Abstract

Background

Embryo transfer (ET) is a crucial step of in vitro fertilisation (IVF) treatment, and involves placing the embryo(s) in the woman’s uterus. There is a negative association between endometrial wave‐like activity (contractile activities) at the time of ET and clinical pregnancy, but no specific treatment is currently used in clinical practice to counteract their effects. Oxytocin is a hormone produced by the hypothalamus and released by the posterior pituitary. Its main role involves generating uterine contractions during and after childbirth. Atosiban is the best known oxytocin antagonist (and is also a vasopressin antagonist), and it is commonly used to delay premature labour by halting uterine contractions. Other oxytocin antagonists include barusiban, nolasiban, epelsiban, and retosiban. Administration of oxytocin antagonists around the time of ET has been proposed as a means to reduce uterine contractions that may interfere with embryo implantation. The intervention involves administering the medication before, during, or after the ET (or a combination).

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of oxytocin antagonists around the time of ET in women undergoing assisted reproduction.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility (CGF) Group trials register, CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and two trials registers in March 2021; and checked references and contacted study authors and experts in the field to identify additional studies.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of the use of oxytocin antagonists for women undergoing ET, compared with the non‐use of this intervention, the use of placebo, or the use of another similar drug.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures recommended by Cochrane. Primary review outcomes were live birth and miscarriage; secondary outcomes were clinical pregnancy and other adverse events.

Main results

We included nine studies (including one comprising three separate trials, 3733 women analysed in total) investigating the role of three different oxytocin antagonists administered intravenously (atosiban), subcutaneously (barusiban), or orally (nolasiban). We found very low‐ to high‐certainty evidence: the main limitations were serious risk of bias due to poor reporting of study methods, and serious or very serious imprecision.

Intravenous atosiban versus normal saline or no intervention

We are uncertain of the effect of intravenous atosiban on live birth rate (risk ratio (RR) 1.05, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.88 to 1.24; 1 RCT, N = 800; low‐certainty evidence). In a clinic with a live birth rate of 38% per cycle, the use of intravenous atosiban would be associated with a live birth rate ranging from 33.4% to 47.1%.

We are uncertain whether intravenous atosiban influences miscarriage rate (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.56; 5 RCTs, N = 1424; I² = 0%; very low‐certainty evidence). In a clinic with a miscarriage rate of 7.2% per cycle, the use of intravenous atosiban would be associated with a miscarriage rate ranging from 5.4% to 11.2%.

Intravenous atosiban may increase clinical pregnancy rate (RR 1.50, 95% CI 1.18 to 1.89; 7 RCTs, N = 1646; I² = 69%; low‐certainty evidence), and we are uncertain whether multiple or ectopic pregnancy and other complication rates were influenced by the use of intravenous atosiban (very low‐certainty evidence).

Subcutaneous barusiban versus placebo

One study investigated barusiban, but did not report on live birth or miscarriage.

We are uncertain whether subcutaneous barusiban influences clinical pregnancy rate (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.35; 1 RCT, N = 255; very low‐certainty evidence). Trialists reported more mild to moderate injection site reactions with barusiban than with placebo, but there was no difference in severe reactions. They reported no serious drug reactions; and comparable neonatal outcome between groups.

Oral nolasiban versus placebo

Nolasiban does not increase live birth rate (RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.28; 3 RCTs, N = 1832; I² = 0%; high‐certainty evidence). In a clinic with a live birth rate of 33% per cycle, the use of oral nolasiban would be associated with a live birth rate ranging from 32.7% to 42.2%.

We are uncertain of the effect of oral nolasiban on miscarriage rate (RR 1.45, 95% CI 0.73 to 2.88; 3 RCTs, N = 1832; I² = 0%; low‐certainty evidence). In a clinic with a miscarriage rate of 1.5% per cycle, the use of oral nolasiban would be associated with a miscarriage rate ranging from 1.1% to 4.3%.

Oral nolasiban improves clinical pregnancy rate (RR 1.15, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.30; 3 RCTs, N = 1832; I² = 0%; high‐certainty evidence), and probably does not increase multiple or ectopic pregnancy, or other complication rates (moderate‐certainty evidence).

Authors' conclusions

We are uncertain whether intravenous atosiban improves pregnancy outcomes for women undergoing assisted reproductive technology. This conclusion is based on currently available data from seven RCTs, which provided very low‐ to low‐certainty evidence across studies.

We could draw no clear conclusions about subcutaneous barusiban, based on limited data from one RCT.

Further large well‐designed RCTs reporting on live births and adverse clinical outcomes are still required to clarify the exact role of atosiban and barusiban before ET.

Oral nolasiban appears to improve clinical pregnancy rate but not live birth rate, with an uncertain effect on miscarriage and adverse events. This conclusion is based on a phased study comprising three trials that provided low‐ to high‐certainty evidence. Further large, well‐designed RCTs, reporting on live births and adverse clinical outcomes, should focus on identifying the subgroups of women who are likely to benefit from this intervention.

Plain language summary

Does using medication to block the hormone oxytocin help women who are undergoing embryo transfer for fertility treatment increase their chance of having a baby?

Review question

What are the benefits and risks of using medication to block the hormone oxytocin for women undergoing embryo transfer?

Background

Embryo transfer (ET) is a crucial step of assisted reproductive technology (ART), and involves placing one or more embryos (fertilised eggs) into the womb. Contractions in the lining of the womb are wave‐like motions of the lining surface; their presence around the time of embryo transfer is associated with lower pregnancy rates. No treatment is currently used to counteract their negative effects on the embryo’s attachment to the womb. Oxytocin is a natural hormone, known to trigger contractions during labour. Medication to block its function is routinely used to stop contractions in preterm labour. Some think the same hormone is involved in contractions around the time of ET. For this reason, researchers have questioned whether medication that stops labour contractions could stop contractions around the time of ET, and potentially improve pregnancy rates.

Study characteristics

We found eleven studies, in 3733 women undergoing embryo transfer, which assessed the use of medication to block oxytocin function. Medication to block oxytocin function was given by injection into a vein (atosiban) in seven RCTs, under the skin (barusiban) in one RCT, and by mouth (nolasiban) in three RCTs. The evidence is current to March 2021.

Key results

Medication by injection (atosiban) versus no medication

We are uncertain of the effect of atosiban on live birth and miscarriage rates. In a clinic with a live birth rate of 38% without medication to block oxytocin, the use of atosiban would be associated with a live birth rate ranging from 33% to 47%. In a clinic with a miscarriage rate of 7% without medication to block oxytocin, the use of atosiban would be associated with a miscarriage rate ranging from 5% to 11%.

Medication given under the skin (barusiban) versus no medication

There were no studies that reported live birth or miscarriage data for the use of barusiban. We are uncertain whether barusiban influences clinical pregnancy rates.

Medication given by mouth (nolasiban) versus no medication

The evidence suggests that nolasiban does not improve live birth rates when compared to those not taking medication to block oxytocin. In a clinic with a live birth rate of 33% per cycle without medication to block oxytocin, the use of nolasiban would be associated with a live birth rate ranging from 33% to 42%.

We are uncertain of the effect of oral nolasiban on miscarriage rate. In a clinic with a miscarriage rate of 2% per cycle without medication to block oxytocin, the use of nolasiban would be associated with a miscarriage rate ranging from 1% to 4%.

The evidence suggests that nolasiban improves clinical pregnancy rates compared to not taking medication to block oxytocin. In a clinic with a clinical pregnancy of 35% per cycle without medication to block oxytocin, the use of nolasiban would be associated with a clinical pregnancy rate ranging from 35% to 45%.

Evidence for all types of medication on other adverse events such as multiple pregnancy (pregnant with twins, triplets or more), pregnancy growing outside the womb, adverse reaction to medication or congenital anomalies (defects present from birth) was poorly reported or inconclusive.

