Abstract

Background

National Ugly Mugs (NUM) is a UK-wide violence prevention and victim support charity that provides a mechanism for sex workers to share safety information and obtain support for harms that they may experience during the course of their work. Over the past several years, NUM has witnessed a decline in sex workers willing to access police as part of their recovery journeys after experiencing victimisation. In 2012, 28% of those reporting to NUM chose to engage with the legal system; in 2020, this was down to 7.7% amongst off-street independent workers. Statistics for 2021 indicate a continuation of this downward trend. Furthermore, anonymous consent to share information with police also declined from 95% in 2012 to 69% in 2020.

Methods

NUM conducted a survey of 88 sex working members in 2020. This information combined with our data on victimisation provides insights of the factors that deter sex workers from involving police as part of their justice-seeking efforts.

Results

Survey results reveal that sex workers feel alienated and untrusting of police and courts.

Conclusions

The implications of sex workers not sharing information about dangerous individuals with police and choosing not to participate in court processes signal significant flaws in our legal system regarding safe and inequitable access and pose dangers for all of us.

Keywords: Sex work, Stigma, Crime, Victims, Underreporting, Criminal justice system

Introduction

Around the world, sex workers experience extraordinarily high levels of victimisation. Concurrently, they face significant barriers to accessing justice as the result of widespread stigma with regard to their work and other aspects of their identities. Benoit et al. (2018) describe the variety of sources that create and recreate sex work stigma: law, regulation and policies; the media; the justice system; the healthcare system; the wider public; and sex workers themselves. The ways in which this stigma manifests with regard to the police vary in response to regulatory regimes in any given jurisdiction.

National Ugly Mugs (NUM) is a UK-wide charity which was founded in 2012 after 10 years of advocacy by community practitioners, police and researchers to the Home Office calling for a national approach to reporting and responding to harms against sex workers. NUM is the largest sex worker victim support organisation in the UK, and as of February 2021, it had well over 7000 members, with more than 6436 of these identifying as sex workers and more than 1000 members comprising those working as practitioners, frontline support services and within industry venues. NUM’s mission is simply to ‘end all forms of violence against sex workers’. They achieve this through core activities such as (1) the provision of safety information and warnings for harm prevention; (2) direct support to victims and survivors; (3) community education and learning exchanges by sex industry workers for practitioners and law enforcement to improve practice; and (4) systemic advocacy towards law and policy improvements, as a means to change the conditions that lead to the victimisation of sex workers and survival sex. NUM acknowledges sex workers as ‘experts by experience’ and ensures that they are fully embedded in operations and shapes their services, priorities and strategic direction.

As a core feature, NUM provides a UK-wide reporting and alerting service where sex workers, frontline services and police forces report harms against sex workers. NUM processes these reports and produces warnings that are disseminated to sex workers as alerts via SMS, email, their website and to off-line sex workers with the support of outreach organisations. These alerts serve to inform sex workers’ decisions about who they see as clients and who they wish to avoid in addition to where and how they work. Since inception in 2012, NUM has sent over 1.5 million alerts to sex workers to prevent violence and other harms. In 2020, reporting declined due to full and tiered COVID-19 lockdown measures; however, many sex workers had no choice but to continue working due to poverty and the lack of government support to ‘stay home and stay safe’. Despite this, NUM received 603 reports containing 723 accounts of harm to sex workers. Nationally, reports coalesced into three main categories: 41% (295 reports) were of physical violence including rape, attempted rape, sexual assault, and condom removal; 24% (171 reports) were fraud and robbery; and 23% (165 reports) were stalking and harassment; the balance was a range of other harms.

As a result of these high rates of victimisation and the discrimination and stigma sex workers face, NUM centralises their needs and advocates for their equitable access to crime prevention resources and fair treatment within and beyond the legal system. Every sex worker who reports to NUM is provided with enhanced support by a case work team of Independent Sexual Violence Advisors (ISVAs) and other trained professionals and sex industry experts, who provide sex worker–centred, trauma-informed support. With the consent of victims, anonymous intelligence is shared with local police forces in pursuit of dangerous individuals operating in wider communities. NUM is gravely concerned about the well-being of sex workers and the implications of their opting out of accessing the police following experiences of harm and, with their help, have come to understand this choice as a means to avoid further victimisation. In this paper, we suggest that the justice system is failing some of the most marginalised and victimised members of our communities. Sex workers already have limited access to justice via police and courts and also experience little societal protection within our communities. Structural inequities such as racism, poverty and discrimination based on sexual and gender identity, coupled with sex work stigma, victim-blaming and a range of other factors influence sex workers’ decisions about involving the state in their lives (Bowen, 2021). If the justice system is not a safe option for sex working survivors, then we must question who it is designed for.

The Socio-Legal Context

The following are not only non-exhaustive examples of regulation, but ones that demonstrate how differing socio-legal contexts contribute to stigma faced by sex workers (for further discussion, see Platt et al., 2018, which demonstrates the multitude of harms which exist within systems involving forms of criminalisation).

In countries with full criminalisation policies, such as the majority of the USA (excluding some locations in Nevada), the relationship between sex workers and the police is actively adversarial. The legitimisation of police power by the state and wider society allows them to carry out operations that target the activities and movements of sex workers, their clients and third parties, arresting and laying charges that typically lead to fines and jail time. In these contexts, sex workers are criminals, the fines are criminogenic, and the violence they experience could be dismissed as an occupational hazard at best, or an experience that they deserve at worst. This kind of hostile policy environment actively deters sex workers from accessing the justice system to report harms or to provide intelligence about dangerous individuals, nor would they obtain any support in improving their working conditions, addressing sex work stigma or improving safety. Sex workers who experience little social and police protection become a fair game to be exploited and harmed by anyone they come across, and they live their lives in fear. In some cases, the police may become active perpetrators of violence against sex workers — in South Africa, 54% of sex workers reported having experienced violence at work, and 55% of those named the police as perpetrators of that violence (NACOSA & SWEAT, 2013). This is not unique to South Africa as multiple incidents of sexual and physical violence by the police towards sex workers have been recorded in Russia, Uganda, the USA and India (Mac & Smith, 2018: 129–130; Benoit et al., 2018). The stigma which underpins full criminalisation legislation prevents sex workers from accessing justice or seeking remedies when they are wronged out of fear for their own safety. Sex workers fear police, and most avoid contact with them under fully criminalised regimes as they are a significant source of stigma and oppression.

