Abstract

Background

Cranial radiation therapy (CRT) is a mainstay of treatment for malignant pediatric brain tumors and high-risk leukemia. Although CRT improves survival, it has been shown to disrupt normal brain development and result in cognitive impairments in cancer survivors. Animal studies suggest that there is potential to promote brain recovery after injury using metformin. Our aim was to evaluate whether metformin can restore brain volume outcomes in a mouse model of CRT.

Methods

C57BL/6J mice were irradiated with a whole-brain radiation dose of 7 Gy during infancy. Two weeks of metformin treatment started either on the day of or 3 days after irradiation. In vivo magnetic resonance imaging was performed prior to irradiation and at 3 subsequent time points to evaluate the effects of radiation and metformin on brain development.

Results

Widespread volume loss in the irradiated brain appeared within 1 week of irradiation with limited subsequent recovery in volume outcomes. In many structures, metformin administration starting on the day of irradiation exacerbated radiation-induced injury, particularly in male mice. Metformin treatment starting 3 days after irradiation improved brain volume outcomes in subcortical regions, the olfactory bulbs, and structures of the brainstem and cerebellum.

Conclusions

Our results show that metformin treatment has the potential to improve neuroanatomical outcomes after CRT. However, both timing of metformin administration and subject sex affect structure outcomes, and metformin may also be deleterious. Our results highlight important considerations in determining the potential benefits of metformin treatment after CRT and emphasize the need for caution in repurposing metformin in clinical studies.

Keywords: metformin, MRI, neurodevelopment, neurogenesis, radiation

Key Points.

1. Radiation causes brain structure volume loss.

2. Metformin treatment can promote brain growth and partially normalize volume outcomes.

3. The effects of metformin are strongly dependent on timing of administration and sex.

Importance of the Study.

At present, there are no treatments available to prevent or ameliorate radiation-induced cognitive impairments in pediatric brain cancer survivors. Previous studies demonstrate that radiation-induced cognitive impairments are associated with neuroanatomical changes. Early intervention aimed at normalizing outcomes by promotion of post-irradiation recovery is needed as CRT will continue to remain an important component of cancer treatment. In this study, we treated irradiated mice with metformin and demonstrated that, under the right circumstances, metformin can be effective at improving neuroanatomical outcomes. However, its benefit is limited (or even detrimental for males) when administered immediately after irradiation. Our findings highlight the need to distinguish conditions in which metformin is beneficial from conditions in which it may pose a risk for individual childhood cancer survivors.

Cranial radiation therapy (CRT) is a mainstay of treatment for primary pediatric brain tumors that have a propensity for dissemination and for cancers metastatic to the brain. Although CRT improves long-term survival, it has been shown to disrupt normal brain development and is a major contributor to neuropsychological late effects, adverse outcomes that impair cognition months to years following treatment. Affected cognitive domains include memory, processing speed, attention, and executive function.1–6 Neuropsychological impairments negatively impact academic performance, social function, and future vocational opportunities.3,6 Prevention or amelioration of late effects is thus of great importance to enhance childhood cancer survivors’ quality of life.

The activation of endogenous neural precursor cells (NPCs) is an attractive strategy for promoting repair of the injured brain,7 an effect explored most extensively in the NPC niche of the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. Radiation treatment induces decreased proliferative and altered differentiation activity in NPCs of the hippocampus in mouse models,8 an effect that seems evident in the human hippocampus as well.9 However, despite the high sensitivity of NPCs to radiation,10 several reports support the idea that sparing of NPCs or promotion of neurogenesis after injury may improve or preserve cognitive function.11–13 For instance, anti-inflammatory treatment with indomethacin or knockout of genes encoding immunomodulating inflammatory cytokine or their receptors can modulate neurogenesis in animal models.14–16 Since neurogenesis in the human hippocampus is extensive at birth but decreases substantially over the first decade of life, childhood may provide a unique and limited window of opportunity to realize the benefits of such neurogenic interventions.17,18 While various agents have been examined for their ability to enhance this neurogenic response,7 there has been particular interest in the oral antidiabetic medication metformin.

Metformin has multiple effects that may be beneficial for the brain. It has been shown to promote neurogenesis,11–13,19–22 oligodendrogenesis,21,23,24 and angiogenesis20,22,25 and has been reported to reduce inflammation, attenuate brain atrophy, and improve functional recovery in rodent models of stroke.12,19–22,25,26 It may act as a radioprotector when administered close to the time of radiation27,28 and has thus been explored for limitation of cardiac, pulmonary, and skin toxicities.29 More recently, metformin administration starting 1 day after radiation was found to promote recovery of the endogenous neural progenitor cell population in the dentate gyrus, which translated to improvements in working memory.13 A concurrent clinical study suggested improvements in memory encoding in children treated with metformin starting at least 2 years post-CRT.13

In this study, our aim was to evaluate the impact of metformin on brain structure through development in a mouse model of pediatric CRT. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) measurements enable high-throughput in vivo measurements that cover the whole brain, correlate with behaviour30,31 and have relevance across species.32,33 These structural analyses supplement previous studies by characterizing the longitudinal progression of treatment effects through development and by evaluating impact across the whole brain.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Treatments

C57BL/6J mice (Centre for Phenogenomics in-house colony, Toronto, ON, Canada) were used for all experiments. Animal protocols were approved by the Centre for Phenogenomics Animal Care Committee. Juvenile mice were either sham-treated (0 Gy) or irradiated (7 Gy) at postnatal day 16 (P16), which corresponds to early childhood in humans. In preparation, mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal (IP) injection of ketamine (75 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg). Control mice (sham-treated, 0 Gy) were also anesthetized but otherwise left to recover. A single dose of 7 Gy was delivered to the head at 0.678 Gy/min using a Cs-137 source (Gammacell® 40 Extractor, Best Theratronics Ltd., Ottawa, ON, Canada). Lead shielding was used to cover the body.34 Assuming a fractionation sensitivity of α/β = 2 Gy, this dose is approximately equivalent to a dose of 16 Gy delivered in 2-Gy fractions.35

Two different metformin treatment paradigms were explored. In both cases, mice were injected subcutaneously with 100 mg/kg metformin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) once daily for 14 days. This dose was based on previous reports indicating 20-200 mg/kg can promote neurogenesis and brain repair,20,21 and on pilot studies that showed it was well tolerated. The first group (MET16) of mice received metformin starting on the day of irradiation (immediately following CRT) and continuing for 2 weeks. Based on our own initial findings in the MET16 mice and motivated by reports that metformin effects are dependent on timing of drug delivery,19,26 a second group of mice (MET19) was prepared that received metformin by the same procedure but starting at P19. The 3-day delay was considered sufficient to allow acute effects of radiation to pass, including apoptosis of NPCs and oligodendrocytes (~24 hours return to baseline)10,36 and elevations of pro-inflammatory mediators (48-72 hours return to baseline).37 For both groups, vehicle-treated mice (VEH) were injected with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Sigma-Aldrich).

The total number of mice (females = F) in the cohorts included:

MET16: 21 (0 Gy-VEH, 10 F), 23 (7 Gy-VEH, 12 F), 20 (0 Gy-MET16, 11 F), and 22 (7 Gy-MET16, 12 F);

MET19: 21 (0 Gy-VEH, 10 F), 23 (7 Gy-VEH, 12 F), 21 (0 Gy-MET19, 10 F), and 24 (7 Gy-MET19, 11 F).

