Key Points

Question

Are emergency department encounters among youth with suicidal thoughts or behaviors higher during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Findings

In this cross-sectional study, the incidence rates of suicide-related emergency department encounters among youth in 2020 were comparable with 2019 incidence rates except for a decrease in March to May 2020 vs the same period in 2019 and an increase among girls in June through December 2020 vs the same period in 2019. Youth with no previously documented mental health treatment had more visits in September to December 2020 compared with this period in 2019.

Meaning

The COVID-19 pandemic may worsen mental health for some groups of youth; emergency department–based interventions may support this population.

This cross-sectional study characterizes population-level and relative change in suicide-related emergency department encounters among youth during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with 2019.

Abstract

Importance

Population-level reports of suicide-related emergency department (ED) encounters among youth during the COVID-19 pandemic are lacking, along with youth characteristics and preexisting psychiatric service use.

Objective

To characterize population-level and relative change in suicide-related ED encounters among youth during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with 2019.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cross-sectional study evaluated ED encounters in 2019 and 2020 at Kaiser Permanente Northern California—a large, integrated, community-based health system. Youth aged 5 to 17 years who presented to the ED with suicidal thoughts or behaviors were included.

Exposure

The COVID-19 pandemic.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Population-level incidence rate ratios (IRRs) and percent relative effects for suicide-related ED encounters as defined by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention–recommended International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) codes in 4 periods in 2020 compared with the same periods in 2019.

Results

There were 2123 youth with suicide-related ED encounters in 2020 compared with 2339 in 2019. In the 2020 group, 1483 individuals (69.9%) were female and 1798 (84.7%) were aged 13 to 17 years. In the 2019 group, 1542 (65.9%) were female, and 1998 (85.4%) were aged 13 to 17 years. Suicide-related ED encounter incidence rates were significantly lower in March through May 2020 compared with this period in 2019 (IRR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.51-0.63; P < .001), then returned to prepandemic levels. However, suicide-related ED visits among female youth from June 1 to August 31, 2020, and September 1 through December 15, 2020, were significantly higher than in the corresponding months in 2019 (IRR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.04-1.35; P = .04 and IRR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.11-1.35; P < .001, respectively), while suicide-related ED visits for male youth decreased from September 1 through December 15, 2020 (IRR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.69 to 0.94). Youth with no history of outpatient mental health or suicide encounters (129.4%; 95% CI, 41.0-217.8) and those with comorbid psychiatric conditions documented at the ED encounter (6.7%; 95% CI, 1.0-12.3) had a higher risk of presenting with suicide-related problems from September to December 2020 vs the same period in 2019.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cross-sectional study of youth experiencing suicidal thoughts and behaviors, suicide-related presentations to the ED initially decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic, likely owing to shelter-in-place orders, then were similar to 2019 levels. However, a greater number of female youth, youth with no psychiatric history, and youth with psychiatric diagnoses at the time of the ED encounter presented for suicide-related concerns during the pandemic, suggesting these may be vulnerable groups in need of further interventions. Adjustments in care may be warranted to accommodate these groups during periods of crisis.

Introduction

Suicide is the second leading cause of death in youth aged 10 to 17 years.1 Suicide death rates for youth in the US increased from 6.8 per 100 000 in 2007 to 10.7 per 100 000 in 2018.2 The prevalence of suicidal thoughts or behaviors is higher than suicide death rates, with 18.8% of high school students nationwide reporting having seriously considered attempting suicide, 15.7% having made a plan on how to attempt suicide, and 8.9% having attempted suicide 1 or more times.3 These rates are slightly higher in female individuals than in male individuals3 and in White individuals compared with Black or Hispanic individuals,3 although overall trends in suicide are slightly declining in female youth and rising in Black youth.4 Risk factors for youth suicide include a history of psychiatric disorders or substance use; previous suicide attempts; a history of abuse or adverse childhood experiences; exposure to violence or victimization; bullying; family history of suicide; availability of means; exposure to suicide; social stress or isolation; and emotional and cognitive factors, including hopelessness or helplessness, despair or agitation, and impaired problem solving.5,6,7

Given the widespread psychosocial disruption associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, many experts have voiced concern regarding youth suicide rates.8,9,10,11 Survey-level data examining presentations to a pediatric emergency department (ED) in Texas for suicidal ideation or attempt in youth aged 10 to 17 years during the beginning of the pandemic revealed the odds of suicidal ideation or attempt were higher in some months between January and July 2020 compared with the same months in 2019.12 Similarly, a recent news article reported a 66% increase in the number of children with suicidal ideation in the ED of a pediatric hospital in California for an unknown time period.11 However, diagnosis-based, population-level evidence regarding the prevalence of suicide attempts among youth during the COVID-19 pandemic is lacking.

Using data from a large, integrated, community-based health system in Northern California, we compared 2020 incidence rates of ED encounters for suicidal thoughts or behaviors in youth aged 5 to 17 years to incidence rates in the same population in 2019. Further, we examined whether the relative risk of ED encounters for suicidal thoughts or behaviors changed during the pandemic in 2020 compared with 2019 using percent relative effects. To understand if an urgent health condition reflected similar ED presentation patterns as suicide-related visits in proportion to overall visits, we assessed youth ED encounters for appendicitis, which would be expected to remain stable from 2019 to 2020. Given the psychosocial disruptions associated with COVID-19, we hypothesized that a greater number and percent of all ED encounters would be for suicidal thoughts or behaviors among youth. As an exploratory analysis, patient clinical and demographic characteristics in 2019 and 2020 were examined before and after the onset of local shelter-in-place orders during the pandemic.

Methods

This retrospective, observational study took place at Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC), a large, integrated, health care delivery system in the US with more than 4 million patients (one-third of the regional population). KPNC patients are highly representative of the racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic diversity of the surrounding and statewide population.13 Electronic health record data for patients aged 5 to 17 years seeking emergency care for suicidal thoughts or behaviors from January 1, 2020, to December 15, 2020, and the corresponding dates in 2019 were included. The Research Determination Committee for the KPNC region determined that the project did not meet the regulatory definition of human subjects research. All data included were deidentified prior to analysis. The research was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cross-sectional studies.

