Abstract

While feeding challenges in autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are prevalent, they continue to pose a significant diagnostic challenge, leading to misdiagnosis and under diagnosis of factors, both contextual and inherent, that may lead to negative health outcomes. Early identification of feeding difficulties in ASD is necessary to minimize negative health outcomes and strained parent–child relationships. Family physicians and paediatricians are positioned to reduce the impact of such disordered feeding behaviours on the child, family, and health care system. Providing clinicians with a conceptual framework to systematically identify factors contributing to the ‘feeding challenge’ construct will ensure the appropriate intervention is provided. We present the MOBSE conceptual framework, a multidisciplinary lens for assessing feeding challenges in ASD. This will aid in the proper diagnosis of feeding challenges seen in ASD.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder, ARFID, Feeding challenges

THE IMPORTANCE OF ADDRESSING FEEDING CHALLENGES IN AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDER

There continues to be a lack of awareness and consensus in the medical community for how to properly identify and assess children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) who present with feeding challenges. Early identification and appropriate management are central to converting a problematic feeding challenge with potential negative health outcomes to an enjoyable feeding experience with positive health outcomes and parent–child relationships.

Feeding challenges occur five times more often in children diagnosed with ASD as compared to typically functioning peers (1). Food selectivity is the most commonly reported disordered feeding behaviours in ASD and is noted across the lifespan (2). It presents with preference of carbohydrates and an aversion to fruits, whole grains, and vegetables. Acceptance and refusal of food can be based on its colour, presentation, smell, temperature, and texture (3,4). Contributing factors are diverse, ranging from negative feeding experiences, constipation, gastroesophageal reflux disease, oral-motor challenges, and sensory differences. Although population-based information around the burden of diet-related illness in children with ASD is not fully developed, it is clear that dietary deficiencies have a significant impact on health and wellness. Significant food selectivity (elimination of one or more food groups) is associated with iron deficiency anemia, low protein and calcium levels, difficult mealtime behaviours, and parental stress (1).

Recent research identifies the economic burden of unhealthy eating habits among Canadians as CAD$13.8 billion/year (5). Improvement of one’s diet can potentially prevent one in every five deaths globally; nonoptimal intake of whole grain, fruits, and sodium accounted for more than 50% of death and 66% of disability-adjusted life-years attributable to diet (6). Initiatives geared at addressing dietary habits from the population level starting from early childhood have a direct positive impact on lowering the economic burden resulting from unhealthy dietary habits (5).

In 2018, the Canada Food Guide introduced new guidelines to promote healthy eating and overall nutritional wellbeing for Canadians. Guideline 1 recommends that vegetables, fruit, whole grains, and protein foods for, e.g., plant-based proteins should be consumed more regularly (7). One population that might find it challenging to adopt these new guidelines are children, youth, and adults diagnosed with ASD. Behavioural feeding advice as to ‘HOW’ to get the child or youth to eat these foods is needed. A systematic review identified that provision of nutritional information is inadequate in changing dietary behaviours (8). The potential compounding effect of dietary inequities amongst lower income Canadians adds a layer of urgency in addressing this issue (9,10). Physicians require a systematic approach to assess possible factors that contribute to feeding challenges, and in doing so identify key clinicians to address these factors as they emerge.

Recently, the DSM 5 introduced the term ARFID, which is typified by an eating or feeding disturbance as manifested by persistent failure to meet appropriate nutritional and/or energy needs associated with one of the following: (1) Significant weight loss; (2) Significant nutritional deficiency; (3) Dependence on enteral feeding or nutritional supplements and; (4) Marked interference with psychosocial functioning. This occurs in the absence of lack of availability of food or associated culturally sanctioned practices. This eating disturbance occurs outside of a course of anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa and is not better explained by a concurrent medical or mental disorder (11,12). Our understanding of ARFID is evolving but still limited. Its prevalence ranges from 5 to 23% in the tertiary feeding clinic population (13). The peak age of onset is between 4 and 13 years, and is associated with food selectivity with limited amount and range based on appearance, texture, and taste. There is no associated fear of gaining weight and there is an increase incidence of anxiety. ARFID has the potential to lead to invasive medical procedures (e.g., placement of a NGT or GT) and psychosocial challenges.

ARFID and ASD paths can intersect; in one study, 13% of children diagnosed with ARFID had ASD (14). Lack of awareness makes the diagnosis and initiation of appropriate management difficult. There are no empirically validated treatments, guidelines, or care pathways for ARFID and/or feeding challenges in ASD. This is challenging as persons with ASD and feeding challenges may go unrecognized for long periods of time which may result in treatment resistance and negative health outcomes. From our collective experience, invasive medical procedures are controversial but a concern for children diagnosed with ASD and ARFID who have failed conventional medical and behavioural management. While working on policies to address social and nutritional determinants of health, front-line clinicians also need to take a leadership role in the early identification of feeding challenges with a goal to change feeding trajectories over time.