Where the sex industry is legalised, in countries such as Germany and The Netherlands, some sex workers still face marginalisation perpetrated by the state and the police. Sex workers who are able to establish themselves as legitimate still undergo heavy regulation that may involve registration with an official organisation, regular health checks and mandatory counselling. The police, state health services and others maintain disproportionate regulatory power over sex workers under legalisation regimes. Those who cannot meet the criteria — often the most marginalised populations such as non-citizens, migrant workers or those engaging in sex work to meet immediate resource needs — remain criminalised and experience the same barriers to justice as workers under a fully criminalised policy environment (Mac & Smith, 2018).

In countries with partial criminalisation such as England and Wales where sex workers are subject to policies that displace them from public spaces and dictate how they can operate off-street. These include regions that enforce asymmetrical criminalisation, also known as the Nordic Model, such as Canada under the Protection of Communities and Exploited Persons Act (PCEPA) where sex workers experience violations of their Charter rights to equal treatment under the law, security of person and their rights to freedom of association and expression (Belak & Bennett, 2016). Similarly, in the Republic of Ireland, under Part 4 of the Criminal Law (Sexual Offences) Act 2017 where buying sex is criminalised, the relationship between sex workers and the police is poor and untrusting. In England and Wales, this trust is further hindered by differences in regulation across police forces and local councils. In Holbeck, Leeds, sex workers were permitted to meet their clients in a ‘managed area’ (Longman & Hatchard, 2016); however, the activities that they undertook must be conducted elsewhere; this was until the closure of the managed area in June 2021 (Basis, 2021). In Hull, 60 miles away, 1972 Sect. 222 orders were in effect, allowing for the arrest and prosecution of sex workers found ‘loitering’ or soliciting in a specified zone until the High Court order in May 2020 overturned this legislation (Embury-Dennis, 2018; Mutch, 2020). Here, a hard-targeting criminalisation of some of the most visible and impoverished sex workers signals for them and others in the population that they are unwanted and unprotected in their communities, irrespective of what is said about ending the feminisation of poverty and protecting the vulnerable. If the police officers that sex workers see are there to arrest them, there is little hope that they will access these vary officers for protection against victimisation.

Reducing stigma, ending the criminalisation of sex workers and ensuring that they are respectfully and meaningfully included in policymaking drive NUM’s regional and national systemic advocacy. In May 2020, NUM was approached by An Untold Story—Voices, a collective of women with lived experience of street sex work in Hull and their supporters, who, as a last resort launched a Judicial Review of Hull City Council’s s.222. As this policy has both historically and contemporarily jeopardised the safety and well-being of sex workers, NUM provided an expert witness statement to the High Court. Following the court’s review of s.222, it was discharged, and the High Court ordered that Hull City Council work with on-street sex workers, Humberside Constabulary, the Police and Crime Commissioner and NUM to develop a new strategy in compliance with s.149 of the Equality Act 2020. This was a positive result and took the courage of sex workers directly affected by this policy to come forward to the courts. This is reminiscent of the landmark case, Canada (AG) v Bedford 2013 SCC 72 Bedford v. Canada 2014, where the Supreme Court of Canada, in a unanimous ruling, repealed sections of the Canadian criminal code that violated the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, including Sect. 7, related to liberty and security of person (Bowen, 2015).

Uglymugs.ie, an organisation that helps Irish sex workers share information about dangers reports that since the enactment of the Nordic Model in March of 2017 which criminalises buying sex, violent crimes against sex workers increased 92%. Furthermore, those who dared to work together for safety were criminalised under brothel-keeping legislation (Independent.ie, 2019). Although police forces state that they are open to hearing about victimisation upon sex workers, policies contribute to increased sex work and stigmatisation in two ways. First, the enforcement of laws which limit sex workers’ abilities to control where and how they work can prevent them from working safely, such as brothel-keeping, as it is illegal in the UK under the Sexual Offences Act 1956 for sex workers to work from premises with others. The brothel-keeping law delimits sex workers’ standing in the community, as where they work and how they work is deemed criminal. This can also include the use of non-carceral but still punitive measures such as cautions and fines, which are criminogenic because those who receive fines may sex work with others in premises to pay these fines; all the while, selling sex itself is not illegal throughout the UK. To demand a share of sex workers's earnings through fines, a population of women and others that many people view as vulnerable is highly problematic. Furthermore, those paying state fines through sex work instead of feeding their children or paying rent means that sex workers must work more to make up for losses in income. Ironically, through fines sex workers pay the salaries of the very courts and police who they benefit little from. Ultimately, these strategies are cyclical in ways reminiscent of the Ouroboros, hypocritical in that labour and money are extracted by the state from poor and working class sex workers who are mostly women, thus increasing their desperation, poverty and reliance on sex work for income. Secondly, the selective enforcement of punitive and criminogenic policies leads to fear and instability in the lives of sex workers. Sex workers may want to report harms against them; however, the police response that they may receive is unpredictable. This is precisely the context in which NUM works to bridge relations between sex workers, police and public services offered by the state. Sex workers experience stigma in this context of partial and asymmetrical criminalisation, and although they may benefit from some police and social protection, these are not entitlements and must be carefully negotiated. Sex workers are exposed or ‘outed’ to the state and are put at risk of further enforcement through other policies that may subject them to child apprehensions, benefits sanctions, challenges in obtaining or maintaining mainstream employment, evictions, threats to their status as students, deportation and more (Bowen, 2021; Mac & Smith, 2018).

Under all of these legal systems, the power imbalance between the police, who are imbued with a socially legitimate authority by the state, and sex workers, who are systematically disempowered, creates the ideal conditions for stigma to flourish. Stigma, regardless of the form it takes, serves to reinforce legitimised dominant interests and hegemonic power at the expense of the most marginalised and disadvantaged groups (Link & Phelan, 2001). In sex work, the intersections of power and legitimacy, the politics of respectability, stigma and social exclusion are made clear: the type of work a person engages in and how they undertake it, their gender, race and ethnicity, migration status and their physical abilities — to name but a few — are all embedded in the concept of the ‘Whorearchy’, which combines levels of client contact, police engagement and wider social structures to stratify the sex industry (Bosch, 2016; Bowen, 2021; Sciortino, 2016). Street-based sex workers in particular, a group often comprising individuals with the least social power, report high levels of social stigma and poor experiences with the police (Klambauer, 2019). The stigma that sex workers face cannot be extricated from broader social structures within which the police not only exist but are also charged with exercising state-sanctioned power (Klambauer, 2017). While the public in England and Wales look to the police to protect and serve, by preventing crime, improving community safety and responding to incidents in a competent and compassionate manner (BMG, 2019), sex workers rarely receive the same treatment (Klambauer, 2017, 2019). For sex workers, the police are not always a source of protection.

