Abstract

Objective

To test the hypothesis that higher level of cognitive activity predicts older age at dementia onset in Alzheimer disease (AD) dementia.

Methods

As part of a longitudinal cohort study, 1,903 older persons without dementia at enrollment reported their frequency of participation in cognitively stimulating activities. They had annual clinical evaluations to diagnose dementia and AD, and the deceased underwent neuropathologic examination. In analyses, we assessed the relation of baseline cognitive activity to age at diagnosis of incident AD dementia and to postmortem markers of AD and other dementias.

Results

During a mean of 6.8 years of follow-up, 457 individuals were diagnosed with incident AD at a mean age of 88.6 (SD 6.4, range 64.1–106.5) years. In an extended accelerated failure time model, higher level of baseline cognitive activity (mean 3.2, SD 0.7) was associated with older age at AD dementia onset (estimate 0.026; 95% confidence interval 0.013–0.039). Low cognitive activity (score 2.1, 10th percentile) was associated with a mean onset age of 88.6 years compared to a mean onset age of 93.6 years associated with high cognitive activity (score 4.0, 90th percentile). Results were comparable in subsequent analyses that adjusted for potentially confounding factors. In 695 participants who died and underwent a neuropathologic examination, cognitive activity was unrelated to postmortem markers of AD and other dementias.

Conclusion

A cognitively active lifestyle in old age may delay the onset of dementia in AD by as much as 5 years.

Alzheimer disease (AD) and related disorders pose a substantial public health problem, particularly with the aging of populations around the world. In the absence of effective treatments, much of epidemiologic research has focused on identifying potentially modifiable risk factors for dementia. Among the most promising behavioral risk factors is participation in cognitively stimulating activities such as reading. In longitudinal studies, a higher level of cognitive activity participation has been associated with a lower risk of developing incident dementia1-9 and its primary clinical manifestation, accelerated cognitive decline.2,9,10 Cognitive activity does not appear to be related to the pathologies traditionally associated with dementia.9,11 Rather, it is hypothesized that cognitive activity enhances cognitive reserve, thereby delaying the cognitive symptoms of dementia-related pathologies.12-14 We are not aware of direct tests of this delaying hypothesis, although studies of education, an indicator of early-life cognitive activity, have provided little evidence of an association with delayed onset of dementia.15-19

In the present analyses, we test the hypothesis that a higher level of late-life cognitive activity is related to older age at onset of Alzheimer dementia. At study baseline, older persons without dementia rated their participation in cognitive activities. They subsequently had annual clinical evaluations to diagnose dementia and AD, and the deceased had a neuropathologic examination to quantify dementia-related neuropathologies. In those who developed AD, we used extended failure time models to test for the hypothesized association of cognitive activity with age at dementia onset. In decedents, we assessed the relation of cognitive activity to postmortem markers of AD and other dementias.

Methods

Participants

Analyses are based on older persons enrolled in the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP), a longitudinal study of aging and dementia.20 Participants are older persons from the Chicago metropolitan region who had not been diagnosed with dementia at the time of enrollment and agreed to annual clinical evaluations and a brain autopsy at death. At the time of these analyses, 2,206 individuals had completed the baseline evaluation. We excluded 137 people who met dementia criteria, leaving 2,069 individuals. There were 73 deaths before the first-year follow-up, and 18 people had been enrolled <1 year. Of the remaining 1,978 eligible for follow-up, 1,903 completed at least 1 follow-up evaluation (96.2%). They had a mean age at baseline of 79.7 (SD 7.5, range 53.3–100.5) years and had completed a mean of 15.0 (SD 3.3, range 0–30) years of formal education; 1,426 were women (74.9%), and 1,695 were White and of non-Latin descent (89.1%). They had a median of 1 of 7 chronic medical conditions (e.g., cancer, heart disease) and a median income between $35,000 and $49,999. They completed a mean of 7.4 annual clinical evaluations, 95.6% of possible evaluations in survivors.

At the time of these analyses, 941 of the core group of participants had died, and a brain autopsy had been performed in 794 (84.4%). A neuropathologic examination had been completed in 792 individuals. We excluded 97 persons with some missing neuropathologic data, leaving 695 persons with complete neuropathologic data. They were older at baseline than the 1,208 individuals without complete neuropathologic data (82.8 vs 77.9 years, t[1901] = 4.9, p < 0.001), less educated (14.7 vs 15.2 years, t[1901] = 3.2, p = 0.002), and more likely to be male (28.4% vs 23.2%, χ2[1] = 6.2, p = 0.013), but they did not differ in baseline level of cognitive activity (3.24 vs 3.19, t[1901] = 1.6, p = 0.103).

