ABSTRACT

Background

Choline is an essential nutrient; however, the associations of choline and its related metabolites with cardiometabolic risk remain unclear.

Objective

We examined the associations of circulating choline, betaine, carnitine, and dimethylglycine (DMG) with cardiometabolic biomarkers and their potential dietary and nondietary determinants.

Methods

The cross-sectional analyses included 32,853 participants from 17 studies, who were free of cancer, cardiovascular diseases, chronic kidney diseases, and inflammatory bowel disease. In each study, metabolites and biomarkers were log-transformed and standardized by means and SDs, and linear regression coefficients (β) and 95% CIs were estimated with adjustments for potential confounders. Study-specific results were combined by random-effects meta-analyses. A false discovery rate <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

We observed moderate positive associations of circulating choline, carnitine, and DMG with creatinine [β (95% CI): 0.136 (0.084, 0.188), 0.106 (0.045, 0.168), and 0.128 (0.087, 0.169), respectively, for each SD increase in biomarkers on the log scale], carnitine with triglycerides (β = 0.076; 95% CI: 0.042, 0.109), homocysteine (β = 0.064; 95% CI: 0.033, 0.095), and LDL cholesterol (β = 0.055; 95% CI: 0.013, 0.096), DMG with homocysteine (β = 0.068; 95% CI: 0.023, 0.114), insulin (β = 0.068; 95% CI: 0.043, 0.093), and IL-6 (β = 0.060; 95% CI: 0.027, 0.094), but moderate inverse associations of betaine with triglycerides (β = −0.146; 95% CI: −0.188, −0.104), insulin (β = −0.106; 95% CI: −0.130, −0.082), homocysteine (β = −0.097; 95% CI: −0.149, −0.045), and total cholesterol (β = −0.074; 95% CI: −0.102, −0.047). In the whole pooled population, no dietary factor was associated with circulating choline; red meat intake was associated with circulating carnitine [β = 0.092 (0.042, 0.142) for a 1 serving/d increase], whereas plant protein was associated with circulating betaine [β = 0.249 (0.110, 0.388) for a 5% energy increase]. Demographics, lifestyle, and metabolic disease history showed differential associations with these metabolites.

Conclusions

Circulating choline, carnitine, and DMG were associated with unfavorable cardiometabolic risk profiles, whereas circulating betaine was associated with a favorable cardiometabolic risk profile. Future prospective studies are needed to examine the associations of these metabolites with incident cardiovascular events.

Keywords: choline, betaine, carnitine, dimethylglycine, cardiometabolic disease, biomarkers

Introduction

Choline and its related metabolites—betaine, carnitine, and dimethylglycine (DMG)—are major nutrients in human health and disease (1–5). As an essential nutrient, choline can be obtained from dietary sources (e.g., eggs, red meat, and soy foods) or synthesized de novo through methylation of phosphatidylethanolamine to phosphatidylcholine (1–3). While betaine, carnitine, and DMG can be obtained from dietary sources (e.g., spinach and whole-wheat products for betaine, red meat for carnitine, and beans and cereal grains for DMG) (4, 5), they are also products of choline metabolism. In addition to dietary intakes and the choline metabolism pathway, concentrations of choline and betaine in the human body have been reported to be affected by age, sex, menopausal status, metabolic health status such as glucose and cholesterol metabolism, and kidney excretion (3, 6, 7). In addition, choline, betaine, and carnitine are major precursors of trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO), a gut microbiota–derived metabolite that has been linked to cardiovascular disease (CVD) events and mortality (8).

Despite their potential roles in cardiometabolic health and disease, population studies have reported inconsistent findings regarding choline, betaine, carnitine, or DMG with cardiometabolic risk factors. Some cross-sectional studies showed higher plasma choline and carnitine and lower betaine concentrations were associated with unfavorable cardiometabolic risk profile (e.g., higher systolic blood pressure, insulin resistance, and BMI, and lower HDL cholesterol) (9–11). However, a review of 6 prospective studies found that elevated circulating concentrations of choline, carnitine, and betaine were all associated with increased risks of adverse CVD events (12). In addition, a review on dietary choline and betaine observed no clear evidence of positive associations with incident CVD but noted that high choline intake may be linked to increased CVD mortality (13). More recently, our prospective analyses among >200,000 Black and White Americans and Chinese adults showed that, while dietary sources of choline varied across ethnic groups, high choline intake was consistently associated with elevated cardiometabolic mortality (14).

Given the previous inconsistent findings and potential differences in dietary intakes (14–16) and cardiometabolic conditions across populations (17–19), large-scale analyses among ethnically and geographically diverse populations may provide more robust evidence regarding the associations of choline and related metabolites with cardiometabolic disease risk. Since circulating choline, betaine, carnitine, and DMG can be more objectively quantified than their dietary intakes and reflect integrated levels of dietary intake, endogenous biosynthesis, metabolism, and excretion, the analyses of their circulating concentrations with cardiometabolic biomarkers may more accurately capture their cardiometabolic effects. Furthermore, prior studies have shown that dietary choline and betaine correlated weakly with their plasma concentrations (20, 21), suggesting that circulating choline and related metabolites may be substantially affected by nondietary factors. To address the knowledge gap, we conducted a pooling project to examine the associations of cardiometabolic biomarkers with circulating choline, betaine, carnitine, and DMG using data from 17 studies in the United States, Europe, and Asia. Second, we evaluated potential dietary and nondietary factors that may influence the circulating concentrations of these metabolites.

Methods

Study design and population

Our study comprised cross-sectional analyses of data collected for the TMAO Pooling Project, which is primarily based on the Consortium of Metabolomics Studies (COMETS) (22). We also contacted studies that were not members of the COMETS but had data on blood TMAO and related metabolites (choline, betaine, carnitine, or DMG). In total, we pooled data from 17 studies, including 10 in the United States [the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study (CARDIA) (23); Framingham Heart Study (FHS) (24); Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS) (25); Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Family Study (IRASFS) (26); Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) (27); Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) (28); NHS II (28); Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial (PLCO) (29); Southern Community Cohort Study (SCCS) (30); and Women's Health Initiative (WHI) (31)]; 3 in Europe [the Airwave Health Monitoring Study (AIRWAVE) (32), Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention Study (ATBC) (33), and UK Adult Twin Registry (TwinsUK) (34)]; and 4 in Asia [the Guangzhou Nutrition and Health Study (GNHS) (35), Shanghai Men's Health Study (SMHS) (36), Shanghai Women's Health Study (SWHS) (37), and Tsuruoka Metabolomics Cohort Study (TMCS) (38)]. The pooling project was approved by the COMETS Steering Committee, the study committees of participating studies, and the Institutional Review Board of Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Since the work on the primary outcome, circulating TMAO, was reported in a separate paper (39), our current analyses were focused on circulating choline and its related metabolites—that is, betaine, carnitine, and DMG.

For the current analyses, we only included adult participants (>18 y) with valid data on plasma or serum choline, betaine, carnitine, or DMG. To reduce the effects of severe underlying diseases and their treatments on the concentrations of these metabolites, we excluded participants who had a history of cancer (except for nonmelanoma skin cancer), CVD (coronary artery disease, stroke, and heart failure), chronic kidney disease (physician diagnosis, or estimated glomerular filtration rate <45 mL · min−1 · 1.73 m−² in case of no physician diagnosis), or inflammatory bowel disease. A total of 32,853 adults were included in the final analyses (Supplemental Figure 1).

Metabolites and cardiometabolic biomarkers

Circulating concentrations of choline, betaine, carnitine, and DMG were measured in each study using targeted or untargeted assays. Metabolomics platforms and analytical techniques in 17 individual studies were detailed in the profile paper for the COMETS (22) and briefly presented in Supplemental Table 1. Targeted assays were performed by the Bevital A/S (Bergen, Norway) (40), Broad Institute (Boston, MA, USA) (41), Keio University (Tsuruoka, Japan) (42), University of North Carolina Nutrition Obesity Research Center (Kannapolis, NC, USA) (43), and Sun Yat-sen University (Guangzhou, China) (35), whereas untargeted assays were performed by the Imperial College London's National Phenome Centre (London, UK) (44), and Metabolon, Inc. (Morrisville, NC, USA) (45). The majority of studies utilized GC-MS and/or LC-MS from the Broad Institute or Metabolon, Inc. The measurements of choline-related metabolites agreed well between the Broad Institute and Metabolon, Inc., platforms (Spearman correlation coefficients were 0.91, 0.75, 0.62, and 0.90 for choline, betaine, carnitine, and DMG) (22). To account for interstudy differences and improve normality, all metabolites were natural log-transformed and standardized using study-specific means and SDs.

