Abstract

Introduction

Patients with cancer are presumed a frail group at high risk of contracting coronavirus disease (COVID-19), and vaccination represents a cornerstone in addressing the COVID-19 pandemic. However, data on COVID-19 vaccination in cancer patients are fragmentary and poor.

Methods

An observational study was conducted to evaluate the seropositivity rate and safety of a two-dose regimen of the BNT162b2 or messenger RNA-1273 vaccine in adult patients with solid cancer undergoing active anticancer treatment or whose treatment had been terminated within 6 months of the start of the study. The control group was composed of healthy volunteers. Serum samples were evaluated for SARS-COV-2 antibodies before vaccinations and 2–6 weeks after the administration of the second vaccine dose. Primary end-point: seropositivity rate. Secondary end-points: safety, factors influencing seroconversion, IgG titers of patients versus healthy volunteers, COVID-19 infection.

Results

Between 20th March 2021 and 12th June 2021, 293 consecutive patients with cancer-solid tumours underwent a program of COVID-19 vaccinations; of these, 2 patients refused vaccination, 13 patients did not receive the second dose of the vaccine because of cancer progression, and 21 patients had COVID-19 antibodies at baseline and were excluded. The 257 evaluable patients had a median age of 65 years (range 28–86), 66.15% with metastatic disease. Primary end-point: seropositivity rate in patients was 75.88% versus 100% in the control group. Secondary end-points: no Grade 3–4 side-effects, no COVID-19 infections were reported. Patients median IgG titer was significantly lower than in the control group; male sex and active anticancer therapy influenced negative seroconversion.

BNT162b2 or messenger RNA-1273 vaccines were immunogenic in cancer patients, showing good safety profile.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-COV-2, Vaccine, Cancer patients, Anticancer treatment, Seroconversion, Antibodies

1. Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a highly infectious virus that has caused considerable discomfort and death worldwide. It has been reported that mortality from COVID-19 is higher in patients with cancer [[1], [2], [3]]. Most patients with cancer are elderly and have other comorbidities, such as hypertension, diabetes, coronary disease and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which are risk factors for severe disease and death [2,3]. Patients with cancer are at high risk of acquiring COVID-19 because of poor general condition and a systemic immunosuppressive state caused by cancer itself and/or anticancer treatment; in addition, cancer patients have frequently scheduled visits to hospitals and clinics that can increase their risk of catching COVID-19 [4]. As previously reported, patients with cancer have a markedly elevated risk of intubation, Intensive Care Unit (ICU) admission, and death, whether these patients are receiving active anticancer treatment or are cancer survivors [5].

We previously reported cases involving the first 25 patients with cancer-COVID-19 pneumonia in the Western world, and we found a mortality rate of 36.00% [2]. In addition, cases involving 51 patients with cancer-COVID-19 were reported by our group, and we found a COVID-19-related mortality rate of 23.53% [3]. Given the greater severity of COVID-19 in patients with cancer and their higher risk of death, patients with cancer are considered a high-priority subgroup for vaccination against COVID-19, and while vaccines against COVID-19 have shown high efficacy, immunocompromised patients were not included in controlled trials [6]. Limited data have been available on the efficacy, tolerability and safety of COVID-19 vaccines in patients with cancer because patients with cancer were excluded from clinical trials of COVID-19 vaccines [7]. It must be emphasised that the major organizations of Western countries, such as the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the Association of Cancer Research, and the Association of American Cancer Institute in the United States and the European Society of Medical Oncology, the Society of Immunotherapy and Cancer and the Italian Medical Oncology Association, in Europe recommended the vaccination of all patients with cancer, including those receiving active anticancer therapy [[8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13]].

Vaccines (BNT162b2 and messenger RNA [mRNA]-1273) were approved [14] and recommended by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency to prevent COVID-19 disease. BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 are lipid nanoparticle-encapsulated mRNA-based vaccines [14,15]. In Phase III trials, these vaccines had 94.00%–95.00% efficacy in preventing symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection independent of age [16,17]. Patients with cancer undergoing active treatment make frequent visits to hospitals or clinics, which can increase the risk of COVID-19 exposure so their prioritisation for vaccination is imperative [7]; however, there is a paucity of data on the efficacy and safety of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines in patients with cancer [[18], [19], [20], [21]]. In this study, we have reported preliminary findings evaluating the BNT162b2 (Pfizer-Biontech) and mRNA-1273 (Moderna) vaccines against COVID-19 in terms of their antibody-mediated response and tolerability in patients with cancer.

