Abstract

Objectives

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has left older adults around the world bereaved by the sudden death of relatives and friends. We examine if COVID-19 bereavement corresponds with older adults’ reporting depression in 27 countries and test for variations by gender and country context.

Method

We analyze the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe COVID-19 data collected between June and August 2020 from 51,383 older adults (age 50–104) living in 27 countries, of whom 1,363 reported the death of a relative or friend from COVID-19. We estimate pooled multilevel logit regression models to examine if COVID-19 bereavement is associated with self-reported depression and worsening depression, and we test whether national COVID-19 mortality rates moderate these associations.

Results

COVID-19 bereavement is associated with significantly higher probabilities of both reporting depression and reporting worsened depression among older adults. Net of one’s own personal loss, living in a country with the highest COVID-19 mortality rate is associated with women’s reports of worsened depression but not men’s. However, the country’s COVID-19 mortality rate does not moderate associations between COVID-19 bereavement and depression.

Discussion

COVID-19 deaths have lingering mental health implications for surviving older adults. Even as the collective toll of the crisis is apparent, bereaved older adults are in particular need of mental health support.

Keywords: Bereavement, COVID-19, Depression, Disaster, Gender

Background

The ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic is a mortality shock of historic proportion, responsible for more than 2.5 million deaths worldwide in a single year (Johns Hopkins University, n.d.). Bereavement is the loss of a person or thing that was valued (Corr et al., 2000). Each COVID-19 death leaves behind numerous others bereaved: the unprecedented rise in mortality during the pandemic has produced a corresponding rise in those coping with the loss of loved ones, especially among older adults. For instance, estimates from the United States suggest that each COVID-19 death results in an average of nine close relatives bereaved and that older adults are the most likely age group to experience the loss of a parent, child, sibling, or spouse (Verdery et al., 2020). The tendency for individuals to socialize with others of similar ages (McPherson et al., 2001), combined with the concentration of COVID-19 deaths among older adults, also means that this age group is most at risk of experiencing the death of friends from this disease.

Stroebe and colleagues (2006) provide an integrative risk factor framework to understand bereavement adjustments and outcomes. This framework posits that various stressors stemming from bereavement correspond with a range of poor health outcomes, from mental health problems to elevated mortality risk (Elwert & Christakis, 2008a, 2008b; Stroebe et al., 2007). In the short term, the health challenges associated with bereavement can manifest as mental health problems, which often foreshadow physical health declines (Domingue et al., 2021). Research highlights adverse consequences of COVID-19 mitigation strategies (quarantine, social distancing) for older adults’ mental health (Czeisler et al., 2021; Pfefferbaum & North, 2020; Simon et al., 2020), while related work draws attention to COVID-19 bereavement among older adults (Carr et al., 2020; Stroebe & Schut, 2021). However, we lack population-based evidence that COVID-19 bereavement is associated with adverse mental health, especially for older adults.

COVID-19 fatalities commonly involve physical discomfort, unexpectedness, medical interventions, and isolation at the time of death (Carr et al., 2020)—all factors that could make bereavement more difficult for those left behind (Krikorian et al., 2020). The knowledge that one’s friend or relative suffered, or the inability to say goodbye, may leave the bereaved from COVID-19 especially vulnerable to poor mental health (Carr et al., 2020). We use survey data collected from older adults in 27 countries during the initial height of the crisis (June to August 2020) to provide population-based evidence of the national prevalence of older adult bereavement in the face of COVID-19 (Research Question 1). The emotional turmoil associated with bereavement could be heightened in the midst of the pandemic, a time when the social fabric has been weakened. Thus, we analyze these survey data to test for associations between COVID-19 bereavement and self-reports of depression, paying mind to potential variation across types of bereavement (nonfamily vs family bereavement; Research Question 2).

Theoretical models in sociology and disaster response offer a second theoretical framework to understand the mental health toll of national crises (Barton, 1969; Collins, 2004), but its theoretical propositions offer a mix of expectations about how national COVID-19 severity might independently associate with mental health or else moderate individual bereavement and mental health associations. We leverage the cross-national nature of the data to examine these ideas. Even as the COVID-19 pandemic is a global crisis, its national severity has varied dramatically. In countries with severe epidemics, older adults may suffer from poor mental health more generally—even absent firsthand bereavement (Shultz et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2021). That is, the collective nature of the crisis could lead to worse health for the majority of older adults, not just those personally bereaved. Living in a country with a higher COVID-19 mortality rate could worsen mental health among older adults due to their greater risk perceptions or fear, or their having to more dramatically alter their day-to-day lives in response to personal virus avoidance strategies or government mandates.

