Key Points

Question

Are there patterns of atopic eczema activity that continue into adulthood?

Findings

Among 30 905 participants evaluated from birth into midlife, 4 patterns of activity for atopic eczema were identified across ages: high probability, decreasing, increasing, and low probability. Early life factors did not differentiate the high from the decreasing subtype, and the subtype with increasing probability of activity had the highest risk of poor self-reported health in midlife.

Meaning

The probability of atopic eczema remains high into adulthood for a subgroup of patients but decreases for others; a newly identified subgroup with increasing probability of activity in adulthood warrants additional research.

This cohort study follows members of 2 British population-based birth cohorts to examine whether early life risk factors and participant characteristics predict patterns of atopic eczema through midlife.

Abstract

Importance

Atopic eczema is characterized by a heterogenous waxing and waning course, with variable age of onset and persistence of symptoms. Distinct patterns of disease activity such as early-onset/resolving and persistent disease have been identified throughout childhood; little is known about patterns into adulthood.

Objective

This study aimed to identify subtypes of atopic eczema based on patterns of disease activity through mid-adulthood, to examine whether early life risk factors and participant characteristics are associated with these subtypes, and to determine whether subtypes are associated with other atopic diseases and general health in mid-adulthood.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This study evaluated members of 2 population-based birth cohorts, the 1958 National Childhood Development Study (NCDS) and the 1970 British Cohort Study (BCS70). Participant data were collected over the period between 1958 and 2016. Data were analyzed over the period between 2018 and 2020.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Subtypes of atopic eczema were identified based on self-reported atopic eczema period prevalence at multiple occasions. These subtypes were the outcome in models of early life characteristics and an exposure variable in models of midlife health.

Results

Latent class analysis identified 4 subtypes of atopic eczema with distinct patterns of disease activity among 15 939 individuals from the NCDS (51.4% male, 75.4% White) and 14 966 individuals from the BCS70 (51.6% male, 78.8% White): rare/no (88% to 91%), decreasing (4%), increasing (2% to 6%), and persistently high (2% to 3%) probability of reporting prevalent atopic eczema with age. Sex at birth and early life factors, including social class, region of residence, tobacco smoke exposure, and breastfeeding, predicted differences between the 3 atopic eczema subtypes and the infrequent/no atopic eczema group, but only female sex differentiated the high and decreasing probability subtypes (odds ratio [OR], 1.99; 95% CI, 1.66-2.38). Individuals in the high subtype were most likely to experience asthma and rhinitis, and those in the increasing subtype were at higher risk of poor self-reported general (OR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.09-1.53) and mental (OR 1.45; 95% CI, 1.23-1.72) health in midlife.

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings of this cohort study suggest that extending the window of observation beyond childhood may reveal clear subtypes of atopic eczema based on patterns of disease activity. A newly identified subtype with increasing probability of activity in adulthood warrants additional attention given observed associations with poor self-reported health in midlife.

Introduction

Atopic eczema (also known as atopic dermatitis or eczema)1 affects up to 20% of children in industrialized settings,2,3 and is characterized by a heterogenous waxing and waning course, with variable age of onset and persistence of symptoms. Prior studies4,5,6,7,8 have identified differences in patterns of disease activity throughout childhood. In particular, subtypes with resolving disease in childhood have been identified, and early onset during the first 2 years of life has been associated with genetic variants and development of asthma and allergies.

Newer research has shown that atopic eczema is also common among adults, affecting 7% through 10% of the UK and US populations.9,10,11 There is a lack of studies that prospectively examine the course of atopic eczema beyond adolescence/early adulthood, and a more comprehensive understanding of disease activity across the life span is needed.12,13 Data on long-term disease course may offer insight into mechanisms for disease onset and persistence, are important when counseling patients, and would establish baseline trajectories for future studies of whether new treatments can modify disease course and development of comorbidities.

Using 2 British population-based longitudinal birth cohorts with more than 40 years of follow-up, we previously found that the majority of adults with atopic eczema had symptom onset after childhood, and that there were important differences in risk factor profiles between those with childhood-onset and adult-onset disease.14 However, this study may not fully represent the real-world heterogeneity in disease course.

Herein our objectives were to identify subtypes of atopic eczema based on patterns of disease activity from birth through mid-adulthood, to examine whether early life risk factors and participant characteristics were associated with these subtypes, and to determine whether the subtypes are associated with other atopic diseases and general health in midlife.

Methods

Study Population

We used data from the 1958 National Child Development Study (NCDS) and 1970 British Cohort Study (BCS70), which are ongoing, multidisciplinary studies that include 17 415 and 17 196 individuals born in Great Britain during 1 week in March 1958 and March 1970, respectively.15,16 There have been 9 subsequent waves of follow-up in each cohort at approximately 5-year to 10-year intervals. In the NCDS, we excluded the waves at ages 33, 46, and 55 years because atopic eczema data were not collected, and we excluded individuals from both cohorts without any data on the presence/absence of symptoms of atopic eczema (n = 1476 for NCDS; n = 2230 for BCS70). Additional information on response patterns in both cohorts has been reported elsewhere.17,18

Identification of Atopic Eczema Subtypes Based on Disease Activity Over Time

We used latent class analysis (LCA) to identify subtypes of atopic eczema activity patterns based on parent-reported or self-reported atopic eczema period prevalence from standardized questions at 6 (NCDS) to 9 (BCS70) waves of follow-up (eTable 1 in the Supplement). This measure was previously shown to coincide with standardized clinical examinations among children in the NCDS,19,20 and a similar question demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity for physician-diagnosed atopic eczema in US populations.21

We ran generalized linear latent and mixed models with increasing numbers of latent classes. To select the number of classes, we examined model fit statistics, the estimated class sizes, and clinical interpretation.22 Models with lower adjusted Bayesian information criteria (BIC) values and higher entropy values that produced subtypes including 2% or more of the population were preferred.

