Conspectus

The fundamental repeating unit of chromatin, the nucleosome, is composed of DNA wrapped around two copies each of four canonical histone proteins. Nucleosomes possess 2-fold pseudo symmetry that is subject to disruption in cellular contexts. For example, post-translational modification (PTM) of histones plays an essential role in epigenetic regulation, and the introduction of a PTM on only one of the two “sister” histone copies in a given nucleosome eliminates the inherent symmetry of the complex. Similarly, the removal or swapping of histones for variants or the introduction of a histone mutant may render the two faces of the nucleosome asymmetric, creating, if you will, a type of “Janus” bioparticle. Over the past decade, many groups have detailed the discovery of asymmetric species in chromatin isolated from numerous cell types. However, in vitro biochemical and biophysical investigation of asymmetric nucleosomes has proven synthetically challenging. Whereas symmetric nucleosomes are readily formed via a stochastic combination of their histone and DNA components, asymmetric nucleosome assembly demands the selective incorporation of a single modified/mutant histone copy alongside its wild-type counterpart.

Herein we describe the chemical biology tools that we and others have developed in recent years for investigating nucleosome asymmetry. Such approaches, each with its own benefits and shortcomings, fall into five broad categories. First, we discuss affinity tag-based purification methods. These enable the assembly of theoretically any asymmetric nucleosome of interest but are frequently labor-intensive and suffer from low yields. Second, we detail transient cross-linking strategies that are amenable to the preparation of histone H3 or H4-modified/mutant asymmetric species. These yield asymmetric nucleosomes in a traceless fashion, albeit through the use of more complicated synthesis techniques. Third, we describe a synthetic biology technique based on generation of bump-hole mutant H3 histones that selectively heterodimerize. Although currently developed only for H3 and a related isoform, this method uniquely allows for the interrogation of nucleosome asymmetry in yeast. Fourth, we outline a method for generating H2A- or H2B-modified/mutant asymmetric nucleosomes that relies on the differential DNA-histone contact strength inherent in the Widom 601 DNA sequence. This technique involves the initial formation of hexasomes which are then complemented with distinct H2A/H2B dimers. Finally, we review an approach that utilizes split intein technology to isolate asymmetric H2A- or H2B-modified/mutant nucleosomes. This method shares steps in common with the former but exploits tagged, intein-fused dimers for the facile purification of asymmetric products.

Throughout the Account, we highlight various biological questions that drove the development of these methods and ultimately were answered by them. Though each technique has its own shortcomings, collectively these chemical biology tools provide a means to biochemically interrogate a plethora of asymmetric nucleosome species. We conclude with a discussion of remaining challenges, particularly that of endogenous asymmetric nucleosome detection.

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

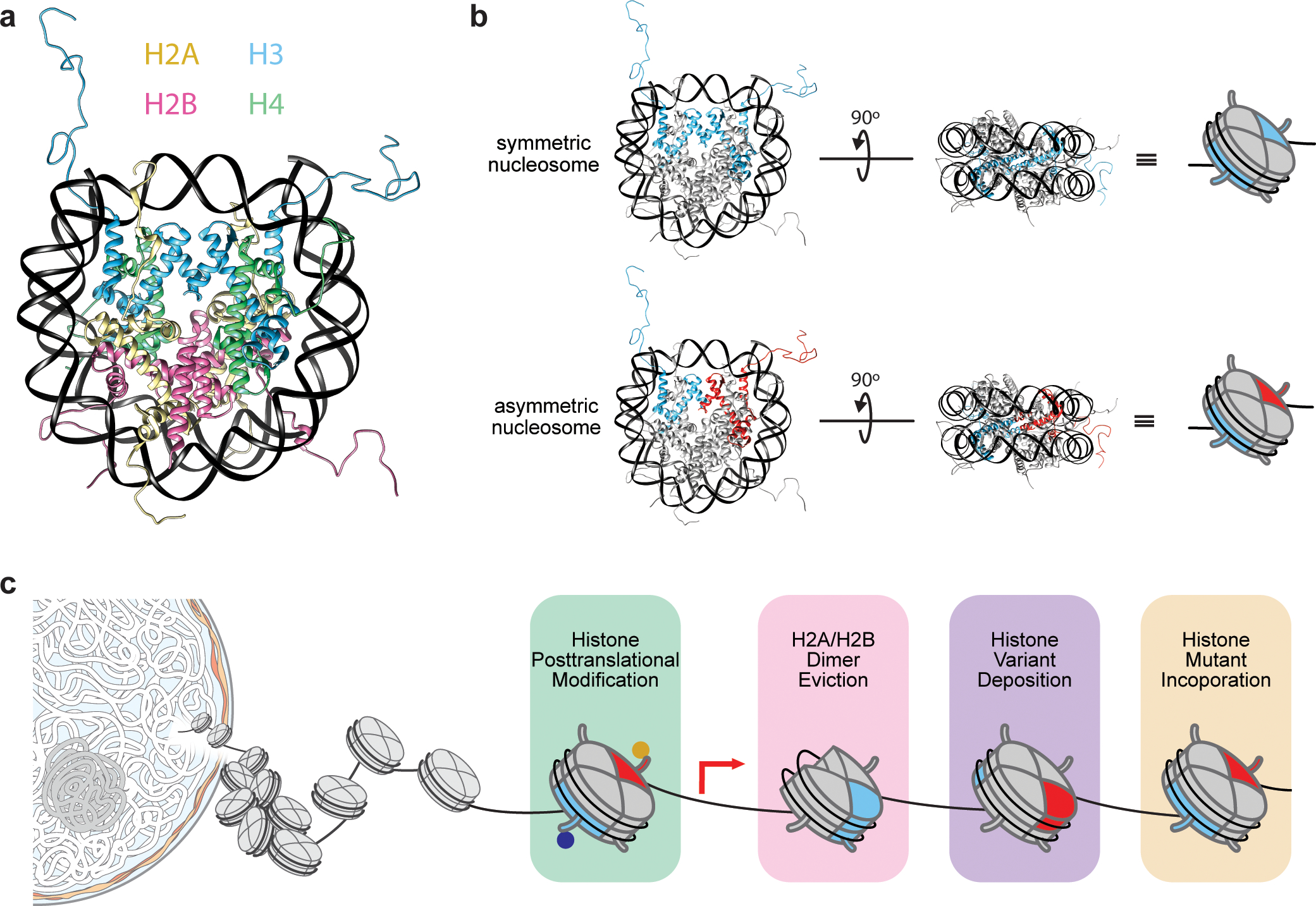

Chromatin, the physiologically relevant form of the eukaryotic genome, consists of repeating nucleosome units. Each nucleosome comprises 147 base pairs of DNA wrapped around an octameric protein core composed of two copies each of histones H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 (Figure 1a).3 The positioning and structure of nucleosomes regulate access to DNA by cellular machinery, ultimately controlling transcription, replication, DNA repair, and cell differentiation.4 Central to these processes is the direct chemical modification of histone proteins. Given that each histone has numerous amino acid residues that are subject to one or more PTMs (also referred to as “marks”), the combinatorial potential for modifications on a given nucleosome is enormous. This led Allis and colleagues, two decades ago, to hypothesize a ‘histone code’ in which PTMs act as dynamic signaling hubs that orchestrate nuclear events by directly affecting chromatin structure or by recruiting chromatin effector proteins.5,6

Figure 1.

Nucleosome structure and symmetry. (a) Ribbon diagram structure of the nucleosome, composed of two copies of each histone (color-coded) (PDB 1kx5). (b) Comparison of symmetric vs. asymmetric nucleosomes demonstrated by highlighting sister H3 histones in a given nucleosome. Symmetric nucleosomes bear two identical copies of histone H3 (blue), whereas asymmetric nucleosomes bear two different copies (blue and red). (c) Factors contributing to asymmetric nucleosome generation in the cell. Adapted with permission from ref 7. Copyright (2019) Springer Nature.7

Experimental studies in the decade following proffered ample support for this notion. Combinatorial marks, namely the trimethylation of lysine 4 on histone H3 (H3K4me3) and H3K27me3, were found to be enriched at transcriptional start sites in embryonic stem cells, a bivalency that resolved upon cellular differentiation to yield single PTMs in accord with observed changes in gene expression.8 The introduction of chromatin immunoprecipitation coupled to next-generation DNA sequencing (ChIP-seq) enabled genome-wide PTM association studies, revealing combinatorial patterns of acetylation and methylation defining various chromatin states in pluripotent and lineage-committed cells.9,10 However, the coexistence of certain marks (e.g., H3K27me3 and H3K4me3 or H3K36me2/3) in chromatin posed a temporary conundrum, as in vitro studies suggested that the latter two PTMs inhibit the activity of the methyltransferase responsible for deposition of the H3K27me3 mark, namely polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2).11

The question of how these PTMs might co-occur in chromatin was addressed when Voigt et al. postulated that a significant portion of nucleosomes are asymmetrically modified; that is, the two histone copies within a given nucleosome are modified differentially (Figure 1b).12 The group isolated individual nucleosomes from MNase-treated chromatin, selecting for those bearing specific PTMs using antibody-based affinity purification. Mononucleosomes were then subjected to derivatization, tryptic digestion, and LC-MS/MS quantification of PTM abundance. If nucleosomes were entirely symmetric, then 100% of histone peptides would be expected to bear the PTM of interest. Alternatively, asymmetric nucleosome populations would be expected to yield 50% modified peptides (as unmodified ones would be copurified with their PTM-bearing sister histone). Using this approach, they identified both symmetrically and asymmetrically modified nucleosomes (between 50 and 100% modified peptides) across several cell types. Moreover, they found that H3K27me3 and H3K4me3/H3K36me3 occur on separate histone H3 tails, a finding since confirmed by complementary single-molecule imaging studies.13 Furthermore, they demonstrated that PRC2 is inhibited by symmetric, but not asymmetric, active methyl marks,12 thereby harmonizing the apparent contradictory cellular and in vitro results.

