Abstract

Macroautophagy (hereafter autophagy) degrades and recycles intracellular components to sustain metabolism and survival during starvation. Host autophagy promotes tumor growth by providing essential tumor nutrients. Autophagy also regulates immune cell homeostasis and function and suppresses inflammation. Although host autophagy does not promote a T-cell anti-tumor immune response in tumors with low tumor mutational burden (TMB), whether this was the case in tumors with high TMB was not known. Here we show that autophagy, especially in the liver, promotes tumor immune tolerance by enabling regulatory T-cell function and limiting stimulator of interferon genes, T-cell response and interferon-γ, which enables growth of high-TMB tumors. We have designated this as hepatic autophagy immune tolerance. Autophagy thereby promotes tumor growth through both metabolic and immune mechanisms depending on mutational load and autophagy inhibition is an effective means to promote an antitumor T-cell response in high-TMB tumors.

Autophagy is a catabolic process that captures, degrades and recycles intracellular components including organelles such as mitochondria in lysosomes. Autophagy is required to provide amino acids and sustain metabolism allowing survival during nutrient starvation1–5. Deregulation of autophagy is involved in numerous disease states such as neurodegenerative disease, metabolic disease and cancer6. In fact, tumor cells upregulate and require autophagy to support their metabolism and enhance their proliferation, survival and malignancy7–9. Moreover, host autophagy can promote tumor growth by providing essential tumor nutrients such as arginine in the circulation or alanine in the local tumor microenvironment1,10–12. In addition to its metabolic role, autophagy regulates the immune response by regulating the immune cell homeostasis and function and suppresses inflammation, which may also play a role in cancer13–15.

In genetically engineered mouse models of cancer, tumors evolve in the presence of an intact immune system but often lack the high TMB that can increase the expression of immunogenic neoantigens normally associated with many human cancers16–18. Immunogenic tumor mutations facilitate recognition and elimination by the immune system, placing selection pressure on the tumor to acquire tolerance and immune escape19. Although immunotherapy overcomes some of these immune escape mechanisms, only a subset of patients respond, necessitating the identification of new approaches to enhance antitumor immune activation20. Host autophagy does not promote growth of low TMB tumors through T-cell antitumor immune response12 but whether this was true in tumors with high TMB was not known.

Results

Autophagy promotes high-TMB tumor growth by suppressing an antitumor T-cell response.

As cell-autonomous autophagy can prevent inflammation and immune response activation13,14, we examined whether host autophagy deficiency could promote inflammation and an antitumor immune response. Analysis of 26 different cytokines and chemokines in serum demonstrated an increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines CCL2, interleukin (IL)-6, CXCL1 and IP10 in conditional whole-body Atg7-deficient mice (Atg7Δ/Δ) in comparison to wild-type (Atg7+/+) mice (Fig. 1a,b and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). These findings are consistent with previous work suggesting that autophagy is necessary to prevent accumulation of pro-inflammatory components and suppress activation of an innate immune response1,13,14,21,22. As host autophagy inhibits inflammation, we sought to determine the role of host autophagy in the growth of high-TMB tumors. To do so, we used autophagy-competent carcinogen-induced MB49 urothelial carcinoma and UV-irradiated BrafV600E/+;Pten−/−;Cdkn2a−/− mouse melanoma UV YUMM1.1–9 cell lines and examined their growth on Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ hosts. To classify the cell line TMB, we used a cutoff of ten nonsynonymous mutations per megabase (Mt/Mb) as previously described23,24. On the basis of this cutoff, we classified MB49 and UV YUMM1.1–9 cell lines as high TMB and the YUMM1.1 and YUMM1.3 unirradiated parent cell lines as low TMB (Supplementary Tables 3–7). In addition, as these cell lines were generated from tumors from male mice, we compared growth on female and male hosts. Specifically in female hosts, the male antigens provoke a strong immune response25.

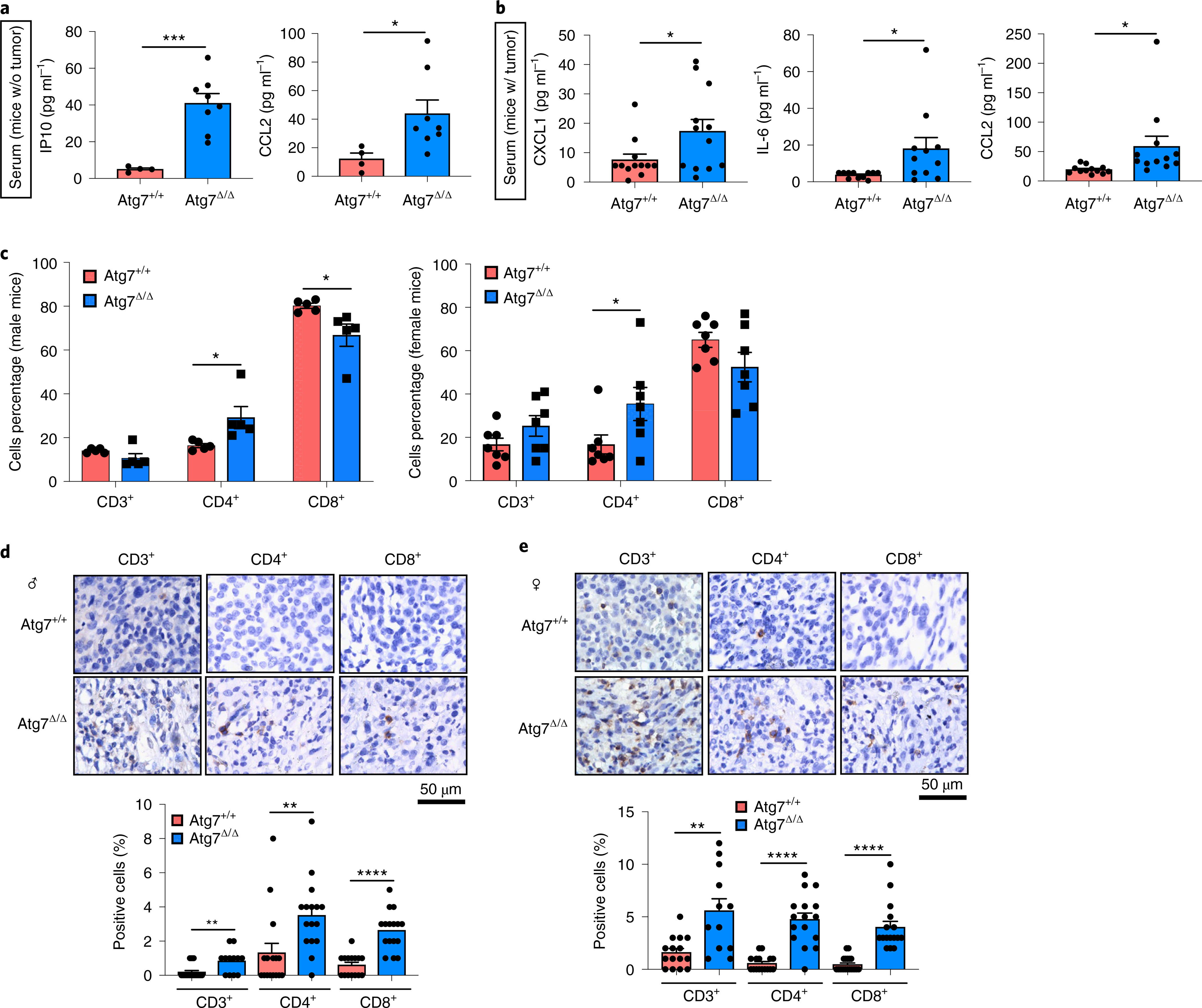

Fig. 1 |. Loss of host autophagy increases the level of circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines and promotes T-cell infiltration in high-TMB tumors.

a, Serum cytokine and chemokine profiling of female and male Atg7+/+ (n = 4 mice) and Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 8 mice) hosts without (w/o) tumors, showing those with significant differences among 26 cytokines and chemokines. b, Serum cytokine and chemokine profiling of female and male Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ hosts with (w/) MB49 tumors (n = 12 tumors each) showing those with significant differences. c, CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ cells (percentage) in high-TMB tumors (MB49) grown on male (n = 5 mice each) and female (n = 7 mice each) Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ hosts analyzed by flow cytometry. These data are representative of three independent experiments. d,e, Representative IHC images and quantification of CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in MB49 tumors from male (d) and female (e) Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ hosts (n = 5 mice each). All data are mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001 using a two-sided Student’s t-test. Source data are available for a–e.

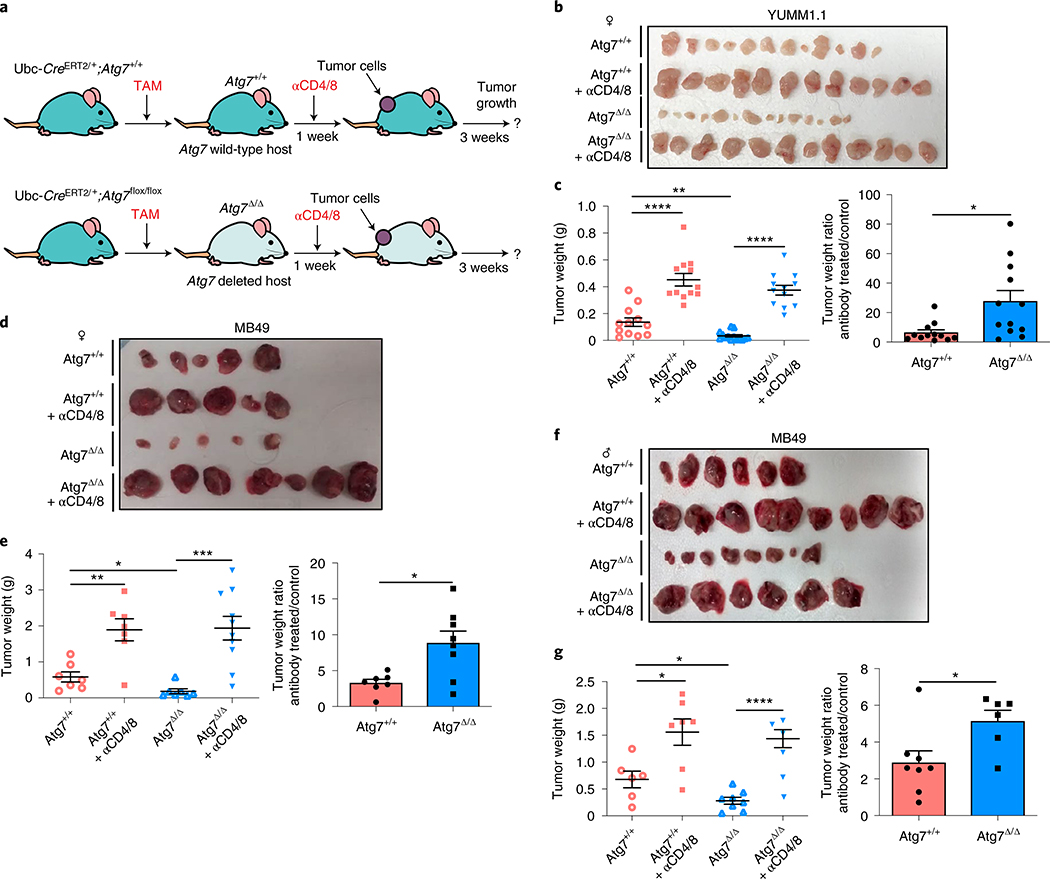

We previously showed that loss of host autophagy does not modify T-cell infiltration into low TMB tumors (e.g. YUMM1.1) and that T-cell depletion was not able to rescue their defective tumor growth on Atg7Δ/Δ compared to Atg7+/+ male hosts26. In contrast, in both male and female hosts, high-TMB tumors (MB49) grown on Atg7Δ/Δ hosts have increased CD4+ T-cell infiltration, as demonstrated by flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry (IHC) for CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ cells (Fig. 1c–e). To validate whether loss of host autophagy potentiates a T-cell immune response in high-TMB tumors, we analyzed tumor growth on Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ hosts with or without T-cell depletion using CD4/8+ antibodies (Fig. 2a and Extended Data Fig. 1a). Unlike that previously shown in male hosts26, on female hosts where male tumors provide a strong male antigen, depletion of T cells by injection of CD4/8+ antibodies was able to stimulate low TMB YUMM1.1 tumor growth in both Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ hosts, but did so to a greater extent in the Atg7Δ/Δ hosts (Fig. 2b,c). Consistent with these data, loss of host autophagy did not increase T-cell infiltration into another low TMB tumor, YUMM1.3 (Extended Data Fig. 1b) and T-cell depletion rescued YUMM1.3 tumor growth in both male and female hosts. Only female mice displayed greater effect in Atg7Δ/Δ compared to Atg7+/+ hosts (Extended Data Fig. 1c–f). Similarly, T-cell depletion increased the growth of the high-TMB MB49 tumors more significantly (*P < 0.05) in both Atg7Δ/Δ female and male hosts (Fig. 2d–g), suggesting that loss of autophagy limits high-TMB tumor growth by augmenting a T-cell immune response. Both helper T cells and cytotoxic T cells are involved in the defective high-TMB tumor growth in Atg7Δ/Δ hosts (Extended Data Fig. 1g,h). Whole-body loss of Atg5, another essential autophagy gene, also decreased the growth of MB49 tumors in a CD4/8+ T-cell-dependent manner (Extended Data Fig. 2a–e). Similar to the loss of Atg7, loss of Atg5 increased CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell infiltration into the tumor (Extended Data Fig. 2f), suggesting that promotion of high-TMB tumor growth is not a function specific to Atg7.