Certainty of the evidence The evidence was of very low to high certainty. The main limitations in the evidence were poor reporting of study methods, and lack of exactness due to small study numbers and few events.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Oxytocin antagonists compared to control for assisted reproduction.

| Oxytocin antagonists compared to control for assisted reproduction | ||||||

| Patient or population: women undergoing embryo transfer as part of assisted reproduction Setting: assisted conception units Intervention: oxytocin antagonists Comparison: control (placebo or no intervention) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | ||

| Risk with control | Risk with oxytocin antagonists | |||||

| Live birth | IV atosiban | 380 per 1000 | 399 per 1000 (334 to 471) | RR 1.05 (0.88 to 1.24) | 800 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa |

| Oral nolasiban | 330 per 1000 | 373 per 1000 (327 to 422) | RR 1.13 (0.99 to 1.28) | 1832 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | |

| Miscarriage | IV atosiban | 72 per 1000 | 77 per 1000 (54 to 112) | RR 1.08 (0.75 to 1.56) | 1424 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowb,c |

| Oral nolasiban | 15 per 1000 | 22 per 1000 (11 to 43) | RR 1.45 (0.73 to 2.88) | 1832 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowd | |

| Clinical pregnancy | IV atosiban | 395 per 1000 | 592 per 1000 (466 to 746) | RR 1.50 (1.18 to 1.89) | 1646 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowb,e |

| SC barusiban | 352 per 1000 | 338 per 1000 (243 to 475) | RR 0.96 (0.69 to 1.35) | 255 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowf,g | |

| Oral nolasiban | 345 per 1000 | 397 per 1000 (352 to 448) | RR 1.15 (1.02 to 1.30) | 1832 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High | |

| Complications | IV atosiban |

Multiple pregnancy: 92/652 with atosiban vs 84/652 with saline or no intervention Ectopic pregnancy: 10/460 with atosiban vs 10/460 with saline or no intervention Adverse reactions: all 6 RCTs reported no difference between groups Congenital anomaly: 3 RCTs (N = 1184) reported no difference between groups |

1464 (6 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowh.i | ||

| SC barusiban | More mild to moderate injection site reactions observed with barusiban than with placebo; no difference in severe reactions reported; no serious drug reactions reported; neonatal outcome was comparable between groups | 255 (1 RCT) |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowh,i | |||

| Oral nolasiban |

Multiple pregnancy: 22/967 with nolasiban vs 8/865 with placebo Ectopic pregnancy: 6/967 with nolasiban vs 6/865 with placebo Headache: 23/967 with nolasiban vs 19/865 with placebo First trimester vaginal bleeding: 24/967 with nolasiban vs 31/865 with placebo Nausea: 16/967 with nolasiban vs 10 with placebo OHSS: 17/967 with nolasiban vs 13/865 with placebo Preterm delivery (< 37/40 weeks): 33/785 with nolasiban vs 27/800 with placebo Congenital anomaly: 17/967 with nolasiban vs 12/865 with placebo |

1832 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatej | |||

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the control group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; IV: intravenous; SC: subcutaneous; OHSS: ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. | ||||||

|

GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty. We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty. We are moderately confident in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty. Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited; the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty, We have very little confidence in the effect estimate; the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded two levels for very serious imprecision: data from a single study with only 311 events and a broad 95% CI that included both little harm or no effect and appreciable benefit. bDowngraded one level for serious risk of bias: majority of studies were at high or uncertain risk of bias in at least two domains. cDowngraded two levels for very serious imprecision: the total number of events was only 106 and the 95% CI was broad and included both appreciable harm and appreciable benefit. dDowngraded two levels for serious imprecision: the total number of events was only 38 and the 95% CI was broad and included both appreciable harm and appreciable benefit. eDowngraded one level for serious imprecision: there was a high variation in the point estimates of benefit between the pooled studies, which led to substantial heterogeneity. fDowngraded one level for serious risk of bias: data from a single study with unclear randomisation and concealment techniques. gDowngraded two levels for very serious imprecision: data from a single study with only 88 events and a broad 95% CI that included both appreciable harm and appreciable benefit. hDowngraded one level for serious risk of bias: the comparable rates of complications between the study groups were reported as text only, without absolute numbers or percentages. iDowngraded two levels for very serious imprecision: studies rarely reported on absolute numbers or percentages, and the number of events was very likely under 300 for every complication. jDowngraded two levels for serious imprecision: number of events was under 50 for every complication.

Background

Description of the condition

It is estimated that 15% of couples suffer from subfertility, defined as being unable to conceive following 12 months of regular unprotected sexual intercourse (Zegers‐Hochschild 2017). In vitro fertilisation (IVF) is a medical technique available to help couples suffering from subfertility achieve a pregnancy by obtaining embryos in the laboratory, using sperm and eggs from the couple, or from donors. To date, more than eight million babies born worldwide were conceived using IVF.

Embryo transfer (ET) is a crucial step in the IVF treatment, and involves placing the embryo(s) in the woman’s uterus following two to six days of development in the laboratory. A successful ET is achieved if one of the transferred embryos implants and grows into a full‐term healthy baby by the end of the pregnancy.

Fewer than one‐third of transferred embryos implant successfully following ET (Kupka 2014). Embryo implantation requires an optimal intrauterine environment that facilitates the interaction between the endometrium and a normal embryo. Several interventions have been attempted to improve the intrauterine environment. Pre‐ET (Glujovsky 2020), and post‐ET hormone preparation to thicken the endometrium and support implantation have shown certain efficiency (Van der Linden 2015). Endometrial injury (Lensen 2021), and intrauterine human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) administration to improve endometrial receptivity have shown uncertain efficiency (Craciunas 2018). Straightening the utero‐cervical angle to prevent uterine contractions triggered by trauma (Derks 2009), and the use of heparin and aspirin administration to improve endometrial perfusion have shown uncertain efficiency (Akhtar 2013). Removal of cervical mucus to prevent bacterial contamination (Craciunas 2014), or bed rest to prevent expulsion of embryos are not efficient (Craciunas 2016a).

Several studies have investigated the effect of uterine contractions on the content of the endometrial cavity. The radiopaque dye injected in the endometrial cavity during a mock ET was expelled in the fallopian tubes or down the cervical canal, by spontaneous contractions that occurred at the time of the mock ET, in more than one‐third of the participants (Knutzen 1992). The finding was confirmed by another study, when uterine contractions triggered by touching the uterine fundus expelled the transferred medium towards the fallopian tubes and cervix (Lesny 1998). Poorer IVF outcomes have been reported consistently in the presence of uterine contractions at the time of ET (Fanchin 1998; Zhu 2014). A systematic review assessing markers of endometrial receptivity reported a negative association between endometrial wave‐like activity at the time of ET and clinical pregnancy, but no specific treatment is currently used in clinical practice to counteract their effects (Craciunas 2019).

Description of the intervention

Oxytocin is a hormone produced by the hypothalamus, and released by the posterior pituitary. Its main role involves generating uterine contractions during and after childbirth. Oxytocin antagonists reduce oxytocin's effect by blocking its receptors. Atosiban is the best known oxytocin antagonist (and is also a vasopressin antagonist), and it is commonly used (licensed) to delay premature labour, by halting uterine contractions. Other oxytocin antagonists include barusiban, nolasiban, epelsiban, and retosiban.

Administration of oxytocin antagonists around the time of ET has been proposed as a means to reduce uterine contractions that may interfere with embryo implantation. The intervention involves administering the medication before, during, or after the ET, or a combination.

How the intervention might work

Uterine contraction patterns in IVF cycles are different from those in natural cycles. Ultrasound assessment of uterine contractions identified a delayed return to uterine quiescence following ovarian stimulation, with a higher level of contractions around the time of ET (Ayoubi 2003). In addition to the increased contraction frequency, the direction of contraction waves is different following ovarian stimulation, with more complex transverse and longitudinal waves present at the time of ET (Zhu 2012). These could displace the embryo from side to side, and prevent implantation in the endometrial cavity, which leads to either implantation failure or ectopic pregnancy.

Estradiol levels are 10 times higher in IVF cycles than in natural cycles, and uterine contractions are positively correlated with estradiol levels (Kunz 1998; Kunz 2006; Shukovski 1989). Furthermore, supraphysiological estradiol levels are associated with an increased expression of the oxytocin receptor in the non‐pregnant uterus (Richter 2004).

Oxytocin antagonists block oxytocin's effects, by binding to its receptor. The onset of uterine relaxation is rapid, and may facilitate successful embryo implantation (Vrachnis 2011). The expression of oxytocin receptors varies during the menstrual cycle (lower in follicular phase, higher in luteal phase), and is much lower in the non‐pregnant uterus compared to the pregnant uterus close to term (50‐fold to 100‐fold), suggesting that the dosage of oxytocin antagonist in the context of assisted reproduction may be different from that of preterm labour to achieve the same level of relaxation (Fuchs 1985). Administration of oral nolasiban to women undergoing a mock endometrial preparation similar to ET resulted in decreased uterine contractions, increased endometrial blood flow, and modulation of gene expression relevant for endometrial receptivity and implantation (Pohl 2020).

Why it is important to do this review

Subfertility affects a significant proportion of the general population, and many couples require assisted reproduction. Despite important advances in ovarian stimulation protocols and laboratory technology, the success rates of IVF treatments have remained relatively low over the last 20 years. Failed IVF cycles increase the frustration of couples and clinicians, while medical systems face increasing expense burdens.

Non‐randomised studies are consistent in their reports of improved outcomes following the use of oxytocin antagonists around the time of ET (Chou 2011; Decleer 2012; He 2016b; Lan 2012), but results from randomised studies remain inconsistent (He 2016a; Ng 2014).

