Abstract

The recent advent of gene-targeting techniques in malaria (Plasmodium) parasites provides the means for introducing subtle mutations into their genome. Here, we used the TRAP gene of Plasmodium berghei as a target to test whether an ends-in strategy, i.e., targeting plasmids of the insertion type, may be suitable for subtle mutagenesis. We analyzed the recombinant loci generated by insertion of linear plasmids containing either base-pair substitutions, insertions, or deletions in their targeting sequence. We show that plasmid integration occurs via a double-strand gap repair mechanism. Although sequence heterologies located close (less than 450 bp) to the initial double-strand break (DSB) were often lost during plasmid integration, mutations located 600 bp and farther from the DSB were frequently maintained in the recombinant loci. The short lengths of gene conversion tracts associated with plasmid integration into TRAP suggests that an ends-in strategy may be widely applicable to modify plasmodial genes and perform structure-function analyses of their important products.

Systems for stable transformation of malaria parasites and the targeted integration of exogenous DNA into their genome have recently been developed (22, 23), now allowing a genetic approach to study Plasmodium protein function in vivo. Integration of targeting constructs into the genome of Plasmodium spp. occurs only by homologous recombination. In addition, the stage of the parasite that can be transformed (the forms that replicate in host erythrocytes) is haploid, enabling study of the function of proteins encoded by single-copy genes after single targeting events.

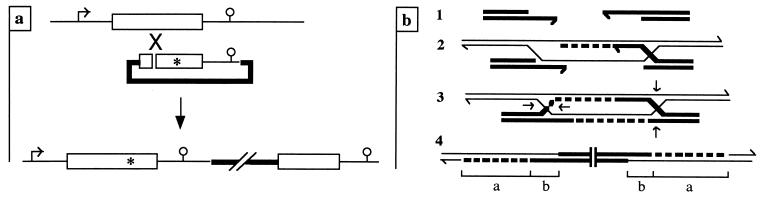

So far, only null mutations have been created in Plasmodium spp.: in the human parasite P. falciparum (4) and the rodent parasite P. berghei (9, 16). Although null mutations are valuable for revealing the basal function of the target protein, a better understanding of protein function is obtained by altering critical residues or discrete regions of the protein. Several strategies may be used for introducing subtle gene modifications by gene targeting. A modified version of the gene can be expressed via autonomously replicating episomes in a parasite line bearing a null mutation in the gene, a strategy that requires two selectable markers (only one is available in the P. berghei transformation system). The modified gene can also be created by a single recombination event at the wild-type (wt) locus, promoted by a targeting plasmid of the insertion or the replacement type. Figure 1a illustrates the use of an insertion plasmid for gene modification. The targeting sequence of the plasmid lacks the 5′ end of the gene, ends after its 3′ regulatory elements, and contains the mutation to be expressed. When the plasmid is linearized by introduction of a double-strand break (DSB) in the targeting sequence upstream from the mutation, the final locus contains a full-length, expressed copy of the modified gene, followed by a truncated, nonexpressed copy of the gene.

FIG. 1.

(a) Introducing a subtle gene modification with an insertion plasmid. The target gene (symbolized by an open box) is flanked by untranslated sequences (thin lines) bearing the promoter (arrow) and 3′ signals (circle) necessary for normal gene expression. The targeting construct contains a bacterial plasmid and a resistance cassette (thick lines) and a targeting sequence that starts after the start codon of the gene, stops after its 3′ regulatory sequences, and bears a mutation (asterisk). The plasmid is linearized (gap) within the region of homology upstream from the mutation. Plasmid integration at the target locus duplicates the region of homology and places the mutation in the first, full-length, and expressed copy of the gene. (b) DSB repair model for plasmid integration (ends-in recombination). Plasmid DNA strands are shown in thick lines, chromosomal strands are shown in thin lines, and DNA synthesis is indicated by dashed lines. (Line 1) The initial DSB made within the plasmid sequence is enlarged by exonuclease activity to a double-strand gap, and the plasmid ends are processed to 3′-overhanging, single-stranded tails. (Line 2) One 3′ tail invades the homologous duplex and primes repair synthesis while producing a D loop that will anneal to the other 3′ tail, thus allowing the second round of repair synthesis. (Line 3) After ligation, the recombination intermediate contains two Holliday junctions embracing the region of gap repair that may be resolved independently as a crossover (by cutting the outer strands) or as a noncrossover (by cutting inner strands). Plasmid integration, which requires one crossover and one noncrossover, occurs in 50% of the cases. (Line 4) The integrated structure contains regions of repaired DNA (a) and heteroduplex DNA (b), which may be asymmetric (on only one chromatid), i.e., promoted by the 3′-single-stranded tails, and potentially symmetric (covering the same region of two chromatids) when the Holliday junction branch migrates.

Homologous recombination with insertion plasmids cut in their region of homology (ends-in recombination) has been widely studied in yeast and mammalian cells. Plasmid integration is thought to occur by a DSB-gap repair mechanism (see Fig. 1b). This model in yeast cells evolved from the demonstration that insertion plasmids cut at two restriction sites, so as to liberate an internal segment of the targeting sequence, still integrated at high frequency at the target locus through a process that always repaired the missing segment (11, 13, 14). The two salient features of this model of recombination (19) are the enlargement of the initial DSB to a double-strand gap, which is filled by two rounds of single-strand repair synthesis, and the formation of two regions of heteroduplex DNA (hDNA) flanking the gap, whose potential mismatches may be converted to either of the sequences. In both yeast and mammalian cells, gene conversion tracts associated with plasmid integration may be several kilobases in length (1, 5, 6, 8, 15, 17, 18, 20).

Here, we investigated the recombination of linearized insertion plasmids in P. berghei by analyzing recombination reactions promoted by insertion plasmids that contained either base-pair substitutions, insertions, or deletions in their targeting sequence.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of control integration plasmids.