Measures

Suicide-related encounters were defined by International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) diagnostic codes identified by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as representing suicidal thoughts or behaviors, including R45.85 (suicidal thoughts), T14.91, T36.xx3(4)-T50.xx2(4), T51.xx2 (4)-T65.xx2(4), T71.xx2 (4), and X71-X83 (suicide attempts) (eAppendix in the Supplement).14 Appendicitis at ED presentation was defined by ICD-10-CM codes K35.2x, K35.3x, K35.80x, K35.89x, K36, or K37. COVID-19 case and hospitalization data were from California Government Operations Agency sponsors, a statewide open data portal.15

Patient-level demographic, clinical, and health insurance enrollment characteristics were extracted for all encounters. Demographic characteristics included age, patient-reported race and ethnicity, and patient-reported sex. Patient race and ethnicity data were collected as a routine part of electronic health record meaningful use; categories follow the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention standards. Clinical characteristics included all encounter diagnoses paired with the suicide diagnosis and history of encounters in any outpatient (in-person or telehealth), emergency, or inpatient settings associated with a mental health or suicide diagnosis in the 1 to 2 years prior to index date. For outpatient encounters, we noted group therapy separately, as the COVID-19 pandemic may have had unique impacts on group therapy accessibility and dynamics. For patient-level analyses, we excluded 535 patients in 2019 and 600 patients in 2020 who had less than 1-year continuous health insurance enrollment prior to the index date of their first ED encounter. Variables examining 2 years’ prior health history excluded an additional 210 patients in 2019 and 186 in 2020. Diagnoses paired with the main suicide-related ED encounter included substance use (ICD-10-CM codes F10-19, excluding tobacco use); psychiatric (ICD-10-CM codes F20-29, F30-31, F32-39, F40-43.12, F43.2-43.9, and F70-98); and other non–mental health diagnoses (representing fewer than 1% of patient encounters).

Statistical Analysis

For incidence rate and youth demographic characteristics, data were examined and compared between 2019 and 2020 in 4 distinct time intervals corresponding to the pre–COVID-19 pandemic period (January 1 to March 9), the initial Bay Area and California shelter-in-place orders (March 10 to May 31), the summer (June 1 to August 31), and the fall (September 1 to December 15). To characterize the percent relative effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide-related ED encounters, the prepandemic period (January 1 to March 9) was compared with the period after the initial Bay Area and California shelter-in-place orders (March 10 to December 15). All statistical tests were 2-sided with a P value ≤.05 considered significant. Adjustments for multiple comparisons were made using the Bonferroni correction (Bonferroni-corrected P values were multiplied by 4). Incidence rates (IR) and IR ratios (IRR) for suicide-related encounters were calculated relative to the health system population for youth aged 5 to 17 years (per 100 000 persons). Given that ED use may have been disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic,16 we examined the relative risk of suicide-related ED encounters as a proportion of all youth ED visits for 2020 and 2019, then calculated the percent relative effect with 95% CIs. As a nonpsychiatric comparator, we examined the relative risk of encounters for appendicitis among the number of total ED encounters by youth aged 5 to 17 years. Patient-level data for 2019 and 2020 were examined using risk calculations then calculating the percent relative effect using each first presentation to the ED for suicidal thoughts or behaviors in the period. All analyses were conducted with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc).