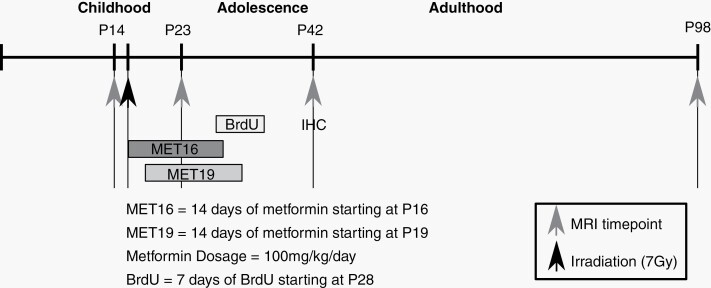

The VEH control groups were pooled after confirming no difference between them. Figure 1 summarizes the time course of experiments and study parameters for both paradigms.

Fig. 1.

Timeline for studying the effect of radiation and metformin-induced neuroanatomical changes. Approximate human-equivalent ages are depicted above the timeline. Mice were irradiated at P16. Metformin MET16 or MET19 was administered for 14 days, starting on P16 or P19, respectively. In vivo MRI was performed on P14, P23, P42, and P98. BrdU was administered for 7 days, starting on P28, and mice were perfused on P42 in preparation for immunohistochemistry (IHC). Abbreviations: MET16, treated with metformin starting at P16; MET19, treated with metformin starting at P19; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

In Vivo Longitudinal MRI

In vivo MRI scans were acquired on a 7-Tesla scanner (Bruker BioSpin, Ettlingen, Germany) with a T1-weighted gradient-echo sequence. Up to 4 mice were scanned simultaneously at an isotropic resolution of 75 µm, TE/TR = 8.1/32 ms, flip angle = 26°, 2 averages, and a total scan time of 1 hour. To enhance contrast, mice received 0.4 mmol/kg MnCl2 (Sigma-Aldrich) via IP injection 24 hours prior to scanning.38 Throughout the scan, mice were anesthetized with a constant source of 1% isoflurane. Imaging was performed at P14 (prior to irradiation), P23, P42, and P98. The P14 time point provided baseline volume measures to account for variability between mice. The P23 time point measured early volume loss following irradiation. The P42 and P98 time points evaluated developmental trajectories into adulthood.

Image Analysis

To quantify anatomical differences between images, an automated registration process39,40 was used to align them in a consensus average space with point-by-point correspondence between images. An atlas containing segmentations of 159 structures41–43 was then aligned to the consensus average. The Jacobian determinants of the individual deformation fields were used to calculate voxel-wise volume differences relative to the average. Volumes for individual anatomic structures for each image were then calculated by summation of the volume of all voxels within each structure. In vivo volumes were fit for each structure using a linear mixed-effects model.44 Fixed-effect coefficients were included to account for: age, sex, post-irradiation volume change, irradiation-induced change in growth (modeled as linear in age), metformin treatment-induced volume change, metformin treatment-induced change in growth (linear in age), and interactions between them. The sex coefficient was defined so that volume estimates were referenced to the average male-female values. The reference age of the linear terms was adjusted for convenience so that the intercept coefficients represented differences at either the P23 or the P98 time point. A random offset was included in the model for each mouse to account for biological variability. The full model is shown explicitly in the Supplementary material. P values were calculated for each coefficient by estimating degrees of freedom using the Satterthwaite approximation,45 and the influence of multiple comparisons was controlled through the false discovery rate (FDR).46 Although statistical significance in all cases was established based on this model, the following plots were utilized for visualization purposes: volume vs age (showing full-time course), volume difference between P23 and P14 (showing early treatment effects, 1 week after CRT), volume difference between P98 and P23 (emphasizing volume change due to growth), and final volume at P98 (emphasizing adult outcomes).

Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry

Hippocampal neurogenesis and oligodendrogenesis were studied by birth-dating using a BrdU injection paradigm. BrdU (50 mg/kg, Sigma-Aldrich) was administered through IP injection once daily starting on P28 for 7 days, overlapping with the end of metformin treatment. One week after the last injection, mice were perfused using saline and 4% paraformaldehyde under deep anesthesia as previously described.47,48 Mouse brains were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and cryoprotected in a 30% sucrose solution.

For BrdU and NeuN histochemistry, coronal sections that contained the hippocampus between −1.34 mm and −3.40 mm, relative to the bregma,49 were cut at 40-µm thickness and collected in tissue cryoprotectant solution in 96-well plates and stored at −20°C. Floating sections were washed in PBS, treated with 2 N HCl and 0.1 M borate buffer (pH 8.5). They were then incubated with antibodies against BrdU (1:100; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA; cat# ab6326) and NeuN (1:400, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA; cat# MAB3777) in 2% donkey serum in PBS at 4°C overnight. BrdU and NeuN labeling was revealed by secondary antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (1:200, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Ontario, Canada; cat# A-11006) and Alexa Fluor 568 (1:200, Thermo Fisher Scientific; cat# A-11004), respectively. Sections were counterstained with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Co-localization of BrdU and NeuN was evaluated using a confocal laser scanning microscope (Zeiss LSM 510, Oberkochen, Germany).

To evaluate newly born and proliferating oligodendrocytes or oligodendrocyte precursor cells, BrdU and Olig2 histochemistry was conducted in a floating section from each mouse at −1.34 mm relative to the bregma. Sections were washed with PBS buffer 3 times for 5 minutes each in 24-well plates, followed by treatment in 2 N HCl at room temperature for 45 minutes, and then in 0.1 M borate buffer for 10 minutes. After washing in PBS, the sections were incubated with antibodies for BrdU (1:200, Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) and Olig2 (1:25, Novus Biologicals, Oakville, ON, Canada) at 4°C overnight and then at room temperature for 2 hours. Antibodies conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (1:200, Life Technologies, Burlington, ON, Canada) and Alexa Fluor 568 (1:200, Life Technologies) were used to reveal immunoreactivity, and sections were counterstained with DAPI.

Stereological Analysis

BrdU- and BrdU/NeuN-labeled cells were counted within the granular cell layer of the right and left dentate gyrus including a 50-µm hilar margin of the subgranular zone.8 Cell counting was performed using Zeiss Imager M1 microscope with Stereo Investigator software (MicroBrightField, Williston, VT, USA). The observer was blinded to treatment condition. Cells were counted using a counting frame and a sampling grid of 75 × 75 µm at a magnification of ×63. Six sections at every seventh section interval from each animal were used as the periodicity of sections sampled. The estimated number of the target cells in at least 3 animals was calculated as the mean of the number of cells in the right and left dentate gyrus of the mouse brain. The coefficient of error was 0.03-0.06 in all stereological studies. The number of Olig2-positive cells labeled with BrdU was estimated within the corpus callosum50 using a counting frame and sampling grid of 75 × 75 µm. Estimated cell density was derived from the mean of the number of target cells in the corpus callosum per cubic millimeter. Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a post hoc Bonferroni-corrected Student t test was used to compare counts and establish the significance of treatment. Statistical analyses of histological data were performed using GraphPad Prism 4 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

