Abstract

We have examined the role of protein phosphorylation in the modulation of the key muscle-specific transcription factor MyoD. We show that MyoD is highly phosphorylated in growing myoblasts and undergoes substantial dephosphorylation during differentiation. MyoD can be efficiently phosphorylated in vitro by either purified cdk1-cyclin B or cdk1 and cdk2 immunoprecipitated from proliferative myoblasts. Comparative two-dimensional tryptic phosphopeptide mapping combined with site-directed mutagenesis revealed that cdk1 and cdk2 phosphorylate MyoD on serine 200 in proliferative myoblasts. In addition, when the seven proline-directed sites in MyoD were individually mutated, only substitution of serine 200 to a nonphosphorylatable alanine (MyoD-Ala200) abolished the slower-migrating hyperphosphorylated form of MyoD, seen either in vitro after phosphorylation by cdk1-cyclin B or in vivo following overexpression in 10T1/2 cells. The MyoD-Ala200 mutant displayed activity threefold higher than that of wild-type MyoD in transactivation of an E-box-dependent reporter gene and promoted markedly enhanced myogenic conversion and fusion of 10T1/2 fibroblasts into muscle cells. In addition, the half-life of MyoD-Ala200 protein was longer than that of wild-type MyoD, substantiating a role of Ser200 phosphorylation in regulating MyoD turnover in proliferative myoblasts. Taken together, our data show that direct phosphorylation of MyoD Ser200 by cdk1 and cdk2 plays an integral role in compromising MyoD activity during myoblast proliferation.

Skeletal muscle differentiation is characterized by withdrawal of myoblasts from the cell cycle, induction of muscle-specific gene expression, and cell fusion into multinucleated myotubes. All of these events are coordinated by a family of muscle-specific transcription factors including MyoD (8), Myf5 (4), myogenin (12, 56), and MRF4 (39). These proteins show homology within a basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) domain that mediates both heterodimerization with ubiquitous activating bHLH proteins such as E12 and E47 and DNA binding to a specific sequence, CANNTG, called the E box (9, 25, 30). One of the most remarkable properties of myogenic factors is that their ectopic expression in nonmuscle cells forces these cells into muscle differentiation, a process known as myogenic conversion (6, 8). Although capable of inhibiting cell proliferation (7, 47) and inducing differentiation, MyoD is constitutively expressed in proliferating myoblasts long before differentiation takes place, implying that its activity is regulated in replicating cells (26, 49). Indeed, when cultured myoblasts are exposed to serum or growth factors such as basic fibroblast growth factor and transforming growth factor β, both muscle differentiation and MyoD activity are inhibited (34, 48). One of the inhibitory mechanisms that target MyoD in proliferative myoblasts involves the Id family of proteins. These HLH proteins, which are devoid of DNA-binding basic domains, can heterodimerize with bHLH factors, thus inhibiting their binding to DNA (3). In addition, like most transcription factors (23), MyoD is a phosphoprotein (49), and its phosphorylation could constitute an important mechanism by which mitogens negatively regulate its activity. Protein kinase C (PKC), which is activated in response to fibroblast growth factor, was first shown to inhibit the DNA binding activity of myogenin (28) by phosphorylating a site conserved in the basic region of all myogenic HLH proteins. This same site was shown not to be required for the inhibition of MRF4 by PKC (19). Protein kinase A (PKA) was also demonstrated to repress the activity of Myf5 and MyoD, albeit via an indirect mechanism (55).

Because differentiation requires withdrawal from the cell cycle, kinases involved in cell cycle control are likely candidates for the inhibition of MyoD in the proliferative state. Cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), in association with their regulatory partners, the cyclins, are key regulators of cell cycle progression. cdk2-cyclin A/E and cdk4-cdk6/cyclin D are involved in the G1/S transition, whereas cdk1 (also called cdc2)-cyclin A/B is implicated in the G2/M transition of the cell cycle (32, 40). Several lines of evidence support the involvement of CDKs in the regulation of muscle differentiation. Overexpression of cyclin D1 inhibits MyoD muscle-specific gene transactivation (38, 42, 43). Cyclins A and E have, to a lesser extent, the same effect alone or in combination with cdk2, whereas the effects observed with cyclins B, D2, and D3 remain controversial (17, 38, 42, 43). Cyclin-dependent inhibition of muscle gene transactivation requires CDK activation and can be reversed by overexpression of p21 (Waf1, Cip1), one of the general CDK inhibitors. Interestingly, induction of p21 constitutes one of the earliest markers of cell cycle exit associated with myoblast differentiation (2) and depends on MyoD (16, 18). Although CDKs appear to be involved in the inhibition of MyoD in proliferating myoblasts, no direct phosphorylation of MyoD by CDKs has been described.

In this report, we show that MyoD phosphorylation is high in proliferative C2 myoblasts and diminishes during the course of muscle differentiation. By tryptic phosphopeptide mapping and mutational analysis of MyoD, we show that a CDK consensus site comprising Ser200 is phosphorylated in vivo in myoblasts and in vitro by cdk1 (cdc2) and cdk2. We demonstrate that a nonphosphorylable Ser200 mutant of MyoD shows both higher activity in transactivating muscle-specific gene expression through the E box and greater ability to convert 10T1/2 fibroblasts to muscle cells. We also report that Ser200 phosphorylation is involved in specifying the short half-life of MyoD in proliferative myoblasts by showing that MyoD-Ala200 displays a half-life threefold higher than that of wild-type MyoD protein (MyoD-wt). These data show that direct CDK-dependent phosphorylation of MyoD on Ser200 is involved in negatively regulating MyoD activity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

C2.7 myoblasts (36) were kept in growth medium (50% Dulbecco modified Eagle medium [DMEM; ICN, Orsay, France], 50% HaM F12 [Gibco BRL, Life Technologies, Cergy Pontoise, France]) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; DAP, Neuf-Brisach, France). To induce terminal differentiation, myoblasts were placed in differentiation medium (DMEM, 2% FCS). A nearly complete differentiation is obtained in 60 h. Mouse 10T1/2 cells (American Type Culture Collection, Biovaley, France) were maintained in growth medium and moved to differentiation medium following transfection to induce myogenic conversion.

Purified proteins.

Production and purification of full-length murine MyoD have been described elsewhere (52); MyoD-Ala5 and MyoD-Ala200 were purified by using the same protocol. The active kinase cdk1-cyclin B was purified from starfish oocytes (24).

2D gel electrophoresis.

Proteins extracts from proliferating and differentiated C2.7 cells were analyzed by two-dimensional (2D) electrophoresis by the method of O’Farrell (33). First-dimension electrofocusing gels contained 9.5 M urea, 2% (wt/vol) Nonidet P-40 (NP-40), and 5% dithiothreitol (DTT). The ampholine mixture used was composed of 60% (vol/vol) ampholine pH 3 to 10 and 40% (vol/vol) ampholine pH 5 to 7. The second dimension was performed on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–12% polyacrylamide gels. Following transfer onto nitrocellulose membranes, MyoD isoforms were revealed by Western blotting with anti-MyoD monoclonal antibody 5.8A (kindly provided by P. Dias and P. Houghton, Memphis, Tenn.). For calf intestinal phosphatase (CIP) treatment, nuclear extracts from C2.7 myoblasts were treated with 20 U of CIP (Promega, Charbonnieres, France) for 30 min at 37°C.

Western blotting.

Nitrocellulose membranes were blocked with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 10% dry milk and incubated either with anti-CDKs (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, Calif.) or anti-MyoD polyclonal antibody C20 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) diluted 1/300 or with monoclonal anti-α-tubulin (Sigma, St. Quentin Fallavier, France) diluted 1/2,000 in PBS containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin for 1 h at room temperature. After three washes in PBS, blots were incubated with secondary antibodies (horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse; Amersham, les Ulis, France) and developed by using the Amersham ECL (enhanced chemiluminescence) reagent.

In vivo labeling and immunoprecipitation.

