Abstract

About a fifth of individuals with colorectal cancer (CRC) present with disease metastasis at the time of diagnosis. While the role of the tumor microenvironment (TME) in governing CRC progression is undeniable, the role of the TME in either establishing or suppressing the formation of distant metastases of CRC is less well established. Despite advances in immunotherapy, many individuals with metastatic CRC do not respond to standard-of-care therapy. Therefore, understanding the role of the TME in establishing distant metastases is essential for developing new immunological agents. Here, we summarize our current understanding of the TME of CRC metastases, describe differences between the TME of primary tumors and their distant metastases, and discuss advances in the design and combinations of immunotherapeutic agents.

Keywords: : bi-specific T-cell engagers, CAR-T-cell therapy, colorectal cancer, dendritic cell vaccine, immune checkpoint inhibitors, immune microenvironment, liver metastases, metastasis, microsatellite instability, Toll-like receptor agonists

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third-leading cause of cancer-related deaths in men and women in the USA with roughly 20% of individuals presenting with stage IV disease, in other words, the presence of primary tumors with synchronous metastases at the time of diagnosis [1,2]. A higher incidence of late-stage disease is also observed in African–Americans than non-Hispanic whites [3]. Although the risk of developing CRC increases with age, the incidence in people younger than age 50 is increasing, and these younger individuals are more likely to present with late-stage metastatic disease [3,4]. An examination of the patterns of metastasis from colon and rectal cancer to specific sites shows liver is the most common site of metastasis (70% in colon and rectal cancer) followed by the thorax and lungs (32% in colon and 47% in rectal cancer), peritoneal cavity (21% in colon cancer) and bone (12% in rectal cancer) [1]. Different subtypes of CRC also exhibit specific patterns of metastasis, with mucinous and signet ring cell adenocarcinomas metastasizing to the peritoneal cavity at higher rates than to the liver [1]. Overall, the 5-year relative survival rate of colorectal cancer patients with distant metastases is 14–15% [3]. The poor prognosis for patients with mCRC thus highlights the urgent need for more effective treatments. Tremendous gains have been made in recent years in achieving long-term responses using immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) for solid tumors, such as melanoma, non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and renal cell cancer. However, response to immunotherapy for CRC particularly for metastatic disease, has not been effective with the exception of 13–16% of colorectal tumors that are mismatch-repair-deficient (dMMR) or exhibit microsatellite instability (MSI-H) for which ICI therapy has been very successful with up to 50% of patients responding to treatment [5,6]. MMR deficiency is the loss of one or more enzymes that identify and repair mismatched nucleotides during DNA recombination or DNA damage. Inactivation of MMR genes or MMR protein dysfunction can result in the hypermutability of tandem repeat sequences known as microsatellites [7]. Because most CRCs and metastases of CRC do not exhibit dMMR, there remains an urgent need to develop better therapeutic targets for these cancers and their derivative metastases [8,9]. As such, this review will focus on describing approaches to treating mCRC and specifically distant metastases of CRC originating from microsatellite stable (MSS) tumors based on modulation of the TME.

Molecular features of primary CRC & metastases of CRC

There are several molecular classification schemes for CRC. CRC is broadly classified based on MSI-H/dMMR status of the primary tumor with MSI-H/dMMR tumors exhibiting distinct genetic and phenotypic traits [10]. MSI-H/dMMR are tumors with failure to repair errors in repetitive DNA sequences. This can result from mutations in DNA mismatch repair genes such as MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2 and POLE, or somatic epigenetic inactivation of MLH1 due to hypermethylation of its gene promotor. Although MSI/dMMR features are observed in only 13–16% of sporadic cases of CRC, it is observed in 90% of patients with Lynch Syndrome or hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal carcinoma (HNPCC) [10]. Moreover, MSI-H tumors are typically found in the proximal colon, and exhibit mucinous features, high lymphocytic Crohn's like lymphoid reaction and high immune infiltration [11,12]. Immune infiltration of CRC is characterized by CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, which activate IFN-γ producing Th1 cells, and exhibit a strong upregulation of multiple immune checkpoint molecules including PD-1, PD-L1, CTLA4, LAG3 and IDO [13]. Given the defects in DNA repair machinery, these tumors are likely to have a higher somatic mutation rate and therefore a higher neoantigen burden [11,14–16]. As such, patients with dMMR CRC may be responsive to immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy [6,15,17]. This led to multiple clinical trials demonstrating persistent objective response rates in patients with dMMR/MSI-H tumors after treatment with ICIs, such as anti-PD-1, which finally culminated in the rapid approval for the first-ever tissue-agnostic therapy, pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1), by the US FDA in 2017 for patients with unresectable or metastatic MSI-H/dMMR tumors refractory to first-line therapy. Given this enormous therapeutic progress, new guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommend that all patients with newly diagnosed CRC should be tested for dMMR/MSI [18].

Despite these advances, it is important to note that only 3.5–5% of mCRC tumors are MSI-H/dMMR [19] and that therapeutic limitations exist even within the subset of metastatic MSI-H tumors due to changes in the TME. Across 11 tumor types known to exhibit the MSI-H phenotype, including CRC, only 4–5% are dMMR/MSI stage IV tumors [6,17]. MSI-H tumors typically do not present at diagnosis with synchronous metastases [17]. Importantly however, there is a strong concordance rate between MSI mutations observed in the primary CRC and metastases of CRC within a patient [20]. Moreover, although MSI-H tumors are more likely to exhibit increased immune infiltration, prominent immune gene expression and immune infiltration can be observed in MSS tumors as well. These immune features are independent and superior predictors of disease progression, disease relapse and overall survival than MSI status [21–23]. This observation underscores the working hypothesis that immunological features of MSI-H tumors, such as CD8+ T cell, and CD4+ helper T-cell tumor infiltration, are the potent drivers guiding disease prognosis. Furthermore, 45% of patients with MSI-H tumors are not responsive to ICI therapy, and 10–28% of all patients remain refractory to immunotherapy [15,24]. Innate resistance to ICI therapy in MSI-H tumors was recently observed in a patient with progressive CRC and multiple distant metastases where the primary tumor contained high natural killer (NK) cells and M2 macrophage infiltration despite having typical MSI-H molecular features [25] such as high neoantigen load. The high M2 macrophage infiltration is thought to suppress NK cell activity and suggests an immunosuppressive TME can promote resistance to immunotherapy with ICIs even in the setting of MSI.

MSS CRC tumors exhibit greater genomic heterogeneity compared with MSI-H tumors. MSS tumors are more frequently observed in the distal colon and rectum, and they are also more likely to have higher copy number instability (CIN) than MSI-H tumors [26]. While patients with MSI-H primary CRC have overall better disease-free survival compared with patients with MSS CRC, they have worse overall survival after relapse and recurrent MSI-H CRC is often associated with peritoneal metastases, which have a worse prognosis than MSS tumors [27,28]. Within stage IV disease, studies have demonstrated that there is no significant difference in disease-specific survival between MSI-H and MSS CRC [29]. However, administration of ICI therapy has significantly improved the prognosis of patients with metastatic stage IV MSI-H CRC. With regards to therapeutic associations, high-risk stage II and lymph-node positive stage III MSS CRC responds better to standard chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) than MSI-H tumors [30]. Overall, the genomic and transcriptomic heterogeneity of MSS tumors may underpin their poor prognosis and increased propensity to metastasize.

Outside of MSI stratification, there are several other molecular classification schemes for CRC. The most prominent of these has been the Consensus Molecular Subtype (CMS) classification system based on gene expression patterns observed in CRC tumors [27]. CMS classification is currently being used to stratify patients in clinical trials (NCT03436563). There are four distinct CMS groups with associated transcriptomic and genomic features. CRC can be classified into one of these four subtypes or is found to be mixtures of these four subtypes. CMS1 tumors, consisting of 14% of all CRCs, are typically hypermutated MSI-H tumors with a strong immune activation signature. CMS1 tumors are also associated with BRAF mutations and worse survival after disease relapse compared with other CMS groups. CMS2 tumors, found in 37% of all CRCs, are defined by WNT and MYC activation and high somatic copy number alterations (SCNAs) [27]. Patients with CMS2 tumors also exhibited superior survival after relapse with long-term survivorship. Interestingly, classification of CRC tumors by The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) using integrative analysis of genomic and transcriptomic data found that aggressive CRC tumors also exhibited increased MYC-directed transcriptional activation and repression [31]. Our group has also demonstrated that metastases of CRC to the liver and lung exhibit increased MYC-signaling compared with primary CRC tumors. CMS3 tumors are a combination of MSI-H and MSS tumors and are found in 13% of CRCs. CMS3 tumors exhibit strong metabolic dysregulation and associate with KRAS oncogenic mutations [27,32]. Our group found that metastases of CRC in the liver and lung were never classified as CMS3, highlighting subtype exclusivity in metastases of CRC [32]. Finally, CMS4 tumors, found in 23% of all CRCs, exhibit a mesenchymal phenotype with prominent TGF-β activation, stromal invasion and angiogenesis, and is associated with worse relapse-free and overall survival [27,32].