Oxytocin antagonists are not used routinely in assisted reproduction. Therefore, there is an emerging need to summarise current information, and provide a clear view on the effectiveness and safety, to encourage or disprove their clinical application. In this Cochrane Review, authors systematically reviewed and synthesised the relevant evidence, and identified gaps or limitations in our current understanding. Assessment of the methodological quality of existing and ongoing trials may encourage the conduct of more studies on this topic.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of oxytocin antagonists around the time of embryo transfer, in women undergoing assisted reproduction.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Published and unpublished randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were eligible for inclusion, regardless of language or country of origin. We fully described the methods used to translate any non‐English studies. For cross‐over trials, we planned to include only data from the first phase in the meta‐analysis, as the cross‐over is not a valid design in the context of subfertility.

Types of participants

All women undergoing embryo transfer (ET) as part of their assisted reproduction treatment.

Types of interventions

Oxytocin antagonists around the time of ET, compared with any other active intervention, no intervention, or placebo.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

1. Live birth rate per woman or couple randomised (the delivery of a live foetus after 24 completed weeks of gestational age)

2. Miscarriage rate per woman or couple randomised (the loss of the pregnancy before 24 completed weeks of gestational age)

Secondary outcomes

3. Clinical pregnancy rate per woman or couple randomised (the presence of a gestational sac on ultrasound scan). Data were not limited to standard six‐ to eight‐week scans, and included reports of ongoing pregnancy up to 11 weeks of gestation.

4. Complication rate per woman or couple randomised, including ectopic pregnancy, preterm delivery (< 37 weeks gestation), abnormal placentation, intrauterine growth restriction, foetal abnormality, or other adverse events, reported as an overall complication rate, or as individual outcomes, or both (as reported by individual studies)

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched for all RCTs of oxytocin antagonists around the time of ET, in consultation with the Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group (CGF) Information Specialist.

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases:

The Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group's (CGFG) specialised register of controlled trials, ProCite platform, searched 15 March 2021 (Appendix 1);

CENTRAL via the Cochrane Central Register of Studies Online (CRSO), Web platform, searched 15 March 2021 (Appendix 2);

MEDLINE, Ovid platform, searched from 1946 to 15 March 2021 (Appendix 3);

Embase, Ovid platform, searched from 1980 to 15 March 2021 (Appendix 4);

PsycINFO, Ovid platform, searched from 1806 to 15 March 2021 (Appendix 5);

CINAHL Ebsco platform, searched from 1961 to 15 March 2021 (Appendix 6).

We combined the MEDLINE search with the Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy for identifying randomised trials, in Chapter 6.4.11 of the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Lefebvre 2011). We combined the Embase and CINAHL searches with trial filters developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN; www.sign.ac.uk/what-we-do/methodology/search-filters/). The PsycINFO search filter was developed by the Health Information Research Unit, McMaster University (hiru.mcmaster.ca/hiru/HIRU_Hedges_PsycINFO_Strategies.aspx).

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov); searched 15 March 2021, and the World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (www.who.int/trialsearch/Default.aspx); searched 15 March 2021, to identify ongoing and registered trials.

We also searched OpenGrey (www.opengrey.eu/) and Google Scholar (scholar.google.co.uk/) on 15 March 2021 for grey (i.e. unpublished) literature.

Searching other resources

We handsearched reference lists of articles retrieved by the searches, and contacted experts in the field to identify any additional trials.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

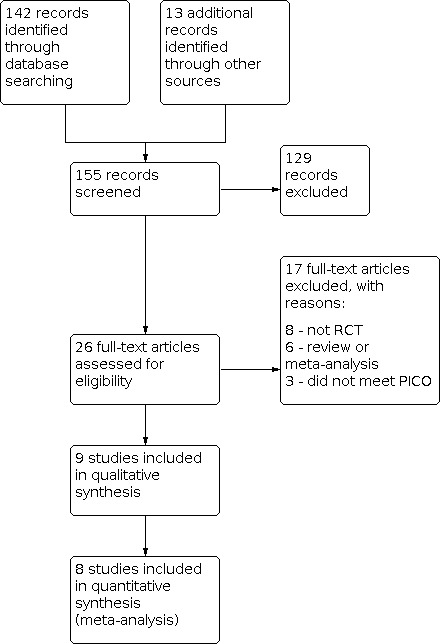

Two review authors (LC, NT) independently screened the title, abstract, and keywords for each publication retrieved by the search. Following the exclusion of reports that were irrelevant to the objectives of this review, the same two review authors retrieved the full text of the remaining publications, and independently appraised them to identify the RCTs suitable for inclusion. We resolved any disagreement related to study eligibility by discussion with a third review author (MK). We listed all studies excluded after full‐text assessment in the Characteristics of excluded studies tables, and documented the study selection process in a PRISMA flow chart (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (LC, NT) independently extracted data from eligible studies using a pre‐designed and pilot‐tested data extraction form. We collated data from studies with multiple publications, so that each study, rather than each report was the unit of interest in the review. We sought additional data by contacting study authors when published data were insufficient. We resolved any disagreement by involving a third review author (MK). One review author (LC) entered the data into Review Manager 5 (RevMan 2020), and a second (NT) checked them against the data extraction form.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (LC, NT) used the Cochrane RoB 1 assessment tool to independently assess the included studies for risk of bias domains: selection (random sequence generation and allocation concealment); performance (blinding of participants and personnel); detection (blinding of outcome assessors); attrition (incomplete outcome data); reporting (selective reporting); and other potential bias. A third review author (MK) was involved in case of disagreement. We explicitly reported our judgements of the risks of bias in the Characteristics of included studies table, providing relevant information to support our assessments.

We regarded lack of blinding of participants and personnel as giving rise to a high risk of bias across all outcomes. We planned to regard studies with more than 10% attrition as being at high risk of bias across all outcomes. We regarded studies without registered protocols as being at unclear risk of selection bias.

Measures of treatment effect

We expected all outcomes would be dichotomous. We calculated Mantel‐Haenszel risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), using the numbers of events in the intervention and control groups of each study. For outcomes with event rates below 1%, we planned to use the Peto one‐step odds ratio (OR) method to calculate the combined outcome with a 95% CI.

Unit of analysis issues

The primary analysis was by woman or couple randomised; we completed an additional analysis for miscarriage data by clinical pregnancy, in order to give the full picture of effects. We planned to briefly summarise data that did not allow valid analysis (by cycle data) in an additional table, and did not plan to meta‐analyse them. We counted multiple live births (twins or triplets) as one live‐birth event. We planned to include only first‐phase data from cross‐over trials.

Dealing with missing data

We attempted to contact study authors to obtain missing data in order to perform analyses on an intention‐to‐treat basis. In the case of unobtainable data, we planned to conduct imputation of individual values for the live‐birth rate only. We assumed that live births did not occur in women without a reported outcome. For other outcomes, we planned to analyse only the available data. We planned to subject any imputation we undertook to a sensitivity analysis.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We considered whether the clinical and methodological characteristics of the included studies were sufficiently similar for meta‐analysis to provide a clinically meaningful summary. We identified heterogeneity by visual inspection of the forest plots, and by using a standard Chi² test, with significance set at P < 0.1. We used the I² statistic to estimate the total variation across RCTs due to heterogeneity. An I² greater than 50% indicated substantial heterogeneity (Higgins 2003).

Assessment of reporting biases

We conducted a comprehensive search in order to minimise the potential impact of publication bias and other reporting biases. We planned to use a funnel plot to explore the possibility of small study effects when the number of included RCTs in an analysis exceeded 10.

Data synthesis

We combined the data from RCTs that compared similar treatments using a random‐effects model, as a degree of clinical heterogeneity is unavoidable (i.e. different ovarian stimulation protocols). In the forest plots, we displayed an increase in the odds of an outcome to the right of the centre axis, and a decrease in the odds of an outcome to the left of the centre axis. If there was problematic clinical, methodological, or statistical heterogeneity (I² > 75%), we did not combine data in a meta‐analysis. When data were incomplete, and could not be presented in the analyses, we reported available data in narrative form.

We organised the data on the basis of the main comparison (oxytocin antagonist versus placebo, or no intervention, or other active comparator), stratified by the type of oxytocin antagonist, without pooling stratified data.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

When data were available, we planned to conduct subgroup analyses to investigate the efficacy of oxytocin antagonists administration around the time of ET, depending on:

Timing of administration (pre‐ET, during ET, post‐ET, other);

Stage of the embryo at transfer (cleavage versus blastocyst);

Embryo processing (fresh versus frozen‐thawed).

