Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the efficacy of monthly or quarterly fremanezumab in patients with chronic migraine or episodic migraine and documented inadequate response to 2, 3, or 4 classes of prior migraine preventive medications.

Methods

This is an exploratory analysis of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3b trial for patients with chronic migraine or episodic migraine and inadequate response to 2 to 4 prior migraine preventive medication classes randomized (1:1:1) to fremanezumab (quarterly or monthly) or placebo. In this exploratory analysis, changes from baseline in the monthly average number of migraine days during 12 weeks of double-blind treatment and adverse events were evaluated for predefined subgroups of patients by number of prior preventive medication classes with inadequate response.

Results

Overall, 414, 265, and 153 patients had inadequate response to 2, 3, and 4 preventive medication classes, respectively. Changes from baseline in monthly average migraine days during 12 weeks were significantly greater with fremanezumab compared with placebo for patients with documented inadequate response to 2 classes (least-squares mean difference vs placebo [95% confidence interval]: quarterly, –2.9 [–3.83, –1.98]; monthly, –3.7 [–4.63, –2.75]), 3 classes (quarterly, –3.3 [–4.65, –1.95]; monthly, –3.0 [–4.25, –1.66]), and 4 classes (quarterly, –5.3 [–7.38, –3.22]; monthly, –5.4 [–7.35, –3.48]) of migraine preventive medications (all p < 0.001). No significant treatment-by-subgroup interactions were observed for any outcome (p interaction > 0.20 for all). Adverse events were comparable for placebo and fremanezumab.

Conclusion

Significant improvements in efficacy were observed with fremanezumab compared with placebo, even in patients who had previously experienced inadequate response to 4 different classes of migraine preventive medications.

ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03308968.

Keywords: Chronic migraine, episodic migraine, treatment failure, CGRP

Introduction

Treatment guidelines recommend offering migraine preventive treatment to individuals with as few as 3 monthly headache days and severe disability (1). However, until the recent approvals of monoclonal antibodies targeting the calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) pathway, recommended preventive medications were not specifically designed or developed for migraine and were limited by slow onset of action, inadequate efficacy, poor adherence, and suboptimal safety and tolerability (2). Treatment discontinuations are common with oral migraine preventive medications (3), potentially resulting in inadequate migraine treatment, acute medication overuse, chronification, and higher healthcare costs (4,5). The burden of migraine is generally higher for patients who have failed prior preventive treatments, with negative effects on patients’ work and personal lives (6).

Fremanezumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody (IgG2Δa) that selectively targets CGRP (7). Results from the FOCUS trial demonstrated the efficacy and tolerability of fremanezumab treatment in patients with episodic migraine (EM) or chronic migraine (CM) and documented inadequate response to 2 to 4 prior migraine preventive medication classes (7). Understanding the influence of inadequate response to prior migraine preventive treatments on fremanezumab treatment outcomes could inform clinical decision making and guide optimal usage of fremanezumab in patients with migraine. Here we report results from analyses of the efficacy and tolerability of fremanezumab in predefined subgroups of patients with migraine from the FOCUS study by number of classes of prior migraine preventive medications to which they had inadequate response (2, 3, or 4 classes). Based on the clinical benefit with fremanezumab observed in a prespecified subgroup analysis of patients in the FOCUS study who had previously not responded to topiramate and up to 3 other classes of migraine preventive medications (7), we hypothesized that quarterly and monthly dosing of fremanezumab would be consistently effective in patients with inadequate response to 2, 3, or 4 classes of prior migraine preventive medications.

Methods

This was an exploratory analysis of predefined subgroups in the international, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, phase 3b FOCUS trial (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03308968) in patients with CM or EM who had documented inadequate response to 2 to 4 prior classes of migraine preventive medications (4). The study design, eligibility criteria, methods, and statistical analysis methods for that trial have been reported in detail previously (7) and are summarized briefly here.

Patients

Patients were recruited for the FOCUS study from November 2017 through July 2018. Eligible patients included adults (18–70 years of age) with a diagnosis of migraine (onset ≤50 years of age) according to International Classification of Headache Disorders 3 beta version (ICHD-3 beta) criteria (8) and a history of migraine for ≥12 months prior to screening. Eligible patients also had documented inadequate response within the past 10 years to 2 to 4 of the following classes of prior migraine preventive medications: beta blockers, anticonvulsants, tricyclic antidepressants, calcium channel blockers, onabotulinumtoxinA, and valproic acid. An inadequate response was generally documented in the patient’s medical record and defined by no clinically meaningful improvement (per the treating physician’s judgement) after 3 months of stable-dosed treatment, discontinuation due to poor tolerability, or contraindication or unsuitability of treatment for the patient (7). At the time of screening, patients could not use migraine preventive medications; patients continuing treatment with migraine preventive medications were excluded from the study.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

The FOCUS study was approved by an independent ethics committee or institutional review board at each study site, and each patient provided written informed consent.

Study design

The FOCUS study included a screening visit; a 28-day run-in period; a 12-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled treatment period; and a 12-week, open-label treatment period. For the 12-week, double-blind treatment period, patients were randomized (1:1:1) to monthly fremanezumab (Month 1: CM, 675 mg; EM, 225 mg; Months 2 and 3: 225 mg), quarterly fremanezumab (Month 1: 675 mg; Months 2 and 3: placebo), or matched monthly placebo. Efficacy was evaluated using information entered daily by patients in an electronic headache diary throughout the treatment period (7).

Outcomes assessed in subgroups by number of prior migraine preventive medication classes with inadequate response

For these subgroup analyses of patients by the number of classes of prior migraine preventive medications to which they had inadequate response (2, 3, or 4 classes), the mean change from baseline in the monthly average number of migraine days was evaluated during the 12-week, double-blind period after the first dose of study drug (primary endpoint for the study).