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

After discussion with study staff, participants signed informed consent forms. The study was approved by an institutional review board of Rush University Medical Center.

Assessment of Cognitive Activity

At baseline, participants rated frequency of participation in 7 specific activities on a 5-point scale. We focused on activities in which seeking or processing information was paramount and that had minimal physical, social, or economic barriers to participation. The 7 questions were as follows: “About how much time do you spend reading each day?” “In the last year, how often did you visit a library?” “Thinking of the last year, how often do you read newspapers?” “During the last year, how often did you read magazines?” “During the past year, how often did you read books?” “During the past year, how often did you write letters?” “During the past year, how often did you play games like checkers or other board games, cards, puzzles, etc?” For the first question, the response options were none (score = 1), <1 hour (score = 2), 1 to <2 hours (score = 3), 2 to <3 hours (score = 4), and ≥3 hours (score = 5). The response options for the remaining questions were once a year or less (score = 1), several times a year (score = 2), several times a month (score = 3), several times a week (score = 4), and every day/almost every day (score = 5).

A summary self-report measure of cognitive activity was formed by averaging the item scores, and this continuous measure was used in all analyses. In prior research, higher scores on this measure have been associated with lower risk of dementia and less rapid cognitive decline but not with the neurodegenerative and cerebrovascular pathologies traditionally associated with dementia.9,11

Participants also rated 30 questions about early-life cognitive activity on a 5-point scale.11 There were 11 questions about ages 6 to 12 years, 10 questions about age 18 years, and 9 questions about age 40 years. Item scores were averaged to yield a composite measure.

Other Covariates

Frequency of participation in social activity was assessed with 6 questions about the frequency of social behaviors such as visiting a relative or friend. The response options ranged from once a year or less (score = 1) to every day/almost every day (score = 5), with item scores averaged to yield a total score. Loneliness was assessed with a modified version21 of the de Jong–Gierveld22 Loneliness Scale. It included 5 items (e.g., I experience a general sense of emptiness, I miss having people around me) rated on a 5-point scale. Item scores were averaged to yield a total score that ranged from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating higher levels of loneliness. The social activity and loneliness measures have previously been associated with risk of developing AD.21

Clinical Classification of Dementia and AD

At baseline and annually thereafter, participants underwent a uniform structured clinical evaluation that included a medical history, neurologic examination, and administration of a battery of 19 cognitive tests. On the basis of this evaluation, an experienced clinician diagnosed dementia and AD using the guidelines of the joint working group of the National Institute of Neurologic and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCDS/ADRDA).23 The criteria require a history of cognitive decline and impairment in at least 2 cognitive domains, 1 of which must be memory to meet AD criteria. Persons who had impairment in at least 1 cognitive domain but did not meet criteria for dementia were classified as having mild cognitive impairment.20 To enhance uniformity in the implementation of the criteria across time and clinical decision-makers, we developed algorithms to convert cognitive scores into cognitive domain ratings and to convert cognitive domain ratings into ratings of the likelihood of dementia.24-26 An experienced clinician either agreed with the dementia algorithm or specified an alternative rating (and reasons for disagreeing with the algorithm) and rated the likelihood of specific causes of dementia.

Clinical decision-makers were blinded to the previously collected data.

Neuropathologic Examination

Examiners blinded to all clinical data followed a standard protocol for brain removal, tissue preservation and sectioning, and quantification of pathologic findings.27 The cerebral hemispheres were cut into slabs that were inspected for gross infarcts. Sections from 9 regions in 1 hemisphere were stained with hematoxylin & eosin and examined for microinfarcts. We quantified the percent area occupied by β-amyloid–immunoreactive plaques and the density of tau-immunoreactive tangles in 8 brain regions; regional values were averaged to yield composite amyloid and tau measures. A neuropathologic diagnosis of AD was based on the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease ratings of neuritic plaque density and the Braak score following the National Institute on Aging (NIA)–Reagan criteria.28 Lewy bodies were identified with a monoclonal phosphorylated antibody to α-synuclein in 6 brain regions; the presence of Lewy bodies in the midfrontal cortex, inferior parietal cortex, or middle temporal cortex was designated neocortical Lewy body disease. We used monoclonal antibodies to phosphorylated transactive response DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43) to rate TDP-43 cytoplasmic inclusions in 6 brain regions on a 4-point scale. Severe neuronal loss with gliosis in the subiculum or any hippocampal subfield was classified as hippocampal sclerosis.