Results

Irradiation Leads to Widespread Volume Loss in the Brain

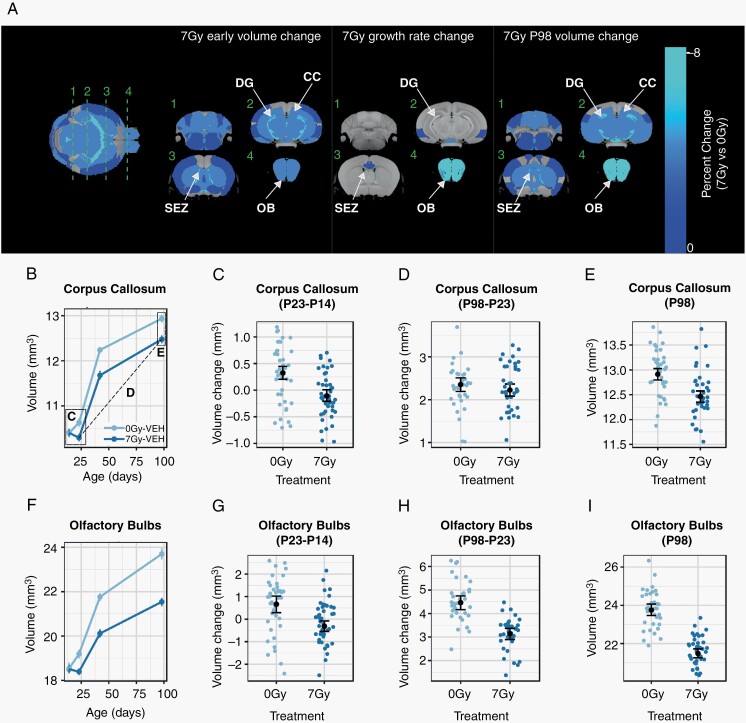

Following CRT at P16, neuroanatomical development in mice was assessed through in vivo longitudinal imaging on P14, P23, P42, and P98, with results summarized graphically in Figure 2A. An early volume difference was observed between sham and irradiated mice already by P23 (Figure 2A, left) and was considered significant in 107 of the 159 segmented structures (FDR <10%), constituting a majority of the brain. Comparisons for all structures are provided in Supplementary Table S1. We further evaluated changes in growth rate and volume outcomes at P98 (Figure 2A, middle and right columns, respectively). A decrease in growth rate, resulting in a progressive volume deficit, was also observed in the mammillary bodies, subependymal zone, lateral olfactory tract, olfactory bulbs, and regions of the cingulate and entorhinal cortices.

Fig. 2.

Widespread volume reduction in the mouse brain after irradiation at P16. In (A), an average in vivo MRI image is shown at left, with a color overlay indicating the early volume change (ie, the volume difference between 7 Gy and 0 Gy observed at P23) in all regions considered statistically significant (FDR <10%). Green lines indicate the location of orthogonal slices shown in the subsequent columns, which show the early volume change, the total change in growth rate over the post-irradiation (75-day) period, and the P98 change (ie, the difference between 7 Gy and 0 Gy observed at P98). Individual plots show the volume of the corpus callosum and olfactory bulbs over time (B, F), along with plots likewise demonstrating the early volume change as the volume change between P23 and P14 (C, G) and long-term volume change as the volume change between P98 and P23 (D, H). To visualize the endpoint volume outcomes, the final P98 volumes were plotted (E, I). Annotations in B indicate the relationships between the plots. The individual points in (B, F) and black means in (C–E, G–I) represent averages across sex. Points and error bars represent the mean volume and bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals. Smaller colored dots (C–E, G–I) represent structure volumes from individual mice. Abbreviations: 0 Gy, sham-treated; 7 Gy, irradiated; CC, corpus callosum; DG, dentate gyrus; OB, olfactory bulbs; SEZ, subependymal zone; VEH, vehicle-treated mice (ie, no metformin treatment).

Figure 2B–I show sample plots for the corpus callosum and olfactory bulbs. The corpus callosum (Figure 2B–E), demonstrated a significant early volume loss as visualized by the P23-P14 volume difference (Figure 2C) but no long-term change in growth over the P23-P98 period (Figure 2D), resulting in persistent volume deficits at P98 (Figure 2E). Most structures showed this pattern, resulting in volumes smaller than controls through P98. The olfactory bulbs (Figure 2F–I) exhibited the greatest volume change, finishing at an 8% smaller total volume in 7-Gy mice than in 0-Gy controls (Figure 2I), with both a P23 volume loss (Figure 2G) and decreased growth between P23 and P98 (Figure 2H) contributing to the outcome. Regions dependent on adult neurogenesis, namely the dentate gyrus, subependymal zone, and olfactory bulbs, were prominently affected at P98. We also observed increased female vulnerability to radiation, as evidenced by slightly larger volume loss at P23 in females for some structures (Supplementary Figure S1), consistent with risk factors noted in patients and previous results.32

Metformin Promotes Growth in the Unirradiated Brain

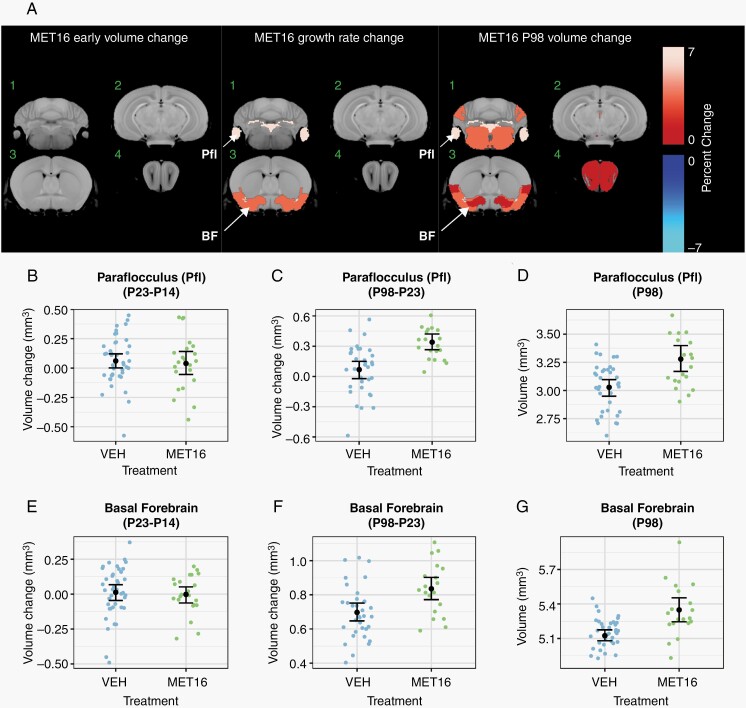

To investigate metformin influences on brain development, 100 mg/kg/d was delivered subcutaneously at P16 (MET16) or P19 (MET19) for 14 days. For the 0 Gy-MET16 treatment group, metformin treatment resulted in no significant volume changes at P23 (Figure 3A, B, and E). Over the course of development, metformin treatment enhanced the growth rate of some brain regions, including the paraflocculus of the cerebellum (0.08%/d, +6% at P98, Figure 3B–D) and the basal forebrain (0.04%/d, +3% at P98, Figure 3E–G). Additional volume increases in the midbrain and olfactory bulbs became evident at P98, suggesting that metformin treatment produced a sustained change into early adulthood. More restricted and smaller magnitude trends were observed when metformin treatment was started on P19 (MET19, Supplementary Figure S2).

Fig. 3.