Fig. 2 |. Host autophagy promotes high-TMB tumor growth through a T-cell-dependent mechanism.

a, experimental design to induce host mice with conditional whole-body Atg7 deletion (Atg7Δ/Δ) and the wild-type control (Atg7+/+), without and with T-cell depletion. Ubc-CreERT2/+;Atg7+/+ and Ubc-CreERT2/+;Atg7flox/flox mice were injected with tamoxifen (TAM) to delete Atg7 and were then injected subcutaneously with tumor cells and intraperitoneally with anti-CD4/8. Tumor growth was monitored over 3 weeks, where all tumors establish similarly with antitumor effects becoming apparent beyond 2 weeks. b,c, Comparison of YUMM1.1 tumor growth on female Atg7+/+ (n = 12 tumors), Atg7+/+ + anti-CD4/8 (n = 12 tumors), Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 14 tumors) and Atg7Δ/Δ + anti-CD4/8 (n = 12 tumors). Tumor pictures (b), tumor weight and ratio (antibody treated/control) (c) from the experimental end point. d–g, Comparison of MB49 tumor growth on female (d,e) Atg7+/+ (n = 7 tumors), Atg7+/+ + anti-CD4/8 (n = 7 tumors), Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 7 tumors) and Atg7Δ/Δ + anti-CD4/8 (n = 10 tumors) and male (f,g) Atg7+/+ (n = 6 tumors), Atg7+/+ + anti-CD4/8 (n = 8 tumors), Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 8 tumors) and Atg7Δ/Δ + anti-CD4/8 (n = 6 tumors) hosts. Tumor pictures (d,f), tumor weight and ratio (antibody treated/control) (e,g) from the experimental end point. All data are mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001 using a two-sided Student’s t-test. Source data are available for c,e,g.

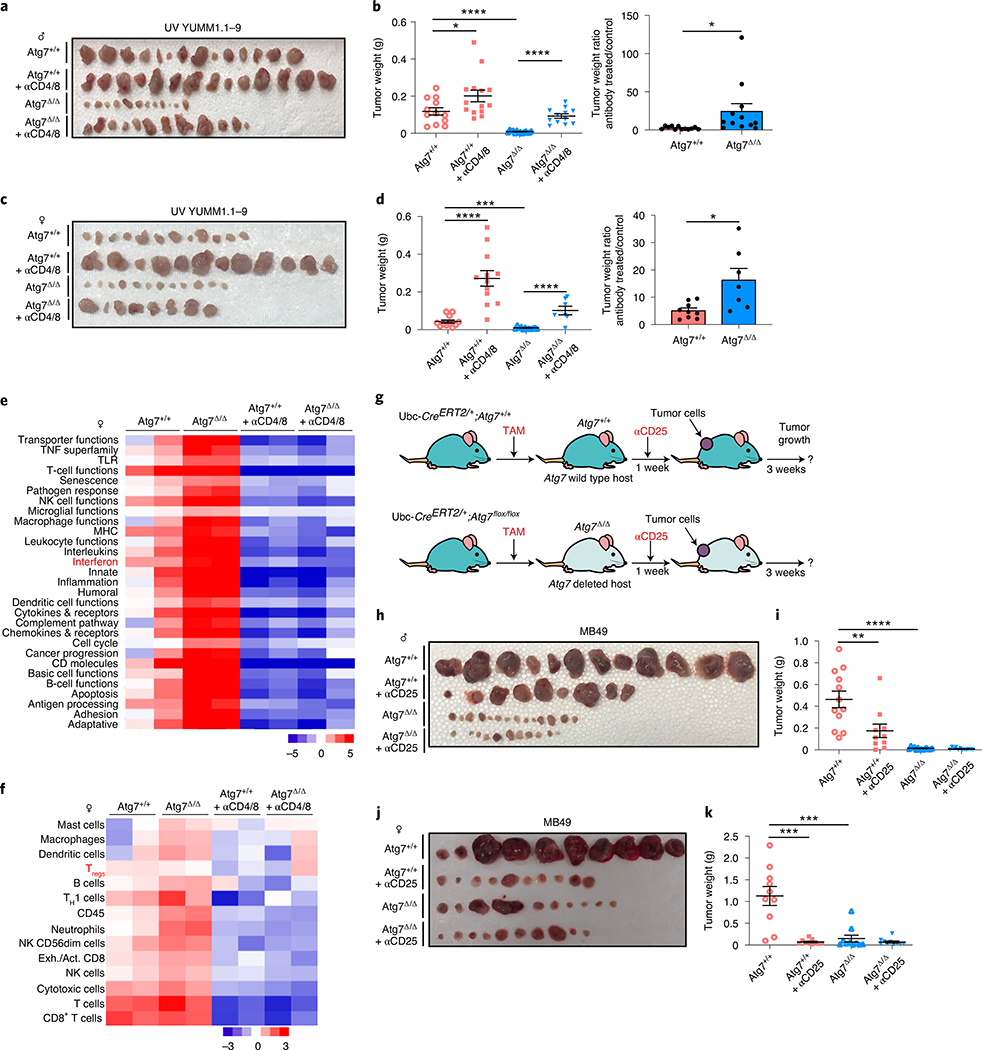

To confirm that other high-TMB tumors are sensitized to T-cell killing on Atg7Δ/Δ hosts, we generated high-TMB derivatives of low TMB YUMM1.1 by UVC irradiation to increase the number of mutations (UV YUMM1.1–9) (Supplementary Tables 3 and 7). As previously shown for YUMM1.1 and MB4926, the UV YUMM1.1–9 tumors show defective growth in the Atg7Δ/Δ compared to Atg7+/+ hosts (Extended Data Fig. 2g,h). Moreover, as with MB49 tumors, T-cell depletion rescues UV YUMM1.1–9 tumor growth in both Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ female and male hosts, but to a greater extent in the Atg7Δ/Δ hosts (Fig. 3a–d). These results confirm that loss of autophagy augments an antitumor T-cell response in the context of high but not low TMB.

Fig. 3 |. Loss of autophagy upregulates an antitumor immune response in a T-cell-dependent manner and increases Treg cells.

a–d, Comparison of UV YUMM1.1–9 tumor growth on male (a,b) Atg7+/+ (n = 14 tumors), Atg7+/+ + anti-CD4/8 (n = 14 tumors), Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 12 tumors) and Atg7Δ/Δ + anti-CD4/8 (n = 12 tumors) and female (c,d) Atg7+/+ (n = 12 tumors), Atg7+/+ + anti-CD4/8 (n = 12 tumors), Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 12 tumors) and Atg7Δ/Δ + anti-CD4/8 (n = 8 tumors). Tumor pictures (a,c), tumor weight and ratio (antibody treated/control) (b,d) from the experimental end point. e,f, NanoString expression analysis of genes involved in signature immune pathways (e) or immune cell type (f) on female Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ hosts with or without anti-CD4/8 (n = 2 mice each). Red, high expression level; blue, low expression level. TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TLR, Toll-like receptor; NK, natural killer; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; TH1, type 1 helper T cells. g, experimental design to induce conditional whole-body Atg7 deletion (Atg7Δ/Δ) and wild-type (Atg7+/+) controls without and with Treg cell depletion. Ubc-CreERT2/+;Atg7+/+ and Ubc-CreERT2/+;Atg7flox/flox mice were injected with TAM to delete Atg7 and were then injected subcutaneously with tumor cells and intraperitoneally with anti-CD25. Tumor growth was monitored over 3 weeks. h–k, Comparison of MB49 tumor growth on male (h,i) Atg7+/+ (n = 12 tumors), Atg7+/+ + anti-CD25 (n = 10 tumors), Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 14 tumors) and Atg7Δ/Δ + anti-CD25 (n = 12 tumors) and female (j,k) Atg7+/+, Atg7+/+ + anti-CD25, Atg7Δ/Δ and Atg7Δ/Δ + anti-CD25 (n = 10 tumors each). Tumor pictures (h,j) and tumor weight (i,k) from the experimental end point. All data are mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 using a two-sided Student’s t-test. Source data are available for b,d,i,k.

Host autophagy promotes high-TMB tumor growth by enhancing Treg cells and T-cell exhaustion.

To understand how host autophagy suppresses high-TMB tumor immunogenicity, we performed immune profiling of MB49 tumors from both Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ hosts with or without T-cell depletion. To do so, we analyzed the expression of 750 genes involved in the adaptive, humoral and innate immunity and inflammation. The overall immune response was upregulated in tumors at the RNA level from Atg7Δ/Δ hosts in a T-cell-dependent manner (Fig. 3e, Extended Data Fig. 3a and Supplementary Table 8). Immune profiling also identified a decrease in regulatory T (Treg) cell gene expression, which was associated with a decrease in FOXP3 protein expression by IHC (Fig. 3f and Extended Data Fig. 3b). As loss of Atg16l1, an autophagy component, in dendritic cells impairs Treg cell induction and function27 and loss of autophagy in Treg cells inhibits their activity and facilitates tumor clearance28, we examined whether loss of Treg cells was responsible for defective high-TMB tumor growth on Atg7Δ/Δ hosts.

MB49 tumors were grown on Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ hosts with or without Treg cell depletion with CD25 antibody (Fig. 3g). CD25 antibody led to a decrease in FOXP3+ Treg cells without affecting total CD4+ T cells or CD8+ T cells (Extended Data Fig. 3c,d). Treg cell depletion decreased tumor growth on male and female Atg7+/+ hosts and had no effect on Atg7Δ/Δ hosts, thus phenocopying tumor growth on Atg7Δ/Δ hosts (Fig. 3h–k). As Treg cells in the microenvironment can promote intratumoral T-cell exhaustion29, we determined whether Atg7Δ/Δ hosts decreased T-cell exhaustion by analyzing the expression of the T-cell exhaustion markers: PD1, TIM3 and LAG3. Intratumoral CD4+ T cells from Atg7Δ/Δ hosts showed a significant (*P < 0.05) decrease in expression of all the T-cell exhaustion markers and CD8+ T cells showed a significant (*P < 0.05) decrease expression of TIM3 (Fig. 4a,b). These findings suggest that loss of host autophagy reduces T-cell exhaustion in high-TMB tumors.