2. Material and methods

This observational study was conducted at the Oncology-Haematology Department of Piacenza General Hospital (North Italy) to investigate the immunogenicity of COVID-19 vaccines in a prospective study, which was approved by the local Ethics Committee (Institutional Review Board approval number 317/2021/OSS/ASLPC). COVID-19 vaccination was proposed to all patients with cancer attending the inpatient and outpatient clinic of the Oncology-Hematology Department Hospital of Piacenza, by oncologists and trained nurses. All patients gave signed informed consent. This study also included a control group of healthy volunteers who were ≥18 years undergoing anti-COVID-19 vaccination during the same period. Patients were vaccinated through national and regional Italian programs and vaccinated at the Oncology-Haematology Department of Piacenza General Hospital. All participants were given the two-dose regimen of the BNT162b2 mRNA vaccine (Pfizer-Biontech) or the mRNA-1273 vaccine (Moderna) via intramuscular injection in the deltoid muscle in accordance with the manufacturer's technical instructions.

2.1. Times of vaccination

The vaccine was administered to patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy 1–2 weeks before or 1–2 weeks after their drug dose. The vaccine was administered to patients treated with biological therapy (such as monoclonal antibodies and tyrosine kinase inhibitor), hormone therapy or immune checkpoint inhibitors when available as recommended [7]. For all patients with cancer undergoing anticancer treatment, a complete blood cell count was conducted before vaccination and vaccination was delayed until absolute neutrophil count recovery. Eligibility criteria for vaccination were as follows, patients with cancer-solid tumour, age ≥18 years, on active anticancer treatment or whose treatment had been terminated up to 6 months before the study period, with no known history of SARS-COV-2 infection or at least 3 months after testing positive for COVID-19. The blood serum of patients with cancer was tested to evaluate serum IgG antibody levels against SARS-COV-2 up to two days before vaccination (T0) and 2–6 weeks after the administration of the second vaccine dose. Exclusion criteria were as follows, active COVID-19 infection, patients with a baseline IgG value of ≥15 AU/ml were vaccinated but were excluded from this study.

2.2. End-points

The primary end-point was the proportion of patients who acquired anti-SARS-COV-2 antibodies after two doses of vaccination. The secondary endpoints were as follows:

-

•

Safety.

-

•

The role of age, gender, anticancer treatment, type and stage of cancer on vaccine seropositivity.

-

•

The diagnosis of symptomatic or asymptomatic post-vaccine COVID-19 infection.

-

•

Median IgG titer of patients versus healthy volunteers.

All vaccinated patients were followed and/or treated for their oncologic disease, and the COVID-19 swab test was performed in our department, as previously reported [22,23], for each patient attending the Oncology Clinic and this was repeated in asymptomatic patients every month.

2.3. Safety of the vaccine

All patients were informed to call specialised nurses of the Oncology Department to report any adverse events related to the vaccination, and they completed a questionnaire between 1, 2 and 4 weeks after the first and the second vaccination dose.

2.4. Serological assessment

Serum samples were analysed and evaluated for SARS-CoV-2 antibody with LIAISON SARS-CoV-2 S1–S2 IgG [24,25], performed in accordance with the manufacturer's technical instructions, which use an automated platform, LIAISON XL, for the detection of IgG against subunits S1 and S2 of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Results were calculated referring to a calibration curve and expressed in binding antibody units (AU)/ml; a value of ≥15 AU/ml was considered positive in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Patients were registered with a unique recognition code in a Microsoft Excel file (Microsoft Office version 2010). Quantitative variables were described by median and IQR, and qualitative variables were described by absolute and percentage frequencies. Normality was checked for all continuous variables. Comparisons of covariates were conducted using Pearson's X2 test or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and a t-test or Mann Whitney test for continuous variables. Univariable analysis was conducted using logistic regression to examine the association of each predictor variable with the response status of the patient. Next, significant variables (p < 0.05) were considered for inclusion in a multivariable regression model. For each risk factor, odds ratio with associated confidence intervals have been presented. All analyses were performed using RStudio version 3.6.0 statistical software with two-sided significance tests and a 5% significance level.