Other pioneering work in the area of nucleosome asymmetry arose from the Pugh laboratory following their development of ChIP-exo, a method for identifying the precise locations of proteins across a genome to nearly single-base-pair resolution.14 Using this approach, Rhee et al. probed the nucleosome substructure and symmetry of more than 60 000 genomic sites in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, revealing the genome-wide organization of the four core histones, variant H2A.Z, linker histone H1, and various transcription-associated PTMs.15 Notably, they found that half of all +1 nucleosomes (with respect to the nucleosome-free region (NFR) of the transcriptional start site) show a significant difference in H2B occupancy on one-half of the nucleosome compared to the other. Such asymmetric species were confirmed to be hexasomes, which are by definition asymmetric species, and half-nucleosomes using various complementary techniques. They also detected asymmetric nucleosomes, noting H3K9ac and H2BK123ub marks were enriched on the NFR-proximal half of the +1 nucleosome, whereas variant H2A.Z was highly enriched on the NFR-distal half. Others have likewise demonstrated the presence of asymmetric H2A/H2A.Z nucleosomes at transcriptional start sites using ChIP-re-ChIP methods.16

Nucleosome asymmetry can be imparted not only by differential deposition of histone PTMs and variants but also by histone mutation (Figure 1c). Because of the polygenic nature of mammalian histones, mutations in these genes give rise to mutant histones that represent only a subset of the total histone pool. Stochastic incorporation of these histone mutants into cellular chromatin predominantly results in asymmetric nucleosomes containing one mutant and one wild-type histone. Indeed, immunoprecipitation of histone mutant-bearing mononucleosomes from cells also pulls down wild-type sister histones.17–19 Work from our laboratory and others over the past decade has revealed that histone mutations themselves may drive certain cancers,17,20–23 emphasizing the deleterious cellular effects that such mutations can have even in substoichiometric and asymmetric contexts.

Consequently, there is now little argument that asymmetric nucleosomes (and hexasomes) are physiologically relevant species. However, biochemical and biophysical characterization of asymmetric (or heterotypic) nucleosomes has been hampered by the fact that these species are more challenging to access synthetically than their symmetric (or homotypic) counterparts. Symmetric nucleosomes are readily formed via standard salt gradient dialysis assembly from their constituent symmetric histone octamers and DNA.24 The octamers themselves are assembled from histones under high-salt conditions, such that the incorporation of PTM-bearing histones or histone mutants at this point gives rise to mixtures of species. Hence, limitations in existing methods necessitated the development of new techniques for generating uniformly defined asymmetric octamer and/or nucleosome populations.

In this Account, we summarize the various chemical biology tools that have been developed over the past decade to generate asymmetric nucleosomes. Emphasis is placed on methodologies, but brief summaries of the biological findings each enabled are included. Moreover, we highlight the strengths and weaknesses of each approach and close with a discussion of ongoing challenges.

2. Tag and Purify Methods

The earliest of approaches to generate asymmetric nucleosomes came in the late 2000s when Li and Shogren-Knaak sought to understand how the yeast Spt-Ada-Gcn5-acetyltransferase (SAGA) complex is regulated by its chromatin substrate.25 SAGA regulates inducible gene transcription in S. cerevisiae by acetylating the N-terminal portions (or tails) of histones, primarily that of histone H3.26–29 However, the H3 tail was known not only to interact with the catalytic domain but also to bind to other SAGA complex subunits,30–32 raising the possibility that one or both of the histone H3 tails in a given nucleosome might regulate SAGA activity. Kinetic experiments with nucleosome arrays revealed cooperative acetylation that was also apparent with mononucleosome, but not peptide, substrates, leading researchers to speculate that the pair of H3 tails present in a nucleosomal context is essential for the observed cooperativity.

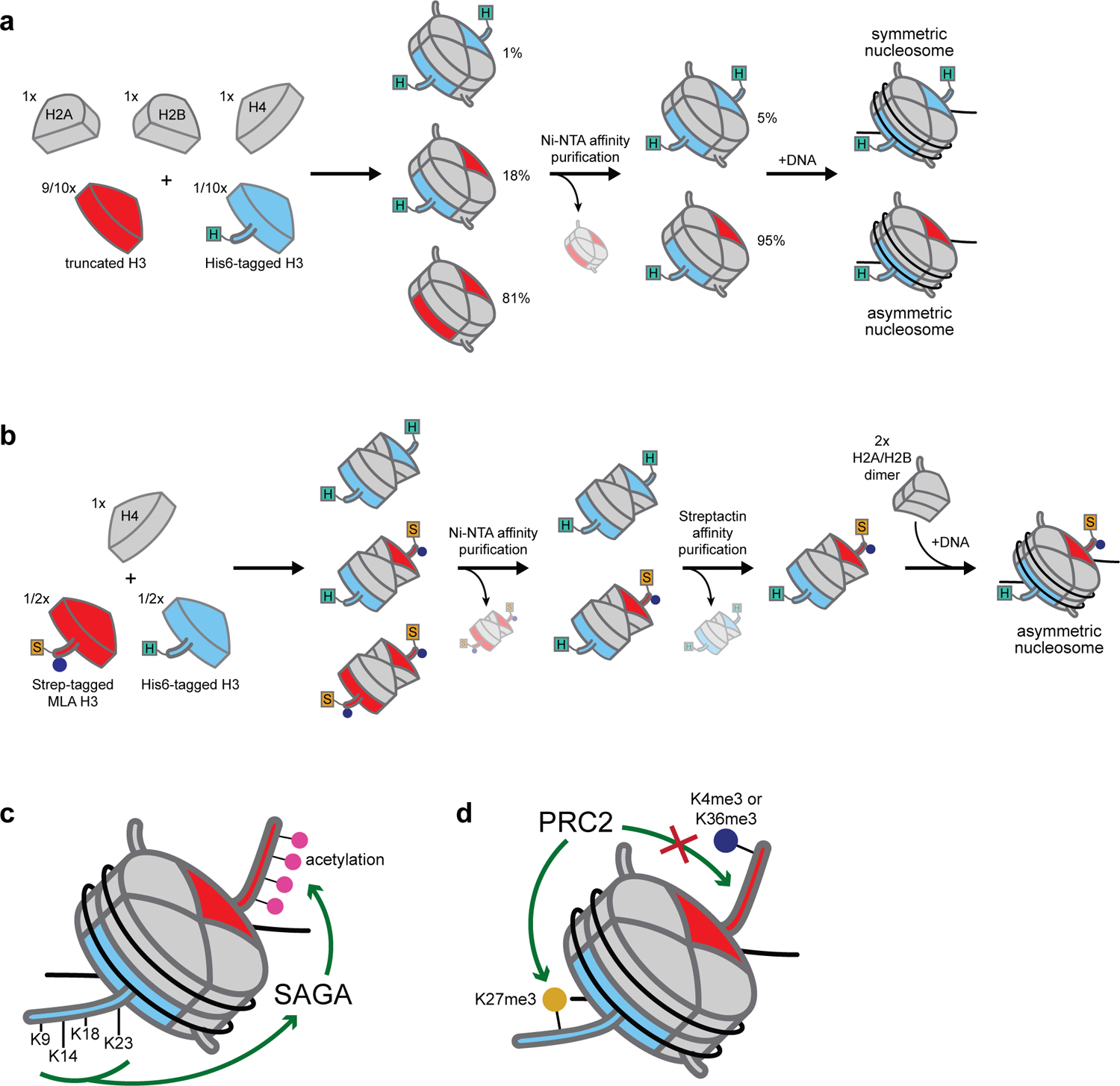

To test this hypothesis, the authors generated asymmetric octamers containing one full-length and one truncated H3 histone (Figure 2a). They prepared octamers from their constituent histones according to standard protocols24 but introduced different H3 histones as mixtures of untagged truncated H3 (lacking the first 24 amino acids) and His6-tagged full-length H3, with the untagged form in vast excess. The resultant octameric species consisted primarily of doubly truncated H3 octamers that were subsequently removed by affinity purification to yield symmetrically and asymmetrically tagged species. By altering the amounts of tagged and untagged H3 in the initial mixture, the researchers empirically determined that a 9:1 ratio would yield a population consisting of 95% asymmetric nucleosomes after nickel resin treatment. The authors proceeded to form nucleosomal arrays that resembled those generated using recombinant wild-type octamers. Asymmetric (one truncated H3 and one full-length His6-tagged H3) octamer-containing nucleosomal arrays proved noncooperative in SAGA-mediated acetylation. Importantly, the authors demonstrated that the retention of the His6 tag did not affect cooperativity. Additional asymmetric nucleosomes were generated by analogous methods wherein the truncated H3 histones were first chemically ligated to synthetic peptides in which all N-terminal lysines were replaced with alanines (1–24 tetra-Ala H3) or acetylated species (1–24 tetra-Ac H3), ultimately allowing the authors to show that SAGA cooperativity is mediated by enzyme recognition of free lysines in histone H3 tails (Figure 2c).

Figure 2.

Affinity tag-based methods for generating asymmetric nucleosomes and associated biochemical discoveries. (a) Method utilized by Li and Shogren-Knaack involving the incorporation of a single affinity tag. (b) Method of Voigt et al. in which two affinity tags are used and tandem-affinity purification yields a singular product. (c) SAGA enzymatic cooperativity is mediated by the complex recognition of unmodified lysines on histone H3 tails. (d) H3K4me3 and H3K36me3 inhibit PRC2 deposition of H3K27me3 in cis (on the same histone) but not in trans (on the sister histone).

This methodology, although enabling additional studies characterizing binding interactions between proteins and histone PTMs (e.g., heterochromatin protein 1 and H3K9me333), fails to give pure asymmetric nucleosome populations. In their landmark paper wherein Voigt et al. demonstrated the presence of asymmetrically modified nucleosomes in mammalian cells (Introduction), they addressed this methodological limitation by introducing a second affinity tag and an associated purification step (Figure 2b).12 Upon codetection of H3K27me2/3 and H3K36me3 or H3K4me3 within nucleosomes, despite contemporaneous studies suggesting the presence of these PTMs on the same histone tails was disfavored,34,35 the authors sought to assess the activity of the H3K27 methyltransferase PRC2 on nucleosome arrays bearing H3K4me3- or H3K36me3-modified octamers. To do so, they combined equal amounts of His-tagged wild-type H3 and Strep-tagged MLA (methyl-lysine analog) H3 with a stoichiometric quantity of H4 to generate tetramers. Following size-exclusion purification, tetramers were subjected to successive Ni-NTA and Strep-Tactin affinity chromatography steps to yield homogenous asymmetric tetramers. These were subsequently incubated with purified H2A/H2B dimers and DNA and reconstituted using standard methods to form chromatin arrays. In agreement with previous studies,11,35 PRC2 failed to methylate symmetrically modified H3K4me3 or H3K36me3 substrates but was unaffected by asymmetric ones (Figure 2d).

