ABSTRACT

Atherosclerosis (AS) is a cardiovascular disorder accompanied by endothelial dysfunction. Extensive evidence demonstrates the regulatory functions of long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) in cardiovascular disease, including AS. Here, the function of lncRNA small nucleolar RNA host gene 12 (SNHG12) in AS progression was investigated. A cell model of AS was established in human umbilical endothelial cells (HUVECs) using oxidative low-density lipoprotein (ox-LDL). CCK-8, flow cytometry, TUNEL, ELISA, and western blotting analyses were performed. Apolipoprotein E-deficient (apoE−/−) mice fed a Western diet were used as in vivo models of AS. RT-qPCR determined the levels of SNHG12, microRNA-218-5p (miR-218-5p) and insulin-like growth factor-II (IGF2). The molecular mechanisms were investigated using luciferase reporter and RNA pull-down assays. We found that SNHG12 and IGF2 expression levels were high and miR-218-5p expression levels were low in AS patients and ox-LDL-treated HUVECs. SNHG12 depletion attenuated ox-LDL-induced injury in HUVECs, whereas miR-218-5p suppression partially abated this effect. Moreover, IGF2 overexpression prevented the alleviative role of miR-218-5p in ox-LDL-treated HUVECs. SNHG12 upregulated IGF2 expression by sponging miR-218-5p. More importantly, SNHG12 increased proinflammatory cytokine production and augmented atherosclerotic lesions in vivo. Overall, SNHG12 promotes the development of AS by the miR-218-5p/IGF2 axis.

KEYWORDS: Atherosclerosis, ox-LDL, HUVECs, SNHG12, miR-218-5p, IGF2

Introduction

Atherosclerosis (AS) is a common vascular disease with an increasing morbidity, which contributes to the development of multiple clinical diseases (e.g. coronary heart diseases, peripheral vascular diseases and cerebral infarction) [1,2]. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein (Ox-LDL) contributes to the formation of atherosclerotic plaque by several mechanisms, including the induction of endothelial cell activation and dysfunction, macrophage foam cell generation, and smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration [3]. Endothelial cells (ECs) constitute the inner cell layer within the blood vessels and are primarily involved in vascular homeostasis, regulating blood flow, hemostasis, and vascular permeability [3]. Evidence indicates that the endothelial dysfunction is a major trigger in the initiation of AS [4], and it is related to the loss of the EC barrier, allowing the recruitment of monocytes and the infiltration of LDL. Oxidation of LDL is followed by macrophage foam cell formation, a powerful stimulus that initiates the inflammatory cascade reaction. Vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) are induced to migrate and proliferate into the intima, forming the major component of the atherosclerotic plaques [5]. Excessive deposition of ox-LDL could accelerate EC apoptosis through promoting inflammation and oxidative stress, which eventually leads to the occurrence and progression of AS [6]. Therefore, understanding of the mechanisms on how ox-LDL induces EC injury will help identify effective therapeutic strategies for AS.

Previous reported several in vitro models for AS. In an in vitro foam cell model constructed by incubating macrophages with ox-LDL, lysosomal function and autophagy of foam cells are compromised [7]. Ox-LDL induces the activation of WNT family member 5A (WNT5A) signaling in human aortic VSMCs, which is a canonical signaling activated in AS [8]. Ox-LDL stimulates apoptosis and inflammatory reaction in human umbilical endothelial cells (HUVECs) [9]. In this study, we established a cell model for AS in HUVECs by treating ox-LDL. Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are transcripts of long RNAs of more than 200 nucleotides that cannot translate into proteins [10]. Accumulating evidence shows that multiple lncRNAs control gene expression and play key roles in vascular biology, EC function, and the development of vascular disease [11,12]. LncRNAs have been involved in certain atherogenic processes, such as cell proliferation, apoptosis, lipid metabolism, and inflammatory response [13]. In addition, lncRNAs have been demonstrated expressed in different cell types known to be implicated in the atherogenic process (e.g. ECs, VSMCs, and macrophages) [14]. For example, lncRNA antisense non-coding RNA in the INK4 locus (ANRIL) is upregulated by ox-LDL and promotes alteration of the VSMC phenotypes [15]. LncRNA opa-interacting protein 5 antisense RNA 1 (OIP5-AS1) depletion attenuates ox-LDL-induced EC apoptosis by recruiting enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) [16]. LncRNA non-coding RNA activated by DNA damage (NORAD) plays a protective role in AS through inhibiting EC senescence and apoptosis [17]. LncRNA small nucleolar RNA host gene 12 (SNHG12) was verified to work as a tumor activator in cancers [18,19]. SNHG12 was found upregulated in brain microvascular ECs following oxygen-glucose deprivation, a cell model of ischemic stroke [20]. SNHG12 facilitates the angiogenesis after ischemic stroke by upregulating vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [21]. It was shown that SNHG12 could be a possible biomarker of pulmonary arterial hypertension [22]. These findings show the role of SNHG12 in cardiovascular disease. Moreover, a previous research showed that SNHG12 regulates the proliferation and apoptosis of ox-LDL-treated VSMCs [23]. However, the role of SNHG12 in ox-LDL-induced EC injury remains unclear.

Here, our findings revealed the upregulated SNHG12 in AS patients and ox-LDL-cultured HUVECs. The function and molecular mechanisms of SNHG12 in vitro and in vivo were investigated, suggesting that SNHG12 may be a prospective molecular for AS therapy.

Materials and methods

Specimens

Peripheral venous blood samples were collected from 30 patients diagnosed with AS and 30 healthy donors without AS and other diseases at Zhejiang Hospital (Zhejiang, China). The serum was isolated from blood samples by centrifugation at 2,000 rpm/min and kept at −80°C. Before the study, informed consents were signed by every donor. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhejiang Hospital (Zhejiang, China).

Cells

HUVECs and human embryonic kidney 293 T (HEK293T) cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; CA, USA) and maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco, USA) added with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and 0.5% penicillin and streptomycin (Gibco). All cells were incubated at 37℃ in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. Cell passages from 3 to 5 were used for this study. When cells were grown to 80%, they were treated with ox-LDL (Solarbio, Beijing, China) at 0, 10, 30, and 50 µg/ml for 24 h.

Transfection

Short hairpin RNA targeting SNHG12 (sh-SNHG12), sh-negative control (NC), miR-218-5 mimics, miR-218-5p inhibitor, and controls were obtained from GenePharm (Shanghai, China). Overexpression of SNHG12 and insulin-like growth factor-II (IGF2) was performed via cloning the full-length into the pcDNA3.1 (GenePharm). HUVECs were seeded into 6-well plates at (1 × 105 cells/well) and transfected with oligonucleotide (60 nM) or vector (0.5 µg) utilizing Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, USA) for 48 h.

Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from samples and HUVECs using TRIzol (Invitrogen). The extracted RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using a PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Takara). Then, cDNA was quantified by qPCR on an ABI7900 system (Applied Biosystems, MA) with the SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ (Takara) in a 20 µl PCR reaction. Each assay was performed in triplicate and target gene expression was normalized to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) or U6 snRNA. Expression was calculated by the 2−ΔΔCt method. The primer sequences are as follows:

SNHG12: 5ʹ-TCTGGTGATCGAGGACTTCC-3ʹ (Forward)

SNHG12: 5ʹ-ACCTCCTCAGTATCACACAT-3ʹ (Reverse)

MiR-218-5p: 5ʹ-AACACGAACTAGATTGGTACA-3ʹ (Forward)

MiR-218-5p: 5ʹ-AGTCTCAGGGTCCGAGGTATTC-3ʹ (Reverse)

IGF2: 5ʹ-AGACCCTTTGCGGTGGAGA-3ʹ (Forward)

IGF2: 5ʹ-GGAAACATCTCGCTCGGACT-3ʹ (Reverse)

GAPDH: 5ʹ-CTTCGCTCTCTGCTCCTCC-3ʹ (Forward)

GAPDH: 5ʹ-CAATACGACCAAATCCGTTG-3ʹ (Reverse)

U6: 5ʹ-GCTTCGGCAGCACATATACTAAAAT-3ʹ (Forward)

U6: 5ʹ-CGCTTCAGAATTTGCGTGTCAT-3ʹ (Reverse)

Western blotting

The aortas were homogenized in radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai) containing 4% cocktail proteinase inhibitors (Roche, Switzerland) for 3 h in ice bath. The homogenate was centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C before boiled for 10 min. The concentration of protein was quantified using a bicinchoninic acid assay kit (Beyotime). Cell or tissue lysates (50 μg protein per lane) were separated on the sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (10%) gels at a voltage of 120 V for 2 h and then transferred onto the polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Germany) for 1 h at the 100 V. The membranes were blocked for 1 h at room temperature using 5% skimmed milk, before being incubated with primary antibodies including proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) (1:1,000, ab92552, Abcam), Cyclin D1 (1:1,000, ab40754), interleukin-6 (IL-6) (1:1,000, ab233706), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (1:1,000, ab183218), IGF2 (1:1,000, ab177467), and GAPDH (1:10,000, ab181602) overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, the goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5,000, ab205718) was incubated with the membranes for 2 h. The membranes were developed with an improved chemiluminescence substrate. Meanwhile, the samples were examined using an enhanced chemoluminescence kit (Takara). The densitometry values were determined using Image J software and normalized to GAPDH values.

