Abstract

Background

Studies addressing neuroimaging findings as primary outcomes of congenital Zika virus infection are variable regarding inclusion criteria and confirmatory laboratory testing.

Purpose

To investigate cranial US signs of prenatal Zika virus exposure and to describe frequencies of cranial US findings in infants exposed to Zika virus compared to those in control infants.

Materials and Methods

In this single-center prospective cohort study, participants were enrolled during the December 2015–July 2016 outbreak of Zika virus infection in southeast Brazil (Natural History of Zika Virus Infection in Gestation cohort). Eligibility criteria were available cranial US and laboratory findings of maternal Zika virus infection during pregnancy confirmed with RNA polymerase chain reaction testing (ie, Zika virus–exposed infants). The control group was derived from the Zika in Infants and Pregnancy cohort and consisted of infants born to asymptomatic pregnant women who tested negative for Zika virus infection during pregnancy. Two radiologists who were blinded to the maternal Zika virus infection status independently reviewed cranial US scans from both groups and categorized them as normal findings, Zika virus–like pattern, or mild findings. Associations between cranial US findings and prenatal Zika virus exposure were assessed with univariable analysis.

Results

Two hundred twenty Zika virus–exposed infants (mean age, 53.3 days ± 71.1 [standard deviation]; 113 boys) and born to 219 mothers infected with Zika virus were included in this study and compared with 170 control infants (mean age, 45.6 days ± 45.8; 102 boys). Eleven of the 220 Zika virus–exposed infants (5%), but no control infants, had a Zika virus–like pattern at cranial US. No difference in frequency of mild findings was observed between the groups (50 of 220 infants [23%] vs 44 of 170 infants [26%], respectively; P = .35). The mild finding of lenticulostriate vasculopathy, however, was nine times more frequent in Zika virus–exposed infants (12 of 220 infants, 6%) than in control infants (one of 170 infants, 1%) (P = .01).

Conclusion

Lenticulostriate vasculopathy was more common after prenatal exposure to Zika virus, even in infants with normal head size, despite otherwise overall similar frequency of mild cranial US findings in Zika virus–exposed infants and in control infants.

© RSNA, 2021

Online supplemental material is available for this article.

See also the editorial by Benson in this issue.

Summary

Lenticulostriate vasculopathy, a mild brain finding detected with cranial US, was more likely to occur in infants with prenatal exposure to the Zika virus than in control infants, regardless of the head circumference at birth.

Key Results

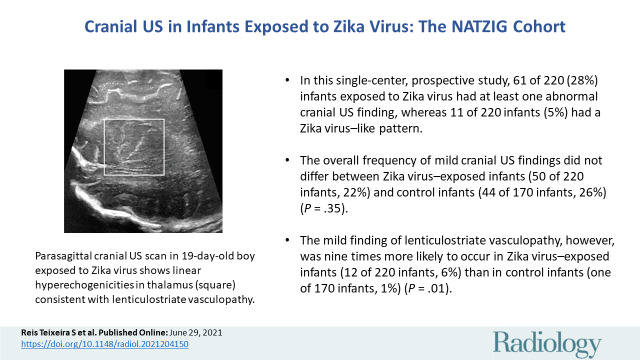

■ In this single-center prospective cohort study, 61 of 220 infants exposed to Zika virus (28%) had at least one abnormal cranial US finding, whereas 11 of 220 infants (5%) had a Zika virus–like pattern.

■ The overall frequency of mild cranial US findings did not differ between Zika virus–exposed infants (50 of 220 infants, 23%) and control infants (44 of 170 infants, 26%) (P = .35).

■ The mild finding of lenticulostriate vasculopathy, however, was nine times more likely to occur in Zika virus–exposed infants (12 of 220 infants, 6%) than in control infants (one of 170 infants, 1%) (P = .01).

Introduction

Zika virus infection during pregnancy may lead to a wide range of central nervous system changes (1–3). Most previous studies have assessed patients who are severely affected, usually associated with microcephaly, a hallmark of the infection (1,2). There is little information regarding the prevalence of central nervous system abnormalities in infants with normal head size (4). Moreover, studies addressing neuroimaging findings as primary outcomes of the offspring of mothers infected with Zika virus are variable regarding inclusion criteria. Presumable or possible Zika virus infection without a confirmatory laboratory test in the mother or infant, mixed with confirmed infections, has been used in most previous studies (1,2,5,6). Furthermore, most previous studies focused on infants with neurologic damage, microcephaly, or other evident adverse neurodevelopmental findings.

We hypothesized that nonspecific mild cranial US findings were more frequent in infants born to women infected with Zika virus than in control infants and could be a sign of prenatal Zika virus exposure, regardless of the head size. This study aimed to describe the frequencies of cranial US findings in a large group of infants born to women with laboratory-confirmed Zika virus infection (ie, infants exposed to Zika virus) compared with infants born to mothers not infected with Zika virus (ie, control infants). Also, we aimed to investigate cranial US signs of prenatal Zika virus exposure.

Materials and Methods

This single-center prospective cohort study was compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and nested in two larger prospective cohorts. The study group (ie, Zika virus–exposed infants) was derived from the Natural History of Zika Virus Infection in Gestation cohort (7), of which the main objectives were to characterize pregnancy and infants’ adverse outcomes of Zika virus infection during gestation. This cohort enrolled pregnant women infected with Zika virus and in utero Zika virus–exposed infants who lived in the regional health district of Ribeirão Preto, northeast of São Paulo state, in Brazil. Different outcome assessments from the Natural History of Zika Virus Infection in Gestation cohort were published elsewhere (7). The control group was derived from the International Prospective Observational Cohort Study of Zika in Infants and Pregnancy, or ZIP (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT02856984). The objectives of this multisite, multicountry (Brazil, Colombia, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Puerto Rico, and Peru) study was to assess the association between Zika virus infection during pregnancy and adverse maternal and/or fetal and infant outcomes. A cohort of pregnant women at less than 18 weeks of gestation was followed up throughout their pregnancy to identify clinical and laboratory evidence of acute Zika virus, whereas their newborns were followed up from birth to 1 year of age.