If we detected substantial heterogeneity, we planned to explore possible explanations in sensitivity analyses. Factors to be considered included treatment indication (i.e. cause of subfertility), the age of the women, ovarian stimulation protocol (i.e. agonist, antagonist), oxytocin antagonist dose, mode of administration (bolus versus infusion) and route of administration (intravenous versus subcutaneous or oral), embryo quality, endometrial thickness, source of oocytes (i.e. donated, own), and ET difficulty.

We took any statistical heterogeneity into account when interpreting the results, especially if there was any variation in the direction of effect.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analysis for the primary outcomes to examine the stability and robustness of the results in relation to the following eligibility and analysis factors:

Restriction to RCTs without high risk of bias in any of the risk of bias domains;

Publication type (abstract versus full text);

The use of a fixed‐effect model;

Calculation of odds ratio;

Imputation of outcomes.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We prepared a summary of findings (SoF) table using GRADEpro GDT (GRADEpro GDT). This table evaluated the overall certainty of the body of evidence in the comparison of oxytocin antagonists versus placebo or no intervention for the review outcomes (live birth, miscarriage, clinical pregnancy, and complications), using GRADE criteria. Two review authors independently assessed the certainty of the evidence based on five GRADE factors: study limitations (i.e. risk of bias), consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias, using the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews of Interventions Chapter 12.2 (Schünemann 2011). We justified, documented, and incorporated our judgements about the certainty of the evidence (high, moderate, low, or very low) into the reporting of results for each outcome.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; and Characteristics of ongoing studies tables for details.

Results of the search

We performed the latest systematic search on 15 March 2021, and identified 155 publications (142 from databases, and 13 from other sources). See Figure 1 for detailed search results.

Included studies

All nine included studies were parallel‐arm randomised controlled trials (RCT). One study included a succession of three RCTs (Griesinger 2021).

Eight studies were published as full‐text articles (Ahn 2009; Griesinger 2021; He 2016a; Hebisha 2018; Moraloglu 2010; Ng 2014; Song 2013; Yuan 2019); and one study was published as an abstract (Bosch 2019).

Five studies did not report external funding (Ahn 2009; He 2016a; Hebisha 2018; Moraloglu 2010; Song 2013); four studies reported external funding (three commercial: Bosch 2019; Griesinger 2021; Ng 2014, and one national: Yuan 2019).

Participants

Participants were couples or women recruited before undergoing embryo transfer (ET) as part of assisted reproductive treatment for different subfertility causes. The total number of participants was 3733, and varied between 40 in Ahn 2009, and 1832 in Griesinger 2021.

Six studies were national, and were conducted in South Korea, China, Egypt, and Turkey (Ahn 2009; He 2016a; Hebisha 2018; Moraloglu 2010; Song 2013; Yuan 2019). Three studies were multinational (Bosch 2019 was conducted in Australia, Belgium, Canada, Czechia, Poland, and Spain; Griesinger 2021 was conducted in Belgium, Canada, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Hungary, Poland, Russia, and Spain; and Ng 2014 was conducted in China and Viernam).

Six studies included women undergoing fresh ET (Ahn 2009; Bosch 2019; Griesinger 2021; Hebisha 2018; Moraloglu 2010; Ng 2014); three studies included women undergoing frozen‐thawed ET in natural or medicated cycles (He 2016a; Song 2013; Yuan 2019).

Five studies included cleavage ETs (Ahn 2009; Moraloglu 2010; Ng 2014; Song 2013; Yuan 2019); two studies included blastocyst ETs (He 2016a; Hebisha 2018); and two studies included a mixture of cleavage and blastocyst ETs (Bosch 2019; Griesinger 2021).

Interventions

Seven studies compared the use of intravenous atosiban, with either normal saline as a placebo (Hebisha 2018; Moraloglu 2010; Ng 2014; Yuan 2019); or no intervention (Ahn 2009; He 2016a; Song 2013). Atosiban was administered as a single bolus dose ranging from 6.75 mg (He 2016a), to 7.5 mg (Hebisha 2018) prior to ET; or as a bolus of 6.75 mg prior to ET, followed by a continuous infusion up to 36.75 mg (Ahn 2009), or 37.5 mg before, during, and up to two hours after ET (Moraloglu 2010; Ng 2014; Song 2013; Yuan 2019).

One study compared the use of subcutaneous barusiban with placebo (Bosch 2019). The barusiban dose was 40 mg administered 45 minutes before ET, and 10 mg administered 15 minutes after ET.

One study compared the use of oral nolasiban with placebo (Griesinger 2021). The nolasiban dose ranged from 100 mg to 900 mg, and was administered four hours before ET.

Outcomes

Seven studies reported on at least one of our predefined primary outcomes. Live birth was reported by two studies (Griesinger 2021; Ng 2014); and miscarriage was reported by seven studies (Ahn 2009; Griesinger 2021; He 2016a; Moraloglu 2010; Ng 2014; Song 2013; Yuan 2019).

All nine studies reported on at least one of our predefined secondary outcomes. Clinical pregnancy was reported by all nine studies, but the timing of ultrasound diagnosis following ET varied: three weeks (Ahn 2009; Moraloglu 2010), four weeks (Hebisha 2018; Ng 2014; Song 2013; Yuan 2019), five weeks (He 2016a), six weeks (Griesinger 2021), and 10 to 11 weeks (Bosch 2019).

Ectopic pregnancy was reported by five studies (Ahn 2009; Griesinger 2021; Ng 2014; Song 2013; Yuan 2019), multiple pregnancy was reported by five studies (Griesinger 2021; He 2016a; Moraloglu 2010; Ng 2014; Yuan 2019), and adverse drug reactions were reported by eight studies (Ahn 2009; Bosch 2019; Griesinger 2021; He 2016a; Moraloglu 2010; Ng 2014; Song 2013; Yuan 2019).

Excluded studies

We excluded 17 studies because they were not a RCT (Angik 2018; Chou 2011; He 2016b; Kalmantis 2012; Lan 2012; Mishra 2018; Pierzynski 2007; Zhang 2014), they did not meet the PICO question (Pohl 2020; Visnova 2009; Visnova 2012), it was a review (Pierzynski 2011), or a meta‐analysis (Huang 2017; Kim 2014; Kim 2016; Li 2017; Schwarze 2020).

We did not identify any studies as awaiting classification, and we found five ongoing studies in trial databases (ChiCTR1900020795; ChiCTR‐OOR‐16008505; NCT01673399; NCT02893722; NCT03904745).

Risk of bias in included studies

Figure 2 shows the risk of bias graph, and Figure 3 shows the risk of bias summary. See the Characteristics of included studies table for rationales behind each judgement.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

Allocation

Sequence generation

All included studies were RCTs. The randomisation technique was adequate in three studies, which we classified at low risk of bias (Griesinger 2021; He 2016a; Ng 2014). Five studies lacked an adequate description of randomisation or a published protocol, and we classified them at unclear risk of bias (Ahn 2009; Bosch 2019; Hebisha 2018; Song 2013; Yuan 2019). One study described an inadequate randomisation technique, and we classified it at high risk of bias (Moraloglu 2010).

Allocation concealment

Three studies mentioned adequate allocation concealment, and we classified them at low risk of bias (Griesinger 2021; He 2016a; Ng 2014). Six studies lacked a description of methods of allocation concealment, and we classified them at unclear risk of bias (Ahn 2009; Bosch 2019; Hebisha 2018; Moraloglu 2010; Song 2013; Yuan 2019).

Blinding

Five studies documented blinding of participants or personnel (or both), and we classified them at low risk of bias (Bosch 2019; Griesinger 2021; He 2016a; Ng 2014; Yuan 2019). We classified the remaining studies at high risk of detection bias (Ahn 2009; Hebisha 2018; Moraloglu 2010; Song 2013).

The outcome measurement was not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; hence, we classified all studies at low risk of detection bias.

Incomplete outcome data

Seven studies followed up all participants, and reported the results adequately (Ahn 2009; Griesinger 2021; He 2016a; Hebisha 2018; Ng 2014; Song 2013; Yuan 2019). We classified these studies at low risk of bias. One study published as an abstract reported percentages, with no absolute numbers for the outcomes; we classified it at unclear risk of bias (Bosch 2019). One study excluded participants following randomisation due to difficult embryo transfer, and we classified it at unclear risk of bias (Moraloglu 2010).

Selective reporting

One study did not report on any negative outcomes (miscarriage or adverse events) and we classified it at unclear risk of bias (Hebisha 2018). The remaining studies reported on both positive and negative outcomes, and we classified them at low risk of bias.

Other potential sources of bias

We did not identify other sources of bias for the included studies.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

See: Table 1.

Primary outcomes

Live birth

One study of intravenous atosiban (Ng 2014), and one study of oral nolasiban (Griesinger 2021) reported on live birth.