Subcellular fractionation

Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions of HUVECs were separated using a Cytoplasmic & Nuclear RNA Purification Kit (Norgenbiotek, Canada). RNA was extracted and the SNHG12 level was measured by RT-qPCR. GAPDH or U6 was respectively as the control of nuclear or cytoplasmic fraction.

Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8)

HUVECs were seeded into 96-well plates (5 × 103 cells/well). Next, 10 µL CCK-8 (5 mg/mL; (Biotechwell, Shanghai, China) was added to each well and left in an incubator for 2 h under specific conditions. The optical density value of each well at 450 nm was examined by a microplate reader (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Flow cytometry

For cell apoptosis analysis, it was tested using Annexin-V fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-propidium iodide (PI) Apoptosis Detection Kit (Beyotime) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. HUVECs were collected, digested with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)-free trypsin (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and washed with phosphate saline solution (PBS). Cells were suspended in 100 μl 1× Binding buffer at a density of 3 × 105 cells/mL, followed by double staining with Annexin V-FITC (5 μL) and PI (10 μL). After incubation in the dark for 15 min, apoptosis was measured using flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, USA).

For cell cycle analysis, 3 × 104 HUVECs were collected and washed, and then fixed in 70% ethanol overnight at 4°C. After a low-speed centrifugation for 5 min, the cells were cultured with 10 μL RNase for 10 min at 37°C and stained with 1% propidium iodide in the dark for 30 min. Cell cycle in different phases was analyzed by flow cytometry.

TdT-mediated dUTP Nick-End Labeling (TUNEL)

In brief, HUVECs in 24-well plates (2 × 105 cells/well) were permeabilized by 0.1% Triton X-100 for 8 min and fixed in H2O2 (3% in methanol) for 5 min. After PBS washing, cells were labeled by 50 μL TdT labeling reaction mix for 1 h and nuclei were stained with DAPI (Beyotime). TUNEL-positive nuclei were observed under a fluorescence microscopy (Olympus, Japan). The percent of apoptosis was quantified using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics Inc., MD, USA).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The concentrations of cytokines including IL-6 and TNF-α were determined using the ELISA kits (Bogoo Biological Technology, Shanghai) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Absorbance was measured with an ELx800 Absorbance Microplate Reader (BioTek, USA).

Bioinformatics analysis

The online software starBase 3.0 (http://starbase.sysu.edu.cn/index.php) was used to predict the potential binding sites between SNHG12 and miR-218-5p (search category: Pan-Cancer, 8 cancer), as well as miR-218-5p and IGF2 3ʹ untranslated regions (3ʹUTR) (search category: miRanda, RNA22, and microT).

Luciferase reporter assay

Wild-type SNHG12 or IGF2 at the miR-218-5p binding site was inserted into the pmirGLO downstream (Promega, USA) to generate the wild-type luciferase vectors of SNHG12 (SNHG12-Wt) or IGF2 (IGF2-Wt). Mutants were generated by mutating the seed sites on miR-218-5p sequence. The above plasmids were transfected into HUVECs or HEK293T cells with miR-218-5p mimics or control. Detection of luciferase activity was conducted by a luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) after 48 h.

RNA pull-down

To verify the relationship between SNHG12 and miR-218-5p, biotin-labeled SNHG12 or biotin-labeled miR-218-5p probe as well as NC probe was synthesized by Sangon Biotech Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). HUVECs were lysed in the specific lysis buffer (Sigma-Aldrich) containing RNase inhibitor (Beyotime) for 20 min. The lysates were centrifugated at 12,000 × g for 12 min at 4°C. Final concentration of Bio-SNHG12 or Bio-miR-218-5p was 20 µM with standard protocol of RNA oligos (Lipofectamine 2000, Invitrogen). Transfection was done for 24 h. Next, 20 µl Dynabeads M-280 Streptavidin beads (Life Technologies) were activated according to manufacturer’s protocol. The beads were blocked with 10 µg/ml RNase-free bovine serum albumin and yeast tRNA (Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min at 4°C. After washing the beads with lysis buffer, the lysates were incubated with beads for 3 h at 4°C. After elution twice with 500 µl pre-cooled lysis buffer, thrice with low salt buffer, and once with high salt buffer in succession, the bound RNA was purified using TRIzol (Invitrogen) and then the expression of SNHG12 or miR-218-5p was measured by RT-qPCR. Sequences of targeted probe are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sequences of targeted probe for RNA pull-down assay

| Biotin-labeled SNHG12 probe CCTTTCTCCCCGCCGCATTCCCGGTGTCGACTTACTAGCTGCAAGCCTCTGCCTGCCTTC |

|---|

| CTGCGCGCCGTTCCCCGCTAGTCGCTGCTGCTGGCGCGCACTCGCCGGGTTTTTCCTCCC |

| ACGGCCTCGAGATGGTGGTGAATGTGGCACGGAGGAGCCGGGCCTTCCAACCCGGTGGGC |

| CCGAGCTCCGAAAGGCCCCCTCGGCAGTGAGAGGGGCGGGAGCCCGCGGGGGCCGCGCCC |

| TTCTCTCGCTTCGGACTGCGCAACGCTGCGCTCTGGGCTGACAGGCGGATAAAACGGTCC |

| CATCAAGACTGAGAAAAAGCACACCAGCTATTGGCACAGCGTGGGCAGTGGGGCCTACAG |

| GATGACTGACTTAGTCTACAGAGATCCCGGCGTACTTAAGCAGATGAAGACTCTTAAGAT |

| GACAGAAGGTGATTTTTCTGGTGATCGAGGACTTCCGGGGTAATGACAGTGATGAAATGC |

| AGGGGACCTGGTTGCCCCCAAGTTTCCTGGCAGTGTGTGATACTGAGGAGGTGAGCTTGT |

| TTCTGGAGCTGTGCTTTAAGATTCATGTTACATGTAAAGCTGTCCTCATTTGTGACTATG |

| GACCTATGGAGTTGGGACAATCTCTATGGGAAGCAGAAGGCAAGGACCCCGGTCATTTTA |

| GGTAGAAACAACAGCATGCTAATGCAAAAAATTATGCAGTGTGCTACTGAACTTCAGAGG |

| TGATCAATAAAAGAAGAATAAAAAGACTAATAAAAGTAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA |

| NC probe |

| GGAAAGAGGGGCGGCGTAAGGGCCACAGCTGAATGATCGACGTTCGGAGACGGACGGAAG |

| GACGCGCGGCAAGGGGCGATCAGCGACGACGACCGCGCGTGAGCGGCCCAAAAAGGAGGG |

| TGCCGGAGCTCTACCACCACTTACACCGTGCCTCCTCGGCCCGGAAGGTTGGGCCACCCG |

| GGCTCGAGGCTTTCCGGGGGAGCCGTCACTCTCCCCGCCCTCGGGCGCCCCCGGCGCGGG |

| AAGAGAGCGAAGCCTGACGCGTTGCGACGCGAGACCCGACTGTCCGCCTATTTTGCCAGG |

| GTAGTTCTGACTCTTTTTCGTGTGGTCGATAACCGTGTCGCACCCGTCACCCCGGATGTC |

| CTACTGACTGAATCAGATGTCTCTAGGGCCGCATGAATTCGTCTACTTCTGAGAATTCTA |

| CTGTCTTCCACTAAAAAGACCACTAGCTCCTGAAGGCCCCATTACTGTCACTACTTTACG |

| TCCCCTGGACCAACGGGGGTTCAAAGGACCGTCACACACTATGACTCCTCCACTCGAACA |

| AAGACCTCGACACGAAATTCTAAGTACAATGTACATTTCGACAGGAGTAAACACTGATAC |

| CTGGATACCTCAACCCTGTTAGAGATACCCTTCGTCTTCCGTTCCTGGGGCCAGTAAAAT |

| CCATCTTTGTTGTCGTACGATTACGTTTTTTAATACGTCACACGATGACTTGAAGTCTCC |

| ACTAGTTATTTTCTTCTTATTTTTCTGATTATTTTCATTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTT |

| Biotin-labeled miR-218-5p probe TTGTGCTTGATCTAACCATGT |

| NC probe AACACGAACTAGATTGGTACA |

Lentivirus construction

SNHG12 cDNA was amplified using PCR and cloned into pLOV-EF1a-PuroR-CMV-EGFP-2A-3 FLAG vector. Cloned sequence was verified by DNA sequencing. This construct was referred to as LV- SNHG12 and empty control vector was LV-Mock. SNHG12 overexpression was verified by RT-qPCR.

