Abstract

Objectives

This systematic review aims to summarize rates of adverse events (AEs) in patients with RA or inflammatory arthritis starting MTX as monotherapy or in combination with other csDMARDs, and to identify reported predictors of AEs.

Methods

Three databases were searched for studies reporting AEs in MTX-naïve patients with RA. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational cohort studies were included. Prevalence rates of AEs were pooled using random effects meta-analysis, stratified by study design.

Results

Forty-six articles (34 RCTs and 12 observational studies) were identified. The pooled prevalence of total AEs was 80.1% in RCTs (95% CI: 73.5, 85.9), compared with 23.1% in observational studies (95% CI: 12.3, 36.0). The pooled prevalence of serious AEs was 9.5% in RCTs (95% CI: 7.4, 11.7), and 2.1% in observational studies (95% CI: 1.0, 3.4). MTX discontinuation due to AEs was higher in observational studies (15.5%, 95% CI: 9.6, 22.3) compared with RCTs (6.7%, 95% CI: 4.7, 8.9). Gastrointestinal events were the most commonly reported AEs (pooled prevalence: 32.7%, 95% CI: 18.5, 48.7). Five studies examined predictors of AEs. RF status, BMI and HAQ score were associated with MTX discontinuation due to AEs; ACPA negativity, smoking and elevated creatinine were associated with increased risk of elevated liver enzymes.

Conclusion

The review provides an up-to-date overview of the prevalence of AEs associated with MTX in patients with RA. The findings should be communicated to patients to help them make informed choices prior to commencing MTX.

Keywords: rheumatoid arthritis, methotrexate, adverse event, pooled proportions, predictor

Rheumatology key messages

Gastrointestinal events are the most commonly reported AEs in patients with RA commencing MTX (32.7%).

The pooled prevalence of alopecia was low (6.3%), potentially reducing patients’ concerns when starting MTX.

Limited number of predictors have been examined to date, other possible predictors should be explored.

Introduction

In the last three decades, MTX has become the anchor treatment in the management of patients with RA, mainly due to its effectiveness in achieving clinical remission or low disease activity in a large proportion of patients [1, 2]. MTX is usually the conventional synthetic DMARD (csDMARD) of first choice for the treatment of newly diagnosed patients with RA, and is central to the recent treatment guidelines published by the EULAR and the ACR [3, 4].

MTX, as any treatment, is associated with a number of potential adverse events (AEs). These AEs range from mild (but often distressing for the patient) gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms to more serious events, such as pneumonitis. GI events, such as nausea, diarrhoea or abdominal pain were the most frequently occurring AEs (30.8%) in a systematic review published in 2009 about the long-term safety (>2-years follow-up) of MTX [5]. Moreover, GI AEs are one of the main reasons why a significant proportion of patients discontinue or stop adhering to MTX treatment. A study of 762 patients with RA found that GI events accounted for 32.7% of the AEs leading to MTX discontinuation [6]. In another study, nausea was reported in 74% of patients who were non-adherent to MTX due to AEs [7].

Liver enzyme abnormalities are also a common AE associated with MTX treatment, mainly elevated alanine transferase (ALT) and aspartate transferase (AST) enzymes, thus necessitating that all patients undergo regular blood tests [8]. In a review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing MTX to placebo, 15% of the patients who received MTX developed elevated liver enzymes compared with 3% in the placebo group [9]. Mucocutaneous AEs of MTX are diverse and include alopecia, skin rash, stomatitis or oral ulcers. Although alopecia is not common (6%), it can be a major concern affecting patients’ decision to start MTX therapy [9]. The reported prevalence of neurological AEs associated with MTX varied in previous reviews and ranged between 5.5% and 35% [5, 10]. Pulmonary AEs are not uncommon and range from a mild cough to more severe pneumonitis. Pneumonitis is a rare but severe idiosyncratic reaction that is documented in many studies, and usually occurs early after starting MTX therapy and is not related to the dose [11, 12].

To date, there have been many studies reporting on MTX-associated AEs; nevertheless, they have reported inconsistent results. Furthermore, previous reviews of the incidence and prevalence rates of AEs have been mainly limited to RCTs or have included both incident and prevalent MTX users. Therefore, a review compiling up-to-date incidence and prevalence rates of the AEs associated with starting MTX in patients with RA is needed.

In addition, identifying predictors of AEs can help individualize therapy, promote adherence, and subsequently improve effectiveness. Various demographic, clinical and drug-related factors have been examined as predictors of MTX-related AE occurrence, with folic acid supplementation among the most recognized factors [13, 14]. A review of RCTs of folate supplements vs placebo with MTX found a significant decline in the incidence of GI and hepatic AEs in the folate group, with relative risk (RR) of 0.74 (95% CI: 0.59, 0.92) and 0.23 (95% CI: 0.15, 0.34), respectively [15]. However, the evidence of association is not always conclusive or consistent across studies and therefore, uncertainty exists regarding the predictors of theses AEs. A few reviews have covered potential predictors of MTX-related AEs [16, 17], but there have been no recent systematic reviews bringing together the literature on predictors of AEs.

Therefore, this review aimed to (i) summarize the prevalence and incidence rates of AEs (i.e. total AEs, serious AEs, discontinuation due to AEs, GI, elevated liver enzymes, mucocutaneous, neurological and pulmonary AEs) in patients treated with MTX for RA and to (ii) identify the reported demographic, clinical and treatment related predictors of these AEs.

Methods

Search strategy

A systematic search of published literature was carried out using three electronic databases: Embase, Medline and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). A search strategy combining free text and MeSH terms was developed with the help of the centre librarian to identify relevant studies and implemented in the three databases (Supplementary Table S1, available at Rheumatology online). To capture the AEs rates in the current era, only manuscripts published from 1 January 2005 (allowing sufficient time for a study after the year 2000 to be completed and published) up to 12 February 2019 were included in this review. PRISMA reporting guidelines were followed in this systematic review [18]. Studies with multiple publications were reviewed to choose a representative report/s which included the outcomes of interest.

Both RCTs and longitudinal observational studies were included in this review. Only studies including adult (≥18 years old) patients with RA, inflammatory arthritis or undifferentiated arthritis were assessed. Studies examining genetic predictors, or the effect of natural products and supplements were excluded. Case reports, case series, reviews and conference abstracts were also excluded.

Patients had to be MTX-naïve before starting the study; retrospective studies were included if MTX treatment start date was defined and patients had not received MTX before the start date. Patients could have started MTX monotherapy or in combination with other csDMARDs or Corticosteroids (CSs), but not in combination with biologic DMARDs (bDMARDs) or targeted synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs). Only studies in English or translated into English were included.

Outcomes and data extraction

The outcomes of interest were the prevalence and incidence rates of the total of ‘any’ AEs, serious AEs, discontinuation of MTX due to AEs, elevated liver enzymes (including ALT and AST enzymes), GI, mucocutaneous, neurological and pulmonary AEs. The AE rates were only collected from the study arms with MTX monotherapy or MTX combined with GCs or csDMARDs, but not from other comparator arms. Some AEs were grouped together due to similarity, such as stomatitis and oral ulcers, and pneumonitis and interstitial lung disease (ILD).

The incidence rates of AEs were retrieved directly from studies reporting the rate in person-years. No attempts were made to estimate the incidence rates due to insufficient data on the number of events and attrition rate in most studies. The prevalence estimates were calculated as the number of patients who developed each AE divided by the study population at baseline; therefore, a patient could have more than one event during a study period but would only be counted once in the prevalence estimates.

For studies assessing predictors of MTX-related AEs, data on the possible predictors including the adjusted effect estimates and 95% CIs were retrieved from these studies.

Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias in individual studies was assessed using a checklist adapted from previously published tools [19, 20]. The checklist examined the risk of bias related to the review outcomes and was divided into three main domains for all studies (selection, attrition and outcome measurement). Additional assessment of analysis and reporting was performed for studies examining predictors of AEs. Publication bias across studies was examined graphically by funnel plots for total AEs, serious AEs and discontinuation of AEs in RCTs.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the included studies. Pooled prevalences of reported AEs were estimated using random effects meta-analysis and stratified by the study design (RCTs and observational studies). Where studies had several eligible MTX arms, the arms were combined (i.e., the number of AEs/baseline sample sizes were summed) and the study included only once in each meta-analysis. Freeman–Tukey double arcsine transformations were performed for all meta-analyses to stabilize the variance and to include prevalence estimates of 0 or 100% [21]. Overall and subgroup heterogeneity was quantified using the I2 statistics if more than three studies reported the AE. Meta-analyses were conducted using the metaprop package in Stata 14 (College Station, TX, USA) [22].