Beyond a potential direct impact, the collective toll and personal experiences of COVID-19 mortality could combine to be especially challenging for older adults. Navigating a personal loss may be particularly taxing where COVID-19 is more severe and the death toll is higher, and thus suffering is palpable, daily routines more severely disrupted, and fear runs especially high. The reverse may also be true, however, as sociological theories speculate that communal tragedies (wars, terrorist attacks, and pandemics) can spur social solidarity, providing resilience to those experiencing the tragedy most acutely (Barton, 1969; Collins, 2004). In light of these arguments, we examine the role of country-level COVID-19 mortality rates (proxying national crisis severity) as independent correlates or moderators of the association between personal COVID-19 bereavement and mental health among older adults (Research Question 3).

Experience and reactions to bereavement could also be highly gendered. Among older adults, women are likely at elevated risk of COVID-19 bereavement relative to men, both because of higher spousal loss due to men’s higher mortality from COVID-19 (Gebhard et al., 2020) and higher friend loss, given women tend to have larger social networks (Cornwell et al., 2008). Recent reports find women spend more time worrying, thinking, and talking about COVID-19 than men (Barber & Kim, 2021), and generally have had worse mental health during the pandemic (Pierce et al., 2020). Thus, we investigate potential gender differences in COVID-19 bereavement and mental health among older adults (Research Question 4).

Method

Data

We use data from the long-running Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) COVID-19 survey (Börsch-Supan, 2020). Since 2004, SHARE has collected data on older adults’ health and well-being, demographic characteristics, and family and social networks. The panel study sample is refreshed with new respondents at each wave, producing nationally representative samples of individuals aged 50 and older in each country.

The COVID-19 crisis hit during regular SHARE data collection, forcing in-person interviews to a halt. At the time, approximately 30% of the panel sample and 50% of the refresher sample interviews were outstanding. To respond, survey administrators pivoted their efforts to collect time-sensitive data about the crisis among the uninterviewed Wave 8 participants (see http://www.share-project.org/special-data-sets/share-covid-19-questionnaire.html). The SHARE COVID-19 survey was administered over the phone between June and August 2020. In addition to a condensed version of the standard SHARE questionnaire, respondents answered questions about life events and changes during the pandemic. Of the 52,310 SHARE COVID respondents, we have valid, nonmissing data on 51,383 (98.23%) respondents from 27 countries, who comprise our final analytic sample (see Supplementary Table 1 for descriptive information).

Measures

Self-reports of depression

Respondents were asked yes or no to the question “In the last month, have you been sad or depressed?”; this question is one item from the EURO–Depression scale, the only depression item administered in the SHARE COVID-19 survey (Guerra et al., 2015; Prince et al., 1999). For those indicating yes to this question, they were further asked to compare their depression to pre-pandemic status. We generate two binary measures: (a) current depression (1 = reporting sad or depressed in the last month) and (b) worsening depression (1 = reporting sad or depressed in the last month and feeling more sad or depressed relative to pre-pandemic). Because many SHARE COVID-19 survey respondents are refresher interviews, not panel interviews, we focus on reported changes rather than controlling for prior wave reports of depressive symptoms. We conduct a sensitivity check that controlled for prior reports of depression and sociodemographic characteristics (education and income) among the subset of respondents present in Wave 6 survey and found substantively identical results to what we present here.

COVID-19 bereavement

Respondents report whether anyone close to them died of an infection from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), and if so, their relationship to the deceased. With this information, we generate three binary measures: (a) any bereavement; (b) any family bereavement (spouse, parents, children, household members, and other relatives); and (c) any nonfamily bereavement (friends, caregivers, and others).

Country-level mortality

For each of the 27 countries, we use World Health Organization (WHO) data on (a) total COVID-19 deaths and (b) total population size to measure COVID-19 mortality rates during the study period, specifically up to August 31, 2020 to account for potential reporting delays (WHO, 2020). We group these rates into quartiles, allowing us to capture potential nonlinearity. We also control for each country’s all cause pre-pandemic mortality rate using the most recently available 2018 data for Europe (European Union Statistical Office, n.d.) and 2016 data for Israel (Ministry of Health Israel, 2016).