3. Results

In total, 293 consecutive oncology patients attending the Oncology/Hematology Department of the Piacenza General Hospital between 20th March 2021 and 12th June 2021 were included in the study. Of these, 2 patients refused vaccination, 13 patients did not receive the second dose of the vaccine because of cancer progression, and 21 patients had a baseline IgG value of ≥15 AU/ml and were excluded from the evaluation of their serologic response to vaccination. Thus, the final analysis included 257 consecutive evaluable patients who received two doses of the planned vaccines. Age was reported both as a continuous variable for the range < and ≥65 years. The median age was 65 (IQR 57–72) years, 56.03% of participants were female. Most patients (66.15%) were metastatic (Table 1 ), and the most common cancers were breast (27.24%) and gastrointestinal (26.07%; Table 2 ). Others included bladder, prostate, brain, melanoma, sarcomas and rare cancers. Overall, 219 patients (85.21%) were on active anticancer treatment (Table 3 ), and the most common anticancer treatment was chemotherapy alone (46.30%).

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics and anti-COVID-19 vaccination results.

| Variable | Patients n = 257 (100%) | Positive serologic response n = 195 (75.88%) | Negative serologic response n = 62 (24.12%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at time of vaccination median [IQR] (range) | 65 [57–72](28–86) | 64 [56–71](28–84) | 68 [61–73.75](41–86) | 0.03 |

| Age range | ||||

| <65 years n (%) | 122 (47.47) | 100 (81.97) | 22 (18.03) | 0.04 |

| ≥65 years n (%) | 135 (52.53) | 95 (70.37) | 40 (29.63) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female n (%) | 144 (56.03) | 118 (81.94) | 26 (18.06) | 0.02 |

| Male n (%) | 113 (43.97) | 77 (68.14) | 36 (31.86) | |

| Stage | ||||

| Non-metastatic n (%) | 87 (33.85) | 72 (82.76) | 15 (17.24) | 0.09 |

| Metastatic n (%) | 170 (66.15) | 123 (72.35) | 47 (27.65) | |

Bold values denote statistical significance at the p < 0.05 level.

Table 2.

Primary tumour location and anti-COVID-19 vaccination results.

| Primary Tumour Location | Patients n = 257 (100%) | Positive serologic response n = 195 (75.88%) | Negative serologic response n = 62 (24.12%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal n (%) | 67 (26.07) | 45 (67.16) | 22 (32.84) | 0.12 |

| Breast n (%) | 70 (27.24) | 59 (84.29) | 11 (15.71) | |

| Lung n (%) | 34 (13.23) | 23 (67.65) | 11 (32.35) | |

| Gynaecological n (%) | 25 (9.73) | 20 (80.00) | 5 (20.00) | |

| Other n (%) | 61 (23.74) | 48 (78.69) | 13 (21.31) |

Bold values denote statistical significance at the p < 0.05 level.

Table 3.

Patient's oncologic treatment and anti-COVID-19 vaccination results.

| Variable | Patients n = 257 (100%) | Positive serologic response n = 195 (75.88%) | Negative serologic response n = 62 (24.12%) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | ||||

| Chemotherapy n (%) | 119 (46.30) | 84 (70.59) | 35 (29.41) | 0.04 |

| Immunotherapy n (%) | 22 (8.56) | 15 (68.18) | 7 (31.82) | |

| Chemotherapy plus biological therapy n (%) | 32 (12.45) | 24 (75.00) | 8 (25.00) | |

| Chemotherapy plus immunotherapy n (%) | 13 (5.06) | 10 (76.92) | 3 (23.08) | |

| Biological therapy n (%) | 33 (12.84) | 26 (78.79) | 7 (21.21) | |

| No treatment n (%) | 38 (14.79) | 36 (94.74) | 2 (5.26) | |

| Line n (%) | ||||

| Neoadjuvant | 10 (4.44) | 7 (70.00) | 3 (30.00) | 0.35 |

| Adjuvant | 39 (17.33) | 33 (84.62) | 6 (15.38) | |

| I line | 122 (54.22) | 85 (69.67) | 37 (30.33) | |

| >I line | 54 (24.00) | 40 (74.07) | 14 (25.93) | |

Bold values denote statistical significance at the p < 0.05 level.