Cardiometabolic biomarkers were measured, including glucose (milligrams/deciliter), insulin (microunits/milliliter), glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c; % of total hemoglobin), systolic blood pressure (SBP; millimeters of mercury), diastolic blood pressure (DBP; millimeters of mercury), total cholesterol (milligrams/deciliter), HDL cholesterol (milligrams/deciliter), LDL cholesterol (milligrams/deciliter), triglycerides (milligrams/deciliter), C-reactive protein (CRP; milligrams/liter), IL-6 (picograms/milliliter), creatinine (milligrams/deciliter), and homocysteine (micromoles/liter). Prior to statistical analyses, they were harmonized to the same units and natural log-transformed and standardized by the mean and SD in each study (SBP and DBP were not log-transformed due to their normal distributions).

Collection of survey data

Data on demographics, diet and lifestyle, anthropometrics, and medical history were collected at the time of blood sample collection (i.e., mostly at enrollment) in individual studies. Variables harmonized across studies include age at blood collection, sex, self-identified ethnicity, BMI, waist-to-hip ratio (WHR), smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity, menopausal status and hormone therapy (women only), history of diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), as well as dietary information. Disease history was self-reported based on doctor diagnosis or medication use. Dietary intakes of major foods and nutrients per day were estimated in 15 studies using validated food-frequency questionnaires and country- or region-specific food-composition tables (data were not available from the AIRWAVE and TMCS) and were standardized to intakes per 2000 kcal/d (46). Food-portion sizes for transformations were defined as follows: red meat, processed meat, poultry, total fish, and shellfish [1 serving = 4 ounces (oz)/113.4 g]; eggs (50 g); dairy foods [milk/cottage cheese (8 fluid oz/240 g), firm cheese (50 g), and ice cream (100 g)]; soy products [soy milk (8 fluid oz/240 g) and tofu/soybeans/soy meats (4 oz/113.4 g)]; legumes (50 g in dry weight); nuts (30 g in dry weight); vegetables (80 g); fruits (80 g); and whole grains (50 g in dry weight). In the statistical analyses, food intakes were modeled as each 1-serving/day increase, macronutrients were modeled as each 5%-energy/day intake from them, and dietary fiber was modeled as each 5-gram/day increase.

Statistical analysis

A standard analytic protocol was followed to analyze data from all participating studies. Linear regressions were used to estimate β-coefficients and 95% CIs for the associations of cardiometabolic biomarkers with circulating metabolites. Since metabolites and biomarker concentrations were all log-transformed and standardized by their means and SDs in each study, β-coefficients indicate changes in SD units on the log scale. Covariates were determined a prioriand adjusted in 3 models. In model 1, we adjusted for age (years), sex (men and women), ethnicity (White, Black, Hispanic, Asian, and others), and fasting time (<6 and ≥6 h). In model 2, we additionally adjusted for education (<high school, high school graduation, post–high school training or some college, and ≥college graduation), obesity [BMI (kg/m2) <18.5, 18.5–24.9, 25.0–29.9, and ≥30.0], central obesity (normal, moderate, high, and very high defined per WHO criteria; WHR <0.90, 0.90–0.94, 0.95–0.99, and ≥1.00 for non-Asian men; <0.85, 0.85–0.89, 0.90–0.94, ≥0.95 for Asian men; and <0.75, 0.75–0.79, 0.80–0.84, and ≥0.85 for all women), tobacco smoking status (never, former, and current), alcohol drinking (none, >0 to ≤1, >1 to ≤2, and >2 drinks/d; 1 drink = 14 g ethanol), total physical activity (study- and sex-specific tertiles of total physical activity), use of multivitamins (yes or no), menopausal status and hormone therapy (yes or no, for women only), and intakes of red meat, eggs, and fish (study- and sex-specific quintiles). In model 3, we further adjusted for metabolic disease status, including diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and NAFLD (yes or no). Missing values of covariates were coded as an unknown category in the analyses (proportions of missing are provided in Supplemental Table 2). We conducted 3 sensitivity analyses by 1) additionally adjusting for creatinine to minimize the effects of renal function (FHS, MESA, SCCS, SMHS, SWHS, and TMCS only), 2) excluding recent antibiotics users to control for the effects of microbiota metabolism of nutrients (FHS, MESA, SCCS, SMHS, SWHS, and TMCS only), and 3) additionally adjusting for TMAO to control for its cardiometabolic effects (FHS, SMHS, SWHS, and TMCS only). We also evaluated whether the associations of choline and related metabolites with cardiometabolic biomarkers were modified by TMAO concentrations (FHS, SMHS, SWHS, and TMCS only). We further conducted stratified analyses by age, sex, ethnicity, region of cohorts, fasting time, obesity, central obesity, metabolic disease status (diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and NAFLD), and intakes of red meat, fish, fiber, and vegetables/fruits.

Using the same linear regression models, we also examined associations of circulating choline and related metabolites with demographics (age, sex, and ethnicity), lifestyle factors (smoking, alcohol drinking, and physical activity), metabolic conditions (obesity, central obesity, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and NAFLD), and dietary intakes. In diet-related analyses, we excluded participants with implausible energy intakes (beyond ±5 SDs of the study- and sex-specific mean) and additionally adjusted for total energy intake in all 3 models.

Study-specific estimates were combined using random-effects meta-analyses (47), and heterogeneity across studies was assessed based on I2. Subgroup heterogeneity was assessed using meta-regression. P values were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure (48), and false discovery rate–adjusted P values (Q values) were estimated, with threshold set at 0.05. Study-specific analyses were conducted by using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc.), and meta-analyses were performed by using Stata 16.0 (StataCorp).

Results

Basic characteristics of study participants

Of the 32,853 participants from 17 studies (Supplemental Table 1), ages ranged from 19 to 84 y, 20,030 (61.0%) were women, 16,393 (49.9%) were White, 13,293 (40.5%) were Asian, 1779 (5.4%) were Black, and 1252 (3.8%) were Hispanic. Details of participants from each individual study are provided in Supplemental Table 2.

Associations of circulating choline and related metabolites with cardiometabolic biomarkers