ADDRESSING DIFFICULTIES IN THE ASSESSMENT AND MANAGEMENT OF FEEDING CHALLENGES IN ASD

A multidisciplinary approach is recommended for the management of significant feeding challenges in children (15). In Canada, there are very few multidisciplinary feeding teams available and even fewer for children with ASD. Geographic and limited clinical expertise are barriers to supporting persons with ASD with the appropriate feeding assessment and intervention plan. We propose that family physicians and paediatricians play an important role in the early conversation(s) of healthy nutrition and assessment of feeding challenges in ASD with an aim to change the child’s feeding trajectory.

Given the paucity of evidenced based feeding intervention programs specifically for ASD, it is important that physicians are able to assess all possible contributing factors (contextual or inherent) to the construct of a ‘feeding challenge’ in a person with ASD and in so doing, be able to indicate which intervention(s) is best suited for the child and family. However, despite the evidence supporting the heterogeneous aetiology and presentation of feeding challenges in children with ASD, there continues to be no specific framework to provide a comprehensive, multidisciplinary feeding assessment for this population. In clinical practice children who present with feeding challenges and ASD are often prescribed sensory-based strategies to address these difficulties. Although sensory factors may be a contributing factor, clinicians may overlook other aetiologies such as oral-motor or parent–child relationship factors, leading to inappropriate and thus ineffective interventions. Completing a proper assessment will help lead the clinician to recommend the most appropriate treatment(s) for the child. Treatments targeting the most responsible factors are more likely to be effective.

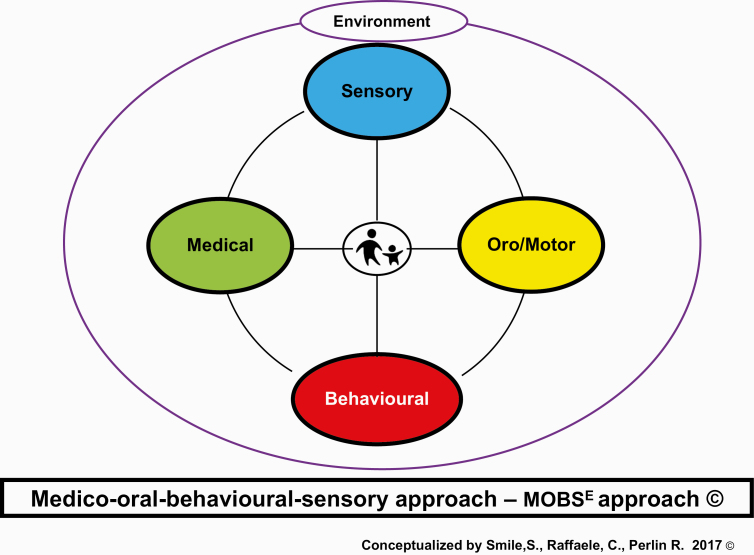

Our solution to this dilemma is to offer a framework in which clinicians can systematically review and consider all possible aetiologies to the ‘feeding challenge’ construct with an aim to examine which factors may be contributing to an individual child’s feeding challenge. This framework is the MOBSE approach and is designed to guide clinicians through each factor: Medical/Nutrition, Oral-Motor, Behaviour, Sensory and Environmental to help properly identify the aetiology(ies) of a child’s feeding challenge (Figure 1). The MOBSE conceptual framework is grounded in the premise that the parent–child relationship and parental anxiety around feeding impacts all aspects of feeding and requires consideration as clinicians move through each element of the framework. The tenets of the MOBSE approach include five key pillars (Table 1). This framework is intended to be used to identify which factor(s) is contributing to the child’s feeding challenge and will guide the clinician to identify which allied health professional (e.g., Occupational Therapist, Behaviour Analyst, Speech and Language Pathologist, Dietitian, Psychiatrist, Gastroenterologist, Paediatrician) should be involved in the child’s assessment and management plan.

Figure 1.

The Medico-oral-behavioural-sensory approach - MOBSE approach.

Table 1.