Results

A total of 5098 records (1529 found in Medline, 2168 in Embase and 1401 in CENTRAL) were identified. Of those, 1958 references were duplicates. Two authors (A.A.S., S.D.S.) screened 3140 titles and abstracts independently, and 2790 references were excluded for various reasons (Fig. 1). The full texts of 350 articles were then reviewed by the same two authors. Any discrepancies during screening were discussed between the two authors, disagreements were referred to a third author. Of the 350 full texts screened, 46 fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram capturing the different phases of the systematic review

AE: adverse event.

The 46 manuscripts comprised 34 clinical trials and 12 observational studies (Table 1). Twenty-two studies were based in Europe, nine in Asia, two in Australia, one in North America and 12 were multi-national studies. The total number of participants included was 10 122; the mean proportion of women was 73.3% and ranged between 53.4% and 86.1%. The mean reported follow-up duration of all studies was 16 months with an s.d. of 8 months [15 months for RCTs (s.d. = 8), 19 months for observational cohorts (s.d. = 8)].

Table 1.

Description of included studies including demographic and clinical characteristics of the study populations

| References | Country | Study design, setting |

Follow-up length | MTX arm (n) | Disease duration mean (s.d.) or median (IQR) |

Age, mean (s.d.) |

Female sex (%) | MTX starting dose (mg/week) | MTX dose mean (s.d.) (mg/week) | Comparator arm (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical trials | ||||||||||

| Stouten et al. [23] | Belgium | RCT Multicentre | 2 years | High risk patients: | 15 | NR | 5 MTX arms | |||

| MTX+SSZ+GCs (98) | 1.8 (3.1) weeks | 53.2 (11.9) | 64 (65) | |||||||

| MTX+GCs (98) | 2.6 ( 3.3) weeks | 51.8 ( 13.1) | 63 (64) | |||||||

| MTX+LEF+GCs (93) | 3.1 (6.4) weeks | 51.1 (12.8) | 64 (69) | |||||||

| Low risk patients: | 3.2 (6.6) weeks | 51.0 (14.0) | 38 (81) | |||||||

| MTX (47) | 1.9 (2.7) weeks | 51.4 (14.4) | 33 (77) | |||||||

| MTX+GCs (43) | ||||||||||

| Stamm et al.[24] | Austria | RCT | 2 years | MTX (36) | 9.4 (2.3) weeks | 52.9 (14.0) | 28 (78) | 10 | NR | IFX+MTX (38) |

| Multicentre | PBO (16) | |||||||||

| Atsumi et al.[25] | Japan |

RCT Multicentre |

2 years | MTX+PBO (157) | 4.3 (2.8) months | 49.0 (10.3) | 127 (81) | 8 | 11.5 (2.8 | CZP+MTX (159) |

| Emery et al.[26] | Multi-national | RCT | 1 year | MTX+PBO (213) | 2.9 (2.9) months | 51.2 (13.0) | 170 (80) | 10 | 22 mg at week 8 | CZP+MTX (655) |

| Multicentre | ||||||||||

| Bijlsma et al.[27] | The Netherlands | RCT | 2 years | MTX+PBO (108) | Median 27 (15–46) days | Median 53.5 (44.5–62) | 69 (64) | 10 | NR | TCZ+MTX (106) |

| Multicentre | TCZ+PBO (103) | |||||||||

| Burmester et al.[28] | Multi-national | RCT | 2 year | MTX+PBO (287) | 0.4 (0.48) years | 49.6 (13.1) | 229 (80) | 7.5 | 16.2 (6.2) at week 104 | TCZ+MTX (578) |

| Multicentre | TCZ+PBO (292) | |||||||||

| Scott et al.[29] | The UK | RCT | 2 years | MTX (75) | 0.14 (0.19 months | 54 (13.0) | 54 (72) | 7.5 | NR | Anakinra+MTX (79) |

| Multicentre | ||||||||||

| Emery et al.[30] | Multi-national | RCT | 1 year | MTX+PBO (116) | 0.50 (0.49 year | 49.1 (12.4) | 89 (77) | 7.5 | NR | ABA+MTX (119) |

| Multicentre | (+1 year no treatment) | ABA+PBO (116) | ||||||||

| Lee et al.[31] | Multi-national | RCT | 2 years | MTX+PBO (186) | 2.7 years | 48.8 (13.3) | 145 (78) | 10 | 18.5 mg at month 3 | TOF (770) |

| Multicentre | ||||||||||

| Nam et al.[32] | The UK | RCT | 78 weeks | MTX+IV GCs (57) | Median 6.9 (5–10) months | 52.9 (12.8) | 41 (72) | 10 | NR | IFX+MTX (55) |

| Multicentre | ||||||||||

| Nam et al.[33] | The UK | RCT | 78 weeks | MTX+PBO (55) | Median 8 (6–11) months | 48.4 (13.3) | 40 (73) | 10 | median 25 (20–25) | ETN+MTX (55) |

| Multicentre | ||||||||||

| Takeuchi et al.[34] | Japan | RCT | 26 weeks | MTX+PBO (163) | 0.3 (0.4) year | 54.0 (13.2) | 128 (76) | 4–6 | 6.6 (0.6 mg | ADA+MTX (171) |

| Multicentre | ||||||||||

| Chen et al.[35] | China | RCT | 24 weeks | MTX+PBO (132) | 32 (20) months | 47.7 (11.4) | 113 (86) | 10 | NR | Anbainuo (132) |

| Multicentre | Anabainuo+MTX (132) | |||||||||

| de Jong et al. [36] | The Netherlands | RCT | 3 months | MTX+SSZ+HCQ +IM GCs (91) | 162 (97) days | 53 (15) | 55 (60) | NR | 25 (1) | 3 MTX arms |

| Multicentre | MTX+SSZ+HCQ +oral GCs (93) | 184 (92) days | 54 (14) | 67 (72) | At week 3 | |||||

| MTX+oral GCs (97) | 154 (83) days | 54 (14) | 68 (70) | |||||||

| de Rotte et al.-a[37] | The Netherlands | RCT (de Jong 2013) | 9 months | MTX (285) | NR | 54 (14) | 199 (70) | NR | 25 (1) | Two cohorts combined |

| + Prospective cohort | MTX (102) | 52 (16) | 72 (71) | 15 (2) | ||||||

| Detert et al.[38] | Multi-national | RCT | 48 weeks | MTX+PBO (85) | 1.6 (1.7) months | 52.5 (14.3) | 57 (67) | 15b | 15 mg stable dose | ADA+MTX (87) |

| Multicentre | ||||||||||

| Kavanaugh et al.[39] | Multi-national | RCT | 26 weeks | MTX+PBO (517) | 4.5 (7.2) months | 50.4 (13.6) | 382 (74) | 7.5 | NR | ADA+MTX (515) |

| Multicentre | ||||||||||

| Leirisalo-Repo et al.[40] | Finland | RCT | 2 years | PBO+MTX+SSZ | Median 4 (3–6) months | 46 (11) | 31 (63) | 10b | Median 20 (15– 25) | IFX+MTX+SSZ |

| Multicentre | +HCQ+GCs (49) | +HCQ+GCs (50) | ||||||||

| Bakker et al.[41] | The Netherlands | RCT | 2 years | MTX+PBO (119) | NR | 53 (13) | 72 (61) | 10b | NR | 2 MTX arms |

| Multicentre | MTX+oral GCs (117) | 53 (14) | 70 (60) | |||||||

| Hobl et al.[42] | Austria | RCT | 16 weeks | Standard MTX (10) | NR | 51 (15) | 7 (70) | 15 | NR | 2 MTX arms |

| Single centre | accelerated dose MTX (9) | 62 (7) | 7 (78) | 25 | ||||||

| Stohl et al.[43] | Multi-national | RCT | 1 year | MTX+PBO (207) | 1.2 years | 49.2 | 153 (74) | 7.5 | NR | OCR+MTX (398) |

| Multicentre | ||||||||||

| Wevers-de Boer et al.[44] | The Netherlands | Non-RCT (induction phase) | 4 months | MTX+oral GCs (610) | NR | NR | NR | 15 | NR | ADA+MTX |

| Multicentre | ||||||||||

| Tak et al.[45] | Multi-national | RCT | 1 year | MTX+PBO (249) | 0.9 (1.1) years | 48.1 (12.7) | 192 (77) | 7.5 | NR | RTX+MTX (499) |

