Abstract

MEIOSIS ARRESTED AT LEPTOTENE1 (MEL1), a rice (Oryza sativa) Argonaute (AGO) protein, has been reported to function specifically at premeiotic and meiotic stages of germ cell development and is associated with a novel class of germ cell-specific small noncoding RNAs called phased small RNAs (phasiRNAs). MEL1 accumulation is temporally and spatially regulated and is eliminated after meiosis. However, the metabolism and turnover (i.e. the homeostasis) of MEL1 during germ cell development remains unknown. Here, we show that MEL1 is ubiquitinated and subsequently degraded via the proteasome pathway in vivo during late sporogenesis. Abnormal accumulation of MEL1 after meiosis leads to a semi-sterile phenotype. We identified a monocot-specific E3 ligase, XBOS36, a CULLIN RING-box protein, that is responsible for the degradation of MEL1. Ubiquitination at four K residues at the N terminus of MEL1 by XBOS36 induces its degradation. Importantly, inhibition of MEL1 degradation either by XBOS36 knockdown or by MEL1 overexpression prevents the formation of pollen at the microspore stage. Further mechanistic analysis showed that disrupting MEL1 homeostasis in germ cells leads to off-target cleavage of phasiRNA target genes. Our findings thus provide insight into the communication between a monocot-specific E3 ligase and an AGO protein during plant reproductive development.

The degradation of Argonaute protein MEL1 is mediated by a monocot-specific E3 ubiquitin ligase XBOS36 to avoid off-target regulation of phasiRNAs during rice sporogenesis.

Introduction

Within plant stamen and ovule primordia, sporophytic germ cells produce meiocytes that then generate haploid gametophytes or spores via meiosis. Several genes regulate sporogenesis, and the temporal expression of these genes is important for the progression of sporogenesis (Ma et al., 2008; Wilson and Zhang, 2009; Hu et al., 2011; Shi et al., 2011; Gomez et al., 2015). Particularly during meiosis, most regulatory genes are expressed for only a short period (Klimyuk and Jones, 1997; Grelon et al., 2001; Armstrong et al., 2002; Shao et al., 2011; Mercier et al., 2015; Ren et al., 2019), but how their expression is precisely controlled remains largely unknown.

ARGONAUTE (AGO) proteins bind small RNAs (sRNAs) to form RNA-induced silencing (RISC) complexes for transcriptional and posttranscriptional gene silencing (Zhang et al., 2015). The rice (Oryza sativa) genome contains 19 AGO family members (Kapoor et al., 2008), some of which participate in sexual reproduction (Kapoor et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2013). For instance, AGO9 controls female gamete formation in Arabidopsis thaliana (Olmedo-Monfil et al., 2010); in addition, AGO17 (Pachamuthu et al., 2020) and AGO18 (Das et al., 2020) control yield-associated traits and sporogenesis, respectively, in rice.

Several AGOs are controlled via proteasomal degradation, including AGO1 in plants and mammals and AGO2 in Drosophila and mammals (Chiu et al., 2010; Mukhopadhyay et al., 2019). The ubiquitin-proteasome system regulates a broad range of physiologically and developmentally controlled processes in all eukaryotes (Ciechanover et al., 2000; Wang and Le, 2019). The process is mediated by an enzymatic cascade that begins with the E1 ubiquitin (Ub)-activating enzyme that presents an Ub molecule to the E2 Ub-conjugating enzyme. The E3 Ub-ligase transfers the Ub molecule from the E2 enzyme to the substrates, triggering the subsequent degradation of the ubiquitinated protein by the 26S proteasome. Several hundred E3s have been identified in plant genomes based on characteristic structural motifs. Among them, CULLIN RING ubiquitin ligases (CRLs) are the most prevalent class (Petroski and Deshaies, 2005; Hua and Vierstra, 2011). However, the function of most E3s is unknown.

MEIOSIS ARRESTED AT LEPTOTENE1 (MEL1), a rice AGO protein, functions specifically in the development of premeiotic germ cells and the progression of meiosis (Nonomura et al., 2007). The accumulation of rice MEL1 protein is temporally and spatially regulated: MEL1 is highly abundant in pollen mother cells (PMCs) and early meiotic stages but is eliminated after meiosis (Nonomura et al., 2007). Phylogenetic and cytological analyses suggest that MEL1 is a plant AGO protein that functions to maintain germ cell identity (Nonomura et al., 2007). MEL1 has attracted attention due to its association with a novel class of germ cell-specific small noncoding RNAs, called phased small RNAs (phasiRNAs), mainly 21-nt phasiRNAs (Komiya et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2020). We and other colleagues recently revealed that MEL1-dependent 21-nt phasiRNAs are essential for the elimination of a specific set of RNAs during meiotic prophase I (Jiang et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). Although the biogenesis of phasiRNA/dicer-like protein (DCL)/MiR-2118 machinery was well understood during premeiotic and meiotic stages (Fei et al., 2013; Komiya et al., 2014; Patel et al., 2018), the metabolism and turnover of MEL1 in germ cell development remained largely unknown.

Here, we examined whether the precise regulation of MEL1 homeostasis is important for gametogenesis and how it is maintained during sporogenesis. We also tested whether abnormal accumulation of MEL1 protein leads to off-target cleavage of phasiRNA target genes during rice sporogenesis. We showed that MEL1 is ubiquitinated and subsequently degraded via the proteasome pathway in vivo during late sporogenesis. We further identified a monocot-specific E3 ligase, XBOS36, that is responsible for the degradation of MEL1. Importantly, inhibition of MEL1 degradation either by knockdown of XBOS36 or by overexpression of MEL1 prevented the formation of pollen at the microspore stage (MS), due to misregulation of target genes of the phasiRNA–MEL1 complex. Our results indicate that proper temporal regulation of MEL1 is essential for mRNA regulation during pollen development and for normal sporogenesis in rice.

Results

Temporal accumulation of MEL1 is necessary for sporogenesis

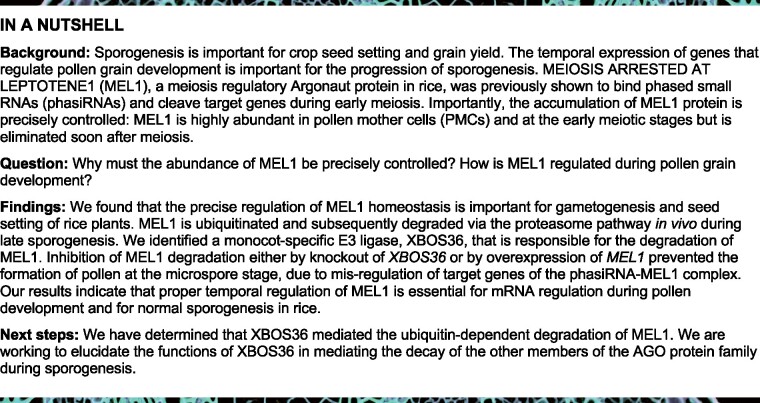

To investigate the significance of the temporal accumulation of MEL1 protein during sporogenesis, we first assessed the accumulation pattern of MEL1 protein during pollen development. MEL1 protein signals first appeared at the floral organ differentiation stage (FDS) and elevated to the highest level at the PMC formation stage (PFS), after which its level declined from late meiosis stages (LMSs; Figure 1A, upper part). MEL1 was nearly absent at the MS; Figure 1A), indicating that MEL1 is under precise control during sporogenesis. At the FDS and PFS, MEL1 mRNA showed a similar accumulation pattern to that of MEL1 protein (Figure 1A, lower part; Supplemental Figure S1A); however, unlike its mRNA level, MEL1 protein began to decline in LMSs and almost disappeared in the MS, suggesting that MEL1 protein levels could be posttranscriptionally regulated.

Figure 1.

Temporal accumulation of MEL1 is necessary for sporogenesis. A, Accumulation patterns of MEL1 protein (upper) and mRNA during sporogenesis (lower). The spikelets with the same anther length at the same developmental stage determined by DAPI were collected for immunoblot analysis. GDS, glume differentiation stage; MS, microspore stage. HSP was used as reference protein, and GAPDH was used as reference gene. The MEL1 densitometric ratio was recorded by ImageJ. The relative abundance of MEL1 at PFS was set to 1. B, Abundance of MEL1 protein in the OXMEL1 spikelet at the PFS (left) and the MS (right). The MEL1 densitometric ratio was recorded by ImageJ. The relative abundance of MEL1 in WT (PFS, MS) was set to 1, respectively. C, Seed-setting rates of OXMEL1 plants. Values are means ± sd (n≥13 plants). Box plots indicate median (middle line), 25th and 75th percentiles (box), and 10th and 90th percentiles (whiskers) as well as outliers (single points). Significant differences were identified at the 0.01 (**) probability levels using Student’s t test. D, Panicle and pollen grains of OXMEL1 plants. Scale bars, 5 cm for the panicles and 50 µm for pollen grains.