Intravenous atosiban versus control (normal saline)

We are uncertain of the effect of intravenous atosiban on live birth rate compared to normal saline (RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.24; 1 RCT, N = 800; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.1; Figure 4). In a clinic with a live birth rate of 38% per cycle, the use of intravenous atosiban would be associated with a live birth rate ranging from 33.4% to 47.1%.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Oxytocin antagonists vs control, Outcome 1: Live birth

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Oxytocin antagonists vs control, outcome: 1.1 Live birth.

Oral nolasiban versus control (placebo)

Nolasiban likely does not increase live birth rate more than placebo (RR 1.13, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.28, 3 RCTs, N = 1832; I² = 0%; high‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.1; Figure 4). In a clinic with a live birth rate of 33% per cycle, the use of oral nolasiban would be associated with a live birth rate ranging from 32.7% to 42.2%.

Subgroup analyses

We were unable to complete subgroup analyses for intravenous atosiban based on timing of administration, stage of the embryo at transfer, and embryo processing, due to insufficient data.

timing of administration: all three studies included in Griesinger 2021 administered nolasiban four hours before fresh ET, therefore, there was no need for subgroup analysis.

-

stage of embryo:

Cleavage stage ET: oral nolasiban probably does not increase live birth rate (RR 1.21, 95% CI 0.92 to 1.59; 2 RCTs, N = 635; I² = 0%; moderate‐certainty evidence).

Blastocyst stage ET: oral nolasiban probably does not increase live birth rate (RR 1.15, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.52; 2 RCTs, N = 1197; I² = 72%; moderate‐certainty evidence).

Sensitivity analyses

Neither of the studies was at high risk of bias in one or more domains, therefore, there was no need for the prespecified sensitivity analysis for risk of bias.

Both studies were available in full text, therefore, there was no need for the prespecified sensitivity analysis for publication status.

There was only one RCT of intravenous atosiban, therefore, there was no need to re‐analyse using a fixed‐effect model. Results remained the same when we used a fixed‐effect model to meta‐analysis data from RCTs investigating oral nolasiban (RR 1.13, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.29; 3 RCTs, N = 1832; I² = 0%; high‐certainty evidence).

Results were similar when we calculated OR instead of RR for intravenous atosiban (OR 1.08, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.43; 1 RCT, N = 800; low‐certainty evidence); and oral nolasiban (OR 1.21, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.48; 3 RCTs, N = 1832; I² = 0%; high‐certainty evidence).

Miscarriage

Six studies of intravenous atosiban versus normal saline or no intervention (Ahn 2009; He 2016a; Moraloglu 2010; Ng 2014; Song 2013; Yuan 2019), and one study of oral nolasiban versus placebo (Griesinger 2021), reported on miscarriage.

Intravenous atosiban versus control (normal saline or no intervention)

We are uncertain whether intravenous atosiban influences miscarriage rate (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.56; 5 RCTs, N = 1424; I² = 0%; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.2; Figure 5). One study reported there was no difference in miscarriage rate between the intravenous atosiban and no intervention groups, but reported no numerical data that we could include in a meta‐analysis. In a clinic with a miscarriage rate of 7.2% per cycle, the use of intravenous atosiban would be associated with a miscarriage rate ranging from 5.4% to 11.2%.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Oxytocin antagonists vs control, Outcome 2: Miscarriage

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Oxytocin antagonists vs control, outcome: 1.2 Miscarriage.

Oral nolasiban versus control (placebo)

We are uncertain of the effect of oral nolasiban on miscarriage rate (RR 1.45, 95% CI 0.73 to 2.88; 3 RCTs, N = 1832; I² = 0%; low‐certainty evidence). In a clinic with a miscarriage rate of 1.5% per cycle, the use of oral nolasiban would be associated with a miscarriage rate ranging from 1.1% to 4.3%.

Subgroup analyses

-

Timing of administration:

Similar results were obtained for intravenous atosiban administered as a bolus before ET (RR 1.50, 95% CI 0.26 to 8.66; 1 RCT, N = 120; very low‐certainty evidence), or as a bolus before ET followed by infusion before, during, and after ET (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.53 to 2.23; 3 RCTs, N = 504; I² = 0%; very low‐certainty evidence).

Oral nolasiban was always administered four hours before ET, therefore, there was no need for subgroup analysis.

-

Stage of the embryo at transfer:

Similar results were obtained for intravenous atosiban administered for cleavage stage ET (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.55; 4 RCTs, N = 1304; I² = 0%; very low‐certainty evidence), and for blastocyst ET (RR 1.50, 95% CI 0.26 to 8.66; 1 RCT, N = 120; very low‐certainty evidence).

Similar results were obtained for oral nolasiban administered for cleavage stage ET (RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.30 to 4.64; 2 RCTs, N = 635; I² = 0%; low‐certainty evidence), and for blastocyst ET (RR 1.56, 95% CI 0.67 to 3.63; 2 RCTs, N = 1197; I² = 0%; low‐certainty evidence).

-

Embryo processing

Similar results were obtained for intravenous atosiban administered for fresh ET (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.61; 2 RCTs, N = 980; I² = 0%; very low‐certainty evidence), and for frozen‐thawed ET (RR 1.11, 95% CI 0.47 to 2.64; 3 RCTs, N = 444; I² = 0%; very low‐certainty evidence).

All three RCTs investigating oral nolasiban included fresh ET, therefore, there was no need for subgroup analysis.

Sensitivity analyses

Similar results were obtained after removing RCTs at high risk of bias in one or more domains for intravenous atosiban (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.75 to 5.16; 3 RCTs, N = 1124; I² = 0%; very low‐certainty evidence). None of the RCTs investigating oral nolasiban were at high risk of bias in one or more domains, therefore, there was no need for the prespecifieda sensitivity analysis for risk of bias.

All studies were available in full text, therefore, there was no need for the prespecified sensitivity analysis for publication status.

Results were similar with the fixed‐effect model compared to the random‐effects model for intravenous atosiban (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.55; 5 RCTs, N = 1424; I² = 0%; very low‐certainty evidence), and oral nolasiban (RR 1.50, 95% CI 0.79 to 2.84; 3 RCTs, N = 1832; I² = 0%; low‐certainty evidence).

Results were similar when OR was used instead of RR for intravenous atosiban (OR 1.09, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.62; 5 RCTs, N = 1424; I² = 0%; very low‐certainty evidence), and oral nolasiban (OR 1.47, 95% CI 0.73 to 2.97; 3 RCTs, N = 1832; I² = 0%; low‐certainty evidence).

Secondary analysis of miscarriage per clinical pregnancy

We are uncertain whether intravenous atosiban influences miscarriage per clinical pregnancy rate (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.60 to 1.20; 5 RCTs, N = 637; I² = 0%; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.3; Figure 6).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Oxytocin antagonists vs control, Outcome 3: Miscarriage per clinical pregnancy

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Oxytocin antagonists vs control, outcome: 1.3 Miscarriage per clinical pregnancy.

We are uncertain of the effect of oral nolasiban on miscarriage per clinical pregnancy rate (RR 1.17, 95% CI 0.56 to 2.46; 3 RCTs, N = 1832; I² = 12%; low‐certainty evidence).

Secondary outcomes

Clinical pregnancy

Seven studies of intravenous atosiban (Ahn 2009; He 2016a; Hebisha 2018; Moraloglu 2010; Ng 2014; Song 2013; Yuan 2019), one study of subcutaneous barusiban (Bosch 2019), and one study of oral nolasiban (Griesinger 2021), reported on clinical pregnancy.

Intravenous atosiban versus control (normal saline or no intervention)

Intravenous atosiban may increase clinical pregnancy rate (RR 1.50, 95% CI 1.18 to 1.89; 7 RCTs, N = 1646; I² = 69%; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.4; Figure 7). We explored potential sources of heterogeneity (embryo stage at transfer, embryo processing, atosiban dose, type and date of publication) but we could not identify a plausible source. Data were insufficient to perform other pre‐specified sensitivity analyses; therefore, the substantial heterogeneity remained unexplained.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Oxytocin antagonists vs control, Outcome 4: Clinical pregnancy

7.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Oxytocin antagonists vs control, outcome: 1.4 Clinical pregnancy.

Subcutaneous barusiban versus control (placebo)

We are uncertain whether subcutaneous barusiban influences clinical pregnancy rate (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.35; 1 RCT, N = 255; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.4; Figure 7).

Oral nolasiban versus control (placebo)

Oral nolasiban improves clinical pregnancy rate (RR 1.15, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.30; 3 RCTs, N = 1832; I² = 0%; high‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.4; Figure 7).

Complications

Multiple pregnancy

Four studies of intravenous atosiban (He 2016a; Moraloglu 2010; Ng 2014; Yuan 2019), and one study of oral nolasiban (Griesinger 2021) reported on multiple pregnancy.