Individual controls

We control for key sociodemographic characteristics, including respondents’ age, gender, partnership status, number of household members, employment status and self-rated health (pre-pandemic status), and number of chronic conditions (hip fracture, diabetes, hypertension, heart attack, chronic lung diseases, cancer, and other major illness).

Analytic Strategy

First, we describe country-specific prevalence of COVID-19 mortality and bereavement across countries, which we contextualize against baseline mortality rates from pre-COVID years. We use SHARE person-level weights in our estimates of bereavement prevalence. To examine associations between individual COVID-19 bereavement, country-level COVID-19 mortality, and reports of depression, we pool 27 countries to estimate multilevel logit regression models (Snijders & Bosker, 2012) that account for individuals’ nesting within countries.

Results

Table 1 presents estimates of national rates of COVID-19 mortality and COVID-19 bereavement within each focal country as of summer 2020. COVID-19 mortality rates vary substantially between countries, reflecting epidemic severity, with some countries having COVID-19 mortality rates greater than or equal to 50% of baseline mortality (Belgium, Spain, Sweden, Italy, and France) and others having COVID-19 mortality rates less than 2% of baseline mortality (Slovakia and Latvia).

Table 1.

The Bereavement Toll of COVID-19 Mortality Among Older Adults in SHARE Countries, Contextualized Against National Rates of COVID-19 Mortality and Baseline National Mortality Rates

| National rates | COVID-19 bereavement | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Sample size | COVID-19 mortality (per 1,000) |

Baseline mortality (per 1,000) |

Any network death (%) |

Family death (%) |

Nonfamily death (%) |

| Belgium | 3,758 | 8.53 | 9.70 | 9.85 | 3.19 | 6.86 |

| Spain | 2,041 | 6.20 | 9.11 | 4.41 | 2.26 | 2.21 |

| Italy | 3,688 | 5.87 | 10.47 | 7.04 | 1.65 | 5.35 |

| Sweden | 1,355 | 5.76 | 9.11 | 5.17 | 1.97 | 3.19 |

| France | 2,030 | 4.67 | 9.07 | 3.45 | 1.63 | 1.95 |

| The Netherlands | 780 | 3.63 | 8.96 | 6.19 | 2.15 | 4.03 |

| Switzerland | 1,869 | 1.99 | 7.91 | 6.14 | 2.41 | 4.34 |

| Luxembourg | 923 | 1.98 | 6.96 | 6.11 | 1.86 | 4.91 |

| Romania | 1,464 | 1.84 | 13.52 | 0.49 | 0.11 | 0.38 |

| Portugal | 1,107 | 1.78 | 10.99 | 1.69 | 0.07 | 1.62 |

| Germany | 2,643 | 1.11 | 11.53 | 1.76 | 0.73 | 1.02 |

| Denmark | 1,974 | 1.08 | 9.55 | 1.58 | 0.37 | 1.16 |

| Israel | 1,440 | 1.02 | 4.95 | 2.37 | 0.72 | 1.65 |

| Bulgaria | 803 | 0.87 | 15.39 | 0.54 | — | 0.54 |

| Hungary | 992 | 0.64 | 13.42 | 0.59 | — | 0.59 |

| Slovenia | 3,104 | 0.62 | 9.91 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| Finland | 1,455 | 0.60 | 9.89 | 0.89 | 0.07 | 0.82 |

