Abstract

Purpose of Review

The aim of this narrative review was to summarize the evidence evaluating the possibilities and limitations of self-hypnosis and mindfulness strategies in the treatment of obesity.

Recent Findings

Psychological factors, such as mood disorders and stress, can affect eating behaviors and deeply influence weight gain. Psychological approaches to weight management could increase the motivation and self-control of the patients with obesity, limiting their impulsiveness and inappropriate use of food. The cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) represents the cornerstone of obesity treatment, but complementary and self-directed psychological interventions, such as hypnosis and mindfulness, could represent additional strategies to increase the effectiveness of weight loss programs, by improving dysfunctional eating behaviors, self-motivation, and stimulus control.

Summary

Both hypnosis and mindfulness provide a promising therapeutic option by improving weight loss, food awareness, self-acceptance of body image, and limiting food cravings and emotional eating. Greater effectiveness occurs when hypnosis and mindfulness are associated with other psychological therapies in addition to diet and physical activity. Additional research is needed to determine whether these strategies are effective in the long term and whether they can be routinely introduced into the clinical practice.

Keywords: Hypnosis, Mindfulness, Obesity, Self-conditioning, Self-help

Introduction

Obesity is a public health burden [1]. Excess weight is associated with an increased risk for cardiometabolic diseases, cancer, and mortality [2] as well as a range of negative biopsychosocial outcomes and psychiatric symptoms, such as depression and anxiety [3]. The physiopathology of obesity is complex, involving the deregulation of appetite and energy metabolism, genetic, metabolic, biochemical, cultural, and psychosocial factors [4].

Unhealthy diets and poor exercise are considered the main environmental causes of excess weight; psychological factors can indeed heavily influence weight gain [5]. Stress and mood disorders have been linked to increased search for high-density foods, decreased exercise, and altered eating behaviors [5]. “Emotional eating” is the inclination to eat in response to negative emotions, and “external eating” is the tendency to eat in response to external food cues; these behaviors are associated with unhealthy food choices and weight gain [6]. Furthermore, higher rates of depression, low self-esteem, anxiety, eating disorders (binge eating disorder, night eating syndrome, etc.), and impaired health-related quality of life are reported in individuals with obesity [7]. The reward circuits seem to be altered, with a preference for immediate rewards (e.g., high-fat, high-carbohydrate, salty foods) over long-term benefits (e.g., weight management) [8]. Uncontrolled daily stress may alter brain reward/motivation pathways involved in seeking hyperpalatable foods [9]. Indeed, inappropriate eating behaviors may be the result of a poor inhibitory control and hedonic homeostatic dysregulation, which may predispose to overeating palatable food in the absence of hunger [8], up to a condition of food addiction with greater emotion dysregulation, impulsivity, and food cravings [10]. The conditioning model of food cravings states that cravings can develop from pairing consumption of certain foods with external (e.g., watching television) or internal (e.g., feeling sad) stimuli [11].

The management of obesity usually includes lifestyle intervention only as the first approach, even if, in specific cases, based on the severity of the clinical condition, pharmacotherapy may be necessary early for the patient care. The attrition from weight management programs, however, affects most patients [12], and obesity treatment achieves poor results, with a high rate of relapse and weight recovery [2]. The search for approaches addressing the associated psychological problems and potentially increasing the motivation and self-control of the patients with obesity, limiting their impulsiveness and inappropriate use of food, are therefore important. Psychological interventions, particularly behavioral and cognitive-behavioral strategies, have been reported to be beneficial on weight loss in adults with overweight and obesity, especially when combined with dietary and exercise strategies [13]. The cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has proven to be effective in determining weight loss by increasing healthy eating and exercise, improving psychologically related eating behaviors (i.e., cognitive restraint and emotional eating) [14] as well as cognitive factors, such as self-motivation, self-monitoring, and stimulus control [15, 16]. Self-regulation (or self-control) can be defined as the suppression of a behavioral impulse toward a “lower-level” goal in the interest of pursuing a “higher-level” goal [17]. Thus, dietary, and physical activity adherence demands self-regulation, which depends on the ability to maintain a continued awareness of behavior. The lack of this awareness and its consequences result in “mindless” eating and activities [16].

A great interest is related to self-directed psychological interventions that do not require the constant presence of a health professional (“self-help”) [18], while employing the use of manuals, commercial products, technology, supportive peers, or occasional professional assistance [19]. These strategies aim to train patients in skills that enhance self-control such as goal setting, regulation, self-monitoring and evaluation, problem solving skills, and coping strategies for high-risk situations [17]. Several therapeutic approaches alone or in combination include psychodynamic, behavioral, cognitive-behavioral, mindfulness, and hypnotic therapy. The purpose of this narrative review is to focus on the application of hypnotherapy and mindfulness as self-help approaches in the treatment of obesity, replacing or supporting CBT.

Methods

The following databases were queried: PubMed (National Library of Medicine), Psychological Information Database Medical, Psychiatry, Mental Health Disorders (PsycInfo), Cochrane Library. The search strategy was performed using the following keywords: obesity OR overweight OR weight loss AND self-conditioning, self-control, self-help, self-regulation, strategies, hypnosis, hypnotherapy, hypno-behavioral therapy, mindfulness, cognitive behavioral therapy, psychological treatment, behavioral education. The filters “humans” and “adults” were used. Hand searching the references of the identified studies and reviews was carried out too.

Hypnosis

History and Definitions

Hypnosis has been considered as the oldest psychotherapy, being practiced by the ancient Egyptians since the fifteenth century BC. The rediscovery of hypnosis in 1700s is due to the German doctor F.A. Mesmer who noted beneficial effects on the patient discomfort by entering into empathic resonance with him [20]. In 1841 the English doctor J. Braid introduced the term “hypnotism,” based on the physiology of the brain [21, 22]. Due to the theories of J.M. Charcot and his most famous student, S. Freud, who considered the hypnosis as a pathological phenomenon, an artificial hysterical neurosis with a limited therapeutic value, the hypnotic method was abandoned [20, 23, 24]. During the world wars, hypnosis experienced a renewed interest, as it was applied to treat the war traumatic neuroses. More recently, the psychiatrist M. Erickson (1901–1980), by elaborating the concept of the unconscious, applied the clinical hypnosis in the re-elaboration of negative or traumatic events associated with adverse symptoms or diseases [20–25].

Although hypnosis acquired scientific dignity among scientists and clinicians, no agreement on its definition has been achieved [20, 25]. The British Psychological Society defines “hypnosis” as a waking state in which the individual attention is focused away from his/her surroundings and absorbed by inner experiences such as feelings, cognitions, and imagery, which can be influenced by the interaction with a “hypnotist” [26]. According to the American Psychological Association, hypnosis is a procedure during which a hypnotist guides the subject to respond to suggestions for changes in subjective experience, alterations in perceptions, sensations, emotions, thoughts, or behaviors [27, 28]. The neo-Ericksonians defined hypnosis as a strategy that explores the deeper causes of the disorders rather than aiming at the remission of the symptoms; indeed, during the hypnotic trance, the unconscious offers the possibility of solutions to problems or conflicts [20, 25–29].

The Rationale for Using Hypnosis in the Treatment of Obesity

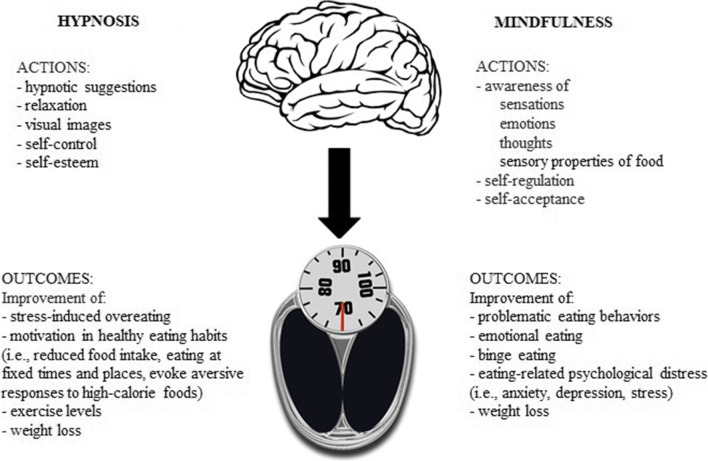

Hypnosis has been successfully used as an anti-stress and relaxation strategy to treat many chronic conditions exacerbated by negative emotions and social factors (e.g., quitting smoking [30]), chronic digestive diseases [31], cancer-related symptoms in palliative care setting [32], acute and chronic pain [33]. Individuals can practice hypnosis on their own (self-hypnosis); hypnotherapy (either alone or in addition to other psychotherapies, such as cognitive-behavioral techniques) has been involved in the obesity multidimensional approach to increase self-control, to improve exercise levels, to boost self-esteem, and to strengthen motivation in changing eating habits [34]. Stress-induced overeating and reward from comfort food can be considered an attempt at self-medication to relieve the negative emotions and depressive state associated with chronic psychological stress [35]. Hypnosis as a strategy for stress management could be an important component in the approach toward stress-induced overeating and impaired reward mechanisms characterizing many patients with obesity (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Hypnosis and mindfulness as strategies for stress management in obesity treatment