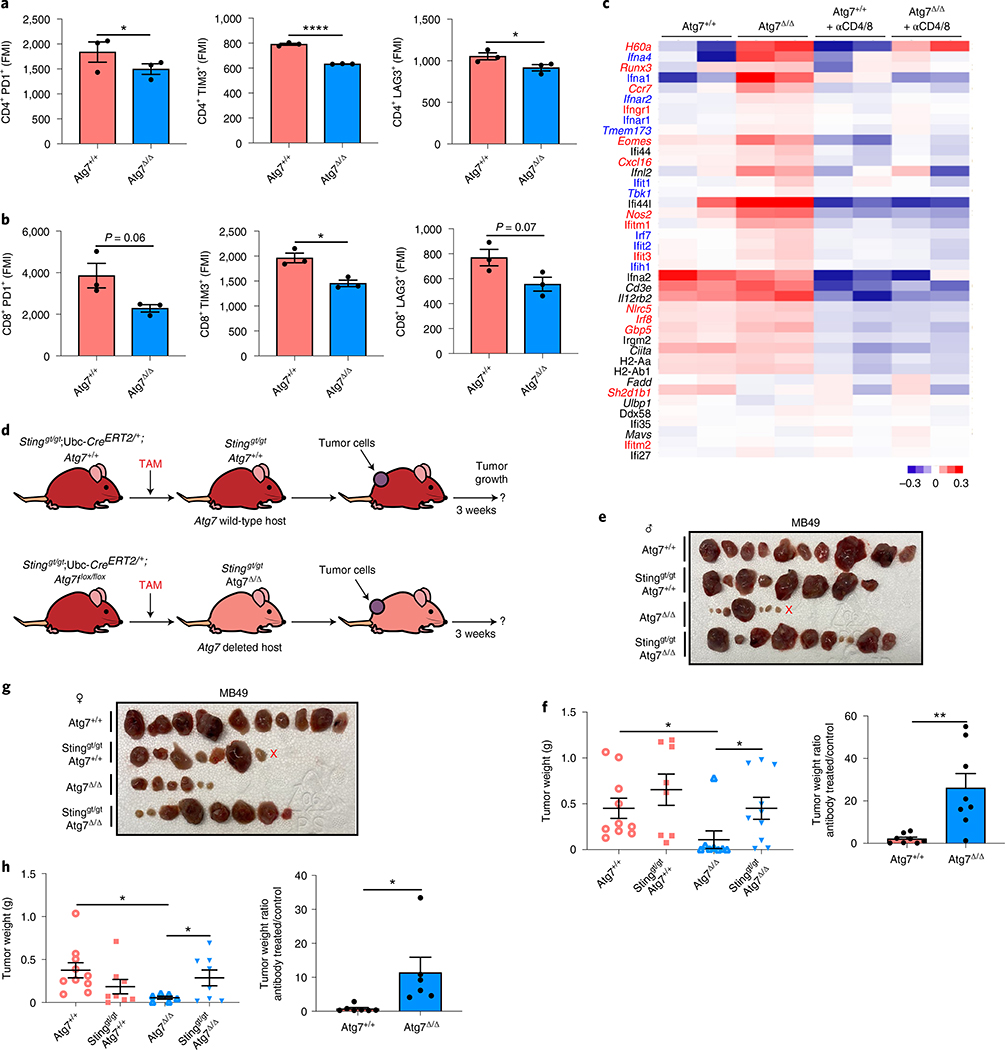

Fig. 4 |. Host autophagy promotes high-TMB tumor growth through suppression of Sting.

a, Percentage of CD4+PD1+, CD4+TIM3+ and CD4+LAG3+ cells in tumors in male Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ hosts (n = 3 tumors each) analyzed by flow cytometry. These data are representative of three independent experiments. MFI: mean fluorescent intensity. b, Percentage of CD8+PD1+, CD8+TIM3+ and CD8+LAG3+ cells in tumors in male Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ hosts (n = 3 tumors each) analyzed by flow cytometry. c, NanoString expression analysis of genes involved in the IFN pathway in MB49 tumors from female Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ hosts with or without anti-CD4/8 (n = 2 mice each). Blue genes indicate IFN-αβ, red genes indicate IFN-γ pathways. Red: high expression level; blue: low expression level. d, experimental design to induce conditional whole-body Atg7 deletion (Atg7Δ/Δ) and wild-type (Atg7+/+) controls with loss of Sting. Stinggt/gt;Ubc-CreERT2/+;Atg7+/+ and Stinggt/gt;Ubc-CreERT2/+;Atg7flox/flox mice were injected with TAM to delete Atg7 and were then injected subcutaneously with tumor cells. Tumor growth was monitored over 3 weeks. e–h, Comparison of MB49 tumor growth on male (e,f) Atg7+/+(n = 10 tumors), Stinggt/gt;Atg7+/+(n = 8 tumors), Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 8 tumors) and Stinggt/gt;Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 10 tumors) and female (g,h) Atg7+/+ (n = 10 tumors), Stinggt/gt;Atg7+/+ (n = 8 tumors), Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 6 tumors) and Stinggt/gt;Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 8 tumors). Tumor pictures (e,g) and tumor weight and ratio (antibody treated/control) (f,h) from the experimental end point. All data are mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001 using a two-sided Student’s t-test. Source data are available for a,b,f,h.

Host autophagy limits IFN type I and II responses and antigen presentation enabling high-TMB tumor growth.

One of the pathways upregulated in the tumor immune profiling from Atg7Δ/Δ hosts was the interferon (IFN) pathway (Fig. 3e). Genes involved in the IFN-α/β pathway or known to positively regulate IFN-α/β production (Ifna4, Ifna1, Ifnar2, Ifnar1, Tmem173, Ifit1, Tbk1, Irf7, Ifit2 and Ifih1) (indicated in blue) were increased in tumors grown on Atg7Δ/Δ hosts (Fig. 4c). One of those genes, Sting (Tmem173) activates IFN-α/β in response to cytosolic DNA including mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). Parkin/PINK1-mediated mitophagy, a specific form of autophagy for mitochondria, restrains innate immunity through curtailing STING activation by mtDNA30. To test whether Atg7 inhibited Sting to promote tumor growth, we generated conditional whole-body Atg7-deficient mice on the background of Sting deficiency (Stinggt/gt; Ubc-CreERT2/+;Atg7flox/flox) (Fig. 4d).

Sting deficiency did not affect the survival or phenotype of the Atg7Δ/Δ mice, as double knockout mice displayed steatosis and death from neurodegeneration between 2–3 months post-deletion, identical to Atg7Δ/Δ singly deleted mice (Extended Data Fig. 3e). Whole-body loss of Sting, however, rescued MB49 tumor growth on both male and female Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ hosts. As described earlier for T-cell depletion, Stinggt/gt and Atg7Δ/Δ double knockout hosts had a greater increase in tumor growth than Stinggt/gt and Atg7+/+ single knockout hosts, indicating that Atg7 suppressed an antitumor T-cell response by limiting Sting (Fig. 4e–h).

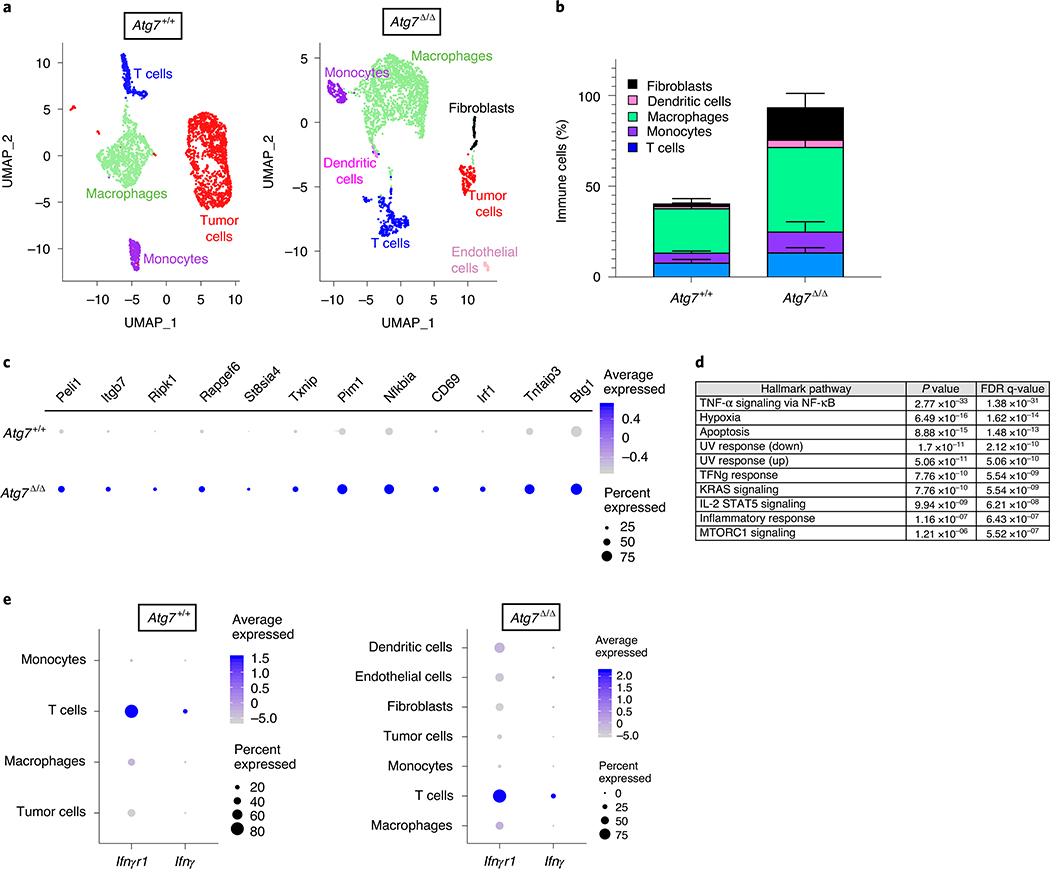

Tumor immune profiling also identified upregulation of the IFN-γ pathway in tumors grown on Atg7Δ/Δ hosts. Indeed, several genes involved in the IFN-γ pathway, or known to positively regulate IFN-γ production (indicated in red), were increased in tumors grown on Atg7Δ/Δ hosts (Ifit3, H60a, Nos2, Ccr7, Runx3, Eomes, Ifitm1, Gbp5, Nlrc5, Irf8, Cxcl16, Ifitm2 and Ifngr1), whereas Sh2d1b1, a negative regulator of IFN-γ, was decreased (Fig. 4c). To better understand how loss of autophagy alters the immune microenvironment and signaling pathways, we performed single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) on tumors from female Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ hosts. The cells were clustered and then identified based upon expression of known marker genes (Supplementary Table 9). Tumors from Atg7Δ/Δ hosts were characterized by an increase in immune cell fractions including T cells, macrophages, monocytes, dendritic cells and fibroblasts compared to tumors from Atg7+/+ hosts (Fig. 5a,b, Extended Data Fig. 3f and Supplementary Table 10). Consistent with the tumor immune profiling (Fig. 4c), the IFN-γ pathway was upregulated in tumor-infiltrated T cells from Atg7Δ/Δ compared to Atg7+/+ hosts, as shown by an increase in Peli1, Itgb7, Ripk1, Rapgef6, St8sia4, Txnip, Pim1, Nfkbia, CD69, Irf1, Tnfaip3 and Btg1 gene expression (Fig. 5c,d). Moreover, IFN-γ expression was predominantly associated with T cells as these cells highly expressed Ifngr1 and Ifng (Fig. 5e). Thus, we hypothesized that loss of host autophagy augments STING/IFN-α/β signaling thereby augmenting a T-cell immune response and IFN-γ production that promotes tumor regression. To test this hypothesis, we generated conditional whole-body Atg7-deficient mice on the background of Ifnγ deficiency (Ifnγ−/−; Ubc-CreERT2/+;Atg7flox/flox) (Fig. 6a).

Fig. 5 |. Loss of autophagy increases immune cell fraction and IFN-γ pathway gene expression.

a, Representative scRNA-seq uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) projection of cell cluster from tumors from female Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ hosts (n = 1 tumor each). These data are representative of two independent experiments with two tumors from Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ hosts each. b, Immune cell fractions in tumors from female Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ hosts (n = 4 tumors each). All data are mean ± s.e.m. c, Dot plot of differential IFN-γ pathway gene expression in tumors infiltrated T cells from female Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ hosts (n = 2 tumors each). d, Top ten pathways enriched in tumor-infiltrated T cells from Atg7Δ/Δ hosts compared to Atg7+/+ hosts (n = 2 tumors each). NF-κB, nuclear factor κB; FDR, false discovery rate. e, Dot plot of differential gene expression (Ifnγr1 and Ifnγ) in tumors and tumor-infiltrated immune cells from female Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ hosts (n = 2 tumors each).

