Abstract

Mixed-halide lead perovskites (MHPs) are promising materials for photovoltaics and optoelectronics due to their highly tunable bandgaps. However, they phase-segregate under continuous illumination and/or electric field, whose mechanism is still under debate. Herein, we systematically measure the phase-segregation behavior of CH3NH3Pb(BrxI1-x)3 MHPs as a function of excitation intensity and nominal halide ratio by in situ photoluminescence micro-spectroscopy. We encapsulate the MHPs with a layer of polystyrene polymer film to isolate them from the effects of the immediate atmosphere. Under this passivated condition, the phase segregation of the MHPs is very different from those without polymer passivation reported in the literature. The initial phase segregation to I-rich and Br-rich phase is observed followed by the formation of a new mixed-halide phase within several seconds that has not been reported before. We observe that the photothermal effect is amplified at the small-size I-rich domains which significantly changes the local phase segregation in the otherwise uniform film as early as milliseconds after illumination.

Graphical Abstract

Hybrid organic-inorganic mixed tri-halide perovskites (MHPs) are materials with a chemical formula of ABC3 where A is a filling cation (or mixed cations), B is the central cation (e.g. Pb), and C is the structural anion C = XxYyZz. where X, Y, Z are either Cl−, Br−, and I−, and the stoichiometry number x+y+z = 1. The perovskite structure is maintained by the average sizes of A, B, and C that follow the Goldschmidt tolerance factor.1 Their advantages over pure halide perovskites are tunable bandgap2 with simple doping procedures2–5 and still maintain excellent carrier mobility,6–9 and high solar-cell efficiency10 or photoluminescence (PL) efficiency4,11 Thus, it is promising in applications such as efficient and color-tunable LEDs,12 tandem solar cells,10 and hetero-structured microelectronic devices.13

Phase segregation has been a major observation in MHPs, which can either hurt the device’s performance14 or enhance efficiency.15,16 Unusual blue-shift of the emission pick was also observed17 and was confirmed by Hoke and coauthors to be the phase segregation due to the halide migration.18–26 The Hoke effect (or light-induced phase segregation) is reversible.27 The bandgap of the materials ranked wide to narrow from Cl-rich, Br-rich, to I-rich domains. As such, the carriers can be intrinsically split among the domains which either extend the lifetime of the carriers or hindered them from being collected depending on the locations of the domains relative to the electrodes.14–16 The phase segregation has been suspected to be initialized by either single-exciton28 or the accumulation of one kind of carrier on the surface of a grain or a nanocrystal. This internal electric field breaks Pb-halide bonds and moves halides around,29,30 which often generates neutral X2 species.29,31,32 When the neutral X2 (e.g. I2) is lost into the environment or reacts with oxygen, irreversible degradation is observed,29,31,32 which should be prevented by passivation.30 Under the dark, the halides migrate back in the order of several minutes to hours at room temperature.19,26,33–35

While we have the big picture of the phase segregation, the detailed mechanism is far from being settled. This open question requires a lot of more experimental data and theoretical simulations to answer. Using UV-Vis extinction and PL spectra to study MHPs’ phase separation has been well established in the literature,17,19,20,35 The vertical ion migration on the film and the lateral ion migration in nanowires have been reported by measuring PL with a confocal microscope.13,33,36 In this report, we track the phase segregation of methylammonium lead halide MHP films (CH3NH3Pb(BrxI1-x)3) over space and time using a home-built PL emission micro-spectroscope.37 Briefly, the films are illuminated under a wide-field fluorescence microscope (supporting information, SI Figure S1). A slit and a transmission grating are inserted before the EMCCD camera. A narrow slice of the spatially-resolved 0th order image of the illuminated film (through the grating) is selected by the slit and its associated 1st order diffraction image is collected by the same camera. The first order image provides the spatially-resolved spectra of the film whose emission wavelengths are calibrated using the standard emission peaks from a few noble gas lamps.