Working with the Police Forces

Since the founding of NUM, the organisation has worked with the consent of victims, to provide anonymous intelligence to police and information to the Serious Crime Analysis Section (SCAS). SCAS, through its analyses, works to identify serious crimes, serial killers and serial rapists by uncovering patterns and indicators. NUM sees their regular contributions to intelligence in this regard as essential to crime prevention efforts. SCAS is part of the National Crime Agency and was formed following the review of the Yorkshire Ripper Enquiry in a context where sex workers were treated as unworthy, dispensable and even blamed for their predicaments, resulting in the dismissal of their experiences of violence and impunity for offenders. This was evident in the responses of the police, politicians and media at the time, with Superintendent Jim Hobson stating that:

He [Sutcliffe] has made it clear that he hates prostitutes. Many people do. We, as a police force, will continue to arrest prostitutes. But the Ripper is now killing innocent girls. (Hobson, 1979, cited in Smith, 1992).

The Attorney General, Sir Michael Havers, also drew a divide between sex workers and society as a whole, reinforcing exclusionary and stigmatising attitudes towards sex workers within the justice system noting that of Sutcliffe’s victims ‘Some were prostitutes, but perhaps the saddest part of the case is that some were not’ (Havers, 1979, cited in Bland, 1992). The passage of time and opportunities for enlightenment about the plight of sex workers has not entirely eliminated sentiments like these about the value and placement of sex workers in our communities. It is NUM’s position that these attitudes are manifest in the legislation and policies that affect the lives of sex working victims and survivors, and are evident by the treatment they experience when they chose to pursue offenders through the legal system, in the messages sent by some residents’ groups who advocate for the displacement of sex workers, and through some forms of media that make money through the sensationalisation and vilification of sex workers in headlines and plots.

Since the advent of our case work team in 2017, to fill gaps created by the dismantling of specialist frontline services for sex workers and the preference of many off-street and online workers for judgement-free digital support services, NUM forges relationships with Special Points of Contact (SPOCs) in several forces to open dialogue, more fully communicate the complexities of sex work, reduce stigma and improve sex workers’ access to quality police responses. Some police forces also use NUM’s networks to share reports that warn sex workers about dangerous individuals, a feature of NUM’s work which increased by 35% in 2019. Sex workers who report harm to NUM have the choice to consent to providing anonymous or fully detailed reports to police. If they choose to engage law enforcement to pursue those who perpetrate violence against them, NUM will assist them in this endeavour by identifying and contacting the most appropriate officers and supporting sex workers to navigate the legal system from report to court. NUM has not yet been successful in establishing this kind of victim support pathway amongst all 43 UK police forces, due to the diversity of approaches to sex work and differing interests in working with a national charity such as NUM. The charity views this process mapping as vital to assisting sex workers who seek police protection but desire enhanced support to do so safely.

NUM has seen a notable decrease in the number of sex workers willing to access police to seek justice. Full consent in this respect has fallen amongst off-street independent sex workers from 28% in 2012 to 7.7% in 2020. This downward trend appears to be continuing. Reasons for this may be quite obvious and include the fear of criminalisation, stigma and police operations such as raids and uninvited ‘welfare visits’ where police attend the premises of off-street and online posing as clients. Over the past 9 years, NUM and other sex worker support organisations such as the English Collective of Prostitutes (ECP) bore witness and work to combat the secondary and tertiary impacts of sex workers being known to the state, such as evictions from premises where they live and work, extortion, exploitation and even ‘crimmigration’ and deportation. Sex workers also experience social rejection from their neighbours and communities. Furthermore, the desire for privacy and the ability to offer discreet services to clients, which would place sex workers in an elevated position within the whorearchy, may cause people to opt out of interacting with police. Workers of colour; migrants; those who belong to sexual and gender minority communities; parents; students and those who live dual lives, through concurrent involvement in sex work and square work (Bowen, 2021); and those who have chemical dependencies, in NUM’s experience, avoid contact with police and state services under the UK’s current regulatory framework. The need to consider the intersections between sex work stigma and other forms of oppression and marginalisation is clear here and is considered by workers within the results of NUM’s survey.

Sex workers who access NUM case workers are increasingly choosing remedies for harm from outside of the legal system to avoid further victimisation. NUM support services are grounded in the ‘Code of Practice for Victims of Crime in England and Wales’ (2020) which identifies 12 enhanced rights and entitlements for victims. NUM’s case work team aims to support sex workers in their justice-seeking efforts and to feel safer, better informed and more able to cope and recover. This involves linking workers with sex worker–friendly materials and services within our networks of practitioners and sex worker–led organisations to avoid further trauma and the long-lasting impacts of stigma and social exclusion on their mental health and future opportunities.

In order to influence policing policy, NUM contributed to the previous and the current 2019 version of the ‘NPCC National Policing Sex Work and Prostitution Guidance’ that was created to erect some uniformity around police engagement with sex workers which takes into account the nuances of sex work in police responses and ends a blanket criminalisation of sex workers (National Police Chiefs’ Council, 2019). Through the participation in co-creating and utilising this guidance as part of community education efforts with police, NUM aims for the police and courts to become more accessible to the sex workers who want to benefit from these public services. Many sex workers, particularly sex workers of colour, report to NUM that they neither experience nor perceive safe access to police protections; thus, the relationship must be mediated and witnessed until public services are designed inclusive of the interests of sex workers. NUM exists because of this breakdown in the system. To this end, NUM facilitates learning exchanges developed by sex workers for police forces that involve pre- and post-evaluations to measure knowledge, sensationalisation and recommendations for changes in approach. A major finding from NUM’s pre-evaluation data from these exchanges is that 86% of the 152 officers surveyed in 2019 had not heard of the NPCC Guidance. This highlights the lack of awareness about how the NPCC expect sex workers to be treated by police in the UK, and this is clear in police responses towards sex workers. One NUM member remarked: ‘As a sex worker, the idea of reporting to the police feels like a roulette. You have no idea what is going to happen to you’. Of the 14% of officers who were aware of the guidelines, they identified the need to build relationships with sex workers and recognised that criminalisation erodes trust.