Studies on Hypnosis and Weight Management

The application of hypnosis for weight reduction has been reported in the literature since the 1950s [36]. Hypnotized state was initially induced by experienced therapists; indeed, self-hypnosis and the autonomous use of supplemental materials (i.e., home audio tapes) have been encouraged from the earliest years of hypnotherapy to reinforce the therapist suggestions and provide additional support after the formal treatment completion [37]. With hypnotic suggestions (i.e., verbal, and non-verbal communications), people can be taught to reduce food intake, eat at fixed times and places, restrict the purchase of food supplies, and evoke aversive responses, such as sickness and disgust, when eating high-calorie foods [34]. Clinical trials comparing cognitive-behavioral therapy alone versus cognitive behavioral therapy plus hypnosis for various conditions, including obesity, were first reviewed in 1990s in two meta-analyses [38, 39]. Kirsch [38] analyzed 6 weight loss trials and reported an improvement in weight loss with hypnosis (weighted mean effect size=1.96) and no weight regain after hypnosis even at 2-year follow-up. However, this meta-analysis [38] displayed several methodological limitations (lack of data availability for some studies, high risk of bias of the included research, short follow-up for most of the included studies, high drop-out rates). Allison [39] re-analyzed the same 6 weight loss trials and found that hypnosis, as an adjunct to CBT, produced only a small effect on average (weighted mean effect size=0.28) [39]. Kirsch [40], then, re-conducted the metanalysis and reported an effect size of 0.98, which was different from previous results, but still indicative of a benefit from the combination of hypnosis with CBT. The correlation between the efficacy of hypnosis in weight loss program and the degree of hypnotizability is highly controversial, since not all studies found such a relationship. The mechanism by which hypnotherapy might work is the processing of problems related to nutrition through the detection and integration of neglected resources, relaxation, hypnotic suggestions, and visual images [41]. In 1986, a RCT assessed in 60 overweight women the effectiveness of 1-month hypnosis on weight loss, either alone (Hy; n=17 patients) or plus audiotapes (Hy-T; n=17 patients), compared to a wait-listed control group (n=20 patients) [42]. When compared to controls, both the Hy and Hy-T interventions significantly reduced body weight after 1 month (−3.62 kg Hy; −2.96 kg Hy-T; +0.68 kg controls; p<0.01) and 6 months (−7.76 kg Hy; −8.00 kg Hy-T; −0.22 kg controls; p<0.01) [42]. In 1998, 60 individuals with obesity and sleep obstructive apnea (80% males) were randomized to receive either hypnotherapy for the reduction of stress or hypnotherapy for reducing energy intake or dietary advice alone for 18 months [43]. All the three groups lost 2–3% of their initial body weight at 3 months, while, at 18 months, only hypnotherapy for stress reduction determined a significant (p<0.02), but small weight loss (3.8 kg) compared to baseline. Noteworthy the dropout rate was 25% [43], thus requiring caution in the interpretation of these results. In 2014, two types of hypnotherapies were compared in 60 females with obesity by a parallel RCT: hypno-behavioral therapy (HypBe) (a combination of hypnotherapy—i.e., hypnotic trances—plus behavioral therapy—i.e., behavioral exercises, role-playing, and homework) and hypno-energetic (HypEn) therapy (a therapy enhancing the hypno-behavioral strategies with acupressure, that is, the manual stimulation of acupuncture in the related points) [44]. Both treatments consisted of 12 sessions lasting 120 min over an 8.5-month period, and participants were assessed at the beginning and the end of the treatment, as well as after 6-month follow-up. Regardless of the hypnotherapy received, initial weight and BMI were significantly reduced from the beginning to the end of treatment (−2.4 kg, p<0.01 and −0.8 kg/m2, p<0.01 within the HypBe group; −3.1 kg, p<0.01 and −1.1 kg/m2, p<0.01 within the HypEn group), but significant weight and BMI reductions from the end of treatment to the follow-up (−2.2 kg, p<0.01 and −0.8 kg/m2, p<0.01) and significant improvements in eating behaviors, and several aspects of body concept, such as physical efficiency, self-acceptance of the body/physical appearance/sexuality, were observed in the HypEn group only [44]. A systematic review of 5 meta-analyses of RCTs demonstrated the efficacy of medical hypnosis in the reduction of pain and emotional stress during medical interventions (34 RCTs, 2597 patients) [45]. Indeed, the application of hypnotherapy aims to emotionally restructure stressful events and sensations and cognitive–affective patterns (through minimization, reinforcement, new conditioning), and to improve problem management by giving the patient access to his own resources, thus facilitating changes in behaviors [45]. Milling performed two meta-analyses comparing hypnosis with a control condition including standard care, attention control, or no-treatment (14 trials) and CBT alone with CBT augmented by hypnosis (11 trials) over a relatively short span of time (average length of the hypnosis interventions in the two samples of trials ≈ 6.5 weeks) [46••]. Hypnosis demonstrated to be more effective in producing weight loss when compared to the control condition (effect sizes=1.58 lb, p≤0.001 at the end of the active treatment in 14 trials, and 0.88 lb, p ≤0.001 in 6 trials with longer follow-up) [46••]. Similarly, hypnosis plus CBT compared to CBT alone induced an increased weight loss (effect sizes=0.25 lb, p≤0.05 in 11 trials at the end of the intervention and 0.80 lb, p≤0.001 in 12 trials with longer follow-up of ≈ 12 weeks) [46••]. Recently, a RCT evaluated the effectiveness of self-hypnosis added to standard care in determining weight loss in patients with severe obesity [47]. A rapid-induction phase was used to allow the patient to go into hypnosis in a few minutes, then participants were trained to enter into hypnosis in complete autonomy daily, before each meal [47]. In the self-hypnosis arm, a significant improvement in quality of life, satiety, and inflammation occurred with respect to controls with standard care, without a significant difference in weight loss (−6.5-kg intervention group, n=44 patients; −5.6-kg control group, n=42 patients; p=0.79). Indeed, within the intervention group, habitual hypnosis users showed a greater weight loss than those who practiced self-hypnosis less frequently (−9.6 kg, ≥ once per day; −7.5 kg <once per day; +0.2 rarely or none; p=0.001) [48]. The same research group reported an acute effect on the brain peptides involved in the hunger/satiety regulation after a hypnosis-induced hallucinated meal in highly hypnotizable individuals, thus suggesting the potential role of hypnosis on central appetite modulation [49•].

In conclusion, 11 randomized trials about the effect of hypnosis as an adjunctive strategy to lose weight were published; out of them, 9 [42–44, 48, 50–54] reported overall beneficial effects, even if mild or moderate and more evident after a longer follow-up [42, 44, 50, 51, 53], while only 2 [55, 56] failed to find any benefits.

A few ongoing trials studying the use of hypnosis in the treatment of obesity [57, 58] are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Ongoing trials on hypnosis and obesity [57]

| Study title | Country | Intervention | Status | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypnosis, Self-hypnosis, and Weight Loss in Obese Patients | France |

- Dietetic counseling - Hypnosis and self-hypnosis |

Completed | No published data retrieved |

| Efficacy of Self-hypnosis for Weight Loss in Type 2 Diabetics | USA |

- Self-hypnosis - CDE training - No special treatment (control) |

Completed | After 1 year, weight loss was −2.7 kg (self-hypnosis; n=36 patients), −1.8 kg (CDE; n=38 patients), and −0.45 (controls; n=102 patients), p=0.001 [58] |

| Changing Eating Behaviours of Healthy Adults Through Hypnosis | Romania |

- Hypnosis with amnesia suggestions - Hypnosis with cognitive rehearsal suggestions - Hypnosis with memory substitution suggestions - Hypnosis with induction only |

Completed | No published data retrieved |

| The Impact of the Hypnosis on the Loss of Weight at Patients in Failure of Bariatric Surgery | France |

- Hypnosis - Standard care |

Recruiting | - |

| Hypnosis and States of Change to Promote Weight Loss | Lebanon | - Listening to an audiotape | Recruiting | - |

| Changing Eating Behaviour Using Cognitive Training | Romania |

- Hypnosis - Food inhibition training - Control |

Not yet recruiting | - |

CDE Certified Diabetes Educator

Limitations of Hypnosis as Self-Help Strategies to Lose Weight

Although hypnosis has been reported as a successful approach to promote weight loss in addition to lifestyle and/or psychological interventions, the overall number of related studies was low, and most trials were very old, i.e., published in the 1980s [42, 50–53, 55, 56]. Furthermore, the methodological quality was limited; most studies had an observational design, a low number of enrolled patients, short duration of the intervention, and only a few reported follow-up data. Patient recruitment might be a challenge in hypnosis-based interventions, the individual hypnotizability is still a highly debated question [41], and the available papers reported an increased female participation, with high rates of drop-out or discontinuation of the intervention [43, 44, 48]. Due to the small sample sizes, some studies might lack the statistical power to detect differences between the interventions [54], and divergent effect size values were reported in meta-analyses [38–40, 44, 46]. Therefore, at present, the evidence toward the efficacy of hypnosis as a strategy for losing weight is scarce.