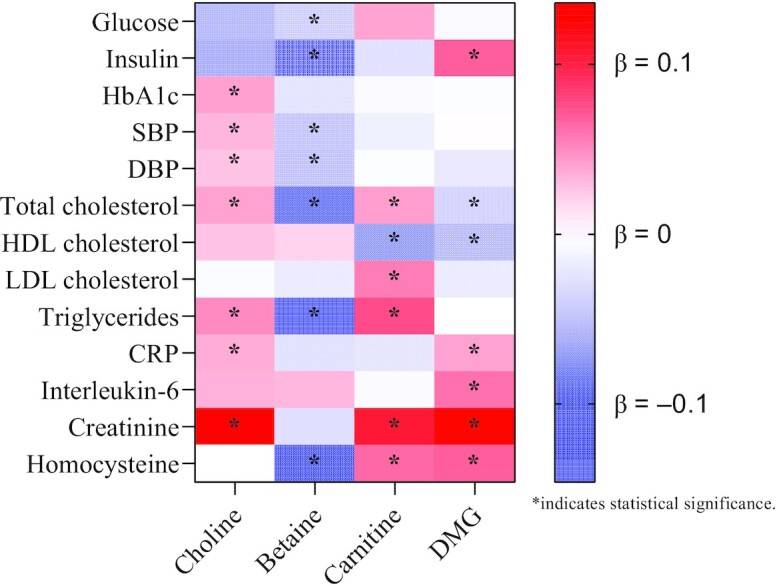

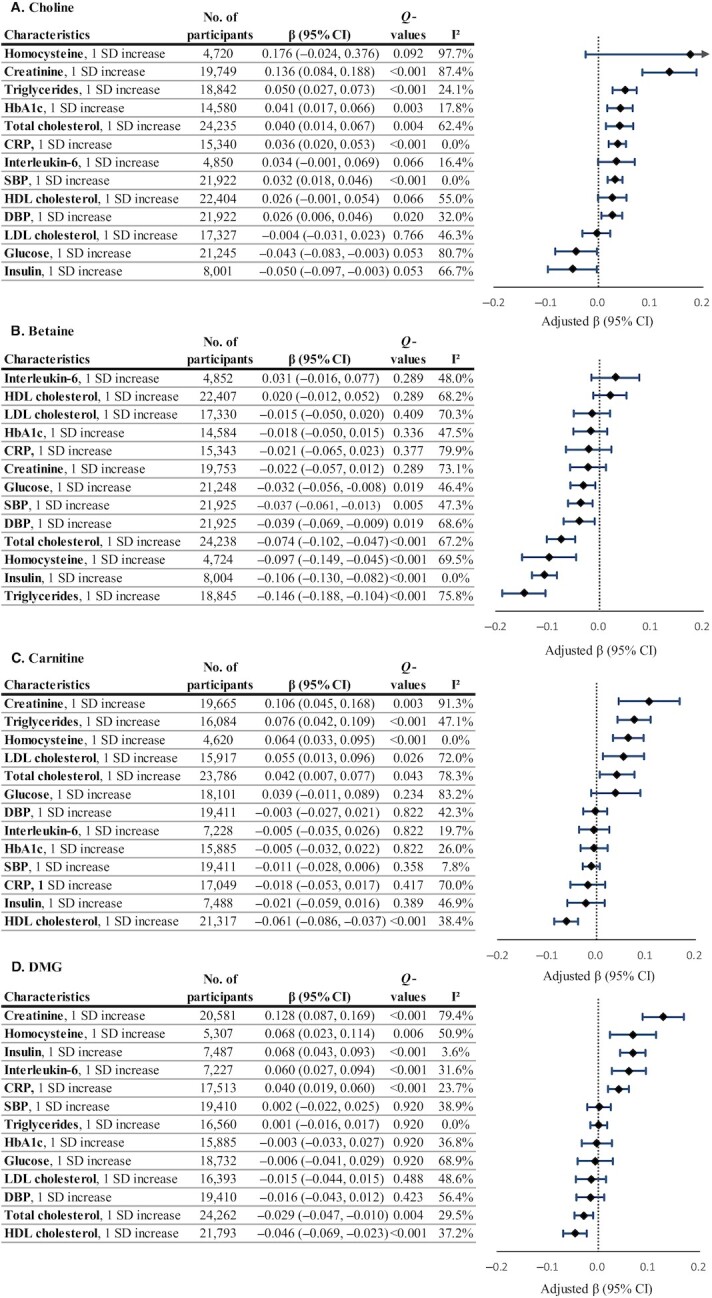

Circulating choline showed positive associations with HbA1c, blood pressure, total cholesterol, triglycerides, CRP, and creatinine (Figure 1 and Supplemental Table 3). After adjustments for sociodemographic, lifestyle, and dietary factors and metabolic conditions, the βs (95% CIs) corresponding to a 1-SD increase in biomarker on the log scale, in descending order of magnitude, were 0.136 (95% CI: 0.084, 0.188) for creatinine, 0.050 (0.027, 0.073) for triglycerides, 0.041 (0.017, 0.066) for HbA1c, 0.040 (0.014, 0.067) for total cholesterol, 0.036 (0.020, 0.053) for CRP, 0.032 (0.018, 0.046) for SBP, and 0.026 (0.006, 0.046) for DBP (all Q ≤ 0.020; Figure 2A).

FIGURE 1.

Heat map for the associations of choline and related metabolites with cardiometabolic biomarkers. Linear regression coefficients (β) were adjusted for age; sex; ethnicity; fasting time; education; obesity; central obesity; smoking status; alcohol drinking; physical activity level; use of multivitamins; menopausal status and hormone therapy in women; intakes of red meat, eggs, and fish; and history of diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. βs indicate the increase or decrease in SD units of choline, betaine, carnitine, and DMG on the log scale. Statistical significance is indicated by false discovery rate–adjusted P values (Q values) <0.05. CRP, C-reactive protein; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DMG, dimethylglycine; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

FIGURE 2.

Circulating choline (A), betaine (B), carnitine (C), and DMG (D) in relation to cardiometabolic biomarkers. Regression coefficients (β) and 95% CIs were adjusted for age; sex; ethnicity; fasting time; education; obesity; central obesity; smoking status; alcohol drinking; physical activity level; use of multivitamins; menopausal status and hormone therapy in women; intakes of red meat, eggs, and fish; and history of diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. βs indicate the increase or decrease in SD units of choline, betaine, carnitine, and DMG on the log scale. Q values represent corrected P values for each group of analyses by controlling the false discovery rate. CRP, C-reactive protein; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DMG, dimethylglycine; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; SBP, systolic blood pressure.

In contrast, circulating betaine showed inverse associations with glucose, insulin, blood pressure, total cholesterol, triglycerides, and homocysteine (Figure 1 and Supplemental Table 3). The βs (95% CIs) corresponding to a 1-SD increase in biomarker on the log scale, in descending order of magnitude, were −0.146 (−0.188, −0.104) for triglycerides, −0.106 (−0.130, −0.082) for insulin, −0.097 (−0.149, −0.045) for homocysteine, −0.074 (−0.102, −0.047) for total cholesterol, −0.039 (−0.069, −0.009) for DBP, −0.037 (−0.061, −0.013) for SBP, and −0.032 (−0.056, −0.008) for glucose (all Q ≤ 0.019; Figure 2B).

Similar to choline, circulating carnitine was positively associated with creatinine (β = 0.106; 95% CI: 0.045, 0.168), triglycerides (0.076; 0.042, 0.109), homocysteine (0.064; 0.033, 0.095), LDL cholesterol (0.055; 0.013, 0.096), and total cholesterol (0.042; 0.007; 0.077), but negatively associated with HDL cholesterol (−0.061; −0.086, −0.037; Figure 1, Figure 2C, and Supplemental Table 3). Circulating DMG was positively related to creatinine (0.128; 0.087, 0.169), homocysteine (0.068; 0.023, 0.114), insulin (0.068; 0.043, 0.093), interleukin-6 (0.060; 0.027, 0.094), and CRP (0.040; 0.019, 0.060), but negatively related to HDL cholesterol (−0.046; −0.069, −0.023), and total cholesterol (−0.029; −0.047, −0.010; Figure 1, Figure 2D, and Supplemental Table 3).

Sensitivity analyses with further adjustment for creatinine, exclusion of recent antibiotic users, or additional adjustment for TMAO did not show appreciable changes in the results from the main analyses (Supplemental Tables 4 and 5). In addition, the associations between these metabolites and cardiometabolic biomarkers remained robust in a series of analyses stratified by demographics, CVD risk factors, dietary factors, and TMAO concentrations, and no significant interactions were found (Supplemental Tables 6–9).

Associations of circulating choline and related metabolites with dietary intakes and nondietary characteristics

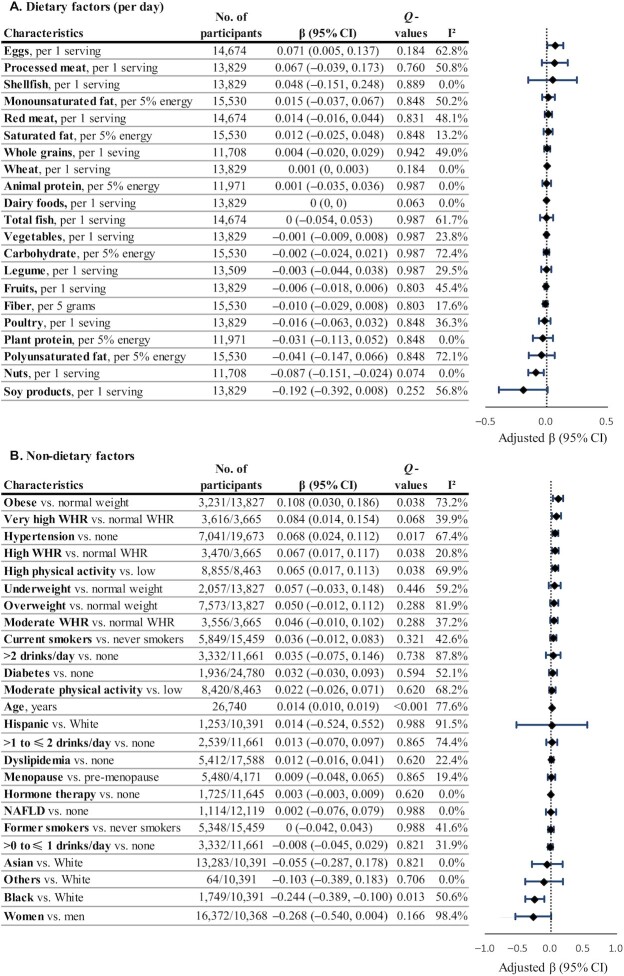

In our pooled analyses, circulating choline was not significantly associated with any dietary factors (Figure 3 and Supplemental Table 10). In a subset of data from 3 studies (n = 2809), we also did not find a significant correlation between total dietary choline and circulating choline (partial correlation coefficient = 0.024, Q = 0.207; Supplemental Table 11). However, among US studies, circulating choline was positively associated with red meat intake (β = 0.066 per 1-serving/d increase), whereas among Asian studies, choline concentration was positively associated with egg intake and inversely with intakes of legumes and fruits (β = 0.215, −0.083, and −0.043, respectively, per 1-serving/d increase; data not shown in tables/figures). Among nondietary factors, circulating choline was positively associated with older age (β = 0.014 per 1-year increase), high physical activity (β = 0.065 vs. low physical activity), obesity (β = 0.108 vs. normal weight), high WHR (β = 0.067 vs. normal WHR), and hypertension (β = 0.068 vs. normal blood pressure), and was lower among Black than White participants in the US studies (β = −0.244) (Figure 3 and Supplemental Table 12).