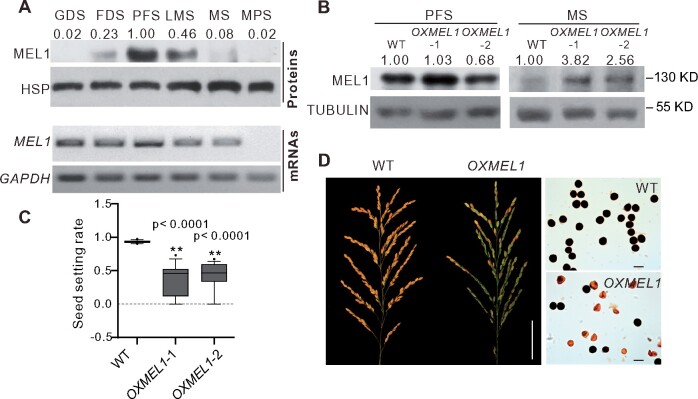

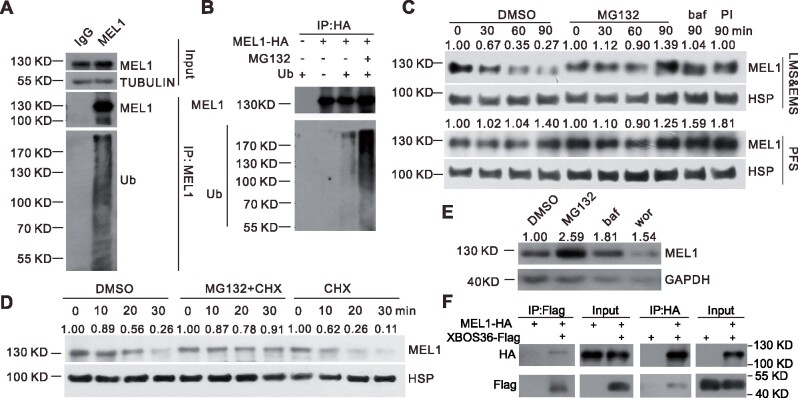

To investigate the effects when MEL1 abnormally accumulated in late sporogenesis, we overexpressed MEL1 (OXMEL1; Figure 1B). Unexpectedly, OXMEL1 lines showed a semi-sterile phenotype (Figure 1C). Half of the pollen grains of OXMEL1 plants were aborted at the mature pollen stage (MPS; Figure 1D), whereas loss of function of MEL1 in the mel1 mutants caused complete sterility of pollen grains at the early MS (Zhang et al., 2020). We then investigated the microspore development of OXMEL1 plants using 4ʹ,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining and semi-thin sectioning. A clear difference between OXMEL1 and wild-type (WT) microspores was observed at PMC anaphase II. About half of the OXMEL1 tetrads were abnormally divided (Figure 2, A and B). At the early MS (EMS), the OXMEL1 microspores had a crescent moon shape, while WT microspores were round (Figure 2C). These phenotypes were different from those observed in mel1 mutants, in which most of the PMCs did not finish meiosis and were arrested at prophase I (Figure 2A). We also observed that MEL1 mRNA accumulated consistently during sporogenesis in the OXMEL1 plants (Supplemental Figure S1B); in contrast, MEL1 protein levels declined from meiosis to the late MS (Supplemental Figure S1B), although MEL1 levels were slightly higher than those in WT plants (Figure 1B). These results suggested that the degradation of MEL1 in the LMS and the MS could be essential for pollen development and maturation.

Figure 2.

OXMEL1 plants have abnormal tetrad and microspores. A, DAPI staining of the PMCs of WT and OXMEL1 plants during meiosis. Scale bars, 10 µm. B, The aberrant tetrad rate of OXMEL1 plants. n = 3 replicates. Significant differences were identified at the 0.01 (**) probability levels using Student’s t test. C, Semi-thin section of WT and OXMEL1 anthers during sporogenesis. Scale bars, 20 µm.

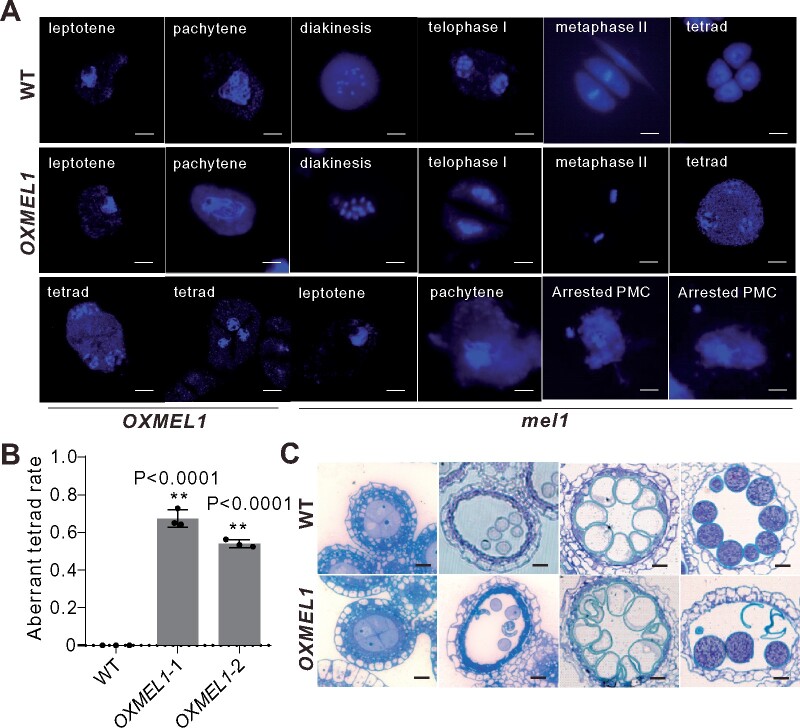

MEL1 is degraded by the 26S proteasome and directly interacts with three candidate E3 ligases

Next, we investigated MEL1 protein turnover. To determine whether MEL1 is regulated by 26S proteasomes, we first purified MEL1 from rice panicles at the LMS using MEL1 antibody. Immunoblot analysis showed that MEL1 is ubiquitinated in vivo (Figure 3A). MEL1 purified from rice protoplasts transfected with the Pro35S:MEL1-HA plasmid was also ubiquitinated (Figure 3B). After treatment with MG132 to inhibit the 26S proteasome-mediated protein degradation, more ubiquitinated MEL1 was detected (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

MEL1 is degraded by the 26S proteasome. A, In vivo ubiquitination assay for MEL1 protein. Total protein from rice panicles at MS was extracted in IP buffer and incubated with anti-MEL1 antibody. Anti-IgG was used as a control. Proteins in the eluate were detected by immunoblot using anti-ubiquitin (Ub), anti-TUBULIN and anti-MEL1 antibodies. B, In vitro ubiquitination assay for MEL1 protein in WT protoplasts. MEL1 protein was coexpressed with Ub or without Ub in the WT rice protoplasts treated with MG132 or without. Total protein from each sample was extracted in IP buffer and incubated with anti-MEL1 antibody. Proteins in the eluate were detected by immunoblot using anti-Ub and anti-MEL1 antibodies. C, In vivo degradation assay for MEL1 protein. Protein extracts from WT panicles at different developmental stages were treated with MG132 (50 µM) for 0, 30, 60, and 90 min and detected by anti-MEL1 antibody. DMSO and autophagy inhibitors were used as control. baf, bafilomycin. PI, protease inhibitor cocktail. The MEL1 densitometric ratio was recorded by ImageJ. The relative abundance of MEL1 at 0 min (DMSO, MG132) was set to 1, respectively. D, Stability of MEL1 in extracts prepared from WT panicles treated with MG132 (50 µM) and CHX (10 μM) for the indicated times (0, 10, 20, and 30 min). DMSO was used as a control. The MEL1 densitometric ratio was recorded by ImageJ. The relative abundance of MEL1 at 0 min (DMSO, MG132+CHX, CHX) was set to 1, respectively. E, In vitro degradation assay for MEL1 protein. MEL1 was expressed in the WT rice protoplasts. After overnight culture, protoplasts were treated with MG132 (50 µM) and DMSO for 4 h, and detected by anti-MEL1 antibody. Two autophagy inhibitors, bafilomycin (baf) and wortmannin (wor), were used as control. The MEL1 densitometric ratio was recorded by ImageJ. The relative abundance of MEL1 treated with DMSO was set to 1. F, XBOS36 interacted with MEL1-HA in the pull-down assay. XBOS36-FLAG protein extracted from E. coli was incubated with MEL1-HA as indicated followed by pull-down with resin. The proteins in the eluate were detected using anti-HA and anti-FLAG antibodies.

Next, we used a cell-free degradation assay to check the MEL1 ubiquitination status. In these assays, Escherichia coli-expressed MEL1 proteins were incubated with proteins extracted from rice panicles at the PFS or at LMS and EMS and the remaining MEL1 levels were examined. In the presence of MG132, MEL1 was more stable compared with mock-treated control when incubated with proteins extracted from panicles at late meiosis and EMSs (Figure 3C). No significant difference in MEL1 protein abundance was observed between the MG132 treatment and the DMSO (mock) treatment when incubated with protein extracted from panicles at the PFS (Figure 3C). We also used the protein biosynthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (CHX, 100 mM) to block protein biosynthesis in the cell-free degradation assay: CHX treatment had no observable effect on MEL1 protein degradation, suggesting that MEL1 was posttranslationally regulated (Figure 3D).

We further measured MEL1 stability in rice protoplasts. Protoplasts transfected with the Pro35S:MEL1-HA plasmid were cultured in darkness for 12 h and then treated with MG132 for 4 h. The result showed that MG132 stabilized MEL1 compared with the control (Figure 3E). Together, these data suggested that the turnover of MEL1 is mediated by the 26S proteasome pathway. To determine the pathways MEL1 may be involved in, we next investigated the interactors MEL1 directly binds with via immunoprecipitation (IP) with mass spectrometry (IP–MS). Total proteins were extracted from panicles during the LMS and EMS and were immunoprecipitated by anti-MEL1 antibody, and then subjected to mass spectrometry analysis (Supplemental Data Set 1). In total, we identified three candidate-interacting proteins, rice XB3 protein homolog 6 (XBOS36), Plant U-box protein 72 (PUB72), and zinc finger CCCH domain-containing protein 15 (C3H15), that might associate with the ubiquitin-proteasome complex. XBOS36 and C3H15 are RING-box proteins, and PUB72 is a U-box protein. Because proteins with a RING box or U box usually function as E3 ubiquitin ligases, they were identified as potential MEL1 interactors for ubiquitin/26S proteasome-mediated degradation. To validate their interaction, we then examined the physical association between MEL1 and the three candidate E3s using coimmunoprecipitation (CoIP) experiments. Another validated rice RING finger (RF) E3 ubiquitin ligase (SOR1; Chen et al., 2018) was used as a control. HA-tagged MEL1 immunoprecipitated with the HA antibody when coexpressed with the Flag-tagged putative E3 ligases in rice protoplasts. We also immunoprecipitated the three putative E3 ligases with Flag antibody when coexpressed with MEL1-HA. The results indicated that MEL1 directly interacted with XBOS36, PUB72, and C3H15 but not SOR1 (Figure 3F; Supplemental Figure S1C). Thus, MEL1 is degraded by the 26S proteasome and directly interacts with three candidate E3 ligases