Plasmid pInco consists of (i) the bacterial plasmid pBSKS (∼3 kb); (ii) a DHFR-TS mutant, pyrimethamine-resistance gene from P. berghei expressed from its own 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTR) (∼4.5 kb); and (iii) the distal part of the TRAP gene, lacking the first 22 codons, and 1.4 kb portion of downstream UTR (∼3 kb). This TRAP targeting sequence was cloned from genomic DNA of TRAP knockout INT parasites (16) after digestion with HpaI and EcoRV, ligation, and rescue of the resulting plasmid pTRAP-3′UTR in Escherichia coli. Plasmid pTRAP-3′UTR was then digested with BamHI and XmnI, and the TRAP-containing fragment was inserted into plasmid pMD205ΔKpnI-HincII digested with NotI, filled in, and further digested with BamHI. The resulting plasmid, pInco, thus possesses a targeting sequence that originates from the same P. berghei strain (NK65) as that used as a recipient in transformation experiments. Plasmid pInCS is a derivative of pInco that was obtained by exchanging the TRAP targeting sequence by the distal part of the CS gene lacking the first 11 codons and followed by ∼0.4 kb of downstream UTR (∼1.2 kb).

Construction of mutations.

Base-pair substitutions and deletions were created by fusing two contiguous (proximal and distal) DNA fragments amplified by PCR from genomic TRAP (Fig. 2a). The antisense primer used to amplify the proximal fragment and the sense primer used to amplify the distal fragment, which introduce the mutation and a restriction site were, respectively, as follows: R2W, 5′-CGCGAAGCTTCTTCCCATTTTCCACAAAGAGC-3′ and 5′-CGCGAAGCTTCTGAATGTTCTACTACATGTGACAATG-3′ (HindIII site is underlined); R2+, 5′-CGGTGCTGCAGCTGCAATTGCTGTTCCATTGTCACATGTAGTAG-3′ and 5′-CGGCTGCAGCAGTATTACATCCTAATTGTGCTGGAG-3′ (PstI site is underlined); ΔS, 5′-CGCTTAATTAACAACAATACCCTTTTCATCATCTGC-3′ and 5′-GCGTTAATTAATTTTAATAAACATATATATCTAGAGAATT-3′ (PacI site is underlined); and ΔL, 5′-CGCTTAATTAACGCTACTTCCTGCTATAAAATTATAACC-3′ and 5′-GCGTTAATTAATTTTAATAAACATATATATCTAGAGAATT-3′ (PacI site is underlined). All PCR products were cloned into PCRscript vector by using the PCR-Script cloning kit (Stratagene), and the contiguous fragments were ligated into the pCRScript via the restriction site tagging the mutation. The nucleotide sequence of the fragments used to replace their counterpart in plasmid pInco was determined and verified to differ from that of the wt only by the desired mutation.

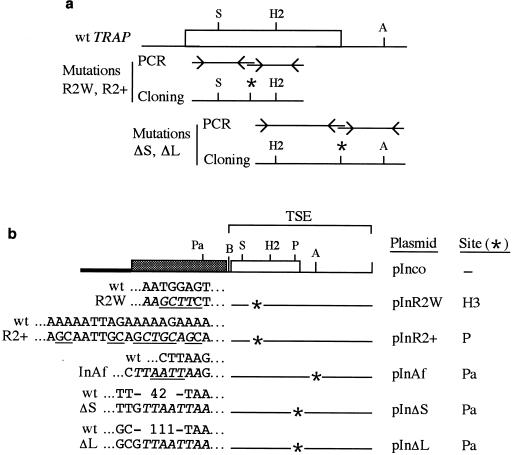

FIG. 2.

(a) Construction of mutations. The R2W and R2+ base-pair substitutions and the ΔS and ΔL base-pair deletions were constructed by fusing two contiguous PCR-amplified fragments. The antisense primer used to amplify the proximal fragment and the sense primer used to amplify the distal fragment introduced the mutation and a restriction site (asterisk). A fragment encompassing the mutation in the reassembled PCR product (SpeI-HincII or HincII-AflII for the base-pair substitutions or the base-pair deletions, respectively) was then used to replace its counterpart in plasmid pInco. (b) Schematic representation of plasmid pInco and its derivatives. Symbols: thick line, bacterial plasmid; hatched box, resistance cassette; open box, TRAP coding sequence; thin line, TRAP 3′ untranslated sequence. The mutations as well as the corresponding wt sequence are shown at the left. Base-pair substitutions are underlined, and restriction sites are italicized. In the wt, the numbers indicate the number of intervening base pairs. The name of the plasmid and the restriction site tagging the mutation are indicated at the right. Abbreviations: A, AflII; B, BamHI; H2, HincII; H3, HindIII; Pa, PacI; P, PstI; S, SpeI.

Construction of plasmid pInco derivatives.

To generate plasmids pInR2W and pInR2+, the SpeI-HincII internal fragment of the reassembled locus encompassing the respective mutation was used to replace its counterpart in plasmid pInco. To generate plasmids pInΔS and pInΔL, the HincII-AflII internal fragment of the reassembled locus encompassing the respective deletion was used to replace its counterpart in plasmid pInco. The 4-bp insertion in the targeting sequence (TSE) of pInco was obtained by filling in the ends of pInco linearized with AflII, creating a PacI site and resulting in plasmid pInAf. The sequences of the mutations and of their wild-type counterparts are shown in Fig. 2b.

Transformation experiments.

Approximately 10 to 30 μg of each plasmid linearized by overnight digestion with the appropriate enzyme (New England Biolabs) was electroporated into ∼109 P. berghei merozoites, as previously described (10), and injected into young, susceptible Sprague-Dawley rats. Recipient rats with a parasitemia level of >0.5% at 24 h after injection of the electroporated parasites were treated for 4 consecutive days with pyrimethamine (20 mg/kg of body weight), and the resistant parasites emerged at day 8 or 9 postelectroporation in all experiments. Rats were then treated for 2 additional days, and parasite genomic DNA was collected when the parasitemia level was >1%.

Southern hybridization and PCR analysis of resistant parasite populations.