The procedures of this study were performed at a tertiary referral center—Clinical Hospital, Ribeirão Preto Medical School at the University of São Paulo in Brazil. The institutional ethics committee approved all study procedures (nos. 7404/2016, 9347/2016, and 5914/2017). Written informed consent was obtained from the pregnant women and the infants’ parents or guardians. This study report followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology reporting guidelines. Data generated or analyzed during the study are available from the corresponding author by request.

Participants

Participants were consecutively enrolled on meeting eligibility criteria. Inclusion criteria for the infants of the Zika virus–exposed group were available cranial US and laboratory findings of maternal Zika virus infection during pregnancy confirmed with RNA polymerase chain reaction testing. Exclusion criteria for the Zika virus–exposed group were absence of, equivocal, or negative RNA polymerase chain reaction test results for Zika virus in maternal samples during pregnancy, no follow-up at the study site, and nondiagnostic or unavailable cranial US scans. Inclusion criteria for the infants in the control group were enrollment in the Zika in Infants and Pregnancy study in the same site of the Natural History of Zika Virus Infection in Gestation cohort infants, available cranial US scans, absence of maternal exanthema or flavivirus-like signs or symptoms, absence of any positive or equivocal and/or presumptive positive immunoglobulin M test results or RNA polymerase chain reaction test results for Zika virus in maternal samples during pregnancy, absence of any central nervous system findings detected with prenatal US, absence of any neonatal neurologic clinical abnormality, and absence of congenital infections such as syphilis, cytomegalovirus, or toxoplasmosis diagnosed during gestation or at birth. Exclusion criteria for the control group were central nervous system abnormalities diagnosed with prenatal US, other congenital infectious disease, equivocal or positive serologic immunoglobulin M test results for Zika virus infection, or parental refusal of cranial US.

Clinical Data and Definitions

Neonatal gestational age at birth, in completed weeks, was determined with obstetric estimation or with pediatric newborn examination (8,9). Birth weight and head circumference z scores were classified according to the International Fetal and Newborn Growth Consortium for the 21st Century criterion (10). Infants small for gestational age were those born weighing below the 10th percentile for gestational age (11). Microcephaly at birth or in the first days of life was defined as a head circumference more than two z scores below the appropriate mean for a given age, sex, and gestational age (10). Congenital cytomegalovirus infection was diagnosed by testing the infant’s saliva within 1 week after birth with a cytomegalovirus DNA polymerase chain reaction test and confirmed with a urine sample collected within the first 3 weeks of age using the same assay. All neonates were examined by a pediatrician.

Reports from second- and third-trimester prenatal US were classified according to the following criteria: (a) normal results; (b) transitory findings that resolved until delivery, such as amniotic fluid or anatomic or growth abnormalities; (c) nonspecific findings (amniotic fluid or anatomic or growth abnormalities present at delivery but possibly not related to classic Zika virus infection); and (d) congenital Zika virus–related findings (ie, microcephaly with or without other central nervous system abnormalities, possibly related to congenital Zika virus infection). Fetal microcephaly was present when head circumference was below the third centile according to the International Fetal and Newborn Growth Consortium for the 21st Century reference standards (12).

Zika virus–exposed infants were also clinically evaluated at birth and within 3 months of age. Infants with at least two neurologic and/or neurodevelopmental abnormal findings were considered to have neurologic alert signs as follows: (a) a Hammersmith neonatal neurologic examination optimality compound score lower than 30.5 at birth, (b) a neurologic or developmental milestone abnormality at the pediatric examination at 3–6 weeks and/or at 3 months ± 1 (standard deviation) of age, and (c) an emerging and/or at-risk score in one of the five domains of the Bayley III scale of infant and toddler development screening test performed within 3 months of life.

Maternal and Infant Laboratory Testing

Zika virus infection was confirmed in mothers of Zika virus–exposed infants with detectable Zika virus RNA in blood and/or urine specimens (7,13). For the control group, as per the Zika in Infants and Pregnancy protocol, pregnant women underwent serial laboratory sampling (ie, monthly blood and biweekly urine sampling) from enrollment (<18 weeks of gestational age) to delivery for diagnosis of an acute Zika virus infection (Zika immunoglobulin M antibody capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) and viral shedding using two assays (Trioplex real-time polymerase chain reaction assay, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Emergency Operations Center; Aptima Zika Virus assay, Hologic). Participants did not have positive Zika virus RNA or serologic test results at any time. Prenatal maternal laboratory results for toxoplasmosis, human immunodeficiency virus, and Venereal Disease Research Laboratory serologic testing were abstracted from routine standard-of-care testing.

For both groups, blood, saliva, and urine samples were obtained from infants. All infants born to mothers with syphilis and possible toxoplasmosis seroconversion during pregnancy were completely evaluated for those infections. Zika virus–exposed infants were tested for anti–Zika virus immunoglobulin M using a commercial assay (ZIKV Detect IgM Capture ELISA, InBios International) in serum samples obtained at birth or at less than 3 months of age when a birth sample was not available.

Infant Cranial US Protocol

Infant cranial US was performed with one of two scanners (Logiq E9, GE Healthcare or Acuson S2000, Siemens Healthcare) by one of the senior residents of the Department of Medical Imaging under supervision of one experienced staff member. The cranial US protocol followed international guidelines (14) with an additional set of images obtained with a high-frequency linear transducer (4–15 MHz). A pediatric radiologist (S.R.T., with 8 years of experience) and a neuroradiologist (M.C.Z.Z., with 5 years of experience) with experience in pediatric imaging independently reviewed de-identified cranial US scans at a workstation in a randomized fashion. They were aware only of the infants’ sex, gestational age at birth, and age and were blinded to laboratory results and other clinical information.

