Abstract

Incidence, molecular presentation and outcome of acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) are influenced by sex, but little attention has been directed at untangling sex‐related molecular and phenotypic differences between female and male patients. While increased incidence and poor risk are generally associated with a male phenotype, the poor prognostic FLT3 internal tandem duplication (FLT3‐ITD) mutation and co‐mutations with NPM1 and DNMT3A are overrepresented in female AML. Here, we have investigated the relationship between sex and FLT3‐ITD mutation status by comparing clinical data, mutational profiles, gene expression and ex vivo drug sensitivity in four cohorts: Beat AML, LAML‐TCGA and two independent HOVON/SAKK cohorts, comprising 1755 AML patients in total. We found prevalent sex‐associated molecular differences. Co‐occurrence of FLT3‐ITD, NPM1 and DNMT3A mutations was overrepresented in females, while males with FLT3‐ITDs were characterized by additional mutations in RNA splicing and epigenetic modifier genes. We observed diverging expression of multiple leukaemia‐associated genes as well as discrepant ex vivo drug responses, suggestive of discrete functional properties. Importantly, significant prognostication was observed only in female FLT3‐ITD‐mutated AML. Thus, we suggest optimization of FLT3‐ITD mutation status as a clinical tool in a sex‐adjusted manner and hypothesize that prognostication, prediction and development of therapeutic strategies in AML could be improved by including sex‐specific considerations.

Keywords: acute myeloid leukaemia, context‐dependency, FLT3, FLT3‐ITD, sex disparity

Internal tandem duplications (ITDs) in the FMS‐like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) gene are linked to poor prognosis in acute myeloid leukaemia (AML). Here, we investigated sex‐related differences in mutation, gene expression and drug sensitivity profiles in FLT3‐ITD‐mutated AML. We demonstrated significant sex‐associated molecular and functional differences, and surprisingly identified significant prognostication related to FLT3‐ITD only in female AML patients.

Abbreviations

- AML

acute myeloid leukaemia

- AR

allelic ratio

- AUC

area under the curve

- BM

bone marrow

- CE

capillary electrophoresis

- DGE

differential gene expression

- FLT3

Fms‐like tyrosine kinase 3

- ITD

internal tandem duplication

- MDS

myelodysplastic syndrome

- NGS

next‐generation sequencing

- VAF

variant allele frequency

1. Introduction

Sex influences regulatory mechanisms of the haematopoietic system as well as innate and adaptive immune responses [1, 2]. Strong age‐ and sex‐specific discrepancies in incidence of autoimmune conditions [3] and cancer [4], including haematological malignancies [5], suggest fundamental genetic and endocrine sex‐related variability.

Androgens have been used to treat various bone marrow (BM) failure syndromes since the 1960s [6], and the presence of hormone receptors on haematopoietic cells, including malignant cell populations, has been recognized for decades [7]. Yet, little is known about the molecular mechanisms modulating haematopoiesis through sex hormone pathways or their contribution in haematopoietic malignancies. It has been indicated that sex hormone receptors significantly contribute in regulation of haematopoietic cell subsets, including stem and progenitor cells [8]. Sex disparity in acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) incidence is known, with a progressive male excess with increasing age [9]. It has also been shown that male AML patients have significantly inferior outcomes compared to females, both in adult and in paediatric AML [10]. Sex‐specific mutational profiles in AML have also been described; FLT3‐ITD, NPM1 and DNMT3A mutations are overrepresented in females [11, 12], while mutations in RUNX1, ASXL1, SRSF2, STAG2, BCOR, U2AF1 and EZH2 are more prevalent in males [12]; and female overrepresentation among AML patients with co‐occurrence of DNMT3A, NPM1 and FLT3‐ITD mutations has also been reported [13].

Despite the demographic differences in survival and somatic mutation profiles, sex‐specific considerations are currently not made in therapeutic assessment or clinical risk stratification. Among the mutations with reported sex‐dependent discrepancies are internal tandem duplications (ITDs) of the FMS‐like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3). FLT3‐ITD is present in approximately 25% of the AML cases and is a negative prognostic marker that is integrated in standard risk stratification guidelines in AML as well as guiding FLT3‐targeted therapy [11, 14]. Yet, the association between sex and FLT3‐ITD mutations has not been explored in depth. Here, we present results from genomic, functional and time‐to‐event‐analyses of four well‐annotated cohorts, including the Beat AML cohort [15], the LAML‐TCGA cohort [16] and two independent HOVON/SAKK cohorts, in sum comprising 1755 AML patients. Cohort compositions with regard to sex and FLT3 mutation status are described in Table 1, and comparative analyses of sex differences related to clinical parameters are presented in Tables S1–S3.

Table 1.

Composition of all cohorts in relation to sex, age and FLT3 status.

| Beat AML | HOVON1 | HOVON2 | LAML‐TCGA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | ||||

| All | ||||

| Number | 496a | 432 | 625 | 200 |

| Median age (range) | 61 (2–87) | 46 (15–77) | 53 (18–65) | 57 (18–88) |

| Female | ||||

| Number | 222 | 215 | 273 | 92 |

| Median age (range) | 57.5 (2–85) | 46 (16–77) | 53 (19–65) | 57 (21–88) |

| Male | ||||

| Number | 276 | 217 | 352 | 108 |

| Median age (range) | 63 (5–87) | 46 (15–75) | 55 (18–65) | 58 (18–83) |

| ITD+ | ||||

| All | ||||

| Number | 123 | 117 | 146 | 39 |

| Median age (range) | 61 (10–85) | 47 (18–77) | 50 (18–65) | 57 (22–83) |

| Female | ||||

| Number | 62 | 67 | 74 | 18 |

| Median age (range) | 60 (22–79) | 45 (18–77) | 53 (19–65) | 58.5 (25–68) |

| Male | ||||

| Number | 61 | 50 | 72 | 21 |

| Median age (range) | 61 (10–85) | 47.5 (19–71) | 48.5 (18–65) | 57 (22–83) |

| ITD− | ||||

| All | ||||

| Number | 373 | 315 | 479 | 161 |

| Median age (range) | 62 (2–87) | 45 (15–75) | 55 (18–65) | 57 (18–88) |

| Female | ||||

| Number | 160 | 148 | 199 | 74 |

| Median age (range) | 55.5 (2–85) | 46 (16–74) | 52 (19–65) | 57 (21–88) |

| Male | ||||

| Number | 213 | 167 | 280 | 87 |

| Median age (range) | 64 (5–87) | 45 (15–75) | 65 (18–65) | 58 (18–81) |

The sample selection analysed from the Beat AML cohort comprises a total of 498 samples, but age for two of these samples is not annotated.

2. Methods

2.1. Patient sample selection

We analysed four independent patient cohorts: Beat AML, LAML‐TCGA, HOVON 1 and HOVON 2. The Beat AML and LAML‐TCGA cohorts were used for descriptive analyses of somatic variant profiles. The Beat AML cohort was further investigated by differential gene expression (DGE) analyses and exploration of ex vivo drug response profiles. All four cohorts were included for time‐to‐event analyses. Data from Beat AML [15] and LAML‐TCGA [16] are publicly available. All patients in the two HOVON cohorts provided written informed consent at trial inclusion.

The Beat AML sample cohort comprises 672 specimens from 562 individuals. We restricted our analysis to samples identified in the All.variants.csv file, downloaded from http://www.vizome.org/aml/geneset/ on the 01.11.2018. This included 608 samples from 519 individuals. At inclusion, 15 individuals had two samples acquired from different tissues. The sample with the lowest number of recurrent mutations was discarded. We filtered the remaining samples based on the variable ‘dxAtSpecimenAcquisition’ and retained samples annotated as ‘Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) and related precursor neoplasms’, resulting in a total of 571 samples. For descriptive analysis of somatic variants, we included only the first sample when serial samples were present, resulting in 498 samples from 498 individuals. For DGE and drug response, we analysed 390 samples from 360 individuals and 359 samples from 322 individuals, respectively, including only samples with sample IDs overlapping with the exome sequencing data set (Fig. S1A). For outcome assessment, we restricted the analysis to diagnostic samples, denoted ‘Initial Acute Leukemia Diagnosis’, where survival data was present, resulting in 303 individuals (Fig. S1B). Notably, we constructed an extended FLT3‐ITD annotation based on the combination of the consensus FLT3‐ITD variable from the clinical summary table (Table S5‐Clinical Summary) and Pindel call of FLT3‐ITDs, as reported in the All.variants.csv file.