Statistical Analysis

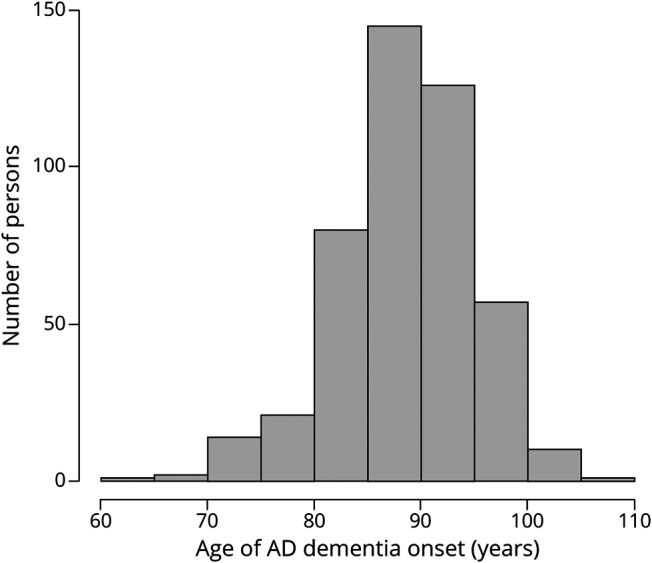

We used an extended accelerated failure time model29 to calculate mean ages at diagnoses. The extended accelerated failure time model takes the form

where  is the age at onset for the ith participant

is the age at onset for the ith participant and

and  are the mean and scale parameters of the ith participant, respectively; and

are the mean and scale parameters of the ith participant, respectively; and  is a standard baseline distribution. This model extends the classic accelerated failure time model by introducing a person-specific scale term. We assume

is a standard baseline distribution. This model extends the classic accelerated failure time model by introducing a person-specific scale term. We assume

and

and  , which ensures the positivity of

, which ensures the positivity of  as a scale term, where

as a scale term, where  is the vector of covariates of interest and other covariates to be controlled, if any. A positive entry in the vector

is the vector of covariates of interest and other covariates to be controlled, if any. A positive entry in the vector  indicates that increasing the corresponding covariate postpones the mean age at AD onset; a positive entry in the vector

indicates that increasing the corresponding covariate postpones the mean age at AD onset; a positive entry in the vector  indicates that increasing the corresponding covariate increases the spread (uncertainty) of age at AD onset across individuals. This extended accelerated failure time model fits the data better than the classic accelerated failure time model, which focuses only on the mean parameter

indicates that increasing the corresponding covariate increases the spread (uncertainty) of age at AD onset across individuals. This extended accelerated failure time model fits the data better than the classic accelerated failure time model, which focuses only on the mean parameter  while assuming

while assuming  as fixed across individuals. Given the model parameters, the mean age at onset for a given covariate

as fixed across individuals. Given the model parameters, the mean age at onset for a given covariate  can be calculated by

can be calculated by

|

On the basis of goodness-of-fit testing, we used a generalized gamma distribution30 for  , which includes Weibull, log-normal, and gamma distributions as special cases. With the use of age as the time scale here, participants enter the risk set at the age they completed their baseline evaluation given that they have survived to this age and have no dementia. Thus, we considered this left-truncation31 issue in all of the analyses.

, which includes Weibull, log-normal, and gamma distributions as special cases. With the use of age as the time scale here, participants enter the risk set at the age they completed their baseline evaluation given that they have survived to this age and have no dementia. Thus, we considered this left-truncation31 issue in all of the analyses.

The extended accelerated failure time models were fitted by R programs version 3.6.0 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria) with the flexsurv package.29 Data preprocessing and descriptive analysis were performed with SAS software, version 9.4 for Linux (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Statistical significance was determined at a level of 0.05.

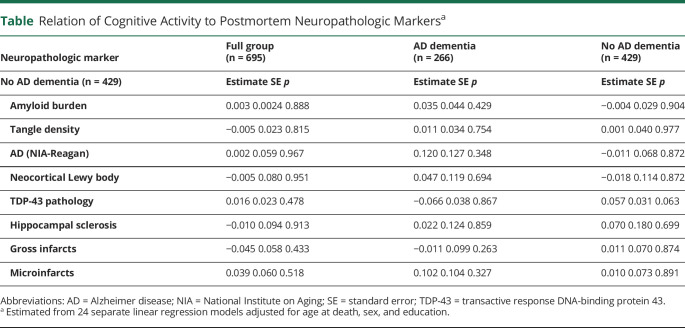

To determine whether cognitive activity was related to the neuropathologic conditions underlying dementia, we regressed the cognitive activity measure on each postmortem neuropathologic marker controlling for age at death, sex, and education. Initial analyses included the full neuropathologic group; analyses were repeated in subsets with and without dementia.