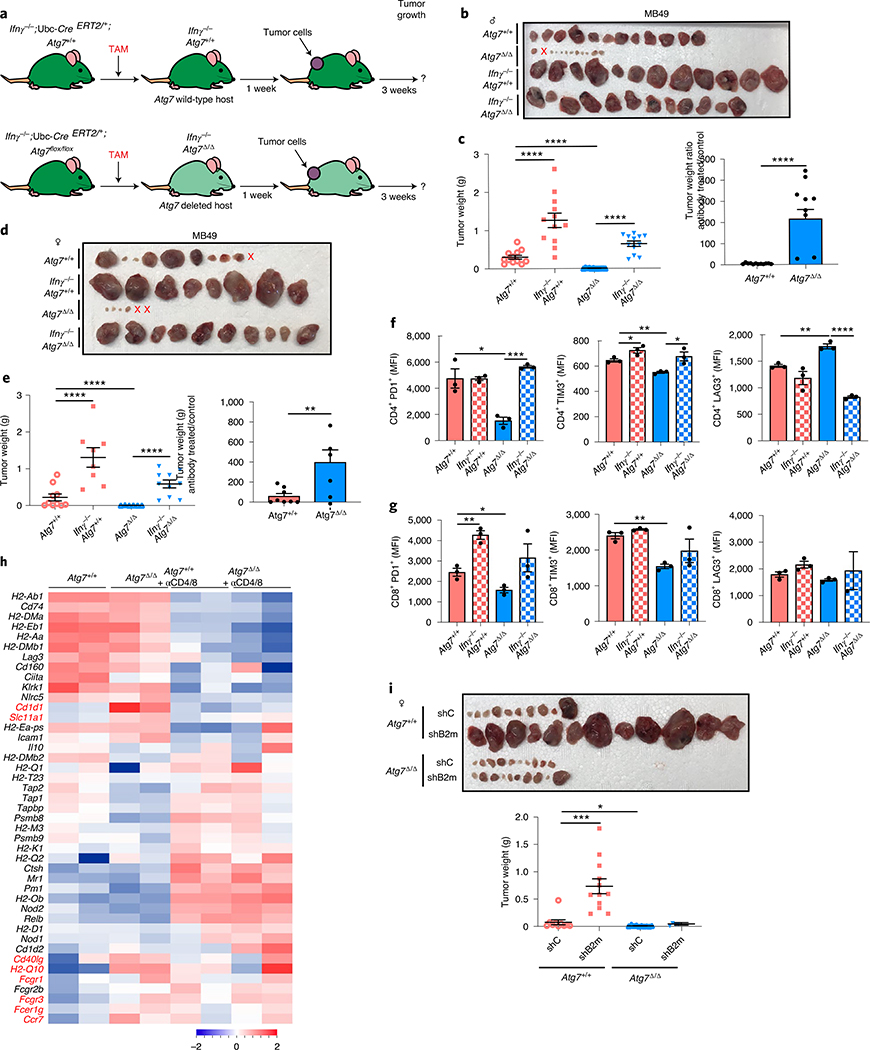

Fig. 6 |. Loss of autophagy decreases tumor growth in an IFN-γ- and MHC-I-dependent manner.

a, experimental design to induce conditional whole-body Atg7 deletion (Atg7Δ/Δ) and wild-type (Atg7+/+) controls with loss of Ifnγ. Ifnγ−/−;Ubc-CreERT2/+;Atg7+/+ and Ifnγ−/−;Ubc-CreERT2/+;Atg7flox/flox mice were injected with TAM to delete Atg7 and were then injected subcutaneously with tumor cells. Tumor growth was monitored over 3 weeks. b–e, Comparison of MB49 tumor growth on male (b,c) Atg7+/+, Ifnγ−/−;Atg7+/+, Atg7Δ/Δ and Ifnγ−/−;Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 12 tumors each) and female (d,e) Atg7+/+ (n = 10 tumors), Ifnγ−/−;Atg7+/+ (n = 8 tumors), Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 6 tumors) and Ifnγ−/−;Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 10 tumors). Tumor pictures (b,d) and tumor weight and ratio (antibody treated/control) (c,e) from the experimental end point. f, Percentage of CD4+PD1+, CD4+TIM3+ and CD4+LAG3+ cells in tumors in male Atg7+/+, Ifnγ−/−;Atg7+/+, Atg7Δ/Δ and Ifnγ−/−;Atg7Δ/Δ hosts (n = 3 tumors each) analyzed by flow cytometry. g, Percentage of CD8+PD1+, CD8+TIM3+ and CD8+LAG3+ cells in tumors in male Atg7+/+, Ifnγ−/−;Atg7+/+, Atg7Δ/Δ and Ifnγ−/−;Atg7Δ/Δ hosts (n = 3 tumors each) analyzed by flow cytometry. h, NanoString expression analysis of genes involved in the MHC and antigen presentation pathway in MB49 tumors from female Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ hosts with or without anti-CD4/8 (n = 2 tumors each). Red genes indicate MHC pathway. Red: high expression level; blue: low expression level. i, Comparison of MB49 shC and shB2m tumor growth on female Atg7+/+ (n = 10–12 tumors) and Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 10 tumors) hosts. Tumor pictures and tumor weight from the experimental end point. All data are mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001 using a two-sided Student’s t-test. Source data are available for c,e–g,i.

Ifnγ deficiency did not affect the survival or phenotype of the Atg7Δ/Δ mice, as double knockout mice displayed steatosis and death from neurodegeneration between 2–3 months after deletion, identical to Atg7Δ/Δ singly deleted mice (Extended Data Fig. 4a,b). Loss of Ifnγ, however, was able to rescue MB49 and UV YUMM1.1–9 tumor growth on both male and female Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ hosts. As described earlier for Sting loss or T-cell depletion, Ifnγ−/− and Atg7Δ/Δ double knockout hosts had a greater increase in tumor growth than Ifnγ−/− and Atg7+/+ single knockout hosts (Fig. 6b–e and Extended Data Fig. 4c–f). Ifnγ deficiency increased CD4+ T-cell exhaustion markers in Atg7Δ/Δ hosts to a level similar to Atg7+/+ hosts, confirming that T-cell immune response regulation by autophagy involves Ifnγ (Fig. 6f,g).

IFN-γ can induce the expression of major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and II and can upregulate antigen presentation and processing31. Several genes from MHC class I and II and genes involved in antigen presentation and processing such as Cd1d1, Slc11a1, Cd40lg, H2-Q10, Fcgr1, Fcgr3, Fcergr1 and Ccr7 were increased in tumors grown on Atg7Δ/Δ hosts (Fig. 6h). Knockdown of β−2-microglobulin (B2m), an essential MHC class I component, promoted the growth of the MB49 tumors in Atg7+/+ but not in Atg7Δ/Δ hosts and loss of Atg7 led to re-expression of B2M protein in the shB2m tumors (Fig. 6i and Extended Data Fig. 4g) consistent with similar findings in pancreatic cancers32. Altogether, our data suggest that IFN-γ mediates defective growth of high-TMB tumors on the autophagy-deficient hosts, probably through an increase in MHC class I expression and antigen presentation.

Hepatic autophagy enables growth of high-TMB tumors.

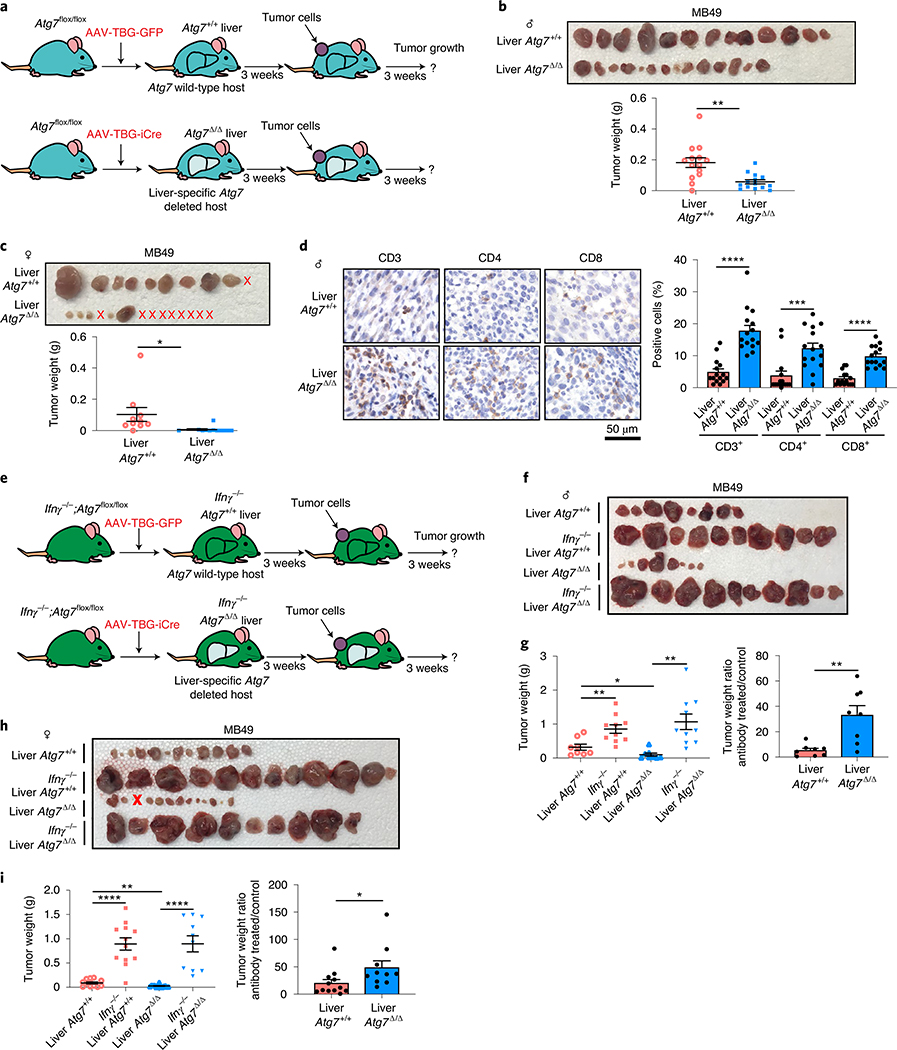

The liver is a key source of inflammatory mediators and autophagy is critical to prevent liver damage2. Similar to serum from Atg7Δ/Δ hosts (Fig. 1a,b and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2), serum and liver tissue from hepatocyte-specific Atg7Δ/Δ hosts showed an increase in pro-inflammatory cytokines (Extended Data Fig. 5a,b and Supplementary Tables 11 and 12). Specific loss of autophagy in the liver was sufficient to prevent MB49 tumor growth in both male and female hosts and to increase CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell infiltration (Fig. 7a–d). Moreover, as seen in Atg7Δ/Δ hosts, loss of Ifnγ in hepatocyte-specific Atg7Δ/Δ hosts rescued high-TMB tumor growth (Fig. 7e–i). Thus, host autophagy, and more specifically liver hepatocyte autophagy, suppresses inflammation and an antitumor T-cell response.

Fig. 7 |. Liver autophagy is necessary to maintain tumor growth in an IFN-γ-dependent manner.

a, experimental design to induce liver hepatocyte-specific Atg7 deletion (liver Atg7Δ/Δ) and wild-type controls (liver Atg7+/+). Atg7flox/flox mice were either injected with adeno-associated virus (AAV)–thyroxine binding globulin (TBG) promoter–GFP or AAV–TBG–iCre and MB49 cells were then injected subcutaneously and tumor growth was monitored over 3 weeks. b,c, Comparison of MB49 tumor growth on male (b) liver Atg7Δ/Δ and liver Atg7+/+ (n = 14 tumors each) and female (c) liver Atg7Δ/Δ and liver Atg7+/+ (n = 10 and 14 tumors, respectively). Tumor pictures and weight from the experimental end point. d, Representative IHC images and quantification of CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in MB49 tumors from male liver Atg7+/+ and liver Atg7Δ/Δ hosts (n = 5 mice each). e, experimental design to induce conditional liver-specific liver Atg7Δ/Δ and liver Atg7+/+ controls with loss of Ifnγ. The Ifnγ−/−;Atg7flox/flox were either injected with AAV–TBG–GFP or AAV–TBG–iCre and MB49 cells were then injected subcutaneously and tumor growth was monitored over 3 weeks. f–i, Comparison of MB49 tumor growth on male (f,g) liver Atg7+/+ (n = 8 tumors), Ifnγ−/−;liver Atg7+/+ (n = 10 tumors), liver Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 8 tumors) and liver Ifnγ−/−;Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 10 tumors) and female (h,i) liver Atg7+/+ (n = 12 tumors), Ifnγ−/−;liver Atg7+/+ (n = 12 tumors), liver Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 12 tumors) and liver Ifnγ−/−;Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 10 tumors). Tumor pictures (f,h) and tumor weight and ratio (antibody treated/control) (g,i) from the experimental end point. All data are mean ± s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 using a two-sided Student’s t-test. Source data are available for b–d,g,i.

Autophagy, but not LAP, enables high-TMB tumor growth in a T-cell-dependent manner.

It was previously shown that LC3-associated phagocytosis (LAP) in macrophages and not canonical autophagy promotes B16F10 melanoma growth through immune tolerance33. As Atg7 and Atg5 are involved in both autophagy and LAP, we assessed whether liver-specific Fip200 deletion, a gene involved in autophagy and not LAP, inhibited high-TMB tumor growth (Extended Data Fig. 5c,d). Similar to loss of Atg7 or Atg5, liver-specific Fip200 deletion was sufficient to decrease the growth of high-TMB tumors (Extended Data Fig. 5e). Moreover, using injection of lentivirus CRISPR scramble or targeting Fip200, we analyzed whether Fip200 deletion inhibited high-TMB tumor growth with T-cell depletion (Extended Data Fig. 5f). Lentivirus CRISPR Fip200 led to the presence of INDELs in amplicons and mosaic deletion of Fip200 associated with increased p62 aggregates (Extended Data Fig. 5g,h). Similar to loss of Atg7 or Atg5, mosaic loss of Fip200 in the liver led to decreased growth of high-TMB tumors in a T-cell-dependent manner (Extended Data Fig. 5i,j), suggesting that autophagy and not LAP promotes high-TMB tumor growth by suppressing an antitumor immune response.