The HOVON 1 and HOVON 2 cohorts comprise (non‐APL) newly diagnosed AML patients aged 15–80 years treated on various study protocols of the Dutch‐Belgian Hemato‐Oncology Cooperative Group (HOVON) and the Leukaemia Group of the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK) during the period 1987 to 2013. The sample selection analysed here was restricted to treatment naïve non‐APL AML patients with known FLT3‐ITD status. This includes patients treated in the protocols HO04, HO04a [17], HO29 [18, 19], HO42 [20, 21], HO43 [22] and HO102 [23]. The studies are previously published, and sampling and data acquisition were performed as previously described [24, 25]. Patients included in HO102 are referred to as HOVON2, while the remaining patients comprise HOVON1. Detailed information on the individual trials is available at http://www.hovon.nl.

LAML‐TCGA is a strongly selected sample cohort, composed to cover the major cytomorphologic and cytogenetic groups recognized in AML prior to 2013 [16]. The cohort comprises 200 de novo AML patients, including 92 females and 108 males ranging from 18 to 88 years. Due to its selective and unrepresentative composition, we have mainly used this cohort for integrated survival analyses. Single cohort comparative analyses of sex differences related to clinical parameters were not performed. The TCGA‐AML data analysis is based exclusively on variables as presented in the file ‘SuppTable01.xlsx’, downloaded from https://gdc.cancer.gov/node/876. For survival analysis, the variable ‘OS months 3.31.12’ is used.

2.2. Ethics

All clinical trials were approved by local ethics committees and performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.3. Statistics

For comparison of continuous variables, we applied the nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum test/Mann–Whitney test. The Fisher exact test was applied for comparison of categorical data. For DGE analysis, we log‐transformed the CPM matrix provided in ‘Table S9‐Gene Counts CPM’ by the formula: CPM(log2+0.1). Analyses were performed in accordance with the Linear Models for Microarray Data pipeline in the bioconductor r package (limma version 3.38.3) [26]. For exploration of the drug sensitivity data from the Beat AML cohort, we analysed the area under the curve (AUC) values provided in ‘Table S10‐Drug Responses’, applying categories from ‘Table S11‐Drug Families’. Time‐to‐event analyses were performed by generation of Kaplan–Meier survival curves and compared for differences using the log‐rank test. For continuous variables, impact on outcome was evaluated by univariate Cox models followed by multivariate logistic regression models. P‐values were adjusted by the Benjamini–Hochberg method, and threshold was set at P ≤ 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed in r‐studio (version 1.1.453) and r (version 3.5.0) (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Graphs were made with ggplot2 (version 3.1.0, https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org) [27] and figures made in Adobe illustrator CS6 (version 16.0.0. Adobe Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Comparative genomic architecture

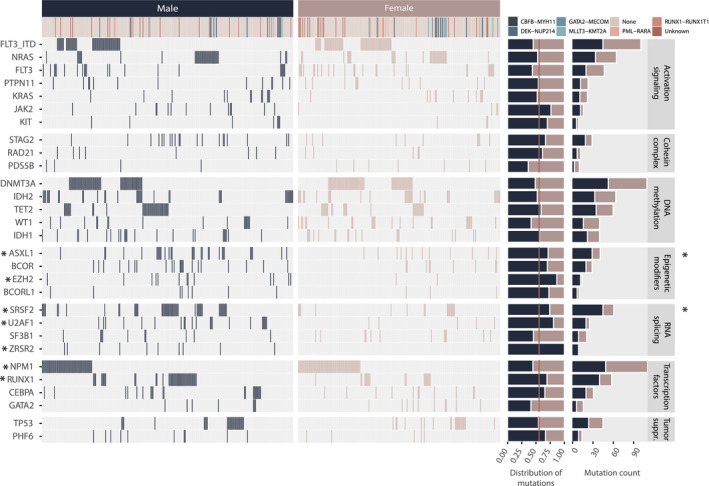

To provide a context for sex‐related variant patterns, we compared the sex‐related distribution of somatic variants annotated in the Beat AML cohort. We found that the number of somatic variants did not differ significantly across sexes, although male individuals tended to have higher numbers (Fig. S2A). Comparing the number of highly recurrently mutated genes (mutated in > 2% of the cohort), no significant differences were observed (Fig. S2B). There were no sex‐related differences within the FLT3‐ITD‐mutated subgroup. We identified 28 highly recurrently mutant genes, of which 23 genes are autosomal and five are X‐linked, including BCOR, BCORL1, PHF6, STAG2 and ZRSR2. The frequency of FLT3 (F: 82/222, M: 79/275) and DNMT3A (F: 57/222, M: 54/276) mutations was higher in females, although not statistically significant. However, seven other genes were significantly different; NPM1 (F: 62/222, M: 50/275, P = 0.01) was overrepresented in females, while RUNX1 (F: 18/222 vs M: 41/275, P = 0.025), ZRSR2 (F: 0/222, M: 10/275, P = 0.003), SRSF2 (F: 16/222, M: 46/275, P = 0.002), U2AF1 (F: 5/222, M: 21/275, P = 0.008), ASXL1 (F: 12/222, M: 30/275, P = 0.035) and EZH2 (F: 2/222, M: 13/275, P = 0.016) were overrepresented in males (Fig. 1). Notably, six of these seven genes are autosomal.

Fig. 1.

Sex‐separated overview of genes mutated in more than 2% (≥ 10 patients) of the subsampled Beat AML sample cohort (n = 498), identified by analysing the final curated exome sequencing variant list downloaded at http://www.vizome.org/aml/geneset/. Of note, the result of the FLT3 gene is separated by ITD and non‐ITD FLT3 mutations on separate rows. In all other analyses in this report, FLT3‐ITD annotations include additional samples where FLT3‐ITDs were identified exclusively by conventional methods. * indicates single genes (left panel) and gene classes (right panel) with a significantly different mutation frequency between male and female patients. Statistical significance was evaluated using the Fisher exact test, *P > 0.05.

When expanding the selection to genes mutated in > 1% of the total Beat AML selection, we found mutations in ZNF711 (F: 5/222, M: 0/276, P = 0.0172) exclusively in females, while BRCC3 (F: 0/222, M: 6/276, P = 0.0358) and SMC3 (F: 1/222, M: 8/276, P = 0.047) were both significantly overrepresented in males (Fig. S3 and Table S4A). Within the FLT3‐ITD‐positive group, we identified mutations in both BCOR (F: 0/62, M: 4/61, P = 0.057) and CCND3 (F: 0/62, M: 4/61, P = 0.057) only in male FLT3‐ITD AML (Table S4B). Interestingly, the FLT3‐ITD‐negative male and female groups were significantly different: while mutations in WT1 (F: 19/160, M: 11/215, P = 0.0207) were significantly more frequent in females, RUNX1 (F: 9/160, M: 31/215, P = 0.0066), SRSF2 (F: 14/160, M: 40/215, P = 0.0074), U2AF1 (F: 2/160, M: 15/215, P = 0.0102), ZRSR2 (F: 0/160, M: 7/215, P = 0.0219) and EZH2 (F: 2/160, M: 12/215, P = 0.0298) were significantly characteristic of males (Table S4C). This pattern is largely attributable to the excess of male samples annotated as ‘transformed’ (from a prior haematological malignancy). Excluding these cases, only the relationship between male sex and SRSF2 (F: 11/197, M: 28/215, P = 0.0112) and U2AF1 (F: 4/197, M: 14/215, P = 0.0301) remained significant. Additionally, MXRA5 (F: 5/197, M: 0/215, P = 0.0243) and NF1 (F: 5/197, M: 0/215, P = 0.0243) were identified as more frequently mutated in females, while PHF6 (F: 2/197, M: 10/215, P = 0.0378) was significantly overrepresented in males (Table S4D).

For comparison, the sex‐related distribution of somatic variants in the LAML‐TCGA cohort is presented in Table S5. Due to the selective composition of this cohort, integrated analyses of somatic variants were not performed.