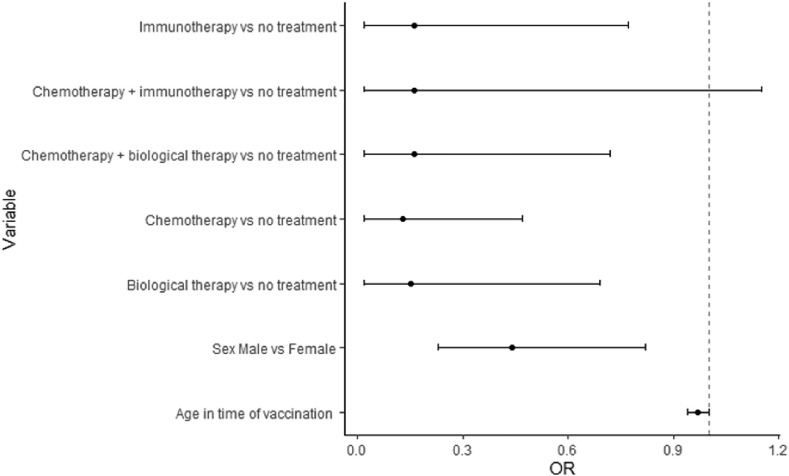

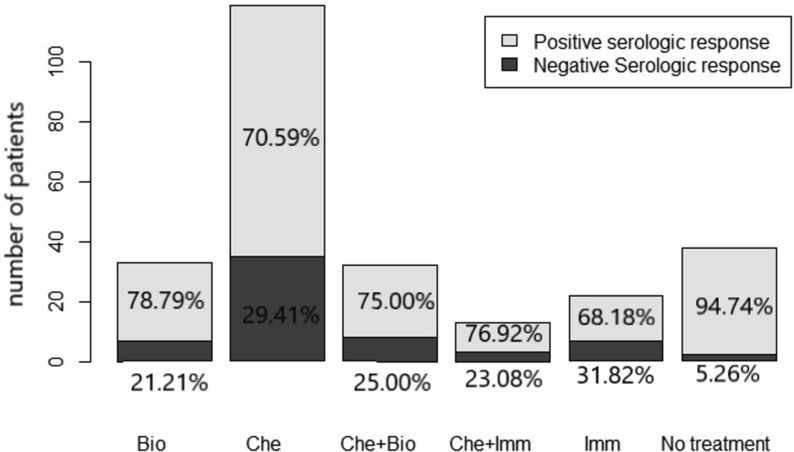

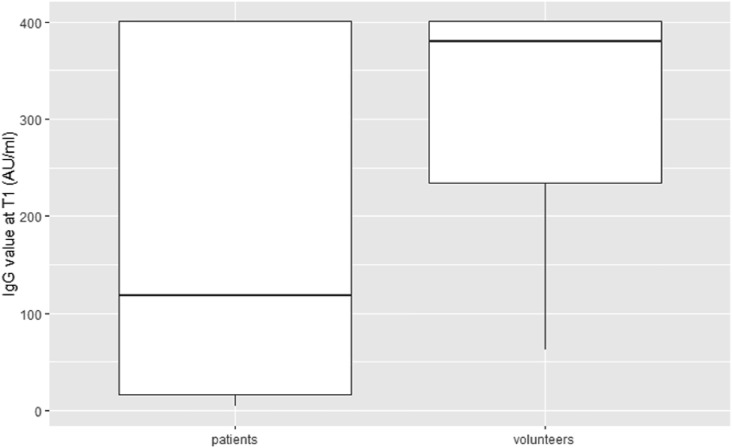

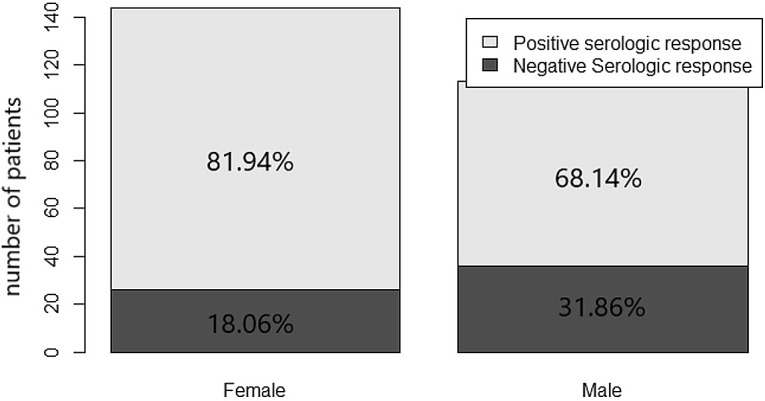

Primary end-point: after the second dose, 195/257 patients (75.88%) had an IgG value of ≥15 AU/ml, and 62/257 patients (24.12%) did not show a serologic response, while seropositivity in the control group was 100%. Secondary end-points: no grade 3 or 4 side effects were recorded. Overall, 31.52% and 33.46% of patients reported mild local reactions like pain and/or erythema at the site of vaccination after the first and second doses of the vaccine, respectively. The most frequently reported systemic reactions after the first dose of vaccine included weakness (7.00%), headache (8.17%), and muscle pain (2.72%). Systemic side effects more frequently reported after the second dose of vaccine were weakness (8.90%) and fever (5.83%). The results from the multivariable logistic regression (Table 4 ) showed that male sex and active treatment (chemotherapy, immunotherapy, biological therapy alone, and chemotherapy plus biological therapy) were risk factors for negative seroconversion. The year range was removed from the multivariable model due to collinearity with the variable age at the time of vaccination. Forest plots of odds ratio (95%CI) has been reported in Fig. 1 . Seroconversion according to sex has been reported in Fig. 2 , and seroconversion according to treatment has been reported in Fig. 3 . At short-term follow-up, no patients showed symptomatic or asymptomatic post-vaccine COVID-19 infection, regardless of seropositivity status. The median IgG titer in patients was statistically significantly lower than that in the control group (118 [IQR 16.9–401] AU/mL versus 380.5 [IQR 234–401] AU/mL, p < 0.001; Fig. 4 ).

Table 4.

Univariable and multivariable analysis of factors potentially associated with serologic response.

| Variable | Univariable analysis OR (95% CI) | p-value | Multivariable analysis OR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at the time of vaccination | 0.97 (0.94–1.00) | 0.03 | 0.97 (0.94–1.00) | 0.07 |

| Age range ≥65 years versus <65 years | 0.52 (0.29–0.94) | 0.03 | EX | |

| Sex male versus female | 0.47 (0.26–0.83) | 0.01 | 0.44 (0.23–0.82) | 0.01 |

| Metastatic versus non-metastatic | 0.54 (0.28–1.02) | 0.07 | NS | |

| Primary Tumour Location | ||||

| Gastrointestinal versus breast | 0.36 (0.14–0.84) | 0.02 | NS | |

| Lung versus breast | 0.36 (0.13–0.97) | 0.04 | ||

| Gynaecological versus breast | 0.59 (0.18–2.12) | 0.39 | ||

| Other versus breast | 0.76 (0.28–1.98) | 0.57 | ||