FIGURE 3.

Circulating choline in relation to dietary (A) and nondietary (B) factors. Regression coefficients (β) and 95% CIs were adjusted for age; sex; ethnicity; fasting time; education; obesity; central obesity; smoking status; alcohol drinking; physical activity level; use of multivitamins; menopausal status and hormone therapy in women; intakes of red meat, eggs, and fish; history of diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and NAFLD; and total energy. Dietary covariates were mutually adjusted for other foods and included in the model as the cohort- and sex-specific quintiles. Total energy intake was additionally adjusted for in diet-related analyses. βs indicate the increase or decrease in SD units of choline on the log scale. Q values represent corrected P values for each group of analyses by controlling the false discovery rate. NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; WHR, waist-to-height ratio.

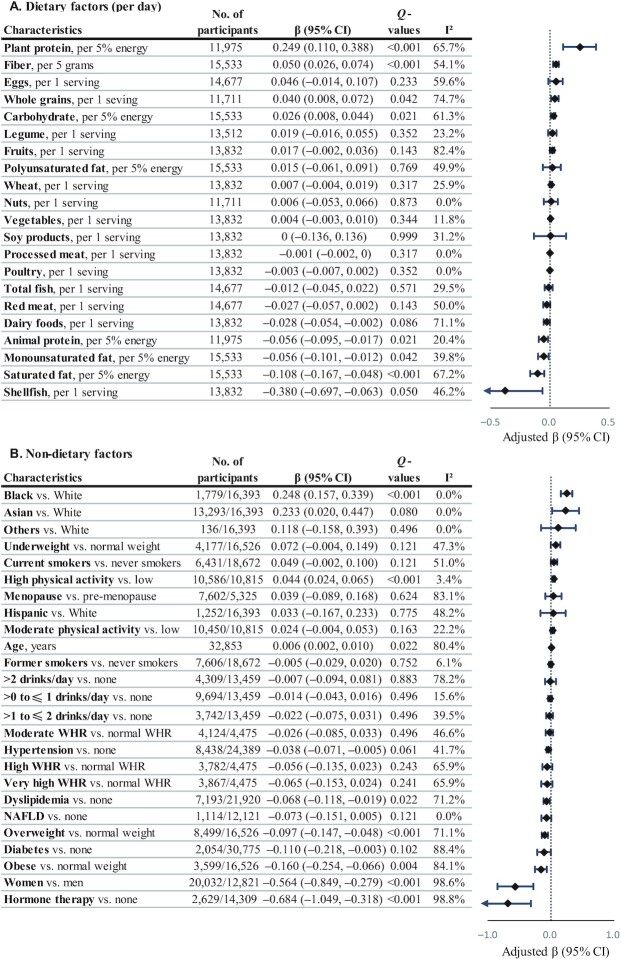

Circulating betaine was positively associated with intakes of plant protein (β = 0.249 per 5% energy/d increase), fiber (β = 0.050 per 5 g/d increase), whole grains (β = 0.040 per 1 serving/d increase), and carbohydrate (β = 0.026 per 5% energy/d increase) but inversely with intakes of saturated fat (β = −0.108 per 5% energy/d increase), monounsaturated fat (β = −0.056), and animal fat (β = −0.056; Figure 4 and Supplemental Table 13). Circulating betaine was positively associated with high physical activity (β = 0.044) and negatively associated with overweight and obesity (β = −0.097 and −0.160), dyslipidemia (β = −0.068), and hormone therapy (β = −0.684) (Figure 4 and Supplemental Table 14). Circulating betaine was lower in women than in men (β = −0.564) and higher in Black than in White participants in the US studies (β = 0.248).

FIGURE 4.

Circulating betaine in relation to dietary (A) and nondietary (B) factors. Regression coefficients (β) and 95% CIs were adjusted for age; sex; ethnicity; fasting time; education; obesity; central obesity; smoking status; alcohol drinking; physical activity level; use of multivitamins; menopausal status and hormone therapy in women; intakes of red meat, eggs, and fish; history of diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and NAFLD; and total energy. Dietary covariates were mutually adjusted for other foods and included in the model as the cohort- and sex-specific quintiles. Total energy intake was additionally adjusted for in diet-related analyses. βs indicate the increase or decrease in SD units of betaine on the log scale. Q values represent corrected P values for each group of analyses by controlling the false discovery rate. NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; WHR, waist-to-height ratio.

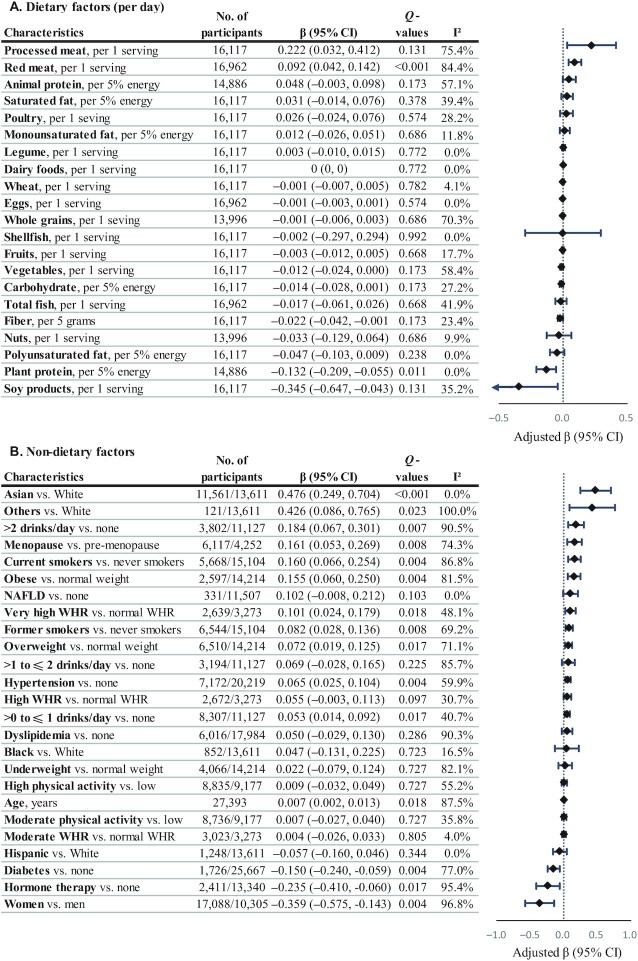

Circulating carnitine was positively associated with intake of red meat (β = 0.092 per 1 serving/d increase) and inversely associated with plant protein (β = −0.132 per 5% energy/d increase; Figure 5 and Supplemental Table 15). Circulating carnitine was positively associated with current and former smoking (β = 0.160 and 0.082), alcohol drinking (β = 0.053 and 0.184 for >0 to ≤1 and >2 drinks/d), overweight and obesity (β = 0.072 and 0.155), very high WHR (β = 0.101), hypertension (β = 0.065), and menopause (β = 0.161) but negatively associated with diabetes (β = −0.150) and hormone therapy (β = −0.235; Figure 5 and Supplemental Table 16). Circulating carnitine was lower in women than in men (β = −0.359) and higher in Asian than in White participants in the US studies (β = 0.476).

FIGURE 5.

Circulating carnitine in relation to dietary (A) and nondietary (B) factors. Regression coefficients (β) and 95% CIs were adjusted for age; sex; ethnicity; fasting time; education; obesity; central obesity; smoking status; alcohol drinking; physical activity level; use of multivitamins; menopausal status and hormone therapy in women; intakes of red meat, eggs, and fish; history of diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and NAFLD; and total energy. Dietary covariates were mutually adjusted for other foods and included in the model as the cohort- and sex-specific quintiles. Total energy intake was additionally adjusted for in diet-related analyses. βs indicate the increase or decrease in SD units of carnitine on the log scale. Q values represent corrected P values for each group of analyses by controlling the false discovery rate. NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; WHR, waist-to-height ratio.