The 28 recurrently mutated genes in the Beat AML cohort were subsequently categorized by gene product functional properties: DNA methylation, activating signalling, transcriptional regulation, tumour suppressor function, epigenetic modification, cohesion complex regulation and RNA splicing. We found that 14% of female vs 31% of male individuals had at least one mutation in one of the four RNA splicing genes: SRSF2, U2AF1, SF3B1 and ZRSR2 (F: 32/222, M: 85/275, P = 1.847e‐05, adj P = 0.0001). Similarly, 10% female vs 23% male individuals had at least one mutation in one of the four epigenetic modifier genes: ASXL1, BCOR, EZH2 and BCORL1 (F: 20/222, M: 60/275, P = 0.0001, adj P = 0.0004). The relationships remained significant in the nontransformed group for both RNA splicing genes (F: 23/197, M: 52/215, P = 0.0013, adj P = 0.009) and epigenetic modifier genes (F: 15/197, M: 35/215, P = 0.01, adj P = 0.03). The association was also significant within the FLT3‐ITD‐negative group, where both epigenetic modifier genes (F: 22/160, M: 65/215, P = 0.0001, adj P = 0.001) and RNA splicing genes (F: 18/160, M: 50/215, P = 0.002, adj P = 0.009) remained significantly associated with males. In the FLT3‐ITD‐positive group, the same trend was apparent (epigenetic modifiers – F: 2/62, M: 11/61, P = 0.0085, RNA splicing genes – F: 10/62, M: 20/61, P = 0.037), although not significant by adjusted P‐value (Table S6; Fig. S4).

We note that none of the sex discrepancies in somatic mutations of single genes reported as statistically significant here were significant by adjusted P‐value. However, many of our findings, including the association of FLT3‐ITD, NPM1 and DNMT3A mutations in females and RUNX1, ASXL1, SRSF2, STAG2, U2AF1 and EZH2 mutations in males, have been reported by others [11, 12, 13]. Furthermore, when categorizing individual genes by functional gene class, the findings are significant by adjusted P‐value. This significance is driven by the same individual genes significant by nonadjusted P‐value. Therefore, findings on the single gene level are also reported here.

We further explored the distribution of mutations of the frequently FLT3‐ITD co‐mutated genes DNMT3A and NPM1. As this information was available for all four cohorts, integrated analysis was performed. Mutation status of all three genes was known in 1624 cases. We found that significantly more females than males had a mutation in at least one of these three genes (F: 401/748, M: 397/876, P = 0.001). The combination of FLT3‐ITD and NPM1 mutation without DNMT3A mutation (F: 56/748, M: 40/876, P = 0.015, adj P = 0.04) and the combination of FLT3‐ITD, NPM1 and DNMT3A mutation (F: 70/74, M: 43/876, P = 0.0006, adj P = 0.004) were both significantly associated with females (Table S7; Fig. S5).

We subsequently compared the distribution of variant allele frequencies (VAF) of the genes mutated at least 10 times in the Beat AML cohort and found that VAF was significantly higher in male compared to female individuals in five genes. As expected, this included the X‐linked genes STAG2, PHF6 and BCOR, but also the autosomal gene ASXL1. BCORL1, despite being X‐bound, did not have significantly higher VAF in males. ZRSR2 was mutated exclusively in males (Fig. S6).

FLT3 was not among the genes identified with significantly different VAF across the sexes. It has previously been shown that the allelic ratio (AR) of FLT3‐ITD mutations has prognostic implications [28, 29]. To investigate whether there were sex discrepancies in FLT3‐ITD AR among these patients, we calculated the AR from the VAF (the approach is described in the figure legend of Fig. S7). We note that although there is no standardized approach to measure FLT3‐ITD AR, it is commonly measured by DNA fragment analysis by capillary electrophoresis (CE) [30, 31]. Here, we have used the VAF from next‐generation sequencing (NGS) analyses to calculate AR, as it has previously been shown that there is high concordance between CE and NGS assays in measuring FLT3 mutational burden in AML patients [32]. As was the case for VAF, we did not find significant differences in AR between males and females in this cohort (Fig. S7).

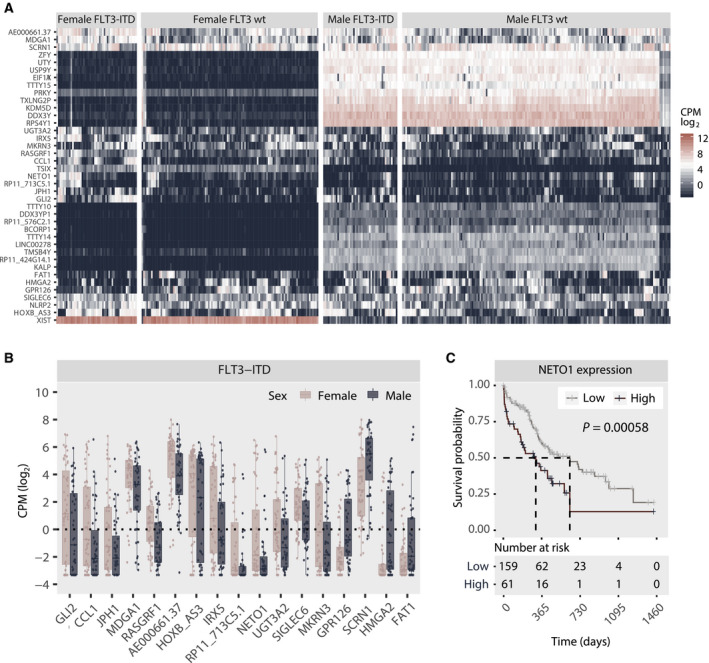

3.2. Gene expression analysis

Based on the sex‐related pattern of FLT3‐ITD and co‐mutations, we questioned whether there was sex disparity in gene expression in the FLT3‐ITD‐mutated group. We analysed 380 specimens in the Beat AML cohort, comprising 163 female and 217 male samples, respectively, of which 51 female and 47 male were FLT3‐ITD‐positive samples. We identified a total of 39 differentially expressed genes: 16 upregulated and 23 downregulated in the female FLT3‐ITD‐positive subgroup, including 14 Y‐linked, 2 X‐linked, 7 nonannotated and 16 autosomal genes (Fig. 2A; Table S8). Subtracting genes also differentially expressed in the FLT3‐ITD‐negative group, we identified a total of 17 mRNA transcripts mapped to 16 genes, of which GLI2, CCL1, JPH1, MDGA1, RASGRF1, AE000661.37, HOXB‐AS3, IRX5, NETO1/RP11‐713C5.1, UGT3A2, SIGLEC6 and MKRN3 were all significantly higher expressed in FLT3‐ITD‐positive females, while GPR126, SCRN1, HMGA2 and FAT1 were significantly higher expressed in FLT3‐ITD‐positive males (Fig. 2B; Figs S8 and S9). Comparing FLT3‐ITD‐positive (n = 98) and FLT3‐ITD‐negative specimens (n = 282) irrespective of sex, we found that GLI2, CCL1, JPH1, MDGA1, RASGRF1, AE000661.37, HOXB‐AS3, IRX5 and RP11‐713C5.1 were all significantly upregulated in FLT3‐ITD‐positive AML, while GPR126 was significantly downregulated.

Fig. 2.

(A) Heatmap depicting unsupervised clustering of CPM‐log2 values of all transcripts differentially expressed between female and male FLT3‐ITD‐positive individuals. Clustering was done by columns and rows and then manually faceted by FLT3‐ITD status and sex. (B) Pairwise comparison of the 17 transcripts identified as differentially expressed between female and male FLT3‐ITD‐positive samples based on the results of the DGE analysis, excluding samples also significantly different in the FLT3‐wt subgroup. Only statistically significant results are shown. Statistical significance was evaluated using the Wilcoxon rank sum test/Mann–Whitney test. Each dot represents an individual specimen, and the box plot graphically presents the median and the spread. The lower and upper hinges correspond the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively, and the upper and lower whisker extends to the largest and smaller values (no further than 1.5 times the total interquartile range from the hinges). Only FLT3‐positive samples are presented. The same comparison for FLT3‐ITD‐negative samples is available in Fig. S9. (C) Kaplan–Meier curve comparing the outcome of patients characterized by high (n = 61) and low (n = 159) mRNA expression (log2 CPM) of NETO1. Statistical significance is evaluated using the log‐rank test. P = 0.00058.