For these subgroup analyses, the proportion of patients achieving ≥50% reduction in the monthly average number of migraine days, mean change from baseline in the average number of headache days of at least moderate severity, and mean change from baseline in average days of any acute headache medication use were also evaluated during the 12-week period after the first dose of fremanezumab. For the 4-week period after the first dose of fremanezumab, the mean change from baseline in monthly average migraine days, proportion of patients achieving ≥50% reduction in the monthly average number of migraine days, and mean change from baseline in the monthly average number of headache days of at least moderate severity were also assessed in these subgroups.

Additional outcomes assessed in these subgroups included mean change from baseline in disability scores based on the 6-item Headache Impact Test (HIT-6) and Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) and mean change from baseline in patient satisfaction, as measured by the Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC) during the 4 weeks after the third dose of fremanezumab. A PGIC responder was defined as a patient who reported a rating of 5 to 7 (moderately better, better, or a great deal better) on the PGIC. Adverse events (AEs), serious AEs (SAEs), and AEs leading to discontinuation were evaluated in these subgroups by number of prior migraine preventive medications classes with inadequate response.

Statistical analyses

A sample size of 705 evaluable patients (235 per treatment group) completing the study was needed for the primary analysis for 90% power to show a difference of 1.8 in migraine days (assuming a common standard deviation of 6 days) at an alpha level of 0.05. Assuming a 12% discontinuation rate for the double-blind period, 268 patients per treatment group were planned for randomization. For the FOCUS study, efficacy analyses were performed on the modified intention-to-treat analysis set, which included all randomized patients who received ≥1 dose of study drug and had ≥10 days of post-baseline efficacy assessments for the primary endpoint. In these predefined subgroups of patients by the number of classes of prior migraine preventive medications to which they had inadequate response (2, 3, or 4 classes), the analysis of the change in the monthly average number of migraine days was part of the original statistical analysis plan; the analyses of all other endpoints within these subgroups were conducted post hoc.

Baseline data for the monthly average number of migraine days were collected during the 28-day period before the first dose of study drug. For the monthly average number of migraine days during the 12 weeks after the first dose of study drug, a mean number of migraine days was calculated for each of the 3 months, and the mean of these values was then calculated. For the change from baseline in the monthly average number of migraine days during the 12-week treatment period (primary endpoint of the study), analyses were performed using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) method that included treatment, sex, region, special group of treatment failure, migraine classification, and treatment-by-migraine classification interaction as fixed effects and baseline number of migraine days and years since onset of migraine as covariates. Statistical methods for all secondary and exploratory endpoints are summarized in Supplemental material 1. All statistical tests were 2-tailed at the 0.05 level of significance. All data listings, summaries, and statistical analyses were generated using SAS® software (version 9.4 or later of SAS Systems for Windows, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

The safety analysis set of the FOCUS study included all randomized patients who received ≥1 dose of study drug. AEs were coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) version 18.1.

Data availability

For the analyses described in this manuscript, anonymized data will be shared upon request from any qualified investigator by the author investigators or Teva Branded Pharmaceutical Products R&D, Inc.

Results

Of the 837 patients in the modified intention-to-treat analysis set, 832 patients were included in these subgroup analyses. Of these patients, 414 patients (50%) had inadequate response to 2 classes of migraine preventive medications, 265 (32%) to 3 classes, and 153 (18%) to 4 classes. A total of 5 patients who had inadequate response to either 1 or >4 medication classes were excluded from these subgroup analyses. Patient baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics.

|

2 classes |

3 classes |

4 classes |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo(n = 141) | Quarterly fremanezumab(n = 140) | Monthly fremanezumab(n = 133) | Placebo(n = 82) | Quarterly fremanezumab(n = 85) | Monthly fremanezumab(n = 98) | Placebo(n = 54) | Quarterly fremanezumab(n = 49) | Monthly fremanezumab(n = 50) | |

| Monthly migraine days, mean (SD) | |||||||||

| Total population | 13.6 (6.17) | 13.3 (5.66) | 12.8 (5.09) | 14.2 (6.05) | 14.4 (5.85) | 15.2 (5.82) | 16.8 (5.63) | 16.0 (4.61) | 15.3 (5.71) |

| Chronic migraine | 17.6 (5.6) | 17.1 (5.3) | 16.2 (4.2) | 17.8 (5.0) | 16.8 (5.1) | 17.4 (5.5) | 18.7 (4.6) | 17.6 (3.6) | 17.6 (5.3) |

| Episodic migraine | 9.0 (2.5) | 9.5 (2.6) | 9.0 (2.8) | 9.0 (2.8) | 8.7 (2.9) | 10.3 (2.6) | 9.8 (2.6) | 9.9 (2.5) | 10.1 (2.4) |

| Monthly headache days of at least moderate severity, mean (SD) | 12.2 (5.8) | 11.5 (5.9) | 11.4 (5.3) | 12.4 (5.7) | 12.6 (6.1) | 13.7 (6.1) | 15.3 (5.9) | 14.7 (4.5) | 14.2 (6.0) |

| Monthly days of any acute headache medication use, mean (SD) | 12.2 (6.0) | 12.4 (6.3) | 11.5 (5.8) | 11.4 (6.0) | 12.6 (6.7) | 12.8 (6.0) | 14.0 (7.0) | 14.3 (5.1) | 12.5 (6.2) |

| Disability | |||||||||

| HIT-6 score, mean (SD) | 63.8 (5.6) | 64.2 (4.2) | 63.7 (4.2) | 64.0 (4.1) | 64.0 (4.7) | 63.9 (4.7) | 65.1 (4.5) | 64.8 (3.8) | 65.0 (4.3) |

| MIDAS score, mean (SD) | 57.0 (55.6) | 55.7 (46.7) | 51.2 (42.2) | 61.6 (58.1) | 62.2 (50.0) | 66.3 (48.2) | 72.7 (58.9) | 74.6 (50.2) | 85.7 (69.0) |

SD, standard deviation; HIT-6, 6-item Headache Impact Test; MIDAS, Migraine Disability Assessment.