Due to negative experiences with police and unfavourable and sensationalised depictions of sex work(ers) in mainstream media, they may lack belief in a just world (BJW) (Lerner, 1980). Sex workers are not criminals nor are they wholly victims, yet they are treated as if they are miscreants and undesirables, and this has a chilling effect on reporting incidents to the police. In order to learn more about the factors that influence reporting to police, NUM asked sex workers to reflect upon why there was declining interest in involving police and courts after experiencing violence.

Methods

NUM regularly hears from its membership through short surveys and focus groups that are promoted on social media and on their website, and kept behind a membership wall, requiring an approved login to access. Additionally, direct interaction with sex workers and insights derived from qualitative and quantitative data analysis of victim reports contribute to NUM’s ways of knowing and understanding violence against sex workers. The data presented in this article was gathered using an online survey, distributed to members of NUM through the charity’s social media channels and members’ platform online over one weekend, from 21 to 25 February 2020. During that time, NUM heard from (N = 88) active sex workers from across the UK who shared with us their barriers to reporting to the police and their insights about policing and why they choose to avoid the state. Although the total number of sex workers participating in the survey represents just over 1% of NUM’s current membership, the findings below confirm significant issues that need to be addressed to repair relationships between sex workers and police. Pseudonyms are associated with quotes to protect the confidentiality of survey respondents.

Findings

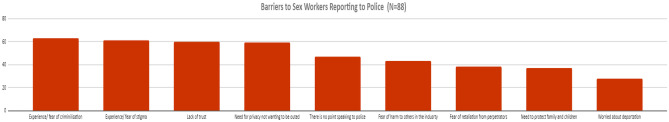

As illustrated in Fig. 1, sex workers surveyed listed several issues that prevent them from accessing police. Unsurprisingly, ‘experiences or fear of criminalisation’ was indicated by 72% of sex workers and was the most common barrier indicated between them and the police. Three other reasons for avoiding police were identified with similar frequency: ‘experiences or fear of stigmatisation’ (69%), the ‘lack of trust in police’ (68%) and the ‘need for privacy; not wanting to be outed’ (67%). These issues are very concerning as many sex workers have had previous personal experience reporting to the police and stated that as a result, they would not do so again in the future. Suzanne remarked ‘I would never go to the police again as I have reported before and received the response of being told it is my fault for selling myself’. Although some sex workers did know and understand their rights, this did not often serve as motivation to report. Much like the sex workers in Klambauer’s (2017) study, sex workers responding to this survey showed a great deal of stigma consciousness; an awareness of the stigma they face within society more broadly which shapes their interactions with the police as agents of the state. Molly made similar points, saying that ‘I don’t trust my local or county police force and will never again humiliate myself by going to the police should a crime take place’.

Fig. 1.

Barriers to sex workers reporting to police (N = 88)

The lack of trust in the police in general or specifically related to their capacity to deal with cases regarding violence against sex workers appropriately was frequently cited as another reason for choosing not to engage with them. Some respondents even highlighted their distrust of police outside of sex work, suggesting that incidents reported by non-sex workers are not dealt with adequately, so the added stigma of sex working would only serve to increase potential risks for the individual reporting. Many sex workers have experienced being outed (Donato, 2019), and so there is no surprise that this fear is amongst the most frequent. As Laura recognised that this fear does not necessarily stem from a belief that the police act with malicious intentions towards sex workers, but that does not prevent or mitigate the risks of them being outed: ‘For myself, why take the risk of any data coming in the police’s hands? Even with the best intentions people make mistakes, and I don’t want the police to know that I do SW [sex work] at all—I don’t trust them with that information’. This is detrimental to their lives and relationships both inside and outside of sex industries, as well as beyond them (Bowen, 2021). As Bella described, ‘fear of being outed/known as a sex worker [prevents me from accessing police]. [I am] Worried about future and disclosing my details, as I want another life, normal life, after I stop escorting.’ Bella demonstrates the ‘stickiness’ of sex work stigma and how being ‘marked’ as disreputable (Bruckert, 2012) will have long-lasting consequences even after transition from sex work.

Several respondents to the survey noted disillusionment as just over half (53%) stated that there would be no point in reporting to police. Many NUM members simply had little or no faith that the police would be able or willing to help them. Some mentioned that their previous encounters with police had been inconsistent in terms of attitude and knowledge about their situations, with multiple police officers within the same force having vastly different understanding of police practice or sex work issues. Deborah stated ‘There is very little consistency even from within the same police force.’ This once again supports Klambauer’s (2017) findings, within which many sex workers recognise the existence or first-hand experience of ‘good cops’, who treat sex workers with respect, dignity and understanding, and prioritise their safety; however, the inconsistencies between both within and between different forces create a ‘policing roulette’, leaving sex workers not knowing how they will be treated by any given officer. Eva described her own experiences of this disparity in support within her local constabulary:

I have had to contact the police on three separate occasions regarding nasty clients in my 10 years of sex work. The first time the police were brilliant, and the man got three years in jail for assault. The second time the police informed me that ‘what did I expect in my line of work’ when I was again assaulted. Finally, the third time I was informed that ‘it wasn’t rape if he didn’t pay me so what did I expect them to do’, when I was robbed after service. They weren’t interested in the robbery side of the crime only that I was a sex worker who hadn’t been paid. These were very varied experiences with three different police forces...and as such I don’t report anymore as 1:3 times there was a positive outcome i.e. a conviction for a crime. The second time my savage beating was even caught on hotel CCTV in the corridors and police refused to pursue the case because I was a sex worker.