Results

Suicide-Related ED Encounters Among Youth During the COVID-19 Pandemic

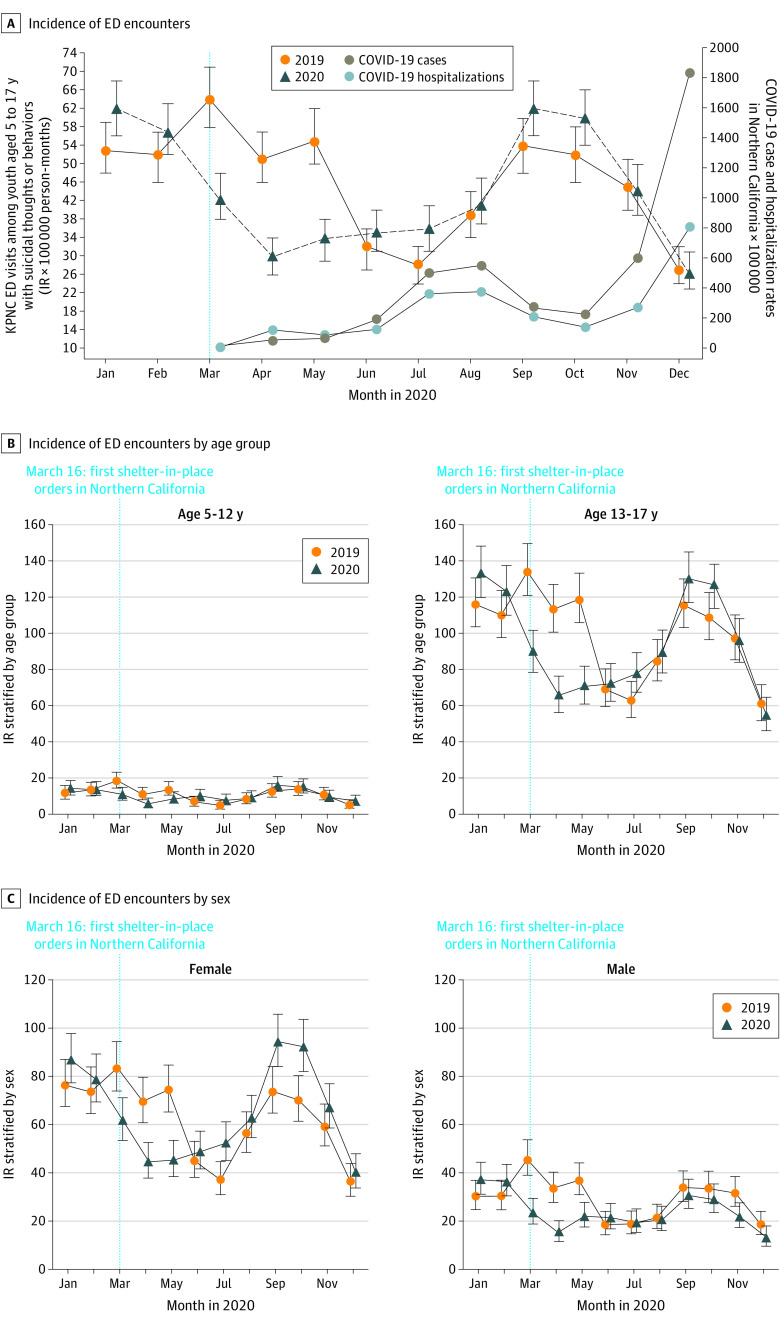

There were 2123 youth with suicide-related ED encounters in 2020 and 2339 in 2019 included in this study. Of these, 1483 (69.9%) in 2020 and 1542 (65.9%) in 2019 were female, and 1798 (84.7%) in 2020 and 1998 (85.4%) in 2019 were aged 13 to 17 years. Before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, ED encounters for suicidal thoughts or behaviors among youth aged 5 to 17 years resembled 2019 rates except for March through May 2020 (Figure 1). Suicide-related encounters during the initial shelter-in-place orders were significantly lower relative to the same time periods in 2019 (IRR, 0.57; 95%, CI 0.51-0.63; P < .001) (Table 1). Suicide-related encounters for youth aged 5 to 17 years were statistically equivalent during the remainder of the year after Bonferroni correction compared with 2019 periods.

Figure 1. Incidence of Monthly Emergency Department (ED) Encounters Among Youth With Suicidal Thoughts or Behaviors in 2019 and 2020.

A, Overall incidence of emergency department encounters among youth aged 5 to 17 years with suicidal thoughts or behaviors. B, Incidence of emergency department encounters among youth aged 5 to 17 years with suicidal thoughts or behaviors stratified by age. C, Incidence of emergency department encounters among youth aged 5 to 17 years with suicidal thoughts or behaviors stratified by sex. ED encounters among youth with suicidal thoughts or behaviors dipped after the initial shelter-in-place orders in California, as did overall ED volume during this time. However, ED encounters among youth with suicidal thoughts or behaviors returned to 2019 levels toward the end of May 2020 and exceeded 2019 levels in October 2020. KPNC indicates Kaiser Permanente Northern California; IR, incidence rates.

Table 1. Incidence Rates for Emergency Department Encounters Among Youth With Suicidal Thoughts or Behaviors in 2019 and 2020.

| Population | Incidence rate (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan 1-Mar 9 | Mar 10-May 31 | Jun 1-Aug 31 | Sep 1-Dec 15 | |

| Overall | ||||

| 2019 | 61.6 (57.4-66.1) | 50.8 (47.7-54.1) | 32.7 (30.2-35.3) | 44.5 (41.9-47.1) |

| 2020 | 68.8 (64.4-73.5) | 28.9 (26.6-31.4) | 37.3 (34.7-40.2) | 48.1 (45.5-50.9) |

| IRR (95% CI) | 1.12 (1.01-1.23) | 0.57 (0.51-0.63) | 1.14 (1.03-1.27) | 1.08 (1.00-1.17) |

| P valuea | .10 | <.001 | .06 | .22 |

| Individuals aged 5-12 y | ||||

| 2019 | 15.0 (12.5-18.0) | 13.0 (11.0-15.2) | 6.8 (5.4-8.5) | 10.8 (9.2-12.5) |

| 2020 | 16.8 (14.1-20) | 6.9 (5.5-8.6) | 9.2 (7.6-11.1) | 12.2 (10.5-14.1) |

| IRR (95% CI) | 1.12 (0.87-1.44) | 0.53 (0.40-0.70) | 1.35 (1.01-1.82) | 1.13 (0.92-1.40) |

| P valuea | 1.5 | <.001 | .17 | .99 |

| Individuals aged 13-17 y | ||||

| 2019 | 133.2 (123.4-143.8) | 108.9 (101.6-116.6) | 72.2 (66.4-78.6) | 95.8 (89.9-102.1) |

| 2020 | 147.9 (137.7-158.9) | 62.3 (56.9-68.1) | 79.8 (73.7-86.5) | 102 (96.0-108.4) |

| IRR (95% CI) | 1.11 (1.0-1.23) | 0.57 (0.51-0.64) | 1.11 (0.98-1.24) | 1.07 (0.98-1.16) |

| P valuea | .20 | <.001 | .36 | .64 |

| Female | ||||

| 2019 | 87.4 (80.3-95.2) | 67.9 (62.7-73.4) | 46.2 (42-50.8) | 60.1 (55.9-64.6) |

| 2020 | 96.4 (89-104.4) | 41.6 (37.7-46) | 54.8 (50.2-59.7) | 73.6 (69.0-78.5) |

| IRR (95% CI) | 1.10 (0.98-1.24) | 0.61 (0.54-0.7) | 1.19 (1.04-1.35) | 1.22 (1.11-1.35) |

| P valuea | .41 | <.001 | .04 | <.001 |

| Male | ||||

| 2019 | 36.9 (32.5-41.9) | 34.5 (31-38.4) | 19.7 (17.1-22.7) | 29.5 (26.7-32.6) |

| 2020 | 42.4 (37.7-47.8) | 16.7 (14.3-19.5) | 20.6 (18-23.7) | 23.8 (21.3-26.6) |

| IRR (95% CI) | 1.15 (0.97-1.37) | 0.49 (0.40-0.59) | 1.05 (0.86-1.28) | 0.81 (0.69-0.94) |

| P valuea | .45 | <.001 | 2.6 | .02 |

Abbreviation: IRR, incidence rate ratio.

P values are Bonferroni adjusted by a factor of 4.

When examining the data by age groups, suicide-related ED visits were significantly lower for children aged 5 to 12 years and adolescents aged 13 to 17 years during the initial shelter-in-place orders (IRR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.40-0.70; P < .001 vs IRR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.51-0.64; P < .001), but similar to 2019 for the remainder of 2020. When examining the data by sex, suicide-related ED visits for male and female individual were significantly lower during the initial shelter-in-place orders (IRR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.40-0.70; P < .001 vs IRR, 0.57; 95% CI 0.51-0.64; P < .001). However, suicide-related ED visits for female youth were significantly higher during the summer and fall (IRR, 1.19; 95% CI, 1.04-1.35; P = .04 and IRR, 1.22; 95% CI, 1.11-1.35; P < .001, respectively), while suicide-related ED visits for male individuals decreased in the fall (IRR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.69-0.94; P = .02).