Additional groups expanded upon these techniques to synthesize asymmetric nucleosomes in a traceless fashion. Some modified the tandem-affinity purification approach by treating resultant asymmetric nucleosomes with TEV protease to remove all tags.36 Still others bypassed affinity-based purifications altogether, instead opting to add bulky tags which alternatively allow for the purification of asymmetric species by size using preparative native PAGE, followed by tag cleavage and an additional round of gel-based purification.37 One notable disadvantage of such methods is that all involve the generation of large excesses of “unwanted” (in this case, symmetric) species en route to the production of the desired asymmetric ones. Since these species must be removed to generate homogenous nucleosome populations, at least one additional purification step is required wherein material loss may occur. To synthesize “tagless” populations, additional purification steps are needed, with each one reducing product yields. Nevertheless, these “tag and purify” methods involve relatively straightforward biochemical techniques, afford reasonably pure products, and can be used to make mutant or PTM-bearing asymmetric species. These attributes render such methods important tools for investigating nucleosome asymmetry and in fact are the only ones that were available until quite recently.

3. Transient Cross-linking Strategies

Although affinity-based methods enabled generation of asymmetric nucleosomes bearing PTMs, most investigations of nucleosome asymmetry explored the effects of single histone PTMs, perhaps in part due to their preparative difficulty. However, studies have revealed the presence of asymmetric nucleosomes bearing active (H3K4me3/H3K36me3) and repressive (H3K27me3) marks on separate histone tails located at a subset of promoters in embryonic stem cells and some cancer cells.8,12 In order to investigate such bivalent chromatin domains, specifically the impact of these asymmetrically deposited PTMs on PRC2 activity, the Fierz group developed an ingenious method to generate all possible spatial arrangements of the aforementioned PTMs in a given nucleosome.38

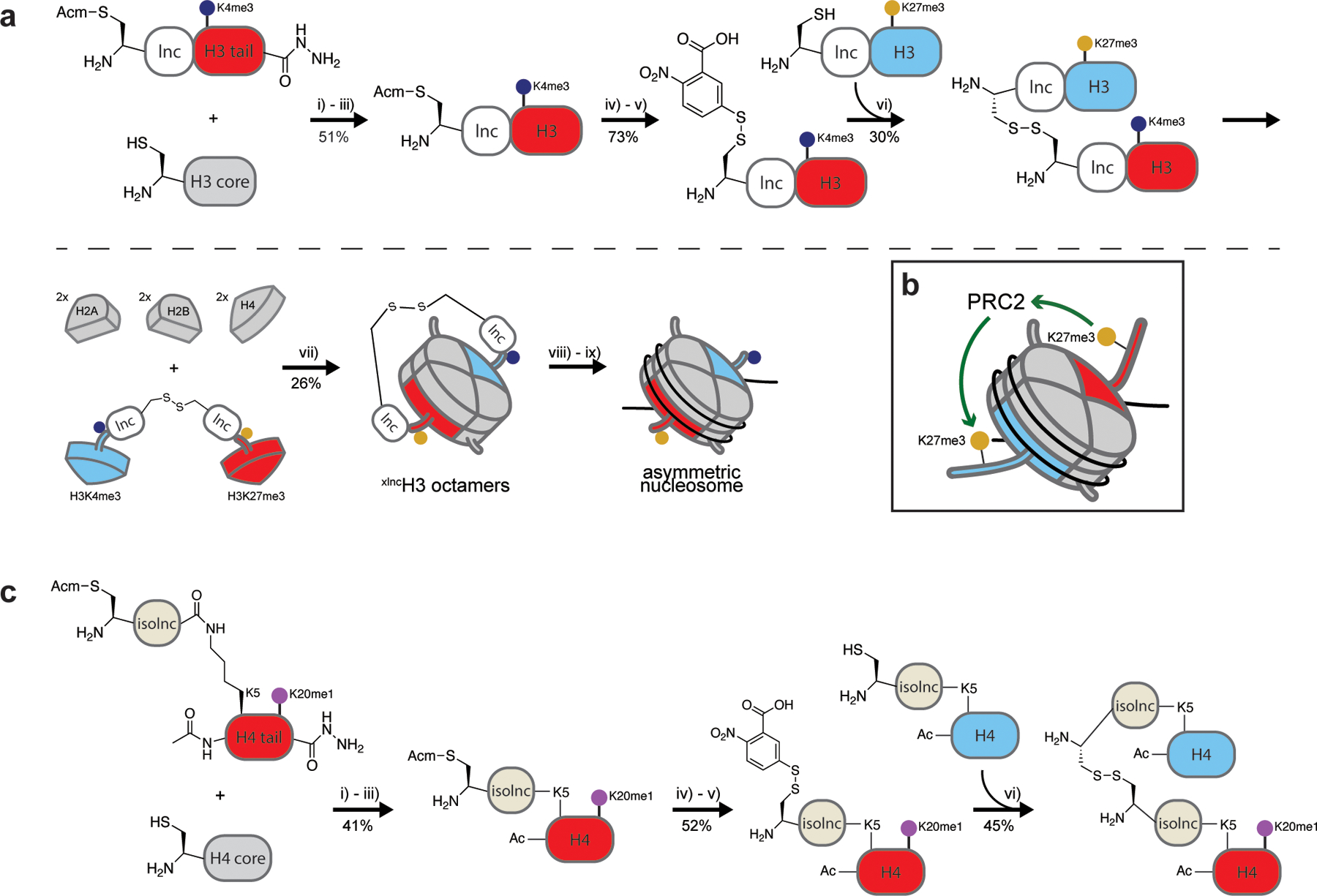

To ensure that two H3 molecules each with distinct PTMs were incorporated into a single octamer and that the synthesis would ultimately be traceless (thus avoiding potential tag interference in downstream biochemical assays), the group employed a transient cross-linking strategy (Figure 3a). This approach involves adding “link and cut” tags (lnc-tags), short (11 amino acid) peptide sequences including a protected N-terminal cysteine and a TEV protease site, prior to the native H3 amino acid sequence. A peptide hydrazide consisting of the lnc-tag and desired histone PTM(s) is first generated by solid-phase peptide synthesis and converted in situ to an α-thioester. Native chemical ligation is then used to link this peptide to recombinant truncated H3 bearing a N-terminal cysteine.39 Radical desulfurization of cysteine to alanine yields the native full-length histone bearing the lnc-tag and PTM(s) of interest. Each H3 histone pool is then independently subjected to N-terminal cysteine deprotection, and a single pool is activated by same-pot addition of 5’5’-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid). The combination of these pools gives heterodisulfide-linked H3 dimers that can then be combined with their complementary core histones to form octamers by standard methods. Following the FPLC purification of octamers, DTT reduction of the disulfide bond and TEV protease removal of lnc-tags yield asymmetric PTM-bearing octamers for incorporation into nucleosomes.

Figure 3.

Transient cross-linking strategies for synthesizing asymmetric nucleosomes bearing unique (a) H3 or (c) H4 histones and related biochemical findings. First, the lnc-peptide hydrazide is converted to a thioester (i) which is then ligated to a truncated histone protein (H3 or H4 core, respectively) (ii) and desulfurized in situ (iii). Next, the N-terminal cysteine is deprotected (iv) and modified in situ with DTNB (v). A heterodisulfide is then formed (vi). These linked asymmetric histones are refolded with stoichiometric amounts of the other core histones to form cross-linked asymmetric octamers (vii). Finally, nucleosomes are reconstituted, the disulfide bond is reduced (viii), and cross-links are cleaved by the addition of TEV protease (ix). The final two steps are similar for both H3 and H4 asymmetric nucleosome generation and are therefore depicted only in panel (a). Reported yields are indicated. (b) H3K27me3 stimulates PRC2 methyltransferase activity in trans.

Using this method, Fierz and co-workers generated all possible bivalent combinations of H3K4me3/H3K27me3 asymmetric nucleosomes. Substrate testing with PRC2 revealed that H3K4me3 blocks enzyme activity only in cis (i.e., within the same histone protein) (Figure 2d), whereas H3K27me3 has a stimulatory effect on the enzyme in trans that can partially override the inhibitory nature of H3K4me3 (Figure 3b). More recently, the same group employed a modified version of this strategy to determine the effect of H3K36me3 on PRC2 activity.40 Given the distance of this PTM from the histone N-terminus and the inherent length limitations for peptides generated by solid-phase synthesis, the group employed a three-piece ligation strategy to generate the lnc-tagged H3K36me3 histone. Combinatorial generation of H3K27me3/H3K36me3 nucleosomes then proceeded as before. In these studies, the group determined that K36me3 inhibits PRC2 activity in cis (Figure 2d), whereas K27me3 stimulates enzymatic activity in trans (as previously shown38) (Figure 3b).

The aforementioned study reporting the existence of asymmetric bivalent nucleosomes also reported nucleosomes asymmetrically modified with H4K20me1,12 prompting the Fierz group to apply a similar approach to generate linked H4 dimers (Figure 3c).41 However, in native contexts, H4 is N-terminally acetylated, rendering the original N-terminal lnc-tag approach used for H3 unsuitable. In a clever solution to this problem, they installed the lnc-tag at H4K5 via an isopeptide bond between lysine and the C-terminal glutamine of the lnc-tag. This so-called “isolnc-tag” is susceptible to TEV protease cleavage, presumably due to the sequence similarity of the glutamine-lysine isopeptide bond and the canonical TEV cleavage site. The synthesis of asymmetric octamers and nucleosomes then proceeded as for H3, followed by TEV protease treatment to remove the lnc-tags (either before or after nucleosome formation). The group then determined the effect of pre-existing asymmetric H4K20me1 on the activity of its cognate methyltransferase, Set8. Unlike PRC2, which is stimulated in trans by the mark it deposits (H3K27me3), Set8 activity is unaffected by the presence H4K20me1 in this context.