| Multicentre | >18 at week 8 | |||||||||

| Verstappen et al.-a[46] | The Netherlands | RCT | 2 years | Intensive MTX (149) | NR | 54 (14) | 102 (69) | 7.5b | 16.1 (CI = 14.8–17.3) | 2 MTX arms |

| Multicentre | Standard MTX (140) | 52 (15) | 91 (65) | 14 (CI: 13.1–14.8) | ||||||

| Emery et al.[47] | Multi-national | RCT | 24 weeks | MTX+PBO (160) | 2.9 (4.8) years | 48.6 (12.9) | 134 (84) | 10 | 19.1 (2.73) at week 23 | GOL+MTX (477) |

| Multicentre | ||||||||||

| Westhovens et al.[48] | Multi-national | RCT | 1 year | MTX+PBO (253) | 6.7 (7.1) months | 49.7 (13.0) | 199 (79) | 7.5 | 19 (2.3) at year 1 | ABA+MTX (256) |

| Multicentre | ||||||||||

| Bejarano et al.[49] | The UK | RCT | 56 weeks | MTX+PBO (73) | 7.9 (5.4) months | 47 (9) | 39 (53) | 7.5 | NR | ADA+MTX (75) |

| Multicentre | ||||||||||

| Braun et al.[50] | Germany | RCT | 24 weeks | SC MTX (188) | median | median | 15b | NR | 2 MTX arms | |

| Multicentre | oral MTX (187) | 2.5 (range: 0–535) | 58 (20–75) | 149 (79) | ||||||

| 2.1 (range: 0–293) months | 59 (22–75) | 138 (74) | ||||||||

| Emery et al. [51] | Multi-national | RCT | 1 year | MTX+PBO (263) | 9.3 (SE = 0.4) months | 52.3 (SE = 0.8) | 191 (73) | 7.5 | Median 19.6 at week 8 | ETN+MTX (265) |

| Multicentre | ||||||||||

| Capell et al. [52] | The UK | RCT | 1 year | Median | 7.5 | Median | SSZ (55) | |||

| Multicentre | SSZ+MTX (56) | 1.9 year s | 56 (30–78) | 42 (75) | 12.5 (0–20) | |||||

| MTX (54) | 1.8 years | 53 (34–79) | 43(79) | 15 (0–20) | ||||||

| Breedveld et al.[53] | Multi-national | RCT | 2 years | MTX+PBO (257) | 0.8 (0.9 years | 52.0 (13.1) | 190 (74) | 7.5 | 16.9 | ADA+MTX (268) |

| Multicentre | ADA (274) | |||||||||

| Dirven et al.-a[54] | The Netherlands | RCT Multicentre | 5 years | MTX+ other DMARDs (498) | Median 24 (14–53) weeks | 54 (14) | 336 (68) | NR | NR | Combined arms of Goekoop- Ruiterman 2005 |

| Goekoop- Ruiterman et al.[55] | The Netherlands | RCT | 1 year | Median | NR | IFX+MTX (128) | ||||

| Multicentre | sequential monotherapy (126) | 23 (14–54) | 54 (13) | 86 (68) | 15 | |||||

| MTX step-up combination (121) | 26 (14–56) | 54 (13) | 86 (71) | 15 | ||||||

| MTX+SSZ+ GCs (133) | 23 (15–53) weeks | 55 (14) | 86 (65) | 7.5 | ||||||

| Ichikawa et al.[56] | Japan | RCT | 96 weeks | MTX (23) | 8.2 (4.8 | 52.7 (9.3) | 16 (70) | 4 | NR | Bucillamine (24) |

| Multicentre | MTX+bucillamine (24) | 10.6 (6.6) months | 49.1 (12.9) | 17 (71) | ||||||

| Observational studies | ||||||||||

| Bluett et al.-a[57] | The UK | Prospective cohort | At least 1-year | MTX (431) | Median 7 (4–12) months | Median 58 (48–68) | 272 (63) | 7.5–10 | NR | NA |

| Multicentre | ||||||||||

| Gaujoux-Viala et al.[58] | France | Prospective cohort | 2 years | Optimal MTX dose (76) | 8.8 (9.7) months | 44.5 (12.6) | 56 (74) | 14.9 (4.9) | 15.1 (4.4) | NA |

| Multicentre | Non-optimal MTX dose (212) | 7.7 (9.2) months | 50.3 (11.3) | 163 (77) | 11.2 (3.1) | 11.9 (3.1) at 6 months | ||||

| Takahashi et al.[59] | Japan | Prospective cohort | 76 weeks | MTX (79) | 2.2 (5.7) months | 56.7 (14.7) | 68 (86) | 8 | NR | NA |

| Multicentre | ||||||||||

| Cummins et al.[60] | Australia | Prospective cohort | Median = 2 years | MTX+SSZ +HCQ (119) | Median 6 (4–10.5) months | 52.8 (13.1) | 80 (67) | 10 | NR | NA |

| Single centre | ||||||||||

| Kudo-Tanaka et al.[61] | Japan | Prospective cohort | 1 year | MTX (29) | 156.8 (107.6) days | 57.9 (13.1) | 22 (76) | 4–10 | Median 6.3 (range: 4–10) | No MTX (19) |

| Multicentre | ||||||||||

| Schipper et al.[62] | The Netherlands | Prospective cohort | 1 year | MTX tight control (126) | Median 15 (8–26) weeks | 56 (13) | 78 (62) | 15 | NR | Usual care (126) |

| 25 mg target | ||||||||||

| Hider et al.-a[63] | The UK | Prospective cohort | at least | MTX (309) | NR | 59.3 (48.3–69) | 204 (66) | 7.5–10 | NR | NA |

| Multicentre | 2 years | 25 mg target | ||||||||

| Ideguchi et al.[64] | Japan | Retrospective cohort | 437 person-years | MTX (273) | 9.9 (10.6) years | 57.6 (11.4) | 229 (84) | mean 3.8 | 5.5 (1.9 mg | NA |

| Proudman et al.[65] | Australia | Prospective cohort | 3 years | MTX+SSZ+HCQ (61) | Median 12 (6–104) weeks | 56 (14) | 46 (76) | 10 | median 10 mg (0–15) | NA |

| Multicentre | ||||||||||

| Shoda et al.[66] | Japan | Prospective cohort | mean 39.7 (12.0) months | MTX (69) | NR | 61.0 (9.0) | 58 (84) | 2 | 7.2 (3.4) mg | NA |

| Single centre | ||||||||||

| Weaver et al.[67] | USA | Prospective cohort | 1 year | MTX (941) | 3.5 (7.1) years | 56.8 (14.0) | 705 (75) | median | median at 1 year | bDMARDs |

| Multicentre | MTX+HCQ (325) | 4.6 (6.9) years | 53.8 (14.5) | 260 (80) | 10 | 12.5 mg | ||||

| MTX+LEF (191) | 7.4 (8.4) years | 55.5 (12.6) | 145 (78) | 10 | 12.5 mg | |||||

| MTX+HCQ+SSZ (42) | 7.2 (7.5) years | 47.8 (13.9) | 33 (79) | 15 | 15 mg | |||||

| 12.5 | 15 mg | |||||||||

| Singal et al.[68] | India | Prospective cohort | 20 months | MTX+CQ (24) | 48 months | 38 | 18 (75) | NR | NR | NA |

| Single centre | ||||||||||

Studies that included predictors of adverse events;

Studies in patients used s.c. MTX or both oral and s.c. MTX.

ABA: abatacept;

ADA: adalimumab;

CQ: chloroqine;

CZP: certolizumab pegol;

ETN: etanercept;

FA: folic acid;

GC: glucocorticoids;

GOL: golimumab;

IFX: infliximab;

IQR: inter-quartile range;

NA: not applicable;

NR: not reported;

OCR: ocrelizumab;

PBO: placebo;

RCT: randomized clinical trial;

RTX: rituximab;

TCZ: tocilizumab;

TOF: tofacitinib.

The outcome-based risk of bias was moderate in 11 studies, low in 29 studies and unknown in five studies (Supplementary Table S2, available at Rheumatology online). Moderate risk of bias was graded to studies mainly because of issues related to selection or reporting bias.

Incidence and prevalence of AEs

Of the included studies, six reported IRs of total AEs with a mean of 412.4/100 person-years (95% CI: 275.4, 549.3) [25–28, 32, 33], whereas the mean IR of serious AEs from eight studies was 10.0/100 person-years (95% CI: 7.1, 12.9) [25–28, 32, 33, 44, 53]. The IR of MTX discontinuation due to AEs was only reported in two studies, with IRs of 10.6 and 6.5/100 person-years [26, 28].