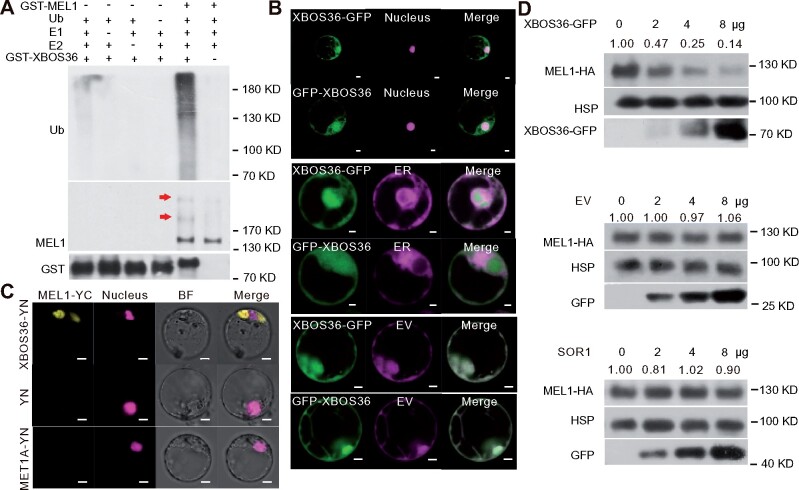

XBOS36 is a novel E3 ubiquitin ligase and mediates the ubiquitination of MEL1

The above results showed that MEL1 could directly interact with the three candidate-interacting proteins XBOS36, PUB72, and C3H15. Next, we used an in vitro ubiquitination assay to test whether XBOS36, PUB72, and C3H15 could ubiquitinate MEL1. All proteins, including E1, E2, GST-tagged-putative E3s (GST-XBOS36, GST-PUB72, and GST-C3H15), and MEL1-HA, were purified from E. coli. Self-ubiquitination of the three putative E3s was also detected in the presence of both E1 and E2 components. Only XBOS36 possessed auto-ubiquitination activity when recombinant E1, E2, and Ub-Flag and ATP were added (Supplemental Figure S1D), suggesting that XBOS36 could be an E3 enzyme. XBOS36 is an Ankyrin repeat domain and RF-containing protein, and it was shown to be a monocot-specific E3 ligase by homology analysis. However, there are no reports on the function of this kind of RING-E3 protein in rice. Notably, a ladder-like pattern indicative of ubiquitinated MEL1-His was detected in the ubiquitination reaction in the presence of XBOS36, but not PUB72 or C3H15 despite of using different E2s, indicating that XBOS36 ubiquitinates MEL1 (Figure 4A; Supplemental Figure S1E).

Figure 4.

MEL1 interacts with XBOS36. A, GST-XBOS36 ubiquitinated MEL1 in the ubiquitination assay in vitro. Proteins in the samples of ubiquitination assay were detected by anti-Ub, anti-MEL1, and anti-GST antibodies. Arrows indicate ubiquitinated MEL1 proteins. B, Subcellular localization of XBOS36 protein. Fluorescence signals of rice protoplasts were detected by confocal microscopy after overnight culture. Magenta fluorescence indicates nuclear signal, ER signal, or EV signal, and green fluorescence indicates the subcellular distribution pattern of XBOS36 protein. Scale bars, 5 µm. C, XBOS36 interacted with MEL1 in the BiFC assay. BiFC signals of rice protoplasts were detected by confocal microscopy after overnight culture. Magenta fluorescence indicates nuclear signal, and yellow fluorescence indicates positive interactions. YN and MET1A (DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferase 1A, Oryza sativa) were used as negative controls. Scale bar, 5 µm. D, Stability of MEL1-HA in protoplasts transfected with different amounts (0, 2, 4, and 8 μg) of ProUbi:XBOS36-GFP, EV, or SOR1-GFP plasmids. HSP90 was used as a control. Proteins in the protoplasts were detected by anti-HA, anti-GFP, and anti-HSP90 antibodies. The MEL1 densitometric ratio was recorded by ImageJ. The relative abundance of MEL1-HA transfected with 0 μg plasmids (XBOS36-GFP, EV and SOR1-GFP) was set to 1, respectively.

We then investigated the subcellular localization of these four proteins. PUB72 and C3H15 were located in the nucleus (Supplemental Figure S2A), whereas XBOS36 localized to both the cytoplasm and nucleus (Figure 4B; Supplemental Figure S2B). As MEL1 has been reported to be present mostly in the cytoplasm of germ cells (Komiya et al., 2014), MEL1 degradation might occur through the cytosolic ubiquitin-proteasome system mediated by XBOS36. Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) analysis suggested that MEL1 and XBOS36 interact mainly in the cytoplasm (Figure 4C). To test the effect of XBOS36 on MEL1 stability in plant cells, we transiently cotransfected Pro35S:MEL1-HA and increasing amounts of Pro35S:XBOS36-GFP plasmids in rice protoplasts. After the protoplasts were cultured for 16 h, the total proteins were extracted and used for immunoblotting. The MEL1 level gradually decreased with increasing amounts of XBOS36-GFP, but MEL1 levels were not reduced in the control transfected with increasing amounts of empty vector (EV) or control SOR1, indicating that XBOS36 promotes MEL1 degradation (Figure 4D). These results suggested that XBOS36 is an E3 ubiquitin ligase and MEL1 degradation might be mediated by the cytosolic ubiquitin-proteasome system.

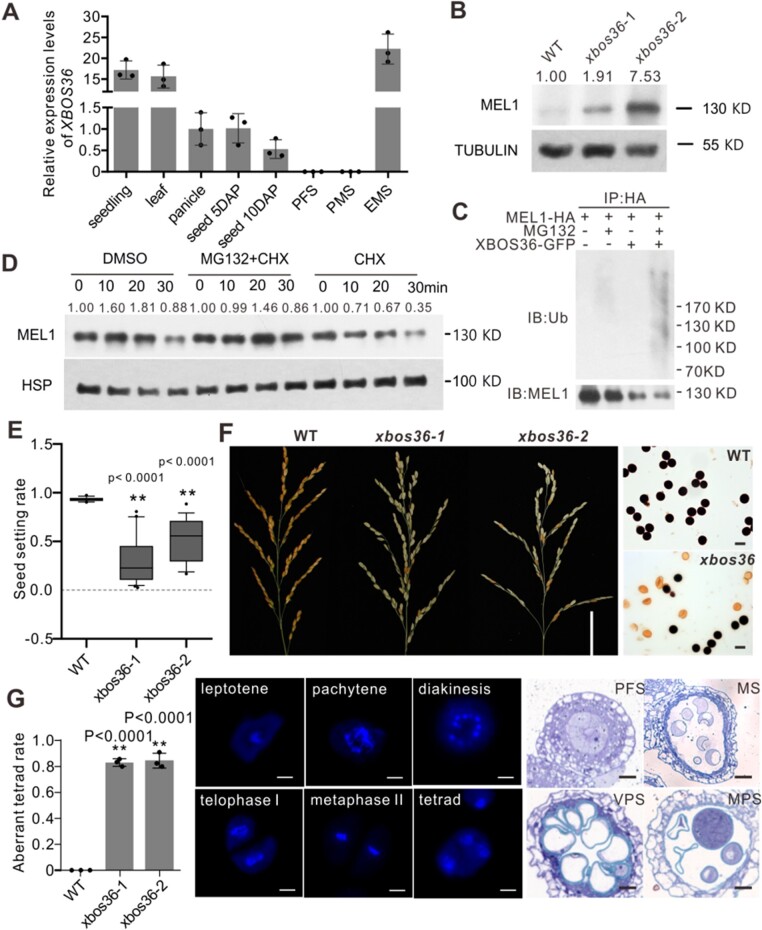

XBOS36 has an opposite expression pattern from that of MEL1 and is required for postmeiotic sporogenesis

Our above results established XBOS36 as an E3 ligase-promoting MEL1 degradation. We further explored this interaction in planta. First, we investigated the temporal and spatial accumulation of XBOS36 protein during plant development and sporogenesis. Notably, XBOS36 and MEL1 showed opposite expression patterns during rice development. XBOS36 was highly expressed in vegetative organs, but its abundance declined dramatically in reproductive organs (Figure 5A). During sporogenesis, XBOS36 transcript was not present in the PFS and PMC meiosis stage (PMS), but sharply increased from the EMS, when the MEL1 protein started to degrade (Figure 5A). This opposing accumulation pattern further suggested a correlation between MEL1 and XBOS36 in vivo.

Figure 5.

XBOS36 is important for the degradation of MEL1 and normal pollen development. A, Relative expression of XBOS36 mRNAs in different organs. Seedling, 14 days after germination (DAG) seedlings; leaf, 20 DAG leaves; panicle, mature panicles; seed 5DAP, 5 day after pollination seeds; seed 10DAP, 10 days after pollination seeds; PFS, spikelets at the PFS; PMS, spikelets at the PMC meiosis stage; EMS, spikelets at the EMS. Values are means ± sd (n = 3 replicates; dots). The expression levels of XBOS36 are relative to those in the panicle, which is set to 1. B, Stability of MEL1 in xbos36 mutants. Total proteins were extracted from WT and mutant panicles at the MS, and anti-MEL1 antibody was used to detect MEL1 protein by immunoblot. The MEL1 densitometric ratio was recorded by ImageJ. The relative abundance of MEL1 in the WT was set to 1. C, In vitro ubiquitination assay for MEL1 protein in xbos36 protoplasts. MEL1 was coexpressed with or without XBOS36-GFP in xbos36 protoplasts treated or not with MG132. Total protein from each sample was extracted in IP buffer and incubated with anti-MEL1 antibody. Proteins in the eluate were detected by anti- Ub and anti-MEL1 antibodies. D, Stability of MEL1 protein in extracts prepared from xbos36 panicles treated with MG132 (50 µM) and CHX (10 μM) for the indicated times (0, 10, 20, and 30 min). DMSO was used as a control. Anti-MEL1 antibody was used to detect MEL1 protein. The MEL1 densitometric ratio was recorded by ImageJ. The relative abundance of MEL1 at 0 min (DMSO, MG132+CHX, CHX) was set to 1, respectively. E, Seed-setting rates of WT and xbos36 plants. Values are means ± sd (n≥13 plants). Box plots indicate median (middle line), 25th and 75th percentiles (box), and 10th and 90th percentiles (whiskers) as well as outliers (single points). Significant differences were identified at the 0.01 (**) probability levels using a Student’s t test. F, The panicles and pollen grains of WT and xbos36 plants. Scale bars, 5 cm for the panicles and 50 µm for pollen grains. (G) The meiosis process and sporogenesis process of xbos36 plants. Scale bars, 10 µm for PMCs and 20 µm for the sections. VPS, vacuolated pollen stage. n = 3 replicates. Significant differences were identified at the 0.01 (**) probability levels using a Student’s t test.