In contrast to affinity tag-based methods that require purification steps to isolate asymmetric nucleosomes from a mixture of species, this transient-crosslinking approach directly generates the desired asymmetric product(s). The generation of individually modified histones that can then be selectively activated for heterodisulfide-based cross-linking also renders this method highly modular. Precursor post-translationally modified histones serve as building blocks that can be mixed and matched to generate a combinatorial array of asymmetrically modified nucleosomes. Furthermore, cross-link reversal under reducing conditions followed by TEV cleavage of the lnc-tags affords traceless assembly of nucleosomes. Nevertheless, many steps are required to assemble the desired asymmetric species, and to date, this strategy has been applied only to histones H3 and H4. Moreover, the chemical synthesis techniques used to generate and deprotect lnc-tags and install and deinstall cross-links might prove cumbersome to some research groups or superfluous to others who simply wish to study histone variants or mutations.

4. Bump-Hole Mutant Heterodimerization Approach

In 2017, Ichikawa et al. developed a technique for asymmetric nucleosome generation that bypasses the use of tags and affinity purification entirely.42 The group reasoned that the strategic introduction of mutations at the interface between histone H3 molecules could be used to generate an H3 pair that would selectively dimerize with each other. By employing a directed evolution approach at each of four H3 codons (109, 110, 126, and 130) in S. cerevisiae, the team created “bumps and holes” in a pair of histone H3 molecules that drastically decreased their homodimerization potential. The resultant pair of H3 molecules, termed H3X (L126A, L130V) and H3Y (L109I, A110W, L130I), failed to form homodimers but efficiently formed heterodimers (Figure 4a). The expression of tagged H3X/H3Y histones in yeast followed by the isolation of mononucleosomes and affinity purification to assess histone binding partners revealed 97% pure asymmetric populations. Notably, the generation of analogous mutations on the human histone backbone also gave heterodimer-forming H3 pairs. Recombinantly expressed human H3X and H3Y, when combined with the other core histones, form asymmetric octamers that can be used to generate nucleosomes. Like their yeast counterparts, human H3X and H3Y fail to form octameric species in the absence of their heterodimeric partner.

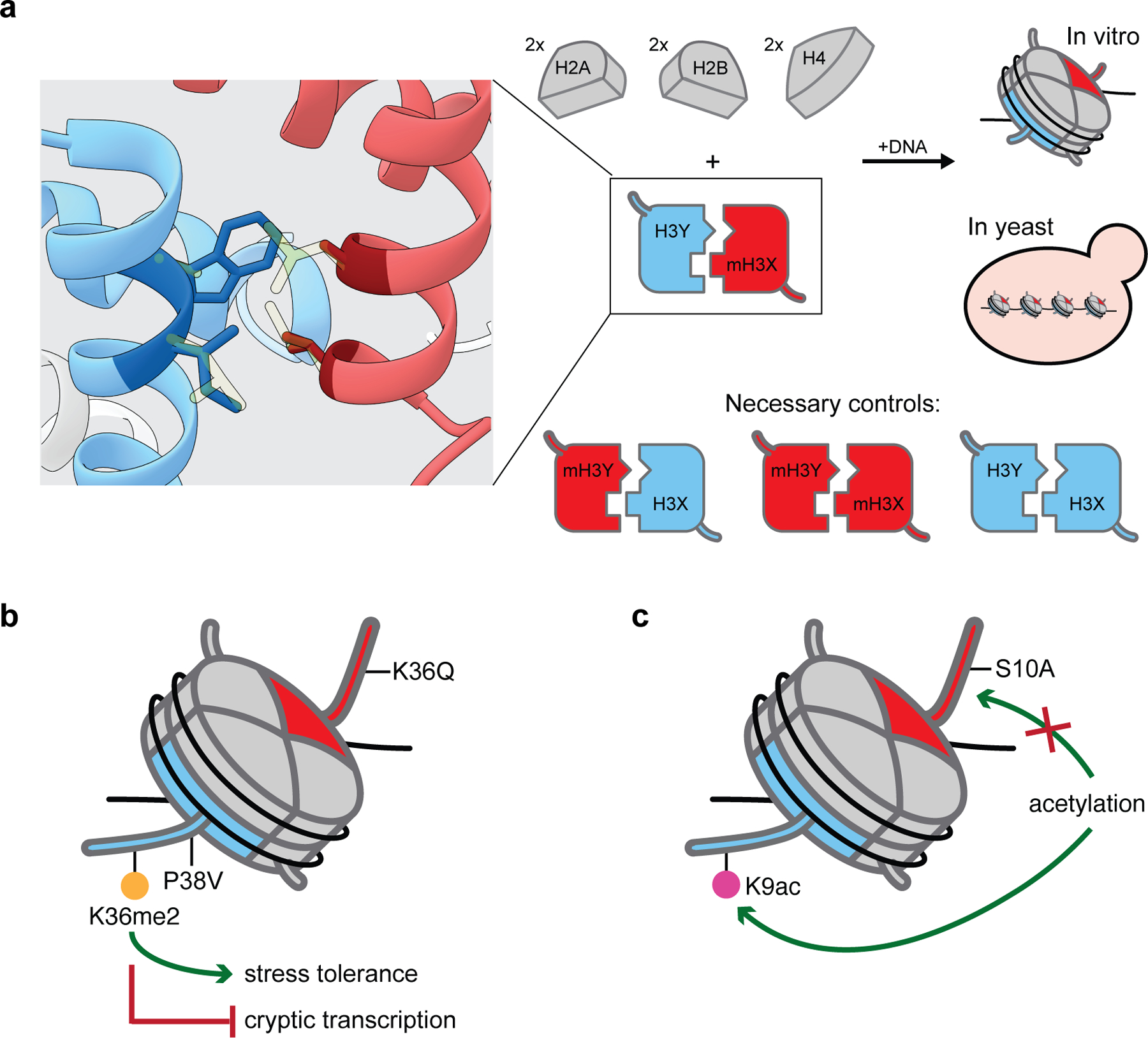

Figure 4.

Bump-hole mutant heterodimerization approach and associated biological discoveries. (a) Bump-hole heterodimeric H3 histones selectively dimerize with each other via an altered H3-H3 interface. Depicted are residues mutated to form the bump (H3Y: L109I, C110W) and hole (H3X: L126A, I130V) heterodimeric human histone H3 pair (PDB 1kx5); native residues are shown in translucent light yellow, and bump-hole residues are displayed in dark colors. Asymmetry may then be introduced via the additional mutation of residues within a single histone of the pair (e.g., mH3X). Additional controls are required because bump-hole histone pairs, by design, form a non-native H3-H3 dimer interface. (b) A single H3K36me2 modification (afforded by H3P38V mutation) is sufficient to promote stress tolerance and block cryptic transcription in S. cerevisiae. (c) H3S10A mutation (as a mimetic for loss of serine phosphorylation) inhibits H3K9 acetylation in cis but not in trans in yeast.

The group then set out to answer two biological questions using this bump-hole mutant heterodimerization approach in yeast. First, it had been demonstrated that H3K36 methylation plays a key role in silencing cryptic internal promoters via activation of the RPD3S histone deacetylase complex43 and that this complex can bind nucleosomes with a single H3K36me3 modification.44 However, whether a single methylated H3K36 molecule in a given nucleosome was sufficient to silence cryptic transcription in cells had not been established. To address this, the team genetically encoded strains bearing K36Q (loss of the methylation site) and P38V (causes K36 to be dimethlyated45,46) on opposing histones. Such asymmetric nucleosome-bearing yeast proved insensitive to growth under high-temperature conditions or exposure to DNA-damaging agents and restrained cryptic transcription, suggesting that a single H3K36me2 modification is sufficient to promote stress tolerance and block cryptic transcription in yeast (Figure 4b). Second, the group sought to interrogate whether the established role of H3S10ph in reducing H3K9 acetylation36,47 occurred only on a single histone tail or also in trans. Using H3S10A as a mutant mimetic for the loss of serine phosphorylation and by selectively tagging one member of the heterodimeric histone pair or the other, the group demonstrated by Western blot and mass spectrometry that H3S10A affects H3K9 acetylation in cis but not in trans (Figure 4c). Shortly thereafter, Zhou et al. published an analogous approach detailing their generation of a heterodimeric H3 pair (H3D/H3H) bearing bump-hole mutations at the same H3-H3 dimerization interface.48 Likewise, the group used their method to assess the function of asymmetric marks in yeast, including the role of H3K79 methylation in telomere-proximal gene silencing and H3K4 methylation in transcriptional responses to glucose starvation. More recently, they used the same system to determine that combinatorial H3K4me0/H3K36me3 marks are required on both sister H3 tails for efficient Dnmt3a-Dnmt3L-mediated DNA methylation.49

This approach to generating asymmetric nucleosomes bears the unique advantage of not requiring the affinity-based purification or cleavage of linkages/tags, as the genetic modifications introduced into the histone sequences are sufficient to induce exclusive heterodimer formation. Moreover, it bypasses some of the chemical synthesis challenges of the aforementioned transient cross-linking approach. The elimination of purification steps doubtless decreases labor requirements and increases product yield. Furthermore, genetic encoding of mutants enables cellular studies of asymmetric nucleosomes not merely in vitro ones. However, a few limitations of this methodology are noteworthy. The mutations introduced to ensure exclusive heterodimerization of the unique H3 histones necessarily generate a non-native H3-H3 interface. Besides the obvious restriction this puts on assessing mutations at those heterodimerization-essential sites, it renders the two H3 molecules inherently inequivalent. In their experiments, the various groups addressed this concern by always generating mutant trios (using the nomenclature of Ichikawa et al.: mXY, XmY, and mXmY, where m = mutant) so that they could discern whether mutating H3X provided similar results as mutating H3Y and then comparing those asymmetric species to the entirely symmetric mXmY (Figure 4a).42,48 Although mXY and XmY pairs often behaved similarly, differences did on occasion arise, demonstrating the importance of evaluating the biochemical/biophysical behavior of both before generalizing the observed behavior. Furthermore, pseudo-wild-type heterodimeric pairs must be generated for comparison with their mutant counterparts, as H3X/H3Y yeast showed reduced growth rates and modest temperature sensitivity42 and H3D/H3H yeast displayed some differences in the carbon source preference and nucleosome positioning48 compared to their true wild-type counterparts. Finally, although theoretically amenable to other histones and an assessment of the effects of PTMs, this method has been developed only for H3 and its centromeric isoform, CENP-A,50 and was used to interrogate histone mutations.