We estimated the posterior latent class (subtype) probabilities and examined their distributions. Probabilities close to 1 suggest a trajectory is well classified and distinct from the other subtype trajectories. Individuals were assigned to the class for which they had the highest posterior probability. We visually evaluated the consistency of individual patterns of disease activity within each class using heat maps with a dendrogram.

Identification of Early-Life and Midlife Factors Associated With Atopic Eczema Subtypes

We examined associations between early life factors and the newly identified atopic eczema subtypes, which were considered categorical outcomes in multinomial logistic regression models. Early-life factors were selected a priori based on literature showing associations with childhood atopic eczema and adult-onset eczema in the British birth cohorts.14,19,23,24 Adjusted models included sex, ethnic group, history of any breastfeeding, region of residence in childhood, childhood smoke exposure (either parent reporting current smoking at age 5 years in the BCS70, and age 16 years in the NCDS), household size (≤3 persons vs >3 persons), maternal in utero smoke exposure, birth weight, and the Registrar General’s designation of social class in childhood (a standard measure based on the father’s highest occupational status reported on any survey at ages 0 through 10/11 years). Data on parental history of asthma and hay fever were only available in the BCS70 at age 5 years.

Next, we examined whether atopic eczema subtype (now as a predictor variable) was associated with binary outcomes of self-reported asthma, hay fever, general health, and mental health in separate multivariable logistic regression models adjusted for sex, ethnicity, social class, and cohort. Asthma and rhinitis were based on self-report of the condition at age 46 years (BCS70) or age 50 years (NCDS, eTable 1 in the Supplement). General health was assessed using the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) at age 50 years (NCDS) and age 46 years (BCS70).25 We used a derived score based on 5 questions in the general health domain that ranged from 1 to 100, with higher scores indicating a more positive self-assessment of health, as the outcome in a linear regression model.26 To compare with other analyses, we also dichotomized responses from a single question from the SF-36 about general health (“excellent/very good/good” vs “fair/poor”). Mental health was assessed using the Malaise Inventory scale at age 42 years. Based on previous literature, a cut-off of 7 or higher (of 24 items) and 4 or higher (of 9 items) was used to define high risk of psychiatric morbidity for NCDS and BCS70, respectively.27

We performed all regressions separately in each cohort, and after evaluating for consistency, we conducted a meta-analysis of individual participant data, assuming fixed effects across studies and accounting for the clustering of participants within cohorts.

Sensitivity Analyses

Because the timing of questions about atopic eczema period prevalence varied slightly across cohorts (eTable 1 in the Supplement), we performed a sensitivity analysis repeating the cohort-specific LCAs using only 5 time points that were most consistent across both cohorts.

Missing Data

The LCA method accommodates missing outcome (atopic eczema) data with full information maximum likelihood estimation; therefore, we used all available atopic eczema data in both cohorts and assessed individual patterns of missingness using heat maps. We performed multiple imputation in each cohort separately with iterative chained equations to impute missing early-life data (see eMethods in the Supplement for details). The imputed results were compared with the complete case analysis. We did not impute data on atopic comorbidities or general/mental health in midlife because most of the missing data were due to attrition.

This study was deemed as exempt from approval by the institutional review board of the University of California San Francisco because no identifiable information was accessed by the study team. Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata, version 16 (StataCorp).

Results

The study sample included 15 939 individuals from the NCDS and 14 966 from the BCS70. Atopic eczema was reported at 1 or more time point(s) by 16.7% and 24.4% of participants in the NCDS and BCS70, respectively. Demographic and early-life characteristics for both cohorts are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Patient Characteristics by Cohort.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCDS | BCS70 | |||||

| Total (n = 15 939)a | No atopic eczema (n = 13 278 [83.3%]) | Atopic eczema (n = 2661 [16.7%]) | Total (n = 14 966)a | No atopic eczema (n = 11 310 [75.6%]) | Atopic eczema (n = 3656 [24.4%]) | |

| Asthma | ||||||

| No | 12 633 (79.3) | 10 809 (81.4) | 1824 (68.5) | 11 996 (80.2) | 9359 (82.7) | 2637 (72.1) |

| Any | 3238 (20.3) | 2402 (18.1) | 836 (31.4) | 2300 (15.4) | 1355 (12.0) | 945 (25.8) |

| Missing | 68 (0.4) | 67 (0.5) | 1 (0) | 670 (4.5) | 596 (5.3) | 74 (2.0) |

| Rhinitis | ||||||

| No | 11 718 (73.5) | 10 140 (76.4) | 1578 (59.3) | 9624 (64.3) | 7836 (69.3) | 1788 (48.9) |

| Any | 4149 (26.0) | 3066 (23.1) | 1083 (40.7) | 5329 (35.6) | 3467 (30.7) | 1862 (50.9) |

| Missing | 72 (0.5) | 72 (0.5) | 0 (0) | 13 (0.1) | 7 (0.1) | 6 (0.2) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 8200 (51.4) | 6996 (52.7) | 1204 (45.2) | 7716 (51.6) | 6110 (54.0) | 1606 (43.9) |

