Our journal is twenty years old!

This is a landmark well worth celebrating. How did we come to this point? For many years, ASUM produced a newsletter every two months. In 1985, I became the editor and watched it grow in size and scope as medical ultrasound came to maturity. When I stepped down in 1997 and handed the reins to Prof. Robert Gibson, the decision was made to transform it into a journal. Assisted by Keith Henderson (ASUM's Education Officer), the journal was born, with its first issue being published in February 1998.

Since then it has become a full‐status peer‐reviewed journal, published by a major publisher (Wiley) and indexed in PubMed Central. A glance at any of the recent issues will tell you that this is a world‐class journal of which we can be proud.

Looking back on this history leads me to reflect on the early years of ultrasound and Australia's role in its development.

Building on advances made in ultrasound technology during World War Two, researchers in several countries began to explore the possibilities for using ultrasound in medicine. In 1958, Ian Donald, a Scottish obstetrician, published a key paper in the Lancet (Figure 1). This provided convincing evidence that diagnostic ultrasound was likely to be a valuable tool in obstetrics.

Figure 1.

Beginning of Ian Donald's Seminal Paper on Obstetric Ultrasound.

In the same year, the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) set up an Ultrasound Committee to regulate therapeutic ultrasound. At their suggestion, George Kossoff was employed by the Commonwealth Acoustic Laboratories (CAL) to investigate both therapeutic and diagnostic uses of ultrasound in medicine. In the following year, the NHMRC Committee met to review concerns about the potential hazards of X‐rays in pregnancy. They recommended that the research should focus on the use of ultrasound in obstetrics. Dr. William Garrett was appointed as a medical consultant to assist George, and work began.

Initially, George had worked on the ultrasonic treatment of Ménière's disease. He then investigated the safety of ultrasound exposure in pregnant mice using a commercial ultrasound physiotherapy machine as the source.

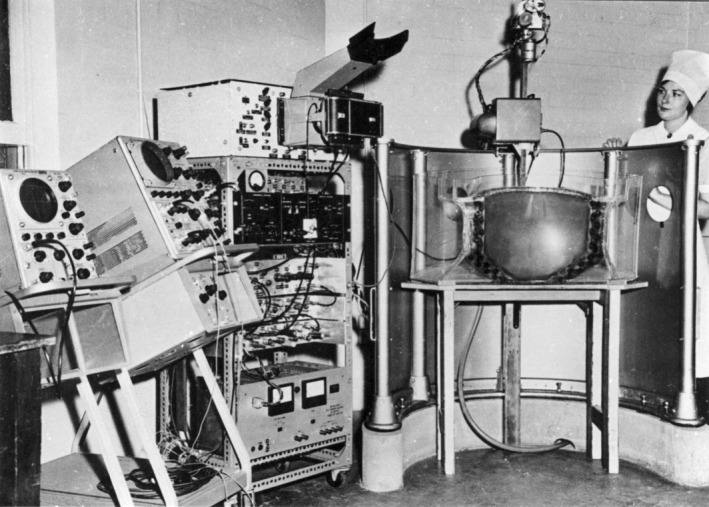

In 1960, David Robinson was hired to design and build an experimental water‐bath ultrasound scanner for obstetrics. This was installed at the Royal Hospital for Women (RHW) in Paddington, Sydney in 1962 (Figure 2). When the first images acquired by this machine were presented at a conference in the United States (Figure 3), they were acclaimed as being the equal of any other obstetric images, possibly the best in the world. Later, it was said that ‘the Australian group’ had provided an ‘existence proof’, showing what others could do with ultrasound once they caught up with them.

Figure 2.

Mark I Scanner Installed at the Royal Hospital for Women, Sydney in 1962.

Figure 3.

First Images Obtained by the Mark I Scanner.