We hypothesized that the sharp increase of XBOS36 protein levels in the MS might promote the degradation of MEL1 to maintain the development of pollen. To test this, we constructed XBOS36-knockout mutant plants (xbos36) using clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) genome editing. To determine whether XBOS36 mediates MEL1 degradation in plant cells, we compared MEL1 protein levels between xbos36 and the WT plants during sporogenesis. Immunoblot analysis indicated no apparent difference in MEL1 protein levels between xbos36 and WT panicles at the PFS, but significantly more MEL1 accumulated in the xbos36 mutant than in the WT in the EMS (Figure 5B), whereas similar MEL1 mRNA expression levels were observed between xbos36 and WT plants at both stages (Supplemental Figure 2C), suggesting that the higher accumulation of MEL1 in the xbos36 mutant than in the WT was attributable to posttranscriptional regulation. Next, we obtained protoplasts from the xbos36 mutants, and then, MEL1 protein was coexpressed with XBOS36-GFP or without XBOS36-GFP in the xbos36 protoplasts treated or not with MG132. As shown in Figure 5C, MEL1 ubiquitination was clearly enhanced when coexpressing XBOS36, suggesting XBOS36 is needed for MEL1 ubiquitination. To examine the effect of XBOS36 on MEL1 degradation in plants, we treated xbos36 panicles with CHX at the EMS to block protein translation and then performed an immunoblot assay to analyze MEL1 protein levels. The degradation of MEL1 occurred more slowly in the xbos36 mutant than in the WT (Figures 3D, 5D; Supplemental Figure 2D), indicating that XBOS36 posttranslationally modifies MEL1 in plants.

Next, we compared the phenotype of the xbos36 mutant to those of the WT and OXMEL1 plants. The xbos36 mutant had a similar semi-sterile phenotype to that of OXMEL1 plants (Figure 5E). The xbos36 pollen grains were aborted at the MPS (Figure 5F), and the abnormal development of pollen grains started from late meiosis; about 80% of the xbos36 tetrads did not divide normally (Figure 5G). These phenotypes were consistent with that observed in the OXMEL1 lines, indicating that degradation of MEL1 mediated by XBOS36 is essential for postmeiotic sporogenesis in rice.

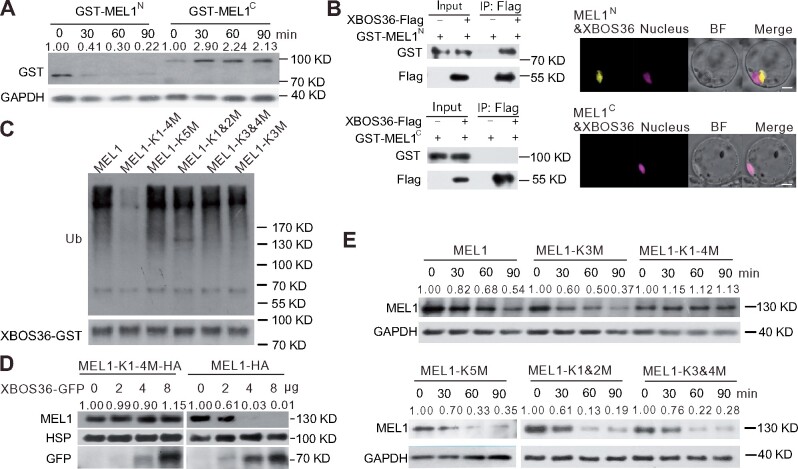

Ubiquitination at four K residues at the N terminus is responsible for the degradation of MEL1

For protein degradation through the ubiquitin-proteasome system, targeted proteins are polyubiquitinated at lysine residue(s), followed by proteolysis by the 26S proteasome; therefore, we next investigated which region and sites of MEL1 were ubiquitinated. The N-terminal fragment, which contains the DUF domain of MEL1, and the C-terminal fragment, which contains the PIWI domain of MEL1, were generated respectively, named GST-MEL1N and GST-MEL1C (Supplemental Figure 3A), and were examined in a cell-free degradation assay followed by IP and immunoblot assays. When incubated with protein extracts from rice panicles at the late meiosis and EMSs, the GST-MEL1N proteins degraded more quickly than GST-MEL1C proteins (Figure 6A). To further test the direct binding of XBOS36 on the MEL1 DUF fragment, we performed CoIP and BiFC experiments to analyze the interaction between XBOS36 and MEL1N or MEL1C. The result showed that XBOS36 might preferentially bind to the N-terminal fragment but not the C-terminal fragment of MEL1 (Figure 6B). Together, these data indicate that the N terminal fragment of MEL1 plays a major role in the ubiquitination of MEL1.

Figure 6.

The N terminal of MEL1 is responsible for its degradation and its interaction with XBOS36. A, Stability of GST-MEL1N and GST-MEL1C in protein extracts from rice panicles. E. coli-expressed GST-MEL1N and GST-MEL1C proteins were purified by GST resin and incubated with plant protein extracts prepared from rice panicles at the MS. GAPDH was used as a control. The GST-MEL1N and GST-MEL1C densitometric ratio was recorded by ImageJ. The relative abundance of GST-MEL1N and GST-MEL1C at 0 min was set to 1, respectively. B, XBOS36 interacts with N terminal fragment of MEL1 in pull-down and BiFC assays. Recombinant GST-MEL1C, GST-MEL1N, and XBOS36-Flag proteins purified from E. coli were incubated in tubes as indicated, followed by pull-down with resin. The proteins in the eluate were detected using anti-GST and anti-FLAG antibodies. BiFC signals were detected after overnight culture by confocal microscopy. Red fluorescence indicates nuclear signal, and yellow fluorescence indicates positive interactions. Scale bar, 5 µm. C, The K1–4M version of MEL1 failed to be ubiquitinated by GST-XBOS36. D, Stability of MEL1-HA and K1-4 to R-mutated version of MEL1 protein in protoplasts transfected with different amounts (0, 2, 4, and 8 μg) of ProUbi:XBOS36-GFP plasmids. HSP90 was used as a control. The MEL1 densitometric ratio was recorded by ImageJ. The relative abundance of MEL1-HA and MEL1-K1-4M-HA transfected with 0 μg XBOS36-GFP was set to 1, respectively. E, Stability of different K to R-mutated versions of MEL1 in protein extracts from rice panicles. The upper blots showed the K3(MEL1-K3M) or K1-4 (MEL1-K1-4M) to R-mutated MEL1 proteins; the lower blots showed the K5(MEL1-K5M), K1&2(MEL1-K1&2M), or K3&4(MEL1-K3&4M) to R-mutated MEL1 proteins. E. coli-expressed K to R-mutated MEL1 proteins were purified by GST resin and then incubated with plant protein extracts prepared from rice panicles at the MS for the indicated times (0, 30, 60, and 90 min). GAPDH was used as a control. The MEL1 densitometric ratio was recorded by ImageJ. The relative abundance of different versions of MEL1 at 0 min was set to 1, respectively.

We next investigated the specific ubiquitination site in the MEL1N segment that was responsible for MEL1 degradation. Previous studies have reported that lysine (K) is the amino acid that is typically modified with polyubiquitination (Sadowski et al., 2012; McDowell and Philpott, 2016; Swatek and Komander, 2016). Five lysines (K1, K2, K3, K4, and K5) were predicted to be the potential polyubiquitin modification sites by UbPred (Radivojac et al., 2010), and four of them (K1, K2, K3, and K4) exist at the N terminus of MEL1 and may be responsible for its degradation (Supplemental Figure 3A). We mutated these five lysine residues to arginine (R) to identify the specific ubiquitination site. Notably, when K5, K3, K1 and K2, or K3 and K4 were mutated, the extent of ubiquitination of MEL1 was unchanged (Figure 6C). Only the K1–4 mutant isoform that mutated all the 4 Ks showed reduced ubiquitination after treatment with MG132 when E1, E2, Ub, and XBOS36 were added (Figure 6C). We overexpressed the MEL1-K1–4 mutant isoform in rice protoplasts and observed that it was more stable than WT MEL1 in both the protoplast system and the cell-free degradation assay (Figure 6, D and E). On the basis of these observations, we proposed that all four Ks at the N terminus of MEL1 are responsible for its degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome system.

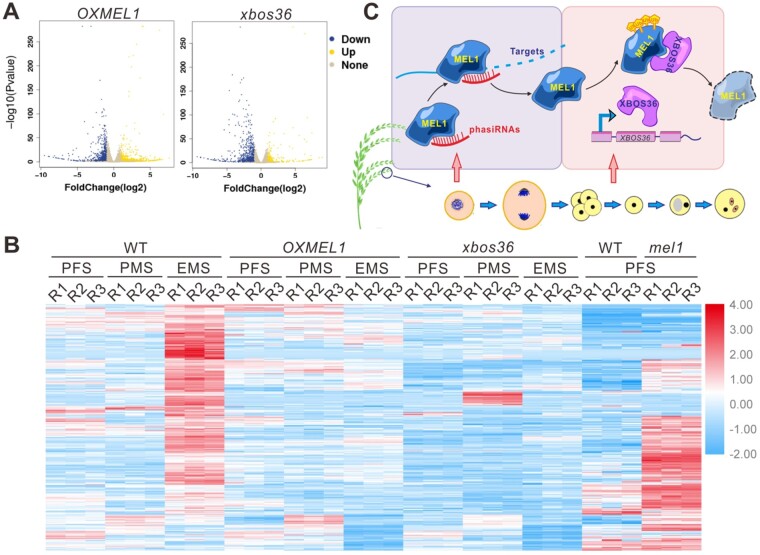

Abnormal accumulation of MEL1 in microspores leads to off-target cleavage of phasiRNA target genes

Our results clearly showed that MEL1 ubiquitination and degradation in the EMS is essential for normal pollen development and seed setting, and XBOS36 plays a critical role in the degradation of MEL1. We recently showed that MEL1 functions by combining phasiRNAs and mediating the degradation of specific mRNAs during early meiosis (Zhang et al., 2020). Therefore, we questioned if MEL1 stabilization in microspores leads to off-target cleavage and, as a result, to pollen sterility. To this end, we collected the spikelets of WT, OXMEL1, and xbos36 plants at the PFS, PMC meiosis stage (PMS), and EMS for transcriptome sequencing with three replicates, respectively, to search for misregulated genes. We also applied the data of the MEL1 knockout mutant (mel1; Zhang et al., 2020) for comparison.