Cells (myoblasts and myotubes) cultured in 60-mm-diameter dishes were labeled with [32P]orthophosphate (1 mCi/ml) for 2 h at 37°C. After three washes with PBS, cells were lysed in 100 μl of a mixture composed of (by volume) Laemmli buffer–2% NP-40, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Lysates were boiled for 3 min, diluted to 500 μl in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (10 mM Na2HPO4, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM DTT, 0.1% NP-40, 5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS), and homogenized by passages through a 21-gauge needle. Following 10 min of centrifugation at 13,000 rpm, supernatants were precleared by incubation with protein G-Sepharose beads (Pharmacia, Orsay, France) and incubated for 2 h at 4°C with anti-MyoD monoclonal antibody 5.8A; 20 μl of protein G-Sepharose beads was added for 30 min at 4°C, and the beads were washed three times with RIPA buffer and once with PBS before loading onto a SDS–12% gel for polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). The radioactivity was analyzed by autoradiography. The amount of immunoprecipitated MyoD was estimated by Western blotting using antibody C20 anti-MyoD polyclonal as described above.

Immunoprecipitation and CDK assays.

Cells (myoblasts and myotubes) were washed twice in 1× PBS and scraped in 1 ml of PBS. After centrifugation at 3,000 rpm, pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 0.4% NP-40, 2 mM EDTA, 50 mM NaF, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM ATP, 2 μg each of leupeptin and aprotinin per ml, 2 mM sodium vanadate, 2 mM DTT). After 10 passages through a 21-gauge needle, cell lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm. Protein concentrations were determined by using a Bio-Rad DC kit. Extracts (200 μg) were immunoprecipitated with either monoclonal anti-cdk1 (C7) or polyclonal anti-cdk2 (M2) or anti-cdk5 (C8) antibodies for 2 h at 4°C. All antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used at a 1/50 dilution. Depending on antibody species, protein A- or G-Sepharose was added for 1 h at 4°C. After centrifugation, pellets were washed three times with lysis buffer, twice in lysis buffer containing 400 mM NaCl, and twice in kinase buffer (25 mM HEPES [pH 7.4], 25 mM MgCl2, 25 mM β-glycerophosphate, 2 mM DTT, 0.1 mM NaVO3). Purified cdk1-cyclin B or beads containing CDKs immunoprecipitated from C2.7 cells were incubated in 20 μl of kinase buffer containing 50 μM ATP and 5 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP (Kodak X-ray films) and then used for Western blot analyses.

Phosphopeptide mapping.

32P-labeled MyoD (immunoprecipitated from myoblasts) and bacterially expressed MyoD-wt, MyoD-Ala5, and MyoD-Ala200 phosphorylated in vitro by cdk1-cyclin B were excised from SDS-gels and digested twice with 10 μg of trypsin for 12 h at 37°C in buffer containing 200 mM NH4H2CO3. Digests were desalted by repeated lyophilization and loaded onto thin-layer chromatography plates (Merck-Coger, Paris, France) for 2D peptide mapping. The first dimension was run for 30 min at 1,000 V at pH 1.9 (formic acid-acetic acid-water [50:150:1,800]); second-dimension chromatography was performed in phosphochromo buffer (isobutyric acid, 1-butanol–pyridine–acetic acid–water [15:10:3:2]). 32P-labeled peptides were subsequently visualized by autoradiography of the thin-layer chromatography plates.

Mutation of the seven proline-directed sites present on MyoD.

The MyoD cDNA was mutagenized in the Moloney sarcoma virus long terminal repeat expression vector pEMSV-scribe. MyoD mutants were obtained by oligonucleotide-directed mutagenesis using a QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, Ozyme, Montigny le Bretonneux, France) as instructed by the manufacturer. Oligonucleotides were 30 to 32 nucleotides in length, with 14 to 15 nucleotides of exact homology with MyoD in the region flanking the substitution. Mutant clones were screened with the oligonucleotide used for mutagenesis, which had been labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase by using [γ-32P]ATP. Selected clones were used for preparative plasmid isolation and then sequenced by using a Sequenase 2.0 kit (U.S. Biochemical) and [35S]dATP (3,000 Ci/mmol; Amersham). The mutants resulting from a change of serine or threonine to alanine were designated MyoD-Ala5, MyoD-Ala37, MyoD-Ala200, MyoD-Ala262, MyoD-Ala277, MyoD-Ala296, and MyoD-Ala298. Substitution of alanine for serine at amino acids 5 and 200 was also performed in the T7 procaryote expression construct pET3a-MyoD (52).

Phosphorylation of MyoD wild-type and mutant proteins.

MyoD-wt and MyoD alanine mutants were obtained by in vitro translation as described by the manufacturer (TnT coupled reticulocyte lysate system; Promega) and were phosphorylated by cdk1-cyclin B as described above but in the absence of [γ-32P]ATP. 35S-radiolabeled proteins were visualized by autoradiography.

Transfection and chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) assays.

Plasmids used for transfection were pEMSV-MyoD wild type and mutants, pCMV-βgal (Stratagene, Paris, France), pαAch-CAT+ and pαAchmutCAT+ (gifts from J. Piette, Montpellier, France) (35), and p4E-TK-CAT and pTK-CAT (gifts from H. Weintraub) (54). For Western blot analyses, transfection of 10T1/2 cells were carried out with a ratio of 5 μl of Lipofectamine to 1 μg of DNA as described by the manufacturer (Gibco BRL, Life Technologies).

In CAT assays comparing MyoD-wt and MyoD-Ala200 transactivation activities, transfections were done in 60-mm-diameter dishes with 2 μg of total DNA composed of pEMSV-MyoD-wt, pEMSV-MyoD-Ala200, pEMSV–pCMV-βgal–pαAch-CAT+, pαAchmutCAT+, p4E-TK-CAT, or pTK-CAT (at a ratio of 1.6/0.2/0.2) and 10 μl of Lipofectamine. Transfected cells were kept in proliferative medium for 36 h and harvested for CAT assay. CAT assays were performed on cell extracts by using 1-deoxy-(dichloroacetyl-1-3H)chloramphenicol (200 mCi/mmol; Amersham) by a nonchromatographic method as described by Nielsen et al. (31). Promoter activities were expressed as CAT activity units per β-galactosidase unit.

Myogenic conversion.

10T1/2 cells were transfected with 1 μg of plasmid expressing either MyoD-wt or MyoD-Ala200; 24 h after transfection, cells were collected for Western blot analyses or moved to differentiation medium for 60 h and either used for Western blot analyses as described above or processed for immunofluorescence as previously described (51). Anti-MyoD polyclonal antibody C20 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was used to identify transfected cells, and anti-troponin T antibody JLT-12 (Sigma) was used to quantify the level of differentiation. MyoD antibodies were visualized with biotinylated anti-rabbit antibodies and Texas red-streptavidin (Amersham). Fluorescein-conjugated anti-mouse antibodies were used to detect troponin T antibodies. DNA was stained with Hoechst dye (Sigma).

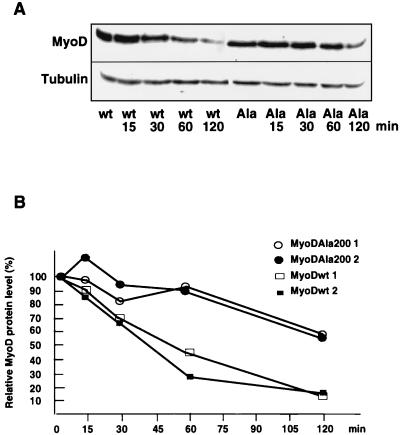

Cycloheximide treatment.

10T1/2 cells were transfected with either pEMSV-MyoD-wt or pEMSV-MyoD-Ala200 in 35-mm-diameter dishes as described above. Transfected cells were treated with cycloheximide (Sigma) at 15 μg/ml for the indicated times and harvested for Western blot analyses. MyoD was stained with anti-MyoD antibody C20 as described above. For each experiment, α-tubulin was used as an internal control. Western blots were scanned and quantified by using ImgCalc sensitivity software (developed by N. J. C. Lamb; details upon request) on a Silicon Graphics Indigo2 Workstation.

RESULTS

Hyperphosphorylation of MyoD in proliferative myoblasts.