| Female | 7739 (48.6) | 6282 (47.3) | 1457 (54.8) | 7250 (48.4) | 5200 (46.0) | 2050 (56.1) |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 12 018 (75.4) | 9843 (74.1) | 2175 (81.7) | 11 790 (78.8) | 8758 (77.4) | 3032 (82.9) |

| Other | 160 (1.0) | 132 (1.0) | 28 (1.1) | 510 (3.4) | 389 (3.4) | 121 (3.3) |

| Missing | 3761 (23.6) | 3303 (24.9) | 458 (17.2) | 2666 (17.8) | 2163 (19.1) | 503 (13.8) |

| Region of residence in childhood | ||||||

| Southern England | 4871 (30.6) | 4014 (30.2) | 857 (32.2) | 4427 (29.6) | 3177 (28.1) | 1250 (34.2) |

| Central England | 4689 (29.4) | 3866 (29.1) | 823 (30.9) | 3454 (23.1) | 2555 (22.6) | 899 (24.6) |

| Northern England | 6379 (40.0) | 5398 (40.7) | 981 (36.9) | 4804 (32.1) | 3718 (32.9) | 1086 (29.7) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2281 (15.3) | 1860 (16.4) | 421 (11.5) |

| Social class in childhoodb | ||||||

| I/II | 4489 (28.2) | 3632 (27.4) | 857 (32.2) | 5281 (35.3) | 3780 (33.4) | 1501 (41.1) |

| IIIa/b | 9626 (60.4) | 8069 (60.8) | 1557 (58.5) | 8410 (56.2) | 6504 (57.5) | 1906 (52.1) |

| IV/V | 1718 (10.8) | 1479 (11.1) | 239 (9.0) | 1238 (8.3) | 995 (8.8) | 243 (6.6) |

| Missing | 106 (0.7) | 98 (0.7) | 8 (0.3) | 37 (0.2) | 31 (0.3) | 6 (0.2) |

| Household size | ||||||

| ≤3 Persons | 1211 (7.6) | 996 (7.5) | 215 (8.1) | 1339 (8.9) | 999 (8.8) | 340 (9.3) |

| >3 Persons | 12 357 (77.5) | 10 186 (76.7) | 2171 (81.6) | 11 374 (76.0) | 8471 (74.9) | 2903 (79.4) |

| Missing | 2371 (14.9) | 2096 (15.8) | 275 (10.3) | 2253 (15.1) | 1840 (16.3) | 413 (11.3) |

| Smoking during pregnancy | ||||||

| No | 10 482 (65.8) | 8690 (65.4) | 1792 (67.3) | 8050 (53.8) | 5963 (52.7) | 2087 (57.1) |

| Any | 5257 (33.0) | 4427 (33.3) | 830 (31.2) | 6847 (45.8) | 5293 (46.8) | 1554 (42.5) |

| Missing | 200 (1.3) | 161 (1.2) | 39 (1.5) | 69 (0.5) | 54 (0.5) | 15 (0.4) |

| Childhood smoke exposure | ||||||

| No | 2993 (18.8) | 2424 (18.3) | 569 (21.4) | 4340 (29.0) | 3165 (28.0) | 1175 (32.1) |

| Any | 7953 (49.9) | 6564 (49.4) | 1389 (52.2) | 8337 (55.7) | 6272 (55.5) | 2065 (56.5) |

| Missing | 4993 (31.3) | 4290 (32.3) | 703 (26.4) | 2289 (15.3) | 1873 (16.6) | 416 (11.4) |

| Parental history of atopy | ||||||

| No | NA | NA | NA | 8638 (57.7) | 6687 (59.1) | 1951 (53.4) |

| Any | NA | NA | NA | 2958 (19.8) | 1918 (17.0) | 1040 (28.4) |

| Missing | NA | NA | NA | 3370 (22.5) | 2705 (23.9) | 665 (18.2) |

| Birth weight, mean (SD), kg | 3.3 (0.5) | 3.3 (0.5) | 3.3 (0.5) | 3.3 (0.5) | 3.3 (0.5) | 3.3 (0.5) |

| Missing | 529 (3.3) | 445 (3.4) | 84 (3.2) | 14 (0.1) | 13 (0.1) | 1 (0.03) |

| Breastfeeding | ||||||

| No | 4435 (27.8) | 3742 (28.2) | 693 (26.0) | 7957 (53.2) | 6075 (53.7) | 1882 (51.5) |

| Any | 9583 (60.1) | 7832 (59.0) | 1751 (65.8) | 4659 (31.1) | 3323 (29.4) | 1336 (36.5) |

| Missing | 1921 (12.1) | 1704 (12.8) | 217 (8.2) | 2350 (15.7) | 1912 (16.9) | 438 (12.0) |

Abbreviations: BCS70, 1970 British Cohort Study; NA, not applicable; NCDS, National Childhood Development Study.

Number is based on patients with at least 1 response to an eczema question; missing refers to number of individuals without data on each covariate.

Registrar General’s social class: I, professional; II, managerial and technical; III, skilled; IV, partly skilled; V, unskilled.