Data Availability

The data used in these analyses and a description of the parent study can be accessed at the Rush Alzheimer's Disease Center Research Resource Sharing Hub. After logging in, qualified users can request deidentified data.

Results

Cognitive Activity

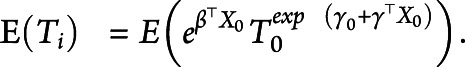

As shown in figure 1, the summary measure of baseline cognitive activity had an approximately normal distribution (mean 3.2, SD 0.7, range 1–5), with higher scores indicating more frequent participation in cognitively stimulating activities. Higher educational attainment was associated with a higher level of cognitive activity (r = 0.27, p < 0.001), but age at baseline (r = 0.02, p = 0.389), age at death (r = 0.02, p = 0.389), and male sex (3.16 vs 3.22, t[902.5] = 1.7, p = 0.087) were not.

Figure 1. Distribution of Cognitive Activity Scores.

Frequency histogram of baseline cognitive activity scores.

Incident Alzheimer Dementia

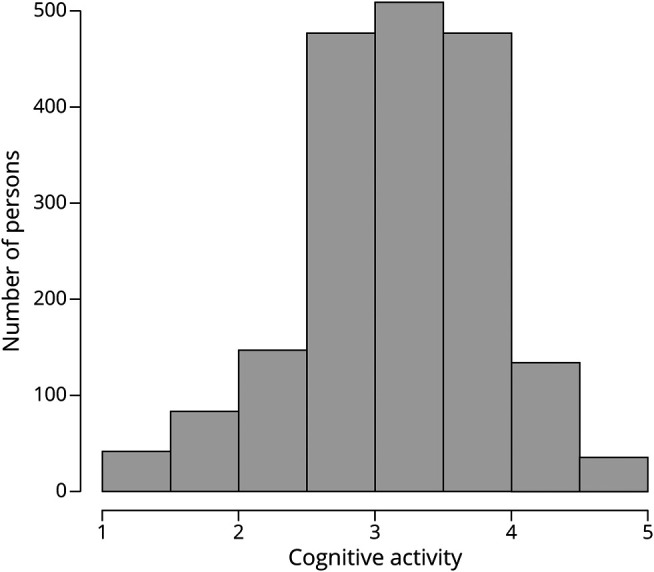

During a mean of 6.8 years of annual follow-up evaluations (SD 4.6, range 0.4–21.9 years), 457 individuals developed incident AD, including 424 who met NINCDS/ADRDA criteria for probable AD and 33 who met NINCDS/ADRDA criteria for possible AD. The 1,446 without AD included 46 persons diagnosed with other forms of dementia. As shown in figure 2, age at the diagnosis of AD dementia had an approximately normal distribution with a mean of 88.6 (SD 6.4, range 64.1–106.5) years. Those who developed AD were older at baseline (82.7 years vs 78.7 years, t[953.9] = 11.6, p < 0.001) and less educated (14.7 years vs 15.1 years, t[778.2] = 2.0, p = 0.042) than the 1,446 persons who remained free of AD.

Figure 2. Distribution of Age at Dementia Onset in Incident AD.

Frequency histogram of age at dementia onset in incident Alzheimer disease (AD).