Almost half of respondents (49%) indicated ‘fear of harm to others in the industry’ as a barrier to accessing the police. For many respondents, reporting rape or sexual assault to the police would involve disclosing locations of work, ways of working and other trade secrets that could result in raids or the closures of premises and increased targeting by police. This would run the risk of affecting not only the survivor’s income but also that of any other sex workers in the premises or the area. Frankie remarked, ‘For women attacked while working in premises they make a calculation about whether it is worth revealing the location of the place because almost inevitably it will be closed down.’ This barrier to reporting, whether it is a lived experience or a perception of police practices, creates a significant vulnerability, which means that perpetrators can repeatedly target sex workers at a venue or area with impunity. Additionally, 43% of sex workers surveyed did not access police after being harmed because of a ‘fear of retaliation from perpetrators.’ This indicates that there needs to be communication between sex workers and police after reporting harm, and updates about the perpetrator must be shared, a right noted in the ‘Code of Practice for Victims of Crime in England and Wales’. This fear of retaliation is exacerbated by the prohibition of brothel-keeping, which prevents workers from working together for safety. Megan explains:

I didn’t report my assault for months for many reasons, but partly because I wanted to eliminate the possibility that the perpetrator (who has been to my home) would be able to find me, as I live alone and work from home alone.

Legal sanctions against sex workers operating in premises together for safety are an occupational health and safety strategy that non-sex workers can enjoy. Jess points out this hypocrisy in her comments directed at police officers:

You should listen to us and believe us and not victim blame us. Look how you go out in pairs and much more, like as much as six or ten police on one offender, as it’s considered to be “dangerous” to be out on your own, so why can’t we do the same? Everybody should feel safe at work, so why not us?

Sex workers are also painfully aware of the fact that rape is not vigorously pursued. The recent HM Government ‘End-to-End Rape Review Report on Findings and Actions’ documents that despite the increase in the reporting of rape, there was a 3% conviction rate for adult rape offences amongst adults in 2019/2020, and notes several barriers to establishing credibility (HM, 2021). Since the onus is placed on victims and survivors to prove their innocence, credibility, and adherence to ideal victimhood, this means that there is little hope for sex working victims to be treated as legitimate witnesses to their own abuses in a court of law. Natasha reinforces this point, ‘If police in general do not take rape cases seriously, there’s no chance I will be believed, or that they’ll take rape or violence reports with me being a sex worker seriously either.’ Furthermore, Dean noted that sometimes the police were the perpetrators of violence against sex workers: ‘Fear of having the police turn up only to find they’re a customer, ex customer or ugly mug [prevents me from accessing them].’

Reporting to police puts sex workers’ personal lives and relations with family in jeopardy when insensitive policing practices, such as showing up at sex worker’s home address without pre-arranging to do so, and in uniform, outs sex workers in their communities. This has unfortunately happened to NUM members in the past. Furthermore, being a parent or guardian is an obstacle to reporting violence to police because victims and survivors run the risk of being reported to social services. Harmful and inaccurate stereotypes about sex workers being bad parents, that stem from earlier sentiments about their unworthiness, mean that the children of sex workers may be apprehended under the auspices of ‘safeguarding’. As a result of this, 42% of those surveyed stated that the ‘need to protect family and children’ from the state is a barrier to their accessing law enforcement. Dana stated, ‘I would worry about being flagged to social services that I worked [as a sex worker] and impacting on kids.’

While the previous examples are concerned with barriers faced by sex workers from all backgrounds, those who experience additional marginalisation navigate intersecting structural barriers when reporting harms against them to police. For example, Sofia states, ‘A lot of people do sex work because they are already marginalised and have fears of police already, let alone how that intersects with them doing sex work.’ Almost one-third (32%) of those surveyed stated that they do not contact police after being harmed due to their status as migrant workers and feeling ‘worried about deportation’. Sex workers base this fear on vicarious experiences, when they hear of or know other sex workers who have been deported after contact with police. The English Collective of Prostitutes (ECP) regularly document victimisation and deportation of migrant sex workers and shares this information with sex working communities. The ECP highlighted some of these cases in their 2020 report entitled ‘Sex workers are getting screwed by Brexit’ (ECP, 2020). NUM members from EU member states are growing increasingly concerned about the potential impacts of Brexit on their legal status and treatment while living in the UK. Claudine stated, ‘After Brexit I guess I would be more scared of going to the police.’ The same sentiment was echoed by Alicja:

With Brexit, xenophobia has been given a more emboldened speaking platform. The fears of deportation increase in this environment. Interacting with police could lead to it and currently even the Windrush scandal happened so what confidence does a sex worker have that they will be left alone or treated fairly.

These experiences of ‘crimmigration’, instances where criminal law and immigration intersect to the detriment of non-citizens, are not unique amongst UK sex workers. Butterfly, an Asian and Migrant sex worker support organisation in Toronto, regularly researches and documents instances of racism and discrimination faced by migrant sex workers due to conflation of an anti-trafficking agenda with migrancy in sex work (Lam, 2018).

Some respondents had a strong understanding of their rights as sex workers in the UK, but many who were new to the country did not feel as though they had adequate knowledge about the process of accessing police, reporting a crime, achieving justice or negotiating for legitimacy within the legal system. Simone explains, ‘It’s often not clear how the process of reporting will be, especially for people who didn’t grow up in the UK or haven’t been here for long’. Once again, the divide between sex workers who are UK citizens and those who are not is evident. Both documented and undocumented migrants may fear deportation, as discussed above, but additional barriers may also exist, such as with knowledge of the law or legal system, and the ability to bargain for a voice within it.

Sex workers of colour also highlighted the issue of systemic racism within the police that lead to them feeling stigmatised for both ethnicity and their sex work. Tammy remarked:

The police see us as dirty. They don’t believe we can be raped... I would never report violence to them because in the past they have never believed me, because I am not white. I tried to report rape, stalking, violence and they told me I asked for it and tried to convince me my abuser was not really hurting me. Because they don’t think women of colour have a humanity, they don’t see us as people who can be abused. Police are evil.

As NUM is a service to sex workers like Tammy, it aims to continue to meaningfully involve sex workers of colour (SWOC) as part of the staff team and in specific opportunities to hear from this underrepresented population in contouring services, in community education for police and public services, as well as in issue advocacy. The experiences of these sex workers and others inform NUM's relationships with state actors and its strategic direction. The inhumane treatment that Tammy lives to is tied to historical issues such as colonialism, the trans-Atlantic slave trade and contemporary manifestations of white supremacy, illuminated through the Black Lives Matter movement and made apparent in the UK’s Windrush Scandal. The intersections of race and sex work exacerbate the potential for violence including from state agents and the police (FemmeDaemonium, 2021).