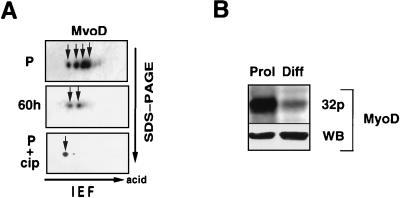

To examine the posttranslational modifications of MyoD during myogenesis, we have analyzed MyoD protein expression in the course of C2.7 differentiation by 2D gel electrophoresis followed by western blotting. As shown in Fig. 1A, four major MyoD isoforms of similar intensities are detected in proliferative myoblasts, with some other minor spots in the more acidic part of the gel. By contrast, only two major spots are visible after 60 h of differentiation, a stage when most of the cells have differentiated into myotubes. To confirm that posttranslational modifications of MyoD involve mainly phosphorylation, we treated nuclear extracts from proliferative myoblasts with CIP and analyzed the mobility of MyoD by 2D gel electrophoresis and western blotting as before. As shown in Fig. 1A, phosphatase treatment resulted in only one major MyoD isoform, which resolved at the basic side of the gel. To confirm that MyoD is more phosphorylated in myoblasts than in myotubes, C2 proliferative myoblasts and myotubes were labeled with [32P]orthophosphate, MyoD was immunoprecipitated and separated by SDS-PAGE, and its phosphorylation was analyzed by autoradiography of the gel. MyoD phosphorylation was higher in myoblasts than in myotubes (Fig. 1B, top); Western blot analysis of the immunoprecipitate shows that the phosphorylated band corresponds to MyoD, and the amounts of immunoprecipitated MyoD were comparable between myoblasts and myotubes (Fig. 1B, bottom).

FIG. 1.

Hyperphosphorylation of MyoD in C2.7 myoblasts. (A) Total cellular proteins were extracted from C2.7 cells and separated by 2D gel electrophoresis. The different isoforms of MyoD (arrows) were detected by Western blot analysis using extracts made from proliferative myoblasts (P) or cells placed for 60 h in differentiation medium or nuclear from extracts from proliferative myoblasts treated with CIP (P+cip). Migrations of the first dimension electrofocusing (IEF) gel (with the acid side indicated) and the second SDS-PAGE dimension are illustrated by arrows. (B) MyoD was immunoprecipitated from [32P]orthophosphate-labeled proliferative (Prol) or differentiated (Diff) C2.7 cells as described in Materials and Methods. MyoD was resolved by SDS-PAGE, its phosphorylation analyzed by autoradiography (32p), and the amount of immunoprecipitated MyoD protein was controlled by Western blot (WB) analysis.

Taken together, these data clearly show that MyoD phosphorylation changes during the course of differentiation of C2 cells, being hyperphosphorylated in myoblasts compared to myotubes.

CDK-dependent phosphorylation of MyoD.

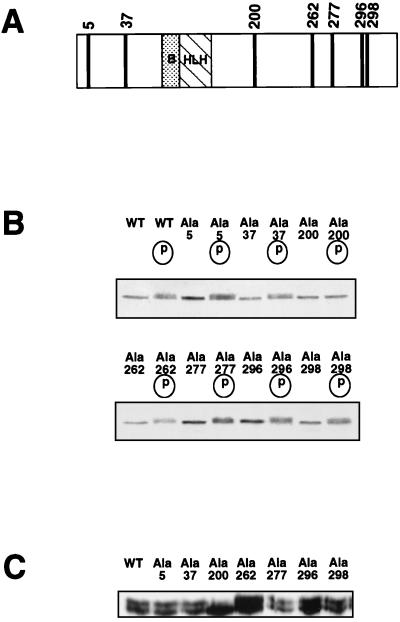

CDKs, a family of kinases implicated throughout the cell cycle, are potentially involved in both phosphorylation of MyoD and inhibition of its activity in myoblasts (16–18, 38, 42, 43). Analysis of the amino acid sequence of MyoD revealed seven putative CDK phosphorylation sites distributed in the NH2- and COOH-terminal regions of the protein outside the bHLH domain (see Fig. 5A and below). As such, MyoD represents a potential target for direct phosphorylation by CDKs.

FIG. 5.

Among the seven potential CDK-dependent phosphorylation sites, mutation of only Ser200 prevents the phosphorylation shift of MyoD. (A) MyoD protein exhibits seven proline-directed sites on its amino acid sequence: Ser5, Ser37, Ser200, Ser262, Ser277, Thr296, and Ser298. Each of the Ser and Thr residues was mutated to Ala as described in Materials and Methods. (B) In vitro-translated 35S-labeled MyoD-wt (WT) and individual Ala mutants of MyoD (Ala5, Ala37, Ala200, Ala262, Ala277, Ala296, and Ala298) were incubated with (circled “p”) or without cdk1-cyclin B. Phosphorylation shifts were visualized after SDS-PAGE. Shown is the autoradiogram of the SDS-PAGE analysis. (C) Western blot analysis of MyoD overexpression in 10T1/2 cells transiently transfected with either MyoD-wt or each of the seven Ala mutants. Shown is the ECL detection of MyoD immunoreactivity.

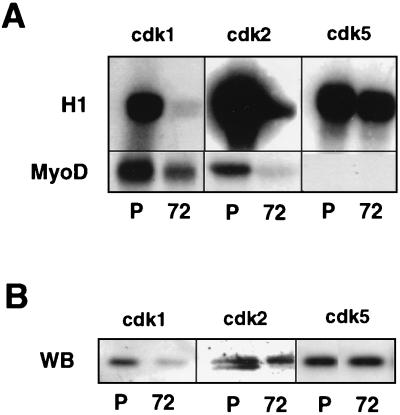

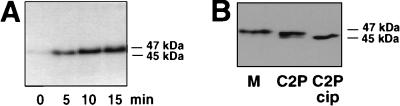

To investigate if MyoD could be phosphorylated in a CDK-dependent manner, cdk1 (also called cdc2) and cdk2 were immunoprecipitated from myoblasts or myotubes and assayed for their activities against MyoD, with histone H1 used as an internal control. Since we have previously shown that cdk5 is a positive regulator of myogenesis, its involvement in MyoD inhibition is unlikely (27); therefore, cdk5 activity was also examined as a control. As shown in Fig. 2A (top), both cdk1 and cdk2 isolated from myoblasts phosphorylate H1, whereas they show little or no H1 kinase activity when immunoprecipitated from myotubes. In contrast, cdk5 H1 kinase activity is detected in both myoblasts and myotubes, in agreement with our previous study (27). With respect to MyoD phosphorylation (Fig. 2A, bottom), both cdk1 and cdk2 display a high kinase activity toward MyoD in myoblasts which is strongly reduced in myotubes, whereas cdk5 shows no MyoD phosphorylation activity in either myoblasts or myotubes. Immunoprecipitation efficiency was controlled by Western blot analysis of the immunoprecipitated CDKs. As shown in Fig. 2B, the loss of kinase activity observed for cdk2 in myotubes correlates with the presence of a single slower-migrating inactive form of cdk2 (15). The level of immunoprecipitated cdk5 is the same in myoblasts and myotubes, and as previously described (27), the cdk1 protein level is significantly decreased in differentiated cells (1). Compared to their H1 kinase activities, cdk1 appeared to phosphorylate MyoD more efficiently than cdk2. To further demonstrate that MyoD could be directly phosphorylated by cdk1, we analyzed recombinant MyoD in an in vitro kinase assay using purified cdk1-cyclin B (purified as dimer from starfish oocytes [24]). A study of the phosphorylation of MyoD revealed that cdk1-cyclin B-purified kinase efficiently phosphorylates MyoD, causing a decrease in its electrophoretic mobility on SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3A). Interestingly, MyoD from proliferative myoblasts migrates as two bands of approximately 45 and 47 kDa (Fig. 3B). The 47-kDa band can be converted to 45 kDa following CIP treatment of C2 nuclear extracts, showing that the slower-migrating form corresponds to hyperphosphorylated MyoD, in agreement with a previous report by Tapscott et al. (49). Because cdk1 is known to be active at the G2/M transition and during mitosis, we also analyzed MyoD phosphorylation in vivo, in mitotic C2 cells collected by mitotic shake from asynchronous myoblasts. As shown in Fig. 3B, only the slower-migrating hyperphosphorylated MyoD is present in mitotic C2 cells.

FIG. 2.

cdk1 and cdk2 from C2 myoblasts phosphorylate efficiently MyoD. (A) cdk1, cdk2, and cdk5 were immunoprecipitated from proliferative (P) and differentiated (72) C2.7 cells and assayed for kinase activity against H1 histone (top panel) and MyoD (bottom panel). Shown are autoradiograms of the different kinase reactions following SDS-PAGE. (B) Western blot (WB) analysis of cdk1, cdk2, and cdk5 after immunoprecipitation from proliferative (P) and differentiated (72) C2.7 cells.