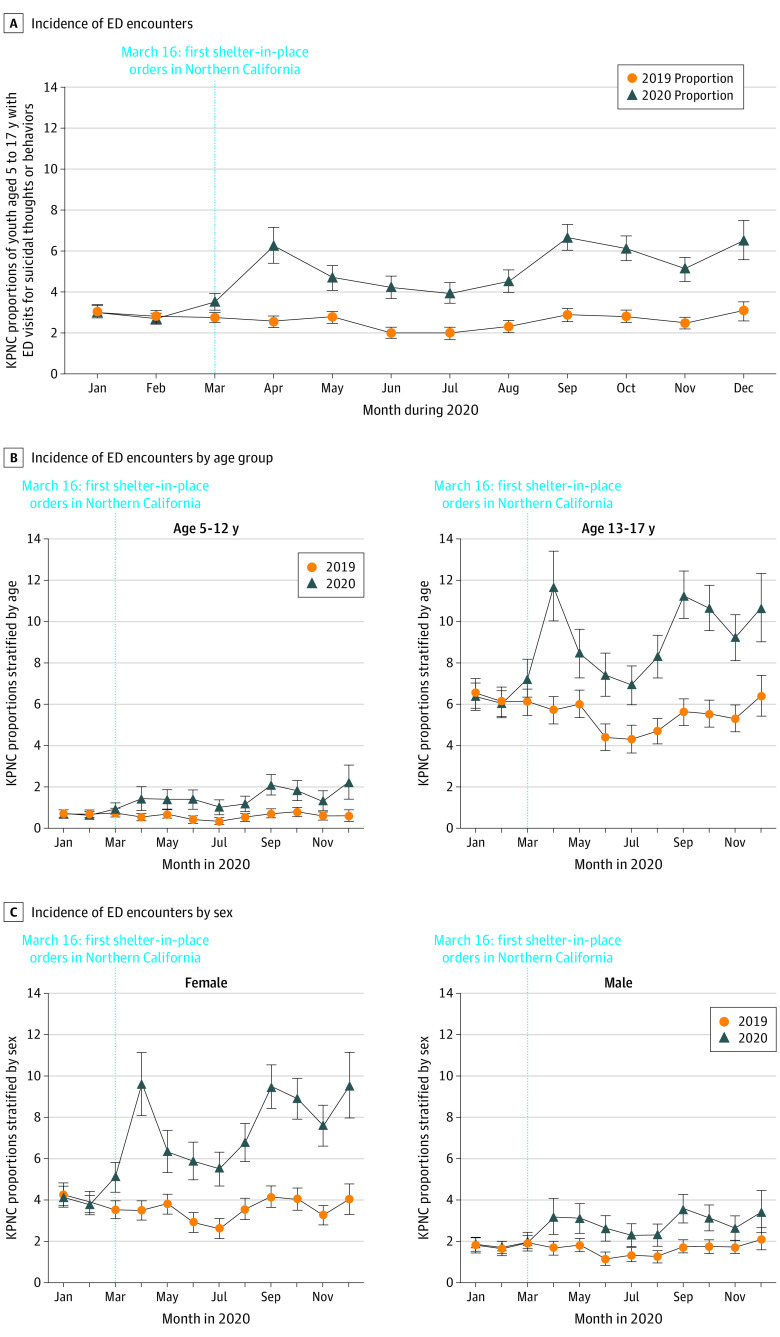

Percent Relative Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Youth ED Encounters Classified as Suicide-Related

ED encounters for any reason were lower at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic compared with the same period in 2019 (48 207 vs 104 293; 54% decrease). Given this denominator change, suicide-related encounters among youth accounted for a larger percent of overall youth ED encounters during the COVID-19 pandemic period compared with 2019 (Figure 2). Relative to overall ED encounters, the risk of presenting with suicidal thoughts or behaviors was 99.7% higher (95% CI, 91.2-108.2) (Table 2) after the initial shelter-in-place orders, like the relative risk of presenting with appendicitis. There was a 133.5% higher risk among youth aged 5 to 12 years (95% CI, 107.9-159.2) and a 69.4% higher risk among youth aged 13 to 17 years (95% CI, 61.4-77.3) of presenting with suicide-related concerns compared with 2019. Of these ED encounters, 35% were for suicidal behavior or attempts (as opposed to suicidal thoughts) in 2020, an increase from 26% in 2019 (95% CI, 6.8-11.1).

Figure 2. Relative Risk of Emergency Department (ED) Encounters Among Youth With Suicidal Thoughts or Behaviors in 2020 Compared with 2019.

A, Compared with 2019, individuals aged 5 to 17 years had higher risk of presenting to the emergency department with suicidal thoughts or behaviors each month in 2020. B, Individuals aged 13 to 17 years had higher risk compared with those aged 5 to 12 years. C, Female individuals had higher risk compared with male individuals. Denominator based on all ED encounters by individuals aged 5 to 17 years. KPNC indicates Kaiser Permanente Northern California.

Table 2. Emergency Department (ED) Encounters Among Youth With Suicidal Thoughts or Behaviors in 2019 and 2020.