To explore the functional relevance of genes identified as differentially expressed, we explored their inter‐relationship with disease outcome in the 220 individuals in the Beat AML cohort where survival and expression data were available. By univariate analysis, five of the 39 differentially expressed genes were identified as significantly associated with outcome (Table S9): NETO1, TMSB4Y, TTTY10, HMGA2 and FAT1. In multivariate analysis including these five transcripts, only NETO1 remained significant (Fig. S10). High expression of NETO1 significantly correlated with poor outcome (Fig. 2C). Stratifying the patients by FLT3‐ITD status and sex, we found that high expression of NETO1 was significantly associated with poor prognosis in both FLT3‐ITD‐positive and FLT3‐ITD‐negative patients and in both sexes, although a stronger negative correlation was observed in the male subpopulation (Fig. S11). Analyses splitting the patients by both FLT3‐ITD status and sex were not performed due to small effect sizes.

3.3. Drug sensitivity and resistance testing

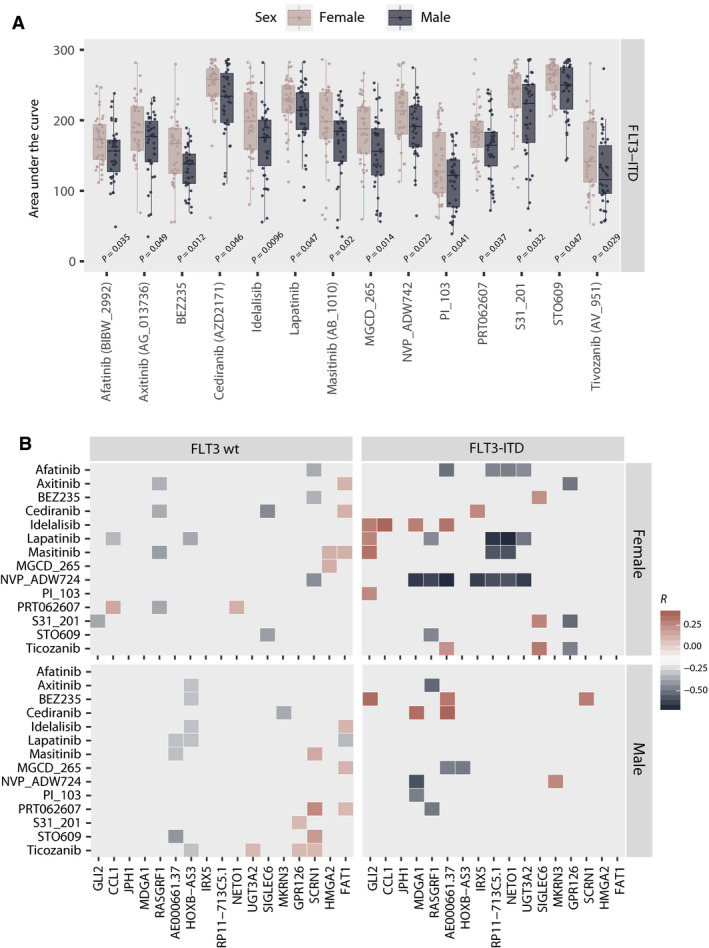

To further explore the functional consequences of the sex‐discrepant leukemic architecture, we assessed the variation in drug sensitivity profiles in the Beat AML cohort (Table S10). We focused on the 113 compounds tested in a minimum of 100 specimens, and samples overlapping with our previous analyses, resulting in 348 specimens from 311 individuals. 96/113 compounds were annotated by mechanism of action and categorized into one or more of 39 different groups (Fig. S12).

Comparing drug sensitivity across the 39 various groups between female and male individuals irrespective of ITD status, we identified a weak but significant relationship between RTK‐RET inhibitors (1/39) and higher sensitivity in females. When comparing FLT3‐ITD‐positive cases, six inhibitor families differed significantly: PI3K‐AKT‐MTOR, PI3K‐MTOR, RTK‐ERBB, RTK‐INSR‐IGF1R, SYK and CAMK inhibitors all demonstrated higher sensitivity in male samples (Fig. S13). Comparing female and male FLT3‐ITD‐negative specimens, only MEK inhibitors were significantly different, and more potent in female samples.

When examining individual compounds, we identified five compounds with significantly sex‐discrepant potency, irrespective of FLT3‐ITD status: Females were more sensitive to AT7519, palbociclib and quizartinib (AC220), while males were more sensitive to cediranib (AZD2171) and pazopanib (GW786034). Further, we identified three compounds that were significantly more potent in female FLT3‐ITD‐negative samples, including AT7519, palbociclib and trametinib (GSK1120212). Importantly, we identified 14 inhibitors that demonstrated significantly lower potency in female FLT3‐ITD‐positive samples, with an overrepresentation of inhibitors targeting tyrosine kinase receptors and downstream targets known to be influenced by FLT3‐ITD signalling, including idelalisib, BEZ235, MGCD‐265, masitinib (AB 1010), NVP‐ADW742, tivozanib (AV‐951), S31‐201, afatinib (BIBW‐2992), PRT062607, PI‐103, cediranib (AZD2171), lapatinib, STO609 and axitinib (AG‐013736) (Fig. 3A; Table S11; Fig. S14).

Fig. 3.

(A) Comparison of AUC between FLT3‐ITD‐mutated female and male specimens for the 14 compounds identified to demonstrate significant sex‐related divergence. The same comparison for FLT3‐ITD‐negative samples is available in Fig. S13. Statistical significance (P < 0.05) was evaluated using the Wilcoxon rank sum test/Mann–Whitney test. P‐values for each pairwise comparison are indicated in the plot. Additional statistical results for all compounds included in the analysis as well as sample size for all compared groups are reported in Tables S10 and S11. (B) Heatmap graphically presenting the pairwise correlation between the CPM‐log2 values of the differentially expressed genes and the AUC distribution of compounds identified as differentially potent across female and male FLT3‐ITD‐positive samples. The heatmap represents the correlation coefficient. Only statistically significant correlations are plotted.

To assess whether variation in gene expression correlated with variation in drug sensitivity, we further examined the pairwise relationships of the differentially expressed genes and the compounds with sex‐discrepant potency in FLT3‐ITD‐positive samples. We found that sensitivity to NVP‐ADW742 correlated with increasing gene expression of 7/13 RNA transcripts identified as upregulated in female FLT3‐ITD‐positive AML. Conversely, increasing GLI2 expression correlated with reduced sensitivity to 4/14 drugs that were less potent in female FLT3‐ITD‐positive AML (Fig. 3B).

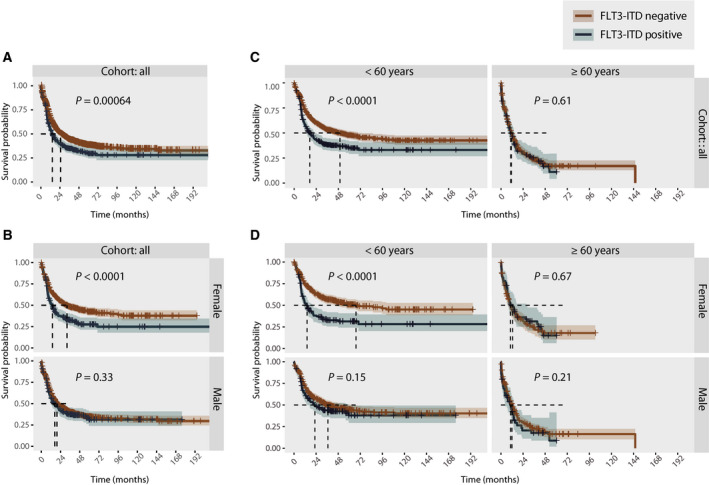

3.4. Survival

Finally, we investigated the relationships between sex and the prognostic strength of FLT3‐ITD mutation status on all cohorts combined as well as separately (Table S12a–e). HOVON 1 (n = 432) had a median follow‐up of 113.7 months, while HOVON 2 (n = 625) had a median follow‐up of 42.3 months. The Beat AML cohort had a short median follow‐up of 15.2 months. For survival analyses, only newly diagnosed cases were included (n = 303). LAML‐TCGA (n = 200) had a median follow‐up 47.2 months.