We first identified the differentially expressed genes between OXMEL1, xbos36, and WT plants. In the OXMEL1 line 822 protein-coding genes were significantly downregulated at EMS, whereas 654 protein-coding genes were significantly upregulated. In the xbos36 line, 805 protein-coding genes were significantly downregulated at EMS, whereas only 212 protein-coding genes were significantly upregulated (Figure 7A); thus, most genes were downregulated when disturbing MEL1 homeostasis at EMS. Moreover, 40.0% of the downregulated genes were both downregulated in the OXMEL1 and xbos36 lines (Supplemental Data Set 2; Supplemental Figure 3B). We previously reported that MEL1 loss of function causes upregulation of mRNAs at early meiosis stages through mediating the cleavage of phasiRNA target genes. Most of the differentially expressed genes had opposite expression patterns in the OXMEL1 and mel1 plants, in that most of the genes that were downregulated in the OXMEL1 and xbos36 lines were upregulated in mel1 mutants, indicating that these genes are under the regulation of MEL1 (Figure 7B). Thus, we hypothesized that the downregulation of mRNAs in the OXMEL1 lines might be caused by the activity of the MEL1–phasiRNA complex at the stage when MEL1 would be degraded.

Figure 7.

Abnormal accumulation of MEL1 in microspores leads to off-target regulation of phasiRNAs. A, Volcano plot of the DEGs in WT, OXMEL1, and xbos36 plants. Genes downregulated in OXMEL1 or xbos36 plants are marked in blue, and genes upregulated in OXMEL1 plants are marked in yellow. B, Heatmap showing the expression patterns of the downregulated genes in both the OXMEL1 and the xbos36 lines compared with WT at EMS in WT, OXMEL1, xbos36, and mel1 plants at the PFS, PMC meiosis stage (PMS), and EMS. The heatmap was generated using TBtools (Chen et al., 2020). C, Working model for MEL1 and XBOS36 function during sporogenesis. MEL1 proteins accumulate at meiosis prophase I and mediate the cleavage of phasiRNA targets. After meiosis, MEL1 proteins are ubiquitinated by XBOS36 and are degraded at the MS.

To address this possibility, we further analyzed whether these downregulated genes are targets of the MEL1–phasiRNA complex. We reanalyzed our degradome data previously generated in WT spikelets during sporogenesis and identified the cleaved targets of the MEL1–phasiRNA complex among the downregulated genes in the OXMEL1 lines. In total, 30.0% of the genes that were downregulated in both the OXMEL1 lines and the xbos36 lines were shown to be cleaved at the potential phasiRNA binding sites, and thus might be the direct targets of the MEL1–phasiRNA complex. These genes that were both downregulated in the OXMEL1 and xbos36 lines were enriched for nutrient reservoir activity, transcription regulator activity, transcription factor activity, and endopeptidase inhibitor activity (Supplemental Data Set 3), suggesting that disturbing MEL1 homeostasis in germ cells affects the expression of a set of genes and in turn suppresses sporogenesis processes. Together, our data suggested that MEL1 is ubiquitinated by the monocot-specific E3 ligase XBOS36 after meiosis, and disturbing MEL1 homeostasis in germ cells leads to off-target regulation of phasiRNA target genes and sterility of pollen grains (Figure 7C).

Discussion

AGO proteins are the prime effectors of sRNA-mediated regulatory elements for gene expression in most eukaryotes. This system comprises an evolutionarily ancient developmental regulator and innate immune response in plants, and it is not surprising that the abundance of AGO proteins is tightly regulated by highly programmed regulatory consoles. Posttranslational modifications (PTMs) of proteins are essential to control the abundance and functional diversity of proteins, and thereby influence most biological processes. Most studies on sRNAs have focused on improving our understanding of processing and functional mechanisms, whereas knowledge on PTMs of the sRNA regulatory machinery is still rudimentary, especially in plants.

Significant molecular insights on the posttranslational control of metazoan AGO proteins emerged only recently. First, it has been shown that the molecular chaperone HSP90 is required for the stability of mammalian AGO1 and AGO2 (Johnston et al., 2010). In plants, IP assays revealed that an enrichment of polyubiquitin conjugates of AGO1 and MLN-4924, a drug that inhibits the activity of CRLs, impaired P0-dependent AGO1 degradation in Arabidopsis (Derrien et al., 2012). Most studies on homeostatic mechanisms of AGOs focused on virus infection processes. However, how AGOs are regulated during plant development is still unclear. MEL1 is crucial for meiosis in rice and was shown to be temporally and spatially regulated, which might be to prevent the misloading of unintended phasiRNAs into the RISC complex since this regulatory complex has the capacity to regulate off-target genes bearing minimal sequence complementarity, but the underlying mechanism is unknown. In this study, we showed that MEL1 is ubiquitinated and subsequently degraded through the proteasome pathway mediated by an E3 ligase XBOS36 in vivo during late sporogenesis. Inhibition of MEL1 degradation prevents the formation of pollen at the MS. Moreover, stabilization of MEL1 after meiosis significantly downregulated a set of genes involved in nutrient reservoir and transcriptional regulation, and some of these genes are the cleaved targets of the MEL1–phasiRNA complex. But the functions of most of the genes have not been reported yet (Jiang et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). Thus, failed degradation of sRNA regulatory machinery might mis-regulate the target genes of sRNAs. Our results provide insight into the AGO regulatory mechanism during plant reproductive development.

The Arabidopsis genome encodes two E1s, approximately 40 E2s and over 1,400 putative E3 ligases (Kraft et al., 2005), suggesting a high specificity of E3 target recognition. Some of these E3s have been reported to regulate hormone signaling, plant immunity, and stress responses, but most of them are uncharacterized. It is important to identify their downstream signaling pathways and biological contributions. Within the E3 ligase superfamily, CRLs are important in plants because they are linked to hormonal signaling, developmental programs, and environmental responses (Joo et al., 2016, 2017; Yang et al., 2018). C3H4- and C3H2C3-type RF are the two canonical RING types. XB3 E3 ubiquitin ligases belong to the C3H4-type RFs, and they contain an ANK domain and a RF motif (Yuan et al., 2013). In plants, XB3 E3 ubiquitin ligases have been divided into three groups (Yuan et al., 2013), but only some of them have been studied. MjXB3 is highly expressed during flower senescence and regulates floral longevity in Petunia hybrida (Xu et al., 2007). XBAT35.2 localizes predominantly to the Golgi and is involved in cell death induction during the pathogen response (Liu et al., 2017). XBAT3 regulates lateral root development in Arabidopsis (Nodzon et al., 2004). In this study, we established that XBOS36 plays an important role in sporogenesis by mediating the degradation of MEL1. Unlike the typical endoplasmic reticulum (ER) localization of RING ligases (Metzger et al., 2012), XBOS36 localizes to both the cytoplasm and the nucleus, although it functions mainly in cytoplasm. Moreover, XBOS36 is a monocot-specific E3 ligase and is expressed universally in vegetative organs but is absent during early sporogenesis (Yuan et al., 2013; Figure 5A), which is opposite from the accumulation of MEL1, suggesting the functional specificity of XBOS36 for the regulation of MEL1 and sporogenesis. It will be interesting to analyze whether XBOS36 is similarly involved in the degradation of other meiosis-related proteins.

In summary, we elucidated the interplay between the ubiquitin-proteasome system and the phasiRNA regulatory machinery effector MEL1 in regulating sporogenesis in rice, providing the first report of a role for the newly identified E3 ubiquitin ligase XBOS36 in modulating the protein stability of the sRNA regulatory machinery. In the absence of MEL1 ubiquitination and degradation, the tetrad does not divide normally and the microspores exhibit a crescent shape, which results in partial sterile pollen grains. It might be noted that, even though MEL1 is germ specific, the phasiRNAs are not, and their effects on gene regulation may not be direct or cell-specific. The regulation of phasiRNAs from the tapetum and other cell types of the anther might also play a role in this process. Further molecular mechanism analysis showed that disturbing MEL1 homeostasis in germ cells affects the expression of multiple genes, possibly due to off-target cleavage of phasiRNA target genes. Our findings therefore provide insights into the communication between a monocot-specific E3 ligase and an AGO protein, which binds grass phasiRNAs during plant reproductive development.

Materials and methods

Plant growth conditions, generation of transgenic rice plants, and phenotype analysis

The growth conditions and generation of transgenic plants were conducted according to Zhang et al. (2013). The Zhonghua 11 (Oryza sativa japonica) rice cultivar was used for experiments. Rice plants were grown in a field in Guangzhou, China (23°08′ N, 113°18′ E), where the growing season extends from late April to late September. The mean minimum temperature range was 22.9°C–25.5°C, and the mean maximum temperature range was 29.7°C–32.9°C. The day length ranged from 12 to 13.5 h. Plants were cultivated using routine management practices.

The XBOS36 knockout mutants were generated using CRISPR-Cas9-based genome editing technology (Ma et al., 2015). The target sequence, TGGTGCACCGAGCCAGCCCG GGG, in the first exon of XBOS36 was used to construct the sgRNA expression cassette. Two homozygous mutants, xbos36 #1 (A base insertion between ORF 104-105, frameshift mutation) and xbos36 #2 (GC deletion at ORF 105–106, frameshift mutation), were obtained from T0 generations. The T2 and T3 generations of the transgenic plants were used for phenotypic analyses. Homozygous xbos36 plants without Cas9 T-DNA were obtained by PCR screening and further confirmed by hygromycin screening. The phenotypes in the T2 and T3 generations were stable.

OsMEL1 was overexpressed under the control of the CaMV35S promoter using a binary vector, pCAMBIA1300. The primers used for plant expression vector construction are listed in Supplemental Data Set 4. The transgenic rice plants were generated according to the Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation method (Toki et al., 2006). Briefly, embryonic calli were induced from rice seeds on N6 basal medium supplemented with 2mg/L 2,4-D. After cocultivation of the calli with Agrobacterium strain EHA105 that harbored the binary vector, the calli were transferred to selection medium supplemented with hygromycin. Hygromycin-resistant calli were subsequently used for shoot regeneration and root induction. The transgenic plantlets were then transferred to the field of the experimental station for normal growth and seed harvesting. Nearly 30 transgenic plants harboring pCAMBIA1300-OsMEL1 of the T0 generation were obtained and screened by RT-qPCR and immunoblotting, and three or more of these biologically independent transgenic plants were used for subsequent investigation. The T2 and T3 generations of the transgenic plants were used for phenotypic analyses. The phenotypes in the T2 and T3 generations were stable.