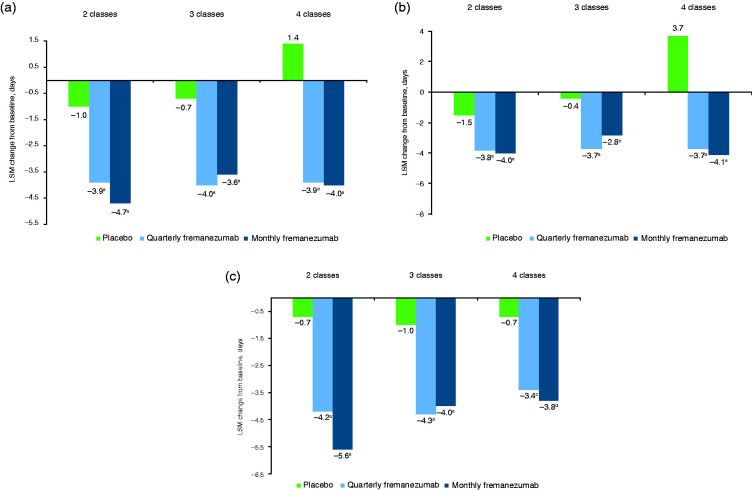

Monthly migraine days

For the primary endpoint, the reduction from baseline in the monthly average number of migraine days during the 12-week treatment period was significantly greater with both quarterly and monthly fremanezumab compared with placebo in patients who had prior inadequate response to 2, 3, and 4 migraine preventive medication classes (all p < 0.001; Figure 1a). Among patients with inadequate response to 2 medication classes, the least-squares mean (LSM) change from baseline (standard error [SE]) was −1.0 (0.43) with placebo, –3.9 (0.44) with quarterly fremanezumab (LSM difference [LSMD] vs placebo, –2.9 [95% confidence interval (CI): –3.83, –1.98]), and –4.7 (0.44) with monthly fremanezumab (–3.7 [–4.63, –2.75]). For patients with inadequate response to 3 medication classes, the LSM (SE) change from baseline was –0.7 (0.56) with placebo, –4.0 (0.58) with quarterly fremanezumab (LSMD vs placebo, –3.3 [95% CI: –4.65, –1.95]), and –3.6 (0.58) with monthly fremanezumab (–3.0 [–4.25, –1.66]). For patients with inadequate response to 4 medication classes, the LSM (SE) change from baseline was 1.4 (0.97) with placebo, –3.9 (0.97) with quarterly fremanezumab (LSMD vs placebo, –5.3 [95% CI: –7.38, –3.22]), and –4.0 (0.85) with monthly fremanezumab (–5.4 [–7.35, –3.48]).

Figure 1.

Change from baseline in monthly average migraine days over 12 weeks of treatment.

(a) All patients (b) EM patients (c) CM patients.

LSM, least-squares mean; EM, episodic migraine; CM, chronic migraine.

ap < 0.001 versus placebo. bp = 0.011 versus placebo. cp = 0.007 versus placebo. dp = 0.003 versus placebo.

Regardless of migraine classification (CM or EM), significantly greater reductions from baseline in the monthly average number of migraine days were observed with both fremanezumab dosing regimens compared with placebo over 12 weeks of treatment in patients with inadequate response to 2, 3, or 4 migraine preventive medication classes (Figures 1b and 1c). In patients with CM, the reduction from baseline in the monthly average number of migraine days during the 12 weeks after the first dose of study drug was significantly greater with fremanezumab compared with placebo in patients with prior inadequate response to 2 medication classes (LSMD vs placebo: quarterly fremanezumab, –3.5 [95% CI: –5.00, –1.93]; monthly fremanezumab, –4.9 [–6.45, –3.34]; both p < 0.001), 3 medication classes (quarterly fremanezumab, –3.3 [–5.02, –1.62]; monthly fremanezumab, –3.1 [–4.74, –1.45]; both p < 0.001), and 4 medication classes (quarterly fremanezumab, –2.8 [–4.78, –0.76]; monthly fremanezumab, –3.2 [–5.24, –1.10]; both p ≤ 0.007; Figure 1b). In patients with EM, the reduction from baseline in monthly average migraine days during the 12 weeks after the first dose of study drug was significantly greater with fremanezumab versus placebo in patients who had prior inadequate response to 2 medication classes (LSMD vs placebo [95% CI]: quarterly fremanezumab, –2.3 [–3.29, –1.37]; monthly fremanezumab, –2.5 [–3.50, –1.53]; both p < 0.001), 3 medication classes (quarterly fremanezumab, –3.4 [–5.26, –1.44]; monthly fremanezumab, –2.4 [–4.28, –0.57]; both p ≤ 0.011), and 4 medication classes (quarterly fremanezumab, –7.4 [–10.36, –4.37]; monthly fremanezumab, –7.8 [–10.41, –5.11]; both p < 0.001; Figure 1c).

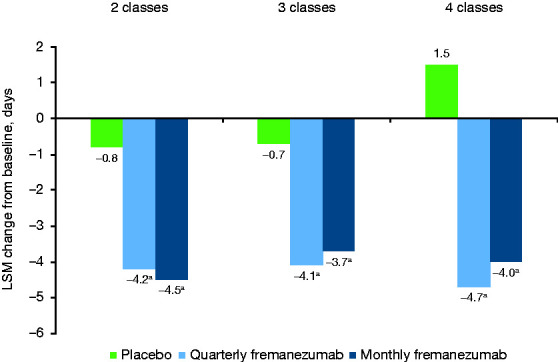

Reductions from baseline in the monthly average number of migraine days at 4 weeks after the first dose of study drug were also significantly greater with fremanezumab versus placebo in patients who had prior inadequate response to 2, 3, and 4 migraine preventive medication classes (all p < 0.001, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Change from baseline in the monthly average number of migraine days over the first 4 weeks of treatment.

LSM, least-squares mean.

ap < 0.0001 versus placebo.