For some of the gay men who responded to the survey, their sex work and drug activity led to a fear of reporting to police. Rod noted, ‘Gay sex workers [are] afraid to speak to police in case a sex worker being on or supplying substances (or assumed to do so) becomes the focus of the interaction.’ Using drugs or the threat of being labelled and criminalised as a dealer is an obstacle to sex workers interacting with police and may also pose challenges to gathering information and evidence; however, this ought not to mean that violence against those who use substances can be condoned.

There are also concerns amongst many sex workers about legislation related to sex work, particularly with regards to the fear that some high-profile MPs want to implement the Nordic Model and criminalise buying sex, a fear echoed amongst the sex workers quoted in Rosa (2021). As has been seen in jurisdictions like the Republic of Ireland and Canada, these kinds of policies reduce sex workers’ access to police. Some NUM members have stated that if such a policy comes into being in the UK, they will not contact police. Sarah stated, ‘fear of the Nordic model being implemented will keep me quiet.’ In particular, the Radical Feminist agenda behind the Nordic Model, and the defining of sex work as inherently violent and abusive, is seen as a barrier which prevents sex workers from defining their experiences in ways that they choose. Natalia noted that, ‘Sex Worker Exclusionary Radical feminists are pushing the erasure of sex worker voices, as defining sex work as rape, leaving no space to even define an attack in contrast to a respectful client’.

Ultimately, when sex workers see that people who violate non-sex working people get away with the crimes they commit, they do not expect better treatment for themselves. Kate drew comparisons between her experience reporting to the police in a non-sex working capacity and her experiences as a sex worker:

My only experiences with the police where I have been assaulted and experienced an armed robbery (not during sex work) were pointless and they never charged the men, even with proof and them identified. This lack of justice makes me reluctant to take the risk reporting something that happens during sex work, as nothing positive will happen and I put myself in a position where I could lose my residence… Recently I’ve been assaulted and robbed. I reported them on ClientEye and other groups, but I will not take police action.

Cynthia also illustrates this point, ‘Rapists don’t go to jail even when they victimize women whom the community feels moved to protect—there would be no point in pressing charges against mine.’

Cynthia’s remarks indicate that not only is it necessary to work harder to reduce sexual violence, but that some sex workers make comparisons between them and non-sex workers and have come to expect worse treatment and less protection. Like many of the other sex workers in this study, Cynthia demonstrates her stigma consciousness, separating herself from the ‘normals’ as someone socially deemed to be even less worthy of justice.

Discussion: a Case for Decriminalisation

Will decriminalisation bring about a legal system that protects people who fall outside of the ‘ideal victim’ archetype? Can we co-create a system in which marginalised victims benefit most? Based on 9 years of service to sex working victims and partnerships with some police forces, we answer ‘yes’ to both of these questions. Stigma and discrimination lies at the core of the exclusions that sex workers experience, and it is by overcoming this that we create systems of inclusion and equity. Platt et al. (2018) not only provide insight into the devastating effects that sex work stigma, but also provide the opportunities presented by a decriminalisation model for resisting that stigma. While decriminalisation is not without its flaws, it is a necessary pre-condition for sex work stigma to be reduced and to allow sex workers to become more included as members of society (Weitzer, 2018; Mac & Smith, 2018; Platt et al., 2018; Easterbrook-Smith, 2021; Armstrong & Fraser, 2020). Decriminalisation is, as Alice discusses, a first step towards safer interactions between police and sex workers:

Even under decriminalisation, I would need to see evidence of them being trustworthy and having mass training on how to deal with us before I ever considered going to them for anything, and even then I am not so sure.

Sex workers are deserving of all the protections our society offers. We believe the barriers that they have highlighted here are aspects of the relationships between sex workers, the state and society that we can vastly improve, such as reducing criminalisation, stigma and impediments to police protection. We support sex workers’ rights to choose what intervention they invite into their lives and, in growing numbers, they are prioritising self-preservation over state involvement. Consent to anonymously share intelligence with police from direct reports by sex workers has declined from 95% in 2012 to 69% in 2020. This means that 31% of reports that NUM receives are only shared with sex working communities and not with police or intelligence agencies for all of the reasons noted herein. By disclosing this, NUM does not mean to suggest that sex workers who feel let down by the system ought to risk their personal security to interact with police and the state. Conversely, NUM argues that police and public services must be made safer and worth accessing for marginalised populations, who are targeted by predators precisely because of their lack of equitable access to protection and justice. If national statistics on criminality, crime survey data and other analyses exclude the experiences of sex workers, they will provide an incomplete and inaccurate representation of the risks we all face with respect to community safety and offending.

Since most sex workers participate in off-street and online sex industries and have a need for discretion and anonymity while working, NUM values their decisions as survivors to opt out of engagement with traditional law enforcement, a practice noted in Jones (2020). It is vital that sex worker–serving organisations respect sex workers’ rights as victims and survivors to dictate the course of their coping and recovery. NUM has shared trends about reporting preferences with police throughout its presentations and interactions with forces, as well as through work to eradicate these barriers so that sex workers may access justice through their most desired means without the fear of stigma, retaliation or re-traumatisation. NUM will continue to lead community-based research with sex workers to improve victim supports within both NUM and in the sector more broadly. NUM will re-double advocacy efforts to advise policy-makers concerned with violence against women and girls (VAWG) and gender-based violence (GBV), as well as legal system professionals about how stigma and discrimination, partial and asymmetrical criminalisation, and mistrust and fear of the police in structurally inequitable environments such as those found in the UK. NUM is interested in working with sex workers and police representatives to address some of the issues in the survey related and to reducing stigma and other conditions that exclude sex workers from police protection. Some of these issues can be remedied through better communication, education and learning exchanges; commitments for accountability to sex workers through policy and practice; and clear messaging by police not only about the fact that they have a duty to protect sex workers, but also that they will, with fervour. Some sex workers, particularly those facing complex issues, need police protection the most, even if that means amnesty or a moratorium on minor offences and drug use and possession, in order to combat more serious harms against this population that NUM and others document, such as (attempted) murder, (attempted) rape and sexual assault, stalking and harassment, theft and burglary. Incremental changes in communication can also make a difference in police-sex worker relations. For example, under the Code of Practice of Victims and Crime in England and Wales (2020), victims are entitled to information for their peace of mind and protection. NUM regularly receives inquiries from sex workers about their reports to police and as the organisation does not enjoy a reciprocal relationship with police forces, we are unable to advise victims and survivors about the status of their cases. This communication with NUM would go a long way to reduce fears of retaliation.