Atopic Eczema Subtypes Based on Disease Activity Over Time

Model fit statistics demonstrated that 5-class models performed slightly better than 4-class models; however, the additional class included only 1% of the sample in each cohort, resulted in lower entropy scores, and did not improve the clinical interpretation (eFigure 1 and eTable 2 in the Supplement). Therefore, we present results for the 4-class model. In this model, participants had a high probability of being assigned to their most likely subtype and a low probability of being assigned to one of the other subtypes (eTable 3 in the Supplement), and individual disease trajectories followed a similar overall pattern despite individual heterogeneity (eFigure 2 in the Supplement).

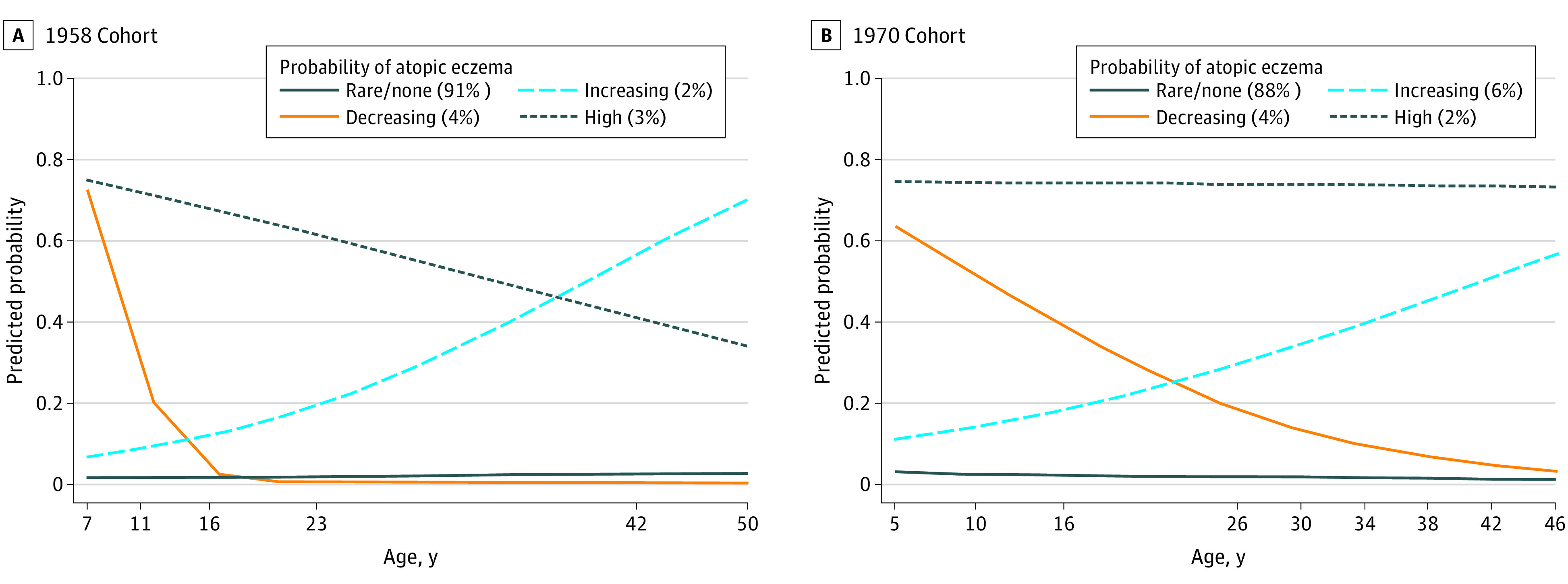

We labeled the subtypes in each cohort by the probability of atopic eczema with age: rare/none, decreasing, high, and increasing (Figure). The decreasing and high subtypes were similar in size in both cohorts, but the increasing subtype was larger in the BCS70 as compared with the NCDS (6% vs 2%). A sensitivity analysis using only atopic eczema data from the 5 time points most similar between cohorts did not achieve as good of a model fit or separation between the classes in mid-adulthood as analyses using all available data (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Figure. Estimated Probabilities of Atopic Eczema Symptoms at Each Age for Each Subtype in 4 Class Models From 2 British Birth Cohorts.

Predicted probabilities at each age generated from generalized linear and latent mixed models.

Early Life Factors Associated With Atopic Eczema Subtypes

We examined associations between atopic eczema subtypes and early life factors using rare/no atopic eczema as a reference group. We found that sex, region of residence, social class, in utero smoke exposure, and breastfeeding were associated with differences in disease trajectory subtype (Table 2). Female sex was associated with higher odds of the high and increasing subtypes and lower odds of the decreasing subtype as compared with the rare/no atopic eczema group. Those who resided in Northern England or Scotland during childhood experienced lower odds of all subtypes of atopic eczema than those who resided in Southern England. Those from higher childhood social class and who were breastfed were more likely to be in the high and decreasing subtypes. Parental history of atopic disease in the BCS70 was a significant predictor of all atopic eczema subtypes as compared with the rare/no atopic eczema group (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

Table 2. Association Between Early Life Factors and Atopic Eczema (AE) as Compared With Rare/No AE Subtype .

