Abstract

Placental mesenchymal dysplasia (PMD) is a rare condition characterised by placental enlargement, oedematous villi and multiple anechoic cysts. Hepatic mesenchymal hamartoma (HMH) is a benign proliferation of mesenchymal tissue, commonly seen in infants below the age of 2. We report the case of a 28 years old female who was noted to have a fetus with a well‐circumscribed cyst on the liver, suggestive of HMH and a large, thickened placenta, with multiple anechoic cysts, consistent with PMD during the third trimester. There were no other structural abnormalities and at 38 weeks she underwent an induction of labour with normal vaginal delivery of a live female infant. While the aetiology is poorly understood, the increased incidence of HMH with PMD and the morphological similarities of the changes seen in both the placenta and liver, suggests a possible common developmental mechanism. There are only 12 other cases of this concurrent pathology in the literature and only one of these had resulted in a term delivery, and ours is the second one to date.

Keywords: anechoic cysts, fetal liver cysts, hepatic mesenchymal hamartoma, placental mesenchymal dysplasia

A 28‐year‐old female, gravida 4 para 2, with two previous term spontaneous vaginal deliveries, and no prior history of any medical or surgical conditions, was referred to our tertiary centre for evaluation of a fetal cystic abdominal mass at the level of the cord insertion that was noted at 34 weeks’ gestation. She had an uneventful early pregnancy with a normal morphology scan at 19 weeks’ gestation. The morphology scan images were independently reviewed by a Maternal Fetal Medicine specialist to confirm that there was no prior evidence of this cystic mass that may have been missed.

A formal tertiary scan was performed at 36 weeks which confirmed a large well‐circumscribed, heterogenous, septated cyst in the right lobe of the fetal liver, measuring 4.0 cm × 3.0 cm × 4.0 cm (Figure 1, 2). The scan also revealed a large, thickened placenta, 17 cm in width, with multiple anechoic spaces, the largest which was 3.0 cm in diameter (Figure 3, 4). The fetus was otherwise normal with no evidence of hydrops, intra‐uterine growth restriction or polyhdramnios. The association of the fetal liver cyst with anechoic placental cysts raised the suspicion of a liver hamartoma in the fetus with associated placental mesenchymal dysplasia. She was monitored closely with weekly serial growth scans which demonstrated that the liver cyst remained stable in size and there was good fetal interval growth.

Figure 1.

Axial view of fetal abdomen at 34 weeks showing well‐circumscribed, multi‐sepatate nature of the liver cyst, measuring 4 cm × 3 cm × 4 cm in size.

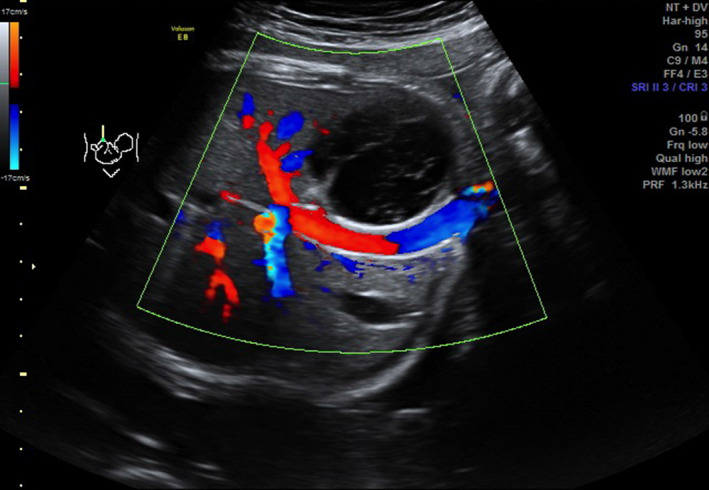

Figure 2.

Colour Doppler image of axial view of fetal abdomen at 34 weeks’ gestation, showing avascular nature of the liver lesion.

Figure 3.

Sagittal view of placenta at 34 weeks’ gestation showing thickened placenta with multiple anechoic spaces throughout, the largest measuring 3 cm in diameter.

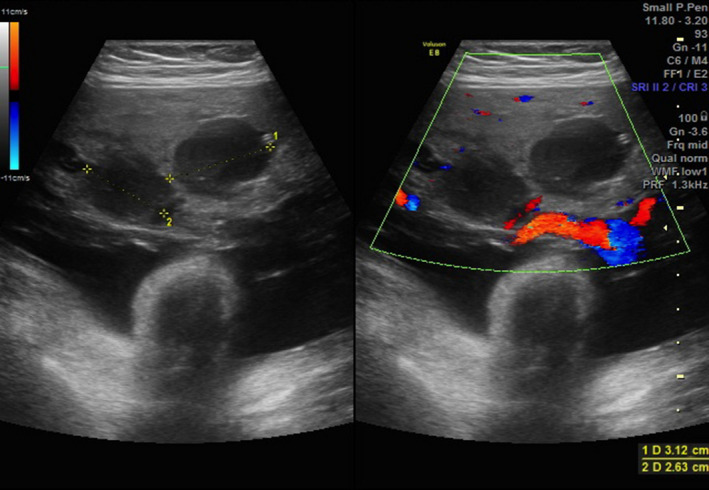

Figure 4.