Cognitive Activity and Age at AD Onset

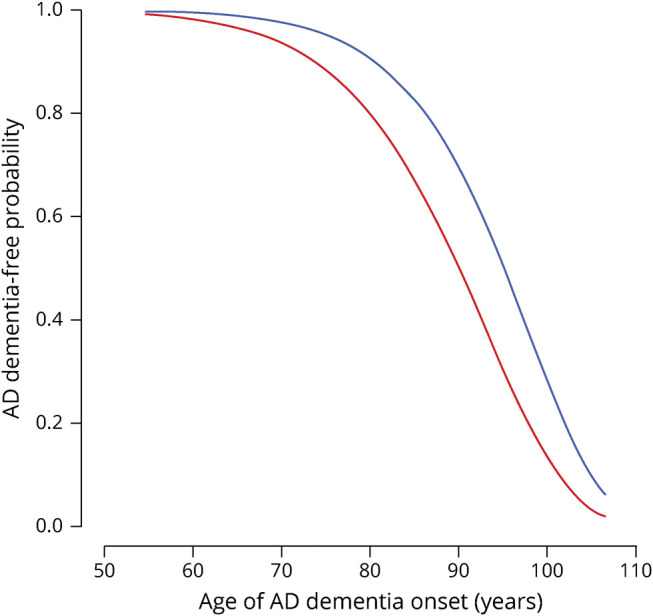

In the 457 persons who developed incident AD, we tested the hypothesis that a higher level of cognitive activity is associated with older age at dementia onset in AD. In a general accelerated failure time model, a higher level of cognitive activity was associated with older mean age at AD diagnosis (estimate 0.026, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.013, 0.039) but was not associated with the dispersion in age at AD diagnosis (estimate −0.127, 95% CI −0.279, 0.025). Figure 3, which is based on this analysis, shows the AD-free survival probabilities associated with different baseline levels of cognitive activity participation. We estimated that persons with a high level of cognitive activity participation (score 4.3, 90th percentile) developed AD at a mean age of 93.6 years compared to a mean onset age of 88.6 years in persons with a low level of cognitive activity participation (score 2.1, 10th percentile), a difference of 5 years.

Figure 3. Relation of Cognitive Activity to Age at Dementia Onset in Incident AD.

Relation of high (blue line, score = 4.3, 90th percentile) and low (red line, score = 2.1, 10th percentile) cognitive activity at baseline to probability of remaining dementia-free, from an extended accelerated failure time model. AD = Alzheimer disease.

Because education and sex have been associated with cognitive activity32 and AD,33,34 we constructed an additional accelerated failure time model that included terms for education and sex. In this analysis, the association of cognitive activity with the mean age at AD onset persisted (estimate 0.022; 95% CI 0.009, 0.035), and neither education (estimate 0.001, 95% CI −0.002, 0.004) nor sex (estimate −0.008, 95% CI −0.028, 0.013) was related to age at AD onset.

To determine whether cognitive activity before old age was related to AD dementia onset, we repeated the analysis with a term added for the frequency of early-life cognitive activity. In this analysis, there was no effect of early-life cognitive activity (estimate 0.011, 95% CI −0.006, 0.028), and the effect of cognitive activity at baseline remained (estimate 0.023, 95% CI 0.010, 0.037).

At baseline, 495 persons met the criteria for mild cognitive impairment. To assess whether results depended on this subgroup, we excluded them and repeated the initial analysis. The association of cognitive activity with age at AD onset persisted (estimate 0.014, 95% CI 0.002, 0.026). The association also persisted after we excluded those with possible AD (estimate 0.027, 95% CI 0.015, 0.040). Because social engagement has been related to dementia,21 we considered it a possible confounder of the association of cognitive activity with AD. Therefore, we repeated the initial model, first controlling for baseline frequency of social activity (mean 2.6, SD 0.6) and then again controlling for baseline loneliness (mean 2.2, SD 0.6). Cognitive activity continued to be related to age at AD dementia onset in both the first (estimate 0.020, 95% CI 0.007, 0.033) and second (estimate 0.036, 95% CI 0.020, 0.051) models. To see if the effect of cognitive activity depended on genetic predisposition to AD, we added a term for possession of an APOE ε4 allele (present in 23.1%). Cognitive activity continued to be associated with age at AD onset (estimate 0.028, 95% CI 0.016, 0.040).

Cognitive Activity and Postmortem Neuropathologies

Because the pathology of AD and other dementias accumulates years before dementia onset, it is possible that a low level of cognitive activity is an early sign of underlying disease rather than a true risk factor. To test this reverse-causality hypothesis, we focused on the 695 participants who died and underwent brain autopsy and neuropathologic examination. On examination of this subgroup, the mean (square root–transformed) amyloid burden was 1.66 (SD 1.19, range 0–4.73), the mean (square root–transformed) tangle density was 1.61 (SD 1.25, range: 0–6.99), and 63.6% met NIA-Reagan neuropathologic criteria for AD. Neocortical Lewy bodies were present in 14.1%; TDP-43 pathology was found in 52.4%; hippocampal sclerosis was seen in 9.6%; gross infarcts were found in 36.8%; and microinfarcts were present in 30.9%. We regressed the summary measure of baseline cognitive activity on each postmortem neuropathologic marker controlling for age at death, sex, and education. As shown in the table, cognitive activity was not related to any neuropathologic marker in the full group or in the subgroups with and without dementia.

Table.