| Demographic/early life factors | AE, OR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| High vs rare/no | Decreasing vs rare/no | Increasing vs rare/no | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Female | 1.76 (1.53-2.04) | 0.89 (0.79-0.99) | 1.77 (1.56-2.01) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| European, White | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Other | 0.89 (0.53-1.48) | 1.03 (0.72-1.46) | 0.86 (0.59-1.25) |

| Region of early childhood residencea | |||

| Southern England | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Central England/Wales | 1.06 (0.89-1.27) | 0.85 (0.74-0.97) | 0.93 (0.80-1.09) |

| Northern England/Scotland | 0.82 (0.69-0.98) | 0.69 (0.60-0.79) | 0.82 (0.70-0.96) |

| Highest social class in childhoodb,c | |||

| I/II | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| III | 0.69 (0.59-0.80) | 0.80 (0.71-0.91) | 0.92 (0.80-1.05) |

| IV/V | 0.50 (0.37-0.68) | 0.56 (0.44-0.71) | 0.88 (0.69-1.12) |

| Household size in early childhood | |||

| ≤3 Persons | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| >3 Persons | 1.02 (0.79-1.32) | 0.95 (0.79-1.15) | 0.93 (0.75-1.16) |

| In utero smoke exposure | |||

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Any | 0.83 (0.70-0.98) | 1.00 (0.87-1.13) | 0.91 (0.79-1.05) |

| Childhood smoke exposure | |||

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Any | 0.94 (0.78-1.12) | 0.95 (0.82-1.10) | 0.91 (0.79-1.06) |

| Birth weight, per kg increase | 1.09 (0.95-1.25) | 1.01 (0.91-1.13) | 0.93 (0.83-1.05) |

| Breastfeeding | |||

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Any | 1.39 (1.18-1.63) | 1.20 (1.06-1.36) | 1.18 (1.03-1.35) |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio.

Region of early childhood residence: overall P values are .01 for high vs rare/no AE, <.001 for decreasing vs rare/no AE, and .04 for increasing vs rare/no AE.

Registrar General’s social class: I, professional; II, managerial and technical; III, skilled; IV, partly skilled; V, unskilled.

Highest social class in childhood: overall P values are <.001 for high vs rare/no AE, <.001 for decreasing vs rare/no AE, and .36 for increasing vs rare/no AE.

Using the same regression models but changing the comparison group to examine differences between atopic eczema subgroups, we found that only female sex was associated with an increased risk of the high subtype as compared with the decreasing subtype (Table 3). Residence in Central England as compared with Southern England was also associated with an increased risk of the high subtype, but the full geography variable did not meet statistical significance as an independent predictor. Female sex and lower childhood social class were associated with increasing as compared with decreasing subtypes.

Table 3. Association Between Early Life Factors and Atopic Eczema Activity Subtypes as Compared With the Early Onset/Decreasing Subtype for the 1958 and 1970 Cohorts Meta-analysis (N = 30 905 across all classes).

| Characteristic | Atopic eczema, OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| High vs decreasing | Increasing vs decreasing | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Female | 1.99 (1.66-2.38) | 1.99 (1.69-2.35) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| European, White | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Other | 0.86 (0.47-1.58) | 0.84 (0.51-1.38) |

| Region of early childhood residencea | ||

| Southern England | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Central England/Wales | 1.26 (1.01-1.56) | 1.10 (0.90-1.36) |

| Northern England/Scotland | 1.18 (0.95-1.47) | 1.19 (0.97-1.45) |

| Highest social class in childhoodb,c | ||

| I/II | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| III | 0.86 (0.71-1.03) | 1.14 (0.95-1.36) |

| IV/V | 0.90 (0.61-1.32) | 1.58 (1.13-2.21) |

| Household size in early childhood | ||

| ≤3 Persons | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| >3 Persons | 1.08 (0.79-1.47) | 0.98 (0.75-1.30) |

| In utero smoke exposure | ||

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Any | 0.83 (0.68-1.03) | 0.91 (0.76-1.10) |

| Childhood smoke exposure | ||

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Any | 0.99 (0.79-1.23) | 0.96 (0.79-1.18) |

| Birth weight, per kg increase | 1.08 (0.90-1.28) | 0.92 (0.79-1.08) |

| Breastfeeding | ||

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Any | 1.16 (0.95-1.41) | 0.98 (0.82-1.17) |

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio.

Region of early childhood residence: overall P values are .10 for high vs decreasing atopic eczema and .24 for increasing vs decreasing atopic eczema.

Registrar General’s social class: I, professional; II, managerial and technical; III, skilled; IV, partly skilled; V, unskilled.

Highest social class in childhood: overall P values are .27 for high vs decreasing atopic eczema and .02 for increasing vs decreasing atopic eczema.

Associations Between Disease Trajectory Subtypes With Other Atopic Disease, General Health, and Mental Health in Midlife

Those classified into the highly probable atopic eczema subtype consistently had the highest prevalence of asthma/wheeze and rhinitis, and those classified into the no/rare atopic eczema subtype had the lowest rates (eTable 5 in the Supplement). Compared with the no/rare atopic eczema subtype, all other subtypes had an increased odds of asthma and rhinitis in midlife (Table 4). The increasing and high subtypes were both associated with worse self-reported general health, and only the increasing subtype was associated with poor mental health (Table 4).