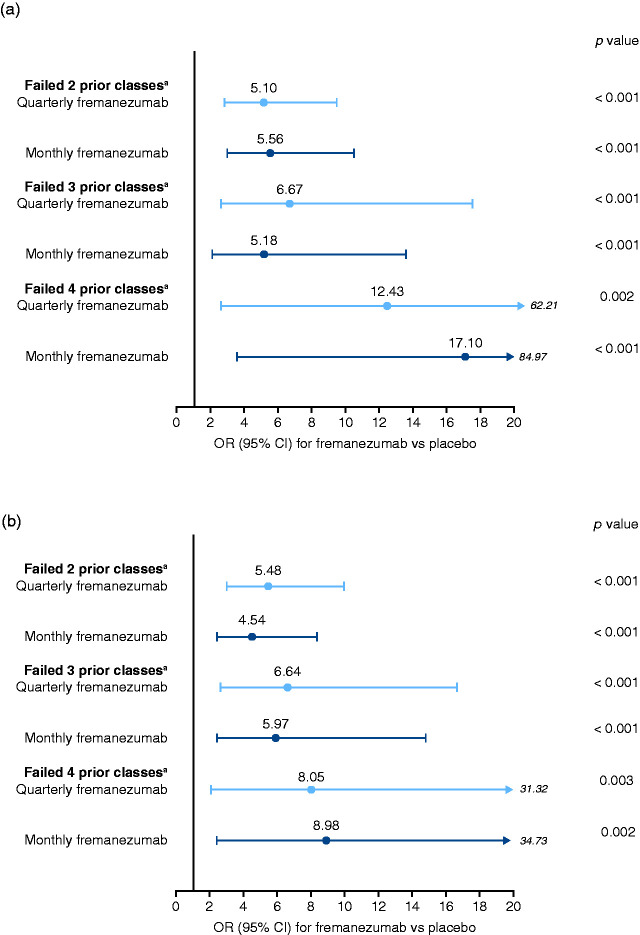

Responder rates

The proportion of patients who achieved ≥50% reduction in the monthly average number of migraine days during the 12 weeks of double-blind treatment was significantly higher with fremanezumab compared with placebo in patients who had prior inadequate response to 2, 3, and 4 migraine preventive medication classes (all p ≤ 0.002; Figure 3a). With quarterly fremanezumab, monthly fremanezumab, and placebo, respectively, ≥50% reduction in the monthly average number of migraine days was achieved in 39%, 41%, and 11% of patients with inadequate response to 2 medication classes; 32%, 28%, and 7% of patients with inadequate response to 3 medication classes; and 27%, 32%, and 4% of patients with inadequate response to 4 medication classes.

Figure 3.

ORs (fremanezumab vs placebo) for achieving ≥50% reduction in monthly migraine days.

(a) Over 12 weeks of treatment (b) At 4 weeks of treatment.

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

aClasses of migraine preventive medications.

The proportion of patients who achieved ≥50% reduction in the monthly average number of migraine days during the 4 weeks after the first dose of study drug was also significantly higher with fremanezumab compared with placebo in patients who had prior inadequate response to 2, 3, and 4 migraine preventive medication classes (all p ≤ 0.003; Figure 3b). With quarterly fremanezumab, monthly fremanezumab, and placebo, respectively, ≥50% reduction in monthly average migraine days was achieved in 44%, 39%, and 13% of patients with inadequate response to 2 medication classes; 34%, 33%, and 9% of patients with inadequate response to 3 medication classes; and 29%, 32%, and 6% of patients with inadequate response to 4 medication classes.

Significantly higher proportions of patients with CM achieved ≥50% reduction in the monthly average number of migraine days during the 12-week treatment period with fremanezumab compared with placebo among patients with inadequate response to 2 prior migraine preventive medication classes (quarterly fremanezumab: 33% [odds ratio (OR), 4.27 (95% CI: 1.75, 10.42); p = 0.001] and monthly fremanezumab: 36% [5.20 (2.13, 12.69); p < 0.001] vs placebo: 11%), 3 medication classes (23% [4.52 (1.20, 17.09); p = 0.026] and 26% [5.04 (1.37, 18.50); p = 0.015], respectively, vs 6%), or 4 medication classes (21% [5.21 (1.02, 26.71); p=0.048] and 20% [6.51 (1.22, 34.80); p = 0.028], respectively, vs 5%). Similarly, in patients with EM, higher proportions of patients achieved ≥50% reduction in monthly average migraine days during the 12-week treatment period with fremanezumab compared with placebo among patients with inadequate response to 2 medication classes (quarterly fremanezumab: 46% [OR, 6.05 (95% CI: 2.51, 14.56); p < 0.001] and monthly fremanezumab: 45% [6.01 (2.46, 14.69); p < 0.001] vs placebo: 12%), 3 medication classes (52% [11.69 (2.71, 50.51); p = 0.001] and 30% [4.02 (0.95, 17.09); p = 0.059] vs 9%), or 4 medication classes (50% and 60%, respectively, vs 0%; sample size was too small for logistic regression model).

Headache days of at least moderate severity

In subgroups of patients with prior inadequate response to 2, 3, and 4 migraine preventive medication classes, reductions from baseline in the monthly average number of headache days of at least moderate severity during the 12 weeks of double-blind treatment were significantly greater with fremanezumab compared with placebo (all p < 0.001; Table 2). Reductions from baseline in the monthly average number of headache days of at least moderate severity at 4 weeks after the first dose of study drug were also significantly greater with monthly fremanezumab compared with placebo in patients who had prior inadequate response to 2, 3, and 4 migraine preventive medication classes (all p < 0.001; Table 2).

Table 2.