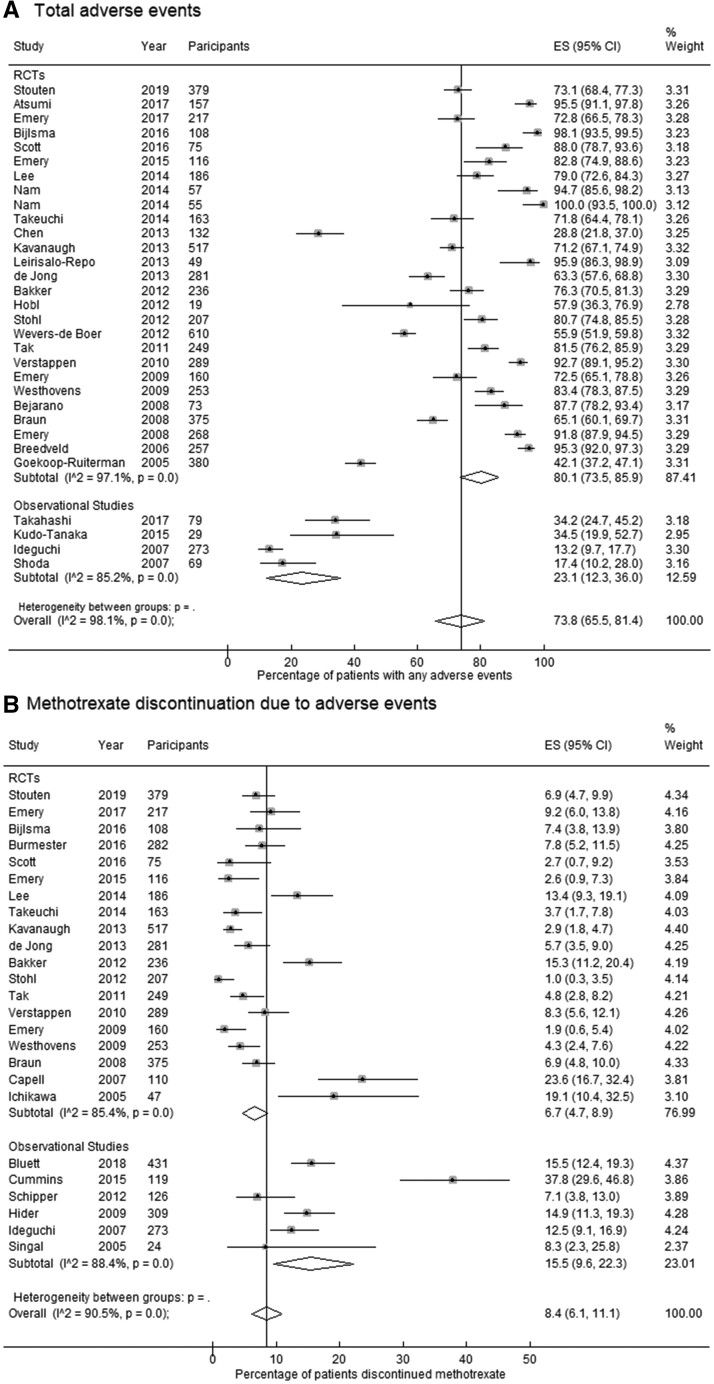

The pooled prevalence of total ‘any’ AEs in RCTs (80.1%; 95% CI: 73.5, 85.9) was more than two-fold the prevalence in observational studies (23.1%; 95% CI: 12.3, 36.0) (Table 2). In contrast, a greater proportion of patients discontinued MTX due to AEs in observational studies (15.5%; 95% CI: 9.6, 22.3) compared with RCTs (6.7%; 95% CI: 4.7, 8.9) (Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Pooled prevalence estimates of reported adverse events

| Type of AEs | Number of studies | Overall pooled prevalence (%, 95% CI) | Number of studies | RCTs pooled prevalence | Number of studies | Observational studies pooled prevalence (%, 95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (%, 95% CI) | |||||||

| Total ‘any’ AEs | 31 | 73.8 (65.5, 81.4) | 26 | 80.1 (73.5, 85.9) | 5 | 23.1 (12.3, 36.0) | |

| Serious AEs | 28 | 8.6 (6.6, 10.8) | 25 | 9.5 (7.4, 11.7) | 3 | 2.1 (1.0, 3.4) | |

| Discontinuation due to AEs | 25 | 8.4 (6.1, 11.1) | 19 | 6.7 (4.7, 8.9) | 6 | 15.5 (9.6, 22.3) | |

| Gastrointestinal | Any gastrointestinal event | 8 | 32.7 (18.5, 48.7) | 6 | 39.7 (22.2, 58.7) | 2 | 18.0 (11.1, 26.0) |

| Nausea | 20 | 19.0 (14.6, 23.9) | 19 | 19.2 (14.6, 24.1) | 1 | 16.7 (6.7, 35.9) | |

| Abdominal pain/ discomfort | 11 | 9.3 (5.5, 13.9) | 11 | 9.3 (5.5, 13.9) | 0 | NR | |

| Diarrhoea | 16 | 8.0 (5.8, 10.4) | 16 | 8.0 (5.8, 10.4) | 0 | NR | |

| Liver | Any elevated liver enzymea | 9 | 15.1 (10., 20.9) | 6 | 15.3 (9.3, 22.4) | 3 | 14.7 (5.5, 26.7) |

| Elevated ALT > 1× ULN | 13 | 8.9 (4.6, 14.3) | 13 | 8.9 (4.6, 14.3) | 0 | NR | |

| Elevated ALT > 2× ULN | 2 | 4.1 (2.4, 6.1) | 2 | 4.1 (2.4, 6.1) | 0 | NR | |

| Elevated AST > 1× ULN | 8 | 8.0 (2.8, 15.5) | 8 | 8.0 (2.8, 15.5) | 0 | NR | |

| Mucocutaneous | Any mucocutaneous event | 5 | 24.7 (9.8, 43.6) | 5 | 24.7 (9.8, 43.6) | 0 | NR |

| Alopecia | 10 | 6.3 (3., 9.4) | 9 | 6.9 (4.3, 10.1) | 1 | 1.3 (0.2, 6.8) | |

| Oral ulcer/stomatitis | 10 | 7.1 (2.9, 12.6) | 8 | 7.8 (3.1, 14.2) | 2 | 3.7 (0.0, 11.4) | |

| Neurological | Any neurological event | 4 | 24.7 (6.7, 48.9) | 4 | 24.7 (6.7, 48.9) | 0 | NR |

| Headache | 20 | 8.5 (6.1, 11.3) | 20 | 8.5 (6.1, 11.3) | 0 | NR | |

| Dizziness | 10 | 6.9 (3.5, 11.2) | 9 | 7.2 (3.6, 11.8) | 1 | 3.4 (0.6, 17.2) | |

| Pulmonary | Any pulmonary event | 4 | 30.7 (11.7, 53.8) | 4 | 30.7 (11.7, 53.8) | 0 | NR |

| Pneumonitis/ILD | 11 | 0.09 (0.0, 0.3) | 11 | 0.09 (0.0, 0.3) | 0 | NR | |

Elevated liver enzymes include any abnormal liver function above the ULN.

AE: adverse event;

ALT: alanine transaminase;

ILD: interstitial lung disease;

NR: not reported;

RCTs: randomized clinical trials;

ULN: upper limit of normal.

Fig. 2.

Forest plots for the pooled prevalence estimates of (A) total adverse events and (B) discontinuation of MTX due to adverse events

ES: estimated proportion/prevalence.