| Treatment | ||||

| Chemotherapy versus no treatment | 0.13 (0.02–0.47) | 0.01 | 0.13 (0.02–0.47) | 0.01 |

| Immunotherapy versus no treatment | 0.12 (0.02–0.56) | 0.01 | 0.16 (0.02–0.77) | 0.03 |

| Chemotherapy plus biological therapy versus no treatment | 0.17 (0.02–0.73) | 0.03 | 0.16 (0.02–0.72) | 0.03 |

| Chemotherapy plus immunotherapy versus no treatment | 0.19 (0.02–1.26) | 0.09 | 0.16 (0.02–1.15) | 0.07 |

| Biological therapy versus no treatment | 0.21 (0.03–0.94) | 0.06 | 0.15 (0.02–0.82) | 0.03 |

| Line | ||||

| Neoadjuvant versus > I line | 0.82 (0.20–4.19) | 0.79 | NS | |

| Adjuvant versus > I line | 1.93 (0.695.95) | 0.23 | ||

| I line versus > I line | 0.80 (0.38–1.63) | 0.55 | ||

Bold values denote statistical significance at the p < 0.05 level. (OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, NS not significant, EX excluded).

Fig. 1.

Forest plot of the multivariable impact of covariates on serologic response.

Fig. 2.

Serologic response based on sex.

Fig. 3.

Serologic response based on treatment (Bio: biological therapy, Che: chemotherapy, Imm: immunotherapy).

Fig. 4.

IgG value after the second dose of vaccine in patients and volunteers.

4. Discussion

People with cancer are at an increased risk of experiencing unfavourable outcomes resulting from COVID-19 infection, and recently published position papers, editorials, commentary and reviews have supported the notion that patients with cancer must receive COVID-19 vaccination when possible [26,27]. However, available clinical data on COVID-19 vaccination in patients with cancer are fragmentary and poor [[18], [19], [20], [21]]. To our knowledge, this article is one of the larger reports of a prospective, single-centre cohort study of anti-COVID-19 vaccination among patients with cancer in Europe. Many international guidelines do not recommend a specific timing of vaccination for patients in active treatment [7]; however, we chose to control neutrophil count, although this is not universally considered useful for vaccination, to guarantee greater safety to the patients. This cohort study showed that 195/257 (75.88%) patients with cancer were seropositive for SARS-COV-2 antibody IgG at 15–42 days after the second dose of BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273 vaccination versus 100% of the control group. It is now well-known that oncology patients have an increased risk of complications and mortality from COVID-19 [2,3,5,28], so they are considered a high priority subgroup of the population with regards to COVID-19 vaccination.