Animals

The study was approved by the Animal Experimental Committee of Zhejiang Hospital and conformed to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US NIH (revised 1996). Male apolipoprotein E deficient (apoE)−/− mice on a C57BL/6 J genetic background were used (Vital River Co. Ltd, Beijing, China). Mice were randomized into 4 groups: control, AS, LV-Mock, and LV-SNHG12. Each group included 6 mice. Mice were housed 5 per cage (Cage bedding source) at 25°C on a 12 h light/dark cycle and fed a Western diet (21% fat, 0.3% cholesterol; Research Diets) for 12 wks and simultaneously injected with LV-NC, or LV-SNHG12 (2 × 109 TU/mL) via the tail vein once every 3 wks. Body weight was monitored at regular intervals. After 12 wks rearing, mice were fasted for 4 h, then placed under general anesthesia. Anesthetic used was 1% pentobarbital sodium, with the amount given dependent upon animal weight (40 mg/kg). Blood samples were collected from the retro-orbital venous plexus using a capillary tube. The mice were then sacrificed by cervical dislocation and aortic root tissues were collected for histological analyses.

Histological analysis of aortic roots tissues

Cryosections (10 μm thick) of the aortic roots were stained with Oil Red O. Images of stained aortic root sections were acquired using an Olympus BX50 microscope. The percentage of Oil Red O positive area in total aortic root atherosclerotic lesion area was calculated using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics Inc., MD, USA).

Blood lipid analysis

Blood lipid parameters including triglyceride (TG) and total cholesterol (TC) were determined using commercial enzymatic colorimetric assay kits (JianCheng Biotechnology, Shanghai, China) according to the instructions of manufacturers.

Statistical analysis

SPSS version 20.0 (St Louis, USA) software was used for statistical analysis. The significance of differences between two groups was evaluated using Student’s t-test, whereas one-way analysis of variance (ANOVAs) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test was used for multiple comparisons. The data from at least three independent experiments are expressed as the mean ± SD. P < 0.05 was statistically significant.

Results

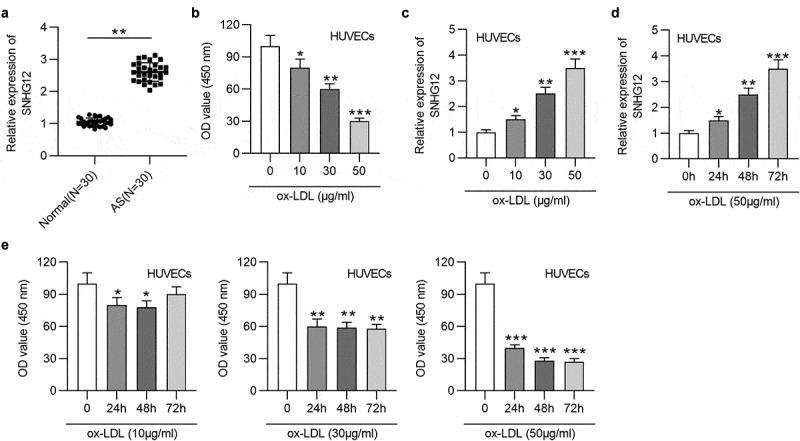

SNHG12 is upregulated both in AS

First, the SNHG12 level in AS patients’ serum and normal serum was evaluated. In Figure 1(a), SNHG12 expression was significantly elevated in AS patients. To detect the impact of ox-LDL in EC injury, HUVECs were exposed to various concentrations of ox‑LDL (0, 10, 30, and 50 µg/ml) for 24 h, and cell proliferation was detected by CCK‑8 assay. Compared to the untreated group, ox-LDL dose-dependently reduced HUVEC proliferation (Figure 1(b)). Moreover, an obvious dose-dependent upregulation of SNHG12 expression was detected in ox-LDL-cultured HUVECs (Figure 1(c)). Moreover, SNHG12 expression was also significantly increased with the addition of ox‑LDL (60 µg/ml) in a time‑dependent manner (Figure 1(d)). Then, HUVECs were exposed to 10 µg/ml, 30 µg/ml, or 50 µg/ml ox-LDL, respectively, for 0, 24, 48, and 72 h. It was shown that the proliferation of HUVECs was most significantly inhibited by 50 µg/ml ox-LDL compared to 10 µg/ml and 30 µg/ml (Figure 1(e)). Therefore, subsequent functional experiments were conducted in HUVECs treated with 50 µg/ml ox-LDL for 24 h.

Figure 1.

SNHG12 is upregulated in AS. (a) The SNHG12 level in AS patients’ sera (n = 30) and normal sera (n = 30) was determined by RT-qPCR. HUVECs were treated with various concentrations of ox‑LDL (0, 10, 30, and 50 µg/ml) for 24 h, and (b) cell proliferation was examined using CCK-8, (c) SNHG12 expression was determined by RT-qPCR. (d) HUVECs were treated with 50 µg/ml ox-LDL for 0, 24, 48 and 72 h, and SNHG12 expression was determined by RT-qPCR. (e) HUVECs were exposed to 10 µg/ml, 30 µg/ml, or 50 µg/ml ox-LDL, respectively, for 0, 24, 48 and 72 h, and cell proliferation was detected by CCK-8. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