Southern blotting was performed with the entire TRAP coding sequence as a probe. The probe was labelled with DIG-ddUTP by random priming, and the chemiluminescence was detected by using CSPD (Boehringer Mannheim). Genomic DNA of parasite populations was prepared as previously described (10). Specific amplification of the first duplicate of a recombinant locus obtained after integration of plasmid pInco or one of its derivatives was performed with primers O1 (5′-GTTGTGCTTTTATTATGCATAAGTGTG-3′, a sense primer that hybridizes to a sequence located at the 5′ end of the TRAP coding sequence but absent from pInco) and primer T7 (5′-GTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGC-3′, an antisense primer that hybridizes to the bacterial plasmid pBSKS). Amplification of the duplicates located downstream from a cassette was performed with primers OH4 (5′-GCGGAATTCTAATGTTCGTTTTTCTTATTTATATAT-3′, a sense primer that hybridizes to a sequence located immediately downstream from the stop codon of the DHFR-TS resistance gene) and primer P18 (5′-GCCGAGCTCAACATTCCATCGTTTTTTTTTATCACAC-3′, an antisense primer that hybridizes to a sequence located at the 3′ end of the TSE of the plasmids).

RESULTS

Rationale of the study.

We performed transformation experiments with a series of targeting insertion plasmids (Fig. 2) into P. berghei parasites. The rodent malarial transformation system (P. berghei parasites infecting rodents) allows rapid in vivo selection of recombinant parasites in rat erythrocytes after transformation with constructs containing a mutant DHFR-TS gene that confers resistance to pyrimethamine (22). The target locus was the single-copy TRAP gene, which is not expressed during the erythrocytic stages of the parasite (16), the stages that can be transformed. TRAP null mutants created in P. berghei by using either insertion or replacement targeting plasmids have been shown to replicate with the same efficiency as that of the wt in rat erythrocytes (16). Since modification of the TRAP locus does not affect parasite replication, the proportion of TRAP integrants in the resistant parasite population should indeed reflect the frequency of initial integration events.

With each plasmid, a number of independent transformation experiments were performed. Each resistant parasite population was analyzed by Southern blot hybridization, using the TRAP coding sequence as a probe, and PCR, with various pairs of oligonucleotides that specifically amplify either the first or the second TRAP duplicates generated by plasmid integration. The results are presented in Table 1 as the proportion of resistant parasites that had the plasmid integrated into TRAP and, among these integrants, the proportion that had conserved the mutation present in the TSE of the transforming plasmid.

TABLE 1.

TRAP recombinant parasites generated in this study

| Plasmid electroporated

|

Transformation exptc

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmid | Mutationa (bp) | DSB siteb | DSB-mutation distance (bp) | Parasite populationd | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| pInco | S | Inco/S | 50 | 50 | 50 | 90 | 90 | ||

| N | Inco/N | 0 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | |||

| pInR2+ | 11 (sub.) | S | 450 | R2+ | 50 (−) | 100 (−) | 100m (−) | 100m (−) | |

| pInR2W | 5 (sub.) | S | 420 | R2W/S | 10 (−) | 50 (−) | 100 (−) | 100m (−) | |

| P | 980 | R2W/P | 100 (+) | 50 (++) | 90 (++) | 100 (++) | |||

| pInAf | 4 (ins.) | P | ∼600 | Af/P | 50 (+) | 50m (+) | 90 (+) | 90 (++) | |

| H2 | ∼1,200 | Af/H | 90 (++) | 100 (++) | |||||

| S | ∼2,000 | Af/S | 100 (+) | 50 (++) | |||||

| pInΔS | 36 (del.) | S | ∼1,450 | ΔS | 90 (−) | 50 (+) | 50 (++) | ||

| pInΔL | 105 (del.) | S | ∼1,400 | ΔL | 90 (−) | 100m (−) | 50 (++) | 100m (++) | |

Mutations are either base-pair substitutions (sub.), insertions (ins.), or deletions (del.).

Abbreviations: H2, HincII; N, NdeI; P, PstI; S, SpeI.

A number of independent transformation experiments (one to five) were performed with each linear plasmid.

The parasite populations are named according to the plasmid transformed and the site used to linearize the plasmid (when more than one was used). In each case, the proportion of parasites having the plasmid integrated into TRAP and, among them, the proportion of integrants having the mutation in the appropriate TRAP duplicate (indicated in parentheses), are shown. The proportion of integrants was estimated by Southern hybridization by using BamHI digestion and was classified as 0, 10, 50, 90, or 100 according to the intensity ratio of the bands diagnostic for an Inco versus a wt TRAP locus (“m” indicates that there was more than one copy of the plasmid integrated into TRAP in some or all of the parasites). The proportion of integrants with the mutation in the appropriate copy was estimated by PCR amplification and restriction analysis of the copy and was classified as follows: −, mutation not detected; + or ++, mutation was found in fewer or more than 50% of the PCR products, respectively.

In all experiments, resistant parasites either had the plasmid integrated into TRAP or appeared as wt-like, with both a TRAP and a DHFR-TS probe. These wt-like parasites thus originated from spontaneous mutations in the endogenous DHFR-TS or from gene conversion or gene replacement events between the plasmid and the chromosomal DHFR-TS alleles. Nonhomologous recombination of the transforming constructs or their autonomous replication as a nonintegrated element were not detected in any experiment.

Integration of control insertion plasmids.

We first investigated the homology requirements for the integration of the insertion plasmid pInco (insertion control) as its cognate locus. As depicted in Fig. 2b, the TSE of plasmid pInco consists of the distal part of the TRAP gene and 1.4 kb of downstream sequence (∼3 kb), thus conforming to the pattern schematized in Fig. 1a. Transformation experiments were performed with plasmid pInco linearized at the SpeI site located 250 bp from the 5′ end of the TSE. Figure 3a shows the structure of the recombinant locus generated by integration of plasmid pInco into chromosomal TRAP, called the Inco locus. Parasites with an Inco locus, named Inco, are readily recognized by Southern blot hybridization of parasite DNA by using a TRAP probe and the restriction digestions shown in Fig. 3a. Five independent populations of resistant parasites were analyzed by Southern hybridization, which all contained at least 50% of the expected Inco parasites (Table 1). One representative population, Inco/S4, is analyzed in Fig. 3b. This population contained a majority of Inco parasites, which were detected by the 16- and 4-kb fragments generated upon BamHI digestion and the 14-kb fragment generated upon MscI-EcoRI digestion. Population Inco/S4 also contained a minority of parasites with a wt TRAP, as shown by the presence of the 9.5-kb fragment upon BamHI digestion and of the 3.5-kb fragment upon MscI-EcoRI digestion.