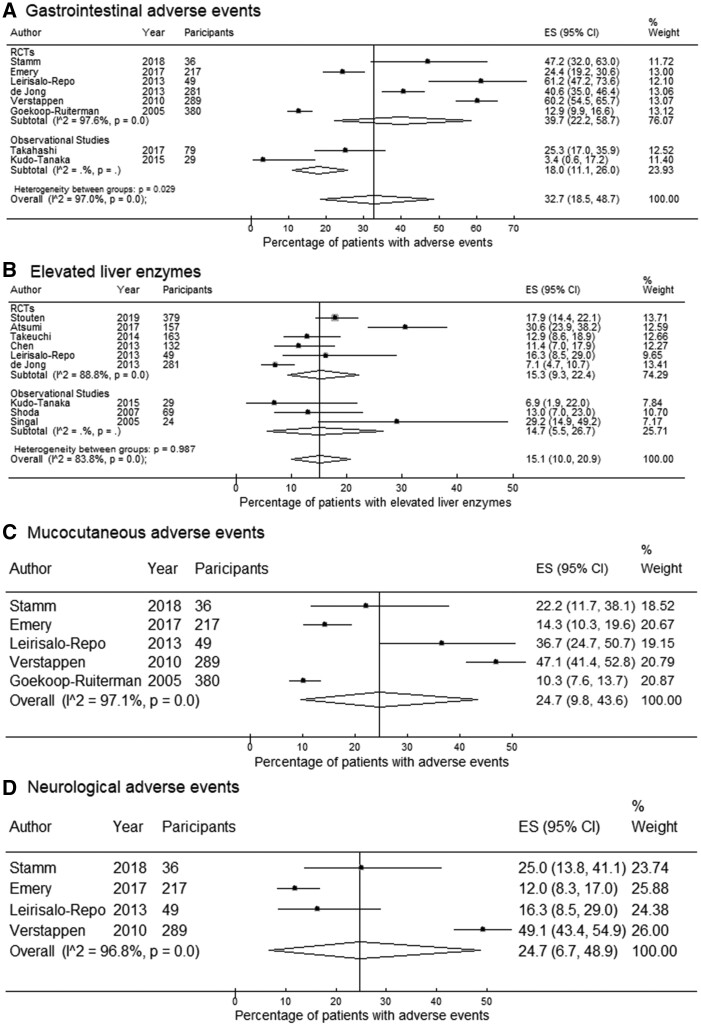

The pooled prevalence of any GI AEs from eight studies was 32.7% (95% CI: 18.5, 48.7) (Fig. 3). Nausea was the most commonly reported event of the GI system with a pooled prevalence of 19.0% (95% CI: 14.6, 24.1), followed by abdominal pain (9.3%; 95% CI: 5.5, 13.9) and diarrhoea (8.0%; 95% CI: 5.8, 10.4). With regard to liver AEs, the pooled prevalence was 15.1% (95% CI: 10.0, 20.9) for any elevated liver enzyme, and 8.9% (95% CI: 4.6, 14.3) for elevated ALT above the upper limit of normal (ULN), reported in 9 and 13 studies, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Forest plots for pooled prevalence estimates of (A) gastrointestinal adverse events (AEs), (B) elevated liver enzymes, (C) mucocutaneous AEs and (D) neurological AEs

The pooled prevalence of any mucocutaneous AEs estimated from five RCTs was 24.7% (95% CI: 9.8, 43.6). Alopecia and oral ulcers were reported in ten studies with a pooled prevalence of 6.3% (95% CI: 3.9, 9.4) and 7.1% (95% CI: 2.9, 12.6). The estimated prevalence of neurological AEs was 24.7% (95% CI: 6.7, 48.9) pooled from four RCTs. The pooled prevalence from four RCTs reporting pulmonary AEs was 30.7% (95% CI: 11.7, 53.8), but the pooled prevalence of pneumonitis/ILD was only 0.09% (95% CI: 0.0, 0.3) estimated from 11 RCTs. Funnel plots and additional forest plots are provided in the supplementary material (Supplementary Figs 1–16, available at Rheumatology online).

The findings on the prevalence of AEs were pooled from studies with MTX monotherapy and in combination with other csDMARDs. A sensitivity analysis for studies in which patients with RA started with MTX monotherapy did not show a meaningful change in the results (Supplementary Table S3, available at Rheumatology online). Note that many of these studies allowed adding or switching MTX to other DMARDs for inadequate response during the study period.

Predictors of AEs

A total of five studies (three RCTs and two observational studies) assessed possible predictors of AEs [37, 46, 54, 57, 63]. For the development of any AE, some of the examined predictors were associated with increased risk of AE occurrence but none of these predictors were statistically significant as shown in Table 3 [37, 46].

Table 3.

Baseline predictors of adverse events in included studies

| Adverse events | Possible predictor | Study | Effect size (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Development of AEs | Age | Verstappen et al. [46] | aOR=1.00 (0.97, 1.03) per year increase in age |

| Female sex | aOR=1.25 (0.49, 3.17) vs male sex | ||

| BMI | aOR =1.08 (0.95, 1.21) per unit increase in BMI | ||

| Swollen joint count | aOR=0.96 (0.89, 1.03) per number of swollen joint | ||

| Tender joint count | aOR=0.99 (0.93, 1.05) per number of tender joint | ||

| VAS pain | aOR=1.01 (0.99, 1.03) per unit mm increase | ||

| VAS general well-being | aOR=1.01 (0.99, 1.03) per unit mm increase | ||

| HAQ score | aOR=1.14 (0.54, 2.38) per unit increase in HAQ | ||

| RF positive | aOR=2.46 (0.77, 7.89) vs RF− | ||

| ESR | aOR=0.99 (0.97, 1.01) per mm/hour increase in ESR | ||

| Creatinine | aOR=1.01 (0.98, 1.04) per µmol/l increase in creatinine | ||

| Creatinine clearance | aOR= 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) per ml/min increase in clearance | ||

| AST | aOR=0.99 (0.94, 1.05) per U/l increase in AST | ||

| ALT | aOR=1.00 (0.97, 1.03) per U/l increase in AST | ||

| MTX-polyglutamate | de Rotte et al. [37] | OR=1.00 (0.99, 1.01) for total MTX-PG concentration after 3 months. In individual MTX-PGs 1–5, there were no significant association at 3, 6 and 9 months with AEs | |

| MTX discontinuation due to AEs | Female gender | Bluett et al. [57] | HR=1.39 (0.82, 2.35) vs male gender |

| RF positive | HR =0.37 (0.21, 0.64) vs RF− | ||

| HAQ score | HR=1.39 (0.98, 1.96) per unit increase in HAQ | ||

| Hider et al. [63] | at year 1: OR =1.87 (1.11, 3.15) per unit increase in HAQ | ||

| at year 2: OR=1.42 (0.89, 2.26) per unit increase in HAQ | |||

| BMI | Verstappen et al. [46] | OR =1.21 (1.02, 1.44) per unit increase in BMI | |

| Creatinine clearance | OR=0.97 (0.94, 1.00) per unit increase in creatinine clearance | ||

| Elevated ALT >2× ULN | Smoking | Dirven et al. [54] | OR =1.6 (0.98, 2.7) smokers vs non-smokers |

| ACPA positivity | OR =1.8 (1.1, 3.1) vs ACPA− | ||

| Baseline ALT >1 × ULN | OR =3.1 (1.6, 6.2) vs normal ALT at baseline | ||

| Age | aOR = 0.99 (0.98, 1.01) per year increase in age | ||

| Female gender | aOR=1.21 (0.73, 1.99) vs male gender | ||

| BMI | aOR=1.01 (0.95, 1.06) per unit increase in BMI | ||

| Alcohol | aOR=1.29 (0.81, 2.03) drinking alcohol compared to non-drinkers | ||

| Symptoms duration | aOR=1.00 (1.00, 1.00) per unit increase in duration | ||

| DAS | aOR=0.89 (0.68, 1.17) per unit increase in DAS score | ||

| HAQ | aOR=0.74 (0.52, 1.04) per unit increase in HAQ | ||

| RF positivity | b OR =1.68 (1.00, 2.81) vs RF− | ||

| ESR | aOR=1.00 (0.99, 1.01) per unit increase in ESR | ||

| Liver disease history | aOR=0.57 (0.07, 4.61) vs no history of liver disease | ||

| Elevated ALT >1× ULN | Age | Verstappen et al. [46] | OR=1.02 (0.99, 1.04) in I-group, OR=1.01 (0.98, 1.03) in C-group |

| Female sex | OR=1.16 (0.58, 2.35) in I-group, OR=0.60 (0.28, 1.29) in C-group | ||

| BMI | OR=1.08 (0.97, 1.21) in I-group, bOR =1.12 (1.00, 1.25) in C-group | ||

| Swollen joint count | OR=1.04 (0.99, 1.10) in I-group, OR=1.03 (0.96, 1.09) in C-group | ||

| Tender joint count | OR=1.02 (0.97, 1.07) in I-group, OR=1.00 (0.95, 1.06) in C-group | ||

| VAS pain | OR=1.00 (0.98, 1.01) in I-group, OR=1.00 (0.98, 1.01) in C-group | ||

| VAS general well-being | OR=1.00 (0.99, 1.02) in I-group, OR=1.01 (0.99, 1.03) in C-group | ||

| HAQ | OR=0.88 (0.51, 1.15) in I-group, OR=1.21 (0.67, 2.20) in C-group | ||

| RF positivity | OR=1.20 (0.58, 2.49) in I-group, OR=1.04 (0.46, 2.34) in C-group | ||

| ESR | OR=1.01 (1.00, 1.02) in I-group, OR=1.00 (0.99, 1.02) in C-group | ||

| Creatinine | OR=0.99 (0.97, 1.02) in I-group, bOR =1.03 (1.00, 1.07) in C-group | ||

| Baseline ALT | OR =1.03 (1.00, 1.06) in I-group, OR =1.08 (1.04, 1.12) in C-group |

Univariable regression analysis.