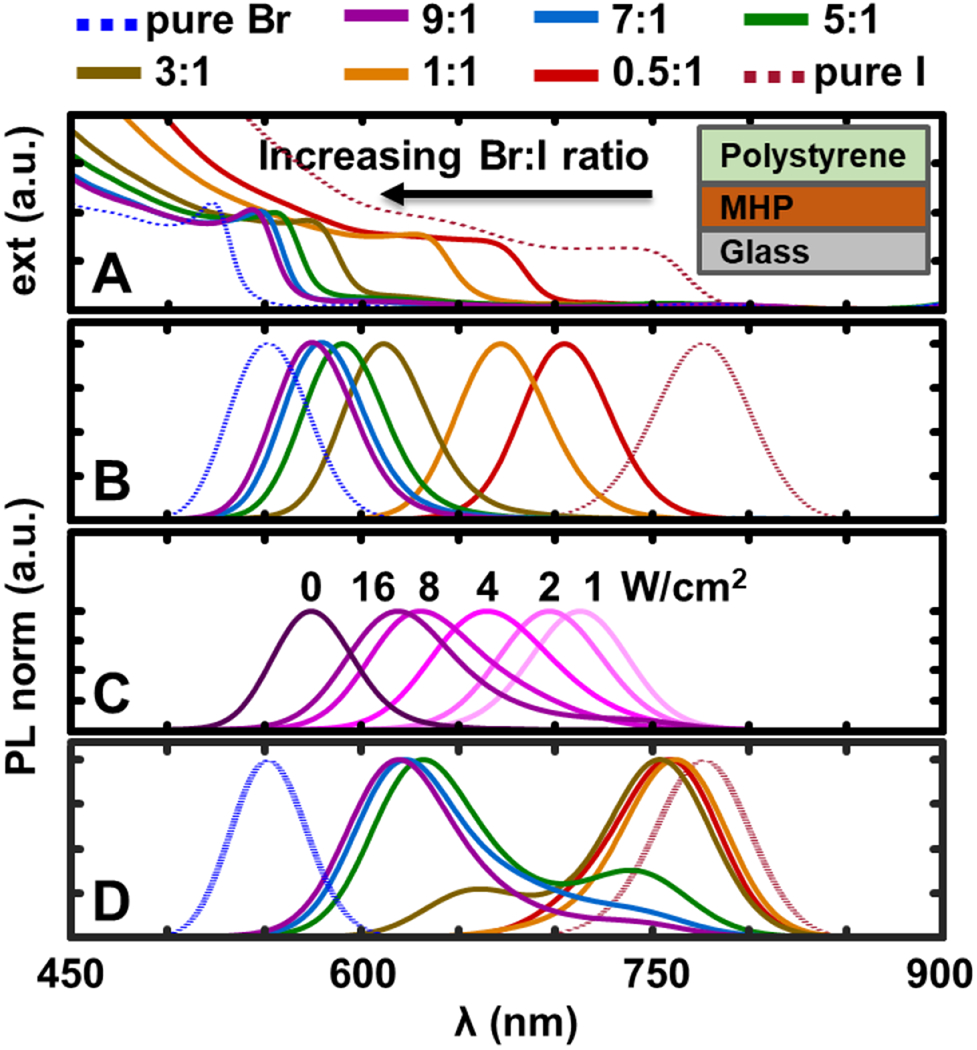

To begin with, CH3NH3Pb(BrxI1-x)3 thin films with a range of Br:I ratio from 0.5:1 to 9:1 are prepared by the solvent-washing method,38 which is then passivated by a ~1 μm thick layer of polystyrene film (MW = 280 kDa). The experimental details are described in the SI. The initial extinction edge and PL peak of the as-prepared MHP thin films blue-shift as a function of the increasing Br:I ratio (Figure 1A, 1B), which is consistent with the literature.2,19 The spectra of both pure-Br and pure-I perovskites are also included in Figure 1 as references. The film is then placed under continuous illumination for 200 seconds (473 nm CW laser). The initial PL spectra of the pure-halides stay and those of the mixed-halides red-shift over time and the degree of the shift is dependent on the illumination power density (Figure 1C). The lower the illumination intensity, the more red-shift. At a constant power density of 16 W/cm2, the extent of the red-shift appears to be strongly dependent on the initial Br:I ratio (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

(A) Extinction and (B) PL spectra of as-prepared MHP films with different Br:I ratios measured with 473 nm laser at 16 W/cm2 excitation intensity and 0.1 s exposure time. Inset showing a scheme of the samples. (C) The PL of the MHP (Br:I = 9:1) after 200 seconds illumination with varying excitation intensity (labeled, ‘0’ is the initial PL). (D) The PL of MHPs with varying Br:I ratios after 200 seconds illumination at constant power density (473 nm, 16 W/cm2).