FIG. 3.

Electrophoretic shift of MyoD after phosphorylation by cdk1-cyclin B. (A) Bacterially produced MyoD protein was phosphorylated by purified cdk1-cyclin B kinase for the time indicated. Shown is the autoradiogram from the 32P phosphorylation reaction. Unphosphorylated MyoD migrates as 45-kDa band that shifts to 47 kDa in the course of phosphorylation by cdk1-cyclin B. (B) Western blot showing MyoD migration after SDS-PAGE of mitotic cells extracts (M) and proliferative C2.7 nuclear extracts before (C2P) and after (C2P cip) treatment with CIP.

Together, these results demonstrate that cdk1 (cdc2) and cdk2 isolated from proliferating myoblasts efficiently phosphorylate MyoD, whereas cdk5 does not. Phosphorylation of MyoD by purified cdk1-cyclin B causes a decrease of its electrophoretic mobility similarly to the hyperphosphorylated form of MyoD present in both growing or mitotic C2 myoblasts, further supporting an involvement of this kinase in the phosphorylation of MyoD in proliferative myoblasts.

MyoD is phosphorylated on a CDK site in vivo.

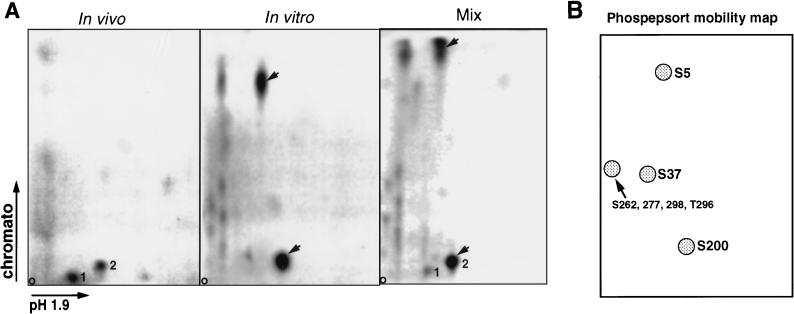

To compare the sites phosphorylated on MyoD in vivo in proliferative myoblasts with those targeted in vitro by purified cdk1-cyclin B and cdk1 or cdk2 immunoprecipitated from myoblasts, we used tryptic digestion of MyoD followed by 2D phosphotryptic peptide mapping. As illustrated in Fig. 4A, two major phosphotryptic peptides (spots 1 and 2 in the left panel) are obtained after digestion of 32P-labeled MyoD immunoprecipitated from proliferating myoblasts. In the case of MyoD phosphorylated by cdk1-cyclin B in vitro, two major phosphotryptic peptides are also resolved (arrowed in the middle panel). We have observed the same pattern when analyzing MyoD phosphorylated in vitro by cdk1 or cdk2 immunoprecipitated from proliferating C2.7 cells (unpublished observations). When in vivo- and in vitro-phosphorylated MyoD tryptic peptides are mixed (right panel), only one of the two peptides resolved in vivo (Spot 2) comigrated with one of the phosphopeptides from cdk1-phosphorylated MyoD (the other major site phosphorylated in vitro was never observed in vivo). To estimate which sites were phosphorylated, we used the PhosPepSort program to obtain a prediction of the mobility map for the tryptic phosphopeptides expected after phosphorylation of the seven proline-directed sites on MyoD (Fig. 4B). As shown in Fig. 4B, the seven sites should lie in four phosphopeptides spanning amino acids (aa) 1 to 9 (Ser5), aa 10 to 41 (Ser37), aa 188 to 202 (Ser200), and aa 258 to 319 (Ser262, Ser277, Ser298, and Thr296). According to the mobility prediction, the two major phosphopeptides obtained after in vitro phosphorylation of MyoD by cdk1 and cdk2 would correspond to phosphorylation of Ser5 and Ser200. Of these two peptides, only one, which is predicted to contain Ser200, is common between in vitro and in vivo maps.

FIG. 4.

Phosphotryptic map analysis of MyoD phosphorylation in C2 myoblasts and following in vitro phosphorylation by cdk1-cyclin B. (A) Phosphorylation sites on MyoD were analyzed by tryptic digestion followed by 2D peptide mapping. The phosphopeptide map for in vivo MyoD phosphorylation (left panel) was obtained after immunoprecipitation of 32P-radiolabeled MyoD from dividing myoblasts. The phosphopeptide map for in vitro-phosphorylated MyoD (middle panel) was performed on bacterially produced MyoD phosphorylated in vitro by cdk1-cyclin B. In vivo and in vitro-phosphorylated MyoD were mixed following tryptic digestion, before 2D analysis (right panel). Numbers 1 and 2 indicate the two major phosphopeptides obtained from MyoD in proliferative myoblasts. The two major phosphopeptides found with MyoD phosphorylated in vitro are pointed to by arrows. (B) Mobility prediction of MyoD tryptic phosphopeptides by using the PhosPepSort program shows the pattern of migration for the four MyoD phosphopeptides that would be generated if all of the seven proline-directed sites present on MyoD were phosphorylated.

This result shows that at least one site phosphorylated in vivo corresponds to a site phosphorylated by both cdk1 and cdk2 in vitro that most likely contains serine 200.

Ser200 is a major site of CDK-dependent phosphorylation.

To determine precisely the site for in vivo CDK-dependent phosphorylation of MyoD, we mutated each putative CDK site in MyoD. As shown in Fig. 5A, seven putative sites are distributed in the NH2 and COOH ends of MyoD, at positions Ser5, Ser37, Ser200, Ser262, Ser277, Thr296, and Ser298. Seven mutants were generated by site-directed mutagenesis replacing the amino acid serine or threonine by a nonphosphorylatable alanine residue and named MyoD-Ala5 to MyoD-Ala298.

Wild-type MyoD and its seven mutants were translated in the presence of [35S]methionine in rabbit reticulocyte lysate and subjected to phosphorylation by purified cdk1-cyclin B. Phosphorylated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by autoradiography. As shown in Fig. 5B, phosphorylation of MyoD-wt by cdk1-cyclin B resulted in a decrease of its electrophoretic mobility. This slower-migrating form was also observed after phosphorylation of all but one (MyoD-Ala200) of the MyoD mutants, indicating that phosphorylation of Ser200 is responsible for the shift in mobility seen after the phosphorylation of MyoD by cdk1-cyclin B in vitro. To investigate if Ser200 is also responsible for the shift observed in vivo, expression vectors coding for MyoD-wt and MyoD mutants were transfected into 10T1/2 cells. Transfected cells were grown for 36 h in proliferative medium, and MyoD expression was monitored by Western blotting of whole-cell extracts. As shown in Fig. 5C, MyoD is detected as two bands following transfection of MyoD-wt and all but one of the mutants. Among the seven mutants, only MyoD-Ala200 is resolved as a single band which migrates as the fast-migrating hypophosphorylated form of MyoD found in both MyoD-wt-transfected 10T1/2 and C2 myoblasts.

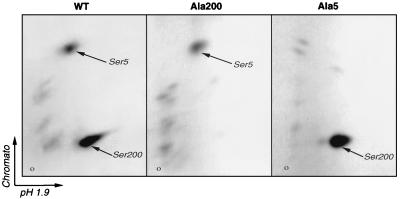

By 2D tryptic mapping (Fig. 4), we previously predicted that Ser200 was most likely the target of cdk1 and cdk2 phosphorylation in vitro and in vivo and that Ser5 could be phosphorylated in vitro but not in vivo. To confirm this prediction, mutant forms of MyoD (MyoD-Ala200 and MyoD-Ala5) were produced in bacteria, purified, and analyzed by 2D tryptic mapping following in vitro phosphorylation by cdk1-cyclin B, as previously described for the wild-type protein. For comparison, the same experiment was carried out on MyoD-wt. As shown in Fig. 6, two major phosphopeptides, S5 and S200 (predicted to contain Ser5 and Ser200, respectively), are obtained after in vitro phosphorylation of MyoD-wt by cdk1-cyclin B. MyoD-Ala200 is not phosphorylated on the S200 peptide, whereas MyoD-Ala5 is no longer phosphorylated on the Ser5 peptide. These results confirm that MyoD-wt can be phosphorylated by cdk1-cyclin B in vitro on two sites, Ser5 and Ser200. As only the S200 peptide is common between in vitro and in vivo maps (Fig. 4), Ser200 is the only CDK site phosphorylated on MyoD in vivo.