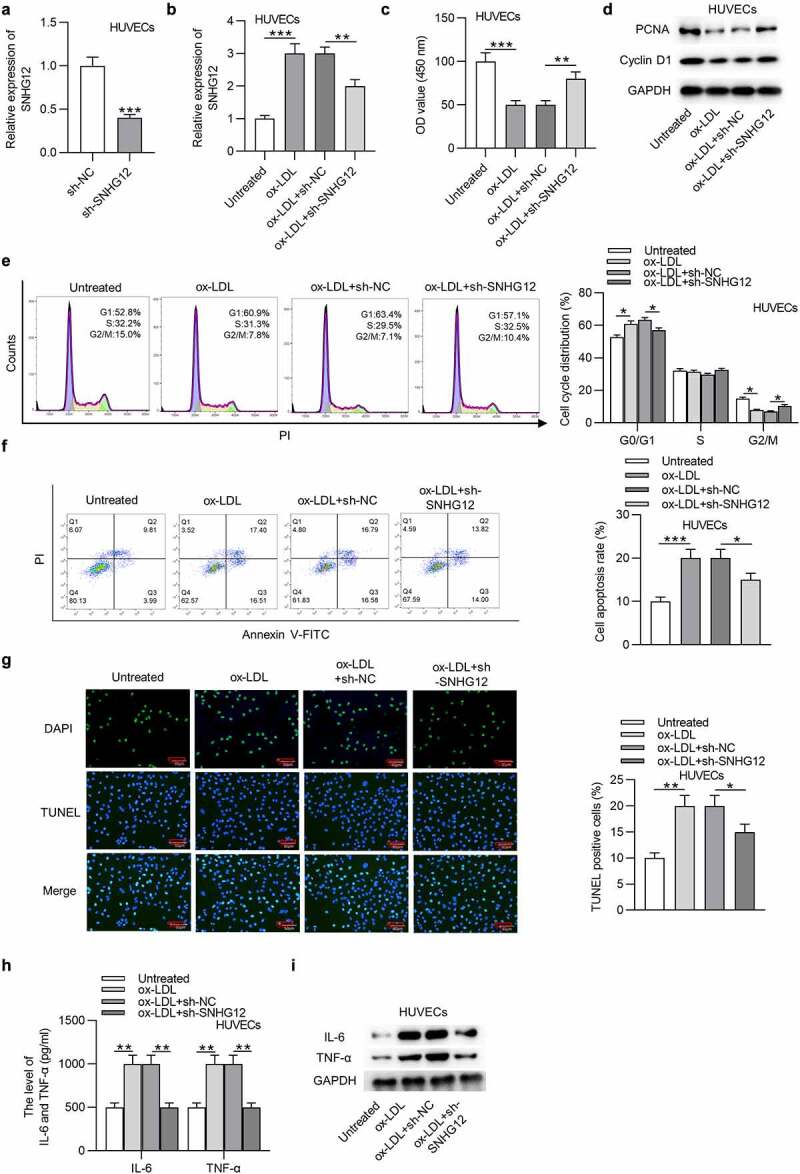

SNHG6 depletion attenuates ox-LDL-induced injury in HUVECs

To explore the function of SNHG12 in AS, sh-SNHG12 was transfected into HUVECs, and the efficiency was demonstrated by RT-qPCR. The SNHG12 level was significantly reduced in HUVECs after transfection (Figure 2(a)). Additionally, sh-SNHG12 reduced the SNHG12 expression upregulated by ox-LDL (Figure 2(b)). CCK-8 indicated that SNHG12 depletion restored cell proliferation inhibited by ox-LDL (Figure 2(c)). As shown by western blotting, the levels proliferation-related proteins (PCNA and Cyclin D1) were also downregulated after ox-LDL treatment while were restored after silencing SNHG12 (Figure 2(d)). Flow cytometry revealed that ox-LDL led to an arrest at G0/G1 phase, while this effect was eliminated by sh-SNHG12 (Figure 2(e)). The apoptosis of HUVECs was assessed using flow cytometry and TUNEL assays. We found that SNHG12 knockdown impeded the apoptosis of HUVECs exposed to ox-LDL (Figure 2(f,g)). Inflammation is a main event involved in the pathogenesis of AS. Thus, we explored whether SNHG12 mediates AS progression through affecting inflammatory response. Results from ELISA and western blotting indicated that ox-LDL significantly increased IL-6 and TNF-α levels, while downregulated SNHG12 alleviated inflammation in ox-LDL-treated HUVECs (Figure 2(h,i)). These findings suggest that SNHG12 knockdown attenuates ox-LDL-induced injury in HUVECs.

Figure 2.

SNHG6 depletion attenuates ox-LDL-induced injury in HUVECs. (a) The SNHG12 level in HUVECs transfected with sh-SNHG12 was measured by RT-qPCR. HUVECs were transfected with sh-SNHG12 and treated with or without 50 µg/ml ox-LDL for 24 h. (b) SNHG12 expression was determined by RT-qPCR. (c) Cell proliferation was assessed by CCK-8. (d) The levels proliferation-related proteins (PCNA and Cyclin D1) were detected by western blotting. (e and f) Cell cycle and apoptosis were assessed by flow cytometry. (g) Cell apoptosis was estimated by TUNEL. (h and i) The levels of IL-6 and TNF-α were measured by ELISA and western blotting. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

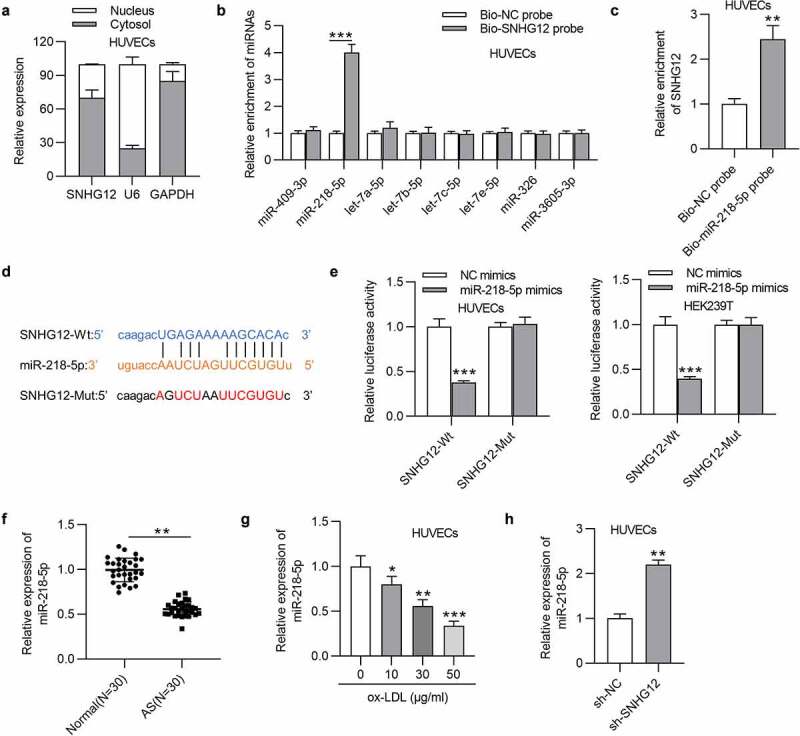

SNHG12 sponges miR-218-5p

LncRNAs can act miRNA sponges to regulate protein-coding gene expression and therefore form a competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) network [24]. To explore the mechanism addressed by SNHG12, cell cytoplasm/nucleus fraction analysis was performed to determine the subcellular location of SNHG12 in HUVECs. SNHG12 was primarily distributed in the cytoplasm of HUVECs (Figure 3(a)), suggesting the possible involvement of SNHG12 in ceRNA network. We thus investigated the miRNAs that SNHG12 could bind to. The data from starBase (search category: Pan-Cancer, eight cancer) revealed that there are eight miRNAs containing the predicted binding sites for SNHG12. We found that only miR-218-5p was enriched in the Bio-SNHG12 pull-down pellets compared to the other miRNAs in HUVECs (Figure 3(b)). And, in parallel, SNHG12 was significantly enriched in the Bio-miR-218-5p in HUVECs, which comprehensively demonstrates the interactions between SNHG12 and miR-218-5p (Figure 3(c)). Complementary sequences between SNHG12 and miR-218-5p are shown in Figure 3(d). As revealed, miR-218-5p greatly inhibited the luciferase activity in HUVECs and HEK293T cells transfected with SNHG12-Wt but showed little effect on SNHG12-Mut (Figure 3(e)). We further found that the miR-218-5p level was obviously downregulated in the serum sample from AS patients (Figure 3(f)), and a dose-dependent decrease in miR-218-5p expression was observed in ox-LDL-treated HUVECs (Figure 3(g)). Subsequently, RT-qPCR showed that depletion of SNHG12 increased miR-218-5p expression in HUVECs (Figure 3(h)). The above findings confirm that SNHG12 acts as a sponge for miR-218-5p in HUVECs.

Figure 3.