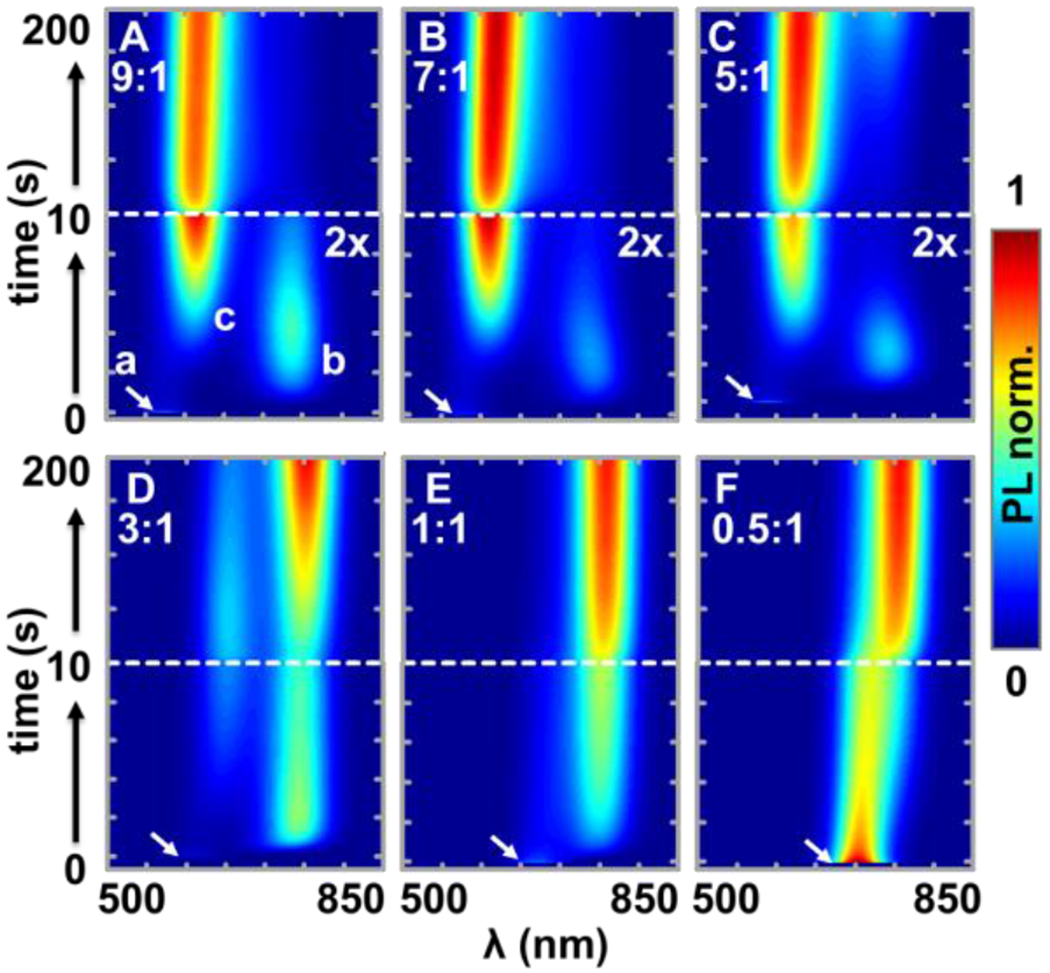

To gain insights into these observations, we obtain the time-dependent PL spectra of each MHP film. Figure 2 shows one set of data under 16 W/cm2 illumination. At time zero (t = 0), the initial MHP PL peak (a) appears instantly upon illumination (the same peaks are shown in Figure 1B). A PL peak (b) around 750 nm quickly shows up within 3 seconds. The degree and rate of the shift of peak (b) are consistent with the typical segregation of an I-rich phase described in the literature.19,31 Surprisingly, a new peak (c) between peak (a) and (b) emerges at t ~ 6 s. Overtime, this peak keeps on growing and slowly red-shifting. At the same time, peak (b) gradually disappears. Interestingly, for MHPs with lower Br:I ratio (<5:1), the peak (b) re-appeared as the formation of the peak (c) levels-off.

Figure 2.

(A-F) Time-dependent PL spectra of MHPs with various Br:I ratio under 16 W/cm2 illumination. The bottom half of each figure is the zoom-in of the first 10 s data. The arrows indicate the initial PL peak (a) at t = 0 s, the new peaks are labeled as (b) and (c) in (A). The intensity represented by the color bar is normalized to the maximum intensity of the series with the lower half of (A-C) boosted two times for better contrast.