Table 4. Associations Between Atopic Eczema Subtypes and Other Atopic Disease, General Health, and Mental Health in Midlife for the 1958 and 1970 Meta-analyses.

| Characteristic | OR (95% CI)a | SF-36 general health at age 46/50 y [n = 15 810], mean difference (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma (n = 17 200) | Rhinitis (n = 17 200) | Poor mental health at age 42 y (n = 17 978) | Poor general health at age 46/50 y (n = 18 733) | ||

| Atopic eczema | |||||

| Rare/no | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| High | 3.45 (2.82 to 4.21) | 2.70 (2.24 to 3.26) | 1.06 (0.85 to 1.32) | 1.26 (1.03 to 1.55) | −1.24 (−3.21 to 0.73) |

| Decreasing | 1.70 (1.38 to 2.10) | 1.42 (1.18 to 1.70) | 0.89 (0.73 to 1.08) | 0.88 (0.72 to 1.07) | 0.03 (−1.67 to 1.73) |

| Increasing | 2.11 (1.75 to 2.53) | 1.92 (1.64 to 2.25) | 1.45 (1.23 to 1.72) | 1.29 (1.09 to 1.53) | −4.52 (−6.12 to −2.92) |

| Atopic eczema | |||||

| Decreasing | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| High | 2.02 (1.53 to 2.68) | 1.91 (1.48 to 2.46) | 1.20 (0.90 to 1.61) | 1.44 (1.09 to 1.90) | −1.27 (−3.82 to 1.28) |

| Increasing | 1.24 (0.95 to 1.62) | 1.36 (1.07 to 1.72) | 1.64 (1.27 to 2.11) | 1.47 (1.15 to 1.89) | −4.55 (−6.83 to −2.27) |

| Atopic eczema | |||||

| Increasing | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Decreasing | 0.81 (0.62 to 1.06) | 0.74 (0.58 to 0.93) | 0.61 (0.47 to 0.79) | 0.68 (0.53 to 0.87) | 4.55 (2.27 to 6.83) |

| High | 1.63 (1.26 to 2.12) | 1.41 (1.11 to 1.79) | 0.73 (0.56 to 0.96) | 0.98 (0.75 to 1.27) | 3.28 (0.79 to 5.77) |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; SF-36, 36-Item Short Form Health Survey.

Each column represents a separate logistic or linear regression model predicting the odds of each health outcome. The rows show different reference groups for the same regression model.

Sensitivity and Missing Data Analyses

Primary results described above use the combined and imputed cohort. Additional analyses conducted separately in each cohort (eTable 4 in the Supplement) and a complete case analysis (eTable 6 in the Supplement) yielded similar results.

Discussion

Leveraging 2 large population-based birth cohorts with repeated assessments of individual atopic eczema disease activity, we identified 4 distinct disease trajectories based on probability of reporting atopic eczema with age: a majority of people who report no atopic eczema or who report it rarely, decreasing probability, high probability, and increasing probability of reporting atopic eczema with age. Previously identified early life risk factors, including sex, region of residence, parental social class, in utero smoke exposure, and breastfeeding, were associated with the atopic eczema subtypes as compared with those with rare or no atopic eczema, but only female sex helped to differentiate the high from decreasing subtype. A newly identified subtype with increasing probability of atopic eczema with age was most likely to have poor self-reported general and mental health in midlife.

Comparison to Existing Literature

There is a lack of clarity regarding the terminology around atopic eczema/atopic dermatitis/eczema. We chose to use the term atopic eczema because atopic dermatitis is less commonly used in the UK, and using the term eczema alone is not recommended.28 The term atopic does not necessarily indicate the presence of atopy; in many population-based cohorts, most patients do not demonstrate immunoglobulin E–specific antibodies to common environmental allergens.29

We previously found differences between cohort participants who reported childhood-onset vs adulthood-onset atopic eczema.14 Our current analysis represents a substantial additional contribution because we used a hypothesis-free approach to identify distinct subtypes based on data from all ages and were able to compare associations and outcomes between those subtypes. These subtypes describe age-associated probabilities, not individual disease trajectories. Thus, we chose probabilistic labels such as increasing rather than late-onset, since an individual in the increasing probability subtype may not necessarily have late-onset disease: 21% of individuals in NCDS and 27% in BCS70 classified into this subtype experienced atopic eczema symptoms at some point in childhood (prevalence of atopic eczema by subtype and age summarized in eTable 5 in the Supplement).

While other studies have examined atopic eczema subtypes based on disease activity across childhood,4,5,6,7,8 the present study is unique in its duration of follow-up into midlife, which allowed for identification of a new subtype with an increasing probability of atopic eczema over time. This subtype was associated with poor general and mental health in midlife. An Australian study30 that examined asthma trajectories over many decades similarly found that late-onset asthma was most strongly associated with general health. Other studies show that the immune profile of atopic eczema varies by age, but have not yet examined disease course.31,32 These results indicate that disease duration and activity may be important in predicting outcomes and should be included in studies of atopic eczema comorbidities.

Geographic and temporal differences suggest that environmental factors may influence disease course. Geographic location was associated with all the atopic eczema subtypes in our study. A prior study using NCDS data33 found that regional differences in both examined and reported eczema were maintained when data were analyzed at the county level. There were also temporal differences: atopic eczema was more common in the BCS70, which is consistent with secular trends documented in other data sources,34,35 and the increasing subtype was larger in the BCS70 (6% vs 2% in the NCDS). This may indicate that it is becoming more common, although additional studies are needed to confirm this finding. Environmental factors including temperature and humidity, water hardness, pollution levels, and the environmental microbiome have been linked to atopic dermatitis and may vary geographically and temporally.33,36,37,38 Future research should examine the role of environmental factors on patterns and persistence of atopic eczema over time.

Breastfeeding was associated with a higher risk of all the atopic eczema subtypes in our study, and in utero smoke exposure was associated with a lower risk of the high subtype. In the literature, there have been mixed findings on these factors.39,40 Women with a history of atopy may be less likely to smoke and more likely to breastfeed, which could explain our results. Additionally, the timing and duration of smoking and breastfeeding are likely to be important, as well as potential confounding by social factors we were unable to control for in the present study. Given the constraints of historical data analysis, we were unable to further examine these issues. The health risks of smoking and benefits of breastfeeding are both well established, and the present study results should not be interpreted as implying otherwise.