FIG. 6.

Phosphotryptic map analysis of MyoD-Ala5 and MyoD-Ala200 following in vitro phosphorylation by cdk1-cyclin B. Phosphorylation sites on MyoD were analyzed by tryptic digestion followed by 2D peptide mapping. Phosphopeptide maps were obtained for bacterially produced MyoD-wt (left panel), MyoD-Ala200 (middle panel), and MyoD-Ala5 (right panel) phosphorylated in vitro by cdk1-cyclin B. The two major phosphopeptides found with MyoD-wt phosphorylated in vitro are pointed to by arrows labeled Ser5 and Ser200.

Together, these results identify Ser200 as a major site of cdk1- and cdk2-dependent phosphorylation of MyoD both in vitro and in vivo.

MyoD-Ala200 shows enhanced muscle gene-specific transactivating activity.

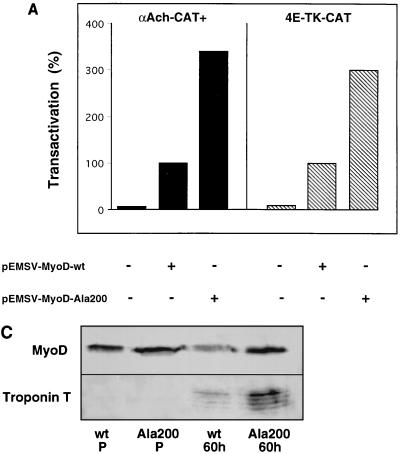

To assess the consequence of Ser200 phosphorylation on MyoD activity, we initially compared the abilities of MyoD-wt and MyoD-Ala200 to transactivate muscle-specific gene expression. Plasmids expressing either MyoD-wt or MyoD-Ala200 were cotransfected with a CAT reporter gene containing the acetylcholine receptor α-subunit promoter (pαAch-CAT+) in 10T1/2 cells. Transfected cells were kept in proliferative medium for 36 h, and transactivation of the reporter gene estimated by CAT assay. In each case, plasmid pCMV-βgal was cotransfected as an internal control for transfection efficiency. As expected (Fig. 7A), the low basal activity of the wild-type reporter gene was highly enhanced by MyoD-wt; moreover, MyoD-Ala200 further increased the level of CAT reporter activity threefold over that obtained with MyoD-wt. Such an increase was not observed with any of the other MyoD mutants (unpublished observations). To demonstrate that this increased transactivation activity of MyoD-Ala200 required the E boxes, we performed the same experiment with a mutant form of the reporter, pαAchmutCAT+, where the E boxes had been mutated (35). Neither MyoD-wt nor MyoD-Ala200 could transactivate the reporter plasmid pαAchmutCAT+ (unpublished observations). We also used plasmid p4E-TK-CAT, which contains a simplified enhancer comprising four tandem copies of the E-box sequence (from the muscle creatine kinase gene enhancer) upstream of the minimal thymidine kinase promoter and, as a control, plasmid pTK-CAT, devoid of E boxes. As shown in Fig. 7A, MyoD-Ala200 was again threefold more efficient than MyoD-wt in transactivating CAT expression from the p4E-TK-CAT construct, which confirms the effect observed with pαAch-CAT.

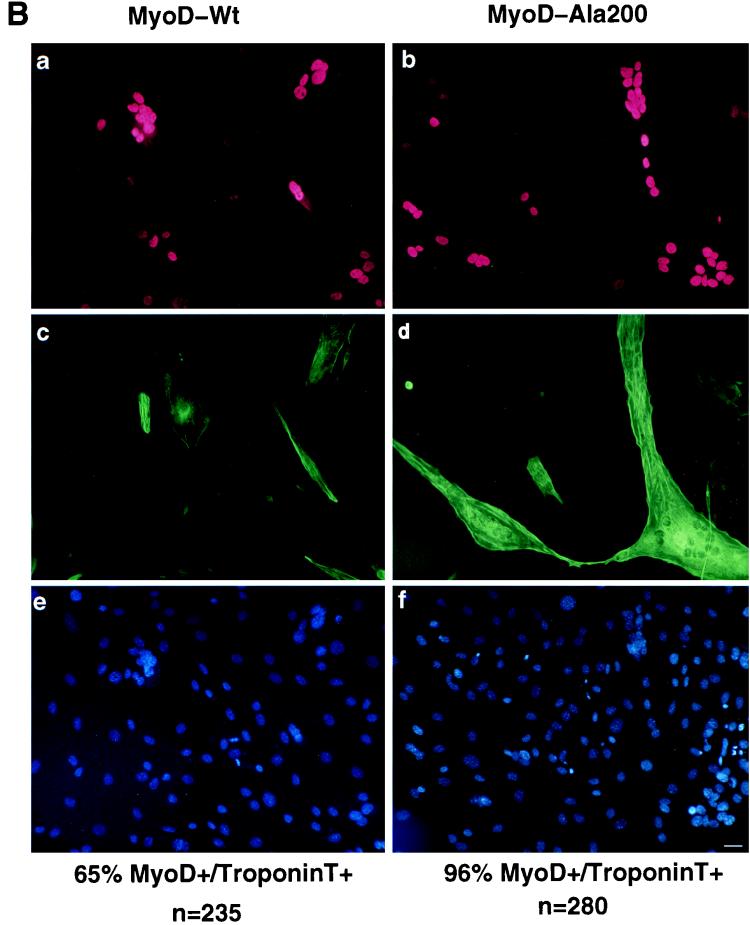

FIG. 7.

MyoD-Ala200 displays enhanced transactivating and myogenic activities. (A) pαAch-CAT+ and p4E-TK-CAT reporter constructs were cotransfected in 10T1/2 cells with either pEMSV or encoding plasmid pEMSV-MyoD-wt or pEMSV-MyoD-Ala200 and pCMV-βgal. Transfected cells were grown for 36 h in DMEM containing 10% FCS, and CAT activity was measured and corrected with respect to β-galactosidase activity. CAT activities are expressed relative to that of each reporter plasmid transfected with pEMSV-MyoD, set as 100%. (B) 10T1/2 were transfected with either pEMSV-MyoD-wt or pEMSV-MyoD-Ala200 and placed in differentiation medium (DMEM containing 2% FCS) for 60 h. Cells were fixed and stained for both MyoD and troponin T. Shown are the extents of myogenic conversion of 10T1/2 by MyoD-wt (left panels) and MyoD Ala200 (right panels) with staining for MyoD expression (a and b), troponin T expression (c and d), and DNA staining (e and f). Bar, 10 μm. The average percentages of cells expressing MyoD-wt or MyoD-Ala200 that coexpressed troponin T were calculated from two different experiments and are indicated in the bottom. The total numbers of MyoD-positive cells counted were 235 for MyoD-wt and 280 for MyoD-Ala200. (C) 10T1/2 cells were transfected with either pEMSV-MyoD-wt or pEMSV-MyoD-Ala200 as described above. Transfected cells were grown in proliferative medium (DMEM containing 10% FCS) for 24 h (P) and placed in differentiation medium for 60 h (60h). Cells were collected either before (P) or after (60h) myogenic conversion and analyzed by western blotting for MyoD and troponin T expression.

Taken together, these results show that mutation of Ser200 results in an increased ability of MyoD to transactivate muscle-specific gene expression through the E box. Although a threefold difference in activity may seem unsufficient to ascribe a predominant role of MyoD Ser200 phosphorylation in controlling its activity, it should be noted that this value is an underestimate since only 50% of MyoD-wt is phosphorylated when overexpressed, as clearly shown in Fig. 5C.

MyoD-Ala200 promotes complete myogenic conversion of 10T1/2 fibroblasts to muscle cells.