Figure 3 shows the full sets of data in addition to the data shown in Figure 2. While the three-peak shift is similar among all samples with different Br:I ratios at high power densities (4-16 W/cm2), different dynamics is observed at lower laser power densities. Briefly, the three-peak dynamics is not apparent for samples with larger Br:I ratios at lower laser power (left-bottom corner of Figure 3A, 3B).

Figure 3.

The evolution of the PL spectra of MHP films with various Br:I ratio (column) under various excitation intensity (row) over time (color bars) during the first (A) 10 seconds and (B) 200 seconds illumination. The wavelength axis is from 450-900 nm for each spectrum. The height axis of the spectra is normalized to the maximum intensity of the spectra series.

We fit peak (b) and peak (c) in Figure 2 and Figure 3 (see SI Figure S3 for fitting examples) and assign the peaks to species with molar fraction of iodine XI according to the calibration curve of peak (a) over the initial composition (Figure 4 inset). The linear relationship between the XI and the peak center suggests a uniform mixing of the as-prepared film after thermal annealing. Then we plot XI for the peaks of all MHP films as a function of illumination intensity in Figure 4. The MHP with Br:I = 0.5:1 that has a less significant peak shift is not included in the figure. The initial composition of the film is represented by peak (a) shown in Figure 4 at Iexc = 0. The arrows point to the transition from the peak (a) to peak (b) and (c). With increasing excitation intensity, peak (b) and (c) split further on this diagram.

Figure 4.

The iodine molar fraction XI of peaks (a-c) in Figure 2 at various excitation intensities Iexc The XI is calculated based on the calibration line shown in the inset. The arrows indicate the peak shifting direction from the initial composition to the new components. Circle: represents the composition of peak (a); diamond: peak (b); square: peak (c).

These results (Figure 1–4) clearly indicate phase segregation. The initial appearance of peak (b) at t < 10 s represents the I-rich phase, associated with the typical phase-segregation observed on MHPs.2,19,21,28,33,39 Majority of the photo-generated carriers are funneled to the I-rich phase that has the lowest conduction band-edge.31,40,41 Thus, the Br-rich phase left behind is under a dark state (i.e. no emission), which if emitted would have shown a peak blue-shifted from the initial peak (a). In the literature, the I-rich phase disappears along with an onset of the Br-rich phase due to the photodegradation of the I-rich phase in the air or in vaccum.29,31,42 Surprisingly, we don’t observe the Br-rich phase, rather a new I-rich phase, peak (c), emerges that is reversible under dark or under lower excitation intensity (SI Figure S4–S5).

The formation of the new I-rich phase (peak c) under light is because of the polymer passivation on our samples, which blocks the evaporation of I2. This passivation shifts the equilibrium to a new I-rich phase under light, which is suspected to be driven by the photothermal heating.26 The Helmholtz free energy of the film is a function of internal energy, temperature, and entropy, F = U − TS.43,44 Increasing temperature enhances the effect of entropy that drives the remixing of the I-rich and Br-rich phases.26,43 According to the mass balance, the dark Br-rich should shift back to merge the new I-rich phase. The actual temperature of the film is still challenging for us to directly measure. However, we can estimate the temperature indirectly using the glass transition temperature of the polystyrene thin film, which is Tg = 370 K.40 We titrate the laser power density at room temperature TR = 297 K and find that the polystyrene film on top of the perovskite layer changes morphology above 20±5 W/cm2 (SI Figure S6). Assuming a linear correlation between ΔT and Iexc,45 the temperature of the perovskite film under illumination is estimated to be ΔT = IexcΔTg/20, where ΔTg = Tg − TR. Thus, the equilibrium temperature of the film under 16 W/cm2 is estimated to be 330 K, around the peak of the spinodal temperature of the phase diagram of MHPs calculated in the literature.44 However, since the energy is mostly funneled to the I-rich domains, their temperature can be significantly higher than this value. Thus, they may remix under even lower laser intensities due to this local heating effect. With this proposed mechanism, we hypothesize that there will be formation and dissolution of I-rich domains over time under illumination. Thus the spatial behavior of the film is explored using the same PL micro-spectroscope (SI).