Increased growth during brain development due to metformin in unirradiated mice. In (A), a color map overlay shows all structures that had a significant volume difference in MET16-treated mice compared to vehicle-treated mice (FDR <10%). Slice positions in (A) match those in Figure 2. There was no effect of MET16 on the brain in 0-Gy mice at P23 (early). Subsequently, enhanced growth rate was observed in regions of the cerebellum, basal forebrain, and piriform cortex, leading to increased volumes by P98 (A). Representative plots of the paraflocculus (B–D) and basal forebrain (E–G) show no significant early volume change as visualized by the P23-P14 volume difference in (B, E). Growth rate and P98 change (A) is significantly increased in both structures, as shown by the P98-P23 volume differences (C, F). This results in increased volume by the final P98 time point (D, G). Treatment effects within the fitted model are represented as the average of males and females. Black points and error bars represent the mean volume and bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals. Smaller colored dots represent structure volumes from individual mice. Abbreviations: BF, basal forebrain; MET16, treated with metformin starting at P16, for 14 days; Pfl, paraflocculus.

Metformin Treatment Can Exacerbate Volume Loss or Promote Recovery in the Irradiated Brain

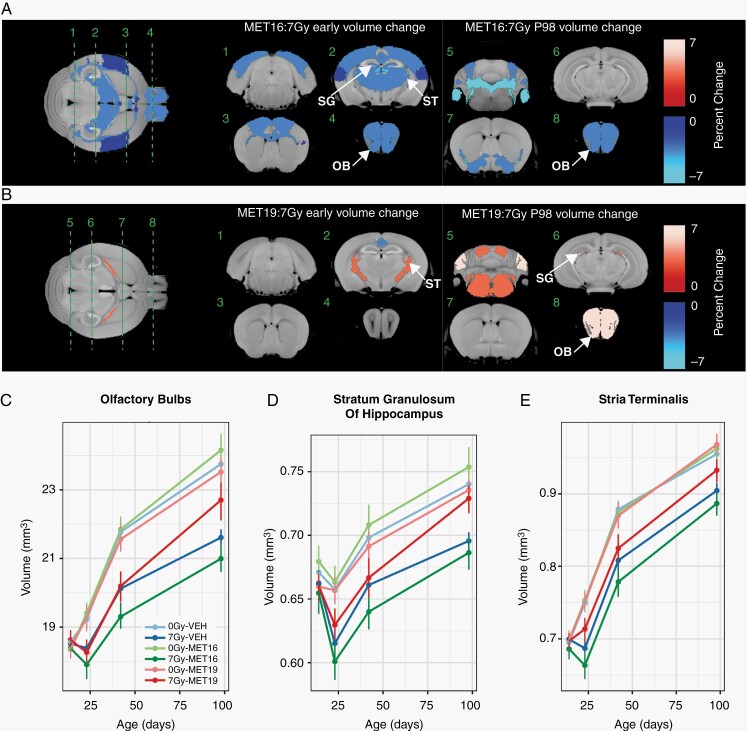

To determine the effect of metformin treatment on radiation-induced volume changes, we investigated the volume time course in metformin-treated, irradiated mice and evaluated the interaction effect of metformin and radiation treatment. After metformin treatment starting at P16 (MET16), P23 volume losses induced by radiation were exacerbated in 40 of the 159 segmented structures (Figure 4A). Affected regions were widespread and included the cortex, prominent white matter regions, and regions linked with neurogenesis (the dentate gyrus, subependymal zone, and olfactory bulbs). This finding indicates a potentially detrimental effect of metformin when administered at the time of irradiation. The volume loss persisted in many structures through P98 (Figure 4A, right column).

Fig. 4.

Metformin treatment effects in the irradiated brain depend on timing of administration. Early (P23) and late (P98) outcomes of MET16 (A) and MET19 (B) metformin treatments were assessed. Metformin-radiation interaction terms in the linear mixed-effects model were used to identify significantly altered regions (with interaction coefficients denoted as MET16:7 Gy and MET19:7 Gy). In (A), the color map shows all structures that had a significant volume difference in (A) irradiated MET16-treated mice or (B) irradiated MET19-treated mice (MET19:7 Gy), compared to controls (FDR of 10%). In (C, D, E), plots depict volumes of the olfactory bulbs, stratum granulosum, and stria terminalis, over time in unirradiated vehicle-treated mice (0 Gy-VEH), irradiated vehicle-treated mice (7 Gy-VEH), unirradiated MET16- or MET19-treated mice (0 Gy-MET16 or 0 Gy-MET19), and irradiated MET16 or MET19-treated mice (7 Gy-MET16 or 7 Gy-MET19). An exacerbation of radiation-induced volume loss was observed in 7 Gy-MET16 mice. In contrast, a partial mitigation of radiation-induced volume loss was observed in 7 Gy-MET19 mice. Points and error bars represent the mean volume and bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals. Abbreviations: 0 Gy, unirradiated; 7 Gy, irradiated with a 7 Gy dose; MET16, treated with metformin starting at P16; MET19, treated with metformin starting at P19; OB, olfactory bulbs; SG, stratum granulosum of hippocampus; ST, stria terminalis.

In contrast to the MET16 group, the MET19 group showed several regions where metformin treatment was considered beneficial. In this group, the exacerbated volume loss after radiation observed was largely eliminated. A few regions even exhibited an improved P23 volume outcome (Figure 4B, left column), such as the stria terminalis (Figure 4B and E). More extensive volume increases were observed at P98, with volume increases in regions impacted by neurogenesis such as the stratum granulosum of the hippocampus and the olfactory bulbs. Representative plots (Figure 4C, D, and E) show that MET19 treatment partly mitigated the significant volume loss induced by CRT in the olfactory bulbs (Figure 4C), stratum granulosum (Figure 4D), and stria terminalis (Figure 4E). These findings indicate that metformin treatment, if administered with appropriate timing, promotes enhanced structural development after irradiation in some brain regions.