SNHG12 sponges miR-218-5p. (a) The subcellular location of SNHG12 in HUVECs was detected by cell cytoplasm/nucleus fraction analysis. (b) The enrichment of miRNAs in the biotinylated SNHG12 was detected by RT-qPCR. (c) The enrichment of SNHG12 in the biotinylated miR-218-5p was assessed by RT-qPCR. (d) Predicted binding site of SNHG12 to miR-218-5p. (e) Luciferase activity was determined in HUVECs and HEK293T cells co-transfected with NC mimics or miR-218-5p mimics and SNHG12-Wt or SNHG12-Mut. (f) The miR-218-5p level in AS patients’ sera (n = 30) and normal sera (n = 30) was determined by RT-qPCR. (g) MiR-218-5p expression in HUVECs treated with ox-LDL. (h) MiR-218-5p expression in HUVECs transfected with sh-SNHG12. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

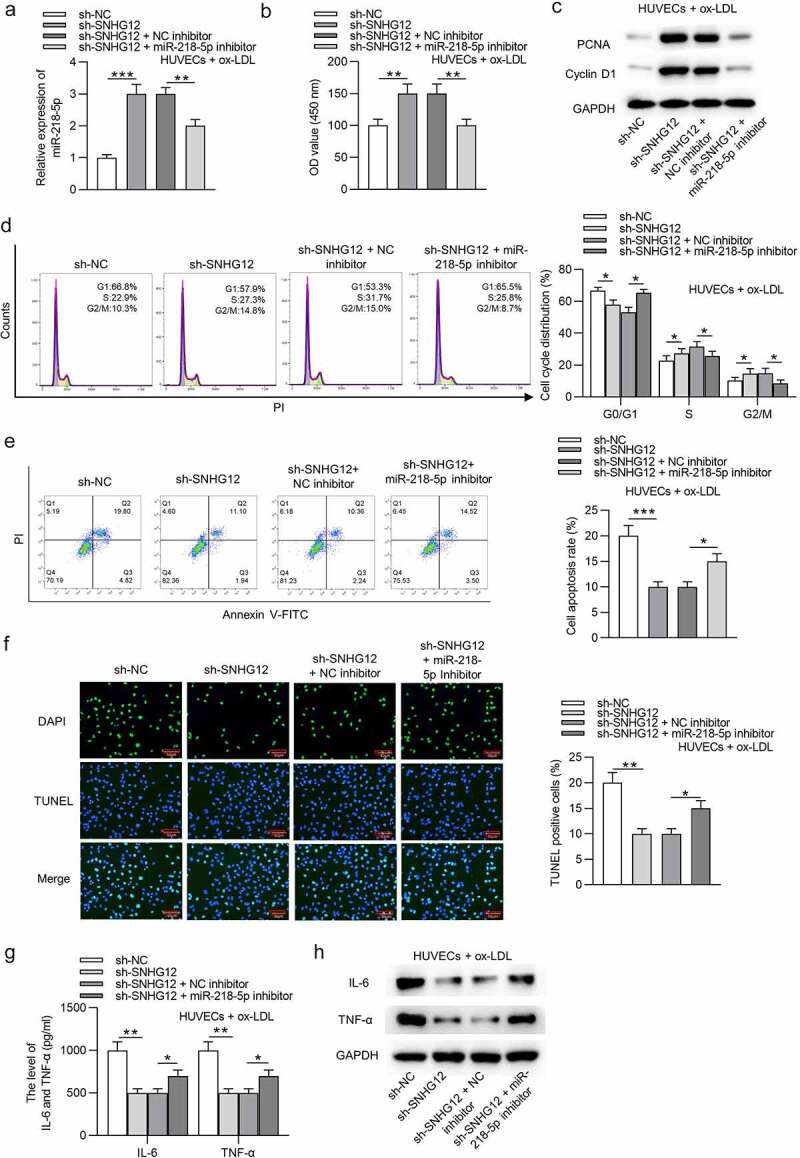

SNHG12 regulates ox-LDL-induced injury in HUVECs by miR-218-5p

The ox-LDL-treated HUVECs were transfected with sh-NC, sh-SNHG12, sh-SNHG12 + NC inhibitor, or sh-SNHG12 + miR-218-5p inhibitor. As displayed in Figure 4(a), sh-SNHG12 significantly elevated miR-218-5p expression in HUVECs, which was reversed by miR-218-5p inhibitor. Subsequently, miR-218-5p inhibitor reduced the sh-SNHG12-induced promotive effect on proliferation in ox-LDL-treated HUVECs, as shown by CCK-8 and western blotting (Figure 4(b,c)). Silencing SNHG12 promoted the cell cycle progression which was then inhibited by downregulated miR-218-5p in ox-LDL-treated HUVECs (Figure 4(d)). MiR-218-5p knockdown also restored cell apoptosis inhibited by SNHG12 depletion (Figure 4(e,f)). In addition, miR-218-5p inhibitor eliminated the inhibitory effect of sh-SNHG12 on IL-6 and TNF-α levels in ox-LDL-treated HUVECs (Figure 4(g,h)). These data suggest that SNHG12 functions in ox-LDL-treated HUVECs by miR-218-5p.

Figure 4.

SNHG12 regulates ox-LDL-induced injury in HUVECs by miR-218-5p. Ox-LDL-treated HUVECs were transfected with sh-NC, sh-SNHG12, sh-SNHG12 + NC inhibitor, or sh-SNHG12 + miR-218-5p inhibitor. (a) MiR-218-5p expression was determined by RT-qPCR. (b) Cell proliferation was detected by CCK-8. (c) The levels proliferation-related proteins (PCNA and Cyclin D1) were detected by western blotting. (d and e) Cell cycle and apoptosis were measured by flow cytometry. (f) Cell apoptosis was estimated by TUNEL. (g and h) The levels of IL-6 and TNF-α were measured by ELISA and western blotting. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

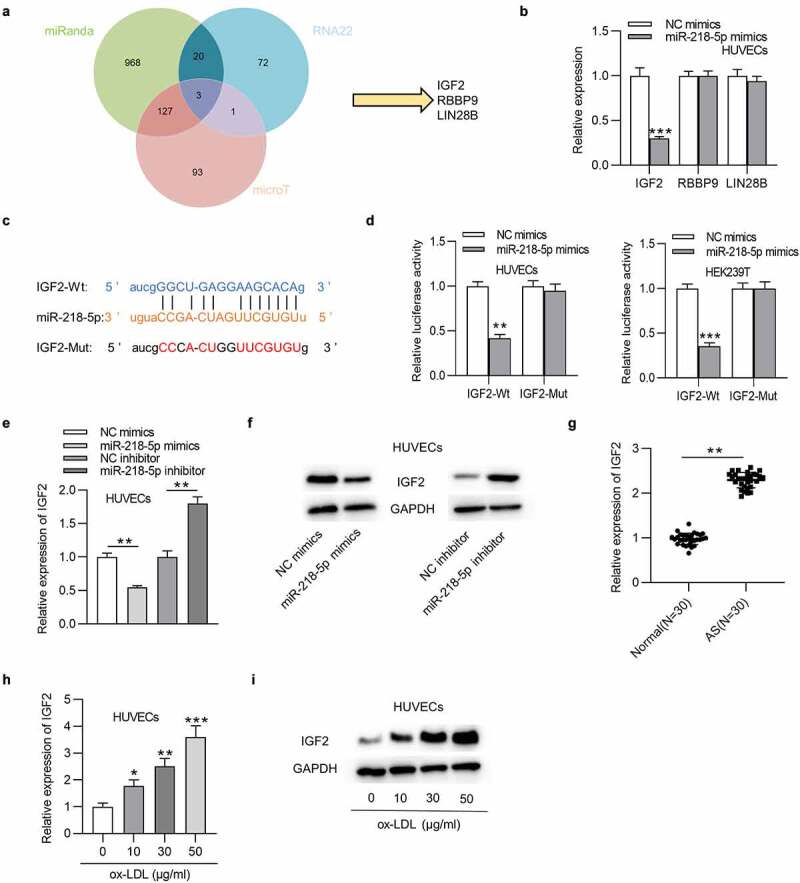

IGF2 is targeted by miR-218-5p

To identify the functional targets of miR-218-5p, we searched the starBase website. The intersection results of search parameters (miRanda, RNA22, and microT) contain 3 genes (IGF2, RBBP9, and LIN28B) (Figure 5(a)). RT-qPCR revealed that only IGF2 was downregulated in HUVECs after miR-218-5p elevation (Figure 5(b)). Then the combining capacity between miR-218-5p and IGF2 was tested. Results showed that miR-218-5p overexpression induced a notable prevention in the luciferase activity of SNHG12-Wt plasmids in HUVECs and HEK293T cells but failed to influence the activity of SNHG12-Mut plasmids (Figure 5(c,d)). RT-qPCR and western blotting indicated that miR-218-5p mimics downregulated the IGF2 level, and miR-218-5p inhibitor had an opposite impact in HUVECs (Figure 5(e,f)). Furthermore, IGF2 expression was increased in AS patients (Figure 5(g)). A dose-dependent upregulation in the IGF2 levels was detected in ox-LDL-cultured HUVECs (Figure 5(h,i)). Overall, miR-218-5p could target IGF2 in HUVECs.

Figure 5.