Despite FLT3‐ITD status being a recognized negative prognostic marker in AML, we found a significant association to poor outcome only in the HOVON 1 cohort (Fig. S15). When overall survival was analysed in the cohorts combined (n = 1560), we found as expected that FLT3‐ITD mutation status was associated with significantly lower survival (Fig. 4A). However, when survival analysis for all cohorts combined was split by sex, the significant prognostic association of FLT3‐ITD remained only in the female subpopulation (Fig. 4B). Analysing the cohorts independently, the same observation was apparent; FLT3‐ITD was significantly associated with poor outcome only in female patients in the HOVON1 cohort, and the same trend was observed in the HOVON2, Beat AML and LAML‐TCGA cohorts, although not significant (Figs S15 and S16; Table S12a–e).

Fig. 4.

(A) Kaplan–Meier curve comparing the outcome of FLT3‐ITD‐mutated (n = 382) and non‐FLT3‐ITD‐mutated (n = 1178) patients across the four cohorts analysed together. (B) Kaplan–Meier curve comparing the outcome of FLT3‐ITD‐mutated and non‐FLT3‐ITD‐mutated patients analysed across the four cohorts but analysed individually for females (FLT3‐ITD negative n = 523; FLT3‐ITD positive n = 198) and males (FLT3‐ITD negative n = 655; FLT3‐ITD positive n = 184). (C) Kaplan–Meier curve comparing the outcome of FLT3‐ITD‐mutated and non‐FLT3‐ITD‐mutated patients across the four cohorts analysed together, separated by age (FLT3‐ITD‐negative patients: > 60 years n = 788; ≥ 60 years n = 390. FLT3‐ITD‐positive patients: > 60 years n = 278; ≥ 60 years n = 104). (D) Kaplan–Meier curve comparing the outcome of FLT3‐ITD‐mutated and non‐FLT3‐ITD‐mutated patients across the four cohorts combined, separated by sex and age (female FLT3‐ITD negative > 60 years n = 379; ≥ 60 years n = 144, female FLT3‐ITD positive > 60 years n = 143; ≥ 60 years n = 55; male FLT3‐ITD negative > 60 years n = 409; ≥ 60 years n = 246, male FLT3‐ITD positive > 60 years n = 135; ≥ 60 years n = 49). Statistical significance is evaluated using the log‐rank test. P‐values are indicated in each individual plot.

A recent report suggests that the prognostic strength of FLT3‐ITD is age‐dependent [11]. Therefore, we performed age‐adjusted survival analyses, dichotomizing the population using a cut‐off of 60 years. Similarly, we found a significant association of FLT3‐ITD mutations with poor overall survival in the younger population only (> 60 years) (Fig. 4C). However, when the analysis was split by sex, we found an association between younger age and poor overall survival in the female subpopulation only. In the male subpopulation, there was no significant difference in overall survival between FLT3‐wt‐ and FLT3‐ITD‐mutated patients in the young (> 60 years) nor older (≥ 60 years) patients (Fig. 4D).

4. Discussion

In this work, we demonstrated sex disparity in somatic variant composition, gene expression and ex vivo drug response patterns in FLT3‐ITD‐mutated AML cases across four well‐characterized AML cohorts. FLT3‐ITD mutation status is integrated in standard risk stratification guidelines in AML. Yet, in the datasets we explored, FLT3‐ITD mutation status separated the disease outcome only in female AML. This may indicate that the prognostic utility of FLT3‐ITD mutation status is different across sexes. Of note, the prognostic value of FLT3‐ITD mutations is reportedly influenced by the mutational burden. Several studies have shown that a high FLT3‐ITD AR is linked to poor prognosis [28, 29]. Furthermore, it has also been shown that AML patients with a high FLT3‐ITD AR lacking NPM1 mutations have a worse prognosis [33]. In the latter study, an excess of males was reported in this subgroup, although no statistically significant sex disparity was observed. In our study, we did not identify FLT3‐ITD VAF nor AR as significantly different across sexes, suggesting that a difference in the mutational burden of FLT3 is likely not the cause of the sex discrepancies observed in outcome.

Another plausible explanation is related to discrepant distribution of age, disease presentation pattern and poor risk molecular features. We identified significant differences in the distribution of co‐mutations within the FLT3‐ITD‐positive subgroup. While males more frequently present with somatic variants in epigenetic modifier genes and/or RNA splicing genes, co‐mutations of FLT3‐ITD, NPM1 and DNMT3A were overrepresented in females. The mutation pattern characterizing female patients in this subgroup is previously shown to be associated with adverse prognosis in FLT3‐ITD‐mutated AML [34]. Importantly, significant differences were also observed within the FLT3‐ITD‐negative subgroup, characterized by an abundance of WT1 mutations in female specimens contrasted by overrepresentation of mutations in RUNX1, SRSF2, U2AF1, ZRSR2 and EZH2 in the male subgroup. These differences are most pronounced in the Beat AML cohort, where the mutated genes dominating the male FLT3‐ITD‐negative subpopulation are associated with poor outcome and with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) and secondary AML [35]. Whether this relationship represents inclusion asymmetry or a natural distribution is unknown. A characterization of the population‐based Swedish Acute Leukemia Registry, however, suggested that AML with an antecedent haematological disease is more frequent in males [36]. Similar to AML, there is female excess of MDS among younger individuals, and men with MDS have comparably inferior outcome [9]. Additionally, mutations in several genes overrepresented in males in the Beat AML cohort, including SRSF2 and U2AF1, are reportedly overrepresented in male MDS [37].

Sex disparity in AML demography is well known, with a progressive male excess with increasing age [9]. As the male population is generally older, one could speculate whether older age is a contributing factor to the inferior outcome of male patients, within both the FLT3‐wt‐ and FLT3‐ITD‐mutated subgroups. Specifically, age differences could potentially result in sex disparities of treatment (i.e. proportion of patients fit to receive intensive chemotherapy and/or allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation), which might be an important confounder for this study. In the HOVON cohorts, however, we found no significant differences between males and females in the proportion of transplanted patients (Table S2). Due to insufficient annotation across the cohorts, additional effects of treatment were unfortunately not evaluated in this study, and the impact of such therefore remains uncertain. Interestingly, it was recently shown that the prognostic impact of FLT3‐ITD mutations is also age‐dependent, with poor overall survival observed in younger FLT3‐ITD‐mutated (< 60 years) AML patients, but not within the older population (60–74 years) [11]. We corroborate this observation in age‐adjusted survival analyses in this study. Interestingly, when splitting the analysis by sex, this finding was significant only within the female subpopulation, further emphasizing the poor prognostic association between female sex and FLT3‐ITD mutations.

The sex‐specific age distribution characterizing AML demography suggests that cohort composition is an important confounder. The age composition of the Beat AML cohort resembles the reported demographic distribution of AML far better than the strongly selected LAML‐TCGA cohort, in part explaining the lack of sex‐biased mutations in this cohort. One could argue that age‐matching and/or use of a population‐based sample selection is the optimal condition for comparison. What remains, however, is to identify the cell‐intrinsic and cell‐extrinsic mechanisms underlying the sex disparity in AML incidence and molecular presentation. We hypothesize a significant contribution of sex‐specific leukaemia‐host interactions related to disease development. Mutations are stochastic events, and there are thus no apparent reasons to suggest that male and female haematopoietic stem cells acquire discrete mutations. What is plausible, however, is that sex is an important contextual contributor in determining the translational effect in comparative fitness of novel gene variants. Interestingly, one of the very first papers characterizing the FLT3 receptor suggested FLT3‐mediated regulatory function not only in the haematopoietic compartment but also in the gonads, placenta and brain [38]; tissues characterized by sexual dimorphism. This suggests that downstream effects of FLT3 signalling may be influenced by sex variation. This hypothesis has been substantiated by studies demonstrating functional relevance of FLT3 expression in germinal tissue [39, 40] and by investigation of the oestrogen receptor in FLT3‐positive haematopoietic cells, progenitor cells and mature cellular subsets like dendritic cells [8, 41]. Together, these observations suggest inter‐regulatory pathways between sex steroid receptors and FLT3.