Effect size in bold is statistically significant.

Data on predictors of adverse events were retrieved directly from these studies without any amendments or attempt to combine the results.

ALT: alanine transferase;

AST: aspartate transferase;

AUC: area under concentration curve;

C-group: conventional strategy arm; HR: hazard ratio;

I-group: intensive strategy arm; MTX-glu3: MTX-polyglutamate 3;

MTX-PG: MTX polyglutamate;

OR: odds ratio;

ULN: upper limit of normal;

VAS: visual analogue scale.

Three studies examined predictors of MTX discontinuation due to AEs. In the Norfolk Arthritis Register (NOAR) observational study, Bluett et al. reported 67 discontinuations over 1608 person-years of follow-up. RF positivity was associated with lower risk of MTX discontinuation due to AEs [RF+: (HR)= 0.37 vs RF−, 95% CI: 0.21, 0.64)], whereas HAQ score and female gender were associated with increased risk of MTX discontinuation due to AEs (HAQ: HR= 1.39 per unit increase in HAQ, 95% CI: 0.98, 1.96; female gender: HR = 1.39 vs male gender, 95% CI: 0.82, 2.35) [57]. In another NOAR study (Hider et al.), 34 (11%) patients stopped MTX due to AEs in the first year, and 46 (15%) after 2 years of treatment. They also reported that a high baseline HAQ score (OR= 1.87 per unit increase in HAQ, 95% CI: 1.11, 3.15) was associated with increased risk of MTX discontinuation due to AEs after the first year of follow-up; however, the effect was not statistically significant at year two (OR= 1.42, 95% CI 0.89, 2.26) [63]. A third study by Verstappen et al. also examined predictors of MTX withdrawal due to AEs (24 discontinuations over 2 years). They reported that an increased BMI and decreased creatinine clearance were associated with higher risk of MTX discontinuation due to AEs (BMI: OR= 1.21 per unit increase in BMI, 95% CI: 1.02, 1.44; creatinine clearance: OR= 0.97 per unit increase in clearance, 95% CI: 0.94, 1.00) [46].

With regard to elevated liver enzymes, baseline ACPA positivity and high baseline ALT were associated with an increased risk of elevated ALT above two times ULN in the paper by Dirven et al. (ACPA+: OR= 1.8 vs ACPA−, 95% CI: 1.1, 3.1; baseline ALT >ULN: OR= 3.1 vs normal ALT, 95% CI: 1.6, 6.2) [54]. Higher BMI, creatinine and ALT at baseline were associated with increased risk of elevated ALT above ULN in the conventional treatment arm of the CAMERA-I study (BMI: OR= 1.12 per unit increase in BMI, 95% CI: 1.00, 1.25; creatinine: OR= 1.03 per unit increase in baseline creatinine, 95% CI: 1.00, 1.07; ALT: OR= 1.08 per unit increase in baseline ALT, 95% CI 1.04, 1.12) [46].

Discussion

This comprehensive systematic review summarizes the incidence rates and provides precise pooled prevalence estimates of AEs in patients with RA starting MTX for the first time. This review affirms previous studies that GI events are the most commonly reported MTX-related AEs, but in addition has shown that pulmonary, mucocutaneous and neurological events are also commonly reported. Furthermore, this review identified various baseline predictors of certain AEs, such as BMI, HAQ score, RF and ACPA.

The main objective of this review was to summarize the knowledge on the AEs associated with MTX, the most commonly used csDMARD for RA. Patients often worry about AEs related to their treatment, including MTX, and this could potentially affect their adherence to treatment [69, 70]. Patients report that they do not receive enough information regarding AEs from their rheumatologists [71], and the anxiety surrounding starting treatment might be lessened if patients had more information about the AEs associated with MTX. However, prior to this review, an extensive literature search would have been required by each rheumatologist to acquire the information necessary to inform patients about the potential AEs associated with MTX. This review offers valuable insight into the occurrence of MTX-related AEs, which can facilitate discussion between physicians and patients regarding any concerns prior to commencing MTX.

Although our review included studies with MTX-naïve patients in both RCTs and observational studies, prior reviews mainly including RCTs have reported comparable results. The pooled prevalence of elevated liver enzymes in this review was 15.1% compared with 15% in a previous review of RCTs of MTX treatment, and 20.2% in a review including non-RCTS with ≥2 years follow-up [5, 9]. Although liver enzyme abnormalities are not the most common AEs, it is usually a concern that requires frequent monitoring, and the treating physician often halts or discontinues MTX treatment if liver enzymes are elevated.

The pooled prevalence of oral ulcers and stomatitis was 7.1% in our review compared with 9% and 5.7%–8% in two other reviews of MTX monotherapy in RCTs [9, 72]. Lastly, the pooled prevalence of alopecia was 6.3% compared with 6% and 1%–4.9% in the aforementioned reviews. Although alopecia is one of the most worrying AE for people starting MTX, the low prevalence of this AE could be of some reassurance to patients.

Another important finding is the low prevalence of pneumonitis or ILD in the included studies (pooled estimate =0.09%). The prevalence was 0.43% in a previous review and an even higher incidence of pneumonitis was documented in an older literature review of retrospective studies published between 1970 and 2000 [5, 73]. This earlier review of observed high occurrence of MTX-pneumonitis could be due to refractory RA disease with pre-existing lung involvement [74], in addition, study design precludes drawing any conclusions on causation. Yet, pneumonitis remains a serious and threatening AE that requires monitoring and should be differentiated from other common pulmonary AEs such as mild chest pain and cough.

Although MTX treatment arms of RCTs were treated as observational studies in this review, there was significant variation in the pooled prevalence estimates of the AEs between RCTs and observational studies. For example, the pooled prevalence of total AEs was 80.1% in RCTs, while in observational studies the estimate was 23.1%. This could be explained by closer monitoring of AEs in RCTs and by higher adherence to therapy following stringent protocols. This is in contrast to what is observed for discontinuation of MTX due to AEs in which RCTs reported low withdrawal rates (pooled estimate: 6.7%), compared with observational studies (pooled estimate: 15.5%). The difference could also be attributed to stricter inclusion criteria in RCTs, or to the length of follow-up in the included studies, with observational studies having a relatively longer follow-up time (19 vs 15 months for RCTs).

Few studies examined potential predictors of the AEs in this review. Bluett et al. showed that RF positive patients had lower odds of discontinuing MTX due to AEs [57]. A plausible explanation for the association between RF positivity and withdrawal due to AEs might be explained by the variation in treatment response and disease activity. The same study reported that RF positivity and DAS-28 were associated with earlier discontinuation of MTX due to inefficacy, and that more patients stopped MTX due to inefficacy (33%) compared with AEs (16%). Thus, fewer patients with RF positivity and high DAS were included for the analysis of MTX withdrawal due to AEs. In addition, patients who are RF positive or with high HAQ score at baseline are less likely to have a good treatment response [75], thus may be less tolerant to AEs and more likely to stop MTX [76].

Dirven et al. [54] reported that ACPA and RF positive patients had higher odds of liver AEs. They also reported that high ALT at baseline was associated with increased risk of elevated ALT, conforming to the results in the CAMERA-I study. Higher ALT at baseline is an expected and a strong predictor for the enzyme elevation during subsequent follow-ups, which suggests pre-existing liver pathology or lower enzyme threshold before starting MTX. The two studies have examined multiple predictors of liver AEs, and showed contrasting results for RF status and BMI. Finding predictors of elevated liver enzymes could be of great benefit in clinical practice; patients at increased risk can be monitored more frequently than the recommended intervals by the 2015 ACR guidelines [4].

Overall, a limited number of predictors were identified. Although our risk of bias rating was low to moderate in most of the studies that examined predictors, they still had potential for bias. It is important to note the possible bias due to inadequate adjustment for confounders or selective reporting of results. Identification of these predictors of MTX AEs may help to optimize drug therapy in patients likely to experience these AEs early in the course of treatment. This also may lead to better treatment adherence, and subsequently improved effectiveness [7]. Furthermore, knowledge of risk factors of MTX AEs may guide physicians’ treatment decisions, such as dosing of MTX, frequency of monitoring or stopping MTX therapy.