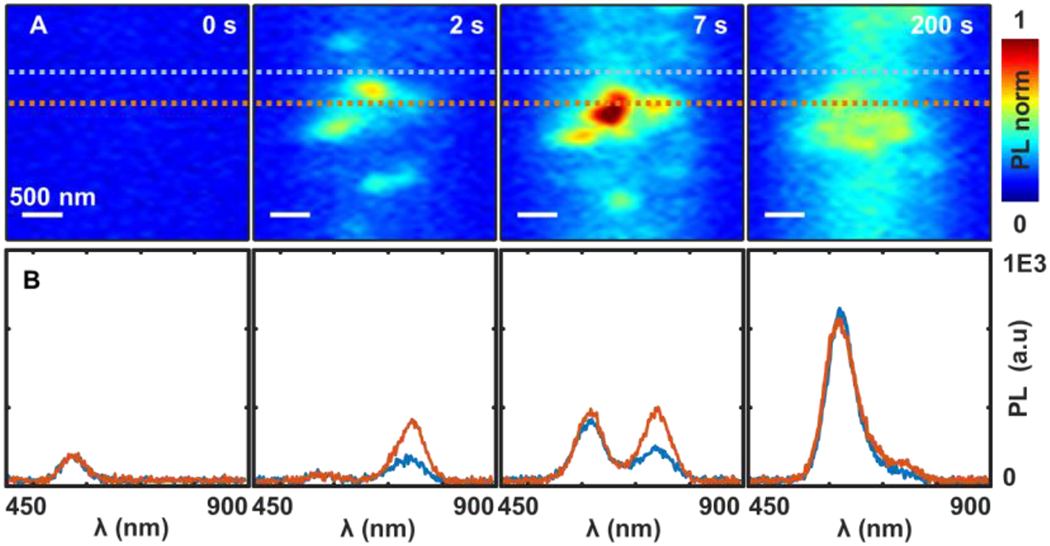

The MHP film with Br:I = 9:1 is used in Figure 5 as an example to discuss the spatial behavior. The associated video and the complete data are shown in the SI (SI video and Figure S7, S8). The 0th order diffraction image of the film (through the grating) shows the spatially-resolved grains in a thin slice of the film (~2.7 μm wide and 40 μm long). The resolution is diffraction limited ~300 nm. At the same time, the spectra of the grains can be observed in the 1st order diffraction image. At the initial stage (the first few seconds), all the grains appear to have very similar PL peak (a) suggesting relatively uniform initial composition throughout the film. In a few seconds, randomly distributed I-rich domains show up over space with emission peak shifted to peak (b). Overtime, the PL spectra of the grains coalesce back into the same PL spectra (Figure 5, 200 s), suggesting re-homogenization of the phase-segregated materials.26 This behavior is consistent with the proposed photo-thermal mechanism.

Figure 5.

Time-dependent PL micro-spectroscopy of the MHP film with Br:I = 9:1 under the illumination power density 16 W/cm2 with the 473 nm laser. (A) The 0th order PL image of a vertical slice of the MHP film. (B) The corresponding PL spectra of the locations in (A) indicated by the dashed lines, respectively. The hot-spots have I-rich emission spectra. The full video is shown in the SI movie S1.

The degree of the local heating is anti-correlated to the size of the I-rich domains. For the MHPs with a large Br:I ratio (> 5:1), the I-rich phase quickly dissolves under light (Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 5). For these films, there is less amount of iodine that nucleates into small domains, which gain a lot of energy from their Br-rich surroundings through energy transfer. Once dissolved, the local temperature drops and another round of phase segregation can happen at this location again (SI movie S1). For the MHPs with small Br:I ratio (< 3:1), the I-rich domains can grow big and do not over heat which could explain why they never completely dissolve even under strong light intensity (Figure 2).

Our results on the phase segregation under passivation and relative strong laser excitation are relevant to many applications of MHPs in photovoltaic and optoelectronic devices. A few methods have been developed to prevent phase segregation from affecting the device efficiency. Enhancing crystal thermodynamic stability of MHPs using FA as the A-site cation and carefully adjust Cs doping level obtained mixed halide perovskite that is more stable than those use MA and Cs,46,47 which either raise the kinetic barrier for ion migration or thermodynamically lower the spinodal decomposition temperature.28,44,48 Film thickness, precursor composition and ratio, synthetic process and steps, have effects on the phase stability.33,39,47,49 Under passivation, we have demonstrated that the phase segregation of the MHP films can be different from bare films. Under illumination, segregated domains with different compositions form and homogenize dynamically, which we hypothesize to associate with the local heating effect that should be investigated in the future.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Nanoscale and Quantum Phenomena Institute (NQPI) and National Institutes of Health award number R15HG009972 for support in microscope building and maintenance. We also thank Prof. Hugh Richardson and Kristina Shrestha for beneficial discussion. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Health.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publication Website.