Change from baseline in monthly headache days of at least moderate severity and days of any acute headache medication use over 4 and 12 weeks.

|

2 classes |

3 classes |

4 classes |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo(n = 141) | Quarterly fremanezumab(n = 140) | Monthly fremanezumab(n = 133) | Placebo(n = 82) | Quarterly fremanezumab(n = 85) | Monthly fremanezumab(n = 98) | Placebo(n = 54) | Quarterly fremanezumab(n = 49) | Monthly fremanezumab(n = 50) | |

| 12 weeks | |||||||||

| Monthly headache days of at least moderate severity | |||||||||

| LSM change from baseline (SE) | –1.2 (0.42) | −3.9 (0.42) | –4.8 (0.42) | –0.3 (0.57) | –3.9 (0.59) | –3.5 (0.59) | 0.6 (1.02) | –4.7 (1.01) | –4.9 (0.88) |

| LSMD versus placebo (95% CI) | –2.7 (–3.64, –1.86) | –3.6 (–4.47, –2.65) | –3.6 (–4.96, –2.21) | –3.2 (–4.56, –1.93) | –5.2 (–7.42, –3.07) | –5.4 (–7.47, –3.42) | |||

| p value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Monthly days of any acute headache medication use | |||||||||

| LSM change from baseline (SE) | –1.2 (0.43) | –4.0 (0.44) | –4.3 (0.44) | –0.4 (0.49) | –3.7 (0.51) | –3.5 (0.51) | 1.2 (0.94) | –3.6 (0.93) | –4.0 (0.82) |

| LSMD versus placebo (95% CI) | –2.9 (–3.79, –1.94) | –3.2 (–4.12, –2.23) | –3.2 (–4.44, –2.06) | –3.0 (–4.18, –1.89) | –4.8 (–6.80, –2.81) | –5.2 (–7.05, –3.33) | |||

| p value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| 4 weeks | |||||||||

| Monthly headache days of at least moderate severity | |||||||||

| LSM change from baseline (SE) | –1.0 (0.43) | –4.1 (0.43) | –4.7 (0.43) | –0.2 (0.56) | –4.1 (0.58) | –4.0 (0.58) | 0.7 (1.03) | –5.3 (1.03) | –5.2 (0.90) |

| LSMD versus placebo (95% CI) | –3.2 (–4.09, –2.21) | –3.8 (–4.71, –2.80) | –4.0 (–5.34, –2.60) | –3.8 (–5.11, –2.49) | –6.0 (–8.30, –3.78) | –5.9 (–8.02, –3.81) | |||

| p value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| Monthly days of any acute headache medication use | |||||||||

| LSM change from baseline (SE) | –0.9 (0.43) | –4.2 (0.44) | –4.4 (0.44) | –0.5 (0.49) | –4.0 (0.51) | –3.9 (0.51) | 1.1 (0.91) | –4.3 (0.91) | –4.2 (0.80) |

| LSMD versus placebo (95% CI) | –3.2 (–4.18, –2.27) | –3.5 (–4.42, –2.48) | –3.5 (–4.66, –2.24) | –3.3 (–4.51, –2.19) | –5.4 (–7.41, –3.41) | –5.3 (–7.19, –3.45) | |||

| p value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

LSM, least-squares mean; SE, standard error; LSMD, least-squares mean difference; CI, confidence interval.

Acute headache medication use

The reduction in the monthly average number of days of any acute headache medication use was significantly higher with fremanezumab compared with placebo during the 12 weeks after the first dose of study drug in patients who had prior inadequate response to 2, 3, and 4 migraine preventive medication classes (all p < 0.001; Table 2). The reduction in the monthly average number of days of any acute headache medication use was also significantly higher with fremanezumab compared with placebo at 4 weeks after the first dose of study drug in patients who had prior inadequate response to 2, 3, and 4 migraine preventive medication classes (all p < 0.001; Table 2).

Disability (HIT-6 and MIDAS) and Patient satisfaction (PGIC)

Regardless of the number of prior migraine preventive medication classes with inadequate response, the reduction from baseline in the HIT-6 score during the 4 weeks after the third dose of study drug was significantly greater with fremanezumab compared with placebo (all p ≤ 0.014; Table 3). The reduction from baseline in the MIDAS score during the 4 weeks after the third dose of study drug was also significantly greater with monthly fremanezumab compared with placebo in patients who had prior inadequate response to 2, 3, or 4 migraine preventive medication classes (all p ≤ 0.010) and with quarterly fremanezumab compared with placebo in patients who had prior inadequate response to 4 migraine preventive medication classes (Table 3).

Table 3.

Change from baseline to 4 weeks after the third dose of study drug in disability outcomes.

|

2 classes |

3 classes |

4 classes |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo(n = 141) | Quarterly fremanezumab(n = 140) | Monthly fremanezumab(n = 133) | Placebo(n = 82) | Quarterly fremanezumab(n = 85) | Monthly fremanezumab(n = 98) | Placebo(n = 54) | Quarterly fremanezumab(n = 49) | Monthly fremanezumab(n = 50) | |

| HIT-6 score | |||||||||

| LSM change from baseline (SE) | –2.7 (0.77) | –5.3 (0.78) | –6.4 (0.78) | –2.6 (0.90) | –5.4 (0.96) | –5.8 (0.94) | 0.6 (1.19) | –5.0 (1.18) | –6.2 (1.04) |

| LSMD versus placebo (95% CI) | –2.5 (–4.21, –0.88) | –3.6 (–5.32, –1.93) | –2.8 (–4.95, –0.57) | –3.2 (–5.28, –1.11) | –5.6 (–8.16, –3.03) | –6.8 (–9.25, –4.43) | |||

| p value | 0.003 | <0.001 | 0.014 | 0.003 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||

| MIDAS score | |||||||||

| LSM change from baseline (SE) | –6.1 (4.10) | –14.7 (4.15) | –21.5 (4.11) | –9.1 (5.34) | –18.9 (5.69) | –25.3 (5.56) | 6.7 (10.59) | –25.0 (10.43) | –23.2 (9.12) |

| LSMD versus placebo (95% CI) | –8.7 (–17.47, 0.15) | –15.5 (–24.47, –6.46) | –9.8 (–22.68, 3.08) | –16.2 (–28.51, –3.90) | –31.7 (–54.07, –9.37) | –29.9 (–51.12, –8.70) | |||

| p value | 0.054 | <0.001 | 0.14 | 0.010 | 0.006 | 0.006 | |||

HIT-6, 6-item Headache Impact Test; LSM, least-squares mean; SE, standard error; LSMD, least-squares mean difference; CI, confidence interval; MIDAS, Migraine Disability Assessment.