A key strength of this review was not excluding studies with MTX in combination with other csDMARDs or GCs. This comes close to the variation seen in clinical practice as MTX could be started alone, or in combination with other csDMARDs and GCs [77]. However, the inclusion of combination therapy could lead to a higher level of heterogeneity among studies. These treatments also share many of the AEs of MTX safety profile [78], which could result in overestimation of the prevalence rates of some AEs associated with MTX. Another strength is the inclusion of studies of MTX with both short and long-term follow-up, which ranged between 4 months and 5 years. Moreover, the current review included manuscripts published after 2005, to be representative of current clinical practice since the implementation of the treat-to-target strategy in the early 2000s.

One of the limitations of our review was the inability to perform a meta-analysis of IRs. Unfortunately, the lack of detailed data reported on attrition rates and number of events in some studies prevented pooling the IR of different AEs. Moreover, a few RCTs allowed switching from MTX to comparators, such as bDMARDs. This could affect the precision of the pooled prevalence of AEs. The inclusion of studies in which MTX was combined with other csDMARDs could also have affected the estimates of the outcome. An inevitable weakness of this review is the exclusion of elevated liver enzymes results from a few studies that do not fit with the presented categories. The variation in reporting and assessment is a common methodological challenge faced when reviewing certain outcomes such as AEs. Another issue that was not addressed in our review was accounting for duration of follow-up in the meta-analysis of AEs. The prevalence of AEs might vary in studies with short observation and exposure time compared with studies with longer observation; however, direct weighting of observation time is limited by the uncertainty regarding the relationship between time since MTX onset and risk of AEs.

In conclusion, the review provides a thorough and updated summary on AEs associated with MTX treatment in patients with RA. Furthermore, identified predictors of MTX-related AEs may help to optimize drug therapy in patients likely to experience these AEs early in the course of treatment, but the results of these predictors should be interpreted with caution and further research is required to investigate the predictors of AEs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mary Ingram, librarian at the Centre for Epidemiology Versus Arthritis, for help devising the search strategy and implementing the strategy in the databases. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the National Health Service, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health.

Funding: This work was supported by Versus Arthritis (grant numbers 20385, 20380) and by the NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Centre. A.A.S. is funded by a PhD studentship from King Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia. J.M.G. is funded through an MRC Skills Development Fellowship.

Disclosure statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at Rheumatology online.