The tenets of the MOBSE approach©

| Factor | Description | Red flags | Resources/team members |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical/ Nutrition | ◦ Identify common medical factors that may alter feeding behaviours such as: constipation, GERD, food allergies, gastritis, dysphagia (coughing, choking or drooling with meals) and medication such as stimulants or antipsychotic agents. ◦ Identify the child’s developmental age and acquisition of appropriate feeding skills. ◦ Determine if the child is nutritionally stable as indicated by: weight, height, BMI, growth curve, hydration status, micro/macronutrient intake, HR, BP ◦ Document pubertal phase, peripheral stigmata of malnutrition or nutritional deficiencies | ◦ Pain with feeding ◦ Recurrent vomiting and/or diarrhea ◦ Growth failure ◦ Pallor, lethargy ◦ Abdominal pain ◦ Hitting of abdomen (nonverbal child) ◦ H/O Aspiration ◦ Meets criteria for ARFID | Feeding Handbook: See Buie et al. (2010) (16) and Smile (2019) (12) Consult a Dietitian and/or Gastroenterologist and/or Feeding specialist team as indicated |

| ◦ Identify any oral-motor challenges that may impact a child’s feeding performance such as: anatomical differences (cleft, tongue tie, structure of mouth/teeth), delayed oral-motor skills (poor tongue lateralization, poor lip closure) leading to a mismatch of food offered not aligning with child’s current oral-motor skill level. | ◦ Drooling ◦ H/O gagging or choking ◦ Difficulty advancing textures | Feeding Handbook: See Barton et al. (2018) (17) Consult a Speech and Language Pathologist as indicated | |

| ◦ Identify mealtime behaviours that may be contributing to a child’s feeding performance such as: avoidance, refusal, tantrums, self-injurious behaviours ◦ Complete a functional behavioural assessment to determine the function of the disruptive mealtime behaviours | ◦ Self-injurious behaviours at mealtimes ◦ Self-Induced Vomiting ◦ Inability to eat in different environments | Consult a Behaviour Analyst as indicated | |

| ◦ Determine whether the child is experiencing sensory processing differences that may be impacting on their feeding performance such as: sensitivity to taste, texture, smell, appearance, sound of foods, challenges sitting, challenges sensing hunger cues | ◦ Anticipatory Gagging or Vomiting to certain scent or on seeing specific foods | Feeding Handbook Consult an Occupational Therapist as indicated | |

| ◦ Assess environmental factors that may be contributing to a child’s feeding performance such as: mealtime schedule, distractions, positioning, different feeders, seating | ◦ Use of electronics to facilitate meal times ◦ Grazing | Consult a Behaviour Analyst as indicated | |

| ◦ Evaluate for parental anxiety around feeding ◦ Identify parent feeding style | ◦ Force feeding ◦ H/O Depression or Anxiety (parent or child) | See Hughes et al. (2005) (18) | |

| Severe food selectivity: Consider if there is elimination of one or more food groups, consumes five or fewer foods. ARFID: If child meets criteria for ARFID referral to a multidisciplinary feeding team is recommended. |

Feeding Handbook link: Evidence to Care, Feeding and Swallowing Team. Optimizing feeding and swallowing in children with physical and developmental disabilities: a practical guide for clinicians [PDF]. Toronto, ON: Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital; 2017. Available from: https://hollandbloorview.ca/teachinglearning/evidencetocare/knowledgeproducts/feedingandswallowinghandbook

ARFID Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder; BP Blood Pressure; GERD Gastroesophageal reflux disease; HR Heart Rate; H /O History of.

In a child presenting with ‘feeding challenges’, it is imperative that we first ensure that the child is nutritionally adequate with absence of decompensation or malnutrition. Identifying the severity of the feeding challenges is next: does this child meet criteria for ARFID? (Table 2). The MOBSE conceptual framework is then implemented to facilitate a systematic evaluation of all possible factors that may be contributing to the feeding challenge. After ruling out factors that are not implicated in the feeding challenge, the contributing factors should then be prioritized as areas to treat.

Table 2.

Diagnostic checklist for avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder

| Diagnostic Criteria –Inclusionary criteria (meet one of four criteria) | Examples | History | Additional evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| A: Eating and Feeding Disturbance: Manifested as failure to meet appropriate nutritional/energy needs | □ Lack of interest in food □ Avoidance based on sensory characteristics- smell, color, temp, texture, appearance, taste □ Aversive consequence of eating | □ | □ Skipping meals □ H/O choking □ Avoids fruits/veg |

| 1. Significant weight loss – clinical judgment | □ Not maintaining weight or height trajectory | □ | □ Growth charts |

| 2. Significant nutritional deficiency – clinical assessment | □ Dietary intake □ Evidence on physical examination □ Iron deficiency anemia □ Bradycardia, dizziness, hypothermia | □ | □ Laboratory Testing |

| 3. Dependence on enteral feeding or oral nutritional supplements | □ Nutritionally complete supplements □ Nasogastric tube feeding □ Gastrostomy tube feeding | □ | |

| 4. Interfere with psychosocial functioning | □ Difficulty eating with others □ Difficulty to sustain relationships as a result of the disturbance | □ | |

| Diagnostic Criteria – Exclusionary criteria | |||

| B: Not explained by lack of available food or culturally sanctioned practice | □ Religious fasting □ Normal dieting □ Picky eater in toddlers | □ | |

| C: Absence of Anorexia Nervosa or Bulimia Nervosa: No evidence of a disturbance in the way one’s body weight or shape is experienced | □ | ||

| D: Not explained by concurrent medical or mental disorder (eating disturbance exceeds that routinely associated with the disorder and warrants additional clinical attention) | □ | ||

| Specify: In Remission □ |

Checklist created by Dr. Sharon Smile (19).