| Variable | Year | Age, y | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan 1-Mar 9a | Mar 10-Dec 15b | ||||||

| 5-17 | 5-12 | 13-17 | 5-17 | 5-12 | 13-17 | ||

| Any ED encounter, No. | 2019 | 26 327 | 16 055 | 10 272 | 104 293 | 61 779 | 42 514 |

| 2020 | 29 692 | 17 932 | 11 760 | 48 207 | 25 159 | 23 048 | |

| ED high-acuity encounter, No. | 2019 | 14 349 | 8127 | 6222 | 55 024 | 29 959 | 25 065 |

| 2020 | 16 112 | 9114 | 6998 | 28 948 | 13 083 | 15 865 | |

| ED high-acuity encounter, % | 2019 | 55 | 51 | 61 | 53 | 48 | 59 |

| 2020 | 54 | 51 | 60 | 60 | 52 | 69 | |

| ED encounter for suicidal thoughts or behaviors, No. (% for suicide attempt)c | 2019 | 772 (26) | 114 (25) | 658 (26) | 2688 (26) | 388 (17) | 2300 (27) |

| 2020 | 875 (28) | 129 (22) | 746 (30) | 2481 (35) | 369 (27) | 2112 (36) | |

| Presentation with suicidal thoughts or behaviors as % of total ED encounters | 2019 | 2.9 | 0.7 | 6.4 | 2.6 | 0.6 | 5.4 |

| 2020 | 2.9 | 0.7 | 6.3 | 5.1 | 1.5 | 9.2 | |

| Percent relative effect (95% CI)d | NA | 0.5 (−9.1 to 10.1) | 1.3 (−23.9 to 26.6) | −1.0 (−11.1 to 9.1) | 99.7 (91.2 to 108.2) | 133.5 (107.9 to 159.2) | 69.4 (61.4 to 77.3) |

| ED encounter for appendicitis, No. | 2019 | 196 | 108 | 88 | 813 | 448 | 365 |

| 2020 | 216 | 127 | 89 | 737 | 354 | 383 | |

| Presentation with appendicitis as % of total ED encounters | 2019 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.9 |

| 2020 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.7 | |

| Percent relative effect (95% CI)d | NA | −2.3 (−21.3 to 16.8) | 5.3 (−20.9 to 31.5) | −11.7 (−39.4 to 16) | 96.1 (80.5 to 111.8) | 94.0 (71.9 to 116.1) | 93.6 (71.8 to 115.3) |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Jan 1-Mar 9 reflects the time prior to Bay Area shelter-in-place orders, which were followed by statewide shelter-in-place orders on Mar 16.

Mar 10-Dec 15 reflects the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic time period in 2020.

Percent suicide attempt was calculated as the number of ED encounters associated with suicide attempts in the numerator divided by the total number of ED encounters associated with suicidal thoughts and behaviors (including suicide attempts) in the denominator, as defined by the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes in the eAppendix in the Supplement.

Percent relative effect was calculated using risk ratio data as follows: [(Suicide-Related / Total ED Visits 2020 − Suicide-Related / Total ED Visits 2019) / Suicide-Related / Total ED Visits 2019] × 100. All encounters in the given time frame were included.

Characteristics of Youth With Suicidal Thoughts or Behaviors During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Table 3 shows the characteristics of youth presenting to the ED with suicidal thoughts or behaviors in 2020 compared with 2019 limited to patients with 1 year of health insurance enrollment prior to the ED encounter index date (absolute numbers in the eTable in the Supplement). Female youth had an 11.4% higher risk of presenting with suicidal thoughts or behaviors during the fall compared with the same period in 2019 (95% CI, 3.8-19.0), while male individuals had a 21.3% lower risk of presenting with suicidal thoughts or behaviors during this period (95% CI, −35.5 to −7.2). There was a 6.7% higher risk of having a comorbid psychiatric nonsubstance diagnosis at the time of the suicide-related ED encounter during the fall (95% CI, 1.0-12.3) compared with 2019 levels.

Table 3. Characteristics of Youth Presenting to the Emergency Department (ED) With Suicidal Thoughts or Behaviors in 2020 Compared With 2019.

| Patient characteristic | Percent relative effect (95% CI)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan 1-Mar 9 | Mar 10-May 31 | Jun 1-Aug 31 | Sep 1-Dec 15 | |

| Age, y | ||||

| 5-12 | 14.6 (−14.4 to 43.6) | −11.1 (−38.8 to 16.6) | 5.2 (−28.8 to 39.3) | 16 (−11.7 to 43.8) |

| 13-17 | −2.2 (−6.6 to 2.2) | 2.3 (−3.4 to 7.9) | −0.9 (−6.6 to 4.8) | −2.5 (−6.9 to 1.9) |

| Race and ethnicityb | ||||

| Asian | 5.4 (−27.8 to 38.6) | −22.9 (−59.0 to 13.1) | 19.7 (−35.3 to 74.8) | 19.6 (−15.2 to 54.5) |

| Black | −16.0 (−47.1 to 15.2) | −31.5 (−66.4 to 3.4) | 3.9 (−39.7 to 47.6) | −9.1 (−43.0 to 24.7) |

| Hispanic | −17.9 (−38.0 to 2.2) | −20.1 (−43.3 to 3.1) | −7.6 (−33.4 to 18.2) | −1.3 (−21.4 to 18.7) |

| Otherc | 25.3 (−9.8 to 60.4) | −18.0 (−52.0 to 15.9) | −12.4 (−48.7 to 23.9) | −1.2 (−29.5 to 27.0) |

| Unknownd | 3.1 (−52.9 to 59.1) | 45.7 (−35.8 to 127.2) | −13.7 (−85.6 to 58.3) | 32.2 (−29.6 to 94.1) |

| White | 5.6 (−6.8 to 18.0) | 23.6 (9.1 to 38.2) | 4.2 (−10.4 to 18.7) | −3.8 (−15.8 to 8.2) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 0.5 (−6.9 to 7.9) | 9.2 (−0.3 to 18.7) | 0.0 (−9.7 to 9.6) | 11.4 (3.8 to 19.0) |

| Male | −1.2 (−17.5 to 15.1) | −16.1 (−32.6 to 0.5) | 0.1 (−19.6 to 19.7) | −21.3 (−35.5 to −7.2) |

| Acuity | ||||

| Resuscitative/emergent | 1.5 (−0.7 to 3.7) | −1.2 (−3.9 to 1.6) | 0.1 (−3.1 to 3.3) | −0.1 (−2.4 to 2.2) |

| Urgent | −19.8 (−72.9 to 33.3) | 47.8 (−32.1 to 127.7) | −6.5 (−65.0 to 52.0) | 1.0 (−52.1 to 54.0) |

| Nonurgent | −100.0 (−197.7 to −2.3) | −100.0 (−212.9 to 12.9) | NAe | 4.9 (−158.7 to 168.5) |

| Diagnosis at ED encounterf | ||||

| Suicide only | −44.0 (−104.7 to 16.7) | −60.4 (−107.9 to −13.0) | 3.9 (−86.7 to 94.6) | −18.4 (−80.6 to 43.7) |