Since mutation of MyoD serine 200 to alanine increased its capacity to transactivate muscle-specific gene expression, we next compared the abilities of MyoD-wt and MyoD-Ala200 proteins to trigger myogenic conversion. 10T1/2 cells were transfected with expression vectors coding for either MyoD-wt or MyoD-Ala200. Transfected cells were placed in differentiation medium for 60 h and analyzed by immunofluorescence for expression of MyoD and troponin T as a differentiation marker. The efficiency of myogenic conversion was estimated as the percentage of cells expressing MyoD that also expressed troponin T. The immunofluorescence presented in Fig. 7B reveal that MyoD-Ala200 was significantly more efficient than MyoD-wt in converting 10T1/2 cells to myotubes. After 60 h of differentiation (Fig. 7B), nearly all MyoD-Ala200-expressing cells had differentiated into troponin T-positive myotubes whereas 35% of MyoD-wt-expressing cells remained negative for troponin T. A clear difference in activity between the two MyoD proteins was also observed at the phenotypic level. As shown in Fig. 7B, MyoD-Ala200-expressing cells formed many giant interconnected myotubes. We never observed this extent of differentiation with the wild-type protein even if conversion was allowed for up to 5 days. To accurately quantify the increase in myogenic conversion ability of MyoD-Ala200 versus MyoD-wt, conversions were done as before but MyoD and troponin T expression levels were analyzed by western blotting. As shown in Fig. 7C, after 24 h (wt P and Ala200 P), similar levels of MyoD-wt and MyoD-Ala200 are expressed (upper panel), with no detactable troponin T expression (lower panel). After 60 h in differentiation medium (wt 60h and Ala200 60h), troponin T is expressed (lower panel) and is present at levels fivefold higher in MyoD-Ala200- than MyoD-wt-overexpressing cells. It is worth noting that in these culture conditions, MyoD-wt protein level appears to be about twofold lower than the MyoD-Ala200 level (upper panel, wt 60h and Ala200 60h), probably as a result of differences in protein half-life (see below).

Taken together, these data show that the muscle-specific transcription factor MyoD is phosphorylated in vivo on Ser200 by a CDK. This phosphorylation event appears to restrict MyoD activity since mutation of serine 200 to a nonphosphorylatable alanine residue significantly enhances both the transcriptional activity of MyoD and the ability of MyoD to induce myogenic conversion of nonmuscle cells.

Ser200 phosphorylation regulates MyoD protein turnover.

Because phosphorylation by CDKs has been involved in the targeted degradation of several factors such as p27 (53), we next investigated a potential link between CDK-dependent phosphorylation of MyoD and its specific degradation. If phosphorylation of Ser200 is implicated in MyoD degradation, mutation of Ser200 would be expected to increase the half-life of MyoD. To test this hypothesis, we transfected MyoD-wt and MyoD-Ala200 in 10T1/2 cells and determined the half-life of MyoD following cycloheximide treatment (Fig. 8A). The half-life of MyoD-wt was found to be about 40 min (average of values obtained from two different experiments [Fig. 8B]), in agreement with a previous report from Thayer et al. (50). Expression of α-tubulin, a stable protein, was not modified 2 h after cycloheximide addition. By contrast, MyoD-Ala200 was found to be more stable than MyoD-wt, with an half-life extended to 140 min.

FIG. 8.

Impeding MyoD Ser200 phosphorylation stabilizes the protein. (A) 10T1/2 cells were transfected with either pEMSV-MyoD-wt or pEMSV-MyoD-Ala200 and grown for 24 h in proliferative medium before addition of cycloheximide (15 μg/ml) to the medium for 0, 15, 30, 60, or 120 min. MyoD and α-tubulin protein levels were determined by immunoblot analysis at the indicated times after cycloheximide addition. (B) Immunoblots were quantified by densitometric scanning, and MyoD protein levels (corrected with respect to tubulin expression) were expressed relative to that observed before cycloheximide treatment, set as 100%.

DISCUSSION

An essential step during myogenesis is the reorientation of the proliferative cell cycle toward differentiation processes in which the transcription factor MyoD plays clearly a critical role. Although overexpression of MyoD can drive nontransformed fibroblasts into differentiation (8), myoblasts proliferate efficiently while expressing MyoD. A mechanism other than regulation of MyoD expression is therefore required to explain why myoblasts do not enter differentiation. In this report, we demonstrate that phosphorylation plays an active role in preventing differentiation through a negative effect on MyoD activity. We observe that MyoD phosphorylation is high in myoblasts and reduced during differentiation and show for the first time that MyoD is a direct substrate for phosphorylation by CDKs. Comparative peptide mapping combined with site-directed mutagenesis show that MyoD is phosphorylated by cdk1 (cdc2) and cdk2 on Ser200 both in vitro and in proliferating myoblasts. Indeed, substitution of Ser200 by an alanine (MyoD-Ala200) prevents the appearance of hyperphosphorylated MyoD after either its phosphorylation by cdk1-cyclin B in vitro or overexpression in 10T1/2 cells. The phosphorylation of this site by CDKs is clearly inhibitory to MyoD function, as demonstrated by the greater myogenic activity of MyoD-Ala200 than of MyoD-wt.

cdk1 and cdk2 phosphorylate MyoD on serine 200 in proliferative myoblasts.

Our data show that the kinases responsible for the phosphorylation of Ser200 on MyoD in proliferative myoblasts include the mitotic activator kinase cdk1-cyclin B and cdk2-cyclin A/E kinase, which is present and active from mid-G1 until mitosis. Overexpression of cyclin D1 was shown to promote hyperphosphorylation of MyoD (42, 43), suggesting that cdk4-cyclin D1 could directly phosphorylate MyoD. However, in contrast to the efficient phosphorylation of MyoD by cdk2 and cdk1 in vitro, we have been unable to observe an effective phosphorylation of MyoD in assays using immunoprecipitated cdk4 from C2 myoblasts (unpublished observations). This observation is in agreement with that of Skapek et al. (43), who found that baculovirus-produced cdk4-cyclin D1 fails to phosphorylate MyoD. It thus appears that the hyperphosphorylation of MyoD observed after cyclin D1 overexpression may be the result of an indirect effect rather than a direct cdk4-dependent phosphorylation of MyoD. cdk1- and cdk2-dependent phosphorylation requires the Ser/Thr-Pro (S/T-P) cluster to be followed immediately by a basic residue (Lys/Arg [46]), which is the case for the motif containing Ser200 that we have identified on MyoD. Of the 6 other S/T-P sites present on MyoD, only serine 5 is also a potential site for phosphorylation by cdk1 and cdk2. Although this site is phosphorylated in vitro, as shown by phosphopeptide map analysis (Fig. 4 and 6), it was never found phosphorylated in vivo in C2.7 myoblasts (Fig. 4), and mutation of Ser5 to alanine did not cause any significant effect on MyoD-dependent transcriptional activation of a reporter gene containing the acetylcholine receptor promoter (unpublished observations). Ser200 is thus the only cdk1- and cdk2-dependent site used in vivo. It is also the only site responsible for the electrophoretic shift in mobility seen when MyoD is phosphorylated either in vitro or in vivo. It is to be noted that the sequence immediately surrounding and including Ser200 is highly conserved in MyoD from many different species (unpublished observations). We cannot rule out the possibility that phosphorylation of Ser200 is a prerequisite for phosphorylation of MyoD at other sites. In this context, kinases other than CDKs may also phosphorylate MyoD and contribute to its inhibition in proliferative myoblasts. In addition to Ser200, a second phosphopeptide is clearly observed by 2D tryptic mapping of MyoD isolated from proliferative myoblasts. It does not correspond to any of the peptides resolved after in vitro phosphorylation of MyoD by cdk1-cyclin B (Fig. 4), implying that a kinase other than cdk1 or cdk2 also phosphorylates MyoD in vivo. PKA and PKC have been implied to negatively regulate myogenic factors, although this regulation appeared to be indirect in the case of PKA (28, 55). According to the PhosPepSort mobility analysis shown in Fig. 4, it is unlikely that PKC is responsible for this MyoD phosphorylation in myoblasts. Indeed, the predicted map of MyoD-Thr 115 phosphopeptide (equivalent to the site phosphorylated by PKC on myogenin [28]) does not correspond to the second tryptic phosphopeptide observed in vivo (spot 1 in Fig 4). The kinase responsible for this phosphopeptide remains to be identified.