The phenotypes of anthers and pollen grains were analyzed at the heading stage. The phenotypes of plants, panicles, and rates of seed setting (the ratio of the number of filled grains to the total number of florets in a panicle) were determined when the seeds were harvested. For each line, data from 15 or more individual plants were obtained and statistically analyzed. Transgenic plants that were transformed with EV and WT plants were used as controls for the transgenic overexpressing plants. For CRISPR-Cas9 edited mutants, transgenic plants transformed with CRISPR-Cas9 vectors but that were not edited at the target sites, and WT plants were used as controls. Neither of these controls showed obvious differences from each other in either growth or seed-setting rate.

Plant material collection, RNA extraction, and whole-transcriptome sequencing

The spikelets from WT and OXMEL1 plants were collected at different developmental stages. Half of the spikelets were fixed and used for DAPI staining to analyze their developmental stage. The spikelets with the same anther length at the same developmental stage were collected and used for the immunoblot analysis and RNA-Seq in the study. Total RNA was extracted with RNAiso plus Reagent (Takara, Japan) for three biological replicates for each sample and was used for sequencing. Whole-transcriptome libraries were prepared, and deep sequencing was performed by the Biomarker Technologies. Libraries were controlled for quality and quantitated using the BioAnalyzer 2100 system and qPCR (Kapa Biosystems, Woburn, MA). The resulting libraries were sequenced initially on a HiSeq 2000 instrument that generated paired-end reads of 100 nt. The rice transcriptome was assembled using the Cufflinks 2.0 package according to the instructions provided (Trapnell et al., 2010). Briefly, each RNA-Seq dataset was aligned to the rice genome independently using the TopHat 2.0 program (Trapnell et al., 2012). The transcriptome from each dataset was then assembled independently using the Cufflinks 2.0 program. All transcriptomes were pooled and merged to generate a final transcriptome using Cuffmerge. After the final transcriptome was produced, Cuffdiff was used to estimate the abundance of all transcripts based on the final transcriptome, and a BAM file was generated from the TopHat alignment.

RT-qPCR analysis

Total RNA from rice spikelets at the PFS, PPS, PMDS, and EMS was extracted with RNAiso plus Reagent (Takara, Japan) and reverse-transcribed using the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara, Japan). RT-qPCR (reverse transcription quantitative PCR) was carried out using SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara, Japan). GAPDH was used as reference gene. The RT-qPCR was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Takara, Japan), and the resulting melting curves were visually inspected to ensure the specificity of the product detection. Gene expression was quantified using the comparative Ct method. Experiments were performed in triplicate, and the results are represented as the mean ± sd. The primers used in RT-qPCR analysis are listed in Supplemental Data Set 4.

Preparation of recombinant proteins

To prepare the recombinant proteins, several expression vectors were constructed. To construct the GST-XBOS36, GST-MEL1, GST-MEL1C, and GST-MEL1N plasmids, the fragments of XBOS36/MEL1/MEL1C/MEL1N were amplified from coding sequence (CDS) of XBOS36/MEL1 by primers (listed in Supplemental Data Set 4), respectively. These PCR products were inserted into pET-N-GST-Thrombin-C-His (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) by homologous recombination. To construct the XBOS36-FLAG and MEL1-HA plasmids, full-length CDS of XBOS36 and MEL1 was amplified by primers listed in Supplemental Data Set 4, respectively. These PCR products were inserted into pET-C-3xFLAG and pET-C-3xHA, respectively. These plasmids were introduced into E. coli strain Transetta (DE3), and E. coli cells were grown to an OD600 of approximately 0.6. Recombinant protein expression was then induced with 0.5 mM isopropyl-b-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) for 4 h at 28°C with gentle shaking. Cells were collected and lysed by ultrasonic cell crusher (VC131PB, SONICS, USA) and cleared by concentration (10,000g, 10 min, 4°C). Fusion proteins were purified using BeyoGold GST-tag Purification Resin (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

To construct the GST-MEL1-K1-4M (A452G, A467G, A560G, and A581G), GST-MEL1-K5M (A2771G), GST-MEL1-K1&2M (A452G and A467G), GST-MEL1-K3M (A560G), and GST-MEL1-K3&4M (A560G and A581G) plasmids, the mutated fragments of MEL1 were amplified from corresponding template vectors constructed using MutanBEST Kit (TaKaRa, Japan) according to the manufacturer’s protocols (primers are listed in Supplemental Data Set 4). These PCR products were inserted into pET-N-GST-Thrombin-C-His by homologous recombination method. All these five K to R-mutated versions of MEL1 proteins were prepared as indicated above.

IP–MS and pull-down assays

For in vivo IP–MS assays, crude plant proteins were extracted from WT (ZH11) panicles by IP buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 100 µM MG132, 1× protease inhibitor cocktail; P9599, Sigma), and cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 17,000g for 10 min at 4°C. For the MEL1 IP assay, 1-µg anti-MEL1 antibody (Komiya et al., 2014) was added to the crude extracts and incubated at 4°C with gentle agitation for 2 h, followed by incubation with A + G magnetic beads (ThermoFisher Scientific) for another 2 h. Magnetic beads were collected by magnetic frame, washed three times with IP buffer, and resuspended in SDS-PAGE loading buffer. MEL1 protein was analyzed by immunoblotting and HPLC–MS.

For in vitro pull-down assays, 1 μg of MEL1-HA was mixed with 1 μg of XBOS36-FLAG in IP buffer with 0.2% Triton X-100 and incubated at 4°C, with gentle agitation for 2 h, followed by another 2 h with additional 20 μL of resin. Resins were washed three times in IP buffer with 0.2% Triton X-100 and then eluted in sample buffer at 100°C for 5 min, followed by SDS-PAGE. Another RF E3 ubiquitin ligase SOR1, which has been validated to function as monomers (Chen et al., 2018), was used as a control. The proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG (AS15-3036, Sigma, 1:5,000 dilution) and anti-HA (C29F4, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:5,000 dilution) antibody.

Ubiquitination assays

For in vivo ubiquitination assays, plant total protein was extracted from WT panicles or protoplasts in IP buffer containing 0.5% Triton X-100. MEL1 proteins were then immunoprecipitated using anti-MEL1 antibody followed by incubation with A + G magnetic beads (ThermoFisher Scientific). The proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-MEL1 antibody, and the ubiquitination levels were detected using anti-ubiquitin (Cell Signaling Technology) antibodies.

In vitro ubiquitination assays were performed as described previously with slight modifications as follows (Chen et al., 2018). Briefly, each reaction was carried out in a 30 µL mixture containing 0.3-µg human E1 UBE1L2 (R&D Systems), 1 µg E2 UbcH5b/UBE2D2 (R&D Systems) or AtUBC8 (Zhao et al., 2013), 3 µg ubiquitin (R&D Systems), and 1 µg recombinant protein of interest and ubiquitination buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, PH 7.4, 2 mM ATP, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM DTT, 40 µM ZnSO4, and 0.2 U inorganic pyrophosphatase). The reaction mixes were incubated for 3 h at 30°C and stopped by addition of SDS-PAGE sample buffer (5× solution of 250 mM Tris–HCl, pH 6.8, 10% SDS, 30% (v/v) glycerol, 10 mM DTT, 0.05% (w/v) Bromophenol Blue). The samples were heated to 65°C for 10 min and then separated by electrophoresis on 7.5% SDS-PAGE gels, followed by immunoblotting using anti-ubiquitin (#3936, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:5,000 dilution; sc-8017, Santacruz, 1:5,000 dilution; 10201-2-AP, Proteintech, 1:5,000 dilution), anti-GST (HT601-01, TransGen Biotech, 1:5,000 dilution), and rabbit polyclonal anti-MEL1 antibodies (MEL1-C (GQAVAREGPVEVRQLPKC) were used to induce antibody production in rabbits as described previously (Komiya et al., 2014, 1:5,000 dilution for use).

Cell-free degradation assays

Cell-free degradation assays were carried out as described previously with little modifications (Kong et al., 2015). In brief, the total plant proteins were extracted from WT, OXMEL1, mel1-ko, and xbos36 panicles by native lysis buffer (25 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 10 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 4 mM PMSF, 5 mM DTT) and adjusted to equal quantity (∼200 µg). To test the stability of various proteins in vitro, crude plant protein extracts with the addition of 10-mM ATP mixed with ∼0.5 µg purified GST-MEL1, GST-MEL1C, GST-MEL1N, GST-MEL1-K1-4M, GST-MEL1-K5M, GST-MEL1-K1&2M, GST-MEL1-K3M, or GST-MEL1-K3&4M proteins in a total volume of 120 µL were divided into four equal parts, and incubated at 30°C for different times (0, 30, 60, and 90 min). The reaction was stopped by adding SDS-PAGE loading buffer (5× solution of 250 mM Tris·HCl, pH 6.8, 10% SDS, 30% (v/v) glycerol, 10 mM DTT, 0.05% (w/v) Bromophenol Blue) and heating for 10 min at 65°C. The levels of protein were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-GST (HT601-01, TransGen Biotech, 1:5,000 dilution) and anti-MEL1 (1:5,000 dilution) antibody. To test the effect of proteasome inhibitor on MEL1 stability in vivo, MG132 (50 µM) or DMSO (1%) was added directly to protein extracts from WT, OXMEL1 or xbos36 panicles at different developmental stages and incubated at 4°C or 25°C for different times as indicated. The proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-MEL1 antibody (1:5,000 dilution), as well as analyzed with anti-HSP90 (MBS853567, mybiosource, 1:5,000 dilution), anti-Tubulin (66031-1g, Proteintech, 1:5,000 dilution), or anti-OsGAPDH (AbP80006-A-SE, Beijing Protein Innovation, 1:10,000 dilution) as control.