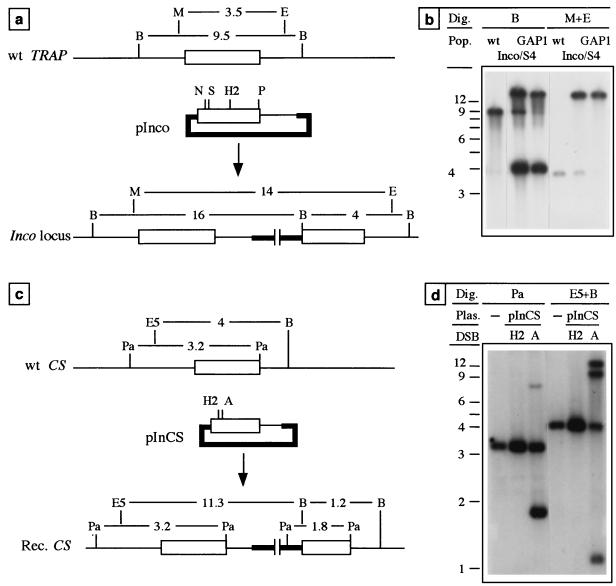

FIG. 3.

Integration of control insertion plasmids. (a) Schematic representations of the wt TRAP locus, plasmid pInco (10.5 kb), and the Inco recombinant locus generated by homologous integration of pInco at the TRAP locus (not drawn to scale); see below for symbols and abbreviations. The predicted size (in kilobases) of restriction fragments generated upon digestion with BamHI, which cuts once in the plasmid backbone, or MscI-EcoRI, which do not cut in the construct, in a wt TRAP or an Inco locus are shown. (b) Southern hybridization with a TRAP probe of wt P. berghei (lanes 1 and 4), population Inco/S4, obtained after transformation with plasmid pInco linearized at the SpeI site (lanes 2 and 5), and population GAP1 obtained after transformation with plasmid pInco cut at the HincII and PstI sites (lanes 3 and 6). (c) Schematic representations of the wt CS locus, plasmid pInCS (8.5 kb), and the recombinant locus generated by homologous integration of pInCS at the CS locus (not drawn to scale). The predicted size of restriction fragments generated upon digestion with PacI, which cuts in the cassette and in the TSE, or with both BamHI and EcoRV, which cuts or does not cut in the construct, respectively, are shown. (d) Southern hybridization with a CS probe of the wt (lanes 1 and 4), and two populations obtained after transformation with pInCS cut in the TSE either at the HincII site (lanes 2 and 5) or at the AflII site (lanes 3 and 6). Symbols: open box, TRAP or CS coding sequence; thin line, TRAP or CS UTRs; thick lines, bacterial plasmid and resistance cassette (not drawn to scale). Abbreviations: A, AflII; B, BamHI; E, EcoRI; E5, EcoRV; H2, HincII; M, MscI; N, NdeI; Pa, PacI; P, PstI; S, SpeI; X, XbaI.

A second set of transformation experiments was performed with plasmid pInco linearized at the NdeI site located ∼210 bp from the 5′ end of the TSE (Fig. 3a). Four of five transformation experiments generated parasite populations containing the expected Inco recombinants. However, the proportion of these recombinants was lower (8%) than in experiments with pInco linearized at the SpeI site (66%) (means of values presented in Table 1). This suggested that the decrease to 200 bp in the distance between the DSB and one end of the TSE affected the integration process, presumably because the short arm of homology was degraded past the border with the vector DNA.

We then examined whether a short distance between the DSB and one edge of the TSE would still allow crossing-over at a different genomic location, such as the single-copy CS locus. For this, we constructed insertion plasmid pInCS, a derivative of plasmid pInco whose TSE consisted of ∼1.2 kb of CS sequence (Fig. 3c). Four transformation experiments were performed with plasmid pInCS linearized at the unique HincII site located ∼140 bp from the 5′ end of the TSE. All such experiments failed to produce detectable amounts of the expected integrants. Experiments were then performed with pInCS linearized at a unique AflII site introduced by PCR at 250 bp from the 5′ end of the TSE. Three of four such experiments produced resistant populations with at least 50% of the parasites with one or more copies of the plasmid integrated into CS. Figure 3d shows the Southern blot of a representative population obtained after transformation with pInCS linearized with either HincII or AflII. In the latter case, plasmid integration into CS is revealed by the presence of a 1.9-kb fragment upon PacI digestion and of 1.2- and 12.2-kb fragments upon EcoRV-BamHI digestion, whereas multiple integration events are demonstrated by the diagnostic EcoRV-BamHI-generated fragment of 8.5 kb, the size of the plasmid. These results show that only ∼250 bp for the short arm of homology in linear plasmids pInco and pInCS are sufficient for efficient recombination at their target locus.

We then used plasmid pInco to test the double-strand gap repair model. We digested plasmid pInco with restriction enzymes HincII and PstI, creating a 560-bp gap in the TSE (Fig. 3a). The resulting DNA fragments were separated by two rounds of agarose gel electrophoresis, and the linear-gapped plasmid was purified from the gel and transformed into P. berghei. Southern blot analysis of one representative population, GAP1, is shown in Fig. 3b. All parasites in this population displayed an integration pattern of gapped pInco that was indistinguishable from that produced by integration of full-length pInco linearized at the SpeI site (population Inco/S4). Fragments corresponding to the presence of the original gap in the integrated structure were not detected, indicating that the gap was repaired during integration by using chromosomal information as a template. In addition, the high proportion of Inco versus wt-like parasites in population GAP1 suggested that DSBs and gaps were similarly efficient at initiating the integration process.

Fate of base-pair substitutions.