Among the members of the MyoD gene family, myogenin has been shown to be phosphorylated on Ser47 and Ser170, two serine residues which lie in sequences similar to CDK-dependent phosphorylation sites (57). These two sites have indeed been shown to be phosphorylated by cdk1 in vitro (20). However, the significance of such phosphorylation is unclear. The absence of this myogenic factor in proliferating myoblasts argues against a cell cycle-dependent regulation of myogenin. In addition, by 2D gel analysis, we showed that in contrast to MyoD, the phosphorylation status of myogenin does not undergo dramatic changes during differentiation of C2.7 cells (unpublished observations). Thus, the CDK-dependent phosphorylation of MyoD Ser200 we have shown must play an unique role, one that cannot be extended to myogenin, in the regulation of MyoD activity. During the preparation of this paper, Song et al. (45) reported that Ser200 is required for MyoD hyperphosphorylation. However, they did not investigate the nature of the protein kinase(s) responsible for MyoD phosphorylation or if such phosphorylation of MyoD occurs in vivo in myoblasts. In this report, we demonstrated that cdk1 and cdk2 are the protein kinases involved in the direct phosphorylation of MyoD Ser200 in proliferative myoblasts.

Impeding Ser200 phosphorylation enhances MyoD activity.

The mutant MyoD-Ala200 was more efficient than MyoD-wt in converting 10T1/2 cells to muscle cells. This augmentation was correlated to an enhanced ability of MyoD-Ala200 (about threefold higher than that of MyoD-wt) to transactivate muscle gene expression via the E box (Fig. 7A). However, this increased transactivating capability was not linked to significant alteration in MyoD DNA binding affinity. Indeed, by band shift analysis, we observed that phosphorylation of MyoD by cdk1-cyclin B did not alter the binding of MyoD homodimer to the E-box and had marginal effects on MyoD-E12 DNA binding (unpublished observations). That DNA-binding and transcriptional activities of myogenic factors are not necessarily correlated has been reported in previously. For instance, in myoblasts blocked from differentiating by transforming growth factor β, myogenic factors appear to retain DNA-binding activity without activating muscle gene transcription (5). Interestingly, MyoD-containing complexes capable of binding to an E box are observable in nuclear extracts from both proliferating myoblasts and differentiated myotubes (reference 41 and our unpublished observations). It thus appears that the transcriptional activity of MyoD is not necessarily reflected by its capacity to bind to DNA. Because DNA-binding activity was not the mechanism by which phosphorylation of MyoD Serine 200 could control MyoD activity, we have compared the stabilities of MyoD-wt and MyoD-Ala200. We found, in agreement with a recent report from Song et al. (45), that MyoD-Ala200 was more stable than MyoD-wt, suggesting that phosphorylation of Ser200 decreases MyoD activity by reducing its half-life. This phosphorylation seems to be required for targeting MyoD to the ubiquitin pathway (45). A rapid turnover of MyoD may allow a fine regulation of its activity in myoblasts. High-level expression of MyoD obtained by ectopic expression into nonmuscle cells is known to stop cell cycle progression before S phase, allowing cells to engage into the differentiation process (7, 47). Controlled degradation of MyoD may be necessary to prevent MyoD from reaching a threshold that can interfere with normal cell cycle events before myoblasts have received the appropriate signal to differentiate. By isolating C2 cells that have lost MyoD expression, Horwitz (22) found that the autoactivation loop of MyoD is tightly linked to protein stability. In addition, the reduced half-life that we observed for phosphorylated MyoD may result from a change in MyoD-associated protein. Ser200 phosphorylation may reduce the association of MyoD with partners such as pRb (14), MEF-2 proteins (29), the coactivator p300 (11, 37), or proteins such as Id. cdk2-dependent phosphorylation has been shown to change the interaction specificity of the HLH protein Id3 (10). CDK-dependent phosphorylation has also been shown to change the interaction between the transcription factor E2F and pRB (21, 44). In a similar way, free MyoD could be more sensitive to degradation. Gerber et al. (13) have recently shown that MyoD, in addition to being able to bind DNA and activate muscle-specific gene expression, can remodel chromatin at binding sites in muscle gene regulatory regions and activate transcription at previously silent loci. This ability of MyoD to activate genes within inactive chromatin mapped to a cysteine- and histidine-rich region of the amino terminus and a region extending from aa 218 to 269 in the carboxy terminus of MyoD. Interestingly, deletion of a region between aa 170 and 209 (that includes Ser200) increased the ability of MyoD to initiate transcription of endogenous genes, implying a repressive role of this region in chromatin remodeling by MyoD. It is tempting to hypothesize that in addition to modulating MyoD half-life and transactivating ability, Ser200 phosphorylation may cause conformational changes of MyoD and thereby modulate intra- or intermolecular interactions involved in remodeling chromatin.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jacques Demaille for his continued support. We thank P. Dias for the generous gift of monoclonal anti-MyoD antibody, Hal Weintraub for coding plasmids p4E-TK-CAT and pTK-CAT, and Jacques Piette for plasmids pαAch-CAT+ and pαAchmutCAT+.

This work was supported by grants from Association Francaise contre les Myopathies and Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer (contract 1344 and a fellowship to M.K.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Akhurst R J, Flavin N B, Worden J, Lee M G. Intracellular localisation and expression of mammalian CDC2 protein during myogenic differentiation. Differentiation. 1989;40:36–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1989.tb00811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrés V, Walsh K. Myogenin expression, cell cycle withdrawal, and phenotypic differentiation are temporally separable events that precede cell fusion upon myogenesis. J Cell Biol. 1996;132:657–666. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.4.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benezra R, Davis R L, Lockshon D, Turner D L, Weintraub H. The protein Id: a negative regulator of helix-loop-helix DNA binding proteins. Cell. 1990;61:49–59. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90214-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braun J, Buschhausen-Denken G, Bober E, Tannich E, Arnold H H. A novel human muscle factor related to but distinct from MyoD1 induces myogenic conversion in 10T1/2 fibroblasts. EMBO J. 1989;8:701–709. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb03429.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brennan T J, Edmonson D G, Olson E N. Transforming growth factor beta represses the actions of myogenin through a mechanism independent of DNA binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:3822–3826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.9.3822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choi J, Costa M L, Mermelstein C S, Chagas C, Holtzer S, Holtzer H. MyoD converts primary dermal fibroblasts, chondroblasts, smooth muscle, and retinal pigmented epithelial cells into striated mononucleated myoblasts and multinucleated myotubes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7988–7992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.20.7988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crescenzi M, Fleming T P, Lassar A B, Weintraub H, Aaronson S A. MyoD induces growth arrest independent of differentiation in normal and transformed cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:8442–8446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis R L, Weintraub H, Lassar A B. Expression of a single transfected cDNA converts fibroblasts to myoblasts. Cell. 1987;51:987–1000. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90585-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davis R L, Cheng P, Lassar A B, Weintraub H. The MyoD DNA binding domain contains a recognition code for muscle specific gene activation. Cell. 1990;60:733–746. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90088-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deed R W, Hara E, Atherton G T, Peters G, Norton J D. Regulation of Id3 cell cycle function by cdk2-dependent phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6815–6821. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.12.6815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eckner R, Yao T P, Oldread E, Livingston D. Interaction and functional collaboration of p300/CBP and bHLH proteins in muscle and B-cell differentiation. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2478–2490. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.19.2478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edmonson D G, Olson E N. A gene with homology to the myc simulatory region of MyoD1 is expressed during myogenesis and is sufficient to activate the muscle differentiation program. Genes Dev. 1989;3:628–640. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.5.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gerber A N, Klesert T R, Bergstrom D A, Tapscott S J. Two domains of MyoD mediate transcriptional activation of genes in repressive chromatin: a mechanism for lineage determination in myogenesis. Genes Dev. 1997;11:436–450. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.4.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gu W, Schneider J W, Condorelly G. Interaction of myogenic factors and the retinoblastoma protein mediates muscle cell commitment and differentiation. Cell. 1993;72:309–324. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90110-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gu Y, Rosenblatt J, Morgan D. Cell cycle regulation of CDK2 activity by phosphorylation of Thr 160 and Tyr 15. EMBO J. 1992;11:3995–4005. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05493.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo K, Wang J, Andres V, Smith R C, Walsh K. MyoD-induced expression of p21 inhibits cyclin-dependent kinase activity upon myocyte terminal differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:3823–3829. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.7.3823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo K, Walsh K. Inhibition of myogenesis by multiple cyclin-cdk complexes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:791–797. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Halevy O, Nowitch B G, Spicer D B, Skapek S X, Rhee J, Hannon G, Beach D, Lassar A B. Correlation of terminal cell cycle arrest of skeletal muscle with induction of p21 by MyoD. Science. 1995;267:1018–1021. doi: 10.1126/science.7863327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardy S, Kong Y, Konieczny S F. Fibroblast growth factor inhibits MRF4 activity independently of the phosphorylation status of a conserved threonine residue within the DNA-binding domain. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:5943–5956. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.10.5943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hashimoto N, Ogashiwa M, Okumura E, Endo T, Iwashita S, Kishimoto T. Phosphorylation of a proline-directed kinase motif is responsible for structural changes in myogenin. FEBS Lett. 1994;352:236–242. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00964-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Helin K. Regulation of cell proliferation by the E2F transcription factors. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998;8:28–35. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horwitz M. Hypermethylated myoblasts specifically deficient in MyoD autoactivation as a consequence of instability of MyoD. Exp Cell Res. 1996;226:170–182. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hunter T, Karin M. The regulation of transcription by phosphorylation. Cell. 1992;70:375–387. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Labbé J C, Cavadore J C, Dorée M. M phase specific cdc2 kinase: preparation from starfish oocytes and properties. Methods Enzymol. 1991;200:291–301. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)00147-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24a.Lamb, N. 6 January 1999, posting date. [Online.] PhosPepSort program. IGH, CNRS, Montpellier, France. http://www.genestream.org/phospepsort. [12 February 1999, last date accessed.]