Supporting Information. Experimental Methods, Additional data, and Movie S1 mentioned in the main text.

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- (1).Kieslich G; Sun S; Cheetham AK Solid-State Principles Applied to Organic–Inorganic Perovskites: New Tricks for an Old Dog. Chem. Sci 2014, 5, 4712–4715. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Kulkarni SA; Baikie T; Boix PP; Yantara N; Mathews N; Mhaisalkar S Band-Gap Tuning of Lead Halide Perovskites Using a Sequential Deposition Process. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 9221–9225. [Google Scholar]

- (3).Zhang T; Yang M; Benson EE; Li Z; van de Lagemaat J; Luther JM; Yan Y; Zhu K; Zhao Y A Facile Solvothermal Growth of Single Crystal Mixed Halide Perovskite CH3NH3Pb(Br1–xClx)3. Chem. Commun 2015, 51, 7820–7823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Sutter-Fella CM; Li Y; Amani M; Ager JW; Toma FM; Yablonovitch E; Sharp ID; Javey A High Photoluminescence Quantum Yield in Band Gap Tunable Bromide Containing Mixed Halide Perovskites. Nano Lett. 2016,16, 800–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Zhang Y; Lu D; Gao M; Lai M; Lin J; Lei T; Lin Z; Quan LN; Yang P Quantitative Imaging of Anion Exchange Kinetics in Halide Perovskites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2019, 116, 12648 LP – 12653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Herz LM Charge-Carrier Mobilities in Metal Halide Perovskites: Fundamental Mechanisms and Limits. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 2, 1539–1548. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Colella S; Mosconi E; Fedeli P; Listorti A; Gazza F; Orlandi F; Ferro P; Besagni T; Rizzo A; Calestani G; et al. MAPbI3-XClx Mixed Halide Perovskite for Hybrid Solar Cells: The Role of Chloride as Dopant on the Transport and Structural Properties. Chem. Mater 2013, 25, 4613–4618. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Stranks SD; Eperon GE; Grancini G; Menelaou C; Alcocer MJP; Leijtens T; Herz LM; Petrozza A; Snaith HJ Electron-Hole Diffusion Lengths Exceeding 1 Micrometer in an Organometal Trihalide Perovskite Absorber. Science 2013, 342, 341–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Rehman W; Milot RL; Eperon GE; Wehrenfennig C; Boland JL; Snaith HJ; Johnston MB; Herz LM Charge-Carrier Dynamics and Mobilities in Formamidinium Lead Mixed-Halide Perovskites. Adv. Mater 2015, 27, 7938–7944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).McMeekin DP; Sadoughi G; Rehman W; Eperon GE; Saliba M; Hörantner MT; Haghighirad A; Sakai N; Korte L; Rech B; et al. A Mixed-Cation Lead Mixed-Halide Perovskite Absorber for Tandem Solar Cells. Science 2016, 351, 151–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Deschler F; Price M; Pathak S; Klintberg LE; Jarausch D-D; Higler R; Hüttner S; Leijtens T; Stranks SD; Snaith HJ; et al. High Photoluminescence Efficiency and Optically Pumped Lasing in Solution-Processed Mixed Halide Perovskite Semiconductors. J. Phys. Chem. Lett 2014, 5, 1421–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Tan Z-K; Moghaddam RS; Lai ML; Docampo P; Higler R; Deschler F; Price M; Sadhanala A; Pazos LM; Credgington D; et al. Bright Light-Emitting Diodes Based on Organometal Halide Perovskite. Nat. Nanotechnol 2014, 9, 687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Wang Y; Chen Z; Deschler F; Sun X; Lu T-M; Wertz EA; Hu J-M; Shi J Epitaxial Halide Perovskite Lateral Double Heterostructure. ACS Nano 2017,11, 3355–3364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Samu GF; Janáky C; Kamat PV A Victim of Halide Ion Segregation. How Light Soaking Affects Solar Cell Performance of Mixed Halide Lead Perovskites. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 2, 1860–1861. [Google Scholar]