Rice protoplast transient transformation, subcellular localization, and BiFC

The shoots of two-week-old rice plants were used for protoplast isolation. A bundle of rice plants (approximately 30 seedlings) was cut into approximately 0.5-mm strips using sharp razors. The strips were incubated in enzyme solution (1.5% cellulose RS, 0.75% macerozyme R-10, 0.6 M mannitol, 10 mM MES, pH 5.7, 10 mM CaCl2, and 0.1% BSA) for 4–5 h in the dark with gentle shaking (40–50 rpm). Following enzymatic digestion, an equal volume of W5 solution (154 mM NaCl, 125 mM CaCl2, 5 mM KCl, and 2 mM MES, pH 5.7) was added, and samples were shaken (60–80 rpm) for 30 min. Protoplasts were released by filtering through 40-μm nylon mesh into round-bottom tubes and were washed three to five times with W5 solution. The pellets were collected by centrifugation at 150g for 5 min in a swinging bucket at room temperature. After washing the pellets with W5 solution, the pellets were resuspended in MMG solution (0.4 M mannitol, 15 mM MgCl2, and 4 mM MES, pH 5.7) at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells mL−1. Aliquots of protoplasts (200 μL) were transferred into a 2-mL round-bottom microcentrifuge tube and mixed gently with plasmid DNA. In control (mock) transfections, equivalent volumes of deionized, sterile water were added. Transfected protoplasts were collected by centrifugation for 5 min at 100g at room temperature, resuspended, and then incubated at 28°C in the dark for 16 h. PEG-mediated transfections for subcellular localization and BiFC were performed as previously described (H. Zhang et al., 2011). For subcellular localization of XBOS36, PUB72, and C3H15, the full-length CDS of XBOS36, PUB72, and C3H15 was subcloned into the transient expression vector pRTVcGFP and pRTVnGFP (He et al., 2018), and coexpressed with ER-red fluorescent protein marker CD3-959 or the nucleus-mCherry marker HY5 (Nelson et al., 2007) in rice protoplasts. EV of pRTVcGFP and pRTVnGFP was used as control. To perform the BiFC assay of MEL1 and XBOS36, plasmids pUC-MEL1-YC and pUC-XBOS36-YN were constructed and coexpressed in rice protoplasts, and pUC-MET1A-YN was used as a control. Protoplasts were observed using a confocal laser-scanning microscope (Zeiss 7 DUO NLO) at 405-, 488- and 561-nm excitation. All manipulations described above were performed at room temperature. Over 40 protoplast cells were observed and over 90% of the observed cells showed the same results in the subcellular localization and BiFC experiments.

For the protein stability assays in protoplasts, 10-μg MEL1-HA plasmids were transfected with different amounts (0, 2, 4, and 8 μg) of ProUbi: XBOS36-GFP, EV, or SOR1-GFP plasmids. Transfected protoplasts were collected and lysed, and the proteins were extracted and detected by immunoblot assays. MEL1-HA protein was analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody anti-HA (C29F4, Cell Signaling Technology, 1:5,000 dilution), and the GFP-tagged proteins were detected by anti-GFP antibody (HT801-01, TransGen Biotech, 1:5,000 dilution).

Semi-thin sections and transmission electron microscopy

The anther development process has been divided into 12 stages as follows: stamen primordial stage (stage 1), archesporial cell differentiation stage (stage 2), primary parietal cell differentiation stage (stage 3), secondary parietal cell and primary sporogenous cell differentiation stage (stage 4), secondary sporogenous cell differentiation stage (stage 5), PMC differentiation stage (stage 6), premeiosis stage (stage 7), meiosis stage (stage 8), EMS (stage 9), late MS (stage 10), binucleate pollen stage (stage 11), and MPS (stage 12; D. Zhang et al., 2011). Anthers with different lengths were collected, squashed to release pollen cells by a needle, and observed using DAPI staining to monitor their developmental stages. Anthers of 0.9–1.6 mm in length are at stage 9, of 1.6–1.8 mm length are at stage 10, of 1.9–2.3 mm length are at stage 11, and of 2.3–2.9 mm length are at stage 12. The anther samples at different stages were fixed in 2.5% paraformaldehyde–3.0% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 mol/L PBS (pH 7.2) for 4 h at 4°C and then washed three times in the same buffer, which was followed by postfixation in 1% osmium tetroxide for 2 h at room temperature and 3 rinses using the same buffer. Specimens were dehydrated in a graded ethanol series (30% (v/v), 50% (v/v), 70% (v/v), 80% (v/v), 90% (v/v), and 100% (v/v), 30 min for each grade) and embedded in Epon812 (SPI Supplies Division of Structure Probe Inc., West Chester, PA, USA). Polymerization took place for 24 h at 40°C, followed by 24 h at 60°C. Specimens were cut to a thickness of 1 μm on a Leica RM2155 and were stained with 0.5% toluidine blue. Sections were observed and photographed with a Leica DMLB microscope. Ultrathin sections (50–70 nm) were double-stained with 2% (w/v) uranyl acetate and 2.6% (w/v) lead citrate aqueous solution and examined with a JEM 1400 transmission electron microscope (JEOL Ltd., Japan) at 120 kV.

Statistical analysis

The densitometric ratio of each band on immunoblots was recorded by ImageJ, with the relative abundance of control in each experiment was set to 1. Each experiment in this study was designed with at least three biological replicates (n ≥ 3), and data presented in this study are presented as means ± sd of three independent experiments unless otherwise indicated. The significance of the differences between groups was determined by a Student’s t test (Supplemental Data Set 5). P values < 0.01 (**) were considered significant.

Accession numbers

The sequencing data have been submitted to the NCBI SRA database (BioProject: PRJNA704501) and will be publicly available upon publication. Sequence data from this article can be found in the Rice Genome Annotation Project (RGAP) under the following accession numbers: LOC_Os03g58600.1 (MEL1), LOC_Os06g03800.1 (XBOS36), LOC_Os10g32880.1 (PUB72), LOC_Os02g19804.1 (C3H15), LOC_Os03g58400.1 (MET1A), and LOC_Os04g01160.1 (SOR1).

Supplemental data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1 . Expression pattern and interacting proteins of MEL1 (supports Figures 1–4).

Supplemental Figure S2 . Subcellular localization of E3 proteins and the mRNA levels of MEL1 in xbos36 plants (supports Figures 4, 5).

Supplemental Figure S3 . Sequence of MEL1 protein and the number of the downregulated genes in OXMEL1 and xbos36 plants (supports Figures 6, 7).

Supplemental Data Set 1 . Interacting proteins of MEL1 identified by IP–MS.

Supplemental Data Set 2 . Downregulated genes in OXMEL1 and xbos36.

Supplemental Data Set 3 . The enriched GO terms of the genes that both downregulated in the OXMEL1 and xbos36 lines.

Supplemental Data Set 4 . A list of primers.

Supplemental Data Set 5 . Details of Student’s t test for seed-setting rates and aberrant tetrad rates of OXMEL1 and xbos36 lines.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ms Huang Q.J. for technique support.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 91940301, 91640202, U1901202, 32070624 and 31770883), and grants from Guangdong Province (grant nos. 2019JC05N394 and 2019A1515011728), and China postdoc grand (grant no. 2018M643298).

Conflict of interest statement: None declared.

Contributor Information

Jian-Ping Lian, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Plant Resources, State Key Laboratory for Biocontrol, School of Life Science, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou 510275, PR China.

Yu-Wei Yang, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Plant Resources, State Key Laboratory for Biocontrol, School of Life Science, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou 510275, PR China.

Rui-Rui He, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Plant Resources, State Key Laboratory for Biocontrol, School of Life Science, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou 510275, PR China.

Lu Yang, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Plant Resources, State Key Laboratory for Biocontrol, School of Life Science, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou 510275, PR China.

Yan-Fei Zhou, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Plant Resources, State Key Laboratory for Biocontrol, School of Life Science, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou 510275, PR China.

Meng-Qi Lei, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Plant Resources, State Key Laboratory for Biocontrol, School of Life Science, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou 510275, PR China.

Zhi Zhang, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Plant Resources, State Key Laboratory for Biocontrol, School of Life Science, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou 510275, PR China.

Jia-Hui Huang, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Plant Resources, State Key Laboratory for Biocontrol, School of Life Science, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou 510275, PR China.

Yu Cheng, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Plant Resources, State Key Laboratory for Biocontrol, School of Life Science, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou 510275, PR China.

Yu-Wei Liu, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Plant Resources, State Key Laboratory for Biocontrol, School of Life Science, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou 510275, PR China.

Yu-Chan Zhang, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Plant Resources, State Key Laboratory for Biocontrol, School of Life Science, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou 510275, PR China.

Yue-Qin Chen, Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Plant Resources, State Key Laboratory for Biocontrol, School of Life Science, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou 510275, PR China; Guangdong Laboratory of Lingnan Modern Agriculture, Guangzhou 510642, PR China.

J.P.L. and Y.W.Y. carried out the experiments and drafted the manuscript. R.R.H., L.Y., Y.F.Z., M.Q.L., Z.Z., J.H.H., Y.C., and Y.W.L. carried out the mutant screening and functional experiments. Y.C.Z. and Y.Q.C. conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The authors responsible for distribution of materials integral to the findings presented in this article in accordance with the policy described in the Instructions for Authors (https://academic.oup.com/plcell) are: Yue-Qin Chen (lsscyq@mail.sysu.edu.cn) and Yu-Chan Zhang (zhyuchan@mail.sysu.edu.cn).