Relation of Cognitive Activity to Postmortem Neuropathologic Markersa

Discussion

In this study, a group of >1,900 older persons without dementia at enrollment reported their frequency of participation in cognitively stimulating activities. They subsequently underwent annual dementia evaluations for up to 22 years, during which about one-quarter developed incident AD. Persons with a high level of premorbid cognitive activity were diagnosed with AD a mean of 5 years later than persons with a low premorbid level of cognitive activity. The results suggest that a cognitively active lifestyle has the potential to delay the onset of dementia in AD by several years.

Prior research in this9 and other1-8 cohorts has shown that a higher level of cognitive activity is associated with a lower subsequent risk of developing dementia. Although these studies have established an association between cognitive activity and risk of developing dementia, the strength of the association has remained uncertain. To confront this issue, the present study focused on incident AD dementia, used age at AD dementia onset as the outcome, and measured the extent to which differences in level of cognitive activity were associated with subsequent differences in age at AD dementia onset. The observation that individual differences in late-life cognitive activity are associated with such wide variability in AD dementia onset underscores the potential importance of a cognitively active lifestyle in reducing the impact of this disease.

Years of formal education is a marker of early-life cognitive activity that is widely used as an indicator of cognitive reserve. Several studies have tested the hypothesis that a higher level of educational attainment is associated with older age at dementia onset. Counterintuitively, however, these studies have generally found the opposite result, with a higher level of education associated with a younger age at dementia onset.15-18 One issue may be that education is not a very robust indicator of cognitive reserve.35 In addition, because these studies are based on prevalent dementia, age at dementia onset was estimated retrospectively from informant report and therefore subject to bias. After late-life level of cognitive activity was accounted for in the present analyses, neither education nor a composite measure of early-life cognitive activity was associated with age at incident AD dementia onset. These data suggest that the association of cognitive activity with age at AD dementia onset is driven mainly by late-life cognitive activity.

The bases of the observed association between cognitive activity and age at AD dementia onset are uncertain. One possibility is that low cognitive activity is an early sign of AD (reverse-causality hypothesis). In the present analyses, however, postmortem markers of AD and other dementias were unrelated to the self-report measure of cognitive activity, consistent with prior research in this cohort.9,11 In addition, although prior analyses have demonstrated cognitive activity decline in this cohort, cognitive function was not a predictor of subsequent cognitive activity.36 These observations provide no support for the reverse-causality hypothesis. We think a more likely possibility is that cognitive activities lead to changes in brain structure and function that enhance cognitive reserve. In previous analyses, the association of cognitive activity with cognitive function in this cohort was shown to be partly mediated by diffusion characteristics in the left cerebral hemisphere,37 and longitudinal studies have shown regional changes in gray matter volume and white matter microstructural integrity in persons engaged in cognitive activities such as studying for an examination,38 training to drive a taxi,39 and deciphering Morse code.40 Repeated cognitively stimulating behavior may enhance selected neural systems such that relatively more pathology is needed to impair function.

AD is thought to develop gradually over decades with an asymptomatic phase during which initial degenerative changes occur followed by a symptomatic phase consisting of mild cognitive and behavioral symptoms that progressively worsen and eventually result in dementia. Projections of the future prevalence and incidence of dementia in the United States41-43 and globally44,45 suggest that delaying dementia onset by as little as 1 or 2 years could have an enormous public health impact. A 5-year delay in AD onset has been estimated to reduce disease prevalence by 41% and costs by 40%.42 The cognitive activities assessed in this research involve information processing and present few physical or social barriers to participation, making them accessible to most older persons. The substantial association of cognitive activity with age at AD dementia onset in these analyses suggests that further research is needed into strategies to promote a cognitively active lifestyle in old age.

The strengths and limitations of these findings should be noted. The availability of annual diagnostic evaluations for up to 22 years with a high rate of follow-up participation enhanced our ability to identify incident dementia. Because analyses are based on incident rather than prevalent dementia, we were able to estimate age at dementia onset from prospective observation rather than from retrospective informant report, reducing a potential source of bias. Use of a previously established composite index of cognitive activity likely reduced measurement error. The main limitation is that analyses are based on a selected group of mainly White well-educated participants. Further research will be needed to establish whether the findings will generalize to more diverse cohorts with a wider range of age and cognitive experiences.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the Illinois residents who participated in the Rush MAP; Traci Colvin, MPH, and Tracey Nowakowski, MA, for coordination of data collection; and John Gibbons, MS, and Greg Klein, MS, for data management.