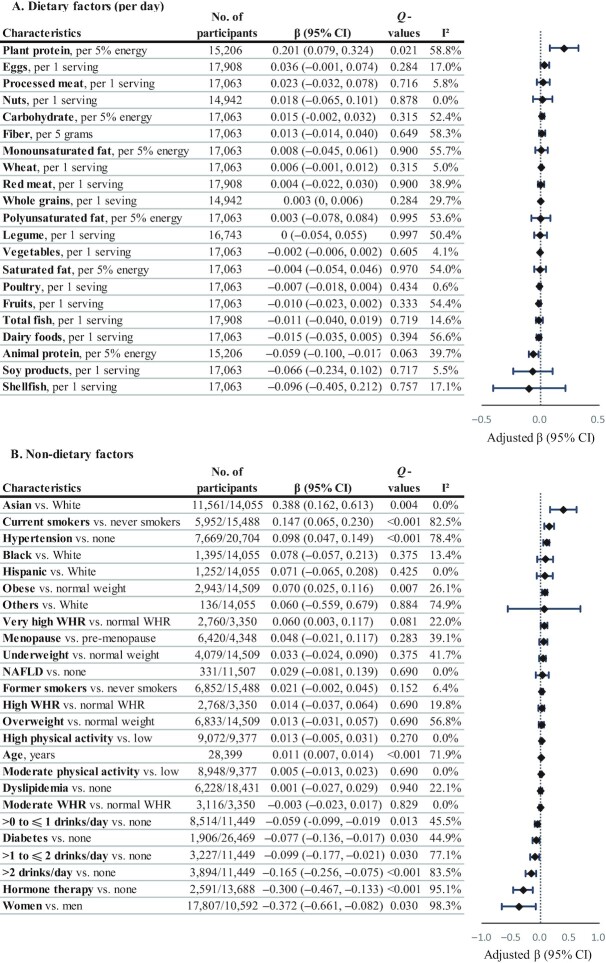

Circulating DMG was positively associated with plant protein (β = 0.201 per 5% energy/d increase), age (β = 0.011 per 1-y increase), current smoking (β = 0.147), obesity (β = 0.070), and hypertension (β = 0.098), but negatively associated with alcohol drinking (β = −0.059, −0.099, and −0.165 for >0 to ≤1, >1 to ≤2, and >2 drinks/d), diabetes (β = −0.077), and hormone therapy (β = −0.300; Figure 6 and Supplemental Tables 17 and 18). Circulating DMG was lower in women than in men (β = −0.372) and higher in Asian than in White participants in the US studies (β = 0.388).

FIGURE 6.

Circulating DMG in relation to dietary (A) and nondietary (B) factors. Regression coefficients (β) and 95% CIs were adjusted for age; sex; ethnicity; fasting time; education; obesity; central obesity; smoking status; alcohol drinking; physical activity level; use of multivitamins; menopausal status and hormone therapy in women; intakes of red meat, eggs, and fish; history of diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and NAFLD; and total energy. Dietary covariates were mutually adjusted for other foods and included in the model as the cohort- and sex-specific quintiles. Total energy intake was additionally adjusted for in diet-related analyses. βs indicate the increase or decrease in SD units of DMG on the log scale. Q values represent corrected P values for each groups of analyses by controlling the false discovery rate. DMG, dimethylglycine; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; WHR, waist-to-height ratio.

Discussion

In this large international pooling project, circulating choline, carnitine, and DMG were associated with an unfavorable cardiometabolic risk profile, while betaine showed a beneficial cardiometabolic risk profile. Circulating choline was positively associated with creatinine, total cholesterol, triglycerides, HbA1c, blood pressure, and CRP. Similarly, circulating carnitine was positively associated with creatinine, an unfavorable blood lipid profile (low HDL and high total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and triglycerides), and homocysteine. DMG was positively associated with creatinine, insulin, CRP, IL-6, and homocysteine, but was inversely associated with total and HDL cholesterol. In contrast, circulating betaine was associated with markers of favorable glycemic control (lower blood glucose and insulin) and lower concentrations of total cholesterol and triglycerides and homocysteine and lower blood pressure.

Our findings were generally consistent with previous reports regarding associations of choline and betaine with cardiometabolic risk factors. Three population-based studies have reported contrasting associations for choline and betaine among >7000 Norwegian adults and nearly 2000 American adults in the Multiethnic Cohort Adiposity Phenotype Study and the Nutrition, Aging, and Memory in Elders cohort (9–11). Across studies, poor lipid profiles were related to higher circulating choline and lower betaine, and higher choline and lower betaine were also suggestively associated with higher blood pressure, poorer glucose control, and higher BMI. Consistent with findings from observational studies (9, 11), phosphatidylcholine supplementation (providing 2.6 g/d of choline) for 2 wk increased serum triglycerides in an analysis of 4 clinical trials (49). However, the same analysis also showed that betaine supplementation of 6 g/d for 6 wk increased total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and triglycerides (49), and another meta-analysis of 6 clinical trials among 233 participants showed that betaine supplementation of >4 g/d for 6–24 wk moderately increased total cholesterol (mean difference of 0.34 mmol/L compared with placebo) (50). Thus, while the triglyceride-increasing effect of choline supplementation has been consistent in observational and intervention studies, the adverse effects of betaine supplementation on blood lipids remain contradictory (51). On the other hand, our finding of a negative association of circulating betaine with homocysteine concentrations was supported by evidence from observational and intervention studies (9, 52). A meta-analysis of 5 clinical trials among 206 healthy adults showed a reduction of 1.23 μmol/L in plasma homocysteine for >4 g/d betaine supplementation for 6–24 wk compared with placebo (52). In another trial among 35 participants with mildly elevated homocysteine, daily supplementation of 6 g betaine for 6 wk decreased plasma homocysteine concentrations by 11% (53). Consistently, a trial among 76 participants with high homocysteine concentrations showed that 1.5, 3, and 6 g/d for 6 wk could reduce fasting plasma homocysteine concentration by 12%, 15%, and 20%, respectively (54), suggesting that a moderate dose of betaine may render substantial homocysteine-lowering effects. Of note, usual dietary intakes of choline are ∼400–600 mg/d and of betaine are ∼200–400 mg/d (55), much lower than the doses used in most clinical trials. In addition, previous observational studies and our current data (Supplemental Table 11) indicated weak correlations between dietary intake and circulating concentrations of choline and betaine (20, 21), which may partially explain conflicting results for dietary choline intake versus circulating choline concentrations in association with cardiometabolic biomarkers (10, 55–57). Thus, caution should be taken when comparing our findings with those from clinical trials or observational studies that evaluated self-reported dietary intakes of choline and betaine. Since prior clinical trials mostly had high doses of supplementation, small sample sizes, and short follow-ups, and observational studies were mostly cross-sectional and could not determine causality, future prospective studies and large trials on sustaining low-dose supplementation are still needed to confirm the associations of choline and betaine with cardiometabolic factors.

Although our pooling analyses showed unfavorable cardiometabolic risk profiles for higher carnitine and DMG, very few studies examined similar topics. In the Multiethnic Cohort Adiposity Phenotype Study, plasma carnitine showed positive associations with higher insulin resistance, poorer blood lipids (higher triglycerides and lower HDL), and higher CRP (11), which was consistent with our findings. While DMG was rarely studied for its relation with cardiometabolic risk factors, it was associated with higher incidence of acute myocardial infarction in patients with stable angina pectoris (58) and total or CVD mortality in patients with coronary artery disease (59). Of note, DMG can be produced from betaine during the remethylation of homocysteine to methionine, which is catalyzed by betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase (5), and the betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase can enhance the hepatic production of VLDL and apolipoprotein-B (60), which are related to atherosclerosis and CVD (61, 62). The collective evidence so far suggests that DMG might be involved in CVD development. Inconsistently, circulating carnitine or DMG concentrations were not associated with most of the glucose control biomarkers or blood pressure in our current study, so the unfavorable cardiometabolic risk profiles associated with circulating carnitine and DMG warrant further examination.

Since choline, betaine, and carnitine are precursors of TMAO (63, 64), whether their cardiometabolic associations were independent of TMAO is worth exploring. In a 3-y follow-up study among 3903 patients undergoing coronary angiography, increased plasma choline and betaine at baseline were associated with incident major adverse cardiac events only when TMAO was also elevated (65), which suggests that the CVD effects of choline and betaine may be modified by TMAO. However, after we further adjusted for TMAO concentrations or antibiotic use (as a proxy of the status of gut microbiota that impacts TMAO), the associations of circulating choline, betaine, and carnitine with cardiometabolic biomarkers were not attenuated substantially. In addition, we did not find statistical evidence of significant effect modifications in analyses stratified by TMAO concentrations. Thus, the observed associations of choline and related metabolites with cardiometabolic biomarkers are, at least in part, independent of TMAO.