We and others have found that metastases of CRC exhibit molecular and immunological features distinct from primary CRC tumors [32–34]. Whole exome and transcriptome profiling of 500 patients with metastases derived from 25 different primary tumor sites demonstrated the most prevalent somatic alterations observed in metastases include TP53, CDKN2A, PTEN, PIK3CA and RB1, with higher mutation rates observed in metastases compared with primary tumors. Although most coding mutations found in the primary tumor are shared with their derivative metastases, most coding mutations in metastases (>76%) are unique to a specific metastasis [32,35]. At the transcriptional level, metastases can be delineated into two distinct subtypes: epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT)-inflammatory or proliferative. EMT shifts cells toward a mesenchymal state and modifies the adhesion molecules expressed by cells allowing them to adopt to a migratory invasive phenotype [36]. Specifically, within metastases of CRC in the liver and lung, we recapitulated these results, and metastases of the proliferative subtype were found to exhibit high MYC-signaling. We and others have also demonstrated that the innate and adaptive immune signatures observed in metastases, rather than EMT, MYC, or proliferative signaling, best subclassified transcriptomes of CRC metastases and highlighted that metastases of CRC are transcriptionally different than their primary tumor counterparts [32,33].

Immunologic features of metastases of CRC

Although many immunological therapies are targeted toward patients with advanced metastatic disease, our knowledge of the immune contexture of metastases is limited. Below we highlight some key immune cell types and signaling pathways known to promote or inhibit metastasis of CRC. As our understanding of carcinogenesis and immunological features of cancer continues to expand, a picture of the TME of metastases is beginning to emerge that suggests metastases and their TMEs are distinct from primary tumors [33]. In CRC, the immune milieu present at the site of metastasis dictates the clonal evolution patterns of metastatic progression [35]. The lowest risk of progression was observed in tumor subclones with a low mutation burden resulting from neoantigen depletion, the presence of high CD3+ T-cell infiltration, and tumors with significant immunoediting, defined as the rate of observed neoantigens over the expected number of neoantigens. Progressing tumor subclones on the other hand exhibit immune privilege, measured as having a higher than expected rate of immunogenic mutations, despite the presence of tumor infiltrating T lymphocytes (TILs). Immune privileged metastases with low TILs and a lack of immunoediting were the most prone to recur at new anatomical sites and were most likely to give rise to new metastases at future time points. These unedited tumor clones were also the most likely to exhibit loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in HLA allele genes – a commonly employed immune escape mechanism that reduces HLA/MHC presentation diversity and is observed even in MSI-H tumors resistant to immunotherapy [25,37–39].

A more detailed examination of metastases of CRC has demonstrated that synchronous (i.e., the diagnosis of a distant metastasis within 3 months of CRC diagnosis) and metachronous (i.e., occurrence of a distant metastasis 3 months post-surgical resection of the primary tumor or 6 months after the diagnosis of the primary CRC) metastases exhibit immense heterogeneity in their immune infiltration. Smaller metastases have lower T- & B-cell infiltration. The degree of immune infiltration of the least infiltrated metastasis within a patient was the most significant prognostic indicator of patient tumor relapse, overall survival and disease-free survival [34]. B cell analysis in metastases also demonstrated that regions with B cells are associated with longer overall survival than regions absent of B cells [34].

Although anti-tumor immune responses are predominately focused on the role of T cells, new evidence from metastatic melanoma and sarcoma suggests B cells may play a greater role than previously thought in fighting disease metastasis [40]. In metastatic sarcoma, B cells and the presence of B-cell rich tertiary lymphoid structures are associated with survival and response to ICI therapy [41]. In metastatic melanoma, ICI therapy given in the neoadjuvant setting showed enrichment of B cell signatures in ICI responders compared with nonresponders [42]. With regard to CRC, the presence of tertiary lymphoid structures has also been associated with reduced recurrence risk in nonmetastatic, stage II–III CRC [43]. The role of B cells therefore should be examined in more detail in the setting of mCRC.

Overall, these results suggest that the sooner metastases are able to be recognized by systemic adaptive immunity, the higher the chances of an improved prognostic outcome and that this can be examined directly by assessing the degree of immunoediting present within the TME of a metastasis. Methods to improve earlier detection of metastases by the immune system to drive tumor lymphocytic infiltration may therefore be valuable in targeting metastases. This targeting can be achieved in the neoadjuvant setting where it has been demonstrated that neoadjuvant chemotherapy with anti-EGFR increases PD-1 expression and CD8+ T-cell infiltration of metastases at the tumor center and its infiltrative margins, while in the primary tumor, higher densities of FOXP3+ cells marking regulatory T cells (T Regs) were observed. Notably, unlike anti-EGFR therapy, lymphocytic infiltration of metastases was not enhanced through a combination of standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy and anti-VEGF treatment [34]. EGF/EGFR signaling activates transcription factors like MYC through the Ras/Raf signaling cascade and MYC-proliferative signaling appears to be unique to metastases [44,45]. Therefore, it can be postulated that successful lymphocytic infiltration of metastases of solid tumors through neoadjuvant chemotherapy and anti-EGFR therapy is related to the inhibition of strong MYC signaling, which induces proliferation of metastases and promotes the expression of immune checkpoint molecules [46]. Therefore, effective cell death of metastases by targeting metastasis-specific phenotypes may effectively recruit lymphocytes and could be an avenue for converting immune ’cold’ metastases into immune ’hot’ metastases. However, it should be noted that a key limitation of studies in the metastatic setting is the vast heterogeneity in the treatment of patients. Heterogeneity in treating patients with metastatic disease has also evolved dramatically over the last 20 years, and treatment heterogeneity is especially great in patients diagnosed at earlier stages who later go onto develop metastases. Therefore, findings from studies on prognostic outcomes in the metastatic setting should be interpreted with caution and need to be evaluated against the background of changing treatments and diagnoses.

While the role of the microbiome in disease metastasis of CRC has been well established, the influence of the microbiome on metastases of CRC and the TME of distal CRC metastases has been less well characterized. Recent studies have demonstrated the persistence of the Fusobacterium nucleatum bacteria in metastases of CRC [47] as well as primary tumors. Fusobacterium nucleatum is associated with higher disease stage, worse survival [48], lower TILs in CRC tumors [49], and the generation of pro-inflammatory microenvironments [50] conducive to CRC progression. Dysbiosis has also been strongly associated with obesity – a well-known risk factor for CRC. Obesity stimulates NF-κB and obesity-related inflammation can induce mutagenesis through epigenetic changes and reactive oxygen species damage [51]. Obesity can also directly influence the TME by promoting macrophage dysregulation, promoting secretion of angiogenic factors and increasing adipose-derived granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) which compromise T-cell function [51,52]. Studies in molecular pathological epidemiology which can help further dissect the relationships between dysbiosis, obesity and CRC and determine if TME alterations are indeed key for linking dysbiosis and obesity with CRC [53,54] are needed. Studies in molecular pathological epidemiology are also well suited for studying interactions between gut microbiota and the TME when evaluating the role of specific bacterium, such as Fusobacterium nucleatum, in establishing distal disease metastasis [53,54].

A distinct subset of tumor-associated macrophages, known as metastasis-associated macrophages (MAMs), originate from inflammatory monocytes and are recruited to the site of metastasis to promote growth of metastases and tumor dissemination [45,55]. Cancer cells at the metastatic site are trapped in emboli and secrete CCL2 in order to recruit inflammatory monocytes. These monocytes then differentiate into MAMs in the liver and are necessary for liver metastasis of CRC [56]. CCL2/CCR2 signaling is also critical for the recruitment of monocytes and macrophages to the lungs because mouse models deficient in CCR2 recruit fewer monocytes and macrophages to the lungs and thereby develop fewer lung metastases [57]. MAMs also secrete vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) and increase vascular permeability, thereby promoting extravasation of cancer cells and promoting the persistent growth of migrating cancer cells [58]. Another major chemokine involved in the polarization of macrophages is CCL5, which is expressed by infiltrating T cells at the invasive margins of CRC liver metastases. CCL5 exerts a tumor-promoting phenotype by polarizing macrophages to have a pro-tumorigenic phenotype [59].