The proportion of responders on the PGIC scale was significantly higher with both quarterly and monthly fremanezumab compared with placebo in patients with prior inadequate response to 2, 3, or 4 classes of migraine preventive medications (p < 0.001; Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Proportion of PGIC responders.

PGIC, Patient Global Impression of Change.

PGIC responder was defined as a patient who reported a rating of 5 to 7 (moderately better, better, or a great deal better) on the PGIC.

ap < 0.001 versus placebo.

Tolerability

Incidences of AEs, AEs leading to discontinuation, and SAEs were similar with both quarterly and monthly fremanezumab and placebo in patients with prior inadequate response to 2, 3, and 4 classes of migraine preventive medications (Table 4). The most common AEs across subgroups included injection-site erythema (range, 4%–10%) and injection-site induration (range, 2%–10%). The proportion of patients discontinuing the study due to AEs was low (range, <1%–3%).

Table 4.

AEs during double-blind treatment (occurring in ≥2% of patients in any treatment groupa).

|

2 classes |

3 classes |

4 classes |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AEs, n (%) | Placebo(n = 141) | Quarterly fremanezumab(n = 140) | Monthly fremanezumab(n = 134) | Placebo(n = 81) | Quarterly fremanezumab(n = 85) | Monthly fremanezumab(n = 99) | Placebo(n = 54) | Quarterly fremanezumab(n = 49) | Monthly fremanezumab(n = 50) |

| ≥1 AE | 61 (43%) | 67 (48%) | 58 (43%) | 39 (48%) | 51 (60%) | 47 (47%) | 34 (63%) | 31 (63%) | 23 (46%) |

| ≥1 SAE | 4 (3%) | 1 (<1%) | 2 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (2%) | 0 | 1 (2%) | 0 |

| AEs leading to discontinuation | 3 (2%) | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 0 | 3 (3%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AEs | |||||||||

| Injection-site erythema | 8 (6%) | 9 (6%) | 6 (4%) | 5 (6%) | 5 (6%) | 5 (5%) | 2 (4%) | 5 (10%) | 5 (10%) |

| Injection-site induration | 5 (4%) | 4 (3%) | 7 (5%) | 3 (4%) | 3 (4%) | 2 (2%) | 4 (7%) | 5 (10%) | 4 (8%) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) | 7 (5%) | 2 (2%) | 3 (4%) | 2 (2%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nasopharyngitis | 6 (4%) | 4 (3%) | 3 (2%) | 4 (5%) | 5 (6%) | 3 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 4 (8%) | 1 (2%) |

| Influenza | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) | 4 (3%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) |

| Fatigue | 0 | 5 (4%) | 4 (3%) | 2 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 3 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 2 (4%) |

| Injection-site pain | 4 (3%) | 5 (4%) | 3 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 3 (3%) | 2 (4%) | 4 (8%) | 3 (6%) |

| Injection-site paresthesia | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) | 2 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) |

| Injection-site pruritis | 2 (1%) | 0 | 2 (1%) | 0 | 2 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) |

| Injection-site bruising | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 1 (<1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 | 4 (4%) | 0 | 2 (4%) | 0 |

| Injection-site rash | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 0 | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) |

| Injection-site warmth | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (3%) | 0 | 1 (2%) | 0 |

| Injection-site discoloration | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (4%) | 0 |

| Gastroenteritis | 3 (2%) | 0 | 1 (<1%) | 2 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) |

| Cystitis | 3 (2%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (4%) | 0 | 0 |

| Urinary tract infection | 2 (1%) | 3 (2%) | 2 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (6%) | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| Asthenia | 2 (1%) | 0 | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) |

| Chest discomfort | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vertigo | 4 (3%) | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Arthralgia | 3 (2%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 0 | 1 (2%) | 0 |

| Headache | 2 (1%) | 0 | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 2 (2%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Paresthesia | 4 (3%) | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sciatica | 3 (2%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2%) | 0 | 0 |

| Insomnia | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) | 4 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 0 | 3 (6%) | 2 (4%) |

| Palpitations | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 0 | 2 (1%) | 0 | 2 (2%) | 4 (5%) | 2 (2%) | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) | 0 |

| Nausea | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) | 2 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 3 (6%) | 1 (2%) | 0 |

| Abdominal pain | 2 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 3 (4%) | 2 (2%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2%) | 0 |

| Back pain | 3 (2%) | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 2 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 0 | 2 (4%) | 0 |

| Neck pain | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 0 | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) |

| Pain in extremity | 2 (1%) | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Dizziness | 1 (<1%) | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 0 | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) |

| Anxiety | 0 | 1 (<1%) | 2 (1%) | 0 | 2 (2%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Constipation | 1 (<1%) | 3 (2%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (4%) | 1 (2%) |

| Vomiting | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (2%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hematuria | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 0 | 0 |

| Pyrexia | 2 (2%) | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 2 (2%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| Sinusitis | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 2 (2%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (2%) | 0 | 1 (2%) |

| Abdominal pain upper | 0 | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 | 2 (4%) | 0 |

| Hypertension | 0 | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 0 | 1 (2%) | 0 | 0 |

| Influenza-like illness | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (2%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 0 |

| Gastritis | 0 | 1 (<1%) | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (4%) | 0 | 0 |

| Migraine | 3 (2%) | 1 (<1%) | 0 | 1 (1%) | 0 | 2 (2%) | 5 (9%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) |

| Weight increased | 0 | 1 (<1%) | 2 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2%) | 2 (4%) | 0 |

| Rash | 2 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (6%) |

| Hematoma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (4%) | 0 |

| Blood glucose increased | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

AE, adverse event; SAE, serious adverse event.