Limitations

While this study relied on 2 large, generalizable cohorts with 5 decades of follow-up, it was also limited by missing data and lack of clinical detail. We performed multiple imputation to address missing early life data and did not identify patterns indicative of bias owing to attrition. The reliance on self-report of atopic eczema could result in misclassification bias. Self-report has been shown to reasonably approximate clinical assessment in childhood19,20 and physician diagnosis in adulthood,21 and is unlikely to be differential over time among individuals. Both cohorts had similar population-based designs, but the wording and timing of questions differed between cohorts (eTable 1 in the Supplement). A prior investigation did not find evidence of bias owing to changes in study design.41 A methodological limitation is that allocating individuals to their most likely latent class, then analyzing these classes as if they were observed, may overstate precision in the analytical models. However, given the high level of entropy and average posterior class membership probabilities, this is unlikely to be a major limitation.

We could not examine atopic eczema severity or how treatment patterns affect disease course, which is an important area for future research. For example, among adults with mild asthma, early initiation of inhaled corticosteroid treatment may improve long-term outcomes. As more systemic treatments become available for atopic eczema,42 randomized trials to examine whether these treatments affect disease trajectory are of utmost importance. The present study results help establish a baseline for long-term disease course.

Conclusions

When extending the window of observation beyond childhood, clear subtypes of atopic eczema based on patterns of disease activity emerged. In particular, a newly identified subtype with increasing probability of activity in adulthood warrants additional attention given associations with poor self-reported physical and mental health in midlife. Early-life factors shown to be associated with childhood atopic eczema overall did not help differentiate between subtypes, which raises the possibility that disease trajectory is modifiable and may be influenced by environmental factors throughout life.

eMethods

eFigure 1. Subtype interpretations by model

eFigure 2. Heat maps of individual participant disease patterns across ages, organized by subgroup from the latent class analysis

eTable 1. Questions about atopic eczema, asthma, and rhinitis by year and by cohort

eTable 2. Latent class fit statistics

eTable 3. Average classification probabilities by most likely disease trajectory subtype for the four-class solution

eTable 4. Proportions of individuals with atopic eczema, asthma, and rhinitis within each disease trajectory subtype with by cohort

eTable 5. Association between early life factors and atopic eczema activity subtypes by cohort

eTable 6. Complete case analysis. Association between early life factors and atopic eczema activity subtypes from for 1958 and 1970 meta-analysis

References

- 1.Johansson SG, Bieber T. New diagnostic classification of allergic skin disorders. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;2(5):403-406. doi: 10.1097/00130832-200210000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Odhiambo JA, Williams HC, Clayton TO, Robertson CF, Asher MI; ISAAC Phase Three Study Group . Global variations in prevalence of eczema symptoms in children from ISAAC Phase Three. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(6):1251-8.e23. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laughter MR, Maymone MBC, Mashayekhi S, et al. The global burden of atopic dermatitis: lessons from the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990-2017. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184(2):304-309. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roduit C, Frei R, Depner M, et al. ; the PASTURE study group . Phenotypes of atopic dermatitis depending on the timing of onset and progression in childhood. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(7):655-662. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.0556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thorsteinsdottir S, Stokholm J, Thyssen JP, et al. Genetic, clinical, and environmental factors associated with persistent atopic dermatitis in childhood. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155(1):50-57. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.4061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paternoster L, Savenije OEM, Heron J, et al. Identification of atopic dermatitis subgroups in children from 2 longitudinal birth cohorts. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(3):964-971. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2017.09.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belgrave DC, Granell R, Simpson A, et al. Developmental profiles of eczema, wheeze, and rhinitis: two population-based birth cohort studies. PLoS Med. 2014;11(10):e1001748. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu C, Duijts L, Erler NS, et al. Most associations of early-life environmental exposures and genetic risk factors poorly differentiate between eczema phenotypes: the Generation R Study. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181(6):1190-1197. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17879 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiesa Fuxench ZC, Block JK, Boguniewicz M, et al. Atopic dermatitis in america study: a cross-sectional study examining the prevalence and disease burden of atopic dermatitis in the US adult population. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139(3):583-590. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abuabara K, Magyari A, McCulloch CE, Linos E, Margolis DJ, Langan SM. Prevalence of atopic eczema among patients seen in primary care: data from the Health Improvement Network. Ann Intern Med. 2019;170(5):354-356. doi: 10.7326/M18-2246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silverberg JI, Hanifin JM. Adult eczema prevalence and associations with asthma and other health and demographic factors: a US population-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132(5):1132-1138. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.08.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abuabara K, Yu AM, Okhovat JP, Allen IE, Langan SM. The prevalence of atopic dermatitis beyond childhood: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Allergy. 2018;73(3):696-704. doi: 10.1111/all.13320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abuabara K, Margolis DJ, Langan SM. The long term course of atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35(3):291-297. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2017.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abuabara K, Ye M, McCulloch CE, et al. Clinical onset of atopic eczema: results from 2 nationally representative British birth cohorts followed through midlife. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144(3):710-719. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.05.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elliott J, Shepherd P. Cohort profile: 1970 British Birth Cohort (BCS70). Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(4):836-843. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Power C, Elliott J. Cohort profile: 1958 British birth cohort (National Child Development Study). Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(1):34-41. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hawkes D, Plewis I.. Modelling Non-Response in the National Child Development Study. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society). 2006;169(3): 479-491. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-985X.2006.00401.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mostafa T, Wiggins D. Handling attrition and non-response in the 1970 British Cohort Study. Centre for Longitudinal Studies Working Paper 2014/2. 2014. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10023946/1/CLS_WP_2014_T_Mostafa_and_R_Wiggins.pdf