IGF2 is targeted by miR-218-5p. (a) Potential mRNAs of miR-218-5p shown by Venn diagram. (b) The mRNA expression in HUVECs transfected with miR-218-5p mimics. (c) Predicted binding site of IGF2 to miR-218-5p. (d) The interaction of IGF2 with miR-218-5p was validated by luciferase reporter assay. (e and f) IGF2 expression in HUVECs transfected with miR-218-5p mimics, miR-218-5p inhibitors, or control was measured by RT-qPCR and western blotting. (g) The IGF2 level in AS patients’ sera (n = 30) and normal sera (n = 30) was determined by RT-qPCR. (h and i) IGF2 expression in HUVECs treated with ox-LDL. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

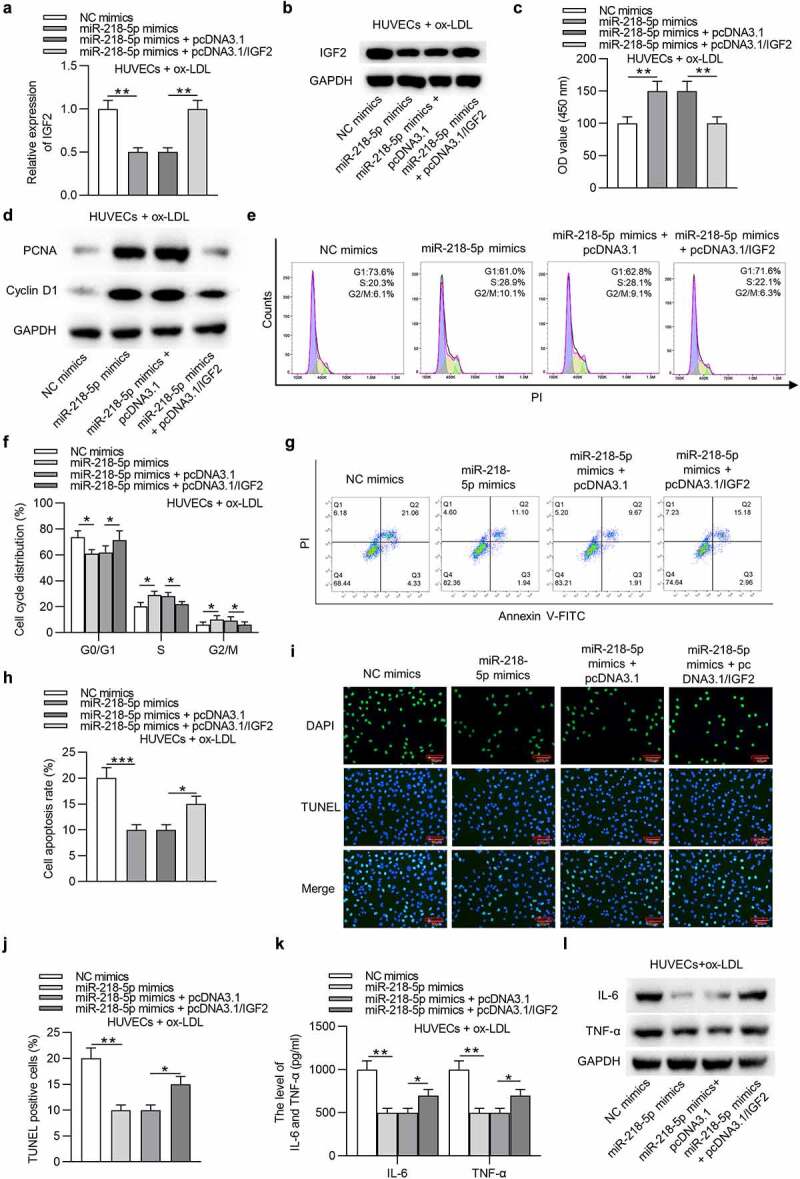

MiR-218-5p regulates ox-LDL-induced injury in HUVECs by targeting IGF2

As Figure 6(a,b) indicated, the transfection of pcDNA3.1/IGF2 significantly restored the IGF2 mRNA and protein expression decreased by overexpression of miR-218-5p mimics in HUVECs. The following functional assays demonstrated that overexpression of miR-218-5p promoted cell proliferation and inhibited apoptosis in ox-LDL-treated HUVECs, and these results were all reversed by overexpression of IGF2 (Figure 6(c–j)). Moreover, IGF2 offset the miR-218-5p overexpression-mediated inhibition on IL-6 and TNF-α levels in ox-LDL-treated HUVECs (Figure 6(k,l)). Therefore, we concluded that upregulation of IGF2 attenuates the role of miR-218-5p in ox-LDL-treated HUVECs.

Figure 6.

MiR-218-5p regulates ox-LDL-induced injury in HUVECs by targeting IGF2. Ox-LDL-treated HUVECs were transfected with NC mimics, miR-218-5p mimics, miR-218-5p mimics + pcDNA3.1, or miR-218-5p mimics + pcDNA3.1/IGF2. (a and b) IGF2 mRNA and protein expression was determined by RT-qPCR and western blotting. (c) Cell proliferation was detected by CCK-8. (d) The levels proliferation-related proteins (PCNA and Cyclin D1) were detected by western blotting. (e-h) Cell cycle and apoptosis were assessed by flow cytometry. (i and j) Cell apoptosis was estimated by TUNEL. (k and l) The levels of IL-6 and TNF-α were measured by ELISA and western blotting.*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

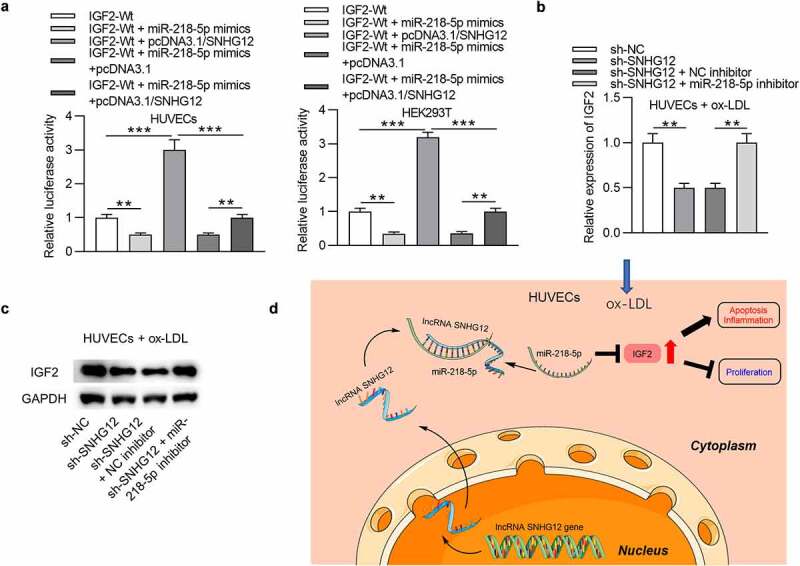

SNHG12 upregulates IGF2 expression by miR-218-5p

Subsequently, we tested the relationship among SNHG12, miR-218-5p, and IGF2. As exhibited in Figure 7(a), miR-218-5p greatly eliminated the luciferase activity of IGF2-Wt plasmids in HUVECs and HEK293T cells, while pcDNA3.1/SNHG12 exerted an opposite effect. Additionally, upregulation of SNHG12 abolished the inhibitory role of miR-218-5p. Then RT-qPCR detected the influences of SNHG12 or miR-218-5p on IGF2 expression. The results suggested that silencing of SNHG12 caused a downregulated expression of IGF2, while depletion of miR-218-5p abrogated the SNHG12 knockdown effect on IGF2 expression in ox-LDL-treated HUVECs (Figure 7(b,c)). These findings showed that SNHG12 upregulates IGF2 expression by controlling miR-218-5p availability. A schematic displays the SNHG12/miR-218-5p/IGF2 regulatory axis in ox-LDL-treated HUVECs (Figure 7(d)).

Figure 7.