The other major tumor-promoting immune cell type involved in mCRC is the neutrophil [45,60]. Neutrophils are signaled to migrate to the liver via CXCL1/CXCLR to establish a pro-metastatic niche. Neutrophils promote metastasis by allowing circulating tumor cells to directly adhere to them via Mac-1/ICAM-1 binding [61] and are thought to trap and retain circulating tumor cells at sites of metastasis through the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), generated by the expulsion of neutrophil DNA and associated proteolytic enzymes [62–64]. NETs have been observed in the lung and are associated with lung metastases of CRC. Moreover, blockade of NET formation with DNase I reduces formation of lung and peritoneal metastases in models of CRC [65]. Similarly, the number of CRC metastases in the peritoneal cavity is markedly reduced by inhibiting DNase I or depleting neutrophils [65]. While many aspects of the TME are described in binary terms, such as high versus low infiltration or immune ‘hot’ versus ‘cold’ features, it is important to highlight that most immune cell types work together to establish the phenotype of the TME, which often has mixed pro- and anti-inflammatory immune features. Therefore, additional studies are needed to evaluate the complexity of the TME and its influence on disease metastasis and progression. To that end, molecular pathological epidemiology studies would also be useful for dissecting immune-immune and tumor-immune interactions that jointly influence disease relapse, survival and CRC prognosis [54].

The TME of progressive metastases may also be partially shaped by the distal organ where tumors have metastasized as some host tissue sites, such as the liver and brain, have lower baseline immune infiltration and are resist to an anti-tumor immune response. Particularly with regards to CRC, the immunosuppressive nature of the liver may promote the development of liver metastases and contribute to the formation of aggressive disease [66,67].

The role of the TME at common sites of CRC metastasis – liver, lung & peritoneum

The liver is an immunoprivileged organ [66] with many unique architectural features that make it suitable for the establishment of a pro-tumorigenic immunosuppressive environment. It has a dual blood supply from the hepatic portal vein and the hepatic arteries and it has a lower blood pressure gradient in the sinusoids, which make it suitable for seeding by circulating tumor cells (CTCs) [67,68]. Liver sinusoidal endothelial cell lectin (LSECtin), generated by sinusoidal endothelial cells, inhibits T-cell immune responses and promotes liver colonization by tumor cells [69]. This allows CRC tumors cells in the intrahepatic milieu to accumulate myeloid cells and establish a pro-metastatic niche for CRC through IL6-STAT3-serum amyloid A1 and A2 (SAA) signaling [67,70]. Stellate macrophages in the liver (Kupffer cells) release inflammatory cytokines to promote CRC cell adhesion [71]. Kupffer cells also express receptors for the carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), which upon binding to CEA, can trigger production of cytokines that affect the upregulation of adhesion molecules thereby protecting tumor cells from the cytotoxicity of nitric oxide production (NO) [72]. CEA is a CRC biomarker, absent in normal colon and rectum, which is commonly assessed during routine surveillance for disease progression. Neutrophils in the liver also promote CRC metastasis by co-localizing with cancer cells in liver sinusoids and are associated with increased production of the CXCL1 chemokine, which is necessary for establishing CRC liver metastases [61]. Blockade of the CXCL1/CXCLR signaling axis is known to inhibit formation of CRC liver metastases [73]. In the liver, NK cells play a major role in inhibiting the formation of metastases. Few NKp46+ NK cells are found in liver metastases of CRC compared with normal liver tissue despite high levels of NK cell specific chemokines and cytokines observed in liver metastases. Moreover, the expression of effector molecules such as Granzyme B and IFN-γ is depleted in liver metastases of CRC and strongly correlates with lower T and NK cell infiltration [74]. These findings highlight the success of liver metastases in hindering an effective anti-tumor immune response.

Similar immunosuppressive mechanisms that allow the formation of CRC metastases in liver are also at play in the lung. Alveolar macrophages suppress anti-tumoral T-cell responses and generate pro-inflammatory molecules, such as leukotriene B4, to promote lung metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma [75]. Similarly, fibroblast cells recruit bone-marrow derived hematopoietic progenitor cells expressing VEGFR1 to terminal bronchioles and bronchiolar veins where they can establish the premetastatic niche. These fibroblasts also secrete cathepsin B activated stearoyl-CoA desaturase I to modulate proliferation and colonization of melanoma cells to the lungs [76]. However, not all myeloid cells are tumor-promoting; some myeloid lineages, such as the non-classical patrolling monocytes, attach to the lung to recruit and activate natural killer (NK) cells, and thereby prevent formation of lung metastases by solid tumors [77]. Similarly, NK cell depletion leads to spontaneous metastases without affecting the primary tumor. Mice with CRC and major defects in innate and adaptive lymphoid immunity are at risk of forming lung and liver metastases, which can be prevented through the transfer of NK cells lacking the potent CD96 NK cell inhibitory receptor [78,79]. Another major class of immune cells known to promote lung metastasis, is TRegs, specifically CCR4+ TRegs, which directly kill NK cells to promote the formation of lung metastases [80]. Interestingly, recent work also suggests that EMT is driven in part by inflammation and immune cells in the TME. Therefore, not only does EMT initiate metastasis, but its coupling with inflammation contributes to the inefficiency of the metastatic process by increasing tumor susceptibility to NK cells through E-cadherin and cell adhesion molecule 1 (CADM1) modulation [81].

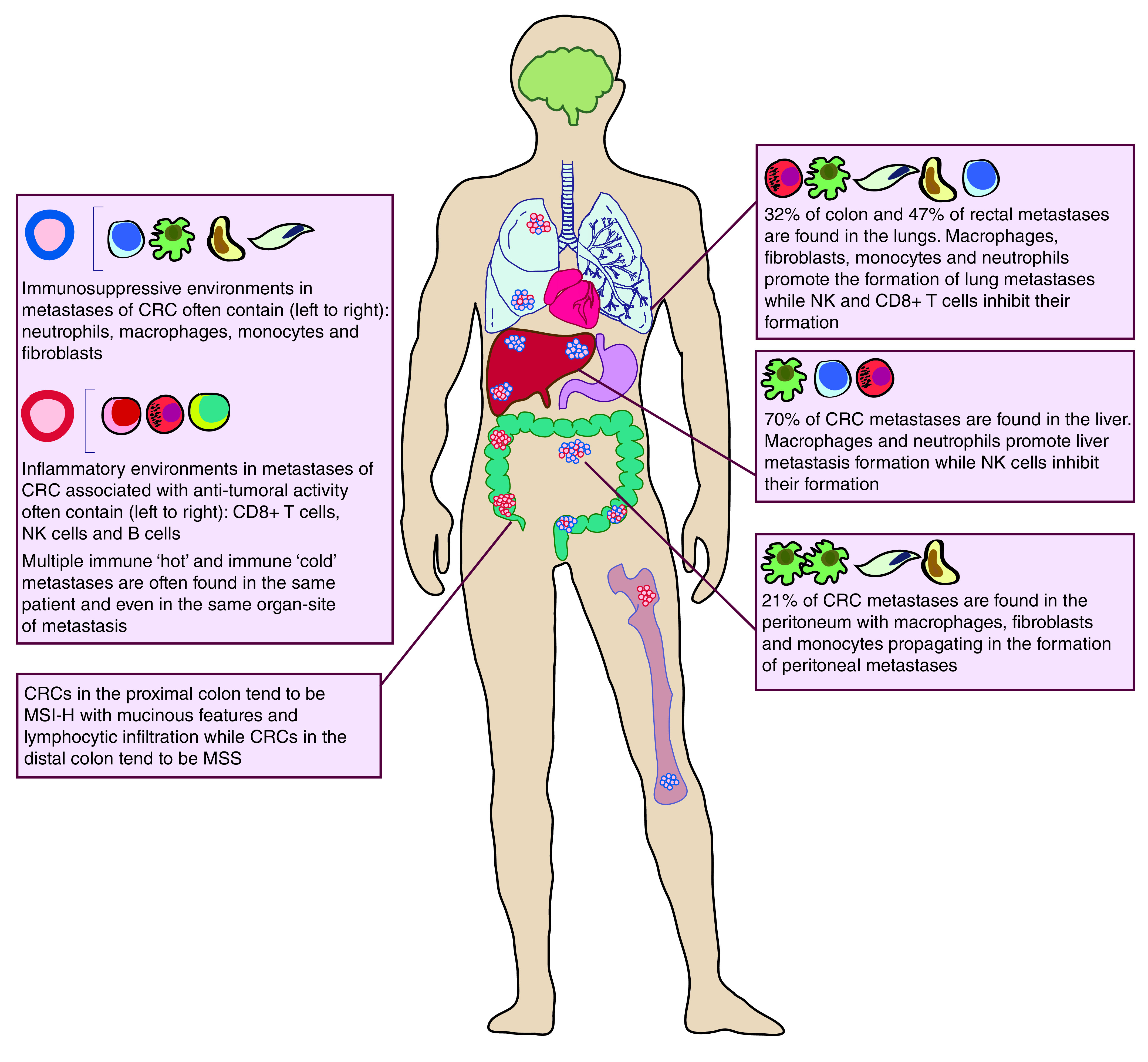

Another common site of metastasis for CRC is the peritoneal cavity surrounding the abdominal organs. Given that peritoneal macrophages make up a large part of the normal peritoneum [82], it is therefore not surprising that peritoneal macrophages and fibroblasts are hijacked by tumor cells and play a strong role in propagating peritoneal metastases. Peritoneal macrophages are driven to an M2 phenotype by either CRC cells directly or through IL6 and IL10 signaling found in malignant ascites fluid. These M2 macrophages can differentiate into CD163+ tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) which promote the dissemination of peritoneal metastases in the presence of gastric cancer cells [83–85]. Collectively, these findings suggest that the TME of the host tissue organs where cancer cells seed can strongly influence the milieu of metastases in those organs. Across all three common sites of CRC metastasis, neutrophils and macrophages appear to have a tumor-promoting role, while NK cells and CD8+ effector T cells have anti-tumor effects (Figure 1).