We then analyzed the fate of base-pair substitutions in the TSE of plasmid pInco during homologous integration. As shown in Fig. 2a, these mutations, named R2W and R2+ and consisting of 5- and 11-bp substitutions, respectively (Fig. 2b), were created by amplification-cloning. The plasmid pInco derivatives pInR2W and pInR2+ which contained the respective substitutions were cut at the SpeI site, located ∼450 bp upstream from the mutations, and independently transformed into P. berghei. Most of the resistant populations obtained (Table 1, populations R2+ and R2W/S) contained a high proportion of parasites which had the plasmid integrated into TRAP, suggesting that heterologies in the TSE did not dramatically affect the integration efficiency. The presence of the respective mutations in the recombinant loci was assessed by Southern blot hybridization of parasite DNA digested with both HincII and the restriction enzyme corresponding to the mutation tagging site. The fragments diagnostic for the presence of the mutation in the TRAP integrants were not detected in any of the populations obtained (Table 1). This indicated that both mutations were frequently corrected during recombination initiated by a DSB located ∼450 bp upstream.

We then tested whether the mutations could be conserved if located farther from the DSB. We thus transformed plasmid pInR2W linearized with PstI, which cuts ∼1 kb downstream from the mutation. Four such experiments were performed, generating populations R2W/P (Table 1) which all contained the expected integrants. Because of the downstream position of the DSB relative to the mutation, conservative integration should place the mutation in the second duplicate, as depicted in Fig. 4a. In this case, the HindIII-tagged mutation is detected by using a HincII-HindIII digestion by the disruption of a 1.6-kb fragment into two fragments of 1.1 and 0.5 kb. Southern hybridization showed that integrants bearing the mutation in the second duplicate were present in all four populations (Table 1). The Southern blot of one population, R2W/P4, is shown in Fig. 4b. As shown by the total disappearance of the HincII-HindIII-generated 1.6-kb fragment, R2W/P4 appeared as a pure population of integrants which all contained the mutation in the second duplicate. Therefore, the R2W mutation, which was frequently corrected when recombination was promoted by a DSB 420 bp apart (with the SpeI site), was frequently maintained when the DSB was 980 bp apart (with the PstI site).

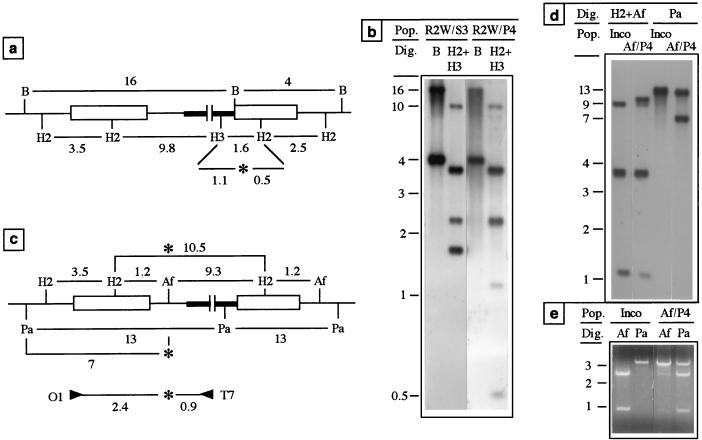

FIG. 4.

Fate of base-pair substitutions and insertions during recombination. (a) Recombinant locus generated by homologous integration of plasmid pInR2W at the TRAP locus. The predicted size (in kilobases) of restriction fragments generated upon digestion with BamHI, which cuts once in the bacterial plasmid, or with both HincII, which cuts in the TSE, and HindIII, which cuts in the cassette, are shown. The presence of the HindIII-tagged mutation (asterisk) in the second duplicate is revealed by the cleavage of the 1.6-kb fragment into two smaller fragments. (b) Southern hybridization by using a TRAP probe of populations R2W/S3 and R2W/P4 obtained after transformation with plasmid pInR2W linearized at the SpeI or the PstI site, respectively. The BamHI digestion indicates that both populations contained a majority of integrants, and the HincII-HindIII digestion shows the presence of the additional HindIII site in the second duplicate of virtually all parasites in population R2W/P4 but not population R2W/S3. (c) Recombinant locus generated by homologous integration of plasmid pInAf at the TRAP locus. The predicted size of restriction fragments generated upon digestion with HincII-AflII or PacI are shown. When HincII-AflII was used, the absence of the wt AflII site (asterisk) in the first duplicate is indicated by an additional 10.5-kb fragment, whereas when PacI was used the presence of the PacI-tagged mutation in the first duplicate is indicated by an additional 7-kb fragment. The PCR fragment amplified by primers O1 and T7 is shown below. (d) Southern hybridization with a TRAP probe of an Inco clonal population (lanes 1 and 3) and population Af/P4 (lanes 2 and 4), obtained after transformation of plasmid pInAf linearized at the PstI site. (e) Restriction analysis of the first TRAP duplicates amplified by PCR with primers O1 and T7 (see panel c). The majority of the PCR products amplified from population Af/P4 lack the wt AflII site and contain the PacI-tagged mutation. Symbols and abbreviations are as in Fig. 3.

Fate of a sequence insertion.

We then tested the fate of a sequence insertion in the TSE of plasmid pInco during plasmid integration. Four base pairs were inserted in pInco by filling in the overhanging ends of the unique AflII site, a process that destroys this site and creates a PacI site (Fig. 2b). The resulting plasmid, pInAf, was cut with one of the restriction enzymes, PstI, HincII, or SpeI, located at increasing distances from the mutation and was used in independent transformation experiments. The correct integration events were detected in all populations, and integrants with the mutation in the first TRAP copy were obtained with each linear form of the plasmid (Table 1). Importantly, the 4-bp insertion was reproducibly maintained in the recombinant locus even when the initiating DSB was located only 600 bp away (populations Af/P-1 to Af/P5). Conversely, the mutation was also corrected in a proportion of integrants in population Af/S1, indicating that the mutation may also be corrected during an integration process initiated ∼2 kb away.