| Poland | 2,906 | 0.54 | 10.91 | 0.83 | 0.22 | 0.53 |

| Estonia | 4,506 | 0.48 | 11.94 | 0.38 | 0.27 | 0.11 |

| Croatia | 1,996 | 0.45 | 12.84 | 0.11 | — | 0.11 |

| Czech Republic | 2,605 | 0.39 | 10.64 | 0.33 | 0.33 | — |

| Lithuania | 1,254 | 0.32 | 14.09 | — | — | — |

| Greece | 3,610 | 0.25 | 11.20 | 0.08 | — | 0.08 |

| Malta | 820 | 0.23 | 7.76 | 1.34 | 0.21 | 1.13 |

| Latvia | 960 | 0.18 | 14.90 | — | — | — |

| Cyprus | 780 | 0.17 | 6.68 | 0.4 | 0.4 | — |

| Slovakia | 932 | 0.06 | 3.76 | — | — | — |

| Total | 51,795 | 3.26 | 1.15 | 2.14 |

Notes: COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019; SHARE = Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe. Sorted by COVID-19 mortality rates. National rates of COVID-19 mortality are based on World Health Organization data (August 31, 2020); national rates of baseline mortality are from the statistical office of the European Union (Eurostat), updated as of September 10, 2020, reporting total deaths in 2018 (except for Israel, 2016 death data from Israel Ministry of Health). Percentages of respondents experiencing COVID-19 deaths in their overall network, family network, or nonfamily network are weighted based on SHARE (June to August, 2020); dashes denote estimates where zero respondents reported experiencing such a death. Family deaths include spouses, parents, children, other household members, and relatives. Nonfamily deaths include friends, caregivers, and others.

On average, a weighted 1.15% and 2.14% of older adults in SHARE countries reported at least one family and nonfamily COVID-19 bereavement, respectively. In selected countries, over 5% of older adults reported any network COVID-19 bereavement (Belgium, Italy, the Netherlands, Switzerland, Luxembourg, and Sweden). As expected, the countries with the highest prevalence of COVID-19 bereavement are also the ones with the highest COVID-19 mortality rates. The correlations between country-level COVID-19 mortality rates and any (.86), family (.86), and nonfamily (.80) COVID-19 bereavement are uniformly high (these correlations assume that countries with no bereavement reports have 0% bereavement).

The first panel of Table 2 displays average marginal effects (AMEs) from multilevel logit models of depression. Model 1 shows that on average older adults who had COVID-19 bereavement were 6 percentage points more likely to report depression than those with no such bereavement, net of the country mortality and individual controls. Model 2, which disaggregates any COVID-19 bereavement into family and nonfamily bereavement, shows both are associated with higher probability of reporting depression than no bereavement, with family bereavement having a slightly larger association (AME = 0.08) than nonfamily (AME = 0.05); however, this difference is not statistically significant (χ 2(1) = 1.27, p = .26). In supplementary analysis (Model 1 of Supplementary Table 2), we examined if the association between COVID-19 bereavement and depression varies by gender and found no significant differences.

Table 2.

Average Marginal Effects From Multilevel Logit Regression Models for COVID-19 Bereavement and Self-Report Depression Among Older Adults

| Felt sad or depressed in the last month | Felt more sad or depressed than pre-COVID-19 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (full sample) |

Model 2 (full sample) |

Model 3 (female) |

Model 4 (male) |

Model 5 (full sample) |

Model 6 (full sample) |

Model 7 (female) |

Model 8 (male) |

|

| Any network bereavementa | 0.06*** | — | 0.07*** | 0.06*** | 0.06*** | — | 0.07*** | 0.06*** |

| Family bereavement | — | 0.08*** | — | — | — | 0.08*** | — | — |

| Nonfamily bereavement | — | 0.05*** | — | — | — | 0.05*** | — | — |

| National COVID-19 mortality | ||||||||

| First quartile (ref) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Second quartile | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | −0.00 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.02 |

| Third quartile | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

| Fourth quartile | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.06* | 0.01 | 0.05* | 0.05* | 0.08* | 0.01 |

| Control variables | ||||||||

| Age | ||||||||

| 50–59 (ref.) | ||||||||

| 60–69 | −0.02** | −0.02** | −0.02* | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 |

| 70–79 | −0.02*** | −0.02** | −0.01 | −0.03** | −0.02** | −0.02** | −0.01 | −0.02* |

| 80+ | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.00 |

| Female (male) | 0.12*** | 0.12*** | — | — | 0.09*** | 0.09*** | — | — |

| Partnered (unpartnered) | −0.06*** | −0.06*** | −0.06*** | −0.06*** | −0.01*** | −0.01*** | −0.02** | −0.02*** |

| Household size | −0.01* | −0.01* | −0.02* | −0.00 | −0.01** | −0.01** | −0.01* | −0.00 |

| Employed (not employed) | −0.03*** | −0.03** | −0.03*** | −0.03** | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 | −0.01 |

| Poor self-rated healthb | 0.15*** | 0.15*** | 0.16*** | 0.14*** | 0.09*** | 0.09*** | 0.09*** | 0.08*** |

| Number of chronic conditionsc | 0.05*** | 0.05*** | 0.05*** | 0.05*** | 0.03*** | 0.03*** | 0.03*** | 0.03*** |

| Baseline mortalityd | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.04 | −0.01 |

| Intercept | −1.55*** | −1.55*** | −0.91** | −1.48*** | −2.16*** | −2.16*** | −1.46*** | −2.17*** |

| Random effects | ||||||||

| Intercept variance | 0.09*** | 0.09*** | 0.10*** | 0.08*** | 0.10*** | 0.10*** | 0.10*** | 0.10*** |

