Abstract

Nurses are confronting a number of negative mental health consequences owing to high burdens of grief during COVID-19. Despite increased vaccination efforts and lower hospitalization and mortality rates, the long-term effects of mass bereavement are certain to impact nurses for years to come. The nurse coaching process is an evidence-based strategy that nurse leaders can use to assist staff in mitigating negative mental health outcomes associated with bereavement. The End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium brought together a team of palliative nursing experts early in the pandemic to create resources to support nurses across settings and promote nurse well-being. This article shares a timely resource for health systems and nursing administration that leverages the nurse coaching process to support bereaved staff in a safe and therapeutic environment.

KEY WORDS: bereavement, coaching, COVID-19, nurse coaching, nurse leadership, psychological distress, staff support

Nurses are being pushed beyond their limits during the COVID-19 response. Health systems and the nurses they employ continue to be faced with understaffing, long hours, ethical dilemmas, substantial numbers of patient deaths, and the emotional demands of supporting families remotely through grief and bereavement.1 More than a year into the pandemic, these stressors are compounding over time, with little opportunity for nurses to process their own grief—contributing to a mounting psychological toll.

Nurses responding to COVID-19 have reported a variety of mental health symptomatology: up to 64% have reported psychological distress2,3; 53%, depression3,4; and 41%, anxiety.3,4 Risk factors, such as witnessing patient deaths, have been associated with particularly deleterious effects on these mental health outcomes (eg, a 4-fold increase in the likelihood of posttraumatic stress symptoms).5 Furthermore, nurses screen positive for these outcomes at higher rates than other health care providers.3,6

It is estimated that the prolonged effects of these mental health outcomes could last up to 3 years,6 which also holds significance for the quality of patient care.7 Evidence-based strategies, such as the nurse coaching process, offer health systems and nursing administration scalable approaches to assist nurses throughout the bereavement process. The purpose of this article is to promote the nurse coaching process as a tool for nurse leaders to best support staff in a safe and therapeutic environment.

Nurse Coaching and the End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium

Nurse coaching is a “skilled, purposeful, results-oriented, and structured relationship and person-centered interaction…that is provided by a nurse for the purpose of promoting achievement of a person's goals.”8 This process has been used in a number of clinical settings to improve clients' health outcomes.9-13 The nurse coach prioritizes the well-being of the client (eg, staff nurse) through a relationship-based ethic that integrates the values of holism, caring, and moral insight.8,14 Coaching conversations include many communication skills that nurses are familiar with—therapeutic presence, deep listening, use of silence, motivational interviewing—to help clients identify their individual barriers and facilitators to realizing their goals.15

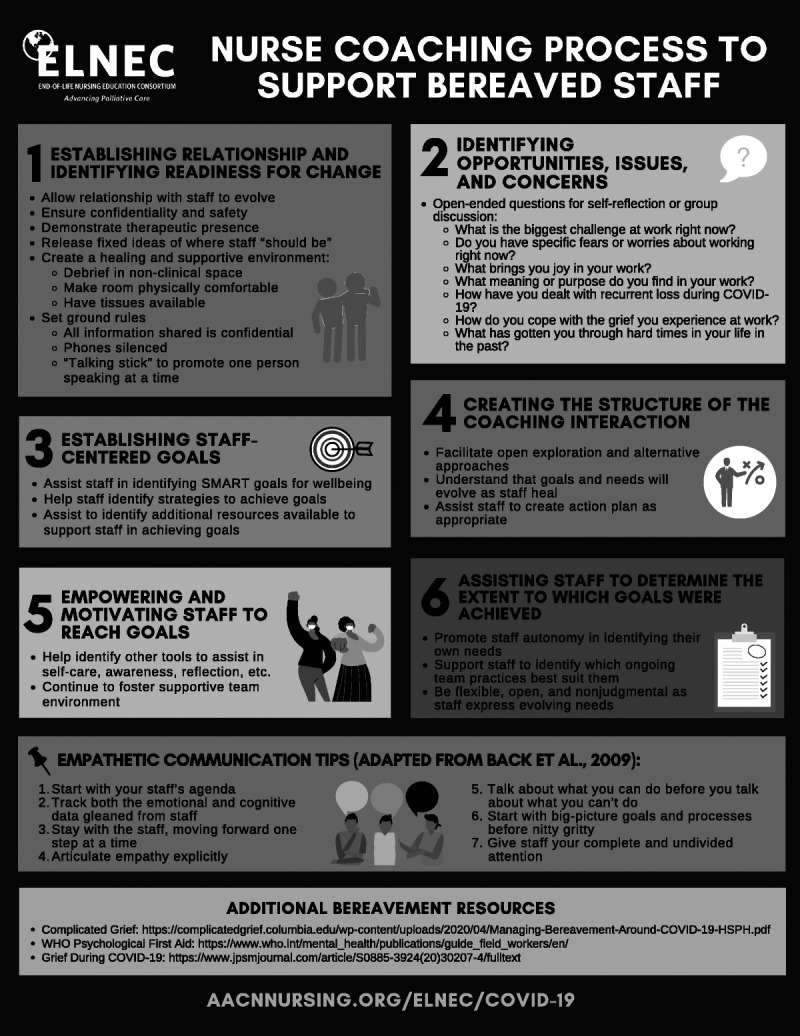

During the COVID-19 pandemic, national palliative nurse experts collaborated with the End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium to provide resources to support nurses and promote nurse well-being.16 The infographic in the Figure 1 describes the 6-step nurse coaching process paired with empathic communication tips to help nurse leaders guide staff through bereavement debriefings. An extended webinar presentation on this topic can be accessed free of charge through the End-of-Life Nursing Education Consortium (https://www.aacnnursing.org/ELNEC/COVID-19) to further assist leadership in supporting staff through grief.