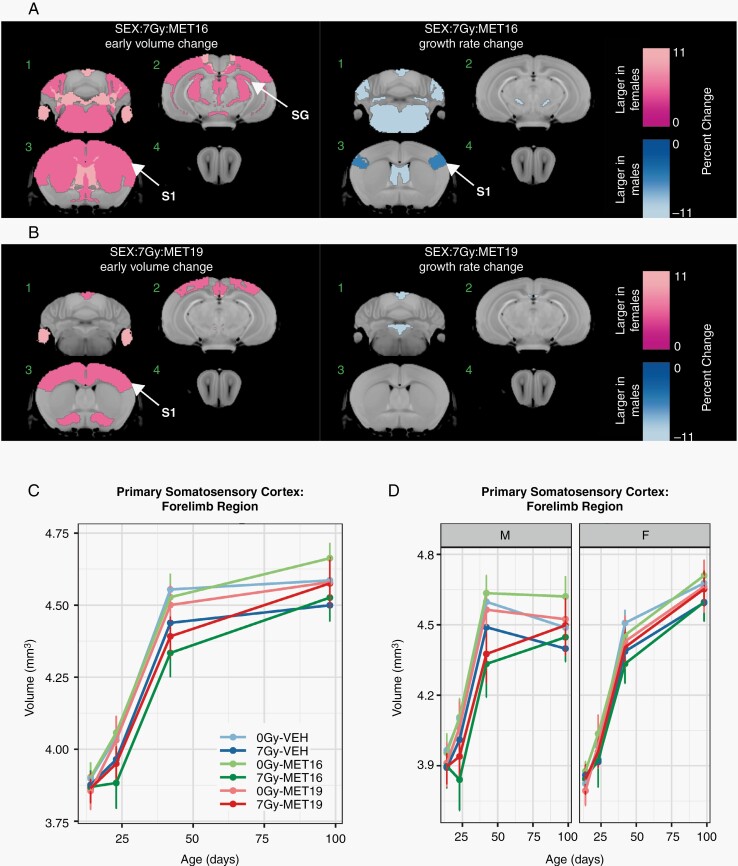

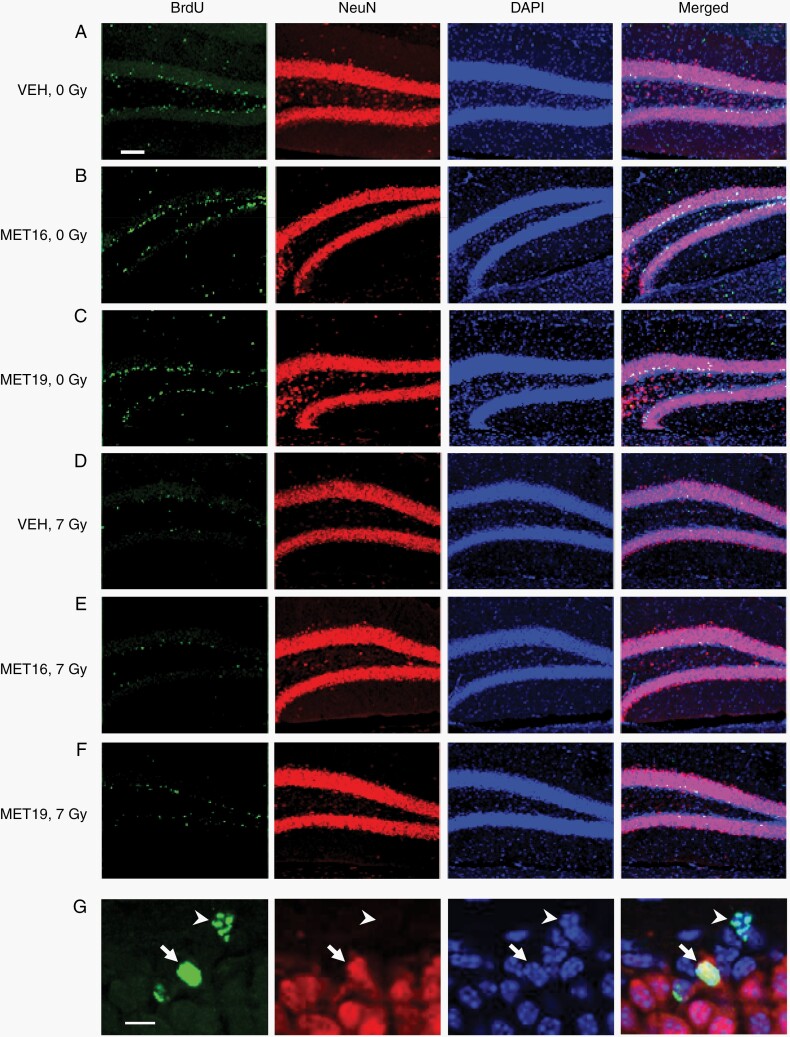

Metformin Treatment Effects Following Irradiation Are Strongly Sex-Dependent

To investigate the role that biological sex plays in volume time courses after metformin and radiation treatment, the effect of a sex-radiation-metformin interaction term in our mixed-effects model was evaluated. This revealed that several regions were relatively smaller at P23 in irradiated metformin-treated male mice compared to the irradiated metformin-treated female mice (Figure 5A and B). This was true for both timings of metformin administration, although the MET16 timing (Figure 5A) appeared to show more widespread differences. On the other hand, several affected structures also showed greater growth rates in metformin-treated, irradiated males compared to females (Figure 5A and B, right column). Representative plots of the primary somatosensory cortex (forelimb region) and stratum granulosum are provided in Figure 5C–F. When separated by sex, the early exacerbation of radiation-induced volume loss by metformin was found to be predominantly present in male 7 Gy-MET16 mice (Figure 5D and F), driving the appearance of the average behavior (Figure 5C and E). This effect is largely mitigated in the 7 Gy-MET19 group, where near normal volume is achieved by P98 (both for males and females). Together, these findings indicate that the increased volume loss caused by metformin delivered immediately after radiation is more prominent in males and only partially mitigated by an increased sex-dependent growth rate. However, both sexes benefited in the MET19 group and showed improved P98 volume outcomes after radiation.

Fig. 5.

Sex modulates the effects of metformin in the irradiated brain. We tested for the impact of biological sex on the MET16 and MET19 interactions with radiation treatment by evaluating the 3-way interaction term of sex, radiation condition, and metformin treatment (denoted as SEX:7Gy:MET16 and SEX:7Gy:MET19). In (A, B), the color map shows all structures that had a significant difference in the radiation-metformin interaction between males and females (FDR of 10%). Slice positions in (A) match those in Figure 2. Many regions were relatively larger in the early (P23) irradiated metformin-treated female brain compared to the irradiated metformin-treated male brain. However, a greater growth rate was observed in metformin-treated irradiated males compared to metformin-treated irradiated females, particularly for MET16. In (C, E), representative plots averaged over males and females show the time course of structure volumes for the primary somatosensory cortex (forelimb region) and stratum granulosum of the hippocampus in unirradiated vehicle-treated mice (0 Gy-VEH), irradiated vehicle-treated mice (7 Gy-VEH), unirradiated MET16- or MET19-treated mice (0 Gy-MET16 or 0 Gy-MET19) and irradiated MET16- or MET19-treated mice (7 Gy-MET16 or 7 Gy-MET19). The plots are repeated in (D, F), with panels separated by sex to show sex-dependent differences. Points and error bars represent the mean volume and bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals. Abbreviations: 0 Gy, unirradiated; 7 Gy, irradiated with a 7-Gy dose; MET16, treated with metformin starting at P16; MET19, treated with metformin starting at P19; S1, primary somatosensory cortex (forelimb region); SG, stratum granulosum of hippocampus.

Metformin Enhances Hippocampal Neurogenesis and Oligodendrogenesis in the Normal Brain