New Technologies

Due to the great interest in self-managed strategies that could help individuals to lose weight, an increasing number of internet websites, videos, and smartphone applications dedicated to hypnosis are available. A review of 407 hypnosis applications for smartphones and tablets reported that the most frequently proposed goal was weight loss (22.6%), by delivering hypnosis via audio track, visual means (i.e., reading the text of a hypnosis script), or both [59]. However, only a few applications mentioned the hypnotist being a “doctor,” and none reported being evidence-based (empirically tested); therefore, concern about their safety and efficacy was reported [59]. Further rigorous studies to support the effectiveness of hypnosis applications are needed in order to develop scientifically validated tools for consumers.

Mindfulness

History and Definitions

Mindfulness practice has a very long history, dating back to over 2500 years ago. It was part of different religious and secular traditions, such as Hinduism, Buddhism, and yoga [60], but became known in the West in the 1970s thanks to Kabat-Zinn, who abstracted the concept from its original religious context [61]. Mindfulness could be defined as a non-judgmental awareness and acceptance of one’s moment-to-moment experience [62]. As described by Bishop [63], mindfulness consists of two main components: the self-regulation of attention and a particular orientation toward the experience. Self-regulation of attention concerns the non-judgmental observation and awareness of physical sensations, affective states, and thoughts as they arise. Orientation to experience refers to the attitude of acceptance and curiosity toward one’s experience. Mindfulness has been described as a set of skills that can be learned through practices like meditation and therapeutic interventions, the Mindfulness-Based Interventions (MBIs). MBIs are usually conducted in groups, and participants are guided by instructors who have received specific training and have a personal meditation background, but the fundamental and distinctive element remains the experiential learning that each participant acquires during the course by means of daily training.

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Program (MBSR) training is the most common form of MBIs and consists of eight 2.5-h weekly sessions and one 7-h day of silence [62, 64]. This training aims at improving the capacity of attention and non-judgmental awareness and could teach people to break with the maladaptive patterns of thinking and behavior. These maladaptive strategies are believed to contribute to the onset and maintenance of many emotional disorders [63]. Alongside with MBSR, Segal [65] proposed a Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) program, that is an approach which brings together elements from MBSR and from Cognitive Therapy, aiming to prevent depressive relapse and depressive symptoms. Mindfulness-Based Eating Awareness Training (MB-EAT) is a specific mindful eating training program integrating MBSR and CBT components [66, 67]. It was originally designed for binge-eating disorder, but it was also implemented in non-clinical populations to promote weight loss. MB-EAT is aimed at improving eating behavior and more generally at developing a healthier and more balanced attitude toward food. Attention is also paid to stress related to eating and dysfunctional modes of eating behavior (e.g., emotional, and external eating).

The Rationale for Using Mindfulness-Based Interventions in the Treatment of Obesity

Mindfulness practice has been repeatedly reported to decrease global psychological distress and improve overall mental health [68, 69]. MBIs have also shown their effectiveness in decreasing anxiety, as well as improving depressive symptoms [70], by ameliorating self-regulation [71].

Different dysfunctional eating behaviors, such as binge eating, emotional eating, external eating, and eating in response to food cravings, have been linked also to weight regain after successful weight loss [72]. Furthermore, the distracted and unaware eating impairs the memory of the meal and increases further food intake, suggesting that the attentive and mindful experience of a meal is necessary for adequate satiation mechanisms and proper inhibitory controls [35]. The different theoretical models for explaining problematic eating behaviors suggest the association between maladaptive responses to internal and external stimuli and the dysregulation of eating behaviors [72, 73]. Several studies have also indicated stress and negative emotions among the principal determinants of unhealthy eating behavior [74–76]. As mindfulness and mindful eating promote self-regulation by better management of negative emotional states and stress, and promote awareness of the sensations associated with eating, these trainings can be used as strategies to help people to diminish the reactivity to dysfunctional food cues (e.g., advertising, boredom, anger, anxiety) [77] and to favor weight control (Fig. 1).

Studies on Mindfulness-Based Interventions and Weight Management

The first integrative review on the role of MBIs in the treatment of obesity was published in 2013 [78]. While denoting the paucity of studies conducted up to that time, this review provided a general overview of the use of MBIs either as stand-alone treatment or as complementary to other traditional approaches in the treatment of obesity and eating disorders. O’Reilly [72] conducted a literature review to investigate the effects of MBIs to treat obesity-related eating behaviors (e.g., binge eating, emotional eating, and external eating) on 21 primary studies, showing that in 86% of the included studies there was an improvement in targeted eating behaviors. The first systematic review [79] included 14 interventional studies and found a reduction in binge and emotional eating after mindfulness meditation training. Another systematic review [80] reported that 13 of the 19 included studies showed a beneficial effect of MBIs on weight loss, although the specific degree to which increased mindfulness was a mechanism leading to weight loss was not identified. In fact, mixed results were found regarding the association between mindfulness change (i.e., after MBIs) and weight loss. Further research to investigate the specific mechanisms involved in the relationship between mindfulness and weight loss was recommended. Tapper [81] attributed the beneficial effects of MBIs on weight loss and impaired eating behaviors to both the present moment awareness of the sensory properties of food that can reduce further food intake, and the decentering strategies that may help individuals resist desired foods. The first review that considered the change in mindfulness as a primary outcome and mindful eating as a measured variable was performed by Dunn in 2018 [82]; the authors strongly supported the use of mindfulness in weight management programs, also suggesting a potential benefit for the treatment of obesity. A very recent systematic review [83], including 9 RCTs, showed that in most of the included studies, there was a positive effect of MBIs on reducing emotional eating, binge eating, and weight and shape concern. The mechanisms of action highlighted were the increase in awareness of internal experiences and automatic patterns and the improvement in self-acceptance and emotional regulation, which led to a reduction of problematic eating behaviors. Moreover, to date six meta-analyses were published evaluating the efficacy of MBIs for weight management, obesity, and/or problematic eating behaviors. Overall, their results showed that MBIs have beneficial effects on both obesity-related eating behaviors [84, 85] and binge eating [86, 87]. In particular, moderate-to-large effect sizes (Hedge’s g ranging from 0.70 to 1.08) were found for obesity-related eating behaviors [84, 85], while large effect sizes have been shown for binge eating (Hedge’s g ranging from −0.90 to −1.08) [86, 87]. The effect on weight loss was found to be moderate in both Carrière [84] and Rogers [85] meta-analyses, with Hedge’s g =0.42 and Hedge’s g =0.47, respectively. The greater effects on weight loss were found in studies that used a combination of informal and formal meditation practice rather than formal meditation practice alone [84]. In another meta-analysis [88], a significant weight loss effect of MBIs was found when compared with non-intervention controls (standardized mean difference: −0.348 kg, 95% CI: −0.591 to −0.105, p = 0.005), showing that the MBI effect was similar to common diet programs. Lawlor [89] recently performed a network meta-analysis to evaluate the effect of third-wave cognitive behavior therapies for weight management. Their result pointed out that Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) intervention was the intervention with the greatest effect on weight loss as compared to standard behavioral programs, with long-lasting effects at 12- and 24-month follow-up. Moderate effects of MBIs were also revealed for the impact on eating-related psychological distress, with a Hedge’s g =0.64 for depression and 0.62 for anxiety [85]. Several other trials on mindfulness in weight management are ongoing [90–92] (Table 2). Recent studies conducted in this area, which were not included in the reviews and meta-analyses above described, are shown in Table 3 [93–107]. Sixteen studies were retrieved, including 9 RCTs and 7 intervention studies without a control group. Overall, these studies showed promising findings supporting the effectiveness of MBIs to improve problematic eating behaviors and weight management.

Table 2.

Ongoing trials on mindfulness and obesity [90]

| Study title | Country | Intervention | Status | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect of Self-Regulation with Mindfulness Training on Body Mass Index and Cardiovascular Risk Markers in Obese Adults | USA |

- Dietary counseling - Mindfulness training program |

Completed | No published data retrieved |

| Psycho-sensorial Mindfulness and Top-down Control: Mindfulness Program for Obese Patients in Preparation to Bariatric Surgery | France |

- Bariatric surgery with mindfulness program - Bariatric surgery without mindfulness program |

Completed | No published data retrieved |

| Nutritional Video Intervention Using Mindfulness-based Principles | USA |

- Healthy cart and stress management videos (2-video group) - Healthy cart video (1 video group) |

Completed | At 2-month follow-up, knowledge improved in both intervention groups (p<0.001). The 2-video group (n=29 women) improved more in self-efficacy and use of a shopping list (both p<0.05) and purchased more healthy foods (p<0.05) than the 1-video group (n=39 women) [91]. |

| Engaging Motivation for the Prevention of Weight Regain | USA |

- Mindfulness-based weight loss maintenance - Standard behavioral weight loss maintenance |

Completed | No published data retrieved |

| The Effects of Mindfulness Training on Eating Behaviors and Food Intake | USA | - Mindful eating and living course | Completed | No published data retrieved |

| Mindful Eating and Living for Obese Women | USA |

- Mindful eating and living - Active weight loss control |

Completed | No published data retrieved |

| Craving and Lifestyle Management Through Mindfulness Study | USA | - Craving and lifestyle management through mindfulness | Completed | Outcome data are presented on clinicaltrials.gov [92], but no published data were retrieved. |

| Mindful Construal Diaries: Can the MCD Increase Mindfulness and Mindful Eating in Bariatric Surgery Patients | United Kingdom | - Mindful construal diary (MCD) | Completed | No published data retrieved |

| Food Insecurity, Obesity, and Impulsive Food Choice | USA |

- Mindful eating - Nutrition DVD |

Completed | No published data retrieved |

| Trauma Exposure, Emotion Regulation and Eating Pathology in Obese Patients | France | Not reported | Completed | No published data retrieved |

| Efficacy of Mindful Tai Chi on Obese or Overweight Adults: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial | USA |