Figure 1. . Common sites of colorectal cancer metastases and their tumor immune environments.

Colorectal cancer metastasizes most commonly to the liver, lungs, peritoneum and bone. Key features of immune microenvironments at distal sites of metastases are highlighted. Immune ‘hot’ micro-metastases are noted in red, while immune ‘cold’ micro-metastases are denoted in blue.

CRC: Colorectal cancer; MSI-H: Microsatellite instability high; MSS: Microsatellite stable; NK: Natural killer.

Genomic correlates of response to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy

Outside of MSI status, genomic correlates of response to checkpoint blockade therapy have been difficult to pinpoint in MSS CRC tumors. Tumor mutation burden is inconsistently associated with response to ICI therapy. It is associated with enhanced ICI response in cancer types known to have higher overall mutation burden, such as melanoma and lung cancer, compared with other low mutation solid tumor types. However, tumor mutation burden has failed to correlate with response to ICI therapy in other cancer types, such as renal cell carcinoma, which has a characteristically low mutation burden but high immune infiltration [86]. On the other hand, metrics of effector T-cell function appear to consistently associate with improved prognosis even in the setting of metastatic renal cell carcinoma where higher expression of IFN-γ response genes correlates with improved progression-free survival in patients treated with anti-PD-L1 in combination with VEGF inhibitor therapy [87]. Inactivating mutations in the PBRM1 gene which codes for the PBAF SWI-SNF chromatin remodeling complex is associated with higher expression of IFN-γ response genes and correlates with response to ICI therapy in the setting of metastatic renal cell carcinoma after treatment with anti-VEGF therapy [88]. Other SWI-SNF chromatin remodeling complex subunits associated with response to ICI therapy include the ARID1A and SMARCA4 genes in the setting of ovarian cancer [89,90]. Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) HLA alternations have been observed to be enriched in brain metastases of lung cancer [91] and are associated with higher neoantigen burden and upregulation of PDL1 expression on tumor cells [92]. These findings support the idea that LOH of HLA alleles is likely to be an immune escape mechanism resulting from strong TME pressures during tumor evolution. In the setting of colorectal cancer, somatic mutations associated with reduced T-cell tumor infiltration include loss of APC mutations and SMAD4 gene mutations which are both associated with higher tumor and nodal stage, fewer TILs, and worse relapse-free survival [93]. Core driver mutations, such as APC, KRAS, TP53 or SMAD4, are typically shared between primaries and metastases [94]. However additional metastasis driver mutations, such as TCF7L2, AMER1 and PTPRT, have been identified which are enriched in distal metastases compared with early-stage primary CRC [94]. Loss of function mutations in PTPRT increase STAT3 activation in CRC cells, which regulates expression of inflammatory genes [95]. One major limitation in identifying genomic alternations associated with enhanced response of colorectal cancer to ICI therapy is the rarity of finding shared mutations by whole exome sequencing in patients compounded by the small size of clinical trials examining ICI response jointly with somatic or germline genomic alterations in patients.

Why checkpoint blockade therapy fails

Advances in immunotherapy in the last decade have paved the way for ICIs, which targets immune checkpoint molecules, such as CTLA4 and PD-1/PD-L1, with antibodies to disinhibit T-cell activation and stimulate tumor-killing through an adaptive effector immune response against tumor cells [96]. However, while disinhibition of T-cell activation has been employed as an effective strategy to produce long-term durable responses against some tumors, such as melanoma and NSCLC, the majority of patients with solid tumors, including mCRC, fail to respond to ICI therapy [5,96–98] due to intrinsic and extrinsic resistance mechanisms.

One mechanism of resistance is to sustain T-cell exhaustion, in other words, the loss of T-cell effector function due to chronic antigen stimulation, and T-cell inactivation through the upregulation of immune checkpoint molecules, such as LAG-3, especially when a particular ICI, targeting either PD-1, PD-L1 or CTLA4, is given as a monotherapy [99]. A comparison of responders and nonresponders to pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1) found that the latter had terminally exhausted CD8+ T cells expressing cell cycle genes, heat shock proteins and inhibitory T-cell receptors, such as ENTPD1 and KIR2DL4. Exhausted dysfunctional CD8+ T cells observed in nonresponders to pembrolizumab expressed CD39 (ENTPD1) and TIM3 (HAVCR2). Upon inhibition of both of these molecules, reduced tumor growth and improved survival was observed [100]. As such, there is an effort to increase the repertoire of ICIs available for therapy, which can be used in combination to alleviate sustained CD8+ T-cell exhaustion. The therapeutic effect of LAG3 monoclonal antibodies in combination with anti-PD-1 inhibitors is currently being assessed in clinical trials (NCT04085185) in patients with advanced malignant tumors including CRC [101] as promising results were found in melanoma patients when LAG-3 antibodies were combined with anti-PD-1/anti-PD-L1 in individuals who had previously progressed on anti-PD-1/anti-PDL-1 monotherapy [102,103]. LAG-3 is an excellent candidate for the next generation of ICIs, as it is not only known to promote CD8+ T-cell exhaustion but is also expressed on NK and B cells and may therefore have strong secondary effects on boosting systemic anti-tumor immune responses [104].

Another major ICI resistance mechanism is the loss of tumor-specific antigens (neoantigens) through immunoediting in tumors thereby preventing T cells from recognizing tumors and establishing a “cold” tumor phenotype [105]. However, in the setting of mCRC, it appears that low TIL density and immunoprivileged metastases, rather than immune edited metastases, associate with disease progression. Therefore, ICI resistance mechanisms in the setting of mCRC, can be hypothesized to be directed toward T-cell exclusion mechanisms that prevent neoantigen recognition rather than neoantigen depletion per se.

T-cell exclusion from tumors is promoted by tumor innate programs that are present prior to the administration of ICI therapy. Tumor resistance programs are enriched for genes involved in CDK4 and E2F signaling and multiple targets of the MYC proto-oncogene. Resistance programs also repress antigen processing and presentation and response to complement, and interferon signaling [96,106]. TIL exclusion has also been achieved through loss of heterozygosity in the HLA locus, loss of antigen presenting genes such as beta2-microglobulin (B2M), and loss of effective JAK/STAT signaling [37,38].

Loss of sensitivity to interferons and mutations in the interferon signaling axis is another key mechanism employed by tumors to promote immune resistance. Mutations in the genes comprising the interferon signaling pathway, such as IFNGR1, are an effective means to prevent response to ICIs [107] because interferons are the major immunostimulatory and immunomodulatory cytokine defining the Th1 phenotype of T cells responsible for cell-mediated immunity against tumor cells. Similarly, chronic exposure to interferons results in the upregulation of ligands for T-cell inhibitory receptors by tumor cells and this is another key mechanism of resistance to ICI therapy [108]. Last, the development of loss of function variants in the HLA gene in CRC samples with higher TILs across MSI and MSS tumor samples [92] suggests HLA loss of function mutations may be a marker of tumor hypermutability and development of immune escape mechanisms so that the tumors can escape eradication by TILs by preventing them from recognizing tumor cells.

The common feature of all of these ICI resistance mechanisms is that they either directly or indirectly affect the degree of T-cell function and activation in response to tumors, despite T cells receiving an immunostimulatory ‘boost’ from ICI therapy. Given that the TME is not limited to T cells and that there are a variety of immune cell types in the TME of metastases that influence disease progression, it is therefore prudent to ask whether combinations of immunotherapeutic agents that both boost anti-tumor T-cell responses and tackle the immunosuppressive environment of metastases, created in part by the hijacking of innate immune cell by the tumor, would do better to elicit long-term durable response in patients with metastatic disease. Therefore, we focus this review on emerging therapies that either alone or in combination with ICIs are able to treat metastatic disease by altering the TME of metastases and boosting anti-tumor immunity.