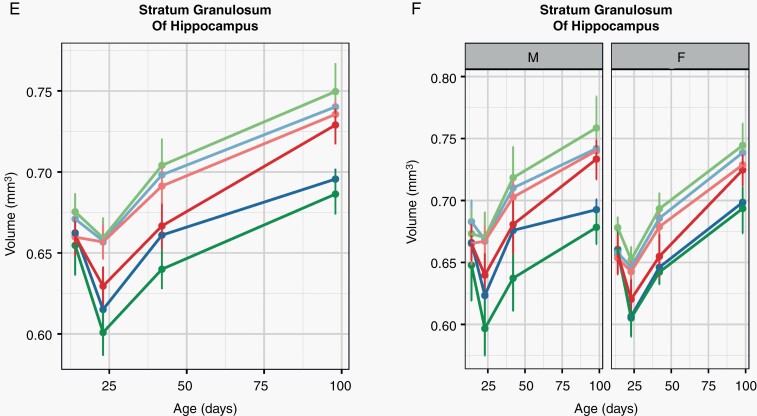

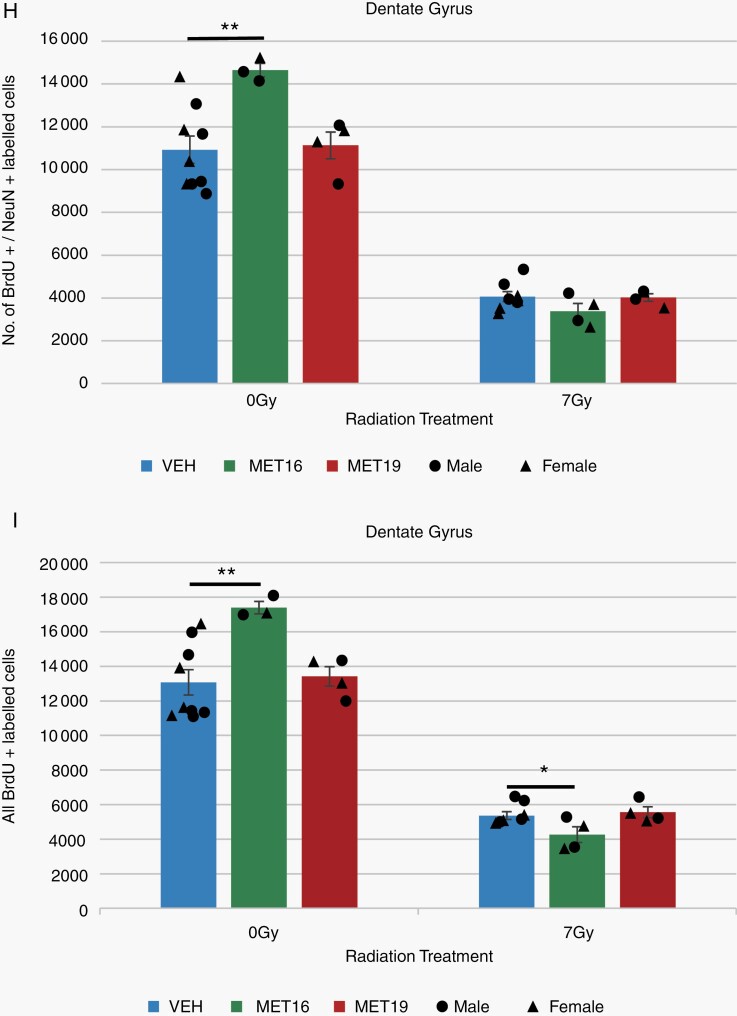

Because our structural data indicated that metformin increased the growth of some brain regions, including the neurogenic regions of the hippocampus, we investigated the impact of metformin on neurogenesis. At P28, a cohort of mice representing each experimental group received BrdU injections for 7 days before perfusion at P42. Immunostaining of dentate gyrus sections (Figure 6A–G) showed that MET16 treatment significantly increased the number of double BrdU/NeuN-positive newly born neurons (Figure 6B and H) as well as the total number of proliferative cells (BrdU-positive cells, Figure 6B and I), consistent with enhanced neurogenesis and cell proliferation. MET19 treatment did not have a significant effect on neurogenesis or cell proliferation in unirradiated mice (Figure 6C, H, and I), consistent with volumetric findings showing more extensive growth in the 0 Gy-MET16 group than the 0 Gy-MET19 group.

Fig. 6.

Metformin enhances neurogenesis and proliferation in the unirradiated brain. Representative confocal images (A–F) of BrdU, NeuN, and DAPI immunostaining in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus for unirradiated (VEH-0 Gy, n = 9; MET16-0 Gy, n = 3, MET19-0 Gy, n = 4) or irradiated (VEH-7 Gy, n = 8; MET16-7 Gy, n = 4, MET19-7 Gy, n = 4) mice at P42 (after BrdU labeling from P28-P35). Confocal images show cells with immunoreactivity for BrdU (first column), NeuN (second column), DAPI (third column), and merged (fourth column). Arrows indicate BrdU-positive, NeuN-positive cells and arrowheads indicate BrdU-positive and NeuN-negative cells (G). Scale bars represent 100 and 10 µm (A–F and G, respectively). BrdU- and BrdU/NeuN-positive cell counts within the dentate gyrus (H, I) demonstrate a significant radiation-induced loss in proliferative cells and new neurons at 42 days of age (P < .05, 2-way ANOVA; H, I). In unirradiated mice, an increase in the number of BrdU- and BrdU/NeuN-positive cells is observed with MET16 treatment compared with VEH controls. In irradiated mice, a significant decrease in double BrdU/NeuN-positive cells is observed with MET16 treatment compared to VEH controls (I). MET19 treatment, on the other hand, was not different from VEH in either irradiated or unirradiated mice for any cell counts. Colored bars represent means, whereas small black circles and triangles represent individual male or female mice, respectively. Error bars are SEM. Abbreviations: 0 Gy, unirradiated; 7 Gy, irradiated with a 7-Gy dose; MET16, treated with metformin starting at P16; MET19, treated with metformin starting at P19; VEH, vehicle-treated mice. *P < .05, **P < .01, Student t test.

Radiation significantly depleted hippocampal cells double-labeled for BrdU and NeuN (Figure 6D and H) as well as all BrdU-labeled cells (Figure 6D and I). Neither metformin treatment condition had a significant effect on the number of double BrdU/NeuN-positive cells in radiation-treated mice (Figure 6E, F, and H). A significant decrease was observed in the total BrdU-labeled cell population of the 7 Gy-MET16 group relative to the 7 Gy-VEH group (Figure 6E and I). In both BrdU-positive and BrdU/NeuN-positive cell populations, the 7 Gy-MET19 condition shows similar cell counts to 7 Gy-VEH controls (Figure 6F, H, and I). A similar pattern is observed in BrdU-positive/NeuN-negative cell counts (Supplementary Figure S3).

Similarly, we evaluated newborn/proliferating oligodendrocytes and oligodendrocyte precursor cells by quantifying cells double-labeled for BrdU and Olig2 in the corpus callosum. Mirroring the NeuN counts, an increased density of BrdU/Olig2-positive cells was observed as a result of MET16 treatment but not after MET19 treatment (0 Gy, Supplementary Figure S4). Irradiation substantially decreased both BrdU-positive and BrdU/Olig2-positive cell density and was not restored by either MET16 or MET19 treatments. Collectively, these findings suggest that the volume recovery after MET19 treatment is not solely the result of neurogenesis or oligodendrogenesis—at least not as evaluated at P42 after BrdU labeling from P28 through P35.

Discussion

There has been considerable interest in repurposing metformin for brain injury repair, due to its potential to enhance neurogenesis and improve memory.11,13 Given that a majority of radiation-treated pediatric brain cancer survivors experience impairment in at least 1 neurocognitive domain,51 benefits of metformin treatment could have enormous impact. Our findings in this study replicate previous work34,52 showing that radiation-induced alterations in brain structure proceed through 2 stages: first, a widespread early volume loss that appears in the first-week post-irradiation and second, a longer-term deficit caused by slowed growth (restricted to a few structures). Metformin treatment after radiation can increase growth through development, with benefits especially apparent in the olfactory bulbs (at P98 in MET19 mice), a region that requires the supply of NPCs throughout the lifespan.53

One unexpected finding in this study was that irradiation followed by metformin treatment resulted in significantly more volume loss than radiation alone, particularly in male mice. We found that a post-radiation delay of 3 days prior to commencement of metformin treatment (ie, MET19 group) was extremely beneficial for brain structure outcomes. Dependence of metformin treatment outcomes on timing has been observed previously; for example, in a stroke model, administration 3 days prior to middle cerebral artery occlusion exacerbated stroke damage and resulted in metabolic dysfunction whereas administration 3 weeks prior to injury was neuroprotective.26 Interestingly, recent work has also demonstrated that metformin treatment prior to CRT (from P9 to P15 before irradiation at P17), promoted a rescue of neurogenesis after CRT, though it did not prevent radiation-induced neural stem cell depletion.54 Although the details of the timing, age of treatment, and type of insult in these studies vary, it is clear that administration timing requires careful selection to ensure benefit is achieved with minimal risk of exacerbating injury; initiation of metformin administration too close to the time of injury—a common feature in at least this and the stroke study26—may be detrimental.