The DGE analysis showed distinct expression of leukaemogenesis‐associated genes, suggesting functionally relevant cell‐intrinsic sex‐dependent differences. Of the genes more highly expressed in female FLT3‐ITD‐positive AML, the hedgehog signalling mediator GLI2 has been associated with FLT3‐ITD‐mutated leukaemia [42], while HOXB‐AS3 is reportedly upregulated in NPM1‐mutated AML, and has been implied to contribute in regulation of AML cell‐cycle progression [43]. NETO1, however, the only differentially expressed gene with prognostic impact in this cohort, is predominantly studied in the central nervous system where it is found to regulate kainate receptor signalling [44], and a role in haematopoiesis has to our knowledge not been investigated. The significance of this finding is therefore uncertain. Of the genes more highly expressed in male FLT3‐ITD‐positive AML, FAT1 was previously shown to be somatically mutated in FLT3‐ITD‐positive AML and significantly in combination with NPM1 and DNMT3A [45]. This study also showed that FAT1 exerted tumour suppressor activity specifically in FLT3‐ITD‐positive AML, perhaps providing a partial explanation for the lack of prognostic impact of FLT3‐ITD in this subpopulation.

The sum of the ex vivo drug response patterns and clinical outcome analysis suggests that response to therapeutic intervention in FLT3‐ITD‐mutated AML may be influenced by sex. Interestingly, this is in line with observations from the phase III clinical trials RATIFY and QuANTUM‐R, treating FLT3‐ITD‐positive de novo AML with FLT3‐targeting inhibitors (midostaurin and quizartinib, respectively), both reporting significant survival benefit in the male subpopulation only [14, 46]. Unfortunately, neither of these trials were powered to address potential sex differences in therapeutic response, and additional trials would be necessary to validate this observation. Our ex vivo drug sensitivity analyses did not, however, show a similar sex difference in the sensitivity to FLT3 inhibitors. It has previously been shown that FLT3‐ITD dependency in ex vivo assays is contingent on the availability of growth factors, and thus, the response to FLT3‐targeting drugs is permissive of the culture conditions [47]. This could provide a partial explanation for this discrepancy. However, the long incubation time is also an important confounder for ex vivo drug screens, and conclusions regarding the translational value of such data should be drawn with caution. Notably, sex‐related ex vivo drug response patterns have also been reported in the study of the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia [48] and in clinical trials of the tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib in other malignancies [49]. Thus, these observations may be of great importance for the field of precision haemato‐oncology, as novel targeted therapies may benefit female and male individuals differently. Although men and women in an unstratified AML population have similar prospects, this picture may be significantly different within discrete molecularly defined strata.

The impact of sex on disease presentation and outcome is likely a composite picture involving multiple factors, including societal influence and socialization (e.g. risk behaviours, occupation, stress and inclination to seek health care). Most importantly, however, sex is associated with major physiological differences, the impact of which has been insufficiently explored in haematology and in medicine in general. The field of cardiovascular disease is a noteworthy exception, where sex disparity is now widely recognized and where sex considerations are becoming integrated into research, diagnostics and clinical disease management [50, 51]. Similarly, we hypothesize that including sex‐specific considerations in preclinical and clinical research in AML could advance the pathophysiological understanding, which could ultimately lead to more precise prognostication and improved therapeutic options for these patients.

5. Conclusions

Assessment of mutation status is becoming an integrated part of the diagnostic characterization of adult AML patients. This information is subsequently incorporated into risk stratification models and clinical decision‐making. FLT3‐ITD mutation status is well established as a biomarker in AML. However, important questions remain regarding its optimal application and utility. Our observations suggest that FLT3‐ITD mutation status could be optimized as a clinical tool in a sex‐adjusted manner. Furthermore, we suggest that sex‐specific considerations should be considered in preclinical and clinical experimental design and biomarker analyses in AML. Sex should represent an independent stratification factor when randomizing to clinical trials, and be systematically included when analysing and reporting on clinical data in AML. We hypothesize that addressing sex‐related regulation of molecularly defined subgroups of AML could advance pathophysiological understanding, perhaps ultimately revealing new therapeutic possibilities.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author contributions

The study was designed by CE and BTG. CE analysed and interpreted data, prepared figures and wrote the paper. MH interpreted data, prepared figures and wrote the paper. TG, BL and PJMV collected data from the HOVON cohorts and contributed with data interpretation. All authors contributed in manuscript preparation.

Peer Review

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1002/1878‐0261.13035.

Supporting information

Fig. S1. Overview of the Beat AML sample selection analysed.

Fig. S2. Distribution of somatic variants in the Beat AML sample selection.

Fig. S3. Sex‐specific distribution of somatic mutations in the Beat AML cohort.

Fig. S4. Age‐ and sex distribution of samples with somatic mutations, presented by gene class.

Fig. S5. Sex‐specific distribution of comutations of FLT3‐ITD, NPM1 and DNMT3A in the HOVON1, HOVON2, Beat AML and LAML‐TCGA cohorts.

Fig. S6. Sex‐specific distribution of VAF of mutations detected in a minimum of 10 samples in the Beat AML sample selection.

Fig. S7. Sex‐specific distribution of FLT3‐ITD allelic ratio.

Fig. S8. Expression level of genes identified as differentially expressed between male and female FLT3‐ITD‐positive samples.

Fig. S9. Pairwise comparison of gene expression in FLT3‐ITD and non‐FLT3‐ITD samples in genes identified as differentially expressed between male and female FLT3‐ITD‐positive samples.

Fig. S10. Cox Proportional‐Hazards model including the five genes where expression was identified as significantly correlated with outcome by univariate analysis.

Fig. S11. Kaplan–Meier curves comparing patients with high and low expression of NETO1, split by FLT3‐ITD mutation status and sex.

Fig. S12. Overview of drugs and drug classes.

Fig. S13. Comparison of drug sensitivity scores between FLT3‐ITD‐mutated male and female samples, presented by drug class.

Fig. S14. Comparison of drug sensitivity scores of drugs identified with significantly different potency in male and female FLT3‐ITD‐mutated samples.

Fig. S15. Kaplan–Meier curves comparing the outcome of male and female FLT3‐ITD and FLT3‐wt patients in the HOVON1, HOVON2, Beat AML and LAML‐TCGA cohorts.

Fig. S16. Kaplan‐Meier curve comparing the outcome of female and male patients across the four cohorts separated by FLT3‐ITD mutation status.

Table S1. (A) Cohort Composition – Beat AML sample cohort (all). (B) Cohort Composition – Beat AML sample cohort (no FLT3‐ITD). (C) Cohort Composition – Beat AML sample cohort (FLT3‐ITD). (D) Cohort Composition – Beat AML sample cohort (all) split by FLT3‐ITD.

Table S2. Cohort Composition HOVON1.

Table S3. Cohort Composition HOVON2.

Table S4. (A) Somatic mutations in the Beat AML sample cohort (all). (B) Somatic mutations in the Beat AML sample cohort (FLT3‐ITD). (C) Somatic mutations in the Beat AML sample cohort (no FLT3‐ITD). (D) Somatic mutations in the Beat AML sample cohort (not transformed).

Table S5. Somatic mutations in the LAML‐TCGA cohort (all).

Table S6. Mutations in Beat AML cohort categorized by gene product function.

Table S7.FLT3‐ITD, DNMT3A and NPM1 comutations in the Beat AML, LAML‐TCGA HOVON1 and HOVON2 cohorts.

Table S8. Beat AML cohort – Differential gene expression analysis.

Table S9. Univariate Cox regression analysis of differentially expressed genes in the Beat AML cohort.

Table S10. Number of FLT3‐ITD and FLT3‐ITD wt male and female samples screened for each drug in the in drug screen.

Table S11. P‐values for comparison of drug sensitivity.

Table S12. (a) Survival analysis of all cohorts combined. (b) Survival analysis of the Beat AML cohort. (c) Survival analysis of the LAML‐TCGA cohort. (d) Survival analysis of the HOVON1 cohort. (e) Survival analysis of the HOVON2 cohort.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all patients who have participated in the respective clinical trials, and all members and clinical investigators of the HOVON/SAKK collaboration, the Cancer Genome Atlas and in the preparation and publication of the Beat AML sample cohort. This study was supported by funding from the Norwegian Cancer Society with Solveig & Ole Lunds Legacy, Øyvinn Mølbach‐Petersens Fund for Clinical Research and grant no 303445. Additionally, the study was funded through Helse Vest HF Health Trust, Grant Numbers: 911809, 911852, 912171, 240222 and 912308.