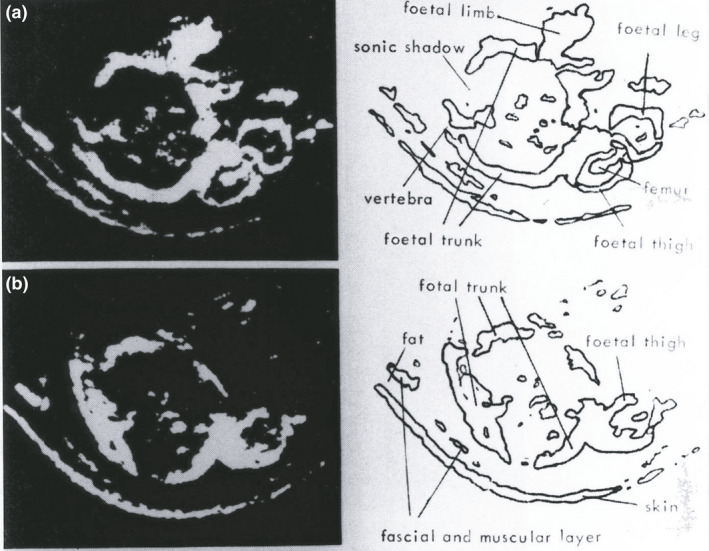

In the following years, the CAL Ultrasonics Group worked on improving the equipment. In parallel with this, Dr Garrett and his colleagues at RHW explored the clinical uses of ultrasound in obstetrics. Despite obvious challenges in interpreting these early images (Figure 4), they made steady progress and reported many new findings and observations at international conferences and through publications. Dr. Garrett and David Robinson also published one of the first obstetric ultrasound textbooks (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

A ‘State of the Art’ Image in 1964.

Figure 5.

Textbook Written by Dr William Garrett and David Robinson.

Following the initial success of the RHW machine, applications in other clinical areas were explored. An ophthalmic ultrasound machine was designed and installed at Sydney's Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in 1964 in collaboration with Dr. Herbert Hughes (Figure 6). The equipment was refined, and a regular service was offered for some years. A breast machine was developed and installed at Sydney's Royal North Shore Hospital in 1966 in collaboration with Prof. Tom Reeve (Figure 7). Again, the equipment continued to be refined, and a regular service was established and ran for several years. Cardiac ultrasound was investigated in collaboration with Dr. David Wilcken at Sydney's Royal Prince Henry Hospital.

Figure 6.

(a) Mark I Eye Scanner at the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney in 1964. (b) Early Clinical Image.

Figure 7.

(a) Mark I breast scanner at the Royal North Shore Hospital, Sydney in 1966. (b) Early Clinical Image.

As the years passed, more engineers and technical staff were employed, and so the Ultrasonics Group grew (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Ultrasonics Group Staff in 1979.

Perhaps, the single most important engineering contribution made by the group was the development of greyscale ultrasound in 1969. Until then, ultrasound images had been ‘bistable’ (i.e. black‐and‐white), showing tissue interfaces but not soft tissue parenchyma. Greyscale ultrasound compressed the range of echo amplitudes to allow the full range to be displayed on the screen (Figure 9). Greyscale technology spread around the world, dramatically improving the quality of ultrasound images. This, together with the development of real‐time scanning, led to an explosion in the use of ultrasound beginning in the early 1970s.

Figure 9.

(a) Comparison of Bistable and Greyscale Images of the Breast, 1969. (b) Typical Obstetric Image from a Commercial Machine, 1970.

To this point, the machines developed by the Ultrasonics Group used a water bath to couple ultrasound to the patient. This had advantages including the ability to use large transducers to provide sharp and more uniform focusing of the ultrasound beam and mechanised scanning. In contrast, commercial equipment generally involved placing the transducer on the patient and scanning by hand. The Ultrasonics Group (later to become the Ultrasonics Institute), therefore, developed a contact scanner for comparison with the water‐bath machines. This was installed at RHW in 1972, and it proved excellent for scanning babies’ heads (Figure 10). A comprehensive atlas of the neonatal brain was developed and published.

Figure 10.

(a) Contact Scanner at the Royal Hospital for Women, Sydney, 1972. (b) Typical Fetal Brain Images.

As diagnostic ultrasound became more widely used several ‘early adopters’ around Australia joined the research effort in areas such as obstetrics and cardiology (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

The First Commercial Greyscale Machine in Australia. Dr Andrew Scott and Sue Hewlett Using a Picker Machine in 1975.