One population obtained after transformation with the plasmid linearized 600 bp from the 4-bp insertion, Af/P4, is analyzed in Fig. 4c to e. Most parasites in this population had one copy of the plasmid integrated into TRAP, as depicted in Fig. 4c. The absence of the wt AflII site in the first duplicate is detected by using HincII-AflII digestion by the fusion of a 1.2-kb fragment and a 9.3-kb fragment into a 10.5-kb fragment, whereas the presence of the PacI-tagged insertion is detected by using PacI digestion by the creation of a 7-kb fragment. These diagnostic new fragments were detected by Southern hybridization in population Af/P4 (Fig. 4d), indicating that some integrants in this population had the mutation in the first duplicate. To confirm this, the first TRAP copy in recombinant parasites of population Af/P4 was amplified by PCR with a primer (O1) that hybridizes upstream from the 5′ end of the TSE and the other (T7) in the bacterial plasmid (Fig. 4e). Restriction analysis of the PCR products indicated that most contained the PacI-tagged sequence insertion, but not the wt AflII site. Thus, in population Af/P4, most integration events had maintained the 4-bp insertion located only 600 bp away from the DSB.

Fate of deletions.

We then tested the fate of deletions in the TSE of plasmid pInco during recombination. The plasmid pInco derivatives pInΔS and pInΔL were constructed which lacked 36 and 105 bp at the 3′ end of the TRAP coding sequence, respectively (Fig. 2b). Transformation experiments were performed with each of these plasmids linearized with SpeI, which cuts ∼1,400 bp from the deletions. All seven resulting populations contained at least 50% of recombinants having one and sometimes more copies of the plasmid integrated into TRAP. In three populations, the corresponding deletion was present in the first duplicate in more than 50% of the recombinant parasites (Table 1). One such population, ΔL3, is analyzed in Fig. 5a to c. As depicted in Fig. 5a and shown by Southern hybridization in Fig. 5b, this population contained wt-like parasites and parasites with one copy of the plasmid integrated into TRAP. The replacement of the 9.5-kb fragment by a 1.8-kb fragment upon MscI-PacI digestion demonstrated that the PacI-tagged deletion was present in the first TRAP duplicate in virtually all integrants. This was confirmed by restriction analysis of PCR products amplified with primers O1 and T7, which specifically amplify the first TRAP duplicates (Fig. 5c). All products amplified from population ΔL3 indeed possessed the PacI site tagging the deletion, but not the PstI site located in the deleted segment. The ∼100-bp deletion was also visible upon comigration of the XbaI-digested products amplified from an Inco clonal population and population ΔL3. Finally, we also introduced a ∼600-bp deletion (HincII-PstI internal fragment of TRAP) in the first TRAP copy by using a similarly deleted pInco derivative linearized at the SpeI site located ∼800 bp upstream (data not shown). These results indicate that large sequence heterologies may be maintained during homologous recombination.

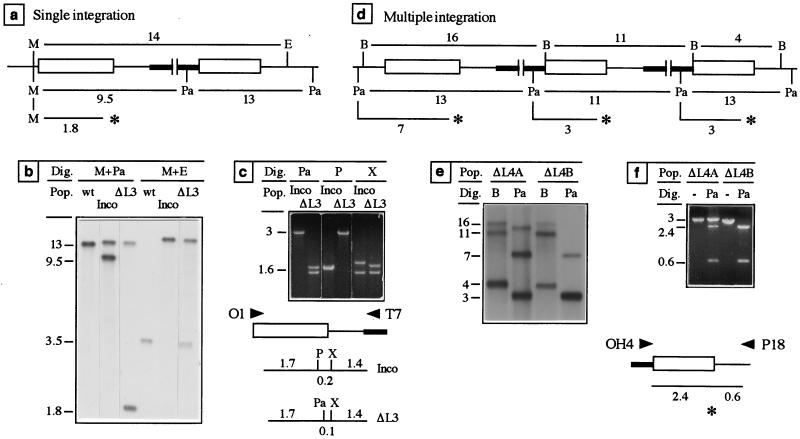

FIG. 5.

Fate of deletions during recombination. (a) Recombinant locus generated by homologous integration of plasmid pInΔL at the TRAP locus. The predicted size (in kilobases) of restriction fragments generated upon digestion with both MscI and EcoRI, which do not cut in the construct, and MscI and PacI, which cut in the cassette, are shown. The presence of the PacI-tagged deletion (asterisk) in the first duplicate is revealed by the cleavage of the 9.5-kb fragment into a 1.8-kb fragment. (b) Southern hybridization with a TRAP probe of the wt, an Inco clonal population, and population ΔL3 obtained after transformation with plasmid pInΔL linearized at the SpeI site. Population ΔL3, which contains a minority of wt-like parasites, mainly consists of integrants having the deletion in the first duplicate. (c) Restriction analysis of the first TRAP duplicates amplified by PCR with primers O1 and T7. The restriction map of the PCR products amplified from a wt (Inco) or deleted (ΔL3) duplicate are shown. All PCR products amplified from population ΔL3 possess the deletion. (d) Recombinant locus generated by homologous integration of more than one copy of plasmid pInΔL at the TRAP locus. The predicted size of the BamHI- and PacI-generated fragments are shown, as well the PacI-generated fragments if the PacI-tagged deletion (asterisks) is present in each of the duplicates. (e) Southern hybridization with a TRAP probe of clones ΔL4A and ΔL4B. Note that digestion with BamHI, which cuts only once in the plasmid backbone, liberates a fragment of the size of the plasmid (11 kb) only when multiple plasmids are integrated. (f) Restriction analysis of PCR products amplified by using primers OH4 and P18 that amplify all duplicates located downstream from a cassette. PacI digestion of the PCR products demonstrates the presence of the PacI-tagged deletion in all duplicates of clone ΔL4B but not clone ΔL4A. −, Uncut DNA. Other symbols and abbreviations are as described in Fig. 3.