5. Oriented Hexasome-Based Assembly

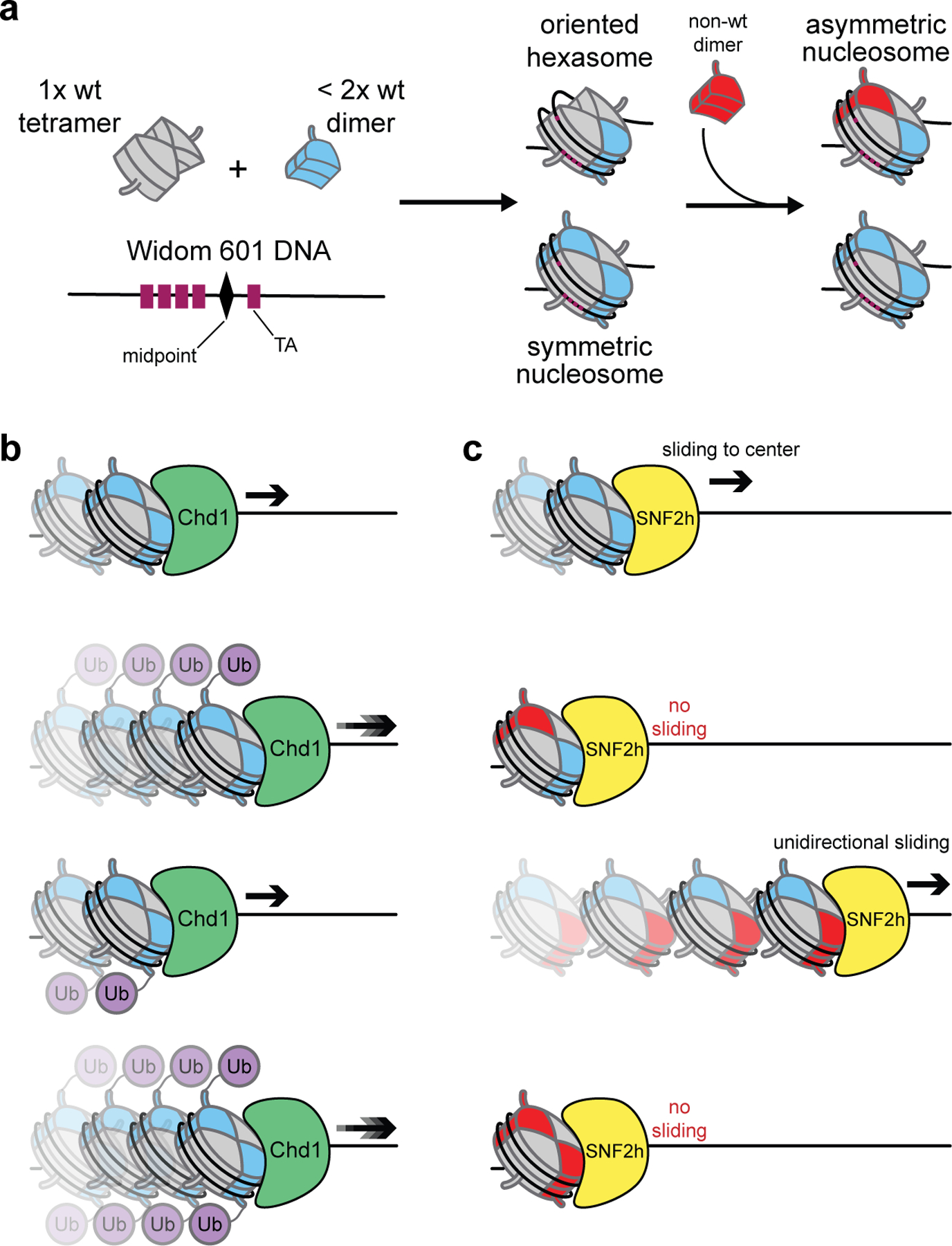

The Bowman group has developed extremely useful methods to evaluate the asymmetric modification of histones H2A and H2B by exploiting that fact that deviation from stoichiometric histone molarities during assembly gives rise to subnucleosomal products.51 Biochemical analysis revealed these to be hexasomes, stable subnucleosomal species consisting of two copies each of histones H3 and H4 but only one H2A/H2B dimer (Figure 5a). By probing the DNA accessibility using Exonuclease III digestion on hexasomes assembled on a strong Widom 601 positioning sequence,52 the group determined that the location of the one H2A/H2B dimer is dictated by a unique feature of this DNA. Specifically, the 601 sequence is asymmetric with respect to DNA-histone contact strength with four TA steps on one side, which is more salt-stable,53 and only one on the other, which preferentially unwraps under force.54 Accordingly, they found that the H2A/H2B dimer absent from the hexasomes was missing from the TA-poor side of the DNA sequence. Since nucleosomes may be formed upon addition of H2A/H2B dimers to hexasomes,55 the group reasoned that beginning with these “oriented hexasomes” they could generate asymmetric nucleosomes upon complementation with alternative H2A/H2B dimers.

Figure 5.

Oriented hexasome-based asymmetric nucleosome assembly and attendant biochemical findings. (a) Formation of DNA sequence-oriented asymmetric nucleosomes based on hexasome complementation with H2A/H2B dimers. (b) Entry-side H2B ubiquitination increases the rate of Chd1-mediated nucleosome remodeling. (c) Asymmetric acidic patch mutant nucleosomes are remodeled differentially by SNF2h based upon mutant location with respect to the DNA overhang.

Desiring to explore the effects of hexasomes and asymmetric nucleosomes on Chd1-driven chromatin remodeling, they used this oriented hexasome-based approach to generate a single, uniform FRET pair suitable for single-molecule studies. Chromatin remodeling (sliding) of substrates was monitored by incorporation of a single fluorescent dye (Cy3) on H2A of one dimer pair and the assembly of hexasomes or asymmetric nucleosomes on Cy5-labeled DNA. After first demonstrating that Chd1 requires an H2A/H2B dimer on the entry side of the nucleosome for efficient sliding using hexasome substrates, the group wanted to assess which portions of the dimer were essential for this activity. Thus, they assembled asymmetric nucleosomes by complementing oriented hexasomes with mutant H2B, mutant H2A, and C-terminally truncated H2A-containing dimers. Importantly, wild-type nucleosomes assembled in this manner and those produced by traditional salt dialysis appeared to be indistinguishable by native gel electrophoresis and exhibited similar sliding rates upon incubation with Chd1. As none of these mutations significantly inhibited Chd1 activity, the group then assessed the effect of ubiquitinated H2B on the enzyme, as both are associated with Pol II transcription.56–58 By generating all four possible combinations (modified/unmodified, entry side/exit side) of asymmetric nucleosomes, they were able to deduce that the presence of H2B-Ub on the entry side of the nucleosome enhances Chd1 remodeling rates (Figure 5b).

Within the past few years, both the Bowman group and ours have used this method to interrogate the consequences of mutations in the nucleosome acidic patch.1,59 This negatively charged epitope present in the globular domains of H2A and H2B serves as a hotspot for protein binding,60,61 and we have shown that alterations in and around this motif disrupt the activity of various chromatin remodelers.62 By generating nucleosomes with either one or both acidic patches mutated in a position-specific manner, Levendosky et al. demonstrated that ISWI chromatin remodeler activity is more affected by entry-side dimer acidic patch mutations, whereas Chd1 activity is equally affected regardless of acidic patch mutant location.59 Our group confirmed these findings in the context of ISWI remodeler SNF2h by showing that asymmetric nucleosomes bearing acidic patch mutations proximal to the DNA overhang (the initial direction of movement for the remodeler) were not remodeled, whereas nucleosomes with a single mutated acidic patch distal to the DNA overhang were remodeled at a normal rate but shifted solely unidirectionally (Figure 5c).1 In these experiments, remodeling was monitored by electrophoretic mobility shift assay, thus eliminating the need for FRET pair incorporation. Alternatively, a single Cy5-labeled dimer was used for complementation-based formation of nucleosomes, enabling exclusive monitoring of asymmetric nucleosome remodeling without the need to purify away unwanted homotypic species.

Oriented hexasome-based assembly complements previous methods by providing access to H2A and H2B mutant and PTM-bearing asymmetric nucleosomes. Uniquely, this method yields tracelessly assembled nucleosomes with specific orientations relative to the underlying DNA sequence. This enables control over which nucleosome face presents the mutation/modification and has led to novel insights regarding the chromatin remodeler engagement of such “Janus” substrates. Unfortunately, this method produces undesired symmetric nucleosome side products as well. These must be either purified away, for example by preparative native gel electrophoresis,51 or rendered invisible to assay readout by other means.1