Discussion

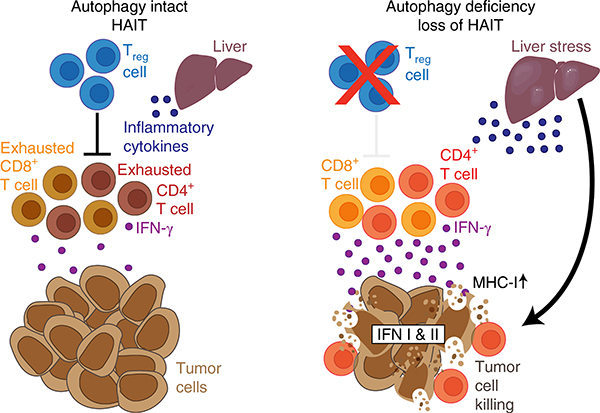

While immune cell-specific loss of autophagy indicates that autophagy is required for CD4+ T-cell function and CD8+ memory T-cell formation34,35, we demonstrated that liver hepatocyte autophagy mediates immune tolerance of high-TMB tumors. Autophagy, especially in hepatocytes, suppresses an antitumor immune response through STING pathway inhibition, which represses an antitumor T-cell response and IFN-γ production, allowing the growth of high-TMB tumors (Fig. 8). This is consistent with data recently showing that specific loss of autophagy in T cells decreases tumor growth and is associated with greater production of IFN-γ by T cells36.

Fig. 8 |. Model depicting hepatic autophagic immune tolerance.

Loss of host autophagy promotes high-TMB tumor growth through immune response inhibition. Autophagy, especially in the liver, suppresses inflammation, antitumor T-cell activity and IFN type I and II responses, allowing the growth of high-TMB tumors. HAIT, hepatic autophagy immune tolerance.

While the exact signaling between the liver and the tumor microenvironment still needs to be elucidated, our data suggest that loss of autophagy upregulates IFN-γ, which in turn increases MHC class I expression and antigen presentation, which mediates defective growth of high-TMB tumors. Direct demonstration of enhanced antigen presentation and T-cell recognition in the autophagy-deficient hosts in the context of high-TMB tumors may also be informative. Our experiments also suggest that loss of autophagy is downregulating Treg cell functions and T-cell exhaustion, leading to tumor growth regression. While we demonstrated that the use of CD25 antibody decreased specifically FOXP3+ Treg cells without affecting CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, it might still be of interest to use FOXP3+ antibody or a FOXP3-deleted mouse (DEREG mouse) to more specifically target Treg cells.

Release of mtDNA from mitochondria can induce STING in hepatocytes, leading to liver inflammation and steatosis37. Given that loss of liver autophagy promotes an antitumor T-cell response dependent on IFN-γ, we hypothesize that it may be triggered by mtDNA release in hepatocytes, which activates the STING/type I IFN response and subsequent induction of a T-cell antitumor immune response and type II IFN signaling.

Thus, host autophagy, and more specifically autophagy in the hepatocytes, can promote tumor growth through different mechanisms depending on mutational load: by inhibiting a T-cell immune response in high-TMB tumors, designated hepatic autophagy immune tolerance (Fig. 8) or by sustaining circulating arginine in low TMB tumors26. These findings highlight the importance of understanding how host autophagy outside of the tumor microenvironment can induce an antitumor immune response to enable rational application of autophagy inhibitors to improve responses to immunotherapy38.

Methods

Mice.

All animal care and treatments were carried out in compliance with Rutgers University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines. Mice for conditional whole-body Atg7 (ref. 2) or Atg5 (ref. 39) deletion (C57Bl/6J Ubc-CreERT2/+;Atg7flox/flox and Ubc-CreERT2/+;Atg5flox/flox, respectively) were used as previously described12. Mice deficient for Ifnγ with whole-body conditional Atg7 deletion were obtained following breeding of the Ubc-CreERT2/+;Atg7flox/flox mice and Ifnγ−/− mice (obtained from Jackson Laboratories). Mice deficient for Sting with whole-body conditional Atg7 deletion were obtained following breeding of the Ubc-CreERT2/+;Atg7flox/flox mice and Stinggt/gt mice (obtained from Jackson Laboratories). To assess the consequence of acute Atg7 deletion on tumorigenesis of C57Bl/6J isogenic male tumor cells, 1 week after TAM treatment, MB49 (0.25 × 106 cells), YUMM1.1 (1 × 106 cells) or UV YUMM1.1–9 (1 × 106 cells) cells were resuspended in 100 μl PBS and injected subcutaneously into the dorsal flanks of mice (two tumors per mouse). At 3 weeks after cell injection, mice were killed and serum, liver and tumors were collected. Mice for liver-specific deletion of Atg7 or Fip200 were generated as previously described with an AAV–TBG–iCre (Vector BioLabs) and AAV–TBG–GFP26. Fip200flox/flox mice have been described previously40. Mice for whole-body deletion of Fip200 were generated using lentivirus CRISPR scramble or Fip200. C57Bl/6J female mice were tail vein injected with 1.8 × 108 transducing units of lentivirus CRISPR scramble or Fip200 (2 Fip200 gRNA: GGGACACACTGCCGGACATA and ACACGTGGAAACGAGGGCTT) to generate Fip200+/+ and Fip200Δ/Δ mice. At 3 weeks after virus injection, MB49 cells (0.25 × 106 cells) were resuspended in 100 μl PBS and injected subcutaneously into the dorsal flanks of the liver-specific Atg7Δ/Δ and Atg7+/+ control mice. At 3 weeks after cell injection, mice were killed and serum and tumors were collected.

Cell lines.

Cell culture.

YUMM1.1, YUMM1.3 (ref. 41) and UV YUMM1.1–9 cells (derived from BrafV600E/+;Pten−/−;Cdkn2−/− C57Bl/6J mouse melanomas) were cultured in DMEM and Ham’s F12 (DMEM-F12) (10–092-CV, Corning) supplemented with 10% FBS (F0926, Sigma) in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. YUMM1.1 were irradiated with 10 mJ cm−2. Cells were given time to recover before being re-plated. Single cells were then clonally expanded to generate UV YUMM cell lines. The MB49 (ref. 42) cell line was cultured in RPMI (11875–093, Gibco).

ShRNA knockdown.

Stable shB2m knockdown MB49 cell lines were generated using shRNA for B2m (TRCN0000295705, Sigma) and shRNA scramble and following lipofectamine transfection reagent manufacturer’s protocol.

Antibody depletion.

For T-cell depletion, 1 week after TAM and every 5 d, 200 μg CD4 (clone GK1.5; BE003–1, BioXCell) and CD8 (clone 2.43; BE0061, BioXCell) antibodies were injected intraperitoneally into Atg7Δ/Δ and Atg7+/+ mice. At 2 d after the first antibody injection, MB49 (0.25 × 106 cells), YUMM1.1 (1 × 106 cells) or UV YUMM1.1–9 (1 × 106 cells) cells were resuspended in 100 ml PBS and injected subcutaneously into the dorsal flanks of the mice. At 3 weeks after cell injection, mice were killed and tumors and spleens were collected.

For Treg cell depletion, 3 d after TAM and every week, 250 μg of CD25 (clone PC-61.5.3; BE0012, BioXCell) antibody was injected intraperitoneally into Atg7Δ/Δ and Atg7+/+ hosts. At 4 d after the first antibody injection, MB49 (0.25 × 106 cells) cells were resuspended in 100 ml PBS and injected subcutaneously into the dorsal flanks of the mice. At 3 weeks after cell injection, mice were killed and tumors and spleens were collected.

Flow cytometry.

Tumors were homogenized in RPMI medium (Gibco, supplemented with 10% FBS) using a gentleMACS Octo Dissociator (Miltenyi Biotec) according to manufacturer’s protocol and passed through a 70-mm cell restrainer. Spleens were grounded with a rubber grinder through steel mesh, treated with ACK Lysis buffer to remove erythrocytes and passed through a 70-mm cell restrainer. Nonspecific binding of antibodies to cell Fc receptors was blocked using 10 μl per 107 cells of FcR blocking reagent (Miltenyi Biotec). Cell surface immunostaining was performed with the following antibodies: CD11c (1:50 dilution, clone N418, 61–0114-82), CD4 (1:500 dilution, clone GK1.5, 17–0041-82), CD3 (1:300 dilution, clone 17A2, 56–0032-82), CD11b (1:300 dilution, clone M1/70, A15390; eBioscience); and CD45 (1:200 dilution, clone 30-F11, 103107) and CD8 (1:500 dilution, clone 53.67, 100749; BioLegend). For T-cell exhaustion, the following antibodies were used: CD45 (REA737, 1:50 dilution, 130–110-802), CD4 (REA604, 1:50 dilution, 130–118-852), CD8 (REA601, 1:10 dilution, 130–109-247; Miltenyi Biotec); CD3 (500A2, 1:500 dilution 152315), PD1 (29F.1A12, 1:300 dilution, 135213), TIM3 (RMT3–23, 1:100 dilution, 119721) and LAG3 (C9B7W, 1:50 dilution, 125219; BioLegend).

The antibodies used were conjugated to FITC, PE, PerCP-Vio700, AF647, AF700, APC-Cy7 or BV 421, 605, 711 or 785. Fixable viability dye eFluor 506 was used for dead cell exclusion. After staining of surface markers, cells were fixed and permeabilized using a commercially available transcription factor staining buffer set (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and stained with FoxP3-eFluor450 (FJK-16s, 1:500 dilution; eBioscience). Data were acquired using an LSR-II flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo software (Tree Star). Live lymphocytes were gated using forward scatter area (FSC-A) versus side scatter area (SSC-A) for selection of lymphocytes, then forward scatter width versus height and side scatter width versus height for double exclusion and finally the viability dye-negative population was selected to exclude dead cells. Populations were gated as follows: CD45 (%CD45+ of total live lymphocytes), CD3 (%CD3+ of CD11b−, CD11c−, CD45+), CD8 (%CD8+ of CD3), CD4 (%CD4+ of CD3), PD1 (%PD1 of CD4 or CD8), TIM3 (%TIM3 of CD4 or CD8) and LAG3 (%LAG3 of CD4 or CD8).

Cytokines and chemokines assay.

Cytokine and chemokine levels were determined using the Cytokine & Chemokine 26-Plex Mouse ProcartaPlex Panel 1 (EPX260–26088-901, Invitrogen). Data were collected using a Luminex-200 system (Luminex) and validated using the xPONENT software package (Luminex).

NanoString assay.

Tumor gene expression was determined using nCounter PanCancer Mouse Immune Profiling Panel (XT-CSO-MIP1–12, NanoString). Data analysis was performed with nSolver software and heat maps were created with Cluster v.3.0 and Java Treeview.

Whole-exome sequencing.

DNA was extracted from MB49, YUMM1.1 and UV YUMM1.1–9 cell lines using the QIAsymphony DSP DNA midi kit (937255, QIAGEN). Mouse whole-exome libraries were constructed using Agilent SureSelect Mouse All Exon kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The resulting sequencing libraries were analyzed using Agilent D1000 screentape and quantified using KAPA qPCR. Libraries were then normalized and pooled into one pool. The library pool was then clustered and sequenced on the Illumina NextSeq550 instrument using 2 × 151 bp paired-end reads to a mean depth of 80×, following the manufacturer’s protocols.

Exome sequenced fastq files were probed for quality control using FastQC (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc) followed by alignment to mouse reference genome (mm10 UCSC) using default Burrows-Wheeler Aligner-MEM (bwa-0.7.5a) (http://arxiv.org/abs/1303.3997). Post-alignment processing followed the Genome Analysis ToolKit best practices workflow43, including sam to bam file conversion, marking duplicates (Picard), base recalibration and preparing files for calling somatic mutation. Final processed bam files from MB49, YUMM1.1 and UV YUMM1.1–9 samples were used to call somatic single-nucleotide variants using Mutect (v.1.1.4)44 algorithm. In addition to Mutect default filters, we used read depth of 14× (UV YUMM1.1–9) and 8× (YUMM1.1 and MB49) as another filter to remove variants with low sequencing depth. Somatic variants were annotated using online VEP45 to classify/predict consequences of these coding variants and removed known single-nucleotide polymorphisms from the final variants. To identify mutational load for MB49 and YUMM1.1, we used VarScan46 mpileup2snp (with creating mpileup files using Samtools mpileup –q 40 –Q 25) and annotated using VEP online server.