Intravenous atosiban versus control (normal saline or no intervention)

We are uncertain of the effect of intravenous atosiban on the rate of multiple pregnancy (RR 1.12, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.55; 4 RCTs, N = 1304; I² = 7%; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.5; Figure 8).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Oxytocin antagonists vs control, Outcome 5: Complications

8.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Oxytocin antagonists vs control, outcome: 1.5 Complications.

Oral nolasiban versus control (placebo)

We are uncertain of the effect of oral nolasiban on the rate of multiple pregnancy (RR 1.46, 95% CI 0.64 to 3.32; 3 RCTs, N = 1832; I² = 0%; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.5; Figure 8).

Ectopic pregnancy

Four studies of intravenous atosiban (Ahn 2009; Ng 2014; Song 2013; Yuan 2019), and one study of oral nolasiban (Griesinger 2021), reported on ectopic pregnancy.

Intravenous atosiban versus control (normal saline or no intervention)

We are uncertain whether intravenous atosiban influences the rate of ectopic pregnancy (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.42 to 2.31; 2 RCTs, N = 920; I² = 0%; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.5; Figure 8). Ahn 2009 reported no difference in ectopic pregnancy rates, and Yuan 2019 reported no ectopic pregnancies in either group.

Oral nolasiban versus control (placebo)

We are uncertain of the effect of oral nolasiban on the rate of ectopic pregnancy (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.19 to 3.45; 3 RCTs, N = 1832; I² = 18%; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.5; Figure 8).

Adverse reactions

Six studies of intravenous atosiban (Ahn 2009; He 2016a; Moraloglu 2010; Ng 2014; Song 2013; Yuan 2019), one study of subcutaneous barusiban (Bosch 2019), and one study of oral nolasiban (Griesinger 2021), reported on adverse reactions. Data were insufficient for meta‐analysis; we counted events for each group when numerical data were available.

Intravenous atosiban versus control (normal saline or no intervention)

All six studies (N = 1464) reported there was no difference in the rate of adverse reactions between groups (very low‐certainty evidence).

Subcutaneous barusiban versus control (placebo)

One study (N = 255) reported there was no difference in the rate of serious adverse reactions between groups, but there were more mild and moderate adverse reactions at the injection site in the subcutaneous barusiban group compared to the control group (very low‐certainty evidence).

Oral nolasiban versus control (placebo)

One study (N = 1832) reported there was no difference in the rate of adverse reactions between groups (moderate‐certainty evidence).

Headache: 23/967 with nolasiban versus 19/865 with placebo

First trimester vaginal bleeding: 24/967 with nolasiban versus 31/865 with placebo

Nausea: 16/967 with nolasiban versus 10 with placebo

Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: 17/967 with nolasiban versus 13/865 with placebo

Congenital anomalies

Three studies of intravenous atosiban (Moraloglu 2010; Ng 2014; Yuan 2019), one study of oral nolasiban (Griesinger 2021), and one study of subcutaneous barusiban (Bosch 2019), reported on congenital anomalies.

Intravenous atosiban versus control (normal saline or no intervention)

All three studies (N = 1184) reported there was no difference in the rate of congenital anomalies between groups (very low‐certainty evidence).

Subcutaneous barusiban versus control (placebo)

One study (N = 255) reported comparable neonatal outcomes between groups (very low‐certainty evidence).

Oral nolasiban versus control (placebo)

One study (N = 1832) reported there were no differences in the rate of congenital anomalies between groups (17/967 with nolasiban versus 12/865 with placebo; low‐certainty evidence).

Discussion

Summary of main results

We included nine studies (eleven randomised controlled trials (RCT)) investigating the role of oxytocin antagonists in 3733 women undergoing embryo transfer (ET). The route of administration varied between intravenous (atosiban), oral (nolasiban), and subcutaneous (barusiban). The RCTs included fresh or frozen‐thawed transfers of cleavage or blastocyst stage embryos.

We are uncertain of the effect of intravenous (IV) atosiban on live birth rate (low‐certainty evidence) and miscarriage rate (very low‐certainty evidence) when compared to placebo or no intervention. Intravenous atosiban may increase clinical pregnancy rate (low‐certainty evidence), and we are uncertain whether complication rates were influenced by the use of intravenous atosiban, due to insufficient data (very low‐certainty evidence).

Oral nolasiban likely does not increase live birth rate (high‐certainty evidence), and we are uncertain of the effect of oral nolasiban on miscarriage rate (low‐certainty evidence) when compared to placebo. Oral nolasiban improves clinical pregnancy rate (high‐certainty evidence), and probably does not increase multiple or ectopic pregnancy and other complication rates (moderate‐certainty evidence).

One RCT investigated subcutaneous barusiban in comparison with placebo, but did not report on live birth or miscarriage. We are uncertain whether subcutaneous barusiban reduces clinical pregnancy rate (very low‐certainty evidence). More mild or moderate injection site reactions were reported with barusiban than with placebo, but there was no difference in severe reactions. No serious drug reactions were reported, and neonatal outcome was comparable between groups (very low‐certainty evidence).

Overall, the limited data and the very low certainty of the evidence for most outcomes did not allow us to reach robust conclusions about the effectiveness and safety of oxytocin antagonists around the time of ET.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

All RCTs reported on clinical pregnancy, which is an important secondary outcome, but only four RCTs continued follow‐up until live birth, which is the most important primary outcome. Most RCTs (7/9) reported miscarriage rates. Most RCTs (8/9) reported on the absence of complications, but only in a narrative form, with no absolute numbers. Data were insufficient for all planned subgroup analyses.

The inclusion criteria for participants ensured a broad range of subfertility causes and women's characteristics, similar to those expected in a regular assisted reproduction unit.

In addition to the published data collected, we also made multiple efforts to retrieve extra details on the trials by communicating with authors.

Quality of the evidence

We rated six of the nine studies at unclear risk of bias in at least two of the seven domains assessed. Common problems were unclear reporting of study methods and lack of blinding. Brief reporting of results in studies published as abstracts represented another potential source of bias.

The certainty of the evidence, assessed with GRADE methodology, varied from very low to high for live birth and clinical pregnancy, which means that further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect, and may change the estimate for some subgroups with low‐ and very‐low certainty. The certainty of the evidence for miscarriage and other complications varied from very low to moderate, meaning that we are very uncertain about the estimate. The main limitations in the overall certainty of the evidence were high risk of bias, and serious or very serious imprecision.

Potential biases in the review process

We performed a systematic search in consultation with the Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group Information Specialist, but we cannot be sure we identified all relevant trials. We pre‐published and followed our protocol (Craciunas 2016b).

We attempted to contact study authors when data were missing, but only one out of seven contacted study authors replied. When the risk of bias was classified as unclear in two or more domains, due to lack of methodology details, we downgraded the certainty of evidence one level for serious risk of bias.

We performed analyses on an intention‐to‐treat basis. Data from five ongoing studies may inform future updates of this review.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Five meta‐analyses, evaluating the role of oxytocin antagonists, have been published.

Kim 2014 meta‐analysed three RCTs, and found increased clinical pregnancy and implantation rates following the administration of IV atosiban. The study was published as a conference abstract and lacked methodological details. The three included RCTs are likely to be Ahn 2009, Moraloglu 2010, and Song 2013, given the date of publication and the number of included participants (340 versus 1646 in the atosiban group of the present review).

Kim 2016 performed a second meta‐analysis of three RCTs, and found an increased implantation rate, but no difference in clinical pregnancy and miscarriage rates following the administration of IV atosiban. They included Ahn 2009, Moraloglu 2010, and Ng 2014, but excluded Song 2013 because it was written in Chinese. The total number of participants was 1020 as opposed to 1646 in the atosiban group of the present review.

Huang 2017 meta‐analysed six studies, and found higher implantation and clinical pregnancy rates, and similar miscarriage, live birth, multiple pregnancy, and ectopic pregnancy rates following the administration of IV atosiban. They included three of the RCTs in this review (Moraloglu 2010; Ng 2014; Song 2013), and three retrospective studies.

Li 2017 meta‐analysed six studies, and found higher clinical pregnancy rates, and similar positive pregnancy test, miscarriage, multiple pregnancy, and ectopic pregnancy rates following the administration of IV atosiban. They included two of the RCTs in this review (Moraloglu 2010; Ng 2014), and four non‐randomised studies.

Schwarze 2020 meta‐analysed six studies, and found increased clinical pregnancy rate following the administration of IV atosiban. They included four of the RCTs in this review (He 2016a; Hebisha 2018; Moraloglu 2010; Ng 2014), and two non‐randomised studies.

In addition to providing primary data for the three multi‐arm RCTs investigating oral nolasiban, Griesinger 2021 performed an individual patient data meta‐analysis for oral nolasiban 900 mg, and found an increased ongoing pregnancy rate, and a similar live birth rate when data from days three and five post‐ET were combined.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is currently insufficient evidence to suggest that oxytocin antagonists increase the live birth rate. No clear conclusions about effectiveness and safety of oxytocin antagonists around the time of embryo transfer (ET) can be drawn in this systematic review.