Glossary

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- CI

confidence interval

- MAP

Memory and Aging Project

- NIA

National Institute on Aging

- NINCDS/ADRDA

National Institute of Neurologic and Communicative Disorders and Stroke/Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association

- TDP-43

transactive response DNA-binding protein 43

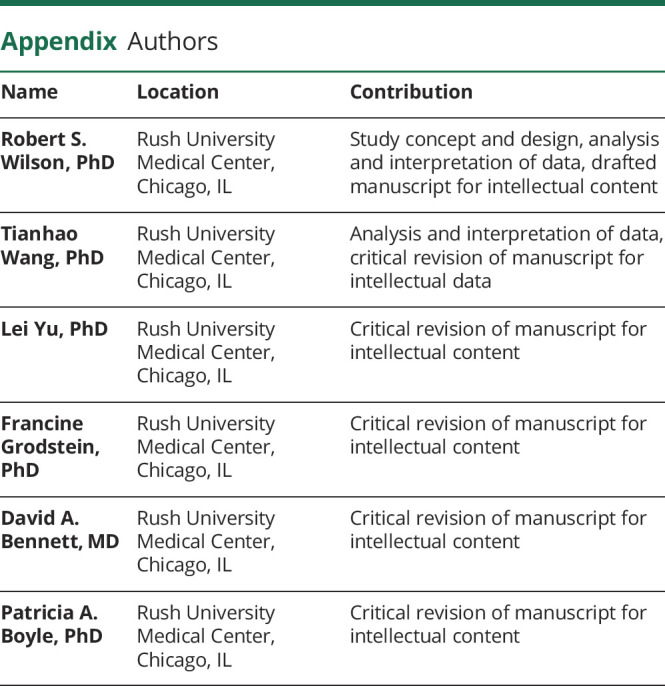

Appendix. Authors

Study Funding

This study was supported by NIA grants R01AG17917 and R01AG34374.