Cranial US results were categorized as normal findings, Zika virus–like pattern, or mild findings. The Zika virus–like pattern was defined as the presence of at least evidence of malformations of cortical development, such as abnormal pattern of sulcation and loss of the gray matter–white matter junction, with or without subcortical calcifications or ventriculomegaly (1,2). Additional imaging findings included in the Zika virus–like pattern, such as calcifications, ventriculomegaly, ventricular adhesions or periventricular cavities, corpus callosum dysgenesis, abnormal echogenicity of the white matter, enlargement of cerebrospinal fluid spaces, and signs of brain parenchymal volume loss (1,2), could be present but were not a prerequisite to include the infant in the Zika virus–like pattern category. Mild findings were defined as the presence of at least one nonspecific cranial US finding without malformations of cortical development, such as lenticulostriate vasculopathy (LSV), subependymal cysts, calcifications, ventriculomegaly, signs of brain parenchymal volume loss, or abnormal echogenicity of the brain parenchyma. LSV and subependymal cysts are US findings previously reported to be related to pre- or perinatal brain injuries, including congenital infectious diseases (15–17). LSV was defined as the presence of at least one bifurcated or two hyperechogenic streaks or linear calcifications on either side of the basal ganglia or thalamus, as classified as moderate or severe by Koral et al (18). Subependymal cysts were defined as the presence of cystic lesions located medial to the head of the caudate nuclei, below the external angle of the frontal horns and posterior to or at the level of the foramen of Monro, within the regions of the subependymal germinal matrix (16).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed with software (RStudio, version 1.2.1578; R Foundation for Statistical Computing). We calculated the Cohen κ coefficient to estimate interrater agreement between the two independent reviewers. We investigated associations between cranial US findings and prenatal Zika virus exposure with the Fisher exact test or the Pearson χ2 test, when appropriate. We further performed univariable logistic regression analyses to assess the contribution of each mild cranial US finding alone to predict intrauterine Zika virus exposure. Then, independent variables with P < .25 were included in a multiple regression model to assess independent contributions. To ensure the results were not driven by the presence of microcephaly, we performed the same analyses in infants with normal head size. As an exploratory analysis to investigate if a Zika virus–like pattern at cranial US was dependent on gestational age of maternal infection, we performed logistic regression in the group exposed to Zika virus, adjusted for potential prenatal clinical confounders. P < .05 was considered a statistically significant difference. Significant effect size was determined as Cramer V greater than 0.25.

Results

Participant Characteristics

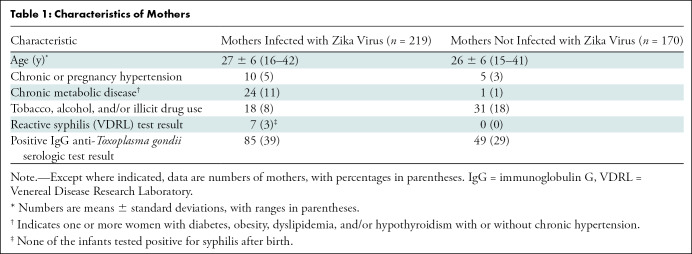

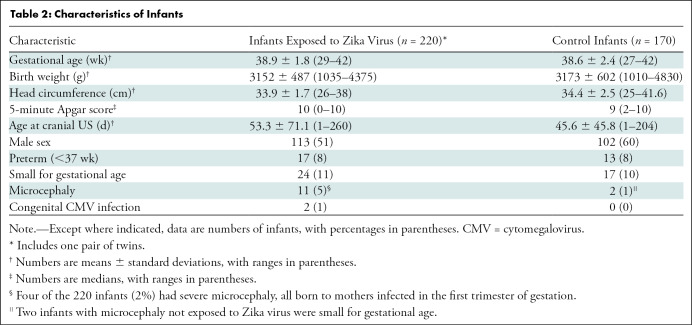

In total, 220 Zika virus–exposed infants (mean age ± standard deviation, 53.3 days ± 71.1 at cranial US; 113 boys) born to 219 mothers infected with Zika virus were included in this study and compared with 170 control infants (mean age, 45.6 days ± 45.8; 102 boys) born to 169 of 552 pregnant women not infected with Zika virus who were enrolled in the Zika in Infants and Pregnancy cohort (Fig 1). Table 1 and Table 2 summarize the main characteristics of mothers and infants of both groups, respectively. No maternal human immunodeficiency virus infection was detected in either group. No other congenital or perinatal infection was suspected in any infant.

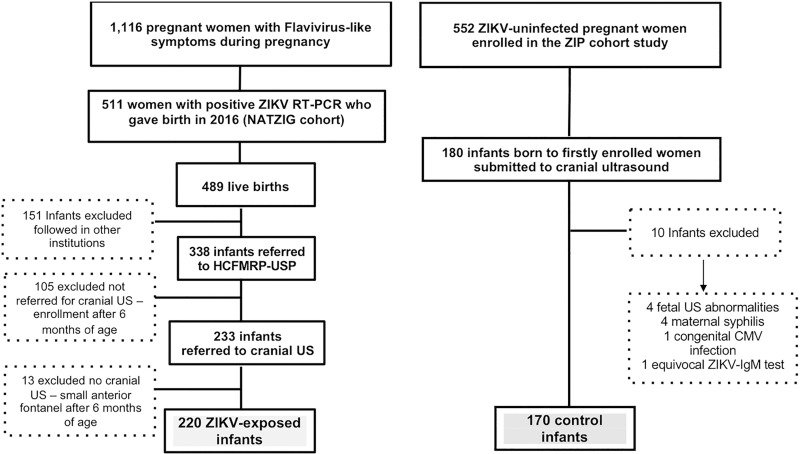

Figure 1:

Flowchart of inclusion for 220 infants exposed to Zika virus (ZIKV) and 170 control infants derived from both study cohorts. Among 511 pregnant women notified due to flavivirus-like symptoms during pregnancy with confirmed Zika virus infection, 487 gave birth to 489 live infants in 2016. Among these, 338 neonates and infants were considered eligible for this study. After excluding those without cranial US evaluation, those older than 6 months of age at time of scheduling cranial US, or those with small anterior fontanelle hampering performance of a good-quality examination, 220 infants were included in this study. Control group consisted of consecutive infants undergoing cranial US born to first 180 of 552 enrolled pregnant women not infected with Zika virus who took part in Zika in Infants and Pregnancy (ZIP) cohort in same site as those infected with Zika virus, from September 2016 onward. Eligibility criteria for these infants were absence of maternal exanthema or flavivirus-like signs or symptoms, absence of any positive or equivocal and/or presumptive positive immunoglobulin M (IgM) or real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test results for Zika virus in sequential maternal samples during pregnancy, any central nervous system finding detected with prenatal US or any neonatal neurologic clinical abnormality, and no congenital infections, such as syphilis, cytomegalovirus (CMV), or toxoplasmosis, diagnosed during gestation or at birth. HCFMRP-USP = Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto da Universidade de São Paulo, NATZIG = Natural History of Zika Virus Infection in Gestation.

Table 1:

Characteristics of Mothers

Table 2:

Characteristics of Infants

Eleven of the 220 (5%) Zika virus–exposed infants had microcephaly. Among those 11 infants, eight (73%) and three (27%) were born to mothers who were diagnosed with Zika virus infection in the first or second trimesters of gestation, respectively. Two of the three Zika virus–exposed infants who had microcephaly, and whose mothers were infected with Zika virus in the second trimester, had congenital cytomegalovirus infection; the maternal infection of the remaining infant occurred at 14 weeks of gestational age. A total of 158 Zika virus–exposed infants were tested for anti–Zika virus immunoglobulin M antibodies. Findings were negative in 150 of the 158 infants (95%) and positive in eight (5%). Positivity for anti–Zika virus immunoglobulin M antibodies was not significantly different between Zika virus–exposed infants who had microcephaly and Zika virus–exposed infants who had normal head circumference (microcephaly, one of six infants [16%]; normal head size, seven of 152 infants [5%]; P = .71).

Cranial US Results

The overall Cohen κ coefficient between the two independent reviewers who evaluated the cranial US images was 0.84 (95% CI: 0.67, 1). The Cohen κ coefficient for the mild finding of LSV was 0.76 (95% CI: 0.69, 0.83).