- Mindful Tai Chi intervention - Mindfulness meditation - Mall walking - Weekly discussion |

Terminated | - |

| The Role of Values, Acceptance, and Mindfulness Strategies in Long Term Weight Management | Canada | - Acceptance and commitment therapy | Recruiting | - |

| Project Activate: Mindfulness and Acceptance Based Behavioral Treatment for Weight Loss | USA |

- Behavioral treatment - Mindful acceptance - Values - Mindful awareness |

Recruiting | - |

| Mindfulness and Compassion-based Programs on Food Behavior of Patients with Weight Regain After Bariatric Surgery | Brazil |

- Mindfulness-based health promotion + treatment as usual - Attachment-based compassion therapy + treatment as usual - Treatment as usual |

Recruiting | - |

| Effect of a Group Intervention Program Based on Acceptance and Mindfulness on the Physical and Emotional Well-being of Overweight and Obese Individuals | Spain |

- Standard + acceptance and mindfulness-based group intervention program - Standard |

Active, not recruiting | - |

| The Impact of 8 Weeks of Digital Meditation Application and Healthy Eating Program on Work Stress and Health Outcomes | USA |

- Meditation - Healthy eating - Meditation + healthy eating |

Active, not recruiting | - |

| Brief mHealth Self-Compassion Intervention on Internalized Weight Bias | USA | - Self-compassion mindfulness practice | Active, not recruiting | - |

BMI body mass index

Table 3.

Recent RCT on mindfulness in weight management programs.

| Author, year [ref] | Study design | Participants | Number | Mindfulness strategy | Main results | Specific results on weight loss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daubenmier, 2020 [93] | RCT | Adults with obesity | 194 |

n=100: mindfulness training (meditation, mindful eating, mindful walking) with diet-exercise intervention n=94: only diet-exercise intervention |

Mindfulness participants showed significantly greater maintenance of challenge-related emotions and cardiovascular reactivity patterns, independently from changes in BMI | No significant group differences between intervention groups were found in 3-month weight loss. |

| Radin, 2020 [94] | RCT | Adults with obesity | 194 |

n=100: mindfulness training (meditation, mindful eating, mindful walking) with diet-exercise intervention n=94: only diet-exercise intervention |

Participants with higher compulsive eating at baseline randomized to the mindfulness intervention had greater improvements in fasting blood glucose at 18 months | Weight loss at 18 months in both intervention groups was associated with a reduction in stress and compulsive eating at 6 months. |

| Levin, 2020 [95] | RCT | Adults with overweight and obesity | 79 |

n=39: ACT on health online course and coaching calls n=40: waiting list |

Participants in the ACT condition improved significantly the healthy eating index and the outcomes assessing self-reported eating behaviors, weight, mental health, weight self-stigma, and psychological inflexibility | A greater improvement on self-reported weight was found in participants assigned to ACT condition than the waiting list. |

| Czepczor-Bernat, 2020 [96] | Intervention study | Adult women with overweight and obesity | 184 | n=184 mindful eating | Mindful eating was a significant moderator for emotional eating, and restrictive eating, but not for uncontrolled eating; mindful eating was a significant moderator for the relationship between negative emotions and emotional eating, restrictive eating, and uncontrolled eating | - |

| Felske 2020, [97] | Proof-of -concept intervention study | Adults with obesity seeking bariatric surgery | 56 | n=56: MII sessions with cognitive, behavioral, and psychoeducational components | Improvements in addictive-like eating, binge eating, emotional eating, and grazing were observed from pre- to post-MII and at 12-week follow-up | - |

| Schnepper, 2019 [98] | RCT | Individuals motivated to improve their eating behavior or lose weight | 46 |

n=23: mindfulness-based training and prolonged chewing intervention n=23: waiting list |

Participants in the intervention group significantly reduced BMI, emotional eating, external eating, and food cravings. | The intervention decreased BMI, and this loss was maintained during 4 weeks of follow-up. |

| Pinto-Gouveia, 2019 [99] | Intervention study | Women with overweight or obesity and binge eating disorder | 31 | n=31: BEfree program, a 12-session group intervention that integrates psychoeducation, mindfulness, compassion, and value-based action | Participants in Befree program decreased in binge eating severity, eating psychopathology, external shame, self-criticism, psychological inflexibility, body image cognitive fusion, and increased self-compassion and engagement with valued actions. These results were maintained at 3- and 6-month follow-up. | A significant decrease in BMI after intervention was observed, even though weight loss was not identified as BEfree’s primary outcome. |

| Jastreboff, 2018 [100] | Pilot RCT |

Low-income parent-child dyads with parent obesity |

42 dyads |

n=20: mindfulness-based parent stress group intervention (parenting mindfully for health) + nutrition and physical activity counseling (PMH+N) n=22: control group intervention (C+N) |

Compared with the C+N group, participants in the PMH+N group demonstrated a significant reduction of parental emotional eating rating. Only participants in C+N showed a significant increase in child body mass index percentile during treatment. | Findings indicate a greater increase in child BMI percentile for the C+N group vs the PMH+N group at post intervention. No significant differences between groups were found for parent BMI. |

| Hanson, 2018 [101] | Intervention study | Patients attending a tier 3-based obesity and weight-management service | 66 |

n=33: mindfulness-based group intervention (mindfulness-based eating behavior strategies taught in four group sessions) n=33: retrospective control group |

Participants in the mindfulness-based group intervention significantly improved in self-reported eating behavior (particularly fast-foodism) and in self-esteem and confidence in self-management of body weight. | A significant weight loss (3.06 kg, SD 5.2 kg) over 6 months was observed in the mindfulness group as compared to the control group. |

| Wnuk, 2018 [102] | Intervention study (feasibility pilot study) | Post-bariatric surgery women | 28 | n=28: mindfulness-based eating awareness training (MB-EAT) | Significant reduction of depression and improvement in emotion regulation were observed. The amount of mindfulness practice between sessions resulted associated with statistically significant improvements in emotional eating in response to anger. | Participants maintained their BMIs from pre- to post-intervention. |

| Spadaro, 2017 [103] | RCT | Overweight and obese adults | 46 |

n=24: standard behavioral weight loss program (SBWP) only n=22: SBWP + mindfulness meditation (MM) |

Participants in the SBWP+MM group significantly reduced their weight and improved eating behaviors and dietary restraint, as compared to SBWP alone. | Enhanced weight loss by 2.8 kg was observed in the SBWP+MM group as compared to SBWP. |

| Adler, 2017 [104] | RCT | Adults with a BMI in the range 30–45 kg/m2 | 194 |

n=100: mindfulness-based eating intervention (with meditation practices modeled on MBSR, and mindful eating practices modeled on the Mindfulness-Based Eating Awareness Training program) n=94: progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) |

No significant differences found in sleep quality between the participants in the mindfulness group and the active control group, despite sleep improving from baseline to 6 and 12 months in the mindfulness group. Within the mindfulness group, the amount of mindfulness practice was associated with improved sleep quality. | Both groups experienced reduction in BMI, but change in BMI from 0 to 6 months was not associated with change in sleep quality in either group. |

| Palmeira, 2017 [105] | RCT | Women with overweight or obesity | 73 |

n=36: Kg-Free intervention based on mindfulness, ACT, and compassion approaches n=37: Treatment as Usual (TAU) |

Participants in Kg-Free intervention significantly reduced weight-related negative experiences and improved their healthy behaviors, psychological functioning, and QoL, as compared to TAU. No significant differences were found between groups regarding self-compassion. | Kg-Free group revealed a reduction of BMI at post-treatment, albeit with a rather small effect size. |

| Raja-Khan, 2017 [106] | RCT | Women with overweight or obesity | 86 |

n=42: MBSR n=44: health education |

Participants in the MBSR group, as compared to the control group, showed a significant improvement in mindfulness and a significant reduction of perceived stress and fasting glucose. No significant changes in blood pressure, weight, or insulin resistance were observed. |

No significant change in weight in the MBSR group was observed. |

| Levoy, 2017 [107] | Intervention study (exploratory study) | Adult individuals | 317 | n=317 MBSR program | Participants in MBSR showed a significant reduction of emotional eating scores. Changes in mindfulness were correlated with changes in emotional eating. | There were no significant changes in BMI, and baseline BMI predicted weight changes post-MBSR. |

ACT acceptance and commitment therapy, BMI body mass index, MII mindfulness-informed, MBSR mindfulness-based stress reduction, n number, RCT randomized controlled trial, intervention, TAU treatment as usual

Limitations of Mindfulness as Self-Help Strategies to Lose Weight

The main limitations of the research conducted so far are represented by the high heterogeneity of included cohorts and the different MBIs programs among the studies. Combining clinical and non-clinical populations in the same quantitative synthesis could be problematic as MBIs may exert different effects in these two groups [84]. It is very important to consider that different types of mindfulness training could be grouped under the “MBIs” label [84]. These include combined mindfulness and cognitive behavioral therapies, MBSR, mindful eating programs such as MB-EAT, third-wave cognitive behavior therapies (e.g., ACT), dialectical behavior therapy-DBT, MBCT, compassion-focused therapy-CFT, and other different combinations of mindfulness exercises. In addition, these interventions may vary in terms of therapeutic components, length, and time of practice requested to participants. Another main limitation is the use of small sample sizes and limited follow-up assessments. In order to strengthen the evidence and evaluate possible long-lasting effects, more research with larger sample sizes and with longer follow-ups is needed. More RCTs are also needed to compare MBIs with other active interventions (e.g., conventional diet programs, standard behavioral treatment, dietary counseling) in order to assess the specific effects of mindfulness on weight management and dysfunction eating behaviors. In this regard, few studies included a valid measurement of mindfulness skills [84, 87], which is fundamental to evaluate both the extent to which increased mindfulness is an active component of treatment and the underlying mechanisms by which MBIs may improve weight management and associated psychological factors [85–87].