Disclosure

Robert S. Wilson, Tianhao Wang, Lei Yu, Fran Grodstein, David A. Bennett, and Patricia A. Boyle have no disclosures to report. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Scarmeas N, Levy G, Tng MX, Manly J, Stern Y. Influence of leisure activity on the incidnece of Alzheimer'sdisease. Neurology. 2001;57(12):2236-2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson RS, Mendes de Leon CF, Barnes LL, et al. Participation in cognitively stimulating activities and risk of incident Alzheimer's disease. JAMA. 2002;287(6):742-748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang HX, Karp A, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. Late-life engagement in social and leisure activities is associated with a decreased risk of dementia: a longitudinal study from the Kungsholmen project. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;155(12):1081-1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilson RS, Bennett DA, Bienias JL, et al. Cognitive activity and incidnet AD in a population-based sample of older persons. Neurology. 2002;59(12):1910-1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verghese J, Lipton RB, Katz MJ, et al. Leisure activities and the risk of dementia in the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(25):2508-2516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Karp A, Paillard-Borg S, Wang HX, Silverstein M, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. Mental, physical and social components in leisure activities contribute to decrease dementia risk. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;21(2):65-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hughes TF, Chang CC, Vander Bilt J, Ganguli M. Engagement in reading and hobbies and risk of incident dementia: the MoVies project. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2010;25(5):432-438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee ATC, Richards M, Chan WC, Chiu HFK, Lee RSY, Lam LCW. Association of daily intellectual activities with lower risk of incident dementia among older Chinese adults. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(7):697-703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wilson RS, Scherr PA, Schneider JA, Tang Y, Bennett DA. Relation of cognitive activity to risk of developing Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 2007;69(20):1911-1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hultsch DF, Hertzog C, Small BJ, Dixon RA. Use it or lose it: engaged lifestyle as a buffer against cognitive aging? Psychol Aging. 1999;14(2):245-263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson RS, Boyle PA, Yu L, Barnes LL, Schneider JA, Bennett DA. Life-span cognitive activity, neuropathologic burden, and cognitive aging. Neurology. 2013;81(4):314-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stern Y. Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer's disease. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(11):1006-1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park DC, Bischof GN. The aging mind: neuroplasticity in response to cognitive training. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2013;15(1):109-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gatz M, Prescott CA, Pedersen NL. Lifestyle risk and delaying factors. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2006;20(3 suppl 2):S84-S88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moritz DJ, Petitti DB. Association of education with reported age of onset and severity of Alzheimer's disease at presentation: implications for the use of clinical samples. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137(4):456-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bowler JV, Munoz DG, Merskey H, Hachinski V. Factors affecting the age of onset and rate of progression of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;65(2):184-190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Del Ser T, Hachinski V, Merskey H, Munoz DG. An autopsy-verified study of the effect of education on degenerative dementia. Brain. 1999;122(pt 12):2309-2319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roe CM, Xiong CX, Grant E, Miller JP, Morris JC. Education and reported onset of symptoms among individuals with Alzheimer's disease. Arch Neurol. 2008;65(1):108-111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lupton MK, Stahl D, Archer N, et al. Education, occupation and retirement age effects on the age of onset of Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;25(1):30-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bennett DA, Buchman AS, Boyle PA, Barnes LL, Schneider JA, Wilson RS. Religious Orders Study and Rush Memory and Aging Project. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;64(s1):S161-S189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wilson RS, Krueger KR, Arnold SE, et al. Loneliness and risk of Alzheimer's disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(2):234-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Jong-Gierveld J. Developing and testing a model of loneliness. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;53(1):119-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman M, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA work group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939-944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Schneider JA, et al. Natural history of mild cognitive impairment in older persons. Neurology. 2002;59(2):198-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bennett DA, Schneider JA, Aggarwal NT, et al. Decision rules guiding the clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease in two community-based cohort studies compared to standard practice in a clinic-based cohort study. Neuroepidemiology. 2006;27(3):169-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson RS, Boyle PA, Yang J, James BD, Bennett DA. Early life instruction in foreign language and music and incidence of mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychology. 2015;29(2):292-302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Leurgans SE, Bennett DA. The neuropathology of probable Alzheimer disease and mild cognitive impairment. Ann Neurol. 2009;66(2):200-208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Institute on Aging, and Reagan Institute Working Group on Diagnostic Criteria for the Neuropathological Assessment of Alzheimer's Disease. Consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18(4 suppl):S1-S2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jackson CH. Flexsurv: a platform for parametric survey modeling in R. J Stat Softw. 2016;70(8):i08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cox C, Chu H, Schneider MF, Munoz A. Parametric survival analysis and taxonomy of hazard functions for the generalized gamma distribution. Stat Med. 2007;26(23):4352-4374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lamarca R, Alonso J, Gomez G, Munoz A. Left-truncated data with age as time scale: an alternative for survival analysis in the elderly population. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1998;53(5):M337-M343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson RS, Bennett DA, Beckett LA, et al. Cognitive activity in older persons from a geographically defined population. J Gerontol Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1999;54(3):P155-P160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stern Y, Gurland B, Tatemichi TK, Tang MX, Wilder D, Mayeux R. Influence of education and occupation on the incidence of Alzheimer's disease. JAMA. 1994;271(13):1004-1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mazure CM, Swendsen J. Sex differences in Alzheimer's disease and other dementias. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(5):451-452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilson RS, Yu L, Lamar M, Schneider JA, Boyle PA, Bennett DA. Education and cognitive reserve in old age. Neurology. 2019;92(10):e1041-e1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilson RS, Segawa E, Boyle PA, Bennett DA. Influence of late-life cognitive activity on cognitive health. Neurology. 2012;78(15):1123-1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arfanakis K, Wilson RS, Barth CM, et al. Cognitive activity, cognitive function, and brain diffusion characteristics in old age. Brain Imaging Behave. 2016;10(2):455-463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Draganski B, Gaser C, Kempermann G, et al. Temporal and spatial dynamics of brain structure changes during extensive learning. J Neurosci. 2006;26(23):6314-6317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woollett K, Maguire EA. Acquiring “the knowledge” of London's layout drives structural brain changes. Curr Biol. 2011;21(24):2109-2114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schmidt-Wilcke T, Rosengarth K, Luerding R, Bogdahn U, Greenlee MW. Distinct patterns of functional and structural neuroplasticity associated with learning Morse code. Neuroimage. 2010;51(3):1234-1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brookmeyer R, Gray S, Kawas CH. Projections of Alzheimer's disease in the United States and the public health impact of delaying disease onset. Am J Public Health. 1998;88(9):137-1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zissimopoulos J, Crimmins E, Clair StP. The value of delaying Alzheimer's disease onset. Forum Health Econ Pol. 2014;18(1):25-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brookmeyer R, Abdalia N, Kawas CH, Corrada MM. Forecasting the prevalence of pre-clinical Alzheimer's disease in the United States. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2018;14(2):121-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brookmeyer R, Johnson E, Ziegler-Graham A, Arrighi HM. Forecasting the global burden of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3(3):186-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barnes DE, Yaffe K. The projected impact of risk factor reduction on Alzheimer's disease prevalence. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(9):819-828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in these analyses and a description of the parent study can be accessed at the Rush Alzheimer's Disease Center Research Resource Sharing Hub. After logging in, qualified users can request deidentified data.