SNHG12 upregulates IGF2 expression by miR-218-5p. (a) Luciferase activity in HUVECs and HEK293T cells transfected with IGF2-Wt, IGF2-Wt + miR-218-5p mimics, IGF2-Wt + pcDNA3.1/SNHG12, IGF2-Wt + miR-218-5p mimics + pcDNA3.1, or IGF2-Wt + miR-218-5p mimics + pcDNA3.1/SNHG12. (b and c) IGF2 expression after transfection with sh-NC, sh-SNHG12, sh-SNHG12 + NC inhibitor, or sh-SNHG12 + miR-218-5p inhibitor was determined by RT-qPCR and western blotting. (d) A schematic showing the SNHG12/miR-218-5p/IGF2 regulatory axis in ox-LDL-treated HUVECs. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

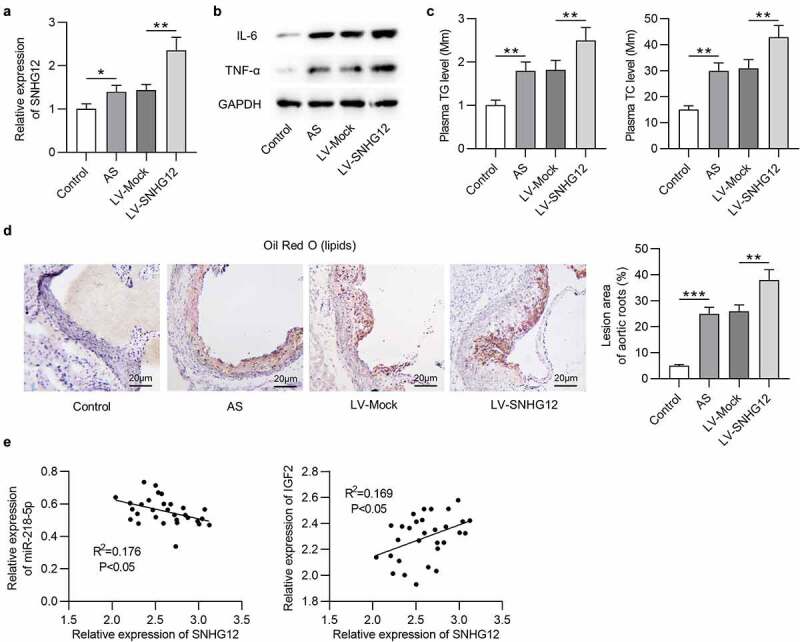

SNHG12 promotes the development of AS in vivo

To ascertain whether the findings of the in vitro studies represent events in vivo, an investigation into whether SNHG12 affects AS progression in an in vivo model of AS was carried out. SNHG12 expressing lentivirus or a mock empty control lentivirus was injected into apoE−/− mice. RT-qPCR confirmed overexpression of SNHG12 in the serum of mice, especially in mice injected with the SNHG12 expressing lentivirus as compared with mice injected with the mock lentivirus (Figure 8(a)). Western blotting analysis of aortic tissues showed that SNHG12 overexpression resulted in increased IL-6 and TNF-α protein levels (Figure 8(b)). Furthermore, mice with LV-SNHG12 had higher triglycerides and total cholesterol levels than control mice (Figure 8(c)). Staining aortic roots with Oil Red O showed that mice overexpressing SNHG12 had larger Oil Red O positive areas in atherosclerotic plaques than control mice (Figure 8(d)). We further found a negative expression correlation between SNHG12 and miR-218-5p as well as a positive expression relationship between SNHG12 and IGF2 in the blood samples of mice (Figure 8(e)).

Figure 8.

SNHG12 promotes the development of AS in vivo. (a) SNHG12 expression in the serum of mice was detected by RT-qPCR. (b) Western blotting analysis of the IL-6 and TNF-α protein levels in aortic root tissues. (c) Plasma levels of triglyceride (TG) and total cholesterol (TG) in each group. (d) Aortic root cross-sections stained with Oil Red O (for lipids) in each group. (e) Expression correlation among SNHG12, miR-218-5p, and IGF2 in the serum of mice. N = 6. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001

Discussion

Atherosclerosis (AS) is a complex chronic disorder threatening human life [25]. Ox-LDL is a widely-recognized risk factor implicated in the occurrence and progression of AS through promoting form cell formation, EC injury, plaque formation, and inflammatory cytokine release [26,27]. Understanding of the exact mechanisms on how ox-LDL induces EC injury may help develop new approaches for AS treatment. Our work showed that ox-LDL stimulated HUVEC injury by inhibiting cell proliferation and facilitating cell apoptosis and inflammation. Although the effect of ox-LDL in AS has been well clarified, the regulatory mechanisms in it remain further investigations.

Growing evidence indicates that lncRNAs are differentially expressed in AS and participate in ox-LDL-induced HUVEC injury, such as lncRNA phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) [28] and lncRNA small nucleolar RNA host gene 6 (SNHG6) [29]. In this work, our data revealed that SNHG12 was high both in AS patients and ox-LDL-cultured HUVECs. Functionally, SNHG12 knockdown effectively attenuated ox-LDL-induced injury of HUVECs through restoring cell function and reducing inflammatory response and apoptosis. More importantly, SNHG12 increased proinflammatory cytokine production and augmented atherosclerotic lesions in vivo. These data demonstrated that SNHG12 promotes AS progression in vitro and in vivo. LncRNAs can act miRNA sponges to regulate protein-coding gene expression [30]. Moreover, lncRNAs were demonstrated to exert regulatory functions in AS by interacting with miRNAs [31,32]. Based on this, we intended to verify whether SNHG12 sponges its specific miRNAs to regulate AS progression. Our results revealed that SNHG5 was mainly distributed in the cytoplasm of HUVECs, suggesting that SNHG5 may function as a ceRNA for miRNAs at the posttranscriptional level. The prediction of online tools shows that miR-218-5p has a binding site for SNHG12. Studies have reported the interactions between SNHG12 and miR-218-5p in gastric cancer and non-small cell lung cancer [33,34]. Here, we confirmed the binding ability of SNHG12 to miR-218-5p in HUVECs. MiR-218-5p was reported to function as an anti-oncogene with a poor expression in some cancers [35,36]. It has been shown that miR-218-5 has a good diagnostic value for coronary heart disease [37]. Additionally, the protective effect of miR-218-5p on EC injury was uncovered. Overexpressed miR-218-5p suppresses the apoptosis of HUVECs in Henoch-Schonlein Purpura by targeting HMGB1 [38]. In this study, we found that miR-218-5p was underexpressed in AS patients and in ox-LDL-treated HUVECs. Consistent with previous results, our study showed that miR-218-5p depletion aggravated the SNHG12 knockdown-attenuated HUVEC injury through suppressing cell proliferation and promoting apoptosis and inflammatory reaction, suggesting that SNHG12 functions in ox-LDL-treated HUVECs by miR-218-5p.

MiRNAs play regulatory roles by promoting target degradation or suppressing translation [39]. IGF2 was validated to be targeted by miR-218-5p, which was negatively modulated by miR-218-5p. Existing reports document that IGF2 acts as a key regulator in HUVEC injury and atherosclerosis events. For instance, IGF2 targeted by miR-210-3p participates in the modulation of lipid accumulation and inflammation in AS [40]. The lncRNA taurine-up regulated gene 1 (TUG1)/miR-148b/IGF2 axis controls the proliferation and apoptosis of ox-LDL-cultured HUVECs [41]. Additionally, IGF2 expression was elevated in ox-LDL-treated VSMCs and macrophages [42,43]. These reports suggested that IGF2 may aggravate ox-LDL-stimulated cell injury. Here, we verified that overexpression of IGF2 prevented the protective effect of miR-218-5p on ox-LDL-induced injury in HUVECs, suggesting that IGF2 may facilitate the development of AS. In addition, SNHG12 was a regulator of IGF2 by controlling miR-218-5p availability.

In summary, the present study has demonstrated a novel role of SNHG12 in inhibiting the development of AS and uncovered a novel mechanism underlying the regulation of SNHG12. SNHG12 upregulates IGF2 expression by sponging miR-218-5p, which promotes AS progression in vitro and in vivo. This may provide a potential therapeutic target for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. However, some limitations in this study are worth mentioning. First, it would be better to expand the sample size in subsequent experiments to enhance persuasion of our findings. Second, we would also conduct a research on some potential signaling pathways related to the SNHG12/miR-218-5p/IGF2 axis in the future study.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate all participators in this study.

Funding Statement

This work supported by Basic Public Welfare Research Project of Zhejiang Province [No. LGJ18H020001].

Disclosure statement

The authors report no declarations of interest.