CAR- T cell, bi-specific antibodies & adoptive T-cell transfer

In liver metastases, depletion of effector molecules by hepatocytes and macrophages, and the presence of targetable CRC-specific antigens, such as CEA, has been observed. As such, CAR-T-cell therapy may be an effective strategy to combat T-cell exclusion observed in distant metastases. Recent trials of CAR-T cells in the setting of mCRC have targeted CEA. A Phase I dose-escalating trial of CAR-T-cell therapy targeting CEA+ mCRC in ten relapsed and refractory patients with liver and lung CRC metastases [109] has shown promising results. Lympho-depletion in a subset of patients prior to CAR-T-cell infusions was also performed. Most patients (7/10) who previously experienced progressive disease went on to have stable disease and demonstrated a decrease in CEA levels in response CAR-T-cell therapy. Unfortunately, immunosuppressive factors including TRegs, myeloid-derived suppressive cells and checkpoint inhibitors on T cells, increased within the first two weeks of CAR-T therapy [109]. However, this reactive immunosuppression post therapy was attenuated in patients who had received high-dose lymphodepletion [110]. As highlighted earlier, the liver is known to breed a pro-tumorigenic immunosuppressive environment. As such, intrahepatic CAR-T-cell therapy targeting CEA+ liver metastases was given to patients through hepatic artery infusions with and without IL-2 support in a Phase I trial [110], where intra-hepatic infusion of anti-CEA CAR-T cells with and without IL-2 support resulted in a median overall survival of 15 weeks and ranged from 8 to 102 weeks. Anti-CEA CAR-T-cell therapy has also shown to be effective for patients with heavily treated CRC metastases as well as CRC metastases to the lungs [111].

When targetable cancer antigens are not known, adoptive T-cell transfer therapy can also be considered. Adoptive T-cell transfer therapy uses a patient's own tumor infiltrating lymphocytes. T cells with anti-tumoral activity are identified and expanded in vivo and reinfused into the same cancer patient. Adoptive T-cell transfer was recently shown to effectively target KRAS mutant tumor cells in a patient with mCRC. This study elegantly demonstrated the existence of naturally occurring T cells targeting oncogenic mutations. This is particularly exciting given that the specific KRAS mutation targeted by adoptive T-cell therapy in this study has been identified in 45% of pancreatic and 13% of CRC patients [112].

Another approach to combat the immunosuppressive nature of CRC metastases has been the development of bi-specific antibodies which redirect endogenous T cells to tumors by targeting both CD3 and known antigens or immunosuppressive molecules. For CRC, these bispecific T-cell engagers (BiTEs) have been developed to target CEA and CD3 to increase intratumoral T-cell infiltration, activation, and T-cell mediated tumor killing. Monotherapy with CEA-CD3 BiTEs in patients with MSS mCRC has resulted in partial response in 6% of patients and stable disease in 13% of patients [113]. Stable disease was defined by a reduction in tumor burden by 10–30%. Therapy with CEA-CD3 BiTEs is also known to upregulate PD-L1/PD-1 expression. Combination therapy with atezolizumab (anti-PD-L1) has resulted in partial response in 21.5% of patients and stable disease in 36% of patients with advanced CEA+ mCRC [113].

BiTEs have also been developed to target the protein gpA33, which was found to be universally expressed in putative cancer stem cell populations found in both primary CRC and metastases of CRC [114,115]. In preclinical trials, BiTEs targeting gpA33 result in CD8 and CD4 T-cell mediated lysis with increased granzyme and perforin activity and acquisition of a strong memory T-cell phenotype [115]. However, prolonged exposure to gpA33-targeting BiTEs also results in the expression of the PD-1 and LAG-3 checkpoint molecules on T cells, suggesting that therapy with BiTEs may be more effective in combination with ICIs [115]. Human trials with BiTEs for mCRC are currently well underway (NCT03531632), including clinical trials with BiTEs targeting CD3 and guanylate cyclase C (GUCY2C) [116] (NCT04171141) in combination with ICIs (anti-PD-1) and anti-VEGF angiogenesis inhibitors (Table 1).

Table 1. . Ongoing Phase I/II clinical trials evaluating the use of novel immunological agents in combination with or independent of checkpoint blockade inhibitors in colorectal cancer.

| Study name | Agent | Target | Study population | Primary end point | Phase | Recruitment status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCT04085185 | IBI110 +/− sintilimab | LAG-3 PD-1 |

Unresectable or metastatic solid tumors refractory to standard therapy | AEs, SAEs, DLTs | I | Not yet recruiting |

| NCT03531632 | MGD007 MGA012 |

gpA33 × CD3 PD-1 |

Relapsed or refractory mCRC | AEs, SAEs | Ib & II | Active not recruiting |

| NCT04171141 | PF-07062119 +/− anti-PD-1 +/− bevacizumab | GUCY2C PD-1 VEGF |

Advanced or metastatic gastrointestinal tumors | DLTs, AEs, OR | I | Active recruiting |

| NCT03436563 | M7824 | TGFbetaRII × PD-L1 | mCRC or advanced MSI solid tumor | ORR, clearance of circulating tumor DNA | Ib/II | Active recruiting |

| NCT02699515 | M7824 | TGFbetaRII × PD-L1 | Metastatic or locally advanced solid tumors | DLTs, TEAEs, AEs | I | Active not recruiting |

| NCT04119830 | Rintatolimod + pembrolizumab | TLR3 PD-1 |

Refractory mCRC or unresectable CRC | ORR | II | Not yet recruiting |

| NCT03301896 | LHC165 +/− PDR001 | TLR7 PD-1 |

Advanced solid malignancies | DLTs, AEs, SAEs | I | Active recruiting |

|

NCT03865082 ILLUMINATE-206 |

Tilsotolimod Nivolumab Ipilimumab |

TLR9 PD-1 CTLA-4 |

Solid tumors (advanced MSS CRC) | ORR | II | Active recruiting |

| NCT03957096 | SGN-CD47M | CD47 | Unresectable or metastatic solid malignancy | AEs, DLTs | I | Active recruiting |

|

NCT02777710 MEDIPLEX |

Pexidartinib Durvalumab |

PD-L1 CSF-1R |

Metastatic or advanced pancreatic or CRC | DLTs, ORR | I | Active not recruiting |

| NCT04096638 | SB 11285 +/− nivolumab |

STING PD-1 |

Solid tumors (advanced, unresectable, metastatic) | DLTs, MTD, AEs, RP2D | I | Active recruiting |

AE: Adverse event; DLT: Dose-limiting toxicity; mCRC: Metastatic colorectal cancer; MSI: Microsatellite instability; MSS: Microsatellite stable; MTD: Maximum tolerated dose; OR: Objective response; ORR: Objective response rate; RP2D: Recommended Phase II dose; SAE: Serious adverse event; TEAE: Treatment-emergent adverse event.

Immunological target drug combinations: TFG-β inhibitors, TLR agonists & STING agonists

TGF-β plays a key role in helping CRC and its distant metastases evade the immune system [117]. It promotes T-cell exclusion and blocks the acquisition of a Th1 effector phenotype by CD8+ T cells. Multiple studies have demonstrated the role of TGF-β in promoting metastasis through inhibition of antigen presentation by dendritic cells, repressing the production of cytolytic factors, such as granzymes A & B, perforins and IFN-γ and direct promotion of angiogenesis and EMT [118]. Inhibition of TGF-β also results in a potent and enduring cytotoxic T-cell response against CRC tumors with an MSS phenotype and metastases of CRC [118,119]. Therefore, there is increasing interest in successful therapeutic targeting of TGF-β. Clinical trials (NCT03436563) are examining an anti-PDL-1 and an anti-TGF-βR2 (TGF-β receptor 2) fusion protein. This bifunctional checkpoint inhibitor fusion protein known as M7824 has effectively reduced plasma TGF-β1 levels and overall TGF-β signaling and is able to bind to PD-L1 expressed on tumors in mouse models of colon cancer [120]. Moreover, promising preclinical data has demonstrated that the bifunctional checkpoint inhibitor promotes CD8+ T-cell and NK cell activation, decreases tumor burden and increases overall survival [120]. The results from more than 15 Phase I and II clinical trials with this first-in-class bifunctional checkpoint inhibitor are therefore eagerly anticipated including results from a Phase II trial comparing M7824 and pembrolizumab (anti-PD-1) as first-line agents for advanced NSCLC (NCT03631706) and results from a Phase I trial examining M7824 safety and tolerability in patients with metastatic or locally advanced solid tumors for which standard therapy has failed (NCT02699515).

Toll-like Receptors (TLR) are pattern recognition receptors that upon stimulation lead to innate and adaptive immune responses. In particular, TLR signaling can be harnessed to overcome immunosuppressive TMEs. Clinical trials are looking at TLR agonists for TLR3, TLR9 and TLR7 – the antiviral TLRs localized to the endosomal membranes – in combination with ICIs. Detection of double-stranded RNA triggers maturation of dendritic cells and elicits cross-antigen presentation to cytotoxic T lymphocytes via TLR3 [121]. TLR3 RNA agonists have been found to elicit a cytotoxic T-cell anti-tumor response without the production of systemic interferons [122]. Current trials are examining the efficacy of RNA-based TLR3 agonists in combination with anti-PD1 to overcome immune resistance (NCT04119830). TLR7/8 are receptors for single-stranded RNA and illicit a strong immune response upon viral infection [123]. TLR7/8 agonists overcome immunosuppressive TMEs by driving macrophage polarization to an M1 phenotype [124]. When combined with ICIs, TLR7/8 agonists improved responses to ICIs in mouse models and effectively suppressed growth of lung metastases in colon cancer mouse models [125]. An open label Phase I/Ib trial is currently examining the safety and efficacy of TLR7 agonists in combination with anti-PD-1 in patients with advanced malignancies including mCRC (NCT03301896). TLR9 activation acts on macrophage and dendritic cells to increase antigen presentation and downstream activation and proliferation of T cells and can induce a type 1 interferon response [126]. An ongoing Phase I/II trial (NCT03865082) for the treatment of solid tumors recently reported results for 26 patients with refractory metastatic melanoma treated with a TLR9 agonist and anti-CTLA4. They found 38% of patients showed an objective response rate with two patients having a complete response, six patients with a partial response and seven patients with stable disease [126]. Clinical trials in CRC using TLR agonists are summarized in Table 1.