Single-cell RNA-seq.

Resected mouse tumors from Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ hosts were placed in complete medium supplemented with 10% FBS and kept on ice. Dissociation of the tumor tissue was carried out using a commercially available mouse tumor dissociation kit and the Miltenyi GentleMACS dissociation system (Miltenyi Biotec). Isolated cells were filtered through a 40-mm mesh strainer and peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated by density-dependent centrifugation. Cells were washed in complete medium (10% FBS), then counted and assessed for viability using a Countess II cell counter (Invitrogen). Cells were then suspended to 1 × 106 ml−1 in complete medium (10% FBS) for single-cell emulsion preparation.

scRNA-seq libraries were prepared according to 10X Genomics specifications. Independent cell suspensions were loaded for droplet-encapsulation by the Chromium Controller (10X Genomics). Single-cell cDNA synthesis, amplification and sequencing libraries were generated using the Single Cell 5′ Reagent kit following the manufacturer’s instructions. The libraries were shipped on dry ice to Novogene and sequenced in a single lane of an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 (settings: Read1: 26, i7: 8, Read2: 91, for 200 Mbp paired-end reads per sample).

Single-cell RNA-seq analysis.

The scRNA-seq dataset from 10X Genomics was processed using CellRanger Single-Cell Software Suite (v.3.1.0, 10X Genomics) using mm10 mouse genome as the reference. CellRanger pipeline output under “filtered_feature_bc_matrix” was used for further data preprocessing and analysis using Seurat R toolkit47 for all samples. We used default parameters for the Seurat pipeline unless stated otherwise. The individual samples dataset underwent quality control for removing any cells with fewer than 200 genes per cell or >5,000 genes per cell and greater than 20% reads mapped to mitochondrial genes. Using these criteria, we recovered ~90% of the cells (Supplementary Table 13). Filtered gene expression matrix for each cell was then normalized (logNormalize) by total expression with an arbitrary scaling factor of 10,000 and log transformation of the gene expression matrix. A principal-component analysis was performed on the top 2,000 most-variable genes (using selection.method of vst). A graph-based clustering approach was implemented on the first ten principal components to separate cell populations into distinct clusters (FindClusters using resolution of 0.5). The data were then visualized using the UMAP option in Seurat. The differentially expressed genes (DEgenes) test was conducted for each cluster using a nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-rank test (and with min.pct of 0.25, logfc. threshold of 0.25) to identify cluster-specific gene expression and a plot of the top ten DEgenes heat map created for each sample. Using cluster-specific top DEgenes, manual annotation was performed to identify distinct cell types or annotate cell type to specific clusters such as tumor cell, T cell, macrophages, monocytes, dendritic cells and fibroblasts (Supplementary Table 9). Moreover, male tumor cells were injected into female mice, so high Uty gene expression and low Xist gene expression were used to differentiate between normal cells and tumor cells. Visualization was performed in either UMAP or DotPlot using log2 (counts per million) gene expression values. To identify DEgenes between T cells of Atg7+/+ versus T cells of Atg7Δ/Δ samples, we performed a subset option in Seurat to create a T-cell object from Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ samples and repeated the DE test. Upregulated genes in (Atg7+/+ or Atg7Δ/Δ) samples were used to perform hallmark and pathway enrichment. We performed gene set enrichment analysis48 (online web version) to find hallmark gene sets, gene ontology terms and KEGG pathway enrichment for DEgenes. We used R for all analyses and for visualization. The Seurat R toolkit was mainly used for analyses.

Western blotting.

Tumor samples were grounded in liquid nitrogen, lysed in Tris lysis buffer (50 mM Tris HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% NP40, 5 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol), separated on 12.5% SDS–PAGE gel and then transferred on PVDF membrane (Millipore). Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk for 1 h and probed overnight at 4 °C with antibodies against B2M (1:5,000 dilution, Ab7585, Abcam), FIP200 (1:1,000 dilution, 17250–1-AP, Proteintech) and β-actin (1:5,000 dilution, A1978, Sigma). Immunoreactive bands were detected using peroxidase-conjugated antibody (1:5,000 dilution, NA934 and NA931, GE Healthcare) and enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagents (NEL105001EA, Perkin Elmer) and were analyzed using the ChemiDoc XRS+ system (Biorad). Protein levels were quantified using the Image Lab v.6.0.1 software. Antibodies were validated with the use of positive and negative control following manufacturer’s protocol.

Histology.

Mouse tissues were fixed in 10% buffer formalin solution overnight and then transferred to 70% ethanol for paraffin-embedded sections. Tissue sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated and boiled for 45 min in 10 mM (pH 6) citrate buffer. Slides were blocked in 10% goat serum for 1 h and then incubated at 4 °C overnight with primary antibody against CD3 (1:100 dilution, Ab16669, Abcam), CD4 (1:1,000 dilution, Ab183685, Abcam), CD8 (1:100 dilution, 14–0808-82, Invitrogen), Foxp3 (1:75 dilution, 14–5773-80, Invitrogen), FIP200 (Proteintech, 17250–1-AP, 1:100 dilution) and P62 (Enzo, P9860, 1:1,000 dilution). The following day, tissue sections were incubated with biotin-conjugated secondary antibody for 15 min (Vector Laboratories), 3% hydrogen peroxide for 5 min, horseradish peroxidase streptavidin for 15 min (SA-5704, Vector Laboratories) and developed by 3,3-diaminobenzidine (Vector Laboratories) followed by hematoxylin staining (3536–16, Ricca). Sections were then dehydrated, mounted in Cytoseal 60 mounting medium (8310, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and analyzed using a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope. For quantification of IHC, at least 15 images were analyzed at ×60 magnification for each genotype.

Surveyor assay.

Liver genomic DNA was extracted following DNeasy blood and tissue kit instructions (QIAGEN, 69504). The gRNA sequence was amplified by PCR to confirm cuts or deletions (forward primer: 5′-AAGACTTTAACTCTGTGTTTCAGG-3′ and reverse primer: 5′-GAGAAATGCAGAGCTGCTGC-3′) using C1000 Touch thermal cycler (Biorad) and with the Phusion high-fidelity polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, F548). The amplicons were then used to perform the Surveyor Mutation Detection kits (IDT, 706020).

Statistics and reproducibility.

All statistical analyses were performed with Prism v.8 software using a two-sided Student’s t-test, unless specified otherwise. The sample size was chosen in advance on the basis of common practice of the described experiment and is mentioned for each experiment. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. Sample sizes were chosen on the basis of past experience with tumor growth assays in wild-type and Atg7-deficient host mice26. Each experiment was conducted with biological replicates (at least three mice per group) and repeated multiple times (at least two independent experiments). All attempts at replication were successful. Outlier data were automatically excluded based on Grubb’s test (Prism software). Outliers were removed from the serum cytokine and chemokine profiling (Fig. 1b). All experiments used mice that were randomly allocated into experimental groups. The investigators were not blinded during the experiments and outcome assessments. Blinding was not performed as the genotype and sex of the mice required identification for housing purposes.

Reporting Summary.

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

10X scRNA-seq data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession ID GSE154654. Whole-exome sequencing data generated in this study can be found in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession ID GSE155556. All other data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Extended Data

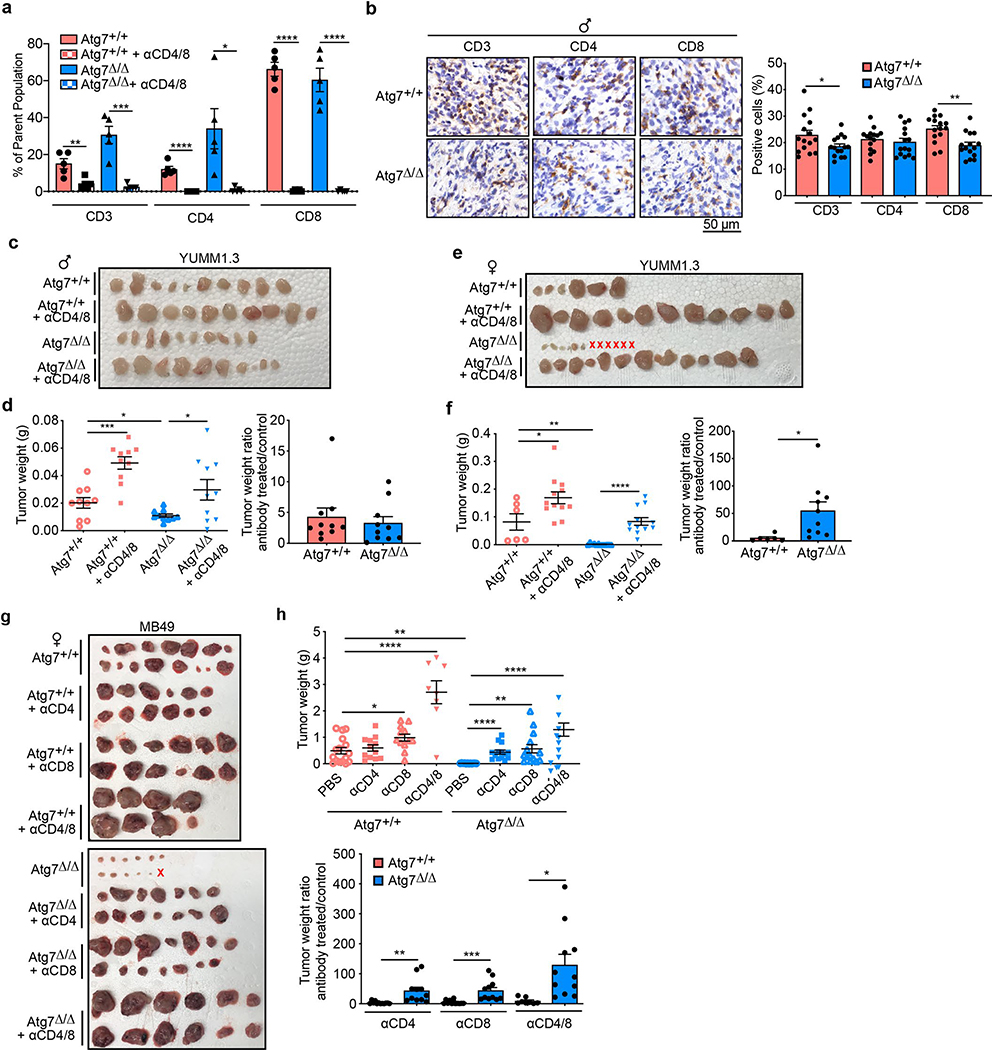

Extended Data Fig. 1 |. Loss of host autophagy does not decrease the growth of low TMB tumors in a T cell-dependent manner.

a, CD3+, CD4+, CD8+ T cells (percentage) in high TMB tumors (MB49) grown on female Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 5 mice each) hosts following αCD4/8, analyzed by flow cytometry. b, Representative IHC images and quantification of CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in YUMM1.3 tumors from male Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ hosts (n = 5 mice each). c, d, e, f, Comparison of YUMM1.3 tumor growth on male (c, d) Atg7+/+, Atg7+/+ + αCD4/8, Atg7Δ/Δ and Atg7Δ/Δ + αCD4/8 (n = 10 tumors each) and female (e, f) Atg7+/+(n = 6 tumors), Atg7+/+ + αCD4/8 (n = 12 tumors), Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 12 tumors) and Atg7Δ/Δ + αCD4/8 (n = 12 tumors). Tumor pictures (c, e), and tumor weight and ratio (antibody treated/control) (d, f) from the experimental endpoint. g, h, Comparison of MB49 tumor growth on female Atg7+/+(n = 14 tumors), Atg7+/+ + αCD4 (n = 12 tumors), Atg7+/+ + αCD8 (n = 12 tumors), Atg7+/+ + αCD4/8 (n = 8 tumors), Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 12 tumors), Atg7Δ/Δ + αCD4 (n = 14 tumors), Atg7Δ/Δ + αCD8 (n = 14 tumors) and Atg7Δ/Δ + αCD4/8 (n = 12 tumors). Tumor pictures (g), and tumor weight and ratio (antibody treated/control) (h) from the experimental endpoint. All data are mean +/− s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.001 using two-sided Student’s t-test. Source data available for a, b, d, f, h.