| Substance use | 24.0 (−35.8 to 83.9) | 20.8 (−35.2 to 76.7) | −9.4 (−54.6 to 35.8) | −20.8 (−59.1 to 17.6) |

| Psychiatric | 2.9 (−2.5 to 8.2) | 7.4 (−0.3 to 15.0) | 7.4 (−0.8 to 15.6) | 6.7 (1.0 to 12.3) |

| Non–mental health | −14.9 (−41.7 to 11.9) | −21.9 (−47.9 to 4.1) | −27.7 (−56.5 to 1.1) | −23 (−47.8 to 1.9) |

| Insurance type | ||||

| Kaiser Home Region | 0.6 (−4.0 to 5.1) | −4.4 (−9.7 to 0.9) | −0.9 (−6.4 to 4.6) | 2.4 (−1.9 to 6.6) |

| Other | −7.0 (−33.4 to 19.5) | 32.2 (−5.6 to 70.0) | 6.6 (−29.9 to 43.1) | −16.5 (−41.8 to 8.7) |

| No insurance listed | 152.1 (−91.8 to 396.0) | −4.4 (−168.7 to 159.9) | −6.5 (−160.8 to 147.9) | 214.6 (−191.0 to 620.2) |

| Disposition post-ED | ||||

| Home | −11.7 (−22.6 to −0.8) | −11.9 (−23.6 to −0.2) | −4.5 (−18.6 to 9.6) | −1 (−11.7 to 9.8) |

| Inpatient | 11.9 (0.9 to 23.0) | 14.5 (0.2 to 28.7) | 4.3 (−9.2 to 17.8) | 0.9 (−9.7 to 11.6) |

| Mental health diagnosis associated with an outpatient visit in previous 2 yg | ||||

| No | −12.2 (−66.3 to 41.9) | −30.5 (−93.4 to 32.4) | 54.1 (−18.0 to 126.2) | 129.4 (41.0 to 217.8) |

| Yes | 0.5 (−1.6 to 2.6) | 1.0 (−1.1 to 3.1) | −2.5 (−5.7 to 0.8) | −3.1 (−5.2 to −1.0) |

| Mental health diagnosis associated with an outpatient visit in previous yg | ||||

| No | −19.9 (−50.0 to 10.1) | −21 (−51.4 to 9.4) | 45.1 (5.6 to 84.5) | 87.5 (53.4 to 121.6) |

| Yes | 2.5 (−1.2 to 6.1) | 3.3 (−1.5 to 8.1) | −6.5 (−12.1 to −0.8) | −11.5 (−16.0 to −7.0) |

| ED visit for mental health or suicide in previous y | ||||

| No | −0.1 (−6.1 to 6.0) | −2.8 (−7.9 to 2.3) | 2.1 (−2.4 to 6.5) | 0.2 (−2.3 to 2.7) |

| Yes | 0.2 (−19.9 to 20.3) | 19.8 (−16.4 to 56) | −18.2 (−57.3 to 21.0) | −3.6 (−48.1 to 40.8) |

| Psychiatric inpatient in previous y | ||||

| No | −0.1 (−4.9 to 4.6) | −0.1 (−4.0 to 3.9) | 2.7 (−1.2 to 6.6) | 0.3 (−1.9 to 2.5) |

| Yes | 0.6 (−25.0 to 26.3) | 0.6 (−41.8 to 43.1) | −29.1 (−71.5 to 13.2) | −6.0 (−56.2 to 44.3) |

| Group therapy in previous y | ||||

| No | −4.7 (−11.5 to 2.2) | −1.8 (−9.2 to 5.6) | 7.0 (0.1 to 14.0) | 18.7 (13.3 to 24.0) |

| Yes | 12.4 (−5.8 to 30.6) | 5.5 (−17.4 to 28.4) | −24.9 (−49.7 to −0.2) | −56.1 (−72.2 to −40.0) |

| Group therapy in previous 2 y | ||||

| No | −2.5 (−10.6 to 5.6) | −7.4 (−16 to 1.2) | 8.1 (−0.9 to 17.1) | 13.6 (6.9 to 20.3) |

| Yes | 4.6 (−10.5 to 19.7) | 17.6 (−2.8 to 38) | −18.1 (−38.1 to 2.0) | −30.9 (−46.1 to −15.7) |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Percent relative effect was calculated for each row using risk ratio data as follows: [(Suicide-Related ED Visit for Characteristic / Suicide-Related ED Visits 2020 − Suicide-Related ED Visit for Characteristic / Suicide-Related ED Visits 2019) / Suicide-Related ED Visit for Characteristic / Suicide-Related ED Visits 2019] × 100. Sample sizes, percentages, and 95% CIs used to derive values can be found in the eTable in the Supplement.

Patient race and ethnicity were collected as a routine part of the electronic health record meaningful use. Race and ethnicity data were evaluated to as part of the analyses to determine if patient demographic characteristics for emergency department presentations with suicidal thoughts or behaviors differed in 2020 and 2019. Categories follow the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention standards. Data were collected by patient self-report.

Other included individuals identifying as Native American, Islander, and multiracial.

Unknown race indicates the variable was blank or coded as unknown.

Denominator was zero for this time period.

All patients had a suicide diagnosis. Substance use and psychiatric diagnoses in addition to the suicide code were pulled per patient encounter; if a patient had both a substance use and psychiatric diagnosis at the time of the encounter, they were grouped by the secondary diagnosis after suicide. Only first encounters in the given time frame were included for patients with 1-year continuous Kaiser Permanente Northern California insurance. Other insurance was defined as non–Kaiser Permanente Northern California insurance.

Mental health diagnoses included the psychiatric, substance use, and suicide-related codes found in the eAppendix in the Supplement.