References

- Armstrong SJ, Caryl AP, Jones GH, Franklin FC (2002) Asy1, a protein required for meiotic chromosome synapsis, localizes to axis-associated chromatin in Arabidopsis and Brassica. J Cell Sci 115: 3645–3655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Chen H, Zhang Y, Thomas HR, Frank MH, He Y, Xia R (2020) TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol Plant 13: 1194–1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Ma B, Zhou Y, He SJ, Tang SY, Lu X, Xie Q, Chen SY, Zhang JS (2018) E3 ubiquitin ligase SOR1 regulates ethylene response in rice root by modulating stability of Aux/IAA protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115: 4513–4518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu MH, Chen IH, Baulcombe DC, Tsai CH (2010) The silencing suppressor P25 of Potato virus X interacts with Argonaute1 and mediates its degradation through the proteasome pathway. Mol Plant Pathol 11: 641–649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciechanover A, Orian A, Schwartz AL (2000) Ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis: biological regulation via destruction. Bioessays 22: 442–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Swetha C, Pachamuthu K, Nair A, Shivaprasad PV (2020) Loss of function of Oryza sativa Argonaute 18 induces male sterility and reduction in phased small RNAs. Plant Reprod 33: 59–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derrien B, Baumberger N, Schepetilnikov M, Viotti C, De Cillia J, Ziegler-Graff V, Isono E, Schumacher K, Genschik P (2012) Degradation of the antiviral component ARGONAUTE1 by the autophagy pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 15942–15946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei Q, Xia R, Meyers BC (2013) Phased, secondary, small interfering RNAs in posttranscriptional regulatory networks. Plant Cell 25: 2400–2415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez JF, Talle B, Wilson ZA (2015) Anther and pollen development: a conserved developmental pathway. J Integr Plant Biol 57: 876–891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grelon M, Vezon D, Gendrot G, Pelletier G (2001) AtSPO11-1 is necessary for efficient meiotic recombination in plants. The EMBO J 20: 589–600 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He F, Zhang F, Sun W, Ning Y, Wang GL (2018) A versatile vector toolkit for functional analysis of rice genes. Rice (N Y) 11: 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Liang W, Yin C, Cui X, Zong J, Wang X, Hu J, Zhang D (2011) Rice MADS3 regulates ROS homeostasis during late anther development. Plant Cell 23: 515–533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua Z, Vierstra RD (2011) The cullin-RING ubiquitin-protein ligases. Annu Rev Plant Biol 62: 299–334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang P, Lian B, Liu C, Fu Z, Shen Y, Cheng Z, Qi Y (2020) 21-nt phasiRNAs direct target mRNA cleavage in rice male germ cells. Nat Commun 11: 5191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston M, Geoffroy MC, Sobala A, Hay R, Hutvagner G (2010) HSP90 protein stabilizes unloaded argonaute complexes and microscopic P-bodies in human cells. Mol Biol Cell 21: 1462–1469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo H, Lim CW, Lee SC (2016) Identification and functional expression of the pepper RING type E3 ligase, CaDTR1, involved in drought stress tolerance via ABA-mediated signalling. Sci Rep 6: 30097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo H, Lim CW, Han SW, Lee SC (2017) The pepper RING finger E3 ligase, CaDIR1, regulates the drought stress response via ABA-mediated signaling. Front Plant Sci 8: 690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapoor M, Arora R, Lama T, Nijhawan A, Khurana JP, Tyagi AK, Kapoor S (2008) Genome-wide identification, organization and phylogenetic analysis of Dicer-like, Argonaute and RNA-dependent RNA Polymerase gene families and their expression analysis during reproductive development and stress in rice. BMC Genomics 9: 451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimyuk VI, Jones JD (1997) AtDMC1, the Arabidopsis homologue of the yeast DMC1 gene: characterization, transposon-induced allelic variation and meiosis-associated expression. Plant J 11: 1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komiya R, Ohyanagi H, Niihama M, Watanabe T, Nakano M, Kurata N, Nonomura K (2014) Rice germline-specific Argonaute MEL1 protein binds to phasiRNAs generated from more than 700 lincRNAs. Plant J 78: 385–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong L, Cheng J, Zhu Y, Ding Y, Meng J, Chen Z, Xie Q, Guo Y, Li J, Yang S, et al. (2015) Degradation of the ABA co-receptor ABI1 by PUB12/13 U-box E3 ligases. Nat Commun 6: 8630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft E, Stone SL, Ma L, Su N, Gao Y, Lau OS, Deng XW, Callis J (2005) Genome analysis and functional characterization of the E2 and RING-type E3 ligase ubiquitination enzymes of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 139: 1597–1611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Ravichandran S, Teh OK, McVey S, Lilley C, Teresinski HJ, Gonzalez-Ferrer C, Mullen RT, Hofius D, Prithiviraj B, et al. (2017) The RING-type E3 ligase XBAT35.2 is involved in cell death induction and pathogen response. Plant Physiol 175: 1469–1483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Teng C, Xia R, Meyers BC (2020) Phased secondary small interfering RNAs (phasiRNAs) in plants: their biogenesis, genic sources, and roles in stress responses, development, and reproduction. Plant Cell 32:3059–3080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J, Skibbe DS, Fernandes J, Walbot V (2008) Male reproductive development: gene expression profiling of maize anther and pollen ontogeny. Genome Biol 9: R181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Zhang Q, Zhu Q, Liu W, Chen Y, Qiu R, Wang B, Yang Z, Li H, Lin Y, et al. (2015) A robust CRISPR/Cas9 system for convenient, high-efficiency multiplex genome editing in monocot and dicot plants. Mol. Plant 8: 1274–1284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell GS, Philpott A (2016) New insights into the role of ubiquitylation of proteins. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 325: 35–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercier R, Mezard C, Jenczewski E, Macaisne N, Grelon M (2015) The molecular biology of meiosis in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 66: 297–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger MB, Hristova VA, Weissman AM (2012) HECT and RING finger families of E3 ubiquitin ligases at a glance. J Cell Sci 125: 531–537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay U, Chanda S, Patra U, Mukherjee A, Komoto S, Chawla-Sarkar M (2019) Biphasic regulation of RNA interference during rotavirus infection by modulation of Argonaute2. Cell Microbiol 21: e13101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson BK, Cai X, Nebenfuhr A (2007) A multicolored set of in vivo organelle markers for co-localization studies in Arabidopsis and other plants. Plant J 51: 1126–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nodzon LA, Xu WH, Wang Y, Pi LY, Chakrabarty PK, Song WY (2004) The ubiquitin ligase XBAT32 regulates lateral root development in Arabidopsis. Plant J 40: 996–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonomura K, Morohoshi A, Nakano M, Eiguchi M, Miyao A, Hirochika H, Kurata N (2007) A germ cell specific gene of the ARGONAUTE family is essential for the progression of premeiotic mitosis and meiosis during sporogenesis in rice. Plant Cell 19: 2583–2594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmedo-Monfil V, Duran-Figueroa N, Arteaga-Vazquez M, Demesa-Arevalo E, Autran D, Grimanelli D, Slotkin RK, Martienssen RA, Vielle-Calzada JP (2010) Control of female gamete formation by a small RNA pathway in Arabidopsis. Nature 464: 628–632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachamuthu K, Swetha C, Basu D, Das S, Singh I, Sundar VH, Sujith TN, Shivaprasad PV (2020) Rice-specific Argonaute 17 controls reproductive growth and yield-associated phenotypes. Plant Mol Biol 105: 99–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel P, Mathioni S, Kakrana A, Shatkay H, Meyers BC (2018) Reproductive phasiRNAs in grasses are compositionally distinct from other classes of small RNAs. New Phytol 220: 851–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petroski MD, Deshaies RJ (2005) Function and regulation of cullin-RING ubiquitin ligases. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6: 9–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radivojac P, Vacic V, Haynes C, Cocklin RR, Mohan A, Heyen JW, Goebl MG, Iakoucheva LM (2010) Identification, analysis, and prediction of protein ubiquitination sites. Proteins 78: 365–380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren Y, Chen D, Li W, Zhou D, Luo T, Yuan G, Zeng J, Cao Y, He Z, Zou T, et al. (2019) OsSHOC1 and OsPTD1 are essential for crossover formation during rice meiosis. Plant J 98: 315–328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadowski M, Suryadinata R, Tan AR, Roesley SN, Sarcevic B (2012) Protein monoubiquitination and polyubiquitination generate structural diversity to control distinct biological processes. IUBMB Life 64: 136–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao T, Tang D, Wang K, Wang M, Che L, Qin B, Yu H, Li M, Gu M, Cheng Z (2011) OsREC8 is essential for chromatid cohesion and metaphase I monopolar orientation in rice meiosis. Plant Physiol 156: 1386–1396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J, Tan H, Yu XH, Liu Y, Liang W, Ranathunge K, Franke RB, Schreiber L, Wang Y, Kai G, et al. (2011) Defective pollen wall is required for anther and microspore development in rice and encodes a fatty acyl carrier protein reductase. Plant Cell 23: 2225–2246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swatek KN, Komander D (2016) Ubiquitin modifications. Cell Res 26: 399–422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toki S, Hara N, Ono K, Onodera H, Tagiri A, Oka S, Tanaka H (2006) Early infection of scutellum tissue with Agrobacterium allows high-speed transformation of rice. Plant J 47: 969–976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, Salzberg SL, Wold BJ, Pachter L (2010) Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol 28: 511–515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Roberts A, Goff L, Pertea G, Kim D, Kelley DR, Pimentel H, Salzberg SL, Rinn JL, Pachter L (2012) Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat Protoc 7: 562–578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Le WD (2019) Autophagy and ubiquitin-proteasome system. Adv Exp Med Biol 1206: 527–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson ZA, Zhang DB (2009) From Arabidopsis to rice: pathways in pollen development. J Exp Bot 60: 1479–1492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Jiang CZ, Donnelly L, Reid MS (2007) Functional analysis of a RING domain ankyrin repeat protein that is highly expressed during flower senescence. J Exp Bot 58: 3623–3630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Wu L, Chang W, Li Z, Miao M, Li Y, Yang J, Liu Z, Tan J (2018) Overexpression of the maize E3 ubiquitin ligase gene ZmAIRP4 enhances drought stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol Biochem 123: 34–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Zhong J, Ouyang YD, Yao J (2013) The integrative expression and co-expression analysis of the AGO gene family in rice. Gene 528: 221–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan X, Zhang S, Liu S, Yu M, Su H, Shu H, Li X (2013) Global analysis of ankyrin repeat domain C3HC4-type RING finger gene family in plants. PLoS One 8: e58003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Luo X, Zhu L (2011) Cytological analysis and genetic control of rice anther development. J Genet Genomics 38: 379–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Xia R, Meyers BC, Walbot V (2015) Evolution, functions, and mysteries of plant ARGONAUTE proteins. Curr Opin Plant Biol 27: 84–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Su J, Duan S, Ao Y, Dai J, Liu J, Wang P, Li Y, Liu B, Feng D, et al. (2011) A highly efficient rice green tissue protoplast system for transient gene expression and studying light/chloroplast-related processes. Plant Methods 7: 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YC, Lei MQ, Zhou YF, Yang YW, Lian JP, Yu Y, Feng YZ, Zhou KR, He RR, He H, et al. (2020) Reproductive phasiRNAs regulate reprogramming of gene expression and meiotic progression in rice. Nat Commun 11: 6031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang YC, Yu Y, Wang CY, Li ZY, Liu Q, Xu J, Liao JY, Wang XJ, Qu LH, Chen F, et al. (2013) Overexpression of microRNA OsmiR397 improves rice yield by increasing grain size and promoting panicle branching. Nature Biotechnol 31: 848–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q, Tian M, Li Q, Cui F, Liu L, Yin B, Xie Q (2013) A plant-specific in vitro ubiquitination analysis system. Plant J 74: 524–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.