New Technologies

Empirical evidence suggests that MBIs can be effectively delivered online, with significant effects in reducing stress, depression, anxiety, and in improving quality of life in both non-clinical and clinical samples [108, 109]. Lyzwinski performed two interesting reviews evaluating the quality and the effects of electronic MBIs for weight-related behaviors [76, 110]. They reviewed all the commercial mindful eating applications available on Apple iTunes until 2018 to evaluate their quality and the adherence of their contents to the fundamental tenets of mindful eating [110]. Most of the applications revealed a poor-quality score according to the Mobile App Rating Scale (MARS), and few were found to include the essential aspects of mindful eating, although they claimed to do so. Moreover, a systematic review assessed the effects of electronic MBIs for weight and weight-related behaviors [110]. Among the 21 included studies, MBSR protocol was used in 19 studies and mindful/intuitive eating interventions in the other two. Most of the electronic interventions were aimed at stress management, and only a few targeted at weight control. The results showed beneficial results for stress reduction. Based on this very limited number of studies, however, it was not possible to evaluate the impact of these online mindfulness trainings on weight management. Further studies that directly target weight-related behaviors and evaluate other types of mindfulness-based approaches are needed to establish the efficacy of online MBIs in this area.

Similarities and Differences Between Hypnosis and Mindfulness

Hypnosis and mindfulness are two distinct and independent strategies, each with its own theoretical and historical facets, which share some common mechanisms at both functional and neurobiological levels [111–113]. Both strategies employ attentional skills [112, 113] and use an attentional focus to develop the ability to be mindful (in mindfulness) or becoming immersed in suggestion-related experiences (in hypnosis) [111]. Based on these and other similarities (please refer to Otani et al. [112] for a comprehensive examination of common mechanisms between these two approaches), some authors have suggested to combine them, in order to use hypnosis to enhance the effects of mindfulness [114–116] and coining the term “mindful hypnotherapy” [117].

Other authors have instead underlined that mindfulness and hypnosis could not be considered as overlapping constructs [111, 112, 118]. As specified by Grover et al. [118], the purpose of hypnosis is to experience changes in consciousness and behavior as a result of suggestive induction. In contrast, the purpose of mindfulness is to notice what is happening in the unfolding experience of sensations, emotions, and thoughts, moment by moment, without the intention to promote an imminent change. Suggestion could be considered as a common mechanism of both strategies, but with different targets: mindfulness promotes a change in the relationship with the experience, while hypnosis fosters a change in the experience itself [118]. Recently, Grover et al. [118] have shown that higher levels of hypnotizability are associated with a reduction of mindfulness facets, in particular the ability to observe, non-react, and non-judge, suggesting that the two strategies have distinct effects and could therefore be offered according to the predominant characteristics of the subjects.

In conclusion, although the two approaches have a long tradition of use, it is only in recent years that clinicians and researchers have started to investigate their common aspects. Therefore, further research is needed to assess whether and how these two strategies can be combined to enhance overall clinical effectiveness.

Conclusions

Fighting the obesity epidemic is challenging due to the ineffectiveness of diet and exercise alone, so finding effective new strategies is mandatory. Due to the relevant psychological involvement in the pathogenesis of obesity, different psychological strategies applied alone or in combination seem to offer a greater chance of success. Hypnosis and mindfulness are ancient strategies that in recent years have gained renewed interest, due to the spread of the offer, the variety of therapeutic applications, and the flexibility of use, which also includes self-administration. Both hypnosis and mindfulness provided additional benefit in the treatment of obesity when applied in a weight management program with or without other psychological interventions; however, owing to the heterogeneity of hypnosis and mindfulness strategies and the short-term duration of most studies, the relative evidence is at present scarce. Additional research is needed to determine whether these strategies are effective in the long term and whether they can be routinely introduced into the clinical practice.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ACT

Acceptance and commitment therapy

- CBT

Cognitive-behavioral therapy

- CFT

Compassion-focused therapy

- DBT

Dialectical behavior therapy

- MARS

Mobile App Rating Scale

- MBIs

Mindfulness-Based Interventions

- MBCT

Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy

- MB-EAT

Mindfulness-Based Eating Awareness Training

- MBSR

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Program

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Torino within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Declarations