Psychiatric History and Disposition of Youth With Suicidal Thoughts or Behaviors During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Relative to all youth ED encounters, youth with no history of outpatient encounters associated with a mental health or suicide diagnosis in the electronic health record during the 2 years prior had a 129.4% higher risk of a suicide-related ED encounter (95% CI, 41.0-217.8) during the fall of 2020 compared with fall of 2019. A similar pattern was seen for 1-year history, with a 45.1% higher risk (95% CI, 5.6-84.5) in the summer and an 87.5% higher risk (95% CI, 53.4-121.6) in the fall. This segment of youth accounted for a minority (less than 10%) of suicide-related ED visits in all time periods (eTable in the Supplement). The percentage of youth engaged in group therapy in the previous year was lower during the summer (24.9%; 95% CI, −49.7 to −0.2) and fall (56.1%; 95% CI −72.2 to −40.0) of 2020. Similarly, 2-year group therapy history was lower in the fall (30.9%; 95% CI, −46.1 to −15.7). There was no difference in youth history of psychiatric inpatient hospitalization or previous ED encounters for mental health or suicidal thoughts or behaviors between the years. The percentage of youth admitted to an inpatient medical or psychiatric facility from the ED was higher prior to local shelter-in-place orders (11.9%; 95% CI 0.9-23.0) and during the initial shelter-in-place orders (14.5%; 95% CI, 0.2-28.7), but similar between the 2 years otherwise.

Discussion

This retrospective cross-sectional study provided population and relative ED-encounter data for youth with suicidal thoughts or behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 compared with the previous year. Youth aged 5 to 17 years had a higher risk of presenting to the ED for suicidal thoughts and behaviors in 2020 after the initial shelter-in-place orders compared with 2019. This risk reflected the 54% decrease in overall youth ED encounters rather than a sustained increase in suicide-related encounters. Similar relative increases were observed for appendicitis, a life-threatening condition requiring ED services but not expected to increase with the COVID-19 pandemic. Compared with 2019, the IR of suicide-related ED encounters in 2020 was lower during the initial COVID-19 pandemic shelter-in-place orders, but remained similar for the rest of the year after adjusting for multiple comparisons. The proportion of suicide-related visits coded as suicide attempts or self-harm was significantly higher during the pandemic compared with 2019. Relative to the same period in 2019, suicide-related ED encounters for female individuals was higher in the summer and fall of 2020. Youth with comorbid psychiatric diagnoses in the ED or no history of outpatient encounters associated with a mental health or suicide diagnosis also had a higher risk of suicide-related ED encounters in 2020 compared with 2019. These data are consistent with previous reports that overall ED volume was lower16 and that higher percentages of ED visits among youth were suicide-related during the pandemic compared with the prior year.17

Other work has similarly found higher rates of suicide-related ED visits starting in late 2020 among girls aged 12 to 17 years.18 Although the COVID-19 pandemic has been associated with a wide range of social, economic, and health stressors in the lives of youth and their families, contributing to reported psychological distress,19 suicidal thoughts or behaviors may not have emerged until later in the pandemic and may not have emerged evenly among groups of youth. Mental health symptoms have worsened for girls according to reports from before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.20,21 There are sex differences in symptom manifestation, which may lead to differences in parental detection of mental health problems at different severity levels. Changes in parental monitoring and youth presence in the home or time spent together may have impacted the detection of subtler suicidal thoughts or behaviors in this population.

Among youth presenting to the ED for suicidal thoughts or behaviors, there was disproportionate growth among those with no history of outpatient encounters associated with a mental health or suicide-related diagnosis for the preceding 1 or 2 years. Most youth with suicidal thoughts or behaviors had a history of mental health outpatient encounters, and their numbers relative to all youth ED visits were lower or remained constant between 2019 and 2020. Therefore, we did not observe a pattern indicating that youth with recent mental health service use were diverted to the ED instead of accessing outpatient care. There was also an increase in risk among youth with comorbid psychiatric diagnoses at the ED encounter, a segment including youth without prior documented psychiatric history. Given the disproportionate growth in suicide-related encounters among youth without outpatient mental health service use in the preceding 1 to 2 years, further studies are needed to determine if these youth had no prior mental health disorder; had previously relied on supports in the community, such as school, religious organizations, or an outside physician or therapist, that were not accessible during the pandemic; or chose emergency rather than outpatient care for their mental health concerns during the pandemic.

During fall 2020, fewer youth with suicidal thoughts or behaviors had a history of group therapy in the preceding 1 or 2 years compared with 2019. Group therapy is an evidence-based intervention for youth with many psychiatric disorders22; further research should examine if past group therapy conferred protective effects for youth specific to the COVID-19 period. Together, these data are consistent with other reports from psychiatric outpatient services showing lower use among patients without psychiatric history during the initial COVID-19 pandemic shelter-in-place period compared with 2019.23 New patients may have been uniquely impacted perhaps owing to health care avoidance for less acute psychiatric symptoms that may precede suicidal thoughts or behaviors or unfamiliarity with navigating mental health care services.

Limitations

Limitations of this study include pulling data from our electronic health record only. The true incidence of suicidal thoughts or behaviors may be higher but not captured by KPNC patients presenting to non-KPNC facilities for these conditions or by patients experiencing these symptoms but not seeking care. Although representative of the sociodemographic diversity of Northern California and including patients with both private and public insurance types, the data set included a small portion of uninsured patients. We did not have access to reliable and recent suicide death data occurring outside of KPNC facilities, which would lead to underestimates in the incidence of suicidal thoughts or behaviors. The IRRs of 2019 and 2020 may reflect overall secular trends alone or reactions to the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly after the initial shelter-in-place orders. Further longitudinal research is needed to clarify this distinction.