Another notable finding that we observed was a strong sex dependence of metformin effects in irradiated mice, despite limited sex effects in unirradiated mice (Supplementary Figures S5 and S6). This result builds upon a recent study demonstrating an increase in neuroblasts and improved cognitive outcomes in juvenile CRT-treated females, but not males.13 In that work, radiation (8 Gy) delivered at P17 resulted in functional deficits in the Y-maze task or novel place recognition task for females and males, respectively. Metformin treatment commenced 1 day after irradiation resulted in improved task performance for females but not males. Consistent with these results, our data indicate better metformin-linked outcomes for females, even though females were moderately more sensitive to radiation. It is not clear why young irradiated male mice exhibit increased sensitivity to metformin treatment. In humans, patterns of vulnerability for early-onset neuropsychiatric disorders show a male preponderance.55 Interestingly, recent work in mice has also shown that sexually dimorphic areas in mice that are relatively larger in males emerge relatively early compared to areas larger in females.56 Subtle sex differences in sensitivities/dynamics may have much broader consequences in the presence of appropriate stressors. Sex differences in stress or immune response, mitochondrial function, microglia numbers, and cell death pathways may manifest in differential responses to brain injury and confer sexual differences in windows of metformin vulnerability after radiation.57,58

One exciting finding in this study is that metformin treatment can promote a partial recovery of volume after irradiation. Although there were substantial long-term volume improvements in the olfactory bulbs and the stratum granulosum of the hippocampus, our histological findings showed that MET19 did not substantively alter neurogenesis in irradiated mice. Effects of metformin treatment on oligodendrogenesis also appeared to be quite limited over the timescale investigated, suggesting other mechanisms are likely involved in determining outcome. Indeed, metformin is pleiotropic. For instance, in an adult mouse model of ischemic stroke, chronic metformin treatment resulted in reduced infarct volume, decreased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and decreased ICAM-1 (intercellular adhesion molecule 1) expression with the result of reduced neutrophil infiltration and inflammation.59 Metformin has also been shown to promote angiogenesis in the injured brain.20,22,25 CRT is known to increase inflammation and can affect vasculature,37,60 therefore, metformin may be exerting beneficial effects in these aspects of brain response.

Since metformin has been used for decades to treat diabetes, novel applications using metformin have the potential to be readily translated into clinical practice. Processes of neurogenesis, myelination, and synaptic pruning are ongoing in children and adolescents. While this is likely to increase CRT toxicity in children compared to adults, it also creates an opportunity for interventions such as metformin that support or promote these endogenous processes for enhanced recovery. However, our study emphasizes that caution is warranted. Metformin acts on numerous biological pathways, raising broad potential for heterogeneous effects by region and differential effects in individuals. Our results show that metformin’s effects on radiation outcomes are dependent on sex and timing of administration. Although metformin can improve neuroanatomical outcomes after irradiation under the right circumstances, there is also risk of exacerbating outcomes so that careful implementation is warranted.

Supplementary Material

Funding

We gratefully acknowledge that our research was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (156250) and the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research (IA-024) through funding provided by the Government of Ontario.

Conflict of interest statement. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Authorship statement. Experimental design: K.U.S. and B.J.N. Acquisition of data: N.Y. and Y.Q.L. Data analysis and interpretation: N.Y., Y.Q.L., and B.J.N. Manuscript writing: N.Y., C.S.W., D.J.M., and B.J.N. Review and/or revision of the manuscript: C.S.W., D.J.M., and B.J.N. Study supervision: C.M.M., C.S.W., D.J.M., and B.J.N. Funding acquisition: D.J.M., C.S.W., and B.J.N.