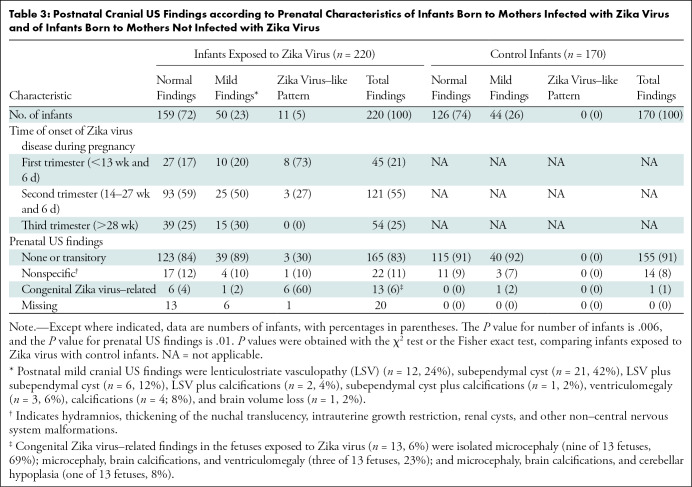

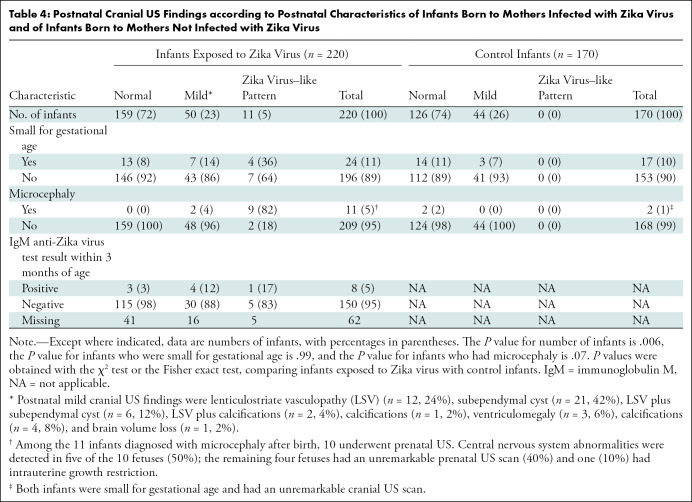

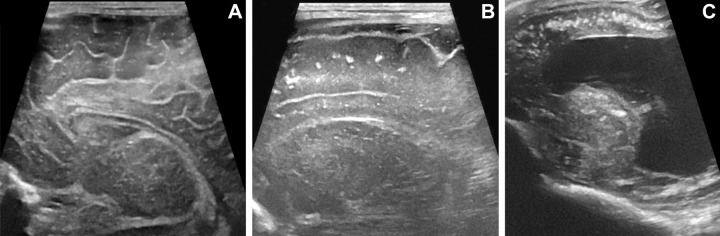

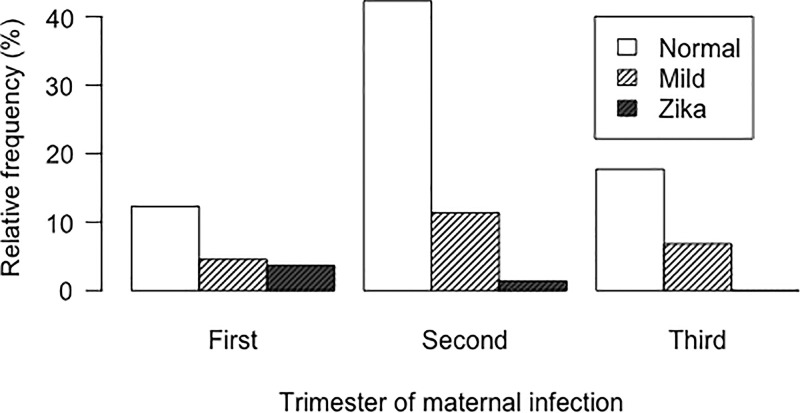

Sixty-one of the 220 Zika virus–exposed infants (28%) and 44 of the 170 control infants (26%) had abnormalities at cranial US (Tables 3, 4; Fig 2). The Zika virus–like pattern was only found in Zika virus–exposed infants (Figs 3–4). In the regression analysis, only gestational age of maternal infection was a clinical prenatal predictor of Zika virus–like pattern at postnatal cranial US, and it was associated with exposures during first or early second trimesters of gestation (Fig 5) (Tables E1–E3 [online]).

Table 3:

Postnatal Cranial US Findings according to Prenatal Characteristics of Infants Born to Mothers Infected with Zika Virus and of Infants Born to Mothers Not Infected with Zika Virus

Table 4:

Postnatal Cranial US Findings according to Postnatal Characteristics of Infants Born to Mothers Infected with Zika Virus and of Infants Born to Mothers Not Infected with Zika Virus

Figure 2:

Cranial US patterns in infants exposed to Zika virus. (A, B) Cranial US scans in infants with normal head size and mild pattern. (A) Parasagittal cranial US scan in 19-day-old boy shows linear hyperechogenicities in thalamus (square) consistent with lenticulostriate vasculopathy. (B) Coronal cranial US scan in 20-day-old girl shows bilateral subependymal cysts (arrows). (C) Coronal cranial US scan in 4-day-old boy with microcephaly and Zika virus–like pattern shows brain volume loss with bilateral ventriculomegaly (*). Bandlike subcortical calcifications (double arrows) are shown at left. Malformations of cortical development (#) are seen bilaterally. Bilateral subependymal cysts (SEC) and lenticulostriate vasculopathy (LSV) are also shown.

Figure 3:

Spectrum of malformations of cortical development in infants exposed to Zika virus. Coronal cranial US scans at level of frontal lobes in three different Zika virus–exposed infants with Zika virus–like pattern. (A) Cranial US scan in 26-day-old boy with normal head size. Asymmetry of cerebral hemispheres is shown, smaller on left side. Paucity of sulcation on left side is shown, and thickening of cortex and loss of differentiation between cortical ribbon and subcortical white matter (circle) are consistent with malformation of cortical development. Right side is normal in this infant. (B) Cranial US scan in 7-day-old girl with microcephaly. Small and smooth appearance of frontal lobes and malformation of cortical development with paucity of sulcation and diffuse cortical thickening (dotted circle) are shown. No calcification is seen. Frontal horns of lateral ventricles are dysmorphic, and there is also ventriculomegaly (not shown). (C) Cranial US scan in 107-day-old boy with bilateral malformations of cortical development and coarse subcortical calcifications (arrowheads). Note thickening of cerebral cortex (double-headed arrow).

Figure 4:

Comparison of Zika–like pattern and normal cranial US findings in infants exposed to Zika virus. (A) Normal cranial US scan in 15-day-old boy. Parasagittal scan shows expected sulcation pattern of frontal lobe. (B) Cranial US scan in 26-day-old boy with normal head size and Zika virus–like pattern. Compared with A, there is paucity of sulci in frontal lobe with smooth appearance, poor differentiation between cortex and subcortical white matter, and coarse calcifications along subcortical region. (C) Cranial US scan in 2-day-old girl with microcephaly and Zika virus–like pattern. No sulcation is seen in frontal lobes. There are diffuse coarse, coalescent, and hyperechogenic foci within subcortical white matter consistent with calcifications. Severe ventriculomegaly is also seen.

Figure 5:

Bar graph shows distribution of relative frequencies of postnatal cranial US findings according to trimester of gestation at time of maternal Zika virus infection. All infants with Zika virus–like pattern at cranial US were born to mothers infected with Zika virus in first or early second trimester of gestation.

Calcifications were present only in Zika virus–exposed infants (18 of 220 infants, 8%). Subcortical calcifications were present only in infants with a Zika virus–like pattern (nine of 11 infants, 82%). In Zika virus–exposed infants who had mild cranial US findings, calcifications were found in the periventricular regions (n = 2), basal ganglia (n = 1), and basal ganglia and periventricular regions (n = 2) and were scattered in the brain parenchyma (n = 2). Frequency of subependymal cysts, ventriculomegaly, signs of brain volume loss, and abnormal echogenicity of the brain parenchyma were not different between Zika virus–exposed infants and control infants. In infants with normal head size (n = 209), no differences in the frequencies of cranial US pattern were found between Zika virus–exposed infants (normal findings, 159 of 209 infants [76%]; mild findings, 48 of 209 infants [23%]; Zika virus–like pattern, two of 209 infants [1%]) and control infants (normal findings, 124 of 168 infants [74%]; mild findings, 44 of 168 infants [26%]; Zika virus–like pattern, 0 of 168 infants [0%]; P = .35).

Although the frequency of the mild cranial US pattern was not different between the Zika virus–exposed group and the control group, there was a higher frequency of LSV in Zika virus–exposed infants (12 of 220 infants, 6%) than in control infants (one of 170 infants, 1%) (P = .018), even when analyzing only infants with normal head size (10 of 220 Zika virus–exposed infants [5%]; one of 170 control infants [1%]; P = .03). In regression analyses, LSV was associated with intrauterine exposure to Zika virus and remained significant in the multiple regression model (Tables E1–E3 [online]). Among infants with normal head size, LSV was nine times more likely to occur in Zika virus–exposed infants.