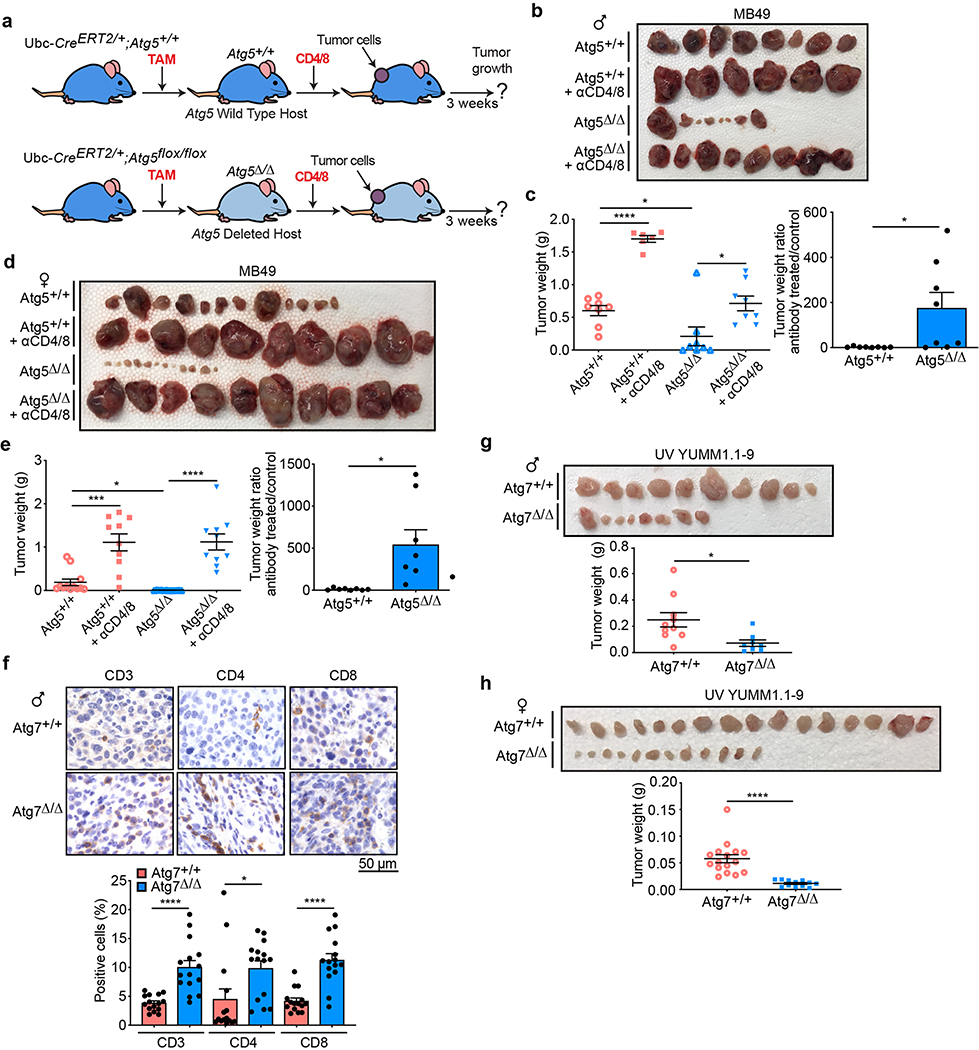

Extended Data Fig. 2 |. Loss of host autophagy through Atg5 deletion decreases tumor growth through a T cell-dependent mechanism.

a, experimental design to induce conditional whole-body Atg5 deletion (Atg5Δ/Δ), and wild-type (Atg5+/+) controls without and with T cell depletion. Ubc-CreERT2/+;Atg5+/+ and Ubc-CreERT2/+;Atg5flox/flox mice were injected with TAM to delete Atg5 and were then injected subcutaneously with tumor cells and intraperitoneally with αCD4/8. Tumor growth was monitored over three weeks. b, c, d, e, Comparison of MB49 tumor growth on male (b, c) Atg5+/+(n = 8 tumors), Atg5+/+ + αCD4/8 (n = 6 tumors), Atg5Δ/Δ (n = 8 tumors) and Atg5Δ/Δ + αCD4/8 (n = 8 tumors) and female (d, e) Atg5+/+(n = 12 tumors), Atg5+/+ + αCD4/8 (n = 10 tumors), Atg5Δ/Δ (n = 12 tumors) and Atg5Δ/Δ + αCD4/8 (n = 10 tumors). Tumor pictures (b, d), and tumor weight and ratio (antibody treated/control) (c, e) from the experimental endpoint. f, Representative IHC images and quantification of CD3+, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in MB49 tumors from male Atg5+/+ and Atg5Δ/Δ hosts (n = 5 mice each). g, h, Comparison of UV YUMM1.1–9 tumor growth on male (g) Atg7+/+ (n = 10 tumors) and Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 8 tumors) and female (h) Atg7+/+ (n = 16 tumors) and Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 12 tumors) hosts. Tumor pictures and tumor weight from the experimental endpoint. All data are mean +/− s.e.m. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 using two-sided Student’s t-test. Source data available for c, e, f, g, h.

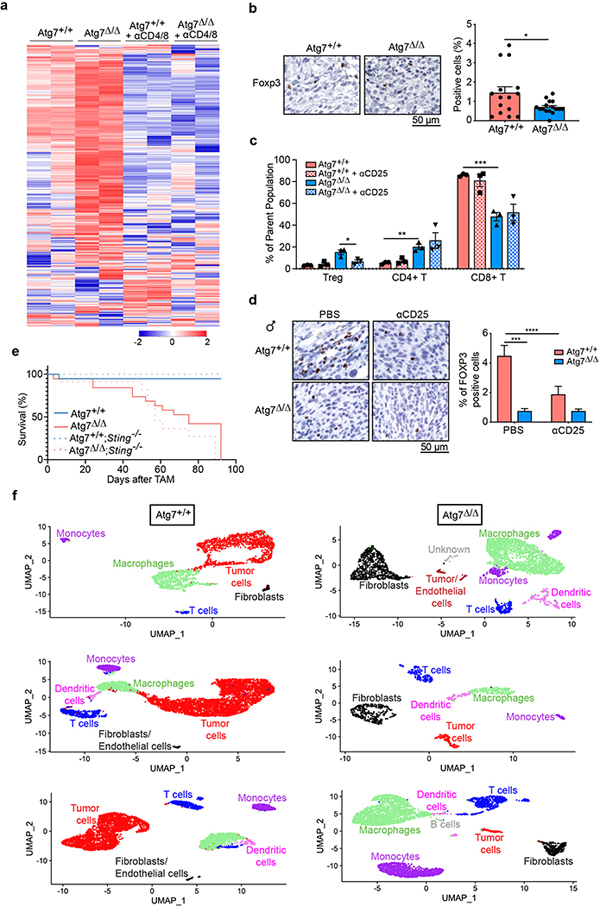

Extended Data Fig. 3 |. Loss of autophagy reduces Tregs and increases immune cell fraction.

a, Overall NanoString gene expression analysis (750 genes) from tumors on female Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ hosts with or without αCD4/8 (n = 2 tumors each). Red: high, blue: low expression level. b, Representative IHC images and quantification of FOXP3+ cells in MB49 tumors from female Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ hosts (n = 5 tumors each). c, FOXP3+ Treg cells, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (percentage) in high TMB tumors (MB49) grown on female (n = 3 tumors) Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ hosts following αCD25, analyzed by flow cytometry. d, Representative IHC images and quantification of FOXP3+ cells in MB49 tumors from female Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ hosts following αCD25 (n = 3 tumors each). e, Survival analysis of Atg7+/+ (n = 19 mice), Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 19 mice), Stinggt/gt;Atg7+/+ (n = 15 mice) and Stinggt/gt;Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 13 mice) mice. f, scRNA-seq UMAP projection of cell cluster from tumors from female Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ hosts (n = 3 tumors each). All data are mean +/− s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 using two-sided Student’s t-test. Source data available for b, c, d.

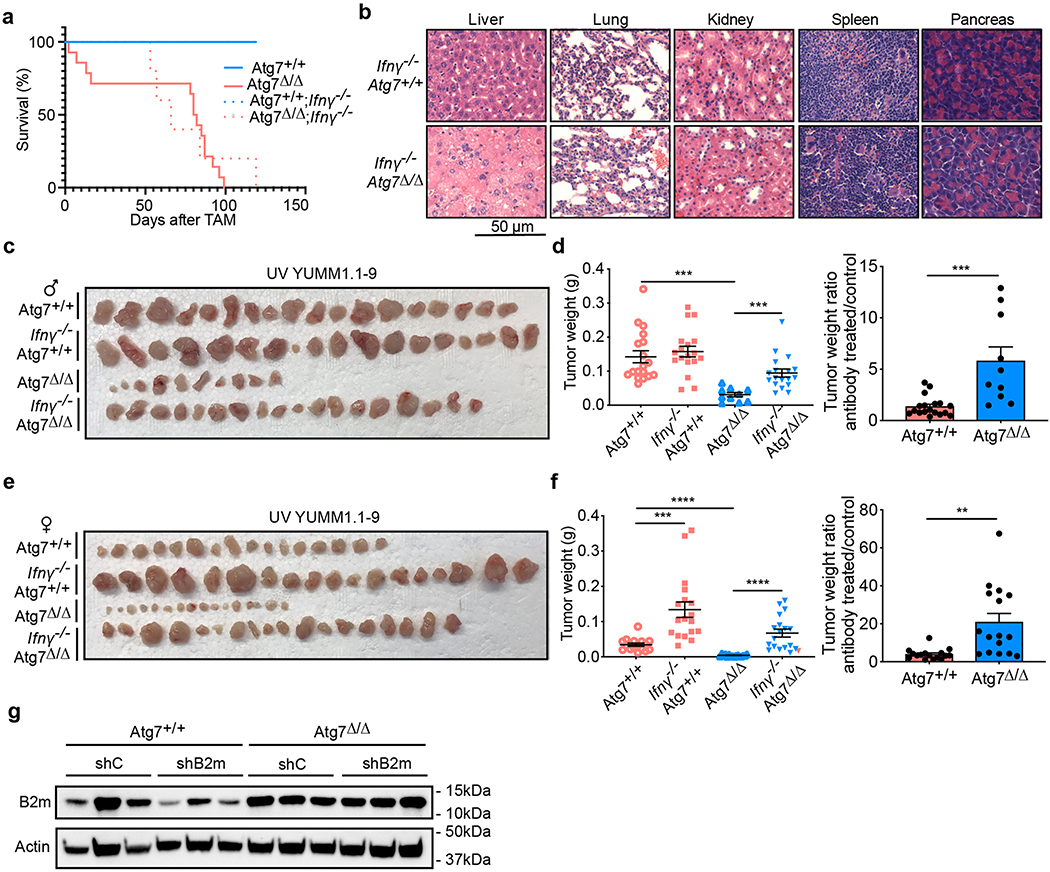

Extended Data Fig. 4 |. Loss of autophagy increases high TMB tumor growth in an IFNγ-dependent manner.

a, Survival analysis of Atg7+/+ (n = 16 mice), Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 14 mice), IFNγ−/−;Atg7+/+ (n = 6 mice) and IFNγ−/−;Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 5 mice) hosts. b, Representative H&e tissue staining from IFNγ−/−;Atg7+/+ and IFNγ−/−;Atg7Δ/Δ hosts. Images are representative of two independent experiments. c, d, e, f. Comparison of UV YUMM1.1–9 tumor growth on male (c, d) Atg7+/+ (n = 18 tumors), IFNγ−/−;Atg7+/+ (n = 18 tumors), Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 10 tumors), IFNγ−/−;Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 18 tumors) and female (e, f) Atg7+/+ (n = 16 tumors), IFNγ−/−;Atg7+/+ (n = 18 tumors), Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 16 tumors), IFNγ−/−;Atg7Δ/Δ (n = 18 tumors) hosts. Tumor pictures (c, e), and tumor weight and ratio (antibody treated/control) (d, f) from the experimental endpoint. g, Cropped Western blotting showing expression of B2m in MB49 shC and shB2m tumors from Atg7+/+ and Atg7Δ/Δ hosts (n = 3 tumors each) from one experiment. Actin was used a loading control. All data are mean +/− s.e.m. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 using two-sided Student’s t-test. Source data available for d, f.