We are aware that the correlation between antibody response to anti-COVID-19 vaccines and protection against SARS-COV-2 infection has not been well-established in patients with cancer. However, in our cohort of vaccinated patients with cancer, despite the limitation of short-term follow-up, there was no symptomatic or symptomatic COVID-19 disease. As recently reported by our group, RT-PCR swabs taken from asymptomatic cancer patients attending the Outpatient Oncology Clinic, during the pre-vaccine era, were positive in 10/260 patients (3.85%) within a similar (two-months) period of observation [22]. Also in the group of patients with negative antibodies after vaccination (24.12%), no positive swab tests were recorded, which suggested a role of T-cell mediated immunity in patients with a poor humoral response.

Although the Centre for Disease Control and Prevention recommends against antibody testing for immunity assessment in response to mRNA COVID-19 vaccination [29], and cellular immunity plays an important role in protecting against COVID-19, recently published data have shown that seropositivity is associated with protection from infection [30,31]. A protective immune response to vaccines or viral infections is based on both humoral and cellular immune systems, and a good level of antibody response, as previously reported [32], can also indirectly represent T lymphocyte activity (T helper CD4+), which activates and stimulates B lymphocytes to produce antibodies against the antigen. In addition, the response of T helper lymphocytes CD4+ to the viral spike protein is correlated with the degree of anti-SARS-COV-2 IgG and IgA titers [33].

In our study cohort, most patients (75.88%) with cancer demonstrated seropositivity for SARS-COV-2 IgG antibodies, although this immunologic response was, as expected, inferior to seropositivity in the healthy control group (100%). The American Society of Infectious Disease recommends the vaccination of patients with cancer at the time of lowest immunosuppression [34]; according to this recommendation, our patients were vaccinated 1–2 weeks before the initiation of chemotherapy or 1–2 weeks before or after their chemotherapy drug dose, when white blood cells had recovered from chemotherapy. This optimised the potential for an immune response to the vaccine.

Data on anti-COVID-19 vaccination in patients with cancer are limited [[18], [19], [20], [21]]. Revon-Riviere et al. [19] reported a retrospective analysis of the safety and efficacy of BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccines in adolescents and young adult patients with solid tumours with a median age of 17 years. Of the 10 patients tested, nine patients had positive serology one month after the second injection, and vaccines had a good safety profile. Iacono et al. [20] evaluated the seroprevalence of SARS-COV-2 IgG in 36 older patients with cancer (age ≥80 years) after administering the second dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine and showed that older patients with cancer can have a serologic response to this anti-COVID-19 vaccine. Thakkar et al. [21] reported a high seroconversion rate (94%) in 200 patients with cancer in New York City who had received the full dose of an FDA-approved COVID-19 vaccine.

To our knowledge, only two single-centre prospective studies of mRNA vaccination for SARS-COV-2 among patients with cancer have been reported recently [18,35]. In the first study [18], researchers analysed 102 patients with cancer with a median age of 66 years (57% men) and showed that seropositivity for SARS-COV-2 anti-spike IgG antibodies after the second vaccine dose was 90%. This was higher than our study; however, in the previous study, pre-vaccination antibody titers were not evaluated. In the second study [35], 129 cancer patients, of which 70.5% patients were metastatic, vaccinated with BNT162b2 and monitored for antibody response and safety. The seropositivity rate among patients with cancer and control was 32.4% versus 59.8% (p < 0.0001) after the second dose, respectively. The seropositivity rate of this study is lower than the results of our study. In our study, before vaccination, 21 (7.16%) patients were found to have antibodies and excluded from our analysis. Our study was limited because of being performed at a single centre; in addition, we did not analyse cellular immunity and follow-up was short-term. We are evaluating booster vaccine doses in patients without seropositivity after two vaccine doses. As reported recently [[36], [37], [38], [39], [40]], there is a unanimous agreement that on the basis of the available evidence, for patients with cancer, as for the population at large, the benefit of the vaccination outweigh the risks. Given the greater severity and higher risk of death from COVID-19 in patients with cancer, vaccinating these patients should have a high priority, and we, as healthcare workers, need to make every possible effort to improve vaccination adherence by this group [40].