Among the Zika virus–exposed infants, seven of 11 infants with microcephaly (64%) had severe neurologic abnormalities; all seven of these infants demonstrated a Zika virus–like pattern at cranial US. Seventeen of the 209 Zika virus–exposed infants with normal head size (8%) who were evaluated within 3 months of age had neurologic alert signs. Among these 17 infants, 15 (88%) had normal cranial US findings and two (12%) had subependymal cysts as mild cranial US findings. None of the 170 control infants had any detectable clinical abnormality within 3 months of age.

Discussion

Microcephaly has been linked to congenital Zika virus infection, and the main brain imaging findings in congenital Zika virus syndrome have been described previously (1,2). Information regarding the spectrum of brain findings in a large cohort of infants born to infected women is still scarce. In this prospectively enrolled cohort of infants with laboratory-confirmed Zika virus exposure in the prenatal period, we showed that 28% of infants exposed to Zika virus had at least one abnormal finding at cranial US and that 5% of Zika virus–exposed infants had a Zika virus–like pattern at cranial US. Eighteen percent of infants with a Zika virus–like pattern at cranial US were born without microcephaly. Lenticulostriate vasculopathy, a mild brain finding detected with cranial US, was more frequently seen in Zika virus–exposed infants than in control infants (P = .018), even in those with normal head size (P = .03). The Zika virus–like pattern at cranial US was associated with maternal Zika virus infection in the first trimester of pregnancy.

Brain imaging findings in infants without microcephaly at birth with congenital Zika virus syndrome were described in case series and reports (1,4,19,20). The limitation of these studies, except for one case report (19), is the lack of laboratory confirmation of Zika virus infection in the mother or infant. Most of these infants were possibly or probably exposed to the virus in the prenatal period. Aragao et al (4) described 52.6% (10 of 19) of cases with Zika virus–like findings but only three infants with laboratory confirmation of maternal Zika virus infection. Petribu et al (20) and Soares de Oliveira-Szejnfeld et al (1) also reported brain malformations in two infants (5%) and one infant, respectively, without microcephaly at birth but with no clear laboratory confirmation of prenatal exposure to the virus. Postnatal cranial US was used in another cohort of 57 infants (5), with 21 of these 57 infants (37%) demonstrating mild findings. This study included infants born to women with probable Zika virus infection according to clinical criteria. Confirmatory laboratory testing was available for 52 of 82 pregnant women (63%), including one asymptomatic woman with a severely affected fetus. Infants included in our cohort had laboratory confirmation of Zika virus exposure in the prenatal period. Among the 11 infants with a Zika virus–like pattern at cranial US included in our study, two (18%) were born without microcephaly. Our results confirm that absence of microcephaly at birth does not exclude the diagnosis of congenital Zika virus syndrome.

LSV is a cranial US finding related to pre- or perinatal brain injuries, including congenital infectious diseases (15,17,21). In prenatal exposure to Zika virus, LSV is one of the mild cranial US findings (5,22). We demonstrated that LSV at cranial US was more frequently seen in Zika virus–exposed infants than in control infants, even in those without microcephaly or a Zika virus–pattern. Teele et al (23) described thickened and fibrosed arterial walls of the lenticulostriate vessels of the thalami and basal ganglia, mononuclear infiltrates, and perivascular reactive astrogliosis. These findings favor inflammatory and/or reactive processes underlying LSV. A higher prevalence of LSV was also described in cohorts of infants infected with congenital cytomegalovirus (15,24). Both Zika virus and cytomegalovirus are well known for their neurotropism and may induce inflammatory reactions and astrogliosis in the brain, which may ultimately lead to neuroimaging findings, including LSV.

Neuroimaging is a fundamental component of the diagnostic evaluation of infants at risk for congenital Zika virus syndrome (25). Our results demonstrate a spectrum of neuroimaging findings in a large cohort of infants born to infected pregnant women and support recent guidelines in recommending postnatal cranial US for all infants with possible congenital Zika virus infection, regardless of the presence of microcephaly (7,26). Our data also support that the Zika virus–like pattern is mostly a consequence of Zika virus exposure in utero in the first trimester (7). Other studies showed microcephaly (27), severe brain imaging findings, Zika virus–associated birth defects (28), and risk of congenital Zika virus syndrome to be higher when the infection occurred in the first trimester of gestation (29).

Our study had limitations. We were unable to assess cranial US scans in the entire cohort in which this study is nested. Many infants were already beyond the age window for optimal cranial US during the outbreak in our region, leading to a potential selection bias. Also, we were unable to use MRI for central nervous system evaluation in all infants. Finally, the long-term clinical significance of the mild nonspecific findings was not assessed.

In conclusion, this prospective cohort study showed a spectrum of cranial US findings in infants born to women with laboratory-confirmed exposure to Zika virus. A Zika virus–like pattern at cranial US was associated with early gestational age of maternal infection. Lenticulostriate vasculopathy (LSV) was more common in the Zika virus–exposed infants than in the control infants. Except for LSV, the frequency of mild cranial US findings was not significantly different between the Zika virus–exposed infants and the control infants. Further studies are needed to evaluate the potential clinical significance of LSV and other mild cranial US findings in infants exposed to Zika virus.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Laboratory technicians, the staff members of the Study Center on Maternal, Perinatal, and Infant Infection at Ribeirão Preto Medical School, and Juan Sebastian Martin-Saavedra, MD, for assisting with data analysis. Also, the support of the Zika in Infants and Pregnancy study team was essential to enable this controlled study.