FIGURE 1.

End-of-life nursing education consortium (ELNEC) and palliative care informed nurse coaching process to support bereaved staff.

CONCLUSION

Promoting nurse well-being requires systemic supports at organizational and leadership levels to proactively identify and manage the mental health impacts among nurses.17 Negative work culture, poor supervisor support, and lack of opportunities to share experiences and feelings with other colleagues have been associated with worse mental health outcomes (eg, psychological distress, depression) among health care professionals.17,18 Thus, institutional resources, such as clinician access to both informal and professional support, undergird health care professionals' abilities to cope with mental health impacts during crises like COVID-19.19

Strategies to promote team cohesion and opportunities to informally debrief and receive peer support have been advocated, and may offer greater benefit than individualized approaches, which may be insufficient in meeting bereavement needs among health care professionals.17,19,20 The nurse coaching process can be used in conjunction with other strategies to support bereaved staff during COVID-19 and into the future as the profession begins to collectively evaluate the long-term mental health impacts of the pandemic.

Footnotes

William E. Rosa is funded by National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748 and National Cancer Institute award number T32 CA009461. Kristin Levoy is supported by National Institute of Nursing Research Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award program T32 NR009356.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Kristin Levoy, Email: levoy@nursing.upenn.edu.

Vanessa Battista, Email: battistv@gmail.com.

Constance Dahlin, Email: cdahlin3@gmail.com.

Cheryl Thaxton, Email: thaxca@aol.com.

Kelly Greer, Email: kgreer@coh.org.

References

- 1.Rabow MW, Huang CS, White-Hammond GE, Tucker RO. Witnesses and victims both: Healthcare workers and grief in the time of COVID-19 [published online ahead of print, 2021 Feb 5]. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;S0885–3924(21):00164–00160. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.01.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shahrour G, Dardas LA. Acute stress disorder, coping self-efficacy and subsequent psychological distress among nurses amid COVID-19. J Nurs Manag. 2020;28:1686–1695. 10.1111/jonm.13124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shechter A Diaz F Moise N, et al. Psychological distress, coping behaviors, and preferences for support among New York healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020;66:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiong H, Yi S, Lin Y. The psychological status and self-efficacy of nurses during COVID-19 outbreak: a cross-sectional survey. Inquiry. 2020. doi: 10.1177/0046958020957114, 57, 004695802095711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mosheva M Gross R Hertz-Palmor N, et al. The association between witnessing patient death and mental health outcomes in frontline COVID-19 healthcare workers. Depress Anxiety. 2021;38:10.1002/da.23140–10.1002/da.23479. doi: 10.1002/da.23140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Preti E Di Mattei V Perego G, et al. The psychological impact of epidemic and pandemic outbreaks on healthcare workers: rapid review of the evidence. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020;22(8):43. doi: 10.1007/s11920-020-01166-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melnyk BM Orsolini L Tan A, et al. A national study links nurses' physical and mental health to medical errors and perceived worksite wellness. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60(2):126–131. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Southard ME, Dossey BM, Bark L, Schaub BG. The Art & Science of Nurse Coaching: The Provider's Guide to Coaching Scope & Competencies. 2nd ed.Silver Spring, MD: American Nurses Association; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Young H, Miyamoto S, Ward D, Dharmar M, Tang-Feldman Y, Berglund L. Sustained effects of a nurse coaching intervention via telehealth to improve health behavior change in diabetes. Telemed J E Health. 2014;20(9):828–834. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2013.0326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Egede LE Walker R Williams JS, et al. Financial incentives and nurse coaching to enhance diabetes outcomes (FINANCE-DM): a trial protocol. BMJ Open. 2020;(12):10, e043760. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delaney C, Bark L. The experience of holistic nurse coaching for patients with chronic conditions. J Holist Nurs. 2019;37(3):225–237. doi: 10.1177/0898010119837109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kivelä K, Elo S, Kyngäs H, Kääriäinen M. The effects of nurse-led health coaching on health-related quality of life and clinical health outcomes among frequent attenders: a quasi-experimental study. Patient Educ Couns. 2020;103(8):1554–1561. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2020.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stan DL Cutshall SM Adams TF, et al. Wellness coaching: an intervention to increase healthy behavior in breast cancer survivors. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2020;24(3):305–315. doi: 10.1188/20.CJON.305-315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dossey BM, Luck S, Schaub BG. Nurse Coaching: Integrative Approaches for Health and Wellbeing. North Miami, FL: International Nurse Coach Association; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Avino KM, McElligot D, Dossey BM, Luck S. Nurse coaching. In: Helming MAB, Shields DA, Avino KM, Rosa WE, eds. Dossey and Keegan’s Holistic Nursing: A Handbook for Practice. 8th ed. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 16.End-of-life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC) . ELNEC support for nurses during COVID-19. https://www.aacnnursing.org/ELNEC/COVID-19. Accessed March 25, 2021.

- 17.Brooks SK, Rubin GJ, Greenberg N. Traumatic stress within disaster-exposed occupations: overview of the literature and suggestions for the management of traumatic stress in the workplace. Br Med Bull. 2019;129(1):25–34. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldy040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao F, Ahmed F, Faraz NA. Caring for the caregiver during COVID-19 outbreak: does inclusive leadership improve psychological safety and curb psychological distress? A cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020;110:103725. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Selman LE, Chao D, Sowden R, Marshall S, Chamberlain C, Koffman J. Bereavement support on the frontline of COVID-19: recommendations for hospital clinicians. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(2):e81–e86. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norful AA, Rosenfeld A, Schroeder K, Travers JL, Aliyu S. Primary drivers and psychological manifestations of stress in frontline healthcare workforce during the initial COVID-19 outbreak in the United States. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2021;69:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2021.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]