As a charity that receive grant funds to do their work, NUM must amend past indicators of success to exclude measuring effectiveness in ways that are tied to the numbers of sex workers supported to access the legal system. This kind of criminal justice measure and outcome is important to victim support services but must be contextualised within the lived experiences of the diverse sex workers NUM serves. To be clear, NUM continues to facilitate sex workers who desire it to access police support; however, the charity’s greater responsibility is to design and deliver trauma-informed services with, by and for sex workers. This more recent positioning of NUM as fully accountable to sex workers requires it to re-prioritise stakeholders and partners. In so doing, this may put NUM at odds with entities that believe victims and survivors are expected to or required to access police. Considering NUM’s survey data, and the expressed needs of its members, the presupposition, that as stigmatised individuals, sex workers ought to access police and the court system in pursuit of justice and healing warrants reconsideration. NUM wants police services to confront the discrimination embedded in their polices and within their ranks, so that their public services become freely accessible to diverse and marginalised populations of sex workers and others in informal economies. A hostile policy environment that conflates sex work with the global trafficking agenda, a regulatory regime that trends towards the de facto criminalisation of sex workers through making their clientele illegal, and the ‘discourse of disposal’ (Lowman, 2000) that legitimises campaigns to exclude and eliminate sex workers from achieving workers’ rights and political power, all disincentivise the reporting of crimes by sex workers to police.

Thankfully, reporting by sex workers to NUM is increasing and the organisation stands ready to proceed in the ways that sex workers choose. Engagement in the legal system as a remedy for harms against this population appears not to be a sentiment held in high esteem by today’s sex industry workers who weigh the benefits and risks to becoming known to police and the state after being victimised, against the possible consequences that this might have. As the results of the survey suggest, often, the risks are simply too great. The fact that most risk their futures to access the legal system is abhorrent and a choice that no survivor ought to be forced to make. Based on their social exclusion and the uncertainties around their social and legal standing, sex workers who report crime to NUM prefer to share alerts with other sex workers to prevent crime, and forego police involvement as a matter of self-preservation.

Decriminalisation will offer a climate in which sex workers can have candid conversations about their needs and the protective potential of police services. In this kind of regulatory regime, at the very least, sex workers will be recognised as part of the labour force and as members of civil society who cannot be refused the public services that they help pay for. In a decriminalised environment, sex workers who are under protected categories of identity will have opportunities to weigh in on important policies such as the Merseyside Hate Crime model (Campbell, 2014) and help to determine the efficacy of such approaches in reducing their criminalisation and improving safety and security. NUM argued for sex worker inclusion in its submission to the Law Commission that conducted a consultation on hate crime laws in 2020 (Law Commission, 2020). Full decriminalisation would be a context in which more sex workers would be freer to participate in national consultations to determine what strategies ought to be in place beyond decriminalisation, and how adults can regulate their industries, control their working conditions, design out exploitation, prevent violence and report incidents of harm without fear. In this context, violence against sex workers would not be tolerated, and organisations such as NUM will no longer be needed to facilitate relations between sex workers and the state. Until then, the 43 police forces across England, Scotland and Wales must operate under the same guidance and policies when interacting with sex workers to bring about consistency, predictability and trust. Police forces must conceive of sex workers as a population of legally working adults, understanding them beyond paradigms and labels of ‘criminal’, ‘victim’ or ‘exploited’, and not overlook how police activities and operations may contribute to the predicaments of sex workers.

In this paper, NUM statistics on anonymous and full reports by sex workers showed downward trends in willingness to engage with police, and survey results pertaining to the obstacles that deter sex workers from including the legal system as a natural part of their justice-seeking and healing journeys. So, why report? How do we change attitudes towards sex workers in order to reduce their victimisation? How do we improve police relations and transform the legal system to such an extent that sex workers who become victims of crime feel safe to access it? The UK Governments’ End-to-End Rape Review notes that one in six rape and sexual assault victim is willing to report to police (HM, 2021). NUM’s 2020 data indicates that less than eight in 100 sex workers who disclose violence are willing to report any incident to police. NUM, as a sex worker–serving organisation, is responsible for doing its part to raise awareness about the adequacy of the legal system in the UK as it relates to its mandate of sex worker safety. Together, we can make improvements to police and public services to be more accountable to a public that includes sex workers.

Collectively, we must work with sex workers and across multi-agencies to bring about transformative changes to the legal system that does not require survivors to sacrifice their privacy, safety and security to access it in pursuit of justice.

Acknowledgements

We thank the 88 sex workers who took part in the survey that informs this paper, and we express our gratitude to all NUM members, who put their trust in NUM when they are experiencing incredible difficulty.

Data Availability

Survey data is available upon request.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Disclaimer

NUM surveys and evaluations are funded by a range of trusts and foundations who invest in our core work. This research was not specifically funded in the traditional sense.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Armstrong, L., & Fraser, C. (2020). The disclosure dilemma: Stigma and talking about sex work in the decriminalized context. Sex work and the New Zealand model: Decriminalisation and social change, 177–198.

- Basis (2021). Statement Basis Yorkshire re Managed Approach June 2021. Available at: https://basisyorkshire.org.uk/news/statement-basis-yorkshire-re-managed-approach-june-2021/ (Accessed: 6th July 2021).