6. Tagged Split-Intein Method

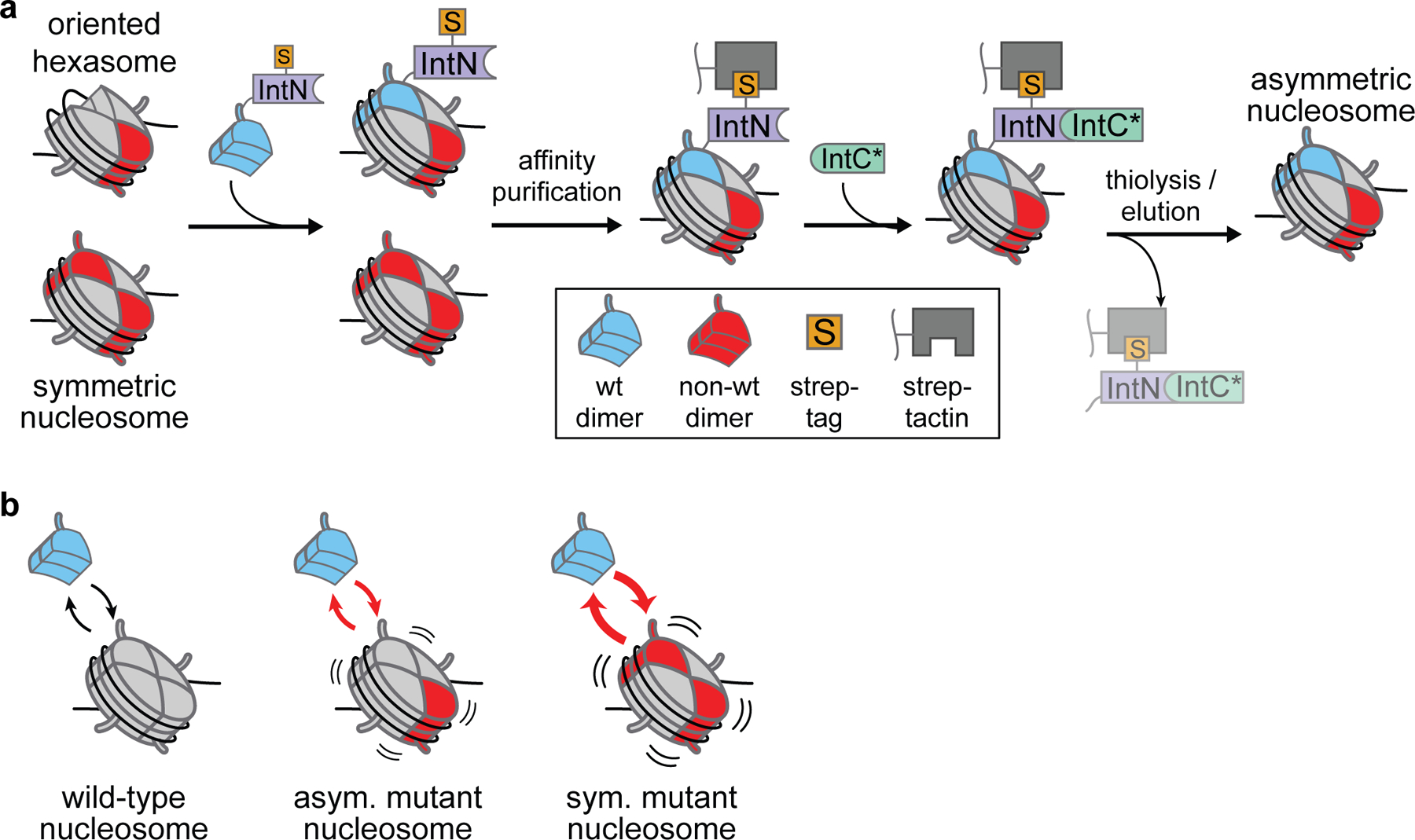

We recently performed a comprehensive functional analysis of the histone mutational landscape in human cancers, identifying point mutations that affect chromatin remodeling processes such as nucleosome sliding and dimer exchange.2 Although initial screens were carried out on more synthetically accessible symmetric nucleosome substrates, we wanted to determine if the observed effects were also exhibited in asymmetric contexts. Two H2A/H2B dimer-H3/H4 tetramer interface mutations, namely H2BE71K and H2BE76K, had pronounced effects on both dimer exchange and nucleosome thermal stability. The synthesis of these asymmetric mutant nucleosomes demanded a method amenable to single mutant H2B incorporation and subsequent isolation of the asymmetric product.

Therefore, we developed a method that utilizes split intein technology to purify asymmetric species away from their homotypic counterparts (Figure 6a). First, Widom 601 DNA, H3/H4 tetramers, and non-wild-type H2A/H2B dimers are combined in a 1:1:1.2 ratio, giving rise to approximately equal amounts of hexasomes and nucleosomes in a method akin to the oriented hexasome approach described in the previous section. Next, wild-type H2A/H2B dimers fused to the Cfa63 N-intein fragment and a Streptag are added to the mixture to complement existing hexasomes. Finally, streptagged nucleosomes are isolated by Strep-Tactin affinity resin purification and eluted by on-resin thiolysis with a catalytically dead Cfa C-intein,63,64 affording asymmetric nucleosomes of interest without any residual tags. Asymmetric H2BE71K and H2BE76K nucleosomes also exhibited increased dimer exchange and decreased thermal stability, albeit to about half the extent of their symmetric counterparts (Figure 6b). Therefore, these mutations confer nucleosomal instability in the context in which they probably occur in cells.

Figure 6.

Schematic of asymmetric nucleosome assembly using split inteins and associated biochemical/biophysical discoveries. (a) Mixtures of oriented hexasomes and symmetric nucleosomes are combined with tagged N-intein fragment (IntN)-linked H2A/H2B dimers. These asymmetric nucleosomes are affinity-isolated and then tracelessly eluted by on-resin thiolysis via the addition of catalytically dead C-intein fragment (IntC*). Adapted with permission from ref 2. Copyright (2021) Springer Nature. (b) Asymmetric mutant (H2BE71K or H2BE76K) nucleosomes exhibit increased dimer exchange and decreased thermal stability, albeit to a lesser extent that their symmetric mutant counterparts.

Like its related oriented hexasome-based method, this approach generates oriented asymmetric nucleosomes in a traceless fashion. However, the exploitation of split intein technology improves upon the previous method by providing a means for affinity purifying the desired asymmetric product directly, thus eliminating potential material loss suffered from preparatory native gel purification of the desired species. Notably, this method is also amenable to the generation of both mutant and post-translationally modified asymmetric nucleosomes; indeed, initial proof-of-concept studies were performed with ubiquitinated H2B.2 Notwithstanding these benefits, this method is applicable only to the generation of asymmetric H2A and H2B mutant/modified nucleosomes.

7. Outlook and Perspectives

Herein we have detailed the various chemical biology techniques currently available for generating asymmetric nucleosomes and briefly summarized the advances in understanding the epigenetic processes that each has enabled. The ideal technique would allow for traceless, modular incorporation of any or all of the four histones bearing mutations or PTMs in an asymmetric manner. Additionally, it would enable control of the deposition of these marks relative to the DNA sequence (i.e., orientation-specific incorporation) and require few purification steps so as to maximize product yield. Although none of the current techniques fit all of these criteria, collectively they enable production of most asymmetric nucleosomes of possible interest. Transient cross-linking strategies provide access to post-translationally modified H3 and H4 nucleosomes, albeit with some more challenging synthetic steps required. Similarly, the bump-hole mutant heterodimerization method gives rise nearly exclusively to asymmetric species, making it highly amenable to the interrogation of H3 mutants in asymmetric contexts both in vitro and in yeast. Oriented hexasome-based assembly and the tagged split-intein method provide complementary ways to analyze asymmetries present on H2A or H2B. Both provide for the traceless, orientation-specific deposition of mutant/modified histones to form asymmetric nucleosomes, with the latter technique having the added advantage of a built-in purification step. Finally, tag and purify methods, although requiring numerous rounds of purification that reduce overall yields, theoretically enable the production of any asymmetric nucleosome of interest.

Nevertheless, the shortcomings of these methods leave ample room for improvement. For example, while mutant or modified H2A or H2B histones may be deposited in an orientation-specific manner on DNA, currently histone tetramers (H3 and H4) cannot. Moreover, methods amenable to orientation-specific deposition of histones on non-Widom 601 DNA are lacking. Although this strong nucleosome positioning sequence is commonly used as it yields highly homogenous nucleosome populations, scenarios could be envisioned wherein the generation of asymmetric nucleosomes on endogenous DNA sequences would be informative. An additional methodological shortcoming with respect to generation of asymmetric H3/H4 nucleosomes lies in the fact that transient cross-linking methods for synthesis of these species employ more challenging chemistries. Even if histone mutations (as opposed to PTMs) are to be studied, then the selective protection of the N-terminal cysteine of the lnc-tag necessitates steps beyond simple recombinant protein expression. Finally, no studies have reported the synthesis of asymmetric mutations/marks on non-sister histones in a given nucleosome. Although theoretically possible using a combination of currently available techniques, the generation of such species would likely prove cumbersome given the number of preparatory steps required.

Beyond the remaining challenges associated with the preparation of asymmetric nucleosomes, the issue of detecting and characterizing these “Janus” bioparticles in native chromatin persists. Various methods to detect and quantify asymmetric PTM-bearing nucleosomes have been developed, including ChIP-re-CHIP, ChIP-qMS, ChIP-exo, and middle-down histone MS, each with their own strengths and weaknesses that have been expertly summarized elsewhere.65 The detection of low-abundance species is particularly problematic, although immunoprecipitation-based enrichment strategies often prove helpful in this regard. However, many antibodies are notoriously nonspecific, especially in the presence of neighboring PTMs (i.e., epitope occlusion). Recently developed antibody-free based methods may help circumvent these problems. For example, matrix-assisted reader chromatin capture (MARCC) facilitates the enrichment of PTM-bearing mononucleosomes through the use of recombinant reader domains purified as HaloTag fusions that can be linked to affinity resin.65 Histone PTM analysis by Western blot or mass spectrometry follows, as well as DNA analysis by qPCR or sequencing if genome-mapping information is desired. Improved methods of purifying native chromatin fragments66 have also prompted entirely MS-based analyses of nucleosome composition. Unlike traditional MS protocols that eliminate the link between PTMs and their nucleosomes of origin by denaturing and digesting histones prior to detection, such methods preserve this knowledge through the analysis of whole nucleosomes. This is nicely illustrated by recent work from the Kelleher group, who deployed a three-stage tandem MS approach, Nuc-MS, to analyze co-occurring histone PTMs, variants, and mutations in intact nucleosomes, in the process documenting the existence of asymmetric patterns of modification in cellular chromatin.67 Still, the analytical challenges associated with high-confidence genome-wide mapping of nucleosome asymmetry remain formidable, especially in mammalian cells. Opportunities certainly exist for innovations that provide proteomic data on the compositional heterogeneity of nucleosomes and whether such asymmetry occurs with an orientation bias with respect to the underlying genomic DNA sequences.

As is hopefully evident in this Account, chemical biology tools for studying nucleosome asymmetry in vitro have arisen in lockstep with cellular studies detailing the existence of such species in vivo. However, there is reason to believe that we are just scratching the surface of this area of research. For example, there exists the potential for (a)symmetry as one moves beyond the mononucleosomal context: consider the different orientations possible for two adjacent asymmetric nucleosomes where one can envision proximal or distal positioning of an asymmetric histone across the interface. Such higher-order geometric considerations may be important for how certain chromatin effectors engage their substrates, given that we now know that multinucleosomal engagement can indeed occur.68,69 Suffice it to say, nucleosome asymmetry provides an added dimension to the already combinatorially complex histone code, one that offers ample opportunities for experimental investigation in the years to come. In this regard, the “Janus” analogy used throughout this Account may be especially apt in the sense that we may be transitioning to a new era of biochemical analysis in the chromatin area.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the National Institutes of Health (NIH, R37 GM086868 and P01 CA196539) for financial support. M.M.M. was supported by an NIH postdoctoral fellowship (GM131632). We also thank members of the Muir laboratory past and present and of the C. David Allis laboratory (Rockefeller University) for helpful discussions in the preparation of this review.