Notes: COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019. N = 51,383; country N = 27.

aReference group is respondents not reporting COVID-19 deaths of each type.

bReference group is self-reported good, very good, or excellent health.

cSum of seven chronic conditions.

dEstimates multiplied by 100 to reduce leading zeros.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

As shown in Models 1 and 2, we found no significant association between the national COVID-19 mortality rate and reports of depression in the full sample. However, gender-specific models (Models 3 and 4) confirm that there is an association among women only. As shown in Model 3, women living in countries with the highest COVID-19 mortality rates (fourth quartile) are more likely to report current depression than women residing in countries with the lowest COVID-19 mortality rate. Significant interaction terms between gender and national COVID-19 mortality (Model 1 of Supplementary Table 3) suggest that compared to older men, living in higher COVID-19 mortality countries indeed has a more negative association for older women.

As shown in the second panel of Table 2, COVID-19 bereavement also corresponds with self-reported worsened depression: older adults who experienced any, family, or nonfamily COVID-19 bereavement have higher probabilities of reporting worsening depression than those with no such bereavement (Models 5 and 6). Additionally, Models 5 and 6 highlight the importance of country-level COVID-19 mortality conditions in older adults’ trajectory of depression: net of their own experience of a personal loss, older adults living in countries with higher COVID-19 mortality rates are more likely to report worsening depression. Disaggregating by gender (Models 7 and 8) again confirms that this association is only significant among women (Model 2 of Supplementary Table 3 for interaction results).

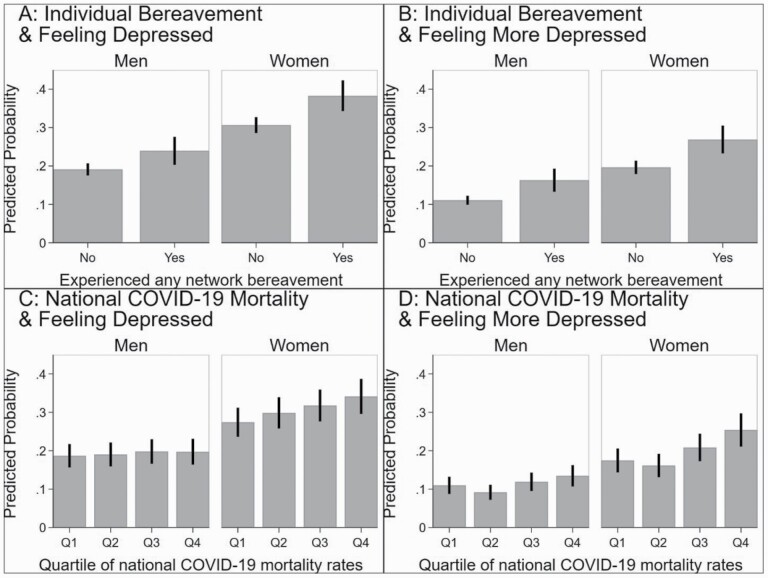

Figure 1 shows predicted probabilities to further summarize the key findings. Figure 1A shows that nonbereaved men ( = 0.19; 95% CI = [0.17, 0.21]) have the lowest probability of reporting current depression, followed by nonbereaved women ( = 0.24; 95% CI = [0.20, 0.27]), then bereaved men ( = 0.31; 95% CI = [0.28, 0.33]), and finally bereaved women ( = 0.38; 95% CI = [0.34, 0.42]). Figure 1B confirms these same patterns for worsening depression. Figure 1C shows that, for men, being in countries with different COVID-19 mortality rates is not associated with variations in current depression. However, there are stark differences for women in addition to a higher baseline rate: compare women in countries with low, first quartile mortality rates ( = 0.27; 95% CI = [0.23, 0.32]) to women in those with high, fourth quartile rates ( = 0.34; 95% CI = [0.28, 0.39]). Figure 1D offers a comparable but more muted result for worsening depression.