Further analysis of parasites cloned from populations ΔL revealed that some recombination events had resulted in the donation of the mutation from the plasmid to the chromosome. When one plasmid unit integrates at the target locus, the process of donation results in the presence of the mutation in both duplicates (15). When more than one plasmid unit integrate (via successive integration events of single plasmid units or from one integration event of a plasmid concatemer), donation is revealed by the presence of the mutation in the last duplicate. Two parasite clones obtained from population ΔL4 are analyzed in Fig. 5d to f to illustrate the process. As depicted in Fig. 5d, (i) integration of multiple plasmids into TRAP is revealed by an additional BamHI-generated fragment of the size of the plasmid (11 kb), (ii) the presence of the deletion in the first duplicate is revealed by the presence of a diagnostic 7-kb PacI-generated fragment, and (iii) the presence of the deletion in the intermediary duplicates is revealed by the disruption of the 11-kb PacI-generated fragment into a 3-kb fragment. As shown by Southern hybridization (Fig. 5e), both clones ΔL4A and ΔL4B conformed to these patterns. However, the two clones differed in that a 13-kb PacI-generated fragment persisted in clone ΔL4A but not in clone ΔL4B. This suggested that the last duplicate of clone ΔL4B, but not in ΔL4A, contained the deletion. This was confirmed after PCR amplification of the TRAP duplicates located downstream from a cassette by using one primer (OH4) that hybridizes at the 3′ end of the cassette and another (P18) in the TSE of the plasmid (Fig. 5f). As expected, the PacI site tagging the deletion was present in all PCR products amplified from clone ΔL4B but not from clone ΔL4A. The transfer of the deletion to the last duplicate of clone ΔL4B probably arose via progression of symmetric hDNA (generated by branch migration of the Holliday junctions) through the deleted sequence in the plasmid, followed by mismatch correction of the hDNAs in favor of the deleted strands on both the plasmid and the chromosome. Such processes of donation should provide valuable candidates for the “hit-and-run” procedures (7, 21), which after a step of plasmid integration as described here aim at selecting intrachromosomal recombination events that leave the mutation in the reconstituted gene.

DISCUSSION

We studied recombination events in P. berghei between the TRAP genomic locus and several types of mutant alleles borne by insertion plasmids. As shown in previous studies (10, 22), insertion plasmids in their uncut, supercoiled forms do not integrate at a detectable level into the genome of P. berghei and plasmid integration is stimulated by introduction of a DSB in the TSE of the plasmid. The recombination reactions promoted here by linearized insertion plasmids were in agreement with the DSB repair model of recombination (19). The model (Fig. 1b) predicts that a mutation located in the region of homology of the plasmid may be corrected during recombination if it falls either within the gap, which is repaired by using wt sequence as a template, or within the flanking hDNA, which may be converted to the wt sequence by the mismatch correction system. As verified in many studies (1, 17, 18), the frequency of correction declines with increasing distance between the DSB and the mutation, and gene conversion tracts can extend from the initiation site in both directions during the same recombination event.

Gene conversion associated with plasmid integration in mitotically dividing yeast cells is thought to occur both via gap expansion and rectification of mismatches in hDNA. The typical length of asymmetric hDNA adjacent to the gap, involving the single-stranded tails, has been estimated to be several hundred base pairs in the yeast plasmid transformation system (12), whereas potential symmetric hDNA, generated by branch migration of the Holliday junctions, may extend up to 4 kb from the DSB (8, 15). Double-strand gap repair has also been demonstrated in mammalian cells (2, 20). Studies have reported that mutations located ∼1 kb from the DSB in an insertion plasmid had only a 25% probability of faithful transfer to the mammalian genome (5, 20), whereas a mutation located ∼4 kb from the DSB had a 95% probability of being maintained in the recombinant locus (5).

The results we obtained here in P. berghei can be summarized as follows. (i) Mutations located close to the DSB (up to ∼0.45 kb) were frequently corrected during plasmid integration. Such a disparity in favor of correction events may suggest that these mutations were degraded via gap extension. However, the fact that insertion plasmids cut 250 bp from one end of the TSE integrated efficiently (at two different genomic loci) suggests that the gap that may form prior to integration and presumably extends in both directions (12, 17) is frequently smaller than 250 bp. The frequent correction of proximal mutations may thus mainly be due to a mismatch correction system that strongly favors the chromosomal strand in the hDNA located close to the DSB. Such differential mismatch repair bias at different distances from the initial site has been reported in yeast cells (6). (ii) Mutations located as far as 1.5 to 2 kb from the DSB could also be corrected during plasmid integration, such as in population Af/S1. This indicates that hDNA can propagate through most of the TSE before resolution of the recombination intermediate and that mismatch repair may still favor the chromosomal strand in hDNA located far from the DSB. (iii) Conversely, a 105-bp deletion located ∼1,500 bp from the DSB could be transferred from the plasmid to the chromosome (clone ΔL4B, see Fig. 5). This implies not only that hDNA may form between two strands bearing large heterologies but also that mismatches in hDNA may be repaired to the plasmid sequence (which presumably occurred in both chromatids of symmetric hDNA in clone ΔL4B). (iv) All mutations (substitutions, insertions, and deletions) located as close as 600 bp and farther from the DSB were nonetheless frequently maintained during recombination. With mutations located between 600 bp and 1 kb from the DSB, 4 of 8 experiments yielded populations with 50% or more of the mutated recombinants, whereas with mutations located more than 1 kb from the DSB, 6 of 11 experiments yielded such populations. These results suggest that the hDNA either frequently stops before it reaches ∼600 bp and/or it may progress farther but is then associated with a mismatch correction system that no longer favors the chromosomal strand.

The main feature of the plasmid transformation system for homologous recombination in yeast or mammalian cells or P. berghei is that plasmid integration is dramatically increased by introduction of a DSB in the TSE of the plasmid. Surprisingly, this appears not to be the case in P. falciparum, in which linearized insertion plasmids are not more proficient for homologous recombination than their circular counterparts (3, 23). However, the transformation procedures differ substantially between the two plasmodial species, not only in the selection methods (in vitro for P. falciparum and in vivo for P. berghei) but also in the parasites transformed (intra-erythrocytic blood stages for P. falciparum or extracellular merozoites for P. berghei). Although some difference in processing linear DNA may exist between the two species, it seems more likely that linear DNA may be more efficiently degraded during P. falciparum transformation.