NATZIG cohort study members: Obstetrics: Geraldo Duarte, Conrado Milani Coutinho, Patricia Pereira dos Santos Melli, Marília Carolina Razera Moro, Ligia Conceição Marçal Assef, Greici Schroeder, Silvana Maria Quintana. Pediatrics: Marisa Marcia Mussi-Pinhata, Adriana Aparecida Tiraboschi Bárbaro, Juliana Dias Crivelenti Pereira Fernandes, Márcia Soares Freitas da Motta, Fabiana Rezende Amaral, Paulo Henrique Manso, Bento Vidal de Moura Negrini, Daniela Anderson, Juannicelle Tenório Albuquerque Madruga Godoi, Marina de Mattos Louren. Pathology: Fernando da Silva Ramalho. Neuropediatrics: Ana Paula Andrade Hamad, Carla Andréa Cardoso Tanuri Caldas, Marili André Coelho, Rafaela Pichini de Oliveira. Neurodevelopment: Silvia Fabiana Biason de Moura Negrini, Stephani Ferreira Rodrigues, Nádia Lombardi Maximino Siqueira, Danusa Menegat, Thamires Máximo Neves Felice. Ophthalmology: João Marcello Fortes Furtado, Milena Simões Freitas e Silva, Rafael Estevão De Angeli. Audiology: Adriana Ribeiro Tavares Anastasio, Evelin Fernanda Teixeira, Cristiane Silveira Guidi, Priscila Morales Andreazzi. Radiology: Sara Reis Teixeira, Jorge Elias Junior, Antônio Carlos dos Santos. Social Service: Adriana Veneziani Morales Morimoto, Joseane Cristina Bonfim Augusto. Research nurses: Maria Natalina Ferreira da Silva, Eunice Gonçalves da Silva, Maria Beatriz Cruz de Souza. Laboratory support: Aparecida Yulie Yamamoto, Cleonice de Souza Barbosa Sandoval, Mirian Borges de Oliveira, Alessandra Santos Zampolo.

Supported by the Fundação de Apoio ao Ensino Pesquisa e Assistência do Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina de Ribeirão Preto da Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil. Supported in part by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development as a supplement to institute grant no. 4R01HD061959-12 for the Zika in Infants and Pregnancy funding.

Disclosures of Conflicts of Interest: S.R.T. disclosed no relevant relationships. J.E. disclosed no relevant relationships. C.M.C. disclosed no relevant relationships. M.C.Z.Z. Activities related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Activities not related to the present article: received reimbursement for travel, accommodations, and meeting expenses from Mass General Brigham. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships. A.Y.Y. disclosed no relevant relationships. S.F.B.d.M.N. disclosed no relevant relationships. M.M.M.P. Activities related to the present article: disclosed no relevant relationships. Activities not related to the present article: has grants/grants pending with Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Other relationships: disclosed no relevant relationships.

Abbreviation:

- LSV

- lenticulostriate vasculopathy

Contributor Information

Sara Reis Teixeira, Email: teixeiras@chop.edu.

Collaborators: Geraldo Duarte, Conrado Milani Coutinho, Patricia Pereira dos Santos Melli, Marília Carolina Razera Moro, Ligia Conceição Marçal Assef, Greici Schroeder, Silvana Maria Quintana, Marisa Marcia Mussi-Pinhata, Adriana Aparecida Tiraboschi Bárbaro, Juliana Dias Crivelenti Pereira Fernandes, Márcia Soares Freitas da Motta, Fabiana Rezende Amaral, Paulo Henrique Manso, Bento Vidal de Moura Negrini, Daniela Anderson, Juannicelle Tenório Albuquerque Madruga Godoi, Marina de Mattos Louren, Fernando da Silva Ramalho, Ana Paula Andrade Hamad, Carla Andréa Cardoso Tanuri Caldas, Marili André Coelho, Rafaela Pichini de Oliveira, Silvia Fabiana Biason de Moura Negrini, Stephani Ferreira Rodrigues, Nádia Lombardi Maximino Siqueira, Danusa Menegat, Thamires Máximo Neves Felice, João Marcello Fortes Furtado, Milena Simões Freitas e Silva, Rafael Estevão De Angeli, Adriana Ribeiro Tavares Anastasio, Evelin Fernanda Teixeira, Cristiane Silveira Guidi, Priscila Morales Andreazzi, Sara Reis Teixeira, Jorge Elias Junior, Antônio Carlos dos Santos, Adriana Veneziani Morales Morimoto, Joseane Cristina Bonfim Augusto, Maria Natalina Ferreira da Silva, Eunice Gonçalves da Silva, Maria Beatriz Cruz de Souza, Aparecida Yulie Yamamoto, Cleonice de Souza Barbosa Sandoval, Mirian Borges de Oliveira, and Alessandra Santos Zampolo