Implications for research.

Future randomised controlled trials (RCT) should be conducted according to CONSORT guidelines, with adequate randomisation and concealment techniques to reduce selection bias. Blinding throughout the treatment cycle and during ET may reduce potential performance bias (adjusting ovarian stimulation doses, deciding the timing of maturation triggering, oocyte retrieval, and technique during embryo transfer).

They should report on live birth and adverse events (including direct adverse effects of oxytocin antagonists, maternal pregnancy complications, foetal complications) as primary outcomes to allow the quantification of the overall effect and the safety profile of the intervention.

Attempts should be made to identify subgroups of women who are more likely to benefit from this intervention; we suggest:

high responders to ovarian hyperstimulation (contractions are positively correlated with estradiol levels);

difficult ET, based on the length of time to complete, need to use more rigid catheters, presence of blood on catheter;

presence of contractions following previous ETs or during the current ET.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 December 2021 | Amended | Correcting links to some appendices. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 10, 2016 Review first published: Issue 9, 2021

Acknowledgements

We thank Helen Nagels (Managing Editor), Marian Showell (Information Specialist), and the editorial board of the Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility (CGF) Group for their invaluable assistance in developing this review.

We thank Drs Lizzi Glanville, Rik van Eekelen, and Harry Siristatidis for providing peer review comment on the draft review, and Ms Melissa Vercoe for advising on wording of the plain language summary.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility specialised register search strategy

ProCite platform

Searched 15 March 2021

Keywords CONTAINS "IVF" or "ICSI" or "ET" or "intracytoplasmic sperm injection techniques" or "intracytoplasmic sperm injection" or "in‐vitro fertilisation " or "in vitro fertilization" or "Embryo Transfer" or "ovarian stimulation" or "ovarian stimulation controlled ovarian stimulation" or "ovulation induction" or "ovulation stimulation" or "superovulation" or "superovulation induction" or "ovarian hyperstimulation" or "poor responders" or" poor responder" or "poor prognostic patients" or "controlled ovarian hyperstimulation" or "controlled ovarian stimulation" or "COH" or Title CONTAINS "IVF" or "ICSI" or "ET" or "intracytoplasmic sperm injection techniques" or "intracytoplasmic sperm injection" or "in‐vitro fertilisation " or "in vitro fertilization" or "Embryo Transfer" or "ovarian stimulation" or "ovarian stimulation controlled ovarian stimulation" or "ovulation induction" or "ovulation stimulation" or "superovulation" or "superovulation induction" or "ovarian hyperstimulation"

AND

Keywords CONTAINS "oxytocin antagonist" or "atosiban" or "barusiban" or "Vasopressin Receptor Antagonists" or "Vasopressins antagonists" or Title CONTAINS "oxytocin antagonist" or "atosiban" or "barusiban" or "Vasopressin Receptor Antagonists" or "Vasopressins antagonists"

(20 records)

Appendix 2. CENTRAL via the Cochrane Register of Studies Online (CRSO) search strategy

Web platform

Searched 15 March 2021

#1 MESH DESCRIPTOR Embryo Transfer EXPLODE ALL TREES 1106

#2 MESH DESCRIPTOR Fertilization in Vitro EXPLODE ALL TREES 2077

#3 MESH DESCRIPTOR Sperm Injections, Intracytoplasmic EXPLODE ALL TREES 542

#4 (embryo* adj2 transfer*):TI,AB,KY 4181

#5 (vitro fertili?ation):TI,AB,KY 3542

#6 ivf:TI,AB,KY 5844

#7 icsi:TI,AB,KY 2842

#8 (intracytoplasmic sperm injection*):TI,AB,KY 2002

#9 (blastocyst* adj2 transfer*):TI,AB,KY 430

#10 #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 9111

#11 Vasotocin:TI,AB,KY 64

#12 MESH DESCRIPTOR Vasotocin EXPLODE ALL TREES 61

#13 (oxytocin adj5 antagonist*):TI,AB,KY 91

#14 Atosiban:TI,AB,KY 125

#15 Barusiban:TI,AB,KY 14

#16 Tractocile:TI,AB,KY 9

#17 Antocin:TI,AB,KY 4

#18 vasotocin:TI,AB,KY 64

#19 (vasopressin adj3 antagonist*):TI,AB,KY 264

#20 #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 440

#21 #10 AND #20 38

Appendix 3. MEDLINE search strategy

Ovid platform

Searched from 1946 to 15 March 2021

1 exp embryo transfer/ or exp fertilization in vitro/ or exp sperm injections, intracytoplasmic/ (42543) 2 embryo transfer$.tw. (12794) 3 vitro fertili?ation.tw. (24161) 4 ivf.tw. (24736) 5 icsi.tw. (8861) 6 intracytoplasmic sperm injection$.tw. (7554) 7 (blastocyst adj2 transfer$).tw. (1193) 8 assisted reproduct$.tw. (15917) 9 ovulation induc$.tw. (4221) 10 (ovari$ adj2 stimulat$).tw. (7456) 11 superovulat$.tw. (3502) 12 COH.tw. (1848) 13 infertil$.tw. (63602) 14 subfertil$.tw. (5302) 15 (ovari$ adj2 induction).tw. (291) 16 exp Reproductive Techniques, Assisted/ (71293) 17 (ovar$ adj2 hyperstimulation).tw. (5248) 18 or/1‐17 (141658) 19 exp Vasotocin/ (1885) 20 (oxytocin adj5 antagonist$).tw. (1005) 21 Atosiban.tw. (423) 22 Barusiban.tw. (12) 23 Tractocile.tw. (10) 24 Antocin.tw. (7) 25 vasotocin.tw. (1884) 26 (vasopressin adj3 antagonist$).tw. (1960) 27 (OTR$ adj3 antagonist$).tw. (100) 28 or/19‐27 (5184) 29 18 and 28 (38) 30 randomized controlled trial.pt. (524951) 31 controlled clinical trial.pt. (94095) 32 randomized.ab. (512588) 33 randomised.ab. (102320) 34 placebo.tw. (221898) 35 clinical trials as topic.sh. (195102) 36 randomly.ab. (353009) 37 trial.ti. (236038) 38 (crossover or cross‐over or cross over).tw. (88266) 39 or/30‐38 (1422339) 40 exp animals/ not humans.sh. (4799247) 41 39 not 40 (1310244) 42 29 and 41 (12)

Appendix 4. Embase search strategy

Ovid platform

Searched from 1980 to 15 March 2021

1 exp embryo transfer/ or exp fertilization in vitro/ or exp intracytoplasmic sperm injection/ (73749) 2 embryo$ transfer$.tw. (22553) 3 in vitro fertili?ation.tw. (31952) 4 icsi.tw. (16947) 5 intracytoplasmic sperm injection$.tw. (10158) 6 (blastocyst adj2 transfer$).tw. (2620) 7 ivf.tw. (42566) 8 assisted reproduct$.tw. (24296) 9 ovulation induc$.tw. (5759) 10 superovulat$.tw. (4002) 11 COH.tw. (2626) 12 infertil$.tw. (88942) 13 subfertil$.tw. (7278) 14 (ovari$ adj2 induction).tw. (336) 15 exp infertility therapy/ (106086) 16 exp ovulation induction/ (15033) 17 exp ovary hyperstimulation/ (9883) 18 (ovar$ adj2 hyperstimulation).tw. (7738) 19 (ovar$ adj2 stimulat$).tw. (11863) 20 or/1‐19 (200167) 21 exp oxytocin antagonist/ or exp erlosiban/ (808) 22 exp atosiban/ (1086) 23 exp argiprestocin/ (1694) 24 Vasotocin.tw. (1715) 25 (oxytocin adj5 antagonist$).tw. (1162) 26 Atosiban.tw. (616) 27 Barusiban.tw. (22) 28 Tractocile.tw. (131) 29 Antocin.tw. (22) 30 (vasopressin adj3 antagonist$).tw. (2433) 31 (OTR$ adj3 antagonist$).tw. (145) 32 or/21‐31 (6467) 33 20 and 32 (102) 34 Clinical Trial/ (995663) 35 Randomized Controlled Trial/ (647655) 36 exp randomization/ (90716) 37 Single Blind Procedure/ (42253) 38 Double Blind Procedure/ (179713) 39 Crossover Procedure/ (66396) 40 Placebo/ (351498) 41 Randomi?ed controlled trial$.tw. (253099) 42 Rct.tw. (41233) 43 random allocation.tw. (2156) 44 randomly.tw. (468434) 45 randomly allocated.tw. (37755) 46 allocated randomly.tw. (2640) 47 (allocated adj2 random).tw. (840) 48 Single blind$.tw. (26374) 49 Double blind$.tw. (211926) 50 ((treble or triple) adj blind$).tw. (1290) 51 placebo$.tw. (318094) 52 prospective study/ (670949) 53 or/34‐52 (2585356) 54 case study/ (76966) 55 case report.tw. (432402) 56 abstract report/ or letter/ (1144394) 57 or/54‐56 (1642153) 58 53 not 57 (2528322) 59 (exp animal/ or animal.hw. or nonhuman/) not (exp human/ or human cell/ or (human or humans).ti.) (6175541) 60 58 not 59 (2354902) 61 33 and 60 (37)