Figure 1.

Predicted probability of reporting current and worsening depression by individual network bereavement and national COVID-19 mortality rates. COVID-19 = coronavirus disease 2019.

Last, we examine if living in a country with a higher COVID-19 mortality rate not only directly elevates women’s probability of reporting depression but also amplifies the consequence of personal bereavement (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5). We found no significant interaction terms between country-level COVID-19 mortality and individual bereavement, highlighting the independent effect of personal bereavement.

Discussion

These results add to the growing recognition of the mental health consequences of the COVD-19 pandemic, especially for older women (Pierce et al., 2020). Distinct from past studies that emphasize adverse influences of lockdowns, social distancing, and school closures on population mental health, our research directly examines the association between the mortality crisis and mental health for older adults using population-based data from a wide range of countries. That older women’s reports of depression are associated with both the collective and personal toll of COVID-19 mortality emphasizes the need for community-based screening to identify the adults most in need of intervention in the most severely affected countries. These results should be interpreted with caution, given that we could not account for other types of bereavement (such as accidental death) due to data constraints. However, given the bereavement implications of the worldwide pandemic, the mental health associations we document are quite concerning.

Even as our study offers the first analysis of cross-national mental health consequences of COVID-19 bereavement, the results come with limitations. The outcome variables are retrospective, self-reported measures of any recent or worsening feelings of depression or sadness; older adults who we code as presenting with self-reported depression may not meet clinical thresholds. Moreover, although we explore older adults’ self-reports of depression compared to pre-pandemic status, offering insights into the influence of COVID-19 bereavement on changes in depression, our cross-sectional, observational design precludes drawing causal conclusions. In addition, multilevel model results should be interpreted with caution when the number of groups at Level 2 (e.g., country clusters) is limited (Bryan & Jenkins, 2016). Unmeasured confounding variables may include appraisal and coping styles, individual personality, family dynamics, religious practice, and cultural background (Stroebe et al., 2006). The lockdown policy, social welfare system, and other formal support from governments may also play important roles in older adults’ COVID-19 experience and bereavement reactions.

This study offers a temporally abbreviated view of mental health consequences of COVID-19 bereavement. There is a reason to suspect that these results foreshadow the pandemic’s lingering mental health effects. Research shows that depressive symptoms immediately following bereavement can predict physical health problems down the line (Domingue et al., 2021). Targeted efforts to address COVID-19 bereavement may especially benefit older women in countries with severe COVID-19 mortality crises, as well as those personally affected.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Haowei Wang, Department of Sociology and Criminology, Population Research Institute, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, USA.

Ashton M Verdery, Department of Sociology and Criminology, Population Research Institute, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, USA.

Rachel Margolis, Department of Sociology, University of Western Ontario, London, Canada.

Emily Smith-Greenaway, Department of Sociology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, USA.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (1R01AG060949) and the Pennsylvania State University Population Research Institute, which is supported by an infrastructure grant by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P2C-HD041025). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or other funding sources.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Barber, S. J., & Kim, H. (2021). COVID-19 worries and behavior changes in older and younger men and women. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 76(2):e17–e23. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbaa068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton, A. (1969). Communities in Disaster: A Sociological Analysis of Collective Stress. Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Börsch-Supan, A. (2020). Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 8. COVID-19 Survey 1. Release version: 0.0.1. beta. SHARE-ERIC. Data set. doi: 10.6103/SHARE.w8cabeta.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryan, M. L., & Jenkins, S. P. (2016). Multilevel modelling of country effects: A cautionary tale. European Sociological Review, 32(1), 3–22. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcv059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carr, D., Boerner, K., & Moorman, S. (2020). Bereavement in the time of coronavirus: Unprecedented challenges demand novel interventions. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 32(4–5), 425–431. doi: 10.1080/08959420.2020.1764320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins, R. (2004). Rituals of solidarity and security in the wake of terrorist attack. Sociological Theory, 22(1), 53–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9558.2004.00204.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwell, B., Laumann, E. O., & Schumm, L. P. (2008). The social connectedness of older adults: A national profile. American Sociological Review, 73(2), 185–203. doi: 10.1177/000312240807300201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corr, C. A., Nabe, C. M., & Corr, D. M. (2000). Death and dying, life and living (3rd ed.). Wadsworth/Thomson Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Czeisler, M. É., Howard, M. E., & Rajaratnam, S. M. W. (2021). Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Challenges, populations at risk, implications, and opportunities. American Journal of Health Promotion, 35(2), 301–311. doi: 10.1177/0890117120983982b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domingue, B. W., Duncan, L., Harrati, A., & Belsky, D. W. (2021). Short-term mental health sequelae of bereavement predict long-term physical health decline in older adults: US Health and Retirement Study Analysis. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 76(6):1231–1240. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbaa044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwert, F., & Christakis, N. A. (2008a). The effect of widowhood on mortality by the causes of death of both spouses. American Journal of Public Health, 98(11), 2092–2098. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.114348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwert, F., & Christakis, N. A. (2008b). Wives and ex-wives: A new test for homogamy bias in the widowhood effect. Demography, 45(4), 851–873. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Union Statistical Office . (n.d.). Mortality database.https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/view/demo_mmonth/default/table?lang=en