- 19.Williams HC, Strachan DP, Hay RJ. Childhood eczema: disease of the advantaged? BMJ. 1994;308(6937):1132-1135. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6937.1132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams HC, Strachan DP. The natural history of childhood eczema: observations from the British 1958 birth cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139(5):834-839. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02509.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silverberg JI, Patel N, Immaneni S, et al. Assessment of atopic dermatitis using self-report and caregiver report: a multicentre validation study. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(6):1400-1404. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nylund KL, Asparouhov T, Muthén BO. Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: a Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2007;14(4):535-569. doi: 10.1080/10705510701575396 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor-Robinson DC, Williams H, Pearce A, Law C, Hope S. Do early-life exposures explain why more advantaged children get eczema? Findings from the U.K. Millennium Cohort Study. Br J Dermatol. 2016;174(3):569-578. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor B, Wadsworth J, Golding J, Butler N. Breast feeding, eczema, asthma, and hayfever. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1983;37(2):95-99. doi: 10.1136/jech.37.2.95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brazier JE, Harper R, Jones NM, et al. Validating the SF-36 health survey questionnaire: new outcome measure for primary care. BMJ. 1992;305(6846):160-164. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6846.160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ware J, KW S, M M, B G. SF36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. Lincoln, RI: Quality Metric, Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodgers B, Pickles A, Power C, Collishaw S, Maughan B. Validity of the Malaise Inventory in general population samples. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1999;34(6):333-341. doi: 10.1007/s001270050153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silverberg JI, Thyssen JP, Paller AS, et al. What’s in a name? Atopic dermatitis or atopic eczema, but not eczema alone. Allergy. 2017;72(12):2026-2030. doi: 10.1111/all.13225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flohr C, Johansson SG, Wahlgren CF, Williams H. How atopic is atopic dermatitis? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114(1):150-158. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.04.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bui DS, Lodge CJ, Perret JL, et al. Trajectories of asthma and allergies from 7 years to 53 years and associations with lung function and extrapulmonary comorbidity profiles: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(4):387-396. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30413-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Czarnowicki T, He H, Canter T, et al. Evolution of pathologic T-cell subsets in patients with atopic dermatitis from infancy to adulthood. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(1):215-228. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.09.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou L, Leonard A, Pavel AB, et al. Age-specific changes in the molecular phenotype of patients with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144(1):144-156. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McNally NJ, Williams HC, Phillips DR, Strachan DP. Is there a geographical variation in eczema prevalence in the UK? Evidence from the 1958 British Birth Cohort Study. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142(4):712-720. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03416.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gupta R, Sheikh A, Strachan DP, Anderson HR. Time trends in allergic disorders in the UK. Thorax. 2007;62(1):91-96. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.038844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schultz Larsen F, Hanifin JM. Secular change in the occurrence of atopic dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol Suppl (Stockh). 1992;176:7-12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jabbar-Lopez ZK, Ung CY, Alexander H, et al. The effect of water hardness on atopic eczema, skin barrier function: A systematic review, meta-analysis. Clin Exp Allergy. 2021;51(3):430-451. doi: 10.1111/cea.13797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bowatte G, Lodge C, Lowe AJ, et al. The influence of childhood traffic-related air pollution exposure on asthma, allergy and sensitization: a systematic review and a meta-analysis of birth cohort studies. Allergy. 2015;70(3):245-256. doi: 10.1111/all.12561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flohr C, Yeo L. Atopic dermatitis and the hygiene hypothesis revisited. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2011;41:1-34. doi: 10.1159/000323290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Friedman NJ, Zeiger RS. The role of breast-feeding in the development of allergies and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115(6):1238-1248. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.01.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kantor R, Kim A, Thyssen JP, Silverberg JI. Association of atopic dermatitis with smoking: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(6):1119-1125.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.07.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Butland BK, Strachan DP, Lewis S, Bynner J, Butler N, Britton J. Investigation into the increase in hay fever and eczema at age 16 observed between the 1958 and 1970 British birth cohorts. BMJ. 1997;315(7110):717-721. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7110.717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Uppal SK, Kearns DG, Chat VS, Han G, Wu JJ. Review and analysis of biologic therapies currently in phase II and phase III clinical trials for atopic dermatitis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;1-11. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1775775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods

eFigure 1. Subtype interpretations by model

eFigure 2. Heat maps of individual participant disease patterns across ages, organized by subgroup from the latent class analysis

eTable 1. Questions about atopic eczema, asthma, and rhinitis by year and by cohort

eTable 2. Latent class fit statistics

eTable 3. Average classification probabilities by most likely disease trajectory subtype for the four-class solution

eTable 4. Proportions of individuals with atopic eczema, asthma, and rhinitis within each disease trajectory subtype with by cohort

eTable 5. Association between early life factors and atopic eczema activity subtypes by cohort

eTable 6. Complete case analysis. Association between early life factors and atopic eczema activity subtypes from for 1958 and 1970 meta-analysis