Other mechanisms employed to overcome immunosuppression and promote anti-tumor immunity include targeting the anti-phagocytic signaling molecule, CD47 [127], inhibiting CSF1R [128] which regulates macrophage survival, differentiation and migration and the use of stimulator of interferon genes (STING) agonists [129] to promote adaptive immunity. Solid tumors, including CRC, express three- to five-times more CD47 than corresponding normal tissue. CD47 acts as a negative checkpoint for innate and adaptive immunity by binding to the receptor signal regulatory protein α (SIRPα) expressed on myeloid cells and producing a ‘don't eat me’ anti-phagocytic signal [130]. Phase I trials are currently examining the safety and validity of CD47 inhibition (NCT03957096). CSF1R inhibition in pre-clinical models of CRC have demonstrated CSF1R inhibition depletes tumor associated macrophages while increasing TILs in patients [128,131]. Current Phase I studies (NCT02777710) are evaluating the combination of CSF1R inhibitors and anti-PD-1 in CRC. Early results from the Phase I trial are promising and show clinical benefit at 2 months with 21% of all (MSS and MSI) patients with stable disease [131]. Last, Phase I trials are examining the efficacy and safety of STING agonists in combination with the anti-PD-1 (NCT04096638). STING agonists are thought to stimulate production of interferons and pro-inflammatory cytokines when tumor-derived DNA is sensed by cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) and interacts with STING to enhance adaptive immunity and anti-tumor activity by increasing cross antigen presentation of tumor antigens and promoting CD8+ T-cell mobilization [132,133]. Preclinical data in CRC mouse models have shown a durable immune response to STING-agonist infusions, and have demonstrated that STING agonists can dramatically reduce tumor growth when combined with anti-CTLA4 [129,132]. However, STING signaling is also known to play a role in tumorigenesis and can recruit suppressive immune cells and activate pro-tumor survival genes [134]. Therefore, it is currently unclear how the dual nature of STING will impact the therapeutic efficacy of STING-agonist use. Overall, several new immunological targets are being considered for the treatment of mCRC outside of ICI therapy paving the way for new approaches to address immunosuppression in cancer (Table 1).

Dendritic cell vaccine therapy

The revival of dendritic cell (DC) vaccine therapy should be seriously considered for targeting CRC disease metastasis. DCs capture and present antigens, allowing them to release IL2 and activate CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. DC vaccination therapy involves priming and expanding a patient's DCs by exposing them to specific cancer antigens. These primed DCs are then reintroduced into patients to help activate cytotoxic T cells directed against tumor cells. Moreover, DC activation coordinates the function of T cells, naive B cells, NK cells, and natural killer T (NKT) cells by secreting numerous cytokines including IL10, IL12 and interferons allowing for a systemic anti-tumor response [135]. Having known neoantigens that can be targeted by DCs for immunization is therefore essential when developing DC therapies. CRC cells express numerous tumor-associated antigens such as CEA [136], Wilm's tumor gene 1 (WT1) [137], Mucin 1 (MUC1) [136], and melanoma-associated antigen gene (MAGE) [138] that make CRC an excellent candidate for DC therapy approaches. However, objective response rates for DC therapies have been disappointing and rarely exceed 15% [139]. One reason for this failure is thought to be prominent immunosuppression after DC vaccination. Thus, one approach has been the use of DC vaccine therapy in the adjuvant setting when tumor burden and tumor-induced immune suppression is significantly reduced [140]. T cells targeting tumor-specific antigens were found in 71% of patients with metastatic melanoma who received DC vaccination in the adjuvant setting, compared with 23% of patients without DC vaccination [141]. Moreover, detection of these T cells was associated with an improved overall 2-year survival [141]. The therapeutic effect of adjuvant DC vaccination was also demonstrated for CRC. DC vaccination that is either enhanced with or without CD40L was examined in the adjuvant setting after resection of CRC metastases [142]. CD40L-enhanced DC vaccination induced either a tumor-specific T-cell proliferative response or an IFN-γ response – both of which resulted in a markedly better recurrence-free survival at 5 years in 63% of patients compared with nonresponders [142]. In addition, response to DC therapy was found to be associated with genes enriched in the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling axis suggesting efficacy of DC vaccination in the adjuvant setting may be influenced by somatic mutations in the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway [143]. Newer approaches to DC vaccination therefore includes combining DC vaccines with ICIs particularly in tumor types with low mutation burden, such as MSS tumors, because the best response to DC vaccination has been previously observed in glioblastoma and renal clear cell carcinoma, which have low tumor mutation burdens [105]. Therefore, DC vaccination in combination with ICIs may improve T lymphocyte infiltration in ‘immune cold’ tumors while also keeping the immunosuppressive features of tumors at bay.

Chemotherapy & checkpoint blockade combinations

Chemotherapy and ICI combinations are being tested to determine if immunogenic chemotherapy regiments can sensitize tumors to ICIs. Oxaliplatin and cyclophosphamide therapy have been successfully combined with ICIs (both anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA4). In CRC models, oxaliplatin therapy alone sufficiently sensitized tumors to anti-CTLA4 therapy [144]. Other drug combinations currently being explored in combination with ICIs for the treatment of metastatic and refractory CRC include combining ICIs with the standard 5-fluorouracil (FU) with leucovorin and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) chemotherapy and VEGF blockade using Bevacizumab [145] (NCT01633970, NCT03202758). FOLFOX can stimulate a successful anti-tumoral immune response defined by increased CD3+ lymphocytic and masT-cell tumor infiltration that is associated with tumor regression. Albeit the anti-tumorigenic effects of FOLFOX also result in increased expression of PD-L1 on tumor cells [146,147]. A comprehensive overview of chemotherapy and ICI combinations and their therapeutic efficacy has been discussed elsewhere [5].

Conclusion & future perspective

Advances in immunotherapy are contributing to the decline in metastasis-related deaths in patients with solid tumors. ICI therapy is now recommended as a first-line agent for the treatment of metastatic melanoma and NSCLC without targetable driver mutations, and is indicated for therapy in urothelial carcinoma, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [96,97]. ICI is also now a key therapeutic agent for renal cell carcinoma in the adjuvant setting. Similarly, efforts to target known cancer antigens in other solid tumors with shared antigens using CAR-T-cell therapies are also currently under exploration. Vaccine-based therapeutics, which have made gains in the treatment of renal and prostate cancer, continue to be improved for use in solid tumors [139,140]. The ongoing interest in developing and refining immune-based therapies for the treatment of metastatic disease across many cancer types in both the adult and pediatric setting speaks to the immense therapeutic potential of immunotherapy.

Given the immense heterogeneity found in metastases – both in their unique mutational landscapes and their TMEs – combination therapy targeting multiple aspects of the TME are needed. This is particularly true given the presence of multiple immune ‘hot’ and immune ‘cold’ metastases present within a given individual. Within the field of CRC and particularly with regards to liver metastases of CRC, targeting immunosuppressive host environments is necessary for eliminating metastatic disease. Moreover, a better understanding of commonly employed immune escape mechanisms and how these escape mechanisms evolve under pressure from different immunological therapies is also warranted in order to determine which drug combinations can effectively rein in metastatic disease. Last, targeting EMT-driven extravasation and associated inflammation in metastases is highly desirable, as EMT-associated inflammation appears to be a key feature of metastases and EMT is a known driver of cancer stem cells. Therefore, routine assessment of the TME to determine the immune ‘hot’ or ‘cold’ status of metastases as they present is crucial. Current immunotherapies working toward targeting EMT-driven metastases and their associated inflammation include TGF-β and anti-PDL1 fusion proteins. However, a stronger concerted effort is required to both better understand metastases and their unique immunological features, and subsequently, develop metastasis-targeted therapies.

Executive summary.

Distant metastasis of colorectal cancer (CRC) is found in 20% of patients at the time of diagnosis, and metastases of CRC are commonly found in the liver, lung and peritoneum. Metastases of CRC are difficult to treat even when in the setting of microsatellite instability. However, the use of immunological agents to combat disease metastasis is increasingly gaining approval.