Transverse view of the placenta with and without colour Doppler showing the large anechoic placental lesions.

At 38 weeks’ gestation she underwent an induction of labour with an uncomplicated normal vaginal delivery of a live female infant born in good condition. The birthweight was 2.7 kg and the infant was admitted to the special care nursery for observation. She was breastfeeding well and was discharged home day 2 postpartum.

The placental histopathology reported a markedly enlarged placenta, weighing 1.97 kg (>95th centile) with typical features of placental mesenchymal dysplasia.

Post‐natally, the infant has been monitored closely by paediatric surgeons and the liver harmartoma was noted to be stable in size. Liver function tests and tests of hepatic synthetic function were all normal. Serial measurements of alpha‐fetoprotein levels in the infant, which can be raised with some liver neoplasms, have also remained normal since birth. Currently, there is a plan to operate on the lesion at 1 year of life.

Placental mesenchymal dysplasia (PMD) is a rare condition characterised by sonographic features of a thickened and enlarged placenta with multiple hypoechoic, grape‐like cystic areas.1 The diagnosis can only be confirmed histopathologically as PMD can often be mistaken for gestational trophoblastic disease due to their similar sonographic features.1 Other fetal anatomical conditions can often co‐exist with PMD including Hepatic Mesenchymal Hamartomas (HMH), with up to a dozen cases reported in the literature.1

HMH is a rare, benign, proliferative lesion of mesenchymal tissue of the liver, with the majority being diagnosed in infants below the age of 2 years.2 The striking feature is the morphological similarity of the oedematous, myxoid changes seen in both the placenta and liver with these two conditions. While the aetiology is poorly understood, the increased incidence of HMH with PMD does suggest a possible common developmental mechanism.

Although it was not clearly noted in our case report, current data does imply that the placental changes precede the development of HMH. One possible theory suggested by Lennington et al.,3 is that the multiple thrombi present in the placental vasculature embolise to the fetal liver resulting in the development of HMH as a reactive process to the associated ischaemia.

Androgenetic/biparental mosaicism has also recently come to light as a possible cause for the synchronous development of PMD and HMH.4 The nature of the mutation and relative proportion of androgenetic cells present may explain the large spectrum of disease that exists and why these two conditions may occur together, but not always.

Owing to the rarity of these conditions, particularly in conjunction with each other, there is limited data on the antenatal and long term post‐natal outcomes for these fetuses. However, it does appear that the co‐occurrence of PMD and HMH is associated with worse outcomes than if these conditions were to occur individually and could potentially result in prematurity, hydrops, IUGR and fetal demise.2, 5

While there is no consensus on how to manage these cases antenatally, it can be agreed that heightened surveillance with serial growth scans and fetal wellbeing assessments, is required in the perinatal period to reduce fetal morbidity and mortality. There may also be a role for consideration of early delivery and ultrasound guided percutaneous decompression of the HMH if other concerning features such as rapid enlargement with associated mass effect, hydrops, or growth abnormalities are also present.6

In conclusion, we describe a case of a late diagnosis of PMD with HMH in which there was a good outcome for the fetus. There are only 12 other cases in the literature and only one of these had resulted in a term delivery, and ours is the second one to date. This may be a reflection of the poor prognosis or a publication bias and this requires further clarification.

References

- 1.Kinoshita T, Fukaya S, Yasuda Y, Itoh M. Placental mesenchymal dysplasia. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2007; 33(1): 83–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harris K, Carreon CK, Vohra N, Williamson A, Dolgin S, Rochelson B. Placental mesenchymal dysplasia with hepatic mesenchymal hamartoma: a case report and literature review. Fetal Pediatr Pathol 2013; 32(6): 448–53. doi: 10.3109/15513815.2013.835893. Epub 2013 Sep 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lennington WJ, Gray GF Jr, Page DL. Mesenchymal hamartoma of liver. A regional ischemic lesion of a sequestered lobe. Am J Dis Child 1993; 147(2): 193–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaiser‐Rogers KA, McFadden DE, Livasy CA, Dansereau J, Jiang R, Knops JF, et al. Androgenetic/biparental mosaicism causes placental mesenchymal dysplasia. J Med Genet 2006; 43(2): 187–92. Epub 2005 May 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nayeri U, West A, Grossetta Nardini H, Copel JA, Sfakianaki AK. Systematic review of sonographic findings of placental mesenchymal dysplasia and subsequent pregnancy outcomes. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2013; 41(4): 366–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruhland B, Schröer A, Gembruch U, Noack F, Weichert J. Prenatal imaging and postnatal pathologic work‐up in a case of fetal hepatic hamartoma and placental mesenchymal dysplasia. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2011; 38(3): 360–2. doi: 10.1002/uog.9005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]