References

- 1. Soares de Oliveira-Szejnfeld P , Levine D , Melo AS de O , et al . Congenital Brain Abnormalities and Zika Virus: What the Radiologist Can Expect to See Prenatally and Postnatally . Radiology 2016. ; 281 ( 1 ): 203 – 218 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. de Fatima Vasco Aragao M , van der Linden V , Brainer-Lima AM , et al . Clinical features and neuroimaging (CT and MRI) findings in presumed Zika virus related congenital infection and microcephaly: retrospective case series study . BMJ 2016. ; 353 i1901 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nogueira ML , Nery Júnior NRR , Estofolete CF , et al . Adverse birth outcomes associated with Zika virus exposure during pregnancy in São José do Rio Preto, Brazil . Clin Microbiol Infect 2018. ; 24 ( 6 ): 646 – 652 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Aragao MFVV , Holanda AC , Brainer-Lima AM , et al . Nonmicrocephalic infants with congenital zika syndrome suspected only after neuroimaging evaluation compared with those with microcephaly at birth and postnatally: How large is the Zika virus “iceberg”? . AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2017. ; 38 ( 7 ): 1427 – 1434 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mulkey SB , Bulas DI , Vezina G , et al . Sequential Neuroimaging of the Fetus and Newborn With In Utero Zika Virus Exposure . JAMA Pediatr 2019. ; 173 ( 1 ): 52 – 59 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pool KL , Adachi K , Karnezis S , et al . Association Between Neonatal Neuroimaging and Clinical Outcomes in Zika-Exposed Infants From Rio de Janeiro, Brazil . JAMA Netw Open 2019. ; 2 ( 7 ): e198124 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Coutinho CM , Negrini SFBM , Araujo DCA , et al . Early maternal Zika infection predicts severe neonatal neurological damage: results from the prospective Natural History of Zika Virus Infection in Gestation cohort study . BJOG 2021. ; 128 ( 2 ): 317-326https://doi.org/10.1111/1471 – 0528.16490 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics and the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine . Practice Bulletin No. 175: Ultrasound in Pregnancy . Obstet Gynecol 2016. ; 128 ( 6 ): e241 – e256 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Capurro H , Konichezky S , Fonseca D , Caldeyro-Barcia R . A simplified method for diagnosis of gestational age in the newborn infant . J Pediatr 1978. ; 93 ( 1 ): 120 – 122 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Villar J , Cheikh Ismail L , Victora CG , et al . International standards for newborn weight, length, and head circumference by gestational age and sex: the Newborn Cross-Sectional Study of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project . Lancet 2014. ; 384 ( 9946 ): 857 – 868 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gordijn SJ , Beune IM , Thilaganathan B , et al . Consensus definition of fetal growth restriction: a Delphi procedure . Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2016. ; 48 ( 3 ): 333 – 339 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Papageorghiou AT , Ohuma EO , Altman DG , et al . International standards for fetal growth based on serial ultrasound measurements: the Fetal Growth Longitudinal Study of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project . Lancet 2014. ; 384 ( 9946 ): 869 – 879 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lanciotti RS , Kosoy OL , Laven JJ , et al . Genetic and serologic properties of Zika virus associated with an epidemic, . Yap State, Micronesia, 2007. . Emerg Infect Dis 2008. ; 14 ( 8 ): 1232 – 1239 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM); American College of Radiology (ACR); Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound (SRU). AIUM practice guideline for the performance of neurosonography in neonates and infants . J Ultrasound Med 2014. ; 33 ( 6 ): 1103 – 1110 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cantey JB , Sisman J . The etiology of lenticulostriate vasculopathy and the role of congenital infections . Early Hum Dev 2015. ; 91 ( 7 ): 427 – 430 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Makhoul IR , Zmora O , Tamir A , Shahar E , Sujov P . Congenital subependymal pseudocysts: own data and meta-analysis of the literature . Isr Med Assoc J 2001. ; 3 ( 3 ): 178 – 183 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Giannattasio A , Di Costanzo P , Milite P , et al . Is lenticulostriated vasculopathy an unfavorable prognostic finding in infants with congenital cytomegalovirus infection? . J Clin Virol 2017. ; 91 ( 31 ): 35 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Koral K , Sisman J , Pritchard M , Rosenfeld CR . Lenticulostriate vasculopathy in neonates: Perspective of the radiologist . Early Hum Dev 2015. ; 91 ( 7 ): 431 – 435 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. de Freitas Ribeiro BN , Muniz BC , Gasparetto EL , Marchiori E . Congenital involvement of the central nervous system by the Zika virus in a child without microcephaly - spectrum of congenital syndrome by the Zika virus . J Neuroradiol 2018. ; 45 ( 2 ): 152 – 153https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurad.2017.11.007 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Petribu NCL , Aragao MFV , van der Linden V , et al . Follow-up brain imaging of 37 children with congenital Zika syndrome: case series study . BMJ 2017. ; 359 j4188 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Makhoul IR , Eisenstein I , Sujov P , et al . Neonatal lenticulostriate vasculopathy: further characterisation . Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2003. ; 88 ( 5 ): F410 – F414 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Soares de Souza A , Moraes Dias C , Braga FDCB , et al . Fetal Infection by Zika Virus in the Third Trimester: Report of 2 Cases . Clin Infect Dis 2016. ; 63 ( 12 ): 1622 – 1625 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Teele RL , Hernanz-Schulman M , Sotrel A . Echogenic vasculature in the basal ganglia of neonates: a sonographic sign of vasculopathy . Radiology 1988. ; 169 ( 2 ): 423 – 427 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Amir J , Schwarz M , Levy I , Haimi-Cohen Y , Pardo J . Is lenticulostriated vasculopathy a sign of central nervous system insult in infants with congenital CMV infection? . Arch Dis Child 2011. ; 96 ( 9 ): 846 – 850 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mulkey SB . Importance of Neuroimaging in the Evaluation of Zika Virus-Exposed Infants . JAMA Netw Open 2019. ; 2 ( 7 ): e198137 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Adebanjo T , Godfred-Cato S , Viens L , et al . Update: Interim Guidance for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Management of Infants with Possible Congenital Zika Virus Infection - United States, October 2017 . MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017. ; 66 ( 41 ): 1089 – 1099 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. de Oliveira WK , de França GVA , Carmo EH , Duncan BB , de Souza Kuchenbecker R , Schmidt MI . Infection-related microcephaly after the 2015 and 2016 Zika virus outbreaks in Brazil: a surveillance-based analysis . Lancet 2017. ; 390 ( 10097 ): 861 – 870 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Shapiro-Mendoza CK , Rice ME , Galang RR , et al . Pregnancy Outcomes After Maternal Zika Virus Infection During Pregnancy - U.S . Territories , January 1, 2016-April 25, 2017 . MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017. ; 66 ( 23 ): 615 – 621 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hoen B , Schaub B , Funk AL , et al . Pregnancy outcomes after ZIKV infection in French territories in the Americas . N Engl J Med 2018. ; 378 ( 11 ): 985 – 994 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]