In P. berghei, the ends-in strategy should be widely applicable to analyze the structure-function relationships of relevant malarial proteins. An ends-in strategy has several advantages over alternative methods for introducing subtle gene modifications. Because the modified gene is expressed at the original locus, it is likely that it is subjected to the same chromosomal effects as the wt gene. In addition, the recombinant locus (Fig. 1a) contains uninterrupted sequences located upstream from the target gene (up to the first duplicate) as well as downstream (starting from the second duplicate). Thus, neighboring genes should be minimally affected by plasmid integration. In contrast, the recombinant locus generated at the target locus with a replacement plasmid (ends-out recombination) contains the foreign DNA upstream (or downstream) from the regulatory sequences of the modified gene, which may disrupt a closely linked locus or affect its expression. Finally, the locus generated by ends-in recombination is stable for numerous generations in the absence of drug pressure, including in mosquito stages of the parasite (16). Methods relying on expression of the modified gene from nonintegrated episomes are limited by the high variability in the copy number of the episomes, as well as by the need to apply selective pressure for maintaining the plasmid in replicating parasites.

We have shown here the reproducible generation of ends-in integrants that had maintained various mutations located at least 500 bp from the DSB. These mutant parasites could in most cases (14 of 19 experiments) be cloned by limiting dilution from first-generation populations obtained at ∼days 10 to 11 postelectroporation. With only 250 bp for the short arm of homology sufficient for crossing-over and the short length (∼500 bp) of gene conversion tracts, it should be possible to express any modification in a P. berghei gene of 1.5 kb by a single-step ends-in strategy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Yi Lu for technical assistance and Victor Nussenzweig and Soren Gantt for reviewing the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from BWF (New Initiative in Malaria Research), the UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme, the Karl-Enigk Foundation, and the NIH (AI-43052). R.M. is a recipient of the Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Award in the Biomedical Sciences.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahn B-Y, Livingston D M. Mitotic gene conversion lengths, coconversion patterns, and the incidence of reciprocal recombination in a Saccharomyces cerevisiae plasmid system. Mol Cell Biol. 1986;6:3685–3693. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.11.3685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brenner D A, Smigocki A C, Camerini-Otero R D. Double-strand gap repair results in homologous recombination in mouse L cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:1762–1766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.6.1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crabb B S, Cowman A F. Characterization of promoters and stable transfection by homologous and nonhomologous recombination in Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7289–7294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crabb B S, Cooke B M, Reeder J C, Waller R F, Caruana S R, Davern K M, Wickham M E, Brown G V, Coppel R L, Cowman A F. Targeted gene disruption shows that knobs enable malaria-infected red cells to cytoadhere under physiological shear stress. Cell. 1997;89:287–296. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80207-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deng C, Thomas K R, Capecchi M R. Location of crossovers during gene targeting with insertion and replacement vectors. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:2134–2140. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.4.2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Detloff P, White M A, Petes T D. Analysis of a gene conversion gradient at the HIS4 locus in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1992;132:113–123. doi: 10.1093/genetics/132.1.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasty P, Ramirez-Solis R, Krumlauf R, Bradley A. Introduction of a subtle mutation into the Hox-2.6 locus in embryonic stem cells. Nature. 1991;350:243–246. doi: 10.1038/350243a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Judd S R, Petes T D. Physical lengths of meiotic and mitotic gene conversion tracts in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 1988;118:401–410. doi: 10.1093/genetics/118.3.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ménard R, Sultan A A, Cortes C, Altszuler R, van Dijk M R, Janse C J, Waters A P, Nussenzweig R S, Nussenzweig V. Circumsporozoite protein is required for development of malaria sporozoites in mosquitoes. Nature. 1997;385:336–340. doi: 10.1038/385336a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ménard R, Janse C. Gene targeting in malaria parasites. Methods. 1997;13:148–157. doi: 10.1006/meth.1997.0507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orr-Weaver T L, Szostak J W. Yeast recombination: the association between double-strand gap repair and crossing-over. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:4417–4421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.14.4417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orr-Weaver T L, Nicolas A, Szostak J W. Gene conversion adjacent to regions of double-strand break repair. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:5292–5298. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.12.5292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orr-Weaver T L, Szostak J W, Rothstein R J. Yeast transformation: a model system for the study of recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:6354–6358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.10.6354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Orr-Weaver T L, Szostak J W, Rothstein R J. Genetic applications of yeast transformation with linear and gapped plasmids. Methods Enzymol. 1983;101:228–245. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)01017-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roitgrund C, Steinlauf R, Kupiec M. Donation of information to the unbroken chromosome in double-strand break repair. Curr Genet. 1993;23:414–422. doi: 10.1007/BF00312628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sultan A A, Thathy V, Frevert U, Robson K, Crisanti A, Nussenzweig V, Nussenzweig R S, Ménard R. TRAP is necessary for gliding motility and infectivity of Plasmodium sporozoites. Cell. 1997;90:511–522. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80511-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun H, Treco D, Szostak J W. Extensive 3′-overhanging, single-stranded DNA associated with the meiosis-specific double-strand breaks at the ARG4 recombination initiation site. Cell. 1991;64:1155–1161. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90270-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sweetser D B, Hough H, Whelden J F, Arbuckle M, Nickoloff J A. Fine-resolution mapping of spontaneous and double-strand break-induced gene conversion tracts in Saccharomyces cerevisiae reveals reversible mitotic conversion polarity. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:3863–3675. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.6.3863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Szostak J W, Orr-Weaver T L, Rothstein R J, Stahl F W. The double-strand-break repair model for recombination. Cell. 1983;33:25–35. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90331-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valancius V, Smithies O. Double-strand gap repair in a mammalian gene targeting reaction. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:4389–4397. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.9.4389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valancius V, Smithies O. Testing an “in-out” targeting procedure for making subtle genomic modifications in mouse embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:1402–1408. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.3.1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Dijk M R, Janse C J, Waters A P. Expression of a Plasmodium gene introduced into subtelomeric regions of Plasmodium berghei chromosomes. Science. 1996;271:662–665. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5249.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu Y, Kirkman L A, Wellems T E. Transformation of Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites by homologous integration of plasmids that confer resistance to pyrimethamine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1130–1134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]