Monica Hellesøy and Caroline Engen contributed equally to this work

References

- 1.Klein SL & Flanagan KL (2016) Sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol 16, 626–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ratajczak MZ (2017) Why are hematopoietic stem cells so ‘sexy’? on a search for developmental explanation. Leukemia 31, 1671–1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whitacre CC (2001) Sex differences in autoimmune disease. Nat Immunol 2, 777–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA & Jemal A (2018) Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 68, 394–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sant M, Allemani C, Tereanu C, De Angelis R, Capocaccia R, Visser O, Marcos‐Gragera R, Maynadie M, Simonetti A, Lutz JMet al. (2010) Incidence of hematologic malignancies in Europe by morphologic subtype: results of the HAEMACARE project. Blood 116, 3724–3734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calado RT & Cle DV (2017) Treatment of inherited bone marrow failure syndromes beyond transplantation. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2017, 96–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Larocca LM, Piantelli M, Leone G, Sica S, Teofili L, Panici PB, Scambia G, Mancuso S, Capelli A & Ranelletti FO (1990) Type II oestrogen binding sites in acute lymphoid and myeloid leukaemias: growth inhibitory effect of oestrogen and flavonoids. Br J Haematol 75, 489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abdelbaset‐Ismail A, Suszynska M, Borkowska S, Adamiak M, Ratajczak J, Kucia M & Ratajczak MZ (2016) Human haematopoietic stem/progenitor cells express several functional sex hormone receptors. J Cell Mol Med 20, 134–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cartwright RA, Gurney KA & Moorman AV (2002) Sex ratios and the risks of haematological malignancies. Br J Haematol 118, 1071–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hossain MJ & Xie L (2015) Sex disparity in childhood and young adult acute myeloid leukemia (AML) survival: evidence from US population data. Cancer Epidemiol 39, 892–900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Juliusson G, Jadersten M, Deneberg S, Lehmann S, Mollgard L, Wennstrom L, Antunovic P, Cammenga J, Lorenz F, Olander Eet al. (2020) The prognostic impact of FLT3‐ITD and NPM1 mutation in adult AML is age‐dependent in the population‐based setting. Blood Adv 4, 1094–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Metzeler KH, Herold T, Rothenberg‐Thurley M, Amler S, Sauerland MC, Görlich D, Schneider S, Konstandin NP, Dufour A, Bräundl Ket al. (2016) Spectrum and prognostic relevance of driver gene mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 128, 686–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Loghavi S, Zuo Z, Ravandi F, Kantarjian HM, Bueso‐Ramos C, Zhang L, Singh RR, Patel KP, Medeiros LJ, Stingo Fet al. (2014) Clinical features of de novo acute myeloid leukemia with concurrent DNMT3A, FLT3 and NPM1 mutations. J Hematol Oncol 7, 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stone RM, Mandrekar SJ, Sanford BL, Laumann K, Geyer S, Bloomfield CD, Thiede C, Prior TW, Dohner K, Marcucci Get al. (2017) Midostaurin plus chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia with a FLT3 mutation. N Engl J Med 377, 454–464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tyner JW, Tognon CE, Bottomly D, Wilmot B, Kurtz SE, Savage SL, Long N, Schultz AR, Traer E, Abel Met al. (2018) Functional genomic landscape of acute myeloid leukaemia. Nature 562, 526–531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network (2013) Genomic and epigenomic landscapes of adult de novo acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 368, 2059–2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lowenberg B, Boogaerts MA, Daenen SM, Verhoef GE, Hagenbeek A, Vellenga E, Ossenkoppele GJ, Huijgens PC, Verdonck LF, van der Lelie J et al. (1997) Value of different modalities of granulocyte‐macrophage colony‐stimulating factor applied during or after induction therapy of acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol 15, 3496–3506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lowenberg B, van Putten W , Theobald M, Gmür J, Verdonck L, Sonneveld P, Fey M, Schouten H, de Greef G , Ferrant Aet al. (2003) Effect of priming with granulocyte colony‐stimulating factor on the outcome of chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 349, 743–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vellenga E, van Putten WL , Boogaerts MA, Daenen SM, Verhoef GE, Hagenbeek A, Jonkhoff AR, Huijgens PC, Verdonck LF, van der Lelie J et al. (1999) Peripheral blood stem cell transplantation as an alternative to autologous marrow transplantation in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia? Bone Marrow Transplant 23, 1279–1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Löwenberg B, Pabst T, Vellenga E, van Putten W , Schouten HC, Graux C, Ferrant A, Sonneveld P, Biemond BJ, Gratwohl Aet al. (2011) Cytarabine dose for acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 364, 1027–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pabst T, Vellenga E, van Putten W , Schouten HC, Graux C, Vekemans M‐C, Biemond B, Sonneveld P, Passweg J, Verdonck Let al. (2012) Favorable effect of priming with granulocyte colony‐stimulating factor in remission induction of acute myeloid leukemia restricted to dose escalation of cytarabine. Blood 119, 5367–5373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lowenberg B, Ossenkoppele GJ, van Putten W , Schouten HC, Graux C, Ferrant A, Sonneveld P, Maertens J, Jongen‐Lavrencic M, von Lilienfeld‐Toal M et al. (2009) High‐dose daunorubicin in older patients with acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 361, 1235–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lowenberg B, Pabst T, Maertens J, van Norden Y , Biemond BJ, Schouten HC, Spertini O, Vellenga E, Graux C, Havelange Vet al. (2017) Therapeutic value of clofarabine in younger and middle‐aged (18–65 years) adults with newly diagnosed AML. Blood 129, 1636–1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valk PJM, Verhaak RGW, Beijen MA, Erpelinck CAJ, van Doorn‐Khosrovani SBW , Boer JM, Beverloo HB, Moorhouse MJ, van der Spek PJ , Löwenberg Bet al. (2004) Prognostically useful gene‐expression profiles in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med 350, 1617–1628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Verhaak RG, Wouters BJ, Erpelinck CA, Abbas S, Beverloo HB, Lugthart S, Lowenberg B, Delwel R & Valk PJ (2009) Prediction of molecular subtypes in acute myeloid leukemia based on gene expression profiling. Haematologica 94, 131–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, & Smyth GK (2015) limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA‐sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res 43, e47. 10.1093/nar/gkv007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wickham H (2016) ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. Springer‐Verlag, New York, NY. ISBN 978‐3‐319‐24277‐4. Available at: https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dohner H, Estey EH, Amadori S, Appelbaum FR, Buchner T, Burnett AK, Dombret H, Fenaux P, Grimwade D, Larson RAet al. (2010) Diagnosis and management of acute myeloid leukemia in adults: recommendations from an international expert panel, on behalf of the European LeukemiaNet. Blood 115, 453–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schlenk RF, Kayser S, Bullinger L, Kobbe G, Casper J, Ringhoffer M, Held G, Brossart P, Lubbert M, Salih HRet al. (2014) Differential impact of allelic ratio and insertion site in FLT3‐ITD‐positive AML with respect to allogeneic transplantation. Blood 124, 3441–3449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daver N, Schlenk RF, Russell NH & Levis MJ (2019) Targeting FLT3 mutations in AML: review of current knowledge and evidence. Leukemia 33, 299–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levis M (2013) FLT3 mutations in acute myeloid leukemia: what is the best approach in 2013? Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2013, 220–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith CC, Perl AE, Altman JK, Carson A, Cortes JE, Stenzel TT, Hill J, Lu Q, Bahceci E & Levis MJ (2017) Comparative assessment of FLT3 variant allele frequency by capillary electrophoresis and next‐generation sequencing in FLT3mut+ patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) acute myeloid leukemia (AML) who received gilteritinib therapy. Blood 130(Suppl 1), 1411. 10.1182/blood.V130.Suppl_1.1411.1411 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sakaguchi M, Yamaguchi H, Najima Y, Usuki K, Ueki T, Oh I, Mori S, Kawata E, Uoshima N, Kobayashi Yet al. (2018) Prognostic impact of low allelic ratio FLT3‐ITD and NPM1 mutation in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Adv 2, 2744–2754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bezerra MF, Lima AS, Pique‐Borras MR, Silveira DR, Coelho‐Silva JL, Pereira‐Martins DA, Weinhauser I, Franca‐Neto PL, Quek L, Corby Aet al. (2020) Co‐occurrence of DNMT3A, NPM1, FLT3 mutations identifies a subset of acute myeloid leukemia with adverse prognosis. Blood 135, 870–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindsley RC, Mar BG, Mazzola E, Grauman PV, Shareef S, Allen SL, Pigneux A, Wetzler M, Stuart RK, Erba HPet al. (2015) Acute myeloid leukemia ontogeny is defined by distinct somatic mutations. Blood 125, 1367–1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hulegardh E, Nilsson C, Lazarevic V, Garelius H, Antunovic P, Rangert Derolf A, Mollgard L, Uggla B, Wennstrom L, Wahlin Aet al. (2015) Characterization and prognostic features of secondary acute myeloid leukemia in a population‐based setting: a report from the Swedish Acute Leukemia Registry. Am J Hematol 90, 208–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang X, Song X & Yan X (2019) Effect of RNA splicing machinery gene mutations on prognosis of patients with MDS: a meta‐analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 98, e15743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosnet O, Marchetto S, deLapeyriere O & Birnbaum D (1991) Murine Flt3, a gene encoding a novel tyrosine kinase receptor of the PDGFR/CSF1R family. Oncogene 6, 1641–1650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kwon WS, Kim YJ, Ryu DY, Kwon KJ, Song WH, Rahman MS & Pang MG (2018) Fms‐like tyrosine kinase 3 is a key factor of male fertility. Theriogenology 126, 145–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okamura Y, Myoumoto A, Manabe N, Tanaka N, Okamura H & Fukumoto M (2001) Protein tyrosine kinase expression in the porcine ovary. Mol Hum Reprod 7, 723–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laffont S, Seillet C & Guery JC (2017) Estrogen receptor‐dependent regulation of dendritic cell development and function. Front Immunol 8, 108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lim Y, Gondek L, Li L, Wang Q, Ma H, Chang E, Huso DL, Foerster S, Marchionni L, McGovern Ket al. (2015) Integration of Hedgehog and mutant FLT3 signaling in myeloid leukemia. Sci Transl Med 7, 291ra96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Papaioannou D, Petri A, Thrue CA, Volinia S, Kroll K, Pearlly Y, Bundschuh R, Singh G, Kauppinen S, Bloomfield CDet al. (2016) HOXB‐AS3 regulates cell cycle progression and interacts with the Drosophila splicing human behavior (DSHB) complex in NPM1‐mutated acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 128, 1514. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Orav E, Atanasova T, Shintyapina A, Kesaf S, Kokko M, Partanen J, Taira T & Lauri SE (2017) NETO1 guides development of glutamatergic connectivity in the hippocampus by regulating axonal kainate receptors. eNeuro 4, ENEURO.0048‐17.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garg M, Nagata Y, Kanojia D, Mayakonda A, Yoshida K, Haridas Keloth S, Zang ZJ, Okuno Y, Shiraishi Y, Chiba Ket al. (2015) Profiling of somatic mutations in acute myeloid leukemia with FLT3‐ITD at diagnosis and relapse. Blood 126, 2491–2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cortes JE, Khaled S, Martinelli G, Perl AE, Ganguly S, Russell N, Kramer A, Dombret H, Hogge D, Jonas BAet al. (2019) Quizartinib versus salvage chemotherapy in relapsed or refractory FLT3‐ITD acute myeloid leukaemia (QuANTUM‐R): a multicentre, randomised, controlled, open‐label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 20, 984–997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karjalainen R, Pemovska T, Popa M, Liu M, Javarappa KK, Majumder MM, Yadav B, Tamborero D, Tang J, Bychkov Det al. (2017) JAK1/2 and BCL2 inhibitors synergize to counteract bone marrow stromal cell‐induced protection of AML. Blood 130, 789–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu X, Yang J, Zhang Y, Fang Y, Wang F, Wang J, Zheng X & Yang J (2016) A systematic study on drug‐response associated genes using baseline gene expressions of the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia. Sci Rep 6, 22811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Segarra I, Modamio P, Fernandez C & Marino EL (2016) Sunitinib possible sex‐divergent therapeutic outcomes. Clin Drug Investig 36, 791–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Regitz‐Zagrosek V & Kararigas G (2017) Mechanistic pathways of sex differences in cardiovascular disease. Physiol Rev 97, 1–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shufelt CL, Pacheco C, Tweet MS & Miller VM (2018) Sex‐specific physiology and cardiovascular disease. Adv Exp Med Biol 1065, 433–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1. Overview of the Beat AML sample selection analysed.