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Footnotes

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Psychological Issues

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

- 1.Abarca-Gómez L, Abdeen ZA, Hamid ZA, Abu-Rmeileh NM, Acosta-Cazares B, Acuin C, Adams RJ, Aekplakorn W, Afsana K, Aguilar-Salinas CA, Agyemang C, Ahmadvand A, Ahrens W, Ajlouni K, Akhtaeva N, al-Hazzaa HM, al-Othman AR, al-Raddadi R, al Buhairan F, al Dhukair S, Ali MM, Ali O, Alkerwi A', Alvarez-Pedrerol M, Aly E, Amarapurkar DN, Amouyel P, Amuzu A, Andersen LB, Anderssen SA, Andrade DS, Ängquist LH, Anjana RM, Aounallah-Skhiri H, Araújo J, Ariansen I, Aris T, Arlappa N, Arveiler D, Aryal KK, Aspelund T, Assah FK, Assunção MCF, Aung MS, Avdicová M, Azevedo A, Azizi F, Babu BV, Bahijri S, Baker JL, Balakrishna N, Bamoshmoosh M, Banach M, Bandosz P, Banegas JR, Barbagallo CM, Barceló A, Barkat A, Barros AJD, Barros MVG, Bata I, Batieha AM, Batista RL, Batyrbek A, Baur LA, Beaglehole R, Romdhane HB, Benedics J, Benet M, Bennett JE, Bernabe-Ortiz A, Bernotiene G, Bettiol H, Bhagyalaxmi A, Bharadwaj S, Bhargava SK, Bhatti Z, Bhutta ZA, Bi H, Bi Y, Biehl A, Bikbov M, Bista B, Bjelica DJ, Bjerregaard P, Bjertness E, Bjertness MB, Björkelund C, Blokstra A, Bo S, Bobak M, Boddy LM, Boehm BO, Boeing H, Boggia JG, Boissonnet CP, Bonaccio M, Bongard V, Bovet P, Braeckevelt L, Braeckman L, Bragt MCE, Brajkovich I, Branca F, Breckenkamp J, Breda J, Brenner H, Brewster LM, Brian GR, Brinduse L, Bruno G, Bueno-de-Mesquita HB(), Bugge A, Buoncristiano M, Burazeri G, Burns C, de León AC, Cacciottolo J, Cai H, Cama T, Cameron C, Camolas J, Can G, Cândido APC, Capanzana M, Capuano V, Cardoso VC, Carlsson AC, Carvalho MJ, Casanueva FF, Casas JP, Caserta CA, Chamukuttan S, Chan AW, Chan Q, Chaturvedi HK, Chaturvedi N, Chen CJ, Chen F, Chen H, Chen S, Chen Z, Cheng CY, Chetrit A, Chikova-Iscener E, Chiolero A, Chiou ST, Chirita-Emandi A, Chirlaque MD, Cho B, Cho Y, Christensen K, Christofaro DG, Chudek J, Cifkova R, Cinteza E, Claessens F, Clays E, Concin H, Confortin SC, Cooper C, Cooper R, Coppinger TC, Costanzo S, Cottel D, Cowell C, Craig CL, Crujeiras AB, Cucu A, D'Arrigo G, d'Orsi E, Dallongeville J, Damasceno A, Damsgaard CT, Danaei G, Dankner R, Dantoft TM, Dastgiri S, Dauchet L, Davletov K, de Backer G, de Bacquer D, de Curtis A, de Gaetano G, de Henauw S, de Oliveira PD, de Ridder K, de Smedt D, Deepa M, Deev AD, Dehghan A, Delisle H, Delpeuch F, Deschamps V, Dhana K, di Castelnuovo AF, Dias-da-Costa JS, Diaz A, Dika Z, Djalalinia S, Do HTP, Dobson AJ, Donati MB, Donfrancesco C, Donoso SP, Döring A, Dorobantu M, Dorosty AR, Doua K, Drygas W, Duan JL, Duante C, Duleva V, Dulskiene V, Dzerve V, Dziankowska-Zaborszczyk E, Egbagbe EE, Eggertsen R, Eiben G, Ekelund U, el Ati J, Elliott P, Engle-Stone R, Erasmus RT, Erem C, Eriksen L, Eriksson JG, la Peña JED, Evans A, Faeh D, Fall CH, Sant'Angelo VF, Farzadfar F, Felix-Redondo FJ, Ferguson TS, Fernandes RA, Fernández-Bergés D, Ferrante D, Ferrari M, Ferreccio C, Ferrieres J, Finn JD, Fischer K, Flores EM, Föger B, Foo LH, Forslund AS, Forsner M, Fouad HM, Francis DK, Franco MC, Franco OH, Frontera G, Fuchs FD, Fuchs SC, Fujita Y, Furusawa T, Gaciong Z, Gafencu M, Galeone D, Galvano F, Garcia-de-la-Hera M, Gareta D, Garnett SP, Gaspoz JM, Gasull M, Gates L, Geiger H, Geleijnse JM, Ghasemian A, Giampaoli S, Gianfagna F, Gill TK, Giovannelli J, Giwercman A, Godos J, Gogen S, Goldsmith RA, Goltzman D, Gonçalves H, González-Leon M, González-Rivas JP, Gonzalez-Gross M, Gottrand F, Graça AP, Graff-Iversen S, Grafnetter D, Grajda A, Grammatikopoulou MG, Gregor RD, Grodzicki T, Grøntved A, Grosso G, Gruden G, Grujic V, Gu D, Gualdi-Russo E, Guallar-Castillón P, Guan OP, Gudmundsson EF, Gudnason V, Guerrero R, Guessous I, Guimaraes AL, Gulliford MC, Gunnlaugsdottir J, Gunter M, Guo X, Guo Y, Gupta PC, Gupta R, Gureje O, Gurzkowska B, Gutierrez L, Gutzwiller F, Hadaegh F, Hadjigeorgiou CA, Si-Ramlee K, Halkjær J, Hambleton IR, Hardy R, Kumar RH, Hassapidou M, Hata J, Hayes AJ, He J, Heidinger-Felso R, Heinen M, Hendriks ME, Henriques A, Cadena LH, Herrala S, Herrera VM, Herter-Aeberli I, Heshmat R, Hihtaniemi IT, Ho SY, Ho SC, Hobbs M, Hofman A, Hopman WM, Horimoto ARVR, Hormiga CM, Horta BL, Houti L, Howitt C, Htay TT, Htet AS, Htike MMT, Hu Y, Huerta JM, Petrescu CH, Huisman M, Husseini A, Huu CN, Huybrechts I, Hwalla N, Hyska J, Iacoviello L, Iannone AG, Ibarluzea JM, Ibrahim MM, Ikeda N, Ikram MA, Irazola VE, Islam M, Ismail AS, Ivkovic V, Iwasaki M, Jackson RT, Jacobs JM, Jaddou H, Jafar T, Jamil KM, Jamrozik K, Janszky I, Jarani J, Jasienska G, Jelakovic A, Jelakovic B, Jennings G, Jeong SL, Jiang CQ, Jiménez-Acosta SM, Joffres M, Johansson M, Jonas JB, Jørgensen T, Joshi P, Jovic DP, Józwiak J, Juolevi A, Jurak G, Jureša V, Kaaks R, Kafatos A, Kajantie EO, Kalter-Leibovici O, Kamaruddin NA, Kapantais E, Karki KB, Kasaeian A, Katz J, Kauhanen J, Kaur P, Kavousi M, Kazakbaeva G, Keil U, Boker LK, Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi S, Kelishadi R, Kelleher C, Kemper HCG, Kengne AP, Kerimkulova A, Kersting M, Key T, Khader YS, Khalili D, Khang YH, Khateeb M, Khaw KT, Khouw IMSL, Kiechl-Kohlendorfer U, Kiechl S, Killewo J, Kim J, Kim YY, Klimont J, Klumbiene J, Knoflach M, Koirala B, Kolle E, Kolsteren P, Korrovits P, Kos J, Koskinen S, Kouda K, Kovacs VA, Kowlessur S, Koziel S, Kratzer W, Kriemler S, Kristensen PL, Krokstad S, Kromhout D, Kruger HS, Kubinova R, Kuciene R, Kuh D, Kujala UM, Kulaga Z, Kumar RK, Kunešová M, Kurjata P, Kusuma YS, Kuulasmaa K, Kyobutungi C, la QN, Laamiri FZ, Laatikainen T, Lachat C, Laid Y, Lam TH, Landrove O, Lanska V, Lappas G, Larijani B, Laugsand LE, Lauria L, Laxmaiah A, Bao KLN, le TD, Lebanan MAO, Leclercq C, Lee J, Lee J, Lehtimäki T, León-Muñoz LM, Levitt NS, Li Y, Lilly CL, Lim WY, Lima-Costa MF, Lin HH, Lin X, Lind L, Linneberg A, Lissner L, Litwin M, Liu J, Loit HM, Lopes L, Lorbeer R, Lotufo PA, Lozano JE, Luksiene D, Lundqvist A, Lunet N, Lytsy P, Ma G, Ma J, Machado-Coelho GLL, Machado-Rodrigues AM, Machi S, Maggi S, Magliano DJ, Magriplis E, Mahaletchumy A, Maire B, Majer M, Makdisse M, Malekzadeh R, Malhotra R, Rao KM, Malyutina S, Manios Y, Mann JI, Manzato E, Margozzini P, Markaki A, Markey O, Marques LP, Marques-Vidal P, Marrugat J, Martin-Prevel Y, Martin R, Martorell R, Martos E, Marventano S, Masoodi SR, Mathiesen EB, Matijasevich A, Matsha TE, Mazur A, Mbanya JCN, McFarlane SR, McGarvey ST, McKee M, McLachlan S, McLean RM, McLean SB, McNulty BA, Yusof SM, Mediene-Benchekor S, Medzioniene J, Meirhaeghe A, Meisfjord J, Meisinger C, Menezes AMB, Menon GR, Mensink GBM, Meshram II, Metspalu A, Meyer HE, Mi J, Michaelsen KF, Michels N, Mikkel K, Miller JC, Minderico CS, Miquel JF, Miranda JJ, Mirkopoulou D, Mirrakhimov E, Mišigoj-Durakovic M, Mistretta A, Mocanu V, Modesti PA, Mohamed MK, Mohammad K, Mohammadifard N, Mohan V, Mohanna S, Yusoff MFM, Molbo D, Møllehave LT, Møller NC, Molnár D, Momenan A, Mondo CK, Monterrubio EA, Monyeki KDK, Moon JS, Moreira LB, Morejon A, Moreno LA, Morgan K, Mortensen EL, Moschonis G, Mossakowska M, Mostafa A, Mota J, Mota-Pinto A, Motlagh ME, Motta J, Mu TT, Muc M, Muiesan ML, Müller-Nurasyid M, Murphy N, Mursu J, Murtagh EM, Musil V, Nabipour I, Nagel G, Naidu BM, Nakamura H, Námešná J, Nang EEK, Nangia VB, Nankap M, Narake S, Nardone P, Navarrete-Muñoz EM, Neal WA, Nenko I, Neovius M, Nervi F, Nguyen CT, Nguyen ND, Nguyen QN, Nieto-Martínez RE, Ning G, Ninomiya T, Nishtar S, Noale M, Noboa OA, Norat T, Norie S, Noto D, Nsour MA, O'Reilly D, Obreja G, Oda E, Oehlers G, Oh K, Ohara K, Olafsson Ö, Olinto MTA, Oliveira IO, Oltarzewski M, Omar MA, Onat A, Ong SK, Ono LM, Ordunez P, Ornelas R, Ortiz AP, Osler M, Osmond C, Ostojic SM, Ostovar A, Otero JA, Overvad K, Owusu-Dabo E, Paccaud FM, Padez C, Pahomova E, Pajak A, Palli D, Palloni A, Palmieri L, Pan WH, Panda-Jonas S, Pandey A, Panza F, Papandreou D, Park SW, Parnell WR, Parsaeian M, Pascanu IM, Patel ND, Pecin I, Pednekar MS, Peer N, Peeters PH, Peixoto SV, Peltonen M, Pereira AC, Perez-Farinos N, Pérez CM, Peters A, Petkeviciene J, Petrauskiene A, Peykari N, Pham ST, Pierannunzio D, Pigeot I, Pikhart H, Pilav A, Pilotto L, Pistelli F, Pitakaka F, Piwonska A, Plans-Rubió P, Poh BK, Pohlabeln H, Pop RM, Popovic SR, Porta M, Portegies MLP, Posch G, Poulimeneas D, Pouraram H, Pourshams A, Poustchi H, Pradeepa R, Prashant M, Price JF, Puder JJ, Pudule I, Puiu M, Punab M, Qasrawi RF, Qorbani M, Bao TQ, Radic I, Radisauskas R, Rahman M, Rahman M, Raitakari O, Raj M, Rao SR, Ramachandran A, Ramke J, Ramos E, Ramos R, Rampal L, Rampal S, Rascon-Pacheco RA, Redon J, Reganit PFM, Ribas-Barba L, Ribeiro R, Riboli E, Rigo F, de Wit TFR, Rito A, Ritti-Dias RM, Rivera JA, Robinson SM, Robitaille C, Rodrigues D, Rodríguez-Artalejo F, del Cristo Rodriguez-Perez M, Rodríguez-Villamizar LA, Rojas-Martinez R, Rojroongwasinkul N, Romaguera D, Ronkainen K, Rosengren A, Rouse I, Roy JGR, Rubinstein A, Rühli FJ, Ruiz-Betancourt BS, Russo P, Rutkowski M, Sabanayagam C, Sachdev HS, Saidi O, Salanave B, Martinez ES, Salmerón D, Salomaa V, Salonen JT, Salvetti M, Sánchez-Abanto J, Sandjaja, Sans S, Marina LS, Santos DA, Santos IS, Santos O, dos Santos RN, Santos R, Saramies JL, Sardinha LB, Sarrafzadegan N, Saum KU, Savva S, Savy M, Scazufca M, Rosario AS, Schargrodsky H, Schienkiewitz A, Schipf S, Schmidt CO, Schmidt IM, Schultsz C, Schutte AE, Sein AA, Sen A, Senbanjo IO, Sepanlou SG, Serra-Majem L, Shalnova SA, Sharma SK, Shaw JE, Shibuya K, Shin DW, Shin Y, Shiri R, Siani A, Siantar R, Sibai AM, Silva AM, Silva DAS, Simon M, Simons J, Simons LA, Sjöberg A, Sjöström M, Skovbjerg S, Slowikowska-Hilczer J, Slusarczyk P, Smeeth L, Smith MC, Snijder MB, So HK, Sobngwi E, Söderberg S, Soekatri MYE, Solfrizzi V, Sonestedt E, Song Y, Sørensen TIA, Soric M, Jérome CS, Soumare A, Spinelli A, Spiroski I, Staessen JA, Stamm H, Starc G, Stathopoulou MG, Staub K, Stavreski B, Steene-Johannessen J, Stehle P, Stein AD, Stergiou GS, Stessman J, Stieber J, Stöckl D, Stocks T, Stokwiszewski J, Stratton G, Stronks K, Strufaldi MW, Suárez-Medina R, Sun CA, Sundström J, Sung YT, Sunyer J, Suriyawongpaisal P, Swinburn BA, Sy RG, Szponar L, Tai ES, Tammesoo ML, Tamosiunas A, Tan EJ, Tang X, Tanser F, Tao Y, Tarawneh MR, Tarp J, Tarqui-Mamani CB, Tautu OF, Braunerová RT, Taylor A, Tchibindat F, Theobald H, Theodoridis X, Thijs L, Thuesen BH, Tjonneland A, Tolonen HK, Tolstrup JS, Topbas M, Topór-Madry R, Tormo MJ, Tornaritis MJ, Torrent M, Toselli S, Traissac P, Trichopoulos D, Trichopoulou A, Trinh OTH, Trivedi A, Tshepo L, Tsigga M, Tsugane S, Tulloch-Reid MK, Tullu F, Tuomainen TP, Tuomilehto J, Turley ML, Tynelius P, Tzotzas T, Tzourio C, Ueda P, Ugel EE, Ukoli FAM, Ulmer H, Unal B, Uusitalo HMT, Valdivia G, Vale S, Valvi D, van der Schouw YT, van Herck K, van Minh H, van Rossem L, van Schoor NM, van Valkengoed IGM, Vanderschueren D, Vanuzzo D, Vatten L, Vega T, Veidebaum T, Velasquez-Melendez G, Velika B, Veronesi G, Verschuren WMM, Victora CG, Viegi G, Viet L, Viikari-Juntura E, Vineis P, Vioque J, Virtanen JK, Visvikis-Siest S, Viswanathan B, Vlasoff T, Vollenweider P, Völzke H, Voutilainen S, Vrijheid M, Wade AN, Wagner A, Waldhör T, Walton J, Bebakar WMW, Mohamud WNW, Wanderley RS, Jr, Wang MD, Wang Q, Wang YX, Wang YW, Wannamethee SG, Wareham N, Weber A, Wedderkopp N, Weerasekera D, Whincup PH, Widhalm K, Widyahening IS, Wiecek A, Wijga AH, Wilks RJ, Willeit J, Willeit P, Wilsgaard T, Wojtyniak B, Wong-McClure RA, Wong JYY, Wong JE, Wong TY, Woo J, Woodward M, Wu FC, Wu J, Wu S, Xu H, Xu L, Yamborisut U, Yan W, Yang X, Yardim N, Ye X, Yiallouros PK, Yngve A, Yoshihara A, You QS, Younger-Coleman NO, Yusoff F, Yusoff MFM, Zaccagni L, Zafiropulos V, Zainuddin AA, Zambon S, Zampelas A, Zamrazilová H, Zdrojewski T, Zeng Y, Zhao D, Zhao W, Zheng W, Zheng Y, Zholdin B, Zhou M, Zhu D, Zhussupov B, Zimmermann E, Cisneros JZ, Bentham J, di Cesare M, Bilano V, Bixby H, Zhou B, Stevens GA, Riley LM, Taddei C, Hajifathalian K, Lu Y, Savin S, Cowan MJ, Paciorek CJ, Chirita-Emandi A, Hayes AJ, Katz J, Kelishadi R, Kengne AP, Khang YH, Laxmaiah A, Li Y, Ma J, Miranda JJ, Mostafa A, Neovius M, Padez C, Rampal L, Zhu A, Bennett JE, Danaei G, Bhutta ZA, Ezzati M. Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. The Lancet. 2017;390:2627–2642. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32129-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray GA, Kim KK, Wilding JPH. Obesity: a chronic relapsing progressive disease process. A position statement of the World Obesity Federation. Obes Rev. 2017;18:715–723. doi: 10.1111/obr.12551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karasu SR. Psychotherapy-lite: obesity and the role of the mental health practitioner. Am J Psychother. 2013;67:3–22. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.2013.67.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lang A, Froelicher ES. Management of overweight and obesity in adults: behavioral intervention for long-term weight loss and maintenance. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2006;5:102–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jang HJ, Kim BS, Won CW, Kim SY, Seo MW. The relationship between psychological factors and weight gain. Korean J Fam Med. 2020;41:381–386. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.19.0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elfhag K, Morey LC. Personality traits and eating behavior in the obese: poor self-control in emotional and external eating but personality assets in restrained eating. Eat Behav. 2008;9:285–293. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brennan L, Murphy KD, Garcia X de la P, Ellis ME, Metzendorf M-I, McKenzie JE. Psychological interventions for adults who are overweight or obese. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016. Available at: http://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD012114/full. Accessed 19 Dec 2020.