References

- 1.Spiegler BJ, Bouffet E, Greenberg ML, Rutka JT, Mabbott DJ. Change in neurocognitive functioning after treatment with cranial radiation in childhood. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(4):706–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scantlebury N, Bouffet E, Laughlin S, et al. White matter and information processing speed following treatment with cranial-spinal radiation for pediatric brain tumor. Neuropsychology. 2016;30(4):425–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brinkman TM, Krasin MJ, Liu W, et al. Long-term neurocognitive functioning and social attainment in adult survivors of pediatric CNS tumors: results from the St Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(12):1358–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reddick WE, Taghipour DJ, Glass JO, et al. Prognostic factors that increase the risk for reduced white matter volumes and deficits in attention and learning for survivors of childhood cancers. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(6):1074–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Padovani L, André N, Constine LS, Muracciole X. Neurocognitive function after radiotherapy for paediatric brain tumours. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8(10):578–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellenberg L, Liu Q, Gioia G, et al. Neurocognitive status in long-term survivors of childhood CNS malignancies: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Neuropsychology. 2009;23(6):705–717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller FD, Kaplan DR. Mobilizing endogenous stem cells for repair and regeneration: are we there yet? Cell Stem Cell. 2012;10(6):650–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monje ML, Mizumatsu S, Fike JR, Palmer TD. Irradiation induces neural precursor-cell dysfunction. Nat Med. 2002;8(9):955–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Monje ML, Vogel H, Masek M, Ligon KL, Fisher PG, Palmer TD. Impaired human hippocampal neurogenesis after treatment for central nervous system malignancies. Ann Neurol. 2007;62(5):515–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mizumatsu S, Monje ML, Morhardt DR, Rola R, Palmer TD, Fike JR. Extreme sensitivity of adult neurogenesis to low doses of X-irradiation. Cancer Res. 2003;63(14):4021–4027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, Gallagher D, DeVito LM, et al. Metformin activates an atypical PKC-CBP pathway to promote neurogenesis and enhance spatial memory formation. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11(1):23–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruddy RM, Adams KV, Morshead CM. Age- and sex-dependent effects of metformin on neural precursor cells and cognitive recovery in a model of neonatal stroke. Sci Adv. 2019;5(9):eaax1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ayoub R, Ruddy RM, Cox E, et al. Assessment of cognitive and neural recovery in survivors of pediatric brain tumors in a pilot clinical trial using metformin. Nat Med. 2020;26(8):1285–1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monje ML, Toda H, Palmer TD. Inflammatory blockade restores adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Science. 2003;302(5651):1760–1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen Z, Palmer TD. Differential roles of TNFR1 and TNFR2 signaling in adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;30:45–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee SW, Haditsch U, Cord BJ, et al. Absence of CCL2 is sufficient to restore hippocampal neurogenesis following cranial irradiation. Brain Behav Immun. 2013;30:33–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sorrells SF, Paredes MF, Cebrian-Silla A, et al. Human hippocampal neurogenesis drops sharply in children to undetectable levels in adults. Nature. 2018;555(7696):377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eriksson PS, Perfilieva E, Björk-Eriksson T, et al. Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nat Med. 1998;4(11):1313–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jia J, Cheng J, Ni J, Zhen X. Neuropharmacological actions of metformin in stroke. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2015;13(3):389–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jin Q, Cheng J, Liu Y, et al. Improvement of functional recovery by chronic metformin treatment is associated with enhanced alternative activation of microglia/macrophages and increased angiogenesis and neurogenesis following experimental stroke. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;40:131–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dadwal P, Mahmud N, Sinai L, et al. Activating endogenous neural precursor cells using metformin leads to neural repair and functional recovery in a model of childhood brain injury. Stem Cell Reports. 2015;5(2):166–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Y, Tang G, Zhang Z, Wang Y, Yang GY. Metformin promotes focal angiogenesis and neurogenesis in mice following middle cerebral artery occlusion. Neurosci Lett. 2014;579:46–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanadgol N, Barati M, Houshmand F, et al. Metformin accelerates myelin recovery and ameliorates behavioral deficits in the animal model of multiple sclerosis via adjustment of AMPK/Nrf2/mTOR signaling and maintenance of endogenous oligodendrogenesis during brain self-repairing period. Pharmacol Rep. 2020;72(3):641–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Livingston JM, Syeda T, Christie T, Gilbert EAB, Morshead CM. Subacute metformin treatment reduces inflammation and improves functional outcome following neonatal hypoxia ischemia. Brain Behav Immun Health. 2020;7:100119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Venna VR, Li J, Hammond MD, Mancini NS, McCullough LD. Chronic metformin treatment improves post-stroke angiogenesis and recovery after experimental stroke. Eur J Neurosci. 2014;39(12):2129–2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li J, Benashski SE, Venna VR, McCullough LD. Effects of metformin in experimental stroke. Stroke. 2010;41(11):2645–2652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheki M, Shirazi A, Mahmoudzadeh A, Bazzaz JT, Hosseinimehr SJ. The radioprotective effect of metformin against cytotoxicity and genotoxicity induced by ionizing radiation in cultured human blood lymphocytes. Mutat Res. 2016;809:24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller RC, Murley JS, Grdina DJ. Metformin exhibits radiation countermeasures efficacy when used alone or in combination with sulfhydryl containing drugs. Radiat Res. 2014;181(5):464–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chevalier B, Pasquier D, Lartigau EF, et al. Metformin: (future) best friend of the radiation oncologist? Radiother Oncol. 2020;151:95–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nieman BJ, Lerch JP, Bock NA, Chen XJ, Sled JG, Henkelman RM. Mouse behavioral mutants have neuroimaging abnormalities. Hum Brain Mapp. 2007;28(6):567–575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ellegood J, Babineau BA, Henkelman RM, Lerch JP, Crawley JN. Neuroanatomical analysis of the BTBR mouse model of autism using magnetic resonance imaging and diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroimage. 2013;70:288–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Guzman AE, Gazdzinski LM, Alsop RJ, et al. Treatment age, dose and sex determine neuroanatomical outcome in irradiated juvenile mice. Radiat Res. 2015;183(5):541–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nieman BJ, de Guzman AE, Gazdzinski LM, et al. White and gray matter abnormalities after cranial radiation in children and mice. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;93(4):882–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gazdzinski LM, Cormier K, Lu FG, Lerch JP, Wong CS, Nieman BJ. Radiation-induced alterations in mouse brain development characterized by magnetic resonance imaging. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84(5):e631–e638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fowler JF. The linear-quadratic formula and progress in fractionated radiotherapy. Br J Radiol. 1989;62(740):679–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chow BM, Li YQ, Wong CS. Radiation-induced apoptosis in the adult central nervous system is p53-dependent. Cell Death Differ. 2000;7(8):712–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang J, Tong F, Cai Q, et al. Shenqi Fuzheng Injection attenuates irradiation-induced brain injury in mice via inhibition of the NF-κB signaling pathway and microglial activation. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2015;36(11):1288–1299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wadghiri YZ, Blind JA, Duan X, et al. Manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MEMRI) of mouse brain development. NMR Biomed. 2004;17(8):613–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Friedel M, van Eede MC, Pipitone J, Chakravarty MM, Lerch JP. Pydpiper: a flexible toolkit for constructing novel registration pipelines. Front Neuroinform. 2014;8:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nieman BJ, van Eede MC, Spring S, Dazai J, Henkelman RM, Lerch JP. MRI to assess neurological function. Curr Protoc Mouse Biol. 2018;8(2):e44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dorr AE, Lerch JP, Spring S, Kabani N, Henkelman RM. High resolution three-dimensional brain atlas using an average magnetic resonance image of 40 adult C57Bl/6J mice. Neuroimage. 2008;42(1):60–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ullmann JFP, Watson C, Janke AL, Kurniawan ND, Reutens DC. A segmentation protocol and MRI atlas of the C57BL/6J mouse neocortex. Neuroimage. 2013;78:196–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Steadman PE, Ellegood J, Szulc KU, et al. Genetic effects on cerebellar structure across mouse models of autism using a magnetic resonance imaging atlas. Autism Res. 2014;7(1):124–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015;67(1):1–48. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Satterthwaite FE.An approximate distribution of estimates of variance components. Biometrics Bull. 1946;2(6):110–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Royal Stat Soc Ser B (Methodol). 1995;57(1):289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cahill LS, Laliberté CL, Ellegood J, et al. Preparation of fixed mouse brains for MRI. Neuroimage. 2012;60(2):933–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Guzman AE, Wong MD, Gleave JA, Nieman BJ. Variations in post-perfusion immersion fixation and storage alter MRI measurements of mouse brain morphometry. Neuroimage. 2016;142:687–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paxinos G, Franklin K.. The Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Academic Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bull C, Cooper C, Lindahl V, et al. Exercise in adulthood after irradiation of the juvenile brain ameliorates long-term depletion of oligodendroglial cells. Radiat Res. 2017;188(4):443–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Palmer SL, Armstrong C, Onar-Thomas A, et al. Processing speed, attention, and working memory after treatment for medulloblastoma: an international, prospective, and longitudinal study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(28):3494–3500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Guzman AE, Ahmed M, Li Y-Q, Wong CS, Nieman BJ. p53 loss mitigates early volume deficits in the brains of irradiated young mice. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;103(2):511–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Urbán N, Guillemot F. Neurogenesis in the embryonic and adult brain: same regulators, different roles. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Derkach D, Kehtari T, Renaud M, Heidari M, Lakshman N, Morshead CM. Metformin pretreatment rescues olfactory memory associated with subependymal zone neurogenesis in a juvenile model of cranial irradiation. Cell Rep Med. 2021;2(4):100231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rutter M, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. Using sex differences in psychopathology to study causal mechanisms: unifying issues and research strategies. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2003;44(8):1092–1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Qiu LR, Fernandes DJ, Szulc-Lerch KU, et al. Mouse MRI shows brain areas relatively larger in males emerge before those larger in females. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sohrabji F, Park MJ, Mahnke AH. Sex differences in stroke therapies. J Neurosci Res. 2017;95(1–2):681–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schroeder A, Notaras M, Du X, Hill RA. On the developmental timing of stress: delineating sex-specific effects of stress across development on adult behavior. Brain Sciences. 2018;8(7):121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu Y, Tang G, Li Y, et al. Metformin attenuates blood-brain barrier disruption in mice following middle cerebral artery occlusion. J Neuroinflammation. 2014;11:177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wong CS, van der Kogel AJ. Mechanisms of radiation injury to the central nervous system: implications for neuroprotection. Mol Interv. 2004;4(5):273–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.