Our findings with regard to dietary factors were generally consistent with previous reports. Despite no overall associations in the pooled analyses, we observed significant positive associations of circulating choline with red meat intake among US studies and with egg intake among Asian studies. In our earlier study, while some dietary sources of choline (i.e., red meat and eggs) were common in Chinese, Black Americans, and White Americans, other major dietary sources varied across ethnic groups: poultry and processed meat in Black Americans, dairy and poultry in White Americans, and soy foods and fish in Chinese (14). Similar variations in sources of dietary choline were previously reported in a US multiethnic cohort (15), and variations in dietary choline levels were also noted across countries (16). Circulating betaine was associated with intake of whole grains, carbohydrates, plant protein, and fiber, whereas carnitine was associated with higher red meat intake and lower plant protein intake, which was consistent with the current understanding of their dietary sources (4, 5, 66). Since circulating DMG is a product from betaine (5), its current association with higher plant protein intake might reflect both its plant food source and connection with betaine. As choline and related metabolites can also be endogenously synthesized, the dietary correlations should not be interpreted as causality. Meanwhile, these metabolites were correlated with various nondietary factors in our study, including age; sex; ethnicity; lifestyle factors such as physical activity, smoking, and alcohol drinking; and metabolic conditions such as diabetes, dyslipidemia, and obesity. This suggests that the prior identified associations of these metabolites with cardiometabolic biomarkers could be due to the impact of cardiometabolic conditions on homeostasis of choline and related metabolites, and that the directionality of the associations needs to be validated in prospective studies.

To our knowledge, this is the largest international study on the associations of circulating choline, betaine, carnitine, and DMG with cardiometabolic biomarkers. However, several limitations need to be acknowledged. First, this is a cross-sectional study and could not imply causality nor the directionality of the associations. Although we minimized the reverse causality by excluding prevalent cancer, CVD, chronic kidney disease, and inflammatory bowel disease from our analyses, our findings should still be evaluated in future prospective studies. Second, since our study was a pooling project using data from multiple studies, there existed measurement heterogeneity, errors, and misclassifications associated with different methods for data collection and platforms for biomarker/metabolite measurements. In particular, relative concentrations of choline and related metabolites were measured, so that we could not directly compare their concentrations across studies. We used standardized data harmonization and analytical protocols to minimize potential errors. Third, there could be residual confounding. Given that carnitine was mostly from foods of animal sources while dietary betaine was mostly from plant sources, their concentrations could reflect different lifestyles, whose effects on cardiometabolic risk factors could not be fully adjusted for in statistical models. Finally, our study did not aim to elucidate the underlying mechanisms, but our findings provided evidence that choline and related metabolites are linked to certain cardiometabolic risk factors that could potentially contribute to cardiometabolic disease.

In conclusion, we documented differential associations of circulating choline, betaine, carnitine, and DMG with cardiometabolic risk factors. Circulating choline, carnitine, and DMG were linked to unfavorable cardiometabolic risk profiles, while circulating betaine was related to a favorable cardiometabolic risk profile. Our findings should be validated in future large prospective studies, ideally with clinical cardiometabolic events as the research outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Krista A Zanetti, PhD, MPH, RD (Epidemiology and Genomics Research Program, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, National Cancer Institute, Rockville, MD); Jessica Lasky-Su, ScD (Chair of the COMETS Steering Committee; Channing Laboratory, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA); and Marinella Temprosa, PhD (Vice-Chair of the COMETS Steering Committee; Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Milken Institute School of Public Health, George Washington University, Washington, DC) for their coordination and support in the TMAO Pooling Project.

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—X-OS and DY: designed the study; X-FP and JJY: analyzed the data; X-FP: drafted the manuscript; JJY, X-OS, SCM, NDP, MG-F, DMH, SH, HE, TJW, REG, DA, IT, IK, PE, HZ, LEW, WZ, HC, QC, CEM, CM, KAM, LPL, JO, MF, CMU, and DY: provided critical revisions of the manuscript for important intellectual contents; DY: is the guarantor of the manuscript; and all authors: contributed to the interpretation of the data and read and approved the final manuscript. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Notes

This study was supported by R21 HL140375 and R01 HL149779 to DY from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

The Airwave Health Monitoring Study (AIRWAVE) is funded by the Home Office (grant no. 780-TETRA) with additional support from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Imperial Biomedical Research Centre. PE is Director of the Medical Research Council (MRC)—Public Health England (PHE) Centre for Environment and Health and acknowledges support from the MRC and PHE (MR/L01341X/1). PE acknowledges support from the NIHR Imperial Biomedical Research Centre and the Health Protection Research Unit in Health Impact of Environmental Hazards (HPRU-2012-10141).

The Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention Study (ATBC) is supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) at the NIH.

The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study (CARDIA) is conducted and supported by the NHLBI in collaboration with the University of Alabama at Birmingham (HHSN268201800005I and HHSN268201800007I), Northwestern University (HHSN268201800003I), University of Minnesota (HHSN268201800006I), and Kaiser Foundation Research Institute (HHSN268201800004I). This manuscript has been reviewed and approved by CARDIA for the scientific content.

The Framingham Heart Study (FHS) is supported by contract number HHSN268201500001I from the NHLBI with additional support from other sources. The opinions and conclusions contained in this publication are solely those of the authors and are not endorsed by the FHS or NHLBI and should not be assumed to reflect the opinions or conclusions of either.

The Guangzhou Nutrition and Health Study (GNHS) was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (nos. 81472966, 81273050, and 81472965) and the Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China (no. 2007032).The Health Professionals Follow-Up Study (HPFS) is funded by grants U01 CA167552 and P50 090381 from the NCI.

The Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Family Study (IRASFS) was funded by R01 HL060944 and R01 DK118062 from the NIH.

The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) is supported by contracts HHSN268201500003I, N01-HC-95159, N01-HC-95160, N01-HC-95161, N01-HC-95162, N01-HC-95163, N01-HC-95164, N01-HC-95165, N01-HC-95166, N01-HC-95167, N01-HC-95168, and N01-HC-95169 from the NHLBI, and by grants UL1-TR-000040, UL1-TR-001079, and UL1-TR-001420 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences.

The Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) is funded by grants CA186107 and CA49449, and the NHS II is funded by grants CA176726 and CA067262 from the NCI. MG-F is supported by American Diabetes Association grant #1-18-PMF-029.

The Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial is funded by the NCI. This research also was supported by contracts from the Division of Cancer Prevention of the NCI and by the Intramural Research Program of the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics of the NCI at the NIH.

The Southern Community Cohort Study (SCCS) is funded by grant U01 CA202979 from the NCI at the NIH. Data collection for the Southern Community Cohort Study was performed by the Survey and Biospecimen Shared Resource, which is supported in part by the Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center (P30 CA68485).

The Shanghai Women's Health Study (SWHS) and Shanghai Men's Health Study (SMHS) are funded by grants UM1 CA182910 and UM1 CA173640 from the NCI at the NIH.

The Tsuruoka Metabolomics Cohort Study (TMCS) was supported in part by research funds from the Yamagata Prefectural Government and the city of Tsuruoka and by the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (grants JP24390168 and JP15H04778), Grant-in-Aid for Challenging Exploratory Research (grant 25670303), and Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (grant JP15K19231) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

The Department of Twin Research (TwinsUK) receives support from grants from the Wellcome Trust (212904/Z/18/Z) and the MRC/British Heart Foundation Ancestry and Biological Informative Markers for Stratification of Hypertension (AIMHY; MR/M016560/1), European Union, Chronic Disease Research Foundation (CDRF), Zoe Global Ltd, NIH, and the NIHR-funded BioResource, Clinical Research Facility and Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy's and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in partnership with King's College London. CM is funded by the Chronic Disease Research Foundation and by the MRC Aim-Hy project grant.

The Women's Health Initiative (WHI) is funded by the NHLBI (contracts HHSN268201600018C, HHSN268201600001C, HHSN268201600002C, HHSN268201600003C, HHSN268201600004C, and HHSN268201300008C).

Supplemental Tables 1–18 and Supplemental Figure 1 are available from the “Supplementary data” link in the online posting of the article and from the same link in the online table of contents at https://academic.oup.com/ajcn/.

X-FP and JJY contributed equally to this work.