- Gebhard, C., Regitz-Zagrosek, V., Neuhauser, H. K., Morgan, R., & Klein, S. L. (2020). Impact of sex and gender on COVID-19 outcomes in Europe. Biology of Sex Differences, 11, 29. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0390-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerra, M., Ferri, C., Llibre, J., Prina, A. M., & Prince, M. (2015). Psychometric properties of EURO-D, a geriatric depression scale: A cross-cultural validation study. BMC Psychiatry, 15(1), 1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12888-015-0390-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns Hopkins University . (n.d.). COVID-19 Dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU).https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

- Krikorian, A., Maldonado, C., & Pastrana, T. (2020). Patient’s perspectives on the notion of a good death: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 59(1), 152–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.07.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. M. (2001). Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 415–444. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.415 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health Israel . (2016). Mortality in Israel.https://statistics.health.gov.il/views/DeathCauses/MortalityinIsrael?:embed=y&Language%20Desc=English

- Pfefferbaum, B., & North, C. S. (2020). Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. New England Journal of Medicine, 383(6), 510–512. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, M., Hope, H., Ford, T., Hatch, S., Hotopf, M., John, A., Kontopantelis, E.,Webb, R., Wessely, S., McManus, S., & Abel, K. M. (2020). Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(10), 883–892. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince, M. J., Reischies, F., Beekman, A. T., Fuhrer, R., Jonker, C., Kivela, S. L., Lawlor, B. A., Lobo, A., Magnusson, H., Fichter, M., van Oyen, H., Roelands, M., Skoog, I., Turrina, C., & Copeland, J. R. (1999). Development of the EURO-D scale—A European Union initiative to compare symptoms of depression in 14 European centres. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 174(4), 330–338. doi: 10.1192/bjp.174.4.330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shultz, J. M., Baingana, F., & Neria, Y. (2015). The 2014 Ebola outbreak and mental health: Current status and recommended response. Journal of the American Medical Association, 313(6), 567–568. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.17934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon, N. M., Saxe, G. N., & Marmar, C. R. (2020). Mental health disorders related to COVID-19–related deaths. Journal of the American Medical Association, 324(15), 1493–1494. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.19632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snijders, T. A. B., & Bosker, R. J. (2012). Multilevel analysis: An introduction to basic and advanced multilevel modeling (2nd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe, M. S., Folkman, S., Hansson, R. O., & Schut, H. (2006). The prediction of bereavement outcome: Development of an integrative risk factor framework. Social Science & Medicine, 63(9), 2440–2451. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.06.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe, M., Schut, H., & Stroebe, W. (2007). Health outcomes of bereavement. The Lancet, 370(9603), 1960–1973. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61816-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe, M., & Schut, H. (2021). Bereavement in times of COVID-19: A review and theoretical framework. OMEGA—Journal of Death and Dying, 82(3), 500–522. doi: 10.1177/0030222820966928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdery, A. M., Smith-Greenaway, E., Margolis, R., & Daw, J. (2020). Tracking the reach of COVID-19 kin loss with a bereavement multiplier applied to the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 117(30), 17695–17701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2007476117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H., Stokes, J. E., & Burr, J. A. (2021). Depression and elevated inflammation among Chinese older adults: Eight years after the 2003 SARS epidemic. The Gerontologist, 61(2), 273–283. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnaa219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) . (2020). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Weekly Epidemiological Update.https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200831-weekly-epi-update-3.pdf?sfvrsn=d7032a2a_4

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.