis of nationwide clinical and cause-of-death registries. Eur Heart J. 2019;40(37):3121–3128. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chazal T, Varnous S, Guihaire J, Goeminne C, Launay D, Boignard A, et al. Sarcoidosis diagnosed on granulomas in the explanted heart after transplantation: results of a French nationwide study. Int J Cardiol. 2020;307:94–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.12.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenthal DG, Parwani P, Murray TO, Petek BJ, Benn BS, De Marco T, et al. Long-term corticosteroid-sparing immunosuppression for cardiac sarcoidosis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(18):952. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.010952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Terasaki F, Azuma A, Anzai T, Ishizaka N, Ishida Y, Isobe M, et al. JCS 2016 guideline on diagnosis and treatment of cardiac sarcoidosis-digest version. Circ J. 2019;83(11):2329–2388. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-19-0508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Birnie DH, Sauer WH, Bogun F, Cooper JM, Culver DA, Duvernoy CS, et al. HRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of arrhythmias associated with cardiac sarcoidosis. Heart Rhythm. 2014;11(7):1305–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2014.03.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ribeiro Neto ML, Jellis C, Hachamovitch R, Wimer A, Highland KB, Sahoo D, et al. Performance of diagnostic criteria in patients clinically judged to have cardiac sarcoidosis: Is it time to regroup? Am Heart J. 2020;223:106–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cacoub P, Chapelon-Abric C, Resche-Rigon M, Saadoun D, Desbois AC, Biard L. Cardiac sarcoidosis: a long term follow up study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(9):e0238391. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kandolin R, Lehtonen J, Airaksinen J, Vihinen T, Miettinen H, Ylitalo K, et al. Cardiac sarcoidosis: epidemiology, characteristics, and outcome over 25 years in a nationwide study. Circulation. 2015;131(7):624–632. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fritz D, van de Beek D, Brouwer MC. Clinical features, treatment and outcome in neurosarcoidosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Neurol. 2016;16(1):220. doi: 10.1186/s12883-016-0741-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stern BJ, Royal W, Gelfand JM, Clifford DB, Tavee J, Pawate S, et al. Definition and consensus diagnostic criteria for neurosarcoidosis: from the Neurosarcoidosis Consortium Consensus Group. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(12):1546–1553. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carlson ML, White JR, Espahbodi M, Haynes DS, Driscoll CLW, Aksamit AJ, et al. Cranial base manifestations of neurosarcoidosis: a review of 305 patients. Otol Neurotol. 2015;36(1):156–166. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cação G, Branco A, Meireles M, Alves JE, Mateus A, Silva AM, et al. Neurosarcoidosis according to Zajicek and Scolding criteria: 15 probable and definite cases, their treatment and outcomes. J Neurol Sci. 2017;379:84–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2017.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zajicek JP, Scolding NJ, Foster O, Rovaris M, Evanson J, Moseley IF, et al. Central nervous system sarcoidosis–diagnosis and management. QJM Mon J Assoc Phys. 1999;92(2):103–117. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/92.2.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jamilloux Y, Néel A, Lecouffe-Desprets M, Fèvre A, Kerever S, Guillon B, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients with sarcoidosis. Neurology. 2014;82(15):1307–1313. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cohen-Aubart F, Galanaud D, Grabli D, Haroche J, Amoura Z, Chapelon-Abric C, et al. Spinal cord sarcoidosis: clinical and laboratory profile and outcome of 31 patients in a case-control study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2010;89(2):133–140. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181d5c6b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chazal T, Costopoulos M, Maillart E, Fleury C, Psimaras D, Legendre P, et al. The cerebrospinal fluid CD4/CD8 ratio and interleukin-6 and -10 levels in neurosarcoidosis: a multicenter, pragmatic, comparative study. Eur J Neurol. 2019;26(10):1274–1280. doi: 10.1111/ene.13975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paule R, Denis L, Chapuis N, Rohmer J, Hadjadj J, London J, et al. Lymphocyte Immunophenotyping and CD4/CD8 Ratio in Cerebrospinal Fluid for the Diagnosis of Sarcoidosis-related Uveitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2019;31:1–9. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2019.1678647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bridel C, Courvoisier DS, Vuilleumier N, Lalive PH. Cerebrospinal fluid angiotensin-converting enzyme for diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2015;285:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2015.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dumas JL, Valeyre D, Chapelon-Abric C, Belin C, Piette JC, Tandjaoui-Lambiotte H, et al. Central nervous system sarcoidosis: follow-up at MR imaging during steroid therapy. Radiology. 2000;214(2):411–420. doi: 10.1148/radiology.214.2.r00fe05411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bihan H, Christozova V, Dumas J-L, Jomaa R, Valeyre D, Tazi A, et al. Sarcoidosis: clinical, hormonal, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) manifestations of hypothalamic-pituitary disease in 9 patients and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2007;86(5):259–268. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e31815585aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jachiet V, Lhote R, Rufat P, Pha M, Haroche J, Crozier S, et al. Clinical, imaging, and histological presentations and outcomes of stroke related to sarcoidosis. J Neurol. 2018;265(10):2333–2341. doi: 10.1007/s00415-018-9001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Voortman M, Drent M, Baughman RP. Management of neurosarcoidosis: a clinical challenge. Curr Opin Neurol juin. 2019;32(3):475–483. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leclercq M, Sené T, Chapelon-Abric C, Desbois AC, Domont F, Maillart E, et al. Prognosis factors and outcomes of neuro-ophthalmologic sarcoidosis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2020;9:1–8. doi: 10.1080/09273948.2020.1834585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Joubert B, Chapelon-Abric C, Biard L, Saadoun D, Demeret S, Dormont D, et al. Association of prognostic factors and immunosuppressive treatment with long-term outcomes in neurosarcoidosis. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(11):1336–1344. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Berliner AR, Haas M, Choi MJ. Sarcoidosis: the nephrologist’s perspective. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48(5):856–870. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Baughman RP, Janovcik J, Ray M, Sweiss N, Lower EE. Calcium and vitamin D metabolism in sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2013;30(2):113–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Baughman RP, Papanikolaou I. Current concepts regarding calcium metabolism and bone health in sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2017;23(5):476–481. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nathan N, Marcelo P, Houdouin V, Epaud R, de Blic J, Valeyre D, et al. Lung sarcoidosis in children: update on disease expression and management. Thorax. 2015;70(6):537–542. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-206825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cremers J, Drent M, Driessen A, Nieman F, Wijnen P, Baughman R, et al. Liver-test abnormalities in sarcoidosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24(1):17–24. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32834c7b71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Modaresi Esfeh J, Culver D, Plesec T, John B. Clinical presentation and protocol for management of hepatic sarcoidosis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;9(3):349–358. doi: 10.1586/17474124.2015.958468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kucharz EJ. Osseous manifestations of sarcoidosis. Reumatologia. 2020;58(2):93–100. doi: 10.5114/reum.2020.95363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]