aAdditional AEs reported by ≥2% (n ≤ 1 per treatment group) of patients in the 4 classes subgroup: anemia, neutropenia, increased tendency to bruise, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, ear pain, allergic conjunctivitis, ocular hyperanemia, breath odor, gingival pain, irritable bowel, abdominal discomfort, eructation, gastroesophageal reflux disease, esophageal ulcer, injection-site discomfort, injection-site hematoma, injection-site hemorrhage, injection-site swelling, injection-site urticarial, peripheral edema, pyrexia, thirst, allergy to arthropod sting, bacterial vaginosis, herpes zoster, viral gastroenteritis, oral herpes, pharyngitis, tracheitis, head injury, heat stroke, arthropod sting, epicondylitis, bordetella test positive, international normalized ratio increased, food intolerance, decreased appetite, limb discomfort, muscle spasms, myalgia, rotator cuff syndrome, muscular weakness, musculoskeletal pain, postural dizziness, somnolence, nervousness, sleep disorder, affect lability, affective disorder, abnormal urine odor, ovarian cyst, menopausal symptoms, cough, oropharyngeal pain, epistaxis, atopic dermatitis, dry skin, ecchymosis, eczema, erythema, pruritic rash, hyperhidrosis, peripheral venous disease, hypotension.

No significant treatment-by-subgroup interactions were observed for any outcome, as shown in the table in Supplemental material 2 (p interaction > 0.20 for all).

Discussion

In these preplanned subgroup analyses, fremanezumab offered significant efficacy over placebo in both CM and EM patients regardless of the number of migraine preventive medication classes with inadequate response prior to this study. Reductions in migraine days and clinically meaningful response rates were achieved as early as 4 weeks after the first dose of study drug. Approximately 30% to 40% of patients who had a documented inadequate response to 2, 3 or 4 migraine preventive treatment classes achieved ≥50% reduction in monthly migraine days with 4 and 12 weeks of treatment. A greater effect size was observed with increasing number of prior treatment failures and was generally demonstrated across all endpoints, with the most notable increase in effect size for patients with inadequate response to 4 classes of migraine preventive medications.

Along with the clinically meaningful reductions in migraine days, both fremanezumab dosing regimens were shown to reduce migraine- and headache-related disability versus placebo in patients who had documented inadequate response to 2, 3, or 4 migraine preventive medication classes. Regardless of the number of prior migraine preventive medication classes with inadequate response, the majority of patients reported improvements with fremanezumab treatment on the PGIC in this study.

Many of the currently available medications used for migraine prevention were not intended or designed for the treatment of migraine and have limited or moderate efficacy and poor tolerability (1,2). Few options exist for patients who do not respond to these preventive therapies. As shown in a retrospective US claims analysis, 86% of patients discontinued initial preventive medication by 1 year, and in patients who switched migraine preventive medications, this number increased to 90% by the third medication (3). However, with better clinical outcomes for patients taking migraine preventive medications, persistence may improve.

Limited data are available on the efficacy and tolerability of migraine preventive treatments by number of prior migraine preventive treatments to which patients have had inadequate response, in particular in patients who have experienced inadequate response to multiple prior preventive treatment classes. Previous subgroup analyses of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies of erenumab in CM (9) and EM (10) showed consistent efficacy for erenumab based on reductions in monthly migraine days, responder rates, and days of acute medication use in patients with prior failure of ≥1 and ≥2 migraine preventive medication categories. However, both studies excluded patients with no therapeutic response to ≥3 prior migraine preventive medications (9,10). The current study demonstrated consistent efficacy and tolerability for fremanezumab, even in potentially more difficult-to-treat patients with inadequate response to 3 or even 4 prior migraine preventive medications.

There are concerns in the literature that, with an increasing number of prior preventive treatment failures, patients with migraine may not respond to monotherapy (11). The results of this study suggest that, even for patients with inadequate response to 4 prior migraine preventive medication classes, fremanezumab as monotherapy is still effective. Furthermore, the patients in this population had additional challenges, including severe disability due to migraine (MIDAS) (12) and severe headache impact on daily functioning (HIT-6) (13). This severe disability, along with the inadequate response to multiple prior migraine preventive medications, highlights the disease severity in this population.

In the current study, placebo responses were low and decreased with increasing number of classes of prior preventive medications with inadequate response. In other studies that evaluated monoclonal antibodies that target the CGRP pathway in CM, mean reductions from baseline in monthly migraine days ranged from –2.7 to –4.2 days for patients receiving placebo, whereas the placebo response for the CM population in this study was –0.7 to –1.0 days for a similar endpoint (14,15). This trend toward lower placebo response in patients with prior inadequate response to preventive treatment was also observed in the subgroup analyses of patients with ≥1 and ≥2 prior preventive treatment category failures in the erenumab studies in CM and EM. The low placebo response in this study, even in patients with CM, further supports the selection of this population of patients with difficult-to-treat migraine. In the current study, fremanezumab reduced monthly migraine days by 3 to 5 days in all patients and by 3 to 4 days in with patients with CM compared with placebo across 2, 3, or 4 classes of prior treatment failures.

The results reported here may be subject to certain limitations. For this analysis, the number of patients included in each subgroup differed, with a smaller number of patients in the subgroup with inadequate response to 4 prior migraine preventive medications. This likely contributed to high point estimates and wide CIs seen in the responder analyses and some other endpoints. However, results were generally similar for patients treated with fremanezumab across all subgroups, suggesting a consistent effect of fremanezumab regardless of prior treatment experience. Additionally, while the subgroups were defined a priori and the analysis of the change in migraine days in each subgroup was part of the original statistical analysis plan, the analyses of the other endpoints within these subgroups were conducted post hoc. As the results in each subgroup for all endpoints were similar to those in the overall population and other subgroups and all assessments were performed a priori, the impact of this limitation is likely small.