5. Conclusion

We conducted a prospective study of 257 consecutive evaluable patients, of which 219 (85.21%) patients were on active treatment. After two doses of the BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273 vaccine, the antibody response rate in these patients was 75.88% versus 100% in the healthy control group. Interestingly only 2 of 293 patients (0.68%) refused vaccination, this high adherence to the vaccine is likely due to finalised interviews with the patients. The vaccination was well-tolerated without Grade 3 or 4 adverse events. To our knowledge, this is the largest study of patients with cancer undergoing vaccination for SARS-COV-2 to date. Vaccination of cancer patients should be a priority, and patients in this study did not show signs of COVID-19 infection during vaccine follow-up. However, patients with cancer who have been vaccinated should continue to be prudent by wearing masks and engage in social distancing and hand hygiene practices. Patients, in this study, are being followed to evaluate the duration of immunological response and eventual COVID-19 infection.

Author statement

Luigi Cavanna: Conceptualisation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Roles/Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing; Chiara Citterio: Data curation, Formal analysis, Roles/Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing; Claudia Biasini: Data curation, Investigation, Writing - review & editing; Serena Madaro: Data curation, Investigation, Writing - review & editing; Nicoletta Bacchetta: Data curation, Writing - review & editing; Anna Lis: Data curation, Writing - review & editing; Gabriele Cremona: Data curation, Writing - review & editing; Monica Muroni: Data curation, Writing - review & editing; Patrizia Bernuzzi: Conceptualisation, Investigation, Writing - review & editing; Giuliana Lo Cascio: Writing - review & editing; Roberta Schiavo: Writing - review & editing; Martina Mutti: Writing - review & editing; Maristella Tassi: Writing - review & editing; Maria Mariano: Writing - review & editing; Serena Trubini: Writing - review & editing; Giulia Bandieramonte: Writing - review & editing; Raffaella Maestri: Investigation, Writing - review & editing; Patrizia Mordenti: Investigation, Writing - review & editing; Elisabetta Marazzi: Writing - review & editing. Daniele Vallisa: Investigation, Writing - review & editing.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Luigi Cavanna: Consulting or Advisory Role for AstraZeneca; Travel, Accommodations, Expenses from Pfizer, Ipsen And Celgene. Other authors: No Relationships to Disclose.

Acknowledgements

The authors dedicate this work to all the patients died because of COVID-19 in the district of Piacenza and their relatives. The authors thank all the patients afferent the Oncology/Hematology Department of the Piacenza General Hospital and their families.

References

- 1.Chamilos G., et al. Are all patients with cancer at heightened risk for severe Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)? Clin Infect Dis. 2021;72(2):351–356. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stroppa E.M., et al. Coronavirus Disease-2019 in cancer patients. A report of the first 25 cancer patients in a Western country (Italy) Future Oncol. 2020;16(20):1425–1432. doi: 10.2217/fon-2020-0369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cavanna L., et al. Cancer patients with COVID-19: a retrospective study of 51 patients in the district of Piacenza, Northern Italy. Future Sci OA. 2020;7(1) doi: 10.2144/fsoa-2020-0157. FSO645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El Saghir, NS. Oncology care and education during the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. ASCO Connect. http://www.lsmo-lb.org/news/caring-for-cancer-patients-during-the-covid-19-pandemic [Accessed 02 July 2021].

- 5.Liang W., et al. Cancer patients in SARS-CoV-2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(3):335–337. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30096-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shroff R.T., et al. Immune responses to COVID-19 mRNA vaccines in patients with solid tumours on active, immunosuppressive cancer therapy. medRxiv [Preprint] 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.05.13.21257129. 2021.05.13.21257129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desai A., et al. COVID-19 vaccine guidance for patients with cancer participating in oncology clinical trials. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18(5):313–319. doi: 10.1038/s41571-021-00487-z. Erratum in: Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021 Mar 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ribas A., et al. Priority COVID-19 vaccination for patients with cancer while vaccine supply is limited. Canc Discov. 2020;11:233–236. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-20-1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ong, MBH. Cancer groups urge CDC to prioritize cancer patients for COVID-19 vaccination. Canc Lett. https://cancerletter.com/articles/20210108_2/. [Accessed 17 Jun 2021].

- 10.Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer. SITC statement on SARS-CoV-2 vaccination and cancer immunotherapy. SIT Canc. https://www.sitcancer.org/aboutsitc/press-releases/2020/sitc-statement-sars-cov-2-vaccination-cancer-immunotherapy. [Accessed 11 Jun 2021].

- 11.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . NCCN; 2021. Preliminary recommendations of the NCCN COVID-19 vaccination advisory committee∗ version 1.0 1/22/2021.https://www.nccn.org/covid-19/pdf/COVID-19_Vaccination_Guidance_V1.0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garassino M.C., et al. The ESMO call to action on COVID-19 vaccinations and patients with cancer: Vaccinate. Monitor. Educate. Ann Oncol. 2021;32(5):579–581. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.01.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.AIOM CIPOMO COMU. Documento AIOM CIPOMO COMU Vaccinazione COVID-19 per i pazienti oncologici ver 1.0. https://www.aiom.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/20201231_Vaccino_COVID_19_AIOM_CIPOMO_COMU_1.0.pdf [Accessed 25 June 2021].