Biographies

Michelle M. Mitchener received her B.S. in chemistry and molecular and cellular biology from Cedarville University in 2012. She completed her Ph.D. in chemistry under the direction of Lawrence J. Marnett at Vanderbilt University in 2017. Her research interests in protein biochemistry and chemical biology prompted her to pursue postdoctoral studies in the laboratory of Tom W. Muir at Princeton University, where she is currently investigating the biochemical and cellular consequences of cancer-associated histone mutations.

Tom W. Muir received his B.Sc. in chemistry from the University of Edinburgh in 1989 and his Ph.D. in chemistry from the same institute in 1993 under the direction of the later Professor Robert Ramage, FRS. Following postdoctoral studies with Stephen B. H. Kent at The Scripps Research Institute, Muir joined the faculty of The Rockefeller University in 1996, where he rose through the ranks, eventually being appointed the Richard E. Salomon Family Professor and Director of the Pels Center of Chemistry, Biochemistry and Structural Biology. In 2011, he joined the faculty of Princeton University as the Van Zandt Williams Jr. Class of ‘65 Professor of Chemistry, serving as Chair of the Chemistry Department from 2015 to 2020. A chemical biology, Muir has made many contributions to the fields of peptide and protein chemistry. He is best known for developing general methods for the preparation of proteins containing unnatural amino acids, posttranslational modifications (PTMs), and isotopic probes. These chemical tools, now widely employed in academia and industry, have yielded detailed functional insights into many systems including protein kinases, ion channels, and chromatin. His current interests lie principally in the area of epigenetics, where he is interested in how changes to chromatin structure drive different cellular phenotypes.

Footnotes

Complete contact information is available at: https://pubs.acs.org/10.1021/acs.accounts.1c00313

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dao HT; Dul BE; Dann GP; Liszczak GP; Muir TW, A basic motif anchoring ISWI to nucleosome acidic patch regulates nucleosome spacing. Nature Chemical Biology 2020, 16, 134–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Application of the oriented hexasome-based assembly method to study the effects of asymmetric acidic patch mutations on ISWI-mediated chromatin remodeling.

- 2.Bagert JD; Mitchener MM; Patriotis AL; Dul BE; Wojcik F; Nacev BA; Feng L; Allis CD; Muir TW, Oncohistone mutations enhance chromatin remodeling and alter cell fates. Nature Chemical Biology 2021, 17, 403–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Introduction of the tagged split-intein method for formation of asymmetric nucleosomes.