The MOBSE conceptual framework allows the clinician and families the ability to continue to assess the patient’s feeding challenges throughout the lifespan. In the spirit of co-creation, the family and child become part of the intervention plan along with the feeding team.

Families that have children with ASD who present with significant feeding challenges should not simply be told to ‘follow the food guide’, but instead be provided with access to a multidisciplinary team that is equipped to systematically identify areas of challenges in order to inform appropriate treatment goals and interventions. By using the MOBSE framework, clinicians can address feeding challenges at their initial presentation with the intent to change the child’s feeding trajectory for the better. Building awareness and capacity amongst clinicians and families is the first step in understanding and identifying appropriate interventions to match the broad spectrum of feeding challenges seen in ASD. This new knowledge will then help to inform social and nutritional policies geared at impacting social determinants of health in ASD over the lifespan with an aim to ensure cultural preferences are considered and if possible preserved.

Funding: There are no funders to report for this submission.

Potential Conflicts of Interest: All authors: No reported conflicts of interest. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Sharp WG, Berry RC, McCracken Cet al. Feeding problems and nutrient intake in children with autism spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis and comprehensive review of the literature. J Autism Dev Disord 2013;43(9):2159–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bandini LG, Curtin C, Phillips S, Anderson SE, Maslin M, Must A. Changes in food selectivity in children with autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;47(2):439–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahearn WH, Castine T, Nault K, Green G. An assessment of food acceptance in children with autism or pervasive developmental disorder-not otherwise specified. J Autism Dev Disord 2001;31(5):505–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams PG, Dalrymple N, Neal J. Eating habits of children with autism. Pediatr Nurs 2000;26(3):259–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lieffers JRL, Ekwaru JP, Ohinmaa A, Veugelers PJ. The economic burden of not meeting food recommendations in Canada: The cost of doing nothing. PLoS One 2018;13(4):e0196333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Afshin A, Sur PJ, Fay KA, et al. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet. 2019;393(10184):1958–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Minister of Health. Canada’s Food Guide 2019. <https://food-guide.canada.ca/en/> (Accessed November 12, 2019).

- 8.McGill R, Anwar E, Orton L, et al. Are interventions to promote healthy eating equally effective for all? Systematic review of socioeconomic inequalities in impact. BMC Public Health 2015;15:457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colapinto CK, Graham J, St-Pierre S. Trends and correlates of frequency of fruit and vegetable consumption, 2007 to 2014. Health Rep 2018;29(1):9–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garriguet D. Diet quality in Canada. Health Rep 2009;20(3):41–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Psychiatric Association., American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 Task Force. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders DSM-5. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. <http://myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/login?url=https://dsm.psychiatryonline.org/doi/book/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596> (Accessed November 12, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smile S. A 4-year-old boy with food selectivity and autism-spectrum disorder. CMAJ 2019;191(23):E636–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norris ML, Spettigue WJ, Katzman DK. Update on eating disorders: Current perspectives on avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in children and youth. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2016;12:213–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicely TA, Lane-Loney S, Masciulli E, Hollenbeak CS, Ornstein RM. Prevalence and characteristics of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder in a cohort of young patients in day treatment for eating disorders. J Eat Disord 2014;2(1):21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharp WG, Volkert VM, Scahill L, McCracken CE, McElhanon B. A systematic review and meta-analysis of intensive multidisciplinary intervention for pediatric feeding disorders: How standard is the standard of care? J Pediatr 2017;181:116–124.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buie T, FuchsGJ, 3rd, Furuta GT, et al. Recommendations for evaluation and treatment of common gastrointestinal problems in children with ASDs. Pediatrics. 2010;125(Suppl 1):S19–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barton C, Bickell M, Fucile S. Pediatric oral motor feeding assessments: Systematic review. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2018;38(2):190–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hughes SO, Power TG, Orlet Fisher J, Mueller S, Nicklas TA. Revisiting a neglected construct: Parenting styles in a child-feeding context. Appetite. 2005;44(1):83–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 task force. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]