References

- [1].Khyzha N, Alizada A, Wilson MD, et al. Epigenetics of atherosclerosis: emerging mechanisms and methods. Trends Mol Med. 2017Apr;23(4):332–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Erbel R, Budoff M.. Improvement of cardiovascular risk prediction using coronary imaging: subclinical atherosclerosis: the memory of lifetime risk factor exposure. Eur Heart J. 2012May;33(10):1201–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Pirillo A, Norata GD, Catapano AL. LOX-1, OxLDL, and atherosclerosis. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:152786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Pandey D, Bhunia A, Oh YJ, et al. OxLDL triggers retrograde translocation of arginase2 in aortic endothelial cells via ROCK and mitochondrial processing peptidase. Circ Res. 2014Aug1;115(4):450–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Cianciolo G, Capelli I, Cappuccilli M, et al. Calcifying circulating cells: an uncharted area in the setting of vascular calcification in CKD patients. Clin Kidney J. 2016Apr;9(2):280–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cominacini L, Pasini AF, Garbin U, et al. Oxidized low density lipoprotein (ox-LDL) binding to ox-LDL receptor-1 in endothelial cells induces the activation of NF-kappaB through an increased production of intracellular reactive oxygen species. J Biol Chem. 2000Apr28;275(17):12633–12638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Tao J, Yang P, Xie L, et al. Gastrodin induces lysosomal biogenesis and autophagy to prevent the formation of foam cells via AMPK-FoxO1-TFEB signalling axis. J Cell Mol Med. 2021May10;25:5769–5781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ackers I, Szymanski C, Silver MJ, et al. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein induces WNT5A signaling activation in THP-1 derived macrophages and a human aortic vascular smooth muscle cell line. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2020;7:567837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Nan S, Wang Y, Xu C, et al. Interfering microRNA-410 attenuates atherosclerosis via the HDAC1/KLF5/IKBα/NF-κB axis. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 2021June4;24:646–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Guo X, Gao L, Wang Y, et al. Advances in long noncoding RNAs: identification, structure prediction and function annotation. Brief Funct Genomics. 2016Jan;15(1):38–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Josefs T, Boon RA. The long non-coding road to atherosclerosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2020Aug9;22(10):55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Leisegang MS, Fork C, Josipovic I, et al. Long noncoding RNA MANTIS facilitates endothelial angiogenic function. Circulation. 2017July4;136(1):65–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Liu Y, Zheng L, Wang Q, et al. Emerging roles and mechanisms of long noncoding RNAs in atherosclerosis. Int J Cardiol. 2017Feb1;228:570–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Man HJ, Marsden PA. LncRNAs and epigenetic regulation of vascular endothelium: genome positioning system and regulators of chromatin modifiers. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2019Apr;45:72–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zhang C, Ge S, Gong W, et al. LncRNA ANRIL acts as a modular scaffold of WDR5 and HDAC3 complexes and promotes alteration of the vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype. Cell Death Dis. 2020June8;11(6):435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wang M, Liu Y, Li C, et al. Long noncoding RNA OIP5-AS1 accelerates the ox-LDL mediated vascular endothelial cells apoptosis through targeting GSK-3β via recruiting EZH2. Am J Transl Res. 2019;11(3):1827–1834. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bian W, Jing X, Yang Z, et al. Downregulation of LncRNA NORAD promotes Ox-LDL-induced vascular endothelial cell injury and atherosclerosis. Aging (Albany NY). 2020Apr8;12(7):6385–6400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Jin XJ, Chen XJ, Zhang ZF, et al. Long noncoding RNA SNHG12 promotes the progression of cervical cancer via modulating miR-125b/STAT3 axis. J Cell Physiol. 2019May;234(5):6624–6632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Cheng G, Song Z, Liu Y, et al. Long noncoding RNA SNHG12 indicates the prognosis of prostate cancer and accelerates tumorigenesis via sponging miR-133b. J Cell Physiol. 2020Feb;235(2):1235–1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Zhang J, Yuan L, Zhang X, et al. Altered long non-coding RNA transcriptomic profiles in brain microvascular endothelium after cerebral ischemia. Exp Neurol. 2016Mar;277:162–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zhao M, Wang J, Xi X, et al. SNHG12 promotes angiogenesis following ischemic stroke via regulating miR-150/VEGF pathway. Neuroscience. 2018Oct15;390:231–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Cai M, Li X, Dong H, et al. CCR7 and its related molecules may be potential biomarkers of pulmonary arterial hypertension. FEBS Open Bio. 2021Feb25;11:1565–1578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Sun Y, Zhao JT, Chi BJ, et al. Long noncoding RNA SNHG12 promotes vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration via regulating miR-199a-5p/HIF-1α. Cell Biol Int. 2020Aug;44(8):1714–1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Song YX, Sun JX, Zhao JH, et al. Non-coding RNAs participate in the regulatory network of CLDN4 via ceRNA mediated miRNA evasion. Nat Commun. 2017Aug18;8(1):289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Frohlich J, Al-Sarraf A. Cardiovascular risk and atherosclerosis prevention. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2013Jan-Feb;22(1):16–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Steinberg D, Witztum JL. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein and atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010Dec;30(12):2311–2316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Valente AJ, Irimpen AM, Siebenlist U, et al. OxLDL induces endothelial dysfunction and death via TRAF3IP2: inhibition by HDL3 and AMPK activators. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014May;70:117–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hu WN, Duan ZY, Wang Q, et al. The suppression of ox-LDL-induced inflammatory response and apoptosis of HUVEC by lncRNA XIAT knockdown via regulating miR-30c-5p/PTEN axis. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2019Sept;23(17):7628–7638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Shan H, Guo D, Zhang S, et al. SNHG6 modulates oxidized low-density lipoprotein-induced endothelial cells injury through miR-135a-5p/ROCK in atherosclerosis. Cell Biosci. 2020;10:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- [30].Wang P, Ning S, Zhang Y, et al. Identification of lncRNA-associated competing triplets reveals global patterns and prognostic markers for cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015Apr20;43(7):3478–3489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Wang L, Qi Y, Wang Y, et al. LncRNA MALAT1 suppression protects endothelium against oxLDL-induced inflammation via inhibiting expression of MiR-181b target gene TOX. Oxid med cell longev. 2019;2019:8245810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Cao L, Zhang Z, Li Y, et al. LncRNA H19/miR-let-7 axis participates in the regulation of ox-LDL-induced endothelial cell injury via targeting periostin. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019July;72:496–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Zhang T, Beeharry MK, Wang Z, et al. YY1-modulated long non-coding RNA SNHG12 promotes gastric cancer metastasis by activating the miR-218-5p/YWHAZ axis. Int J Biol Sci. 2021;17(7):1629–1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Wang Y, Liang S, Yu Y, et al. Knockdown of SNHG12 suppresses tumor metastasis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition via the Slug/ZEB2 signaling pathway by targeting miR-218 in NSCLC. Oncol Lett. 2019Feb;17(2):2356–2364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Li X, He J, Shao M, et al. Downregulation of miR-218-5p promotes invasion of oral squamous cell carcinoma cells via activation of CD44-ROCK signaling. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018Oct;106:646–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Wang H, Zhan M, Xu SW, et al. miR-218-5p restores sensitivity to gemcitabine through PRKCE/MDR1 axis in gallbladder cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2017May11;8(5):e2770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Huang L, Ding Y, Yang L, et al. The effect of LncRNA SNHG16 on vascular smooth muscle cells in CHD by targeting miRNA-218-5p. Exp Mol Pathol. 2021Feb;118:104595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Yu SF, Feng WY, Chai SQ, et al. Down-regulation of miR-218-5p promotes apoptosis of human umbilical vein endothelial cells through regulating high-mobility group box-1 in Henoch-schonlein purpura. Am J Med Sci. 2018July;356(1):64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004Jan23;116(2):281–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Qiao XR, Wang L, Liu M, et al. MiR-210-3p attenuates lipid accumulation and inflammation in atherosclerosis by repressing IGF2. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2020Feb;84(2):321–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Wu X, Zheng X, Cheng J, et al. LncRNA TUG1 regulates proliferation and apoptosis by regulating miR-148b/IGF2 axis in ox-LDL-stimulated VSMC and HUVEC. Life Sci. 2020Feb15;243:117287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Yang N, Dong B, Song Y, et al. Downregulation of miR-637 promotes vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration via regulation of insulin-like growth factor-2. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2020;25:30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Li SF, Hu YW, Zhao JY, et al. Ox-LDL upregulates CRP expression through the IGF2 pathway in THP-1 macrophages. Inflammation. 2015Apr;38(2):576–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]