- (15).Gratia P; Grancini G; Audinot J-N; Jeanbourquin X; Mosconi E; Zimmermann I; Dowsett D; Lee Y; Grätzel M; De Angelis F; et al. Intrinsic Halide Segregation at Nanometer Scale Determines the High Efficiency of Mixed Cation/Mixed Halide Perovskite Solar Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016,138, 15821–15824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Feldmann S; Macpherson S; Senanayak SP; Abdi-Jalebi M; Rivett JPH; Nan G; Tainter GD; Doherty TAS; Frohna K; Ringe E; et al. Photodoping through Local Charge Carrier Accumulation in Alloyed Hybrid Perovskites for Highly Efficient Luminescence. Nat. Photonics 2019. [Google Scholar]

- (17).Wu K; Bera A; Ma C; Du Y; Yang Y; Li L; Wu T Temperature-Dependent Excitonic Photoluminescence of Hybrid Organometal Halide Perovskite Films. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2014, 16, 22476–22481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Pan D; Fu Y; Chen J; Czech KJ; Wright JC; Jin S Visualization and Studies of Ion-Diffusion Kinetics in Cesium Lead Bromide Perovskite Nanowires. Nano Lett. 2018,18, 1807–1813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Hoke ET; Slotcavage DJ; Dohner ER; Bowring AR; Karunadasa HI; McGehee MD Reversible Photo-Induced Trap Formation in Mixed-Halide Hybrid Perovskites for Photovoltaics. Chem. Sci 2015, 6, 613–617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Rosales BA; Men L; Cady SD; Hanrahan MP; Rossini AJ; Vela J Persistent Dopants and Phase Segregation in Organolead Mixed-Halide Perovskites. Chem. Mater 2016, 28, 6848–6859. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Mao W; Hall CR; Chesman ASR; Forsyth C; Cheng Y-B; Duffy NW; Smith TA; Bach U Visualizing Phase Segregation in Mixed-Halide Perovskite Single Crystals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. (English) 2019, 58, 2893–2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Hentz O; Zhao Z; Gradečak S Impacts of Ion Segregation on Local Optical Properties in Mixed Halide Perovskite Films. Nano Lett. 2016,16, 1485–1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Lai M; Obliger A; Lu D; Kley CS; Bischak CG; Kong Q; Lei T; Dou L; Ginsberg NS; Limmer DT; et al. Intrinsic Anion Diffusivity in Lead Halide Perovskites Is Facilitated by a Soft Lattice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2018,115, 11929 LP – 11934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Koscher BA; Bronstein ND; Olshansky JH; Bekenstein Y; Alivisatos AP Surface- vs Diffusion-Limited Mechanisms of Anion Exchange in CsPbBr3 Nanocrystal Cubes Revealed through Kinetic Studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016,138, 12065–12068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Scheidt RA; Kamat PV Temperature-Driven Anion Migration in Gradient Halide Perovskites. J. Chem. Phys 2019,151, 134703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Elmelund T; Seger B; Kuno M; Kamat PV How Interplay between Photo and Thermal Activation Dictates Halide Ion Segregation in Mixed Halide Perovskites. ACS Energy Lett. 2019, 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Byun HR; Park DY; Oh HM; Namkoong G; Jeong MS Light Soaking Phenomena in Organic–Inorganic Mixed Halide Perovskite Single Crystals. ACS Photonics 2017, 4, 2813–2820. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Bischak CG; Hetherington CL; Wu H; Aloni S; Ogletree DF; Limmer DT; Ginsberg NS Origin of Reversible Photoinduced Phase Separation in Hybrid Perovskites. Nano Lett. 2017, 17, 1028–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Wang X; Ling Y; Lian X; Xin Y; Dhungana KB; Perez-Orive F; Knox J; Chen Z; Zhou Y; Beery D; et al. Suppressed Phase Separation of Mixed-Halide Perovskites Confined in Endotaxial Matrices. Nat. Commun 2019,10, 695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Knight AJ; Wright AD; Patel JB; McMeekin DP; Snaith HJ; Johnston MB; Herz LM Electronic Traps and Phase Segregation in Lead Mixed-Halide Perovskite. ACS Energy Lett. 2019, 4, 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Ruan S; Surmiak M-A; Ruan Y; McMeekin DP; Ebendorff-Heidepriem H; Cheng Y-B; Lu J; McNeill CR Light Induced Degradation in Mixed-Halide Perovskites. J. Mater. Chem. C 2019, 7, 9326–9334. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Kim GY; Senocrate A; Yang T-Y; Gregori G; Grätzel M; Maier J Large Tunable Photoeffect on Ion Conduction in Halide Perovskites and Implications for Photodecomposition. Nat. Mater 2018, 77, 445–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Barker AJ; Sadhanala A; Deschler F; Gandini M; Senanayak SP; Pearce PM; Mosconi E; Pearson AJ; Wu Y; Srimath Kandada AR; et al. Defect-Assisted Photoinduced Halide Segregation in Mixed-Halide Perovskite Thin Films. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 2, 1416–1424. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Draguta S; Sharia O; Yoon SJ; Brennan MC; Morozov YV; Manser JS; Kamat PV; Schneider WF; Kuno M Rationalizing the Light-Induced Phase Separation of Mixed Halide Organic-Inorganic Perovskites. Nat. Commun 2017, 8, 200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Yoon SJ; Draguta S; Manser JS; Sharia O; Schneider WF; Kuno M; Kamat PV Tracking Iodide and Bromide Ion Segregation in Mixed Halide Lead Perovskites during Photoirradiation. ACS Energy Lett. 2016, 1, 290–296. [Google Scholar]