- 3.Luger K; Mader AW; Richmond RK; Sargent DF; Richmond TJ, Crystal structure of the nucleosome core particle at 2.8 A resolution. Nature 1997, 389, 251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allis CD; Jenuwein T, The molecular hallmarks of epigenetic control. Nature Reviews Genetics 2016, 17, 487–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strahl BD; Allis CD, The language of covalent histone modifications. Nature 2000, 403, 41–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jenuwein T; Allis CD, Translating the Histone Code. Science 2001, 293, 1074–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nacev BA; Feng L; Bagert JD; Lemiesz AE; Gao J; Soshnev AA; Kundra R; Schultz N; Muir TW; Allis CD, The expanding landscape of ‘oncohistone’ mutations in human cancers. Nature 2019, 567, 473–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bernstein BE; Mikkelsen TS; Xie X; Kamal M; Huebert DJ; Cuff J; Fry B; Meissner A; Wernig M; Plath K; Jaenisch R; Wagschal A; Feil R; Schreiber SL; Lander ES, A Bivalent Chromatin Structure Marks Key Developmental Genes in Embryonic Stem Cells. Cell 2006, 125, 315–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mikkelsen TS; Ku M; Jaffe DB; Issac B; Lieberman E; Giannoukos G; Alvarez P; Brockman W; Kim T-K; Koche RP; Lee W; Mendenhall E; O’Donovan A; Presser A; Russ C; Xie X; Meissner A; Wernig M; Jaenisch R; Nusbaum C; Lander ES; Bernstein BE, Genome-wide maps of chromatin state in pluripotent and lineage-committed cells. Nature 2007, 448, 553–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Z; Zang C; Rosenfeld JA; Schones DE; Barski A; Cuddapah S; Cui K; Roh T-Y; Peng W; Zhang MQ; Zhao K, Combinatorial patterns of histone acetylations and methylations in the human genome. Nature Genetics 2008, 40, 897–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schmitges FW; Prusty AB; Faty M; Stützer A; Lingaraju GM; Aiwazian J; Sack R; Hess D; Li L; Zhou S; Bunker RD; Wirth U; Bouwmeester T; Bauer A; Ly-Hartig N; Zhao K; Chan H; Gu J; Gut H; Fischle W; Muller J; Thoma NH, Histone Methylation by PRC2 Is Inhibited by Active Chromatin Marks. Molecular Cell 2011, 42, 330–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Voigt P; LeRoy G; Drury III WJ; Zee BM; Son J; Beck DB; Young NL; Garcia BA; Reinberg D, Asymmetrically Modified Nucleosomes. Cell 2012, 151, 181–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shema E; Jones D; Shoresh N; Donohue L; Ram O; Bernstein BE, Single-molecule decoding of combinatorially modified nucleosomes. Science 2016, 352, 717–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rhee HS; Pugh BF, Comprehensive Genome-wide Protein-DNA Interactions Detected at Single-Nucleotide Resolution. Cell 2011, 147, 1408–1419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rhee HS; Bataille AR; Zhang L; Pugh BF, Subnucleosomal Structures and Nucleosome Asymmetry across a Genome. Cell 2014, 159, 1377–1388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nekrasov M; Amrichova J; Parker BJ; Soboleva TA; Jack C; Williams R; Huttley GA; Tremethick DJ, Histone H2A.Z inheritance during the cell cycle and its impact on promoter organization and dynamics. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 2012, 19, 1076–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu C; Jain SU; Hoelper D; Bechet D; Molden RC; Ran L; Murphy D; Venneti S; Hameed M; Pawel BR; Wunder JS; Dickson BC; Lundgren SM; Jani KS; De Jay N; Papillon-Cavanagh S; Andrulis IL; Sawyer SL; Grynspan D; Turcotte RE; Nadaf J; Fahiminiyah S; Muir TW; Majewski J; Thompson CB; Chi P; Garcia BA; Allis CD; Jabado N; Lewis PW, Histone H3K36 mutations promote sarcomagenesis through altered histone methylation landscape. Science 2016, 352, 844–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Piunti A; Hashizume R; Morgan MA; Bartom ET; Horbinski CM; Marshall SA; Rendleman EJ; Ma Q; Takahashi Y.-h.; Woodfin AR; Misharin AV; Abshiru NA; Lulla RR; Saratsis AM; Kelleher NL; James CD; Shilatifard A, Therapeutic targeting of polycomb and BET bromodomain proteins in diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas. Nature Medicine 2017, 23, 493–500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jain SU; Khazaei S; Marchione DM; Lundgren SM; Wang X; Weinberg DN; Deshmukh S; Juretic N; Lu C; Allis CD; Garcia BA; Jabado N; Lewis PW, Histone H3.3 G34 mutations promote aberrant PRC2 activity and drive tumor progression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2020, 117, 27354–27364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schwartzentruber J; Korshunov A; Liu X-Y; Jones DTW; Pfaff E; Jacob K; Sturm D; Fontebasso AM; Quang D-AK; Tönjes M; Hovestadt V; Albrecht S; Kool M; Nantel A; Konermann C; Lindroth A; Jäger N; Rausch T; Ryzhova M; Korbel JO; Hielscher T; Hauser P; Garami M; Klekner A; Bognar L; Ebinger M; Schuhmann MU; Scheurlen W; Pekrun A; Frühwald MC; Roggendorf W; Kramm C; Dürken M; Atkinson J; Lepage P; Montpetit A; Zakrzewska M; Zakrzewski K; Liberski PP; Dong Z; Siegel P; Kulozik AE; Zapatka M; Guha A; Malkin D; Felsberg J; Reifenberger G; von Deimling A; Ichimura K; Collins VP; Witt H; Milde T; Witt O; Zhang C; Castelo-Branco P; Lichter P; Faury D; Tabori U; Plass C; Majewski J; Pfister SM; Jabado N, Driver mutations in histone H3.3 and chromatin remodelling genes in paediatric glioblastoma. Nature 2012, 482, 226–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu G; Broniscer A; McEachron TA; Lu C; Paugh BS; Becksfort J; Qu C; Ding L; Huether R; Parker M; Zhang J; Gajjar A; Dyer MA; Mullighan CG; Gilbertson RJ; Mardis ER; Wilson RK; Downing JR; Ellison DW; Zhang J; Baker SJ; Project, S. J. C. R. H.-W. U. P. C. G. Somatic histone H3 alterations in pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas and non-brainstem glioblastomas. Nature Genetics 2012, 44, 251–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Behjati S; Tarpey PS; Presneau N; Scheipl S; Pillay N; Van Loo P; Wedge DC; Cooke SL; Gundem G; Davies H; Nik-Zainal S; Martin S; McLaren S; Goody V; Robinson B; Butler A; Teague JW; Halai D; Khatri B; Myklebost O; Baumhoer D; Jundt G; Hamoudi R; Tirabosco R; Amary MF; Futreal PA; Stratton MR; Campbell PJ; Flanagan AM, Distinct H3F3A and H3F3B driver mutations define chondroblastoma and giant cell tumor of bone. Nature Genetics 2013, 45, 1479–1482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis PW; Müller MM; Koletsky MS; Cordero F; Lin S; Banaszynski LA; Garcia BA; Muir TW; Becher OJ; Allis CD, Inhibition of PRC2 Activity by a Gain-of-Function H3 Mutation Found in Pediatric Glioblastoma. Science 2013, 340, 857–861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luger K; Rechsteiner TJ; Richmond TJ Chromatin; Methods in Enzymology; Academic Press, 1999; Vol. 304; pp 3–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li S; Shogren-Knaak MA, Cross-talk between histone H3 tails produces cooperative nucleosome acetylation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2008, 105, 18243–18248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huisinga KL; Pugh BF, A Genome-Wide Housekeeping Role for TFIID and a Highly Regulated Stress-Related Role for SAGA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Molecular Cell 2004, 13, 573–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robert F; Pokholok DK; Hannett NM; Rinaldi NJ; Chandy M; Rolfe A; Workman JL; Gifford DK; Young RA, Global Position and Recruitment of HATs and HDACs in the Yeast Genome. Molecular Cell 2004, 16, 199–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Govind CK; Zhang F; Qiu H; Hofmeyer K; Hinnebusch AG, Gcn5 Promotes Acetylation, Eviction, and Methylation of Nucleosomes in Transcribed Coding Regions. Molecular Cell 2007, 25, 31–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grant PA; Duggan L; Coté J; Roberts SM; Brownell JE; Candau R; Ohba R; Owen-Hughes T; Allis CD; Winston F; Berger SL; Workman JL, Yeast Gcn5 functions in two multisubunit complexes to acetylate nucleosomal histones: characterization of an Ada complex and the SAGA (Spt/Ada) complex. Genes & Development 1997, 11, 1640–1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rojas JR; Trievel RC; Zhou J; Mo Y; Li X; Berger SL; Allis CD; Marmorstein R, Structure of Tetrahymena GCN5 bound to coenzyme A and a histone H3 peptide. Nature 1999, 401, 93–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boyer LA; Langer MR; Crowley KA; Tan S; Denu JM; Peterson CL, Essential Role for the SANT Domain in the Functioning of Multiple Chromatin Remodeling Enzymes. Molecular Cell 2002, 10, 935–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hassan AH; Awad S; Al-Natour Z; Othman S; Mustafa F; Rizvi TA, Selective recognition of acetylated histones by bromodomains in transcriptional co-activators. Biochemical Journal 2007, 402, 125–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Munari F; Soeroes S; Zenn HM; Schomburg A; Kost N; Schroder S; Klingberg R; Rezaei-Ghaleh N; Stützer A; Gelato KA; Walla PJ; Becker S; Schwarzer D; Zimmermann B; Fischle W; Zweckstetter M, Methylation of Lysine 9 in Histone H3 Directs Alternative Modes of Highly Dynamic Interaction of Heterochromatin Protein hHP1β with the Nucleosome. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2012, 287, 33756–33765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Young NL; DiMaggio PA; Plazas-Mayorca MD; Baliban RC; Floudas CA; Garcia BA, High throughput characterization of combinatorial histone codes. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP 2009, 8, 2266–2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yuan W; Xu M; Huang C; Liu N; Chen S; Zhu B, H3K36 Methylation Antagonizes PRC2-mediated H3K27 Methylation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2011, 286, 7983–7989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liokatis S; Klingberg R; Tan S; Schwarzer D, Differentially Isotope-Labeled Nucleosomes To Study Asymmetric Histone Modification Crosstalk by Time-Resolved NMR Spectroscopy. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2016, 55, 8262–8265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horikoshi N; Arimura Y; Taguchi H; Kurumizaka H, Crystal structures of heterotypic nucleosomes containing histones H2A.Z and H2A. Open Biology 2016, 6, 160127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lechner CC; Agashe ND; Fierz B, Traceless Synthesis of Asymmetrically Modified Bivalent Nucleosomes. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2016, 55, 2903–2906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dawson P; Muir T; Clark-Lewis I; Kent S, Synthesis of proteins by native chemical ligation. Science 1994, 266, 776–779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Guidotti N; Lechner CC; Bachmann AL; Fierz B, A Modular Ligation Strategy for Asymmetric Bivalent Nucleosomes Trimethylated at K36 and K27. ChemBioChem 2019, 20, 1124–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guidotti N; Lechner CC; Fierz B, Controlling the supramolecular assembly of nucleosomes asymmetrically modified on H4. Chem. Commun 2017, 53, 10267–10270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ichikawa Y; Connelly CF; Appleboim A; Miller TC; Jacobi H; Abshiru NA; Chou H-J; Chen Y; Sharma U; Zheng Y; Thomas PM; Chen HV; Bajaj V; Müller CW; Kelleher NL; Friedman N; Bolon DN; Rando OJ; Kaufman PD, A synthetic biology approach to probing nucleosome symmetry. eLife 2017, 6, e28836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carrozza MJ; Li B; Florens L; Suganuma T; Swanson SK; Lee KK; Shia W-J; Anderson S; Yates J; Washburn MP; Workman JL, Histone H3 Methylation by Set2 Directs Deacetylation of Coding Regions by Rpd3S to Suppress Spurious Intragenic Transcription. Cell 2005, 123, 581–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huh J-W; Wu J; Lee C-H; Yun M; Gilada D; Brautigam CA; Li B, Multivalent di-nucleosome recognition enables the Rpd3S histone deacetylase complex to tolerate decreased H3K36 methylation levels. The EMBO Journal 2012, 31, 3564–3574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nelson CJ; Santos-Rosa H; Kouzarides T, Proline Isomerization of Histone H3 Regulates Lysine Methylation and Gene Expression. Cell 2006, 126, 905–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Youdell ML; Kizer KO; Kisseleva-Romanova E; Fuchs SM; Duro E; Strahl BD; Mellor J, Roles for Ctk1 and Spt6 in Regulating the Different Methylation States of Histone H3 Lysine 36. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2008, 28, 4915–4926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lo W-S; Trievel RC; Rojas JR; Duggan L; Hsu J-Y; Allis C; Marmorstein R; Berger SL, Phosphorylation of Serine 10 in Histone H3 Is Functionally Linked In Vitro and In Vivo to Gcn5-Mediated Acetylation at Lysine 14. Molecular Cell 2000, 5, 917–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou Z; Liu Y-T; Ma L; Gong T; Hu Y-N; Li H-T; Cai C; Zhang L-L; Wei G; Zhou J-Q, Independent manipulation of histone H3 modifications in individual nucleosomes reveals the contributions of sister histones to transcription. eLife 2017, 6, e30178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gong T; Gu X; Liu Y-T; Zhou Z; Zhang L-L; Wen Y; Zhong W-L; Xu G-L; Zhou J-Q, Both combinatorial K4me0-K36me3 marks on sister histone H3s of a nucleosome are required for Dnmt3a-Dnmt3L mediated de novo DNA methylation. Journal of Genetics and Genomics 2020, 47, 105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ichikawa Y; Saitoh N; Kaufman PD, An asymmetric centromeric nucleosome. eLife 2018, 7, e37911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Levendosky RF; Sabantsev A; Deindl S; Bowman GD, The Chd1 chromatin remodeler shifts hexasomes unidirectionally. eLife 2016, 5, e21356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lowary P; Widom J, New DNA sequence rules for high affinity binding to histone octamer and sequence-directed nucleosome positioning. Journal of Molecular Biology 1998, 276, 19–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chua EYD; Vasudevan D; Davey GE; Wu B; Davey CA, The mechanics behind DNA sequence-dependent properties of the nucleosome. Nucleic Acids Research 2012, 40, 6338–6352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ngo TT; Zhang Q; Zhou R; Yodh JG; Ha T, Asymmetric Unwrapping of Nucleosomes under Tension Directed by DNA Local Flexibility. Cell 2015, 160, 1135–1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kireeva ML; Walter W; Tchernajenko V; Bondarenko V; Kashlev M; Studitsky VM, Nucleosome Remodeling Induced by RNA Polymerase II: Loss of the H2A/H2B Dimer during Transcription. Molecular Cell 2002, 9, 541–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Xiao T; Kao C-F; Krogan NJ; Sun Z-W; Greenblatt JF; Osley MA; Strahl BD, Histone H2B Ubiquitylation Is Associated with Elongating RNA Polymerase II. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2005, 25, 637–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fleming AB; Kao C-F; Hillyer C; Pikaart M; Osley MA, H2B Ubiquitylation Plays a Role in Nucleosome Dynamics during Transcription Elongation. Molecular Cell 2008, 31, 57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee J-S; Garrett AS; Yen K; Takahashi Y-H; Hu D; Jackson J; Seidel C; Pugh BF; Shilatifard A, Codependency of H2B monoubiquitination and nucleosome reassembly on Chd1. Genes & development 2012, 26, 914–919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Levendosky RF; Bowman GD, Asymmetry between the two acidic patches dictates the direction of nucleosome sliding by the ISWI chromatin remodeler. eLife 2019, 8, e45472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kalashnikova AA; Porter-Goff ME; Muthurajan UM; Luger K; Hansen JC, The role of the nucleosome acidic patch in modulating higher order chromatin structure. Journal of The Royal Society Interface 2013, 10, 20121022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McGinty RK; Tan S, Nucleosome Structure and Function. Chemical Reviews 2015, 115, 2255–2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dann GP; Liszczak GP; Bagert JD; Müller MM; Nguyen UTT; Wojcik F; Brown ZZ; Bos J; Panchenko T; Pihl R; Pollock SB; Diehl KL; Allis CD; Muir TW, ISWI chromatin remodellers sense nucleosome modifications to determine substrate preference. Nature 2017, 548, 607–611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stevens AJ; Brown ZZ; Shah NH; Sekar G; Cowburn D; Muir TW, Design of a Split Intein with Exceptional Protein Splicing Activity. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2016, 138, 2162–2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vila-Perello M; Liu Z; Shah NH; Willis JA; Idoyaga J; Muir TW, Streamlined Expressed Protein Ligation Using Split Inteins. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2013, 135, 286–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Su Z; Boersma MD; Lee J-H; Oliver SS; Liu S; Garcia BA; Denu JM, ChIP-less analysis of chromatin states. Epigenetics & Chromatin 2014, 7, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kuznetsov VI; Haws SA; Fox CA; Denu JM, General method for rapid purification of native chromatin fragments. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2018, 293, 12271–12282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schachner LF; Jooß K; Morgan MA; Piunti A; Meiners MJ; Kafader JO; Lee AS; Iwanaszko M; Cheek MA; Burg JM; Howard SA; Keogh M-C; Shilatifard A; Kelleher NL, Decoding the protein composition of whole nucleosomes with Nuc-MS. Nature Methods 2021, 18, 303–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Poepsel S; Kasinath V; Nogales E, Cryo-EM structures of PRC2 simultaneously engaged with two functionally distinct nucleosomes. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 2018, 25, 154–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Finogenova K; Bonnet J; Poepsel S; Schäfer IB; Finkl K; Schmid K; Litz C; Strauss M; Benda C; Müller J, Structural basis for PRC2 decoding of active histone methylation marks H3K36me2/3. eLife 2020, 9, e61964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]