Abbreviations used: AIRWAVE, Airwave Health Monitoring Study; CRP, C-reactive protein; COMETS, Consortium of Metabolomics Studies; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; DMG, dimethylglycine; FHS, Framingham Heart Study; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; MESA, Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; NHS, Nurses’ Health Study; oz, ounce(s); SBP, systolic blood pressure; SCCS, Southern Community Cohort Study; SMHS, Shanghai Men's Health Study; SWHS, Shanghai Women's Health Study; TMAO, trimethylamine-N-oxide; TMCS, Tsuruoka Metabolomics Cohort Study; WHR, waist-to-hip ratio.

Contributor Information

Xiong-Fei Pan, Division of Epidemiology, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt Epidemiology Center, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA.

Jae Jeong Yang, Division of Epidemiology, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt Epidemiology Center, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA.

Xiao-Ou Shu, Division of Epidemiology, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt Epidemiology Center, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA.

Steven C Moore, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Nicholette D Palmer, Department of Biochemistry, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, USA.

Marta Guasch-Ferré, Department of Nutrition, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

David M Herrington, Section on Cardiology, Department of Internal Medicine, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, USA.

Sei Harada, Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan.

Heather Eliassen, Department of Nutrition, Harvard TH Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA.

Thomas J Wang, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA; Department of Internal Medicine, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA.

Robert E Gerszten, Broad Institute of Harvard and Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Cardiovascular Medicine, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA.

Demetrius Albanes, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Ioanna Tzoulaki, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom; MRC-PHE Centre for Environment and Health, School of Public Health, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom; Dementia Research Institute, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom; Department of Hygiene and Epidemiology, University of Ioannina Medical School, Ioannina, Greece.

Ibrahim Karaman, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom; MRC-PHE Centre for Environment and Health, School of Public Health, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom; Dementia Research Institute, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom.

Paul Elliott, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom; MRC-PHE Centre for Environment and Health, School of Public Health, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom; Dementia Research Institute, Imperial College London, London, United Kingdom.

Huilian Zhu, Department of Nutrition, School of Public Health, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China.

Lynne E Wagenknecht, Public Health Sciences, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, USA.

Wei Zheng, Division of Epidemiology, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt Epidemiology Center, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA.

Hui Cai, Division of Epidemiology, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt Epidemiology Center, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA.

Qiuyin Cai, Division of Epidemiology, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt Epidemiology Center, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA.

Charles E Matthews, Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, USA.

Cristina Menni, Department of Twin Research and Genetic Epidemiology, King's College London, London, United Kingdom.

Katie A Meyer, Department of Nutrition and Nutrition Research Institute, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Kannapolis, NC, USA.

Loren P Lipworth, Division of Epidemiology, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt Epidemiology Center, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA.

Jennifer Ose, Department of Population Health Sciences, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA; Huntsman Cancer Institute, Salt Lake City, UT, USA.

Myriam Fornage, Brown Foundation Institute of Molecular Medicine, McGovern Medical School, University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, TX, USA.

Cornelia M Ulrich, Department of Population Health Sciences, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, USA; Huntsman Cancer Institute, Salt Lake City, UT, USA.

Danxia Yu, Division of Epidemiology, Department of Medicine, Vanderbilt Epidemiology Center, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN, USA.

Data Availability

The data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic codes will be made available upon reasonable request and approval of the corresponding author of the paper and collaborating investigators of each included cohort.