- (36).Tang X; van den Berg M; Gu E; Horneber A; Matt GJ; Osvet A; Meixner AJ; Zhang D; Brabec CJ Local Observation of Phase Segregation in Mixed-Halide Perovskite. Nano Lett. 2018,18, 2172–2178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Vicente JR; Rafiei Miandashti A; Sy Piecco KWE; Pyle JR; Kordesch ME; Chen J Single-Particle Organolead Halide Perovskite Photoluminescence as a Probe for Surface Reaction Kinetics. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 77, 18034–18043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Troughton J; Hooper K; Watson TM Humidity Resistant Fabrication of CH3NH3PbI3 Perovskite Solar Cells and Modules. Nano Energy 2017, 39, 60–68. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Yoon SJ; Kuno M; Kamat PV Shift Happens. How Halide Ion Defects Influence Photoinduced Segregation in Mixed Halide Perovskites. ACS Energy Lett. 2017, 2, 1507–1514. [Google Scholar]

- (40).Brennan MC; Draguta S; Kamat PV; Kuno M Light-Induced Anion Phase Segregation in Mixed Halide Perovskites. ACS Energy Lett. 2018, 3, 204–213. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Butler KT; Frost JM; Walsh A Band Alignment of the Hybrid Halide Perovskites CH3NH3PbCl3, CH3NH3PbBr3 and CH3NH3PbI3. Mater. Horizons 2015, 2, 228–231. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Fan W; Shi Y; Shi T; Chu S; Chen W; Ighodalo KO; Zhao J; Li X; Xiao Z Suppression and Reversion of Light-Induced Phase Separation in Mixed-Halide Perovskites by Oxygen Passivation. ACS Energy Lett. 2019, 4, 2052–2058. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Yin W-J; Yan Y; Wei S-H Anomalous Alloy Properties in Mixed Halide Perovskites. J. Phys. Chem. Lett 2014, 5, 3625–3631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Brivio F; Caetano C; Walsh A Thermodynamic Origin of Photoinstability in the CH3NH3Pb(I1-XBrx)3 Hybrid Halide Perovskite Alloy. J. Phys. Chem. Lett 2016, 7, 1083–1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Baral S; Green AJ; Richardson HH Effect of Ions and Ionic Strength on Surface Plasmon Absorption of Single Gold Nanowires. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 6080–6089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Slotcavage DJ; Karunadasa HI; McGehee MD Light-Induced Phase Segregation in Halide-Perovskite Absorbers. ACS Energy Lett. 2016, 1, 1199–1205. [Google Scholar]

- (47).Rehman W; McMeekin DP; Patel JB; Milot RL; Johnston MB; Snaith HJ; Herz LM Photovoltaic Mixed-Cation Lead Mixed-Halide Perovskites: Links between Crystallinity, Photo-Stability and Electronic Properties. Energy Environ. Sci 2017,10, 361–369. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Mosconi E; Amat A; Nazeeruddin MK; Grätzel M; De Angelis F First-Principles Modeling of Mixed Halide Organometal Perovskites for Photovoltaic Applications. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 13902–13913. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Yoon SJ; Stamplecoskie KG; Kamat PV How Lead Halide Complex Chemistry Dictates the Composition of Mixed Halide Perovskites. J. Phys. Chem. Lett 2016, 7, 1368–1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.