Appendix 5. PsycINFO search strategy

Ovid Platform

Searched from 1806 to 15 March 2021

1 exp reproductive technology/ (1907) 2 in vitro fertili?ation.tw. (792) 3 ivf‐et.tw. (20) 4 (ivf or et).tw. (146085) 5 icsi.tw. (79) 6 intracytoplasmic sperm injection$.tw. (60) 7 (blastocyst adj2 transfer$).tw. (4) 8 assisted reproduct$.tw. (1049) 9 ovulation induc$.tw. (33) 10 (ovari$ adj2 stimulat$).tw. (60) 11 COH.tw. (138) 12 superovulat$.tw. (8) 13 infertil$.tw. (3706) 14 subfertil$.tw. (99) 15 (ovar$ adj2 induction).tw. (9) 16 (ovar$ adj2 hyperstimulation).tw. (14) 17 or/1‐16 (150992) 18 (oxytocin adj5 antagonist$).tw. (200) 19 Atosiban.tw. (28) 20 vasotocin.tw. (295) 21 (vasopressin adj3 antagonist$).tw. (153) 22 (OTR$ adj3 antagonist$).tw. (41) 23 or/18‐22 (632) 24 17 and 23 (14) 25 random.tw. (60972) 26 control.tw. (460557) 27 double‐blind.tw. (23518) 28 clinical trials/ (11875) 29 placebo/ (5933) 30 exp Treatment/ (1084470) 31 or/25‐30 (1494667) 32 24 and 31 (8)

Appendix 6. CINAHL search strategy

Ebsco platform

Searched from 1961 to 15 March 2021

| S25 | S16 AND S24 | 12 |

| S24 | S17 OR S18 OR S19 OR S20 OR S21 OR S22 OR S23 | 446 |

| S23 | TX (OTR* N3 antagonist*) | 5 |

| S22 | TX (vasopressin N3 antagonist*) | 320 |

| S21 | TX Tractocile | 2 |

| S20 | TX Barusiban | 2 |

| S19 | TX Atosiban | 77 |

| S18 | TX (oxytocin N5 antagonist*) | 69 |

| S17 | TX Vasotocin | 7 |

| S16 | S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 OR S9 OR S10 OR S11 OR S12 OR S13 OR S14 OR S15 | 15,972 |

| S15 | TX (ovar* N2 induction) | 44 |

| S14 | TX (ovar* N2 hyperstimulation) | 843 |

| S13 | TX COH | 247 |

| S12 | TX superovulat* | 87 |

| S11 | TX ovulation induc* | 1,772 |

| S10 | TX assisted reproduct* | 3,925 |

| S9 | (MM "Reproduction Techniques+") | 9,104 |

| S8 | TX intracytoplasmic sperm injection* | 924 |

| S7 | TX embryo* N3 transfer* | 3,146 |

| S6 | TX ovar* N3 hyperstimulat* | 849 |

| S5 | TX ovari* N3 stimulat* | 1,026 |

| S4 | TX IVF or TX ICSI | 5,118 |

| S3 | (MM "Fertilization in Vitro") | 3,476 |

| S2 | TX vitro fertilization | 7,088 |

| S1 | TX vitro fertilisation | 7,088 |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Oxytocin antagonists vs control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Live birth | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1.1 Intravenous (IV) atosiban | 1 | 800 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.88, 1.24] |

| 1.1.2 Oral nolasiban | 1 | 1832 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.13 [0.99, 1.28] |

| 1.2 Miscarriage | 6 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.2.1 Intravenous (IV) atosiban | 5 | 1424 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.09 [0.73, 1.62] |

| 1.2.2 Oral nolasiban | 1 | 1832 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.47 [0.73, 2.97] |

| 1.3 Miscarriage per clinical pregnancy | 6 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.3.1 Intravenous (IV) atosiban | 5 | 637 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.60, 1.20] |

| 1.3.2 Oral nolasiban | 1 | 685 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.17 [0.56, 2.46] |

| 1.4 Clinical pregnancy | 9 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.4.1 Intravenous (IV) atosiban | 7 | 1646 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.50 [1.18, 1.89] |

| 1.4.2 Subcutaneous (sc) barusiban | 1 | 255 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.96 [0.69, 1.35] |

| 1.4.3 Oral nolasiban | 1 | 1832 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.15 [1.02, 1.30] |

| 1.5 Complications | 6 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.5.1 Multiple pregnancy (intravenous (IV) atosiban) | 4 | 1304 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.12 [0.81, 1.55] |

| 1.5.2 Multiple pregnancy (oral nolasiban) | 1 | 1832 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.46 [0.64, 3.32] |

| 1.5.3 Ectopic pregnancy (intravenous (IV) atosiban) | 2 | 920 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.42, 2.31] |

| 1.5.4 Ectopic pregnancy (oral nolasiban) | 1 | 1832 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.81 [0.19, 3.45] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Ahn 2009.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Design: 2‐arm parallel randomised controlled trial | |

| Participants | Number: 40 Women's age (mean years; experimental versus control): 35 vs 34.7 Inclusion criteria: two or more failed in vitro fertilisation / intracytoplasmic sperm injection cycles Exclusion criteria: reduced ovarian reserve Ovarian controlled hyperstimulation: Gonadotropin hormone‐releasing hormone antagonist multidose protocol Fertilisation: not specified, likely IVF Stage of the embryo at transfer: cleavage Embryo processing: fresh Number of embryos transferred (mean; experimental vs control): 3 vs 2.9 | |

| Interventions | Experimental (N = 20): intravenous administration of atosiban (mixed vasopressin V1A/oxytocin antagonist) started with a bolus dose of 6.75 mg one hour before embryo transfer, and continued at an infusion rate of 18 mg/hour. After ET, administered atosiban was reduced to 6 mg/hour and continued for 2 hours. Control (N = 20): no intervention |

|

| Outcomes | Biochemical pregnancy, clinical pregnancy, miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy | |

| Notes | Location: Asan Medical Center, Seoul, South Korea

Period: May 2007 to May 2008

Power calculation: not mentioned

Funding: not mentioned

Trial registration: not mentioned

Publication type: full text Corresponding author emailed on 5 April 2020; no reply to June 2021 Translated using Google's and Yandex's translation services |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomisation mentioned, but not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not mentioned |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | Not mentioned, likely not blinded |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Not mentioned, but unlikely to influence assessment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | All participants accounted for |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Reported on relevant outcomes |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias identified |

Bosch 2019.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Design: 2‐arm parallel RCT | |

| Participants | Number: 255 Women's age: 18 to 37 years Inclusion criteria: women undergoing IVF/ICSI, 18 to 37 years, with a history of repeated implantation failures Exclusion criteria: uterine pathology and thrombophilia Ovarian controlled hyperstimulation: not reported Fertilisation: not reported Stage of the embryo at transfer: cleavage and blastocyst Embryo processing: fresh Number of embryos transferred (mean; experimental vs control): not mentioned. | |

| Interventions | Experimental (N = 130): barusiban 40 mg administered subcutaneously 45 minutes pre‐transfer, and 10 mg administered 15 minutes post‐transfer Control (N = 125): placebo administered subcutaneously | |

| Outcomes | Implantation, clinical pregnancy, adverse events | |

| Notes | Location: multinational: Australia, Belgium, Canada, Czech Republic, Poland, Spain Period: not reported Power calculation: not reported Funding: Ferring Pharmaceuticals Trial registration: NCT01723982 Publication type: conference abstract | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Randomisation mentioned, but not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not mentioned |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Double blinding mentioned |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Not described, but unlikely to influence assessment |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Results percentages mentioned, no absolute numbers |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Reported on relevant outcomes |

| Other bias | Low risk | No other sources of bias identified |

Griesinger 2021.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods | Design: 3‐phase randomised study with 4‐arms (Implant 1), 3‐arms (Implant 2), and 2‐arms (Implant 4) | |

| Participants | Number: 247 + 778 + 807 = 1832

Women's age: 18 to 37 years

Inclusion criteria: women undergoing IVF/ICSI with fresh ET, and having at least one good