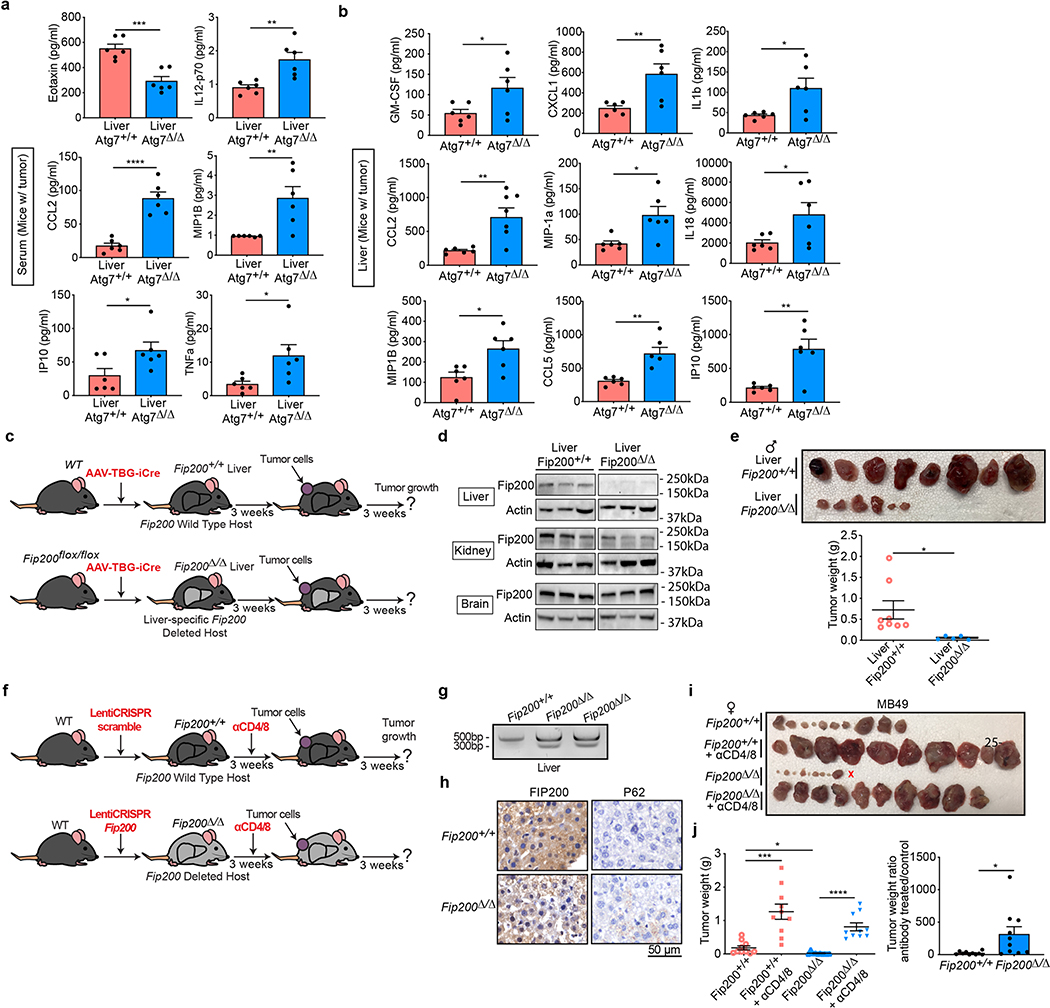

Extended Data Fig. 5 |. Loss of autophagy, not LC3-associated phagocytosis (LAP), decreases tumor growth through a T cell-dependent mechanism.

a, Serum and b, liver cytokine and chemokine profiling of female and male hosts bearing MB49 tumors with or without liver-specific deletion of Atg7 (n = 6 mice each), showing those with significant differences among 26. c, experimental design to induce liver-specific Fip200 deletion (liver Fip200Δ/Δ) and wild-type controls (liver Fip200+/+). Fip200flox/flox or C57BL/6J mice were injected with AAV-TBG-iCre and MB49 cells were then injected subcutaneously and tumor growth was monitored over three weeks. d, Cropped Western blotting showing expression of Fip200 in livers, kidneys and brains (n = 3 each) from one experiment. e, Comparison of MB49 tumor growth on male liver Fip200+/+(n = 8 tumors) and liver Fip200Δ/Δ (n = 6 tumors) hosts. f, experimental design to induce conditional Fip200 deletion (Fip200Δ/Δ) and wild-type (Fip200+/+) controls. C57BL/6J mice were injected with lentiCRISPR scramble or Fip200 to delete Fip200 and were then injected subcutaneously with tumor cells. Tumor growth was monitored over three weeks. g, Representative surveyor assay for Fip200 gRNA screening using liver gDNA from Fip200+/+ and Fip200Δ/Δ hosts (n = 10 mice each) from one experiment. h, Representative IHC images of FIP200+ and p62+ cells in liver from Fip200+/+ and Fip200Δ/Δ hosts (n = 10 mice each). i, j, Comparison of MB49 tumor growth on female Fip200+/+ and Fip200Δ/Δ hosts with or without CD4/8 depletion (n = 10 tumors each). Tumor pictures (i), and tumor weight and ratio (antibody treated/control) (j) from the experimental endpoint. Data are mean +/− s.e.m. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P < 0.0001 using two-sided Student’s t-test. Source data available for a, b, e, j.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants: R01CA193970 (to E.W.), R01CA163591 (to E.W. and J.D.R.), R01CA193970 (to J.M.M.), R01CA211066 (to J.L.G), R01CA243547 (to E.W., S.G. and E.C.L.) and P30CA072720 (Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey) and by the Krauss Foundation (to E.W. and E.C.L.). C.S.C. is supported in part by Stand Up to Cancer and National Science Foundation grant no. 1546101. L.P.P. and S.V.L. received support from a postdoctoral fellowship from the New Jersey Commission for Cancer Research (DHFS16PPC034 and DCHS19PPC009, respectively). Services, results and/or products in support of the research project were generated by funding from the Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey Comprehensive Genomics and Immune Monitoring Shared Resources supported, in part by NCI-CCSG P30CA072720-5920 and by the Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics (Genomics Core Facility).

Footnotes

Competing interests

E.W. is co-founder of Vescor Therapeutics and is a consultant for Novartis. S.G. has consulted for Roche, Merck, Novartis, Foundation Medicine and Foghorn Therapeutics. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Extended data is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s43018-020-00110-7.

Supplementary information is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s43018-020-00110-7.

Reprints and permissions information is available at www.nature.com/reprints.

References

- 1.Karsli-Uzunbas G et al. Autophagy is required for glucose homeostasis and lung tumor maintenance. Cancer Discov. 4, 914–927 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Komatsu M et al. Impairment of starvation-induced and constitutive autophagy in Atg7-deficient mice. J. Cell Biol. 169, 425–434 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuma A et al. The role of autophagy during the early neonatal starvation period. Nature 432, 1032–1036 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guo JY et al. Autophagy provides metabolic substrates to maintain energy charge and nucleotide pools in Ras-driven lung cancer cells. Genes Dev. 30, 1704–1717 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamada Y, Sekito T & Ohsumi Y Autophagy in yeast: a TOR-mediated response to nutrient starvation. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 279, 73–84 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM & Klionsky DJ Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature 451, 1069–1075 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimmelman AC & White E Autophagy and tumor metabolism. Cell Metab. 25, 1037–1043 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amaravadi R, Kimmelman AC & White E Recent insights into the function of autophagy in cancer. Genes Dev. 30, 1913–1930 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poillet-Perez L & White E Role of tumor and host autophagy in cancer metabolism. Genes Dev. 33, 610–619 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sousa CM et al. Pancreatic stellate cells support tumour metabolism through autophagic alanine secretion. Nature 536, 479–483 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang A et al. Autophagy sustains pancreatic cancer growth through both cell-autonomous and nonautonomous mechanisms. Cancer Discov. 8, 276–287 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poillet-Perez L et al. Autophagy maintains tumour growth through circulating arginine. Nature 563, 569–573 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Degenhardt K et al. Autophagy promotes tumor cell survival and restricts necrosis, inflammation, and tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 10, 51–64 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mathew R et al. Functional role of autophagy-mediated proteome remodeling in cell survival signaling and innate immunity. Mol. Cell 55, 916–930 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merkley SD, Chock CJ, Yang XO, Harris J, Castillo EF & Modulating T Cell responses via autophagy: the intrinsic influence controlling the function of both antigen-presenting cells and T cells. Front. Immunol. 9, 2914 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McFadden DG et al. Mutational landscape of EGFR-, MYC-, and Kras-driven genetically engineered mouse models of lung adenocarcinoma. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, E6409–E6417 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bignell GR et al. Signatures of mutation and selection in the cancer genome. Nature 463, 893–898 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Westcott PM et al. The mutational landscapes of genetic and chemical models of Kras-driven lung cancer. Nature 517, 489–492 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J et al. UV-induced somatic mutations elicit a functional T cell response in the YUMMER1.7 mouse melanoma model. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 30, 428–435 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei SC, Duffy CR & Allison JP Fundamental mechanisms of immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Cancer Discov. 8, 1069–1086 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo JY et al. Autophagy suppresses progression of K-Ras-induced lung tumors to oncocytomas and maintains lipid homeostasis. Genes Dev. 27, 1447–1461 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei H et al. Suppression of autophagy by FIP200 deletion inhibits mammary tumorigenesis. Genes Dev. 25, 1510–1527 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schumacher TN & Schreiber RD Neoantigens in cancer immunotherapy. Science 348, 69–74 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Panda A et al. Identifying a clinically applicable mutational burden threshold as a potential biomarker of response to immune checkpoint therapy in solid tumors. JCO Precis. Oncol. 10.1200/PO.17.00146 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang AS, Monken CE & Lattime EC Intratumoral vaccination with vaccinia-expressed tumor antigen and granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor overcomes immunological ignorance to tumor antigen. Cancer Res. 63, 6956–6961 (2003). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Poillet-Perez L et al. Autophagy maintains tumour growth through circulating arginine. Nature 563, 569–573 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chu H et al. Gene-microbiota interactions contribute to the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Science 352, 1116–1120 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wei J et al. Autophagy enforces functional integrity of regulatory T cells by coupling environmental cues and metabolic homeostasis. Nat. Immunol 17, 277–285 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sawant DV et al. Adaptive plasticity of IL-10(+) and IL-35(+) Treg cells cooperatively promotes tumor T cell exhaustion. Nat. Immunol 20, 724–735 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sliter DA et al. Parkin and PINK1 mitigate STING-induced inflammation. Nature 561, 258–262 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 31.Castro F, Cardoso AP, Goncalves RM, Serre K & Oliveira MJ Interferon-γ at the crossroads of tumor immune surveillance or evasion. Front. Immunol 9, 847 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamamoto K et al. Autophagy promotes immune evasion of pancreatic cancer by degrading MHC-I. Nature 581, 100–105 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cunha LD et al. LC3-associated phagocytosis in myeloid cells promotes tumor immune tolerance. Cell 175, 429–441 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee HK et al. In vivo requirement for Atg5 in antigen presentation by dendritic cells. Immunity 32, 227–239 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu X et al. Autophagy is essential for effector CD8(+) T cell survival and memory formation. Nat. Immunol. 15, 1152–1161 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DeVorkin L et al. Autophagy regulation of metabolism is required for CD8(+) T cell anti-tumor immunity. Cell Rep 27, 502–513 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu Y et al. STING-mediated inflammation in Kupffer cells contributes to progression of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J. Clin. Invest 129, 546–555 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Appleman LJ et al. Targeting autophagy and immunotherapy with hydroxychloroquine and interleukin 2 in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): a Cytokine Working Group study. J. Clin. Oncol 36, 106–106 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hara T et al. Suppression of basal autophagy in neural cells causes neurodegenerative disease in mice. Nature 441, 885–889 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gan B et al. Role of FIP200 in cardiac and liver development and its regulation of TNF-α and TSC-mTOR signaling pathways. J. Cell Biol. 175, 121–133 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meeth K, Wang JX, Micevic G, Damsky W & Bosenberg MW The YUMM lines: a series of congenic mouse melanoma cell lines with defined genetic alterations. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 29, 590–597 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Summerhayes IC & Franks LM Effects of donor age on neoplastic transformation of adult mouse bladder epithelium in vitro. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 62, 1017–1023 (1979). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McKenna A et al. The genome analysis toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 20, 1297–1303 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cibulskis K et al. Sensitive detection of somatic point mutations in impure and heterogeneous cancer samples. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 213–219 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McLaren W et al. The ensembl variant effect predictor. Genome Biol. 17, 122 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Koboldt DC et al. VarScan: variant detection in massively parallel sequencing of individual and pooled samples. Bioinformatics 25, 2283–2285 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Butler A, Hoffman P, Smibert P, Papalexi E & Satija R Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nat. Biotechnol 36, 411–420 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Subramanian A et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 15545–15550 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

10X scRNA-seq data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession ID GSE154654. Whole-exome sequencing data generated in this study can be found in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession ID GSE155556. All other data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Source data are provided with this paper.