- 8.Robinson E, Roberts C, Vainik U, Jones A. The psychology of obesity: an umbrella review and evidence-based map of the psychological correlates of heavier body weight. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;1(19):468–480. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2020.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yau YHC, Potenza MN. Stress and eating behaviors. Minerva Endocrinol. 2013;38(3):255–267. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schulte EM, Gearhardt AN. Attributes of the food addiction phenotype within overweight and obesity. Eat Weight Disord. 2020. 10.1007/s40519-020-01055-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Myers CA, Martin CK, Apolzan JW. Food cravings and body weight: a conditioning response. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2018;25:298–302. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ponzo V, Scumaci E, Goitre I, Beccuti G, Benso A, Belcastro S, et al. Predictors of attrition from a weight loss program. A study of adult patients with obesity in a community setting. Eat Weight Disord. 2020. https://doi-org.bibliopass.unito.it/10.1007/s40519-020-00990-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Shaw K, O'Rourke P, Del Mar C, Kenardy J. Psychological interventions for overweight or obesity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;18:CD003818. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003818.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacob A, Moullec G, Lavoie KL, Laurin C, Cowan T, Tisshaw C, Kazazian C, Raddatz C, Bacon SL. Impact of cognitive-behavioral interventions on weight loss and psychological outcomes: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2018;37:417–432. doi: 10.1037/hea0000576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cosme D, Ludwig RM, Berkman ET. Comparing two neurocognitive models of self-control during dietary decisions. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2019;14:957–966. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsz068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forman EM, Butryn ML. A new look at the science of weight control: how acceptance and commitment strategies can address the challenge of self-regulation. Appetite. 2015;84:171–180. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson F, Pratt M, Wardle J. Dietary restraint and self-regulation in eating behavior. Int J Obes (Lond). 2012;36:665–674. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartman D. Confidence intervals and hypnosis in the treatment of obesity. J Heart Centered Ther. 2010;13:37–39. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carels RA, Wott CB, Young KM, Gumble A, Darby LA, Oehlhof MW, Harper J, Koball A. Successful weight loss with self-help: a stepped-care approach. J Behav Med. 2009;32:503–509. doi: 10.1007/s10865-009-9221-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellenberger HF. The discovery of the unconscious: the history and evolution of dynamic psychiatry. Basic Books; 1981.

- 21.Braid J. Neurypnology, or the rationale of nervous sleep, considered in relation with animal magnetism: illustrated by numerous cases of its successful application in the relief and cure of disease. 1843.

- 22.Braid J. Observations on trance: or human hybernation. Churchill; 1850.