References

- 1.Wortmann SB, Mayr JA. Choline-related-inherited metabolic diseases—a mini review. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2019;42:237–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ueland PM. Choline and betaine in health and disease. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2011;34:3–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeisel SH, da Costa KA. Choline: an essential nutrient for public health. Nutr Rev. 2009;67:615–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flanagan JL, Simmons PA, Vehige J, Willcox MD, Garrett Q. Role of carnitine in disease. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2010;7:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Obeid R. The metabolic burden of methyl donor deficiency with focus on the betaine homocysteine methyltransferase pathway. Nutrients. 2013;5:3481–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fischer LM, da Costa KA, Kwock L, Stewart PW, Lu TS, Stabler SP, Allen RH, Zeisel SH. Sex and menopausal status influence human dietary requirements for the nutrient choline. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:1275–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ueland PM, Holm PI, Hustad S. Betaine: a key modulator of one-carbon metabolism and homocysteine status. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2005;43:1069–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schiattarella GG, Sannino A, Toscano E, Giugliano G, Gargiulo G, Franzone A, Trimarco B, Esposito G, Perrino C. Gut microbe-generated metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide as cardiovascular risk biomarker: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Eur Heart J. 2017;38:2948–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Konstantinova SV, Tell GS, Vollset SE, Nygård O, Bleie Ø, Ueland PM. Divergent associations of plasma choline and betaine with components of metabolic syndrome in middle age and elderly men and women. J Nutr. 2008;138:914–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roe AJ, Zhang S, Bhadelia RA, Johnson EJ, Lichtenstein AH, Rogers GT, Rosenberg IH, Smith CE, Zeisel SH, Scott TM. Choline and its metabolites are differently associated with cardiometabolic risk factors, history of cardiovascular disease, and MRI-documented cerebrovascular disease in older adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;105:1283–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fu BC, Hullar MAJ, Randolph TW, Franke AA, Monroe KR, Cheng I, Wilkens LR, Shepherd JA, Madeleine MM, Le Marchand Let al. Associations of plasma trimethylamine N-oxide, choline, carnitine, and betaine with inflammatory and cardiometabolic risk biomarkers and the fecal microbiome in the Multiethnic Cohort Adiposity Phenotype Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;111:1226–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heianza Y, Ma W, Manson JE, Rexrode KM, Qi L. Gut microbiota metabolites and risk of major adverse cardiovascular disease events and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e004947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer KA, Shea JW. Dietary choline and betaine and risk of CVD: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Nutrients. 2017;9:711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang JJ, Lipworth LP, Shu XO, Blot WJ, Xiang YB, Steinwandel MD, Li H, Gao YT, Zheng W, Yu D. Associations of choline-related nutrients with cardiometabolic and all-cause mortality: results from 3 prospective cohort studies of blacks, whites, and Chinese. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;111:644–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yonemori KM, Lim U, Koga KR, Wilkens LR, Au D, Boushey CJ, Le Marchand L, Kolonel LN, Murphy SP. Dietary choline and betaine intakes vary in an adult multiethnic population. J Nutr. 2013;143:894–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiedeman AM, Barr SI, Green TJ, Xu Z, Innis SM, Kitts DD. Dietary choline intake: current state of knowledge across the life cycle. Nutrients. 2018;10:1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roth GA, Johnson C, Abajobir A, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, Abyu G, Ahmed M, Aksut B, Alam T, Alam Ket al. Global, regional, and national burden of cardiovascular diseases for 10 causes, 1990 to 2015. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:1–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Golden SH, Yajnik C, Phatak S, Hanson RL, Knowler WC. Racial/ethnic differences in the burden of type 2 diabetes over the life course: a focus on the USA and India. Diabetologia. 2019;62:1751–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grundy SM. Metabolic syndrome pandemic. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:629–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zuo H, Svingen GFT, Tell GS, Ueland PM, Vollset SE, Pedersen ER, Ulvik A, Meyer K, Nordrehaug JE, Nilsen DWTet al. Plasma concentrations and dietary intakes of choline and betaine in association with atrial fibrillation risk: results from 3 prospective cohorts with different health profiles. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e008190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abratte CM, Wang W, Li R, Axume J, Moriarty DJ, Caudill MA. Choline status is not a reliable indicator of moderate changes in dietary choline consumption in premenopausal women. J Nutr Biochem. 2009;20:62–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu B, Zanetti KA, Temprosa M, Albanes D, Appel N, Barrera CB, Ben-Shlomo Y, Boerwinkle E, Casas JP, Clish Cet al. The Consortium of Metabolomics Studies (COMETS): metabolomics in 47 prospective cohort studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2019;188:991–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meyer KA, Benton TZ, Bennett BJ, Jacobs DR, Lloyd-Jones DM, Gross MD, Carr JJ, Gordon-Larsen P, Zeisel SH. Microbiota-dependent metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide and coronary artery calcium in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study (CARDIA). J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsao CW, Vasan RS. Cohort profile: the Framingham Heart Study (FHS): overview of milestones in cardiovascular epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:1800–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilson KM, Kasperzyk JL, Rider JR, Kenfield S, van Dam RM, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci E, Mucci LA. Coffee consumption and prostate cancer risk and progression in the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:876–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wagenknecht LE, Mayer EJ, Rewers M, Haffner S, Selby J, Borok GM, Henkin L, Howard G, Savage PJ, Saad MFet al. The Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study (IRAS) objectives, design, and recruitment results. Ann Epidemiol. 1995;5:464–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Burke GL, Detrano R, Diez Roux AV, Folsom AR, Greenland P, Jacob DR Jr, Kronmal R, Liu Ket al. Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis: objectives and design. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:871–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bao Y, Bertoia ML, Lenart EB, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Speizer FE, Chavarro JE. Origin, methods, and evolution of the three Nurses' Health Studies. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:1573–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu CS, Pinsky PF, Kramer BS, Prorok PC, Purdue MP, Berg CD, Gohagan JK. The Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial and its associated research resource. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1684–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Signorello LB, Hargreaves MK, Blot WJ. The Southern Community Cohort Study: investigating health disparities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21:26–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Women's Health Initiative Study Group . Design of the Women's Health Initiative clinical trial and observational study. Control Clin Trials. 1998;19:61–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elliott P, Vergnaud AC, Singh D, Neasham D, Spear J, Heard A. The Airwave Health Monitoring Study of police officers and staff in Great Britain: rationale, design and methods. Environ Res. 2014;134:280–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.ATBC Cancer Prevention Study Group . The Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta-Carotene Lung Cancer Prevention Study: design, methods, participant characteristics, and compliance. Ann Epidemiol. 1994;4:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moayyeri A, Hammond CJ, Valdes AM, Spector TD. Cohort profile: TwinsUK and Healthy Ageing Twin Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:76–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen YM, Liu Y, Zhou RF, Chen XL, Wang C, Tan XY, Wang LJ, Zheng RD, Zhang HW, Ling WHet al. Associations of gut-flora-dependent metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide, betaine and choline with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in adults. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shu XO, Li H, Yang G, Gao J, Cai H, Takata Y, Zheng W, Xiang YB. Cohort profile: the Shanghai Men's Health Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:810–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zheng W, Chow WH, Yang G, Jin F, Rothman N, Blair A, Li HL, Wen W, Ji BT, Li Qet al. The Shanghai Women's Health Study: rationale, study design, and baseline characteristics. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:1123–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Harada S, Takebayashi T, Kurihara A, Akiyama M, Suzuki A, Hatakeyama Y, Sugiyama D, Kuwabara K, Takeuchi A, Okamura Tet al. Metabolomic profiling reveals novel biomarkers of alcohol intake and alcohol-induced liver injury in community-dwelling men. Environ Health Prev Med. 2016;21:18–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yang JJ, Shu XO, Herrington DM, Moore SC, Meyer KA, Ose J, Menni C, Palmer ND, Eliassen H, Harada Set al. Circulating trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) in association with diet and cardiometabolic biomarkers: an international pooled analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021. Apr 7;nqaa430. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqaa430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holm PI, Ueland PM, Kvalheim G, Lien EA. Determination of choline, betaine, and dimethylglycine in plasma by a high-throughput method based on normal-phase chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Clin Chem. 2003;49:286–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mayers JR, Wu C, Clish CB, Kraft P, Torrence ME, Fiske BP, Yuan C, Bao Y, Townsend MK, Tworoger SSet al. Elevation of circulating branched-chain amino acids is an early event in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma development. Nat Med. 2014;20:1193–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soga T, Igarashi K, Ito C, Mizobuchi K, Zimmermann HP, Tomita M. Metabolomic profiling of anionic metabolites by capillary electrophoresis mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2009;81:6165–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.da Costa KA, Vrbanac JJ, Zeisel SH. The measurement of dimethylamine, trimethylamine, and trimethylamine N-oxide using capillary gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 1990;187:234–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tzoulaki I, Castagne R, Boulange CL, Karaman I, Chekmeneva E, Evangelou E, Ebbels TMD, Kaluarachchi MR, Chadeau-Hyam M, Mosen Det al. Serum metabolic signatures of coronary and carotid atherosclerosis and subsequent cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:2883–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Evans AM, Bridgewater B, Liu Q, Mitchell M, Robinson R, Dai H, Stewart S, DeHaven C, Miller L. High resolution mass spectrometry improves data quantity and quality as compared to unit mass resolution mass spectrometry in high-throughput profiling metabolomics. Metabolomics. 2014;4:1000132. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Willett WC, Howe GR, Kushi LH. Adjustment for total energy intake in epidemiologic studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;65:1220S–8S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Series B Stat Methodol. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Olthof MR, van Vliet T, Verhoef P, Zock PL, Katan MB. Effect of homocysteine-lowering nutrients on blood lipids: results from four randomised, placebo-controlled studies in healthy humans. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zawieja EE, Zawieja B, Chmurzynska A. Betaine supplementation moderately increases total cholesterol levels: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Diet Suppl. 2019:1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zeisel SH. Betaine supplementation and blood lipids: fact or artifact?. Nutr Rev. 2006;64:77–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McRae MP. Betaine supplementation decreases plasma homocysteine in healthy adult participants: a meta-analysis. J Chiropract Med. 2013;12:20–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Steenge GR, Verhoef P, Katan MB. Betaine supplementation lowers plasma homocysteine in healthy men and women. J Nutr. 2003;133:1291–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Olthof MR, van Vliet T, Boelsma E, Verhoef P. Low dose betaine supplementation leads to immediate and long term lowering of plasma homocysteine in healthy men and women. J Nutr. 2003;133:4135–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dalmeijer GW, Olthof MR, Verhoef P, Bots ML, van der Schouw YT. Prospective study on dietary intakes of folate, betaine, and choline and cardiovascular disease risk in women. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2008;62:386–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Detopoulou P, Panagiotakos DB, Antonopoulou S, Pitsavos C, Stefanadis C. Dietary choline and betaine intakes in relation to concentrations of inflammatory markers in healthy adults: the ATTICA study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:424–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chiuve SE, Giovannucci EL, Hankinson SE, Zeisel SH, Dougherty LW, Willett WC, Rimm EB. The association between betaine and choline intakes and the plasma concentrations of homocysteine in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:1073–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Svingen GF, Ueland PM, Pedersen EK, Schartum-Hansen H, Seifert R, Ebbing M, Loland KH, Tell GS, Nygard O. Plasma dimethylglycine and risk of incident acute myocardial infarction in patients with stable angina pectoris. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33:2041–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Svingen GF, Schartum-Hansen H, Ueland PM, Pedersen ER, Seifert R, Ebbing M, Bonaa KH, Mellgren G, Nilsen DW, Nordrehaug JEet al. Elevated plasma dimethylglycine is a risk marker of mortality in patients with coronary heart disease. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2015;22:743–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sparks JD, Collins HL, Chirieac DV, Cianci J, Jokinen J, Sowden MP, Galloway CA, Sparks CE. Hepatic very-low-density lipoprotein and apolipoprotein B production are increased following in vivo induction of betaine-homocysteine S-methyltransferase. Biochem J. 2006;395:363–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Contois JH, McConnell JP, Sethi AA, Csako G, Devaraj S, Hoefner DM, Warnick GR; AACC Lipoproteins and Vascular Diseases Division Working Group on Best Practices . Apolipoprotein B and cardiovascular disease risk: position statement from the AACC Lipoproteins and Vascular Diseases Division Working Group on Best Practices. Clin Chem. 2009;55:407–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pechlaner R, Tsimikas S, Yin X, Willeit P, Baig F, Santer P, Oberhollenzer F, Egger G, Witztum JL, Alexander VJet al. Very-low-density lipoprotein-associated apolipoproteins predict cardiovascular events and are lowered by inhibition of APOC-III. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:789–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Koeth RA, Wang Z, Levison BS, Buffa JA, Org E, Sheehy BT, Britt EB, Fu X, Wu Y, Li Let al. Intestinal microbiota metabolism of L-carnitine, a nutrient in red meat, promotes atherosclerosis. Nat Med. 2013;19:576–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang Z, Klipfell E, Bennett BJ, Koeth R, Levison BS, Dugar B, Feldstein AE, Britt EB, Fu X, Chung YMet al. Gut flora metabolism of phosphatidylcholine promotes cardiovascular disease. Nature. 2011;472:57–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang Z, Tang WH, Buffa JA, Fu X, Britt EB, Koeth RA, Levison BS, Fan Y, Wu Y, Hazen SL. Prognostic value of choline and betaine depends on intestinal microbiota-generated metabolite trimethylamine-N-oxide. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:904–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Meslier V, Laiola M, Roager HM, De Filippis F, Roume H, Quinquis B, Giacco R, Mennella I, Ferracane R, Pons Net al. Mediterranean diet intervention in overweight and obese subjects lowers plasma cholesterol and causes changes in the gut microbiome and metabolome independently of energy intake. Gut. 2020;69:1258–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic codes will be made available upon reasonable request and approval of the corresponding author of the paper and collaborating investigators of each included cohort.