- 25.Lassar A B, Davis R L, Wright W E, Kadesch T, Murr C, Voronova A, Baltimore D, Weintraub H. Functional activity of myogenic HLH proteins requires hetero-oligomerization with E12/E47-like proteins in vivo. Cell. 1991;66:305–315. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90620-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lassar A B, Skapek S X, Novitch B. Regulatory mechanisms that coordinate skeletal muscle differentiation and cell cycle withdrawal. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1994;6:788–794. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lazaro J B, Kitzmann M, Poul M A, Vandromme M, Fernandez A, Lamb N J C. Cyclin dependent kinase 5, cdk5, is a positive regulator of myogenesis in mouse C2 cells. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:1251–1260. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.10.1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li T, Zhon J, James G, Heller-Harrison R, Czoch M P, Olson E N. FGF inactivates myogenic helix-loop-helix proteins through phosphorylation of a conserved protein kinase C site in their DNA-binding domains. Cell. 1992;71:1181–1194. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Molkentin J D, Black B L, Martin J F, Olson E N. Cooperative activation of muscle gene expression by MEF2 and myogenic bHLH proteins. Cell. 1995;83:1125–1136. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murre C, McCaw Schonleber P, Vaessin H, Caudy M, Jan L Y, Jan T N, Cabrera C V, Buskin J N, Hauschka S D, Lassar A B, Weintraub H, Baltimore D. Interaction between heterologous helix-loop-helix proteins generate complexes that bind specifically to a common DNA sequence. Cell. 1989;58:537–544. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90434-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nielsen D A, Chang T C, Shapiro D J. A highly sensitive, mixed-phase assay for chloramphenicol acetyl transferase activity in transfected cells. Anal Biochem. 1989;179:19–23. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nurse P. Ordering S phase and M phase in the cell cycle. Cell. 1994;79:547–550. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90539-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O’Farrell P H. High resolution two-dimensional electrophoresis of proteins. J Biol Chem. 1975;250:4007–4021. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olson E N, Sternberg E, Hu J S, Spizz G, Wilcox C. Regulation of myogenic differentiation by type beta transforming growth factor. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:1799–1805. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.5.1799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Piette J. Two adjacent MyoD1-binding sites regulate expression of the acetyl choline receptor α-subunit gene. Nature. 1990;345:353–355. doi: 10.1038/345353a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pinset C, Montarras D, Chenevert J, Minty A, Barton P, Laurent C, Gros F. Control of myogenesis in the mouse myogenic C2 cell line by medium composition and by insulin: characterisation of permissive and inducible C2 myoblasts. Differentiation. 1988;38:28–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1988.tb00588.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Puri P L, Avantaggiati M L, Balsano C, Sang N, Graessmann A, Giordano A, Levrero M. p300 is required for MyoD-dependent cell cycle arrest and muscle-specific gene transcription. EMBO J. 1997;16:369–383. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.2.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rao S S, Chu C, Kohtz D S. Ectopic expression of cyclin D1 prevents activation of gene transcription by myogenic basic-helix-loop-helix regulators. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:5259–5267. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.8.5259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rhodes S J, Konbeczny S F. Identification of MRF4, a new member of the muscle regulatory factor gene family. Genes Dev. 1989;9:2050–2061. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.12b.2050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sherr C J. G1 phase progression: cycling on cue. Cell. 1994;79:551–555. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90540-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simon A M, Burden S J. An E-box mediates activation and repression of the acetylcholine receptor δ-subunit gene during myogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:5133–5140. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.9.5133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skapek S X, Rhee J, Spicer D B, Lassar A B. Inhibition of myogenic differentiation in proliferating myoblasts by cyclin D1-dependent kinase. Science. 1995;267:1022–1024. doi: 10.1126/science.7863328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Skapek S X, Rhee J, Kim P S, Novitch B G, Lassar A B. Cyclin D1 mediated inhibition of muscle gene expression via a mechanism that is independent of pRB hyperphosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:7043–7053. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.12.7043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Slansky J F, Farnham P J. Introduction to the E2F family: protein structure and gene regulation. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;208:1–30. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-79910-5_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Song A, Wang Q, Goebl M G, Harrington M A. Phosphorylation of nuclear MyoD is required for its rapid degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4994–4999. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.9.4994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Songyang Z, Blechner S, Hoagland N, Hoekstra M F, Piwnica-Worms H, Cantley L C. Use of an oriented peptide library to determine the optimal substrates of protein kinases. Curr Biol. 1994;4:973–982. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sorrentino V, Pepperkok R, Davis R L, Ansorge W, Pilipson L. Cell proliferation inhibited by MyoD1 independently of myogenic differentiation. Nature. 1990;345:813–815. doi: 10.1038/345813a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Spizz G, Roman D, Strauss A, Olson E N. Serum and fibroblast growth factor inhibit myogenic differentiation through a mechanism dependent on protein synthesis and independent of cell proliferation. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:9483–9488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tapscott S J, Davis R J, Thayer M J, Cheng P, Weintraub H, Lassar A B. MyoD1: a nuclear phosphoprotein requiring a myc homology region to convert fibroblasts to myoblasts. Science. 1988;242:405–411. doi: 10.1126/science.3175662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thayer M J, Tapscott S J, Davis R L, Wright W E, Lassar A B, Weintraub H. Positive autoregulation of the myogenic determination gene MyoD1. Cell. 1989;58:241–248. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90838-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vandromme M, Gauthier-Rouviere C, Carnac G, Lamb N J C, Fernandez A. Serum response factor p67SRF is expressed and required during myogenic differentiation of both C2 and L6 muscle cell lines. J Cell Biol. 1992;118:1489–1500. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.6.1489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vandromme M, Carnac G, Gauthier-Rouviere C, Fesquet D, Lamb N J C, Fernandez A. Nuclear import of the myogenic factor MyoD requires cAMP-dependent protein kinase activity but not the direct phosphorylation of MyoD. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:613–620. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.2.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vlach J, Hennecke S, Amati B. Phosphorylation-dependent degradation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27. Genes Dev. 1997;16:5334–5344. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.17.5334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weintraub H, Davis R, Lockshon D, Lassar A. MyoD binds cooperatively to two sites in a target enhancer sequence: occupancy of two sites is required for activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5623–5627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Winter B, Braun T, Arnold H H. cAMP-dependent protein kinase represses myogenic differentiation and the activity of the muscle-specific helix-loop-helix transcription factors Myf-5 and MyoD. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:9869–9878. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wright W E, Sassoon D A, Lin W K. Myogenin, a factor regulating myogenesis has a domain homologous to MyoD. Cell. 1989;56:607–617. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90583-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhou J, Olson E N. Dimerization through the helix-loop-helix motif enhances phosphorylation of the transcription activation domains of myogenin. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:6232–6243. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.9.6232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]