Conclusions

In this cross-sectional study of youth with suicidal thoughts and behaviors, youth with no history of outpatient encounters associated with a mental health or suicide diagnosis, those with comorbid psychiatric disorders at ED presentation, and female populations had a higher risk of suicide-related ED encounters during the COVID-19 pandemic. These data are generalizable to other insured populations, given similarities between national and California sex distributions24 and use of ICD-10 codes to define the population. Further work is needed to understand if mental health care history findings are similar in nonintegrated health systems. These results suggest that, despite reduced health care use in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic,25,26,27 ED use among youth with suicidal thoughts or behaviors returned to typical levels by summer 2020. The disproportionate increase during the summer and fall of 2020 among youth without prior documented mental health use and with comorbid psychiatric disorders may reflect higher suicidality among youth without a previous mental health diagnosis, a shift in new mental health presentations from outpatient settings to the ED, or vulnerability among youth with undocumented prior mental health diagnoses who were not currently engaged with the health care system and may have lost contact with other resources during the pandemic. Sex differences in suicide-related ED encounters suggest further investigation regarding the mechanisms underlying this observation is warranted. Preventive efforts, including mental health screening, psychoeducation, and support in connecting to care, may be particularly valuable for these youth and their families. Innovative and immediately accessible tools for mental health care, such as technology-based care,28 may address the needs of this population as well. As suicide-related encounters have made up more ED volume during the pandemic, increasing ED-based interventions, staff trained in addressing emergency mental health needs, and aftercare resources may also be valuable in addressing the needs of this population.

eAppendix. Conditions and International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes defined as suicidal thoughts and behaviors

eTable. Sample size, percentages, and 95% CIs for Table 3

References

- 1.National Center for Injury Prevention and Control . 10 Leading causes of death by age group, United States—2017. Accessed February 17, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/pdf/leading_causes_of_death_by_age_group_2017-508.pdf

- 2.Curtin SC. State suicide rates among adolescents and young adults aged 10-24: United States, 2000-2018. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2020;69(11):1-10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ivey-Stephenson AZ, Demissie Z, Crosby AE, et al. Suicidal ideation and behaviors among high school students—youth risk behavior survey, 2019. MMWR Suppl. 2020;69(1)(suppl 1):47-55. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.su6901a6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindsey MA, Sheftall AH, Xiao Y, Joe S. Trends of suicidal behaviors among high school students in the United States: 1991-2017. Pediatrics. 2019;144(5):e20191187. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-1187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bilsen J. Suicide and youth: risk factors. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:540. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borowsky IW, Ireland M, Resnick MD. Adolescent suicide attempts: risks and protectors. Pediatrics. 2001;107(3):485-493. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.3.485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shain BN; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescence . Suicide and suicide attempts in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2007;120(3):669-676. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chatterjee R. Child psychiatrists warn that the pandemic may be driving up kids’ suicide risk. National Public Radio. February 2, 2021. Accessed February 5, 2021. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2021/02/02/962060105/child-psychiatrists-warn-that-the-pandemic-may-be-driving-up-kids-suicide-risk

- 9.Reardon S, News KH. Health officials fear COVID-19 pandemic-related suicide spike among indigenous youth. Time Magazine. December 21, 2020.Accessed February 5, 2021. https://time.com/5921715/indigenous-youth-suicide-covid-19/

- 10.Green EL. Surge of student suicides pushes Las Vegas schools to reopen. NY Times. January 24, 2021.Accessed February 5, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/24/us/politics/student-suicides-nevada-coronavirus.html

- 11.Gecker J. San Francisco sues its own school district to reopen classes. Associated Press News. February 3, 2021. Accessed February 5, 2021. https://apnews.com/article/san-francisco-sues-own-school-district-9fa9cf285326935ce79b86c3c4c56774

- 12.Hill RM, Rufino K, Kurian S, Saxena J, Saxena K, Williams L. Suicide ideation and attempts in a pediatric emergency department before and during COVID-19. Pediatrics. 2021;147(3):e2020029280. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-029280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gordon N, Lin T. The Kaiser Permanente Northern California adult member health survey. Perm J. 2016;20(4):15-225. doi: 10.7812/TPP/15-225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hedegaard H, Schoenbaum M, Claassen C, Crosby A, Holland K, Proescholdbell S. Issues in developing a surveillance case definition for nonfatal suicide attempt and intentional self-harm using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) coded data. Natl Health Stat Report. 2018;(108):1-19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.California Government Operations Agency . California open data portal. Accessed January 15, 2021. http://data.ca.gov

- 16.Hartnett KP, Kite-Powell A, DeVies J, et al. ; National Syndromic Surveillance Program Community of Practice . Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency department visits—United States, January 1, 2019-May 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(23):699-704. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6923e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leeb RT, Bitsko RH, Radhakrishnan L, Martinez P, Njai R, Holland KM. Mental health-related emergency department visits among children aged <18 years during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, January 1-October 17, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(45):1675-1680. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6945a3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yard E, Radhakrishnan L, Ballesteros MF, et al. Emergency department visits for suspected suicide attempts among persons aged 12-25 years before and during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, January 2019-May 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(24):888-894. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7024e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Racine N, Cooke JE, Eirich R, Korczak DJ, McArthur B, Madigan S. Child and adolescent mental illness during COVID-19: a rapid review. Psychiatry Res. 2020;292:113307. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou SJ, Zhang LG, Wang LL, et al. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of psychological health problems in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;29(6):749-758. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01541-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miranda-Mendizabal A, Castellví P, Parés-Badell O, et al. Gender differences in suicidal behavior in adolescents and young adults: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Int J Public Health. 2019;64(2):265-283. doi: 10.1007/s00038-018-1196-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCart MR, Sheidow AJ. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for adolescents with disruptive behavior. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2016;45(5):529-563. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2016.1146990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ridout KK, Alavi M, Ridout SJ, et al. Changes in diagnostic and demographic characteristics of patients seeking mental health care during the early COVID-19 pandemic in a large, community-based health care system. J Clin Psychiatry. 2021;82(2):20m13685. doi: 10.4088/JCP.20m13685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.United States Census Bureau . United States Quick Facts. 2019. Accessed July 6, 2021. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219

- 25.Suh-Burgmann EJ, Alavi M, Schmittdiel J. Endometrial cancer detection during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136(4):842-843. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000004087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solomon MD, McNulty EJ, Rana JS, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic and the incidence of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(7):691-693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2015630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corley DA, Sedki M, Ritzwoller DP, et al. ; National Cancer Institute’s PROSPR Consortium . Cancer screening during the Coronavirus Disease-2019 pandemic: a perspective from the National Cancer Institute’s PROSPR Consortium. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(4):999-1002. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.10.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mordecai D, Histon T, Neuwirth E, et al. How Kaiser Permanente created a mental health and wellness digital ecosystem. NEJM Catalyst. 2021;2(1). doi: 10.1056/CAT.20.0295 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Conditions and International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes defined as suicidal thoughts and behaviors

eTable. Sample size, percentages, and 95% CIs for Table 3