- 23.Broussolle E, Gobert F, Danaila T, Thobois S, Walusinski O, Bogousslavsky J. History of physical and «moral» treatment of hysteria. Front Neurol Neurosci. 2014;35:181–197. doi: 10.1159/000360242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kravis NM. James Braid’s psychophysiology: a turning point in the history of dynamic psychiatry. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145:1191–1206. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.10.1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Short D. Conversational Hypnosis: conceptual and technical differences relative to traditional hypnosis. Am J Clin Hypn. 2018;61:125–139. doi: 10.1080/00029157.2018.1441802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heap M. Defining hypnosis: the UK experience. Am J Clin Hypn. 2005;48:117–122. doi: 10.1080/00029157.2005.10401505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elkins G, Barabasz A, Council J. Spiegel D. Advancing research and practice: the revised APA division 30 definition of hypnosis. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2015;63:1–9. doi: 10.1080/00207144.2014.961870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Green JP, Barabasz AF, Barrett D, Montgomery GH. Forging ahead: the 2003 APA Division 30 definition of hypnosis. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2005;53:259–264. doi: 10.1080/00207140590961321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Principi di teoreticità e di prassi della Psicoterapia Ipnotica neo-ericksoniana Terzo manifesto teorico-didattico: update (AA.VV.) Ed Amisi 2001 (Italian)

- 30.Carmody TP, Duncan CL, Solkowitz SN, Huggins J, Simon JA. Hypnosis for smoking relapse prevention: a randomized trial. Am J Clin Hypn. 2017;60:159–171. doi: 10.1080/00029157.2016.1261678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keefer L, Palsson OS, Pandolfino JE. Best practice update: incorporating psychogastroenterology into management of digestive disorders. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:1249–1257. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Booth S. Hypnosis in a specialist palliative care setting—enhancing personalized care for difficult symptoms and situations. Palliat Care. 2020;14:1–11. doi: 10.1177/2632352420953436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rousseaux F, Bicego A, Ledoux D, Massion P, Nyssen A-S, Faymonville M-E, Laureys S, Vanhaudenhuyse A. Hypnosis associated with 3D immersive virtual reality technology in the management of pain: a review of the literature. J Pain Res. 2020;13:1129–1138. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S231737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vanderlinden J, Vandereycken W. The (limited) possibilities of hypnotherapy in the treatment of obesity. Am J Clin Hypn. 1994;36:248–257. doi: 10.1080/00029157.1994.10403084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berthoud H-R, Münzberg H, Morrison CD. Blaming the brain for obesity: integration of hedonic and homeostatic mechanisms. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1728–1738. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.12.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Winkelstein LB. Hypnosis, diet, and weight reduction. N Y State J Med. 1959;59:1751–1756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stanton HE. Weight loss through hypnosis. Am J Clin Hypn. 1975;18:94–97. doi: 10.1080/00029157.1975.10403782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kirsch I, Montgomery G, Sapirstein G. Hypnosis as an adjunct to cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy: a meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63:214–220. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.63.2.214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allison DB, Faith MS. Hypnosis as an adjunct to cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for obesity: a meta-analytic reappraisal. 1996. In: Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE): quality-assessed reviews. York (UK): Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (UK); 1995. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK66645/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Kirsch I. Hypnotic enhancement of cognitive-behavioral weight loss treatments—another meta-reanalysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64:517–519. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.64.3.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sapp M, Obiakor F, Scholze S, Gregas AJ. Confidence intervals and hypnosis in the treatment of obesity. Aust J Clin Hypnother Hypn. 2007;28:25–33. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cochrane G, Friesen J. Hypnotherapy in weight loss treatment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1986;54:489–492. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.54.4.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stradling J, Roberts D, Wilson A, Lovelock F. Controlled trial of hypnotherapy for weight loss in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea. Int J Obes. 1998;22:278–281. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gelo OCG, Zips A, Ponocny-Seliger E, Neumann K, Balugani R, Gold C. Hypnobehavioral and hypnoenergetic therapy in the treatment of obese women: a pragmatic randomized clinical trial. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2014;62:260–291. doi: 10.1080/00207144.2014.901055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Häuser W, Hagl M, Schmierer A, Hansen E. The efficacy, safety and applications of medical hypnosis. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2016;113:289–296. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2016.0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Milling LS, Gover MC, Moriarty CL. The effectiveness of hypnosis as an intervention for obesity: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Conscious. 2018;5:29–45. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bo S, Rahimi F, Properzi B, Regaldo G, Goitre I, Ponzo V, Boschetti S, Fadda M, Ciccone G, de Francesco A, Abbate Daga G, Mengozzi G, Belcastro S, Broglio F. Effects of self-conditioning techniques in promoting weight loss in patients with severe obesity: a randomized controlled trial protocol. Int J Clin Trials. 2017;4:20–27. doi: 10.18203/2349-3259.ijct20170304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bo S, Rahimi F, Goitre I, Properzi B, Ponzo V, Regaldo G, Boschetti S, Fadda M, Ciccone G, Abbate Daga G, Mengozzi G, Evangelista A, de Francesco A, Belcastro S, Broglio F. Effects of self-conditioning techniques (self-hypnosis) in promoting weight loss in patients with severe obesity: a randomized controlled trial. Obesity. 2018;26:1422–1429. doi: 10.1002/oby.22262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cioffi I, Gambino R, Rosato R, Properzi B, Regaldo G, Ponzo V, et al. Acute assessment of subjective appetite and implicated hormones after a hypnosis-induced hallucinated meal: a randomized cross-over pilot trial. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2020;21:411–420. doi: 10.1007/s11154-020-09559-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bolocofsky DN, Spinler D, Coulthard-Morris L. Effectiveness of hypnosis as an adjunct to behavioral weight management. J Clin Psychol. 1985;41:35–41. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198501)41:1<35::AID-JCLP2270410107>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barabasz M, Spiegel D. Hypnotizability and weight loss in obese subjects. Int J Eat Disord. 1989;8:335–341. doi: 10.1002/1098-108X(198905)8:3<335::AID-EAT2260080309>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bornstein PH, Devine DA. Covert modeling-hypnosis in the treatment of obesity. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice. 1980;17:272–276. doi: 10.1037/h0085922. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goldstein Y. The effect of demonstrating to a subject that she is in a hypnotic trance as a variable in hypnotic interventions with obese women. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 1981;29(1):15–23. doi: 10.1080/00207148108409140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Byom TK, Sapp M. Comparison of effect sizes of three group treatments for weight loss. Sleep Hypn. 2013;15:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wadden TA, Flaxman J. Hypnosis and weight loss: a preliminary study. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 1981;29:162–173. doi: 10.1080/00207148108409156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Deyoub PL, Wilkie R. Suggestion with and without hypnotic induction in a weight reduction program. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 1980;28:333–340. doi: 10.1080/00207148008409862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=hypnosis&term=obesity&cntry=&state=&city=&dist=. Accessed 27 Dec 2020.

- 58.Scientific Research on Hypnosis & Type 2 Diabetics—NGH.net. Available at: https://www.ngh.net/scientific-research-on-hypnosis-type-2-diabetics/. Accessed 28 Mar 2021.

- 59.Sucala M, Schnur JB, Glazier K, Miller SJ, Green JP, Montgomery GH. Hypnosis there’s an app for that: a systematic review of hypnosis apps. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2013;61:463–474. doi: 10.1080/00207144.2013.810482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shapiro S, Weisbaum E. History of mindfulness and psychology. Oxford research encyclopedia of psychology, 2020. Available at: https://oxfordre.com/psychology/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.001.0001/acrefore-9780190236557-e-678. Accessed 18 Dec 2020.

- 61.Kabat-Zinn J. An outpatient program in behavioral medicine for chronic pain patients based on the practice of mindfulness meditation: theoretical considerations and preliminary results. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1982;4:33–47. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(82)90026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clin Psychol. 2003;10:144–156. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bishop SR, Lau M, Shapiro S, Carlson L, Anderson ND, Carmody J, et al. Mindfulness: a proposed operational definition. Clin Psychol. 2004;11:230–241. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kabat-Zinn J. University of Massachusetts Medical Center/Worcester, Stress Reduction Clinic. Full catastrophe living: using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York: Delacorte Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: a new approach to preventing relapse. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kristeller JL, Hallett CB. An exploratory study of a meditation-based intervention for binge eating disorder. J Health Psychol. 1999;4:357–363. doi: 10.1177/135910539900400305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kristeller J, Wolever RQ, Sheets V. Mindfulness-based eating awareness training (MB-EAT) for binge eating: a randomized clinical trial. Mindfulness. 2014;5:282–297. doi: 10.1007/s12671-012-0179-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Keng S-L, Smoski MJ, Robins CJ. Effects of mindfulness on psychological health: a review of empirical studies. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31:1041–1056. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Grossman P, Niemann L, Schmidt S, Walach H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits. A meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57:35–43. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00573-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Witt AA, Oh D. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: a meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78:169–183. doi: 10.1037/a0018555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Leyland A, Rowse G, Emerson L-M. Experimental effects of mindfulness inductions on self-regulation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Emotion. 2019;19:108–122. doi: 10.1037/emo0000425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.O’Reilly GA, Cook L, Spruijt-Metz D, Black DS. Mindfulness-based interventions for obesity-related eating behaviours: a literature review. Obes Rev. 2014;15:453–461. doi: 10.1111/obr.12156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kristeller JL, Wolever RQ. Mindfulness-based eating awareness training for treating binge eating disorder: the conceptual foundation. Eat Disord. 2011;19:49–61. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2011.533605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Leehr EJ, Krohmer K, Schag K, Dresler T, Zipfel S, Giel KE. Emotion regulation model in binge eating disorder and obesity—a systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;49:125–134. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]