Distant metastases are molecularly different from their primary tumor counterparts in both transcriptomic and genomic features as well as their microenvironments. With regards to CRC metastases, neutrophils, macrophages, monocytes and fibroblasts exhibit immunosuppressive and tumor-promoting effects, while natural killer and CD8+ T cells have anti-tumoral effects in the liver, lung and peritoneum.

Given the resistance of metastatic lesions to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy, driven by mechanisms such as sustained T-cell exhaustion, T-cell exclusion and loss of sensitivity to interferons, immunological therapies that are complimentary with checkpoint inhibitors and or directly tackle the immunosuppressive environments of metastases are required.

Emerging immunological therapies in the setting of metastatic CRC include CAR-T-cell therapy targeting the carcinoembryonic antigen, bi-specific T-cell engagers, TGF-β inhibitors, Toll-like Receptor agonists and dendritic cell therapy in the adjuvant setting.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Riihimaki M, Hemminki A, Sundquist J, Hemminki K. Patterns of metastasis in colon and rectal cancer. Sci. Rep. 6, 29765 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Geest LGM, Lam-Boer J, Koopman M, Verhoef C, Elferink MAG, de Wilt JHW. Nationwide trends in incidence, treatment and survival of colorectal cancer patients with synchronous metastases. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 32(5), 457–465 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. Cancer J. Clin. 70(1), 7–30 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Venugopal A, Stoffel EM. Colorectal cancer in young adults. Curr. Treat. Options Gastroenterol. 17(1), 89–98 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ganesh K, Stadler ZK, Cercek Aet al. Immunotherapy in colorectal cancer: rationale, challenges and potential. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16(6), 361–375 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Overman MJ, Ernstoff MS, Morse MA. Where we stand with immunotherapy in colorectal cancer: deficient mismatch repair, proficient mismatch repair, and toxicity management. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. B. 38(38), 239–247 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao P, Li L, Jiang X, Li Q. Mismatch repair deficiency/microsatellite instability-high as a predictor for anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy efficacy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 12(1), 54 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koopman M, Kortman GAM, Mekenkamp Let al. Deficient mismatch repair system in patients with sporadic advanced colorectal cancer. Br. J. Cancer 100(2), 266–273 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halvorsen TB, Seim E. Association between invasiveness, inflammatory reaction, desmoplasia and survival in colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Pathol. 42(2), 162–166 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gatalica Z, Vranic S, Xiu J, Swensen J, Reddy S. High microsatellite instability (MSI-H) colorectal carcinoma: a brief review of predictive biomarkers in the era of personalized medicine. Fam. Cancer 15(3), 405–412 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim H, Jen J, Vogelstein B, Hamilton SR. Clinical and pathological characteristics of sporadic colorectal carcinomas with DNA replication errors in microsatellite sequences. Am. J. Pathol. 145(1), 148–156 (1994). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hewish M, Lord CJ, Martin SA, Cunningham D, Ashworth A. Mismatch repair deficient colorectal cancer in the era of personalized treatment. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 7(4), 197–208 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Llosa NJ, Cruise M, Tam Aet al. The vigorous immune microenvironment of microsatellite instable colon cancer is balanced by multiple counter-inhibitory checkpoints. Cancer Discov. 5(1), 43–51 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prizment AE, Vierkant RA, Smyrk TCet al. Cytotoxic t cells and granzyme b associated with improved colorectal cancer survival in a prospective cohort of older women. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 26(4), 622–631 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Overman MJ, McDermott R, Leach JLet al. Nivolumab in patients with metastatic DNA mismatch repair-deficient or microsatellite instability-high colorectal cancer (CheckMate 142): an open-label, multicentre, Phase II study. Lancet Oncol. 18(9), 1182–1191 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Germano G, Lamba S, Rospo Get al. Inactivation of DNA repair triggers neoantigen generation and impairs tumour growth. Nature 552(7683), 1–5 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KNet al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science 357(6349), 409–413 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Eriksson Amonkar, Al-Jassar Get al. Mismatch repair/microsatellite instability testing practices among US physicians treating patients with advanced/metastatic colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Med. 8(4), 558 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Venderbosch S, Nagtegaal ID, Maughan TSet al. Mismatch repair status and BRAF mutation status in metastatic colorectal cancer patients: a pooled analysis of the CAIRO, CAIRO2, COIN, and FOCUS studies. Clin. Cancer Res. 20(20), 5322–5330 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujiyoshi K, Yamamoto G, Takahashi Aet al. High concordance rate of KRAS/BRAF mutations and MSI-H between primary colorectal cancer and corresponding metastases. Oncol. Rep. 37(2), 785–792 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pagès F, Mlecnik B, Marliot Fet al. International validation of the consensus Immunoscore for the classification of colon cancer: a prognostic and accuracy study. Lancet 391(10135), 2128–2139 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mlecnik B, Bindea G, Angell HKet al. Integrative analyses of colorectal cancer show immunoscore is a stronger predictor of patient survival than microsatellite instability. Immunity 44(3), 698–711 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rozek LS, Schmit SL, Greenson JKet al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, Crohn's-like lymphoid reaction, and survival from colorectal cancer. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 108(8), djw027 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang Het al. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 372(26), 2509–2520 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gurjao C, Liu D, Hofree Met al. Intrinsic resistance to immune checkpoint blockade in a mismatch repair–deficient colorectal cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 7(8), 1230–1236 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.LI E, Hu Y, Han Wet al. The mutational landscape of MSI-H and MSS colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 37(Suppl. 15), e15122–e15122 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guinney J, Dienstmann R, Wang Xet al. The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Nat. Med. 21(11), 1350–1356 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim CG, Ahn JB, Jung Met al. Effects of microsatellite instability on recurrence patterns and outcomes in colorectal cancers. Br. J. Cancer 115(1), 25–33 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fujiyoshi K, Yamamoto G, Takenoya Tet al. Metastatic pattern of stage IV colorectal cancer with high-frequency microsatellite instability as a prognostic factor. Anticancer Res. 37(1), 239–247 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim GP, Colangelo LH, Wieand HSet al. Prognostic and predictive roles of high-degree microsatellite instability in colon cancer: A National Cancer Institute-national surgical adjuvant breast and bowel project collaborative study. J. Clin. Oncol. 25(7), 767–772 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muzny DM, Bainbridge MN, Chang Ket al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature 487(7407), 330–337 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamal Y, Schmit SL, Hoehn HJ, Amos CI, Frost HR. Transcriptomic differences between primary colorectal adenocarcinomas and distant metastases reveal metastatic colorectal cancer subtypes. Cancer Res. 79(16), 4227–4241 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robinson DR, Wu Y-M, Lonigro RJet al. Integrative clinical genomics of metastatic cancer. Nature 548(7667), 297–303 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van den Eynde M, Mlecnik B, Bindea Get al. The link between the multiverse of immune microenvironments in metastases and the survival of colorectal cancer patients. Cancer Cell 34(6), 1012–1026.e3 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Angelova M, Mlecnik B, Vasaturo Aet al. Evolution of metastases in space and time under immune selection. Cell 175(3), 751–765.e16 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nieto MA, Huang RYYJ, Jackson RAA, Thiery JPP. EMT: 2016. Cell 166(1), 21–45 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sade-Feldman M, Jiao YJ, Chen JHet al. Resistance to checkpoint blockade therapy through inactivation of antigen presentation. Nat. Commun. 8(1), 1136 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zaretsky JM, Garcia-Diaz A, Shin DSet al. Mutations associated with acquired resistance to PD-1 blockade in melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 375(9), 819–829 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marty R, Kaabinejadian S, Rossell Det al. MHC-I genotype restricts the oncogenic mutational landscape. Cell 171(6), 1272–1283.e15 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Helmink BA, Reddy SM, Gao Jet al. B cells and tertiary lymphoid structures promote immunotherapy response. Nature 577(7791), 549–555 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petitprez F, de Reyniès A, Keung EZet al. B cells are associated with survival and immunotherapy response in sarcoma. Nature 577(7791), 556–560 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cabrita R, Lauss M, Sanna Aet al. Tertiary lymphoid structures improve immunotherapy and survival in melanoma. Nature 577(7791), 561–565 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Posch F, Silina K, Leibl Set al. Maturation of tertiary lymphoid structures and recurrence of stage II and III colorectal cancer. Oncoimmunology 7(2), e1378844 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oda K, Matsuoka Y, Funahashi A, Kitano H. A comprehensive pathway map of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling. Mol. Syst. Biol. 1, 2005.0010 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kitamura T, Qian BZ, Pollard JW. Immune cell promotion of metastasis. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 15(2), 73–86 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Casey SC, Tong L, Li Yet al. MYC regulates the antitumor immune response through CD47 and PD-L1. Science 352(6282), 227–231 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bullman S, Pedamallu CS, Sicinska Eet al. Analysis of Fusobacterium persistence and antibiotic response in colorectal cancer. Science 358(6369), 1443–1448 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mima K, Nishihara R, Qian ZRet al. Fusobacterium nucleatum in colorectal carcinoma tissue and patient prognosis. Gut 65(12), 1973–1980 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mima K, Sukawa Y, Nishihara Ret al. Fusobacterium nucleatum and T cells in colorectal carcinoma. JAMA Oncol. 1(5), 653–661 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kostic AD, Chun E, Robertson Let al. Fusobacterium nucleatum potentiates intestinal tumorigenesis and modulates the tumor-immune microenvironment. Cell Host Microbe. 14(2), 207–215 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Edwards RA, Witherspoon M, Wang Ket al. Epigenetic repression of DNA mismatch repair by inflammation and hypoxia in inflammatory bowel disease-associated colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 69(16), 6423–6429 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang H, Youm Y-H, Vandanmagsar Bet al. Obesity increases the production of proinflammatory mediators from adipose tissue T cells and compromises TCR repertoire diversity: implications for systemic inflammation and insulin resistance. J. Immunol. 185(3), 1836–1845 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ogino S, Nowak JA, Hamada T, Milner DA, Nishihara R. Insights into pathogenic interactions among environment, host, and tumor at the crossroads of molecular pathology and epidemiology. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 14(1), 83–103 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ogino S, Chan AT, Fuchs CS, Giovannucci E. Molecular pathological epidemiology of colorectal neoplasia: an emerging transdisciplinary and interdisciplinary field. Gut (3), 397–411 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qian B, Deng Y, Im JHet al. A distinct macrophage population mediates metastatic breast cancer cell extravasation, establishment and growth. PLoS ONE 4(8), e6562 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhao L, Lim SY, Gordon-Weeks ANet al. Recruitment of a myeloid cell subset (CD11b/Gr1mid) via CCL2/CCR2 promotes the development of colorectal cancer liver metastasis. Hepatology 57(2), 829–839 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Headley MB, Bins A, Nip Aet al. Visualization of immediate immune responses to pioneer metastatic cells in the lung. Nature 531(7595), 513–517 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Qian BZ, Li J, Zhang Het al. CCL2 recruits inflammatory monocytes to facilitate breast-tumour metastasis. Nature 475(7355), 222–225 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Halama N, Zoernig I, Berthel Aet al. Tumoral immune cell exploitation in colorectal cancer metastases can be targeted effectively by anti-CCR5 therapy in cancer patients. Cancer Cell. 29(4), 587–601 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Smith HA, Kang Y. The metastasis-promoting roles of tumor-associated immune cells. J. Mol. Med. 91(4), 411–429 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Spicer JD, McDonald B, Cools-Lartigue JJet al. Neutrophils promote liver metastasis via Mac-1-mediated interactions with circulating tumor cells. Cancer Res. 72(16), 3919–3927 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rayes RF, Mouhanna JG, Nicolau Iet al. Primary tumors induce neutrophil extracellular traps with targetable metastasis-promoting effects. JCI Insight 4(16), e128008 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Richardson JJR, Hendrickse C, Gao-Smith F, Thickett DR. Neutrophil extracellular trap production in patients with colorectal cancer in vitro Int. J. Inflam. 2017(July), 4915062 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Albrengues J, Shields MA, Ng Det al. Neutrophil extracellular traps produced during inflammation awaken dormant cancer cells in mice. Science 361(6409), eaao4227 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Park J, Wysocki RW, Amoozgar Zet al. Cancer cells induce metastasis-supporting neutrophil extracellular DNA traps. Sci. Transl. Med. 8(361), (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lang KS, Georgiev P, Recher Met al. Immunoprivileged status of the liver is controlled by Toll-like receptor 3 signaling. J. Clin. Invest. 116(9), 2456–2463 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gao Y, Bado I, Wang H, Zhang W, Rosen JM, Zhang XHF. Metastasis organotropism: redefining the congenial soil. Dev. Cell. 49(3), 375–391 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.MacPhee PJ, Schmidt EE, Groom AC. Intermittence of blood flow in liver sinusoids, studied by high-resolution in vivo microscopy. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 269(5), 32–35 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tang L, Yang J, Liu Wet al. Liver sinusoidal endothelial cell lectin, LSECtin, negatively regulates hepatic T-cell immune response. Gastroenterology 137(4), 498–1508.e5(2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee JW, Stone ML, Porrett PMet al. Hepatocytes direct the formation of a pro-metastatic niche in the liver. Nature 567(7747), 249–252 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Auguste P, Fallavollita L, Wang N, Burnier J, Bikfalvi A, Brodt P. The host inflammatory response promotes liver metastasis by increasing tumor cell arrest and extravasation. Am. J. Pathol. 170(5), 1781–1792 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thomas P, Forse RA, Bajenova O. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and its receptor hnRNP M are mediators of metastasis and the inflammatory response in the liver. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 28(8), 923–932 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yamamoto M, Kikuchi H, Ohta Met al. TSU68 prevents liver metastasis of colon cancer xenografts by modulating the premetastatic niche. Cancer Res. 68(23), 9754–9762 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Halama N, Braun M, Kahlert Cet al. Natural killer cells are scarce in colorectal carcinoma tissue despite high levels of chemokines and cytokines. Clin. Cancer Res. 17(4), 678–689 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nosaka T, Baba T, Tanabe Yet al. Alveolar macrophages drive hepatocellular carcinoma lung metastasis by generating leukotriene B 4. J. Immunol. 200(5), ji1700544 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kaplan RN, Riba RD, Zacharoulis Set al. VEGFR1-positive haematopoietic bone marrow progenitors initiate the pre-metastatic niche. Nature 438(7069), 820–827 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hanna RN, Cekic C, Sag Det al. Patrolling monocytes control tumor metastasis to the lung. Science 350(6263), 985–990 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Martinet L, Ferrari De Andrade L, Guillerey Cet al. DNAM-1 expression marks an alternative program of NK cell maturation. Cell Rep. 11(1), 85–97 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Malaisé M, Rovira J, Renner Pet al. KLRG1 + NK Cells Protect T-bet-deficient mice from pulmonary metastatic colorectal carcinoma. J. Immunol. 192(4), 1954–1961 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Olkhanud PB, Baatar D, Bodogai Met al. Breast cancer lung metastasis requires expression of chemokine receptor CCR4 and regulatory T cells. Cancer Res. 69(14), 5996–6004 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chockley PJ, Chen J, Chen G, Beer DG, Standiford TJ, Keshamouni VG. Epithelial–mesenchymal transition leads to NK cell-mediated metastasis-specific immunosurveillance in lung cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 128(4), 1384–1396 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Narasimhan V, Pham T, Wilson Ket al. Abstract 2345: colorectal peritoneal metastases: exploring the immune landscape and the potential of immunotherapy using organoid models. : Cancer Research American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) (2019).2345–2345 [Google Scholar]