Quarterly and monthly fremanezumab were well tolerated, and the results of these subgroup analyses indicate that fremanezumab is consistently effective as a preventive treatment in patients with documented inadequate response to 2, 3, and 4 classes of migraine preventive medications. These results may be relevant for the clinical management of patients with migraine who have a history of inadequate response to multiple prior classes of migraine preventive medications.

Clinical Implications

There are few treatment options available for patients who do not respond to standard migraine preventive medications

The results of these subgroup analyses showed the efficacy of fremanezumab by number of prior migraine preventive treatments in patients who experienced inadequate response to multiple prior preventive treatment classes

The effect size for fremanezumab generally increased with number of prior treatment failures, which may be relevant to the clinical management of patients with migraine and a history of inadequate response to multiple prior classes of migraine preventive medications

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-cep-10.1177_03331024211008401 for Fremanezumab for the Preventive Treatment of Migraine: Subgroup Analysis by Number of Prior Preventive Treatments with Inadequate Response by Ladislav Pazdera, Joshua M Cohen, Xiaoping Ning, Verena Ramirez Campos, Ronghua Yang and Patricia Pozo-Rosich in Cephalalgia

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-cep-10.1177_03331024211008401 for Fremanezumab for the Preventive Treatment of Migraine: Subgroup Analysis by Number of Prior Preventive Treatments with Inadequate Response by Ladislav Pazdera, Joshua M Cohen, Xiaoping Ning, Verena Ramirez Campos, Ronghua Yang and Patricia Pozo-Rosich in Cephalalgia

Acknowledgments

Editorial assistance was provided by Alyssa Nguyen, PharmD, of MedErgy, which was in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP3) guidelines and funded by Teva Pharmaceuticals.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: LP declares no conflict of interest. JMC, XN, and VRC are employees of Teva Pharmaceuticals. RY is a former employee of Teva Pharmaceuticals. PPR has received honoraria as a consultant and speaker for Allergan, Almirall, Biohaven, Chiesi, Eli Lilly, Medscape, Neurodiem, Novartis, and Teva Pharmaceuticals. Her research group has received research grants from AGAUR, Allergan, la Caixa Foundation, FP7, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Migraine Research Foundation, MICINN, and PERIS; and has received funding in the last 5 years for clinical trials from Alder, electroCore, Eli Lilly, Novartis, and Teva Pharmaceuticals. She does not own stocks from any pharmaceutical company.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study and these analyses were funded by Teva Pharmaceuticals.

ORCID iD: Ladislav Pazdera https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0053-7003

References

- 1.American Headache Society. The American Headache Society position statement on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache 2019; 59: 1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reuter U.A review of monoclonal antibody therapies and other preventative treatments in migraine. Headache 2018; 58: 48–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hepp Z, Dodick DW, Varon SF, et al. Persistence and switching patterns of oral migraine prophylactic medications among patients with chronic migraine: a retrospective claims analysis. Cephalalgia 2017; 37: 470–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bigal ME, Lipton RB.Overuse of acute migraine medications and migraine chronification. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2009; 13: 301–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Messali A, Sanderson JC, Blumenfeld AM, et al. Direct and indirect costs of chronic and episodic migraine in the United States: a web-based survey. Headache 2016; 56: 306–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martelletti P, Schwedt TJ, Lanteri-Minet M, et al. My Migraine Voice survey: a global study of disease burden among individuals with migraine for whom preventive treatments have failed. J Headache Pain 2018; 19: 115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferrari MD, Diener HC, Ning X, et al. Fremanezumab versus placebo for migraine prevention in patients with documented failure to up to four migraine preventive medication classes (FOCUS): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3b trial. Lancet 2019; 394: 1030–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018; 38: 1–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ashina M, Tepper S, Brandes JL, et al. Efficacy and safety of erenumab (AMG334) in chronic migraine patients with prior preventive treatment failure: a subgroup analysis of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Cephalalgia 2018; 38: 1611–1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goadsby PJ, Paemeleire K, Broessner G, et al. Efficacy and safety of erenumab (AMG334) in episodic migraine patients with prior preventive treatment failure: a subgroup analysis of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Cephalalgia 2019; 39: 817–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krymchantowski AV, Bigal ME.Polytherapy in the preventive and acute treatment of migraine: fundamentals for changing the approach. Expert Rev Neurother 2006; 6: 283–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Dowson AJ, et al. Development and testing of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) questionnaire to assess headache-related disability. Neurology 2001; 56: S20–S28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang M, Rendas-Baum R, Varon SF, et al. Validation of the Headache Impact Test (HIT-6™) across episodic and chronic migraine. Cephalalgia 2011; 31: 357–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tepper S, Ashina M, Reuter U, et al. Safety and efficacy of erenumab for preventive treatment of chronic migraine: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Neurol 2017; 16: 425–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Detke H, Goadsby PJ, Wang S.Galcanezumab in chronic migraine: the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled REGAIN study. Neurology 2018; 91: e2211–e2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-cep-10.1177_03331024211008401 for Fremanezumab for the Preventive Treatment of Migraine: Subgroup Analysis by Number of Prior Preventive Treatments with Inadequate Response by Ladislav Pazdera, Joshua M Cohen, Xiaoping Ning, Verena Ramirez Campos, Ronghua Yang and Patricia Pozo-Rosich in Cephalalgia

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-cep-10.1177_03331024211008401 for Fremanezumab for the Preventive Treatment of Migraine: Subgroup Analysis by Number of Prior Preventive Treatments with Inadequate Response by Ladislav Pazdera, Joshua M Cohen, Xiaoping Ning, Verena Ramirez Campos, Ronghua Yang and Patricia Pozo-Rosich in Cephalalgia

Data Availability Statement

For the analyses described in this manuscript, anonymized data will be shared upon request from any qualified investigator by the author investigators or Teva Branded Pharmaceutical Products R&D, Inc.