- 14.Walsh E.E., et al. Safety and immunogenicity of two RNA-based Covid-19 vaccine candidates. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(25):2439–2450. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2027906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jackson L.A., et al. An mRNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2-preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(20):1920–1931. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2022483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Polack F.P., et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(27):2603–2615. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2034577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baden L.R., et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(5):403–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Massarweh A., et al. Evaluation of seropositivity following BNT162b2 messenger RNA vaccination for SARS-CoV-2 in patients undergoing treatment for cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2021;28 doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.2155. e212155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Revon-Riviere G., et al. The BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in adolescents and young adults with cancer: a monocentric experience. Eur J Canc. 2021;154:30–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Iacono D., et al. Serological response to COVID-19 vaccination in patients with cancer older than 80 years. J Geriatr Oncol. 2021;S1879–4068(21) doi: 10.1016/j.jgo.2021.06.002. 00136-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thakkar A., et al. Seroconversion rates following COVID-19 vaccination among patients with cancer. Canc Cell. 2021;S1535–6108(21) doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.06.002. 00285-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cavanna L., et al. Prevalence of COVID-19 infection in asymptomatic cancer patients in a district with high prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in Italy. Cureus. 2021;13(3) doi: 10.7759/cureus.13774. e13774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim guidelines for collecting, handling, and testing clinical specimens from patients under investigation (PUIs) for 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) (www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/guidelines-clinical-specimens.html). [Accessed 17 June 2021].

- 24.Bonelli F., et al. Clinical and analytical performance of an automated serological test that identifies S1/S2-neutralizing IgG in COVID-19 patients semiquantitatively. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58(9) doi: 10.1128/JCM.01224-20. e01224-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DiaSorin. DiaSorin's LIAISON® SARS-CoV-2 diagnostic solutions. https://www.diasorin.com/en/immunodiagnostic-solutions/clinical-areas/infectious-diseases/covid-19. [Accessed 10 June 2021].

- 26.Saini K.S., et al. Emerging issues related to COVID-19 vaccination in patients with cancer. Oncol Ther. 2021;16:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s40487-021-00157-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mandal A., et al. Vaccination of cancer patients against COVID-19: towards the end of a dilemma. Med Oncol. 2021;38(8):92. doi: 10.1007/s12032-021-01540-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Desai A., et al. Mortality in hospitalized patients with cancer and coronavirus disease 2019: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Cancer. 2021;127(9):1459–1468. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Interim clinical considerations for use of COVID-19 vaccines. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-by-product/clinicalconsiderations.html. [Accessed 21 March 2021].

- 30.Harvey R.A., et al. Association of SARS-CoV-2 seropositive antibody test with risk of future infection. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(5):672–679. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.0366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jin P., et al. Immunological surrogate endpoints of COVID-2019 vaccines: the evidence we have versus the evidence we need. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):1–6. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00481-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Herishanu Y., et al. Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2021;137(23):3165–3173. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021011568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grifoni A., et al. Targets of T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus in humans with COVID-19 disease and unexposed individuals. Cell. 2020;181(7) doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.015. 1489–1501.e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rubin L.G., et al. 2013 IDSA clinical practice guideline for vaccination of the immunocompromised host. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(3):e44–e100. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shmueli E.S., et al. Efficacy and safety of BNT162b2 vaccination in solid cancer patients receiving anti-cancer therapy – a single center prospective study. Eur J Canc. 2021;8(157):124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Corti C., et al. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines for cancer patients: a call to action. Eur J Canc. 2021;148:316–327. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barrière J., et al. Current perspectives for SARS-CoV-2 vaccination efficacy improvement in patients with active treatment against cancer. Eur J Canc. 2021;154:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Di Noia V., et al. The first report on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccine refusal by patients with solid cancer in Italy: early data from a single-institute survey. Eur J Canc. 2021;153:260–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Curigliano G., et al. Adherence to COVID-19 vaccines in cancer patients: promote it and make it happen! Eur J Canc. 2021;153:257–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cavanna L., et al. Re: The first report on Covid-19 vaccine refusal by cancer patients in Italy: early data from a single-institute survey. Eur J Cancer. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.08.051. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]