- 83.Coccolini F, Gheza F, Lotti Met al. Peritoneal carcinomatosis. World J. Gastroenterol. 19(41), 6979–6994 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sakamoto S, Kagawa S, Kuwada Ket al. Intraperitoneal cancer-immune microenvironment promotes peritoneal dissemination of gastric cancer. Oncoimmunology 8(12), e1671760 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mikuła-Pietrasik J, Paweł Uruski, Tykarski A, Książek K. The peritoneal “soil” for a cancerous “seed”: a comprehensive review of the pathogenesis of intraperitoneal cancer metastases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 75(3), 509–525 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Keenan TE, Burke KP, Van Allen EM. Genomic correlates of response to immune checkpoint blockade. Nat. Med. 25(3), 389–402 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.McDermott DF, Huseni MA, Atkins MBet al. Clinical activity and molecular correlates of response to atezolizumab alone or in combination with bevacizumab versus sunitinib in renal cell carcinoma. Nat. Med. 24(6), 749–757 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Miao D, Margolis CA, Gao Wet al. Genomic correlates of response to immune checkpoint therapies in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Science 359(6377), 801–806 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Shen J, Ju Z, Zhao Wet al. ARID1A deficiency promotes mutability and potentiates therapeutic antitumor immunity unleashed by immune checkpoint blockade. Nat. Med. 24(5), 556–562 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jelinic P, Ricca J, Van Oudenhove Eet al. Immune-active microenvironment in small cell carcinoma of the ovary, hypercalcemic type: rationale for immune checkpoint blockade. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 110(7), 787–790 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.McGranahan N, Rosenthal R, Hiley CTet al. Allele-specific HLA loss and immune escape in lung cancer evolution. Cell 171(6), 1259–1271.e11 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Grasso CS, Giannakis M, Wells DKet al. Genetic mechanisms of immune evasion in colorectal cancer. Cancer Discov. 8(6), 730–749 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wasserman I, Lee LH, Ogino Set al. Smad4 loss in colorectal cancer patients correlates with recurrence, loss of immune infiltrate, and chemoresistance. Clin. Cancer Res. 25(6), 1948–1956 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]