Fig. S2. Distribution of somatic variants in the Beat AML sample selection.

Fig. S3. Sex‐specific distribution of somatic mutations in the Beat AML cohort.

Fig. S4. Age‐ and sex distribution of samples with somatic mutations, presented by gene class.

Fig. S5. Sex‐specific distribution of comutations of FLT3‐ITD, NPM1 and DNMT3A in the HOVON1, HOVON2, Beat AML and LAML‐TCGA cohorts.

Fig. S6. Sex‐specific distribution of VAF of mutations detected in a minimum of 10 samples in the Beat AML sample selection.

Fig. S7. Sex‐specific distribution of FLT3‐ITD allelic ratio.

Fig. S8. Expression level of genes identified as differentially expressed between male and female FLT3‐ITD‐positive samples.

Fig. S9. Pairwise comparison of gene expression in FLT3‐ITD and non‐FLT3‐ITD samples in genes identified as differentially expressed between male and female FLT3‐ITD‐positive samples.

Fig. S10. Cox Proportional‐Hazards model including the five genes where expression was identified as significantly correlated with outcome by univariate analysis.

Fig. S11. Kaplan–Meier curves comparing patients with high and low expression of NETO1, split by FLT3‐ITD mutation status and sex.

Fig. S12. Overview of drugs and drug classes.

Fig. S13. Comparison of drug sensitivity scores between FLT3‐ITD‐mutated male and female samples, presented by drug class.

Fig. S14. Comparison of drug sensitivity scores of drugs identified with significantly different potency in male and female FLT3‐ITD‐mutated samples.

Fig. S15. Kaplan–Meier curves comparing the outcome of male and female FLT3‐ITD and FLT3‐wt patients in the HOVON1, HOVON2, Beat AML and LAML‐TCGA cohorts.

Fig. S16. Kaplan‐Meier curve comparing the outcome of female and male patients across the four cohorts separated by FLT3‐ITD mutation status.

Table S1. (A) Cohort Composition – Beat AML sample cohort (all). (B) Cohort Composition – Beat AML sample cohort (no FLT3‐ITD). (C) Cohort Composition – Beat AML sample cohort (FLT3‐ITD). (D) Cohort Composition – Beat AML sample cohort (all) split by FLT3‐ITD.

Table S2. Cohort Composition HOVON1.

Table S3. Cohort Composition HOVON2.

Table S4. (A) Somatic mutations in the Beat AML sample cohort (all). (B) Somatic mutations in the Beat AML sample cohort (FLT3‐ITD). (C) Somatic mutations in the Beat AML sample cohort (no FLT3‐ITD). (D) Somatic mutations in the Beat AML sample cohort (not transformed).

Table S5. Somatic mutations in the LAML‐TCGA cohort (all).

Table S6. Mutations in Beat AML cohort categorized by gene product function.

Table S7.FLT3‐ITD, DNMT3A and NPM1 comutations in the Beat AML, LAML‐TCGA HOVON1 and HOVON2 cohorts.

Table S8. Beat AML cohort – Differential gene expression analysis.

Table S9. Univariate Cox regression analysis of differentially expressed genes in the Beat AML cohort.

Table S10. Number of FLT3‐ITD and FLT3‐ITD wt male and female samples screened for each drug in the in drug screen.

Table S11. P‐values for comparison of drug sensitivity.

Table S12. (a) Survival analysis of all cohorts combined. (b) Survival analysis of the Beat AML cohort. (c) Survival analysis of the LAML‐TCGA cohort. (d) Survival analysis of the HOVON1 cohort. (e) Survival analysis of the HOVON2 cohort.