References

- 1.Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Barton A. et al. Rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2018;4:18001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weinblatt ME, Kaplan H, Germain BF. et al. Methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. A five-year prospective multicenter study. Arthritis Rheum 1994;37:1492–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smolen JS, Landewé R, Bijlsma J. et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2016 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:960–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh JA, Saag KG, Bridges SL Jr. et al. 2015 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Treatment of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2016;68:1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salliot C, van der Heijde D.. Long-term safety of methotrexate monotherapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature research. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1100–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nikiphorou E, Negoescu A, Fitzpatrick JD. et al. Indispensable or intolerable? Methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis: a retrospective review of discontinuation rates from a large UK cohort. Clin Rheumatol 2014;33:609–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hope HF, Hyrich KL, Anderson J. et al. The predictors of and reasons for non-adherence in an observational cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis commencing methotrexate. Rheumatology 2020;59:213–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kremer JM, Alarcón GS, Lightfoot RW Jr. et al. Methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1994;37:316–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopez-Olivo MA, Siddhanamatha HR, Shea B. et al. Methotrexate for treating rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;2014:CD000957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furst DE.The rational use of methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis and other rheumatic diseases. Rheumatology 1997;36:1196–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kremer JM, Alarcón GS, Weinblatt ME. et al. Clinical, laboratory, radiographic, and histopathologic features of methotrexate-associated lung injury in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. A multicenter study with literature review. Arthritis Rheum 1997;40:1829–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carroll GJ, Thomas R, Phatouros CC. et al. Incidence, prevalence and possible risk factors for pneumonitis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate. J Rheumatol 1994;21:51–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Ede AE, Laan RFJM, Rood MJ. et al. Effect of folic or folinic acid supplementation on the toxicity and efficacy of methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis: a forty-eight–week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:1515–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morgan SL, Baggott JE, Vaughn WH. et al. Supplementation with folic acid during methotrexate therapy for rheumatoid arthritis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 1994;121:833–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shea B, Swinden MV, Tanjong Ghogomu E. et al. Folic acid and folinic acid for reducing side effects in patients receiving methotrexate for rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;2013:CD000951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Verstappen SMM, Owen SA, Hyrich KL.. Prediction of response and adverse events to methotrexate treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Int J Clin Rheumtol 2012;7:559–67. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romão VC, Canhão H, Fonseca JE.. Old drugs, old problems: where do we stand in prediction of rheumatoid arthritis responsiveness to methotrexate and other synthetic DMARDs? BMC Med 2013;11:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayden JA, van der Windt DA, Cartwright JL, Côté P, Bombardier C.. Assessing bias in studies of prognostic factors. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:280–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faillie JL, Ferrer P, Gouverneur A. et al. A new risk of bias checklist applicable to randomized trials, observational studies, and systematic reviews was developed and validated to be used for systematic reviews focusing on drug adverse events. J Clin Epidemiol 2017;86:168–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freeman MF, Tukey JW.. Transformations related to the angular and the square root. Ann Math Stat 1950;21:607–11. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nyaga VN, Arbyn M, Aerts M.. Metaprop: a Stata command to perform meta-analysis of binomial data. Arch Public Health 2014;72:39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stouten V, Westhovens R, Pazmino S. et al. Effectiveness of different combinations of DMARDs and glucocorticoid bridging in early rheumatoid arthritis: two-year results of CareRA. Rheumatology 2019;58:2284–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stamm TA, Machold KP, Aletaha D. et al. Induction of sustained remission in early inflammatory arthritis with the combination of infliximab plus methotrexate: the DINORA trial. Arthritis Res Ther 2018;20:174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Atsumi T, Tanaka Y, Yamamoto K. et al. Clinical benefit of 1-year certolizumab pegol (CZP) add-on therapy to methotrexate treatment in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis was observed following CZP discontinuation: 2-year results of the C-OPERA study, a phase III randomised trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1348–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emery P, Bingham CO, Burmester GR. et al. Certolizumab pegol in combination with dose-optimised methotrexate in DMARD-naïve patients with early, active rheumatoid arthritis with poor prognostic factors: 1-year results from C-EARLY, a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:96–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bijlsma JWJ, Welsing PMJ, Woodworth TG. et al. Early rheumatoid arthritis treated with tocilizumab, methotrexate, or their combination (U-Act-Early): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, double-dummy, strategy trial. Lancet 2016;388:343–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Burmester GR, Rigby WF, Van Vollenhoven RF. et al. Tocilizumab combination therapy or monotherapy or methotrexate monotherapy in methotrexate-naive patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: 2-year clinical and radiographic results from the randomised, placebo-controlled FUNCTION trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:1279–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scott IC, Ibrahim F, Simpson G. et al. A randomised trial evaluating anakinra in early active rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2016;34:88–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Emery P, Burmester GR, Bykerk VP. et al. Evaluating drug-free remission with abatacept in early rheumatoid arthritis: results from the phase 3b, multicentre, randomised, active-controlled AVERT study of 24 months, with a 12-month, double-blind treatment period. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:19–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee EB, Fleischmann R, Hall S. et al. Tofacitinib versus methotrexate in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2014;370:2377–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nam JL, Villeneuve E, Hensor EM. et al. Remission induction comparing infliximab and high-dose intravenous steroid, followed by treat-to-target: a double-blind, randomised, controlled trial in new-onset, treatment-naive, rheumatoid arthritis (the IDEA study). Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nam JL, Villeneuve E, Hensor EMA. et al. A randomised controlled trial of etanercept and methotrexate to induce remission in early inflammatory arthritis: the EMPIRE trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1027–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takeuchi T, Yamanaka H, Ishiguro N. et al. Adalimumab, a human anti-TNF monoclonal antibody, outcome study for the prevention of joint damage in Japanese patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: the HOPEFUL 1 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:536–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen XX, Dai Q, Huang AB. et al. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind clinical trial of combination therapy with Anbainuo, a novel recombinant human TNFRII: fc fusion protein, plus methotrexate versus methotrexate alone or Anbainuo alone in Chinese patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 2013;32:99–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Jong PH, Hazes JM, Barendregt PJ. et al. Induction therapy with a combination of DMARDs is better than methotrexate monotherapy: first results of the tREACH trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:72–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Rotte MCFJ, den Boer E, de Jong PHP. et al. Methotrexate polyglutamates in erythrocytes are associated with lower disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:408–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Detert J, Bastian H, Listing J. et al. Induction therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate for 24 weeks followed by methotrexate monotherapy up to week 48 versus methotrexate therapy alone for DMARD-naive patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: HIT HARD, aninvestigator-initiated study. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:844–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kavanaugh A, Fleischmann RM, Emery P. et al. Clinical, functional and radiographic consequences of achieving stable low disease activity and remission with adalimumab plus methotrexate or methotrexate alone in early rheumatoid arthritis: 26-week results from the randomised, controlled OPTIMA study. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:64–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leirisalo-Repo M, Kautiainen H, Laasonen L. et al. Infliximab for 6 months added on combination therapy in early rheumatoid arthritis: 2-Year results from an investigator-initiated, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study (the NEO-RACo Study). Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:851–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bakker MF, Jacobs JWG, Welsing PMJ. et al. Low-dose prednisone inclusion in a methotrexate-based, tight control strategy for early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2012;156:329–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hobl EL, Mader RM, Jilma B. et al. A randomized, double-blind, parallel, single-site pilot trial to compare two different starting doses of methotrexate in methotrexate-naïve adult patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Ther 2012;34:1195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stohl W, Gomez-Reino J, Olech E. et al. Safety and efficacy of ocrelizumab in combination with methotrexate in MTX-naive subjects with rheumatoid arthritis: the phase III FILM trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1289–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wevers-de Boer K, Visser K, Heimans L. et al. Remission induction therapy with methotrexate and prednisone in patients with early rheumatoid and undifferentiated arthritis (the IMPROVED study). Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1472–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tak PP, Rigby WF, Rubbert-Roth A. et al. Inhibition of joint damage and improved clinical outcomes with rituximab plus methotrexate in early active rheumatoid arthritis: the IMAGE trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Verstappen SM, Bakker MF, Heurkens AH. et al. Adverse events and factors associated with toxicity in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis treated with methotrexate tight control therapy: the CAMERA study. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:1044–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Emery P, Fleischmann RM, LW M, Hsia EC, Strusberg I. et al. Golimumab, a human anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody, injected subcutaneously every four weeks in methotrexate-naive patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: twenty-four-week results of a phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of golimumab before methotrexate as first-line therapy for early-onset rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:2272–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Westhovens R, Robles M, Ximenes AC. et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of abatacept in methotrexate-naive patients with early rheumatoid arthritis and poor prognostic factors. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1870–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bejarano V, Quinn M, Conaghan PG. et al. Effect of the early use of the anti-tumor necrosis factor adalimumab on the prevention of job loss in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:1467–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Braun J, Kästner P, Flaxenberg P. et al. Comparison of the clinical efficacy and safety of subcutaneous versus oral administration of methotrexate in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: results of a six-month, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, controlled, phase IV trial. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Emery P, Breedveld F C, Hall S. et al. Comparison of methotrexate monotherapy with a combination of methotrexate and etanercept in active, early, moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis (COMET): a randomised, double-blind, parallel treatment trial. Lancet 2008;372:375–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Capell HA, Madhok R, Porter DR. et al. Combination therapy with sulfasalazine and methotrexate is more effective than either drug alone in patients with rheumatoid arthritis with a suboptimal response to sulfasalazine: results from the double-blind placebo-controlled MASCOT study. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;66:235–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Breedveld FC, Weisman MH, Kavanaugh AF. et al. The PREMIER study: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind clinical trial of combination therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate versus methotrexate alone or adalimumab alone in patients with early, aggressive rheumatoid arthritis who had not had previous methotrexate treatment. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:26–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dirven L, Klarenbeek NB, van den Broek M. et al. Risk of alanine transferase (ALT) elevation in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with methotrexate in a DAS-steered strategy. Clin Rheumatol 2013;32:585–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goekoop-Ruiterman YP, de Vries-Bouwstra JK, Allaart CF. et al. Clinical and radiographic outcomes of four different treatment strategies in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis (the BeSt study): a randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:3381–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ichikawa Y, Saito T, Yamanaka H. et al. Therapeutic effects of the combination of methotrexate and bucillamine in early rheumatoid arthritis: a multicenter, double-blind, randomized controlled study. Mod Rheumatol 2005;15:323–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bluett J, Sergeant JC, MacGregor AJ, Chipping JR. et al. Risk factors for oral methotrexate failure in patients with inflammatory polyarthritis: results from a UK prospective cohort study. Arthritis Res Ther 2018;20:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gaujoux-Viala C, Rincheval N, Dougados M, Combe B, Fautrel B.. Optimal methotrexate dose is associated with better clinical outcomes than non-optimal dose in daily practice: results from the ESPOIR early arthritis cohort. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76:2054–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Takahashi C, Kaneko Y, Okano Y. et al. Association of erythrocyte methotrexate-polyglutamate levels with the efficacy and hepatotoxicity of methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a 76-week prospective study. RMD Open 2017;3:e000363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cummins L, Katikireddi VS, Shankaranarayana S. et al. Safety and retention of combination triple disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs in new-onset rheumatoid arthritis. Intern Med J 2015;45:1266–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kudo-Tanaka E, Shimizu T, Nii T. et al. Early therapeutic intervention with methotrexate prevents the development of rheumatoid arthritis in patients with recent-onset undifferentiated arthritis: a prospective cohort study. Mod Rheumatol 2015;25:831–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schipper LG, Vermeer M, Kuper HH, Hoekstra MO. et al. A tight control treatment strategy aiming for remission in early rheumatoid arthritis is more effective than usual care treatment in daily clinical practice: a study of two cohorts in the Dutch Rheumatoid Arthritis Monitoring registry. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:845–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hider SL, Silman AJ, Thomson W. et al. Can clinical factors at presentation be used to predict outcome of treatment with methotrexate in patients with early inflammatory polyarthritis? Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:57–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ideguchi H, Ohno S, Ishigatsubo Y.. Risk factors associated with the cumulative survival of low-dose methotrexate in 273 Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Rheumatol 2007;13:73–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Proudman SM, Keen HI, Stamp LK. et al. Response-driven combination therapy with conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs can achieve high response rates in early rheumatoid arthritis with minimal glucocorticoid and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2007;37:99–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shoda H, Inokuma S, Yajima N. et al. Higher maximal serum concentration of methotrexate predicts the incidence of adverse reactions in Japanese rheumatoid arthritis patients. Mod Rheumatol 2007;17:311–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Weaver AL, Lautzenheiser RL, Schiff MH. et al. Real-world effectiveness of select biologic and DMARD monotherapy and combination therapy in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: results from the RADIUS observational registry. Curr Med Res Opin 2006;22:185–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Singal VK, Chaturvedi VP, Brar KS.. Efficacy and toxicity profile of methotrexate chloroquine combination in treatment of active rheumatoid arthritis. Med J Armed Forces India 2005;61:29–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Palominos PE, Gasparin AA, de Andrade NPB. et al. Fears and beliefs of people living with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review. Adv Rheumatol 2018;58:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gadallah MA, Boulos DNK, Dewedar S, Gebrel A, Morisky DE.. Assessment of Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients’ Adherence to Treatment. Am J Med Sci 2015;349:151–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Connelly K, Segan J, Lu A. et al. Patients’ perceived health information needs in inflammatory arthritis: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2019;48:900–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lalani R, Lyu H, Vanni K, Solomon DH.. Low-dose methotrexate and mucocutaneous adverse events: results of a systematic literature review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthritis Care Res 2020;72:1140–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Barrera P, Laan RF, van Riel PL, Dekhuijzen PN. et al. Methotrexate-related pulmonary complications in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 1994;53:434–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Golden MR, Katz RS, Balk RA, Golden HE.. The relationship of preexisting lung disease to the development of methotrexate pneumonitis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 1995;22:1043–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Anderson JJ, Wells G, Verhoeven AC, Felson DT.. Factors predicting response to treatment in rheumatoid arthritis: the importance of disease duration. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:22–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Goodacre LJ, Goodacre JA.. Factors influencing the beliefs of patients with rheumatoid arthritis regarding disease-modifying medication. Rheumatology 2004;43:583–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jacobs JWG.Lessons for the use of non-biologic anchor treatments for rheumatoid arthritis in the era of biologic therapies. Rheumatology 2012;51:iv27–iv33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bijlsma J, Buttgereit F.. Adverse events of glucocorticoids during treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: lessons from cohort and registry studies. Rheumatology 2016;55:ii3–ii5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.