- Belak, B., & Bennett, D. (2016). Evaluating Canada’s sex work laws: The case for repeal. Pivot Legal Society. Available at: https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/pivotlegal/pages/1960/attachments/original/1480910826/PIVOT_Sex_workers_Report_FINAL_hires_ONLINE.pdf?1480910826

- Benoit C, Jansson SM, Smith M, Flagg J. Prostitution stigma and its effect on the working conditions, personal lives, and health of sex workers. The Journal of Sex Research. 2018;55(4–5):457–471. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2017.1393652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BMG. (2019). Public perceptions of policing in England and Wales 2018. Available at: https://www.bmgresearch.co.uk//wp-content/uploads/2019/01/1578-HMICFRS-Public-Perceptions-of-Policing-2018_FINAL.pdf (Accessed: 4th March 2020)

- Bland L. The case of the Yorkshire Ripper: Mad, bad, beast or male? In: Radford J, Russell DEH, editors. Femicide: The politics of women killing. Open University Press; 1992. pp. 233–253. [Google Scholar]

- Bosch, E. M. (2016). Alter egos/alternative rhetorics: Belle Knox’s rhetorical construction of pornography and feminism. Available at: https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/bitstream/handle/1808/22358/Bosch_ku_0099M_14843_DATA_1.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Bowen R. Work, money and duality: Trading sex as a side hustle. Bristol University Press; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen R. Squaring up: Experiences of transition from off street sex work to square work and duality concurrent involvement in both in Vancouver, BC. Canadian Review of Sociology/revue Canadienne De Sociologie. 2015;52(4):429–449. doi: 10.1111/cars.12085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruckert, C. (2012). “The mark of disreputable labour” Pp. 55–78 in Stigma revisited: Implications of the Mark, edited by S. Hannem and C. Bruckert. Ottawa: University of Ottawa Press.

- Campbell R. Not getting away with it: Linking sex work and hate crime in Merseyside. The Policy Press; 2014. pp. 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Donato, A. (2019). Why outing a sex workers can have devastating consequences. Huffington Post, 30 March 2019, updated 22 July 02019. Available at https://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2019/03/30/sex-work-outing-stigma-canada_a_23697979/

- Easterbrook-Smith, G. (2021). Resisting division: Migrant sex work and “New Zealand working girls”. Continuum, 1–13.

- English Collective of Prostitutes (ECP). (2020). Sex workers are getting screwed by Brexit. Available at: https://prostitutescollective.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Sex-Workers-are-Getting-Screwed-by-Brexit.pdf

- Embury-Dennis, T. (2018). Sex worker in Hull ‘back out on streets’ 30 minutes after giving birth, says police officer. The Independent, 4th January. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/sex-worker-hull-give-birth-back-streets-prostitution-police-officer-a8141276.html (Accessed: 4th March 2020)

- FemmeDaemonium. (2021). The source. Available at: https://www.femmedeamon.com/the-source (Accessed: 8th July 2021).

- Her Majesty’s (HM) Government. (2021). End to end review of the criminal justice system response to rape (“The Rape Review”) CP 437. ISBN 978–1–5286–2667–5. Available at https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/994816/end-to-end-rape-review-report.pdf

- Independent.ie. (2019). Crime against sex workers ‘almost doubles’ since law change. Available at: https://www.independent.ie/breaking-news/irish-news/crime-against-sex-workers-almost-doubles-since-law-change-37957325.html (Accessed: 22 December 2020)

- Jones A. Camming: Money, power, and pleasure in the sex work industry. New York University Press; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Klambauer E. Policing roulette: Sex workers’ perception of encounters with police officers in the indoor and outdoor sector in England. Criminology & Criminal Justice. 2017;18(3):255–272. doi: 10.1177/1748895817709865. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klambauer E. On the edges of the law: Sex workers’ legal consciousness in England. International Journal of Law in Context. 2019;15(3):327–343. doi: 10.1017/S1744552319000041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lam, E. (2018). How anti-trafficking investigations and policies harm migrant sex workers. Butterfly Print: Toronto Canada. Available at https://576a91ec-4a76-459b-8d05-4ebbf42a0a7e.filesusr.com/ugd/5bd754_bbd71c0235c740e3a7d444956d95236b.pdf

- Law Commission. (2020). Hate crime laws: A consultation paper. Available at: https://s3-eu-west-2.amazonaws.com/lawcom-prod-storage-11jsxou24uy7q/uploads/2020/10/Hate-crime-final-report.pdf (Accessed: 6th July 2021).

- Lerner MJ. The belief in a just world: A fundamental delusion. Springer; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:363–385. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Longman, J., & Hatchard, S. (2016). The city that allows women to sell sex. BBC News, 12th April. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-35987536 (Accessed: 4th March 2020)

- Lowman J. Violence and the outlaw status of (street) prostitution in Canada. Violence against Women. 2000;6(9):987–1011. doi: 10.1177/10778010022182245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mac J, Smith M. Revolting prostitutes: The fight for sex workers’ rights. Verso; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Justice (2020) Code of Practice for Victims of Crime in England and Wales. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/974376/victims-code-2020.pdf (Accessed: 16th August 2021).

- Mutch, M. (2020). Prostitution no longer banned in Hessle Road. Hull Daily Mail, 22nd May. Available at: https://www.hulldailymail.co.uk/news/hull-east-yorkshire-news/prostitution-no-banned-hessle-road-4158601 (Accessed: 24th December 2020)

- NACOSA and SWEAT. (2013). Beginning to build the picture: South African national survey of sex worker knowledge, experiences and behaviour. Available at: https://www.hivsharespace.net/sites/default/files/resources/8.%20SWEAT%20National%20Survey%20final%20report_0.pdf (Accessed: 4th March 2020).

- National Police Chiefs’ Council. (2019) National policing sex work and prostitution guidance. Available at: https://library.college.police.uk/docs/appref/Sex-Work-and-Prostitution-Guidance-Jan-2019.pdf (Accessed: 2nd July 2021).

- Platt, L., Grenfell, P., Meiksin, R., Elmes, J., Sherman, S. G., Sanders, T. et al. (2018). Associations between sex work laws and sex workers’ health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of quantitative and qualitative studies. PLoS Medicine 15(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rosa, S. K. (2021). Labour has a problem with sex work. 31st March, Novara Media. Available at: https://novaramedia.com/2021/03/31/labour-has-a-problem-with-sex-work/ (Accessed: 8th July 2021).

- Sciortino, K. (2016). Sex worker and activist, Tilly Lawless, explains the whorearchy. Available at: https://slutever.com/sex-worker-tilly-lawless-interview/ (Accessed: 4th March 2020).

- Smith, J. (1992). Misogynies: Reflections on myth and malice. New York. NY: Fawcett Columbine.

- Weitzer R. Resistance to sex work stigma. Sexualities. 2018;21(5–6):717–729. doi: 10.1177/1363460716684509. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Survey data is available upon request.