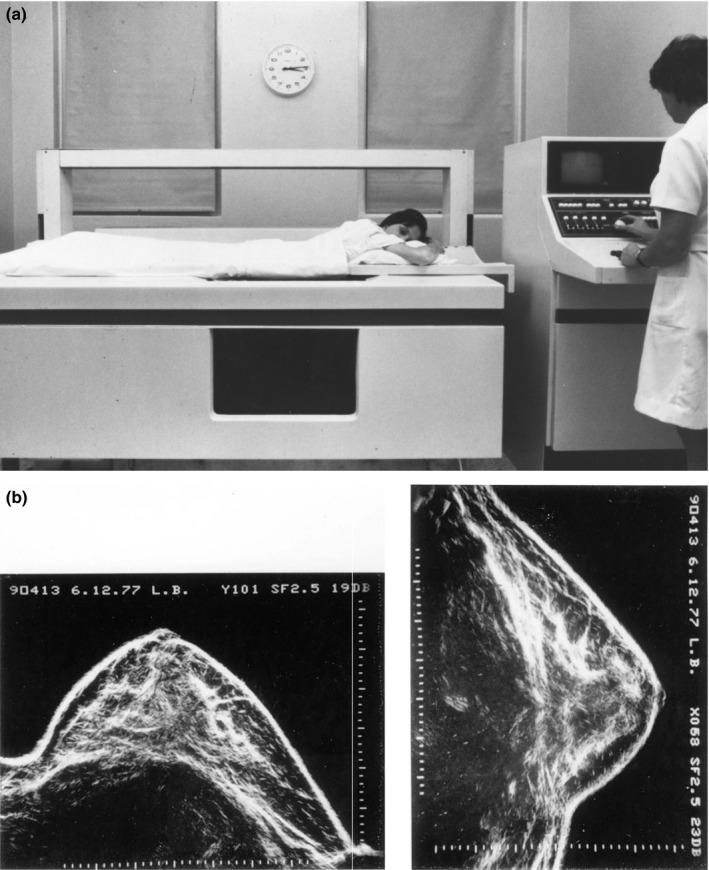

The successes of the Ultrasonics Group and its clinical collaborators led to pressure from the government and other potential users to produce a commercial machine. The UI Octoson was developed and commercialised by the Ausonics company. The machine consisted of a water tank containing eight mechanically scanned transducers. The patient laid on a flexible plastic membrane on top of the tank (Figure 12). Between 1976 and 1985, more than 200 Octosons were manufactured in Australia and sold worldwide. The technology then became obsolete with the widespread uptake of real‐time scanning.

Figure 12.

(a) Commercial UI Octoson. (b) Typical Octoson Breast Images.

The Ultrasonics Institute (UI) continued its research for another decade. Areas of research included array transducers, a proof‐of‐concept real‐time compound scanner, digital signal and image processing and Doppler (my own area).

The Institute also played an important role in education. An annual UI/RHW Course was established in 1974. In addition to teaching ‘bread‐and‐butter’ aspects of ultrasound, each course featured a leading overseas speaker. The aim was to bring new knowledge and techniques to Australia and to spread them as widely as possible. Many of the first generation of clinical ultrasound users in Australia attended this course over its 20 years of operation.

In 1989, the Ultrasonics Institute was transferred from the Commonwealth Department of Health to CSIRO. Its work continued for a few years but gradually the staff were integrated into other groups within CSIRO.

This marked the end of a wonderful era for those involved. We shared a sense of doing something that was challenging and worthwhile. Our work was performed in a highly cooperative spirit, and many great friendships resulted. The work of the Ultrasonics Institute was recognised in 2004 with the issue of a commemorative postage stamp as part of an ‘Australian Innovations’ series (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Commemorative Postage Stamp, 2004.

The early history of ASUM parallels that of the Ultrasonics Institute. ASUM was created in 1970 by staff members of the Ultrasonics Group and their clinical collaborators. Some of these individuals played a significant role in ASUM for many years.

Just as the journal has evolved, we have seen ASUM change. In its early days, it was just a small band of enthusiasts. Today, it is a highly respected professional society with extensive educational, scientific and professional programs.

I am sure we all look forward to seeing how ASUM and its Journal will evolve over the next 20 years.

If this story has piqued your interest, more detail and some references can be found by clicking on the “About Us” link of the ASUM website and selecting “History”.